Résumés

Abstract

Drawing on an interdisciplinary approach combining linguistics and International Business, we suggest that global and local dynamics interact to co-construct specific language practices in an MNC subsidiary situated in a cross-border territory. We show how introducing a foreign language can modify the benefits that these local multilingual practices generate.

Employees revert to translanguaging: They combine all their language knowledge, French, German and local vernacular, to make themselves understood. These specific local language practices have an inclusive role that enables low-level employees in the hierarchy to play a linking role between the multinational company subsidiary and its headquarters in Germany.

Keywords:

- Multilingualism,

- cross-border work,

- boundary spanners,

- translanguaging,

- ecolinguistics,

- multinational companies

Résumé

Grace à une approche interdisciplinaire combinant linguistique et management international, nous suggérons qu’au sein de la filiale d’une multinationale située dans un territoire frontalier, les dynamiques globales et locales co-construisent des pratiques linguistiques spécifiques. Nous montrons comment l’introduction de l’anglais modifie les bénéfices générés par ces pratiques multilingues locales.

Les employés ont recours au translanguaging : ils combinent toutes leurs connaissances linguistiques, français, allemand et langue vernaculaire pour se faire comprendre. Ces pratiques linguistiques locales ont un rôle inclusif permettant aux employés moins élevés dans la hiérarchie de faire le lien entre la filiale et le siège social en Allemagne.

Mots-clés :

- Multilinguisme,

- travail frontalier,

- boundary spanner,

- translanguaging,

- écolinguistique,

- entreprises multinationales

Resumen

Gracias a un enfoque interdisciplinario combinando la lingüística y la gestión internacional, sometemos a discusión el hecho de que en una filial de una empresa multinacional situada en una zona fronteriza, las dinámicas globales y locales construyan conjuntamente unas prácticas lingüísticas específicas. Demostramos cómo la introducción del inglés modifica los beneficios generados por estas prácticas plurilingües.

Los empleados utilizan el translanguaging: combinan sus conocimientos lingüísticos, principalmente en francés, en alemán y en el idioma regional para comunicarse. Estas prácticas lingüísticas locales desempeñan una función inclusiva, permiten a los empleados situados en niveles bajos de la jerarquía vincular la filial francesa con la sede social en Alemania.

Palabras clave:

- Plurilingüismo,

- trabajo fronterizo,

- boundary spanner,

- translanguaging,

- ecolingüística,

- empresas multinacionales

Corps de l’article

The diversification of direct investment flows and its rebalance in favor of emerging markets increase the heterogeneity of local environments for multinationals (Jaussaud and Mayrhofer, 2014). This situation raises the question of global players accounting for local specificities and calls for a new understanding of the relationships between global and local dynamics (Mayrhofer and Very, 2013). With this perspective, one should view multinational companies (MNCs) as sites where global and local dynamics co-construct reality instead of approaching globalization and localization forces as separate entities.

Languages practices lie at the heart of these “glocalization” dynamics. We know that although the MNC globalization process often entails introducing English as a common corporate language (Luo and Shenkar, 2006; Harzing, Köster and Magner, 2011), MNCs remain multilingual establishments by nature and employees widely speak local languages in several subsidiaries (Fredriksson, Barner-Rasmussen and Piekkari, 2006). The literature describes different multilingual practices in organizations (Steyaert, Ostendorp and Gaibrois, 2011; Gaibrois, 2018) that enact global local dynamics. The concept of multilingual franca (Janssens and Steyaert, 2014) explains the combined usage of different languages in MNCs. With multilingual franca, the focus is on “language in use”. Researchers no longer approach language as a given variable influencing other phenomena. Rather, they highlight a negotiated, situated approach to language where speakers use multiple linguistic resources to make themselves understood. Multilingual franca contrasts with the notion of lingua franca as a common language between speakers whose native languages are different. Janssens and Steyaert (2014) draw on sociolinguistics to explain this conceptual shift. Sociolinguistics is “the branch of linguistics which studies all aspects of language and society” (Biber and Finegan, 1994, p. 3). Bringing these concepts into the field of International Business (IB) offers the opportunity for researchers to analyze language as it functions in the everyday social and vocational lives of MNC employees. The specific concept of translanguaging (Garcίa, 2009) is particularly useful to account for the intertwining of global and local influences on language practices in MNC subsidiaries. With translanguaging practices, interlocutors draw on their entire language repertories to make themselves understood, combining different national languages and vernaculars and even inventing new words (Garcίa, 2009). We know that local context influences language repertories in MNC subsidiaries (Lejot, 2015). Linguists use the concept of language ecology to identify all the languages that individuals use in a specific context (Fill and Mühlhäusler, 2006) and their link to geographical space and history (Kramsch and Whiteside, 2008). We propose applying this concept to MNCs and assume that the specific language practices that an MNC’s subsidiary uses, namely mixing different languages, vernaculars and corporate jargon, constitute a language ecology. It is important to understand why language can become a barrier or a facilitator in a specific organizational context because we know that MNCs face many linguistic challenges primarily in the subsidiary context (Bordia and Bordia, 2015). However little is known in international business literature to date on the consequences of introducing a new foreign language on language uses and their modifications in subsidiaries.

This paper seeks to investigate how introducing a foreign language affects the balance of the language ecology, particularly translanguaging practices and their consequences in a given subsidiary in view of its local context, and the tensions these changes may entail. Resorting to language ecology gives us the opportunity to understand how a subsidiary’s location intertwines with the MNC’s global approach to influence actual language practices.

To do so, we analyze language practices in the specific environment of smartFrance at a time when corporate management introduces English in the group following internationalization. Smart is a subsidiary of the German firm Daimler AG. We analyze introducing English as a foreign language and not as a common corporate language, because management has not enforced English as a common corporate language at smart and does not concern everybody in the firm. The Daimler AG branch that we are studying is in France at the French-German border, where it is local practice to combine German and French.

The originality of our approach consists of implementing sociolinguistics and ecolinguistics, thus combining the notion of translanguaging with the concept of language ecology (Fill and Mühlhäusler, 2006). This makes it possible to understand the disruptive effect of introducing a foreign language on multilingual language practices linked to the location of a given MNC unit.

From this perspective, our study contributes to language sensitive international business research in two ways:

First, focusing on the pragmatic use of all languages present in the subsidiary, we show how translanguaging practices are embedded in the region and incorporated in people’s everyday use.

Second, we suggest that translanguaging practices may promote including individuals at low levels in the hierarchy, enabling them to participate in boundary spanning activities that are usually reserved for managers in the MNC.

We continue with a review of IB literature on multilingual practices in MNCs before clarifying the concepts of translanguaging and language ecology. We then describe our methodology and choices for data collection and analysis and present and discuss our results, applying a language ecology perspective to translanguaging practices.

Literature Review: Going Beyond the Analysis of Language as a National Proficiency to Understand Multilingual Practices Within MNCs

Some scholars support introducing a lingua franca that crosses the linguistic boundaries of MNCs, thereby favoring a dynamic of globalization. (Luo and Shenkar, 2006), while proponents of local languages denounce the imperialistic and hegemonic impacts of a lingua franca (often English) on the actors of local subsidiaries (Piekkari et al., 2005; Tietze, 2008). Some recent publications attempted to go beyond this dichotomy and researched issues such as the parallel use of multiple languages (Steyaert, Ostendorp and Gaibrois, 2011), code-switching (e.g., Harzing, Köster and Magner, 2011) or interplay between national languages and company jargon (Marschan-Piekkari, Welch and Welch, 1999; Lauring, 2011; Logemann and Piekkari, 2015). To explain the combined use of different national languages, Janssens and Steyaert (2014) developed the notion of multilingual franca based on the sociolinguistic concept of translanguaging practices (Garcίa, 2009), which combine different national languages and/ or vernaculars, thus leading to inventing new words.

It is important to understand the inner dynamic of these language combinations within MNCs because subsidiary employees recontextualize the language policies that the company headquarters mandate in different ways (Fredriksson et al. 2006; Peltorkorpi and Vaara, 2014; Brannen and Mughan, 2016). For instance, management has imposed strictly English on employees at Rakuten, a Japanese MNC, and within two years employees in every MNC unit complied (Neeley, 2017), while employees in the Finnish subsidiary of MeritaNordbanken (Vaara et al., 2005) rejected using Swedish. Lüdi, Höchle and Yanaprasart (2013) point out that the practices in use differ significantly from the recommendations of existing language policies. Through this language policy mandate recontextualization, employees adapt corporate language to local needs by drawing on their local language repertories (Lejot, 2015). The MNC internationalization strategy also influences these local needs. Steyaert, Ostendorp and Gaibrois (2011) analyze the language practices of two MNCs located in the French part of Switzerland and show that they have very different approaches to language use in the quadrilingual environment in which their operations are located. The country of the MNC headquarters is also an important factor. Harzing and Pudelko (2013) have shown that language practices differ according to the MNC’s home country. Similarly, Bordia and Bordia (2015) show that host country employees’ willingness to adopt a foreign language depends among others on the strength of their linguistic identity. Therefore, employees observe attitudes to languages according to MNCs’ subsidiary location. Although researchers have observed different kinds of multilingual practices in MNCs, it is still not clear how introducing a foreign language affects these practices.

As for the consequences of introducing new languages within organizations, we know that employees with multiple proficiencies in different national languages have better career prospects (Itani, Järlstrom and Piekkari, 2015) and accomplishing boundary-spanning tasks can empower them (Barner-Ramussen et al., 2014). Native English employees even benefitted from an unearned status gain when management introduced English at Rakuten (Neeley and Dumas, 2016). A language proficiency fault line between different hierarchical levels indicates that white-collar workers are far more proficient in national language skills than blue-collar workers (Barner-Rasmussen and Aarnio, 2011). Therefore, traditional language skills in different national languages, and especially the language that employees commonly use at work, appear as an empowering resource for MNC employees. However, companies to date do not view combining different languages and the disregard for the grammar and codes of national languages that occur in translanguaging as a practice worth cultivating in the organization. Welch and Welch (2018, p. 854) deplore this tendency and show that MNCs and individuals co-construct a specific language capital that requires preservation through developing a “language operative capacity” i.e., “language resources that have been assembled and deployed in a context-relevant and timely manner”. These authors insist on the need to deepen our understanding of the intricacies of multilingual capacity and the benefit it could bring to the organization (Welch and Welch, 2018).

We now move on to suggest that renewing language conceptualization can lead to a better understanding of the consequences of adding a new language to existing multilingual practices in a given MNC unit. This is important to help MNCs identify what they can do to preserve resorting to translanguaging practices as positive resources for themselves and for individuals as well and manage the fear and tensions among employees induced by introducing a new language.

Reconceptualizing Multilingual Practices In MNC Through Translanguaging And Language Ecology

Some language-sensitive scholars of international business have denounced the tendency to study language in management purely in terms of national languages (Tietze, Holden and Barner-Rasmussen, 2016). To move away from this simplified approach to language, recent interdisciplinary endeavors between international business and sociolinguistics encourage academics to investigate fluid and hybrid language practices (Angouri and Piekkari, 2018). Similarly, modern linguists acknowledge the limitations of approaching languages as timeless and decontextualized objects and offer new conceptualizations of languages such as the concept of translanguaging at the center of our analysis (Garcίa, 2009; Wei, 2011; Garcίa, Flores and Woodley Homonoff, 2012), or translingual practice (Canagarajah, 2012). These language reconceptualizations focus on practices and conceive language as jointly mobilizing linguistic resources to find pragmatic solutions to create meaning in specific situations. In this view, language use is a bricolage where users “disinvent and reconstitute languages” (Makoni and Pennicook, 2006). The interlocutors’ co-construction experience through language use precedes languages and leads to the the weakening or even disappearance of boundaries between languages. For Garcίa (2009, p. 40), the concept of translanguaging is “the act performed by bilinguals of accessing different linguistic features or various modes of what are described as autonomous languages, in order to maximize communicative potential. It is an approach to bilingualism that is centred (…), on the practices of bilinguals that are readily observable to make sense of their multilingual worlds.” In this sense, interlocutors use different languages simultaneously (e.g., French, German and English and the variations or dialects associated with them). This can sometimes even occur in the same sentence. Speakers can also create new words to improve mutual comprehension.

Although the concept of translanguaging enables us to accept the idea of combining sets of linguistic resources that may or may not reflect canonically recognized language codes, it fails at explaining why these specific language practices are accepted and engrained in the given MNC subsidiary space. Clarifying this relation has the potential to highlight in which ways introducing a new language disconnected from the area in question would potentially have disrupting effects in terms of communication for employees.

To do so, we propose to complement this translanguaging approach with the concept of language ecology (Fill and Mühlhäusler, 2006) to understand how the subsidiary’s location that we analyzed and the global MNC approach intertwine to influence actual language practices in this specific context. Language ecology analyzes the relation between languages and their environment in specific areas with a focus on interpersonal co-creation of meaning (Van Lier, 2006). Language ecology suggests accounting for hybrid language use in multilingual settings by referring to the dimensions of history and space (Kramsch and Whiteside, 2008). We can explain translanguaging practices through the enactment or re-enactment of past language practices, or by rehearsing cultural memories inherited from history. They can allude to rehearsing potential identities in relation to space. This ecological perspective provides a means to identify how introducing a new foreign language modifies multilingual practices based on the embeddedness of local language use and the MNCs’ global organizational context.

Viewing language as a practice through using translanguaging offers us the opportunity to investigate multilingual practices from a new angle. Breaking free from canonical language codes, we can elucidate language practices by combining different languages in creative ways. Including the concept of language ecology in our analysis makes it possible to highlight how introducing a new language may disturb the complex balance of these language practices in a specific local and global organisational context. Understanding these global-local dynamics enacted in language practices has the potential of explaining fears and tensions among employees within the subsidiary. It is a first step towards designing more adapted language training solutions to improve communication between MNCs entities.

Methodology

This study aims to understand how introducing a foreign language modifies a specific MNC unit’s language ecology and to identify the tensions this change may entail. To understand the interplay between global and local dynamics at play within the smart subsidiary when it comes to language, we chose to use a situated approach to grounded theory (Clarke, 2003). Traditional grounded theory technique builds theory through abstracting concepts from raw data (Glaser and Strauss, 1967). It is based on constantly comparing data and theory and permits accumulating evidence from diverse sources. This methodology is well suited to new research areas and our study is exploratory. We approach a business field with a new perspective through linguistic concepts, and context is central to our reflection. Clarke (2003) introduces a constructivist grounded theory (Glaser and Strauss, 1967) and draws upon the postmodern approach to situate fields through “situational maps and analysis”. The author completes the traditional grounded theory by combining its inductive perspective with specifying an initial orienting framework to focus on raw data observation. “Situational maps” comprise this initial framework that is based on “all the situations of concern in the project”. Drawing on post-modern scholarship committed to situated interpretation, the situated approach to grounded theory offers the opportunity to deeply situate the research, socially, organizationally, temporally and geographically. It answers well to our concern of incorporating translanguaging practices (Garcίa, 2009) and language ecology (Fill and Mühlhäusler, 2006) as initial orienting concepts to analyze our data by drawing special attention to linking language practices with history and space. Moreover, this postmodern approach to grounded theory gives us the opportunity to integrate concepts and data collection methods from different disciplinary fields. This was important for the authors of the present study, who represent different fields, namely international business and linguistics. Our discussions about integrating interdisciplinary concepts were enlightening, given the interest of using linguistics to understand a managerial phenomenon. The concept of language ecology and of translanguaging led us to consider the destabilization of the language combination balance in the smart car manufacturing plant. Thus, Clarke’s (2003) situated approach to grounded theory answers well our aim to draw on the context of a single case to form an in-depth understanding of the tensions that language ecology modification causes in an MNC unit after introducing a new language.

We chose the smart car manufacturing plant mainly because the linguistic boundaries in the organization were a matter of concern for the company leadership, and because this subsidiary is located in a cross-border area of France, near the German border. In this context, it was easy to observe how introducing English in the workplace endangered multilingual practices. The firm has 800 employees, of which twenty percent are women. The average employee age is 38, and employees live an average of 30 km from the smart site (data taken from an accommodation list provided by the human resources department), with most of them living in France. The employees are of different nationalities, including French, and the majority are French-speaking. Only five percent are German, and these employees mainly work in administrative support functions and use German as their first language. A German CEO manages Smart France. While management does not apply any formal and explicit linguistic policy at smart, French and German linguistic skills are required recruitment criteria for support and management functions, while English is crucial for specific international projects. Most of the visual communication structures such as signboards, are in French and German, occasionally in English, or in a specific company jargon with specific terms that smart elaborated upon and used.

Data Collection

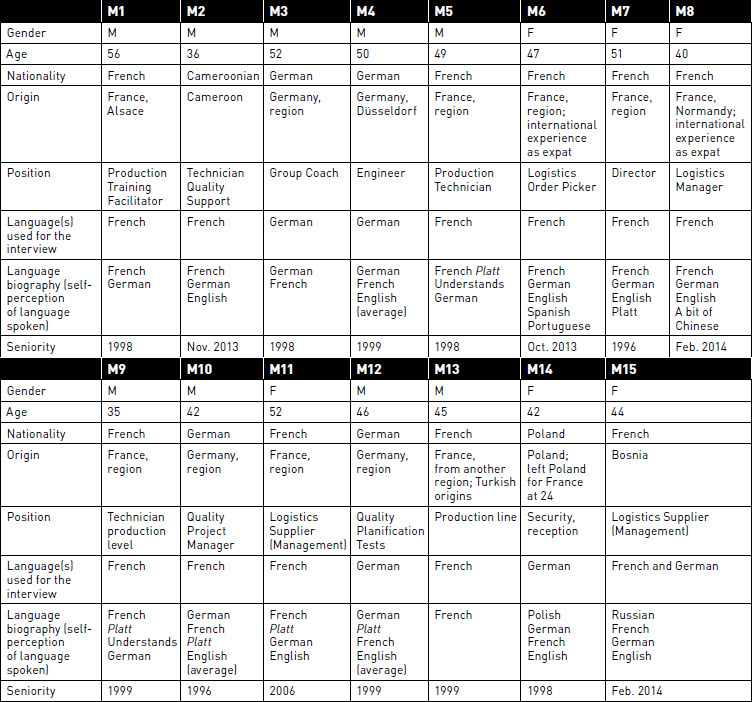

We began with guided interviews to investigate language practices and communication in the organization, employees’ links with the region and with the border, their career development opportunities and individual language biographies. To ensure data triangulation, we primarily approached language practices through interview data supplemented by on-site observation as well as internal and external secondary data (Lincoln and Guba, 1985). We conducted seven interviews with management team members who were involved in investigating language learning in the organization (see Table 1). Data were classified according to the employee’s position and the interview order. We started our data collection process by interviewing the director of human resources (D1-1) and met him for a second interview after interviewing the employees (D1-2). After his departure from the site we interviewed his successor twice (D2-1, D2-2). This provided us with two different perspectives. We interviewed the CEO twice (D3-1, D3-2) and the communication director once (D4). We also had exchanges with 15 employees (M1–M15) from different backgrounds, with different language skills, and working in different departments. Their hierarchical status, age, gender and experience in the company varied, enabling us to capture the organization’s diversity. Table 2 details the profiles of the smart employees who we interviewed. Two researchers conducted the interviews. They were native German and French speakers, respectively, to give interviewees the opportunity to speak in their mother tongue (Welch and Piekkari, 2006). We recorded and then transcribed the interviews. At the end of the interview, we asked interviewees to complete a “language biography” detailing the languages they speak, at what level, under what conditions they change language(s), and to explain their relationship with foreign languages and foreign countries.

Finally, we participated in and observed a 90-minute executive committee meeting in January 2014. We were not allowed to record this meeting, so we took notes. We started by presenting our research project in French and German, and they reacted by saying in both languages, “Don’t repeat the same thing twice - you don’t need to translate, we understand”. Comments included, “Oh, you know, here you will hear the term “Mish-Mash” (smart jargon describing the mixing of languages). Members of the executive committee spoke fluent German and French, and they used both languages at will, with members starting to speak in the language with which they were most comfortable. For instance, after a short presentation in German from the German CEO about a new partnership, the French human resources director very naturally started talking about training and development in French and answered a number of questions in German. The technical director then explained in French how a problem had “escalated” during a “shop floor”. Alternating between German and French and inserting German words in French syntax continued throughout the meeting. However, our observation was limited to the executive committee, and therefore, was not representative of spoken translanguaging practices including vernaculars, as the executive committee members are generally highly educated people who speak fluent German and French. This is a limitation of our approach, insofar that our observation of dialogues between employees was limited to observing this executive committee, while most of our work was based on reported language experiences like the interviews.

It is important to consider the multilingual side of our research (Steyaert and Janssens, 2013). Although we have translated our citations into English for this article, we mentioned earlier that one of the researchers is French and the other one is German. Our verbatim are rough translations from the original spoken German and French. This had an impact on our research in terms of data collection, as interviewees may have expressed their views better in their native language, and even the interviewees’ language choice is meaningful. M10, a German quality product manager, chose to carry out the interview in French to show his good level in French and his strong sense of belonging to this French-German border area. For the analysis, we conducted most of our discussions in French. The German researcher speaks fluent French, and the French researcher has a good knowledge of German but is not fluent. This French-German background was very useful when analyzing translanguaging expressions. For instance, the German researcher could identify a translanguaging occurrence in French “Le planeur doit être maîtrisé” which makes no sense in French in this context, and which we would translate as “the glider must be controlled”. However, analyzing the expression from a German perspective led us to understand that “planeur” was a Gallicised version of “Planar”, a German word for a specific machine with an integrated work surface. Our multilingual background served as the starting point of this research and explains our interest in the question of multilingual practices during our first visit to the company.

In a second step, we collected internal documentation that the Director of Human Resources forwarded to us, including statistics on employee nationalities and dwellings, statistics on any language training offered, and corporate journals and documents about the launch of the new smart car model.

Secondary sources included newspapers (Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, 1994) and published academic articles (Dörrenbächer and Schulz, 2008) about the organization, its development and impact within the cross-border region. Dr Gregor Halmes, from the University of Saarland, had previously worked with local authorities as a member of the firm’s implantation team and he organized a seminar to share his experience with us. We learned of the strong support from the French Lorraine region and the German Saarland region for implementing the smart plant in the cross-border area of Hambach and the economic plans for its development. Local players on both sides of the border positively welcomed opening the firm in this economically devastated former mining area.

TABLE 1

Interviewees from the management team

Ecologically Oriented Data Analysis

To review all the collected data, we started by analyzing employee interviews and triangulated them with the management team interviews. To grasp the language ecology of smart and its modification through introducing a new foreign language, we reviewed our interviews via ecologically oriented data analysis using Kramsch and Whiteside’s (2008) levels of analysis. The way translanguaging links to history and space relates to our project and therefore constitutes our “situational maps” (Clarke, 2003), thus providing the initial framework that orients our analysis. We therefore examined the re-enactment of past language practices, replays of cultural memories relating to history and rehearsing potential identities connecting with space through translanguaging practices at smart. Through this analysis we developed relations among different elements to understand how global and local dynamics were linguistically intertwined in the smart plant.

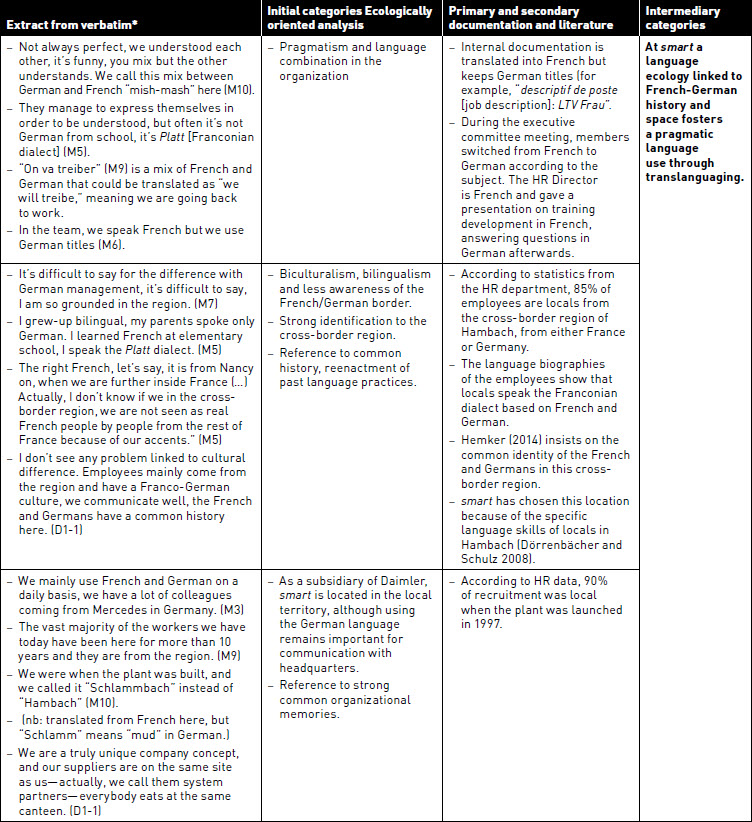

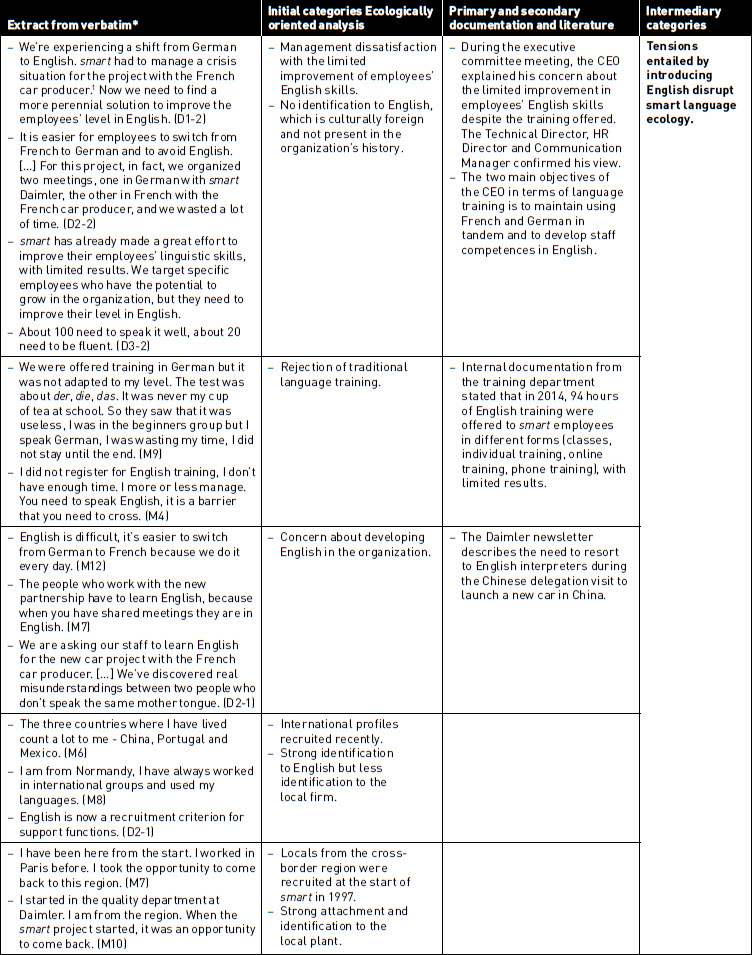

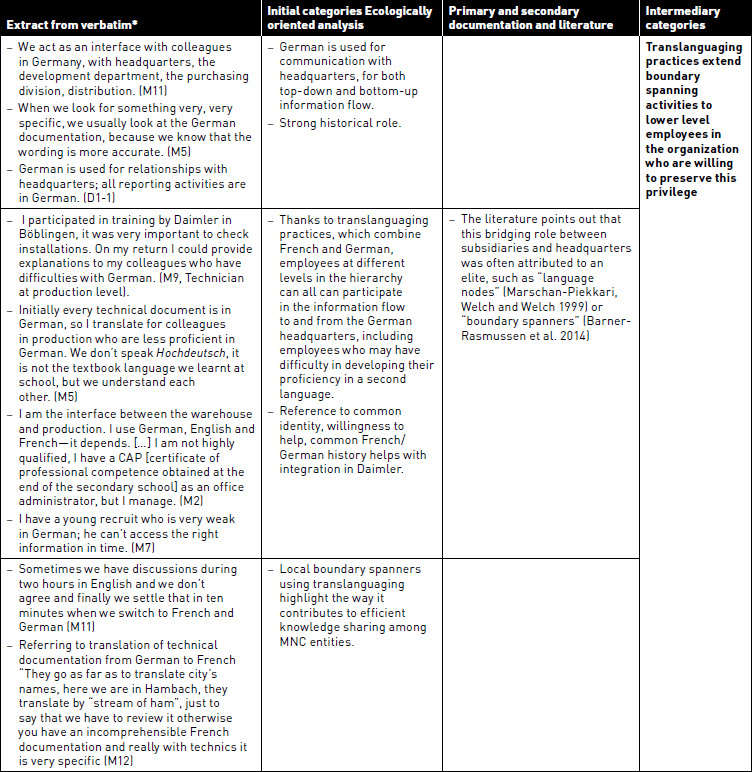

At a second level of triangulation, we compared the initial categories resulting from this first round of analysis (See Table 3, column “Initial Categories”) with the employees’ language biographies and internal and external documentation concerning the employees and the organization, data from our observation of the executive committee and literature on the subject. We modified these categories continually to include new evidence. We then systematically and thoroughly examined each piece of data for evidence of fitting the categories, and verbatim extracts or information from documentation. This second round of analysis led to developing intermediary categories that accounted for language practices at smart and the effect of introducing a foreign language on smart “language ecology”. A last round of constant comparisons between categories led to developing final categories. Table 3 introduces verbatim extracts, observations, internal and external documentation and the literature review that accounts for developing intermediary categories and Table 4 presents the development of these intermediary categories in final categories.

TABLE 2

Interviewees at smart, April 2014

TABLE 3

The development of intermediary categories[1]

TABLE 4

Final categories

Results

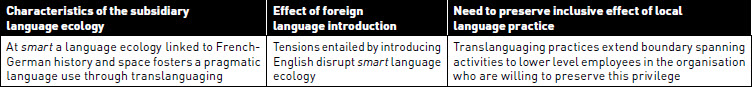

Our analysis revealed the characteristics of the subsidiary language ecology, the effect of introducing a foreign language on it and finally, the need to preserve the inclusive effect of these local language practices:

Characteristics of the Subsidiary Language Ecology:

At Smart a Language Ecology Linked to a French-German History and Space Fosters a Pragmatic Language Use Through Translanguaging

The language ecology at smart consists of French, German and dialectical variations such as Platt and Saarländisch, which employees use daily and even in combined forms along with other languages.

Employees most frequently use French and German. They carry out all reporting activities in German, which is the predominant language for communication with suppliers (90% of whom are German). For example, the development department initially creates technical information, in German. Therefore, bottom-up and top down information flow between smart and the headquarters is in German. Both the specific history of this cross-border region and the strong local anchorage of Daimler in its subsidiary’s area enhance a flexible and pragmatic approach to language that focuses on understanding rather than being limited by language barriers. This is even a common practice that the company calls “mish-mash”.

The highest level in the organization accepts translanguaging practices combining German and French. For example, during the executive committee, the German CEO asks for feedback on recruiting a specific profile for painting cars in German:

“Haben Sie den Chemieingenieur gefunden?” translates into English as: “Have you found the chemical engineer?”

The HR Director answers in German and French:

“Nicht jetzt. Es ist schwierig, on a rencontré un candidat de l’ENSIC (Engineering School Specialized in Chemistry) qui parlait allemand mais il ne veut pas s’installer dans la région”. Here, he starts speaking in German – “Not yet. It’s difficult” - then continues in French to say “we met a candidate from ENSIC, who speaks German but did not want to settle in the region”.

The HR Director combined French, German and the local vernacular Platt to achieve better communication between employees. The technician M9 explains how he uses German and Platt when he was in training at the headquarters to say: “Er sagnur wie de Machine zu regeln ist”. He told his colleagues that the teacher only told him how to adjust the machine. Sanur is the dialectal version for “Er sagt nur”, meaning “He only told us” in English. “De” is an utterance of the dialect to simplify the “der, die, das” declension system.

The Human Resource Director D1 confirms that French and German employees communicate easily in the firm: “I don’t see any problem linked to cultural difference. Employees mainly come from the region and have a Franco-German culture. We communicate well. The French and Germans have a common history here.” (D1-1)

M5 does not feel completely French but rather identifies himself as part of this cross-border region: “Real French people live, let’s say, from Nancy on, when we are further into France (…) Actually, I don’t know if we people from the cross-border region are seen as real French people by people from the rest of France because of our accents.”

The company even uses German and French on international projects. The new project developed jointly with the French partner highlights the role that local employees play. During meetings with “French people from Paris” and “Germans from Stuttgart”, conducted in English, local employees noticed misunderstandings that could have led to serious problems, for instance on the production line. They solved the issue by switching to French and translating information into German (M10 and D2-2 in Table 3). The references to “French people from Paris” and “Germans from Stuttgart” indicate that the local employees we interviewed differentiate themselves from other members of the project and see their working environment as a third space.

A language ecology analysis at the individual level reveals that these language practices that focus on intercomprehension to the detriment of grammatical rules occur because of the local employees’ bicultural and bilingual background. We noticed a strong attachment and a strong identification to this cross-border area in inhabitants from both sides of the border that was more evident than any sense of national belonging. The history of the territory where Hambach is located, the eastern cross-border part of France and German Saarland, explains this common identity that German and French employees on both side of the border share. This territory has alternatively been French and German throughout history. This common history started with The Treaty of Verdun, signed in August 843. This was the first of treaties that divided the Carolingian Empire into three kingdoms among the three surviving sons of Louis the Pious who was Charlemagne’s son. The French territory was under German rule from 1870 to 1918 and was again occupied by Germany during WW2.

Consequently, locals are often bilingual. They frequently have family links on the other side of the border and alternatively go shopping or go out in France or Germany. This strong identification to the cross-border region is inevitably linked to language practice. The employees’ language biographies highlight that their good level of French, German and local vernaculars results from past language practices linked to history. On this territory generations born between 1950 and 1970 spoke German with their grandparents, French with their parents and often use the Franconian dialect commonly called Platt, which is spoken on both sides of the border (Polzin-Haumann and Reissner, 2018).

The history of smart in this specific cross-border space explains why locals strongly identify and are attached to this organization. Dr Gregor Halmes, a former member of the company’s implementation team, explained that Daimler’s choice to set up its smart plant in Hambach was an economic rescue for this former mining region, which suffered from a high unemployment rate. Local cross-border programs provided financial support to install the site. Smart is locally integrated in the cross-border area of Hambach. The company has recruited a high number of locals. Smart is a “unique concept” (D1-1) that groups all its suppliers together on the same site, called “smartville”. The HR Director and the Communications Director (D2-1 and D4), who are originally from the region and witnessed this development before they started working at smart, recalled this. Technician M9 confirms: “It was a chance to be recruited by smart. We can be proud to work for a German car producer.”

At smart, there is a notably serene relationship to language. All employees want to be understood and are willing to adapt how they communicate even if they must combine French and German or use vernaculars and company speak. The employees’ ability to draw on their language repertories regardless of grammatical rules is a perfect example of translanguaging practices (Garcίa, 2009). Language ecology enables us to highlight how this pragmatic language use combines French and German and finds roots in the MNC unit’s strong embeddedness in this cross-border territory. We will now investigate how introducing English modifies this language ecology.

Effect Of Foreign Language Introduction

Tensions Entailed by Introducing English Disrupt Smart’s Language Ecology

The management team must modify translanguaging practices and introduce English for a new project with a French partner whose staff do not speak German, and to develop new international markets with countries such as China.

Although production line workers can continue to work using French alone, this is not the case for employees who are involved in new international projects, such as production managers and the quality and logistics department. Introducing English as a tool for the firm’s internationalization is particularly tricky for the management team. They perceive these constant retranslations to German and French as a waste and loss of time. (D2-2) referring to a project with a French car producer regrets: “For this project, in fact, we organized two meetings, one in German with smart Daimler, the other in French with a French car producer.”

Local employees are generally reticent to learn English and reject standard forms of training. Management was not satisfied with the limited improvement of employees’ English skills and considered alternative training methods. They have solved this difficulty to introduce English with a shift in recruitment sources, opening posts to English-speaking candidates with international profiles who are difficult to find in this area.

Employees’ strong feeling of belonging to this cross-border region and to smart mentioned above, explains this rejection of English. Employees can communicate easily by switching from German to French, and do not feel the need to enroll in English classes.

(M9) confirms this view: “I did not register for English training. I don’t have time and I managed by using German.”

Employees fear introducing English, even Director (M7) confides: “I am a bit afraid that if reporting switches to English, then it will be more difficult. We will not deliver the same message.”

Similarly, locals fear a status loss (Neeley, 2013) and with introducing English, management starts reallocating some tasks. (M9) explains: “Then we share English suppliers. We reallocate them to colleagues who master English better.”

English is not a logical part of smart language ecology and it disrupts it by raising fear among employees. Strongly identifying with a common space and history drawing on German and French language repertories leaves little place for English. Consequently, employees are reluctant to revert to this language repertory and we rarely observed English use in translanguaging practices at smart in spite of employees’ willingness to make themselves understood. We noticed few insertions of English words in our exchanges with our respondents, (M11) only talked about “Denglish” to describe English use at Daimler and (M7) mentions a shop floor to refer to a weekly meeting; whereas, employees regularly combined German and French during our interviews. However, recruiting new international profiles using English may change this tendency in the future.

We will now investigate the benefits of these translanguaging practices at the organizational level.

The Need to Preserve the Inclusive Effect of Local Language Practices

Translanguaging Practices Extend Boundary Spanning Activities to Lower Level Employees in the Organization Who Are Willing to Preserve This Privilege

Translanguaging practices enhance cooperation and knowledge transfer within the organization. Local employees use this pragmatic approach to languages that prioritizes how people understand them above all else to make sense and convey the right message from Daimler to their French colleagues at smart. Local French and German employees perceive themselves as an interface between general services like R&D, the purchasing department at the German headquarters and the local plant in this specific cross-border region. From this perspective, using translanguaging offers a boundary-spanning role to local employees. We noticed that the pragmatic approach to language combination and breaking free from traditional grammatical rules enables less-qualified people with less responsibility in the hierarchy to take part in the international dialogue. Employees from modest social backgrounds who are not used to attending standard language classes communicate successfully through these language practices. They learn through language practice but feel unable to learn English with standard training in the classroom.

We define boundary-spanning activities here as Barner-Rasmussen et al. (2014) conceptualized them, i.e. as four functions: exchanging information, linking previously disconnected individuals, facilitating (i.e. helping members of two groups to understand each other) and intervening, meaning participating in inter-unit interaction to resolve misunderstandings. Our data clearly show that local employees help convey information such as development instructions from the headquarters to the French-speaking production workers. They help people from different groups understand each other and they intervene by solving misunderstandings (See M10 comments on the project team linked to the French car producer). Technicians or employees from production (M6) use their command of German and French to share the information they have received with their colleagues. For instance, a French technician (M5) in the process department checks the suppliers’ technical translations from German to French. Translations are carried out by students and are often inaccurate:

“We give the suppliers a hand by helping them to translate correctly. For Germans it’s not always easy to translate this, especially technicians. I just supervised the new documentation. For example, they translated the term for the central part of the plant, which we call Kern Bereich [central zone] as “fork from kernel.”

However, these employees do not have any officially recognized proficiency in German: “They manage. They make themselves understood even if they are not qualified” (M6). M9 stresses that he was not good at German at school, and did not master declensions, so he was assigned to the beginner level when he took a test for professional German training, despite his ability to speak German. This linking role between global and local appears as a key competence at smart, where Daimler AG Corporate culture remains strong. As we mentioned earlier, smart follows Daimler AG processes and works with the same German suppliers. The reference documentation is in German and the available translations are not accurate enough to give a clear idea of the specific technical expertise linked to the organization’s context. All our respondents, whatever their level in the hierarchy, use accurate vocabulary when it comes to technical issues in auto development or when they need to obtain the correct information from suppliers or maintenance firms. Employees do not translate all words into French because the team still understands them. In parallel, incorporating technical German vocabulary into French or a local dialect helps convey the correct information to colleagues who have a weaker command of German. This helps employees foster knowledge-sharing between Daimler’s head office and its subsidiary. This capacity is not limited to the management group or to people with multiple qualifications.

Again, past common practices and a common identity make it possible to accept practices that management only authorizes in smart’s specific language ecology. They perceive that introducing English within the organization weakens the key role they play in communication between the smart plant and Daimler, and they feel threatened by this change. To resist this, management insists on the key contribution of their French-German skills even during English speaking meetings. (M11) explains: “Sometimes we have discussions during two hours in English and we don’t agree and finally we settle that in ten minutes when we switch to French and German.” Locals may experience a status loss (Neeley, 2013) if the organization’s language ecology becomes more influenced by globalization than by local patterns.

Discussion

An interdisciplinary approach that brings ecolinguistics and sociolinguistics to the IB realm allows us to account for disrupting highly engrained linguistic practices in a company’s subsidiary due to introducing English. Through a language ecology approach based on the analytical dimension of history and space, we explain how the strong identification of employees to this context renders translanguaging practices performative. This situation grants locals with a specific role of boundary-spanner with headquarters and leads to rejecting using English. Our study reveals that introducing a new foreign language in this specific language ecology disrupts the latter and is a source of tension for employees who are unwilling to change practices that are so embedded in their daily life. The challenge the organization faces is to preserve these practices that are linked to smart’s specific language ecology while introducing English. Welch and Welch (2018) refer to this as preserving the organization’s language operative capacity. This means harnessing the linguistic potential of every employee according to the context.

Through this study, we answer the call for interdisciplinary approaches to study language use in IB (Brannen, Piekkari and Tietze, 2014) and the need to reconceptualize language (Janssens and Steyaert, 2014; Angouri and Piekkari, 2018) to understand how local and global interplays with language practice development within MNCs.

Our first contribution is to show how translanguaging practices are embedded in the subsidiary’s region and incorporated in people’s everyday use. Understanding the language ecology of smart teaches us that language practices find their origin in the interplay between the strength of the common French-German history in this specific space, its influence on employees’ linguistic skills and sense of belonging and the need to speak German to communicate with Daimler Headquarters. In this respect, we confirm the relevance of Janssens and Steyaert’s (2014) multilingual franca concept (a negotiated approach to language where speakers use multiple linguistic resources to make themselves understood) and illustrate it empirically through a case study approach. However our study reveals that the linguistic environment of a subsidiary has to be taken into account when introducing a new language to foster its organizational acceptance (Bordia and Bordia, 2015) and that these analyses should not limit themselves to national language.

Our second contribution is highlighting the inclusive role that these translanguaging practices play. Breaking free from grammatical rules, combining French, German and vernacular languages allows less qualified people from less privileged social backgrounds to participate in the international dialogue with headquarters and act as boundary spanners. This finding is important because prior to our study these boundary-spanning roles (Barner-Rasmussen et al., 2014) and language nodes (Marschan-Piekkari, Welch and Welch, 1999) had only been observed among relatively privileged people occupying management positions. This possibility for people at low hierarchical levels to communicate at an international level shows that the language faultline between blue- and white-collar workers (Barner-Rasmussen and Aarnio, 2011) becomes blurred in some contexts. This offers new opportunities for promoting language diversity within MNCs (Church-Morel and Bartel-Radic, 2016).

This inclusive role of the Platt vernacular is remarkable in the French-German region of Hambach, because we can observe the opposite phenomenon in some other close cross-border areas. In other language contact situations like in Switzerland (Davoine, Schroeter and Stern, 2014) or Luxembourg (Langinier and Froehlicher, 2018), the language border between the local Germanic languages and French is negotiated in another way, for instance by using the local language to exclude newcomers from the conversation, in some cases.

Conclusion

Drawing on the concept of language ecology, we suggest that global and local dynamics interact to co-construct specific language practices in an MNC subsidiary located in a cross-border area. We show how introducing a foreign language can affect this balance and how a specific subsidiary’s language ecology destabilizes the benefits that these local multilingual practices generate.

Research Implications

The knowledge of subsidiaries’ language ecologies opens avenues for multilingual organizations to better manage linguistic diversity within MNCs, especially at the subsidiary level. This approach makes it possible to consider neglected communication practices for which management does account when the analysis is restricted to national languages. We think that more observation of “language in use” would be a fruitful avenue for research in International Business. Analyzing language practices in other MNC units would help to better understand the extent of our findings in other contexts. Finally, developing sociolinguistics in terms of methodology would also be of interest, and particularly analyzing utterances and their meaning in relation to communication practices in the MNC.

Management Implications

Introducing English for smart’s internationalization modifies the organization’s language ecology and modifies its harmonious translanguaging practices. This situation calls for leadership to approach internationalization carefully in terms of training and language policies. Leaders risk depriving their organization of efficient communication practices if they are too strict about imposing English. At the same time, they need to find innovative ways to improve their employees’ English skills while respecting their environment’s language ecology and helping it to evolve intelligently. In terms of training, Bordia and Bordia (2015) drawing on Jessner (1999), show how metalinguistic methods could help employees mastering two languages to learn a third one more easily. Recruiting employees from diverse horizons and backgrounds may be a way to foster a change in language ecology and introduce English softly while enhancing diversity in the organization.

Parties annexes

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank warmly our three anonymous reviewers and our editors Bachir Mazouz and Patrick Cohendet for their insightful comments.

We are grateful to our research fellows from the Groupe de Recherche Transfrontalières et Interdisciplinaires (GRETI), who worked with us on the data collection for this project. We also thank smart and its employees for giving their time for interviews.

Biographical notes

Hélène Langinier is Associate Professor at EM Strasbourg – University of Strasbourg, France. She is member of the Research Lab Humanis. She teaches and conducts research in the field of intercultural management, linguistic diversity and expatriates’ adjustment. She manages personal and professional development for international students. She started her career in human resources in an international audit and advisory firm in Luxembourg and Berlin where she recruited and managed international mobility. She is board member of the Groupe d’études Management et Langage (GEM&L) and member of the GRETI.

Sabine Ehrhart is professor for Ethnolinguistics teaching in different programs (Bachelor of Education, Master of Border Studies and School of Doctoral Studies) at Luxembourg University, a trilingual institution. She is member of the research Lab MLing at Luxembourg University and the international research team GRETI with partners from her direct environment (Luxembourg, Lorraine and Saarland). Her interest in language ecology and communicative strategies for international settings generated cooperation projects (Tempus, Erasmus +, AUF) with partners in Africa (Madagascar, Cabo Verde), Asia (Siberia) and the South Pacific (New Caledonia).

Note

-

[1]

We are not authorised to use the name of the French partner.

Bibliography

- Angouri, Jo.; Piekkari, Rebecca. (2018). “Organising multilingually; setting an agenda for studying language at work”, European Journal of International Management, Vol. 12. N° 1/2, p. 8-27.

- Barner-Rasmussen, Wilhelm; Aarnio, Christoffer (2011). “Shifting the faultlines of language: A quantitative functional-level exploration of language use in MNC subsidiaries”, Journal of World Business, Vol. 46, N° 3, p. 288-295.

- Barner-Rasmussen, Wilhelm; Ehrnrooth, Mats; Koveshnikov, Alexei; Mäkelä, Kristiina (2014). “Cultural and language skills as resources for boundary spanning within the MNC”, Journal of International Business Studies, Vol. 45, N° 7, p. 886-905.

- Biber, Douglas; Finegan, Edward (Eds) (1994). Sociolinguistic Perspectives on Register, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Bordia, Sarbari.; Bordia, Prashant; (2015). “Employees’ willingness to adopt a foreign functional language in multilingual organizations: The role of linguistic identity”, Journal of International Business Studies, Vol. 46, N° 4, p. 415-428.

- Brannen, Mary-Yoko; Piekkari, Rebecca; Tietze, Susanne (2014). “The multifaceted role of language in international business: Unpacking the forms, functions and features of a critical challenge to MNC theory and performance”, Journal of International Business Studies, Vol. 45, N° 5, p. 495-507.

- Canagarajah, Suresh (2012). Translingual Practice: Global Englishes and Cosmopolitan Relations, London: Routledge, 224 p.

- Church-Morel, Amy; Bartel-Radic, Anne (2016). “Skills, identity and power: The multifaceted concept of language diversity”, Management International, Vol. 21, N° 1, p. 12-24.

- Clarke, Adele E. (2003) “Situational Analyses: Grounded Theory Mapping After the Postmodern Turn,” Symbolic Interaction 26 (4): 553-76.

- Davoine, Eric; Schroeter, Oliver Christian; Stern, Julien (2014). “Cultures régionales des filiales dans l’entreprise multinationale et capacités d’influence liées à la langue: Une étude de cas”, Management International, Vol. 18, p. 165-177.

- Dörrenbächer, Peter; Schulz, Christian. (2008). “The organisation of the production process: The case of Smartville”, in Pellenbarg, Piet and Wever, Egbert (Eds), International Business Geography: Case Studies of Corporate Firms. London: Routledge, p. 83-96.

- Fill, Alwin; Mühlhäusler, Peter (Eds) (2006). Ecolinguistics Reader: Language, Ecology and Environment, London: A&C Black, 306 p.

- Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (1994). “Politische Entscheidung für ein Swatch-Auto aus Frankreich”, 14th December, p. 23.

- Fredriksson, Riika., Barner-Rasmussen, Wilhelm. & Piekkari, Rebecca (2006). The multinational corporation as a multilingual organization: The notion of common corporate language. Corporate Communications: An International Journal, Vol. 11 N° 4, p. 406-423.

- Gaibrois, Claudine (2018) ‘“It crosses all the boundaries”: Hybrid language use as empowering resource’, European Journal of International Management, Vol. 12 N° 1-2, p. 82-110.

- Garcia, Ofelia (2009). Bilingual Education in the 21st Century: A Global Perspective, Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 496 p.

- Garcia, Ofelia; Flores, Nelson; Woodley Homonoff, H. (2012). “Transgressing monolingualism and bilingual dualities: Translanguaging pedagogies”, in Yiakoumetti, A. (Ed.), Harnessing Linguistic Variation to Improve Education, Whitney: Peter Lang, p. 45-75.

- Glaser, Barney; Strauss, Anselm (1967). The Discovery of Grounded Theory, London: Weidenfeld and Nicholson, 284 p.

- Harzing, Anne-Will, Pudelkpo, Markus (2013). “Language competencies, policies and practices in multinational corporations: A comprehensive review and comparison of Anglophone, Asian, Continental European and Nordic MNCs”, Journal of World Business, Vol. 48, N° 1, p. 87-97.

- Harzing, Anne-Wil; Köster, Kathrin; Magner, Ulrike (2011). “Babel in business: The language barrier and its solutions in the HQ-subsidiary relationship”, Journal of World Business, Vol. 46, N° 3, p. 279-287.

- Itani, Sami; Järlström, Maria; Piekkari Rebecca (2015). “ The meaning of language skills for career mobility in the new career landscape”, Journal of World Business, Vol. 50, N° 2, p. 368-378.

- Janssens, Maddy; Steyaert, Chris (2014). “Re-considering language within a cosmopolitan understanding: Toward a multilingual franca approach in international business studies”, Journal of International Business Studies, Vol. 45, N° 5, p. 623-639.

- Jaussaud, Jacques; Mayrhofer, Ulrike (2014). “Les tensions global-local: l’organisation et la coordination des activités internationales”, Management International, Vol. 18, N° 1, p. 18-25.

- Jessner, Ulrike (1999). “Metalinguistic awareness in multilinguals: Cognitive aspects of third language learning”, Language Awareness, Vol. 8, N° 3-4, p. 201-209.

- Kramsch, Claire; Whiteside, Anne (2008). “Language ecology in multilingual settings. Towards a theory of symbolic competence”, Applied Linguistics, Vol. 29, N° 4, p. 645-671.

- Langinier, Hélène; Froehlicher, Thomas (2018). “Context matters: Expatriates’ adjustment and contact with host country nationals in Luxembourg”, Thunderbird International Business Review, Vol. 60, N° 1, p. 105-119.

- Lauring, Jakob, (2011), “Intercultural organizational communication: The social organizing of interaction in international encounters”, Journal of Business Communication, Vol. 48, N° 3, p. 231-55.

- Lejot, Eve, (2015), Pratiques plurilingues en milieu professionnel international, entre politiques linguistiques et usages effectifs. Frankfurt-am-Main: Peter Lang, 396 p.

- Lincoln, Yvonna S.; GUBA, Egon G. (1985). Naturalistic Inquiry, London: Sage, 416 p.

- Logemann, Minna and Piekkari Rebecca (2015)‚ “Localize or local lies? The power of language and translation in the multinational corporation”, Critical Perspectives on International Business, Vol. 11, N° 1, p. 30-53.

- Lüdi, Georges., Höchle, Katharina; Yanaprasart, Patchareerat. (2013), “Multilingualism and diversity management in companies in the Upper Rhine Region.” In A-C. Berthoud, F. Grin and G. Lüdi (eds), 2013, Exploring the dynamics of multilingualism: The DYLAN project. Amsterdam: The John Benjamins Publishing Company, p. 59-82.

- Luo, Yadong; Shenkar, Oded (2006). “The multinational corporation as a multilingual community: Language and organization in a global context”, Journal of International Business Studies, Vol. 37, N° 3, p. 321-339.

- Makoni, Sinfree; Pennycook, Alastair (2006). Disinventing and Reconstituting Languages, Clevedon: Multilingual Matters, 272 p.

- Marschan-Piekkari, Rebecca; Welch, Denice; Welch, Lawrence (1999). “In the shadow: The impact of language on structure, power and communication in the multinational”, International Business Review, Vol. 8, N° 2, p. 421-440.

- Mayrhofer, Ulrike; Very, Philippe (Eds) (2013). Le management international à l’écoute du local, Paris: Editions Gualino, 350 p.

- Neeley, Tsedal (2013). “Language matters: Status loss and achieved status distinctions in global organizations”, Organization Science, Vol. 24, N° 2, p. 476-497.

- Neeley, Tsedal; Dumas, Tracy (2016). “Unearned status gain: Evidence from a global language mandate,” Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 59, N° 1, p. 14-43.

- Neeley, T Sedal,.(2017). The language of global success: how a common tongue transforms multinational organizations, Princeton University Press, New Jersey, 200 p.

- Peltokorpi, Vesa; Vaara, Eero (2014). “Knowledge transfer in multi-national corporations: Productive and counterproductive effects of language-sensitive recruitment”, Journal of International Business Studies, Vol. 45, N° 5, p. 600-622.

- Piekkari, Rebecca; Vaara, Eero; Tienari, Janne; Säntti, Risto (2005). “Integration or disintegration? Human resource implications of a common corporate language decision in a cross-border merger”. International Journal of Human Resource Management, Vol. 16, N° 3, p. 330-344.

- Polzin-Haumann, Claudia; Reissner, Christina (2018). “Language and language policies in Saarland and Lorraine: Towards the creation of a transnational space?”, in Jańczak, Barbara Alicja (Ed.), Language Contact and Language Policies Across Borders: Construction and Deconstruction of Transnational and Transcultural Spaces, Berlin: Publisher, pp. 45-55.

- Makoni, Sinfree; Pennycook, Alastair (2006). Disinventing and Reconstituting Languages, Clevedon: Multilingual Matters, 272 p.

- Steyaert, Chris; Janssens, Maddy (2013). “Multilingual scholarship and the paradox of translation and language in management and organization studies”, Organization, Vol. 20, N° 1, p. 131-142.

- Steyaert, Chris; Ostendorp, Anja; Gaibrois, Claudine (2011). “Multilingual organizations as ‘linguascapes’: Negotiating the position of English through discursive practices”, Journal of World Business, Vol. 46, N° 3, p. 270-278.

- Tietze, Susanne (2008). International Management and Language, London: Routledge, 264 p.

- Tietze, Susanne; Holden, Nigel; Barner-Rasmussen, Wilhelm (2016). “Language use in multinational corporations: The role of special languages and corporate idiolects”, in Ginsburgh, V. and Weber, S. (Eds), The Palgrave Handbook of Economics and Language, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 312-341.

- Van Lier, Leo (2006). The Ecology and Semiotics of Language Learning: A Sociocultural Perspective (Vol. 3). Amsterdam: Springer Science & Business Media.

- Wei, Li (2011). “Moment analysis and translanguaging space: Discursive construction of identities by multilingual Chinese youth in Britain”, Journal of Pragmatics, Vol. 43, N° 5, p. 1222-1235.

- Welch, Catherine; Piekkari, Rebecca (2006). “Crossing language boundaries: Qualitative interviewing in international business”, Management International Review, Vol. 46, N° 4, p. 417-437.

- Welch, Denice E.; Welch, Lawrence S. (2018). “Developing multilingual capacity: A challenge for the multinational enterprise”, Journal of Management, Vol. 44, N° 3. p. 854-869.

Parties annexes

Notes biographiques

Hélène Langinier est enseignant-chercheur à l’EM Strasbourg : Elle est membre du laboratoire de recherche Humanis. Elle enseigne et mène des projets de recherches dans les domaines du management interculturel, de la diversité linguistique et de l’adaptation des expatriés. Elle est responsable du développement personnel et professionnel des étudiants internationaux. Elle a commencé sa carrière en ressources humaines chez un Big Four à Luxembourg et Berlin en tant que recruteur puis responsable de la mobilité internationale. Elle est membre du conseil d’Administration du Groupe d’études Management et Langage (GEM&L) et membre du GRETI (Groupe de Recherche Transfrontalières et Interdisciplinaires).

Sabine Ehrhart est professeure en Ethnolinguistique à l’Université du Luxembourg et enseigne dans les programmes Bachelor (Sciences de l’Education), Master Border Studies et à l’Ecole Doctorale de cette institution trilingue. Elle est membre du laboratoire de recherche MLing à l’Université du Luxembourg et du groupe de recherche international GRETI avec des partenaires de son environnement géographique immédiat (Luxembourg, Lorraine et Sarre). Elle a représenté l’écolinguistique et les stratégies de communication en contexte international dans différents projets de recherche (Tempus, Erasmus +, AUF) avec des partenaires en Afrique (Madagascar, Cap Vert), en Asie (la Sibérie) et dans le Pacifique Sud (Nouvelle-Calédonie).

Parties annexes

Notas biograficas

Hélène Langinier es profesora de investigación del EM Strasbourg (parte de la Universiad de Estrasburgo). Es miembro del laboratorio de investigación Humanis. Imparte cursos y lleva a cabo proyectos en la gerencia intercultural, la diversidad lingüística y la adaptación de los expatriados. Es responsable del desarrollo personal y profesional de los estudiantes internacionales. Empezó su carrera en Recursos Humanos en uno des los Big Four de Luxemburgo y en Berlín como reclutadora y encargada de la movilidad internacional. Es miembro del consejo de Administración del Grupo de estudio de Management y Idioma (GEM&L) y miembro del GRETI (Grupo de investigación transfronterizo e interdisciplinario).

Sabine Ehrhart es profesora de etnolingüística en la Universidad trilingüe de Luxemburgo. Enseña en los programas de Bachelor (Ciencias Educativas), Master of Border Studies y en la Escuela de Doctorado. Forma parte del laboratorio de investigación MLing de la Universidad de Luxemburgo y del grupo de investigación GRETI con socios del entorno geográfico (Luxemburgo, Lorena y Sarre). Ha representado la ecolingüística y las estrategias de comunicación en contextos internacionales en diferentes proyectos de investigación (Tempus, Erasmus+, AUF) con socios en África (Madagascar, Cabo Verde) en Asia (Siberia) y en el Pacífico Sur (Nueva Caledonia).

Liste des tableaux

TABLE 1

Interviewees from the management team

TABLE 2

Interviewees at smart, April 2014

TABLE 3

The development of intermediary categories[1]

TABLE 4

Final categories

10.7202/1027871ar

10.7202/1027871ar