Résumés

Summary

This article discusses the potential advantages of large scale, government administered workplace surveys and the limitations of these surveys in the past. It then reviews the 1995 AWIRS (Australia), the 1998 WERS (U.K.), and the 1999 WES (Canada) in accordance with how well they appear to have succeeded in overcoming these limitations, and, more generally, with their implications for the conduct of industrial relations (IR) research. It is argued that the 1995 AWIRS does not appreciably overcome the limitations of previous surveys. In contrast, the 1998 WERS has yielded a substantially higher quality data set, although it also does not completely overcome the limitations of its predecessors. Finally, the 1999 WES promises an even higher quality data set, but is primarily a labour market and productivity survey rather than an IR survey, and could even portend a “bad moon rising” for Canadian IR research.

Résumé

Depuis 1995, Statistique Canada a conçu puis mené une enquête nationale visant à corriger le manque de données sur les lieux de travail et la première vague de collecte de données a été complétée en 1999. L’Enquête sur le lieu de travail et les employés (ELTE) recueille des données tant chez les salariés que chez les employeurs dans 6 000 lieux de travail au Canada, fournissant ainsi un ensemble de données sur une grande échelle permettant d’établir des liens entre les réponses fournies par les employés et les employeurs. Bien qu’elle soit unique en Amérique du Nord, de telles enquêtes ont été effectuées au Royaume-Uni et en Australie. Au Royaume-Uni, la plus récente est celle de 1998, intitulée Work and Employment Relations Survey (WERS), couvrant les travailleurs, les employeurs et des représentants des travailleurs (syndiqués et non syndiqués) dans près de 3 000 lieux de travail. En Australie, l’enquête Australian Work and Industrial Relations Survey (AWIRS) date de 1995 et elle couvrait des travailleurs, des employeurs et des représentants syndicaux dans plus de 3 000 lieux de travail.

Cet essai se veut une appréciation de l’utilité et des implications de ces enquêtes dans le champ des relations industrielles et cherche à vérifier dans quelle mesure cette enquête de Statistique Canada (ELTE) s’avèrera une « aurore nouvelle » ou le « début d’une mauvaise lune » pour la recherche dans le domaine au Canada. Ainsi, je poursuis cette appréciation dans une perspective de recherche et non du point de vue d’un décideur politique. Je retiens pour ce faire deux volets : (1) celui des relations du travail, c’est-à-dire des structures syndicales, du rôle et de l’efficacité des syndicats et de la négociation collective, et (2) celui de la relation d’emploi en général et, d’une manière plus spécifique, celui de l’organisation du travail et des pratiques de gestion des ressources humaines qui y sont reliées.

Je commence par une analyse des avantages des enquêtes sur une large échelle administrées par le gouvernement, des limites de quelques enquêtes antérieures, plus particulièrement celles du Royaume-Uni (WIRS) et de l’Australie (1990). Je continue avec celle de l’Australie (1995), du Royaume-Uni (1998), enfin celle du Canada (1999) en me demandant toujours si elles paraissent surmonter les limitations mentionnées ou, de façon plus générale, en m’interrogeant sur la qualité des données qu’elles génèrent pour la recherche en relations industrielles. Pour chacune d’entre elles, je fournis une esquisse de sa structure, donne une ventilation de son contenu et procède à son analyse pour enfin chercher à comprendre ses échecs et ses succès en conformité avec le processus qui a servi à son élaboration et également en conformité avec la composition de l’équipe de recherche, son mandat et sa structure d’imputabilité.

À mon avis, l’enquête australienne de 1995 (AWIRS) ne surmonte pas de façon appréciable les limites des enquêtes antérieures. Tout en présentant un contenu de relations du travail et de relations avec les employés très exhaustif, elle fournit des données descriptives utiles. Cependant, les données s’avéreraient plutôt de piètre qualité pour la conduite de recherches multivariées. Le mandat de l’équipe de recherche (AWIRS) semble avoir été conçu en vue de générer des données pour les décideurs politiques, sans peu d’implication pour la recherche universitaire.

Au contraire, l’enquête britannique de 1998 (WERS) a produit un ensemble de données de qualité beaucoup supérieure, tant au sujet des relations du travail que des relations avec les employés. Elle a aussi généré des données descriptives intéressantes et de meilleure qualité pour l’analyse multivariée, quoique des lacunes soient apparues au plan des variables contextuelles, telles celles reliées à la technologie et à la performance. La haute qualité de cet ensemble de données pour la recherche scientifique serait attribuable à l’implication remarquable des chercheurs universitaires dans la configuration de l’enquête.

Enfin, comme les résultats de l’enquête canadienne de 1999 (ELTE) commencent à être disponibles au moment de la rédaction du présent article, j’en fais donc une analyse à caractère prospectif. L’enquête promet un ensemble de données de meilleure qualité que celle de 1998 (WERS), mais elle s’adresse plus au marché du travail et à la productivité qu’aux relations industrielles, ce qui est conforme au paradigme « managérial » qui semble prédominer au gouvernement fédéral. Seulement 6 % de cette enquête aborde le sujet des relations du travail. Apparemment, ceci reflète la raison de l’enquête qui est de fournir des données jusqu’alors manquantes aux décideurs politiques. J’analyse quelques-unes des implications de cette enquête en argumentant que, bien qu’elle puisse représenter une « aurore nouvelle » pour les chercheurs qui s’intéressent aux politiques économiques et de marché du travail, elle peut aussi signifier un « début de mauvaise lune » pour la recherche au Canada en relations industrielles et dans le domaine en général.

Resumen

Este artículo discute las ventajas potenciales de las encuestas de gran escala administradas por el gobierno en los centros de trabajo y los limites que estas encuestas encontraron en el pasado. Se revisan así las encuestas AWIRS (Australia, 1995), WERS en el Reino Unido (1998) y WES en Canada (1999), según como ellas han logrado superar estas limitaciones, y de manera más general, las implicaciones respecto a la conducción de la investigación en Relaciones industriales. Se argumenta aquí, que la encuesta AWIES-1995 no superó considerablemente las limitaciones de las encuestas precedentes. En contraste, la encuesta WERS-1998 provee una calidad sustancialmente más elevada del conjunto de datos a pesar que tampoco logra superar los limites de sus predecesores. Finalmente, la encuesta WES-1999 anuncia una calidad de datos aun más elevada pero es ante todo una encuesta del mercado de trabajo y de la productividad mas que une encuesta de relaciones industriales, y puede ser augurio de un « falso claro de luna » para la investigación canadiense en relaciones industriales.

Corps de l’article

Canadian industrial relations (IR) scholars have over the past few decades found themselves in a lacunae of sorts. There has been considerable hyperbole about changes in employer practices, the organization and nature of work, and the role and effectiveness of unions. But researchers have lacked a large scale, reliable and comprehensive data set to establish the nature, extent, and implications of these changes across workplaces. Instead, they have typically had to rely on smaller scale workplace surveys addressing a limited number of research questions, and often suffering from weak response rates, small sample sizes, or serious sampling limitations. In effect, these studies allow (at least in some instances) for “high fidelity,” yielding good data for addressing specific research questions. But they have typically been lacking in “band width,” failing to establish the broader picture needed to establish what has really changed or to provide the kind of broad-based, comprehensive data set necessary for more systematic multivariate research. The lack of such data has not just been a problem for academics. It has also been a problem for policy makers, who have been unable to obtain reliable information on a whole series of questions, from the nature and extent of employer training practices to the prevalence of family friendly policies.

Beginning in 1995, Statistics Canada set about to design a national survey intended to address the lack of workplace level data, completing the first wave of data collection in 1999. Referred to as the Workplace and Employee Survey, or WES, this survey collected data from both employees and employers in over 6000 Canadian workplaces, thus providing a large scale data set in which it is possible to link employee and employer responses. Although unique to North America, similar large scale data sets have been collected in both the U.K. and Australia. In the U.K, the 1998 Work and Employment Relations Survey, or WERS (Cully et al. 1999; Millward, Bryson and Forth 2000) surveyed workers, employers, and worker representatives (union and nonunion) in close to 3,000 workplaces. In Australia, the 1995 Australian Work and Industrial Relations Survey, or AWIRS (Morehead et al. 1997), surveyed workers, employers, and union representatives in just over 3000 workplaces. The former follows three earlier Work and Industrial Relations Surveys, or WIRS, conducted in 1980, 1984, and 1990 (e.g., Millward et al. 1992), while the latter follows the first AWIRS, conducted in 1990 (Callus et al. 1991). Thus, although the WES is the first of its kind in North America, there is considerable precedent for large scale government administered workplace surveys in Britain and Australia.

An important rationale for these surveys has been to provide data for use by policy makers. Indeed, the WES appears to have been designed to fill policy relevant data gaps, and as such the plan is to release a series of reports addressing specific policy issues rather than issuing a single book on the findings. The 1995 AWIRS also appears to have been driven by policy concerns,[1] and these concerns also played some role, albeit a significantly lesser one, in the design of the 1998 WERS. The purpose of this paper, however, is to address the usefulness and implications of these surveys for the field of IR, and ultimately to establish whether the WES is likely to represent a “new dawn” or a “bad moon rising” for Canadian IR research. Thus, I evaluate these surveys from an academic’s rather than a policy maker’s perspective.

Industrial relations, and hence what constitutes IR research, can be defined in a number of ways, ranging from the very broad (all aspects of people at work) to the very narrow (labour law, unions, and collective bargaining). For purposes of this paper, I opt for a definition that falls between the broad and the narrow, as the study of the relations between labour (union and nonunion) and management and the context within with these parties interact (see Godard 1994a: 4-24; 2000: 3-10). This definition encompasses the two topic areas that have become central to the field: (1) labour relations, including the structure, role and effectiveness of unions and collective bargaining, and (2) employment relations, especially the organization of work and related human resource management practices. I thus focus on the value of the three surveys for addressing these two areas. This provides reasonable bounds for the analysis, although it is acknowledged that the surveys (especially the WES) contain data on a variety of labour market issues that would normally fall under a broader definition of IR and that, if adopted, might lead to a somewhat different assessment.

I begin by considering the potential advantages of large scale government administered surveys and the extent to which these surveys appear to have succeeded in the past. Next, I assess the 1995 AWIRS and the 1998 WERS, the data from which have been reported in book form and have now been available for academic use for over three years and one year, respectively. Finally, I turn to the WES. At the time of this writing the WES data were only just beginning to be reported (Statistics Canada 2001), so the analysis of this survey is largely prospective, based on the design of the survey.

Five questions underlie the analysis, and, based on this analysis, are returned to in the concluding section. First, do national, multi-workplace surveys, and the WES in particular, provide high quality data for assessing the extent, nature, and implications of change in IR? Second, do these surveys provide high quality data for multivariate research that enables us to obtain a better understanding of when and why changes appear to be occurring? Third, are government surveys more effective than independently conducted (i.e., by one or a few academics) surveys as means of obtaining quality data to serve the first two of these purposes? Fourth, what are the broader implications of these data sets for the type and quality of research produced by IR scholars? Finally, what might be done to improve on these data sets?

The prospects and problems of large scale, government surveys

Large scale, government sponsored workplace surveys offer a number of potential advantages, both as a means of “mapping” industrial relations and identifying changes therein, and as a means of obtaining high quality data for multivariate analysis. First, the official status of these surveys, coupled with a greater ability to guarantee confidentiality, encourages higher response rates than for independently conducted surveys. For example, in the AWIRS and the WIRS/WERS series, participation rates have either approximated or exceeded 80 percent, and in the 1999 WES, this rate exceeded 90 percent (see below). In contrast, the highest response rates obtained for independently conducted surveys appear to be in the 60 to 65 percent range (e.g., Osterman 1994; Godard 1997), with many experiencing response rates substantially lower than this (e.g., Wagar 1997; Ichniowski, Delaney and Lewin 1989).

Second, rather than individual researchers collecting their own data with limited resources, government surveys can in effect be viewed as the equivalent of “pooling,” with much greater resource inputs. These inputs allow surveys to be conducted by telephone or even on a face-to-face basis, as has been the case for the AWIRS and the WIRS/WERS series. This format, again coupled with the official status of these surveys, has in turn allowed for much greater survey length and comprehensiveness, apparently without appreciably harming response rates. In the AWIRS, WIRS/WERS, and WES, employer interviews have typically averaged an hour or more. In contrast, limited resources typically mean that independent surveys are conducted by mail and have to be sharply constrained in length in order to achieve a respectable response rate.

Third, greater resource inputs also enable investigators to survey multiple respondents (e.g., employer representatives and a union representative), as reflected in the AWIRS and WIRS/WERS series. They also make it possible to survey employees as well as employers, thus generating a data set in which employee and employer data can be linked. Though not attempted in the earlier AWIRS and WIRS, this has been done in the most recent AWIRS, the WERS, and the WES, as discussed more fully below.

Fourth, although only partly realized in previous AWIRS and WIRS, government surveys are able to develop standard measures to be used in addressing various research issues, resulting in greater consistency across analyses and possibly in subsequent, independent surveys. This is especially so where investigators are able to conduct pilot surveys and focus groups in order to test the measures and explore how they are interpreted, as has again been the case in the most recent AWIRS, the WERS, and the WES (e.g., see Statistics Canada 1998). In contrast, a major problem with independent surveys has been the tendency for researchers to develop their own, often idiosyncratic measures, making it difficult to compare across studies and ultimately to establish what the literature actually finds (Delaney and Godard 2001; Godard 2000).

Despite these advantages, government administered workplace level surveys can suffer from their own problems. This is evident from the previous AWIRS and WIRS. First, the data in these surveys appear to have been collected largely for descriptive purposes. There seems to have been little attempt to collect measures in a systematic way that would lead to the creation of indices, scales, or typologies that conform to normal psychometric criteria. This is not to say that the data have not leant themselves to any scale creation. But to the extent that they have, it would appear to have largely been by accident.

Second, and related to this problem, these surveys have contained little attempt to probe in depth the answers to most questions. For example, employers may be asked whether there are autonomous or semi-autonomous teams in their workplaces, but not asked about the specific characteristics of these teams. Thus, it is not always clear what the results actually mean.

Third, even though government surveys have involved multiple respondents in each workplace, there has also been a relative lack of duplicate questions across these respondents. Thus, as for independent surveys, it has been difficult to establish whether the perceptions of managers in fact correspond to the experiences of workers and union representatives. Where attempts have been made, the results have not been encouraging (Cully and Marginson 1995: 12-13; Marginson 1998: 378).

Fourth, there have been few clearly specified research questions or hypotheses informing the collection and reporting of the data in these surveys. The data sets may have been useful for addressing specific research questions or hypotheses, but to the extent that this has occurred, it has again seemed to be almost by accident.[2]

The overall result has been twofold. First, there can be little doubt that these surveys have generated interesting descriptive findings (Marginson 1998: 365-68). But these findings often appear to represent a small portion of the data collected. Although there may be sound a priori reasons for including various items, the lack of specific research questions or theoretical focus has meant that large portions of these surveys generate little that is new or of interest. This has left them open to the criticism that, for the most part, they only confirm what researchers already know (McCarthy 1994).

Second, the data sets contain masses of variables that can be used for multivariate analysis, but the resulting research often has had a “seat-of-the pants” air about it, with researchers relying on weak measures and constructing ad hoc indices. The traditional ideal approach to research, where one first creates specific hypotheses, then develops research instruments to yield reliable and valid indicators of relevant variables, and, finally, collects the data with a specific model in mind, is turned on its head. In effect, the data tail wags the research dog. To an extent, this would appear to be the case whenever secondary data sets are employed, but it seems to have been especially serious with respect to prior workplace surveys, where the data often seem to have driven the research questions asked, or at least how they were asked.

This may be more a reflection of the quality of analyses than of the data themselves, and there can again be little doubt that a number of acceptable multivariate analyses have been generated (see Marginson 1998: 369-70). Nonetheless, even those that have been accepted into top IR or management journals have often seemed highly constrained by data limitations (e.g., Drago 1996; McNabb and Whitfield 1997). This may be because the data were not intended for the usage to which they were put but, if so, this reflects a limitation to prior surveys. If the authors are to be faulted, it is more often for the latter reason than for a lack of research skills.

The above limitations may also reflect more fundamental problems that inhere to workplace level surveys in general, but are especially serious for government surveys in view of claims often made as to their comprehensiveness and authoritativeness. In particular, many of the workplace level constructs that these surveys attempt to measure are, in effect, complex social and technical processes and relationships through which individuals and groups act and interact on a day to day basis (Godard 1993, 1994b). These processes and relationships may vary considerably within the workplace and may change on a daily basis. They also entail a subjectively constituted reality, based on inter-subjective rules and understandings that are produced, reproduced, and changed through processes of action and interaction. To attempt to assign single numbers to these processes and relations may be to completely misrepresent them, not just empirically, but ontologically. To obtain such numbers by asking general questions of a single respondent often removed from the processes themselves may be especially misguided (Millward and Hawes 1995: 72).[3]

Four decades ago, C. Wright Mills’ criticism of survey research was that “details [have been] piled up with insufficient attention to form.... no matter how numerous, [they have] not convinced us of anything worth having convictions about” (1959: 55; also cited in Cully et al. 1999: 2). Any fair assessment of the previous AWIRS and WIRS would recognize that this criticism would be overblown if applied to these surveys. These surveys have undoubtedly been useful for “mapping” industrial relations and helping to identify changes therein. Moreover, many of the “details” they have provided have been of value to both academics and policy makers. But the criticism would also not be entirely misplaced. In particular, although prior AWIRS and WIRS may have substantially improved our knowledge of industrial relations, they are open to the criticism that they have been much less useful in enhancing our understanding of these relations, and may even have contributed to a superficiality that some argue has developed within the field (Kelly 1998).

What makes this of particular concern is that the efforts of academic researchers, and possibly the resources available to them, may become diverted, thereby actually detracting from the quality of research and distracting scholars from issues that do not lend themselves to secondary data analysis (McCarthy 1994: 321). The extent to which this has occurred in the U.K. and Australia is at best uncertain (Millward and Hawes 1995: 71) and, as Marginson (1998: 362) has argued, it certainly need not be the case. In the ideal, large scale workplace surveys are complemented by more fine-grained and theoretically informed independent survey and qualitative research. But although there may have been a few exceptions, for the most part this does not seem to happen. The tendency in social science has been towards multivariate analysis and the use of large scale data sets, and IR would not appear to have been immune to it. Possibly as a result, it seems that qualitative analyses in particular are less likely to get published in major journals (Whitfield and Strauss 2000) and less likely to get noticed where they do.

Government surveys can, however, potentially serve as valuable sources of data for both descriptive and broad-based multivariate research. Although some of the above problems may be virtually inherent to large-scale government workplace surveys, the extent to which they are manifest may depend on the specific design of the survey in question and, ultimately, funding and oversight arrangements. The question that arises, then, is how well do the 1995 AWIRS, the 1998 WERS, and the 1999 WES succeed in overcoming these problems and, more generally, in providing high quality data for industrial relations research? This question is especially important if, as suggested above, the conduct of these surveys potentially distorts research and there is, indeed, a trend to the use of large scale secondary data sets.

A tale of three surveys

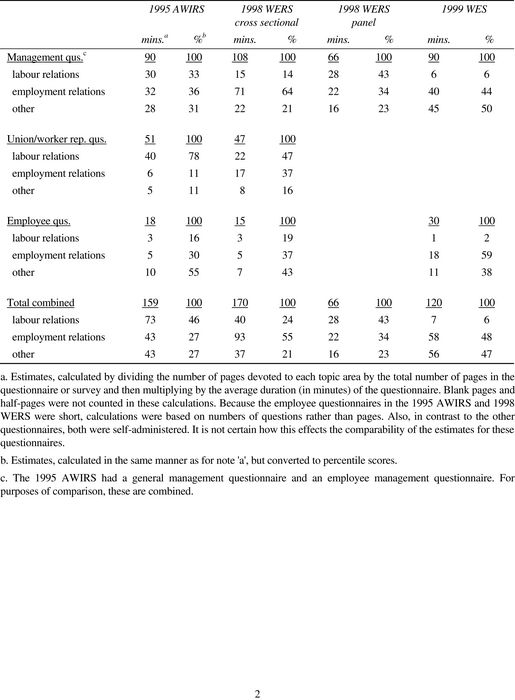

For comparison purposes, the structures of the 1995 AWIRS, the 1998 WERS, and the 1999 WES are summarized in Table 1. Table 2 contains estimated breakdowns of the percentage and minutes of content allotted to labour relations, employee relations, and “other” (albeit often related) topics. In the discussion below, I also provide further breakdowns in accordance with the percentage of space allotted to individual topics within each of these three broad categories.

The 1995 AWIRS

Structure. The main 1995 AWIRS survey had a population of 2001 workplaces, with a size cut-off of 20 employees. It consisted of four questionnaires: (1) a workplace characteristics questionnaire, (2) a general management questionnaire administered to the senior manager, (3) an employment relations management questionnaire administered to the senior manager for employment relations, and (4) a union delegate questionnaire. The latter three involved face-to-face interviews of, on average, 36, 60, and 51 minutes in duration, respectively. The workplace characteristics questionnaire was mailed to the senior manager in the workplace, to be completed in advance of the interviews. In 60 percent of the workplaces, the senior manager and the employment relations manager were the same person, and in half there was no union delegate. Eighty percent of the workplaces in the initial sample participated.

In addition to the main survey were three supplemental surveys: (1) a panel survey administered to employment relations managers in 698 workplaces participating in the 1990 AWIRS, (2) an employee survey, self-completed by 19,155 respondents randomly selected from participating workplaces (with up to, and in some cases over, 100 employees per workplace, depending on size), and (3) a small workplace survey, administered by telephone to 1075 workplaces with from 5 to 19 employees. The panel survey used slightly modified versions of the main survey questionnaires and so had a similar completion time. The employee survey entailed a self-completion questionnaire distributed to randomly selected (from an employer provided list) employees, and took an average of 18 minutes to complete. The small workplace survey was administered face-to-face, and took an average of 51 minutes to complete. The response rate was 90 percent for the panel survey, 64 percent for the employee survey (95 percent of workplaces participating in the main survey agreed to this survey), and 89 percent for the small workplace survey.

Table 1

The AWIRS, WERS, and WES: Survey Designs and Characteristics

Table 2

Estimated Survey Composition

Content. The general management questionnaire, the employee relations management questionnaire, and the union delegate questionnaire were the main questionnaires. They thus provide the best sense of the composition of the 1995 AWIRS. However, for purposes of comparison with the WERS and WES, it is best to consider the two management questionnaires in combination.

Roughly a third of the questions in the general management and employee relations management questionnaires addressed labour relations topics, including collective agreements (16 percent), arbitration awards (3 percent), strikes (2 percent), union organization (7 percent), workplace negotiations (4 percent), and union relations (1.5 percent). Slightly more (about 36 percent) addressed employment relations topics, though a number of these could also involve unions where established. They included the employment relations function (7 percent), employment practices (5 percent), recruitment and training (2 percent), communication and participation (10 percent), health and safety (2 percent), parental leave and family care (2.5 percent), equal employment and affirmative action (3 percent), and payment systems (5 percent). The remaining questions included background information (4 percent), workplace characteristics (5 percent), product markets (3 percent), workplace performance (5 percent), workforce reductions (2 percent) and organizational change (10 percent), the latter of which included questions relevant to both labour and employment relations.

Roughly four fifths of the union delegate questionnaire addressed labour relations topics, including union organization (20 percent), the role of union delegates (17 percent), delegate-union relations (8 percent), union amalgamations and inter-union relations (11 percent), union-management relations (5 percent), workplace negotiations (14 percent), and strikes (5 percent). An additional 11 percent addressed employment relations topics, including equal employment opportunities (3 percent) and communication and participation (8 percent). The remainder addressed organizational change (11 percent).

Although supplemental to the main questionnaires, the employee questionnaire also deserves brief consideration, as it provided valuable data and can serve as a point of comparison with the WERS and WES. This questionnaire contained 45 questions, of which 16 percent addressed labour relations, mostly respondent participation in, and attitudes toward, the union. Roughly 30 percent also addressed employment relations issues, including working arrangements[4] (13 percent), training (2 percent), employee friendly HR policies (7 percent), and health and safety (7 percent). The remainder addressed personal characteristics and qualifications (30 percent), workplace changes (18 percent), and job characteristics and attitudes (7 percent).

In total, these questionnaires contained an estimated 73 minutes of labour relations questions, 43 minutes of employment relations questions, and 43 minutes of “other” questions. These categories accounted for, respectively, 46 percent, 27 percent, and 27 percent of the questionnaires.

Assessment. The 1995 AWIRS yielded a number of interesting descriptive findings, as reported in Changes at Work (Morehead et al. 1997). This is particularly so with respect to comparisons between the 1990 and the 1995 results, which represents the main focus of this book. In labour relations, for example, Changes at Work reports a decline in workplaces with “active” unions from 24 in 1990 to 18 percent in 1995, and a corresponding decline in the proportion of workplaces with delegate negotiations, from 27 to 19 percent. The union density and coverage figures were much higher than this, in reflection of Australia’s unique labour relations institutions. However, union density declined from 71 to 59 percent, and the number of unionized workplaces from 80 to 74 percent. The authors of Changes at Work conclude that “although the development of workplace bargaining has heralded a much changed industrial relations system, awards continue to play a major role in the determination of pay and conditions for many employees” (229).

As for employment relations, the AWIRS data indicates that there has been an increase in the percentage of workplaces with specialist employee relations managers, from 34 to 46 percent. It also reveals an increase in the prevalence of joint consultative committees, (from 14 to 33 percent), formal disciplinary procedures (37 to 92 percent) and training for supervisors (39 to 72 percent). These results reflect an increase in the number of “structured” workplaces, defined as workplaces with at least four of seven elements of employment relations asked about, from 39 to 59 percent.

These findings represent only a small sampling of the descriptive information yielded by the 1995 AWIRS and reported in Changes at Work. Yet overall, the AWIRS appears to be weak in a number of topic areas, particularly those involving employment relations. For example, there was only one question directly addressing team organization, and it simply asked whether “semi or fully-autonomous work groups” were in place in the workplace. Aside from this single item, I was unable to find much addressing the actual processes and organization of work. The items addressing the overall “high performance model” in general also appear to be limited. Finally, even with respect to labour relations, a large portion of the employer data involves highly subjective and often retrospective measures, which may limit the confidence that can be placed in them.

The 1995 AWIRS did contain a number of attitudinal and behavioural measures that can be used in both descriptive and multivariate research. For example, the employee questionnaire included measures of satisfaction with treatment from management, overall job satisfaction, trust, influence over workplace issues, and consultation from the employer. It also contained a number of questions about attitudes towards unions. The management questionnaires contained numerous items about the location of decision making within management, the objectives underlying workplace change programs, and managerial attitudes towards unions.

Despite the presence of these measures, however, the AWIRS does not seem to have been designed to facilitate multivariate research. Many of the “objective” measures needed for such research were weak or lacking altogether. For example, there were no measures of technology, and although a number of questions were included as to market context, most consisted of only one or a few possible responses, yielding qualitative rather than interval variables. Measures of many potential “dependent” variables were also crude. In particular, labour productivity was measured by simply asking for perceptions of how it compared to two years earlier, on a five point scale from “a lot higher” to “a lot lower.” Training was measured simply by whether the workplace had provided a formal training program over the previous year.

Even the attitudinal and behavioural measures were often weak. Some did lend themselves to scale construction (e.g., degree of empowerment, union effectiveness, organizational change), but for the most part they had only two or three response options (e.g., “agree,” “neither agree or disagree,” “disagree”) and often entailed single-item measures, both of which militate against meaningful scale creation for multivariate purposes. Overall, it may be possible for researchers to piece together enough data for acceptable multivariate analysis. But where this is the case, it is likely to be largely by accident.

These limitations are mirrored by the style of Changes at Work. It contains masses of data, including an appendix with over two hundred tables. But there is little theoretical or conceptual content, providing little explanation for why various items were included and making little attempt to ground the findings in the literature, either with respect to the substantive issues raised or the measurement of various constructs. There is also little attempt to explain the findings.

Explaining the AWIRS. It would appear that these limitations are by design. The AWIRS research team consisted of employees in the Industrial Relations Department of the Australian Government, and their mandate appears to have been to collect data of policy relevance to their political masters, particularly with respect to the effects of legislative changes on bargaining and payment structures. Academic involvement in the survey appears to have been limited primarily to a seminar with users of the 1990 AWIRS early in the design process. It also appears that the research team was to only provide a “window on the data,” providing a resource for others, who could then interpret the initial findings and conduct further analysis of the data to address various research issues.[5]

Overall. There can be little doubt that the 1995 AWIRS demonstrates many of the advantages of large scale government surveys. The sample size was large if judged by independent survey standards, the response rates were also high by these standards, and the survey employed a multi-respondent format. In addition, it contained comprehensive coverage of industrial relations topics and, in particular, labour relations. Undoubtedly, it has provided a wealth of relevant information to policy makers and possibly academics concerned with changes that have been occurring in Australian industrial relations. In this regard, Changes at Work represents an excellent source book, and the research team appears to have fulfilled its mandate well.

From a more academic perspective, however, a different conclusion is warranted. The survey would appear to have lacked much conceptual or theoretical underpinning, and does not seem to have been well informed by various issues and debates in the academic literature. The data set would also appear to be of limited quality, particularly for those concerned with multivariate analysis and measurement issues. Perhaps as a result, papers that have drawn on the 1995 AWIRS data to date (e.g., Rimmer 1998; Wooden 1999a, 1999b; Harley 1999) appear to have been largely descriptive, with most multivariate analysis limited and seemingly constrained by data limitations. The 1995 AWIRS may not be guilty of abstracted empiricism, because it would appear that policy related questions drove the survey design. But from an academic standpoint this criticism may not be far off the mark.

The 1998 WERS

Structure. The 1998 WERS had the benefit of hind sight not only from previous WIRS, but also from the 1995 AWIRS, which not only preceded it but whose lead investigator (Alison Morehead) also served in an advisory capacity (Cully 1998). Its overall structure was similar to that of the 1995 AWIRS, including both management and worker representative questionnaires administered on site, an advance workplace characteristics questionnaire sent by mail, and a self completion questionnaire distributed to employees. As revealed in table 1, the sample sizes, completion times, and response rates on these questionnaires were similar, with the exception of the employee sample, which was one-and-a-half times that of the AWIRS sample.

Despite these similarities, the WERS differed in a number of respects. First, there was only one management questionnaire, usually administered to the manager with primary responsibility for employment relations in the workplace. Second, in workplaces where there was no union delegate but some alternative form of representation, the most senior nonunion worker representative was surveyed. Third, the cut-off to be included in the main survey was lower than for AWIRS, at ten rather than twenty employees. Fourth, and partly as a result, there was no separate small workplace survey. By using computer aided personal interviewing (CAPI), it was possible to design the main questionnaire so that only those questions relevant to small workplaces were asked in those workplaces. Finally, the panel survey included only a single questionnaire, to be answered by a management representative.

Content. The emphasis of the WERS differed in important respects from both the AWIRS and previous WIRS. In particular, only about 14 percent of the management questionnaire explicitly focused on labour relations, with union representation issues comprising 8 percent, and collective disputes and procedures 6 percent. In contrast, about two thirds addressed employment relations topics, including the personnel function (8 percent), recruitment and training (7.5 percent), work organization (2 percent), consultation and communication (8 percent), payment systems (15 percent), grievance and disciplinary procedures[6] (6 percent), equal opportunity and related policies (8 percent), working arrangements (6 percent), and redundancies (3 percent). The remainder of this questionnaire addressed management views about union and employment relations in their workplace (2 percent), performance outcomes and market context (8 percent), organizational change (5 percent), and workplace ownership and control (6 percent).

As would be expected, the worker representative questionnaire contained a greater emphasis on labour relations. To assess percentages is difficult, as many of the questions were designed to address nonunion representation in workplaces without a union. Nonetheless, roughly half applied primarily to labour relations, including the structure of representation (17 percent), union recruitment (5 percent), the role of representatives (7 percent), pay determination (9 percent), and collective disputes and procedures (9 percent). An additional 37 percent addressed employment relations, including participation and consultation (17 percent), grievance and disciplinary processes (9 percent), and the relations between worker representatives and management (11 percent). However, these would also fall largely under the topic of labour relations in union workplaces. The remainder of the questionnaire addressed workplace change (9 percent) and personal background (7 percent).

The employee questionnaire contained 32 questions, 19 percent of which addressed labour relations, including the respondent’s relationship to and attitudes toward the union, and two fifths of which addressed employment relations issues, including working arrangements (16 percent), appraisal (3 percent), training (3 percent) employee friendly HR policies (6 percent), and consultation and information sharing (9 percent). The remaining questions addressed personal characteristics and qualifications (31 percent), and job characteristics and attitudes (12 percent).

In total, these questionnaires contained an estimated 40 minutes of labour relations questions, 93 minutes of employment relations questions, and 37 minutes of “other” questions. These categories account for, respectively 24 percent, 55 percent, and 21 percent of the questionnaires.

In contrast to the AWIRS and WES surveys, the 1998 WERS panel questionnaire was designed by a different research team (led by Neil Milward) and had substantially different content, placing much greater emphasis on labour relations. As such, it deserves separate mention. About two fifths of this survey addressed explicit labour relations topics, including union membership, recognition, and representation (15 percent), bargaining and bargaining structure (23 percent), and collective action, procedures, and agreements (5 percent). About a third addressed employment relations topics, including management organization (7 percent), payment systems (15 percent), consultation and communication (8 percent), and employment practices (4 percent). The remainder addressed workforce composition and outcomes (2 percent), economic context and performance (5 percent), and establishment characteristics and management (17 percent).

Assessment. As reported in Britain at Work (Cully et al. 1999), the 1998 WERS generated a variety of interesting, indeed striking, descriptive results. With respect to labour relations 54 percent of managers interviewed stated that they favoured union membership, while only 4 percent stated that they did not (the rest were neutral). Forty-three percent agreed that unions help find ways to improve performance, while only 30 percent disagreed. However, in a quarter of union workplaces there was no reported union representative, in two thirds there was no negotiation with union representatives over pay or conditions of employment, and in half there was no negotiation over any of nine different items asked about (e.g., pay, training, handling of grievances).[7] Moreover, in those workplaces where there were union representatives, almost a third of these representatives reported that they spent less than one hour per week on union activities, and a half reported that they spent less than two hours. Finally, half of employee respondents who were union members did not consider unions to be taken seriously by management. As expected, these findings were more prevalent for small workplaces.

The descriptive findings are equally noteworthy for employment relations. For example, of 15 advanced HRM practices included in the management questionnaire, only 14 percent of respondents reported 8 or more. In addition, although 65 percent reported some team working among their core workforce, only 3 percent indicated that they had teams meeting all four of the criteria identified by the researchers as characteristic of fully autonomous teamwork. Moreover, while a third of the workplaces in the study met criteria considered to be characteristic of semi-autonomous team working, these conditions were more likely to be met in workplaces where the main occupational group was professional (53 percent) or associate professional and technical (46 percent). They were least likely to met where the main group was craft and related workers (21 percent) or plant and machine operatives (17 percent), even though these workplaces are the ones with which new forms of work organization seem to have been most associated by proponents.

In contrast to its Australian counterpart, Britain at Work contains only a single chapter examining changes. This chapter was written by separate authors (Neil Millward, Alex Bryson, and John Forth). It is based on comparisons with the general findings of the 1980, 1984, and 1990 WIRS surveys and relies extensively on the panel questionnaire from this and previous surveys. The analysis in it is more fully developed in a subsequent book by these authors, All Change at Work? It is beyond the scope of this paper to attempt to review the latter, except to note that both it and the chapter in Britain at Work demonstrate the value of the panel data for placing the 1998 findings in context and identifying significant changes over time. For example, it appears that there has been some increase in the prevalence of personnel specialists (as Changes at Work also finds), and a continued decline in union membership, union recognition, union influence where recognized, and collective bargaining where recognized. Consistent with the 1990 WIRS, the authors also find that the decline in union density and recognition does not reflect changes in industrial composition (from manufacturing to services) or decisions by employers to derecognize unions, but rather a growth in the number of new workplaces that do not recognize unions.

In addition to the valuable descriptive findings reported in Britain at Work, the WERS data set promises to be of considerable use for multivariate research.[8] For example, the employee questionnaire contained multiple items for commitment, job satisfaction, work intensity, fairness perceptions, job autonomy, and other subjective variables. The number of items for each variable tended to be low (usually three), but many were drawn from the established literature and for-the-most-part yielded reasonably reliable scales (as reported in endnotes to Britain at Work). The management questionnaire also contained multiple items for a number of constructs. The most evident of these, just referred to, was the inclusion of 15 different items addressing the extent to which the high commitment model appears to be in place. But a further example includes the use of multiple items addressing the extent of negotiation, consultation, and information sharing with both union and nonunion representatives. These should allow for useful scales measuring the level of worker representation (union and nonunion) at the workplace level.

The WERS data set does have important limitations. For example, the economic performance measures are subjective, based on managerial perceptions of workplace performance relative to that of competitors. There are also very few measures of workplace context variables (e.g., technology, market conditions) needed to explore for variation in workplace processes and outcomes. Both of these limitations also represent limitations to the AWIRS, and, as for the AWIRS, may significantly impair the data set’s value for multivariate analysis. For example, Ramsay et al. (2000) were unable to find evidence that the apparent performance effects of high performance practices operate through their implications for worker attitudes and dispositions. Yet this finding may be readily dismissed (by those who wish to do so) as reflecting poor performance measures and/or context controls. (It may also indicate limitations inherent to this kind of research, as discussed earlier.)

In addition, although there is some measurement duplication across different questionnaires (e.g., the same job influence items in both the management and employee questionnaires, the same IR climate item in all three questionnaires), this duplication tends to be quite limited, again making it difficult to establish just how valid managerial responses are.[9] But despite these limitations, the WERS lends itself to multivariate analyses of higher quality than has been the norm in the past.

The high quality of the 1998 WERS is reflected in the quality of Britain at Work. Instead of simply reporting results, it couches these results in terms of specific issues and, perhaps as a result, reads more like an academic analysis. It does not contain comprehensive literature reviews or theory sections, but each section opens with a brief discussion of issues raised in the literature, thus grounding the ensuing analysis and orienting the reader. To illustrate, although Changes at Work provides some information as to the use of temporary and part-time workers, it does not situate this information within the precarious employment literature. Nor does it address the broader issues in the flexible workplace debate. Britain at Work does both, explicitly addressing questions about the extent of, nature of, and associations between various forms of “numerical” flexibility (e.g., use of part-time workers) and their relationship to “functional” flexibility (e.g., multi-tasking). Britain at Work also provides much more in-depth analysis of work organization, again couching the analysis within broader debates and exploring the extent to which employers appear to have adopted new forms of work organization.

Explaining the WERS. There are a number of possible explanations for the higher academic quality of the WERS book and data set. Perhaps most important, however, is a strong academic involvement in the design of the research. There was substantial input from the academic community. In 1995, the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC), one of the funders, sponsored a consultation exercise with the academic community, giving rise to a report by two prominent academics (Edwards and Marginson 1996). Also in 1995, Mark Cully and Paul Marginson published a critical assessment of past WIRS, mapping out an agenda with substantial suggested changes—changes that came to be incorporated into the design of the 1998 WERS. Leading academics were also contracted with to provide a battery of items relevant to their particular areas of expertise, and during the final three months of the design process, an academic (this author)[10] was brought into the project on a full-time basis. Not only did he act as a consultant to the team, he also visited a number of universities in an attempt to obtain feedback from potential users of the data as to draft versions of the questionnaires.

The greater academic orientation and involvement may in turn reflect the composition of the research team and the oversight structure. Of the research team, the two lead members, Mark Cully and Stephen Woodland (both of whom also had extensive experience with the previous AWIRS and WIRS surveys) were hired out of Ph.D. programs in industrial relations. Though they worked out of the Industrial Relations Directorate of the British Government, there were four sponsors of the survey (the IR Directorate, the Advisory, Conciliation, and Arbitration Service (ACAS), the ESRC, and the Policy Studies Institute (PSI)[11]), so the research team reported to a steering committee consisting of representatives from these sponsors rather than to government officials. Only two of the steering committee members were employees of the Industrial Relations Directorate, and one of these was the chair and as such viewed her role as ensuring that a balance was achieved between the priorities of the four sponsors rather than representing government policy concerns.[12] It also appears that the ESRC was able to obtain substantial leverage early on, perhaps in part because its 1995 consultation exercise and the ensuing report, along with the Cully and Marginson paper, positioned it to have greater influence than otherwise in the selection of the team and process by which the survey was designed.

Overall. The 1998 WERS appears to demonstrate that the limitations to government surveys can in considerable measure be overcome, and that extensive involvement of academics and ultimately the funding and control structures of these surveys may be important. It remains true that even the WERS data are often crude indicators and cannot substitute for more qualitative and interpretative research. But these forms of research are complementary, and even (or especially) if the trend is in the direction of multivariate analysis of secondary data, the WERS data at minimum ensure higher quality analysis of industrial relations topics than would otherwise be the case, with important implications for the field.

The WES: Uniquely Canadian[13]

Because the results from the 1999 WES were just beginning to be released when this article went to press, it is not possible to provide a full comparison of this survey with the AWIRS and the WERS. However, it is possible to consider its structure and content, and in so doing attempt to establish its likely implications for industrial relations as a field in Canada.

Structure. As for the AWIRS and WERS, the 1999 WES included both management and employee questionnaires, along with a brief, self-completion workplace characteristics questionnaire to be completed in advance. As for the WERS, there was no separate small workplace questionnaire. But in contrast to both the WERS and AWIRS, there was also no union or employee delegate questionnaire. In addition, although the 1999 management questionnaire was about the same length as in the other two surveys,[14] the employee questionnaire had a completion time of 30 minutes, twice as long as for both the AWIRS and the WERS. This questionnaire was also administered by telephone rather than in self completion format and was restricted to a maximum of 12 employees per workplace, compared to 100 for the AWIRS and 25 for the WERS. However, due to the larger number of workplaces covered, the number of employee responses is comparable to that of these two surveys, at just under 25,000 employees. Of note, the response rates were higher than for the AWIRS and WERS, at 94 percent for the management questionnaire and 83 percent for the employee questionnaire.[15]

In addition, although the present analysis focuses on the 1999 WES, this survey was explicitly designed as the first stage of a longitudinal survey, in which data are to be collected on a yearly basis. In contrast, both the AWIRS and the WERS were intended largely as cross-sectional surveys, with their panel components intended primarily for tracking changes from one survey to the next rather than for conducting longitudinal data analysis.

Moreover, there was no workplace size cut-off. All workplaces in which there was at least one employee were included in the sampling frame. This is contrary to the AWIRS, which had a cut-off of 5 employees for its small workplace questionnaire and 20 for its main large questionnaire, and the WERS, which had a cut-off of 10 employees. The workplace sample size was also more than double that of the AWIRS and the WERS surveys, with 6,350 workplaces participating in the first year.

Content. Perhaps the greatest difference is in the actual composition of the survey. Only about 6 percent of the WES management questionnaire addressed labour relations, and this coverage was superficial (see below). About two fifths of its main large workplace questionnaire addressed employment relations topics, but this was skewed towards labour market issues, including hiring and vacancies (16 percent), compensation, especially benefits (17 percent), and training (6 percent). The section on work organization and related HR practices accounted for only 5 percent of the questionnaire. Half of the questionnaire addressed other topics, including organizational change (11 percent), workplace performance (6 percent), business strategy (8 percent), innovation and technology use (19 percent), and use of government programs (6 percent). These latter topics are of course of some relevance to labour and employment relations. But overall the space devoted to them conveys a greater focus than either the AWIRS or the WERS on economic issues related to labour markets and performance.

The employee questionnaire also reflects this emphasis. Labour relations questions accounted for only 2 percent. Employment relations issues accounted for close to three fifths, but again were skewed in content. A third of this content (a fifth of the questionnaire) was comprised of detailed questions on working arrangements (e.g., hours, status), with another quarter on training and development. Only 4 percent of the questionnaire addressed employee participation and work organization. Other employment relations issues covered included promotion and appraisal (4 percent), compensation (9 percent), employee assistance and support services (4 percent), and equal opportunity issues (4 percent). The remainder of the questionnaire addressed attitudes (1 percent), personal characteristics and work history (22 percent), and the use of technology (15 percent).

In total, the 1999 WES contained an estimated 7 minutes of labour relations questions, 58 minutes of employment relations questions, and 56 minutes of “other” questions. These categories accounted for, respectively 6 percent, 48 percent, and 47 percent of the survey.

Assessment. The limited labour relations content in the two questionnaires, coupled with the lack of a union representative questionnaire, means that the 1999 WES contains almost no institutional data. Indeed, there were no questions in the management questionnaire addressing management policies towards unions or the role of union representatives, and four of the five questions on labour relations in the employee questionnaire addressed the workplace “dispute, complaint, or grievance system,” thereby applying to nonunion as well as union workplaces. Employees were otherwise asked nothing about the role of unions or their attitudes and experiences towards them.

There may be more of interest with respect to employment relations, particularly with respect to working arrangements, compensation, and training. But the questions having to do with the nature and organization of work were weak. The human resource practices and work organization section in the management questionnaire simply asked, first, if each of six different practices was in place and if it was, when it was implemented, and then, about the location of decision making for each of 12 activities (e.g., customer relations, training, product development). There was only one question about the actual organization of work, simply asking if there were self-directed work groups. Contrary to the WERS, there was no attempt to obtain data on the extent to which these groups had been adopted or the percent of the workforce covered. In the employee questionnaire, respondents were simply asked how frequently they worked as “part of a self-directed work group that has a high level of responsibility for a particular product or service” and in which “part of [their] pay is normally related to group performance.” Not only is this a substantially different definition than provided in the management questionnaire, it again does not address the extent to which groups are autonomous.

With respect to multivariate analysis, the WES may be of considerable value for addressing various union effects (e.g., on technology, on training, etc.). The data set also contains more objective economic performance and context measures than do either the AWIRS or WERS. But the limited industrial relations content and weak industrial relations measures mean that it will be of only limited value for addressing issues pertaining to the role of unions or new forms of work and human resource practices. The questionnaires also contained very little by way of social-psychological measures. In particular, there would, despite its length, appear to have been only two such measures in the employee questionnaire, one on job satisfaction and another on satisfaction with pay and benefits. Thus, the WES data will provide virtually no opportunity for addressing issues having to do with worker attitudes and work experiences—an area that has been much neglected in the literature (Godard and Delaney 2000).

It would appear, therefore, that the 1999 WES cannot be thought of as an industrial relations survey, at least as defined in this paper. In contrast to both the 1995 AWIRS and the 1998 WERS, it is instead basically a labour market and productivity survey. In addition, while the 1999 WERS appears to have some conceptual underpinning, this would appear to be of negative effect from an IR standpoint. The survey seems to have been driven by the essentially managerialist policy paradigm that has become predominant both within the federal government (especially HRDC) and increasingly in applied economics or “policy studies.”[16] This paradigm parallels the managerialist approach characterizing much of the work on high performance work systems (see Godard and Delaney 2000), though it is premised more on the belief that training, innovation, technology, and business strategy represent the keys to both economic performance and good jobs. It is generally assumed that good jobs are consistent with good economic performance, and that the absence of such jobs largely represents a “market failure.” The role of the government, therefore, is to provide information and assistance that remedies this failure, addressing workplace problems primarily to the extent that doing so is not contrary to employer interests. Unions and collective bargaining tend to be viewed as largely irrelevant, at least under the Canadian variant of this paradigm.[17]

On the bright side, the WES data set may provide a basis for testing a number of the assumptions and hypotheses associated with this paradigm (see Delaney and Godard 2001). It is also likely that the WES will yield a considerable body of high quality descriptive and multivariate work of relevance to economic policy. In this regard, economists will find it of particular value, especially in view of the superior measures of context and performance variables. The longitudinal design should also facilitate analysis of ongoing developments and help to address problems of causality and method bias that have plagued the AWIRS and the WIRS/WERS series. Moreover, rather than issuing an AWIRS or a WERS-style overview book, the plan is to release the findings through targeted reports and research papers, some of which will be completed by Statistics Canada employees, others of which will be contracted out to selected outsiders. This should help to ensure that the results are highly focused and lay to rest any possible charges of abstracted empiricism. But overall, the high quality of this survey is more than offset by its weak industrial relations content.

Access to the WES data is also a cause for concern. At the time this article was written (fall, 2000), the intention was to allow researchers to work with the data at one of six “Research Data Centres” across the country, subject to strict confidentiality agreements. But just as it was going to press, it became apparent that this had been changed. As of this time, independent researchers will have no direct access to the data. Statistics Canada will instead provide a “dummy” data set with which researchers can establish how they would analyse the data if they could. Researchers can then ask Statistics Canada to run the data accordingly, on their behalf. This means that in depth analysis will be difficult at best. The explanation is that Statistics Canada is concerned about confidentiality. But this does not seem to have presented any problem for either the 1995 AWIRS or the 1998 WERS. In view of the very considerable resources that appear to have been devoted to the WES, and what the government’s decision seems to imply for the independent conduct of research, this is not just disappointing, it is disturbing.

Explaining the WES. As for the AWIRS and WERS, the process by which WES was designed and administered may provide the key explanation for its structure and content. Though there was academic membership on an advisory committee set up for the design of the 1999 WES, the key actors driving this design appear to have been senior public officials. The survey is presently funded for four years under the federal government’s “Data Gaps” program, which is administered by a committee (the Policy Research Initiatives Committee) consisting of assistant deputy ministers from a number of government departments. Thus, to gain funding approval, the survey had to be designed so as to address specific policy questions, and to establish that there were gaps in the data needed to address these questions. To this end, full funding was not received until after Statistics Canada had completed a pilot survey of 748 workplaces in order to establish this (HRDC/Statistics Canada 1998). This is contrary to both the AWIRS and the WERS, where funding approval occurred prior to the design process.

Overall. The WES is likely to provide more focused and possibly higher quality data than either the AWIRS or the WERS. As a result, it could represent a “new dawn” for researchers interested in various labour market and economic policy issues, providing a rich body of data of a quality unmatched by other data sets. But it may represent a “bad moon rising” for mainstream Canadian IR research and possibly for the field of IR in general. Not only does the potential contribution of the 1999 WES to addressing the issues and topics defining the field appear to be limited, it may prove to be harmful to the field, especially if it distorts resources and attention away from these issues and topics and encourages a paradigm at odds with the field’s more collectivist and conflict-oriented tradition. It may as a result diminish both the quantity and status of industrial relations research. It may also perpetuate the disturbing tendency of IR research to increasingly focus more on economic issues at the expense of worker outcomes, and to adopt a management centred approach at the expense of a more worker centred one (Godard and Delaney 2000). The lack of attention to the role and effectiveness of unions is especially worrisome, because it suggests their marginalization not just as a topic for research, but also possibly in the minds of policy makers.

Of course, these implications are in part contingent on access to the data set. If this access is not improved, then there is reason to worry that the WES potentially represents a bad moon rising not just for IR researchers, but ultimately for Canadians in general, reinforcing what some have viewed as a gradual erosion of the role of independent academic inquiry, in this case in favour of state controlled research. In view of Statistics Canada’s reputation for high quality, arms-length analysis, this broader concern may be unfounded. But it should not be dismissed out of hand.

Conclusions

Returning to the questions posed at the beginning of this article, it would appear, first that large-scale, government surveys can be effective in providing workplace level data of reasonably high quality for assessing the extent and nature of change and various policy issues associated with it. This is especially apparent from the 1998 WERS, which successfully addresses many of the limitations of earlier government surveys. It is less apparent, however, from the AWIRS and the WES, the former of which borders on abstracted empiricism, the latter of which contains limited industrial relations content, particularly regarding unions and collective bargaining.

Second, it would appear that these surveys can also provide high quality data for multivariate research. Perhaps paradoxically, this is best demonstrated by the WES. Even though the WES data may be of only limited use to IR scholars, it is highly focused and contains “hard” measures of both workplace context and performance outcomes. It would also appear, however, that the WERS, which focuses on IR topics, contains data that are of at least reasonable quality and of extensive value for IR research.

Third, it seems clear that government surveys have a number of advantages over their independently conducted counterparts and that a number of the limitations associated with them can be overcome, especially if they are designed with extensive academic input. This would seem to be the main reason why, at least for IR academics, the WERS data set is superior in quality to the other surveys considered in this paper.

Fourth, despite the advantages associated with them, the implications of government surveys for the overall quality of IR research are still not clear. Previous AWIRS and WIRS may have resulted in diminished quality, especially with respect to multivariate analysis. The opposite may be true with the respect to the 1998 WERS, although this is unlikely to be so with respect to the 1995 AWIRS or the WES. With respect to the WES, it may even have negative implications for IR research if it results in a distortion of resources and marginalization of the issues that have traditionally been central to the field.

Finally, it is clear that these surveys can be further improved, at least from an IR perspective. Doing so would entail using the WES design but including academics more fully in content decisions and ensuring that the IR content is broader and more comprehensive. Indeed, the WES might be substantially improved by simply adopting a number of questions from the 1998 WERS. This would also allow for cross-national comparisons, which at present are difficult due to a lack of correspondence across these surveys. Whether we can expect to see such improvements is another matter in view of the funding and control structure of the WES. Much may depend on the ability of IR scholars, and members of the IR community in general (e.g., the labour movement), either to have this structure altered and expand the policy paradigm underlying the WES, or to lobby for a separate survey.[18] Doing so could have important implications not only for the future of the field, but possibly also for the policy issues and institutions on which it focuses.

Parties annexes

Remerciements

I thank Mark Cully, Zmira Hornstein, Paul Marginson, Alison Morehead, Howard Krebs, Ted Wannell, Gregor Murray, and three anonymous reviewers for their comments on an earlier version.

Notes

-

[1]

Alison Morehead, the lead AWIRS researcher, has indicated in a personal communication that the 1995 AWIRS team had a specific brief to focus on enterprise bargaining and that their first task after collecting the data was to write a report to government addressing this issue. Only after this report was completed did the researchers begin on the book addressed in this paper, Changes at Work.

-

[2]

A possible exception is the concluding chapter of the 1990 AWIRS book (Callus et al. 1991), in which the authors developed a three way classification scheme based on distinctions developed in the IR literature and used this as a basis for both summarizing results and exploring variation in a number of outcomes. But even this classification was used largely for descriptive purposes.

-

[3]

This would seem to be the concern underlying McCarthy’s criticisms of the WIRS (1994), criticisms that have been dismissed by proponents of large scale workplace surveys (e.g., Millward and Hawes 1995; Cully and Marginson 1995: 2). However, although there may have been a number of mistakes in his analysis, the underlying problem that appears to have motivated it has not been well addressed by proponents.

-

[4]

I use this term to refer to various questions associated with “flexible” or “contingent” employment arrangements, such as hours worked, employment status, homework, and related issues.

-

[5]

E-mail communication from Alison Morehead, Dec. 15, 2000.

-

[6]

In Britain, 91 percent of employers have grievance procedures. Thus, these procedures are in place regardless of union representation and cannot be classified under the topic of labour relations as defined for present purposes.

-

[7]

It is possible that the latter findings reflect in part a tendency for negotiations to take place at higher levels in multi-workplace employers. But even for unionized workplaces reported as unconstrained by the policies of a parent organization, a quarter had no negotiation over pay and conditions.

-

[8]

The value of the WERS data set for IR research is demonstrated in the December 2000 issue of the British Journal of Industrial Relations (BJIR), which contains six papers with both descriptive and multivariate analysis of the data. The topics covered include the effects of high performance work systems (by Ramsay et al.), variation in discipline and dismissal cases (by Knight and Latrielle), the effects of employee participation and equal opportunity programs (by Perotin and Robinson), the determinants of low pay (by McNabb and Whitfield), variation in employments contracts (by Brown et al.), and union decline (by Machin).

-

[9]

The one question that was asked of all respondents in each workplace, and for which the responses are compared, addresses industrial relations climate. It bore only weak associations across respondents. Because we would expect differences in these perceptions, not too much should be made of this. Yet it is noteworthy that these perceptions also tended to correlate to a number of other subjective questions asked of respondents in each group, raising the specter of common method bias.

-

[10]

Because I was involved in the project, I may have some sense of ownership over the results, thereby biasing my assessment. However, I had limited influence over the design of the instruments, and played no role in the writing of either Britain at Work or All Change at Work?

-

[11]

Though ACAS and the ESRC receive government funding, they are quasi-independent organizations.

-

[12]

Personal communication with the chair, Zmira Hornstein.

-

[13]

I thank Howard Krebs of Statistics Canada (Labour Division) for his assistance with this section.

-

[14]

Although the 1999 employer questionnaire involved a face-to-face interview, I am told that in future waves it will be a mail survey only.

-

[15]

The former probably reflects the decision not to contract out the administration of the survey, thus enhancing its official status and legitimacy. Statistics Canada’s reputation for quality and confidentiality in all likelihood played an important role in this respect. The latter is possibly in part for similar reasons, but also because of the decision to use a telephone interviewing format.

-

[16]

This is nicely represented in Michael Porter’s 1991 report, jointly paid for by the Business Council on National Issues and the Mulroney government, entitled Canada at a Crossroads: The Reality of a New Competitive Environment (see Godard 1994a: 430, 438). Although somewhat circumspect, a paper on the WES written by Statistics Canada employees (Krebs et al. 1999) suggests that this paradigm indeed played a major role in the design.

-

[17]

This is illustrated by a HRDC/Statistics Canada discussion paper (1999) advancing a research agenda for the WES data. It identifies 29 research themes clustered within 9 topic areas. Although topic areas include family friendly policies, earnings inequities, and nonstandard work arrangements, not a single theme addresses unions and collective bargaining, and the only theme addressing work practices is concerned with the implications of these practices for innovation. In contrast, industrial relations remains a major policy concern in Europe. For example, it represents one of the three core research areas of the European Foundation for Improvement of Living and Working Conditions, an agency of the EU.

-

[18]

To an extent, his may already be happening, through the work of the Canadian Policy Research Network.

References

- Callus, R., A. Morehead, M. Cully, and J. Buchanan. 1991. Industrial Relations at Work: The Australian Workplace Industrial Relations Survey. Canberra: ACPS.

- Cully, Mark. 1998. “Guvnors, Employees, and Brothers: Triangulation and Noise in Workplace Surveys.” Paper presented to the U.S. Bureau of Census International Symposium on Linked Employer-Employee Data, Arlington, Virginia, May 21–22.

- Cully, Mark, and Paul Marginson. 1995. “The Workplace Industrial Relations Surveys: Donovan and the Burden of Continuity.” Warwick Papers in Industrial Relations, No. 55. Warwick, U.K.: Industrial Relations Unit, Warwick University.

- Cully, Mark, Stephen Woodland, Andrew O’Reilly, and Gill Dix. 1999. Britain at Work. London: Routledge.

- Delaney, John, and John Godard. 2001 (forthcoming). “An IR Perspective on the High Performance Paradigm.” Human Resource Management Review.

- Drago, Robert. 1996. “Workplace Transformation and the Disposable Workplace: Employee Involvement in Australia.” Industrial Relations, Vol. 35, No. 4, 526–543.

- Edwards, Paul, and Paul Marginson. 1996. “Development of the Workplace Industrial Relations Surveys: Results of Consultation Exercise among the Academic and Research Community.” Unpublished paper, The Industrial Relations Research Unit, University of Warwick.

- Freeman, Richard. 2000. “Single Peaked vs. Diversified Capitalism: The Relations Between Economic Institutions and Outcomes.” Working Paper No. 7556. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Godard, John. 1993. “Theory and Method in Industrial Relations: Modernist and Postmodernist Alternatives.” Industrial Relations Theory: Its Nature, Scope, and Pedagogy. R. Adams and N. Meltz, eds. Metuchen, NJ: Scarecrow Press.

- Godard, John. 1994a. Industrial Relations, The Economy, and Society. 1st edition. Toronto: McGraw Hill Ryerson.