Résumés

Summary

The present study examines the income growth of newly arrived immigrants in Canada using growth curve modeling of longitudinal data. The results from this study indicate that recent immigrants, regardless of visible minority status, face initial earnings disadvantage. However, while immigrants of European origins experience a period of “catch up” early in their Canadian careers, which allows them to overcome this earnings disadvantage, visible minority immigrants do not enjoy such a catch-up. This racial difference in recent immigrants’ income growth is found to be caused by the fact that visible minority immigrants receive lower returns to education, work experience and unionization. Furthermore, visible minority recent immigrants face greater penalties for speaking a non-official first language than do their white counterparts.

Keywords:

- immigration,

- visible minority,

- wages,

- labour market,

- SLID

Résumé

La croissance du revenu chez les nouveaux immigrants au Canada : ce que l’Enquête sur la dynamique du travail et du revenu révèle

Au cours de la dernière décennie, des études ont démontré que les immigrants entrés au Canada après les années 1970 ont fait face à des inconvénients plus grands sur le marché du travail que les cohortes antérieures (Bloom et Gunderson, 1991; Baker et Benjamin, 1994; Bloom, Grenier et Gunderson, 1995). Deux facteurs importants contribuent au succès des nouveaux immigrants sur le marché du travail. Le premier est leur niveau de rémunération au début de leur carrière au Canada et le deuxième est leur habileté à rattraper avec le temps les salaires de leurs homonymes nés au pays. Puisqu’on sait que les nouveaux immigrants débutent leur carrière au Canada à un salaire plus bas que leurs homonymes nés au pays, la croissance de leur rémunération plus élevée que la moyenne au cours des premières années de leur séjour semble cruciale pour eux s’ils veulent atteindre la parité avec les Canadiens nés ici.

Les immigrants récemment arrivés peuvent s’attendre à une croissance de leur rémunération plus élevée que celle de leurs homonymes nés au pays pour plusieurs raisons. Premièrement, les nouveaux immigrants investissent dans leur capital humain par le biais d’une formation institutionnelle, un apprentissage de la langue, la constitution d’un réseau social, etc. En ce faisant, ils améliorent leur connaissance et leur compréhension du marché du travail local (Borjas, 1994; Chiswick et Miller, 1994; Duleep et Regets, 1999; Friedberg, 2000; Bratsberg et Ragan, 2002). Deuxièmement, plusieurs nouveaux immigrants peuvent se retrouver sans emploi au cours de leur première année au Canada (Chiswick et Miller, 2007). Au fur et à mesure que les nouveaux immigrants acquièrent une expérience particulière au Canada et que les employeurs reconnaissent leurs habiletés et leurs aptitudes, ils vont possiblement obtenir des emplois qui conviennent à leurs capacités; ils vont aussi connaître une croissance rapide de leur rémunération. Quoique les nouveaux immigrants puissent s’attendre à une augmentation de leur revenu plus élevée que la majorité de ceux qui sont nés ici, le statut de minorité visible peut en retour entraîner une diminution de la croissance du revenu chez eux. Presque toutes les études faites sur les gains des immigrants au Canada ont démontré que les immigrants, qui ne sont pas d’origine européenne, doivent faire face à des inconvénients plus grands sur le marché du travail que ceux qui le sont. Cela peut être attribuable à leur formation ou à leur expérience qui serait de moindre qualité, ou bien à des difficultés plus grandes au plan de l’usage de langue officielle, ou encore au comportement discriminatoire des employeurs.

Jusqu’à maintenant, la plupart des études sur la progression des gains chez les immigrants étaient basées sur des données provenant d’un croisement de profils. Dans ces études, la progression des gains futurs des nouveaux immigrants est évaluée en partant des profils de gains de cohortes antérieures d’immigrants. C’est une méthodologie qui a fait l’objet de critiques puisque ces profils ou tendances peuvent bien ne pas refléter dans l’avenir la progression des gains attendue chez les nouveaux immigrants (Borjas, 1985). Un autre inconvénient inhérent à l’emploi de profils croisés de données réside dans le fait qu’on ne peut pas apporter des corrections pour tenir compte de l’hétérogénéité individuelle inobservée, cette dernière pouvant générer des résultats biaisés (Hum et Simpson, 2000). À cette fin, la présente étude retient l’enquête longitudinale de Statistique Canada sur la dynamique du travail et du revenu (EDTR) (1999-2004), afin de vérifier si les nouveaux immigrants connaissent ou non une période de croissance accélérée de leurs gains ou s’ils effectuent un rattrapage dès le début de leur emploi au Canada. Cette étude veut aussi vérifier si le statut de minorité visible exerce une influence sur la croissance des gains des nouveaux immigrants. Enfin, elle veut également identifier les facteurs qui affectent la progression des gains chez les nouveaux immigrants.

La variable résultante soumise à l’analyse est bien celle du revenu d’emploi. La variable principale explicative reflète le statut d’immigrant et de minorité visible. Puisque les immigrants récents (ceux qui sont au Canada depuis dix ans ou moins) font l’objet de cette étude, ce groupe est plus particulièrement analysé. Étant donné le caractère longitudinal des données, des calculs de régression selon la méthode habituelle des moindres carrés (OLS) n’est pas approprié ici. Par conséquent, les analyses effectuées ici utilisent une modélisation de la courbe de croissance. C’est une variante du modèle linéaire hiérarchique ou à niveau multiple, qui reconnaît et tient compte de la nature dissimulée des données longitudinales (Raudenbush et Bryk, 2002).

Les conclusions tirées de cette étude montrent qu’après avoir maintenu constants d’autres facteurs influençant la détermination des salaires, à la fois les immigrants récents de race blanche et ceux venant d’une minorité visible rencontrent des inconvénients majeurs au plan de leurs gains initiaux au cours de la première année de l’étude. Cependant, les immigrants récents de race blanche réussissent à surmonter un désavantage initial par le moyen d’une croissance accélérée de leur revenu. De fait, ces personnes connaissent une croissance de leur revenu annuel d’un pourcentage de 4,1 % plus élevé que des Canadiens nés au pays de race blanche. Les immigrants issus d’une minorité visible ne connaissent pas pour autant une croissance accélérée de leur revenu si on les considère au regard de leur groupe de référence. À la fin de la période de l’enquête, les immigrants récents de race blanche ont presque rattrapé le niveau de gains de leurs homonymes nés au pays, mais le décalage des gains demeure inchangé chez les immigrants récents issus d’une minorité visible.

De plus, pour apprécier l’influence des facteurs qui contribuent à un désavantage que rencontrent les immigrants récents, des modèles de croissance de revenu sont opérationnalisés de manière séparée : les immigrants récents venant d’une minorité visible, les immigrants récents de race blanche et pour des Canadiens nés au pays. Cette opération permet de conclure que, lorsque les années d’expérience exercent une influence semblable sur le revenu de tous les groupes, les immigrants récents issus d’une minorité visible sont rémunérés moins pour chaque année de leur expérience de travail que les deux groupes de race blanche. Une scolarité de niveau post-secondaire n’est pas appréciée à son mérite dans le cas des immigrants récents, plus particulièrement chez les immigrants récents issus d’une minorité visible. La syndicalisation apparaît comme un autre facteur qui semble affecter d’une manière différente les immigrants récents de race blanche et ceux issus d’une minorité visible. Alors que des immigrants récents issus d’une minorité visible retirent moins d’avantages de la syndicalisation que les Canadiens nés au pays de race blanche, les immigrants récents de race blanche semblent en retirer plus. Enfin, le fait de parler une première langue ayant un statut non officiel (autre que l’anglais et le français) a un impact différent pour chaque groupe. Lorsqu’une première langue non officielle apporte une légère amélioration du revenu annuel des Canadiens de race blanche nés au pays, elle a des effets néfastes sur le revenu des immigrants récents. Une première langue non officielle entraîne spécialement des inconvénients pour les immigrants issus d’une minorité visible.

Plusieurs études récentes ont analysé des profils croisés de données afin de vérifier les salaires d’entrée des immigrants et d’apprécier leur capacité à atteindre la parité avec des travailleurs comparables nés au pays. Cependant, très peu d’études ont retenu des données longitudinales et des instruments qui permettent de comparer directement la croissance des revenus des immigrants récents à ceux des travailleurs nés au pays sur une période de temps. À titre de premier essai, cette étude vient démontrer que les immigrants récents, plus particulièrement ceux issus de minorités visibles, doivent en effet faire face à des obstacles majeurs dans leur combat pour s’intégrer et réussir.

Mots-clés:

- immigration,

- minorité visible,

- salaires,

- marché du travail,

- EDTR

Resumen

Crecimiento del ingreso de los nuevos inmigrantes en Canadá: evidencia a partir de la Encuesta sobre la dinámica de la fuerza laboral y el ingreso

El presente estudio examina el incremento del ingreso de los inmigrantes recientemente llegados a Canadá y utiliza para ello una modelización de la curva de incremento a partir de datos longitudinales. Los resultados de este estudio indican que los inmigrantes recientes, sin tener en cuenta su estatuto de minoría visible, enfrentan una desventaja inicial de remuneración. Sin embargo, los inmigrantes de origen europeo experimentan un periodo de “nivelación” más temprano en sus carreras canadienses, lo cual les permite superar esta desventaja remunerativa, mientras que los inmigrantes identificados como minoría visible no disfrutan de tal “nivelación”. Esta diferencia racial en los ingresos de los inmigrantes recientes es explicada de manera confirmatoria por el hecho que los inmigrantes de minorías visibles reciben una compensación más baja a la educación, la experiencia de trabajo y la sindicalización. Es más, los inmigrantes recientes identificados como minoría visible enfrentan más grandes penalidades del hecho que su primer idioma no sea el idioma oficial como es el caso de la contraparte de raza blanca.

Palabras claves:

- inmigración,

- minoría visible,

- salarios,

- mercado de trabajo,

- SLID

Corps de l’article

Introduction

As increasing numbers of non-European or “visible minority” immigrants have entered the Canadian labour market, their successful social and economic integration has become an issue of growing concern. The traditional view among scholars was that new immigrants start their Canadian careers with considerable disadvantage, but gradually reach and even surpass the wages of the native-born. This pattern was found to be generally true among European immigrants who arrived prior to the 1970s (Meng, 1987).

However, over the past decade, research studies have found that the visible minority immigrants arriving after the 1970s face greater disadvantages in the labour market than the previous, mostly European, cohorts (Bloom and Gunderson, 1991; Baker and Benjamin, 1994; Bloom, Grenier and Gunderson, 1995). In fact, newer visible minority immigrants may not catch up to the wages of their native-born counterparts within their lifetimes. Given the significant numbers of immigrants in Canada and the apparent decline in the labour market position of recent immigrants, it is imperative to understand the disadvantages that this group faces in the labour market.

Two important factors contribute to new immigrants’ labour market success. The first is the wage at which they begin their Canadian careers (known as the “entry effect”). It is well known that immigrants enter the Canadian labour market with considerable disadvantage and that this disadvantage is greater for those of non-European origins. The initial disadvantage may be caused by a lack of recognition of credentials and foreign work experience, a lack of English or French language skills, a lack of knowledge of Canadian job search resources or discriminatory hiring practices.

The second factor that contributes to immigrants’ labour market success is their ability to catch-up to the wages of their native-born counterparts over time (referred to as the “assimilation effect”). Since it is well established that newer immigrants start their Canadian careers at lower wages than their native-born counterparts, above-average wage growth in the early years of immigration is crucial for them to achieve income parity with native-born Canadians. Studies over the past decade have found that non-European immigrants experience far slower assimilation rates than their European counterparts (e.g. Reitz, 2001; Li, 2003).

To date most of the studies examining immigrants’ earnings progression have been based on cross-sectional data. In these studies, new immigrants’ future earnings progression is estimated using the earnings patterns of previous cohorts of immigrants. This methodology has been criticized, since earnings patterns of previous cohorts may not accurately project the expected earnings progression of newer immigrants, particularly because the source countries of newer immigrants have shifted so drastically (Borjas, 1985). Another disadvantage of using cross-sectional data is that there is no way of correcting for unobserved individual heterogeneity, which may lead to biased results (Hum and Simpson, 2000). Longitudinal data would allow us to control for these factors.

To gain a clearer understanding of new immigrants’ earnings progression, analyses based on longitudinal data are imperative. To that end, the present study utilizes the longitudinal Survey of Labour and Income Dynamics (SLID) (1999–2004) in order to investigate whether new immigrants experience a period of accelerated earnings growth or “catch-up” at the start of their Canadian careers, and whether visible minority status affects new immigrants’ earnings growth. Finally, the present analysis investigates the factors affecting new immigrants’ earnings growth. By utilizing longitudinal data and a specialized methodology, this study provides insight into the relationship between race, recent immigrant status and earnings progression.

Previous Research

Numerous previous studies have examined the initial earnings disadvantage that immigrants face in the Canadian labour market (the “entry effect”), and their ability to “catch-up” to the earnings of their native-born counterparts over time (the “assimilation effect”). There is general consensus that newer immigrants face significant disadvantage both initially and over time (e.g. Bloom, Grenier and Gunderson, 1995; Reitz, 2001; Frenette and Morissette, 2003; Aydemir and Skuterud, 2005), and that this disadvantage is greater for non-European or visible minority immigrants than for those of European origins (e.g. Baker and Benjamin, 1997; Pendakur and Pendakur, 1998; Hum and Simpson, 1999; Swidinsky and Swidinsky, 2002).

Bloom, Grenier and Gunderson (1995) examined the 1971, 1981 and 1986 Censuses and found that while the negative entry effect for European immigrant men was about 1.5 percent, for non-European immigrant men, the entry effect was closer to 22 percent. Furthermore, this study found the assimilation rates of non-European immigrants to be far slower than that of Europeans. Overall, Bloom, Grenier and Gunderson (1995) concluded that newer cohorts of immigrants face greater disadvantage in the Canadian labour market than earlier cohorts, and that non-European immigrants are especially disadvantaged.

Li (2003) utilized the Longitudinal Immigrant Database (IMDB) from 1980 to 1996 to examine new immigrants’ earnings. Since this database contains information for immigrants only, the study utilized national earnings averages as the benchmark. Li (2003) found that immigrants from racial minority backgrounds took far longer to catch-up to the earnings of Canadian-born workers than those from Western Europe or America. Among men, immigrants from China were predicted to take the longest to catch-up at 17.7 years, followed by those from West Asia (9.2 years) and South Asia (8.3 years).

Using the 1981, 1986, 1991, 1996 and 2001 Censuses, Aydemir and Skuterud (2005) also found that country of origin played a major role in the disadvantage faced by new immigrants. In fact, they attributed one-third of the overall decline in immigrants’ earnings over the past three decades to the shift in the origins of newer immigrants from Europe to Asia, Africa and Latin America.

Due to a lack of reliable longitudinal data sources, nearly all of the past studies on this topic have estimated the entry and assimilation effects using cross-sectional data. However, this approach may not accurately isolate and measure the effects. Cross-sectional studies may produce misleading results for several reasons.

First, in cross-sectional studies it is difficult to correct for unobserved differences in the characteristics of immigrants and native-born workers (heterogeneity). If the heterogeneity across individuals in the sample is random, then it does not pose a problem. If however, the unobserved differences are systematically correlated with some observed characteristic and the outcome measure, then the estimates of the earnings gap may be biased. For instance, immigrants may differ from the native-born in terms of some unobserved characteristic such as motivation or ability. These differences may, in turn, be correlated with visible minority status or ethnic origin. Hence, earnings differences between immigrants and Canadian-born workers could be falsely attributed to visible minority status or ethnicity, instead of the unobserved heterogeneity (Hum and Simpson, 2000). Longitudinal data would allow us to control for such time-invariant individual heterogeneity.

Second, cross-sectional studies may lead to biased results due to the practice of using previous immigrant cohorts’ patterns of earnings growth to project the earnings growth of subsequent cohorts. This practice makes it difficult to separate “cohort effects” from “assimilation effects” (Borjas, 1985). That is, there may be observed and unobserved differences between cohorts which could cause their patterns of earnings growth to differ. Therefore, using the earnings growth of one cohort to predict that of another cohort may lead to biased results.

Many recent studies have tried to overcome this problem by utilizing the quasi-panel technique of combining several years of cross-sectional data. However, since the same individuals are not surveyed in each period, this method does not fully replicate longitudinal data. Among other problems, there is the problem of selective return to the home country (see Borjas and Bratsberg, 1996; DeVoretz, Ma and Zhang, 2003; Aydemir and Robinson, 2006). Since some immigrants may return to their country of origin or migrate to another destination if they are unsuccessful in Canada, surveying different groups of immigrants at different points in time could lead to data on only relatively successful immigrants (since the unsuccessful immigrants would have left the country).

The problems associated with cross-sectional data can only truly be resolved by analyzing longitudinal panel data, which allows the same group of immigrants (and their native-born counterparts) to be followed over time. Until recently, Canadian sources of longitudinal data on immigrants’ labour market outcomes were difficult to obtain.

Hum and Simpson (2000) were among the first to analyze longitudinal panel data to compare the wage growth of immigrants to that of their native-born counterparts. This study utilized the Survey of Labour and Income Dynamics (1993 to 1997) to examine the difference between 1993 and 1998 wages of immigrants and native-born Canadians, after controlling for human capital, demographic and geographic characteristics. This study did not find immigrants’ wage growth to be significantly different from that of the native-born. Hence, they concluded that immigrants did not experience any “catch-up” during this period. Hum and Simpson (2000) also did not find visible minority status to affect wage growth.

Hypotheses

Newly arrived immigrants may be expected to have higher income growth than their native born counterparts for several reasons. First, new immigrants often invest in their human capital through formal education, language training, social networking, etc., and in doing so improve their understanding and knowledge of the local labour market (Borjas, 1994; Chiswick and Miller, 1994; Duleep and Regets, 1999; Friedberg, 2000; Bratsberg and Ragan, 2002). This investment may lead to an initial period of accelerated income growth for new immigrants during which their earnings are “catching-up” with native-born earnings. This “catch-up” effect may be observable even when there is a negative entry effect and a persistent long-term income disadvantage.

Second, new immigrants may be “mismatched” in their initial job placements in the Canadian labour market. This mismatch may be due to a lack of accurate information about the Canadian labour market as well as the actions of employers who have imperfect information about the value and quality of foreign credentials and work experience. The less-than-perfect international transferability of human capital is likely to lead to many new immigrants being overqualified for their jobs during their first years in Canada (Chiswick and Miller, 2007). As new immigrants gain Canadian-specific experience, and employers become familiar with the skills and abilities of these new arrivals, they are more likely to get jobs that match their human capital endowments, and experience rapid earnings growth. A similar process of “catch-up” occurs with new labour force entrants, such as youth, in the general population (Groot and Maasen van den Brink, 2000). Research hypothesis 1 is grounded in these theoretical perspectives:

HYPOTHESIS 1: Newly arrived immigrants will experience greater income growth than their native-born counterparts.

Although new immigrants may be expected to have greater income growth than the native born majority, visible minority status is expected to decrease new immigrants’ income growth. As discussed in the previous section, nearly all analyses of immigrants’ earnings in Canada have found that immigrants of non-European origins face greater disadvantage in the labour market than those of European origins. This racial difference has been attributed to a variety of factors.

Bloom, Grenier and Gunderson (1995) attributed visible minority immigrants’ relative disadvantage to their lower “quality in terms of attributes that facilitate assimilation into the labour market,” as well as racial discrimination on the part of employers. The implication is that non-European immigrants may not “fit in” to the Canadian labour market as readily as their European counterparts, perhaps because of lower quality of education and experience, greater difficulties with official language knowledge, and the discriminatory behaviour of employers.

Li (2001) and Reitz (2003) concluded that the devaluation of foreign credentials adversely affects visible minority immigrants more than white immigrants. Aydemir and Skuterud (2005) found similar results for work experience: immigrants from non-European source countries face greater difficulty in having foreign work experience recognized than their European counterparts. The transferability of foreign human capital may pose greater problems for non-European immigrants than for their European counterparts for several reasons.

First, quality of educational qualifications may be correlated with source country and therefore visible minority status (Sweetman, 2004). Second, irrespective of quality, the relevance and applicability of education and work experience may be related to source country. Immigrants arriving from countries with labour markets and institutions that differ significantly from those of Canada may face greater difficulty integrating into the Canadian system because employers are unsure of how to judge the relevance of their human capital (Chiswick and Miller, 2007). This is likely to disadvantage non-European immigrants relative to their European counterparts. In summary, it may be that there are unobservable differences in the quality and relevance of non-European immigrants’ educational qualifications and work experience, which makes it less valuable in the Canadian labour market. Third, while quality and applicability of human capital may be important factors, racial discrimination may also play a role in the devaluing of visible minority immigrants’ human capital. Esses, Dietz and Bhardwaj (2003) concluded through a series of experiments that racist attitudes affect the perceived value of foreign qualifications: individuals exhibiting racist or prejudiced attitudes believe foreign qualifications to be of lower quality than do those without racist attitudes.

In addition to human capital devaluation, lack of language ability may also disadvantage visible minority immigrants relative to their European counterparts. Chiswick and Miller (1995, 2001) examined destination language ability and found that, among other factors, linguistic distance between the languages of the home and destination countries negatively affects language acquisition. While intuitively this may suggest that non-European immigrants to Canada should have lower official language ability, in fact, Chiswick and Miller’s empirical analysis of the 1991 Canadian census indicates that this is not necessarily the case. Although source country was found to be a significant predictor of official language ability, European immigrants were not more likely to be able to speak English or French, on average, than non-European immigrants. Instead, there was significant variation within European and non-European immigrant groups (Chiswick and Miller, 2001).

While linguistic ability is a significant predictor of labour market integration, employers’ perceptions of linguistic ability may be just as important. Even immigrants who are fluent in an official language usually speak with noticeable ethnic markers such as an accent. Scassa (1994) noted that some foreign accents of speech are considered by Canadian employers to be more desirable than others, and that race often determines which accents are deemed acceptable and which are not. Creese and Kambere (2003) found that among African immigrant women who were fluent in English, accent was perceived to be a basis for discrimination. Henry and Ginsberg (1985) found in their study of employment discrimination in Toronto that job applicants with noticeable racial markers in their speech were often eliminated when they telephoned potential employers about job vacancies. These studies indicate that racial discrimination may play a role in how employers evaluate immigrants’ language ability.

Given the extra barriers faced by visible minority immigrants in the Canadian labour market, I expect lower income growth for this group during the critical catch-up phase. Thus:

HYPOTHESIS 2: Visible minority recent immigrants will experience slower income growth than white recent immigrants.

Data and Measures

In order to avoid the problems and complications associated with using cross-sectional data, I utilize the Survey of Labour and Income Dynamics (SLID). Since the SLID is a longitudinal panel survey, it is ideal for measuring income growth over time. The SLID sample is composed of three panels. Each panel includes about 15,000 households and is surveyed for a period of six consecutive years. Panel 1 ran from 1993 to 1998, Panel 2 from 1996 to 2001, and Panel 3 from 1999 to 2004. The present study utilizes data from the last panel of the SLID (1999–2004) to examine the most current evidence on new immigrants’ income growth. By utilizing panel 3, we are able to obtain a picture of how recent immigrants to Canada are faring in the new millennium.

The samples for SLID are selected from the monthly Labour Force Survey (LFS). All individuals in Canada, excluding residents of the Yukon, the Northwest Territories and Nunavut, are included in the target population of the SLID (Statistics Canada, 2004). The sample design emphasizes equal representation from all provinces, reducing the representation of immigrant groups (since these groups tend to be in the larger provinces).

Since the current study is interested in income growth, only those respondents between the ages of 20 and 60 (i.e. working age) who worked for pay in at least two years of the panel are included in the sample. These restrictions result in a total sample size of 12,356. Each individual in the sample worked for at least two and at most six years during the panel.

The outcome variable in this analysis is a series of repeated measures of individual i’s yearly income at time t. The starting point of this variable is annual employment earnings. This includes tips, bonuses and self-employment income.[1] The natural logarithm of each respondent’s yearly income in constant 2004 dollars[2] is set as the outcome variable.

The key explanatory variable in this analysis represents immigrant and visible minority status. Immigrant and visible minority status are measured using a single set of six dummy variables[3] representing: (1) visible minority recent immigrants; (2) white recent immigrants; (3) visible minority earlier immigrants; (4) white earlier immigrants; (5) native-born visible minorities; and (6) white native-born Canadians. White native-born Canadians form the omitted reference category since this group represents the majority of the Canadian population and are generally thought of as the “mainstream.”

Foreign-born individuals who arrived in Canada less than ten years prior to the date of survey are considered “recent immigrants.” Thus, immigrants arriving after 1989 are considered “recent immigrants.” Foreign-born individuals who arrived in Canada more than ten years prior to the date of survey are considered to be “earlier immigrants.” Since the primary focus of the present study is on recent immigrants, results for other groups such as earlier immigrants and native born visible minorities are not discussed in detail even though these groups are included in the analysis.

Due to small sample sizes for some specific visible minority groups, for this study visible minority status is simply dichotomized, coded “1” for visible minorities and “0” for whites.[4]

Control variables in this study include gender, years of work experience, level of education, total number of hours worked during the year, number of jobs held during the year, union status, marital status, presence of preschool aged children, first language,[5] province of residence and size of city/town of residence. Most control variables in this analysis, with the exceptions of gender and first language, are time-varying. That is, their values are allowed to change by time period.

Studies in this area often tend to examine the earnings of men and women separately, since gender differences in career progression are well documented (see Maume Jr., 1999). Furthermore, the relationship between gender, immigrant status, race and labour market success is known to be quite complex. The intersection between gender, immigrant status, race and earnings certainly deserves special attention. However, given the small size of the recent immigrant sample in the SLID, separate analyses are not conducted by gender in the present study. Interaction terms between gender and recent immigrant status were examined, but were found not to have significant effects on income growth and were therefore removed from the model.[6]

Data Analysis Strategy

Given the longitudinal nature of the data, ordinary least squares (OLS) regression models are inappropriate for this study. In OLS regression, the error terms are assumed to be normally and independently distributed with a mean of zero and a common variance, σ2. Since the outcome variable in this study (yearly income) is observed repeatedly from the same individuals, it is likely that the errors for the same individual are correlated to some degree and heteroscedastic over time (Singer and Willett, 2003). Thus, it is important to add individual-specific error into the model that will account for the data dependency and heteroscedasticity.

Growth curve modeling is a variant of multi-level or hierarchical linear modeling and recognizes and accounts for the nested nature of longitudinal data (Raudenbush and Bryk, 2002). Growth curve models are conducted at two levels. At level 1, each individual’s growth is modeled over time, producing a within-person trajectory of growth. At level 2, between-person differences in growth are examined. The level 2 analysis allows me to examine how differences in individual characteristics affect growth.

Traditionally, longitudinal data has been handled using repeated measures ANOVAs or fixed-effects regressions.[7] Growth curve models offer numerous advantages to these traditional methods of studying change. They provide more precise estimates of individual growth over time and have greater power to detect predictors of individual differences in growth. In addition, they allow the inclusion of individuals not assessed at every time point, using any available data points to fit a growth trajectory for each individual. Lastly, growth curve modeling can include both time-varying and time-invariant covariates (Raudenbush and Bryk, 2002).

In this study, the level 1 or within-person model estimates yearly income as a linear function of the number of years since the first interview in 1999:[8]

In equation 1, Incometi represents the yearly income for individual i in year t. To aid interpretation, time is coded as “year minus 1999.” With this coding, π0i represents individual i’s true income in 1999 (the first measurement point in the study, when time equals 0) and π1i represents individual i’s true rate of yearly income growth. In other words, π0i is the intercept, and π1i is the slope. In Equation 1, εti represents level 1 residual variance or the portion of individual i’s annual income at time t that is unexplained.

At level 2, the individual growth parameters become the outcome variables. This specification enables us to determine whether π0i (initial income in 1999 or intercept), or π1i (yearly rate of income growth or slope) differ by recent immigrant and visible minority status:

In Equation 2, the intercept component of the model, β00 represents the population’s true average income in 1999, β01 represents the effect of recent immigrant and visible minority status on this initial income and υ0i represents individual i’s deviation from the population’s average initial income due to unobserved individual heterogeneity. In equation 3, the slope component of the model, β10 represents the population’s true average annual rate of change in income, β11 is the effect of recent immigrant and visible minority status on the annual rate of change in income and υ1i is individual i’s deviation from the population’s average annual rate of change in income, again due to unobserved individual heterogeneity. VMimmstat represents the recent immigrant and visible minority status of individual i (coded as “1” for individuals who are visible minority recent immigrants and “0” for those who are not).

By substituting Equations 2 and 3 into Equation 1, and re-arranging the terms to collect all the error components together, we arrive at the composite specification of the model:

Incometi = β00 + β10timeti + β01VMimmstati + β11(VMimmstati *timeti) + υ0i + υ1itimeti + eti

This specification clearly shows how income depends simultaneously on time, recent immigrant and visible minority status and the interaction between these two. The interaction term implies that recent immigrant and visible minority status may alter the effect of time on income (i.e. the slope). The last three terms in the equation, the error terms, account for the fact that unobserved individual heterogeneity may affect both within-person income growth, as well as between-person differences in the intercept (initial income in 1999) and the slope (annual rate of change in income). The first four terms in Equation 4 are referred to as “fixed effects,” while the last three (the error terms) are referred to as “random effects.”

In addition to the main explanatory variable of interest shown in Equation 4 (VMimmstat), the control variables described in the previous section are also included in the model. In order to ease interpretation of the model’s intercept and slope, all continuous control variables (years of work experience, hours worked and number of jobs held) are centered at each time period by subtracting the group mean from the individual mean. With this centering, π0i and π1i respectively represent the expected income in 1999 and the annual rate of change in income for respondents with average years of work experience, hours worked and number of jobs held. Categorical control variables are not centered. All control variables are entered into both the intercept and slope components of the model.[9]

Before conducting the full growth curve analysis described above, with all the explanatory and control variables entered into the model, it is important to construct an “unconditional growth model.” An unconditional growth model is a model with time as the only level 1 predictor and no substantive predictors at level 2. The unconditional growth model helps to evaluate the baseline amount of income growth in the population, as well as the between-person heterogeneity in this growth. It is important to establish that there is some amount of growth in the outcome variable and that between-person heterogeneity actually exists before undertaking growth curve analysis.[10]

Findings

Descriptive statistics in Table 1 reveal that before controlling for other factors, both white and visible minority recent immigrants have much lower annual income in 1999 than native-born whites. By 2004, a racial difference in recent immigrants’ income is apparent. While white recent immigrants have nearly caught-up to their native born counterparts, visible minority recent immigrants still lag behind.

Table 1

Selected Descriptive Statistics for Visible Minority Immigrants, White Immigrants and White Native Born Canadians, 1999 and 2004

|

1999 |

2004 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Visible Minority Recent Immigrant |

White Recent Immigrant |

White Native Born |

Visible Minority Recent Immigrant |

White Recent Immigrant |

White Native Born |

|

N = 197 |

N = 119 |

N = 10,954 |

N = 197 |

N = 119 |

N = 10,954 |

Annual Income |

$28,372 |

$29,208 |

$36,466 |

$33,249 |

$41,640 |

$41,849 |

Age |

35.6 |

35.9 |

37.7 |

40.6 |

40.9 |

42.7 |

Female |

44.7% |

34.1% |

48.0% |

44.7% |

34.1% |

48.0% |

Years of Work Experience |

9.5 |

9.9 |

14.7 |

14.3 |

14.9 |

19.7 |

Unionized |

13.2% |

26.2% |

35.9% |

20.2% |

34.1% |

37.2% |

High School or Less Education |

49.7% |

35.6% |

47.6% |

38.9% |

23.1% |

39.9% |

College Education |

18.0% |

36.1% |

32.9% |

23.9% |

46.8% |

36.9% |

University Education |

32.3% |

28.4% |

19.5% |

37.2% |

30.1% |

23.2% |

Married |

68.6% |

70.6% |

65.3% |

73.9% |

74.0% |

68.4% |

Pre-school Children |

34.5% |

24.8% |

26.3% |

30.0% |

25.2% |

20.7% |

Annual Hours Worked |

1528.5 |

1645.6 |

1731.7 |

1692.0 |

1926.7 |

1794.6 |

Number of Jobs Held |

1.07 |

1.11 |

1.15 |

1.06 |

1.16 |

1.14 |

Non-Official 1st Language |

90.6% |

66.1% |

4.5% |

90.6% |

66.1% |

4.5% |

Years since Migration |

5.2 |

5.5 |

- |

10.2 |

10.5 |

- |

Examining the control variables reveals some interesting trends as well. On average, recent immigrants, both visible minority and white, have been in Canada for about 5 years. Recent immigrants have less work experience than the native born. It may be assumed that about half of the work experience reported by recent immigrants was accumulated outside of Canada on average (since they have been in Canada for about 5 years and report nearly 10 years of work experience). Recent immigrant workers are far less likely than the native-born to be covered by a collective agreement in 1999. Visible minority recent immigrants are the least likely to have collective agreement coverage in 1999 (13.2%), followed by white recent immigrants (26.2%). This is compared to 35.8% of white native-born workers with collective agreement coverage. It is notable that by 2004, the recent immigrants have “assimilated” into unionization. Among visible minorities, 20.2% are covered by a collective agreement by 2004, while among whites the percentage has risen to 34.1%.

Examining education, it is apparent that both visible minority and white recent immigrants are more likely than white native-born Canadians to possess a university degree in 1999. While only about 20% of white native-born Canadians have university education in 1999, about 32% of visible minority recent immigrants and 28% of white recent immigrants are university educated. College education is most prevalent among white recent immigrants (36.1%) and native-born whites (32.9%). Visible minority recent immigrants are less likely than the white groups to possess a college education (18.0%) in 1999.

By 2004, it is evident that recent immigrants are more likely to engage in further education than native-born whites. Visible minority recent immigrants are the most likely to have obtained a university degree during the six years of the panel. By 2004, the number of individuals in this group with a university degree has increased by about 5 percentage points to 37%. In contrast, white recent immigrants and native-born whites are less likely to have obtained a university degree by 2004 (30.1% and 23.2% respectively). While visible minority immigrants are the most likely to engage in university education, white recent immigrants seem more inclined to pursue college education. By 2004, the number of white recent immigrants with a college diploma has increased by nearly 10 percentage points to 46.8%. Among visible minority recent immigrants, the number of individuals with a college education has increased by about 6 percentage points to reach 23.9% by 2004. In contrast, about 37% of native-born whites have a college diploma by 2004 (an increase of 4 percentage points).

As would be expected, recent immigrants are far more likely to speak a non-official first language than native-born Canadians, with over 90% of visible minority recent immigrants and 66% of white recent immigrants reporting a foreign first language. Only about 5% of white native-born Canadians claim a first language other than English or French.

Before examining the final growth curve model, it is important to examine the unconditional growth model. Results of the unconditional growth model can be seen in Table 2. The intercept of 10.07 indicates the mean level of annual income (in log dollars) for the sample in 1999, while the significant positive slope coefficient indicates that annual income increased by 0.80 percentage points per year on average. Examination of the error terms reveals significant heterogeneity in both the intercept and slope coefficients. This result indicates that these coefficients should be allowed to vary at level-2, and predictors of inter-individual differences should be explored. Thus, growth curve analysis is indeed warranted.

Table 2

Unconditional Growth Model of Logged Annual Income, 1999-2004

|

Coefficient |

Standard Error |

|---|---|---|

FIXED EFFECTS |

|

|

Intercept (Initial Income in 1999) |

10.07*** |

0.01 |

Slope (Annual Income Growth) |

0.008*** |

0.002 |

RANDOM EFFECTS |

|

|

Intercept (Between-person variance in initial income in 1999) |

1.005*** |

0.016 |

Slope (Between-person variance in annual income growth) |

0.044*** |

0.0008 |

Level 1 Error (Within-person variance) |

0.266*** |

0.002 |

Number of Respondents |

12,356 |

|

Number of Observations |

69,019 |

|

-2 log-likelihood |

173,345.2 |

|

Significance: *** < 0.01; ** < 0.05; * < 0.10

In the full growth curve model, presented in Table 3, control variables include gender, years of work experience (centered), postsecondary education, hours worked (centered), number of jobs held (centered), union status, marital status, presence of pre-school aged children, first language, province and size of city/town of residence. The intercept β00 provides the expected annual income in 1999 when all covariates are 0; that is, for non-unionized native born white men, with average years of work experience, hours worked and number of jobs, without a post-secondary education.[11] On average, such individuals earned $24,671 in 1999 in inflation-adjusted 2004 dollars. The slope β10 indicates that the reference group experienced an average annual income growth rate of 2.4 percentage points.

Table 3

Growth Model of Logged Annual Income, 1999-2004

|

Coefficient |

Standard Error |

|

|---|---|---|---|

FIXED EFFECTS |

|

|

|

Intercept (Average Initial Income in 1999) |

10.107*** |

0.018 |

|

Covariate effect on initial income | |||

|

VM Recent Immigrant |

-0.266*** |

0.056 |

|

White Recent Immigrant |

-0.240*** |

0.067 |

|

Female |

-0.338*** |

0.013 |

|

Years of Experience |

0.0172*** |

0.0006 |

|

College Diploma |

0.182*** |

0.013 |

|

University Degree |

0.458*** |

0.016 |

|

Work Hours |

0.0005*** |

0.000006 |

|

Unionized |

0.201*** |

0.010 |

|

Number of Jobs |

-0.087*** |

0.008 |

|

Married |

0.090*** |

0.012 |

|

Preschool Children |

-0.054*** |

0.009 |

|

Non-Official 1st Language |

-0.030*** |

0.028 |

Slope (Average Annual Income Growth) |

0.023*** |

0.005 |

|

Covariate effect on income growth |

|

|

|

|

VM Recent Immigrant |

0.0008 |

0.013 |

|

White Recent Immigrant |

0.041*** |

0.016 |

|

Female |

-0.003 |

0.003 |

|

Years of Experience |

-0.002*** |

0.0002 |

|

College Diploma |

0.003 |

0.004 |

|

University Degree |

0.010** |

0.004 |

|

Work Hours |

-0.000003* |

0.000002 |

|

Unionized |

0.004 |

0.003 |

|

Number of Jobs |

-0.007*** |

0.003 |

|

Married |

-0.010*** |

0.004 |

|

Preschool Children |

0.0004 |

0.003 |

|

Non-Official 1st Language |

-0.006 |

0.007 |

RANDOM EFFECTS |

|

|

|

|

Intercept, υ0i |

0.360*** |

0.007 |

|

Slope, υ1i |

0.015*** |

0.0004 |

|

Level 1 Error, εti |

0.128*** |

0.001 |

Number of Respondents |

11,703 |

||

Number of Observations |

57,280 |

||

-2 log-likelihood |

99,956.8 |

Note: Controlling for province and size of city/town; Non-recent immigrants and native born visible minorities were also included in the analysis, but not shown; Significance: *** < 0.01; ** < 0.05; * < 0.10.

It is apparent from Table 3 that both visible minority and white recent immigrants face significant earnings disadvantage in 1999. Visible minority recent immigrants earn about 27 percentage points less than comparable native-born whites, while white recent immigrants earn 24 percentage points less than their native-born counterparts. The interaction term between time and recent immigrant status tells us whether recent immigrants experience greater or less annual income growth than white native-born Canadians, after controlling for other factors. For visible minority recent immigrants, this term is not statistically significant, which indicates that this group does not experience a significantly different rate of income growth than white native-born Canadians. For white recent immigrants, however, this interaction term is statistically significant and positive. In fact, white recent immigrants experience an annual income growth that is 4.1 percentage points greater than that of the reference group.

The control variables also yield some noteworthy effects. As expected, being female has a significantly negative effect on initial earnings (p < 0.01). In fact, women earn 33.8 percentage points less than their male counterparts in 1999.[12] However, gender is found not to affect income growth. Each additional year of work experience improves initial earnings in 1999 by 1.7 percentage points (p < 0.01), but decreases the annual rate of income growth by 0.22 percentage points (p < 0.01). Having a college education improves initial income in 1999 by 18.2 percentage points (p < 0.01), but does not affect income growth. On the other hand, having a university degree improves initial income in 1999 by 45.8 percentage points (p < 0.01) and improves annual rate of income growth by nearly 1 percentage point (p < 0.05).

Each additional job held during the year decreases initial income in 1999 by 8.7 percentage points (p < 0.01) and decreases annual income growth by 0.67 percentage points (p < 0.05). Each additional hour worked per year improves initial earnings by about 0.05 percentage points (p < 0.01). Unionization improves initial income in 1999 by 20.1 percentage points (p < 0.01), but has no effect on income growth. Being married improves initial income by about 9 percentage points (p < 0.01), but reduces annual income growth by 1 percentage point (p < 0.01). The presence of pre-school aged children reduces 1999 income by 5.5 percentage points (p < 0.01), but has no effect on income growth. For the reference category, speaking a non-official first language (other than English or French) reduces initial income by about 3 percentage points, but this is not statistically significant (p > 0.10). Non-official first language is not found to affect income growth.

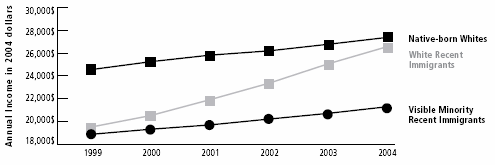

To illustrate how income trajectories vary by recent immigrant and visible minority status, Figure 1 presents the predicted income-growth trajectories of white native-born Canadians, visible minority recent immigrants and white recent immigrants by year.

Two main conclusions are apparent from this figure. First, both visible minority and white recent immigrants earn considerably less than native-born whites in 1999, even after controlling for other factors. Second, there is a significant racial difference in recent immigrants’ income growth between 1999 and 2004. While white recent immigrants experience above average income growth and nearly close the income gap by 2004, visible minority recent immigrants are unable to catch-up to native-born whites during the six years of the panel.

Figure 1

Predicted income growth of Visible Minority recent immigrants, White recent immigrantsand Native-born Whites, 1999-2004

Next, in order to investigate the factors contributing to the disadvantage faced by recent immigrants, income growth curve models are conducted separately for visible minority recent immigrants and white recent immigrants. For reference, an income growth curve model is also estimated for white native-born Canadians. Due to the small sample sizes of the recent immigrant groups, the model is simplified by removing any explanatory variables from the slope component of the model that are found not to have a significant effect on annual income growth.[13] With this simplification, time, gender, years of work experience, level of education, total number of hours worked during the year, number of jobs held during the year, union status, marital status, presence of preschool aged children, first language, province of residence and size of city/town of residence are included as explanatory variables in the intercept component of the model (initial income in 1999), while only years of work experience is included as an explanatory variable in the slope component of the model (annual income growth). For ease of comparison, the same model specification is utilized for the white native-born Canadian group. The results of these analyses are presented in Table 4.

Since the sample sizes of the recent immigrant groups are relatively small (179 for visible minority recent immigrants and 111 for white recent immigrants), the results from these analyses may downplay the statistical significance of the explanatory variables (see Fan, 2003). Despite this, they still provide some noteworthy findings. From Table 4 it is apparent that years of work experience affects income similarly for all groups, although visible minority recent immigrants are rewarded less than the two white groups. Education is found to be quite discounted for recent immigrants. Among white native-born Canadians, college education improves income by about 19 percentage points. For white recent immigrants this improvement is only about 14 percentage points and for visible minority recent immigrants, college education does not seem to improve income at all. University education improves white native-born Canadians’ annual income by about 49 percentage points. In contrast, university education improves white recent immigrants’ income by only 22 percentage points, and visible minority recent immigrants’ income by about 20 percentage points. Unionization is another factor that seems to differentially affect visible minority and white recent immigrants. While unionization improves white native-born Canadians’ annual income in 1999 by about 21 percentage points, for visible minority recent immigrants, this improvement is only about 17 percentage points. In contrast, the unionization premium for white recent immigrants is about 32 percentage points. This indicates that while visible minority recent immigrants benefit less from unionization than white native-born Canadians, white recent immigrants actually seem to benefit more.

Table 4

Growth Model of Logged Annual Income, 1999-2004, for Visible Minority Recent Immigrants, White RecentImmigrants and White Native Born Canadians

|

White Native Born |

Visible Minority Recent Immigrant |

White Recent Immigrant |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Coefficient |

Standard Error |

Coefficient |

Standard Error |

Coefficient |

Standard Error |

|

FIXED EFFECTS |

|

||||||

Intercept (Average Initial Income in 1999) |

9.974*** |

0.013 |

10.209*** |

0.249 |

10.087*** |

0.194 |

|

Covariate effect on initial income |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Female |

-0.341*** |

0.012 |

-0.385*** |

0.102 |

-0.299** |

0.137 |

|

Years of Work Experience |

0.018*** |

0.001 |

0.011 |

0.007 |

0.017** |

0.008 |

|

College Diploma |

0.191*** |

0.011 |

-0.010 |

0.108 |

0.142 |

0.112 |

|

University Degree |

0.489*** |

0.015 |

0.196* |

0.106 |

0.221* |

0.134 |

|

Work Hours |

0.0004*** |

0.000004 |

0.0005*** |

0.00004 |

0.0005*** |

0.00004 |

|

Unionized |

0.206*** |

0.008 |

0.166** |

0.073 |

0.325*** |

0.070 |

|

Number of Jobs |

-0.107*** |

0.005 |

-0.082* |

0.045 |

0.013 |

0.043 |

|

Married |

0.069*** |

0.009 |

0.061 |

0.087 |

-0.015 |

0.123 |

|

Preschool Children |

-0.056*** |

0.007 |

0.013 |

0.053 |

-0.089 |

0.062 |

|

Non-Official 1st Language |

0.065* |

0.034 |

-0.400** |

0.185 |

-0.235 |

0.146 |

Slope (Average Annual Income Growth) |

0.021*** |

0.002 |

0.029 |

0.019 |

0.058*** |

0.015 |

|

Covariate effect on income growth |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Years of Work Experience |

-0.002*** |

0.0002 |

-0.001 |

0.002 |

-0.003* |

0.002 |

RANDOM EFFECTS |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Intercept, υ0i |

0.363*** |

0.007 |

0.584*** |

0.083 |

0.694*** |

0.105 |

|

Slope, υ1i |

0.014*** |

0.0004 |

0.029*** |

0.006 |

0.009*** |

0.003 |

|

Level 1 Error, εti |

0.119*** |

0.001 |

0.365*** |

0.025 |

0.184*** |

0.014 |

Number of Respondents |

10,403 |

179 |

111 |

||||

Number of Observations |

51,234 |

771 |

522 |

||||

-2 log-likelihood |

88,569.5 |

1,522.0 |

863.2 |

Note: Controlling for size of city/town; Significance: *** < 0.01; ** < 0.05; * < 0.10

Lastly, it is noteworthy that having a non-official first language (other than English or French) affects each group very differently. While a non-official first language actually improves white native-born Canadians’ annual income slightly, it has detrimental effects on recent immigrants’ income. A non-official first language especially disadvantages visible minority immigrants. While non-official first language decreases annual income for white recent immigrants by about 23 percentage points, for visible minority recent immigrants this decrease is 40 percentage points. This indicates that language knowledge is another factor that disadvantages visible minority recent immigrants more than their white counterparts.

Examining the slope component of the model (time), it is evident that consistent with the findings in Table 3, white recent immigrants experience far greater income growth between 1999 and 2004 than both white native-born Canadians and visible minority recent immigrants.

Discussion and Conclusion

The analyses in this paper produce some noteworthy findings. Firstly, recent immigrants, regardless of visible minority status, face significant initial earnings disadvantage early in their Canadian careers. This finding is not surprising in itself and confirms the general findings of Frenette and Morissette (2003) and others.

Second, the present analyses indicate that while white recent immigrants are able to overcome their initial disadvantage through accelerated income growth, visible minority immigrants do not enjoy such a catch-up. These findings are also consistent with previous studies that indicate that visible minority immigrants face greater barriers to labour market integration than do their white counterparts (see Baker and Benjamin, 1997; Hum and Simpson, 1999; Swidinsky and Swidinsky, 2002; Aydemir and Skuterud, 2005 among others).

Since white recent immigrants are found to experience faster income growth than their native-born counterparts, Hypothesis 1 is partially supported. It is evident that white recent immigrants are able to economically assimilate in the Canadian labour market. Hypothesis 2 is also supported, since visible minority immigrants’ income growth falls well below that of their white counterparts. In fact, visible minority recent immigrants’ income growth is not found to be significantly different from that of white native-born Canadians. Thus, there is no evidence for economic assimilation among this group.

These results only partially support those of Hum and Simpson (2000), who found no evidence of economic assimilation among any immigrants, visible minority or white, using the 1993 to 1998 SLID. The present analysis was also conducted using the more traditional methodology employed by Hum and Simpson (2000) (results available upon request). The results from that analysis were very similar to those presented in this study. Visible minority recent immigrants’ earnings growth was not significantly different from that of the reference group, but white recent immigrants had significantly greater earnings growth between 1999 and 2004. The differences in the results of the present study and those of Hum and Simpson (2000) may be explained by differences in the focus and assumptions of the two studies.[14] The difference in results may also indicate a change in white immigrants’ labour market performance in the new millennium.

Upon closer examination, it is apparent in the present analysis that education, work experience, unionization and first language play major roles in the disadvantage faced by visible minority recent immigrants. In particular, visible minority recent immigrants do not benefit from possessing a college education or other non-university post-secondary education nearly as much as do their white counterparts. This seems to indicate that Canadian employers especially view non-university post-secondary institutions from regions outside of North America and Europe as being of inferior quality or less relevance in the Canadian context.[15]

Work experience also affects earnings differently by recent immigrant and visible minority status. While white immigrants are slightly penalized for their work experience, visible minority immigrants face greater discounting of their experience. This is similar to the findings of Aydemir and Skuterud (2005).

The fact that visible minority recent immigrants benefit less from unionization than their white counterparts may indicate that non-European new arrivals are entering Canadian unions in the very lowest-paying occupations and positions. Unionized white immigrants, on the other hand, may be working in areas where the union premium is more significant.

Canadian employers seem to be more accepting of non-English or French speaking employees if they are of European origins. Non-European immigrants are highly penalized for having a non-official first language. This may be evidence of the greater linguistic distance between non-European languages and the official languages of Canada, or it may be evidence of racial discrimination, since language knowledge and accent of speech are often used as surrogates for racial discrimination in employment (Scassa, 1994).

With the growth of the “knowledge economy,” the demand for high skilled workers has increased dramatically in Canada. The aging of the Canadian population has amplified the reliance on immigrant workers to fill these high skilled jobs. If current immigration rates continue, it is estimated that immigration could account for nearly all labour force growth by 2011 (Statistics Canada, 2003). Therefore, the disadvantages that immigrants face in the labour market have repercussions not only for immigrants themselves, but also for Canadian society as a whole.

Many recent Canadian studies have analyzed cross-sectional data to examine the entry wages of immigrants and estimate the ability of immigrants to achieve the parity with comparable native-born workers. Very few studies, however, have utilized longitudinal data and techniques to directly compare the income growth of recent immigrant and native-born workers over time. As a first step, this study confirms that recent immigrants, particularly visible minorities, do indeed face great obstacles in the struggle to adjust and succeed. Since Canada relies on immigration to bring in new talent and maintain population levels, the finding that new immigrants do not consistently experience a period of “catch-up” early on in their careers is of concern. The racialization of this disadvantage is particularly worrisome and has important social implications for Canada as a host society.

Parties annexes

Note biographique

Rupa Banerjee

Rupa Banerjee is Assistant Professor at the Ted Rogers School of Business Management of the Ryerson University, Toronto, Ontario.

Notes

-

[1]

Some self-employment income may have been reported as investment income and therefore not included in the dependent variable.

-

[2]

The formula for calculating constant dollars is: Constant dollars in terms of a target year = Current dollars of a given tax year x (CPI of that tax year/CPI of the year to which the earnings are to be indexed).

-

[3]

Since the majority of new immigrants in Canada are visible minorities, the measures of immigrant status and visible minority status may be collinear. In order to remedy this, the two measures are combined to create one set of dummy variables that takes into account both visible minority status and immigrant status.

-

[4]

There is significant evidence of earnings differences by specific visible minority group (e.g., Baker and Benjamin, 1997; Pendakur and Pendakur, 1998; Hum and Simpson, 1999). However, given the small sample size of visible minority recent immigrants in the SLID, analyses by separate visible minority groups are not conducted.

-

[5]

This variable is used as a proxy for official language proficiency since there is no question in the SLID specifically about this.

-

[6]

The non-significance of this interaction term may be related to the small size of the recent immigrant sample.

-

[7]

The analyses in this paper were also conducted using fixed effects regression, with similar results for many measures. However, given the numerous advantages offered by growth curve modeling, the fixed effects analyses are not presented. Instead, all models in this paper are estimated using growth curve modeling.

-

[8]

A model including the quadratic term for time was also estimated in order to examine nonlinearity in income growth, but was not found to have significant fixed effects after explanatory variables were added. Thus, the simplified linear form of the model is presented here.

-

[9]

All growth curve models in this study are conducted using SAS PROC MIXED, full maximum likelihood, after transforming the data into person-period format. Prior to conducting the growth curve analysis, empirical income growth plots and individuals’ OLS income trajectories were examined. For detailed information on how to conduct growth curve analyses, see Singer and Willett (2003); Raudenbush and Bryk (2002) and Judith Singer’s website <http://www.gse.harvard.edu/~faculty/singer/>.

-

[10]

If there is not significant between person heterogeneity in growth, then growth curve analysis becomes unnecessary and more traditional methods (i.e. OLS regression) can be utilized.

-

[11]

In addition, this reference group’s first language is English or French. They are unmarried, with no pre-school aged children and live in a medium sized city in Ontario.

-

[12]

An interaction term between recent immigrant and visible minority status and gender was also entered into the model, but was found to be insignificant, and was therefore removed.

-

[13]

This simplification is utilized by Miech, Eaton and Liang (2003) in their analysis of occupational mobility using growth curve modeling.

-

[14]

For example, the Hum and Simpson (2000) study did not focus on recent immigrants, and instead looked at all immigrants, regardless of time in Canada. Secondly, they examined the difference in earnings between 1993 and 1997. Therefore, only those who reported earnings in those two years were included in the study. In the present study, one of the advantages of utilizing growth curve modeling is that I am able to include all respondents who reported at least two years of earnings.

-

[15]

University education is also discounted for all recent immigrants, but there is little racial difference in this discounting.

Bibliography

- Aydemir, A., and M. Skuterud. 2005. “Explaining the Deteriorating Entry Earnings of Canada’s Immigration Cohorts: 1966–2000.” Canadian Journal of Economics, 38 (2), 641–671.

- Aydemir, A., and C. Robinson. 2006. “Return and Onward Migration among Working Age Men.” Analytical Studies Branch Working Paper 273. Ottawa, ON: Statistics Canada.

- Baker, M., and D. Benjamin. 1994. “The Performance of Immigrants in the Canadian Labour Market.” Journal of Labor Economics, 12 (3), 369–405.

- Baker, M., and D. Benjamin. 1997. “Ethnicity, Foreign Birth and Earnings: A Canada/U.S. Comparison.” Transition and Structural Change in the North American Labour Market. M.G. Abbott, C.M. Beach and R.P. Chaykowski, eds. Kingston, ON: John Deutsch Institute and Industrial Relations Centre, Queen’s University, 281–313.

- Beach, C.M., and C. Worswick. 1993. “Is There a Double Negative Effect on the Earnings of Immigrant Women?” Canadian Public Policy, 19 (1), 36–53.

- Bloom, D.E., and M. Gunderson. 1991. “An Analysis of the Earnings of Canadian Immigrants.” Immigration, Trade and the Labor Market. J. Abowd and R. Freeman, eds. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press for the National Bureau of Economic Research, 321–342.

- Bloom, D.E., G. Grenier and M. Gunderson. 1995. “The Changing Labour Market Position of Canadian Immigrants.” Canadian Journal of Economics, 28 (4), 987–1005.

- Borjas, G.J. 1985. “Integration, Changes in Cohort Quality, and the Earnings of Immigrants.” Journal of Labor Economics, 3 (4), 463–489.

- Borjas, G.J. 1994. “The Economics of Immigration.” Journal of Economic Literature, 32 (4), 1667–1717.

- Borjas, G.J., and B. Bratsberg. 1996. “Who Leaves? The Outmigration of the Foreign Born.” The Review of Economics and Statistics, 78 (1), 165–176.

- Bratsberg, B., and J.F. Ragan Jr. 2002. “The Impact of Host-Country Schooling on Earnings: A Study of Male Immigrants in the United States.” The Journal of Human Resources, 37 (1), 63–105.

- Chiswick, B.R., and P.W. Miller. 1994. “The Determinants of Post-Immigration Investments in Education.” Economics of Education Review, 13, 163–177.

- Chiswick, B.R., and P.W. Miller. 1995. “The Endogeneity between Language and Earnings: International Analysis.” Journal of Labor Economics, 13 (2), 246–288.

- Chiswick, B.R., and P.W. Miller. 2001. “A Model of Destination-Language Acquisition: Application to Male Immigrants in Canada.” Demography, 38 (3), 391–409.

- Chiswick, B.R., and P.W. Miller. 2007. “The International Transferability of Immigrants’ Human Capital Skills.” IZA Discussion Paper No. 2670. Bonn, Germany: Institute for the Study of Labor.

- Creese, G., and E.N. Kambere. 2003. “What Colour is Your English?” Canadian Review of Sociology and Anthropology, 40 (5), 565–573.

- DeVoretz, D.J., J. Ma and K. Zhang. 2003. “Triangular Human Capital Flows: Empirical Evidence from Hong Kong and Canada.” Host Societies and the Reception of Immigrants. J.G. Reitz, ed. La Jolla, CA: Centre for Comparative Immigration Studies, University of California, San Diego, 469–492.

- Duleep, H.O., and M.C. Regets. 1999. “Immigrants and Human Capital Investment.” American Economic Review, 89 (2), 186–191.

- Esses, V. M., J. Dietz and A. Bhardwaj. 2006. “The Role of Prejudice in the Discounting of Immigrant Skills.” The Cultural Psychology of Immigrants. R. Mahalingam, ed. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum, 113–130.

- Fan, X. 2003. “Power of Latent Growth Modeling for Detecting Group Differences in Linear Growth Trajectory Parameters.” Structural Equation Modeling, 10 (3), 380–400.

- Frenette, M., and R. Morissette. 2003. “Will They Ever Converge? Earnings of Immigrant and Canadian-born Workers over the Last Two Decades.” Analytical Studies Branch Research Paper 215. Ottawa, ON: Statistics Canada.

- Friedberg, R.M. 2000. “You Can’t Take It with You? Immigrant Assimilation and the Portability of Human Capital.” Journal of Labour Economics, 18 (2), 221–251.

- Groot, W., and H. Maassen van den Brink. 2000. “Overeducation in the Labor Market: A Meta-Analysis.” Economics of Education Review, 19 (2), 158–179.

- Henry, F., and E. Ginsberg. 1985. Who Gets the Work? A Test of Racial Discrimination in Employment. Toronto, ON: The Urban Alliance on Race Relations and the Social Planning Council of Metropolitan Toronto.

- Hum, D., and W. Simpson. 1999. “Wage Opportunities for Visible Minorities in Canada.” Canadian Public Policy, 25 (3), 379–394.

- Hum, D., and W. Simpson. 2000. “Closing the Wage Gap: Economic Integration of Canadian Immigrants Reconsidered.” Journal of International Migration and Integration, 1 (4), 427–441.

- Li, P.S. 2001. “The Market Worth of Immigrant’ Educational Credentials.” Canadian Public Policy, 27 (1), 23–38.

- Li, P.S. 2003. “Initial Earnings and Catch-Up Capacity of Immigrants.” Canadian Public Policy, 29 (3), 319–337.

- Maume, D.J. Jr. 1999. “Glass Ceilings and Glass Escalators: Occupational Segregation and Race and Sex Differences in Managerial Promotions.” Work and Occupations, 26, 483–509.

- Meng, R. 1987. “The Earnings of Canadian Immigrant and Native Born Males.” Applied Economics, 19, 1107–1119.

- Miech, R.A., W. Eaton and K. Liang. 2003. “Occupational Stratification over the Life Course.” Work and Occupations, 30 (4), 440–473.

- Pendakur, K., and R. Pendakur. 1998. “The Colour of Money: Earnings Differentials among Ethnic Groups in Canada.” Canadian Journal of Economics, 31 (3), 518–548.

- Raudenbush, S.W., and A.S. Bryk. 2002. Hierarchical Linear Models: Applications and Data Analysis Methods. 2nd edition. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

- Reitz, J.G. 2001. “Immigrant Skill Utilization in the Canadian Labour Market: Implications of Human Capital Research.” Journal of International Migration and Integration, 2 (3), 347–378.

- Reitz, J.G. 2003. “Educational Expansion and the Employment Success of Immigrants in the United States and Canada, 1970–1990.” Host Societies and the Reception of Immigrants. J.G. Reitz, ed. La Jolla, CA: Centre for Comparative Immigration Studies, University of California, San Diego, 151–180.

- Scassa, T. 1994. “Language Standards, Ethnicity and Discrimination.” Canadian Ethnic Studies, 26 (3), 105–121.

- Singer, J.D., and J.B. Willett. 2003. Applied Longitudinal Data Analysis: Modeling Change and Event Occurrence. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Statistics Canada. 2003. 2001 Census: Analysis Series: The Changing Profile of Canada’s Labour Force. Ottawa, ON: Minister of Industry.

- Statistics Canada. 2004. SLID Definitions, Data Sources and Methods. Ottawa, ON: Statistics Canada. Retrieved on April 12, 2005 from Statistics Canada Website: www.statcan.ca/cgbin/imdb/p2SV.pl?Function=getSurvey&DDS 3889&Ing=en&db=IMDB&dbg=f&adm=&&dis=2

- Sweetman, A. 2004. “Immigrant Source Country School Quality and Canadian Labour Market Outcomes.” Analytical Studies Branch Research Paper 234. Ottawa, ON: Statistic Canada.

- Swidinsky, P., and M. Swidinsky. 2002. “The Relative Earnings of Visible Minorities in Canada: New Evidence from the 1996 Census.” Relations industrielles/Industrial Relations, 57 (4), 630–660.

Liste des figures

Figure 1

Predicted income growth of Visible Minority recent immigrants, White recent immigrantsand Native-born Whites, 1999-2004

Liste des tableaux

Table 1

Selected Descriptive Statistics for Visible Minority Immigrants, White Immigrants and White Native Born Canadians, 1999 and 2004

|

1999 |

2004 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Visible Minority Recent Immigrant |

White Recent Immigrant |

White Native Born |

Visible Minority Recent Immigrant |

White Recent Immigrant |

White Native Born |

|

N = 197 |

N = 119 |

N = 10,954 |

N = 197 |

N = 119 |

N = 10,954 |

Annual Income |

$28,372 |

$29,208 |

$36,466 |

$33,249 |

$41,640 |

$41,849 |

Age |

35.6 |

35.9 |

37.7 |

40.6 |

40.9 |

42.7 |

Female |

44.7% |

34.1% |

48.0% |

44.7% |

34.1% |

48.0% |

Years of Work Experience |

9.5 |

9.9 |

14.7 |

14.3 |

14.9 |

19.7 |

Unionized |

13.2% |

26.2% |

35.9% |

20.2% |

34.1% |

37.2% |

High School or Less Education |

49.7% |

35.6% |

47.6% |

38.9% |

23.1% |

39.9% |

College Education |

18.0% |

36.1% |

32.9% |

23.9% |

46.8% |

36.9% |

University Education |

32.3% |

28.4% |

19.5% |

37.2% |

30.1% |

23.2% |

Married |

68.6% |

70.6% |

65.3% |

73.9% |

74.0% |

68.4% |

Pre-school Children |

34.5% |

24.8% |

26.3% |

30.0% |

25.2% |

20.7% |

Annual Hours Worked |

1528.5 |

1645.6 |

1731.7 |

1692.0 |

1926.7 |

1794.6 |

Number of Jobs Held |

1.07 |

1.11 |

1.15 |

1.06 |

1.16 |

1.14 |

Non-Official 1st Language |

90.6% |

66.1% |

4.5% |

90.6% |

66.1% |

4.5% |

Years since Migration |

5.2 |

5.5 |

- |

10.2 |

10.5 |

- |

Table 2