Résumés

Abstract

Employee voice in China remains an under-researched topic from an industrial relations perspective. We investigated the relationship between family dependents (children and elderly) and migrant worker silence, with town-fellow organizations as a moderator, based on the data of the 2014 Guangdong Migrant Workers Survey. The findings reveal that migrant workers with dependent children are more likely to keep silent when their labour rights and interests are violated at the workplace, while family responsibilities for dependent elderly family members do not have significant impacts on migrant workers’ silence. In addition, town-fellow organizations weaken the association between family responsibilities for elderly dependents and silence. Our study contributes to the existing literature on employee voice and provides evidence on the role of town-fellow organizations in China as an informal, emerging institutional actor that regulates labour relations through their involvement in dispute resolution.

Keywords:

- employee silence,

- family dependents,

- informal institutional actor,

- migrant workers,

- town-fellow organization

Résumé

Objectif de recherche et questions – La voix de l’employé en Chine demeure un thème peu étudié du point de vue des relations industrielles, surtout à l’égard des travailleurs venus de la campagne. Ces derniers, qui constituent le segment le plus important de la population active, ont peu de moyens efficaces pour faire entendre leur voix. À ce jour, pour expliquer le silence de l’employé dont les droits du travail ont été violés, on a accordé trop peu d’attention au rôle des responsabilités familiales. On a également trop peu examiné le rôle modérateur des acteurs institutionnels informels, comme les organisations de migrants venus de la même ville, qui permettent au travailleur migrant lésé d’exprimer ses revendications.

La présente étude a pour but de combler ces lacunes en répondant à deux questions: (1) Le travailleur migrant sera-t-il plus enclin à garder le silence s’il a des enfants ou des aînés à sa charge? (2) De quelle manière l’organisation de migrants venus de la même ville influence-t-elle le lien entre le fait d’avoir des personnes à charge et le choix de se taire?

Méthodologie – Il s’agit d’une étude empirique de la relation entre les personnes à charge (enfants et aînés) et le silence du travailleur migrant, ainsi que le rôle modérateur de l’organisation de migrants venus de la même ville. Les données proviennent d’une enquête sur des travailleurs migrants (n = 776) vivant dans la province de Guangdong, dans le sud de la Chine.

Résultats – 1) Si un travailleur migrant a des membres de famille à sa charge, ce fait influencera sa voix lorsque ses droits auront été violés. 2) Dans cette éventualité, il est plus enclin à se taire pour le bien de ses enfants que pour celui de ses aînés. 3) Quant à l’organisation de migrants venus de la même ville, elle affaiblit la relation entre le fait d’avoir des aînés à charge et le choix de garder le silence.

Contributions – 1) Ces résultats enrichissent les connaissances actuelles sur la voix du travailleur migrant en Chine, surtout celui ayant des responsabilités familiales. 2) Nous avons démontré que l’organisation de migrants venus de la même ville joue un rôle institutionnel qui est informel mais néanmoins important, soit celui de représenter les travailleurs migrants dont les droits du travail ont été violés.

Mots clés:

- silence de l’employé,

- membres de famille à charge,

- acteur institutionnel informel,

- travailleurs migrants,

- organisation de migrants venus de la même ville

Corps de l’article

Introduction

Research on employee voice in China remains limited, despite increasing momentum since the mid-2010s (c.f. Huang et al., 2016a, for a review). To date, most studies, particularly those of recent years, have been conducted from an organizational behaviour (OB) perspective, with employees in large organizations as the main research targets. Leadership style has been viewed as a key antecedent for employee voice and silence (e.g., Duan et al., 2018; Lam and Xu, 2019; Li and Sun, 2015; Zhang et al., 2015).[1] By contrast, few studies of voice behaviour have been conducted from an industrial relations (IR) perspective (e.g., Huang et al., 2016b; Yang, 2020) with rural-to-urban migrant workers as the main study population. Such migrants are nonetheless the largest segment of the workforce in urban areas, with the vast majority being employed on poor terms and conditions (Chan, 2010; Cooke and Brown, 2015; see also Frenkel and Yu, 2015).

Migrant workers are registered as rural residents but have migrated to urban areas and are employed in the non-agricultural sector (An and Bramble, 2018). Since China adopted its economic reform and opening-up policy in 1978, millions of workers and their families have moved to cities, thus becoming the main force for urbanization and economic development (Li, 2017). Their rights and welfare are often infringed, as seen specifically in unduly low wages, delays in wage payment, overtime, lack of social insurance and employment contracts and safety and health problems (Cooke, 2011; Li and Li, 2010). Nonetheless, relatively few have taken action to protest such infringements, and many respond with silence to violations of their legally conferred rights (Halegua, 2008). According to China’s Social Psychology Research Report 2012-2013 (cited in Wang and Yang, 2013), sponsored by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences in 2013, only 14% of migrant workers sought help from the government and took action to protect their rights, whereas 60% responded to unfair treatment with silence or merely left their jobs. Even when migrant workers take action to seek remedy against non-compliant employers, the enforcement of legal decisions may be ineffective (Xie et al., 2017).

According to Aravopoulou et al. (2017), silence may be a reasonable response to a rights violation. Research by An and Bramble (2018) indicates that silence is a survival strategy for rural migrant workers in return for the opportunity to work, albeit with less social security coverage. Furthermore, workers may not be aware that their rights have been violated when employers have breached the labour law (Yang, 2020). Employee silence has inspired studies from an IR perspective (Barry and Wilkinson, 2016; Kaufman, 2015). To date, such research has focused on developed economies; hence, little is known about issues relating to employee silence in China, whose political, economic and cultural environments are significantly different from those of Western countries. Prior studies have shown that culture has consequential influences on the IR tradition (e.g., Chaney and Martin, 2013; Wallby, 2001). For example, Western culture emphasizes individuals and their rights and interests, whereas Chinese culture is more focused on the family, as Confucian moral values shape social relations and family interactions (Fan, 2007).

Some researchers have begun to investigate the role of family responsibilities in the employee’s decision to speak up or remain silent (e.g., An and Bramble, 2018; Gao and Shi, 2010). Not all family responsibilities are the same, a fact that may influence migrant workers’ voice behaviour, particularly in relation to children and elderly family members. Our study will address the research gap on the relationship between dependent family members and the silence of rural migrant workers.

Trade unions are usually regarded in IR research as the basic channel for employee voice (Benson and Brown, 2010). Most rural migrant workers are, however, in informal employment and at workplaces that are not unionized or are unionized but with only limited bargaining power (Cooke and Brown, 2015). China’s trade unions have acted unevenly in protecting workers’ rights, their action being contingent on the attitude of union officials, on the local working environment and on local opportunities and political resources (Chang and Cooke, 2018; Chen and Gallagher, 2018; Ghorbani et al., 2019).

At the same time, migrant workers from the same hometown often form a particular kind of informal community and self-organization, commonly known as town-fellow organizations (Tongxianghui). When migrant workers are deprived of their labour rights, they have an incentive to act together and speak with one voice. To some extent, this kind of organization functions like a trade union. Reliance on informal mechanisms, rather than on a formal procedure to redress grievances, is strengthened by China’s cultural tradition and legal environment. As Lubman (2000: 396) observed, “the use of guanxi (relationship) to influence outcomes is common” in China. Few, however, have studied the role of this important form of informal labour organization to promote employee voice to seek justice. The studies to date have suggested a significant role for power in the process of employees speaking up or remaining silent (An and Bramble, 2018). Power-dependence theory shows that the dependence of X on Y is determined by the power of Y over X (Emerson, 1962). The town-fellow organization may therefore play an important role in moderating the relationship between family responsibilities and employee silence because its membership may provide an employee with support and other resources for heavy family responsibilities, thus reducing the employee’s dependence on the employer and redressing the power imbalance between the two parties. There is still little empirical evidence on the moderating mechanisms of town-fellow organizations. Therefore, our study fills a second research gap by examining the role of the town-fellow organization as an emerging actor in regulating industrial relations, especially its potential moderating effect. In doing so, we extend existing knowledge on the role of emerging actors in IR, a topic that remains under-examined (Cooke and Wood, 2011; Heery and Frege, 2006), particularly in the Chinese context, where formal institutional actors still play an inadequate role in representing rural migrant workers and where external informal actors, such as labour non-governmental organizations (NGOs), still organize them within a politically confined space.

Using survey data on migrant workers (n = 776) from Guangdong province, southern China, our paper will address two research questions:

RQ1. Is silence among migrant workers increased if they have dependent family members who are children or elderly?

RQ2. How does the town-fellow organization moderate the linkage between family dependents and workers’silence?

Our conceptual model is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1

Conceptual Framework

Literature and Hypotheses

Caring for Elderly Parents in China: Cultural Values and Laws

Hu and Scott (2016) argue that the specific sociocultural context is key to understanding Chinese family values. The traditional Chinese family is embedded in a blood and patriarchal clan system (Feng, 2003). This kinship-based system has a strong influence on rural families in China, being upheld by family affection and emphasizing respect for seniority (Fei, 1983; Zhang, 2019). In Chinese culture, which is dominated by Confucian values, family is central and plays an important role in childcare; men assume major financial responsibility, and the dominant family relationship is that of ‘father and son’ (Zhao, 2007). Caring for elderly parents is based on a traditional ‘feedback’ model, that is, parents have an obligation to raise their underage children, and adult children have a reciprocal obligation to support their elderly parents. Ethical obligations thus flow in both directions. This reciprocal care is required by Confucianism and underlies the concept of filial piety (Fan, 2007; Fei, 1983). In China, filial piety is deeply rooted, and support from adult children is the most important form of care for the elderly. The more the children identify with the culture of filial piety, the more often they will give their parents various kinds of support (Chappell and Funk, 2012; Chou, 2011; Wei and Zhong, 2016).

This reciprocal care is especially dominant in China’s rural areas, due to the absence of a sound pension system for farmers. Rural pension programs began to be introduced by the central government in some counties only in 2009 and were expanded nationwide in 2011 with a low level of financial security (in 2017, monthly pension payments were only RMB70, about US$10); therefore, the rural elderly rely mainly on their children for support (Xinhua News, 2017). Tao (2016) pointed out that rural pension programs cannot fully protect the growing elderly population in rural areas. He asserted that the Chinese government should improve the problematic rural pension programs to meet the most basic needs and expenses of that population.

In line with the Confucian value of filial piety, China’s Constitution, Inheritance Law and Marriage Law clearly stipulate the responsibility and obligation of adult children to look after their dependent elderly parents. For instance, article 49 of the Constitution of the People’s Republic of China specifies that parents have a duty to support and educate their underage children and that adult children have a duty to support their dependent parents.

However, recent research has indicated structural changes in family values and behaviours, particularly in families of rural migrant workers. For example, Hu and Scott’s (2016) study found that higher education is associated with weaker traditional gendered and patrilineal values, while seeming to enhance moral beliefs of filial piety. Seo and Chung (2020) argued that the new generation of Chinese factory workers pay more attention to individual values and Western lifestyles. Chen et al. (2016) study of household structure and migration revealed that elderly members not only support the decisions of younger members to migrate but also care for the latter’s underage children in the three-generation household; in addition, sick rural parents do not discourage migration or entice migrant workers to return home to care for them. Liu’s (2014) study of ageing, migration and familial support in rural China further revealed that it is the collapse of interdependence and reciprocity networks through migration and family separation, rather than migration per se, that is causing the negative impact on the care of elderly family members left behind in the rural areas.

Responsibilities for Family Dependents, Migrant Workers’ Fear and Silence

Silence is defined as the withholding of possible significant input when you cannot express your thoughts and feelings (Morrison, 2014). As noted by Donaghey et al. (2011), an employee may choose silence either because there is no opportunity to speak up or for various other reasons. In addition, Van Dyne et al. (2003) contended that silence is a multidimensional concept that varies in terms of cues, attributions and consequences for employees.

Previous studies have investigated multiple motives for silence (Milliken et al., 2003), with fear being an important one (Kish-Gephart et al., 2009). Morrison and Milliken (2000) believe that employees withhold their suggestions and concerns for fear of negative repercussions. The concept of employee voice is thus underappreciated in the literature. On the basis of employee motive, Van Dyne et al. (2003) propose three types of silence: acquiescent silence, defensive silence and prosocial silence. Defensive silence is a form of self-protection based on fear. Kish-Gephart et al. (2009) further differentiate defensive silence into three types of fear-based silence according to the intensity (low-high) of fear and the response time (short-long).

IR research helps explain the institutional arrangements for workers’ silence (Nechanska et al., 2020). In the Chinese context, employee silence is explained to a large extent by institutional factors, namely the household registration (hukou) system and the related disadvantages it brings to rural migrant workers in terms of the labour market and urban living. The hukou system is a household registration system that officially identifies an individual as a resident of a specific area and includes various identifying personal/demographic characteristics. Rural citizens have less social security coverage than do their urban counterparts because the rural population is less favoured under the two-tier system of China’s development strategy, although the government is making gradual efforts to reduce that inequality (Holdaway, 2018). For example, migrant workers have little access to a good urban education for their children, due to socio-economic inequality (Holdaway, 2018; Zhang, 2018). At the same time, healthcare for their elderly family members can be costly because of the low coverage ratio of medical insurance. These education and healthcare costs therefore take up a large part of the household budget of rural migrant workers when their dependent family members migrate with them. Given the limited resources and income of migrant workers, the legacy of the hukou policy increases the costs of safeguarding their rights.

Moreover, due to social discrimination and exclusion stemming from the hukou system in China, migrant workers live as ‘second-class citizens’ in urban areas (Xu et al., 2011). Migrant workers with family dependents may be more likely to remain silent when their labour rights and interests are violated, for fear of negative repercussions and out of a desire to protect themselves from potential threats. Specifically, there are two reasons. First, migrant workers with dependents have a greater need for a stable income because they have to pay for their family members, thus leaving themselves with little discretionary leeway in their spending decisions. Li and Li (2010) indicate that the priority of migrant workers who migrate to the cities is to make more money for their family. An and Bramble (2018) assert that migrant workers with child dependents are more concerned about protecting their children’s rights and thus more likely to tolerate unfair treatment in order to keep their jobs. Second, migrant workers with dependents are at a disadvantage in the job market and often encounter discrimination from employers. On average, migrant workers with dependent children and elderly family members are usually older than single or unmarried migrant workers (because marrying in one’s twenties is still the norm in rural China, except for those who are too poor to do so). Existing studies reveal that the age of job seekers is negatively related to job opportunities (Li, 2017). In addition, older migrant workers have fewer opportunities to sign a written employment contract, which is closely associated with social security benefits in urban areas (Wang and Chen, 2010). According to the National Monitoring Survey of Migrant Workers 2016 conducted by NBSC (2017), only 35.1% of migrant workers have signed a written contract with their employer. Based on the data of the China Urban Labour Survey, Gallagher et al. (2013) found that migrant workers younger than 30 are 8-12% more likely than older ones to sign a written contract. It seems that migrant workers with dependents are more likely to tolerate discrimination to keep a job.

In sum, the high costs of voice lead to employee silence (Willman et al., 2006). Family dependents aggravate the economic burden and survival pressure on migrant workers, who more greatly fear job loss and other material losses. Consequently, they are more likely to choose fear-driven silence. Thus, we propose the following hypotheses:

H1a: Migrant workers with responsibilities for dependent children are more likely to remain silent than those without children.

H1b: Migrant workers with responsibilities for elderly dependents are more likely to remain silent than those without elderly dependents.

Moderating Role of Town-Fellow Organizations

To date, the literature has suggested that migrant workers lack legitimate and effective ways to organize for better rights and have their grievances redressed (e.g., Cooke et al., 2016; Xu, 2013). Due to the inefficacy of the ACFTU in organizing and representing rural migrant workers, and the institutional restrictions on independent unions, non-governmental labour organizations have emerged as an informal institutional actor in mobilizing and protecting workers, who are mostly rural migrant workers (Chan, 2013; Xu, 2013). Some scholars have found that non-governmental organizations (NGOs), together with community-based labour, play an important role in protecting labour rights by substituting for the ACFTU and local governments (e.g., Cheng et al., 2010; Li and Liu, 2018).

A small number of studies (e.g., Chan, 2010; Zhang, 2001) drew our attention to self-organizing of migrant workers via their community of residence, such as migrant worker villages (Mingong Cun) in urban areas, and to the role of these self-organizing entities in negotiating with local authorities and business elites to protect and advance the interests of migrant workers. These entities draw together the production, social life and informal networks of migrant workers but have a transient existence, due to the high mobility of migrants and, more importantly, their institutional vulnerability (Zhang, 2001). Workers and worker organizers in these urban villages are migrants, their main strength being the solidarity underpinned by their kinship and shared place of origin. These self-organizing entities are often known as town-fellow organizations, though not all residents of the same Mingong Cun are from the same hometown, and town-fellow organizations may operate beyond/outside the Mingong Cun.

These organizations are informal social groups formed by migrant workers from the same hometown, being loosely organized and not registered with government agencies. The government thus cannot track their exact number. Based on a reporter’s investigation, there has been rapid growth in the number of such organizations in various places, especially in the Pearl River Delta region of Guangdong province, with its more developed private economy; the city of Shenzhen alone had more than 200 by the early 2010s (South China Daily, 2011). A town-fellow organization has two main goals: (1) promote communication among migrants from the same hometown; and (2) protect the legitimate rights and interests of migrant workers and provide all members with a sense of security. When rural migrant workers are deprived of their labour rights, they have an incentive to come together to speak up; thus, in some ways, this kind of organization acts like a labour organization in the absence of a trade union. For example, using data from a survey of Beijing, Guangzhou, Shijiazhuang and other cities, Lu (2010) found that 36.1% of the 449 respondents belonged to a town-fellow organization, with the same proportion belonging to a trade union. In disputes with their employer, migrant workers prefer to seek support from the town-fellow organization, rather than from the trade union. Similarly, in a study by Wang (2010), where 186 migrant workers were asked what they would do if underpaid or unpaid for their work, 56.5% of them replied that they would rely on a network and find town-fellow organization members to help them, whereas only 1.6% said they would turn to the union for help.

Previous studies suggest that power relationships play a significant role in the process of employees expressing either their voice or silence (An and Bramble, 2018). Morrison and Rothman (2009) argued that power asymmetry may also cause voice to be seen as risky. Based on the model proposed by Morrison (2014), perceived powerlessness is an important inhibitor of voice, which determines whether a voice opportunity will result in voice or silence. According to power-dependence theory (Emerson, 1962), the value and availability of resources from alternative sources will determine the dependence of one party on the other. Drawing on this theory, we propose that membership in a town-fellow organizations plays an important role in moderating the relationship between family responsibilities and employee silence by helping workers fulfill heavy family responsibilities through support and other assistance, thereby making them less dependent on their employers and changing the power imbalance between the two parties. For instance, Zhao (2003) asserted that social networks in rural hometowns can provide migrant workers with important assistance in finding jobs, accommodation and financial resources. Wu (2017: 379) found that migrant workers have developed a Laoxiang-based (i.e., fellow villager-based) strategy in response to domination by their urban co-workers. These Laoxiang communities (a kind of town-fellow organization) actively engage in three types of activities: “recruitment and training to monopolize occupational niches; strategically coordinating conflicts in the Laoxiang network; and offering materialistic favors to members” (Wu, 2017: 379). Similarly, Gan (2015) in a study of 574 rural migrant workers reported that those whose families have higher social capital are more likely to settle down for the long term in urban areas. Cheng (2011) found that 90% of migrants find jobs through other members of these networking groups.

Because town-fellow organizations operate with the support of workers from the same village or county, they enjoy solidarity and collective power when voice is expressed during disputes (Cheng, 2011). Unlike the ACFTU, these groups are informal, with no formal institutional rules/regulations and no enforcement mechanisms. Migrant workers join them to gain affective support and meet security needs (Lu, 2010). Such organizations therefore fill a representational void for rural migrant workers in times of need. As noted by An and Bramble (2018), silence is a form of self-protection when employees lack bargaining power. Thus, based on power-dependence theory, we propose that the association between family responsibilities and employee silence is weaker for those workers who are members of a town-fellow organization than for those who are not. In summary, we present the following hypotheses:

H2a: The positive relationship between responsibilities for dependent children and workers’ silence will be weaker for migrant workers who are members of town-fellow organizations than for those who are not.

H2b: The positive relationship between responsibilities for elderly dependents and employee silence will be weaker for migrant workers who are members of town-fellow organizations than for those who are not.

Methodology

Data

The data came from a survey of migrant workers conducted from October 2013 to August 2014. Our study is part of a larger study of employee voice and silence in the migrant worker population in China, in contrast to the focus of previous studies on socio-economic outcomes (Frenkel and Yu, 2015; Gao et al., 2012; Xie and Gough, 2011). We conducted the survey and data collection in two stages. First, we designed the questionnaire and pilot study. Using the research goals as a basis, the research team completed the first draft of the questionnaire in October 2013 and conducted interviews with migrant workers to elicit suggestions in December 2013. Then, the research team revised the questionnaire in line with responses to a pilot survey of 50 respondents in January 2014 and produced the final version, which consisted of 45 questions and 135 variables about individuals and their family, working conditions and living conditions. The second stage was the survey itself. It was conducted in the 12 cities of Guangdong province that attracted the most migrant workers. We calculated the sample size of the 12 cities from the population size of migrant workers in the Guangdong Statistical Yearbook, using the quota sampling method. The research team went first to locations where a large number of migrants live and work and randomly selected respondents for the survey. About 85% of the respondents were interviewed at home, about 70% at the workplace and less than 5% at bus stops and train stations. Before we began each interview, we told the respondent the survey was only for academic purposes and that private information would be strictly confidential. Each respondent received a small gift afterwards. The survey was conducted during February-August 2014. In total, 26 migrant workers declined to be interviewed, and 810 agreed. The response rate was 96.89%.

Some responses, however, were extreme and seemed counterintuitive, such as working more than 24 hours per day or 7 days per week. In addition, some of the handwritten responses were barely decipherable on the answer sheet. To address such concerns, we filtered out the responses that contained outliers, implausible results and missing data, leaving us with 766 valid responses for the empirical study.

Measurement and Descriptive Statistics

Dependent Variable: Employee Silence

Two continuous variables were created to depict employee silence. If your labour rights and interests are violated at the workplace, what will you do (1 = I will remain silent and take no action; 0 = I will take some action to protect my rights)? Multiple actions include: seeking help from the trade union, government, and legal system; negotiating with managers; strike; and so forth.

Independent Variables: Family Dependents

We created two continuous variables for family dependents: children (number of children under 16) and elderly (number of people over 60) in a family.

Moderating Variable: Town-Fellow Organizations

We used a binary variable to measure participation in a town-fellow organization (1 = I participate in a town-fellow organization; 0 = I do not participate in a town-fellow organization).

Control Variables

According to previous studies, personal characteristics may influence employee voice and silence. We chose several as control variables, including age, gender, education and marital status (Chan, 2010; Pai, 2013; Pringle, 2011). In addition, we looked at similar studies and controlled for enterprise characteristics, including trade union, ownership, industry and enterprise size (An and Bramble, 2018; Willman et al., 2006).

The characteristics of the migrant workers are presented in Table 1. In terms of personal characteristics, 62% of them were male, average age was 29.31 and 47% were married. Their level of education was generally not high: 41.42% had only been to high school. On average, each of them was caring for 0.95 elderly family member and 0.90 child. When their labour rights were violated, 10.1% of them said they would remain silent. The correlations among the variables are shown in Table 2.

Table 1

Summary Statistics

Table 2

Correlations of Variables

Results

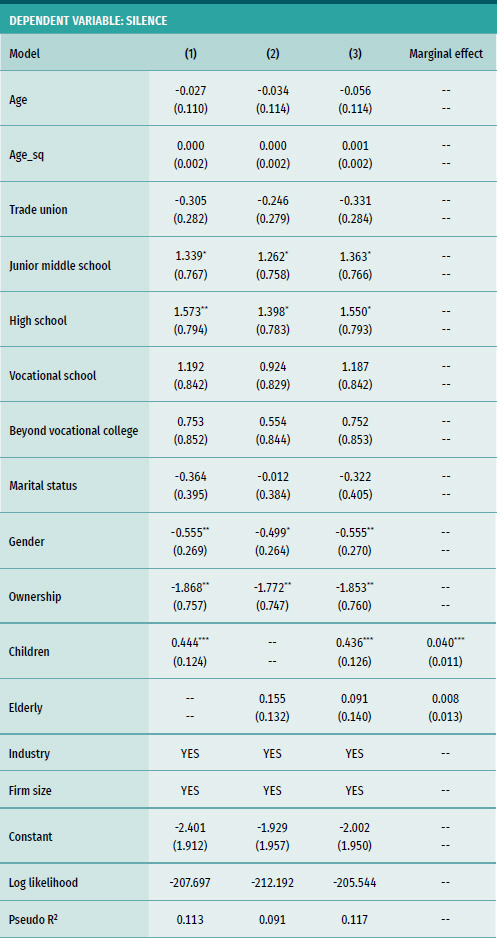

The logistic regression in Table 3 shows that children have a positively significant influence on employee silence (beta = 0.436, p < 0.01). In contrast, the coefficient for elderly dependents is 0.091 and insignificant. It seems, then, that children in a family, rather than elderly dependents, have a direct effect on employee silence. Thus, H1a is supported but not H1b. To explain the influence of children better, we analyzed the marginal effect in column 4, finding that the potential for employee silence increases by 4.0% for each additional child in the family.

Table 3

Effects of Family Dependents on Workers’ Silence

Notes: ***, **, and * denote statistical significance at the 1%, 5% and 10% levels, respectively. YES means the variable is controlled for.

Results in Table 4 (see column 1) demonstrate that the town-fellow organizations moderate the relationship between elderly dependents and employee silence. The coefficient of the interaction term is -1.845 and significant at the 5% level, thus supporting Hypothesis 2b, and suggesting that such organizations weaken the association between family responsibilities and employee silence. In contrast, column 2 in Table 4 shows that town-fellow organizations did not moderate the relationship between dependent children and employee silence (beta = -0.992, p > 0.10). Thus, Hypothesis 2a is not supported.

Table 4

Moderating Effect of Town-Fellow Organizations

Notes: ***, **, and * denote statistical significance at the 1%, 5% and 10% levels, respectively. YES means the variable is controlled for.

To illustrate interaction effects with town-fellow organizations, we drew two separate lines to depict the relationship between elderly dependents and employee silence. Figure 2 shows that the slope of migrant workers who joined such organizations was significantly different from the slope of those who did not. Thus, Hypothesis 2b is supported.

Figure 2

Moderating Effect of Town-Fellow Organizations on Relationship between Family Dependents and Workers’ Silence

Discussion and Conclusions

The traditional Chinese family is embedded in a kinship-based clan culture, which has a strong influence on rural families in China (Feng, 2003; Zhang, 2019). That culture is evident in the town-fellow organization, a loosely formed and self-organizing urban association of rural migrant workers from the same region. It is a relatively new form of grassroots association that uses a bottom-up approach; as such, it deserves more in-depth investigation (Cooke, 2014). For these migrant workers, we examined the relationship between, on the one hand, their silence over violations of their labour rights and, on the other, their responsibilities for dependent children and elderly family members. We also examined the moderating role of town-fellow organizations in resolving labour disputes and giving voice to migrant workers. The results show that migrant workers with dependent children are more likely to keep silent when their labour rights are violated at the workplace, while those with elderly dependents are not more likely to keep silent. Town-fellow organizations have significant moderating effects on the relationship between responsibilities for elderly dependents and employee silence. Our study has research and practical implications, as well as limitations, which we will discuss below.

Contributions

Our study makes two contributions to the literature. First, it enriches existing knowledge of employee voice in the Chinese context, with a focus on the largest segment of the workforce, rural migrant workers, who do not have an effective voice mechanism, particularly those with responsibilities for family dependents. The empirical results show that responsibilities for children, but not for elderly family members, significantly increase the potential for employee silence when labour rights are violated. In other words, H1a is supported but not H1b. It is easy to understand the significant effect of children, because children as dependents increase the economic burden and survival pressure on migrant workers while fueling their fear of experiencing unemployment or material losses. Consequently, migrant workers are more likely to choose fear-driven silence. Surprisingly, responsibilities for dependent elderly parents have no significant influence on employee silence, a finding that seems to contradict the emphasis of traditional Chinese culture on filial piety and reciprocal care between elderly parents and their adult children.

One possible explanation would be that social changes and economic reforms have affected intergenerational relationships and the roles of migrant workers in their families. On the one hand, migration has significantly altered their sense of family responsibilitythrough the influence of the market economy and the pressures of urban employment and survival. Urban workplaces separate migrant workers from their rural hometowns and traditional communities. As traditional morality weakens, so does the moral imperative to care for one’s elderly family members and condemn other adult children who do not. There has thus been a decline in the level of care and emotional support for elderly parents. On the other hand, because migrant workers have limited resources and a status as inferior citizens in the city, their elderly parents are no longer purely dependents but also breadwinners and homemakers. Quah (2009) and Liu (2014) found that parents give their adult offspring more care and more financial and emotional support than they receive from them. Therefore, with weaker moral sanctions on adult offspring, and with their elderly family members still playing an altruistic role, the result is a decrease in survival pressure on migrant workers and, hence, a decrease in their fear of employers. Consequently, elderly dependents no longer exert a significant impact on fear-driven silence.

Our study makes a second contribution. It reveals the informal, but nonetheless important institutional role of town-fellow organizations in organizing migrant workers and representing them when labour rights are violated. Previous research has shown that informal (also known as emerging and non-traditional) institutional actors can play a beneficial role in supporting workers in various ways, specifically in labour disputes (e.g., Cooke and Brown, 2015; Heery and Frege, 2006; Michelson et al., 2008). Yet, particularly in the Chinese context, research is still lacking on informal institutional actors and their role in regulating IR in general and voice and labour disputes in particular. This is a major research lacuna, given the increasing importance of informal employment among rural migrant workers, whom the trade unions and other formal institutional actors have largely been unable to organize and represent effectively. Our study extends existing knowledge about a grassroots informal actor, i.e., the migrant worker community, as a source of support and mobilization in times of need for migrant workers. Unlike registered NGOs, which are external to the community of rural migrant workers and which operate in a politically precarious environment (Lee and Shen, 2011; Li and Liu, 2018), town-fellow organizations develop internally and organically within the community and stem from strong clan and family blood connections and bonds. As such, our findings on the influence of these organizations, as an alternative to trade unions or other formal institutional actors for employee voice, will enrich existing research on workers’ organizing and voice mechanisms. We also provide a new perspective on understanding of labour relations in the Chinese context. We note, however, that not all town-fellow organizations play a positive role; nor are they institutionally secure, though they are much more secure than some foreign NGOs, which must officially register to be able to operate in China.

The empirical results show that town-fellow organizations weaken the association between family responsibilities and workers’ silence. As predicted by power-dependence theory, these organizations provide workers with support and other resources to help them deal with heavy family responsibilities, thus making them less dependent on employers and altering the power imbalance between the two parties. In other words, the pressure to remain silent due to family responsibilities is relieved by assistance from town-fellow organizations. Interestingly, this moderating role only acts in the relationship between filial responsibilities for the elderly and silence by migrant workers in disputes with their employers. That is, H2b is supported but not H2a. The reason may be that elderly parents are better able than children to tap into sources of support from outside the family, including town-fellow organizations. Our research design did not allow us to substantiate this speculation by investigating the social activities of elderly parents. Future researchers could extend our study by examining the social resources available to elderly parents and how this source of support influences the voice and behaviour of their migrant children.

Practical Implications

Our study has several practical implications. First, there is a clear need for migrant workers to be represented and have their voice heard more effectively both outside and inside the workplace. ACFTU organizations may consider how they can work together with town-fellow organizations to develop effective representational mechanisms. Second, labour regulation should be enforced more effectively to strengthen the penalties for violations of labour rights, to improve protection of the rights of migrant workers and to increase the benefits for them of breaking their silence. Third, non-union organizations, such as town-fellow organizations, could play a more important role in employee voice by developing a formal relationship with local employers for both preventative and remedial actions. This suggestion could be acted upon by setting up town-fellow organization sub-groups within the enterprise of the workers. In enterprises where a trade union is recognized, these sub-groups could work with the union to develop better support for the workers. In enterprises where a union is absent, town-fellow organization sub-groups could provide workers with an alternative means to gain a voice. In fact, there are town-fellow organizations in some factories, sometimes several, due to the diverse hometown origins of the migrant workers, but these organizations are often small and led by young workers with limited resources and experience. To be more effective, they should come together to form a town-fellow organization for the local area, with a larger membership and more resources and organizing capacity. However, they should operate in a way that does not pose a political and institutional threat.

Limitations and Further Research

Our study has several limitations. First, the survey was done in Guangdong province, and its findings may not be generalizable to all migrant workers in China. Second, our study is a quantitative and cross-sectional one with single source data. Future researchers may use multiple source data, including, for example, interviews with leaders of town-fellow organizations and with elderly parents of migrant workers. This kind of qualitative data would provide more insight into the challenges, workings and dynamics of such organizations, as well as their ability to advance workers’ rights and interests. It may also explain why migrant workers with elderly parents are more likely to turn to town-fellow organizations to seek help when their labour rights are violated.

Parties annexes

Acknowledgements

The research for this article was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (71803032, 71703018, 72073087), and National Social Science Fund on Key Research (15ZDA013).

Note

-

[1]

This study use the terms ‘employee silence’ and ‘workers’ silence’. We use the former when referring to extant literature or when making a general discussion. We use ‘workers’ silence’ when referring to rural migrants, especially in our study, because many of them do not have a formal employment status, hence are not ‘employees’ in the legal sense. This makes them more vulnerable without access to institutional voice mechanism, thus relying on informal institutional actors such as town-fellow organizations for support.

References

- An, Fansuo and Tom Bramble (2018) “Silence as a Survival Strategy: Will the Silent be Worse Off? A Study of Chinese Migrant Workers in Guangdong.” International Journal of Human Resource Management, 29 (5), 1-26.

- Aravopoulou, Eleni, Fotios V. Mitsakis and Charles Malone (2017) “A Critical Review of the Exit-Voice-Loyalty-Neglect Literature: Limitations, Key Challenges and Directions for Future Research.” International Journal of Management, 6 (3), 1-10.

- Barry, Michael and Adrian Wilkinson (2016) “Pro-social or Pro-management? A Critique of the Conception of Employee Voice as a Pro-social Behaviour within Organizational Behaviour.” British Journal of Industrial Relations, 54 (2), 261-284.

- Benson, John and Michelle Brown (2010) “Employee Voice: Does Union Membership Matter?” Human Resource Management Journal, 20 (1), 80-99.

- Chan, Chi (2010) The Challenge of Labour in China: Strikes and the Changing Labour Regime in Global Factories. New York: Routledge.

- Chan, Chris King (2013) “Community-based Organizations for Migrant Workers’ Rights: The Emergence of Labour NGOs in China.” Community Development Journal, 48 (1), 6-22.

- Chaney, Lillian and Jeanette Martin (2013) Intercultural Business Communication, 6th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall.

- Chang,Cheng and Fang Lee Cooke (2018) “Layers of Union Organisation and Representation: A Case Study of a Strike in a Japanese-funded Auto Plant in China.” Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 56 (4), 492-517.

- Chappell,Neena L. and Laura Funk (2012) “Filial Responsibility: Does it Matter for Care-giving Behaviours?” Ageing & Society, 32 (7), 1128-1146.

- Chen, Fengbo, Henry Lucas, Gerry Bloom and Shijun Ding (2016) “Household Structure, Left-behind Elderly, and Rural Migration in China.” Journal of Agricultural and Applied Economics, 48 (3), 279-297.

- Chen, Patricia and Mary Gallagher (2018) “Mobilization without Movement: How the Chinese State ‘Fixed’ Labor Insurgency.” Industrial & Labor Relations Review, 71 (5), 1029-1052.

- Cheng, Joseph Yu-shek, King-lun Ngok and Huang Yan (2010) “Multinational Corporations, Global Civil Society and Chinese Labour: Workers’ Solidarity in China in the Era of Globalization.” Economic and Industrial Democracy, 33 (3), 379-401.

- Cheng, Yijian (2011) “An Empirical Study of Migrant Workers’ Attitude toward Townsfolk Organizations.” Journal of Agriculture Science of Guangdong, 38 (14), 189-192. [in Chinese]

- Chou, Rita Jing-Ann (2011) “Filial Piety by Contract? The Emergence, Implementation, and Implications of the ‘Family Support Agreement’ in China.” Gerontologist, 51 (1), 3-16.

- Cooke, Fand Lee and Geoffrey Wood (2011) “New Actors and Employment Relations in Emerging Economies.” Relations Industrielles/Industrial Relations, 66 (1), 7-10.

- Cooke, Fang Lee (2011) “Labour Market Regulations and Informal Employment in China: To What Extent are Workers Protected?” Journal of Chinese Human Resource Management, 2 (2), 100-116.

- Cooke, Fang Lee (2014) “Chinese industrial relations research: In search of a broader analytical framework and representation.” Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 31, 875–898.

- Cooke, Fang Lee and Ronald Brown (2015) “The Regulation of Non-standard Forms of Work in China, Japan and Republic of Korea.” International Labour Organization Working Paper, Conditions of Work and Employment Series No.64.

- Cooke, Fang Lee, Yunhua Xie and Duan Huimin (2016) “Workers’ Grievances and Resolution Mechanisms in Chinese Manufacturing Firms: Key Characteristics and the Influence of Contextual Factors.” International Journal of Human Resource Management, 27 (18), 2119-2141.

- Donaghey, Jimmy, Niall Cullinane, Tony Dundon and Adrian J. Wilkinson (2011). “Reconceptualising Employee Silence: Problems and Prognosis.” Work, Employment & Society, 25(1), 51-67.

- Duan, Jinyun, Chanzi Bao, Caiyun Huang and Chad Brinsfield (2018) “Authoritarian Leadership and Employee Silence in China.” Journal of Management & Organization, 24 (1), 62-80.

- Emerson, Richard M. (1962). “Power-Dependence Relations.” American Sociological Review, 27(1), 31-41.

- Fan, Ruiping (2007) “Which Care? Whose Responsibility? And why Family? A Confucian Account of Long-term Care for the Elderly.” Journal of Medicine and Philosophy, 32 (5), 495-517.

- Fei, Xiaotong (1983) “The Problem of Old Age Support in the Change of Family Structure: on the Change of Family Structure in China.” Journal of Peking University (Philosophy and Social Sciences), (3), 7-16. [in Chinese]

- Feng Erkang (2003) “On Contemporary Significance of Chinese Traditional Family Culture.” Jianghai Academic Journal, (6), 11-15. [in Chinese]

- Frenkel, Stephen and Chongxin Yu (2015) “Chinese Migrants’ Work Experience and City Identification: Challenging the Underclass Thesis.” Human Relations, 68 (2), 261-285.

- Gallagher, Mary Elizabeth, John Giles and Albert Park (2013) “China’s 2008 Labor Contract Law: Implementation and Implications for China’s Workers.” Human Relations, 68 (2), 197-235.

- Gan, Yu (2015) “Settlement Intension of Rural Migrants: Evidence from 574 Families.” Population & Economics, (3), 68-76. [in Chinese]

- Gao, Liping and Kan Shi (2010) “When Employees Face the Choice of Voice or Silence: The Moderating Role of Chinese Traditional Culture Values.” Proceedings 2010 IEEE 2nd Symposium on Web Society. Beijing, pp. 470-474.

- Gao, Qin, Sui Yang and Shi Li (2012) “Labor Contracts and Social Insurance Participation among Migrant Workers in China.” China Economic Review, 23 (4), 1195-1205.

- Ghorbani, Majid, Morley Gunderson and Byron Y.S. Lee (2019). Union and Communist Party Influences on the Environment in China. Relations Industrielles-Industrial Relations, 74(3), 552-576.

- Halegua, Aaron (2008) “Getting Paid: Processing the Labor Disputes of China’s Migrant Workers.” Berkeley Journal of International Law, 26 (1), 254–322.

- Heery, Edmund and Carola Frege (2006) “New Actors in Industrial Relations.” British Journal of Industrial Relations, 44 (4), 601-604.

- Holdaway, Jennifer (2018) “Educating the Children of Migrants in China and the United States: A Common Challenge?” China Population and Development Studies, 2, 108-128.

- Hu, Yang and Jacqueline Scott (2016) “Family and Gender Values in China: Generational, Geographic, and Gender Differences.” Journal of Family Issues, 37 (9), 1267-1293.

- Huang, Wei, Jingjing Weng and Ying-Che Hsieh (2016a) “The Hybrid Channel of Employees’ Voice in China in a Changing Context of Employment Relations.” Advances in Industrial and Labor Relations, 23, 19-43.

- Huang, Wei, Yuhui Li, Shuo Wang and Jingjing Weng (2016b) “Can ‘Democratic Management’ Improve Labour Relations in Market-driven China?” Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 54 (2), 230-257.

- Kaufman, Bruce E. (2015) “Theorising Determinants of Employee Voice: An Integrative Model Across Disciplines and Levels of Analysis.” Human Resource Management Journal, 25 (1), 19-40.

- Kish-Gephart, Jennifer J., James R. Detert, Linda K. Trevino and Amy C. Edmondson (2009). “Silenced by Fear: The Nature, Sources, and Consequences of Fear at Work.” Research in Organizational Behavior, 29, 163-193.

- Lam, Long W. and Angel Jie Xu. (2019) “Power Imbalance and Employee Silence: The Role of Abusive Leadership, Power Distance Orientation, and Perceived Organisational Politics.” Applied Psychology, 68 (3), 513-546.

- Lee, Ching Kwan and Yuan Shen (2011) “The Anti-solidarity Machine? Labor Nongovernmental Organizations in China.” In S Kuruvilla, CK Lee and M Gallagher (eds), From Iron Rice Bowl to Informalisation. Ithaca, NY: ILR Press, pp. 173–187.

- Li, Chunyun and Mingwei Liu (2018) “Overcoming Collective Action Problems Facing Chinese Workers: Lessons from Four Protests Against Walmart.” Industrial & Labor Relations Review, 71 (5), 1078–1105.

- Li, Mankui (2017) “Protection for Migrant Workers under Evolving Occupational Health and Safety Regimes in China.” Relations Industrielles-industrial Relations, 72(1), 56-76.

- Li, Peilin and Wei Li (2010) “A Survey of the Economic Conditions and Social Attitudes of Migrant Workers.” Social Science in China, (1), 119-131. [in Chinese]

- Li, Yan and Jian-Min Sun (2015) “Traditional Chinese Leadership and Employee Voice Behavior: A Cross-level Examination.” Leadership Quarterly, 26 (2), 172-189.

- Liu, Jieyu (2014) “Ageing, Migration and Familial Support in Rural China.” Geoforum, 51, 305-312.

- Lu, Guoxian (2010) “Study on the Organization of Migrant Workers and its Security Countermeasures.” Journal of People’s Public Security University of China, 26 (2), 8-13. [in Chinese]

- Lubman, Stanley (2000) “Bird in a Cage: Legal Reform in China after Twenty Years.” Northwestern Journal of International Law & Business, 20 (3), 383-424.

- Michelson, Grant, Suzanne Jamieson and John Burgess(eds) (2008) “New Employment Actors: Developments from Australia.” Oxford: Peter Lang.

- Milliken, Frances J., Elizabeth W. Morrison, and Patricia F. Hewlin (2003). “An Explanatory Study of Employee Silence: Issues that employees Don’t Communicate Upward and why.” Journal of Management Studies, 40(6), 1453–1476.

- Morrison, Elizabeth W. and Milliken, Frances J. (2000). “Organizational silence: A barrier to change and development in a pluralistic world.” Academy of Management Review, 25(4), 706–725.

- Morrison, Elizabeth W. and Rothman Naomi B. (2009). “Silence and the dynamics of power.” In Greenberg and Edwards (Eds), Voice and Silence in Organizations(pp. 175–202). Bingley: Emerald.

- Morrison, Elizabeth W. (2014) “Employee Voice and Silence.” Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 1:1, 173-197.

- National Bureau of Statistics of China (2017) “National Monitoring Survey of Migrant Workers 2016.” http://www.stats.gov.cn/Tjsj/zxfb/201704/t20170428_1489334.html, (March 21, 2020).

- Nechanska, Eva, Emma K. Hughes and Tony Dundon (2020). “Towards an Integration of Employee Voice and Silence.” Human Resource Management Review, 30(1), 100674.

- Pai, Hsiaohung and Gregor Benton (2013). Scattered Sand: The Story of China’s Rural Migrants. London: Verso.

- Pringle, Tim (2011). Trade Unions in China: The Challenge of Labor Unrest. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Quah, Stella R. (2009) Families in Asia: Home and Kin. second ed. Routledge: London.

- Seo, Yumi and Sun Wook Chung (2020). “Abusive Supervision, Psychological Capital, and Turnover Intention: Evidence from Factory Workers in China.” Relations Industrielles-industrial Relations, 74(2), 377-404.

- South China Daily (2011) “The Townsfolk Association Becomes the Rights Protection Association which Tests the Governing Wisdom.” http://epaper.southcn.com/nfdaily/html/2011-08/15/content_6998784.htm (August 15, 2011). [in Chinese]

- Tao, Jikun (2016) “Can China’s New Rural Social Pension Insurance Adequately Protect the Elderly in Times of Population Ageing?” Journal of Asian Public Policy, 10 (2), 158-166.

- Van Dyne, Linn, Soon Ang and Isabel C. Botero (2003). “Conceptualizing Employee Silence and Employee Voice as Multidimensional Constructs.” Journal of Management Studies, 40(6), 1359-1392.

- Wallby, Sylvia (2001) “From Community to Coalition: the Politics of Recognition as the Handmaiden of the Politics of Equality in an Era of Globalization.” Theory, Culture, Society, 1 (2-3), 113-135.

- Wang, Song (2010) “A Study on the Cognitive Dilemma of Migrant Workers on the Interest Expression Function of Trade Union.” Journal of Beijing Federation of Trade Unions Cadre College, 25 (1), 17-21. [in Chinese]

- Wang, Haining and Yuanyuan Chen (2010) “An Analysis on the Work Welfare Discrimination against Migrants.” Chinese Journal of Population Science, 2, 47-54. [in Chinese]

- Wang, Junxiu and Jiyin Yang (2013) “China’s Social Psychology Research Report 2012-2013.” Beijing: Social Sciences Academic Press. [in Chinese]

- Wei, Hongyao and Zhangbao Zhong (2016) “Intergenerational Exchange, Filial Culture and Structural Constraints: an Empirical Analysis of Children’s Support Behavior.” Journal of Nanjing Agricultural University (Social Sciences Edition), 16 (1), 144-155. [in Chinese]

- Willman, Paul, Alex Bryson and Rafael Gomez (2006). “The Sound of Silence: Which Employers Choose No Employee Voice and Why?” Socio-Economic Review, 4(2), 283-299.

- Wu, Tongyu (2017) “Laoxiang Network and Boundary Struggles: Urban Migrants’ Self-Organization in China’s New Workplaces.” Journal of Contemporary China, 27 (111), 379-392.

- Xie, Yu and Margaret Gough (2011) “Ethnic Enclaves and the Earnings of Immigrants.” Demography, 48 (4), 1293-1315.

- Xie, Pengxin, Fuxi Wang and Yanyuan Cheng (2017) “How did Chinese Migrant Workers Fare in Labour Dispute Mediation? Differentiated Legal Protection and the Moderating Role of the Nature of Dispute.” Journal of Industrial Relations, 59 (5), 611-630.

- Xinhua News (2017) “The Old People in Rural Areas Have Less Income and Weak Ability to Provide Themselves.” http://www.xinhuanet.com/201712/23/c_1122155345.htm, (March 21, 2020).

- Xu, Yi (2013) “Labour Non-governmental Organizations in China: Mobilizing Rural Migrant Workers.” Journal of Industrial Relations, 55 (2), 243-259.

- Xu, Qingwen, Xinping Guan and Fangfang Yao (2011) “Welfare Program Participation among Rural-to-urban Migrant Workers in China.” International Journal of Social Welfare, 20 (1), 10-21.

- Yang, Duanyi (2020) “Why don’t They Complain? The Social Determinants of Chinese Migrant Workers’ Grievance Behaviors.” ILR Review, 73 (2), 366-392.

- Zhang, Li (2001) Strangers in the City: Reconfigurations of Space, Power, and Social Networks within China’s Floating Population. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Zhang, Chuanchuan (2019) “Family Support or Social Support? The Role of Clan Culture.” Journal of Population Economics, 32, 529-549.

- Zhang, Yan, Ming-yun Huai and Yun-hui Xie (2015) “Paternalistic Leadership and Employee Voice in China: A Dual Process Model.” Leadership Quarterly, 26 (1), 25-36.

- Zhang, Zhanxin (2018) “Employment Marketization, Social Security Inclusion and Rights Equalization of Rural Migrants.” China Population and Development Studies, 2, 57-82.

- Zhao, Yaohui (2003) “The Role of Migrant Networks in Labor Migration: The Case of China.” Contemporary Economic Policy, 21 (4), 500-511.

- Zhao, Yanxia (2007) Father and Son in Confucianism and Christianity. Eastbourne: Sussex Academic Press.

Liste des figures

Figure 1

Conceptual Framework

Figure 2

Moderating Effect of Town-Fellow Organizations on Relationship between Family Dependents and Workers’ Silence

Liste des tableaux

Table 1

Summary Statistics

Table 2

Correlations of Variables

Table 3

Effects of Family Dependents on Workers’ Silence

Table 4

Moderating Effect of Town-Fellow Organizations

10.7202/1004778ar

10.7202/1004778ar