Résumés

Abstract

This article focuses on a secret study commissioned by the City of Calgary chief commissioner in 1973 to ascertain the extent and threat of monopoly control by a leading land developer in the city. Kept from City Council for months after its completion, the report, code named Apollo, found that the Genstar group of companies was in a strong monopoly position. When released, the report led to a public debate, political infighting at City Hall, threats of legal action by Genstar, and a federal investigation. Though its findings on monopoly implications were never substantiated, the report did indicate the growing concentration of corporate power in the land development and construction industries in Calgary, and likely in other Canadian cities as well.

Résumé

Cet article se concentre sur une étude secrète commandée par le commissaire en chef de la Ville de Calgary en 1973, qui avait pour but d’évaluer le risque d’un monopole par un de plus importants promoteurs immobiliers de la ville. Le rapport, nommé Apollo, fut tenu secret auprès du Conseil municipal et détermina que le groupe d’entreprises Genstar était un monopole majeur. Quand le rapport fut finalement rendu disponible, il s’en suivit une période de débats publics, de désagréments au Conseil municipal, de menaces d’actions judiciaires par Genstar, et à une enquête judiciaire fédéral. Malgré que les allégations d’un monopole ne fussent jamais justifiées, le rapport démontra tout de même la concentration accrue du pouvoir des entreprises dans le domaine du marché foncier et immobilier dans la région de Calgary et possiblement dans les autres villes canadiennes.

Corps de l’article

Real estate activity has been a vital factor in determining Calgary physical growth patterns. The arbitrary role of the Canadian Pacific Railroad in fixing the precise location of the downtown area and in defining the city’s first socio-economic residential patterns cannot be understated. During the city’s settlement boom between 1909 and 1914, speculators made fortunes selling land with easy access to railway lines and roads that never materialized. Calgary’s first home-grown land developers influenced urban growth in the 1950s by building and servicing subdivisions on the city’s periphery in close proximity to utility trunk lines. By the 1970s the focus had changed yet again. Amid rising land prices and the promise of high profits in the housing industry, the land development business had changed from one characterized by small builder-developers to large-scale enterprises with deep pockets. When city planners in the early 1970s began favouring corridor growth rather than expansion on wide fronts, these corporations began assembling land along these corridors just beyond the corporate limits.

In terms of land development, Calgary was somewhat of a maverick compared to other Canadian cities. Wanting to avoid further fringe communities like those that had arisen just outside the city limits during the 1909–14 land boom, civic administrators adopted what they called “the unicity.” This concept called for large-scale annexations well in excess of that required for short-term growth. Endorsed by the McNally Royal Commission on the Metropolitan Growth of Edmonton and Calgary (1956), the unicity became an article of faith guiding annexation policy for the next fifty years. Civic administrators also hoped that ample land within the corporate boundaries would dissuade peripheral land development. However, since developers usually controlled land under options to purchase, they could afford to acquire peripheral land and play a waiting game. Project Apollo was one city administrator’s response to this perceived threat.

Like many Canadian cities, Calgary operated on a commission form of government. Appointed by City Council to whom they reported, Calgary’s four commissioners held wide executive powers in managing the city’s various departments. Following reorganization in 1968, the elected mayor ceased to chair the Board of Commissioners and became instead an ex officio member. This restructuring enhanced the power of the chief commissioner, whose mandate included the important law and the planning departments. Also important for the purposes of this discussion was the fact that, although expenditures by commissioners were generally subject to Council approval, the chief commissioner had access to a contingency fund that could be used at his discretion.

In early 1973, Chief Commissioner George Hamilton used his contingency fund to commission a secret study of the city’s leading construction and land development company. His aim was to assess the extent of the corporation’s land holdings and further to ascertain whether it had secured monopoly control of housing construction in the city. The study, code-named Apollo, was conducted by two local companies and took final form in a report presented to Hamilton in late 1973. Though any force the report might have had was eroded by petty politics, the Genstar Report remained a controversial document. First it raised questions about monopolistic practices in land development and challenged the legitimacy of house prices in the city. Second, by casting Genstar and similar companies in an unfavourable light, the report damaged the reputation of the land development industry in the city. Arguably, this public suspicion of the land developer would have surfaced, regardless. Nevertheless, it was the Genstar Report that gave first public knowledge of a disturbing trend in the city itself, and likely, by implication, in other major Canadian urban centres.

The role of the land developers in influencing urban growth in Canada has received little academic attention. Susan Goldenburg’s Men of Property: The Canadian Developers Who Are Buying America (1981) offers some excellent information on major developers including Carma and Genstar, and, being written at the height of their prosperity, is also a testimonial to an emerging corporate force.[1] Probably the best treatment of the land development industry in Canada is by Peter Spurr in Land and Urban Development: A Preliminary Study (1976).[2] Using a wealth of tabular statistics and facts, Spurr discussed the concept of land as a commodity, and demonstrated that monopolies by major land development companies were present in Canadian cities by the mid 1970s. The only real attempts to discuss land developers and their relations with urban governments in any detail are by James Lorimer and other like-minded writers from City Magazine. Three books comprise the corpus of what amounted to a scathing critique of developer dominance in the land assembly business and housing industry, a process enabled by collusive or hapless local governments.[3] Interestingly, in support of their arguments, Lorimer et al. singled out the Genstar Report for special discussion. However, as a result of their clear biases and lack of balanced analysis, these studies fall short on credibility grounds. As for the Genstar Report itself, it was withdrawn from public scrutiny in 1975 and for decades afterwards held a “Restricted” classification in the City of Calgary archives.[4]

Mirroring that of other Canadian cities, Calgary’s residential growth accelerated in the 1950s and continued largely unrepressed into the new millennium. Characterized by single family dwellings, the pattern of suburbanization was enabled by substantial annexations between 1956 and 1964 that swelled the city’s area from 40 to 150 four square miles. New housing construction was controlled by local businessmen. Well into the 1960s, house prices remained stable. In the light of the generally positive dialogue between the City and the Urban Development Institute (the development industry’s official spokesman), the period 1954–66 represented—certainly in the developers’ eyes—the halcyon days of residential construction in Calgary.

Two factors conspired to bring an end to this quiescent period of locally controlled urban housing development in the city. The first concerned the dramatic rise in house prices that began around 1967 and by 1971 had become a major civic issue. A modest bungalow in an average suburb that cost $12,000 in 1960 was worth over $20,000 a decade later. Monthly payments on new mortgages had doubled while the income necessary to secure one had risen almost 70 per cent. While increased construction and servicing costs were the main culprits pushing house prices up, it was the faster rising land values that captured media and public attention. They had increased by over 100 per cent in the 1960s compared to about 70 per cent for construction costs.

The developers equated these rising land prices with lot shortages. They felt that civic policies were holding large tracts of developable land off the market, and claimed that studies on transportation issues, utilities feasibility, potential park space, or airport regulations had removed the potential for building thousands of houses in the city. Their solution was simple. Arguing that housing prices were a reflection of the costs of land, which in turn were determined by its availability, the developers pressed for expansion of the city’s corporate boundaries.[5] In 1972 Commissioner Denis Cole noted that the City was being influenced to make large areas serviceable in the belief that the only way to keep the price of serviced lots down was to increase the supply of land.[6]

By the middle of 1972 the City found itself in a difficult position. The developers’ argument about lot shortages was given more credence following the City’s decision to freeze the development of 2,500 acres of land on Nose Hill pending further study. A similar situation was unfolding in the south, where development of the Fish Creek valley was being forestalled by mounting opposition favouring a park over houses. The City’s response was predictable. In July 1972 an Interim Annexation Policy was implemented as a precursor to a long-range comprehensive policy. Though a new policy advocating the annexation of 125 square miles was not announced until early 1974, there can be little doubt that its foundations dated to the Interim Annexation Policy of 1972. Given the unicity concept, Hamilton’s desire to know about land holdings on the city’s periphery along the approved growth corridors was understandable.

The second reason precipitating changing attitudes towards residential development in the city was related to the land development industry itself. Though several outside developers operated in the city, including the Winnipeg-based Quality Construction (Qualico), the bulk of the city’s houses were being built by two companies, both of which were extensions of the local construction industry. The Kelwood Corporation, formed in late 1953 by five members of the construction industry, concentrated in areas south of the Bow River. By 1957 the consortium was building around 40 per cent of new homes in the city. In response to an increasing demand for houses in the north and indeed to Kelwood’s market domination, the second of Calgary’s homegrown developer companies was born in 1958.[7] Carma Developers comprised forty-three members of the Calgary House Builders Association who contributed $250,000 to launch the company. Carma was a unique organization based on the co-operative principle with its sole aim to acquire tracts of land and then distribute the subdivided lots to its members on a proportionate shareholder basis. Another unique feature was the fact that other prominent builder-developers in the city were shareholders in Carma, including Quality Construction, and the major shareholder, Nu-West Homes. By 1971 Carma was recording pre-tax profits of $1.6 million on gross sales of $8.2 million, and in the following year when it went public the company upped its sales to $17.0 million and profits to $4.8 million. After it became a public company in 1969, Nu-West Development Corporation Limited recorded an average annual growth rate of 27 per cent and in 1973 reported sales of $67.8 million. Both Carma and Nu-West concentrated primarily on development in the north part of the city. Geographically separated, supported by the construction industry, and in control of relatively cheap land either through sale by the City or on solid options to purchase, Kelwood and Carma led the land development industry in creating suburban Calgary in the late 1950s and well into the 1960s.

This situation began to change in the mid-1960s with the arrival in the city of a prominent Winnipeg-based competitor to Kelwood and Carma. Incorporated in 1961, British American Construction Materials Limited was a merger of several companies involved in the heavy construction, building materials, housing, and land development industries.[8] When it arrived in Calgary in 1965 the company was already a national player in the construction industry. Once in Calgary, it continued its diversified operations, which included the production of cement, concrete, asphalt, gypsum wallboard, cabinets and windows, and pre-assembled housing units. In 1966, the company purchased Engineered Homes, an important residential homebuilder and land developer, and a year later shortened its name to BACM Industries Limited. Within two years of its arrival in the city, the company increased its overall sales from $32.8 million to $53.7 million. These numbers, as well as the double-digit profit margins, were enough to attract an even bigger player to the city in the form of Genstar, a member of the powerful Belgian international mining conglomerate Société Général de Belgique.

Incorporated in Canada in 1951 as Sogemines Ltd. (the name Genstar was adopted in 1959), the company was originally interested in mining operations. However, it quickly became involved in other activities, forming Inland Cement (1954), Iroquois Glass (1958), and Brockville Chemicals (1959). In 1965 Genstar amalgamated its three subsidiaries and became in effect a large industrial corporation with assets of approximately $100 million. Noting the opportunities afforded by a relatively fragmented house building and land development industry, Genstar decided to move west and shift its operational focus. The natural choice was Calgary, a city increasingly recognized as the national administrative centre of the oil and gas industry, and more significantly boasting a 5–10 per cent annual population increase. In 1968 Genstar acquired a controlling interest in BACM and assumed full ownership in 1970 at a total cost of $40 million. Through BACM, Genstar embarked on a $30 million buying spree. By 1971, Genstar controlled Consolidated Concrete Ltd., a major player in the ready-mix concrete business; Conforce Products Ltd., a manufacturer of pre-cast and pre-stressed structural concrete products; Borger Construction Co. Ltd., a major force in the installation and servicing of utilities; and the Kelwood Corporation, one of the two leading land development companies in the city. In 1972, when sales topped $360 million, Genstar was ranked in the top echelon of Canadian companies.

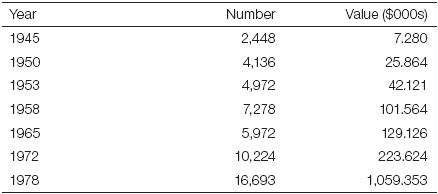

Table 1

Number and value of building permits 1945–1978 (selected years)

The increasingly powerful presence of Genstar must have been disquieting to Calgary’s chief civic administrator, especially after City Council began considering further annexation in mid-1972. In this context Hamilton’s reasons for ordering an inquiry into the activities of a potential monopoly presence within the construction and land development industries is not surprising. Indeed, he may even have anticipated the comprehensive annexation proposal, and the decision to put it to the ratepayers in a plebiscite at the end of 1974. His intention to submit the report, if warranted, to the federal authorities for investigation under the Federal Combines Act is also understandable. Hamilton’s bypassing of City Council is baffling. Possibly he believed that certain aldermen were more sympathetic towards developers than their political office allowed. Certainly Mayor Rod Sykes shared that opinion. Hamilton might also have anticipated Council’s reluctance to spend taxpayers’ money in what might have been construed as a witch hunt. Or, as argued later, he may have simply ignored Council’s right to know. Whatever the reason, Hamilton opted to operate alone. By the end of 1972, he was ready to put his highly irregular plan into action.

In January 1973, Hamilton commissioned a private study by two reputable Calgary firms. Burnet, Duckworth, Palmer, Tomblin, & O’Donohue were lawyers; Laventhol, Krekstein, Horwath, and Horwath were accountants and management consultants. Their task was to investigate the activities of Genstar in Calgary and peripheral areas in order to determine if “the scope of such operations is such that Genstar Limited has attained or could attain a position where its activities could be deemed capable of unduly preventing or lessening competition or adversely affecting prices in one or more of the said industries to the detriment of the residents of the City of Calgary.”[9] Code-named Apollo, the secret investigation was to be conducted by as few people as possible, with progress reports going to Hamilton only. Noting the unorthodox nature of the assignment and its legal implications, both companies were wary. Stressing that “we will not be in a position to guarantee our findings,”[10] they accepted the commission on the condition that the final report remain confidential and under no circumstances would be released to the public. When they began their investigation, both companies were under the assumption that the above requests would be honoured.

Hamilton kept his own counsel on the matter until June 1973, when he confided in fellow commissioner, Denis Cole. A month later, the investigators informed Hamilton that the cost of the report would be significantly higher than his contingency fund.[11] Worried that payment might be an issue, the investigators suggested that the mayor be advised. Hamilton refused.[12] Though now clearly concerned about the clandestine nature of Apollo and its possible implications, the investigators went ahead and completed their investigation in the fall of 1973. A draft of the report was delivered to Hamilton on 11 December with a cautionary accompanying letter that noted,

The conclusions and findings contained herein have been arrived at on the basis of all public facts known and obtainable by the writers and from ancillary information obtained or obtainable as deemed necessary on a judgmental basis by our firms. Since the investigation required to a large extent the exercise of judgmental factors we are not in a position to guarantee our findings although these finding were conscientiously prepared on the basis of all information obtained or obtainable by us.[13]

Clearly nervous about possible ramifications, the writers went on to stress that it “has been prepared solely for your information and guidance and may not be used or quoted in whole or in part in connection with any public communication or release without our written consent.” In early January 1974, Hamilton gave copies to the other appointed commissioners and the City solicitor. At this point, neither the mayor nor City Council had been advised of either the investigation or the report.

Details in the often rambling and repetitive report were as potentially explosive as the investigators feared. It opened with four main conclusions.[14] According to the report, an oligopolistic situation existed in the Calgary construction industry, one dominated significantly by Genstar to the degree that its activities could be deemed capable of “unduly preventing or lessening competition or adversely affecting prices.” Second, the report included the land development industry by concluding that Genstar operations “could, if they have not already, attain a position where its activities could be deemed capable of unduly preventing or lessening competition or adversely affecting prices . . . to the detriment of the citizens of Calgary.” Focusing on land assembly on the city’s periphery, the report surmised that BACM had acquired extensive tracts of undeveloped prime land in the city’s south-east corridor. The report made similar observations about land assembly by Carma in the northwest and northeast and Nu-West in the northwest.

Third, the report believed that a prima facie case was sufficiently strong to justify submission to the appropriate federal authorities. The final conclusion weighed heavily on Hamilton. Whether it was just a manifestation of the authors’ nervousness or indicative of some very broad conclusive leaps, the report recommended that the burden of proof wait on subsequent investigations in the form of “an extensive analysis of each of the industries and markets.”[15] Despite its authors’ cautionary tone, the report was a forthright document. The details were disturbing. With respect to the construction industry, the report focused primarily on Genstar subsidiary BACM Industries, though Nu-West and Qualico Developments were also cited. In documenting its “dominant role in heavy construction, building materials, land development and housing activities,” the report discussed BACM’s extensive horizontal and vertical involvement in virtually every component of the house building industry from land development and utilities servicing to quarries and concrete manufacturing plants, and from house sales to gypsum wallboard and kitchen cupboards.[16] The report also alluded to Genstar’s invisible presence. According to the report, Genstar fostered the practice of retaining, advertising, and developing trade names of locally acquired businesses with little overt attempt to relate these names to their parent company. In referring to the ostensible competition between Keith Homes and Engineered Homes, the report noted that there was “no apparent disclosure to the public that they were both divisions of the same company.”[17] In the housing market, cabinets were manufactured by Sungold Manufacturing, windows by Sunrise Distributors, and gypsum wallboard by Truroc Gypsum Products. Plumbing and heating services were supplied by Parkdale Plumbing and Parkdale Heating, and electrical work by Midwest Electric. Though all were owned by Genstar through BACM, the report indicated that the public probably construed them as independent operators.[18]

In terms of land development, the report singled out BACM, Carma Developers Ltd., Nu-West Development Corporation Ltd., and Quality Construction Ltd as comprising the elements of monopoly control. Noting dovetailing of interests (BACM, Nu-West, and Quality were all shareholders in Carma) the report argued that by concentrating in the growth corridors on the city periphery, “these developers are anticipating the extension of the City boundaries in the growth corridors chosen by them. Should their anticipation prove correct, the companies face the prospect of windfall profits and control of developable lands and serviced lot supply.”[19] In the report’s view, smaller operators, unable to compete with Genstar’s “vast resources, were predictable casualties.”[20] According to Donald Gutstein in an article in The Second City Book, Genstar’s financial muscle was further augmented through its very close ties with the Royal Bank.[21] The report also saw a threat in Genstar’s foreign ownership and devoted significant attention to its international range of activities.

With the report’s strong indictment now in their hands, the commissioners faced the decision of how to act upon it. In a confidential letter to Mayor Rod Sykes on 28 February 1974, Denis Cole, the newly appointed chief commissioner, summarized his view of the situation. Certain elements of the report gave “cause for grave concern.” While he felt that the problem was incipient, Cole added that Genstar’s capacity to unduly influence the supply and price of serviced land was growing, and that what “was a possibility is now a serious threat,” one that would unfold on Genstar’s terms. Though Cole advocated the need to break Genstar’s control, he did not see the City as an active agent. He rejected the possibility of withholding services from the corporation’s land holdings, and the idea of civic land banking as too expensive and ultimately futile. His solution was to involve the federal and provincial governments—the former through a submission under the Federal Combines Act, the latter through several initiatives including land banking and direct involvement in the construction industry. Cole concluded, “It is the unanimous view of the authors of this report, the Commissioners and our City Solicitor that it would not be in the public interest to reveal the contents of this report to Council or the public until we together have had an opportunity to thoroughly review its implications and the steps to be taken to safeguard the interests of citizens of Calgary.”[22]

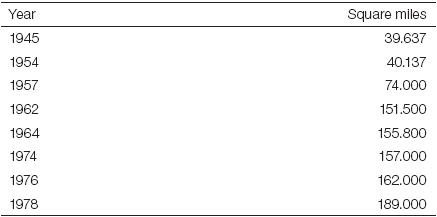

Table 2

Area of Calgary 1945–1978

Sykes, though very upset over Hamilton’s actions, agreed with Cole.[23] Council was not notified. On 30 April 1974, the Board of Commissioners discussed the matter at length. It was agreed that the best course of action was to give the report to the appropriate federal authorities but not before a second opinion was received, and after BACM had seen it. In the interim, the report was to remain confidential. A land policy review was also urged.[24] The report was then sent to A.W. Howard of Howard, Dixon, Mackie, and Forsythe for a legal opinion. It was also decided not to allow BACM to see the report until after Howard’s response. Howard offered his first opinion on 24 July. Though he could not comment on the factual data, Howard supported the report’s opinions and conclusions but recommended against giving it to BACM, since the “publicity that might result therefrom may in fact bring the matter to public attention . . . and hamper the investigative efforts of the Combines Investigation Branch.” When Howard wrote to Cole again on 9 September, he recommended sending the report to the Combines and Investigation director on a confidential basis, with a covering letter stating that there had been no communication with Genstar. In advocating utmost secrecy, Howard stressed that “the report itself should be and remain exactly what it is—a confidential report.”[25] Eleven days later, citing concerns in “current trends in the land development, construction and housing industries which could, if they have not already, lessen the competition or adversely affect prices,” the mayor and commissioners decided on a delegation to Ottawa to present this “confidential information” to the Department of Consumer Affairs.[26]

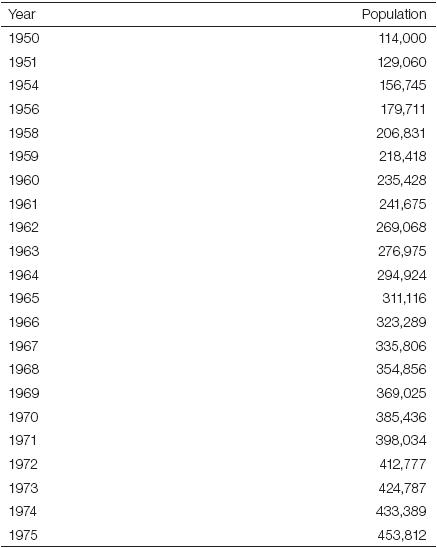

Table 3

Calgary Population 1950–1975

On 26 September, four days before Chief Commissioner Denis Cole and City Solicitor Brian Scott discussed the Genstar Report with Robert Bertrand, the director of Investigations and Research, Mayor Rod Sykes wrote a puzzling letter to Bertrand.[27] While not mentioning the report, Sykes referred to increasing monopoly control of land and construction materials and stated his belief “that too few firms now control too much land and their price setting mechanism is such as to raise residential land prices unduly.” Sykes then went on to support Cole and Scott and requested an inquiry pursuant to a formal investigation. However, he also qualified his remarks by warning that any inquiry “will undoubtedly show that the Council of the City of Calgary may itself have contributed to this concentration of land holdings by selling areas that were municipally owned to the land owners about whom we are concerned and by proceeding with annexation to assist them to bring their lands within the development market.” After acknowledging his own efforts to thwart these measures, Sykes added, “It seems rather unusual for me to draw this matter to your attention when in fact City Council may be one of the offenders in that it contributes to the problem it complains about.”

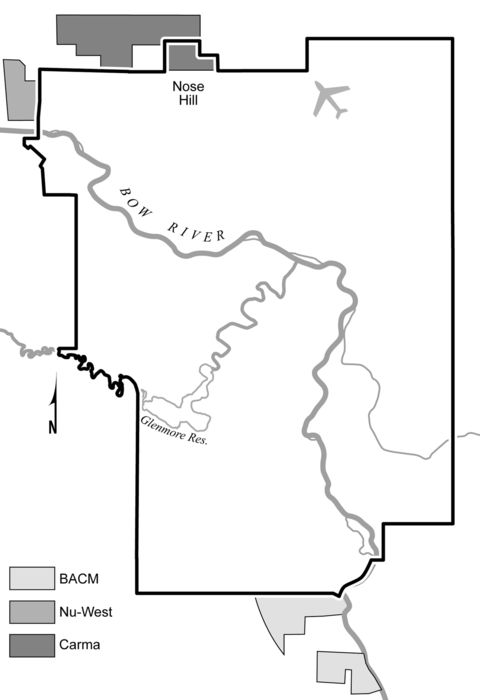

Figure 1

Comprehensive annexation 1974 (125 square miles)

The reasons behind these qualifications are conjectural. The most logical suggests that Sykes was genuinely concerned about removing himself from an inquiry that he felt might indict City Hall. However, it is also distinctly possible that it was a guarded reference to the validity of the Genstar Report as attested by his later remarks on its political nature.[28] The reply received by Sykes on 4 October from Bertrand was not helpful. Bertrand did not refer to Sykes’s fears. He did, however, acknowledge receiving the report and its usefulness in helping him determine whether a violation had occurred under the Combines Investigation Act. Bertrand then closed the matter by saying that any subsequent investigation would be privately conducted and in effect the City would be hearing no more about it.[29]

The mayor and commissioners, however, had prevaricated too long. By the fall of 1974, news of a secret report had filtered down to City Council. It is not known whether Alderman Barbara Scott was the first to secure information about the report, but she was certainly the one who brought it to the fore. On 23 September, during the regular City Council meeting, Scott requested a list of reports prepared by commissioners that had been kept from aldermen. Scott noted that she had reason to believe that such reports existed and likely thought that they had to do with the big annexation issue. Cole was evasive in his answer. Without mentioning any secret report, he told Scott that she would receive a copy but it would be up to her whether or not to release it to the public.[30] Doubtless with this latter comment, members of the press in attendance pricked up their ears.

With the press baying about secrecy, intrigue, and the upcoming annexation plebiscite, Project Apollo had become a political football. Cole tried to defuse the situation. In a letter on 30 September to the mayor and Council, with copies to the press, Cole stated that the Board of Commissioners had for some time been concerned about trends in the land development and housing industries, and that this concern had already been made public through a report to Council in July 1973.[31] In this report, fears had been expressed about the level of competition in the land development industry and the potential balkanization of the city into “spheres of influence.” Quoting from this report, Cole pointed out that it did not in any way “imply that any developer, housebuilder or a combination of them are not acting in the public interest.” Cole also noted that through subsequent regular consultations with developers, the City now had a good grasp of the land development supply.

Figure 2

Calgary developer holdings outside city limits, 1973

Cole then mentioned the Genstar Report. He acknowledged its confidential nature but argued that while it confirmed the need for vigilance, it was also inconclusive. He also felt that the aim of the report had been achieved through its submission to the federal authorities. Cole also argued strongly for keeping the report from the public, citing a possible lawsuit, the wishes of the authors, and interestingly, a desire to avoid “possible damage to a good corporate citizen.”

It was not enough. Council demanded to see the report in a special meeting on the morning of 3 October. In a closed session later in the day, and following a heated three-hour debate, it voted nine to four to release the report to the public. Council’s decision was made in the face of strong contrary advice by commissioners, the City solicitor, and Mayor Sykes—all of whom had raised the potential for legal action.[32] According to Sykes, the City would “be blown out of the water by a massive lawsuit.”[33] Alderman Eric Musgreave assessed the majority mood on Council when he said, “The important thing is that we have one politician, four commissioners and a few lawyers who are telling us that they are the important people and that they know better than we do how the people are to be governed.”[34]

The reaction was swift and predictable. In a special release on 7 October, Nu-West distanced itself from the accused by stating that “it had no connection whatsoever with the Genstar group of companies.”[35] Carma seemed unperturbed saying that “it had nothing to hide.” BACM noted its amazement that the City “could pay so much for information already available in the public domain.”[36] BACM and Carma disclosed details to the press about their land holdings both within the city and in the proposed annexations area.[37] BACM claimed ownership of 1,640 acres within the city and 3.5 square miles in the annexation area, of which 2.5 square miles was under an option to purchase. Carma controlled 7,000 acres mostly outside the city, of which 1,200 were in the proposed northwest annexation area.[38] Matters became more serious when Calgary MP Eldon Woolliams brought the subject up in the House of Commons, alluding to Genstar’s national activities. This was too much. Monopoly in Calgary and area was one thing; national implications were another. On 9 October, BACM Vice-President Tom Denton announced that the company’s reputation was “irreparably harmed” by the report’s “inaccuracies, distortions and unsubstantiated allegations,” and that Genstar was made to appear “mysterious and conspiratorial and that nothing could be further from the truth.”[39] By the middle of October and the day after the defeat of the annexation plebiscite, the City was in damage-control mode. On 17 October, Denis Cole contacted Ralph Scurfield of Nu-West, informing him that the City was well served by the land developers but that the need to protect the public warranted “close watchfulness.”[40]

But not only had the report put the City in a potentially confrontational position with Genstar and the other developers, it had also ignited a political firestorm within City Hall. Two issues emerged. One involved the relationship between City Council and its administration. The second concerned the impending mayoralty election. The press seized upon both to the extent that the issue of the report itself and what it implied were severely diminished.

There can be no doubt that City Council’s decision to release the report was an angry reaction to the way its authority had been undermined by administration and in particular, the Board of Commissioners.[41] The Albertan concurred and, in noting “an affront to democracy,” called for a review of the discretionary powers enjoyed by the commissioners.[42] One press report indicated that aldermen were so upset by the commissioners’ actions that any further resistance on their part would result in instant dismissal.[43]

Alderman Eric Musgreave summed up the situation succinctly: “We have three isolated power bases at City hall—the aldermen, the Mayor and the City commissioners. There is no level of trust between the three . . .The experts believe that they know better than the aldermen from the street. How can council govern in that situation?”[44] This view was supported by a University of Calgary political scientist who argued that the civic government in Calgary was polarized by different visions. According to Gene Dais, City Councils acted like amateur ombudsmen concerned primarily with the interests of their wards. On the other hand, Mayor Rod Sykes was a populist reformer who believed in open debate to resolve city-wide issues. In part, these conflicting perceptions about elected government’s proper role helped explain the latitude given to the appointed commissioners. In that context, Hamilton’s unauthorized action, the administration’s secrecy and withholding tactics, and a unilateral decision to take a civic matter to the federal authorities constituted predictable behaviour. Equally understandable was the rash decision made by an enraged City Council.

The second issue related to the upcoming mayoralty election in which the popular Rod Sykes was seeking his third term in office. Two of his opponents seized upon the Genstar Report as a way of unseating him. Arguing that Sykes was using the report to paint himself as a champion of justice, Ed Dooley claimed that Sykes had known about the inquiry all along and might have actually initiated it. According to Dooley, Sykes had early access to the report, since one of its authors was a former member of Sykes’s mayoralty campaign team.[45] The accusation was denied by Sykes, who labelled Dooley’s accusations as “garbage.”[46]

If the press can be believed, another mayoralty candidate took a different tack. According to a press report, Alderman Peter Petrasuk said that it was he who had actually suggested the report to Commissioner Hamilton as a need to combat undue developer influence, and furthermore had given Hamilton advice while the report was under preparation.[47] Though Petrasuk denied making the statement, Sykes disagreed and censured him for withholding important information from the mayor and other aldermen. Sykes added that Petrasuk’s secrecy was linked with a desire to capitalize on the report as an election issue.[48]

The efforts of Dooley and Petrasuk were in vain. Sykes was re-elected, albeit with a reduced majority. More significant, the big annexation proposal was easily defeated. The political shenanigans over the Genstar Report, while not pivotal to the result of the plebiscite, could hardly have had a positive influence in the minds of the voting public. The way parochial interests triumphed over good judgment was evidenced in the way city politicians dealt with the Genstar Report in the fall of 1974.

On 3 February 1975, Genstar went on the attack by giving formal notice of a lawsuit against the City.[49] According to Genstar counsel, James Unsworth, the highly discriminatory and erroneous nature of the report had “harmed the reputation of Genstar and its subsidiaries to the point that their business activities in Calgary and elsewhere have been, and will continue to be, adversely affected.” However, after giving notice of Genstar’s intention “to commence legal action for the purpose of clearing our reputation, discrediting the report and claiming damages,” Unsworth outlined what was probably the corporation’s real intent. Genstar would be prepared to drop the lawsuit, pending within two weeks an official public statement from the City confirming the report’s inaccuracies and withdrawing it from the public. Unsworth also asked for a public apology for any harm caused to Genstar. An eight-page attachment outlining inaccuracies and misinformation in the report gave notice of what the City might expect in a courtroom battle. According to this document, Genstar’s share of housing starts for the first half of 1974 was only 19 per cent, and its holdings of undeveloped lots, less than 28 per cent. The corporation did not share information and was not collusive with other companies. Monopoly, or intent to monopolize to the detriment of the market, had not been proven and could not be linked solely to size and range of operations. The attachment concluded by noting that there was “nothing in the report to support a conclusion that a monopoly exists or that any unlawful arrangements have been entered into by competitors in the industries served by Genstar.”

Though it allowed the two weeks to pass without comment, the City felt it had little option. Faced with the prospects of a seven-figure lawsuit that it very well might lose, the City took the safe route. Also, since Genstar’s lawsuit also included the two investigating companies, both of which had stipulated the confidentiality of the report as a prerequisite to its preparation, further legal action against the City was a possibility. Following several meetings, the matter was finally resolved on 23 June 1975. In a joint press release, the City admitted that “the report contained inaccuracies and could contain innuendos that could reflect unfairly on Genstar and its subsidiaries for which the City sincerely apologizes.”[50] As agreed by the two parties, the matter was declared closed, and no further comment was made by either. Six months later, BACM announced that it had sold its 8 per cent interest in Carma “to allay public concern no matter how ill-conceived.”[51]

Since the federal government had decided to conduct a preliminary investigation, final resolution had to wait another year. Following detailed interviews with several civic administrators, the Investigation and Research Branch of the Department of Consumer Affairs concluded that further inquiry under the Combines Investigation Act was not warranted. In a press release on 15 June 1976, Director Robert Bertrand announced that no violations had occurred or were about to occur. According to George Orr, director of the federal Bureau of Competition Policy, Genstar was not the only big operator in construction and land development in Calgary, and “being in a monopoly position was not in itself an offence under section 33 of the Combines and Investigation Act relating to mergers and monopolies.” Rod Sykes was more caustic, noting that the decision not to hold an inquiry “indicates that a good deal of time and public money has been wasted on a political witch hunt.”[52] Project Apollo was finally put to rest.

Discussion

Several observations follow from this discussion. In terms of local government, the report demonstrated abuse of power by the civic executive branch. The fact that the report was generated in the first place without City Council’s knowledge, and then subsequently kept from it for almost a year, was a blatant breach of authority.[53] Indeed, aldermanic reaction to the report indicated frustration and anger over the undermining of City Council’s power. According to a contemporary source, the City’s commissioners ran the city as if it were a closed corporation.[54] Alderman Pat Donnelly noted the same sort of thing in 1975. In that context, the Genstar Report reinforces Jack Masson’s conclusions that local government administrators in Alberta wielded far too much power.[55]

The fact that the Genstar Report was allowed to become “a political football” raises questions about City Council. It induced bitter political infighting at City Hall and was used to undermine the credibility of an outspoken mayor. Rod Sykes was not liked by several aldermen and senior administrators.[56] His long-held conviction that City Hall was infused with apathy, ineptitude, and self-interest had led to antagonisms and resentment among Council and Administration. Rather than deciding on the best way to deal with the report, two mayoralty candidates turned it into an electioneering weapon and in so doing diminished its viability. Moreover, regardless of its accuracy, the confidential report could have been used to initiate some frank dialogue between the City and the developers. It might also have been received more favourably by federal authorities with respect to monopoly presence in the construction industry. As it was, the report’s credibility and therefore its potential for positive results were lost amid civic internecine strife.

The Genstar Report also offered some early insights into the emerging problem of urban sprawl. Enabled by transportation infrastructure to accommodate the automobile, generous mortgage financing, unrestrained utilities placements, government policies, and marketing strategies by developers, outward urban growth had begun to affect planning decisions in North American cities by the early 1970s.[57] In this period, Calgary planners equated sprawl solely with non-contiguous development.[58] To them, the decision to channel growth into corridors represented sound planning policy. Apparently distance from the downtown did not matter. The Genstar Report showed how quickly the major land developers dovetailed their interests with city planning strategies, and furnished a practical example of why they were so supportive of ongoing annexations.

The impact of the Genstar Report elsewhere is difficult to evaluate. Certainly it alerted other cities to a disturbing trend. But whether they acted upon it warrants further study. Peter Spurr made reference to it in his discussions on monopoly presence. Likely it had the most effect on the Alberta government. Already worried about unrestrained expansion and its impact on surrounding rural areas, the provincial government was hostile to the big annexation proposal. Because the Genstar Report verified what was already suspected, it may have had some influence on the provincial government’s subsequent decision in 1976 to establish a Restricted Development belt five miles wide around the city.[59]

The Genstar Report itself raises some questions. First, if all sources were in the public domain as stated, why were the authors so nervous? Certainly BACM et al. did not seem to be unduly concerned when the report was released. It was only when the matter was raised in the House of Commons and associated with the name Genstar that the parent corporation went on the offensive. Were “inside” sources consulted? Was this what Sykes was referring to in his original letter to Bertrand? In June 1976 in a private correspondence to Bertrand, Sykes felt that the report was “politically inspired.” One can also speculate about the report’s secrecy in that it appears that others knew about its existence and content.[60] In summary, there remain many unanswered questions about the report itself in terms of who gave input and why, who else knew about it, and how significant it really was.

One could also associate the public mistrust of the land developers to the Genstar Report. From the time Calgary’s suburbanization had begun under private development in the mid 1950s, there had been very little public rancour directed at developers. Usually it manifested itself in sporadic disquiet over construction details and failure to maintain satisfactory timelines for road completions and utility connections or the removal of excavated material. Sometimes adequate park facilities were a source of community protest. The matter of developers’ profits was not called into question until the rising house prices of the late 1960s and 1970s. In this context the Genstar Report simply vindicated a mounting public suspicion that never went away.

One wonders what might have happened had the City allowed the lawsuit to continue. Certainly, there were elements on City Council who welcomed it.[61] Most of Genstar’s documented inaccuracies in the report were qualitative or minor. Indeed, many of them were subsequently countered by the investigators. As already indicated, the report relied heavily on information available in the public realm. And most significantly, the authors made it quite clear that their findings were inconclusive and warranted further investigation. On the other hand, legal experts both within and outside City Hall believed that the inference of collusive monopoly put the City in a dangerous legal position. Peter Spurr of the Central Mortgage and Housing Corporation noted that inaccuracies in the report would likely make the City very vulnerable to a lawsuit.[62] Yet, given Genstar’s heavy involvement in a fast growing city, the arrival of other developers like Melton Real Estate and Daon Developments, and most important, the City’s options respecting the rate, timing and extent of development approvals, the City might have been successful in calling Genstar’s bluff.

It was the volatility of the Genstar Report that sealed its fate. The Genstar inquiry was a time bomb no one wanted to defuse and when it exploded, it was not on Genstar but in City Hall. Since it highlighted some disturbing trends in the land development and construction industries in late-twentieth-century Canada, it probably deserved a better fate. Some would suggest that this is precisely what decreed that fate. More likely, Project Apollo simply pointed out the obvious but lost its validity by inferring too much. Still, one might be excused for wondering.

Parties annexes

Contributor/Collaborateur

Max Foran has published widely on aspects of the western Canadian beef cattle industry and several areas pertinent to Canadian urban history. He is working on the issue involving the relocation of the Canadian Pacific Railway track in downtown Calgary in the 1960s. Max Foran is a professor in the Faculty of Communication and Culture at the University of Calgary.

Max Foran a publié de nombreux travaux sur l’industrie bovine de l’Ouest canadien ainsi que sur plusieurs aspects traitant de l’histoire urbaine au Canada. Il s’intéresse actuellement à la question de la relocalisation des voies ferrées du Canadien Pacifique au centre-ville de Calgary dans les années 1960. Il est professeur à la Faculté de Communication et de Culture de l’University of Calgary.

Notes

-

[1]

Susan Goldenburg, Men of Property: The Canadian Developers Who Are Buying America (Toronto: Personal Library, 1981).

-

[2]

Peter Spurr, Land and Urban Development: A Preliminary Study (Toronto: Lorimer, 1976).

-

[3]

James Lorimer, The Developers (Toronto: Lorimer, 1978); James Lorimer and Evelyn Ross, eds., The City Book (Toronto: Lorimer, 1976); James Lorimer and Evelyn Ross, eds., The Second City Book: Studies of Urban and Suburban Canada (Toronto: Lorimer, 1977).

-

[4]

Information on the outside of the relevant box in the city archives states, “This box is NOT to be opened without the express permission of the Board of Commissioners and/or City Council.”

-

[5]

For good example of this rationale, see correspondence dated 29 November 1972, file folder “Development around the City, 1972,” box 139, series VI, Board of Commissioners Papers, City of Calgary Archives.

-

[6]

Ibid.

-

[7]

See Marie Morgan, From the Ground Up: A History of Carma Developers, 40th Anniversary, 1998. Carma was named for Bennett’s daughter, Carol, and his wife, Margaret. For more information on Carma, see Goldenberg, Men of Property, 94–108.

-

[8]

For extensive information on BACM and Genstar, see Report of the Preliminary Investigations of Genstar Limited, prepared for the City of Calgary, December, 1973. (hereafter cited as Genstar Report), file folder “Genstar Report,” box 3, Land and Housing, Board of Commissioners Publications, City of Calgary Archives.

-

[9]

Genstar Report 1-1.

-

[10]

Law/accounting firms to Hamilton, 1 February 1973, file folder “Genstar 1975,” box 200, series VI, Board of Commissioners Papers.

-

[11]

Hamilton believed that the cost of the report would be $10,000–$15,000, well within his contingency fund of around $24,000.

-

[12]

23 July 1973, file folder “Genstar 1975,” box 200, series VI, Board of Commissioners Papers.

-

[13]

Investigators to Hamilton and Cole, 11 December 1973, file folder “Genstar Report,” box 3, Land and Housing, Board of Commissioners Publications.

-

[14]

Genstar Report 2-1, 2.

-

[15]

Ibid.

-

[16]

Ibid. IV-4-8.

-

[17]

Ibid, IV-23.

-

[18]

Ibid, IV-13, 14.

-

[19]

Ibid, IV-36.

-

[20]

Ibid, IV-23.

-

[21]

Donald Gutstein, “Genstar: Portrait of a Conglomerate Developer,” in Lorimer and Ross, The Second City Book, 127–8.

-

[22]

Denis Cole to Rodney Sykes, 28 February 1974, file folder “Genstar 1975,” box 200, series VI, Board of Commissioners Papers.

-

[23]

The City consulted its solicitor on whether it had the power to take Hamilton to court over the bill. When Hamilton resigned at the end of 1974, it appears that it had nothing to do with his role in the Genstar issue. Ill health may have been the major contributing factor.

-

[24]

Board of Commissioners Meeting 30 April 1974, file folder “Genstar 1975,” box 200, series VI, Board of Commissioners Papers.

-

[25]

A.W. Howard to Denis Cole, 24 July and 9 September 1974, file folder “Genstar 1975,” box 200, series VI, Board of Commissioners Papers.

-

[26]

R. Sykes to A.W. Howard, 20 September 1974, file folder 37.03, acc. no. 2001.004, J. Rodney Sykes Fonds, University of Calgary Archives.

-

[27]

Rodney Sykes to director, Investigation and Research, Department of Consumer and Corporate Affairs, 26 September 1974, file folder “Genstar 1975,” box 200, series VI, Board of Commissioners Papers.

-

[28]

Rod Sykes to Robert Bertrand, 15 June 1976, file folder 37.04, acc. no. 2001.004, J. Rodney Sykes Fonds.

-

[29]

Robert J. Bertrand to Rodney Sykes, 4 October 1974, file folder “Genstar 1975,” box 200, series VI, Board of Commissioners Papers.

-

[30]

City Council Minutes, 23 September 1974, City of Calgary Archives.

-

[31]

Denis Cole to mayor and council, 30 September 1974, file folder “Genstar 1975,” box 200, series VI, Board of Commissioners Papers.

-

[32]

City Council Minutes, 3 October 1974. Distribution of the report was probably not extensive. Copies were limited, although members of the public could buy a copy for twenty-five dollars, and one was kept at City Hall for public access.

-

[33]

Don Whitely, “Secret Reports and Politicians,” Herald, 28 September 1974.

-

[34]

Editorial, Albertan, 7 October 1974.

-

[35]

See news release, 7 October 1974, file folder 37.04, acc. no. 2001.004, J. Rodney Sykes Fonds.

-

[36]

Frank Dabbs, “City Faces Suit on Land Report,” Albertan, 8 October 1974.

-

[37]

Frank Dabbs, “Two Developers Voluntarily Disclose Land Holdings,” Albertan, 4 October 1974. Nu-West owned 2,114 acres in the city. Melton Real Estate owned 615 acres outside the city.

-

[38]

According to the report, BACM had acquired “two large and important land parcels which are not evidenced in the public land record system.” One wonders why they would be, given the propensity to control land under options to purchase.

-

[39]

“BACM Blasts Overstatement,” Albertan, 9 October 1974.

-

[40]

Denis Cole to Ralph Scurfield, 17 October 1974, file folder “Genstar 1975,” box 200, series VI, Board of Commissioners Papers.

-

[41]

“Administration Is Eroding Civic Democracy,” Albertan, 4 October 1974.

-

[42]

Editorial, Albertan, 7 October 1974.

-

[43]

“Candidates Await Result of Meeting on Secret Report,” Albertan, 3 October 1974.

-

[44]

“Administration Is Eroding Civic Democracy,” Albertan, 4 October 1974.

-

[45]

“Dooley Injects Patronage Issue,” Albertan, 8 October 1974. Sykes did not deny the accusation and argued that it had no relevance, since no confidence was ever broached. He also publicly admitted that one of the partners in the investigating firms had also been a supporter in previous election campaigns; also Frank Dabbs, “Secret City Report Hints of Land Monopolies,” Albertan, 27 September 1974.

-

[46]

“Dooley Injects Patronage Issue,” Albertan, 8 October 1974.

-

[47]

“Council Will Get Land-Holding Report,” Albertan, 4 October1974.

-

[48]

Ibid.

-

[49]

A.J. Unsworth to City of Calgary, 3 February 1975, file folder “Correspondence files, 1971–80,” box 200, series VI, Board of Commissioners Papers.

-

[50]

Press release, 23 June 1975, file folder “Genstar 1975,” box 200, series VI, Board of Commissioners Papers.

-

[51]

T.R. Denton to Rod Sykes, 22 December 1975, file folder 37.04, acc. no. 2001.004, Rodney Sykes Fonds.

-

[52]

Ibid., press release, 15 June 1976, file folder 37.04, acc. no. 2001.004, Rodney Sykes Fonds; Gary Park, “Genstar: No Evidence of Monopoly,” Herald, 17 June 1976.

-

[53]

Jack Masson, Alberta’s Local Governments and Their Politics. Edmonton: Pica Pica, 1985), 174.

-

[54]

Frank Dabbs, “Who’s to Blame for Bickering at City Hall,” Albertan, 10 October 1974.

-

[55]

Masson, Alberta’s Local Governments, 174.

-

[56]

An editorial in the Albertan on 12 October 1974 praised Sykes for his intellectual capacity, administrative ability, and dedication to the public. On the other hand, it saw him as displaying “a tragic inability to get along with aldermen and senior appointed officials” and added that “he seems to think that denigrating and bullying achieve more than co-operating.”

-

[57]

For information on the causes, impacts, and implications of urban sprawl, see Michael Bruegmann, Urban Sprawl: A Compact History (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006); Richard Ingersoll, Sprawltown: Looking for the City on Its Edges (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2006; Zenia Kotval and John Mullins, “Economic Framework and the Economies of Sprawl,” in Urban Sprawl: A Comprehensive Reference Guide, ed. David C. Soule (Westport, CT: Greenwood, 2006); Donald Miller, “Local Innovations in Controlling Sprawl: Experiences with Several Approaches in the Seattle Urban Region,” in Urban Sprawl in Western Europe and the United States, ed. Harry W. Richardson and Chang-Hee Christian Bae (Aldershot, UK, Ashgate, 2004); Lawrence Solomon, Toronto Sprawls: A History (Toronto: University of Toronto Centre for Public Management Series, 2007); David C. Soule, ed., Urban Sprawl: A Comprehensive Reference Guide (Westport, CT: Greenwood, 2006); Gregory D. Squires, Urban Sprawl: Causes, Consequences and Policy Response (Washington: Urban Institute Press, 2000).

-

[58]

Denis Cole to R. Nunn, vice-president, Daon Corporation, 15 January 1976, file folder “Annexation General 1976,” box 20, series VI, Board of Commissioners Papers.

-

[59]

Ira M. Robinson, “Trends in Provincial Land Planning, Control and Management,” Plan Canada 17, no. 3 (September–December 1977): 172. The RDA, which was one of five established in the province, encompassed 343 square miles and contained approximately 3,350 parcels of land held by 2,800 owners.

-

[60]

Rod Sykes to Robert Bertrand, 15 June 1976, file folder 37.04, acc. no. 2001.004, J. Rodney Sykes Fonds.

-

[61]

In response to potential litigation, one alderman is reported to have said, “Let ’em sue.”

-

[62]

Peter Spurr to Denis Cole, 16 October 1974, file folder “Genstar 1975,” box 200, series VI, Board of Commissioners Papers.

Liste des figures

Figure 1

Comprehensive annexation 1974 (125 square miles)

Figure 2

Calgary developer holdings outside city limits, 1973

Liste des tableaux

Table 1

Number and value of building permits 1945–1978 (selected years)

Table 2

Area of Calgary 1945–1978

Table 3

Calgary Population 1950–1975