Résumés

Abstract

In its most recent history, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) has taken central stage in two interstate wars and multiple civil conflicts with trans-border dynamics. Somewhat less well known is the fact that the DRC is also a prime example of a different, continent-wide African problematic: the precarity of land rights and resulting conflicts over land tenure. This paper is part of a study that explores interactions between tenure conflicts at the micro-level and the larger ethnic, civil and interstate conflicts of the region. In its first part, the article discusses conflict study approaches from various disciplines and the published literature and makes the case for a multi-scalar critical geopolitical conflict analysis. The second part presents case studies, the survey questionnaire and interview based fieldwork results that reveal the near ubiquity of tenure conflicts in North Kivu and show the causes of these conflicts and how they tend to proliferate at the rural grassroots base and subsequently extend upwards.

Keywords:

- Land tenure,

- tenure conflict,

- conflict propagation,

- civil conflict,

- North Kivu,

- DR Congo,

- conflict studies,

- critical geopolitics

Résumé

Dans son histoire récente, la République démocratique du Congo (RDC) a été au centre de deux guerres interétatiques et de plusieurs conflits civils avec d’importantes répercussions transfrontalières. Quelque peu moins connu est le cas de figure que constitue la RDC quant à une problématique presque omniprésente en Afrique : l’insécurité foncière et les conflits qui en découlent. Cet article fait partie d’une étude qui explore les interactions entre des conflits fonciers à micro-échelle et des conflits ethniques, civils et interétatiques de la région. Dans la première partie, l’article présente différentes approches d’études de conflits, leur littérature, et il propose une analyse géopolitique critique. La deuxième partie présente des résultats d’un travail de terrain au Nord Kivu qui démontrent la quasi-ubiquité des conflits fonciers, leurs causes et la façon dont ils ont tendance à proliférer et se propager à partir de leurs bases rurales.

Mots-clés :

- Régime foncier,

- conflit foncier,

- propagation de conflits,

- conflits civils,

- Nord Kivu,

- RD Congo,

- études de conflits,

- géopolitique critique

Resumen

En su historia reciente, la República Democrática del Congo (RDC) ha sido el centro de dos guerras interestatales y de varios conflictos civiles con importantes repercusiones fronterizas. La RCD, como caso de figura problemático casi omnipresente en África: la inseguridad de la propiedad inmueble y los conflictos resultantes, son menos conocidos. Este artículo concierne un estudio que explora las interacciones entre conflictos de propiedades de bienes raíces a micro-escala y conflictos étnicos, civiles y interestatales de la región. En la primera parte, se presentan diferentes enfoques del estudio de conflictos, sus fuentes documentales y se propone un análisis crítico geopolítico. En la segunda, se presentan los resultados de un trabajo de terreno en Nord Kivu que muestran la casi ubicuidad de los conflictos de propiedad de bienes raíces, de sus causas y de la manera como tienden a propagarse, a partir de sus bases rurales.

Palabras clave:

- Régimen de propiedad de bienes-raíces,

- sus conflictos,

- propagación de conflictos,

- conflictos civiles,

- Nord Kivu RD Congo,

- estudios de conflictos,

- crítica geopolítica

Corps de l’article

Introduction

Within the past two decades, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) has experienced two sequential wars that have plunged the entire region into large-scale violence and suffering, as well as social and economic devastation. Given the scale of the events, it is not surprising that a strong base of popular and scholarly literature deals with conflict and civil warfare in the DRC. However, we are convinced that much of the existing work neglects the importance of an underlying conflict nexus that continually feeds the more evident surface conflicts. This nexus essentially arises from badly managed competition, dispute and conflict over the land base.

Conflicts in the DRC are often regarded from an outside vantage point that focuses on readily observable players in the national and provincial capitals as well as those in several centres linked to resource extraction activities. Our analysis will take a different approach and show how local, oftentimes rural and seemingly peripheral grievances and opportunities are in fact very much at the heart of rural conflict. Furthermore, we will examine how these understudied sources of conflict sometimes propagate into the upper levels of state administrations, extend beyond national borders and pose regional security threats.

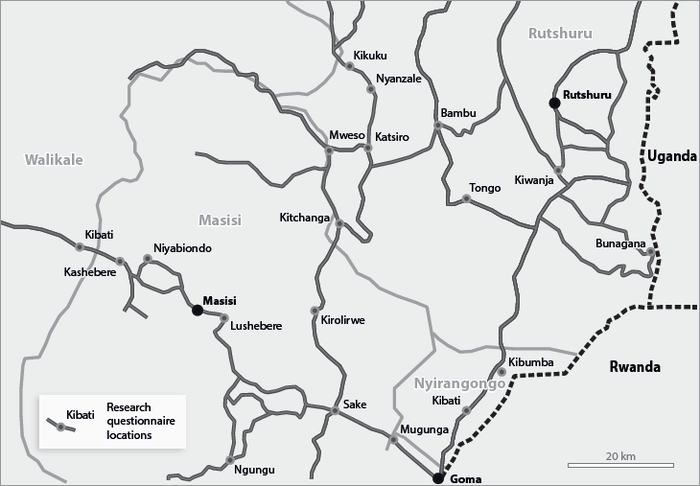

This article first presents recent disciplinary approaches to conflict studies followed by a consideration of the corresponding literature and the identification of significant lacunae. It then introduces the methodological and analytical approaches used in our study and describes our documentation, questionnaires, interviews and case study-based fieldwork results (figure 1). The paper ends with an overview of rural conflict proliferation, propagation and resolution dynamics in North Kivu.

In contrast to the great majority of existing conflict studies on the region, we propose a micro-level analysis of land tenure conflict. Within this setting, our analysis is able to establish frequent links with the meso- and macro-levels of conflict and to the socio-cultural, legal, political and regional geopolitical landscapes within which they are set.

Figure 1

Fieldwork area within North Kivu and the DRC

A critical discussion of political analysis and conflict studies literature and its application to the DRC: strengths, limitations and weaknesses

Positivist approaches and their literature

Since the turn of the millennium, the growing output of literature on conflict in Africa has gravitated around three poles: Firstly, an approach to conflict studies in political economy founded in rational choice theory, secondly, a heterogeneous group of positivist international relations schools (Neorealist, Neoliberal, Institutionalist schools, etc.) and thirdly, a similarly heterogeneous group of holistic and “critical” schools. Representatives of the latter range from scholars of critical international relations theory (Copenhagen, Paris, Welsh, Third World Security Schools, etc.) and area studies via critical geopolitics and political ecology to political philosophy, political anthropology, political sociology, history, and civil law.

A more or less recent rational choice theory-based approach to conflict studies in political economy breaks in two ways with grievance-centered approaches (see e.g. McClintock, 1984; Homer-Dixon, 1991, 1994; Percival and Homer-Dixon, 1996; Gasana, 1997; Goodhand, 2001) in that it first proposes greed as a powerful conflict motivator and secondly, adds “opportunity” and “opportunity cost” factors to the equation. In a political environment where weak central states lack coercive power and poverty coexists with point source natural resource wealth, a simple cost-benefit analysis leads the greedy to take up arms in search of material wealth. The resulting conflict scenario evolves into a self-perpetuating conflict trap if no party is dominant enough to establish a monopoly of force over the contested territory and its resources. The conflict trap can only be overcome where a “commitment technology”, such as a power-sharing agreement, alters the incentive landscape so that for violent stakeholders cooperation becomes more lucrative than conflict (Collier, 2000; Collier and Hoeffler, 2002; Reynal-Querol, 2002; Collier et al., 2003; Collier, 2008).

While recognizing economic conflict incentives, holistic scholars (Le Billon, 2001; Tull, 2004; Le Billon, 2005) have rightly dismissed mono-causal theories that reduce the political world of conflict to resource maximization considerations. In the geopolitical contexts of the Great Lakes crisis, the Congo Wars and related regional conflicts where narratives of cultural identity, language, land and tribal, ethnic and national belonging have consistently occupied centre-stage in the political discourse, an analysis of conflict from a purely material perspective leaves out half of the picture.

Holistic approaches and their literature

Le Billon (2001, 2005) and Dunn (2005) pick up on the debate that highlights the role of point source natural resources as conflict drivers in many contemporary civil conflicts across Africa. While stressing the conflict-amplifying role of easily extractable natural resources in several regional wars, these authors enrich the analysis with a discussion of societal transformations at the rural grassroots level (e.g. social and socio-economic changes linked to a progressively increasing scarcity of land resources), ethnic clashes, and strategic choices made by regional power-holders (e.g. protection from external militia activities and the establishment of buffer zones) as central elements of conflict propagation in Sub-Saharan “resource wars”.

The more detailed, history-based and also more regionally focused conflict analyses of Lemarchand (1997, 2001, 2009) contextualize a wide range of different elements: the devolution of the Zairian state during its final years; decades of Rwandan immigration into Kivu; foreshadowing land competition, as well as identity and citizenship conflicts; the Rwandan civil war; the genocide of the Tutsi population and the spread of the Rwandan conflict into Zaire; the aggressive pursuit of security, military, political and economic interests by the Rwandan and Ugandan regimes, their military intervention and occupation of the eastern DRC; the commercialization of the Second Congo War and finally, the ongoing violence of the post-war decade. The major contribution of Lemarchand’s (1997, 2001, 2009) analysis lies in his detailed portrayal of regionally interconnected stakeholder interests at the meso- and macro-levels and his recognition of the tensions underlying land tenure conflicts at the micro-level. Unfortunately, Lemarchand’s analysis remains essentially at the meso-level and therefore tends to overlook the diversity of forms of tenure conflict, something he tends to treat as a monolithic concept. We would argue that a more detailed view is required for elements that drive many conflicts in Congolese villages and for the way they interlink with the more evident events above.

More so than Lemarchand (2009), Reyntjens (1999, 2001, 2009) examines the two Congo wars and surrounding conflicts with a focus on the regional capitals, and with particular emphasis on the involvement of the Rwandan FPR regime. The strengths of Reyntjen’s research lie in its analysis of the role of Kigali as a regional power center, its commercial ties throughout the regions involved, and cross-border militia activities that Reyntjens (2009) links to the Rwandan regime. However, we would argue that in at least two points, Reyntjen’s (2009) focus on Kigali may represent an overemphasis. Firstly, it is widely acknowledged that while it played a prominent role in regional events, the regime in Kigali was only one of up to ten central state stakeholders that were directly involved in the two Congo Wars (ICG, 1998; Tull, 2004; Prunier, 2008). Secondly, and more importantly, we would argue that Reyntjen’s (2009) focus on regional capitals needs to be extended to include an examination of the players and stakeholders involved in the action, in other words, in the outlying rural areas where most of the fighting took place and where, even thirteen years after the official end of the Second Congo War, armed conflict remains widespread.

There can be no doubt that both of the two Congo Wars and the post-war violence under the Alliance des Forces Démocratiques pour la Libération du Congo (AFDL)[1] and Rassemblement Congolais pour la Démocratie (RCD)[2] regimes – and, to a lesser degree, also under the Congrès National pour la Défense du Peuple (CNDP)[3] and Mouvement du 23 mars (M23)[4] later rebellions – would have been unthinkable without strong stakeholder connections to the regional capitals. As important, however, as the foreign elements in the Kivu crisis, were the internal and in several cases, pre-existing local conflict patterns. In fact, the Rwandan crisis that was to trigger much of the regional violence of the following decade had effectively superimposed itself on the preexisting conflict landscape in eastern North Kivu. Communal violence had been documented in Kivu since the colonial era (Spitaels, 1953; Vlassenroot and Huggins, 2005; Lemarchand, 2009) and had spread throughout Kivu’s rural areas on a number of occasions after the Kanyarwanda conflicts[5] of the early 1960s and, most notably, during the democratic transition period of the early 1990s (GEAD, 1993; Willame, 1997; Bucyalimwe-Mararo, 2001; Tull, 2004; Vlassenroot and Huggins, 2005). Given the relatively recent CNDP and M23 rebellions and the continued threat still represented by Forces Démocratiques de Libération du Rwanda (FDLR)[6] fighters in rural Kivu, there is no doubt that spillovers from the Rwandan crisis remain central components of the regional conflict landscape to this day. But the full picture is much broader. From a current perspective, we would argue that at least as crucial for the continued existence and proliferation of armed groups – and this includes the FDLR, CNDP and M23 that certainly have many roots and ongoing interests in Rwanda – as their strong ties to successive Rwandan regimes is the extent to which they are socially, culturally, economically, politically and militarily embedded into their host societies. Understanding the roles of these groups involved in the regional violence calls both for an understanding of their local constraints, interests and interactions and for an understanding of their regional and cross-border interests, connections and interrelations.

In response to a badly needed local perspective on conflict analysis, Vlassenroot and Raeymakers (2004, 2009), Raeymakers and Vlassenroot (2008) and Raeymakers (2012) conducted field studies during the post-war decade in the eastern provinces of the DRC. A central theme of the authors’ analyses is violent actor multiplication in the wake of different peace accords such as those of Sun City, Pretoria and Luanda in 2002. These authors warn that beyond promoting parallel command structures in the administrative and military establishments, the power-sharing character of the inclusive agreements created strong incentives for successive new players to foment their own rebellions. Consequently, one of their most important conclusions is that, while providing for the adoption of peace treaty arrangements in the short term, ensuing power-sharing agreements served to spawn and protract violent conflict in the long term. It should be noted that this finding stands in diametric opposition to the commitment technology requirement and related policy-making implications proposed by the rational choice theory inspired conflict studies. In contrast to the current practice of relying heavily on the integration of competing militarized factions in the institution and state-building processes, the authors stress the need for rebuilding state institutions on a firm footing of grassroots-based legitimacy.

Research carried out by Mehler et al. (2013) in countries as diverse as Kenya, Liberia and the DRC comes to similar conclusions: The application of power-sharing agreements at the national level has often brought quiet to capital city environments while threatening peace in outlying areas where widely accepted patterns of authority failed to emerge at the local level. For this reason, we argue that in the conflict hotspots of Kivu, it is crucial that researchers and policy-makers pay closer attention to the grassroots level.

Several other scholars have dug deeper into the rural sources of conflict and added pieces to the puzzle. In an analysis of the transformation of political order in societies affected by violent conflict, Tull (2004) draws on field studies carried out during the final days of the RCD conflict and the immediate post-conflict period in North Kivu. His analysis of the reshaping of political power relations in the midst of apparent disorder leads the author to conclude that far from being disorganized, emerging power vacua at all social levels are immediately filled by new players and their cultural, social, economic, political and military networks. Tull explores the competitions between stakeholders vying for political influence in the conflict and post-conflict settings of North Kivu and pinpoints carry-overs from the past. One of Tull’s conclusions is that from the beginnings of the postcolonial era right to the RCD rebel state, in a quest to extend a certain amount of control throughout its territory, each successive example of central governance was forced to build neopatrimonial networks of formal institutional, semi-formal (customary) and informal (private) agents right down to the rural grassroots level. This meant the state was present and ultimately, though to varying degrees, also powerful in outlying areas. But its control was indirect, through patrimonial network alliances with agents who, by and large, furthered the interests of the central state, but who at the same time, negotiated these interests in terms of their own, and at times conflicting, goals.

The Congolese scholar Diangitukwa (2001) provides an astute analysis of patronage and clientelism as both building stones and ultimately also as consuming elements of the pre-war Zairian state. In vivid images, Diangitukwa describes how particularly in the later years of Mobutu’s reign, the Zairian state’s incapacity to directly rule the countryside forced it to negotiate costly neopatrimonial alliances with semi-formal and informal stakeholders such as customary authorities, business organizations, militias and outright gangsters to extend its rule into the villages of the outlying rural areas. The cost of maintaining its progressively complex and insatiable alliance networks finally led to the collapse of the Zairian state.

A second Congolese author, Bucyalimwe-Mararo (2001) analyzes the recycling of clientelist networks in the Kivu provinces during the 1970s and early 1980s, when the building blocks were laid for present day conflict landscapes. Bucyalimwe-Mararo (2001) examines the Zaïrianisation period of the early 1970s and shows us how the central state’s rural alliance engineering efforts culminated in a mammoth sale of colonial agro-forestry and mining assets to prominent members of the Tutsi community. As agriculture-based small-farm communities made up the majority of the population in Kivu, these land transactions led to in-depth transformations in the agricultural landscape and heightened pre-existing conflicts over land ownership and usage. At a second level, the author shows how the sale of already controversial colonial land assets to members of an ethnic community that many residents of North Kivu perceived as non-Zairian “foreigners” became an instrument in the “citizenship controversy” that permeated the electoral campaigns of the early 1990s and led the transitional parliament to adopt a resolution to expropriate and expel the Tutsi and other Rwandophone populations from the DRC. Furthermore, Bucyalimwe-Mararo (2001) and several other authors (GEAD, 1993; Willame, 1997; Bucyalimwe-Mararo, 2001; Tull, 2004; Vlassenroot and Huggins, 2005) show us how the citizenship controversy and strong exclusionary claims to ethno-tribal and national “autochthony” by political representatives in North and South Kivu during the first democratic transition period were major factors in Kivu’s communal conflicts of the early 1990s and how they ultimately became a driving force for the outbreak of the First Congo War.

Other Congolese scholars examine informal networks for power projection in regional conflict environments. Lubala-Mugisho (2001), for example, explores patterns of resistance against the RCD “rebel state” during and after the Second Congo War. The author highlights two shared elements of the most prominent resistance movements: firstly, their rural operations bases and secondly, their embedding into rural grassroots networks that provided varying levels of popular legitimacy and support. Like its opponents in Kinshasa, the RCD rebel state proved unable to extend its formal influence to the rural grassroots level. But unlike Kinshasa, the RCD also proved unable to replace this missing formal influence with an informal substitute. Consequently, the RCD had few means of countering rural resistance at its roots. This was partially due to the RCD’s lack of popular legitimacy. But it was also due to a lack of understanding of the political grassroots structures in the tribally organised societies of rural Kivu. The RCD had underestimated the resilience of pre-existing informal and semi-formal power structures. And most importantly, it had underestimated resistance by the latter to any attempt at seizing control of the primary source of rural power: the land base.

Whereas the economic and political power dimensions of rural land relations are well known to local scholars, Western academics have tended for the most part to underestimate their significance. However, there are exceptions: Vlassenroot and Huggins (2005), for example, emphasize the importance of land tenure in their regional conflict analysis. The authors point to a list of documented colonial and postcolonial conflict events and show us that neither conflict for land nor communal violence is an exclusively recent phenomenon. However, the authors also point out that conflict around both land tenure and ethno-tribal identities concurrently escalated and eventually reached their height in the decades preceding and during the Congo wars and their political aftermaths. More importantly, in reference to examples of conflict events in the eastern territories of Rutshuru and Ituri,[7] the authors reveal the interrelations between conflicts over land tenure and various forms of ethnic conflict and show how the two tend to interact and contribute to one another where land use patterns, customary land tenure systems and, in some instances, state laws, reflect ethnic biases.

Unconventional plugs to academic gaps: critical geopolitics and the “grey” literature

We have noted that the macro-level of regional conflict in and around North Kivu has been analyzed from various angles. Even so, though frequent links are drawn, astonishingly little has been published on the underlying conflict patterns at the grassroots level. This is not to say that no relevant literature exists. Numerous purpose-specific studies (Paluku Mastaki, 2005; Crawford and Bernstein, 2008; Kujirakwinja and Matunguru, 2009; Kasisi and Brown, 2009) have analyzed particular aspects of land disputes in rural Kivu, but very little has been published on patterns of rural tenure conflict at large. Similarly limited is any scholarly coverage of links and interrelations between conflict at the grassroots level and the more blatant conflicts at the middle and upper levels of political society. In the absence of a sufficient volume of “white” literature on the rural grassroots base, our analysis makes use of a diverse set of unconventional sources. Our research has used several sources of “grey” literature; the most important of which were field reports and analyses by local non-governmental organizations (NGO) and conflict mediation bodies, as well as accounts by directly involved stakeholder groups. The following paragraphs provide a brief overview of relevant kinds and individual works of “grey” and non-scholarly literature.

In mirroring the contentious contemporary narratives of the political world, discussions on land and identity-centered conflicts can reflect highly polarized positions. In the political environment of North Kivu, such discussions often reflect claims to local, regional or national autochthony and to autochthony-derived rights to land, other property, ethno-tribal or national territory, or citizenship status. At times, such claims are based on very weakly documented one-sided interpretations of historical events. Far from rejecting such one-sided points of view, analysis in critical geopolitics explicitly takes into account the polemic discourse of conflict (Foucher, 1988; Gonon and Lasserre, 2001; Mamadouh and Dijkink, 2006; Lasserre and Gonon, 2008). This may include personal observations, informal analyses, authors’ interpretative accounts, political manifestos and outright propaganda. Foucher (1988) writes that critical geopolitical analysis includes true and false historical discourses, as these tend to serve as the bases for legitimation of political positions. Nowhere is this finding more relevant than in the discursively charged landscapes of Kivu where political stakeholders use competing narratives of ethno-tribal, national and regional histories to justify their conflicting political claims. The significance of popular discourse for geopolitical analysis lies in the fact that it is a collective reflection of the cultural and socio-political landscapes within which it is formed.

A wide range of local literature falls into the above categories. Examples include the writings of the political leader of a South Kivu rebellion, Ruhimbika (2001), that provide detailed, though inconsistently documented accounts of the conflict and peacetime histories of his own ethno-tribal community, the Banyamulenge. More partisan examples include the works of Kambere-Muhindo (1998, 1999) and Ndole (2001) that claim to provide legislation-relevant proof for or against the historically derived legitimation of existing ethno-tribal territorial boundaries. Such legitimations, in turn, serve to feed political challenges to the citizenship status of ethnic communities such as the Rwandophone populations of Kivu.

Disciplinary nature of the study

Whereas our study’s immediate focal point is the micro-level of competitions around individual land plots, its broader focus is on the links that interconnect the micro-level to the meso and macro-levels where territorial competitions between ethno-tribal communities, economic interest groups, political and military factions and ultimately states and international bodies are carried out.

In contrast to realist school approaches, critical geopolitics ventures beyond the central state and interstate levels of political contention and analyzes the dynamics of conflict and cooperation at the socio-economic, socio-cultural and socio-political sub-state levels. In this often less formalized environment, critical geopolitics recognizes the significance of the arguments of those involved, not only as direct expressions of stakes and claims in supposedly rational negotiation processes, but also as (often highly subjective) bases for legitimation, establishment of identity and mobilization. In this perspective, Dodds (2001: 473) points to the discursive construction of “imagined communities” in the context of everyday life. In this same vein, we join the growing number of analysts of geopolitics such as Dodds (2001) and Batson (2008), who encourage ethnographic research at the societal micro-level as a tool for identifying and assessing those ultimately geopolitical experiences of ordinary people that lead to struggles over social identities.

Seen in this light, critical geopolitics can be deemed a platform well-suited for the microanalysis of tenure conflicts within larger, national, regional and international conflict settings. Its potential strength lies in its capacity to apply multiple lenses to the analysis of communicating conflict events at different levels of political society. Drawing on this potential, several recent research studies have stressed the important role played by tenure conflict in regional and at times interstate warfare in some of the world’s most troubled regions. One major example is Batson’s (2008) study on tenure conflict-driven cycles of violence in Afghanistan. Unfortunately, almost nothing similar has been published on the DRC.[8] Our research attempts to plug some of these gaps.

Conceptual disambiguation

Competition, disputes and conflicts over land rights are a central theme to this paper. When referring to competition in land markets, we are referring to demand side competition for land. Furthermore, similarly to Boone (2014), our analysis adopts as exogenous “givens” elements such as fierce competition in local land markets, driven by mounting demographic pressure,[9] environmental degradation, inequitable land distribution and rising land prices, these being systematic factors upon which public policy has little immediate impact.[10] In the context of fierce competition for the land base, our research interest centres on the question of how more policy-sensitive socio-cultural, socio-political and institutional factors channel competition and define its societal manifestations. We are particularly interested in exploring how, in many cases, competition degrades along an imperfect continuum and escalates from disputes to conflict, to local and regional violence and then to open warfare. In essence, we focus primarily on the confrontational side of competition, to better understand what turns competition for land into a dispute; how disputes are resolved or exacerbated; what transforms disputes into conflict; what provokes violence and how conflict expands geographically and proliferates institutionally across different socio-political environments.

For reasons of clarity, we distinguish between non-confrontational competition (bargaining);[11] contained confrontational competition (disputes) and uncontained confrontational competition (conflict). Our interpretation of confrontation broadly follows Burton’s (1990) disambiguation between “dispute” and “conflict”, where “dispute” is characterized by clearly definable sets of interests, stakes and claims, well-defined groups of stakeholders and a widely-shared desire among primary stakeholders to negotiate a viable solution. Conflicts, in contrast, tend to involve larger, less well-defined stakeholder groups and complex, interwoven and often blurred patterns of interests, stakes and claims that may involve several layers of explicit or implicit non-negotiable issues. Conflicts are often the result of interlinked and related unresolved disputes. Finally, whereas stakeholders in disputes genuinely seek resolution to the underlying issues of competition, stakeholders in conflicts may or may not. The most challenging conflicts are those in which one or several conflict stakeholders profit from the prolongation of conflict itself.

When invoking the concept of “land disputes”, we are referring to non-violent competition between clearly identifiable stakeholders over specific and defined rights to an identifiable piece of land. When applying the terms “land conflict” or “tenure conflict” we are referring to a larger range of non-violent or violent competition over land rights. “Small-scale conflicts” involve a small number of individuals or households, their effects being by and large limited to a single neighbourhood or village. These are in contrast to “large-scale conflicts” that involve some dozens or even hundreds of households or that provoke supra-local effects such as the involvement of external players or forced population displacements. On a final note, “intra-ethnic conflicts” display no discernible patterns of inter-ethnic or inter-tribal confrontation whereas “inter-ethnic conflicts” display clearly discernible patterns of confrontation along real or perceived ethnic or ethno-tribal fault lines.

An application of critical geopolitics to the analysis of land tenure conflict and conflict propagation in the DRC

Research methods and results

Our research is based on existing academic literature and institutional documentation on conflict at the macro- and meso-levels of Congolese society, but draws on fieldwork in the form of surveys and interview analyses, observation of participants and archival research to fill several lacunae at the meso- and micro-levels. The fieldwork was carried out in three stages between January 2012 and February 2014: In addition to these relatively recent sessions, fieldwork for one of the case studies, in the form of two projects between 2005 and 2007 had begun in the immediate aftermath of the of the RCD conflict during the so-called transition period.

This article sumarizes our fieldwork results in three sections. In the first place, our research questionnaire surveyed the types and frequencyies of occurrences of disputes and conflicts, the roles played by the stakeholders involved, their socio-economic, occupational and ethno-tribal backgrounds and their access to and utilisation of conflict mediation and resolution mechanisms. Survey locations included 24 villages, across the territories of Masisi, Rutshuru, Nyiragongo and eastern Walikale.

A second component of the study comprised archival research, documents, questionnaires and interview analyses that enabled us to identify different dispute patterns, escalation factors and conflict vectors. The interview series consisted of semi-structured and unstructured interviews with immediate and intermediate conflict stakeholders and their representatives, political and military stakeholders at the local, provincial and national levels, civilian, customary, governmental and international conflict mediators, customary and state administration representatives, and local and international scholars. The results led us to establish a typology of conflict.

Finally, the third component of our fieldwork consisted of four explanatory multi-modal case studies of land tenure conflicts in the territories of Masisi and Rutshuru. The fieldwork for the case studies drew on archival research, interview analysis, and in two cases, observation of participants during conflict mediation sessions. Selection of the events observed was first determined using (1) internal parameters based on the combined weight of those involved, (2) external parameters based on the availability of information on the cases under study and the availability of stakeholders for interviews with the research team and (3) by a subjective assessment of the explanatory value of the information the cases could provide. The events analyzed were not chosen as being representative of the conflict landscapes in Kivu, but rather as a means of highlighting salient factors therein.

Administration and results of the survey questionnaire in rural villages

Our analysis of over 580 questionnaires[12] from 24 villages[13] in Masisi, Rutshuru, Nyiragongo and eastern Walikale revealed that a remarkable 45% of those surveyed – and/or members of their households – had been directly and actively involved in disputes over land. In fact, every single village visited had experienced tenure disputes. Furthermore, although the frequency of dispute involvement among these villages varied between 16% and 81%, the standard deviation, at 21%, was relatively low. Given the limited number of villages surveyed across five of North Kivu’s six territories, it should come as no surprise that our research was unable to identify geographical patterns in the frequency of dispute involvement.

A revealing result of our study was that across all the groups surveyed, considerably fewer than 10% of the disputes identified had been dealt with in legal court proceedings or other formal, state-funded negotiation frameworks. The surveys and follow-up interviews also revealed that the low propensity to involve the state could not be explained only by deterrents in the form of distance or language factors,[14] but also by very low levels of expectation and trust in the existing legal system; courts were widely perceived as expensive, ineffective, biased, corrupt and overloaded.[15]

Most proceedings took place outside any formal legal framework, but were instead directly negotiated between the parties involved or mediated by a diverse range of semi-formal and informal players and groups such as clan elders, customary courts, churches, NGOs and, in several very high-stakes cases, United Nations (UN) agencies.[16]

The heavy reliance on a wide variety of non-state players for maintaining peace and order illustrates not only the relative absence of the Congolese state, but also the vital contribution of semi-formal and informal non-state players in the preservation of vital social functions and processes. It also serves to further underscore the scale of the land tenure problem. After all, despite a general low propensity to involve the legal system, over 80%[17] of court proceedings in Kivu involve litigation over land rights.

Besides their direct involvement as litigating parties in disputes, a total of 66% of the individuals surveyed (table 1) had been directly or indirectly exposed to violent intra-ethnic land-related conflicts, while 67% had been directly or indirectly exposed to violent inter-ethnic land-related conflicts. Between the two, 78% of those surveyed had been directly or indirectly exposed to a combination of all kinds of violent land-related conflicts and 83% had been directly or indirectly exposed to a combination of all categories of land-related disputes and conflicts.[18] Line A of Table 1 identifies the proportion of all individuals surveyed who experienced the five conflict exposure types listed in the title lines of columns 1 to 5. Line B provides the standard deviation of the mean for conflict experience in the 24 village groups and the mean for the overall sample. A proportion and a standard deviation are given for each of the five conflict exposure types listed in columns 1 to 5. Finally, the 24 survey locations are shown cartographically in figure 2.

Table 1

A village survey of land dispute and violent conflict exposure

It lies beyond the scope of this paper to establish statistically representative values pertaining to the variables surveyed. Nevertheless, the consistently high survey returns on land dispute and conflict exposure (between 45% and 83% of sample populations surveyed) combined with relatively low standard sample deviations between the villages surveyed (between 13% for all types of conflict exposure and 21% for direct involvement in a dispute) show that conflict over land tenure is virtually ubiquitous in the areas surveyed. Given the broad consensus that in agrarian subsistence economies such as that of the DRC, food security is closely related to tenure security (Deininger, 2003; FAO, 2012), it becomes obvious that, over and above their previously-mentioned legal and security aspects, land disputes represent an immense socio-economic burden for the population groups concerned and for society at large.

Figure 2

Province of North Kivu : research questionnaire locations

A typology of tenure conflict

Beyond providing an overview of land tenure insecurity, land dispute and conflict proliferation for the areas studied, the survey also provided a starting point for more in-depth ongoing qualitative research into different types of disputes and conflicts, makeup of stakeholder groups, conflict escalation factors and vectors of conflict expansion. The results enabled us to establish a typology of conflict that we present in the table 2 and subsequent paragraphs below. Our typology includes the conflict category, a description of the nature of the conflict and identification of the major factors involved in six distinct types of disputes and conflicts.

Table 2

A typology of tenure conflict

The Land Law of 1973 stipulates that all land belongs to the state. However, the law recognises customary institutions as land administrating bodies. In fact, customary institutions administer well over 90% of the DRC’s land base (see, for example the estimates by Tull, 2004; Vlassenroot and Huggins, 2005). Article 389 of the now more than forty-year-old law states that a future presidential ordinance will define the jurisdictional boundaries between state and customary land administrations. However, this ordinance has never been issued.

The Land Law of 1973 defines various forms of property dispossession via acquisitive or extinctive prescription and emphyteutic lease cancellation where land is either not occupied, not actively exploited or where property taxes are not paid in full.

According to sources in the land registries of Masisi and Rutshuru, annual demands for land registration have “grown exponentially” over the last decade, leaving the registries completely overwhelmed in both technical and staff terms.

Major categories of sources of conflict: succession, contract legitimacy and boundary disputes

Nearly all the land conflicts surveyed originated in one of the first three “source” categories,[19] in other words, they started off either as disputes over succession, contract legitimacy or property boundaries. The major contributing factors in the three categories are listed in table 2.

Succession disputes

Succession disputes represented one of the most widespread tenure conflict source categories for both the customary and the formal state domains. The very large majority of cases cited in the data from the survey were small-scale disputes that opposed individuals inside families or clans and tended to be mediated by family or clan elders or by representatives of the customary hierarchy. In nearly all cases, small-scale succession disputes were fuelled by demographic pressures, a dwindling land resource base[20] and confusing or conflicting inheritance practices.[21]

Only indirectly present via secondary “follow-up” disputes in our survey data, but evoked by numerous interviewees, were several large-scale cases of succession disputes, all of which opposed families and/or clans of customary nobility laying claim to contested land administration positions inside customary hierarchies. In some cases, the contested positions had become vacant as a result of deaths. In other cases, military, state and/or “rebel state” authorities had instrumentalized existing lineage disputes to replace recalcitrant customary authority holders with relatives of their own choice. Unresolved succession disputes within customary hierarchies tended to produce secondary “follow-up” conflicts amongst customary “clients” of the group concerned. The most significant conflicts tended to branch out downstream and proliferate into a multitude of contract legitimacy-related conflicts at the rural grassroots level, while simultaneously extending upstream whenever litigating parties proved capable of mobilizing support from tribal militias, central state or rebel state administrations, from factions of the national military,[22] central state administrations or political parties.

Contract legitimacy disputes

As widespread as succession disputes were disputes over contract legitimacy. In the customary domain, small-scale contract legitimacy disputes were often the result of ambiguities around contract expiry provisions in regard to demonstrable occupation of land.[23] They also stemmed from a lack of documentation, documentation errors and other administrative weaknesses at the level of the customary authority responsible for land administration,[24] as well as reportedly also from graft, stellionate and other types of fraud. Large numbers of individual small-scale contract legitimacy disputes in the customary domain were linked either to succession conflicts or to past conflict-driven forced displacement events.[25]

In many cases, contract legitimacy disputes in the formal state domain resulted from the interplay of ambiguities around contract expiries and prescription rights linked to demonstrable occupation clauses in Congolese land law, and documentation weaknesses at the land registry level. Several legitimacy disputes in the formal state domain involved overlapping contracts. In most cases, overlaps appeared to result from bona fide registration errors, inadvertently triggered by technical and administrative weaknesses at the land registry level and compounded by a lack of due diligence procedures on the part of buyers. Due to mounting backlogs in contract registration within land registries, tenure contracts can now be endorsed and registered at the Tribunal de première instance (Court of First Instance), which helps to process the growing backlog of registry demands. One problem, however, is that the endorsement process is relatively expensive and remains out of reach for many small farmers. Secondly, while facilitating the registration process, adding another agency into the registration process also increases coordination requirements and adds a possible entry port for errors.

Not surprisingly, bona fide errors are not the only result of institutional shortcomings. According to several sources amongst the small farmers and even land registry personnel, corruption and fraud were significant factors in contract legitimacy disputes involving contract overlaps. Whereas we have seen that overlaps in contracts can sometimes be due to errors at the registry office level, many cases allegedly resulted from stellionate and related fraud. Our questionnaire and interview work revealed several cases where legitimate land owners, illegitimate land occupants, customary authorities or even land administration officials had allegedly sold conflicting rights to the same parcel of land to several different buyers. Practices of stellionate and related fraud are clearly easier in situations where there are dishonest land administration agents, incomplete property records and/or an absence of common standards and due diligence procedures. In this difficult institutional environment, there was little opportunity for buyers check up on the land’s ownership history and the associated legitimacy of a contract. Conversely, legitimate owners at times found it difficult to prove ownership to interested buyers where no clear paper trail existed. It is interesting to find that, for far-reaching situations where there are major inadequacies in documentation, formal land transfer processes in the state domain have now returned to pre-formal methods for establishing ownership, such as drawing on oral testimony from neighbours and customary authority figures.

Some of the most complex cases of contract legitimacy in the area of land disputes involved title fraud. Though relatively few in number, cases of title fraud constituted significant potential conflict vectors because they typically involved relatively large tracts of land and a considerable number of stakeholders. A small number of sometimes very large-scale events reportedly resulted from coordinated property registry modifications carried out by opposing militant groups during the civil wars of the late 1990s and early 2000s[26] as well as, though to a much lesser extent, during the more recent CNDP and M23 rebellions.[27] Large-scale incidents of title fraud thus tended to have a bidirectional link to violent conflict, both causing and undergoing the effects of conflict.

Boundary disputes

Responses to our questionnaire would suggest that, besides contract legitimacy and succession disputes, boundary disputes constitute one of the most frequent “source type” conflicts. In the vast majority of cases described, it would seem that, both in the customary and in the formal legal domain, a conjunction of administrative weaknesses in areas such as surveying, contract generation and record-keeping created “grey areas” around land ownership that paved the way to disputes over both bona fide errors, deliberate changes to documents or fraud. The great majority of boundary disputes took place at the individual household level, with neighbours disagreeing over the precise position of property boundaries. In several cases, the parties involved negotiated and resolved disputes directly, whereas, in others, impartial neighbours, clan elders or members of the customary authority mediated negotiations. Nearly all the boundary disputes seem to have been contained at the individual household level. However, in a small number of cases, entire village communities were involved in boundary disputes, which generated a significant risk of collective violence and the enlistment of outside agents such as armed groups.[28]

Land use disputes

Most of the land use conflicts identified in the survey were secondary conflicts, tied to disputes over title legitimacy or boundary lines between cattle farmers and produce farmers. The result was that cattle-farmers would often feel they were justified in driving their herds over planted areas and damaging them while, inversely, small farmers felt justified in farming on grazing land and/or stealing or slaughtering cattle. Conflicts between nomadic or transhumant pastoralists and small farmers are rare in North Kivu[29] though they do occur occasionally in proximity to a small number of customary and public grazing grounds in Masisi, Rutshuru, Beni and Lubero. Many grazing grounds are increasingly being encroached upon as a result of demographic pressures. They in turn provoke boundary conflicts between cattle herders and nearby small farmers. The potentially explosive nature of land use disputes in North Kivu is due, not to their high number (they are comparatively rare), but rather to the risks they represent for ethnic polarisation: cattle farmers, particularly nomadic cattle-farmers, are predominantly Tutsi, whereas farmers of small produce are predominantly members of all the other main ethnic communities of the province. Land use conflicts therefore tend to mirror old patterns as they often oppose communities that had been actively involved as opposing parties in the armed conflicts of the AFDL and RCD wars, as well as the CNDP and M23 conflicts that followed. As a result, these conflicts are highly likely to proliferate along relatively clear-cut ethnic fault lines.

Contentious land occupations

Contentious land occupations had predominantly resulted from unresolved land disputes of the first four source conflict types. But in some cases, they occurred independently. It was quite common, for example, for lands of internally displaced persons (IDPs) and refugees to be illegally occupied by neighbours that had stayed behind or by arriving IDPs from other regions of the country. On other occasions, private concessionary lands were unilaterally occupied by farmer populations, where concessions or parts thereof had been temporarily abandoned. The lands had often been left as a consequence of previous conflicts or basic physical insecurity, in some cases because land holdings were apparently considered to be inactive long term investment assets. For locals, such land could at times seem to have been abandoned. In some instances, occupants claimed title to contentiously occupied lands by right of acquisitive prescription clauses in Congolese land law. In other cases, occupants of land taken by force based their claims, at least partially, on “indigenous birth rights” to ethno-tribal lands as opposed to rights of perceived “outsiders” or “allochthons”. Finally, contentious land occupations were also common on public lands such as national parks, other protected areas or public livestock grazing grounds, where demographic pressures and ethno-tribal territorial demands conflicted with the rights of the central state and led small farmers to use land occupations as a way to concretely establish their claims to land. In some instances, land occupations appear to have been fairly well-organized collective action events involving dozens, hundreds, or, in at least one documented instance, even thousands of households.

Forced evictions

Forced evictions typically arose out of uncontrolled disputes within one or more of the first four types of source conflict. They usually reflected the power relations in a given stakeholder landscape. Examples would be armed groups that evicted small farm households from lands under contention on the orders of medium-sized or large rural concession-holders or representatives of state authorities. The evicting parties employed armed agents such as local bandit groups, armed militias, rebel groups or regular armed forces to carry out evictions. By some accounts, the evicted parties also established or employed armed groups to effectively oppose eviction or to forcefully reoccupy land. Where power relations on the ground were unstable, forced evictions and contentious land occupations tended to alternate in consequence.

Four case studies of land disputes from Eastern North Kivu

This subsection provides a cartographic representation (figure 3) of the areas in which our four case studies are set. The marked areas are the groupements of Bukoma, Bukombo, Bapfuna, Bashali-Mokoto, Bashali-Kaembe and Kamuronza in the territories of Masisi and Rutshuru. As territorial subunits of the DRC, the groupements are placed in the administrative hierarchy of the state in the following sequence: country – province – territory – secteur/chefferie – groupement – localité. The secteur and chefferie hold an identical position in the hierarchy; their distinction lies in the type of administration: the secteurs are administered by (non-customary) central state delegates whereas the chefferies are administered by customary leaders. The groupements and all lower-ranking rural administrative subunits are also administered by customary leaders.

Figure 3

Four case studies : identification of regions and administrative units studied

Case 1: Tenure conflict conglomerate from Bashali-Mokoto and Bashali-Kaembe

The first case (figure 4) represents one of the largest and most politicized nexuses of unresolved tenure conflicts in eastern DRC; it involves thousands of households and has been repeatedly negotiated at communal, provincial, national and regional levels for over two decades. It has also been used by a number of rebel organizations and militias as an argument for legitimization and recruitment. Despite its size and complexity, we are treating the case as a single conflict for the purposes of this paper because its main characteristics are relatively clear-cut and are good illustrations of the ingrained socio-cultural, socio-economic and political rifts that define several of the large-scale tenure conflicts in North Kivu.

The primary stakeholders in the conflict are several thousand households of predominantly Tutsi but also Hutu IDPs and refugees on the one hand and a similarly large number of Hunde households on the other. Like their counterparts from the Hunde community, the Tutsi and Hutu IDPs and refugees had been either land “clients” under the customary Hunde hierarchies or small or medium-sized landholders[30] before they fled their lands in the early 1990s. A third group of stakeholders is made up of a number of former military and civilian officials of the RCD-Goma rebel state administration as well as their “client” networks of small farmers. A fourth group is composed of the senior levels of the Hunde customary authority of Bashali-Mokoto and Bashali-Kaembe.

The historical roots of the conflict go back as far as the 1930s and 1950s when two “migration waves” swept tens of thousands of Rwandan migrants into the eastern Congo. The second of the two waves was triggered by ethnic violence in the wake of the Rwandan Revolution Sociale during the terminal phase of Belgian colonial rule. This second wave swept primarily Tutsi refugees into today’s Administrative Unit of Bashali-Kaembe and Bashali-Mokoto as well as, to a lesser degree, into Kamuronza.

All of these units are politico-administrative subgroups that are led by customary leaders of the Hunde tribe and were, until the mid-1900s, predominantly settled by members of the Hunde community. Upon arrival, most of the immigrants became customary clients of the Hunde hierarchy.[31] More wealthy immigrants ended up purchasing expropriated colonial estates[32] whereas others purchased and privatized customary land tracts from Hunde hierarchies.[33]

Several decades later, during the large-scale events of ethnic violence that preceded the First Congo War in eastern North Kivu in the early 1990s, well over 100,000 Rwandophones, made up of both Tutsi and Hutu descendants of mid-century migrants and significantly longer-established families were forced to flee their lands in Masisi. Whereas most of the displaced Hutu resettled in the Hutu majority regions of Masisi, Rutshuru and Nyiragongo, the majority of the displaced Tutsi fled to Rwanda after the FPR victory in 1994 (Willame, 1997; Tull, 2004).

In the two decades that followed, tens of thousands of the displaced Tutsi from Masisi became Rwandan citizens and integrated into Rwandan society, but between ten and twenty thousand still remained, until fairly recently, in Rwandan refugee camps, while another estimated 30,000 to 60,000[34] have unofficially returned to the DRC. The unofficial return of refugees from the Rwandan camps was partially motivated by a lack of negotiated solutions and the bleak outlook for long-term refugee life in Rwandan camps. It is also alleged by local sources that the return was at least partially engineered for geostrategic reasons by the RCD-Goma and the Rwandan government. Some sources insist that the refugee return was used to steer landless populations from Rwanda into North Kivu. Others allege that the Rwandan government uses refugee movements to drive fighters into the DRC. The different interpretations of the context, scope and scale of the refugee return reflect a very sensitive ongoing controversy in the province and, in fact, in the DRC and Rwanda. Although a discussion of the political implications of the controversy lies outside the scope of this paper, we feel it important to stress its ongoing relevance, not only to inter-communal relations in North Kivu, but also to regional geopolitics.

Of the returning refugees, thousands have attempted to regain their former land holdings but most have met resistance from the current occupants and, in fact, also from the Hunde populations of Masisi at large. So far, mediated negotiations[35] and legal battles[36] over the land have been as inconclusive as political disputes and armed conflicts. At a legal level, the returnees are negotiating the validity of various types of land ownership contracts,[37] not only in terms of the porosity of formal and customary land registries but also in terms of legal and customary prescription rights and practices. In addition to direct negotiations and legal battles between the stakeholders involved, many agencies have defended conflicting stakeholder interests; at the political level, different parties have endorsed the claims of one or other of the adverse camps and, at the military level, numerous rebel groups, ethno-tribal militia and even units of the regular armed forces have engaged in combat over land rights disputes.[38] Moreover, both of the largest stakeholder groups represent extremely fertile sources of recruitment for some of the region’s most notorious rebel and ethnically defined militia forces,[39] so providing the conflict with a permanent means of renewal. As a result, the undiminished conflict potential of the case lies not only in its sheer size – as reflected by the area of land at stake and the size and relative power of the stakeholder groups involved – but also in the polarization it creates along very clear-cut ethnic fault lines.[40]

The ethnic polarization of the conflict is further aggravated by the fact that several high-ranking members of the RCD-Goma, an organization that had presented itself as an agent for displaced Rwandophones, benefitted from disputed land transactions in Masisi during the heydays of the RCD rebellion in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Several of these transactions have now been at risk of rescission for several years. In response, the protagonists have not hesitated to link their own personal land rights interests to those of the displaced Rwandophones. The resulting tangle of stakeholder interests has further complicated the negotiation process, while simultaneously heightening the already marked ethnic tensions created by the conflict.

An enigmatic stakeholder role is also played by the upper levels of Hunde customary authority. This is partly due to the rationale behind its role in rural society; its constitutionally acknowledged and vaguely defined mandate is to manage customary lands for land-seeking peasant farmers, regardless of their ethno-tribal backgrounds. This mandate can easily come into conflict with its traditional and still very widely-expected role of representing the interests of its own ethno-tribal group and protecting their privileged access to the ethno-tribal “homeland”. In the current situation of a heightened scarcity of land and fierce competition for land in large areas of eastern Kivu, it becomes increasingly more challenging for customary authorities to reconcile these two roles. But beyond the contradictions inherent in these roles, Hunde authorities are often accused by members of their own tribes of having transferred much of the “tribal land heritage” into the private property domain coveted by “ethno-tribal outsiders” and, more seriously still, to Tutsi and Hutu landholders. Many small Hunde farmers regard the repossession of disputed Tutsi and Hutu owned plots as a form of partial redress for perceived harm suffered in the past.

In the face-off between the rival stakeholder groups, each of the opposing camps has had some success in involving political parties and even more so, in mobilizing armed groups. Furthermore, each side has fostered the growth of opposing network structures inside successive state administrations, the national army and, at least in the case of the Rwandophone IDP populations and the former RCD administration, also within neighbouring national administrations.

As a result, the conflict has long spread beyond its region of origin. Moreover, refugee movement across international borders, the cross-border economic interests of several Rwandan landholders with stakes in the disputed lands as well as cross-border militia activities draw neighbouring states and international agencies into the stakeholder landscape and essentially tie returnee land claims conflicts to complex and longstanding issues that directly involve the governments of the DRC and Rwanda.

In fact, it is no secret that the bilateral relations between the DRC and Rwanda have been strained and sometimes outright antagonistic over the past two decades. The Rwandan military has played a pivotal role in the two Congo Wars between the mid-1990s and the mid-2000s and Rwanda has only withdrawn its military forces from its neighbour’s territory in response to massive pressures from international donors and the United Nations Security Council (UNSC). Several senior Rwandan politicians have in the past justified military involvement in the DRC on security and humanitarian grounds. Their arguments have included the right to protect security interests against ethnic militias and armed rebel factions operating from Congolese territory or the responsibility to protect Congolese Tutsi populations from persecution or even genocide. Others, such as Rwanda’s former president Pasteur Bizimungu, have publicly claimed parts of North and South Kivu as part of an ancient Rwandan “homeland”. In turn, the DRC has accused Rwanda on several occasions of using refugee repatriations as a channel for steering fighters into Kivu and promoting its geostrategic (“buffer zone establishment”) and economic (“natural resource exploitation”) interests within the territorial limits of the DRC. In addition, both sides have repeatedly accused each other of supporting hostile militia. Unfortunately, according to most sources, there is ample proof to substantiate the allegations of both sides.[41]

Figure 4

Tenure conflict conglomerate, Bashali-Mokoto and Bashali-Kaembe

Case 2: Rural tenure conflict case study, Bapfuna administrative unit

The Bapfuna case (figure 5) evolved out of a long-standing boundary and contract legitimacy dispute between a concession-holder of the Hutu community and well over one hundred small farm households, almost solely from members of the Hunde community. According to sources at the land registry, the concession-holder had acquired contested rights to former colonial concession lands that had been re-occupied by small farmers and demonstrably managed by Hunde customary leaders for several decades. Demonstrable occupation-derived rights were thus in conflict with opposing acquisition rights through title that was contested and therefore uncertain. The legal status remained unresolved for years while the bureau foncier des cas litigieux (Office for contested land cases) attempted to mediate negotiations between the parties until the concession-holder established his own concrete reality by driving cattle through small farmers’ plots, destroying small farmers’ homes and allegedly employing the Nyatura, an ethnically defined militia, to forcefully evict dozens of small farm households. Within a few months the conflict spiralled into a major standoff between two ethnic militias with high numbers of casualties and the forced displacement of over 1,000 small farm households to regional IDP camps.

Figure 5

Rural tenure conflict case study, Bapfuna administrative unit

Case 3: Rural tenure conflict case study, Bukombo administrative unit

The Bukombo case (figure 6) developed out of a boundary dispute by well over 50 small farm households over concession lands and disputed land occupations. The concession lands had been temporarily abandoned by their owner, a Tutsi family, during the RCD war and the violent post-war years. This had led neighbouring – by and large Hutu – small farm populations to encroach upon the concession lands. As regional conflicts lessened, the concession-holder reclaimed rights to the occupied lands while the new occupants refused to give up the plots that they had now been farming for several years. The ensuing negotiations mediated by local customary authorities were inconclusive. Land occupations through the use of force continued and were met by violent evictions in late 2011 when the concession-holder allegedly employed CNDP militia members and later, soldiers of a former CNDP unit, now formally integrated into an Forces armées de la République démocratique du Congo (FARDC) battalion, to forcefully evict the occupants. The small farmers, increasingly better organized and allegedly supported by FDLR fighters, killed cattle and attacked concession workers in return. The conflict progressively escalated along ethno-political fault lines, opposing a Tutsi clan supported by primarily Tutsi soldiers against Hutu farmers supported by Hutu militia. The violence abated when third-party-sponsored negotiations through customary courts and the conflict mediation program of the UN Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat) led to a series of compromises that in actual fact involved the concession of a significant portion of the occupied land to its de facto occupants.

Figure 6

Rural tenure conflict case study, Bukombo administrative unit

Case 4: Semi-urban tenure conflict, Bukoma administrative unit and Kiwanja

During the period of rapid urban growth that characterized the Second Congo War and its aftermath, the city of Kiwanja enclosed and incorporated a number of private concession lands, some of which were haphazardly subdivided and turned into building sites. The Kiwanja case (figure 7) developed out of a long-standing contract legitimacy and contentious occupation dispute in which a private concession was allegedly fraudulently subdivided and transferred by members of the city administration of Kiwandja and subsequently acquired and occupied by over fifty households. After investing substantially in their new homesteads and several years of demonstrable occupation, the occupants are claiming ownership rights. According to our research, the occupant population is made up of several ethnic groups including Hutu, Nande and Hunde. The case remains legally unresolved and continues to be mediated by the bureau foncier des cas litigieux (Office for contested land cases) of the territorial administration in Rutshuru. Large-scale violence has so far been avoided, but threats from ethnic militia have been reported on several occasions. The fact that this case opposes an ethnically heterogenous group of smallholders and peri-urbanites to a Tutsi landholder family in a next to urban context, lends an element of class conflict to the case. The alleged involvement of ethnic militia might seem surprising at first glance. A possible explanation may lie in a widespread regional supra-ethnic logic of exclusion that divides communities into “autochthons” and “allochthons” and squarely assigns the Tutsi to the latter category.

Figure 7

Semi-urban tenure conflict, Bukoma administrative unit and Kiwanja

Case study results summary

Whereas all the above cases represent major collective events, their sizes and their social, political and security-related impacts differ widely. Nevertheless, a number of patterns can be identified: judicial hearings resolved none of the four conflict events; all these events generated some level of violence, though its scale varied widely; while to differing degrees, each of the events involved mediation efforts by an external agency; the state played a major part only in mediation efforts around very high-stakes conflicts and several mediation efforts seemed to be at least temporarily successful in mitigating violence, but in many cases their effects appear to have been short-lived, as in only one of the four cases has conflict mediation led to an apparent resolution of the underlying conflict. Lastly, in all four cases, stakeholders were able to draw on external support: The first and far largest case gave rise to involvement by political parties, irregular armed groups and units of the national military forces. In two of the three smaller cases, armed support was limited to irregular armed groups and, in at least one case, it included unofficially involved regular forces. In at least three cases the armed mobilization suggested ethnic or ethno-tribal linkages. Moreover, the tenure conflicts of at least three cases provoked bitter ethno-centred dissention, notably in and around the immediately affected communities. In the two largest cases, the disputes left virulent ethno-centered scars on political debate in the provincial centres, in other words, well beyond their immediate source regions. The first and by far largest conflict had a direct impact on regional interstate and security relations.

Discussion on tenure conflict patterns

To return to the initial postulates of this paper, the analysis of the answers to our questionnaire revealed that land disputes are extremely widespread in the areas of North Kivu we surveyed; nearly half of the respondents had been involved at some time or other in such disputes. At a first level, the high number of replies on land disputes confirm our hypothesis that strong competition for land is a defining element in the land markets of North Kivu. This competition is driven by relative land scarcity, which again is a product of severe demographic pressures compounded by a widespread escalation of land prices, inequitable land distribution and environmental degradation. At a second level, the high number of responses on land disputes also reflect the incapacity of the DRC’s property regimes to steer competition for land in non-confrontational directions. This is because of shortcomings in both the juridico-administrative and the customary tenure systems that leave much of the population in a physical and legal wilderness in terms of their sole source of survival and livelihood, their land base. At the same time, the deficiencies in the country’s justice system and the inadequate alternatives provided by customary, informal and extra-legal mediation structures prevent many of the resulting disputes from arriving at negotiated resolutions. In this context, it is hardly surprising that many disputes end up in conflict. The widespread proliferation and low cost of small firearms that the previous wars have brought into North Kivu, combined with the profusion of well-entrenched armed groups and a disparate national military force that negotiates its own, often very local agendas, means that deterrents to adopting armed solutions for settling land disputes are virtually non-existent.

Our fieldwork enabled us to establish a typology of land disputes that identified six types of tenure conflict, four of which are “source type” disputes and two are large-scale conflicts resulting from the escalation and interlinkage of one or more source types. The typology identifies a range of educational, socio-economic, socio-cultural and institutional escalation-related factors that explain how a conjunction of unresolved disputes over successions, contract legitimacy, boundary lines and land usage provoke larger-scale conflicts that lead to forcible land occupations and/or forced evictions. We then presented four case studies illustrating tenure conflicts in advanced stages of escalation. The four case studies demonstrated how unresolved conflicts over land have a tendency to interlink and escalate where firstly, the socio-cultural and socio-economic substrates dispose of certain escalation-conducive elements (such as, for example, conflicting conceptualizations of property rights or conflicting land use practices), where secondly, the disputed stakes are significant enough to attract a variety of conflict vectors and where thirdly, disputes can tie in with preexisting conflict patterns.

The predominant role of ethnic or ethno-tribal aspects in the analyzed large-scale conflicts contrasted notably with their inconspicuous role in smaller, non-violent land disputes. In several of the large-scale events, ethnic or ethno-tribal patterns opposed individual Tutsi landholder families to large numbers of Hutu small farm households, Hutu landholders to Hunde small farm households or Tutsi and Hutu smallholders and farmers to Hunde smallholders and farmers. In the fourth case study, the smallholders occupying the land were an ethnically diverse group. In this context, a supra-ethnic discourse of exclusion overrode ethno-tribal divisions and rallied one stakeholder group and its supporters behind the unifying banner of autochthony.

Autochthony in North Kivu refers to two distinct levels of social differentiation. The first level refers to ethno-tribal autochthony and the association with an ethno-tribal homeland that is normally seen in terms of only one ethno-tribal community. A number of communities in North Kivu claim such ethno-tribal homelands, based on real or perceived historical settlement areas. The second autochthony level corresponds to national autochthony. Broadly speaking, national autochthony refers to ethno-tribal autochthony inside Congolese territory. At an administrative level, the DRC has given national recognition to a large number of ethno-tribal communities by establishing rural politico-administrative subunits that are administered by formally recognized customary leaders.

Despite the fact that successive Congolese governments have repeatedly reshaped these ethno-tribally defined administrative subunits over time, they are still widely perceived as reflective of longstanding, if not historical ethno-tribal geographies. But not all of the ethnic communities of the DRC are represented in this administrative geography. A consequence of this selective recognition is that members of the unrepresented groups, such as the Tutsi, are often defamed as “allochthons” by members of the represented groups. Worse, the unrepresented groups have no recognized customary land tenure systems of their own that its members could fall back on. As such, the existing administrative subunits of the DRC are central to an ongoing, very contentious socio-political debate over autochthony and autochthonous rights to land and other resources.

At the ethno-tribal level, standard claims to autochthony and to the right to ethno-tribal homelands often go hand-in-hand with territorial claims against people who are perceived as “allochthons”. In several cases, these claims serve as justifications for blanket claims to land or other exploitable resources in the concerned areas. In some cases, autochthony-based land claims also include claims to exclusive residence rights.

In a context of competition for land, land disputes and tenure conflict, autochthony claims have the potential to escalate into major conflicts. In the first place, this is because they can project a specific claim from an individual or small collectivity to a broader collective level. Secondly, they are inherently exclusory and non-negotiable. By and in themselves, autochthony claims constitute a powerful tool for mobilizing support in land disputes by appealing to a particular autochthonous collectivity. This potential is widely exploited by both land tenure stakeholders and political players in North Kivu.

Even so, this should not lead us to conclude that, in the broader context of land tenure conflict, claims to autochthony are little more than rallying cries and smokescreen justifications for what are essentially economic claims to land assets. Several of our interview sessions clearly showed that, to many small farmers in North Kivu, the concept of an ethno-tribal homeland is a vital part of their identity, reflecting the geographical, cultural and spiritual roots of their family, their clan and their tribe. It is in this context that for many users of customary tenure systems a plot of land represents at once an economic asset and, as part of a shared tribal territory, a source of social identity. From this perspective, while ethno-tribal “outsiders” can temporarily hold certain rights to a land asset, the long-term control of the asset must always remain with the tribe. The tribe in turn retains the responsibility for providing farmland to all of its members through the powers of land allocation vested in its customary leaders.