Résumés

Abstract

In this article we examine the provision of curriculum in Nunavut between 2000 and 2013. During this time the Government of Nunavut established a mandate to ensure all curriculum from Kindergarten through Grade 12 was founded on Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit (IQ) and supported bilingualism. We describe how the Curriculum and School Services Division of the Department of Education undertook to fulfil this responsibility through unique, made-in-Nunavut curriculum development processes and products. We conclude by outlining the opportunities and challenges evident in the work of creating curriculum, teaching resources, and learning materials that centre Inuit knowledges, languages, and contexts.

Résumé

Dans cet article, nous examinons le contenu des programmes scolaires au Nunavut entre 2000 et 2013. Durant cette période, le gouvernement du Nunavut s’était donné pour mandat de s’assurer que tous les programmes, de la maternelle à la douzième année, seraient basés sur l’Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit (IQ) et qu’ils favoriseraient le bilinguisme. Nous décrivons comment la Direction des services des programmes scolaires du Département de l’éducation a entrepris d’assumer ses responsabilités au moyen d’une façon unique d’élaborer les processus et les produits des programmes. Nous concluons en soulignant les opportunités et les difficultés que l’on rencontre dans la création de programmes, de ressources d’enseignement et de matériel d’apprentissage centrés sur les savoirs, les langues et les contextes inuit.

Corps de l’article

During the 1970s, policy makers decided that adapting or developing curriculum from scratch would better fit northern contexts than imposing southern curricula. But the time, financial, and human resources necessary for curriculum development never met the needs at all levels and across all subject areas, which created a patchwork. Community members and some scholars criticized this approach as pulling teachers and students in too many, sometimes opposing, directions (Berger and Epp 2007; Aylward 2009a, 2010). Despite these growing pains, there were notable curriculum accomplishments and precedents from 2000 to 2013.

The Curriculum and School Services Division (CSS) of the Nunavut Department of Education (NDE) was adamant—even radical—about pursuing change during this period, as evidenced by hiring Elders as full-time staff, leading research on made-in-Nunavut educational philosophies, and integrating Inuit knowledge into dozens of projects. We are interested in how, when advancing new mandates for schooling centred on Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit (IQ), the NDE provided and developed new materials intended to achieve those mandates. IQ is defined by Elders as “knowledge that has been passed on to [Inuit] by our ancestors, things that we have always known, things crucial to our survival” (Bennett and Rowley 2004: xxi) or that which “embraces all aspects of traditional Inuit culture, including values, world-view, language, social organization, knowledge, life skills, perceptions and expectations” (Nunavut Social Development Council 1998). We understand the vision of educational change as the ongoing processes of creating culturally responsive schools founded on IQ and identifying and disrupting the Eurocentric approaches that otherwise characterize schools. Curriculum is only one of the many crucial areas that require system-wide transformation. In this article we describe curriculum development and implementation processes, including the intentions behind them. We conclude by discussing the ongoing opportunities and challenges of developing made-in-Nunavut curriculum and teaching materials to achieve these goals.

Curriculum is broadly conceived here, following customary use of the term in the Nunavut school system. We consider almost any tool identified as required or recommended for school programs as curriculum, including policy documents such as directives, prescribed learning competencies, approved teaching resources and student learning materials, required or recommended assessment tools, and program support manuals that outline roles, responsibilities, and pedagogies. We do not view curriculum as simply a list of what students should learn; particularly in the Nunavut context, it is not possible for teachers to make that list real in classroom teaching and learning without the associated materials and supports. While we do not provide a systematic or equivalent amount of detail on each curriculum component, they all impact student learning, and it is important to be aware of the range of responsibilities curriculum staff held from 2000 to 2013. We use the words “provide” or “provision of” curriculum to indicate that the NDE practised a combination of developing its own curriculum, and adopted (without changes) or adapted curriculum from other jurisdictions. We place emphasis on the “available curriculum” (Clements 2007) rather than the “lived curriculum” (Teitlebaum 2008), which would attempt to account for everything that students actually learn or experience in school. For example, our scope encompasses territorial-level initiatives, which do not account for locally developed programs in some communities. We are unable to address through our methods and sources the extent of teacher fidelity to mandated curriculum, although we view teacher use as an important question worthy of further research. Another reason to consider the available curriculum—rather than the lived curriculum—is that generally it has informed decisions related to setting new curriculum policy and adopting new materials.

Methodology

This article is derived from Heather’s PhD dissertation, which was aimed at understanding the decolonizing goals of the school system and related changes to educational practices that have accompanied the new Nunavut government (H. McGregor 2015). Methods included analysis of NDE documents and in-depth interviews with Catherine (Cathy) as she retired from her position as executive director of CSS, which she held from 2003 to 2013, after working in northern education since 1973. In designing and framing in-depth interviews with one educational leader, Heather drew from three areas of methodological literature: expert interviews (Bogner, Littig and Menz 2009), portraiture (Lawrence-Lightfoot and Davis 1997), and use of personal narratives in history (Maynes, Pierce and Laslett 2008). She engaged with theories of decolonizing methodologies in other Indigenous contexts to illuminate the opportunities and limitations of her methodology in understanding Qallunaat (non-Inuit)–Inuit relations. This approach included recognizing how she is implicated as a Qallunaaq researcher in this decolonizing context.

One chapter of the dissertation was revised in collaboration with Cathy for this article. Whereas the dissertation includes lengthy quotations from the interviews with Cathy and more transparency around how the knowledge claims were intersubjectively constructed through the conversations, for the sake of brevity we combine our voices into one. We hope the research benefits from the advantage of our combined perspectives, the view of an historian (Heather) and that of a practitioner who worked on many of the projects we describe (Cathy). Its most significant limitation is not including a wider range of perspectives through interviews with more staff who worked on the projects, such as Inuit educators. The dissertation outlines further detail on the research methodology, reasons for not pursuing a broader set of interviews, theorization on decolonizing initiatives in the NDE, and our respective positionalities—including our personal relationship as mother (Cathy) and daughter (Heather) alongside our professional relationship, having both worked for the NDE and on several Nunavut curriculum projects (H. McGregor 2015: 38-93).

Literature on curriculum in Nunavut

Recent literature on educational change in Nunavut with an emphasis on curriculum across the system, as opposed to projects confined to one or two communities, is limited to our own work (H. McGregor 2010, 2012a, 2012b, 2015; C. McGregor 2015) and that of M. Lynn Aylward (2007, 2009a, 2009b, 2010, 2012). Aylward suggests that to “reconceptualize and decolonize” educational practices the school system must “open everything up for negotiation [with communities], including the common understandings of cultural relevance” (2007: 6). She takes this position in response to ongoing concern that, despite rhetoric about change, only those aspects of culturally relevant education that are consistent (enough) with—or equivalent to—southern school models, may actually be adopted. Following interviews with ten experienced Inuit and non-Inuit educators about bilingual education, Aylward concludes that while teachers were making efforts to engage with the community and enact policy around bilingualism and cultural relevance, “historical assimilationist discourses of schooling were also strongly present in the Nunavut context” (2010: 319).

In another discourse analysis study Aylward (2009b) interviewed the authors who had worked on Inuuqatigiit: The Curriculum from the Inuit Perspective (NWTDE 1996), offering retrospective accounts of the development experience approximately ten years after completing the work. Using anticolonial and intercultural theoretical lenses, she found discourse models of critique, activism, and hope. She identifies implications for policy based on participant reflections, such as “how vital it is that Inuit language and culture be sanctioned within official policy and curriculum discourses of Nunavut schooling” (Aylward 2009b: 156).

More recently, Aylward argues that there is a unique “Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit Conversation” in Nunavut that centres place and consistently negotiates intercultural communication (2012: 222). She concludes that one must consider community and place as part of theorizing cultural and social differences, rather than attribute cultural differences to deficits. She says educators have begun to tackle the challenges inherent in this work and must continue to advance “culturally negotiated pedagogy that promotes the construction of schooling as a community-based initiative” (Ibid.: 227).

Ascertaining and representing the views and values of educators, as Aylward does, is important to ensuring that the process of educational change starts where educators are—addressing their questions and needs. Remaining mindful of the concerns that educators articulate about education, our article contributes evidence about departmental processes and intentions in pursuing curriculum change, hopefully adding nuance to balance the views of educators available through the work of Aylward (and others).

It is a significant challenge to fill the need for high-quality materials that not only demonstrate responsiveness to Inuit culture and language but are actually founded on Inuit knowledge. While we recognize that deep colonial structures embedded within curriculum and schooling may be difficult to completely transform “from scratch,” initiatives such as Elder research during this period were intended to create and adhere to an Inuit cultural foundation. Curriculum must also enable Nunavut students to enter university and must be comprehensive enough to replace commercially available materials. This challenge raises questions: How can competencies originating from southern / Euro-Canadian sources be appropriately blended with Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit in teaching resources and learning materials? (see also C. McGregor 2015). How should teachers combine Nunavut-developed materials with materials still sourced from other jurisdictions? Likewise, how should teachers integrate Inuktut first-language programs with English second-language programs, or vice versa, depending on the language status of students? We explain the need to develop made-in-Nunavut curriculum, the knowledge, values, and goals being pursued, and the processes associated with content development.

Curriculum before and after the NWT-Nunavut split

Provision of curriculum from 2000 to 2013 was consistent with many procedures used by the Government of the Northwest Territories prior to the creation of Nunavut. These procedures include participating in the Western and Northern Canadian Protocol (WNCP);[1] conducting research into contemporary approaches to curricula in other jurisdictions (e.g., twenty-first-century skills); involving representative teacher committees in selecting, adapting, or developing curriculum; and using a progressive feedback-loop process (research, needs assessment, development, implementation, review, revision).

There were also consistencies with Inuit regional curriculum projects prior to Nunavut. Inuuqatigiit is particularly worth noting because Nunavut curriculum development processes have been similar in several ways: establishing a philosophical base or framework for the content that draws on Inuit knowledge; consulting with Elders to collect Inuit knowledge; and producing materials in English and Inuktut.

During the 2000 to 2013 period, Nunavut was committed to developing its own curriculum to replace programs from Alberta and other jurisdictions. The Government of Nunavut mandated “re-writing of the K–12 school curriculum, to emphasize cultural relevance and academic excellence” and an education system “built in the context of Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit” (GN 1999: 6-7). Community and school consultations in 2003 supported this mandate, indicating stakeholder desire to move away from curriculum adopted from other jurisdictions and emphasize the primacy of IQ, Inuktut, and cultural relevance in Nunavut schools (Aylward 2004). Replacing Alberta programs in high school was warranted not only because of what they did not include (Inuktut and IQ) but also because their geographic, social, and cultural content was and still is unfamiliar to Nunavut students. CSS intended to design programs that provided a better bridge between what is familiar and valued by northern families with new learning competencies and unfamiliar content. Second, Alberta programs made no allowance for bilingualism or second-language pedagogy. Although Nunavut schools were not yet offering bilingual instruction in all grades, provincial programs usually had too much English vocabulary for English-language learners. Even Nunavut students who speak English as a first language may not be exposed to the range of content, concepts, and vocabulary found in southern programs. Another important factor was the persistent Eurocentrism embedded in southern curricula. Lastly, partly for these reasons, Nunavut students historically performed relatively poorly on Alberta standardized summative assessments in Grades 10 through 12. Alberta courses used assessment schemes inconsistent with Nunavut’s philosophy of teaching and learning, thus causing great concern to stakeholders, who believed either that exams should be eliminated or that students should receive better preparation for them (Aylward 2004, 2009a). The departmental response was to replace Alberta standardized exams for senior high, as alternatives could be successfully developed. For example, the Grade 12 social studies final exam was replaced with a capstone project (NDE 2013: 20).

The Nunavut Education Act and the Inuit Language Protection Act were both passed in 2008 and came into force in 2009. These laws reflected the cultural and linguistic goals that CSS had been working toward since 2000, but the new legal commitments provided additional resources for staff and project work, especially to deliver bilingual education by 2020. This facilitated support to develop school materials in one of the two officially recognized Inuit languages and English or French. CSS prioritized producing English and Inuktut materials at the same time to better reflect the two “thought worlds” of each language, rather than translate English directly into Inuktut, or vice versa. This was a slow, challenging process that required additional resources, but it was thought to bear high-quality fruit. Also, the Nunavut Education Act stipulated in numerous sections that IQ must be the foundation of all school programs. Juggling these language and cultural mandates, as well as a portfolio of responsibility larger than that of ministries in other jurisdictions (which do not develop all of their own teaching and learning materials), amongst the many other expectations of CSS staff, was ambitious and required an extensive body of work.

The elements of made-in-Nunavut curriculum that differ most substantially from those of other jurisdictions are laid out in the Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit Education Framework for NunavutCurriculum (NDE 2007) and are largely drawn from in-depth workshops with CSS’s Inuit Elder Advisory Committee. Several critical elements specific to Nunavut include strands, competencies, and continuous progress.

Strands

Rather than organizing curriculum into numerous subject areas, the NDE framed their new work within four integrated strands, intended to approximate the holistic nature of Inuit knowledge:

Nunavusiutit: heritage and culture; history; geography; environmental science; civics and economics

Iqqaqqaukkaringniq: mathematics; innovation and technology; analytical and critical thinking; solution-seeking

Aulajaaqtut: wellness and safety; physical, social, emotional and cultural wellness; goal setting; volunteerism; survival

Uqausiliriniq: communication; language; creative and artistic expression; reflective and critical thinking

These strands were not intended to be just a “mash up” of subjects but rather a distinctively conceived approach drawing on Inuit knowledge. The IQ foundation document states that this approach to learning is designed to focus on the development of complex intellectual (metacognitive) skills and lead students to transformational ways of thinking and processing … help[ing] students to understand the connections between various learnings and the strategies that lead to successful application of learning in new contexts (NDE 2007: 47).

Each strand is accompanied by a list of four to seven principles developed with Elders, such as qaujimajumaniq (curiosity) and ilittiniq tammaqtarnikkut (learning from mistakes) for iqqaqqaukkaringniq (math and technology). This approach fits well with flexible K–6 programs, whereas, at the secondary level, competencies associated with one strand could be spread across separate courses.

Competencies

Whereas most jurisdictions prescribe learning outcomes, Nunavut uses competencies. The Ilitaunnikuliriniq foundation document for assessment defines competencies as follows:

These are a set of behaviours based on the effective mobilization and use of a range of personal skills and abilities. Competencies enable students to use the learning they have acquired to understand the world around them and guide their actions. Competencies are developed over time and focus on demonstrating knowledge and ability.

NDE 2008a: 55

Emphasis here is on blending skills and knowledge to effectively navigate the demands of real life. For example, competencies in the Grade 1 My Family / Ilatka theme unit include showing respect for family members by using correct family kinship terms (CSS 2012b: 32).

Continuous Progress

The Ilitaunnikuliriniq foundation document outlines Nunavut’s assessment philosophy, which is founded on the concepts of continuous and differentiated progress. A feature of this philosophy includes “dynamic assessment … an ongoing process that involves teacher, learner and others in both setting goals and assessing progress using a range of school-based assessment tools [formative, summative, diagnostic]” (NDE 2008a: 55). Another feature is “stages of learning”:

In each learning situation, learners will be working at several different stages depending on the topic or project and their personal knowledge, experience, skills, strengths, and interests. The five transition points / stages ([emergent; transitional; communicative; confident; proficient) are like snapshots of the profile of the learner’s path along the learning continuum.

NDE 2008a: 25

In practice, the stages of learning approach means students are not advanced through one grade level in each school year, but instead they progress through the five stages of learning for each competency, whenever those milestones may occur for them (one teacher picks up where the other has left off). This approach is intended to prevent students from repeating content or being retained when some are slower than others (NDE 2008a: 27). The stages of learning approach resulted from consultation with Elders about effective teaching and learning, combined with contemporary assessment research and best practices from around the world.

Mainstream approaches to assessment have been identified as particularly ill-suited for assessing Indigenous students (Canadian Council on Learning 2009). Assessment is complicated, difficult, and controversial in nearly every educational context; Nunavut is no exception. Shifting to a Nunavut framework was difficult because most teachers had been trained in other assessment styles and teacher itinerancy rates were high. Since detailed assessment procedures had not yet been fully developed, greater in-service training was needed to encourage teachers to understand and use the approach. Therefore, made-in-Nunavut teaching resources attempted to implement this philosophy by embedding it within materials.

Curriculum in Nunavut, 2011–2012

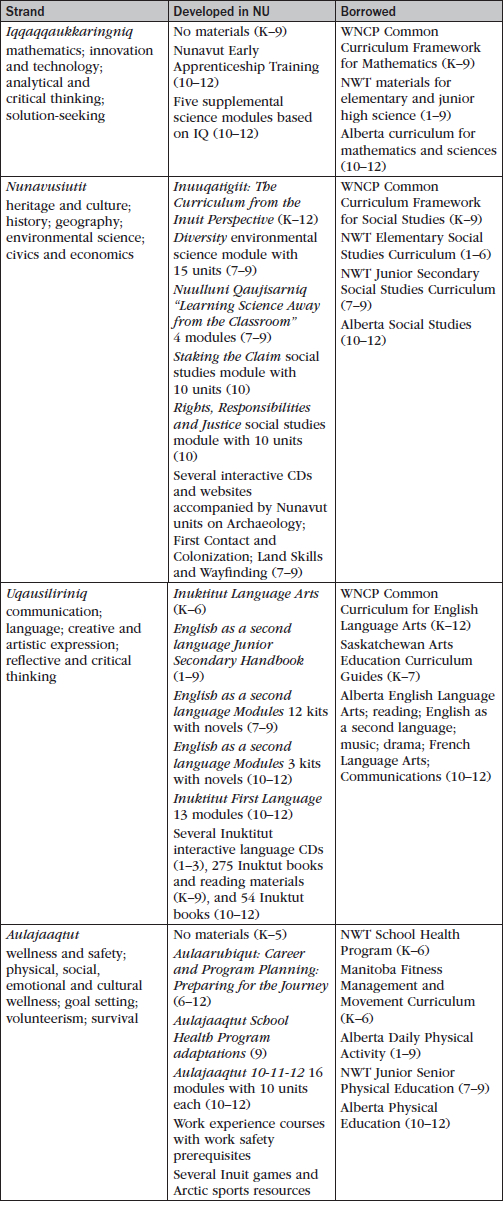

To demonstrate how Nunavut’s innovative approach evolved in the transition from borrowing to developing its own curriculum, we created a table (Table 1) based on the approved curriculum list from 2011 to 2012. The left column names the strand; the centre column shows made-in-Nunavut materials (corresponding grade levels shown in parenthesis); and the right column shows materials borrowed from WNCP, the Northwest Territories, or the provinces. The table is not exhaustive; CSS’s approved list is actually more than fifty pages long. Student learning materials often accompanied the teaching resources listed, except in the case of Inuuqatigiit.

Table 1

Curriculum and Teaching Resources Snapshot from 2011–2012

Table 1 shows that WNCP or southern provincial curricula are provided at all levels as a reference and to fill gaps between Nunavut-developed materials. It is important to note that Nunavut (and/or the Northwest Territories before) had input into all WNCP curriculum framework documents listed. Also, Alberta curriculum was not automatically adopted. NDE processes required review of new programs of any origin before adoption, based on Nunavut’s own criteria, in order to choose those that best fit their philosophy (CSS n.d.a). This explains why some programs come from Manitoba or Saskatchewan, rather than from Alberta or the Northwest Territories. Second, the table shows that Nunavut has focused on language arts, social studies, environmental studies, and wellness in developing its own materials. In our view this focus reflects the areas in which Inuit knowledge has been most accessible, and content may be more easily adapted from southern programs. Inuit knowledge also has important applications in math, technology, and senior secondary science courses (indeed, sample science resources were developed prior to 2000), but few Inuit teachers have been trained in those subject areas and for higher grade levels. Without staff who can draw on Inuit knowledge to lead curriculum development, it remains difficult to produce new courses and materials equivalent to Alberta high school programs. This equivalency is important for students seeking university entrance.

Table 1 also shows that Nunavut invested first in developing materials for secondary grades (7–12), recognizing that most development prior to Nunavut focused on Grades K–6, Inuktut instruction was already better established in elementary grades, and it was important that older students learn Inuit cultural content before they left school.

Nunavut developed teaching resources in modules, in contrast to developing all curriculum competencies through an outline document and creating teaching materials later. While this approach generated a patchwork for teachers and students to negotiate, it provided teachers with some fulsome examples. CSS took this approach intentionally because the majority of teaching staff from the South were unfamiliar with Inuktut, Inuit culture, or alternative pedagogies supported by the NDE. It was also a function of capitalizing on curriculum development opportunities that arose, as well as having staff with required expertise available to complete the work. For example, in 2012 the NDE launched a residential school history curriculum, which resulted from production assistance available from the Legacy of Hope Foundation and a partnership with the Northwest Territories government.

During this period, curriculum/teaching resource development work was underway at many grade levels, covering all four strands, but there were also large-scale initiatives related to administrative handbooks and classroom planning guides, bilingual education resources, new guidelines for high school program options and graduation requirements, work experience and apprenticeship programs, primary resources documenting IQ, student assessment tools, teacher and principal evaluation tools, literacy initiatives, and student support/inclusive education procedures.

The number and variety of materials under development demonstrates the comprehensive demands on the school system and the NDE’s responsibility to address those demands. Some initiatives may seem unrelated to curriculum, but they represent concerns relevant to principals and teachers, and they impact the ability of school staff to implement curriculum. They have all been essential to creating a school system specific to Nunavut, rather than a reflection of southern systems. With the NDE’s goal that departmental staff contribute to shaping all programming (not just curriculum competencies), there has been very little going on in schools that curriculum staff could disregard.

Curriculum development processes

The NDE established a comprehensive curriculum development plan in 2000 with ambitious implementation timelines. The plan was used as a guide, but it did not anticipate or account for the complexity of the work involved. For example, curriculum positions—like other government positions—were often slow to be staffed or remained vacant (North Sky Consulting Group 2009: 42; Varga 2014). Outside influences, such as government departments pressuring the education system to deliver particular outcomes, also affected project priorities and choices.

CSS leadership during this period came from long-term Inuit and Qallunaat educators who were knowledgeable about Indigenous educational change and committed to the vision of made-in-Nunavut curriculum. They led processes that depended on building partnerships, hiring and coordinating fifty-two staff in six communities across Nunavut (by 2013), managing up to thirty contractors, publishing documents, training principals, in-servicing teachers, briefing senior management, and solving problems. CSS staff members who coordinated and wrote new curriculum were also, for the most part, experienced and committed long-term educators, both Inuit and Qallunaat. Generally, however, project staff did not have previous department-level experience and required orientation, training, professional development, team building, and mentorship to complete effective work in multiple languages. From our experience, the ethic of CSS was to build respectful, collaborative relationships between Inuit and Qallunaat staff on an ongoing basis, but how other staff experienced that intention is a question worthy of further study.

The curriculum development process required original research, seldom undertaken before and complicated by the cross-cultural and epistemologically divergent context of Nunavut. The criticism that Nunavut could not develop materials fast enough (Auditor General of Canada 2013) might be explained by the extent of the work underway. And yet, how could anyone know the time required for such unprecedented work? How could human resource needs be accurately estimated, when most staff were new to these responsibilities, and when there were few pre-existing guidelines for the work expected? The curriculum context and goals described above should convey the breadth and depth of projects undertaken, particularly the goal that new teaching materials would ideally offer teachers everything they needed: direction, competencies, teaching resources, learning materials, and assessment and differentiation supports. CSS expected teachers might adapt this material for their particular students, but part of the rationale for such detail was to make it less likely that teachers revert to using Eurocentric approaches. The intention was also to address the frustration teachers often expressed that they did not have enough relevant materials and were not trained well enough to fulfil Nunavut’s different pedagogical mandates (Aylward 2004, 2009a; Berger and Epp 2007).

In our view, the NDE demonstrated a particular approach to change: that curriculum renewal involved transformation of the system to meet Nunavut-based desires and needs, and necessarily involved tackling many components at one time. It was not a matter of simply or superficially “tweaking” components here and there. Given all these factors, it was not possible to stick to one curriculum development plan.

The following description of how CSS carried out projects is based on the Project Outline template (CSS 2012a) used by curriculum coordinators, and accompanied by guidelines for Consultation / Piloting, Curriculum / Program Actualization Process, Standard Formats, and In-Service. The template and guidelines were organic; versions were refined over time based on experience. We focus on the high-level steps and expectations involved, detailing these procedures to gain greater insight into the unique ways Nunavut tailored them.

The Project Outline requested a project description, goals, and anticipated measurable outcomes. Next, the project’s relationship to Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit, and the other foundation documents (dynamic assessment and inclusive education), was defined. Coordinators were directed to consult with Inuit educators and Elders to complete this section. This consultation was intentionally carried out prior to referencing curriculum approaches from other jurisdictions so as to establish an IQ basis. Curriculum actualization guidelines (CSS 2013) also required further Elder consultation for cultural content research and to review draft materials.

Each project had to be framed in relation to bilingual education, and how it affected language of instruction models, and language pedagogy, staffing, or resources (CSS 2012b: 2). Then, the coordinator indicated what general improvements the project offered for student learning, and if and how it affected graduation requirements. A jurisdictional scan, which prioritized current practice in similar Indigenous contexts, was also required. In most cases, this scan was to provide reinforcement for approaches developed in consultation with Inuit Elders, not for exemplars to borrow or emulate.

The Project Outline illustrated the many necessary steps for each project: needs assessment, literature search, cultural research, development, piloting, editing, publication preparation, in-service and training, ongoing implementation after the training, and communications. Coordinators set timelines, estimated costs for each budget year, and identified responsibilities. They then worked with colleagues and partners to oversee each stage.

Curriculum research and consultation

From 2000 to 2013, Nunavut set a standard for project consultation by establishing an educator working group to inform each project. Some committees were struck temporarily for specific initiatives, while others were standing committees. In projects that required public engagement, curriculum coordinators supplemented committee input by holding focus groups, kitchen table consultations, public meetings, or expert interviews. For example, widespread consultations took place on new high school program pathways and graduation requirements, given the extent to which outcomes would affect students and be of interest to parents and the public.

Engaging classroom teachers in territorial curriculum development supported the production of materials that reflected classroom realities. Such engagement also decreased isolation by giving educators opportunities to communicate and collaborate with colleagues. The intent was to offer professional development by helping teachers understand different pedagogical approaches and how to implement new curriculum. CSS expected participation in such committees would nurture educators’ commitment to, and ownership of, the vision of a made-in-Nunavut school system.

Curriculum development was intended to draw on traditional Inuit, contemporary Inuit, and contemporary Qallunaat knowledges, and engage students in applying those differing knowledges in their lives. For example, Grades 10–12 Aulajaaqtut (wellness program) addresses how expectations for children and youth differ between Inuit parents long ago and parents today.

The extent to which Inuit and non-Inuit perspectives are noted or compared explicitly varies widely. Specific references to the sources of generalizations about Inuit knowledge or culture are often missing. Even for experienced curriculum developers, it is challenging to incorporate Elder perspectives accurately, respectfully, and effectively. It is difficult to ensure that Inuit perspectives are gathered, heard, and incorporated into each topic—and not overruled or subsumed by Qallunaat views. Further analysis of the process and results of blending Inuit sources with Qallunaat sources in curriculum, detailed in Heather’s dissertation, shows that this challenge may deserve greater critical review and evaluation within CSS.

Curriculum layout

Materials developed during this time period were laid out in a consistent format and logic. For example, the My Family / Ilatka Grade 1 module (CSS 2012b) contains detailed components that would not typically be found in curricula elsewhere. These components include supports such as extensive teacher background material, actual teaching units with all student learning activities and assessments, and how to accommodate second-language learners and students who require extra supports. The handbook for the My Family / Ilatka theme unit is 230 colour pages, published in English and Inuktitut. The kit accompanying the handbook includes a variety of games, books, films, posters, and toys, in both languages. The materials illustrate traditional and contemporary content using images of Inuit families. Some might consider this made-in-Nunavut unit overproduced, duplicating information from foundation documents and other curriculum guidelines. This repetition is intentional: it addresses teacher and principal itinerancy and lack of familiarity with Nunavut philosophy and direction, as well as the common issue of materials getting lost in schools.

This example was developed and produced in Nunavut and is an exceptional instance of NDE capacity to provide culturally responsive and exciting, multifaceted materials. But it was a highly resource-intensive project. Rather than demonstrating what all made-in-Nunavut teaching units will include, it is better described as a model unit that guides teachers as they develop materials to cover other topics.

Curriculum approvals

Curriculum provided to Nunavut schools required an approval process by senior CSS and NDE staff. Review criteria included how appropriate the content was for Nunavut, as well as general quality and fit with evidence-based research on current educational practices (CSS n.d.a). During most of this period, the deputy minister of education, Kathy Okpik, an Inuk educator fluent in Inuktitut, reviewed and edited documents for policy and content as well as Inuktitut grammar and orthography. Without a larger complement of staff to review and approve materials, especially for multilingual and cultural components, this process was time-consuming. The minister of education also approved materials if they proposed changes to graduation requirements. Projects that affected other departments required review by the justice and government affairs departments and the cabinet, adding to already complicated and lengthy processes.

Curriculum implementation and in-service

School-level implementation of made-in-Nunavut curriculum and resources from elsewhere was generally the responsibility of elementary, secondary, and Inuktut program consultants in three Regional School Operations offices located across Nunavut. However, CSS coordinators for each project usually led development of the required in-service outline and implementation “kits.” They facilitated in-service for the regional program consultants, who then fanned out to schools to adapt and deliver the in-service in twenty-five communities. CSS viewed co-development and facilitation of curriculum in-service with regional staff as another capacity-building initiative, similar to having teachers serve on curriculum committees (CSS n.d.b: 2-3). CSS used in-services as opportunities to (re)familiarize participants with Nunavut foundations and philosophies of education (CSS n.d.b: 4) and to provide pedagogical guidance. In-services consistently modelled the integration of IQ, Elder participation, or other community-based activities, including informing parents of the new materials, with this same goal in mind. All school staff participated in some in-services to better understand the context in which they were teaching and the legacies of colonizing relations between Inuit and Qallunaat. The residential school unit was one such topic (NDE and NWTDE 2013).

Nunavut in-service was a challenging undertaking. In-service days were limited to one or two training initiatives per year. Sometimes new materials were approved but could not be implemented until an in-service timeslot was available the following year. Other times English materials were ready for in-service, but Inuktut materials had not yet been completed because fewer staff were available to develop, edit, and finalize products. The NDE was reluctant to release English materials without Inuktut, given their commitments and responsibilities to bilingual education. Scheduling could be difficult, given the challenges of Arctic travel. It was nearly impossible to provide ongoing orientation, training, and in-service to teachers arriving after the initial training and implementation, or to those who required more supports. The NDE was keenly aware of this problem and was seeking solutions, such as involving school staff in leading in-service sessions and leaving an in-service kit at each school (CSS n.d. b: 3).

Curriculum evaluation

The NDE did not have a consistent process for curriculum review and evaluation during this period. Beyond expectations for evaluation that are relatively standard in most educational jurisdictions, the Nunavut Education Act requires that school programs reflect Inuit knowledge. As we have shown, this is not simply a matter of sprinkling Inuit perspectives into materials; the many complexities in sourcing, framing, contextualizing, interpreting, and teaching Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit content on its own, and always in relation to Eurocentric epistemological and ontological influences, continue to be pervasive in Nunavut schools.

Curriculum quality is often evaluated in other school systems by comparing it to curricula from other places, or with external bodies of codified knowledge such as an academic discipline (i.e., comparing math curriculum to university-based math research). Complexity arises for Nunavut because such sources largely do not exist for Inuit knowledge, which cannot be appropriately or logically compared to key ideas in curricula from other jurisdictions. Ideally, Inuit knowledge in curriculum should be measured against Inuit knowledge documented or held by Inuit—or approached on its own terms. This method would also help to reduce the impact of Eurocentrism, which has been perpetually saturating schools—whether overtly or not (Berger 2009). “Peer review” or knowledge verification processes in Inuit society may look substantially different from approaches in academic or institutional contexts. An Elder committee was being struck at the end of this period to discuss these issues.

In looking at examples of Nunavut-developed curriculum during this period, it is clear that substantial efforts were made to incorporate Inuit knowledge, Inuit identity, IQ principles, and Inuit stories. However, our review showed teachers and students were not often explicitly asked to think critically about the sources of knowledge they encountered, the author’s point of view, what types of knowledge were produced by differing sources, or how they related to each other. For example, attribution to an author or individual was sometimes missing from Inuit stories or Elder knowledge. Without consistent indication of authorship, one cannot assess the accuracy, utility, or credibility of knowledge, whether it is held and attributed individually or collectively.

Until such time as a formal, documented, or cumulative knowledge gathering/validating process is developed for Inuit knowledge, educators must proceed with making their own judgments about the quality of Inuit curriculum content. If non-Inuit staff who do not speak Inuktut and who were not raised or educated in Inuit culture are conducting evaluations, how can they judge what constitutes “trustworthiness,” “accuracy,” and “respect” when it comes to Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit? What commentary should curriculum writers provide to teachers and students about differences in how knowledge is constructed and deemed trustworthy between Inuit- and European-derived knowledges? A venue is needed to consider such deep, underlying questions.

In addition, evaluation should address how students actually learn from the materials. A comprehensive evaluation would ideally develop criteria with stakeholders and account for cultural complexity and local conditions. Curriculum must be provided in ways that offer guidance, address local variability, are responsive to changing contexts, and respect teacher autonomy. This requirement must be carefully balanced with the need for Nunavut teachers to be well prepared to instruct curriculum that they themselves may not have learned or been trained in, and that may ask them to work outside their own views, comfort zones, or values.

Conclusion

This article has looked for and at the principles, procedures, and products of curriculum provision in Nunavut from 2000 to 2013. Nunavut is the only public school jurisdiction in Canada that requires delivery of all school programs in the context of an Indigenous knowledge system, and bilingually with Indigenous languages. Nevertheless, research into curriculum change processes remains scarce (ITK 2011).

Nunavut curriculum developers have experience working toward re-conceptualizing a school system, with the support of their electorate, to better facilitate Indigenous self-determination. And yet, many of the same challenges faced in other jurisdictions remain in Nunavut: justifying the incorporation of Indigenous knowledge; documenting Indigenous knowledge and integrating it with European-derived content in institutions with assimilative legacies; and mediating the inevitable conflicts inherent in this work, especially teacher training and support. Space limitations prevent a longer analysis of commonalities with other Indigenous peoples (as briefly outlined in McGregor 2015: 214-15), such as the work of Jo-Ann Archibald (1995, 2008) and Yatta Kanu (2011). There are few Canadian researchers illustrating from beginning to end how Indigenous curriculum is sourced, designed, and actualized. In addition to offering a model for that kind of inquiry, we have constructed this article to address the possible loss of institutional memory at the NDE as long-term staff leave or retire and as policy directions shift.

In summary, the opportunities associated with Nunavut developing its own curriculum, in our view, facilitated transformation of the school system from within and provided for the realization of the goals and values for Nunavut schools as articulated in the Nunavut Education Act, Inuit Language Protection Act, Nunavut Settlement Agreement, and calls from Inuit parents. The provision of defined, robust, well-resourced Nunavut curriculum development processes is crucial to strengthening system-wide IQ foundations and bilingual approaches that nurture innovation in educational structures, facilitate greater consistency across communities, and allow students and parents to see themselves in the school system. These opportunities include

integrating Nunavut beliefs, values, culture, and history;

building on the strengths, learning styles, and characteristics of Inuit students;

influencing pedagogy based on what works in Nunavut, from experience;

involving parents, district education authorities, Elders, and community members; and

ensuring high expectations for learning competencies that reflect IQ and Western knowledges.

Established curriculum processes ease what is otherwise very difficult work when done in piecemeal projects, or undertaken on a community-by-community basis, or left to individual Inuit educators, as it has been in the past.

Some of these outcomes can already be seen—at least as available curriculum—in the materials developed since 2000. What goes on in classrooms, school hallways, and the diverse activities of schooling across Nunavut, and whether practice has anything to do with recommended curriculum, is another question to investigate. Complaints that teachers cannot find NDE resources are a hint that more work is required to implement curriculum, to follow up, to provide support, and to hold schools accountable (CSS 2008). We have not addressed how teachers actually use the materials when they are available, an issue that other researchers have found to be problematic in Indigenous education (Dion 2009). In addition, we have not focused here on the important role of school leaders in promoting and supporting curriculum change. We have detailed in-service procedures to demonstrate some of the ways the NDE attempted to address these well-known challenges.

During this period, there were also numerous difficulties in developing curriculum in Nunavut. Challenges partially came from the need to provide teaching resources before the full scope and sequence of curriculum competencies had been completed at each grade level, in each strand, or in each subject area. As a result, developers sometimes had to work with learning outcomes identified in the Northwest Territories or other western provinces. It was difficult to determine an appropriate combination of made-in-Nunavut units with materials borrowed from other jurisdictions. Also, so much energy was devoted to development and in-servicing that very little program evaluation occurred. Therefore, efforts to determine the worth of new or revised materials were not based on systematically collected evidence.

The barriers from this period to bringing IQ curriculum into the school system largely have to do with human resource capacity to develop or implement the materials created in Nunavut. As we have noted, only a small number of educators have both Inuktut skills and interest in doing this work. Hiring these staff at CSS depleted the number of Inuit teachers in classrooms. Curriculum development positions were located in specific communities, so only Inuit educators living there or willing to relocate formed the pool of available staff. Lack of staff housing often delayed hiring, and CSS competed for experienced Inuit educators with other government departments. While we do not cover this issue in as much detail, another barrier was the potentially limited ability of most teachers to teach Inuit content without resource-intensive training. The teachers lacked training, either because they were Qallunaat who only had a few years of experience teaching at all or specifically in Nunavut, or because they were Inuit whose opportunities to learn Inuit knowledge had been interrupted in the past by the requirement to attend the Eurocentric school system. Targeted educator professional development and pedagogical supports were consistently needed to accompany, enhance, and fulfil curriculum implementation initiatives.

Despite these challenges, there were significant accomplishments in curriculum development and reform during this period. While developing classroom-ready materials, Nunavut advanced and practised its layered philosophy of education through in-service and training. The work of moving toward curriculum founded on an IQ framework was ground breaking in mobilizing Indigenous knowledge in a public school system. The rationale and approaches used by curriculum staff were transformative through their foundations in Elder knowledge, their incorporation of the long-term experience of educators, and their efforts to advance a critique of, and provide an alternative to, the materials used by the Northwest Territories and other jurisdictions. These critiques and alternatives were informed by imperatives for student competencies established between curriculum and school staff, some broader consultations, as well as legal commitments to advancing IQ and Inuktut in schools.

Observers of the Nunavut school system ask why curriculum change has taken so long. The 2013 Auditor General’s report found that the Department of Education had developed only 50 per cent of the teaching resources required for the system in ten years and therefore should institute a new approach to resource development (16). In 2006 Justice Thomas Berger notably recommended a large investment of targeted funding from the territorial and federal governments to achieve Nunavut’s bilingual education goals and support greater Inuit employment, but the federal government never addressed this recommendation. We have tried to demonstrate through this article that money would not solve all of Nunavut’s curriculum challenges, although it would not hurt. What was desired—and arguably necessary—to enact the NDE mandate was a larger cadre of staff with experience and knowledge about Nunavut, especially Inuit cultural knowledge and language. It was difficult for the NDE to hire Inuit staff with strong language and culture skills because it left fewer bilingual teachers in classrooms with students. Nunavut’s greatest curriculum difficulty originated from making ambitious commitments that no organization could realistically meet within the suggested timelines, let alone one burdened heavily by capacity issues. Educators in Nunavut thus grapple with a paradox: on the one hand, there is no time to waste in better supporting Nunavut youth to develop the cultural identity and contemporary competencies required to have choices in their future; on the other hand, more time is needed to bring about the significant system transformation that may achieve this radical vision.

Parties annexes

Note

-

[1]

WNCP was established in 1993 as a consortium of western provinces and territories. Nunavut joined in 2000 and British Columbia participated until 2009. The jurisdictions worked together to develop subject area curriculum frameworks. Collaboration meant having a sufficiently large student population to make it worthwhile for publishers to develop specific texts to meet their needs. WNCP has since been disbanded.

References

- ARCHIBALD, Jo-Ann, 1995 “Locally Developed Native Studies Curriculum: An Historical and Philosophical Rationale”. In Marie Battiste and Jean Barman (ed.), First Nations Education in Canada: The Circle Unfolds, p. 288-312. Vancouver, UBC Press.

- ARCHIBALD, Jo-Ann, 2008 Indigenous Storywork: Educating the Heart, Mind, Body, and Spirit. Vancouver, UBC Press.

- AUDITOR GENERAL OF CANADA, 2013 Report of the Auditor General of Canada to the Legislative Assembly of Nunavut: Education in Nunavut. Ottawa, Ministry of Public Works and Government Services.

- AYLWARD, M. Lynn, 2004 Executive Summary of Sivuniksamut Ilinniarniq Consultations. Iqaluit, Nunavut Department of Education.

- AYLWARD, M. Lynn, 2007 “Discourses of Cultural Relevance in Nunavut Schooling”, Journal of Research in Rural Education, 22 (7): 1-9.

- AYLWARD, M. Lynn, 2009a “Culturally Relevant Schooling in Nunavut: Views of Secondary School Educators”, Études Inuit Studies, 33 (1-2): 77-94.

- AYLWARD, M. Lynn, 2009b “Journey to Inuuqatigiit: Curriculum Development for Nunavut Education”, Diaspora, Indigenous, and Minority Education, 3 (3): 137-158.

- AYLWARD, M. Lynn, 2010 “The Role of Inuit Languages in Nunavut Schooling: Nunavut Teachers Talk about Bilingual Education”, Canadian Journal of Education, 33 (2): 295-328.

- AYLWARD, M. Lynn, 2012 “The Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit Conversation: The Language and Culture of Schooling in the Nunavut territory of Canada”. In Z. Bekerman and T. Geisen (ed.), International Handbook of Migration, Minorities and Education: Understanding Cultural and Social Differences in Processes of Learning, p. 213-229. Dordrecht, Springer Netherlands.

- BENNETT, John, and Susan ROWLEY, 2004 Uqalurait: An Oral History of Nunavut. Montreal and Kingston, McGill-Queen’s University Press.

- BERGER, Paul, 2009 “Eurocentric Roadblocks to School Change in Nunavut”, Études Inuit Studies, 33 (1-2): 55-76.

- BERGER, Paul, and Juanita R. EPP., 2007 “‘There’s No Book and There’s No Guide’: The Expressed Needs of Qallunaat Educators in Nunavut”, Brock Education, 16 (2): 44-56.

- BERGER, Thomas R., 2006 The Nunavut Project: Conciliator’s Final Report: Nunavut Land Claims Agreement: Implementation Contract Negotiations for the Second Planning Period, 2003–2013. Vancouver, Bull, Housser and Tupper.

- BOGNER, Alexander, Beate LITTIG, and Wolfgang MENZ (ed.), 2009 Interviewing Experts. New York, Palgrave Macmillan.

- CURRICULUM SCHOOL SERVICES (CSS), n.d. a CSS Document Review Criteria. Iqaluit, Nunavut Department of Education.

- CURRICULUM SCHOOL SERVICES (CSS), n.d. b In-Service Process (Guidelines for Curriculum). Iqaluit, Nunavut Department of Education.

- CURRICULUM SCHOOL SERVICES (CSS), 2008 Curriculum, Teaching and Learning Resources Study. Iqaluit, Department of Education.

- CURRICULUM SCHOOL SERVICES (CSS), 2012a CSS Project Outline. Iqaluit, Nunavut Department of Education.

- CURRICULUM SCHOOL SERVICES (CSS), 2012b My Family / Ilatka: A Grade 1 Theme Unit. Iqaluit, Nunavut Department of Education.

- CURRICULUM SCHOOL SERVICES (CSS), 2013 The Curriculum / Program Actualization Process. Iqaluit, Nunavut Department of Education.

- CANADIAN COUNCIL ON LEARNING, 2009 The State of Aboriginal Learning in Canada: A Holistic Approach to Measuring Success. Ottawa, Canadian Council on Learning.

- CLEMENTS, Douglas H., 2007 “Curriculum Research: Toward a Framework for Research-Based Curricula”, Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 38 (1): 35-70.

- DION, Susan D., 2009 Braiding Histories: Learning from Aboriginal Peoples’ Experiences and Perspectives. Vancouver, UBC Press.

- GOVERNMENT OF NUNAVUT, 1999 Pinasuaqtavut: The Bathurst Mandate. Iqaluit, Government of Nunavut.

- GOVERNMENT OF NUNAVUT, 2008 Nunavut Education Act. Iqaluit, Government of Nunavut.

- INUIT TAPIRIIT KANATAMI, 2011 First Canadians, Canadians First: National Strategy on Inuit Education 2011. Ottawa, Published for the National Committee on Inuit Education by Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami.

- KANU, Yatta, 2011 Integrating Aboriginal Perspectives into the School Curriculum: Purposes, Possibilities, and Challenges. Toronto, University of Toronto Press.

- LAWRENCE-LIGHTFOOT, Sara, and Jessica Hoffman DAVIS, 1997 The Art and Science of Portraiture. San Francisco, Jossey-Bass, A Wiley Imprint.

- MAYNES, Mary Jo, Jennifer L. PIERCE, and Barbara LASLETT, 2008 Telling Stories: The Use of Personal Narratives in the Social Sciences and History. Ithaca and London, Cornell University Press.

- McGREGOR, Catherine A., 2015 “Creating Able Human Beings: Social Studies Curriculum in the Northwest Territories and Nunavut”, 1969 to the Present, Historical Studies in Education, 27 (1): 57-79.

- McGREGOR, Heather E., 2010 Inuit Education and Schools in the Eastern Arctic. Vancouver, UBC Press.

- McGREGOR, Heather E., 2012a “Curriculum Change in Nunavut: Towards Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit”, McGill Journal of Education, 47 (3): 285-302.

- McGREGOR, Heather E., 2012b “Nunavut’s Education Act: Education, Legislation and Change in the Arctic”, The Northern Review, 36 (Fall): 27-52.

- McGREGOR, Heather E., 2015 Decolonizing the Nunavut School System: Stories in a River of Time. PhD Dissertation in Education. Vancouver, University of British Columbia.

- NUNAVUT DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION, 2007 Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit: Education Framework for Nunavut Curriculum. Iqaluit, Curriculum and School Services Division.

- NUNAVUT DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION, 2008 Ilitaunnikuliriniq: Foundation for Dynamic Assessment as Learning. Iqaluit, Curriculum and School Services Division.

- NUNAVUT DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION, 2009 Staking the Claim: Dreams, Democracy and Canadian Inuit [teachers’ guide]. Iqaluit, Nunavut Department of Education.

- NUNAVUT DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION, 2013 Annual Report, 2010–2012. Iqaluit, Nunavut Department of Education.

- NUNAVUT DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION and NORTHWEST TERRITORIES DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION, CULTURE AND EMPLOYMENT, 2013 The Residential School System in Canada: Understanding the Past – Seeking Reconciliation – Building Hope for Tomorrow. Ottawa, Legacy of Hope Foundation.

- NORTH SKY CONSULTING GROUP, 2009 Qanukkanniq?: The GN Report Card: Analysis and Recommendations. Iqaluit, North Sky Consulting Group.

- NUNAVUT SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT COUNCIL, 1998 Report on the Nunavut Traditional Knowledge Conference. Igloolik, Nunavut Tunngavik Incorporated.

- NORTHWEST TERRITORIES DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION, 1996 Inuuqatigiit: The Curriculum from the Inuit Perspective. Yellowknife, Government of the Northwest Territories.

- TEITLEBAUM, Kenneth, 2008 “Curriculum”. In Sandra Mathison and E. Wayne Ross (ed.), Battleground Schools: An Encyclopedia of Controversial Issues in Education, p. 168-177. New York, Greenwood Press.

- VARGA, Peter, 2014 “Nunavut’s Poor Education Record Due to ‘Lack of capacity’, School Boss Says”, Nunatsiaq News, April 3.

Liste des tableaux

Table 1

Curriculum and Teaching Resources Snapshot from 2011–2012

10.7202/1014860ar

10.7202/1014860ar