Résumés

Abstract

Since the adoption of the sustainable development policy in 2006, a strategic vision is now required for planning proceedings in Quebec, especially for Regional County Municipalities (RCMs) in charge of a supra-municipal Schéma d’aménagement et de développement (SAD). Focusing on the renewal proceedings of the SAD of Rivière-du-Loup’s RCM between 2009 and 2013, this research analyzes the process of shaping such a strategic vision, and the place of this vision in the management of a sub-regional governance. During that four-year period, this RCM led a sub-regional coalition of both public and private actors in a cross-cutting and joined-up process called Vision 2031. This process involved more than experts and decision-makers; it opened its future-oriented process to the wider civil society. This was significant for three reasons. First, it expressed a shift from the retrospective to more forward-looking knowledge building. Second, it translated a switch from sectoral planning to cross-cutting planning. Third, it represented an on-going process towards more collaborative ways of proceeding. Territorialization and horizontalization of spatial planning policies constitute a same process; it implies that responsibility for development stems not only from decision-makers but from the entire sub-regional community. In other words, in a context of challenging public institutions’ political capacity and crisis of top-down model of management, such new spatial foresight proceedings highlight the emergence of a new type of sub-regional public regulation – a governance by the future.

Keywords:

- Governance,

- Foresight,

- Strategic spatial planning,

- Planning,

- Quebec,

- Regional County Municipality

Résumé

Depuis l’adoption de la stratégie générale de développement durable en 2006, l’élaboration d’une vision stratégique pour l’aménagement du territoire est désormais obligatoire au Québec, notamment pour les Municipalités Régionales de Comtés (MRC), chargées de la rédaction d’un Schéma d’aménagement et de développement (SAD) supra-municipal. En se focalisant sur le processus de réactualisation du SAD de la MRC de Rivière-du-Loup entre 2009 et 2013, cette recherche analyse le processus de formation d’une telle vision stratégique et la place de cette vision dans la gestion d’une gouvernance infra-régionale. Durant ces quatre années, cette MRC a en effet coordonné une coalition infra-régionale réunissant des acteurs publics et privés dans une démarche transversale et intégrée, labellisée Vision 2031. Cette démarche a pour particularité d’avoir ouvert le processus décisionnel à la société civile, en plus des habituels experts et décideurs du territoire. Ceci caractérise trois évolutions majeures. Premièrement, un tel projet traduit une évolution vers une planification davantage prospective, c’est-à-dire tournée vers l’avenir. Deuxièmement, cela caractérise également le passage d’une planification sectorielle à une planification plus transversale. Troisièmement, cela exprime la recherche de pratiques planificatrices plus collaboratives. La territorialisation et l’horizontalisation des politiques d’aménagement du territoire constituent ainsi un même processus. Cela implique que la responsabilité du développement incombe non plus seulement aux traditionnels décideurs, mais à l’ensemble de la communauté territoriale. A un moment où les institutions publiques voient leurs marges d’actions fragilisées et dans un contexte de remise en cause des modèles hiérarchiques d’action publique, ces nouvelles démarches de prospective territoriale soulignent l’émergence d’un nouveau mode de régulation publique infrarégional : une gouvernance par le futur.

Mots-clés :

- Gouvernance,

- Prospective,

- Planification stratégique spatialisée,

- Aménagement du territoire,

- Québec,

- Municipalité Régionale de Comté

Corps de l’article

Introduction

Nowadays, the production of forward-looking knowledge and narratives is commonly used in policy processes in Europe and Canada (Lavallée, 2001; Rio, 2015; Petit Jean, 2016; Lardon & Noucher, 2016; Le Berre, 2017), especially in planning, and more particularly through the growing practice of strategic spatial planning (Böhme, 2002; Motte, 2006; Proulx, 2008). In Quebec, spatial forecasts and foresight exercises have flourished at the provincial, regional, and local levels since passage of the Sustainable Development Act in 2006. This recent interest for spatial anticipation – what is called “la prospective territoriale” in France (Durance, Godet, Mirénowicz, & Pacini, 2007) – brings to light a technique of forward-looking expertise born at the end of the World War II to better prepare spatial and economic planning (Guiader, 2008; Andersson, 2012). This kind of foreknowledge is supposed to be a decision-support tool for making strategic options in the field of economic planning, leading to the formulation of a spatial vision. It suggests developing different scenarios of the future, based on local strengths and weaknesses, which are then used to shape a vision of development that is shared among economic and political actors of the territory (Gouvernement du Québec, 2010, p.8).

This paper focuses on an original spatial foresight exercise called Vision 2031 driven by the Regional County Municipality (RCM)[1] of Rivière-du-Loup, Quebec, between 2009 and 2013. The goal here is not to draw a general portrait of planning in Quebec but to describe a case, distinct in some aspects, but taking a part of a general context of politics[2] and reflecting some changes in planning in Quebec. During those four years, this RCM led a regional coalition that gathered institutions and citizens in a cross-cutting and joined-up process to shape a vision for the future development of its territory. Through horizon scanning and foresight, the RCM of Rivière-du-Loup monitored and explored social, economic, environmental, and technological changes in its area (MRC de Rivière du Loup, 2013a). That Vision 2031 included more than economic experts, statisticians, and sectoral advisers, opening its visioning process to the greater civil society, seems to express a shift from sectoral and top-down planning to a more spatialized and relational planning, what Healey calls “collaborative planning” or “communicative planning” (Healey, 1993, 1997). With this in mind, the study of such a process of future visioning, and the implementation of a future-oriented strategy in planning policies, aims for a better understanding of the processes and effects of spatial foresight in the planning process. In doing so, the hope is to understand the link between future-telling, planning, and governing.

Theoretically, this paper articulates a neoinstitutionalist approach of governance, with a cognitive approach toward public policy instruments. First, the study combines both historical and sociological neoinstitutionalism (Hall & Taylor, 1997; Gazibo & Jenson, 2015, pp. 186-196). The historical perspective helps to understand how and why the RCM has developed future-oriented narratives, and the effects this institutionalization has had on discourses and practices. The sociological perspective helps to understand how these narratives provide frameworks of meaning and models of action on which actors can act. The aim is, above all, to study future-oriented narratives as instrumental mechanisms of institutionalization and political capacity building for regional spaces. Second, with regard to this process, political capacity is not limited to an institutional dimension; it also has a cognitive and discursive dimension (Pasquier, 2012, p. 42). By analyzing foreknowledge as political story telling, stress is placed on the politics of meaning because discourses themselves are forms of action, and not only the ornaments of politics and social behaviours (Fischer, 2012, p. Viii). Indeed, any anticipation has an utterance dimension; it involves a rhetorization of reality (Faure, 2011, p. 77) and confers an order of meaning (Fischer, 2012) on both the present actions of local actors and the indeterminate horizon of the future.

Methodologically speaking, this research combines a document and literature review and semi-structured interviews. It focuses on the process of shaping such discourses and their place in the management of a regional governance by analyzing planning, strategic and communication documents of the RCM, in addition to several semi-structured interviews in the RCM of Rivière-du-Loup, the Government of Quebec, and other regional institutions engaged in such forward-looking exercises. This survey was conducted during a stay in Quebec from August 2013 to December 2013. The first step consisted of gaining a better understanding of the regional history of planning and future-oriented expertise in RCMs. The second step was a discursive analysis of the collected documents and speeches, to identify a variety of forward-looking narratives, and their evolution and implementation.

1. The Regional County Municipality: An Intermediate Level of Planning

The creation of the RCM scale is the result of three dynamics: a need for regional planning resulting from the crisis of the mid-1970s, a loss of efficiency of the top-down planning approach (Proulx, 1996; Sokoloff, 1984), and a movement toward decentralization and regionalization (Gouvernement du Québec, 1983a). Regarding the planning process, the RCM’s mission is to build and coordinate a supra-municipal coalition to foster local development. With regards to the forecasting and visioning process, RCMs did not quickly invest their potential for being a pertinent level of anticipation for planning, but have progressively developed this capacity since the mid-2000s.

1.1 A Knowledge Production Scale for Planning, Born Between Devolution and Rationalization

Upon passage of the Land Use Planning and Development Act (1979), the RCM system was introduced in 1980-1981, replacing the county system in effect since 1855. There was a dual context to this. First, in 1975, Quebec was struck by the negative economic repercussions of the global hydrocarbon crisis. The dynamic of unemployment, particularly significant in peripheral regions, highlighted the weakness of the hierarchical and centralized nature of the planning model established during the Quiet Revolution, and reinforced local-peripheral protests against provincial centralization. The late 1970s and early 1980s match in Quebec the end of the Keynesian top-down development model; that is to say, an “agenda building” on decentralization of the planning and policy making process (Lévesque, 1981). Second, while the economic crisis helped strengthen regionalist mobilization at the local level, it also stirred up sovereignist tendencies at the provincial level, led by the sovereignist Parti Québécois, in power since 1976. If peripheral regions estimated that the crisis was the result of an overly centralized policy-making process, the provincial government argued that it was a result of insufficient autonomy within the confederation. So, on the one hand, the birth of the RCMs stemmed from a decentralization agenda, but on the other hand, it also stemmed from a sovereignist agenda.

“Spatial planning and decentralization in Quebec have historically been linked to the issue of sovereignty. Since the White Paper on decentralization of 1977, the Regional County Municipalities have been set up in order to define and implement development plan at the local level. But this transfer of responsibility was part of the desire to make Quebec a nation.”[3]

Thus, 95 RCMs were set up in the wake of the Land Use Planning and Development Act and its sovereignist decentralization vision. The RCM of Rivière-du-Loup was established in 1982, and is composed of twelve rural municipalities and one city centre.[4]

According to this more global view of regionalization and rationalization of the development, RCMs’ main mission is to organize a dialogue between local planning actors at a supra-municipal level (Lévesque, 1979; Gouvernement du Québec, 1983a, 1983b). The Land Use Planning and Development Act translates this shift to more localized planning by putting the Schéma d'aménagement et de développement (SAD) of the RCM at the heart of the planning process (Saint-Amour, 2000, p. 343).[5] Therefore, although RCMs were not seen as a political body, they were nonetheless political. Their political legitimacy did not strictly come from popular election, but from their role in territorial consultation. And their role of local expertise building proved to be a key function of planning (Proulx, 2008, p. 40). Therefore, it can be said that the SAD’s instrumental role has always been important, and that its political role is not obvious but implied by its establishment as consultation process and strategy formulation.

The two first SADs were published in 1985, and most of initial SADs were published between 1986 and 1990. In 1988, the climax of the first generation of SAD, 60 RCMs published their first Schéma d’aménagement. The RCM of Rivière-du-Loup prepared its SAD in 1987 and published it in 1988.

Figure 1

Timeline of the planning documents of the RCM of Rivière-du-Loup

The Land Use Planning and Development Act stipulates that a SAD has to be renewed every five years. The first step of the updating process is the formulation of new objectives in a Document sur les objets de la révision (DOR). The second step is the proposal of a Projet de schéma d’aménagement et de développement révisé (PSADR). Last, the third step is the completion of the Schéma d’aménagement et de développement révisé (SADR). Most DORs were created between 1993 to 1996. The RCM of Rivière-du-Loup made its DOR in 1994-1995. Ten years later, Rivière-du-Loup published its PSADR (2005) and completed its SADR in 2013 (which is not yet in force). As Figure 2 shows, between 1996 to and 2013, 60 SADs were published in 1988, 50 DORs in 1994, but fewer than 30 PSADR in 1996, and never more than 10 updates each year from 1997 to 2013. Two reasons could explain the decline of RCMs’ planning publications since the end of the 1990s: first, the unsureness of the provincial government’s strategy on economic development; second, the lack of local expertise capacity, despite “one of the principal missions of the RCM is to keep updated the planning documents.”[6]

Figure 2

Timeline of SADs and renewals in Quebec’s RCMs (1985-2013)

1.2 The Strategic, Collaborative, and Forward-looking turn of the Mid-2000s

Although Quebec’s forward-looking planning was popular during the Quiet Revolution and the 1970s (Lavallée, 2001), by the 1980s less top-down, less forward-looking, and more localized planning was favoured (Mazangol, 2002, p. 5). “The hopes of managing the future which led the first wave of future-oriented studies appeared unrealistic, the results obtained meagre or disappointing. This approach suddenly appeared to be too long and unproductive” (Lavallée, 2001, p. 297). The first generations of RCMs’ planning documents consisted of a simple review of demographic and economic trends and an inventory of equipments and infrastructure to be produced, but few promoted a truly future-oriented vision. In fact, with regards to vision and even the operational aspect of planning, urban plans and sectoral plans held greater influence (Proulx, 2008, p. 40). Furthermore, in the late 1980s, the “socio-economic summit” formula, which favoured local consultation for short-term action, was preferred to scholarly planning and long-term forecasting (Proulx, 2008, p. 41). Although these local and regional forums addressed issues that could be described as forward-looking, they were more aimed at connecting decision-makers than shaping the long-term future. In other words, the idea of future-telling was absent from most first-generation SADs.

But at the beginning of the 2000s, policy-making was renewed around three axes: spatial planning, public debate, and sustainable development (Gauthier, Gariépy, & Trépanier, 2008). The Sustainable Development Act of 2006 greatly contributed to changing the approach at the regional level. Indeed, the notion of sustainability brought new interest to long-term vision (Fourny & Denizot, 2007). Ideas such as long-term visioning and spatial cohesion were clearly highlighted by the Sustainable Development Act:

“Sustainable development is based on a long-term approach which takes into account the inextricable nature of the environmental, social and economic dimensions of development activities”

Sustainable Development Act, 2006

The first issue of the resulting Governmental Strategy for Sustainable Development (2008-2013), subtitled “A Collective Commitment”, is called “Develop Knowledge”:

“Knowledge is the preferred tool for encouraging endorsement of sustainable development values and principles and making enlightened decisions.… The development, acquisition and dissemination of knowledge and scientific, technical, traditional and popular experiments and experience require awareness, training, research and innovation. Thanks to this knowledge, it is possible to act efficiently and responsibly to rouse the public’s interest and stimulate its commitment”

Government of Quebec, 2008–2013, p. 19

To complete this objective of collective knowledge production, the second issue of the strategy puts forward the idea of foresight:

“In foresight, Québec must also adjust to demographic changes by adopting innovative measures designed to foster economic prosperity and demographic balance, notably through catalyst projects creating wealth. It must develop its land and natural resources responsibly, using an integrated management approach”

Ibid.

Here, the term “foresight” does not refer to the practice of foresight as such, but simply to the importance of anticipation – of looking to the future. To achieve this vision in the field of planning, the provincial government published a document, La vision stratégique du développement. Guide de bonnes pratiques sur la planification territoriale et le développement durable, which promoted the collaboration for formulating a “strategic vision” for territorial development :

“The strategic vision is an explicit representation of a desired future, both rational and intuitive, inclusive and forward-looking. Speaking to all the stakeholders of the community, it proposes a convergent and coherent framework for the implementation of a shared ambition.… It is a comprehensive picture of where the community wants to be in a long-term planning horizon, in 15 to 20 years or more”

Government of Quebec, 2010, p. 8

The Sustainable Development Act and accompanying strategy have three main consequences for planning and forecasting. First, they highlight a strategic turn (Côté, Lévesque, & Morneau, 2009). As in Europe, the idea of planning is now more related to the formulation of a spatialized strategy of development, whereas it was previously focused on a simple review of local infrastructures and a land-use approach (Motte, 2006, p. 26). Second, they also represent a collaborative turn (Healey, 1997; Douay, 2008). Planning is now based on a more collective approach and long-term subsidiarity. To achieve these strategic and collaborative turns, the visioning process is put forward as a collective process for constructing a future-oriented strategy. In Quebec, this frame does not refer clearly to the techniques of strategic foresight (Godet, 2007) or of “la prospective territoriale” (Loinger & Spohr, 2005; Cordobès, 2013) themselves, but to a more general idea of anticipation of developmental trends and of the future of the territory. Thus, third, we can nonetheless speak of a forward-looking turn in planning at the end of the 2000s.

In legal terms, before 2011 RCMs were not strictly part of the sustainable development framework. However, the government foresaw to implement progressively this agenda in all areas and institutions of public action. Moreover, the legal framework of planning was directly covered by the law. Therefore, despite this non-obligation of compliance before 2011, RCMs quickly adopted this new regulatory and strategic framework (Marchand, 2015, p. 6). In order to provide a legal framework for this evolution, in 2011 the provincial government adopted the Avant-Projet de Loi sur l’aménagement durable du territoire et l’urbanisme. In this document, the government conferred on RCMs the responsibility to produce “a strategic vision statement” (Gouvernement du Québec, 2011, p. 9) for the cultural, economic, environmental, and social development of their territory. And what could be better to do this than the Schéma d’aménagement et de développement? Indeed, according to a government survey, half the RCMs had adopted a strategic vision of sustainable development by 2012 (Gouvernement du Québec, 2012). Moreover, some recent updates of SADs have been clearly inspired by conceptions of “la prospective territoriale”, or at least by a future-telling approach, as in Rivière-du-Loup. Furthermore, there is a recent regional movement in Quebec of future visioning exercises: Gaspésie 2025 in 2001; Saguenay 2025 in 2005; or, more recently, the strategic plan of Abitibi-Témiscamingue in 2013 and Outaouais 2030 in 2014 (Lafontaine, 2001; Proulx, 2016; Robitaille, Chiasson, & Gauthier, 2016). Although this development is a consequence of the government’s agenda of decentralization and rationalization, the provincial administration has not been very involved.[7] Indeed, whereas the concept of visioning is put forward by the provincial administration, Quebec has demonstrated little interest for the “prospective territoriale” itself (Le Berre, 2017, pp. 497–500). Therefore, despite the fact that it is now a legal obligation, this regional movement of collaborative spatial foresight stems mostly from a regionalist agenda, or at least from a regional governance building process, as in Europe (Albrechts, Healey, & Kunzmann, 2003; Haughton &, Counsell, 2004; Haughton, Allmendinger, Counsell, & Vigar, 2010).

2. Storytelling Political Capacity Between Planning and Governance: The Case of Vision 2031

This general context impacts the RCM of Rivière-du-Loup. For renewing its Schéma d’aménagement et de développement, the RCM started a strategic visioning process in 2009 called Vision 2031. This project was thought to be a cognitive tool for the production of the RCM’s SADR. The goal was also to gather inhabitants and stakeholders throughout the territory to foster the cohesion and community identity. More than just a scholarly planning exercise, the aim of such a project was to join people together, to escape the “silo logic” of top-down policy-making, and to fill the gap between decision-makers and citizens. It was also a way for the RCM to sit at the heart of the future-shaping process. Thus, it was a way for this intermediate and not very powerful institution to claim a new role in the context of multi-scalar governance (Marks, 1993, pp. 391–410), one of mediating between all the regional stakeholders. In other words, this type of approach clearly has a political dynamic. Being at the heart of the future-shaping process means being central in the policy-process.

2.1 Storytelling A New Type of Planning

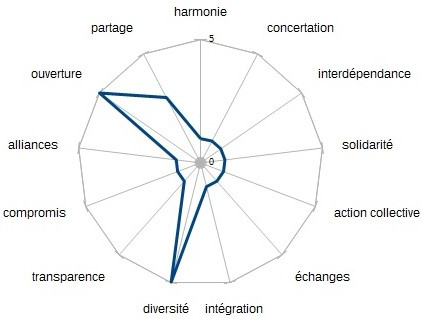

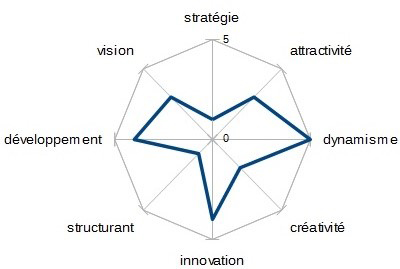

In February 2012, the official strategic vision 2011-2031 was adopted by the council of the Rivière-du-Loup RCM (MRC de Rivière du Loup, 2012). A discursive analysis of the SADR vision statement highlighted two main narratives: a rhetoric of governance and partnership, and a rhetoric of strategy and innovation.

Figure 3

Rhetoric of governance and partnership. Strategic Vision of the Rivière-du-Loup RCM 2011-2031

Figure 4

Rhetoric of strategy and innovation. Strategic Vision of the Rivière-du-Loup RCM 2011-2031

These narratives reflected both the dynamics of the visioning process and its storytelling character. The first step of the project, in 2009, was the creation of a diverse committee, bringing together representatives of the Centre Local de Développement (CLD), the Société d’Aide au Développement de la Communauté (SADC), and the Centre de Santé et de Services Sociaux (CSSS) of Rivière-du-Loup, the Corporation de Développement Communautaire (CDC) of the region of Kamouraska, Rivière-du-Loup, Témiscouata et des Basques (KRTB), and the municipality and the Regional County Municipality of Rivière-du-Loup. This kind of supra-municipal committee was not an innovation, but the rhetoric employed, insisting on a dynamic partnership, was new and stemmed from both the strategic state paradigm (Côté, Lévesque, & Morneau, 2009) and the collaborative democracy paradigm (Gauthier, Gariépy, & Trépanier, 2008) that emerged during the turning point of the 2000s in Quebec. The second step was a “Tournée des Municipalités” of the RCM, consisting in the organization of eight round-tables that gathered local stakeholders on cross-cutting and spatial issues for local development. About one hundred people met during these round-tables. In 2010, the RCM also set up a web survey on “the values” shared by the population of the territory, and made a synthesis of these statements.[8] If roundtables fit into the tradition of public consultation, their use combined with a survey on values and perceptions of the future highlights a new interest for foresight techniques (Popper, 2008). It also expresses a growing interest for bringing to the visioning process new actors and new discourses, in line with growing interest for social innovation (Dandurand, 2005) and deliberative practices in planning (Forester, 1999). In 2011, the third step was the organization of a consultative committee composed of volunteer citizens and charged with the coordination of five public consultations throughout the territory of the RCM. Nearly 350 people participated in these consultations and 27 organizations were involved.[9] This type of public consultation is not an innovation in itself. It belongs to the historical role of RCMs. But what is new is the involvement of citizens to animate consultations. In such a process, citizens become partners of public institutions, alongside traditional organizations of the decision-making process (Loncle & Rouyer, 2004), as advocated by the OECD (OECD/OCDE, 2002).

In 2012 a new step of the consultation and communication process was initiated via the presentation of the vision by several organizations within the RCM’s perimeter. Involving around 500 people, the visioning process of Rivière-du-Loup was clearly claimed as a strategy of regional mobilization and commitment, as the prefect of the RCM proclaimed during the inauguration of Le Visionnaire:

“Beyond the fact that the law requires us to carry out a strategic vision, we have decided to go further with an opened approach, focused on exchange and the contribution of all, especially with the sculpture Le Visionnaire.”[10]

Here appears the main innovation of Vision 2031 – the conclusion of the process by the creation of Le Visionnaire, a sculpture resulting of a specific consultation of youth, in partnership with the Commission scolaire, and inhabitants through a Facebook page. So, the novelty of this exercise was threefold: the mobilization of a new public (youth), investment of the symbolic (art), and use of a new way of consultation (a social-network). First, youth were one key public of the consultation and communication process:

“That was the best part that we managed to do. We have managed to mobilize many young people. By the way, we are still working with the schools: we are setting up pedagogical kits to guide teachers in each school. We are putting this in place.... so that each teacher can work with his students on their own vision of the future.”[11]

Second, a wide strategy of communication was set up through social-networking, but also through teaching and merchandising. The RCM financed the manufacture and marketing of tote bags, on which the logo of the project was drawn; video capsules on the web; social media monitoring; and promotion of the sculpture project. So, what was new in this planning practice was the combination of new communication techniques (social media and merchandising) and a new mobilization technique (making a collaborative sculpture). Third, then, the sculpture had clearly a pedagogical dimension, but also a mobilizing function.[12] Noting that it is difficult for people to appropriate a planning document, the idea of using art as mediation was intentionally pursued.

“In art we find this imaginary, this forward-looking dimension. At the same time, it made it possible to federate all the partners around this object. Through this object you could find all the hopes of partners, including children who were able to see their participation being materialized.”[13]

Indeed, the artist engraved on the sculpture visions of youth (resulting from brainstorming in schools) and of social networkers (quoting a selection of individual statements on the Facebook page of the project).

“My interpretation of the demand was to realize a work that can both testify to the strategic vision of the RCM, but also bear witness to the personal visions of the inhabitants. Le Visionnaire is both a sensor and a reflection of the visions of people.”[14]

Moreover, it was decided to erect the sculpture just outside the administrative building of the RCM, emphasizing the territorial legitimacy of the Regional County Municipality. This object, then, appears as a totem, a symbolic and federative place for the community (Durkheim, 2008, p. 143). This highlights how Vision 2031, beyond its strategic instrumental function, contains a communicative and legitimating function for the regional community, but also for the RCM itself in terms of politics and polity.

2.2 Storytelling A New Mode of Government

The narrative on an inclusive and forward-looking spatial planning appears also as storytelling a new mode of government. Three main ideas emerge from this case study, combining discursive and instrumental dimensions: that kind of spatial forward-looking planning is a collaborative and communicational instrument for regional animation in a context of an increasing governance building, it is also a cognitive instrument useful to share socio-political values and practices throughout a territorial community, and it is a political instrument for intermediate public institutions to heighten their legitimacy in a global context of centre-periphery tension and territorialization of policy practices (Albrechts, Healey, & Kunzmann, 2003). To begin with the collaborative and communicational governance, that kind of project achieves the implication of all the planning stakeholders, since the beginning of the visioning process. Thus, the Commission scolaire de Kamouraska-Rivière-du-Loup, the SADC, and the CLD contributed to the funding of the consultation process, as well as participated in the steering committee. The regional Conseil de la culture also participated in the name of the “public art dimension” of the sculpture. The CEGEP of Rivière-du-Loup was also involved by loaning equipment and buildings. Then, the Museum of the Bas-Saint-Laurent was and is part of the process by including the sculpture in its “Circuit Public Art”. Finally, the RCM led the process and financed it, first through its regular resource budget, but also through its budget allowance for rural development. From the first step of the decision-making process (the joined-up committee), to the funding process (a cross-cutting funding), and the strategy formulation process (the collaborative consultations), Vision 2031 was based on a discursive dynamic that blurred the gap between decision-maker and citizen, between citizen and inhabitant, between expert knowledge and children’s imagination, and between sectors and territories, with the aim of involving as large a coalition of actors as possible.

“The wealth of the RCM of Rivière-du-Loup comes from each of its communities and their solidarity…. The communities of the RCM are aware of their interdependencies. They are cooperative, open-minded, in solidarity, and share their wealth. The municipal organization of the RCM reflects the desire of sharing…. between communities. They pursue the same vision, to remain a pleasant, liveable, fair and prosperous territory for the generations of today and tomorrow”

MRC de Rivière du Loup, 2012, p.4

This all-out actors commitment helped to embody “the community”. It brought to it an institutional and a social consistency. This type of commitment has two consequent main political properties. First, it is a process of territory making, both in terms of community, polity, and perimeter for politics and policies. And territory making is precisely one of the pillars for political legitimacy (Le Bart, 2003, p. 147). Second, it is also a process of polity defining. That is to say, it contributes to defining people of the community, which means to give body to “the subjects” of the polity. Yet again, polity defining is a second pillar for political legitimacy (Hassenteufel & Rasmussen, 2000, p. 59). Since the late 1990s and the beginning of the 2000s, there has been an increasing consideration on the need for a more porous and open system, bringing into the policy process a much wider range of actors, in a context of a weakening conception of a closed-off territorial system (Rhodes, 1997). This political trend means the opening of sub-national governance systems, implying various styles of cross-cutting partnership (Haughton & Counsell, 2004, p. 33) – from children to decision-makers, each member of the community is now considered and involved as a potential partner. The discourse put forward collaborative approaches, and the idea of participative democracy emphasized both the issue of expanding stakeholder involvement beyond traditional elites and recognizing alternative forms of knowledge. This new type of spatial planning, based on storytelling in an open and collaborative policy-making process, operated as a territorial networking activity and regional identity building (Haughton et al, 2010). The sustainability concept was again one of the cognitive streams of this process: “sustainable development debates have focused both on the need for “new localism” discourses premised on the notion that it is local actors who are best positioned to address many of the concerns of sustainable development” (Haughton, Counsell, 2004, p.34).

In the cognitive dimension of this new forward-looking spatial planning, innovation was not in the content of the planning documents, nor was it in the identified issues themselves,[15] but in the communication around the planning process. It aimed at creating a cognitive frame shared by as many stakeholders as possible. The first goal was to put forward the necessity of harmonizing the regional planning documents. Thus, the strategic vision was used by the RCM administration to frame the new SADR, thanks to the identification of five cross-cutting issues voted on during public consultations: “quality of life, family, dynamism, innovation, spirit of openness” (MRC de Rivière -du Loup, 2012, p. 1). The first aspect of the cognitive dimension was actually an aim of rationalization of the several previous planning documents. The second aspect aimed at consensus building between the different stakeholders in order to harmonize (i.e. rationalize) their different development strategies and representations of the territory. To do so, foresight appeared as an accurate tool to reach consensus because of its long-term horizon:

“If you want to reach consensus, it is difficult to go down a 20 years horizon. Below 20 years, there is a too great diversity of opinions. It is more complex to build consensus on a 5 or 10 years horizon only. Whereas if you look far into the future, it is easier to reach a consensus.”[16]

The third aspect is was to foster the diffusion of the strategy in order to help the standardization of the different stakeholders’ strategies of development. For example, the RCM of Rivière-du-Loup created a “Charte d’engagement” so that stakeholders would act in accordance with the general strategy and objectives of the RCM. Indeed, institutions that ratified the charter committed to act in conformity with the policy-framework and strategic vision of the RCM. But because of its non-obligatory compliance dimension, this guideline was mostly communicational.

“It is more a communication posture than anything else, because once it is signed, you can hang it on a wall and that’s it …. You know, everybody is very interested at the beginning of the process in working with each other, but when it is over the old routine gets the upper hand.”[17]

And yet, for lack of being better operationalized, it helped at diffusing and sharing the cognitive frame. Here appears the political dimension of forward-looking spatial planning. Through these communicational and cognitive devices, it appears that, more than planning in and of itself, the visioning step was used to steer a fragile regional governance by shaping and sharing a vision of the future. Therefore, it can be said that foresight has a legitimizing function. It should be remembered at this point that the strategic visioning process is in principle just a legal first step for the renewing of the Schéma d’aménagement et de développement. The RCM achieved a communication feat in managing to commit a large number of stakeholders to participating in and agreeing on the RCM’s planning strategy. This strategy translated a search for a more relational way of planning. It also translated a move to a more collaborative way of making policies. Even if it remains fragile, this trend puts the light on an on-going “shared governance.” And foresight helps to achieve the institutionalization of such a model of governance that, in return, transforms the meanings and uses of knowledge. As a result, beyond the classic vision of expertise as a tool for decision-making, forward-looking spatial planning “emerges as a political apparatus of governance that can promote collective mobilization and the exchange of resources. It helps to structure collective action on a territory. In this sense, the development of such a mediating expertise could well be considered, at least in the eyes of public officials, as a response to the context of polycentrism and divided interests” (Cadiou, 2007, p. 173). Here appears a final pillar for building the legitimacy of intermediate political spaces the capacity to shape shared narratives of the future. In other words, more than expressing a concrete capacity for action, the collaborative production of future-oriented narratives of the future is part of a storytelling of political capacity.

Conclusion

Creating knowledge justified only by technocratic principles is no longer adequate. What matters is sharing and opening the policy process to produce a collective vision of the region. By integrating spatial foresight to a planning exercise, the Regional County Municipality of Rivière-du-Loup made this shift to a more relational and communicative planning, which means that knowledge sharing and networking are henceforth what imply the most (Cadiou, 2007, p. 175). The mobilization of knowledge and skills from the civil society takes place in order to increase the viewing angles of the future (Cuhls, 2003). Thus, wider civil society becomes partner of the knowledge production. By operating as a networking activity, this “new spatial planning” (Haughton, Allmendinger, Counsell, & Vigar, 2010) contributes to the institutionalization of new spaces of politics, involving the multiplicity of local and individual interests, identities, and visions. But this process is mainly discursive. If words of planning have changed, the operation of planning has not. In other words, such forward-looking spatial exercises appear as a renewed narrative and order of meaning on governance and planning, far from a new type of governance or planning as such.

But the shift from a hierarchical and sectoral approach of planning to a more spatialized, horizontal, and future-oriented approach is part of a more global perspective, as studied by Haughton et al (2010). First, this “new spatial planning” translates to an on-going shift from silo logic to spatial logic, which means that sectoral issues are now more spatialized. Being spatial makes them horizontal, and implies that the responsibility of the economic development stems not only from the public government, but also from all the regional community. Second, these new policy narratives bring to light that nowadays the authority and political capacity of public governments are challenged. It underlines more generally the crisis of the top-down model of state territorial management. In other words, forward-looking thinking and guidelines seem to be new types of regulation – a governance by the future. Here appears the link between spatial planning, a politics of the future, and governance. Governance is based on a more horizontal management of public policies. Governance is the result of a need to develop new narratives, but also forms of policy regulation and coordination, which break with traditional hierarchical forms and narratives of state control. It also means that this new type of politics is rooted in the weakening of older forms and narratives of regulation. Moreover, its development stems from a specific context of the weakening centrality of public authorities. Regarding this global context, collaborative strategic visioning processes appear as tools that help public authorities remain central in sub-regional politics.

Parties annexes

Biographical note

Sylvain Le Berre, Sciences Po Rennes, Université de Rennes 1, Arènes (CNRS UMR 6051).

Notes

-

[1]

“Municipalité Régionale de Comté” (MRC) in French.

-

[2]

It is what Jean-Claude Passeron and Jacques Revel call “la pensée par cas” (Passeron, & Revel, 2005; Hamidi, 2012).

-

[3]

Interview with a special advisor at the Ministère du Conseil Exécutif, Quebec Government, October 2013.

-

[4]

Today, thirteen municipalities belong to the RCM of Rivière-du-Loup, which is in the perimeter of the administrative region of the Bas-Saint-Laurent. Rivière-du-Loup is 210 kms from Quebec City and 430 kms from Montreal. This region is considered peripheral, which means that it is at the periphery of inhabited Quebec. Its economy is mostly based on the third sector (70% of the active population of the RCM). Rivière-du-Loup is a tourist cross-road between Quebec City, the Saguenay, and the Gaspésie, making tourism an important aspect of its economy. The secondary sector is the second pillar of the RCM’s economy (18% of the active population) but the primary sector is quite strategic (9% of the active population) compared to the rest of Quebec, meaning that it is a “resource region”.

-

[5]

RCMs were initially conceived as the “local” scale of a higher regional level, which would have been called Conseil régional de concertation et d’intervention (CRCI). CRCIs had never been created as such, but almost ten years later the relatively similar Conseil régionaux de concertation et de développement (CRCD) was established in 1992.

-

[6]

Interview with agent of the RCM of Rivière-du-Loup, November 2013. The evolution of the documentary production and the political capacity of RCMs seems to evolve according to strategic changes of the provincial government of the day (particularly in terms of decentralization and regionalization), of political agenda (sovereignism, territorial reform, rationalization of public policies), and of territorial dynamics (territorial competition, evolution of institutional configurations).

-

[7]

The provincial administration only controls conformity of RCMs’ planning strategy and documents to the government’s general strategy.

-

[8]

According to the RCM, almost 250 people voted.

-

[9]

Speech of the agent in charge with the Rural Pact’s development and responsible for the strategic approach, during the inauguration of the sculpture Le Visionnaire, 12 September 2013. http://riviereduloup.ca/vision/?id=vision&a=2012

-

[10]

Speech of the Prefect of the RCM of Rivière-du-Loup, during the inauguration of the sculpture, Le Visionnaire, 12 September 2013. http://riviereduloup.ca/vision/?id=vision&a=2012

-

[11]

Interview with agent of the RCM of Rivière-du-Loup, November 2013.

-

[12]

The project Le Visionnaire won the regional “Prize of rurality” and was selected for its national final in the category “Mobilization”, organized by the provincial government to reward the best projects that fostered rural development. Mentioned by the press release of the 16 September 2014, published by the RCM Rivière-du-Loup. http://www.riviereduloup.ca/communiques/?a=2014

-

[13]

Interview with agent of the RCM of Rivière-du-Loup, November 2013.

-

[14]

Interview with the sculptor of Le Visionnaire, MaTV, Lezards Tv Show, 22 October 2013. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=67mvwvBrV8E

-

[15]

Indeed, the issues and cartography of the SADR are quite classical in terms of territorial diagnosis: demographic and economic attractiveness, urban extension, changes in agriculture and industry, environmental issues, transport infrastructures, public services, etc. (MRC de Rivière-du-Loup, 2013a). Indeed, apart from a demographic projection to 2031 (MRC de Rivière-du-Loup, 2013a, chapter 2, p. 20), few of the statistical data used in the SADR are truly engaged in forecasting; most are retrospective.

-

[16]

Interview with agent of the RCM of Rivière-du-Loup, November 2013.

-

[17]

Ibid.

Bibliography

- Albrechts, L., Healey, P., & Kunzmann, K.R., (2003). Strategic spatial planning and regional governance in Europe. Journal of American Planning Association, 69(2), 113–129.

- Andersson, J. (2012). The great future debate and the struggle for the world. American Historical Review, 117(5), 1411-1430.

- Böhme, K. (2002). Nordic Echoes of European Spatial Planning : Discursive Integration in Practice., Stockholm: Nordregio.

- Cadiou, S. (2007). Jeux et enjeux de connaissances. L'expertise au service de la gouvernance municipale. In R. Pasquier, V. Simoulin, & J., Weisbein, (Eds.), La gouvernance territoriale. Pratiques, discours et théories (pp. 171–189). Paris: LGDJ.

- Cordobès, S. (2013). Prospective territoriale. In J. Lévy & MJ. Lussault, (Eds.), Dictionnaire de la géographie et de l’espace des sociétés (pp. 819–821). Paris : Belin.

- Côté, L., Lévesque, B., & Morneau, G. (Eds.) (2009). État Stratège et Participation Citoyenne. Québec: Presses de l’Université de Québec.

- Cuhls, K. (2003). From forecasting to foresight processes. New participative foresight activities in Germany. Journal of Forecasting, 22(2-3), 93–111.

- Dandurand, L. (2005). Réflexion autour du concept d’innovation sociale, approche historique et comparative. Revue française d’administration publique, 115(3), 377–382.

- Douay, N. (2008). La planification métropolitaine montréalaise à l’épreuve du tournant collaboratif. In M. Gauthier, M. Gariépy, & M-O., Trépanier (Eds.). Renouveler l’aménagement et l’urbanisme. Planification territoriale, débat public et développement durable (pp. 109–136). Montréal: Presses de l’Université de Montréal.

- Durance, P., Godet, M., Mirénowicz, P., & Pacini, V. (2007). La prospective territoriale. Pour quoi faire ? Comment faire ?, Les Cahiers du LIPSOR, série Recherche no.7.

- Durkheim, E. (2008). Les formes élémentaires de la vie religieuse. [1912], Paris: PUF, Quadrige.

- Faure, A. (2011). Les politiques locales, entre référentiels et rhétoriques. In A. Faure, G. Pollet, P. Warin (Eds.). La construction du sens dans les politiques publiques. Débat autour de la notion de référentiel (pp. 69-83). Paris: L'harmattan.

- Fischer, F. (2012). Reframing Public Policy. Discursive Politics and Deliberative Practices, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Forester, J. (1999). The Deliberative Practitioner. Encouraging Participatory Planning Process. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

- Fourny, M-C. & Denizot, D. (2007). La prospective territoriale, révélateur et outil d’une action publique territorialisée. In R. Dodier, A. Rouyer, & R. Séchet (Eds.). Territoires en action et dans l’action (pp. 29–44). Rennes: Presses Universitaires de Rennes.

- Gauthier, M., Gariepy, M. & Trepanier, M-O. (Eds.). (2008). Renouveler l'aménagement et l'urbanisme. Planification territoriale, débat public et développement durable., Montréal:, Presses de l'Université de Montréal.

- Gazibo, M., &, Jenson, J. (2015). La politique comparée. Fondements, enjeux et approches théoriques (2nd ed.). Montréal: Presses de l’Université de Montréal.

- Godet, M. (2007). Manuel de prospective stratégique (3rd ed). Paris: Dunod.

- Gouvernement du Québec. (1983a). Aménager l'avenir. Québec: Conseil Exécutif.

- Gouvernement du Québec. (1983b). Le choix des régions. Québec: Cabinet du Ministre délégué à l’aménagement et au développement régional.

- Gouvernement du Québec. (2010). La vision stratégique du développement. Guide de bonnes pratiques sur la planification territoriale et le développement durable, (E. Guillemette, Ed.). Québec: Direction générale des politiques du Ministère des Affaires municipales, de l’Occupation et de l’Aménagement du Territoire.

- Gouvernement du Québec. (2011). Avant-Projet de Loi sur l’aménagement durable du territoire et l’urbanisme. Québec: Éditeur officiel.

- Gouvernement du Québec. (2012). Sondage sur les démarches de développement durable des organismes municipaux et régionaux, analyse des résultats. Québec: MAMROT.

- Gouvernement du Québec. (2017). Portrait global de la planification régionale et métropolitaine. Quebec: Ministère des Affaires Municipales et de l’Occupation du territoire. Retrieved from: https://www.mamot.gouv.qc.ca/amenagement-du-territoire/portrait-global-de-la-planification-regionale-et-metropolitaine/

- Government of Quebec. (2008–2013). Governmental Strategy for Sustainable Development (2008-2013) – A collective commitment. Quebec : Official Editor.

- Guiader, V. (2008). Socio-histoire de la prospective. La transformation d'une entreprise réformatrice en expertise d’État., Doctoral dissertation, Université Paris-Dauphine.

- Hall, P., &, Taylor, R. (1997). La science politique et les trois néo-institutionnalismes. Revue française de science politique, 47ᵉ année,(3-4), 469-496.

- Hamidi, C. (2012). De quoi un cas est-il le cas ? Penser les cas limites. Politix, 4 (100), 85–98.

- Hassenteufel, P., &, Rasmussen, J. (2000). Le(s) territoire(s) entre le politique et les politiques – Les apports de la science politique. In D. Pagès & N. Pélissier (Eds.), Territoires sous influence, Tome Vol. 1 (pp. 59–82). Paris: L'Harmattan.

- Haughton, G., Allmendinger, P., Counsell, D., & Vigar, G. (2010). The New Spatial Planning. Territorial management with soft spaces and fuzzy boundaries, London & New-York: Routledge.

- Haughton, G., &, Counsell, D. (2004). Regions, Spatial Strategies and Sustainable Development., London & New-York: Routledge.

- Healey, P. (1993). Planning through debate: The communicative turn in planning theory. In F. Fischer & J. Forester (Eds.), The argumentative turn in policy analysis and planning (pp. 233–253). Durham & London: Duke University Press.

- Healey, P. (1997). Collaborative planning. Shaping places in fragmented societies., Vancouver: UBC Press.

- Lafontaine, D. (Ed.). (2001). Choix publics et prospective territoriale. Horizon 2025. La Gaspésie : Futurs anticipés. Rimouski: UQAR-GRIDEQ.

- Lardon, S., & Noucher, M. (Eds.) (2016). Prospective territoriale participative [Special issue]. Cahiers de géographie du Québec, 60(170).

- Lavallée, A. (2001). La démarche prospective en France et au Québec : Qquelques points de repères. In D. Lafontaine, (Ed.), Choix publics et prospective territoriale. Horizon 2025. La Gaspésie : Futurs anticipés (pp. 295–300). Rimouski: UQAR-GRIDEQ.

- Le Bart, C. (2003). Le leadership territorial au-delà du pouvoir décisionnel. In A. Smith & C. Sorbets (Eds.), Le leadership politique et le territoire (pp. 147–161). Rennes: Presses Universitaires de Rennes.

- Le Berre, S. (2017). L’investissement politique du futur : un mode de légitimation et de gouvernement. Une comparaison Bretagne, Pays-de-Galles, Québec. Doctoral dissertation, Université de Rennes 1.

- Lévesque, R. (1979). Premier Ministre du Québec, Discours du 26 septembre 1979 pour le banquet de clôture de l’Union des Municipalités du Québec. Online archive of La Société du patrimoine politique du Québec. Retrieved from http://www.archivespolitiquesduquebec.com/discours/p-m-du-quebec/rene-levesque/discours-prononce-par-monsieur-rene-levesque-premier-ministre-du-quebec-au-banquet-de-cloture-de-lunion-des-municipalites-du-quebec-le-mercredi-26-septembre-1979-au-centre-municipal-des-congres/

- Lévesque, R., (1981). Premier Ministre du Québec, Discours du trône du 9 novembre 1981, Québec, Assemblée Nationale du Québec. Online archive of La Société du Patrimoine politique du Québec. Retrieved from http://www.archivespolitiquesduquebec.com/discours/p-m-du-quebec/rene-levesque/discours-du-trone-quebec-9-novembre-1981/

- Loinger, G., & Spohr, C. (2005). Prospective et planification territoriale. DATAR, col. Travaux et Recherches de Prospective, no.24.

- Loncle, P., & Rouyer, A. (2004). La participation des usagers: Un enjeu de l’action publique locale. Revue Française des Affaires Sociales, 4, 133–154.

- Marchand, A. (2015). Politique de développement durable: le cas de la MRC d’Argenteuil et des municipalités locales., Master’s thesis, Université de Sherbrooke.

- Marks, G. (1993). Structural policy and multi-level governance in the EC. In A. Cafruny & G. Rosenthal (Eds.), The state of the European Community. Vol. 2: The Maastricht debates and beyond (pp. 391–410). Boulder: Rienner.

- Mazangol, C. (2002). L'aménagement du territoire entre l'ambition et le renoncement. Revue Interventions Économiques, 28, Retrieved from: http://interventionseconomiques.revues.org/1078

- Motte, A. (2006). La notion de planification stratégique spatialisée (Strategic Spatial Planning) en Europe (1995–-2005). Lyon: col. Recherches, PUCA.

- MRC de Rivière du Loup. (2012). Énoncé de vision stratégique de la MRC de Rivière-du-Loup, 2011–2031. Rivière du Loup.

- MRC de Rivière du Loup., (2013a). Schéma d’aménagement et de développement révisé. Rivière du Loup.

- MRC de Rivière du Loup., (2013b, April 15). Une sculpture pour incarner la Vision stratégique adoptée par la MRC de Rivière-du-Loup prendra place sur les terrains de la préfecture. Retrieved from http://www.riviereduloup.ca/communiques/?a=2013

- MRC de Rivière du Loup., (2013c, September 12). MRC de Rivière-du-Loup, Inauguration inauguration de la sculpture Le Visionnaire. Retrieved from http://www.riviereduloup.ca/communiques/?a=2013

- MRC de Rivière du Loup, (2014). La MRC de Rivière-du-Loup finaliste nationale aux Grands Prix de la ruralité 2014! Retrieved from http://www.riviereduloup.ca/communiques/?a=2013

- OECD/OCDE. (2002). Des citoyens partenaires; Information, consultation et participation à la formulation des politiques publiques. Paris: L’Harmattan.

- Pasquier, R. (2012). Le pouvoir régional. Mobilisations, décentralisation et gouvernance en France. Paris: Presses de Sciences Po.

- Passeron, J-C., & Revel, J. (Eds.). (2005). Penser par cas. Paris: EHESS.

- Petit Jean, M. (2016). L’institutionnalisation de la prospective dans l’action publique: Analyse comparée des systèmes politico-administratifs britanniques, néerlandais et wallon. Doctoral dissertation, Université Catholique de Louvain.

- Popper, R. (2008). Foresight Methodology. In L. Georghiou, J. Cassingena Harper, M. Keenan, I. Miles, & R. Popper (Eds.), The Handbook of Technology Foresight. Concepts and Practice. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Proulx, M-U. (1996). Les trois échelons territoriaux du Québec: Les enjeux de la decentralisation. In S. Côté, J-L. Klein, & M-U. Proulx (Eds.), Le Québec des régions: Vers quel développement. Chicoutimi-Rimouski: GRIDEQ-GRIR.

- Proulx, M-U. (2008). 40 ans de planification territoriale au Québec. In M. Gauthier, M. Gariepy, & M-O. Trepanier (Eds.), Renouveler l'aménagement et l'urbanisme. Planification territoriale, débat public et développement durable (pp. 23–54)., Montréal: Presses de l'Université de Montréal.

- Proulx, M-U. (2016). Visionnement 2025 au Saguenay-Lac-Saint-Jean. In S. Lardon & M. Noucher (Eds.). Prospective territoriale participative [Special Issue], Cahiers de géographie du Québec, 60(170), 343-360.

- Rhodes, R. (1997). Understanding governance: Policy networks, governance, reflexivity and accountability. Buckingham & Philadelphia: Open University Press.

- Rio, N. (2015). Gouverner les institutions par le futur : usages de la prospective et construction des régions et des métropoles en France (1955–-2015). Doctoral dissertation, Université Lumière – Lyon 2.

- Robitaille, M., Chiasson, G., Gauthier, M. (2016). De la planification stratégique régionale à la prospective en Outaouais : la difficile construction d’un nouveau rapport au temps. In S. Lardon & M. Noucher (Eds.). Prospective territoriale participative [Special Issue], Cahiers de géographie du Québec, 60(170), 325-342.

- Saint-Amour, J-P. (2000). Les interventions gouvernementales et la Loi sur l’aménagement et l’urbanisme. Revue de droit Droit de l’Université de Sherbrooke, 31, 341–405.

- Sokoloff, B. (1984). Le choix des régions : un nouvel enjeu pour le pouvoir local au Québec ?, Revue Canadienne des Sciences Régionales, VII7(2), 251–264.

- Sustainable Development Act, Quebec. (2006, Chapter D-8.1.1). Retrieved from http://legisquebec.gouv.qc.ca/en/ShowDoc/cs/D-8.1.1

Liste des figures

Figure 1

Timeline of the planning documents of the RCM of Rivière-du-Loup

Figure 2

Timeline of SADs and renewals in Quebec’s RCMs (1985-2013)

Figure 3

Rhetoric of governance and partnership. Strategic Vision of the Rivière-du-Loup RCM 2011-2031

Figure 4

Rhetoric of strategy and innovation. Strategic Vision of the Rivière-du-Loup RCM 2011-2031