Résumés

Abstract

In the 1970s, two private adoption agencies faced state and public scrutiny over their ‘rescue’ of orphans from Bangladesh, Vietnam and Cambodia. The organizations were run by four Canadian mothers who themselves adopted over fifty children and placed hundreds more with other Canadian families. Inspired by a sense of maternal internationalism, these ‘maverick mothers’ were convinced that removing the children from their war torn nations and bringing them to Canada was in each child’s best interest. According to professional social workers and diplomats, a strong commitment to maternalism and internationalism were not valid enough to trust the complicated operation of international adoption to amateur humanitarians. The mothers’ lack of professional accreditation, their bleeding heart mentality, and examples of radical behavior at home and abroad were seen to threaten international adoption as a legitimate form of child saving. Yet concurrently, the authority and respect granted by the women’s identity as mothers marinated their cause with a certain creditability or at least admiration for their efforts, which gave them a sense of empowerment to challenge and for most of them, to ultimately cooperate with their critics.

Résumé

Au cours des années 1970, deux agences d’adoption privées ont attiré l’attention du public lorsqu’elles ont commencé à « secourir » des orphelins du Bangladesh, du Vietnam et du Cambodge. Ces organisations étaient dirigées par quatre mères canadiennes, qui avaient adopté plus de cinquante enfants entre elles, et en avaient placé des centaines d’autres dans des familles canadiennes. Mues par une sorte d’internationalisme maternel, ces femmes non conformistes étaient persuadées qu’il y allait de l’intérêt de chacun de ces enfants de les retirer d’un pays d’origine déchiré par la guerre pour les amener au Canada. Des travailleurs sociaux professionnels et des diplomates contemporains les critiquèrent, qui croyaient que leur seul engagement maternel et internationaliste, malgré son intensité, ne préparait pas ces humanitaires en herbe à assumer la responsabilité du mécanisme complexe de l’adoption internationale. À leurs yeux, le manque d’accréditation professionnelle de ces mères, leur sentimentalisme, et certaines instances de comportements radicaux de leur part, au pays et à l’étranger, menaçaient la légitimité même de l’adoption internationale comme forme de secours. Pourtant, en parallèle, l’autorité et le respect attribués à ces femmes en tant que mères donnaient crédibilité à leurs efforts, et provoquaient une certaine admiration à leur égard. Ces encouragements les habilitèrent à revendiquer la capacité d’intervenir dans le processus d’adoption. En conséquence, la plupart d’entre d’elles finirent par coopérer avec leurs détracteurs.

Corps de l’article

As a teenager in the 1950s, Sandra Simpson watched a newsreel about postwar South Korea. She was so moved by the plight of the Korean orphans featured in the film that she left the theatre in tears. “It was already in my mind but I guess it was then that I decided that some day I would do my bit,” she recalled, “Some day.”[1] Approximately ten years later, when she was married and already a mother of four living in a Montréal suburb, images of refugee children returned to haunt her. This time they were from Vietnam, and when they appeared nightly on her television, Simpson decided to help by offering to adopt an orphan.[2] Eventually, she managed to untangle the bureaucratic red tape in Ottawa, Montréal, and Saigon and adopted a little girl, Mai Lien, in 1970. Simpson linked her teenage experience watching images of Korea with the ones she saw in Vietnam: “I went after her [Mai Lien] like you can’t believe. There was no stopping me. It was like as if all those years that child that had cried in that newsreel was in someway going to be residing in my home.”[3] Simpson’s interest in reaching out did not stop with Mai Lien. Over the next three decades, she personally adopted 28 children and helped hundreds of other Canadian families adopt from Asia in the 1970s. Simpson was part of a small group of mothers who took leadership of Canada’s first major wave of international adoptions because they believed a Canadian family was the best gift they could give to children whose lives and futures had been disrupted by war, poverty, and civil unrest. Until lasting peace treaties were signed, infrastructures stabilized, and hatred healed, Simpson and her cohorts argued that adoptive families would be found outside of the children’s nation of birth, in the bosom of Western affluence and peace.

The transfer of children across borders for the purpose of adoption has always been a controversial issue for child welfare advocates, government officials, the families on both sides of the adoption equation, and the adoptees themselves. In their histories of adoption in North America, Veronica Strong-Boag, Barbara Melosh, and E. Wayne Carp have problematized the shifting social and political meanings embedded within interracial and international adoptions, questioning whether this post-World War II phenomenon was an embracement of global citizenship, child rights, and cross-cultural understanding, or an example of the most intimate form of imperialism.[4] Rickie Sollinger’s radical feminist analysis of international adoption leaves no room for pondering the ethics. She considers all kinds of adoption, but especially its transnational form, as the ultimate commoditization of children. Sollinger characterizes the exchange of babies, always from poor to rich countries, as a process that serves and protects the needs and wants of the ‘buyer,’ in this case the adoptive parent, not the child or the birth mother.[5] Laura Briggs historicizes the visual trope that spawns Sollinger’s criticism. She claims Westerners’ use of international adoption as a solution to help the foreign ‘waifs’ they saw in photos and on television is dangerous because it takes attention away from the “structural explanations for poverty, famine and other disasters, including international, political, military, and economic causes,” and reinforces the idea of the United States needing to rescue developing nations.[6] More recently, Karen Dubinsky has suggested that scholars need to move beyond the moralizing dichotomy found in the rescue and kidnap ideology outlined by Sollinger and Briggs. She proposes a finer lens to view transnational adoptions because these histories are about real children, and real families, with culturally and historically specific responses to their adoptions — everything cannot be reduced to iconic symbols of power. She asks scholars to acknowledge, for example, that “the intense emotional attachments between adults and children in our world are too complicated to fit into simple binaries.”[7] Dubinsky’s contextualization of international adoption as undoubtedly emotional and complicated for all involved, especially the adults and children breaking up and forming new families, is particularly helpful in understanding the motivations and critique of the women discussed in this article, those who I have nicknamed ‘maverick mothers’. It was their emotional response to the plight of children caught in Cold War crossfires that resulted in the mass airlifts of approximately 700 displaced children from Vietnam, Cambodia, and Bangladesh to Canada in the 1970s, and it was this same emotional response that pitted the maverick mothers’ moral and maternal righteousness over the ideals of professionalism and caution championed by state representatives working in the provincial departments responsible for child welfare and the Department of External Affairs.

Initially, the controversy surrounding Canada’s first foray into international adoption had little to do with the broader concerns about the appropriateness of this movement of children as identified by Sollinger and Briggs; rather the Canadian debate centred around how these adoptions were processed and by whom. Families for Children (FFC) and the Kuan Yin Foundation (KYF) were the private organizations founded by Simpson and three other suburban housewives, all adoptive mothers themselves who had no formal training in social work or foreign policy. These women were motivated by what can best be described as a maternal internationalism, a sense of duty and obligation stemming from their identities as mothers and their belief, that as Canadians, they had a responsibility to improve the lives of children whose vulnerability and suffering they thought could be stopped or at least mitigated by their personal interventions.[8] This ideology, also found in the women’s wing of the peace and nuclear disarmament movement and the foreign relief campaigns sponsored by Canadian women’s organizations throughout the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s, demonstrates the pervasive spirit of maternalism in women’s activism that arose from a passion for child welfare and because it was a familiar political strategy for women to claim a political space and have their voices heard. The action of the maverick mothers was also part of a commitment to the internationalism promoted by the government and embraced by many Canadians after World War II and throughout the Cold War, one that insisted Canada play a role in balancing global peace and security.[9] According to professional social workers and diplomats, a strong commitment to maternalism and internationalism were not valid enough claims to trust the delicate and complicated operation of international adoption to amateur humanitarians. The maverick mothers’ lack of professional accreditation, their bleeding heart mentality, and examples of radical behavior at home and abroad were seen to threaten international adoption as a legitimate form of child saving. Yet concurrently, the authority and respect granted by the women’s identity as mothers granted their cause some creditability, or at least public admiration for their efforts. This in turn gave the maverick mothers a sense of empowerment to challenge their critics and demand cooperation.

Long before the adoption airlifts in the 1970s, Canada had been seen an ideological and physical sanctuary for orphaned, impoverished, and displaced children.[10] For the most part, these earlier waves of child migrations did not result in legal adoptions; instead the children were placed temporarily within Canadian families as guests or sources of free labour until they came of age or circumstances changed that allowed them to return to their home country. In the meantime, the child migrants were expected to benefit from exposure to Canada’s wholesome atmosphere, both environmentally and culturally, a welcome change from famine stricken rural regions, overcrowded slums, or war zones. On the surface these experiences might seem to have little in common with the airlifts from Cold War Asia; however, they reveal a tradition where Canada and Canadian families were positioned as providing a better life for these children than their own parents and nation of origin. As well, many of these incidents of migration dissolved into discourses about the vulnerability of unaccompanied children crossing borders.

These earlier schemes also expose a reluctance to invite the visiting children to permanently become a part of the nuclear and Canadian family. This attitude began to shift after World War II. One reason behind this change was the reforms made regarding domestic adoption. In the postwar period, adoption as a solution to fertility problems had become a less stigmatized practice domestically, and an increasingly popular practice for white middle class couples wanting to start or grow their families.[11] According to traditional social work practices, prospective adoptive parents were normally matched to a child with the same race, religion and, if possible, a similar appearance; but due to a shortage of healthy white infants and more liberal ideas circulating about race and ethnicity, this practice was modified to allow for more diverse adoption matches in the 1950s and 1960s.[12] The Montreal Children Service Centre (MCSC) was a North American leader in the innovative and experimental practice of interracial adoption, and had moderate success in finding adoptive homes for minority and mixed race Canadian children who had previously been marginalized in the adoption market.[13] As they implemented and celebrated these new practices, the MCSC began to receive enquiries about extending their services internationally to assist some of the estimated 13,000,000 children orphaned, abandoned, or separated from their parents during World War II, and the thousands more affected by subsequent civil and Cold War conflicts in Europe and Asia.[14] Many of these early enquiries featured a commitment to the maternal internationalism that would dominate the rhetoric of the maverick mothers a decade later. For example, in 1956, Sheila Morris, a married mother pregnant with her second child, from Drummondville, Québec, wrote to the MCSC explaining she wished to adopt a child from “the Eastern world” because her “deep interest and concern lies with the children in the over populated undernourished countries of the east, especially India and Korea.”[15] Louise Boyd, a childless home-maker from Winnipeg, who had been on a waiting list for years to adopt domestically, also wrote to the MCSC to ask how she could adopt one of “Europe’s homeless kiddies,” so she and her husband could “share our home, our life and our love with some unwanted waif.”[16] Morris’ and Boyd’s enquiries represent the common motivations expressed by Canadians wishing to pursue an overseas adoption in this era. They positioned themselves as having something to offer a needy child — a country, a family, and love — and believed their actions would help fix the world.

Due to Canada’s strict immigration laws, only a handful of international adoption requests were filled before the late 1960s.[17] Until 1965, immigration regulations made it nearly impossible for unaccompanied minors to immigrate for the purposes of non-kin adoption, and due to the racialized hierarchy of Canada’s immigration system, no refugees of any age were welcome from war torn Asian countries outside of the British Commonwealth.[18] These immigration roadblocks did not stop requests from prospective adoptive parents, and in fact as the Cold War grew hotter, the demand increased. Not only did conflicts in Hungary, Greece, Korea, and China serve to expand the numbers and scope of children displaced by war, they also enhanced the political motivations behind the adoptions. Public and private propaganda suggested that the children’s sad fates were the result of being threatened by Communism, and therefore they were especially deserving of being saved. Rescuing these children and proving the West’s superiority in the process was an attractive concept to ordinary Canadians and the government.[19]

Given the Cold War angle, it is not surprising that the first immigration reforms related to international adoption were focused on Chinese children who had been separated from or orphaned when their parents escaped the People’s Republic of China and were now living in overcrowded orphanages in Hong Kong. In the 1960s, the Canadian Welfare Council (CWC), a government advisory body made up of social workers and other child welfare workers, lobbied Prime Minister John Diefenbaker to allow international adoption between Canada and Hong Kong. The cover of one of their pamphlets featured the photograph of a tear-stained Chinese toddler dressed in patched clothes, above the slogan “Communism Failed Her … Will we?”[20] It was perhaps the idea of helping win the Cold War, one heart at a time, that convinced Diefenbaker to finally agree to the CWC’s requests to amend the immigration laws and encouraged the provinces to cooperate by performing home studies on the approximately 200 Canadian couples who had already requested a child from the Far East. By 1965, 25 Chinese adoptees were placed with Canadian families of Chinese and white heritage.[21]

Figure

Over the next few years a small number of children trickled in for adoption from Hong Kong and Korea. However, as the war in Vietnam escalated in the mid-1960s, public interest shifted to rescuing a new and very public pool of displaced children. International Social Services (ISS), an international agency dedicated to dealing with cross-border welfare issues, including international adoption, claimed there were 10,000 homeless children in South Vietnam housed in 63 registered orphanages in 1965.[22] By the end of the American phase of the war in 1973, the orphan population and number of orphanages had almost doubled. Traditionally, orphaned Vietnamese children had been absorbed into extended families or families within the same village, but decades of war had made this form of child care difficult to arrange amongst impoverished and displaced families. The solution was the creation of orphanages funded by the Catholic Church, American military units, and foreign relief agencies.[23] The long-term presence of foreign militaries in South Vietnam meant that like Japan and Korea, there was a growing population of interracial children fathered by foreign soldiers. This was not a new demographic for Vietnam. Over 100 years of French colonial rule had produced a sizable Eurasian population in Vietnam.[24] By the early 1970s, the number of Amerasian children was estimated between 15,000–25,000, most of whom lived with their mothers or extended families. ISS representatives in Saigon noted that most mothers were keeping their half-American children since they were mostly infants, but predicted that as the children grew older, or if their fathers left the country or were killed in the war, the fear of stigmatization or lack of economic resources might lead to their abandonment.[25] This fear was not realized en masse; by 1973 it was estimated that only 1,000 mixed race children lived in orphanages.[26]

The plight of the Vietnamese orphans was well publicized in the Canadian media, and the idea of adoption being the answer to their abandonment was first vigorously pursued by three Montréal housewives Sandra Simpson, Naomi Bronstein, and Bonnie Cappuccino.[27] These white, Christian and Jewish women lived in middle-class neighborhoods in Anglophone communities in and around Montréal. Each of them had young children of their own and wanted to add a Vietnamese orphan to their families. The Cappuccinos had already adopted internationally, a mixed race girl, Machiko, from Japan and Annie Laurie from Korea, while they were living in the United States. According to Cappuccino, she and her family had chosen to move to Canada after adopting Machiko when their congregation in Chicago informed her minister husband that they could stay as long as they did not adopt anymore “controversial,” that is, non-white, non-American children.[28] Presumably they thought Canada would be more tolerant, but they were surprised to find their new home far behind the United States in establishing a structure to adopt overseas. The three women came in contact with each other through their repeated enquiries to various government agencies in Canada and Vietnam, including the CWC, which had arranged the adoptions from Hong-Kong, and the MCSC, which had been the forerunner in interracial adoption. They were frustrated that no one, even the supposed experts, could tell them if it was even possible for Canadians to adopt a child from Vietnam. ISS, which worked closely with the CWC, had never before made placements during a war and were reluctant to start a program in Vietnam. The ongoing war and the frequent regime changes in South Vietnam did not make it an attractive country to establish the necessary diplomatic ties and communications between child welfare agencies. Also, lessons learned from experiences in postwar Korea had shown the ISS that reliance on international foster parent programs and international adoptions stunted the growth of local solutions and possibly contributed to the abandonment of children and the expansion of orphanages. To address their concerns, ISS had their local representatives, Phan Thi Ngoc Quoi, a social worker trained in the United States and England, and Mrs. Raphael, the wife of a British diplomat, research Vietnam’s adoption traditions before they decided whether to become involved.

Quoi and Raphael directed ISS’s attention to Vietnam’s legal and cultural practices that might discourage international adoption. Quoi reported that the country’s adoption law dated back to the sixteenth century and was primarily concerned with issues of kinship and inheritance. The law had been amended in 1959, 1964, and 1965 to clarify rules regarding the adoption of the wards of charitable institutions, primarily for the purposes of adoption to France and America. Adoptions would be approved if the child passed a physical, if the adopters met the age and marriage requirements and had undergone a background check, and if the child’s legal guardian, in most cases the orphanage director, could prove the child was abandoned.[29] Quoi’s report noted the poor living conditions at most orphanages and was concerned many children would not survive the wait to be adopted. Despite her similar acknowledgement, Raphael concluded, “As in all countries at war, it is dangerous to presume any child is an orphan. The Vietnamese sense of family is very strong, and the tradition of the country, if anything, is against inter-country adoption. Therefore no child can be released for adoption unless it can be proved to be either an orphan, which is very rare, or an ‘abandoned child’.”[30] Based on this research, ISS did not foresee international adoption as a service they would provide, except perhaps for mixed race children. Instead ISS believed the priority should be placed on the reunification of children with their relatives.[31] CWC agreed with this plan and advised Canadians inquiring about adoption from Vietnam to consider adopting elsewhere or, instead, make a donation to one of the Canadian relief agencies working in Saigon.[32]

Not only did this answer not satisfy Simpson, Bronstein, and Cappuccino, it also offended them. The media had led them to believe orphaned children were dying and needed to be helped immediately. Additionally, these sources had painted a bleak picture of the children’s living conditions and stoked the fear that due to racism, the plight of half-black, half-Vietnamese children, fathered by African-American soldiers, were particularly precarious. The three women decided to create their own agency to further investigate the possibility of opening doors between Canada and South Vietnam. The women met in the basement of the Unitarian Church directed by Cappuccino’s husband to share advice and moral support about the adoption process and initiated a letter writing campaign to open the proper diplomatic channels. They were bolstered by the news that Lizette and Robert Sauvé, a well-connected francophone Montréal couple — she was a journalist, he was a judge — had used their political connections to adopt the first Vietnamese child to come to Canada, a three-year-old boy, Louisnghia, in 1968.[33]

While they waited to get their own approvals, the group collected diapers, food, and medical supplies to send to orphanages in and around Saigon. After finding it difficult to ship such supplies privately, Bronstein persistently and successfully lobbied Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau to allow the Canadian Air Force to include their relief packages on two humanitarian airlifts to South Vietnam on behalf of FFC.[34] Bronstein felt there was more she could do than pack boxes of donated goods. “I have to help,” she recalled. “This is something that’s inside of me.” She acknowledged that there were needy children to help in Canada, “but people here are not dying of starvation. There are no three year olds [in Canada] that weigh six pounds, seven pounds.”[35] In 1969, Bronstein left her children, including a newly adopted child from Montréal, in the care of her husband and traveled to Vietnam to volunteer in a Saigon orphanage.

In Saigon, Bronstein met Rosemary Taylor, an Australian high school teacher, who had in the last year begun to arrange international adoptions to Europe and had recently opened her own orphanage. Taylor had also formed a partnership with an American woman, Wende Grant, and together they had founded a private international adoption agency, Friends for the Children of Vietnam (FCV). The agency was licensed by social services in Grant’s home state of Colorado, where she had rallied a community of couples interested in adoption, much like FFC had done in Montréal. While volunteering in one of Taylor’s orphanages, Bronstein arranged for FFC to be the Canadian partner of FCV. With Taylor’s help, she was able to adopt into her own family Tam Lien and Tran, a little boy and girl, and brought several other children back for members of FFC. By 1971, FCC had facilitated the adoption of 13 Vietnamese children for their own and other Québec families.[36]

News about FFC’s work in Québec spread across the country. Helke Ferrie, a housewife and mother of three living in Burlington, Ontario, first became interested in adopting internationally when she read about the work of FFC. She related her desire to help the children in Vietnam as stemming from her parents’ experiences in World War II. Ferrie’s German mother and father had opposed Hitler and ended up in a concentration camp where her brother died during the war. She claimed his death and the suffering she later saw growing up in India made her sensitive to the disposability of children’s lives in wartime.[37] Ferrie explained that her philosophy was “based on the conviction that every child has a right to a home of his own and that the family is the best possible setting in which a child may develop his potential. Barriers of race, nationality, religious background and special physical, mental and emotional needs are not recognized as valid if erected to prevent a child from having a family of his own.”[38] Despite this eloquent explanation, her adoption request was denied because Québec was the only province that had policies in place to allow Vietnamese adoptions. Appalled by the lengthy waiting times for home studies and other red tape she encountered in Ontario, Ferrie petitioned the provincial government to move things forward and when that did not work, she went on a three and a half day hunger strike to alert the public to the province’s stalling while children’s lives were at stake. New Democratic Party Leader Stephen Lewis rallied support for Ferrie’s cause in the Ontario legislature, accusing the government of denying foreign adoption for fear that the adoptees would be sickly and end up a burden on the provincial health and welfare system. The combined public and political pressure worked and Ontario slowly began to accept adoptions processed through FFC.[39] While waiting for the paperwork to go through on adopting two school age boys, Ferrie decided to open her own adoption agency, the Kuan Yin Foundation (KYF), named after the Buddhist goddess of mercy for women and children, to assist Ontario families.

The main responsibility of FFC and KYF was to ensure that all the prospective adoptive parents they served in Québec and Ontario (since they were the only agencies they often helped residents of other provinces, too) met the immigration and adoption requirements of the Canadian and Vietnamese governments. They also had their own procedural and moral guidelines for their clients to follow. Since their goal was to bring out the children whom they identified as having the hardest time surviving in their home country, adopting handicapped and mixed race children were the priority. So while FFC tried to match as closely as possible requests for children of certain ages or gender, they refused to match on the basis of race or appearance. FFC’s number one was rule was every client had to be willing to take a half black child. Bronstein recalled how FFC threw out requests from people who said they “were willing to take a child if it didn’t have curly hair, dark skin, or thick lips …. Sorry, we do not fulfill those orders. Families for Children works with families who will accept a child of any racial background, that’s half-black, half-yellow, half-green. Whatever the child is.”[40] Both agencies were also active in attempting to place children with health problems or disabilities.[41]

FFC and KYF continued to operate in Vietnam after the American withdrawal in 1973. They also expanded their adoption programs to Cambodia and Bangladesh, two other nations experiencing great upheaval due to civil war. By 1975, these two groups had brought approximately 600 children to Canada. Amazingly, the Ferrie, Simpson, Cappuccino, and Bronstein families adopted 58 of those children. This generous and extreme act raised quite a few eyebrows from outsiders and put pressure on the families’ finances, marriages, and parent-child relationships. Ferrie’s husband was a well-established doctor; Simpson and Bronstein’s husbands were businessmen with salaries described as “modest”; money was tighter for the Cappuccinos whose only income came from Fred Cappuccino’s ministry. The families made ends meet by purchasing used clothes and toys, buying food in bulk, and, in the case of the Simpsons, depending on the generosity of friends who rented them a 22-room house below market price.[42] The Cappuccinos eventually moved to a log cabin they built in Maxville, Ontario, where they could grow most of their own food.[43] For the adopting mothers, money never seemed to be a factor in the decision to add to their families. Cappuccino recalled how it was the wives who usually called FFC to initiate an adoption, expressing their heartfelt desire to help the children, while their husbands, fretted behind the scenes, worrying about paying the bills or saving for college. Cappuccino dismissed the male half of her clients’ financial concerns by saying, “These overseas babies, it’s silly to talk about their education when they’re [sic] lives are at stake.”[44] She firmly argued it was possible to make do, even in the case of the founders’ own enormous families.

The maverick mothers’ own families pushed the boundaries of conventional home making, something that was not always appreciated by the community or the children themselves. Not only did the adopted children face physical and psychological rehabilitation in Canada, they also had to deal with racism and prejudice from neighbours, schoolmates, and strangers. One time, the Simpsons’ neighbors called the city to complain that they were running an illegal group home in a neighborhood zoned only for residences. This mistake was understandable considering that to most outsiders, the sizeable multi-cultural brood of children did not resemble a ‘normal’ Canadian family. The adoptive Bronstein children recall being teased and spat on at school and called dirty because of their skin colour. One of Bronstein’s biological daughters remembers how notorious her family was in their suburban neighbourhood. People would approach them and ask, “which one of you guys are ‘real’, as opposed to the fake ones ... people couldn’t understand that we were just a family like anyone else.”[45] The Bronstein children also remember missing their mother as she rushed from one country to another helping other children, and leaving her own behind. They were resentful when strangers told them how lucky they were to have a mother like Mother Teresa. “She’s been driven all her life,” one of Bronstein’s grown children said of her mother. “She’s always had something, a project, this or that … if there was some child in need, she wouldn’t hesitate to go.”[46] Bronstein herself admitted that on low days she sometimes resented the responsibility she took on and the time she spent away from her own family, “But then I think if I’m not here, these kids would be dead. And I just feel if I don’t do it, there are not too many people doing it and it has to get done. I can’t change the balance. But if even one or two children have a life that they couldn’t before, and they grow up, then it’s just worth it.”[47] The women juggled their workload by relying on babysitters, help from older children, and their husbands to make it work as best they could.[48]

Caring for their own children was one challenge; another was seeking the approval and support of the federal and provincial governments for their work. From the start, the maverick mothers’ most vocal critics were the professional social workers employed in provincial child welfare departments. Many social workers were reluctant to applaud the work of FFC and KYF because they argued the heightened focus on the exotic tragedies of foreign orphans meant it would be harder to find homes for the Canadian children up for adoption, especially minority children.[49] However, the more troubling issue for the social workers was that women with no professional training ran these private organizations. Social workers feared the private agencies’ inexperience could lead to bad judgement, such as mis-identifying temporarily abandoned children as orphans or rushing through the selection of adoptive homes in order to get the children quickly out of a war zone. There was already a long established rivalry in the United States between amateur philanthropists and professional social workers. Since the 1950s, adoption agencies established by Christian fundamentalist Harry Holt and author and adoptive mother Pearl Buck frequently butted heads with ISS and state welfare departments. Holt and Buck suggested that ISS unnecessarily layered the red tape and therefore delayed adoptions, possibly allowing children to die, while in turn ISS accused the private agencies of poorly selecting homes and gave examples of adoption breakdowns.[50] Each party thought the decision to trust maternal (in the case of Holt — paternal and evangelical) instincts or to follow a professional code was the superior one.

The rivalry between professional and amateur child welfare workers was replicated in Canada. As a result of this tension, the Provincial and Territorial Representatives of Child Welfare Departments met in 1973 to discuss international adoption and, in particular, the tenuous role of private agencies. At this conference, Roland Plamondon, the child welfare representative for Québec, claimed his province had no problem with the private agencies and fully supported the work of FFC. However, representatives from the British Columbia and Ontario governments felt the maverick mothers were a threat and were especially wary of the KYF, whose founder had a habit of radical behaviour and disregard for protocol.[51] Betty Graham, Ontario’s Director of Child Welfare, claimed that one time Ferrie’s sloppy paper work allowed children to arrive in Canada without the proper legal documentation from the Bengalese authorities. She speculated it would take years to determine the legal status of these children and in the meantime their adoptions and citizenship would remain in limbo.[52] More troublesome was when Ferrie admitted to The Toronto Star that she would bend rules to get children to Canada as quickly as possible and implied it did not matter if her clients were not the best candidates for adoption because, “Isn’t a marginal home better than death?”[53] Although Ferrie did not specify, she clearly meant that a marginal home in Canada, where the children could live unmolested by war and in a country with a social security safety net, would be an improvement over their life in a foreign orphanage.. Even though the final decision to approve adoptive homes was up to the provinces, Victoria Leach, the adoption coordinator for Ontario, feared the media attention devoted to the plight of war orphans would produce public pressure to move faster than normal in signing off on homes selected by KYF or FFC.[54] If this happened, social workers worried that it was possible that the children would not be properly matched to the best caregivers and, as a result, have difficulty settling into Canada or worse, be subject to abuse.

Leach spent the 1970s investigating KYF for signs of illegal practices. She surveyed former and current KYF clients, FFC, and other private and public adoption agencies active in the United States and Europe to get their opinion on Ferrie and her work.[55] Leach also travelled to Vietnam and Bangladesh to see the situation on the ground. Most of the results of her investigation are not available due to privacy laws involving the case files of individual adoptees. However, since KYF remained in operation, it does not appear that Leach found enough evidence to support her suspicion that Ferrie had breeched Canadian adoption laws or that her practices had caused adoption breakdowns. Still, the Ontario government remained uncomfortable with international adoption being a welfare solution for developing countries and recommended that the Canadian government increase its foreign aid spending in international child welfare issues so as to help prevent abandonment and alleviate the needs of hungry and homeless children. In the meantime, while international adoptions persisted, Child Welfare representatives in several provinces, led by Ontario, implored that a new federal agency be created to act as a central information system to monitor the international adoption process, develop Canadian standards, and ensure voluntary agencies cooperated fully with all laws.[56]

The federal government also had issues with FFC and KYF that went beyond the concerns of social workers. Diplomats in the Southeast Asian embassies and staff in the Department of External Affairs grew increasingly worried about the unsupervised work of the maverick mothers overseas.[57] They panicked any time they learned that the women had met independently with foreign heads of state and government officials because they feared these independent activities had the potential to affect Canada’s image abroad and even alter Canada’s foreign policy. Simpson recalled how government officials were appalled when FFC called its orphanage in Phnom Penh ‘Canada House’, because they feared that Cambodians would think it was the non-existent Canadian embassy and show up for visas.[58] Diplomats seemed to agree, “There is no doubt that Ferrie and her colleagues had good intentions …. A well-intentioned foreign visitor cannot but feel pity for misery of people, participation for children and war-affected women.”[59] Good intentions, however, had the potential to create international incidents and the idea that the women, whose legitimacy was being questioned at home, had free run in these countries, made the Department of External Affairs nervous. Officials monitored their activities closely, sending telegrams back and forth between local embassies and Canada, for example, when news arrived that Ferrie had resorted to a sit-in outside the private home of a Bangladesh civil servant in order to get his attention.[60] Radical behaviour like this caused External Affairs to distance itself from outward signs of support. When the Canadian Embassy in Dacca passed on Ferrie’s request for a plane to transport sick orphans to Canada, External Affairs, which had yet to confirm that Bangladesh Prime Minister Rahman supported this plan, refused. They intended “to avoid any official CDN [Canadian] government activity in respect to Mrs. Ferries [sic] plans which could be interpreted by GOBD [Government of Bangladesh] as interfering in their internal affairs or running counter to their expressed views as to handling out of country adoptions.”[61]

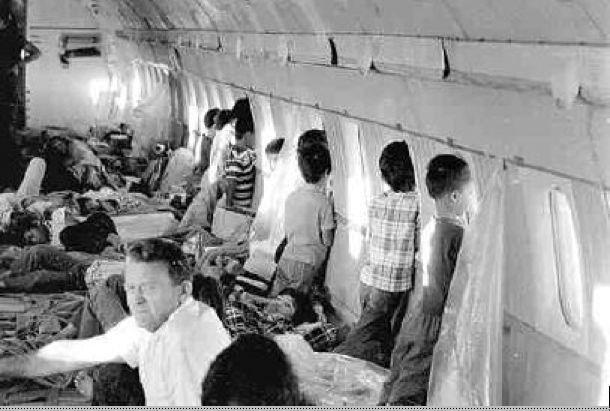

The social workers, diplomats, and maverick mothers continued to maintain cool relations until April 1975, when the predicted victory of Communist forces in Vietnam and Cambodia led to a collaborative government-private agency effort to evacuate the remaining orphans already screened to come to Canada.[62] The evacuation became known as Operation Babylift, the mass departure of approximately 2,600 infants and children to adoptive homes in Canada, the United States, and other Western nations in the two weeks before Saigon fell to the North Vietnamese. This effort was the ultimate child saving gesture, and a blatant attempt to protect children from the supposed evils of Communism. It was assumed that under the new Communist regime, foreign adoptions would be suspended and that in the postwar chaos orphans would not be anyone’s priority, especially those whose features showed American parentage. Although this event sparked cooperation, the aftermath illuminated the controversy still surrounding the facilitation of adoption by the maverick mothers.

As most of her fellow citizens were evacuating South Vietnam, Bronstein arrived in Saigon hoping to fast track the remaining adoptions of FFC children in Vietnam and Cambodia. Under heavy fire from the Khmer Rouge’s attacks on Phnom Penh, Bronstein evacuated the Cambodian children from Canada House and brought them to the FFC orphanages in Saigon. Some of the children were able to leave immediately for Canada, but the majority were delayed due to difficulties arranging for exit and entry visas and transportation. To help FFC, the KYF spent days phoning Canadian donors and were able to raise $76,000 for airfare to help transport the children out.[63] Money was not the only issue. Bombing had stopped most commercial flights and friendly embassies were besieged by long line-ups of foreigners and Vietnamese trying to leave the country.[64] On 3 April 1975, American President Gerald Ford announced he would budget $2,000,000 and provide military planes to fly the remaining children out of Vietnam. Following Ford’s announcement, the Canadian government offered to cover the cost of the transportation for the rest of the adoptees destined for Canada. When news about the airlifts hit the press, provincial child welfare agencies from coast to coast received hundreds of phone calls from Canadian families volunteering to adopt an airlift child. For their part, FFC and KYF assured the provincial authorities they already had homes long picked out for the children scheduled to come to Canada and there would be no spontaneous placements.

One day after Ford’s announcement, the first flight to leave Saigon, carrying 328 children and their adult escorts, crashed just after take-off, killing 153 of the passengers. Bronstein had been scheduled to take a group of Cambodian children on that plane; at the last minute, however, Ernest Hébert, the Canadian Chargé d’Affaires in Vietnam, offered the use of a Canadian plane. The crash devastated the adoption community. Bronstein immediately rushed to the crash site to help survivors and identify the bodies of the children and her colleagues. She also hurried to inform waiting parents in Canada of the last minute change in plans that saved their children from the crash, though for a few days there was confusion over which children had been on the flight and newspapers incorrectly reported that 34 children destined for Canada had been killed, when in fact all those children had been on the plane arranged by Hébert.[65] As tragic as the crash was, Bronstein reminded observers, “Every time I was there [in Vietnam and Cambodia] I had babies to bury. There were children dying all the time. And so this was a terrible crash and of course a number of children died, but at any one day in Saigon, the same amount of children die. We have been seeing it for so many years and everyone else has seen it once.”[66] The tragedy of the crash cast a shroud over the rest of the airlifts and raised concerns about the hastiness of the departures that forced children to travel in cargo planes without the proper safety features. Unease also arose over the children’s status: was it possible in the mad rush to leave that non-orphaned children been taken?

In the days and weeks after Operation Babylift, criticism exploded across the United States and Canada. In California a class action suit was launched on behalf of three siblings who claimed they still had a living parent in Vietnam.[67] Further investigation by United States Immigration and Naturalization Services found that out of the 1,667 children brought to the United States, 233 had insufficient documentation.[68] These discoveries raised questions and concerns about the potential carelessness of the amateur adoption workers that led to non-orphans, children temporary placed in an orphanage or separated from their parents, being adopted prior to and during Operation Babylift. The children brought to Canada were not affected by this lawsuit, but the case caused Canadian immigration officials to review their paperwork and Hébert, the Foreign Service officer who arranged one flight for the Canadian children, testified in a provincial court. Hébert stood by the work of FFC and claimed that to his knowledge, “the aforesaid group of 57 children left Vietnam legally for the purpose of adoption in Canada, with full knowledge and consent of the recognized Vietnamese government.”[69] Despite Hébert’s statement, it was apparent that in the heat of the moment mistakes had been made on all sides, which FFC and KYF excused as unavoidable in the haste in which they left Saigon; but they insisted that no shortcuts had been taken that placed the children in any harm. They retorted that the real danger had been the encroaching war and the arrival of the Communists from which the children had been protected.

The American lawsuit was eventually dismissed due to lack of evidence, but rumours about the airlift persisted and introduced debates about the morality of international and interracial adoptions. Were the adoptions rescue or thefts? Was it wrong to raise a child outside of their culture? Canada’s Cold War ideology had changed between the first adoptions from Hong Kong and Operation Babylift. The simplified fairy tale of rescuing innocent children from the evils of Communism was complicated by widespread public opinion about how harmful the American intervention had been in Vietnam. Additionally, the civil rights movement in Canada and the United States had been influential in raising awareness about racial discrimination and the history of white domination over marginalized racial groups. This connection was implied in a cartoon featured in a Native American periodical Akwesasne Notes, published by the Mohawk Nation in 1975. The drawing features a stodgy middle-aged white couple contemplating a display of Vietnamese children as if they were for sale in a store. Signs on the display read: “Vietnam Orphan Souvenirs,” “Remember Your Stay in Vietnam Forever,” and “Limited Supply.”[70] The wife, pointing to a child on the top shelf, says to her husband, “This one would look nice in the den.” That this image appeared in a magazine written by and for aboriginals at the height of the Red Power movement suggests that the editors of Akwesasne Notes saw their own marginalization, disenfranchisement, and the removal of their children to non-aboriginal homes connected to the exploitation of the Vietnamese. This cartoon reinforces Sollinger’s arguments about how children from the developing world become commodified through the process of international adoption.[71] Representatives from FFC or KYF would most likely have read the cartoon differently. Whether they agreed or disagreed with the portrayal of adoption as a market transaction, they would have added the caveat that at least the children were alive to be commodified.

Figure

The arguments that the Babylift children faced an immediate threat in postwar Vietnam or were better off in Canada were questioned by other Canadians who had been active in Vietnam. Nancy Pocock, a member of the Voice of Women peace group, which had ties to women’s groups in North Vietnam, saw Babylift as another form of Western exploitation, claiming, “The orphans were there all the time. We’ve been killing them with Canadian-made arms. I don’t think it’s a good idea to bring them over. Think of the culture shock.”[72] Claire Culhane, an outspoken critic of the war in Vietnam, also found it ironic that the Americans were helping the same children who they orphaned in the first place. She asked the Canadian Minister of Immigration, to “a) attempt to return the children to their departure areas; and b) to forward the largest possible sums of aid to cover medical, housing, food, clothing needs of remaining children who are suffering partially as a result of the arms sales we have profited from so richly in the past two decades.”[73] The adoption advocates from KYF and FFC responded to their critics by acknowledging that under ideal circumstances, a child should not have to cross borders to find a family, and resources should be dedicated to encourage birth mothers to keep their babies or to find adoptive homes within their own nations. In wartime, however, they argued that these choices were unaffordable luxuries. In a televised interview with the CBC’s Barbara Frum, Bronstein explained that her agency took out the children that they were convinced would have the hardest time living in postwar Vietnam: older children, sick children, handicapped children, and especially mixed race children. She also disagreed with claims that it was wrong to remove children from their birthplace because in these circumstances, “I can’t really say that babies have a culture at that age and certainly they don’t get this in an orphanage.”[74]

In the aftermath of Operation Babylift, Canadian participation in international adoption changed. As a result of the discomfort over current procedures and their potential negative affects on Canada’s foreign policies and reputation, the Department of External Affairs created a new federal agency, the National Adoption Desk, in 1977, to act as a central registry for international adoption information, coordinating and tracking requests from Canadians wishing to adopt internationally, and forwarding them to the appropriate provincial and federal departments. Ideally, this change was supposed to eradicate or, at the very least, control private agencies, and was seen as a welcome intervention by social workers serving in child welfare agencies in all provinces except Québec, which refused to participate on the basis that it infringed on its constitutional right to manage child welfare provincially.[75] Despite their hope that the Adoption Desk would end the need for private agencies, FFC and KYF persisted in their work and prospective adoptive parents continued to depend on their services. It appears they filled a niche not offered by either the provincial adoption services or the Adoption Desk. Having been at the forefront of international adoption in Canada for so long, FFC and KYF offered their clients confidence, experience, and a personal touch. Additionally, as advocates for parents and children, the founders did more than just help with paperwork; they were themselves living commitments to the principles of international adoption and, as adoptive mothers, they could offer practical advice and emotional support. FFC agreed to work with the Adoption Desk and invited its Director, Derek White, to visit their new orphanage in India.[76] Meanwhile, Ferrie felt the added layer of bureaucracy only further slowed the waiting period to bring children to Canada and appealed to Prime Minister Trudeau to close the Adoption Desk. Her request was ignored and rumours about the legitimacy of Ferrie’s practices continued to plague KYF. Hoping for less scrutiny, Ferrie relocated her family and program across the border to Michigan in 1978, though it is unknown to the author what the results of her subsequent projects have been.[77] FFC continued to make recommendations to change the Adoption Desk’s configuration, but it did not fight against it as KYF did, perhaps because it knew it was free to operate as usual in its home base of Québec.

The voices of the one group that might truly settle the debate about the legitimacy of this adoption process were not captured during the Babylift scandal. Beyond the adults’ interpretations of their tears and smiles, the adoptive children themselves were almost invisible in the contemporary public record. As they grew older, however, their personal experiences were shared with researchers and the media. One of the first examples was a 1998 study that interviewed over 100 international adoptees brought to Canada in the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s, which concluded that the children grew up to be relatively well adjusted.[78] More recently, the Babylift children have organized and spoken about their experiences. In 2005, 30 years after he was airlifted to Toronto, Thanh Campbell attempted to reunite the children who were evacuated from Vietnam on his flight in April 1975. Three years later he had connected with 34 out of 57 flight mates. He also met with Leach, the social worker from Toronto’s Children Services, who had accompanied them on their flight. Leach, who had been so critical of how this wave of international adoption had been handled, was pleased to see the children grown up and doing well. “They will always be part of my good memories, but it fills me with great joy to know they have their own families now,” she stated in reference to Campbell and other adoptees now having their own children.[79] Leach would be less impressed with what happened next. In 2008 Campbell was also reunited with his biological brothers and father, Nguyen Thanh Minh, a retired teacher in Ho Chi Minh City, who had seen a photo of Campbell in a Toronto Star article about the Babylift reunion. For 30 years Minh had searched for the son that he and his wife had given up temporarily to an orphanage, along with their two older sons, for safe keeping during the war. When Minh went to reclaim his children after the war, he found his youngest son missing from the orphanage and was told he had most likely been adopted. A DNA test confirmed they were indeed father and son.[80] According to an interview with the Hamilton Spectator, Campbell accepted these revelations with grace, made plans to visit his birth family in Vietnam, and had explained to his own four children that they now had three grandfathers. Campbell’s experience is proof that all the Babylift children were not real orphans. His story also echoes Dubinsky’s insistence that buried under all the global politics and drama of international adoption, there are real children whose experiences need to be understood and remembered separately.[81]

It does not appear that any representatives from FFC commented publicly on Campbell’s discovery. Since their contentious activities in the 1970s, Bronstein, Simpson, and Cappuccino have become respected humanitarians in the field of international child welfare, and each have been honoured with the Order of Canada. This newfound legitimacy came from the continued popularity of international adoption among Canadians. In addition, enough time has passed to make what had happened in Vietnam, both the war and Operation Babylift, less notorious. International adoption continues to remain a controversial act in Canada and abroad, especially as it expanded throughout the 1980s and became viewed as less an act of child saving and more as a means to supplement a domestic adoption market, which had few infants available for adoption. Still, it is important to recognize that the roots of the controversy in Canada began not with concerns about the children’s best interests or international relations, but with the government’s disbelief that a group of mothers could know better than professional social workers or diplomats. Despite this critique, the founders of FFC and KFY overcame public scrutiny, lack of state support, and personal challenges to fulfill their maternalistic and internationalist vision. The movement and placement of an estimated 700 children with Canadian families in the 1970s is an important testament to maternal internationalism as a powerful force to reckon with at home and broad.

Parties annexes

Biographical Note / Note biographique

Tarah Brookfield

Tarah Brookfield defended her Ph.D. thesis in September 2008 at York University.

Tarah Brookfield a soutenu sa thèse de doctorat en septembre 2008 à l’Université York.

Notes

-

[1]

“Sandra and her Kids,” The Nature of Things, CBC TV, broadcast 1983.

-

[2]

Mark Abley, “Mother Lode: Sandra Simpson has raised 32 children,” The Montreal Gazette, (3 October 1999).

-

[3]

“Sandra and her Kids.”

-

[4]

Veronica Strong-Boag, Finding Families – Finding Ourselves: English Canada Encounters Adoption from the Nineteenth Century to the 1990s (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006); Barbara Melosh, Strangers and Kin: The American Way of Adoption (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2002); E. Wayne Carp, Adoption in America: Historical Perspectives (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2002).

-

[5]

Rickie Sollinger, Beggars and Choosers: How the Politics of Choice Shapes Adoption, Abortion, and Welfare in the United States (New York: Hill and Wang, 2001), 20–3.

-

[6]

Laura Briggs, “Mother, Child, Race, Nation: The Visual Iconography of Rescue and the Politics of Transnational and Transracial Adoption,” Gender and History, 15, no. 2 (August 2003): 180.

-

[7]

Karen Dubinsky, “Babies without Borders: Rescue, Kidnap, and the Symbolic Child,” Journal of Women’s History 19, no. 1 (Spring 2007): 142, 148.

-

[8]

For a more in-depth look at female activists’ use of maternalism and internationalism, see Tarah Brookfield, “Protection, Peace, Relief and Rescue: Canadian Women’s Cold War Activism at Home and Abroad, 1945–1975” (Ph.D. diss., York University, 2009).

-

[9]

Don Munton and Tom Keating, “Internationalism and the Canadian Public,” Canadian Journal of Political Science 34, no. 3 (2001): 517–49.

-

[10]

For example, see Fleeing the Famine: North America and Irish Refugees, 1845–1851 (Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group, 2003); Joy Parr, Labouring Children: British Immigrant Apprentices to Canada, 1869–1924 (Montréal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1980); Geoffrey Bilson, The Guest Children: The Story of the British Child Evacuees Sent to Canada During World War II (Saskatoon, Sask.: Fifth House, 1988);. Fraidie Martz, Open Your Hearts: The Story of Jewish War Children in Canada (Montréal: Véhicule Press, 1996).

-

[11]

Charlotte Whitton, “What You Should Know About Child Adoption,” Chatelaine (April 1948): 26, 102.

-

[12]

Patti Phillips, “‘Financially irresponsible and obviously neurotic need not apply’: Social Work, Parental Fitness, and the Production of Adoptive Families in Ontario, 1940–1965,” Histoire sociale / Social History, 78 (November 2006): 343–6.

-

[13]

Karen Dubinsky, “‘We adopted a Negro’: Interracial adoptions and the Hybrid Baby in 1960s Canada,” in Creating Post-war Canada: Community, Diversity and Dissent, eds. Magda Fahrni and Robert Rutherdale (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2008), 268–9.

-

[14]

Everett M. Ressler, Neil Boothby, and Daniel J. Steinbock, eds. Unaccompanied Children: Care and Protection in Wars, Natural Disasters, and Refugee Movements (New York: Oxford University Press, 1988), 12.

-

[15]

Library and Archives Canada (LAC), Canadian Council on Social Development (CCSD) Fonds, MG 28 I 10 , vol. 61, file 491, Adoption — General Information Requests 1956–1963, Letter from Morris to McCrea, 16 April 1956.

-

[16]

Ibid., vol. 206, file 6, ISS International General Correspondence Data re Branches — Staffing the Committee 1960–1961, Letter from Boyd to Murphy, 20 July 1959.

-

[17]

Strong-Boag, 193–4.

-

[18]

Ninette Kelly and Michael Trebilcock, The Making of the Mosaic: A History of Canadian Immigration Policy (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1998), 315, 328–9.

-

[19]

One example of this attitude is Louis St. Laurent’s speech promoting investment in Asia as solution to winning the Cold War. Louis St. Laurent, “Consequences of the Cold War for Canada,” speech to the Canadian Club in Toronto, 27 March 1950, <http://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/primeministers/h4-4015-e.html>, accessed May 28, 2008.

-

[20]

Social Welfare History Archives (SWHA), International Social Services (ISS) Fonds, SW109, box 11, Adoption Manual and Other Printed Material, “Communism Failed Her … Will We?” no date.

-

[21]

LAC, CCSD, MG 28 I 10 , vol. 205, file 12, ISS Child Adoption Placement Services — Hong Kong, Korean and Foster Care Costs, 1966–1969 and Canadian Welfare Council — Procedure in Hong Kong “Orphan Refugee” Adoptions, May 1964.

-

[22]

Paul R. Cherney, “The Abandoned Child in Asia,” Canadian Welfare (March–April 1966): 82.

-

[23]

LAC, Adoption Desk, RG 29, vol. 3539, file 4122-1-3 Pt. 2, Ontario Ministry of Community and Children Services, “Report on Adoption of Vietnamese Children,” September 1973, 7–8.

-

[24]

SWHA, ISS, SW109, box 38, Country: Vietnam, Conference on the special needs of Children in Vietnam, Report of Eurasian under French, Marcelle Trillat, ISS France, 19 July 1971.

-

[25]

LAC, CCSD, MG 28 I 10, vol. 204, file 8, ISS Board of Directors: International Council Executive Committee 1959–1969, Minutes, Directors’ Meeting — ISS, Geneva, 14 April 1966.

-

[26]

Ibid., Adoption Desk, RG 29, vol. 3539, file 4122-1-3 Pt. 2, Ontario Ministry of Community and Children Services, “Report on Adoption of Vietnamese Children”, September 1973, 9.

-

[27]

For example, see “Vietnam,” Weekend Magazine, 17, no. 21 (27 May 1967); Peter Sypnowich, “Canada awakens to the agony of Viet Nam’s maimed children,” Star Weekly (29 April 1967), 2–4; “Special Issue on Vietnam,” Macleans (February 1968). There were also two short films released by the National Film Board that looked at mixed race and homeless children: The Sad Song of Yellow Skin (1970) and The Streets of Saigon (1973).

-

[28]

Sheila Gormely, “Canada brings in 100 babies from war-torn Asian lands,” The Toronto Star (3 February 1973), 4.

-

[29]

SWHA, ISS, SW109, box 38, Country: Vietnam, ISS International Vietnam Administrative Files, 1964–1965, Regulations on Adoption in South Vietnam provided by Mrs. Herbert Baumgartner, American Embassy, Family Law (Luat Gia Dinh) No. 1/59 Dated January 1959.

-

[30]

LAC, CCSD, MG 28 I 10 , vol. 206, file 10, ISS International General Correspondence Data re Branches — Staffing the Committee 1966, Report on the Work of ISS in Vietnam from July 1965–September 1966 by Mrs. A Raphael, 18 October 1966, 4.

-

[31]

Cherney, 83–5.

-

[32]

LAC, CCSD, MG 28 I 10, vol. 206, file 12, ISS International General Correspondence Data re Branches — Staffing the Committee 1968, Memo to Directors of Child Welfare, from CWC-ISS, 6 June 1968.

-

[33]

Lolly Golt, “A Family is a Child’s Best Gift,” Weekend Magazine (20 November 1971): 19.

-

[34]

Rosemary Taylor and Wende Grant, Orphans of War: Work with the Abandoned Children of Vietnam 1967–1975 (London: Collins, 1988), 95.

-

[35]

“Naomi Bronstein,” interview on Dan Turner: For the People, CBC TV, broadcast 31 January 1983.

-

[36]

Golt, 20.

-

[37]

Gormely, 4.

-

[38]

Archives of Ontario (AO), Community and Social Services, RG 29-110, box 3, Kuan Yin Foundation Newsletter, 1976, 2.

-

[39]

“Helke Ferrie: Crusader for the World’s Children,” Chatelaine (October 1978): 33.

-

[40]

“Naomi Bronstein,” interview on Barbara Frum, CBC TV, broadcast 5 June 1975.

-

[41]

Gormely, 1.

-

[42]

“Sandra and her Kids.”

-

[43]

Dorothy Sangster, “The Little Family that Grew and Grew,” Chatelaine (November 1990): 145.

-

[44]

Gormely, 1.

-

[45]

A Moment in Time: the United Colours of Bronstein, Judy [Jackson] Films, 2001.

-

[46]

Ibid.

-

[47]

“Naomi Bronstein.”

-

[48]

The Bronsteins divorced in the 1990s, but not until after all their children had grown up. Ferrie’s husband routinely accompanied her abroad to administer medical check-ups for the orphans. Simpson’s husband did the weekly grocery shopping, however he drew the line at other household chores and child care responsibilities, explaining “the odd baby I’ve cuddled years ago but … Sandra’s the master of that.”

-

[49]

LAC, Adoption Desk, RG 29, vol. 3539, file 4122-1-3 Pt. 1, Betty Graham, Note for File by South Asia Division — Ontario Government Views of the Adoption of Bangalee children, 29 September 1972.

-

[50]

SWHA, ISS, SW109, box 10, Children: Independent adoption Schemes, Holt, Harry, 1955–1957, Vol. I. Pearl Buck, “The Children Waiting: The Shocking Scandal of Adoption,” Woman’s Home Companion (September 1955): 129–32; and Letter from Andrew Juras, Child Welfare Director, State of Oregon, to ISS, 4 May 1956.

-

[51]

LAC, Adoption Desk, RG 29, vol. 3539, file 4122-1-3 Pt. 2, Minutes of the Meeting of Provincial and Territorial Representatives of Child Welfare Departments, June 1973, 8.

-

[52]

Ibid., Pt. 1, Note for File by South Asia Division — Ontario Government Views of the Adoption of Bangalee children, 29 September 1972.

-

[53]

Gormely, 1.

-

[54]

“Children’s Aid accused of delaying adoption of 25 war orphans,” The Toronto Star (4 October 1972), 97.

-

[55]

LAC, Adoption Desk, RG 29, vol. 3540, file 4122-1-3 Pt. 9, Department of Health and Welfare, Doris Waltman, “An examination of adoption policy and services on local, inter-provincial and international levels,” 30.

-

[56]

Ibid., vol. 3539, file 4122-1-3 Pt. 2, Minutes of the Meeting of Provincial and Territorial Representatives of Child Welfare Departments, June 1973, 8.

-

[57]

Ibid., Pt. 1, Memo from Mrs. D. Zarski, Director Welfare Services from Ramona J. Nelson, Consultant on services to children and Youth, 7 February 1973.

-

[58]

Abley, A1.

-

[59]

LAC, Adoption Desk, RG 29, vol. 3539, file 4122-1-3 Pt. 1, Confidential Memo via telex to EXTOTT GPS from James Bartleman, Acting High Commission, Bangladesh 2 February 1973.

-

[60]

Ibid.

-

[61]

Ibid., Telex To BNGKK from EXTOTT, 13 October 1972.

-

[62]

“Adoption Orders Inundate Officials,” The Globe and Mail (5 April 1975), 15.

-

[63]

“Confusion surrounds orphan flight,” The Globe and Mail (5 April 1975), 14.

-

[64]

Taylor and Grant, 143–9.

-

[65]

“Crashed Jet had 34 headed to Canada,” The Globe and Mail (5 April 1975), 1.

-

[66]

“Naomi Bronstein.”

-

[67]

Taylor and Grant, 229.

-

[68]

SWHA, ISS, SW109, box 38, Country: Vietnam, Vietnam Claim Returns Baby lift April ’75. Article by Nancy Stearns in Monthly Focus, reprinted in the newsletter for the National Council of Organizations for Children and Youth, 1975.

-

[69]

LAC, Adoption Desk, RG 29, vol. 3539, file 4122-1-3 Pt. 8, Provincial Court — in the matter of Thi Kieu Diem Nguyen et al., 9 September 1975.

-

[70]

Cartoon by Ken Bendis, Akwesasne Notes (1975). Thanks to Karen Dubinsky for sharing this image.

-

[71]

Sollinger, 20–3.

-

[72]

“The War Waifs: Should South Vietnamese Orphans be brought to Canada for Adoption?” The Toronto Star (12 April 1975), B1.

-

[73]

McMaster University Archives (MUA), Claire Culhane Fonds, box 32, Correspondence 1975, Letter from Culhane to Andras, 30 April 1975.

-

[74]

“Naomi Bronstein.”

-

[75]

LAC, Adoption Desk, RG 29, vol. 3539, file 4122-1-3 Pt. 2, Report to Mrs. D. Zarski from Ramona Nelson and Derek White, Re-Function and Operation of the Federal Adoption Desk — a to do list, 1975.

-

[76]

Ibid., Pt. 12., Letter from White to T. Hunsley, 27 February, 1978.

-

[77]

AO, Community and Social Services, RG 29-110, box 3, Kuan Yin Foundation, Letter from the KYF to Child Welfare Branch, Toronto, 20 December 1979.

-

[78]

Anne Westhues and Joyce S. Cohen, “The Adjustment of Intercountry Adoptees in Canada,” Children and Youth Services Review, 20, nos. 1–2 (1998): 130.

-

[79]

Jonathan Heath-Rawlings, “Two Orphans, Two Countries, One Quest,” The Toronto Star (17 April, 2005).

-

[80]

Figure

John Burman, “Lost & found: Orphan No. 32: Reunited with family he didn’t know he had,” Hamilton Spectator (9 February 2008).

-

[81]

Figure

Liste des figures

Figure

Figure

Figure

Figure