Résumés

Résumé

Cet article propose un tour d’horizon des usages des dessins d’enfants dans l’histoire de l’aide humanitaire à l’aide d’exemples, du Canada et d’ailleurs, tirés des recherches de l’auteure. Il se penche à la fois sur les usages des dessins par diverses organisations au cours des dernières décennies et sur les emplois que les historiens en ont faits. À l’aide d’outils empruntés à plusieurs disciplines, il propose des clefs de compréhension qui permettent de réfléchir à l’histoire de la psychologie enfantine, de la pédagogie, de l’art enfantin, des relations humanitaires entre générations, des droits des enfants et des perceptions juvéniles lors d’interventions humanitaires. Il dresse un historique du médium, de ses promoteurs ainsi que de ses détracteurs et propose un ensemble de pistes pour identifier, malgré les obstacles, des traces d’expressions enfantines.

Abstract

This article offers a broad survey of the use of children’s drawings in the history of humanitarian aid, thanks to select examples taken from the author’s research in Canada but also elsewhere in the world. It examines how various organizations, over the last decades, and historians have treated these drawings. Borrowing concepts and methods from a host of disciplines, it helps understand the history of childhood psychology, pedagogy, children’s art, intergenerational humanitarian relations, children’s rights, and juvenile perception in the course of humanitarian interventions. The article uncovers the history of the medium, its promotors, and detractors and further proposes pathways to identify, despite the hurdles, hints of genuine children’s expression.

Corps de l’article

Introduction

Dans l’histoire de l’aide humanitaire, le dessin d’enfant est omniprésent, pour le meilleur et pour le pire. Le pire est une « pornographie de la pauvreté », une industrie de la pitié simpliste et paternaliste, qui ne parle que des symptômes des inégalités et des solutions plutôt que des causes. Dans ce contexte, la mobilisation des actions et des images d’enfants peut représenter une façon, parmi les plus simplistes, de lever des fonds pour l’aide entre nations. Le meilleur, c’est une communication entre donateurs et receveurs d’aide, autonomes et réfléchis de part et d’autre[1]. Dans ces circonstances, l’expression des enfants a un autre rôle, celui de questionner les stéréotypes et d’ouvrir des possibilités. Ce survol des rôles multiples et contradictoires de l’expression picturale enfantine dans l’histoire de l’humanitaire montre aussi que l’aide internationale fait partie intégrante de l’histoire du dessin, comme c’est le cas pour son parent mieux étudié, la photographie humanitaire. Plus encore, les dessins d’enfants produits ou utilisés au cours d’expériences humanitaires ont participé au développement de plusieurs types d’expertise, de la psychologie à la pédagogie, en passant par la philosophie, l’histoire de l’art, l’anthropologie et les arts plastiques. Cette étude emprunte à ces savoirs et présente de rares tenants de ces disciplines qui ont analysé le genre du dessin d’enfant humanitaire en tant que tel.

Cet effort de mise en contexte d’oeuvres enfantines et d’enquête sur leur signification pour l’histoire de l’aide internationale est assez nouveau. Il prend pour point de départ les dessins rencontrés au cours de mes recherches sur l’histoire des droits des enfants et sur le passé des organisations non gouvernementales (ONG). J’aborderai ici les aspects suivants : l’identité des auteurs et la variété des rôles que les dessins ont pu avoir dans leur propre vie, les contextes, les conditions et les responsables de la production des oeuvres et de leur collecte, les publics – anticipés ou non – par les différents acteurs, les thèmes, les styles, les modalités de sélection, les chaines de circulation, les contextes d’exposition, de publication et d’archivage. J’observerai aussi la nature des réceptions des dessins d’enfants, contemporaines et postérieures, les problèmes d’éthique et de propriété intellectuelle reliés à leur usage, la question de l’existence d’aspects spécifiques à ce type de dessin, ainsi que les types d’interprétations qu’en font les historiens.

Dessins des missions

Dans la mesure où l’on considère les missionnaires comme les premiers humanitaires, les dessins réalisés par leurs jeunes pupilles représentent les plus anciens documents de cette analyse. Ceux de Wu Lan, l’un des premiers immigrants Chinois aux États-Unis arrivé en Nouvelle-Angleterre en 1823 pour étudier à la Cornwall Foreign Mission School, ont été étudiés par l’historienne de l’enfance Karen J. Sanchez-Kepler. En vue de lever des fonds, l’école missionnaire eut recours à des expositions de performances et d’oeuvres enfantines. Sanchez-Kepler a retrouvé 19 aquarelles attribuées à ce jeune homme de 19 ans accompagnées de textes anglais et cantonnais, autant de collaborations à un « friendship album » collectif destinées à une institutrice aimée[2]. Les outils de la littérature anglaise et postcoloniale permettent d’identifier des bribes d’expression personnelle à travers les exercices de recopiage que la confection de tels albums nécessitaient, en dépit de la lourdeur des codes pédagogiques et nationaux. La juxtaposition réfléchie des idiomes langagiers et picturaux par Wu Lan donne des clés de compréhension des amitiés et des inquiétudes d’un jeune homme ordonnant la rencontre des deux mondes à laquelle il participait.

L’histoire de l’enseignement colonial nous apprend que l’espace de liberté relative nécessaire à l’expression enfantine fut rarement donné aux pupilles non-européens des missions chrétiennes. Pourtant, les oeuvres de Wu Lan montrent que le fait même de peindre ou d’écrire « opens to other possibilities of expression and gestures toward other possible relations[3] ». Selon le sociologue et historien de l’éducation Alexis Artaud de La Ferrière, cette ouverture même, tout comme la nature active du récit enfantin, représenterait « the source of the rhetorical and emotional power conveyed by these documents[4] ». Ainsi, les dessins interpelleraient le public humanitaire pour des raisons différentes de celles des représentations passives d’enfants pauvres, elles aussi typiques des campagnes humanitaires. Toutefois, de La Ferrière ne présume pas de la vérité de cette expression : ce qui compte, écrit-il, c’est que « We hear (or think we hear) the children’s own voices[5] ». Nous reviendrons sur ce point.

Cent cinquante ans plus tard, l’aventure des dessins des enfants du pensionnat d’Alberni de Colombie-Britannique, récemment relatée au Musée canadien de l’histoire dans le cadre des travaux de la Commission de vérité et réconciliation du Canada (2008-2015)[6], porte aussi sur une collection d’expressions enfantines rescapées de l’histoire missionnaire. Dans ce cas-ci, il s’agit cependant d’oeuvres longtemps cachées, à charge émotionnelle différée. Grâce aux travaux de la Commission, on avait compris que l’art des adultes ayant survécu aux pensionnats autochtones pouvait détenir « un fort pouvoir culturel et social », en servant non seulement de témoignage et de moyen de guérison rétrospectifs, mais encore d’occasion d’éducation et de communication[7]. La Société de soutien à l’enfance et à la famille des Premières Nations du Canada a aussi fait un appel aux enfants du pays pour des productions artistiques sur la réconciliation, appel qui a servi de base au logo de l’association[8]. On a également documenté le cas d’artistes autochtones ayant reçu ou donné des cours dans les institutions religieuses du passé; ces cours auraient offert aux pensionnaires tantôt un refuge, tantôt un moyen pour développer l’estime de soi[9]. Néanmoins, sans la découverte de ces dessins par l’anthropologue Andrea Walsh de la University of British Columbia, il aurait été difficile d’espérer que des témoignages d’enfants produits au moment de leur internement aient survécu à la fermeture des pensionnats. Or, il y a cinq ans, Robert Aller, artiste et instituteur d’art bénévole au tournant des années 1960[10], dévoila avoir conservé 47 peintures d’enfants pensionnaires d’une institution de l’Île de Vancouver, l’Alberni Indian Residential School, et les montra à Walsh qui réussit à prendre contact avec la plupart de leur auteur ou leurs descendants.

La journaliste locale Judith Lavoie a recueilli les propos de l’un des créateurs, aujourd’hui Chef héréditaire de la Première Nation Ahousaht de l’Île de Vancouver. Son témoignage montre que, plus que l’acte de dessiner, c’est la protection qu’offrit le responsable de la classe de dessin, loin de la violence sexuelle du dortoir, qui semble avoir motivé les élèves :

[Maquinna Lewis] George… was sent to Alberni Indian Residential School when he was about six years old. Soon after his arrival, he jumped at the chance of taking art classes because they would get him out of early bedtime : « They used to put us to bed at 6 p.m. and the art classes were between 7 p.m. and 10 p.m. », he recalled. It was during the evening that most sexual abuse happened — dorm supervisor Arthur Henry Plint was eventually branded a « sexual terrorist » by the courts. « I credit those classes with keeping me from being abused », said George, who was physically abused at the school but escaped the sexual abuse that many of his friends and siblings suffered... « I want my story kept alive », said George, who remembers the kindness shown to him by volunteer art teacher Robert Aller as being in stark contrast to the harsh realities of life at the school[11].

Au fil du temps, ces feuilles peintes ont donc pris des sens nouveaux. Étudiées par la Commission et exposées à travers le pays, les expressions artistiques de jeunes victimes comptent au nombre des traces d’un scandale occulté pendant des décennies. L’événement du 1er juin 2015 a inclus l’exposition des oeuvres, de même que « l’incroyable histoire du rapatriement de ces peintures telle que racontée par les survivants eux-mêmes et le rôle que leur art a joué pour communiquer la vérité et favoriser la réconciliation[12] ». Les concepteurs de l’exposition avancent que « artworks dealing with trauma contribute to healing either the artist or the public[13] ». La question de leur valeur thérapeutique au moment de leur production est peu reconnue et on peut souhaiter, avec les experts des études sur la culture, qu’ils deviennent des objets d’étude dans le champ de recherche sur l’histoire des traumatismes[14].

Après leur découverte, certaines peintures d’Alberni sont retournées aux auteurs, d’autres ont pris le chemin des archives. Les aspects éthiques de la propriété des dessins ont eux aussi une histoire : toutes les oeuvres d’Alberni sont devenues les objets, il y a deux ans, d’une cérémonie de rapatriement, pendant laquelle les descendants des enfants peintres portaient les dessins devant eux, comme gages de transmission de la mémoire et, possiblement, signe de « vitalité culturelle[15] ».

Les peintures d’Alberni, comme le rappelait le Chef Ahousaht interviewé par le Times Colonist, attestent aussi de la générosité d’un professeur blanc qui, en plus d’encourager leur production, a pressenti l’importance de les conserver et a demandé à chacun de ses élèves de lui laisser une oeuvre. Robert Aller fut aussi philanthrope (professeur d’art dans les prisons et pour le YMCA) et champion de l’art autochtone. Le travail auprès des enfants « dont la curiosité et la spontanéité rencontraient la sienne » et à qui il préférait donner des matériaux pour « leur laisser découvrir leur propre mode d’expression » a constitué la part la plus joyeuse de sa carrière. Sous sa tutelle, des enfants qui étaient autrement punis à la mention de leur culture d’origine eurent une occasion unique de « se rappeler du peuple dont ils provenaient… » en peignant des scènes de leurs souvenirs. Il se peut aussi qu’Aller les ait initiés à des conventions artistiques autochtones[16], une attention qui a pu faciliter l’expression des enfants. Cette relation entre le dessin d’enfant, l’humanitarisme et le combat pour l’intégration d’« histoires, de pratiques et de croyances localisées[17] » dans l’art moderne est un thème qui traverse les analyses du dessin humanitaire.

Si, à ma connaissance, on ne retrouve pas de dessins d’enfants dans les archives des mouvements anti-esclavagistes, ces autres ancêtres de l’aide humanitaire moderne, c’est en partie parce que les oeuvres des enfants sont souvent éphémères et que la possibilité de s’exprimer sur un support qui traverse la distance et le temps est rarement offerte aux enfants pauvres. Les artistes du milieu du 19e siècle, qui se sont intéressés les premiers aux particularités du langage pictural enfantin, avaient déjà souligné le problème, tel que le littéraire français Théophile Gautier qui parlait des « petits bonhommes dont les gamins charbonnent les murailles[18] ». En 1983, le « photographe humaniste » et délégué du Comité international de la Croix-Rouge (CICR), Jean Mohr, trouva le moyen de surmonter la précarité et l’immobilité de telles oeuvres en rapportant du camp jordanien de Jerash l’image d’un mur couvert de gribouillis, signes inamovibles du besoin d’expression d’enfants réfugiés[19].

Quinze ans auparavant, de passage à Kakya en Ouganda, il avait « pris des images » d’écoliers dansant pour les visiteurs, documents qui parlent d’une autre façon de ce que les publics d’outre-mer peuvent et ne peuvent pas voir. En regardant les jeunes artistes et leurs oeuvres que Mohr a photographiés, il est facile de voir comment les dessins des enfants produits dans un contexte humanitaire peuvent avoir un rôle ludique pour leur auteur au moment de leur production. Plusieurs pédagogues réformistes du tournant du 20e siècle ont souligné cet aspect de l’art enfantin dans des campagnes destinées à contrer la rigidité des cours de dessins de leurs contemporains. Ces tenants du « dessin libre » ne s’entendaient toutefois pas sur le rôle joué par le dessin pour les enfants : alors que certains n’y voyaient là qu’un jeu, d’autres y voyaient davantage un véritable moyen de grandir, comme l’instituteur de l’école d’Alberni.

Mohr se rappelle que la Croix-Rouge l’avait choisi comme envoyé en raison de la « douceur » de son approche qui privilégiait des témoignages auxquels « les gens pouvaient s’identifier ». Soucieux de ne pas montrer ses sujets « dans des conditions de faiblesse qui les auraient blessés », il voyait dans les rires et les jeux que les enfants inventaient à partir de « presque rien » un espoir qui aiderait ses images à provoquer l’action et l’intervention. L’an dernier, à l’occasion du 150e anniversaire du CICR, l’exposition itinérante des clichés de Mohr, qui a fait son chemin jusqu’à Ottawa, leur a donné une vie nouvelle. Par leur entremise, les messages des jeunes de Kakya et de Jerash ont pu traverser le temps et la distance, comme il l’avait souhaité : « Je reste extrêmement sensible à l’évolution de ce qui se passe. Si mes images pouvaient être valables encore pour d’autres combats, j’en serais fort content[20] ». Cet aspect positif des messages transmis par les enfants est une question d’importance pour l’histoire de l’humanitaire. Les thèmes des peintures d’Alberni montrées dans les médias, par exemple, ne semblent pas avoir directement rendu compte de la douleur de l’enfermement. Le bonheur des sujets n’est pas seulement le fruit d’une sélection adulte, mais il peut être celui des enfants eux-mêmes. Les psychologues, sensibles à la multiplicité des formes de renseignements que peut contenir un dessin d’enfant, ont étudié les cas de jeunes conscients de l’incertitude de leur avenir qui choisirent de ne représenter que le meilleur d’eux-mêmes dans des tableaux qu’ils pourraient être fiers de laisser derrière eux[21]. Ces exemples montrent bien que les adultes ne sont pas les seuls à influencer la conduite et la circulation des dessins d’enfants et que les jeunes, eux aussi, ont un public en tête et poursuivent un but précis[22]. Ce qui semble souvent impressionner les humanitaires qui conservent et exposent ce type de dessin, c’est la capacité des jeunes en difficulté à évoquer ce qui existe au-delà des murs, en comptant sur leurs souvenirs ou leur imagination. Ceux qui désirent rendre hommage à leur vie croient souvent qu’il n’est pas de meilleure façon de le faire que de publier ces images d’espoir, comme dans le cas des collections de reproduction posthumes des oeuvres picturales des enfants des classes clandestines du camp de concentration de Theresienstadt de l’Allemagne nazie[23]. Ce thème, en particulier, est intéressant puisqu’il va à l’encontre de la tendance discréditée qu’ont souvent les humanitaires à dépeindre les enfants comme êtres isolés pour générer la pitié des donateurs. Les peintures conservées par Robert Aller, quant à elles, ne semblent pas avoir représenté la douleur directement. Il se peut enfin que les enfants d’Alberni se soient tus comme les enfants algériens de la guerre coloniale qui, réduits au silence par la peur d’un ennemi omniprésent, participèrent à une « culture du silence » entretenue par leurs aînés[24].

La Grande Guerre et ses lendemains

Les jeunes dessinateurs associés à l’aventure humanitaire de Herbert Hoover au moment du premier conflit mondial, d’abord en Belgique puis en Europe centrale et enfin en Union Soviétique, furent souvent des enfants des classes moyennes faisant parvenir aux donateurs américains un message de gratitude, à l’instigation de leurs instituteurs. Envoyés par groupes, produits en contexte scolaire, leurs images et leurs textes se sont retrouvés à West Branch Iowa, dans la collection de la bibliothèque présidentielle, où je les ai étudiés il y a sept ans[25].

Ces dessins d’enfants belges figurent au sein de nombreux gages de remerciement transatlantiques, à côté de dentelles, de broderies et d’autres objets fabriqués par des adultes. Au moment de l’invasion allemande, les instituteurs des écoles publiques étaient reconnus pour l’emploi d’une pédagogie froebélienne, favorisant le dessin et l’aquarelle, en vue de développer l’observation et la croissance[26]. Certains parmi les jeunes auteurs écoliers semblent avoir trouvé dans ce travail effectué en milieu scolaire assez de la latitude pour assortir leur gratitude d’un message autonome. Il y a ceux qui, par exemple, accompagnaient leurs dessins d’un texte rappelant aux enfants américains qu’il était de leur devoir d’aider les enfants belges qui souffraient personnellement pour défendre des libertés dont tous les pays bénéficieraient. Il y a aussi ceux qui remerciaient les bienfaiteurs américains, non pas à titre de récipiendaires, mais comme donateurs sur un pied d’égalité puisqu’ils allaient distribuer à leur tour les offrandes d’outre-atlantique aux pauvres de leurs quartiers. Volontés d’engagement dans la vie publique et expressions de sympathies politiques, ces messages dénotaient une agentivité politique dont les conséquences sont aussi d’intérêt pour l’historien de l’humanitaire[27]. En faisant usage de l’art pictural comme moyen d’échange entre enfants de pays — et souvent de langues — différents, la Commission pour l’aide à la Belgique rejoignait les mouvements internationaux de jeunes au tournant du siècle dernier qui encourageaient les programmes de correspondance internationale, de la Croix-Rouge aux scouts et guides, en passant par le YMCA[28]. En ce début de siècle, la reconnaissance du rôle politique des enfants ressemblait souvent au projet pédagogique que la Déclaration des droits des enfants allait codifier en 1924 dans son cinquième et dernier article : « L’enfant doit être élevé dans le sentiment que ses meilleures qualités devront être mises au service de ses frères[29] ».

Dessinées assez loin du conflit, les oeuvres belges permettent aussi de réfléchir au sens de la distance et de ses conséquences. Pierre de Panafieu a préparé un livre et une exposition virtuelle au sujet d’une collection de dessins d’écoliers alsaciens de 1916 produits à la demande d’un professeur qui avait invité ses élèves à illustrer le conflit. Les juxtapositions minutieuses de Panafieu avec des dessins de presse et des cartes postales auxquels les enfants avaient accès aident à comprendre sur quels renseignements les enfants ont pu baser leurs représentations du conflit. Ce que montrent les feuilles dessinées au cours de la guerre, écrit-il, c’est que les enfants portaient « une grande attention à une actualité très récente[30] ». Ils montrent aussi que, pour reprendre les mots de La Ferrière, « children are actively responding to and negotiating cultural symbols most relevant to their environment[31] ». Les études des représentations enfantines des attaques du World Trade Centre de 2001 ajoutent une clef pour la compréhension de cette question de la proximité : les jeunes témoins de la violence dépeindraient des scènes moins horribles que ceux qui ne comptent que sur leur imagination et sur des récits de seconde main[32].

Interrogé des décennies après la Grande Guerre, l’un des enfants de l’École alsacienne confirme que la violence représentait sa propre expression plutôt que celle de ses instituteurs :

Tout cela se passait du temps de la Première Guerre mondiale, entre ma douzième et ma treizième année. Il régnait bien entendu alors, à l’École alsacienne, un vif patriotisme en accord avec son nom. Dans nos dessins d’enfants, sous la houlette de l’excellent et charmant Maurice Testard, [leur professeur] nous rivalisions de brocards sanglants contre le kaiser et ses soldats à casques à pointe. Mais c’était entièrement de notre cru; car je n’ai pas souvenir que nos professeurs, s’ils exaltaient en nous l’amour de la patrie, nous aient jamais enseigné la haine ni la vengeance, je ne les ai jamais entendus se laisser entraîner, contre l’ennemi, aux excès de langage ni aux basses injures[33].

Panafieu attire l’attention sur des thèmes récurrents que l’on retrouve dans les archives de la Commission d’aide à la Belgique dirigée par Herbert Hoover : le souci du détail dans la représentation des armes, la reprise des symboles patriotiques et la copie d’une propagande raciste. Ainsi, en est-il, selon Panafieu, des mots suivants, peints sur une aquarelle anonyme où figurent des troupes coloniales, qui transmettent « le lieu commun raciste de l’anthropophagie des Africains » : « Turco : Moi après la guerre amener vo dans mon pays car moi aimer beaucoup les boches... rôtis à la broche ! ». Exclusions, tueries, humiliations : la tendance sombre de l’expression enfantine divisait les critiques d’art du début du siècle, contemporains de l’instituteur alsacien, autant que les psychologues, les philosophes et les artistes. D’un côté, il y a avait ceux qui, comme Picasso et plus tard Georges Bataille, considéraient la destruction comme partie prenante du développement humain, allant jusqu’à voir le barbouillage juvénile comme un signe « exemplaire » de l’envie d’anéantir. De l’autre, se trouvaient les tenants d’un « optimisme pédagogique » qui recommandait aux parents et aux pédagogues de décourager cette violence. En 1930, pour représenter cet « autre dessin d’enfant », George Bataille choisit des illustrations de gribouillis d’enfants abyssins, vraisemblablement rapportés par des amis ethnologues et voyageurs[34].

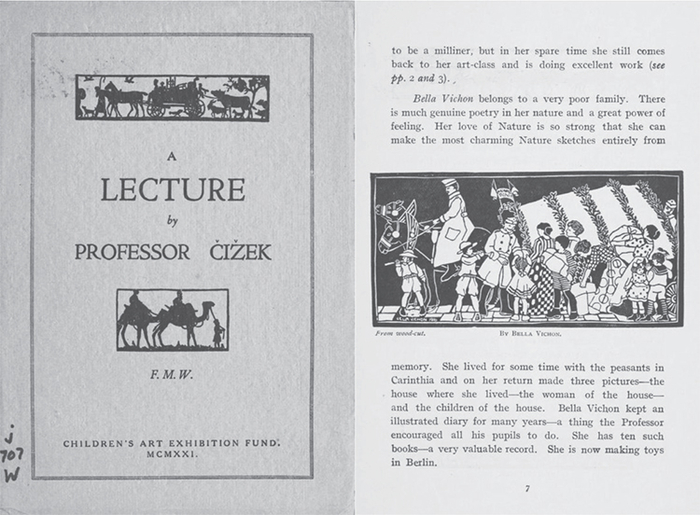

Retournons aux humanitaires. Dès les premières heures de ses projets de reconstruction en Europe centrale auprès des enfants des anciens ennemis en 1919, « Save the Children Fund » (SCF) impliqua des pédagogues convaincus de l’utilité du dessin. Pour les idéalistes du SCF, l’expression artistique des enfants de Vienne, aidés par les Quakers, représentait un moyen d’établir l’humanité des ennemis d’hier[35]. Détaché à Vienne par le SCF, Bertram Hawker, pasteur anglican, promoteur des méthodes de Montessori et partisan des idées des réformistes britanniques des « Arts and Crafts », s’intéressa à un artiste du mouvement de l’Art nouveau et collègue de Gustav Klimt, Franz Cizek. Cizek, qui enseignait l’art aux jeunes à l’école des arts et métiers de la ville depuis 1897, partagea l’engouement de Hawker pour les idées pédagogiques de William Morris. Ses méthodes privilégiaient l’expression libre des jeunes auteurs[36]. Hawker « believed that if he could get an exhibition of the work of his children touring round England, he could kill two birds with on stone – raise funds for Vienna, and revolutionise art teaching in Great Britain[37] ». Hawker confia la préparation de l’exposition à sa compatriote Francesca Wilson, une pionnière du travail humanitaire déjà installée à Vienne pour aider les Quakers. En 1921, elle présenta à Londres une exposition des dessins produits par des élèves de 10 à 15 ans de Cizek, tout en s’occupant de produire des cartes postales et des brochures pour accompagner les dessins.

L’exposition de 1921 représente un moment fort dans l’histoire de la présentation des dessins d’enfants dans des galeries d’art, débutée au Royaume Uni au siècle précédent. Le catalogue, The Child as Artist : Some Conversations with Professor Cizek, entrelaçait le texte de Wilson avec des reproductions de gravures sur bois. L’ambition pédagogique de Hawker fut réalisée quand, au cours de la décennie suivante, les autorités scolaires de Londres reprirent à leur compte ces méthodes nouvelles qu’ils appliquèrent à l’ensemble du système d’écoles publiques. L’exposition du SCF voyagea à Glasgow et Dublin, puis dans plus de 40 villes, accompagnée de collectes et de distribution de renseignements au sujet de la situation des viennois, pour ensuite partir aux États-Unis où elle allait demeurer pendant cinq ans : c’est sous son égide que les méthodes de Cizek firent leur entrée aux États Unis et au Canada[38].

The Child as Artist attira aussi l’attention sur la sophistication des jeunes artistes de même que la valeur esthétique de l’art enfantin. Cette attitude continue d’animer plusieurs de leurs usages aujourd’hui, qu’il s’agisse de leur préservation dans un établissement artistique du nord de l’Angleterre (les dessins font maintenant partie d’un fonds d’archives du Yorkshire Sculpture Park) ou de leur reproduction dans les écrits de mes collègues. Ainsi, la circulation d’images enfantines reliées aux travaux humanitaires de reconstruction et de levée de fonds fut, et demeure, essentielle dans l’élaboration et la diffusion d’une idée du dessin d’enfant comme expression artistique digne d’attention. Franz Cizek participait à un mouvement que l’historien de l’art Emmanuel Pernoud appelle l’ « invention du dessin d’enfant » dans son ouvrage du même nom. À Wilson, Cizek confia que « After fifteen, children as a rule lose their spontaneity and become ordinary. Until then their ideas grow like wildflowers in a wood — naïve, untrained, gaily coloured… » Et Wilson d’ajouter « So many children, he implied, are not allowed to have a proper Spring[39] ». Considérer le dessin d’enfant comme expression originale rejoignait l’idée forte des humanitaires du SCF selon laquelle il était important de protéger l’enfance comme période particulière, originale et cruciale, digne d’une attention dépassant les frontières et les hostilités des adultes. C’est cet esprit qui allait les mener à rédiger la Déclaration des droits de l’enfant de 1924, reconnaissant aux jeunes une volonté propre, digne d’être entendue et protégée par une institution internationale[40].

Le second pari de Hawker fut gagné : il renvoya aux Quakers travaillant à Vienne les recettes de l’exposition pour des projets parrainés par le SCF[41]. Les productions artistiques des jeunes récipiendaires de l’aide internationale allaient aussi parsemer les pages de The World Children, la publication mensuelle du SCF. Aux yeux des donateurs actuels et potentiels du SCF, les dessins représentaient une fenêtre sur la vie d’enfants que leurs offrandes permettaient d’aider, comme ceux des enfants belges envoyées aux États-Unis. Pour le bonheur des collectes de fonds humanitaires, la notion de l’expression enfantine comme reproduction de la réalité dénuée d’artifice permit d’interpeler des donateurs lointains. Il semble que plusieurs trouvèrent satisfaction à ressentir l’expérience des récipiendaires de leurs dons, sans intermédiaire apparent. Cette prédilection des philanthropes, grands et petits, jeunes et vieux, pour la valeur documentaire et émotive des témoignages enfantins a été analysée par l’anthropologue Erica Bornstein dans une étude conduite il y a une décennie à propos des donateurs canadiens du programme de parrainage des enfants au Zimbabwe dirigé par Plan Canada[42]. La notion de la neutralité du regard d’enfants innocents renforçait celle de la neutralité des humanitaires, cruciale pour les levées de fonds.

Comme le photographe Jean Mohr et l’instituteur Robert Aller, Francesca Wilson trouva du réconfort dans la joie des dessins d’enfants au moment où son travail sur le terrain était empli de souffrance. Dans ses mémoires publiés un quart de siècle après son séjour à Vienne, la travailleuse associée au SCF écrivit à des élèves de l’atelier de Cizek que « This contact with youth gave a special glow to my Vienna days — so that even now when I think of them, it isn’t starvation and relief work that come into my mind, but the laughter and gaiety of gifted children[43] ».

Venues d’Europe centrale et exécutées dans des médias du lieu et du moment, ces images, qui témoignaient de traditions graphiques culturelles particulières, furent pourtant employées par les humanitaires comme un idiome universel. Cizek n’attirait pour ses leçons gratuites offertes en fin de semaine que les jeunes intéressés qu’il encadrait au moyen de discussions, d’encouragements et d’une éducation esthétique ancrée dans une culture particulière. Paradoxalement, sa méthode demandait qu’un travail d’éducation plastique et des restrictions thématiques et formelles accompagnent ses élèves pour que leurs oeuvres conservent les qualités rythmiques et chromatiques qu’il associait aux enfants. Ces prérequis limitaient l’idéal d’universalité. Dans une tout autre perspective, l’anthropologue Margaret Mead, contemporaine de Wilson et de Cizek, allait proposer des restrictions semblables aux idées de la pureté et de l’immédiateté de l’expression enfantine. De ses voyages en Nouvelle-Guinée au tournant des années 1930, elle conclut que les enfants laissés entre eux, loin des adultes, tendaient à plus de réalisme. Elle observa aussi que les enfants élevés dans une culture pénétrée par le surnaturel ne montraient pas le même penchant pour le dessin d’imagination créatrice que les jeunes artistes du Nord[44]. Plus mornes et prosaïques que les pièces de la collection de Cizek, les 35 000 productions artistiques enfantines que Mead rapporta aux États-Unis font aujourd’hui partie de la collection de la Library of Congress. En leur temps, les dessins de Manus n’eurent pas de popularité comparable à celle des oeuvres viennoises.

Une fois la paix revenue, les humanitaires de l’Union internationale de secours aux enfants (UISE), qui regroupait les nombreux chapitres nationaux du SCF, avaient redirigé leurs énergies vers la promotion de droits universels pour les enfants. En 1927, trois ans après l’adoption de la Déclaration des droits des enfants par la Société des Nations, ils lancèrent un concours mondial de dessins par l’entremise des comités nationaux en collaboration avec le Bureau international de l’éducation. Il s’agissait d’illustrer le sens que les nouvelles prérogatives internationales auraient aux yeux de leurs récipiendaires. L’appel fut le fait de réformistes soucieux de « populariser et diffuser » le contenu de la Déclaration pour s’assurer que les enfants eux-mêmes aient conscience de leurs nouvelles prérogatives[45]. L’UISE reçut des dessins de 12 pays au terme de concours nationaux à l’envergure disparate. Par exemple, 24 000 enfants mexicains et 57 000 français y participèrent. Un jury composé de deux éducateurs, d’un promoteur des beaux-arts, d’un pédagogue et du vice-président de l’UISE décerna des médailles aux meilleurs des dessins sélectionnés par les comités nationaux, organisa une exposition des oeuvres reçues à Genève et choisit d’en reproduire quelques-unes pour illustrer son ouvrage The Declaration of Geneva and the Child[46] qui présenterait la nouvelle entente internationale du point de vue des détenteurs des nouveaux droits des enfants. La collection de 1 500 feuilles fut vite démantelée quand l’UISE renvoya la plupart des dessins aux organismes participants pour qu’ils puissent les exposer eux-mêmes. Le grand pédagogue Janusz Korczak, connu comme l’un des pères des droits de l’enfance, fit partie du Comité polonais de la protection de l’enfant qui organisa le concours dans son pays et publia dans son sillage une brochure sur La Déclaration des Droits de l’enfant dans la créativité infantile, elle aussi parsemée de dessins du concours[47]. En leur temps, il semble que ces dessins eurent surtout valeur d’enseignement et de représentation. Les quelques oeuvres encore disponibles aux chercheurs semblent appartenir pour la plupart aux traditions d’« optimisme pédagogique » de Cizek. À Carleton University où j’enseigne, les archives du Centre Landon-Pearson sur les droits des enfants contiennent un ouvrage similaire, publié cinquante ans plus tard, qui présente les dessins de jeunes canadiens appelés par le collectif «All About Us/Nous autres, Inc. » à illustrer les articles de la Déclaration universelle des droits de l’homme de 1948, trente ans après son adoption[48]. En inscrivant au nombre des droits des enfants le droit à l’expression artistique, la Convention internationale de 1989 (article 31) a renforcé cette relation entre dessin et travail humanitaire[49]. Aujourd’hui, des travailleurs sociaux et des anthropologue d’Afrique du Sud, comme Jenny Doubt, utilisent les dessins d’enfants comme moyen alternatif de répondre à la demande croissante des gouvernements et des organisations non gouvernementales pour des évaluations précises des impacts de leurs dons[50].

La guerre d’Espagne

La reprise des hostilités en Europe au moment de la guerre civile en Espagne fut l’occasion pour les humanitaires d’utiliser le dessin comme un des outils de leur travail de sauvegarde et de réhabilitation. Pionniers de ce travail, les époux Françoise et Alfred Brauner, pacifistes et sympathisants républicains, respectivement médecin et pédagogue, collectionnèrent et répandirent des milliers de dessins à partir de l’Espagne en guerre[51]. Les oeuvres furent récoltées d’abord dans des refuges républicains pour enfants évacués des régions victimes des bombardements de civils et tenus par des membres des brigades républicaines au repos ou blessés. Dans ces cas-ci, le dessin pouvait servir de moyen d’entamer une conversation : c’est ainsi que les dessins d’enfants soignés par les Brauner évoluèrent du gribouillis noir aux représentations plus différenciées, à mesure que ces jeunes victimes sortaient du mutisme causé par leur expérience de la guerre. Dessiner pouvait ainsi aider les enfants à faire face à ce qui leur était arrivé. Dans la foulée des psychologues et des philosophes « inventeurs du dessin d’enfant », les Brauner considéraient le dessin final comme un effort d’agencement du monde, le résultat d’une recherche de signification. Dans leur travail thérapeutique, ils découvrirent que l’une des seules façons d’aider les enfants les plus affligés par la guerre à sortir de leur mutisme était de les convaincre de l’existence d’un lieu sûr, chez eux, où il y aurait de l’espoir et où ils seraient attendus. L’action des adultes opérant les refuges indique à quel point le travail psychologique de réhabilitation était forcément politique. À l’exemple des dessinateurs observés par Robert Cole, l’activité des Brauner ouvrait une fenêtre sur une compréhension enfantine de la vie publique plus riche et ouverte que celle que détenaient les auteurs de la Déclaration des droits des enfants de 1924.

Alfred Brauner avait reçu du Commissaire de guerre le mandat d’écrire un livre qui témoignerait de l’action des brigades auprès des enfants réfugiés, en compagnie de leur photographe officiel. Impressionné par leurs dessins, Brauner décida de travailler lui-même auprès des enfants. Il lança aussi un programme de dessin pour toutes les écoles catalanes sur trois thèmes : « ma vie avant la guerre; comment je vois la guerre; ma vie après la guerre » qui lui permit de recueillir plus de dix mille dessins[52]. Plusieurs furent envoyés vers le reste de l’Europe et vers l’Amérique par des organisations humanitaires soucieuses de susciter des appuis matériels et moraux aus réfugiés républicains. Le plus célèbre de ces efforts de diffusion des dessins espagnols est le petit livre intitulé They Still Draw Pictures! conçu par l’écrivain et philosophe pacifiste Aldous Huxley à l’attention des Quakers américains en charge de la Spanish Child Welfare Association of America, créée pour lever des fonds afin de sauver des vies enfantines. L’auteur y offre un commentaire sur le contenu de ces dessins. Comme Cizek, Huxley avance que l’usage que font les enfants des couleurs et des formes quand ils sont laissés à eux-mêmes en font des artistes jusqu’à l’adolescence. Il s’émerveille encore de leur abilité à percevoir et à transmettre les scènes de guerre et les scènes de paix de façon sensible, dramatique, englobante et simultanée. De plus, écrit-il, pour le grand public comme pour le sociologue et l’historien, les portraits d’avions meurtriers témoignent « of the world collective crime and madness[53] ». Ces envois ont laissé des traces dans les archives canadiennes, comme celle du communiste canadien Albert MacLeod, fondateur du Canadian Committee to Aid Spanish Democracy[54]. On comprend comment ces représentations de la guerre par l’entremise du regard enfantin, en imbriquant innocence et horreur, ont eu un pouvoir de choc répondant aux buts des époux dont le travail était relié à des convictions pacifistes. Vue de cette façon, la popularité de ces dessins auprès du public humanitaire peut avoir une dimension plus intéressante que le simple voyeurisme, mentionné en introduction, qui troublait le Groupe McLeod. Elle permettrait la transmission d’un message relativement autonome de la part d’enfants en difficulté vers des publics eux aussi à la recherche d’une compréhension de la nature des conflits.

Le travail d’archivage et de conservation de ces dessins donne l’occasion de réfléchir à la conservation de ces sources documentaires. Comme les Premières Nations de l’Île de Vancouver, plusieurs associations espagnoles conservent avec fierté ces documents du passé. À la suite de la Guerre d’Espagne, les Brauner eux-mêmes se sont fait collectionneurs de dessins de guerre venus de partout : les pièces qui font l’objet de leur publication intitulée J’ai dessiné la guerre, remontent à la Guerre des Boers. Cette collection a récemment fait l’objet d’une mise en ligne ainsi que d’une entreprise analytique profonde et novatrice. L’équipe de Enfants-Violence-Exil étudie « les regards portés sur l’enfance en guerre ». Elle travaille entre autres sur les questions d’interprétation de ces dessins. Une série d’entrevues d’Alfred Brauner offrant ses commentaires à mesure qu’il regarde des dessins accompagne la collection : on y voit comment le couple observait déjà l’ordre dans lequel un enfant dessinait, y compris sa gestuelle, dans un effort de compréhension des petits réfugiés[55]. De tels renseignements recueillis sur le champs sont précieux pour l’analyse. Au cours de la Seconde Guerre mondiale, les Brauner ont poursuivi leur travail en France auprès de jeunes réfugiés d’Allemagne et d’Autriche. Lorsque vint le temps d’exposer les dessins de leurs pupilles, ils ne choisirent que ceux qui dépeignaient le conflit. Pourtant, comme l’écrit l’une des membres du collectif EVE, les représentations de scènes domestiques doivent être étudiées elles aussi, bien que d’une autre façon, comme les dessins de guerre[56]. Il est intéressant aussi de savoir que les Brauner devinrent plus tard spécialistes du traitement de l’autisme et qu’une entreprise amorcée à l’occasion d’une urgence humanitaire eut de si grandes répercussions en temps de paix.

Les guerres de libération coloniale

Les dessins des enfants des guerres de libération coloniales ont été utilisés comme moyen curatif par le psychiatre, combattant et théoricien de l’anticolonialisme, le Martiniquais Frantz Fanon, d’une façon qui n’est pas sans rappeler celle des Brauner. Des oeuvres réalisées par de jeunes réfugiés algériens, orphelins ou non accompagnés, hébergés par les maisons d’enfants de Tunisie tenues par le Gouvernement provisoire de la République algérienne, furent ramenées en France par le réalisateur anticolonial français René Vautier. Deux collègues les mirent en mouvement et utilisèrent des récits d’enfants comme bande sonore[57]. Le petit film « J’ai huit ans[58] » « marked a critical intersection between radical psychiatry and activist cinema ». Les violences apparaissent à travers des témoignages graphiques et oraux, comme dans les cas présentés par les Brauner. Le pari de Fanon était thérapeutique : la « visualisation » de ce qui les troublait, par l’entremise de la parole, de l’écrit ou du dessin, pourrait aider les réfugiés, adultes et enfants, à faire face à leurs expériences. De tels cinéastes, comme le philanthrope italien Giovanni Pirelli qui publia des douzaines de ces dessins, misaient sur la force accusatrice du regard enfantin dont le « potentiel dramatique » provoquerait l’indignation : garçons et filles y étalaient en effet une connaissance incontournable de la torture et des actes d’humiliation gratuits auprès des civils, que plusieurs refusaient de reconnaître en France métropolitaine[59]. Le film incorporait une photo de jeunes regardant directement la caméra et, pour le bénéfice de l’auditoire métropolitain, l’idiome de leurs propos était le français, leur langue seconde. Dans ce corpus, comme dans les témoignages dessinés des enfants évacués de l’Espagne des années 1930, la profondeur de l’engagement politique des enfants apparaît loin de l’idéal d’innocence associé au jeune âge par un humanitarisme simpliste. Le film, selon l’analyste Nicholas Mirzoeff, représente enfin un acte de mémoire et de commémoration de la guerre dans les régions rurales et une preuve du succès de la résistance anticoloniale. La police française reconnut tôt cette fonction de la pellicule; le film fut ainsi saisi et banni des écrans du pays jusqu’en 1973, bien qu’il se mérita plusieurs prix lorsqu’il put être projeté.

Comme dans le cas des auteurs de son parent écrit, Les enfants d’Algérie, les réalisateurs du film cèdent le pas aux voix et aux images enfantines. Cette anonymité de l’équipe de production met l’accent sur l’expression orale et picturale et « reinforc[es] the impression of direct testimonial connection between reader and child, as well as integrating the children’s collective testimony into the collective voice of the FLN[60] ». Comme les dessins recueillis par Save the Children à Vienne, ceux des maisons d’enfants furent présentés en tant que témoignages universels représentant tous les enfants algériens. Dans les deux cas, il s’agissait d’une sélection, l’une basée sur les préférences artistiques des enfants, l’autre sur leur proximité, les 3000 pensionnaires des maisons d’enfants urbaines de Tunisie étant plus accessibles que les 14 000 enfants des camps de réfugiés des zones frontalières.

Épilogue et conclusion

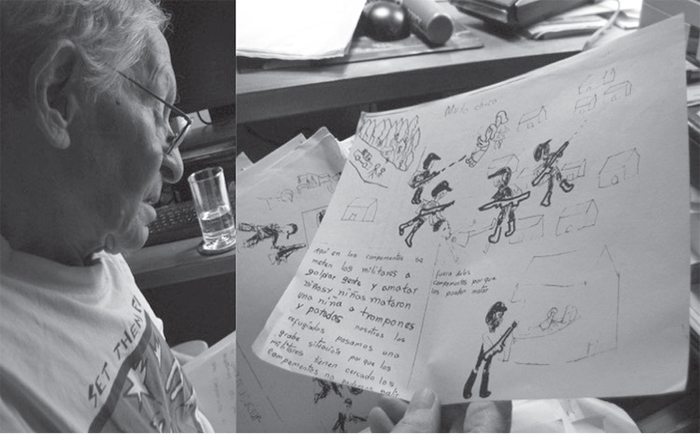

C’est une rencontre avec Meyer Brownstone, Directeur d’Oxfam Canada à partir de 1975, qui m’a poussée à rassembler des dessins d’enfants récoltés au fil de recherches disparates. Les dessins et les artéfacts qu’il a rapportés des camps de Salvadoriens réfugiés au Honduras dans les années 1980 représentent en partie des mémentos[61]. L’un des premier documents qu’il m’a montrés fut dessiné par un enfant avec qui il s’était lié d’amitié. La légende, vraisemblablement écrite par le garçon, indique :

Martha « chica » [fille] (« Martha chica » pourrait aussi vouloir dire tuez la fille) — Ici dans les camps (?) les militaires entrent (...) nous ne pouvons sortir du camp parce qu’ils peuvent nous tuer (...) — ils ont tué une fille en lui donnant des coups de poing et de pied - nous les réfugiés avons de la difficulté parce que les militaires entourent le camp et nous ne pouvons sortir en dehors du camp parce qu’ils peuvent être tués[62].

Brownstone ne retrouva plus l’enfant, lors de son voyage subséquent, et il craint qu’il ait été tué. Au cours des mêmes années, des Français associés aux Brauner et fondateurs d’Enfants Réfugiés du Monde se rendirent dans des camps du Chiapas qui accueillaient des réfugiés guatémaltèques, victimes d’une autre guerre civile, pour travailler auprès de leurs enfants. Ils rapportèrent eux aussi de leurs expéditions des dessins d’enfants. Aujourd’hui, leur propre travail de recherche inclut une série d’entrevues fascinantes menées avec les auteurs des dessins d’il y a trente ans qu’ils ont pu retrouver et qui se rappellent, comme les survivants du pensionnat d’Alberni, des circonstances dans lesquelles ils ont créé leurs oeuvres[63].

Au Honduras, comme dans les refuges espagnols des années 1930, les productions artistiques des camps relevaient en partie du besoin d’occuper les enfants et de les scolariser au plus tôt malgré des circonstances précaires, un travail constructif et de longue haleine qui correspondait aux principes d’Oxfam Canada. Pour les humanitaires, comme le photographe Jean Mohr et le travailleur humanitaire Meyer Brownstone, il ne s’agissait pas seulement de représenter l’espoir, mais encore de montrer que ces communautés avaient la capacité de s’aider elles-mêmes. D’autres dessins prirent la route d’une exposition organisée par des enseignants canadiens, dont le catalogue figure dans la collection de Brownstone. Plus optimistes et moins choquants, ces dessins participaient d’un effort de solidarité internationale entre travailleurs de mêmes occupations, ce que Oxfam entreprenait au même moment avec les pêcheurs, les infirmières ou les agriculteurs. On eut aussi replacer ces circulations de dessins d’enfants au sein d’une panoplie de moyens de mobilisation — comme les chansons de Bruce Cockburn — aptes à communiquer directement par les sens des réalités urgentes auprès des Canadiens dont Oxfam recherchait les appuis.

Les images rapportées par Brownstone sont maintenant prisées par des membres de la diaspora salvadorienne au Canada qui utilisent ces archives pour comprendre leur passé[64]. D’autres diasporas canadiennes qui fournissent souvent l’armature des relations humanitaires ont utililisé les dessins d’enfants. C’est le cas d’un petit livre sur les enfants du Sierra Leone en guerre, présentant des oeuvres de la fin des années 1990, écrit par un enseignant canadien d’origine sierra léonaise grâce à son engagement de longue date au sein de la communauté des enseignants africains[65]. De la centaine de dessins ramenés au Canada, la douzaine d’oeuvres choisies pour publication contient le dessin d’un viol, avec une intention de choquer semblable à celle d’Huxley et ou encore des auteurs du film sur la Guerre d’Algérie. En 2014, pour parler de viol en temps de guerre, les auteurs du petit vidéo présenté pour annoncer le sommet de Londres sur la violence sexuelle dans les régions de conflit ont choisi le langage du faux dessin d’enfants[66]. Il est vrai que souvent des adultes des mêmes régions n’ayant pas eu la chance de dessiner depuis leur jeune âge peuvent dessiner comme des enfants[67].

Le dessin cher à Brownstone et les collections archivées par les collègues de Landon Pearson dans le Centre du même nom attendent encore qu’on les analyse. En somme, appréhendés à l’aide des cas examinés ici, rescapés des pires situations, les dessins auraient de multiples rôles à jouer pour l’histoire de l’expression enfantine et celle de l’humanitaire. Au moment de leur production, ils procurent des avenues de protection, de compréhension du monde, de jeu, d’expression ou de valorisation, de participation à la vie publique et d’échange transnational aux enfants affligés ou en situation de profonde inégalité. Une fois présentés à un public humanitaire, ils offrent des possibilités de communication, de reconnaissance et de réparation des injustices. Réappropriés par leurs communautés d’origine en contexte postcolonial, ils constituent des ponts mémoriels et des renforcements culturels. Enfin, comme formes d’expression artistique, ils présentent aux critiques un matériau de réflexion sur les aspects négligés et les frontières de l’art moderne. J’espère que ce voyage à travers un corpus de dessins produits dans des contextes humanitaires vous permettra de prendre le temps de regarder avec intérêt la prochaine livraison du genre et que ces documents ont acquis une signification un peu plus éloquente, au-delà du cynisme, de l’horreur ou de l’émerveillement.

Introduction

In the history of humanitarian aid, children’s drawings are omnipresent, for better or for worse. The worse is a “pornography of poverty,” a simplistic and paternalistic industry of pity, which speaks only about the symptoms of inequalities and of solutions, instead of causes. In this context, the mobilization of actions and works by children may represent some of the most simplistic methods of fundraising for help between nations. The better is a communication between givers and receivers of aid, independent and thoughtful on each side.[1] In these circumstances, children’s expression plays another role to unlock opportunities and remove stereotypes. This overview of the multiple and contradictory roles of children’s pictorial expression in humanitarian history also shows that international aid is an integral part of the history of drawing, as is the case for its more extensively studied relative, humanitarian photography. Moreover, children’s drawings produced or used during humanitarian experiences have played an active part in the development of many types of expertise, from psychology to pedagogy, including philosophy, art history, anthropology, and plastic arts. My study borrows from this knowledge and presents rare practitioners in each discipline who have analysed the genre of humanitarian children’s artwork in itself.

This effort to place children’s drawings into context and study their meanings for the history of international aid, is relatively new. As a starting point, I focus on the drawings encountered in my research on the history of children’s rights and the history of non-governmental organizations (NGOs). I touch on the following aspects: the identity of the artists and the variety of roles that the drawings may have played in their own lives; the contexts, actors, conditions of production, and collection of the drawings; the audiences anticipated and not anticipated by the various artists; themes, styles, selection modalities, circulation chains, exhibition, publication, and archiving histories; the nature of contemporary and posterior receptions; problems of ethical and intellectual property related to the drawings’ use; the question of the existence of aspects specific to these types of drawings; and their interpretations as a source of historical work.

Drawings from Religious Missions

If we think of missionaries as the first humanitarians, among the oldest drawings by young wards of which I am aware are those painted by Wu Lan, one of the first Chinese in the United States, who arrived in New England in 1823 to study at the Cornwall Foreign Mission School. With a view to raising money, the mission school used exhibits of children’s performances and works. Childhood historian Sanchez-Kepler uncovered 19 watercolours accompanied by English and Cantonese texts attributed to a 19-year-old man, as many contributions to a collective “friendship album” for a beloved teacher.[2] The tools of English and postcolonial literature help her identify pieces of personal expression among the exercises of recopying that the preparation of such albums involved, despite the ponderousness of educational and national codes. The attentive juxtaposition by Wu Lan of two language and pictorial idioms provides keys to understanding the friendships and concerns of a young man making sense of the collision of the two worlds in which he evolved.

The history of colonial education tells us that the space of relative freedom necessary for children’s expression was rarely given to non-European pupils of Christian missions. Still, the works of Wu Lan show that the act of painting or writing “open[ed] to other possibilities of expression and gestures toward other possible relations.”[3] According to sociologist and education historian de La Ferrière, this very opening represents “the source of the rhetorical and emotional power conveyed by these documents.”[4] Thus, the active nature of the childhood drawings would call out to humanitarian audiences for reasons that are different from the appeal of the passive representations of poor children, more typical of humanitarian campaigns. However, de La Ferrière does not presume the truth of this expression: what counts, he writes, is that “We hear (or we think we hear) the children’s own voices.”[5] We will return to this point.

One hundred and fifty years later, children’s drawings from the Alberni Indian Residential School in British Columbia, recently exhibited at the Canadian Museum of History as part of the end of the work of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (2008-2015),[6] also represent a collection of children’s expressions rescued from missionary history. In this case, however, the collection involves long-hidden works, with a deferred emotional charge. The Commission had always assumed that the art of adults who had survived the Indian residential schools could hold “a strong cultural and social power,” serving not only as a witness and a means of retrospective healing, but also as an opportunity for education and communication.[7] The First Nations Family and Child Caring Society of Canada had also called for artistic productions on the theme of reconciliation from today’s Canadian children and used them as the basis of the association’s logo.[8] Finally, cases were mentioned of artists, including Aboriginal artists, who had given classes in residential schools, offering students both a refuge and some recovery of their self-esteem.[9] But before the discovery of the Alberni drawings by anthropologist Andrea Walsh from the University of British Columbia, it was hard to imagine that accounts of children at the time of internment had survived the closure of residential schools. Five years ago, she realized that Robert Aller, artist and volunteer art teacher in the early 1960s,[10] had kept 47 paintings done by children at the residential school of Vancouver Island. After this finding, Walsh started to look for the artists and their descendants.[11]

Local journalist Judith Lavoie gathered the comments of one of the artists, now Hereditary Chef of the Ahousaht First Nation on Vancouver Island. His account shows that, more than the act of drawing, the protection that the teacher of the art class offered, removed as it was from the sexual violence of the dormitory, appears to have motivated the students:

[Maquinna Lewis] George … was sent to Alberni Indian Residential School when he was about six years old. Soon after his arrival, he jumped at the chance of taking art classes because they would get him out of early bedtime: “They used to put us to bed at 6 p.m. and the art classes were between 7 p.m. and 10 p.m.,” he recalled. It was during the evening that most sexual abuse happened — dorm supervisor Arthur Henry Plint was eventually branded a “sexual terrorist” by the courts. “I credit those classes with keeping me from being abused,” said George, who was physically abused at the school but escaped the sexual abuse that many of his friends and siblings suffered ... “I want my story kept alive,” said George, who remembers the kindness shown to him by volunteer art teacher Robert Aller as being in stark contrast to the harsh realities of life at the school.

Over time, these painted pages have taken on new meanings. Studied by the Commission, exhibited across the country, expressions of young victims, they figure amongst the traces of a scandal hidden for decades. At the Canadian Museum of History, the event of 1 June 2015 included the exhibit of works as well as “the incredible story of the repatriation of these childhood paintings as told by the Survivors themselves, and the role art has played in both truth telling and reconciliation.”[12] The exhibit creators suggested that “artworks dealing with trauma contribute to healing either the artist or the public.”[13] The question of their therapeutic value at the time of their production is less well known than their curative value today, and we can hope along with the experts of trauma that they will become objects of cultural studies.[14] After their rediscovery, some of the Alberni paintings returned to the artists, while others were archived. The ethics of their ownership also has a story: two years ago, they became objects of a repatriation ceremony, during which the descendants of the child painters carried the artwork in front of them, as tokens of transmission of memory and possibly a symbol of “cultural vitality.”[15]

The Alberni paintings, as the Ahousaht Chief recalled in his interview with the Times Colonist, also attest to the generosity of a white teacher who, in addition to encouraging the production of the works, recognized the importance of preserving them. Robert Aller did ask each of his students to leave him one painting. Aller taught art in prisons and at the YMCA, and championed Aboriginal art. His work with children, “whose curiosity and spontaneity met his own” and to whom he preferred to give materials to “let them discover their own mode of expression,” represented the most joyful part of his career. Under his tutelage, children who were otherwise punished at the mention of their original culture had a unique opportunity to “remember where they came from …,” by painting scenes from their memories and perhaps receiving from Aller the rudiments of Aboriginal artistic traditions.[16] This attention to the pictorial conventions of their own culture might have facilitated the children’s expression. The story of Alberni’s drawings shows a relationship between children’s artwork, philanthropy, and the struggle, in modern art, for the integration of “local stories, practices and beliefs.”[17] We will come back to this theme, present throughout analyses of humanitarian artwork.

If, to my knowledge, we do not find children’s drawings in the archives of the anti-slavery movements, these other ancestors of modern humanitarian aid, it is partly because children’s works are often ephemeral and because the possibility to express oneself through a medium that will survive distance and time declines with diminished wealth. Artists from the mid-nineteenth century who took interest in the particularities of the graphic language of children had already pointed out the transient nature of children’s media of expression. French literary figure Théophile Gautier, for instance, spoke of images of “little fellows charcoaled by lads on the walls” of cities.[18] In 1983, Jean Mohr, the “humanist photographer” and delegate of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), found a way to overcome the precariousness and immobility of the works of displaced children living in the Jordanian camp of Jerash by bringing back the image of a wall covered in scribblings, irremovable signs of free and spontaneous expressions of refugee children.[19]

Fifteen years earlier, when passing through Kakya in Uganda, Mohr had “taken images” of school children dancing for visitors, a type of communication that audiences overseas could not directly receive. Looking at the young artists and their works photographed by Mohr, one also understands how, at the time of their production, drawings could offer a form of play for their creators. At the turn of the twentieth century, many reformist educators had already highlighted this aspect of children’s art in campaigns designed to counter the rigidity of the art lessons of their contemporaries. These supporters of “free art” were in turn divided amongst those for whom the role of art stopped there, at games, and those who had seen in it a true means of growth, such as the teacher at the Alberni School.

Mohr recalls that the Red Cross had chosen to send him to tour the camps because of the “softness” of his photographs, focused on testimonies with which “the people could identify.” Concerned not to show his subjects “in the conditions of weakness that would have harmed them,” he photographed the laughing of children and the games they were inventing from “almost nothing,” to convey hope and provoke action and intervention. Last year, for the 150th anniversary of the ICRC, the travelling exhibit of Mohr’s pictures made its way to Ottawa and gave to the expressions of Jerash children a new life. Through Mohr’s work, messages of the youth from Kakya and Jerash crossed time and space, as he had wished: “I remain extremely sensitive to the evolution of what is happening. If my images could still be valuable for other struggles, I would be very happy.”[20] This positive aspect of the children’s work collected in Jordan and Kenya represents a key issue for the writing of humanitarian history. The happiness of the subjects might have been not just the product of an adult selection, but the choice of the children themselves. Similarly, child artists’ choices might explain why the Alberni paintings do not appear to have recorded directly the pain of confinement.

Indeed, psychologists, sensitive to the multiplicity of forms of information that a child’s drawing may contain, have studied the cases of youth aware of the uncertainty of their future who chose to represent only the best of themselves in artwork that they would be proud to leave behind them.[21] These examples also show that adults are not the only ones to influence the drive and circulation of children’s drawings, and that youth themselves have an audience and ends in mind.[22] What appears to impress the humanitarians who keep and exhibit this type of artwork is the ability of youth in difficulty to evoke what exists beyond the walls, using their memories or their imagination. Those who want to pay homage to children’s lives often believe that there is no better way to do so than to publish these images of hope, as in the case of posthumous collections of the pictorial works of children from clandestine classes of the Terezin Concentration Camp in Nazi Germany.[23] This theme in particular is interesting, because it runs counter to the discredited humanitarian tendency of depicting children as being isolated to generate the pity of donors. Alternatively, it is possible that the children of Alberni kept quiet, reduced to silence out of fear of an omnipresent enemy, as many participants to a “culture of silence” maintained by their seniors.[24]

The Great War and its Aftermath

The young artists associated with the humanitarian work of Herbert Hoover at the time of the World War I, first in Belgium, then in central Europe, and finally in the Soviet Union, were often children of the middle class sending American donors a message of gratitude at the instruction of their teachers. Sent in groups, produced in school settings, their images and texts are found in West Branch, Iowa, in the collection of the presidential library, where I studied them seven years ago.[25]

These drawings from Belgian children figure among many tokens of transatlantic gratitude, next to lace, embroidery and other items made by adults. At the time of the German invasion, public school teachers were known for using Froebelian pedagogy, fostering drawings and watercolours, with a view to developing observation and growth.[26] Some of the young student artists appear to have found in this work, performed in school with the predetermined goal of thanking faraway donors, enough latitude to pair their appreciation with an independent message. For example, some students’ artworks were accompanied by text reminding American children that it was their duty to help the Belgian children who were personally suffering to defend the freedoms from which all countries would benefit; others thanked the American benefactors not as recipients but as donors on equal footing, because they would in turn distribute the transatlantic offerings to the poor Belgians of their neighbourhoods. Willingness to engage in public life, expressions of political sympathies, these messages denoted a political agency of interest to the humanitarian historian.[27] By making use of pictorial art as a means for exchange between children of different countries — who often spoke different languages — the Commission for Relief in Belgium joined the international youth movements of the last century that had encouraged international Pen Pal programs, from the Red Cross to the Scouts and Guides, including the YMCA.[28] At the start of the century, the recognition of the political role of children was often synonymous with the educational project that the Declaration of the Rights of the Child would codify in 1924 in its fifth and last point: “The child must be brought up in the consciousness that his talents must be devoted to the service of his fellow men.”[29]

Created far enough away from the conflict, the Belgian works also permit reflection on the meaning of distance and its consequences. School principal Pierre de Panafieu produced a book on, and a virtual exhibition of, a collection of Alsatian drawings produced in 1916 at the request of a teacher who had invited his students to illustrate the conflict. Panafieu’s careful juxtapositions with the media, drawings or postcards to which the children had access, help identify children’s basis for representations of the conflict. What such pictures show, he writes, is that the children were paying “great attention to very recent events.”[30] They also show that “children are actively responding to and negotiating cultural symbols most relevant to their environment.”[31] Studies of childhood representations of the attacks on the World Trade Center in 2001 add an insight into the issue of proximity: young witnesses to violence seem to depict scenes less horrible than those painted by children who can only rely on their imagination or on second-hand accounts.[32]

Questioned decades after the Great War, one of the children of the École alsacienne confirmed that the violence in his drawings represented his own expression rather than that of his teachers:

All that happened at the time of the World War I, between my twelfth and thirteenth birthday. Of course, at the École alsacienne, a strong patriotism reigned as its name indicates. In our childhood drawings, under the tutelage of the wonderful and charming Maurice Testard, [their teacher] we tried to outdo each other with bloody gibes against the Kaiser and his soldiers with their spiked helmets. But it was entirely of our creation; because I have no memory that our teachers, although they extolled in us love for our country, ever taught us hate or vengeance, I never heard them get drawn into inappropriate language or mud-slinging against the enemy.[33]

Panafieu draws attention to the recurrent themes, which we find in the archives of the Commission for Relief in Belgium headed by Herbert Hoover: the concern for detail in representation of weapons, the repetition of patriotic symbols, the reproduction of racist propaganda. Thus, he writes, words painted on an anonymous watercolour in which colonial troops appear (“Turco: after the war, I’m going to bring you to my country because I really like the boches ... roasted on the spit!”) convey “the typical racist cliché of African cannibalism.” Exclusions, killings, humiliations: the dark tendency of childhood expression divided the art critics at the start of the century, contemporaries of the Alsatian teacher, as well as psychologists, philosophers, and artists. On the one hand, some, like Picasso and later Georges Bataille, regarded destruction as an integral part of human development, going so far as to consider the juvenile scribbling as an “exemplary” sign of the desire to destroy. On the other hand, the supporters of an “educational optimism” recommended that parents and educators discourage this violence. In 1930, to represent this “other childhood drawing,” George Bataille chose reproductions of Abyssinian children’s scribbling, likely brought back by ethnologist friends and travellers.[34]

Let’s return to the humanitarians. From the very start of its reconstruction projects in central Europe with children of former enemies in 1919, the “Save the Children Fund” (SCF) involved educators convinced of the usefulness of drawing. For the SCF idealists, the artistic expression of children from Vienna receiving aid from the Quakers represented a means of establishing the humanity of yesterday’s enemies.[35] Posted in Vienna by the SCF, Bertram Hawker, an Anglican pastor and promoter of the Montessori methods and partisan of the ideas of the British reformists of the “Arts and Crafts,” took interest in an artist from the Art nouveau movement and colleague of Gustav Klimt, Franz Cizek. Cizek, who taught art to youth at the town’s school of arts and crafts starting in 1897, shared Hawker’s passion for the educational ideas of William Morris. His methods fostered the free expression of young creators.[36] Hawker “believed that if he could get an exhibition of the work of his children touring round England, he could kill two birds with one stone — raise funds for Vienna and revolutionize art teaching in Great Britain.”[37] Hawker entrusted the preparation of the exhibit to his compatriot Francesca Wilson, a pioneer of humanitarian work who had arrived in Vienna earlier to help the Quakers. In 1921, she presented in London an exhibit of drawings produced by Cizek’s students between the ages of ten and 15, while looking after producing postcards and pamphlets to accompany the drawings.

The 1921 exhibit represented a key moment in the history of showing children’s artwork in art galleries, which had begun in the United Kingdom in the previous century. The catalogue, The Child as Artist: Some Conversations with Professor Cizek, entwined Wilson’s text and reproductions of wood carvings. Hawker’s educational ambition was realized when, over the course of the next decade, the academic authorities of London endorsed these new methods themselves and applied them to the entire public school system. The SCF exhibit travelled to Glasgow and Dublin and to more than 40 towns and cities, together with collection boxes and information material on the plight of Vienna. It then left for the United States and Canada, where it would remain for five years: it is under this aegis that Cizek’s methods made their entrance in North America.[38]

The Child as Artist also attracted attention to the sophistication of the young artists and the aesthetic value of children’s art. This attitude continues to drive many of the uses of the artworks today, from their preservation in an artistic institution of northern England (the drawings are now part of an archival collection of the Yorkshire Sculpture Park) to their reproductions in the writings of fellow historians of humanitarian aid. As a result, the circulation of childhood images related to humanitarian reconstruction work, fundraising, and promoting universal standards was, and remains, an integral part of the development and dissemination of the idea of children’s artwork as artistic expression worthy of attention. Franz Cizek participated in a movement that art historian Emmanuel Pernoud calls the “invention of children’s drawing,” in his book of the same name. To Wilson, Cizek confided that “after fifteen, children as a rule lose their spontaneity and become ordinary. Until then their ideas grow like wildflowers in a wood — naïve, untrained, gaily coloured …” Wilson added, “so many children, he implied, are not allowed to have a proper Spring.”[39] To consider children’s drawings as original expression aligned with the strong belief of the SCF humanitarians that it was important to protect childhood as a special, original, key time, worthy of an attention that went beyond the borders and hostilities of adults. This is the spirit that led them to draft the 1924 Declaration of the Rights of the Child, recognizing that the autonomous will of young people was worthy of understanding and protection by an international institution.[40]

Hawker’s second wager was won: he returned to the Quakers working in Vienna the proceeds from the exhibit to fund projects sponsored by the SCF.[41] The artistic productions of young recipients of international aid would also spruce up the pages of the monthly publication of the Save the Children Fund, The World’s Children. In the eyes of the current and potential donors of the Save the Children Fund, the drawings, like the art of the Belgian children sent to the United States a few years earlier, represented a window into the lives of the children that their offerings helped. For the good of humanitarian fundraising, the concept of childhood expression as a reproduction of reality free of artifice helped reach distant donors. It appears that many found satisfaction in feeling the experience of the recipients of their donations, without any clear intermediary. This predilection of philanthropists, large and small, young and old, for the documentary and emotive value of childhood testimonies was analysed by anthropologist Erica Bornstein in a study conducted a decade ago of Canadian donors participating in a program for children in Zimbabwe led by Plan Canada.[42] The notion of the impartial eye of innocent children free from the responsibilities of their seniors strengthened the perception of the impartiality of humanitarians, crucial for fundraising.

Like photographer Jean Mohr and teacher Robert Aller, Francesca Wilson found comfort in the joy of the children’s drawings at a time when her work in the field was filled with suffering. In her memoirs, published a quarter of a century after her time in Vienna, the humanitarian worker associated with the Save the Children Fund wrote about the students of the Cizek workshop that “this contact with youth gave a special glow to my Vienna days — so that even now when I think of them, it isn’t starvation and relief work that come into my mind, but the laughter and gaiety of gifted children.”[43]

Originating from central Europe, carried out in the media of the moment and the place, images that testified to specific cultural graphic traditions were often used by humanitarians as a universal idiom. For his weekend lessons offered free of charge, Cizek would attract only interested youth, whom he coached through discussions, encouragement, and an aesthetic education anchored in a specific culture. Paradoxically, for his students’ work to keep the rhythmic and chromatic qualities he associated with children, his method required a work of plastic education, as well as thematic and formal restrictions. These prerequisites limited the idea of universality. Coming from another direction, anthropologist Margaret Mead, a contemporary of Wilson and Cizek, would share similar views regarding the ideas of purity and immediacy in childhood expression. From her travels in New Guinea during the early 1930s, she concluded that children left amongst themselves, removed from adults, tended more toward realism. She also observed that children raised in a culture penetrated by the supernatural did not show the same penchant for creative imaginative drawings as the young artists from the North.[44] As a result, the 35,000 childhood artistic productions that Mead brought back to the United States appeared to be more bleak and prosaic than the pieces from the Cizek collection. The drawings from Manus, which are now part of the Library of Congress collection, were not as popular in their time as the Viennese works.

With a return to peace, the humanitarians of the Save the Children International Union (SCIU), which grouped together the many national SCF chapters, refocused their energies toward the promotion of universal standards for children. In 1927, three years after the adoption of their Declaration of the Rights of the Child by the League of Nations, they launched a global drawing contest for children through the national committees and in conjunction with the International Bureau of Education. This involved illustrating the meaning that the new international prerogatives of the Declaration would have in the eyes of their recipients. The call was the act of reformists concerned about “popularizing and disseminating” the content of the Declaration, to ensure that children themselves were aware of their new prerogatives.[45] The SCIU received drawings from 12 countries, with widely varying degrees of participation: for example, 24,000 Mexican children and 57,000 French children entered the competition. A jury comprising two educators, a fine arts promoter, a pedagogue, and the vice-president of SCIU awarded medals to the best drawings selected by the national committees, organized an exhibit of the works received in Geneva, and chose to reproduce some of them to illustrate The Declaration of Geneva and the Child,[46] a work that would present the international agreement from the viewpoint of the holders of the new rights of children. The collection of 1,500 pieces was quickly dismantled when the SCIU sent most of the drawings back to participating organizations so that they could exhibit the art themselves.