I am honoured and grateful to have such a distinguished group of colleagues discuss Imperial Plots. Thanks to Jarvis Brownlie for organizing the panel and to Lara Campbell, Valerie Korinek, Carolyn Podruchny, and Katherine McKenna for their thoughtful and astute comments and insights at the University of Regina meeting of the CHA. As she had already published a review of my book, Katherine did not submit her remarks to this forum, but she was a valuable panel participant. I was pleased to see historian and former president of the CHA Lyle Dick in the audience as he reminded me that it was exactly 40 years earlier that we were working on the Motherwell Homestead National Historic Site in southeast Saskatchewan. That was my first introduction to homestead records and I was intrigued by the stories they contained, and the physical, social, and cultural landscapes sculpted out of the prairies through homestead laws. It was also my first foray into women’s history as I focused on material culture and the lives of the women of the Motherwell homestead. Often asked just when I started this project and how long I have worked on it, my answer would begin there, 40 years ago, although my curiosity about homesteading originated with my own family history in Manitoba. My dissertation, later published as Lost Harvests began my exploration of how Indigenous land was taken, carved up, and parceled out on the Prairies, and how notions of what constituted a “farmer” were deployed to exclude First Nations people from the central economic driver of the region: land and agriculture. Imperial Plots is in many ways a bookend to my first book, exploring how most women were excluded, settler and Indigenous, and the ideas pressed into the service of this exclusion. For the University of Manitoba Press, I was asked to list what I consider to be the most significant and distinguishing features of Imperial Plots. These are points I made: it places the history of the Canadian prairies in conversation with histories of gender, race and, colonialism in other colonial settings, yet it is grounded in the specifics of the Canadian West; it is the first study in this international field to consider the issue of settler colonial women’s access to land, adding a new gendered dimension to settler colonial studies; it expands understandings of how settler women were bound in “gendered patterns of disadvantage and frustration” while they simultaneously held positions of power over Indigenous people; it examines the complex intersection of ethnicity, race, gender, and class in the heated debates on women, land, and agriculture on the Prairies, in Canada and Britain; it contributes to understanding Western Canada as a colony of the British Empire, with an assumed “traditional” gender order as the foundation; it draws attention to the importance of the proximity of the United States in crafting the Canadian West as a British colony, drawing comparisons with the access settler women had to land in the United States; it analyzes the “homesteads-for-some-women” campaign, spearheaded by British women for British women, to the exclusion of others — theirs would be imperial plots where British civilization would be sown along with their crops; it emphasizes how the issue of access to land was a key component of the Woman Suffrage Movement in the West; it establishes the racialized and gendered architecture of the homestead system and Dominion Land legislation that was the foundation of settler colonialism in Western Canada; it is the first study of Canada’s women homesteaders, mostly widows with children; it explores women’s work on the land in the …

Macdonald Prize Winner Roundtable on Sarah Carter’s Imperial Plots: Women, Land, and the Spadework of Colonialism on the Canadian Prairies

Imperial Plots Roundtable Commentary: A Reply[Notice]

- Sarah Carter

Diffusion numérique : 14 novembre 2019

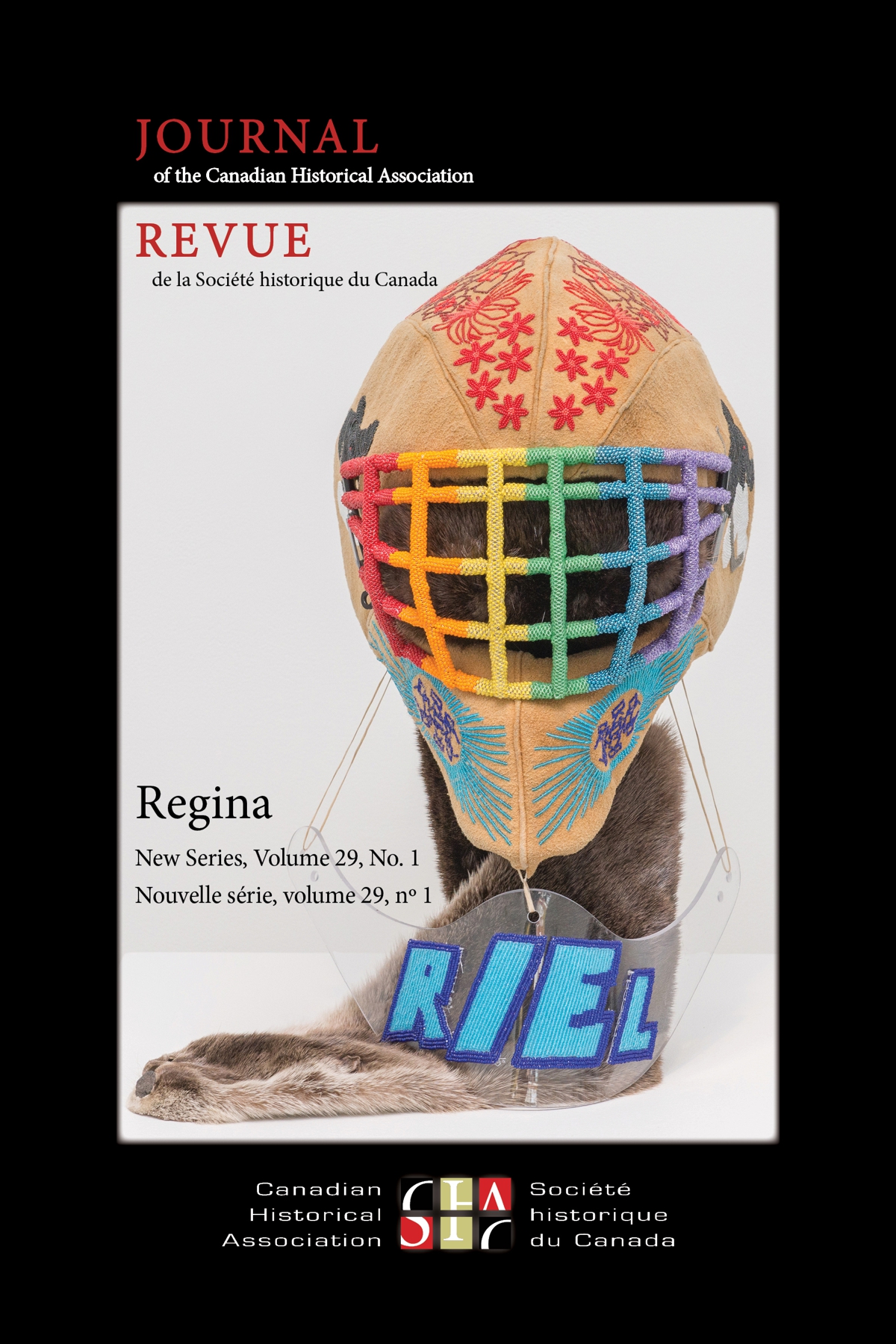

Un document de la revue Journal of the Canadian Historical Association / Revue de la Société historique du Canada

Volume 29, numéro 1, 2018, p. 190–204

All Rights Reserved © The Canadian Historical Association / La Société historique du Canada, 2018