Résumés

Abstract

D. Appleton’s Memoirs of the Empress Eugénie, published in English in 1920 in New York and London and in translation in Denmark, Germany, The Netherlands and Sweden, took a circuitous path to publication since the completion of the manuscript in Paris in 1908. The widow of Napoléon iii had contributed via interviews with her godson, Comte Maurice Fleury, stipulating posthumous publication. To protect the work from copyright infringement in the interim, Fleury and co-editor Theodore Stanton translated the French manuscript material into English and added content. A clandestine, anonymous “pre-edition” produced in 1908 established D. Appleton’s claim in Great Britain and the United States. The European publishers, expecting a French manuscript, were dismayed at translating a translation, while re-translation of their versions into English posed the greatest threat to copyright. By 1920, the work’s autobiographical, first-person narration had been modified to the third person and Fleury’s name added as author, but not all European editions followed suit. A mismatched set of supposedly identical translations was the result.

Résumé

Memoirs of the Empress Eugénie, publié en 1920 chez D. Appleton de New York et Londres (et, en traduction, au Danemark, en Allemagne, aux Pays-Bas et en Suède), connut un parcours pour le moins singulier depuis l’achèvement du manuscrit, à Paris, en 1908, jusqu’à sa parution « officielle ». L’impératrice Eugénie, veuve de Napoléon III, y avait apporté sa contribution par l’entremise de confidences faites à son filleul, le comte Maurice Fleury, à condition que la publication de ses mémoires soit posthume. Pour se prémunir contre toute violation du droit d’auteur dans l’intervalle, Fleury et Theodore Stanton traduisirent le manuscrit en anglais en plus d’y ajouter du contenu. Une sorte de pré-édition clandestine et anonyme commença donc à circuler en 1908 et permit par la suite à D. Appleton de se réserver les marchés américain et britannique. On imagine la consternation des éditeurs européens, réduits à publier la traduction d’une traduction. Leurs versions à eux, retraduites en anglais, constituèrent à leur tour une menace au droit d’auteur. À la mort de l’impératrice, en 1920, lorsque D. Appleton publia les mémoires, la narration était passée de la première à la troisième personne, et Fleury était désormais désigné comme l’auteur. La plupart des éditeurs européens n’ayant pas fait ces réaménagements, furent diffusées des traductions censées être identiques mais en réalité bien différentes.

Corps de l’article

At first glance, the bibliographical listings of original and translated versions of most books seem to indicate quasi-identical mirror publications, and indeed this was often the general intent in late 19th- and early 20th-century publishing. A close comparison of original and translated texts, however, which scholarly editors might term a collation if it were not a question of two languages and therefore two discrete texts, reveals nonetheless the influence of the books’ different chains of production. Many translated texts are similar enough to the original in form and content to make subtle differences that are explained by other historical evidence pertaining to the chronology and circumstances of their production – archived documents and correspondence, press items, and so on – readily discernible. Although translators endeavoured to render works “word for word,” more so in fact-based, i.e. journalistic, scientific, or historical texts than in creative works of prose and poetry, publishers had them working quickly, sometimes in teams, in order to meet tight and strict deadlines. Differences in style and accuracy are often apparent. At a time when mail still took nearly a week to reach New York from Paris, authors and publishers sent out instalments of advance proofs to be translated which often represented an earlier stage of revisions from the proofs sent to translators nearby. Further last-minute corrections were commonly made to the proofs of the original edition alone, but not to translators’ proofs. Translators also exercised an editorial function, subtle or overt, that reflected individual publishers’ regard for local social and technical standards, a primary concern of E. A. Vizetelly, Émile Zola’s translator in England whose father had been jailed for rendering Zola’s realistic novels too faithfully (see Speirs, Portebois). Paratextual elements, including illustrations, were chosen and deployed by individual publishers of translations, creating further differences between an original edition and its translated versions, as well as among the various translated editions.

The long and winding road to publication taken by Memoirs of the Empress Eugénie, published in two volumes by D. Appleton and Company in New York and London in 1920, and simultaneously in at least four European languages, illustrates some of the parameters of the type of translation that is intended to render an original text as exactly as possible. In translations of fact-based texts such as historical biographies and memoirs, linguistic and cultural precision is important in order to preserve a certain closeness to the subject or original actors who provide the raison d’être for the book. The authority of such texts depends on this perception of immediacy. When the publishers of the Danish, Dutch, German, and Swedish editions of Memoirs contracted with D. Appleton’s agent in Paris in 1906 for a manuscript that was being prepared in that city, they naturally assumed that a work to be called “The Memoirs of Eugénie or some such title” (A-C, Brockhaus contract, 30 Oct. 1908), with no additional author named, was an autobiographical account written by the consort of the last Emperor of France, Napoléon iii, and that the former Empress had composed it in French. Because of the manuscript’s odd composition method, however, involving translation and re-translation between French and English, and because of the urgency of establishing American and international copyright for the English-language version, no complete French-language manuscript of Memoirs of the Empress Eugénie ever existed. The European publishers objected to basing their translations on the English-language text they considered to be not only a translation itself but the result of an editorial and authorial collaboration that also cast doubt on the author’s identity. They solved the problem by heightening the perception of authenticity of their editions in various ways. Similarly, a French edition of Memoirs was rejected by publishers in Paris as a translation of an English text rather than a first edition of a French manuscript, which they preferred, given the book’s subject. A completely re-written French manuscript was commissioned, and completed, as a third-person account, but such manipulations must have eroded further the perception of authenticity of the pseudo-autobiographical “original” text. For this or other reasons it was never published. Similarly, negotiations for Italian and Spanish editions did not succeed.

D. Appleton and Company’s agent in Paris, Theodore Weld Stanton (1851-1925), had made his living there from around 1880 as a freelance journalist contributing to American and French newspapers, and as an editor and literary agent for the North American Review and other magazines. From the end of 1899, he was the Paris representative of the New York firm of Harper & Brothers for a few years (Beal, ch. 1). The president of D. Appleton, Joseph Hamblen Sears (1865-1946), formerly of Harper’s, wrote to Stanton as early as 1902 about acquiring the English-language rights to the memoirs the ex-Empress was rumoured to be preparing, saying he had been trying to penetrate the closely guarded secret since 1893 (TSP, Sears to Stanton 11 Jan. 1902). Stanton was well placed, both socially and professionally, to make inquiries among Eugénie’s acquaintances in Paris and to approach French publishers on Sears’s behalf about a simultaneous publication of French- and English-language versions of her memoirs. He learned that Eugénie absolutely refused the notion of writing her own book and had made no arrangements with publishers, but she had nonetheless been seen at the National Archives organizing family papers. This only encouraged a resourceful and persistent man like Stanton to consider the question still open and his way clear of competition. By 1906, he had made an ideal connection to the ex-Empress in her godson, Maurice Fleury, and persuaded him to collaborate on a manuscript of Eugénie’s memoirs. Without a French publisher yet on board, and seeing that Eugénie’s direct input would not extend beyond interviews with Fleury, Stanton and Sears re-fashioned the proposed work as an original, English-language project developed by D. Appleton instead of a translated edition of a manuscript produced for a French house. Although the second volume would be fleshed out by secondary historical material compiled by the two editors, Fleury and Stanton, the content of both volumes was to be presented in an autobiographical style, narrated by Eugénie. Theodore Stanton, as both editor and writer, made a specialty of this type of book compiled from papers and interviews. In 1910, D. Appleton published his authorized, illustrated biography of the artist Rosa Bonheur, which is regarded as the definitive contemporary account of her life and work. Biographies and reminscences were an important part of D. Appleton’s list at the time, according to a modern historian of the house (Wolfe, 315-6).

Eugenia de Montijo (1826-1920) was born into the historic aristocratic house of Guzmán in Granada, Spain. She was educated in Paris and in 1853 married Charles Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte (1808-1873), Emperor of the Second French Empire since 1851, when he had ended his presidency of the short-lived Second Republic through a coup d’état. The Emperor, called Napoléon iii, was later captured at the battle of Sédan in 1870, a débâcle that brought the Franco-Prussian War and the Empire to a close. The Third French Republic was declared, and monarchical forms of government were abolished for the last time. The exiled imperial court took up residence in England, and Napoléon iii died in 1873. Farnborough, Hampshire, where Eugénie settled in 1883, remained her home for the rest of her long life. After anti-imperialist public sentiment in France had abated to the point where she could safely return to the Continent, Eugénie travelled regularly to other residences she maintained in Paris and in Cap Martin near Monaco. Her only child, called Louis Napoléon, had been born in 1856. Maurice Fleury, Eugénie’s godson and future biographer, was the son of Général Émile-Félix Fleury, Napoléon iii’s confidant and top military adviser. Maurice was born in the Louvre Palace three months after Louis, the Prince Impérial. The two boys grew up together. After the young Prince was killed in 1879 while fighting for the British army in Africa, Maurice’s bond with Eugénie strengthened.

Comte Napoléon-Maurice-Émile Fleury (1856-1921), who used the hereditary title the Emperor had bestowed on his father, was familiar to Theodore Stanton in Paris publishing circles as the author of several books based on archival sources. From 1898 he was the editor of the illustrated monthly he had founded, Le Carnet historique et littéraire, and was a frequent contributor to French periodicals. Fleury had planned to publish a book based on his father’s papers and had already started recording Eugénie’s recollections with the same end in mind. He agreed to combine these materials for D. Appleton’s proposed international publication of her memoirs. Maurice Fleury’s lifelong filial relationship to Eugénie would be strained almost to the breaking point by his involvement in the project, but their devotion weathered the storm.

Empress Eugénie was a popular subject for readers in many countries during her reign and afterward. Known for her sense of fashion and design that had set the tone of opulent decoration associated with the Second Empire, she had also participated in state affairs as a political confidante of her husband’s, even replacing him as regent during his occasional absences. After her death in 1920, Eugénie’s story fed a nostalgia for the aristocratic life of the court that lingered in many European circles and still captured the imagination of North American general readers. Her former influence on affairs of state remained controversial and of lasting interest to political historians. Prominent figures like Eugénie attracted the publication of all kinds of unauthorized biographies and histories. Many such books are simply compilations of public records and press accounts. Authorized memoirs on the other hand, co-authored but written with the direct involvement of the subject, were of great interest to publishers if an autobiography – written by the subject herself – could not be obtained. Eugénie’s express endorsement of one account over another would set that publication apart. French historian Frédéric Loliée found a middle ground for a biography of Eugénie he published in 1907 as the third book of his trilogy, Women of the Second Empire, titled La Vie d'une Impératrice: Eugénie de Montijo d'après des mémoires de cour inédits. The reference in the title to “reminiscences of the court” implies Eugénie’s participation, but Loliée’s third-person account was created from the observations of Bernard Bauer, a chaplain of the imperial court and Eugénie’s former religious confessor, and from interviews with the statesman Émile Ollivier (Loliée 5-11). Stanton and Fleury’s manuscript was half finished by the time La Vie d'une Impératrice was published. They were certainly aware of Loliée’s book, but probably remained convinced that their version would be a more authoritative and comprehensive account of Eugénie’s life and times: Loliée’s method did not trump their plan to present the Empress’s direct testimony along with enough historical material from published and unpublished sources to run to 300,000 words and fill two volumes. The publisher’s descriptions of the work on the dust jacket flaps give an idea of the intended scope.[1]

Decisions about the authorial attribution and the narrative voice of the work caused problems from the beginning for the creators and publishers of Memoirs of the Empress Eugénie. Stanton had approached Fleury in early 1906, writing:

Would it be possible for you to undertake to prepare for the press a work that would be entitled Memoirs of the Empress Eugénie? To this end, you should be authorized to aid her and her friends to write and put in order the necessary materials. Your name would appear on the title page as the editor of the volume.

TSP, Stanton to Fleury 2 Feb. 1906

Fleury’s letters show his misgivings about the way Stanton and Sears were trying to position the project as an autobiography instead of a co-authored, authorized biography. In the presentation Stanton proposed, Fleury’s name would appear on the book’s title page as the editor, but would be omitted from the cover along with any mention of an author’s name. The title of the work would imply that Eugénie was the sole author, and bibliographical listings, by further assumption, would follow suit. It was a deft ploy, but the Empress would never have agreed to it. As Fleury explained, he had accumulated notes from personal conversations with Eugénie over the years. He had the Empress’s “tacit authorization” to use her life story in any of his publications, even to quote her at length in the first person, in effect, to write her memoirs, providing he published them under his own name (TSP, Fleury to Stanton 4 Feb. 1906). Express authorization was subject to the Empress’s approval of the finished text. Fleury’s sense of ethics forbade his agreeing to a first-person narration of secondary material in Eugénie’s voice, even if the publication was to be posthumous, as Eugénie had also stipulated. He was uncomfortable even asking permission for something he knew would be refused, and proposed instead to put the first volume of personal recollections in Eugénie’s voice and name and the second volume in his own. Fleury was adamant that this was the only option, for despite his close personal bond with Eugénie, one senses that his hold on her attention and her good graces was a matter entirely under her control, and his influence on her decisions somewhat limited.

Fleury proposed an alternative title that was more in keeping with his sense of “literary probity” (TSP, Fleury to Stanton 4 Feb. 1906): [Mémoires SUR L’Impératrice Eugénie: SOUVENIRS et ENTRETIENS] (emphasis Fleury’s), translated as [Memories of the Empress Eugénie: Recollections and Interviews] (all translations mine). In French, the preposition “sur” denoting reminiscences about the Empress instead of “mémoires de,” which could be read as “memoirs of” made the difference between the expectation of a unique autobiographical work and a biography, one among many. In English, the nouns and articles do the semantic work: the effect of Fleury’s suggested change was the difference in meaning between “the memoirs of” – the definite article could be easily inferred from Stanton’s title – and merely “souvenirs” or “memories of.” If an authorized biography, not an autobiography, was all Sears and Stanton could now hope for, they determined to maximize the perception of the work’s authenticity and exclusivity. Obtaining the Empress’s express approval of the manuscript became paramount.

Stanton and Fleury soon finalized the details of their collaboration and began work on the manuscript they estimated would take two years to complete. They agreed that one half of the manuscript was to be submitted to the Empress “or her immediate circle, for revisions, additions, and approval” (TSP, Stanton-Fleury contract 13 Feb. 1906). Fleury had not been persuaded to get two-thirds of the material approved, which would have covered much of the historical content in the second volume. Stanton countered with a clause requiring that the remaining half be submitted to the Empress “if possible.” Fleury, Stanton, and Sears, representing D. Appleton, then signed a tripartite agreement that contained subtle but important amendments. In Stanton and Fleury’s first agreement as co-editors, the question of the title of the work had not been addressed in writing. Now, Fleury accepted the clause naming the work, “The Memoirs of the Empress or some such title” (the phrase was re-used for the European publishing contracts), because in keeping with his understanding with Eugénie, his name would appear prominently as the author of both volumes, with Stanton’s remaining as editor. (Whether the significance of the definite article was lost on Fleury or not, it was eventually dropped in favour of the more ambiguous “Memoirs of.”) The circle of Eugénie’s courtiers who could authorize the manuscript was expanded: the text was to be prepared “under the direction, supervision and authorisation of the Empress herself, and her entourage and immediate circle of friends and attendants” (A-C, Stanton-Fleury contract 30 Apr. 1906). According to this prophylactic line of reasoning, Fleury could be said to have authorized the manuscript himself if it came to that. There was no royalty arrangement for Fleury’s participation as author. He sold his interest in the copyright outright, for a total of 24,000 francs (almost $5,000) and half the proceeds of the European editions which D. Appleton had ceded to Stanton in a separate agreement. Further, Fleury was required to surrender all of his manuscript copy, interview notes, and other supporting materials to Stanton. Ostensibly, this addressed the danger of a third party gaining access to them. A different motive, to preclude the possibility of Fleury’s defection from the project in future, is perhaps apparent in the clause: “The editor and publisher agree to edit and publish the said work in such a style or styles as may seem to them best suited to its sale […]”(A-C, Stanton-Fleury contract 30 Apr. 1906).

Fleury saw the Empress every other day during her visits to Paris in 1906 and 1907. He was confident that he would receive her express approval of everything he had written with her help. Franceschini Pietri, the Empress’s private secretary, handled the editorial details with Fleury on her behalf. As the manuscript chapters progressed, a Miss Didier, who evidently worked at Stanton’s office, translated them into English and returned them to Fleury, who was competent in English, for fact-checking and any additions. Stanton added material at this stage and forwarded the revised typescripts to Sears in New York. Fleury’s part was complete by January 1908. Meanwhile, however, and without Fleury’s knowledge, significant further interventions were made to the English manuscript: the style of the passages of direct quotation, in which Eugénie spoke in the first person, was applied to the rest of Fleury’s third-person narration. The resulting first-person manuscript created a completely different effect, now appearing as an autobiographical composition. Sears and Stanton may have imagined that they could bring Fleury around to obtaining or providing on his own a blanket authorization for the new presentation when the time came to publish, or that the deaths of Eugénie or even Fleury in the meantime might obviate the need for one.

From 1908, a more pressing problem for D. Appleton than proving the authenticity of the manuscript was protecting the firm’s considerable financial investment in the project. Stanton and Fleury had been paid in full for their part, some $10,000, and publication was to take place at an uncertain future date, upon the Empress’s death. Sears had to try to copyright the work immediately, for the longer he waited to publish Memoirs, the higher the risk that another authoritative memoir might be produced by another member of Eugénie’s entourage, or that a pirated edition could be made from clandestine copies of Fleury’s French manuscript or notes, or from a copy of the English-language manuscript in D. Appleton’s possession. An unpublished manuscript could not be registered for copyright, however, under the guidelines of the international Berne Convention that had helped to standardize copyright law in Great Britain, France, and other countries since 1886, or under the 1891 International Copyright Act in the United States, where Berne did not apply. A memorandum from D. Appleton in New York to its London office shows how acutely aware Appleton executives were that “premature publication would be disastrous. The utmost importance attaches to keeping the Memoirs from the light until the right moment arrives” (A-C, memorandum 27 Oct. 1908). Adding to the sense of urgency was the fact that Stanton was beginning to promote the work to European publishers, who naturally wanted to read as much of the manuscript as possible before committing to such a substantial, long-term venture. From the moment publishers had a complete copy in their hands from which to prepare translations, a real danger existed that while they waited, possibly for many years, to publish, the English-language manuscript would be copied, or worse, the work would be re-translated into English. If such a pirated edition were copyrighted in a Berne member country and in the United States, English-language markets worldwide would be closed to the legitimate edition.

The potential financial loss of the English-language rights of Memoirs was a much greater threat than it was for versions in other languages, hence the decision to use English in the composition and editing process with a view to copyrighting the work in that language. A manuscript in English prepared the way for a plan that was devised to register the property for American and international copyrights without actually publishing it in the normal sense. The D. Appleton memorandum continued:

[T]he safest method of protecting the copyright [is] to have the original French manuscript translated and edited in English; that the French manuscript should then be destroyed; that the English manuscript would then become the original form of the book; that this manuscript should be set up in book form in this country and copyrighted simultaneously here and in England.”

A-C, memorandum 27 Oct. 1908

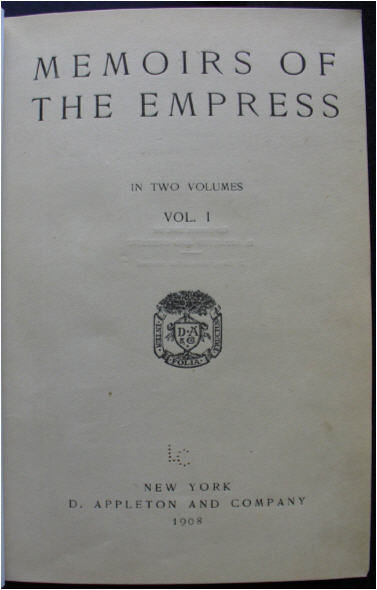

The firm set up and paginated the entire two-volume book and printed several copies, some with American and some with British title pages, according to the standard procedure at the time. The book was neither announced nor distributed to the general public in either country. No author is listed on the title page of the American version (the British seems not to be extant), and Fleury’s and Stanton’s contributions are completely concealed. Two sets of Memoirs were received on 3 December 1908 by the Library of Congress for legal deposit, a pre-requisite of American copyright protection. The work was registered under an anonymous author, “in order to do whatever may be possible to screen the copies from observation there” (A-C, memorandum 27 Oct. 1908). Also to this end, perhaps, the truncated title Memoirs of the Empress was used for the title pages as well as for the copyright registration and Library of Congress catalogue listing derived from them. See Figure 1. In preparation for a conventional re-issue of the work at a later date, however, running titles on each verso page of both volumes consist of the full title, Memoirs of the Empress Eugénie. Only the title pages would need to be re-done for a subsequent edition. The 1908 edition is not illustrated.[2]

Fig. 1

Title page vol. 1 of Memoirs of the Empress (1908)

Because of the way the United States, Great Britain, and its colonies shared a common language and literary heritage but practised different approaches to copyright, authors and publishers seeking to publish beyond their own borders struggled to keep up with the legal requirements and practical hurdles associated with simultaneous publication across the Atlantic. Partly for this reason, American and British publishers forged transatlantic alliances with other houses or opened branch offices in London or New York (or Boston, or Philadelphia). The formalities for obtaining copyright differed between the two countries. In the United States, copyright depended on registration, before publication, of the title page of a work and subsequent deposit of two copies at the Library of Congress, in addition to having had the work typeset and printed within U. S. borders. D. Appleton followed this procedure exactly for the 1908 Memoirs of the Empress. For the British edition, the firm elected not to register the work, perceiving a loophole in the copyright statutes that required registration at Stationers’ Hall, but only as a pre-requisite to proceeding against eventual infringers. Formal registration would then have engendered official requests for compulsory library deposits of the work, with a penalty of five pounds for not doing so, however, failure to register or deposit did not invalidate copyright. (Formalities were eliminated entirely with the overhaul of the Copyright Act in 1911. See Bently, Kretschmer.) The act and proof of publication were understood to mean the release of a work to the public. As John Feather has noted, the “copy” in British copyright law had always been a physical rather than an intellectual concept, and a literary work began to exist as a legal property only “when it came into the hands of a bookseller” (Feather, 67). To guard against the exposure that this unavoidable step might cause, it was proposed that the London office establish proof of publication in British territory thus:

[…] to make pro forma sales (as few as in your judgment will be sufficient) and to repurchase, as retail purchasers and as individuals, the copies previously sold by you. [...] We should prefer the risk of being called upon to pay the fine, to the risk of publicity which would attend the deposit of the work in the libraries.

A-C, memorandum, 27 Oct. 1908

Such limited or pseudo-public prior sales, designed to establish a legal publication date before a book’s intended release, were not uncommon in the case of books with a wide distribution and a co-ordinated release date, according to one publishing manual of the day that refers to the practice as “technical publication” (Hitchcock, 265). The New York office shipped copies of Memoirs of the Empress to London a few days later. D. Appleton’s claim to the work was now established in both crucial zones, but the urgent need for secrecy continued: the existence of Eugénie’s first-person autobiography had to be concealed from its famous subject as well as from its real author, Fleury, who was still unaware of it.

Among the publishers in Denmark, Germany, Italy, The Netherlands, and Sweden to which Stanton now turned his attention, foreign copyright infringement was not a concern. Not only were foreign markets very small for books in languages other than French and English, most of those countries were bilateral treaty partners with the United States and all were members of Berne by 1912. (The United States moved closer to an international standard in the 1950s and finally elected to join Berne in 1988). Re-translation into English from one of those translated versions remained the greatest threat. Stanton’s negotiations with European publishers continued from 1908 through 1910. D. Appleton’s control of the date of publication of all versions simultaneously with the original was explicit and often repeated. Stanton stressed the utmost discretion about the project in his initial offerings, even concealing the subject’s identity as long as possible, but the secret of the covert publication of Memoirs of the Empress was not kept for very long. Stanton’s choice of the Ulrico Hoepli firm in Milan was unfortunate in retrospect. As the publisher to the Italian royal court, the “moral risk” involved forbade the firm from publishing a work narrated in the first person and “cheating the public” (TSP, Hoepli to Stanton 12 June 1909). The director Ulrico Hoepli reduced his offer drastically, saying he would only consider publishing a third-person historical account authored by Fleury, because “the ‘I’ form which authenticate[d] the book [made] out its whole commercial value” (TSP, Hoepli to Stanton 12 June 1909). Corresponding with Carlo Hoepli, the director’s nephew, Stanton justified the editing approach to the narration thus:

[A] large portion […] is composed of extracts from letters by the Empress or reports from conversations with her, which large body of matter was originally in the first person, but which we put into the third person and which now has been put back into the first person, as it should be. In a word, the book is nearer right in the first person than it would be in the third person.

TSP, Stanton to Hoepli 21 June 1909

In the same letter, the usually nimble-minded Stanton committed a faux pas with the Italian firm, asking Carlo Hoepli if it was not a little “pretentious – excuse the word, which is meant only for your ear but which exactly expresses the way the matter looks to a third party – ” for his uncle to be “‘making a mountain out of a mole-hill,’ as we say in English” (TSP, Stanton to Hoepli 21 June 1909) by not acquiescing to an arrangement other leading European publishers had already accepted. Stanton’s comments were naturally passed on to Ulrico Hoepli. Negotiations came to a swift close, and the Italian firm returned by registered mail the two volumes of proofs Stanton had provided as a prospectus (TSP, Hoepli to Stanton 25 June 1909).

News of Memoirs of the Empress travelled through international royal and imperial circles. On July 7, 1909, the Empress’s private secretary Franceschini Pietri, who had also served the Emperor in that role and who remained a powerful member of Eugénie’s entourage, wrote a letter to the Paris Figaro, stating that her Majesty insisted that she had not written nor intended to write her memoirs, and that any biographical account attributed to her in any way could only be apocryphal. Pietri’s letter was reprinted or reported by numerous other newspapers in Paris, London, and New York. He followed up in October with a polite but warning letter to D. Appleton, implying that legal action would ensue if the firm published the book. For Sears, cancelling the publication was out of the question, but now so was the possibility of issuing even a revised version while the Empress and Franceschini were still alive. He waited, counting as usual on Stanton to manage Fleury.

Maurice Fleury was still unaware of the extent of the transformation that had been wrought on the English typescripts he had approved. He had only heard that the memoirs were being represented as an authorized publication. Vague rumours about the secret edition circulated for weeks, based on Hoepli’s account of it. For the time being, Fleury could plausibly deny his involvement to Eugénie until in August 1909 an article in the British press identified him as the author and revealed the first-person composition. A clipping had been sent to him from Farnborough, undoubtedly accompanied by the Empress’s admonishments. Fleury had been corresponding with Stanton in English all along, but reverted to French to voice his vehement objections at length. Fleury seemed to blame Sears and the Appleton firm, but not Stanton, for contravening the tripartite agreement, adding that he would deny any part in the result: “les éditeurs [the publishers] ont dépassé ce qu’ils pouvaient faire et je déclinerais une responsabilité puisqu’on a fait le contraire de ce qui était convenu d’abord” (TSP, Fleury to Stanton 8 Aug. [1909]). He advised that the edition be suppressed or completely revised, a costly option that would require re-setting the type. Stanton sailed for New York to confer with Sears. They evidently chose not to abandon the project and resigned themselves to re-writing the lengthy book, but no record of their explanation to Fleury about what had transpired or how they would proceed has been found.

By the eventful summer of 1909, Stanton had already sold translation rights to Memoirs of the Empress to publishers in Germany, Denmark, and Sweden, and provided them with complete printed copies – probably unbound sheets, or “slips”– of the 1908 English-language “technical edition” to translate. Negotiations for the Dutch-language edition were in progress. Georg Hansen, representing the Danish publishing firm Gyldendalske Boghandel, expressed his concern to Stanton about reports of Pietri’s statement in the press, but his firm had paid for the work in full by that time. He was close to finishing setting up the type and illustrations, and it was too late to turn back. Stanton was able to allay Hansen’s doubts about the authenticity of the work by explaining why the German publisher, F. A. Brockhaus, was less wary. Brockhaus reportedly understood that the work was not yet authorized at that moment, but it was written into his contract – which served as a template for the other European contracts – that the text would receive the Empress’s express authorization by the time it was published. The Danish publisher was satisfied with the additional proof that Fleury’s contract also seemed to guarantee the court’s express authorization. Then, at the beginning of January 1910 Jules Claretie, the prominent writer, academician, and director of the Comédie française, denounced the rumoured memoirs as a fraud in a column in Le Temps. He claimed only to be interested in serving history when he informed readers Eugénie had not written a line of the book. That revelation was literally true, but its implication of a false first-person narration was more damaging. It certainly ruined the negotiations with Paris publisher J. Tallandier for a French edition and kept Stanton occupied with a flurry of enquiries from Hansen, Brockhaus and others about Claretie’s reference to a “bold forgery” (TSP, Brockhaus to Stanton 17 Jan. 1910).

The French, American, and international press kept the controversy alive for two years. A disingenuous note, however, is struck by the continued claims of journalists in Paris and New York, to whom Stanton and Fleury were well known, that the identities of the creators of Eugénie’s “false” memoirs were a mystery to them. Claretie himself had cordial working relations with Stanton both before and after the controversy. Perhaps there was a reluctance to libel their colleagues in print or add to Fleury’s difficulties with the court, but Stanton’s shrewdness and talent for networking and marketing probably led him to take advantage of the situation. Franceschini Pietri’s own repeated protestations that the identity of the memoirs’ authors was unknown ring especially false in his statement in January of 1910, after Claretie’s piece had forced him to comment again and he announced the Empress’s decision not to sue. Sears and Stanton evidently reaped the benefit of the way the court had acted to protect Fleury, and the furore subsided before their identities were made public.

It appears that Sears watched and waited until 1912 to make a decision about re-fashioning Memoirs into an acceptable form. His lack of a reply to the court since 1909 infuriated the Empress and left Fleury in an uncomfortable position. Still, Fleury was gracious enough to see the project through, offering to revise the text for the new edition. In this version, which is the one D. Appleton published in 1920 after the Empress had died at the age of 94, the first-person narration remains, but it is now in Fleury’s voice throughout. His name appears prominently as the author. Fleury repeated his belief in the meantime that if the book had been written as he had proposed, as a third-person biography – mémoires sur l’Impératrice – that she would have given them the “imprimatur” they desired in the form of an endorsement to appear in a frontispiece to the work (TSP, Fleury to Stanton 30 Mar. 1912). That opportunity had vanished. Eugénie never did openly recognize Fleury’s book, the only biography with which she had been directly involved (TSP, Stanton reminiscence Jan. 1923).

Prior to publishing Memoirs of the Empress Eugénie in 1920, D. Appleton did all it could to salvage some of the authority that had been lost along with the Empress’s authorization and set about affirming the authenticity of the work by other means. For instance, the title was expanded to emphasize the originality and exclusivity of the source material:

Memoirs of the Empress Eugénie. Compiled from Statements, Private Documents and Personal Letters of the Empress Eugénie. From Conversations of the Emperor Napoleon iii and from Family Letters and Papers of General Fleury, M. Franceschini Pietri, Prince Victor Napoléon and Other Members of the Court of the Second Empire.

Maurice Fleury’s name appeared as the author, but as “Comte [Count] Fleury.” See Figure 2. Further, at the insistence of William Worthen Appleton, by then the firm’s president, Stanton answered questions about Fleury’s “position” in the imperial household and the exact nature of his “very close relations with the Empress” (TSP, Appleton to Stanton 13 July 1920). Stanton provided a four-page, typed letter quoting his extensive correspondence with Fleury in which Fleury had given details of his meetings with the Empress and with influential members of the court. Stanton was evidently aware that he was writing to the firm’s lawyers, for he cautiously avoided vouching personally for the veracity of Fleury’s statements. Over his signature Stanton wrote: “The statement made above is wholly based on Count Fleury’s communications to me, and if what he says is true, the statement is true” (A-C, Stanton to D. Appleton 23 July 1920). Sears had foreseen these legal considerations at the time the manuscript had been completed and had obtained the following signed statement in Fleury’s hand: “The documents and conversations contained in these two volumes are, to my best knowledge, authentic” (A-C, Fleury to D. Appleton 19 Aug. 1908).

Fig. 2

Title page vol. 1 of Memoirs of the Empress Eugénie (1920)

An undated memorandum in the D. Appleton files, attached to galley proofs of the revised 1920 title pages, refers to the word “authorized” having been removed from the title pages, on the advice of the firm’s lawyers. Fleury’s avowal of the authenticity of the “documents and conversations” appears there instead. For biographical works, a world of difference existed between an authorized edition and a merely authentic one, but Appleton was obliged to settle for the latter. Stanton closed his report to William Appleton by saying that Fleury had “loyally carried out the spirit of his promise, though some eleventh-hour intrigue and political manoeuvres […] prevented him and the Empress from going as far as they intended to do in this direction” (A-C, Stanton to D. Appleton 23 July 1920). The waters obviously ran deeper in the Hoepli-Pietri and Claretie affairs than the surviving documents allow us to understand fully.

For the 1920 transatlantic, English-language edition, D. Appleton employed paratextual elements to further bolster perceptions of imperial authority about the work. In addition to crown and fleur-de-lis type decorations on the title page, the hardcover binding is in royal blue cloth.[3] See Figure 3. Blind-stamped in the centre is a circular crest of laurels enclosing the upper-case initials: NE for the Napoleonic dynasty. The title, Memoirs of the Empress Eugénie, is centred at the top stamped in gilt upper case.[4] Placed diagonally at the bottom right, also embossed and gilt, is a facsimile of Fleury’s signature, copied from the 1906 publishing contract. Each volume has a frontispiece with a different portrait of Eugénie. (The artists are not credited.) Apart from these two plates, the edition is not illustrated, even though, according to Stanton, 60 illustrations had been planned at one point (TSP, Stanton to Georg Hansen 18 May 1909). Some 32 illustrations are known to have been produced, and many of these were used in the foreign-language editions.

Fig. 3

Cloth cover vols. 1 and 2 Memoirs of the Empress Eugenie (1920)

Memoirs of the Empress Eugénie was serialized in at least four American newspapers, including the Boston Post, the Buffalo Times, the Philadelphia Bulletin, and the Seattle Times (A-C, United Features Syndicate account statement 21 Dec. 1921). Serialization rights had been reserved by D. Appleton, and no royalties were due to Stanton or Fleury for the proceeds of these subsidiary publications. It is not known if any European serializations of this work appeared. Most of the European publishers Stanton was dealing with considered prior publication in serial form to be detrimental to the sales of their book editions.

A brief look at Stanton’s contract negotiations from 1908 through 1910 with European publishers for the translated editions of Eugénie’s memoirs reveals the special challenges those publishers encountered trying to supply small, adjacent and overlapping markets of readers in different languages. Therefore, when it came to copyrights, publishers thought in terms of language groups instead of political boundaries, and this is reflected in their contractual arrangements with Stanton. Germany was by far the largest European publishing market outside France and Great Britain. At 25,000 French francs for exclusive rights to Memoirs within its territory, the F. A. Brockhaus firm paid more than ten times the copyright fee Stanton was able to charge other European publishers, for whom the asking price was 2,000 or 3,000 francs. The four Continental publishers which set out to publish quasi-identical translated editions of the same work ended up producing a curiously mismatched set of texts in very different-looking books.

German, Bohemian, Hungarian, Polish, and Russian copyrights: F. A. Brockhaus, Leipzig.

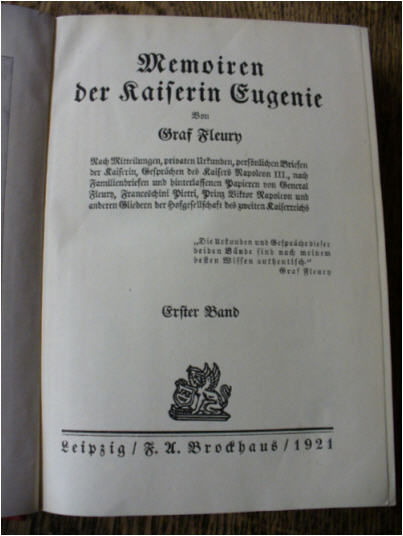

Fritz Brockhaus was eager to license his translation of Memoirs in “all countries where the German language is spoken or read,” not just in the political territories of Germany and Austria-Hungary (TSP, Brockhaus to Stanton 11 May 1908). In addition, he found it necessary to include Bohemian [Czech], Hungarian, Polish, and Russian languages in the copyright, because many readers in those dispersed groups would buy the German edition if no other were available in their language. Thus, “editions in these languages would reduce the sale of the German edition to a higher degree [than] the French and English editions” (TSP, Brockhaus to Stanton 11 May 1908). In the course of bargaining, Brockhaus conceded the Russian and Polish markets to Stanton (which Stanton did not exploit), because editions in those languages would have the least effect on a German edition, but he insisted on keeping the Bohemian and Hungarian rights. He did not necessarily intend to publish editions in those languages, but he had to be sure no other publisher would do so, as those editions would also benefit from his promotion of the German translation (TSP, Brockhaus to Stanton 5 June 1908). When the time came to publish the book, Brockhaus, fully aware of the well-publicized legal threats facing the phantom 1908 edition narrated in the first person, and in light of the high profile and wide distribution of the German edition and the close ties between royal families in Germany and Britain, where Eugénie’s court still resided, adopted D. Appleton’s prudent approach and completely revised the German version. Instead of taking on the responsibility and expense of independently amending the text, F. A. Brockhaus waited for a copy of D. Appleton’s final revision, probably the finished volumes, and amended its translation from it, producing a quasi-identical version which the firm issued the following year, in 1921. The delay posed no copyright problem: simultaneous publication was no longer necessary, as German and other translation rights had been reserved at the time of the London edition according to the Berne Convention. The German edition, printed in Gothic typeface, is an exact rendering of D. Appleton’s 1920 version, down to the expanded title, Count (Graf in German) Fleury’s prominent authorship, and his affirmation of authenticity on the title page. Red cloth covers show an eagle crest over the letter “N,” and 14 photographs appear in all. See Figures 4 and 5. If Brockhaus produced a Bohemian or Hungarian edition, none has yet been found.

Fig. 4

Cloth cover vol. 1 of the German-language edition

Fig. 5

Title page of the German-language edition

Italian and Spanish copyrights: Fratelli Treves Editori, Milan; Ulrico Hoepli, Milan; Società Tipografico-Editrice Nazionale (S. T. E. N.), Turin.

Theodore Stanton had already corresponded with the Italian publisher Fratelli Treves [Treves Brothers] from December 1908 to February 1909, when he entered into his ill-fated correspondence with the Ulrico Hoepli firm. Emilio Treves had wanted guarantees concerning the dates of any serializations of Memoirs in international periodicals, which Stanton could not provide to his satisfaction. Treves thought that prior publication of any parts would surely be translated for the Italian press and would “slacken greatly the interest and the surprise of the book” (TSP, Treves to Stanton, 1 Feb. 1901). He declined Stanton’s offer. Subsequently, Ulrico Hoepli cited the small market for Italian translations of this type of book, which many Italians preferred to read in French. Not only was book publishing in general “too narrow a business in Italy,” referring to the slim profit margins due to lower cover prices than elsewhere, the closeness of the Italian and French languages in matters of syntax and expression made Hoepli hesitate at producing a translation from an English manuscript of the work: “translating from a translation would be a nonsense” (TSP, Hoepli to Stanton, 5 Apr. 1909). Hoepli enquired about the Spanish-language rights, which his firm often exploited for other books, but negotiations broke down over assurances of the Empress’s authorization. In April 1909, Stanton offered Memoirs of the Empress to a third Italian firm, the Società Tipografico-Editrice Nazionale (S. T. E. N.) in Turin. Marcello Capra wrote on behalf of the firm that the small Italian book market did not extend internationally the way markets for French, English, and Spanish books did. He, too, insisted that the first-person narration be expressly authorized by the Empress herself or by her late son’s heir, Prince Victor-Napoléon, pretender to the Bonapartist throne. Capra’s main objection was to translating the work (which he assumed was in French) into Italian from English. As he explained to Stanton, similar nuances in French and Italian expression would suffer from a metaphorical detour across the English Channel and back: “Trop de nuances françaises qui ont leur correspondance italienne se perdent par suite de la traversée de la Manche et du retour au-deçà des Alpes” (TSP, Capra to Stanton 10 May 1910). They did strike a bargain (the exact details of which have not been found) and agreed to meet in Paris in July to formalize the contract, but it must have fallen through. No further details were preserved in Stanton’s papers, and no Italian or Spanish edition of Memoirs of the Empress Eugénie appears to have been published by S. T. E. N. or any other firm. The absence of any contact with publishers in Spain, Eugénie’s country of origin, still begs an explanation.

Danish and Norwegian copyrights: Gyldendalske Nordisk Forlag, Copenhagen.

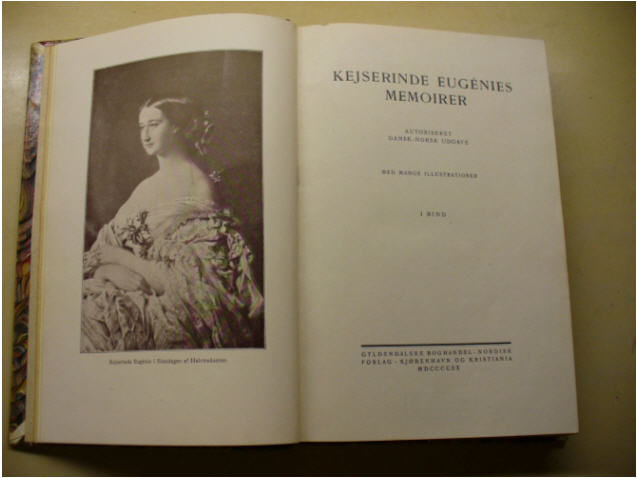

Georg Hansen of Gyldendalske Boghandel, like the Italian publishers, faced small returns on small print runs of translated books. As he informed Stanton: “the reading public in Denmark and Norway is very limited and most people who are interested in foreign persons and incidents prefer to read such a work in the original language” (TSP, Hansen to Stanton 6 Jan. 1909). Hansen reserved the Norwegian-language rights along with the Danish rights, because the Gyldendalske firm was in a similar situation to F. A. Brockhaus regarding adjacent language groups. Hansen said that he would probably not publish a Norwegian edition (none has been found), but because many Norwegians read Danish, a Norwegian edition from a competitor would reduce sales of the Danish edition. Having seen Stanton’s 1908 prospectus copy of Memoirs of the Empress, Hansen went ahead and ordered the “manuscript.” Astonished to be referred to the English sheets, he wrote back, “is the original not written in French? (TSP, Hansen to Stanton 15 Aug. 1909). Stanton explained the unusual editorial process anew. Persuaded, Hansen prepared the book for the press during that summer, to be ready for publication when the time came. Stereotype or electrotype plates were a common and economical way to hold typeset work for later printing, but changes could not be made to them. As a result, the two-volume edition Gyldendalske issued in 1920 is an unaltered translation made from the 1908 version of Memoirs of the Empress. It is narrated in the first-person voice of Eugénie. The Danish title translates into English as [Empress Eugénie’s Memoirs]. No author was listed by Royal Library cataloguers. On the title page appear the words (in Danish), “Authorized Danish-Norwegian Edition.” See Figures 6 and 7. The soft-cover edition is beautifully and profusely illustrated with 60 black-and-white photographic plates as well as drawings inserted in the text, only 32 of which D. Appleton had provided. It is unlikely Gyldendalske arranged a serialization in Scandinavian periodicals, because Hansen was of the same opinion as the Italian publishers that serialization would diminish book sales. A Norwegian-language edition seems not to have been produced.

Fig. 6

Paper cover vol. 1 of the Danish-language edition

Fig. 7

Frontispiece and title page vol. 1 of the Danish-language edition

Swedish copyright: Beijers Bokförlagsaktiebolag, Stockholm; A. Bonnier, Stockholm.

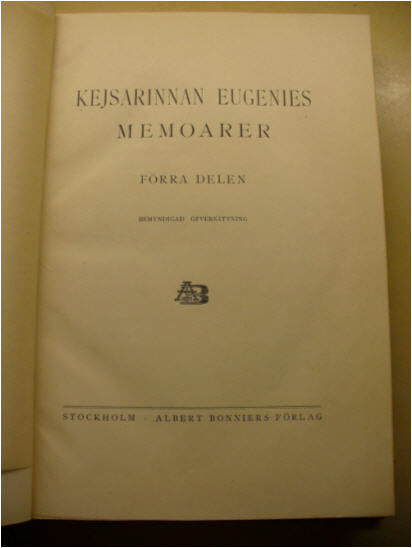

Stanton would have been fortunate if all of his European negotiations for Memoirs had gone as smoothly as those with the Stockholm firm of Beijers Bokförlagsaktiebolag. The Swedish edition, in two volumes, was published in 1920 by A. Bonnier, another Stockholm firm that had absorbed Beijers a few years earlier. The Swedish text, like the Danish, is a translation of the 1908 Memoirs of the Empress. It is written in the first person, and “Eugénie, Empress of France” appears in catalogues (in Swedish) as the author. The Swedish title translates as [Empress Eugénie’s Memoirs], and the lines below the title as “Authorized translation.” See Figures 8 and 9. The edition has 32 photographic plates, for which Stanton had provided electrotypes. (Corresponding with the Beijers firm in English, Stanton used the French jargon for the plates, “galvanos.”) One surviving copy of the Beijers / Bonnier edition is known to have migrated to Swedish reading communities in Minnesota, USA.

Fig. 8

Paper cover vol. 2 of the Swedish-language edition

Fig. 9

Title page vol. 1 of the Swedish-language edition

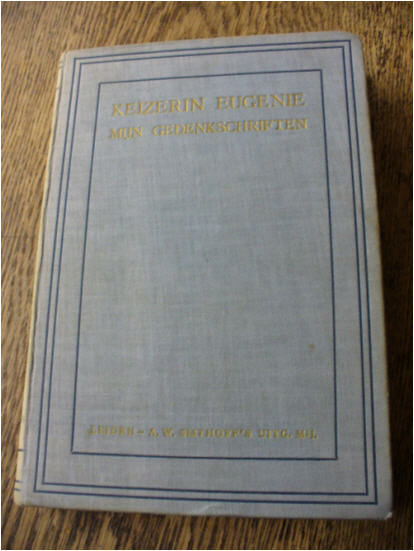

Dutch copyright: A. W. Sijthoff’s Uitgevers-Maatschappij, Leiden.

Readers in The Netherlands bought books in several languages. Representing the firm of A. W. Sijthoff’s during the summer of 1909, A. W. Frentzen was disinclined to pay Stanton’s asking price unless French, English and German editions of the work were not distributed in The Netherlands within 12 months of publication. He was sure that his “friends” the other European publishers would agree, in addition, not to sell their first editions for too low a retail price, under 20 francs (TSP, Frentzen to Stanton 22 July 1909). Frentzen and Stanton came to an agreement, but the written contract included no mention of such restrictions. Sijthoff’s ordered illustrations and used all 24, but few details survive that would shed light on any second thoughts Frentzen may have had about the language of the “manuscript” or its authenticity following the appearance of the negative press in 1909. Similar to the Scandinavian editions, the two-volume edition Sijthoff’s published in 1920 appears to be Eugénie’s legitimate, exclusive autobiography. The Dutch title translates as [My Memoirs]. “Eugénie, Empress of France” appears (in Dutch) at the head of the title page, and below the title one reads “Authorized edition.” See Figures 10 and 11.

Fig. 10

Cloth cover vol. 1 of the Dutch-language edition

Fig. 11

Title page of the Dutch-language edition

Any readers of the Danish- Swedish- and Dutch-language versions of Memoirs of the Empress who were unaware of the controversy that had surrounded the work more than a decade earlier must have enjoyed the vivid impression of reading, in her own words, the life story of the last Empress of the French. It is still unclear how these editions were received by European critics, or whether the house of Bonaparte raised any further challenges. The Great War had since intervened and changed publishing landscapes and priorities for all concerned. Pietri had died in 1915, and Fleury survived his godmother by only one year. Stanton was organizing his own papers at Rutgers University, to write his memoirs perhaps, when he died in 1925. He seems not to have kept a record of private reactions to or press reactions of this odd family of books he had helped create. (Reviews of the D. Appleton edition were lukewarm, citing historical inaccuracies and Fleury’s uncritical devotion to Eugénie and the court). At the same time as the Continental editions were being prepared, a proposed French edition led Fleury and Stanton’s globe-trotting, collaborative manuscript through yet another transformation.

French copyright: Arthème Fayard, Paris; J. Tallandier, Paris; Plon-Nourrit, Paris.

A French edition of Memoirs was proposed to two firms in Paris, Arthème Fayard and J. Tallandier, before a third, Plon-Nourrit, committed in 1910 to publishing a revised version of the work. Even this one never appeared. Maurice Fleury had met with the director of Fayard in November or December 1908, but nothing had come of their discussion. Jules Tallandier, of the J. Tallandier firm, was in the process of evaluating the first volume of Memoirs in order to decide whether to publish the work under his Illustrated Library imprint when Claretie’s column appeared in Le Temps. Allowed to work with Fleury’s partial French-language manuscript as well as the English, Tallandier showed a keen insight into the quality and origins of the text. He did not object per se to Fleury’s role as Eugénie’s editor or even ghostwriter, as the Italian publisher had. Tallandier was surprised and annoyed by Claretie’s aspersions of a complete fraud, however, and insisted thereafter on an iron-clad, express and written authorization from the Empress herself or Prince Victor, as a condition of publication. Tallandier compared the biographical and historical details in Memoirs of the Empress to those presented by Frédéric Loliée in his 1907 biography of Eugénie and had found no new material. He thought the plodding divisions of the volumes and the overall style needed to be improved in favour of a more literary form. Additionally, the back-and-forth translation method of the most original portion of the work, Fleury’s interviews with Eugénie, was evident to him, leading him to declare the work unfit for publication: “[J]e trouve l’ouvrage tel qu’il est rédigé, absolument impubliable en France” (TSP, Tallandier to Stanton 11 Feb. 1910). Having placed these two absolute conditions on accepting the work – authentication and a complete re-write, in French – Tallandier was still open to publishing it, perhaps on a royalty basis, but no agreement was reached. Stanton and Fleury subsequently approached Plon-Nourrit in Paris, a frequent publisher of works of history and biography. At that firm’s suggestion, they were willing to see the work re-cast as a third-person historical work authored by Fleury instead of a pseudo-autobiography of the Empress. In June 1910, J. Bourdel of the firm purchased the French-language copyright for the proposed new manuscript for 4,000 francs.[5] The working title was close to Fleury’s original idea, “Souvenirs sur le Second Empire et la cour impériale.” Georges Bernard was selected as editor to create a polished, cohesive, French-language manuscript, by re-ordering the two volumes of the English-language version and going back over Fleury’s French manuscript, notes, and archival sources. He completed the task and received 1,000 francs (TSP, Bernard to Stanton 10 Nov. 1910). The revised title acknowledges the importance of Général Fleury’s archived papers behind Maurice Fleury’s historical writing, and also re-introduces a biographical element, finally casting the work as Général Fleury’s memories of the Empress as told by his son: “Les Souvenirs du Général Comte Fleury sur l’Impératrice Eugénie et le Second Empire: recueillis et mis en ordre par son fils.” The Plon-Nourrit edition was to appear after Eugénie’s death, simultaneously with all other versions of Memoirs of the Empress Eugénie, but in 1912 J. Bourdel wrote to Stanton asking him to cancel the arrangement, regretting that the conditions under which it had been made had changed irrevocably (TSP, Bourdel to Stanton 7 May 1912). No more can be gleaned from their correspondence, but personnel changes and financial difficulties at the firm seem to have been the cause. Stanton waited several months for the firm’s fortunes to improve, but eventually he had no choice but to refund Plon-Nourrit’s payment. He did not succeed in selling the French-language copyright elsewhere before French publishers were overwhelmed by war in 1914.

The European publishers of translations of Memoirs of the Empress Eugénie had an array of different priorities and concerns that seem to adhere to rather stereotypical patterns: the German publisher wished to produce as exact a rendering of the original text as possible, for reasons of historical authority. (He had pointed out quite a few inaccuracies in Fleury and Stanton’s synthetic work in the second volume.) The Italian publishers were concerned with expressiveness and nuance in the text. The French publishers focussed on matters of literary and aesthetic style. Certainly the translators hired by each of the different publishers left traces of these priorities in the new texts they produced, even though the translations were obviously meant to be exact. The language of the text on which translations would be based was central to all of these concerns. In the creation of Fleury and Stanton’s manuscript, translation was not a separate or one-time function. Translation and re-translation were repeatedly intertwined with the composition and editing process.

In the matter of copyright, English-language texts had a particular problem due to the different system that remained in force in the United States even after 1891. It would be interesting to investigate whether other publishers, like D. Appleton, published pro forma editions like the 1908 Memoirs of the Empress in their efforts to co-ordinate American and international copyright. It was the work’s deferred publication date that posed the threat of its being appropriated and that provoked D. Appleton’s elaborate defence, and so other posthumously published memoirs, planned far in advance of their subject’s passing, may be a good place to look for such occurrences. The French-language manuscript (which is presumed to be lost) as re-written by Georges Bernard for Plon-Nourrit, would have been a bibliographical oddity had it been published. Hard to classify as a translation or an adaptation of Fleury and Stanton’s work or as a discrete work, it would have resembled something in between, more like a second original. Further studies such as this one may shed more light on the intricately connected transatlantic and international networks by which books crossed borders and were adapted for new readerships. The mediating activities of literary middlemen (and women) like Stanton – editors, publisher’s representatives, literary agents, and so on – have a unique capacity to illustrate how these complex print networks functioned. Problems of copyright, translation, and re-translation, inherent in international book networks, were central to Stanton’s operations. In fact, they were his stock in trade.

Parties annexes

Note biographique

Shelley Beal teaches at the Brantford campus of Wilfrid Laurier University and collaborates with Emeritus Professor Andrew Oliver of the University of Toronto in establishing first-edition texts of Balzac’s novels for the new series «Les Éditions de l’originale.›› Among her publications is an article in the Papers of the Bibliographical Society of Canada about the transatlantic press campaign led by Montreal journalists and authors’ societies in France to improve French authors’ rights in North America circa 1906. One of the first cohort of doctoral students in the University of Toronto’s Collaborative Program in Book History and Print Culture, she successfully defended her thesis, « Theodore Stanton: An American Editor, Syndicator, and Literary Agent in Paris, 1880-1920. » in Toronto’s Department of French Studies in 2009.

Notes

-

[1]

Inside Front Flap, Volume i: “Two Volumes. Price $7.50 net. Memoirs of the Empress Eugénie by Comte Fleury. A vividly intimate picture of the most romantic figure of the nineteenth century and a glowing reproduction of the brilliant French court of the Second Empire. These memoirs portray the gorgeousness of court life, the pomp of kingly visitings, the never-ceasing intrigue in diplomatic and royal circles, the scintillating wit of artistic and literary salons, as well as the very human side of a true and loving wife and mother. As hostess to the crowned heads of Europe, an arbiter of the world’s fashions, as the Sultan’s guest of honor, as regent leading in French prison reforms, and as hospital visitor to cholera and small pox patients Eugénie always presents a commanding and a gracious figure. She is the center of a host of illustrious men of the time, Princes, ambassadors, academicians, savants, politicians, stars, artists, and authors thronged the salons of Fontainebleau, Saint Cloud and the old Compiègne palace. There splendid entertainments followed one on the other. With charades, hunting, amateur theatricals, and masked balls the royal household beguiled their time until the fatal day of September 4 when the Second Empire tottered to its fall. D. Appleton and Company. New York; London.”

Inside Front Flap, Volume ii: “Two Volumes. Price $7.50 net. Memoirs of the Empress Eugénie by Comte Fleury. A highly-revealing inside view of the political, military, and diplomatic history of France during the Second Empire containing much that will help to settle the many debated and debatable questions of that period. In how far is the Empress Eugénie responsible for the War of 1870? These memoirs throw much light on the matter. Unofficial conferences are detailed, private papers written by the Emperor are herein made public. The intrigue at the Russian Court leading to the Crimean war, the royal meetings and decisions between Napoléon iii and Francis Joseph after the Austro-Italian war, and France’s difficulties in the Polish political troubles are disclosed. Count Cavour and Prince Metternich play their part in such a fashion as to vividly portray their political character. These memoirs, compiled by an intimate member of the Empress Eugénie’s entourage from statements, documents, and letters of the Empress, from conversations of the Emperor Napoléon i, and from family letters, papers and reminiscences of members of the court of the Second Empire, form a very important addition to the historical literature dealing with this era of French and European history. D. Appleton and Company. New York; London.”

-

[2]

Never intended for distribution, this edition may not have been bound, but deposited in sheets. It is conserved in a modern library binding today. Sears mentions sending ten or twelve “sets” of the English-language galley proofs to Stanton to offer European publishers (TSP, Sears to Stanton 5 Aug. 1908).

-

[3]

An interesting transatlantic cultural transfer occurred in D. Appleton’s choice of colour for the hardcover binding: imperial green, a hue popularized by Eugénie, would have recalled the Second Empire more authentically for readers in France, but royal blue resonated more with American book buyers. I am grateful to Professor Yannick Portebois for pointing this out.

-

[4]

No accent appeared over the upper-case ‘E” in Eugénie’s name in the title. In the text of the book, D. Appleton used the French spelling in lower case, “Eugénie.”

-

[5]

TSP, Plon-Nourrit to Stanton 6 June 1910. Stanton had asked 6,000 francs, but agreed to accept 4,000 and an additional 2,000 francs if the work sold more than 2,000 copies (4,000 volumes).

Bibliographie

- Known Editions of Memoirs of the Empress Eugénie

- Eugénie, Keizerin van Frankrijk. Mijn Gedenkschriften. Leiden: A. W. Sijthoff’s, 1920.

- Fleury, Comte. Memoirs of the Empress Eugénie. Compiled from Statements, Private Documents and Personal Letters of the Empress Eugénie. From Conversations of the Emperor Napoleon iii and from Family Letters and Papers of General Fleury, M. Franceschini Pietri, Prince Victor Napoleon and Other Members of the Court of the Second Empire. New York; London: D. Appleton and Company, 1920.

- Fleury, Graf. Memoiren der Kaiserin Eugénie: Nach Mitteilungen, privaten Urkunden, persönlichen Briefen der Kaiserin, Gesprächen des Kaisers Napoleon iii , nach Familienbriefen und hinterlassenen Papieren von General Fleury, Franceschini Pietri, Prinz Viktor Napoleon und anderen Gliedern der Hofgesellschaft des Zweiten Kaiserreichs. Leipzig: F. A. Brockhaus, 1921.

- Kejsarinnan Eugénies Memoarer. Stockholm: A. Bonnier, 1920.

- Kejserinde Eugénies Memoirer. Copenhagen: Gyldendalske Boghandel, 1920.

- Memoirs of the Empress. New York; London: D. Appleton and Company, 1908.

- A-C: Appleton-Century mss. Manuscripts Department, Lilly Library, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN. http://www.indiana.edu/~liblilly/lilly/mss/html/appleton.html

- TSP: Theodore Stanton Papers. Special Collections and University Archives, Rutgers University Libraries, New Brunswick, NJ. http://www.libraries.rutgers.edu/rul/libs/scua/scua.shtml

- “Book Notes.” Political Science Quarterly [New York] 35, no. 4 (Dec. 1920): 676.

- Claretie, Jules. “La Vie à Paris.” Le Temps [Paris] 7 Jan. 1910: 2.

- “Eugénie Ignores Forged Memoirs.” New York Times 23 Jan. 1910: C4.

- “Eugénie Memoirs Not Hers?” New York Times 8 Jan. 1910: 1.

- “Eugénie’s Unwritten Book,” New York Times 12 Jul. 1909: 6.

- Fleury, Maurice, Comte, ed. Le Carnet historique et littéraire [Paris]. Apr. 1898 - Jun. 1905.

- Hitchcock, Frederick H., ed. The Building of a Book : A Series of Practical Articles Written by Experts in the Various Departments of Book Making and Distributing. New York: Grafton Press, 1906.

- Loliée, Frédéric. La Vie d'une Impératrice: Eugénie de Montijo d'après des mémoires de cour inédits. Paris: F. Juven, 1907.

- “No Memoirs of Eugénie.” New York Times 11 Jul. 1909.

- “Paris Society. Les Mémoires de l’Impératrice Eugénie.” Herald [Paris]: 11 Jan. 1910.

- Pietri, Franceschini. “Mon cher Monsieur Calmette.” Le Temps 8 Jul. 1909.

- Robertson, George Stuart. The Law of Copyright. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1912.

- Stanton, Theodore Weld. Reminiscences of Rosa Bonheur. New York: D. Appleton and Company; London: Andrew Melrose, 1910.

- Beal, Shelley Selina. “Theodore Stanton: An American Editor, Syndicator, and Literary Agent in Paris, 1880-1920.” Doctoral thesis, University of Toronto, Department of French Studies / Collaborative Program in Book History and Print Culture, 2009.

- Bently, L. and M. Kretschmer, eds. Primary Sources on Copyright (1450-1900). Faculty of Law, University of Cambridge. Web. http://www.copyrighthistory.org. 1 Nov. 2010.

- Dictionnaire de biographie française. J. Balteau et al., eds. Paris: Letouzey et Ané, 1933- .

- Feather, John. Publishing, Piracy and Politics: An Historical Study of Copyright in Britain. London: Mansell, 1994.

- Speirs, Dorothy and Yannick Portebois, eds. Mon cher Maître: lettres d'Ernest Vizetelly à Emile Zola 1891-1902. Montreal: Les Presses de l'Université de Montréal, 2002.

- Wolfe, Gerard R. The House of Appleton: The History of a Publishing House and its Relationship to the Cultural, Social, and Political Events That Helped Shape the Destiny of New York City. Metuchen, NJ; London: Scarecrow Press, 1981.

Archival Sources

Selected Primary Sources

Selected Secondary Sources

Liste des figures

Fig. 1

Title page vol. 1 of Memoirs of the Empress (1908)

Fig. 2

Title page vol. 1 of Memoirs of the Empress Eugénie (1920)

Fig. 3

Cloth cover vols. 1 and 2 Memoirs of the Empress Eugenie (1920)

Fig. 4

Cloth cover vol. 1 of the German-language edition

Fig. 5

Title page of the German-language edition

Fig. 6

Paper cover vol. 1 of the Danish-language edition

Fig. 7

Frontispiece and title page vol. 1 of the Danish-language edition

Fig. 8

Paper cover vol. 2 of the Swedish-language edition

Fig. 9

Title page vol. 1 of the Swedish-language edition

Fig. 10

Cloth cover vol. 1 of the Dutch-language edition

Fig. 11

Title page of the Dutch-language edition