Résumés

Abstract

Publishing did not have independents enter self-discourse until the 1960s when media conglomeration created a need to distinguish other publishers from this network of corporate giants. But rather than decimating the independent publishing landscape, the corporate conglomeration of book publishing has opened a space for independent publishers to thrive (Simon and McCarthy, 2009; Schiffrin, 2001; Hawthorne, 2014, 2016; Kogan 2007, 2010), in part because of the social currency that positioning themselves as independent in discourse affords. In order to analyze the use, purpose, and meaning of independent in publisher discourse, this article conducts a content analysis on mission statements of 39 US-based independent publishers. Through content analysis of mission statements, this article illuminates the way that certain publishers construct a particular social function and marketing appeal by the use of independent in twenty-first century book publishing discourse in the US.

Résumé

Il a fallu attendre les années 1960 et l’avènement de grands conglomérats médiatiques pour voir les éditeurs indépendants, soucieux de se distinguer des géants de l’industrie, se « mettre en récit ». Loin de décimer les petits joueurs, ces conglomérats présents dans le monde de l’édition leur ont permis de prospérer (Simon et McCarthy, 2009; Schiffrin, 2001; Hawthorne, 2014; Kogan 2007, 2010), en partie en raison de la valeur symbolique que confère le fait de se présenter comme indépendants. Que veut dire « indépendant », quel but le recours à ce concept sert-il dans le discours que tient l’éditeur sur sa pratique? C’est sous cet angle que nous analysons l’énoncé de mission de 39 maisons d’édition indépendantes ayant leur siège aux États-Unis. Ce qui en ressort, c’est qu’en soulignant, dans leur discours, leur « indépendance », certains éditeurs actuels arrivent à se doter d’un attrait commercial et d’une fonction sociale particulière.

Corps de l’article

This article examines the use of independent in publisher discourse for English language publishers in the United States. There are many reasons why this term is a fascinating one, not least because of its prominent use despite its lack of one unified definition. As a by-product of late twentieth-century conglomeration, the term independent as used by publishers in constructing discourse about themselves is therefore a window into not only how certain publishers perceive their roles in the cultural and economic space,[1] but also in how they would like to be perceived by readers, authors, and others in the publishing industry. McCleery argues that the publisher is often seen as “an obstacle to the unfettered communication of author with reader, forcing compromise on the author’s sense of artistic integrity to maximize revenue from the reader.”[2] Because the publisher is so often portrayed as an obstacle to be overcome in an author’s effort to reach readers, the use of independent in publisher discourse illustrates a more personal, author-friendly and editorially-focused narrative around what a publisher is and can be.

A Space for Independents

The term independent was not used to describe publishing companies until the late twentieth century when the landscape of book publishing company ownership, size, approaches, and philosophies began to change from the plurality of independent publishing firms by which the industry was characterized.[3] No longer an industry solely comprised of family-owned and family-run businesses, the book publishing industry was on its path to full-force multi-media conglomeration and consolidation by the 1960s.[4] This multi-media conglomeration and consolidation necessitated a way to linguistically differentiate between the new mega publishing empires on one end of the spectrum and the small, independently owned and operated presses at the other end. It was from this environment that the term independent publisher or independent press sprung, to stand in stark contrast to the new kind of publishing company that was quickly dominating the publishing landscape in terms of market share and revenue. This situation was prompted initially by Random House’s absorption of Alfred Knopf in the 1960s and then evidenced even in the last few years in mergers such as the 2014 HarperCollins acquisition of Harlequin and the Hachette acquisition of the largest independent publishing group: Perseus Books Group.[5]

Evidence of the increased use of independent in book publishing can be found in the number of prominent publisher organizations that have incorporated independent into their titles in recent years. Although the Independent Book Publishers Association (IBPA) has existed in earlier forms and names since 1983, it has only had the word independent in its official title since 2008.[6] The Bay Area Independent Publishers Association was also established originally under another name, the Marin Small Publishers Association, in 1979, and then changed name to include the term independent later.[7] Other publishing organizations that utilize the term independent in the United States include the Midwest Independent Publishers Association (founded in 1984), the Colorado Independent Publishers Association (founded in 1992), the Greater New York Independent Publishers Association, and the Independent Publishers of New England.[8]

In this industry dominated by a network of corporate giants, it is, in some ways, surprising that independent publishers continued to exist at all; rather than eliminate the independent publishing landscape, corporate conglomeration of book publishing actually opened a space for independent publishers to thrive.[9] In this space, independent publishers fill a gap and territory that conglomerates are unable to occupy. This gap is characterized by a particular public perception and image, an image of a publisher that is editorially driven, locally rooted, author friendly, diversity focused, relationship based, quality concerned, and community building.

Furthermore, the use of independent to describe a company is not unique to publishing. Independent bookstores,[10] magazines,[11] television,[12] music,[13] and other companies (especially within the creative industries) have made this distinction, many of these movements emerging from the late twentieth century when the democratization of production meant that independents could thrive but also when multimedia conglomeration was forcing the same precise terminology distinctions in these other areas of the creative industries as it was in publishing.[14] Therefore, it is essential to contextualize the independent discourse in book publishing within the anti-corporate and “buy local” movements from which it was born and influenced.[15] In many of these other areas of the creative industries, independent has been used synonymously with alternative and although this has not been the case in publishing, it is possible to see the radical nature that is often associated with this term independent as still permeating perception and use of the word in a publishing context.

The prominent rise of independent has been not only a way to distinguish a company from one owned by a multi-media conglomerate but also a charged term with a particular marketing aesthetic. Simon, McCarthy, and Hall argue that at the very end of the twentieth century and beginning of the twenty-first century, the term independent would have seemed “quaint,” whereas independent has so dominated the publisher conversation in the last two decades that in many ways “corporate” sounds equally quaint in the current environment. As these authors go on to posit, “In the unending dialectical spiral, at the very moment when complete corporate control is all but achieved, its antithesis benefits and thrives, and there comes a new awareness of mutuality.”[16] While, increasingly, book publishers discuss themselves and position themselves by using terms like independent, the term is not without its ambiguity and limitations, in part because there is not an agreed upon definition for independent as it relates to publishing.

Defining Independent

Miller suggests three typical definitions of independent when referring to a publishing company. The first definition of independent is understood in terms of economic autonomy;[17] in other words, independent publishers are not owned by conglomerates. The second definition is in reference to size; independent publisher is often used synonymously with small publisher. And the third definition of independent in a publishing company context is a publisher that is guided by a particular philosophy, a philosophy focused on editorial quality, local communities, and author relationships. It is worth noting that these three definitions are often, in fact, interconnected and overlapping.

This first definition, a publishing company with economic autonomy, is perhaps the most prominent and commonly accepted definition. Given the market share prominence of the largest five publishing entities and the way that multimedia multinational conglomerates have changed the publishing landscape in the last 50 years, it is little wonder that differentiating from the “Big 5”[18] would be one of the primary roles of this term. However, economic autonomy is not as straightforward as it might initially seem. Imprints, both of the Big 5 and of other larger corporations, are given various levels of autonomy depending on the parent company,[19] which calls into question the lack of terminology to represent these differences in company ownership.

Second, independent publisher is often used synonymously with small publisher. This is not only true of publishers in their discourse regarding themselves, but also in the way that other industry professionals and academics use the term independent publisher. For example, publishing scholars Mark Davis and Emmett Stinson use “small and independent” as a set pair used together to describe a particular type of publisher that also espouses a specific philosophy and list.[20] Similarly, Melanie Ramdarshan Bold in her analysis of small press publishing in the Pacific Northwest uses “small press” and “independent publisher” interchangeably. However, at other points in the article, small is used as a subset of independent, such as in the statement that “independent publishers, especially the smaller presses, are often run for the love of the product rather than for profit, and their output is guided by taste rather than consumer insight and sales data.”[21] This statement from Ramdarshan Bold also blurs into the third use of independent, which connotes a specific philosophy. Small and independent are so commonly used together, or used interchangeably, because they are both terms for publishers that usually occupy that realm of non-conglomerate space in the industry. However, there are a few problematic aspects to this interchangeable usage, including the slippery modes of measuring and defining small company in the publishing industry. The Small Business Administration in the US defines a small publishing company in terms of employees, with any companies with fewer than 1,000 employees being categorized as “small.”[22] In this sense, almost any company that is not one of the Big 5 would count as small, particularly because of the increasing move in the industry to utilize freelancers rather than increase full-time, salaried employees,[23] in part because of shifts in publishing houses from “a cohesive corporate structure” to “a more fragmented and atomized work culture.”[24] This is quite different from how John Thompson defines publisher size for trade publishers, in which he classifies publishers by annual revenue, with $20 million to $500 million classifying as medium, and below $20 million as small.[25] In her study of small, independent presses in the Pacific Northwest, Ramdarshan Bold’s sample of small publishers are all companies with five or fewer employees.[26] Other scholars utilize the definition of small to medium enterprises (SMEs) set forth by the European Commission, using number of employees to indicate size, but in a more manageable and segmented way than the Small Business Administration does. In the European Commission definition, fewer than 10 employees is a micro press, fewer than 50 employees is a small press, and fewer than 200 employees is a medium press.[27] In any case, these competing definitions demonstrate the difficulty in assessing publisher size that is compounded by the fluid use of independent to mean small, particularly when some of the most prominent independent publishers who use such language in their own discourse and branding, such as Sourcebooks,[28] are at least solidly medium-sized according to many of these ways of measuring.

Third, independent publisher is often used to indicate a particular philosophy. Many scholars have argued that the philosophy of independent publishers, particularly their emphasis on creative autonomy, has been what has allowed them to continue to succeed and carve out a space in the publishing industry landscape. Davis notes that the independent publishing boom is in part due to independent publishers’ desire for readers, a desire “that isn’t canvassed in the market-centric publishing strategies of the majors.”[29] Likewise, Ramdarshan Bold’s study of independent publishing in the Pacific Northwest emphasized the belief of these publishers that they can “help to promote and preserve regional cultures and identities and maintain diversity in cultural output.”[30] Miller notes that the perception of independent publishing is that it is more editorially driven, locally rooted, and author friendly. Additionally, key to the independent publishing concept and brand are personalizing the author-publisher relationship and diversifying the publishing landscape, much like we see with the independent movement for booksellers.[31] While the use of such terminology is as much a marketing and branding tool as it is an accurate portrayal of independent publishers’ philosophies, there is some evidence to back up the cultural claim that independent publishers cling to. Emmett Stinson notes that in the Australian context particularly, the mediation of literary works is dominated by “small and independent” publishers, evidenced by the Auslit database which shows that “single-author collections of short fiction, with a few notable exceptions, are almost entirely produced by small publishers, and no large publisher has produced new poetry collections with any regularity since the 1990s.”[32] Therefore, to see certain genres and categories of books produced almost exclusively by small (and Stinson uses this term as a pair with independent) publishers substantiates claims that cultural capital is of more interest and currency to independent publishers than it is to corporates, at least in certain contexts.

To further complicate the usage of independent publisher and independent publishing, in addition to these three most common utilizations of these terms, the shortened indie publisher has also entered contemporary publishing discourse, primarily as a less stigmatized way of referring to self-publishing, or to authors who produces books themselves rather than through a publisher. It has been noted that not all traditional independent publishers are happy with the appropriation of indie publisher or indie author to mean self-published.[33] In many ways, the term indie is very applicable to self-published authors because of the autonomy (or perceived autonomy) that self-publishing affords. This then begs the question: do indie authors actually have more autonomy? While creative control is often important to authors, self-publishing in the current environment means being at the whim of companies like Amazon. Also, other scholars have suggested other uses of independent, including Sophie Noël’s use of independent to mean “politically independent.”[34] In fact, the “anti-authoritarian spirit” fueled prominent publisher/bookseller City Lights, and as Emblidge observed, the anarchist beginnings and spirit has been a part of City Lights, even as it has evolved over the years.[35] Additionally, this political and activist independence was what characterized feminist independent publishers at the height of feminist movements in the 1970s and 1980s. These publishers, like the Feminist Press (founded in 1970) and Cleis Press (founded in 1980) had political independence as part of their brands right from the start, although feminist publishing did not reach the mainstream in the same way in the US that it did in the UK.[36]

With these three primary uses of independent publisher, in addition to the confusing adage of indie publishing as describing a different kind of publishing model, there is little consistency in the use and meaning of independent publisher. Furthermore, one has to wonder if lacking an agreed upon definition of independent publisher makes the term lose meaning, because, in a way, it is a term that can mean whatever the user wants it to mean.

Social Capital and Autonomy

Underlying these various definitions of independent are two key theoretical concepts—social capital and autonomy—that were particularly championed by Pierre Bourdieu. Robert Putnam and John Field have also been influential scholars on the nature of social capital. The particular levels of social capital and high autonomy (or perceived autonomy) available to publishers become key characteristics of independent publishers.

From a Marxian understanding of capital, “capital is intimately associated with the production and exchange of commodities” and capital is also “intrinsically a social notion.”[37] Building upon Marxian and Durkheimian definitions and appropriations of capital, Bourdieu defines social capital as

the aggregate of the actual or potential resources which are linked to possession of a durable network of more or less institutionalized relationships of mutual acquaintance and recognition—in other words, to membership in a group—which provides each of its members with the backing of the collectively-owned capital, a ‘credential’ which entitles them to credit, in the various sense of the word.[38]

Levels of social capital possessed by a particular agent or organization, in Bourdieu’s explanation, are dependent on two things: the size of the network of connections and the levels of other types of capital (economic, cultural, and symbolic) that those connections in the network possess. As Schuller, Baron, and Field point out, Bourdieu often uses social capital as “a general metaphor for power or social advantage.”[39] Robert Putnam defines social capital as including three features of social life: networks, norms, and trust.[40] It is from Putnam’s definition that even across the diverse multi-disciplinary social capital literature, the two key and frequently discussed components of social capital in the literature are trust and networks.[41]

Social capital’s volume and value to independent publishers is evident in what Thompson calls the “economy of favours.” Social capital for large conglomerate publishers lies in part with the publishers’ ability to consolidate and negotiate with members of their social networks based on their capability to deal with processes and products in large, highly scaled quantities. However, for small, independent publishers, the economy of favours means that

small presses commonly share knowledge, expertise and contacts with one another. They see themselves as part of a common vocation and shared mission. Their competitive rivalries are overshadowed by the affinities that stem from their common sense of purpose, their shared understanding of the difficulties faced by small publishers and their collective opposition to the world of the big corporate houses.[42]

This translates into lower rates from freelancers, additional goodwill and promotional opportunities from retailers (particularly independent bookshops), and trust and investment from consumers who are willing to pay higher prices for books because of the perceived mission of the independent presses that published them.

In addition to social capital, autonomy is another important concept key to a discussion of independent publishers. Being economically autonomous is the oft turned to definition of independent as it applies to publishers, but autonomy is also at the center of what it means to be a small company and of the philosophy that many independent publishers espouse. Bourdieu’s continuum of small-scale to large-scale production is inextricably linked to the level of autonomy that the producer has (or not) from what Bourdieu calls the “field of power.” Small-scale production has the greatest amount of autonomy from the field of power in publishing, in Bourdieu’s view, whereas large-scale production has the least autonomy from the field of power. Hesmondhalgh, in discussing the changes in the cultural industries in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, asserted that as more small companies emerged, they were perceived as “sites of creative independence,” in part a reaction to the growing anxieties about bureaucratic organizations dominating cultural production.[43]

However, there are admittedly limitations in applying Bourdieu’s concepts to cultural production in the twenty-first century. Hesmondhalgh notes that these limitations include Bourdieu’s very little material about large-scale cultural production and the dominance of multimedia entertainment corporations across the cultural industries, beyond the brief assertion that large-scale production responds to “pre-existing demand and in pre-established forms.”[44] In this environment, there is more differentiation, fluidity, and complexity in the concepts of large-scale production and autonomy than Bourdieu suggests. Additionally, “prestige and popularity are not necessarily so much in contradiction as in Bourdieu’s schema” due to the “ability of large-scale production to disseminate consecrated culture.”[45]

Content Analysis of Mission Statements

In order to analyze the use, purpose, and meaning of independent in publisher discourse, content analysis research was conducted on the mission statements of 39 North-America-based (and primarily US-based) independent publishers. Content analysis of mission statements was chosen as the method here because of the wide reach to various stakeholders—consumers, distributors, agents, authors, etc.—that a website mission statement affords. While other paratextual materials of publisher discourse such as advertising pieces, book jacket copy, and website book blurbs can demonstrate discourse from publisher to reader, the website mission statement allows a wider audience scope for the publishers’ discourse about themselves, which in turn can affect the nature of that discourse.

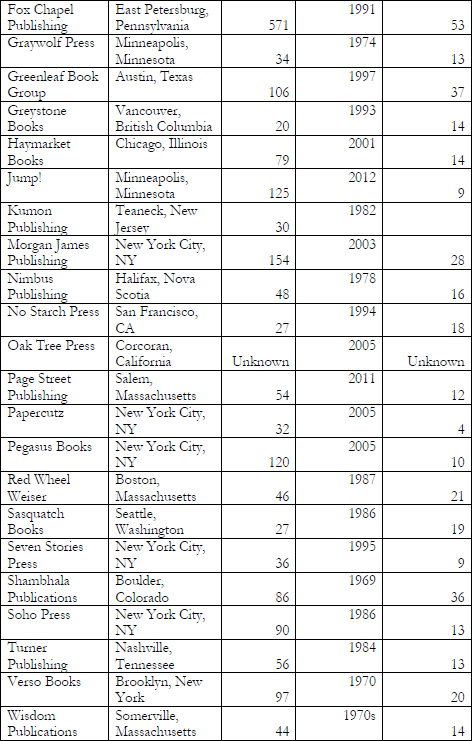

These publishers are identified from fast-growing independent publisher lists from Publishers Weekly and from overall top-selling publisher lists and report. This list of fast-growing independent publishers was used for several reasons. The list focused on primarily US-based presses and was curated by the top publishing trade news body in the US: Publishers Weekly. Additionally, due to the lack of universal agreement of the definition of independent publisher, using other methods to identify publishers who are “independent” would rely on a commitment to one type of definition, rather than, in this case, allowing the Publishers Weekly identified “independent” to inform the sample. However, there are limitations to this sample choice that must be acknowledged. Because these independent publishers are “fast-growing,” they may not be representative of English language US-based publishers as a whole because, as Bourdieu has identified, small-scale cultural production tends to also be lacking in economic capital.[46] But as Hesmondhalgh has acknowledged, there is more nuance and complexity with large-scale production that Bourdieu recognizes in his work; likewise, other scholars, like David Throsby, have asserted that there is more interconnection between economic capital and other types of capital than has been previously asserted.[47]

A mission statement establishes who the publisher is, what the publisher does, and where the company is headed.[48] Additionally, the mission statement serves as a marketing and public relations tool.[49] Through content analysis of mission statements, this article illuminates the way that certain publishers construct a particular social function and marketing appeal by the use of independent in twenty-first century book publishing discourse in the US. The American Marketing Association defines a mission statement as “an expression of a company's history, managerial preferences, environmental concerns, available resources, and distinctive competencies to serve selected publics. It is used to guide the company’s decision making and strategic planning.”[50] However, in addition to a mission statement being a strategic planning and decision-making guide for a company,[51] a mission statement is also “decidedly persuasive,” frequently available on corporate websites,[52] emotionally bonding within the company,[53] indicative of the company’s self-identity,[54] and overall serves as a communicative tool to employees, stakeholders, and the general public.[55] The outward-facing, customer-persuading nature of mission statements is something that several scholars explore, including M. David et al.[56] In short, mission statements are rhetorically designed, largely removed from day-to-day activities of the company, and strategic in “creating allegiance and inspiring commitment within and to a constructed discourse community.”[57] The use of the term “mission statement” in this article is not a reference to a strategic marketing document, which, because of the typically low strategy applied from small publishers,[58] are only produced by medium and large publishing companies. Instead, mission statements in this context are positioning statements available on publisher websites.

Previous research on mission statements has been focused primarily on assessing the financial impact of mission statements,[59] accuracy of mission statements,[60] transnational comparisons,[61] and school or university mission statements.[62] Book publisher mission statements have not previously been the object of study and a lens through which to capture publisher discourse and self-identity. Williams sees four categories of mission statement scholarship: recommendations for its content, assessments of financial performance and mission statement effectiveness, the rhetorical nature of the mission statement, and the mission statement as a corporate culture creation strategy.[63]

Content analysis is a common method of examining mission statements, as evidenced by the many studies that use content analysis for mission statements.[64] Through content analysis, thematic patterns from a particular text (in this case, mission statements) are identified. This is a qualitative method of analysis in which the patterns emerge through close reading of the text.[65] It is content analysis that this article utilizes to recognize the patterns of discourse surrounding the use (or non-use) of independent in mission statements.

Much like other promotional genres,[66] mission statements generally follow particular linguistic structures, share a communicative and rhetorical purpose, and utilize specific terminology. However, the structure of mission statements is not the focus of this article; rather, the structure of the mission statement genre is a framework upon which independent publishers build rhetorical discourse that positions themselves in particular ways. It is this discourse and positioning with which this article is focused. In any case, mission statements offer a window into the world of the publisher and the tensions between publisher types: large vs. small, independent vs. corporate, etc.

The mission statements on the 39 publishers’ websites were primarily found on the Home or About pages. These mission statements were copied from the publishers’ websites into a word processing document, where they were thematically coded using the comment feature to highlight and summarize at the sentence and paragraph level. These comments were then compiled into another document and were lumped into categories based on their similarity in themes. Therefore, the meta-themes that emerged were size, passion, relationships, quality, diversity, location and community, environment, social/political responsibility, disadvantages, cultural capital, social capital, and curation. In addition to the thematic coding of the mission statements, a list was also made of the particular collocates of independent when used by publishers in their mission statements, and this list of collocates was also compared and categorized according to similar terms and themes. Finally, the website mission/positioning statements of the Big 5 publishers—Penguin Random House, Simon and Schuster, Macmillan, Hachette, and HarperCollins—were also examined, particularly to see if independent was utilized in that discourse. The results of this content analysis are detailed in the discussion and findings below.

The Value of Being Independent

Twenty-one of the 39 publishers’ mission statements used independent, even though this group of publishers, identified by Publishers Weekly as being the fastest growing independent publishers in the US and Canada, could feasibly all have equal claim to this term. Thus, this situation suggests that, more so than other terms that carry certain legal specifications, independent as a term in the publishing context is a rhetorical choice. In other words, publishers who choose to incorporate independent into their mission statements do so purposefully. Yet the term is not so ubiquitously defined and imbued with social capital as to be used by any publisher who could feasibly be classified—in whatever loose terminology is used—as independent.

The first two commonly accepted definitions of being an independent publisher—not being owned by a conglomerate (the Big 5) and being small—came through in the publisher mission statement discourse. Thirty-three publishers were not owned by other companies, but six of the publishers were. Interestingly, one of the six publishers that utilized independent in its mission statement but is owned by the largest publishing conglomerate of the Big 5, Penguin Random House, was Seattle-based Sasquatch Books. Sasquatch Books establishes itself as “one of the country’s leading independent presses” with a mission to “seek out and work with the most gifted writers, chefs, naturalists, artists, and thought leaders in the Pacific Northwest and bring their talents to a national audience.”[67] While the acquisition of Sasquatch Books by Penguin Random House is rather recent,[68] the continuing use of independent in their mission statement illustrates not only the integral nature of independent in Sasquatch Books’s brand but also in the symbolic capital that independent provides and is difficult to relinquish. Additionally, (although they may not be owned by the Big 5), 12 of the 39 publishers are distributed by the Big 5. This begs the question, does being distributed by the Big 5 really allow for independence and autonomy from corporates? Especially because of the ease and low-capital nature of entry as a publisher into the industry, more and more it is distributors who are becoming key gatekeepers in the process of books reaching readers.[69] In this environment, one has to wonder if being distributed by the Big 5 allows some of that corporate influence from under which independent publishers seem so eager to remove themselves. Also, 21 of the 39 publishers whose mission statements were analyzed for this article have their own imprints. Again, this begins to complicate the idea of independent ownership. Typically, imprints are created in two ways: either by acquiring another company that becomes an imprint of the parent company or by creating an official “imprint” to distinguish between distinctly different lists, but with no real financial, staff, or ownership changes. Surprisingly, two of the Big 5 publishers, Penguin Random House and Macmillan, use independent in their mission statements to define themselves as having imprints that are “editorially and creatively independent”[70] and being a collection of independent publishers.[71]

As this article demonstrated earlier, the measuring of company size is a muddy area, but if we take into account Thompson’s definitions of size,[72] the European Commission’s definition of size[73] and the Small Business Administration’s definition of size,[74] because 36 of the 39 companies had fewer than 50 employees and because 30 of the 39 companies had revenues under 10 million, by all three definitions of company size in publishing, the majority of these independent publishers could also be classified as small publishers.[75]

However, when it comes to a particular philosophy as being key to the third definition of independent publisher, these mission statements reflect specific patterns. The common philosophy themes that emerged from the mission statements are location and local community, diversity, relationships, and the role of the independent publisher as “partners” with authors and readers (thus democratizing the gatekeeping process) rather than literary authorities and tastemakers.

Locality

Independent publishers emphasize location and local community. Fifteen of the 39 publishers specifically mentioned their locations in their mission statements, evidence that independent publishers want to be seen as, or see themselves as, serving local communities. Unlike the Big 5 who not only have offices and partnerships across the world but who also are all headquartered in the United States’ publishing hub in New York City, this focus on location reveals that only two of the publishers who included location in their mission statements were based in New York City. The others are scattered across the United States and Canada. Though this was a pattern across the mission statements as a whole, Chelsea Green, which “keeps its roots based firmly in Vermont,” emphasized locality even more than most in its mission statement discourse, stressing the mission to “participate in the restoration of healthy local communities,” publish books about local food, and donate money annually to assist “local environmental causes.”[76] Other publishers use locality to demonstrate an awareness of diverse local populations and indigenous peoples, such as in Greystone Books’s mission statement, which acknowledges that their office is located on land of the “Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil-Waututh peoples.”[77] Not only do publishers acknowledge the state or city in which they are located, but sometimes, they even refer to the particular streets. For example, Sasquatch Books tells website visitors that the company is “located in downtown Seattle, just blocks from Pike Place Market and Elliott Bay.”[78] Shambhala Publications goes a step further in inviting local residents to visit the office: “If you are in the neighborhood, please stop by and say hello—we have all of our books in our bookstore for you to peruse.”[79]

Diversity

Independent publishers pride themselves on contributing to diversity in the literary ecosystem. Publishers use terms like “debut authors,” “fresh voices” and “diversity” to emphasize a representation of creative people and projects that would be otherwise overlooked by non-independent publishers. Despite the current movement and reflection of lack of diversity in publishing, particularly children’s publishing at the moment (as evidenced in We Need Diverse Books, among others), there is not sufficient evidence to show that independent publishers actually publish authors that are more diverse in terms of gender, sexuality, race, religion, language and other categories. A few of the Big 5 have made efforts to address the lack of diversity problem, particularly in children’s publishing, through the creation of new imprints, including Simon and Schuster’s new imprint Salaam Reads, which emphasizes children’s books focused on Muslim characters and stories[80] and Penguin Random House’s newly launched Kokila for diverse books for young readers.[81] More than anything, this underlying philosophy of supporting diversity is more about supporting materials and authors that do not or would not otherwise make it through Big 5 gatekeepers than it is about a specific effort to increase diversity within the publishing industry as a whole, although there certainly are independent publishers who are specifically diversity-focused. Page Street Publishing asserts in their mission statement that finding writers who create “diverse characters” is their primary goal.[82] Graywolf Press says they champion “diverse voices . . . in a crowded marketplace.”[83] Jump! “strives for diversity and inclusion, showing people in our books at every age, from all ethnicities, and with varying abilities.”[84] Translation publisher Europa editions see their diversity role as bringing “fresh international voices” into Anglophone markets.[85] Likewise, Diversion Books “is committed to the discovery of new voices.”[86]

Relationships

Independent publishers portray themselves as being more invested in personal relationships with readers and authors. In marketing theory and practice, relationships are increasingly at the centre of marketing activities—rather than traditional paradigms like the 4Ps[87]—particularly for small companies.[88] Therefore, the connection between small publishers and independent publishers yields an unsurprising emphasis on a personal touch, a greater value on relationships with readers and authors. For Familius, the developed relationships with customers and authors is key to the way that the publisher operates.[89] Chelsea Green Publishing emphasizes cultivating “collaborative, respectful relationships with authors and readers.”[90] Hybrid publisher Brown Books Publishing Group went even as far as to trademark “relationship publishing” and call this term the cornerstone of its process.[91] It is worth noting that three of the independent publishers in this list of 39 are hybrid publishers (Morgan James Publishing, Greenleaf Book Group, and Brown Books Publishing Group) as defined by the Independent Book Publishers Association,[92] in that they span the boundary between self-publishing and traditional publishing, as authors are asked to financially support the production of the book. Greenleaf Book Group and Brown Books Publishing Group used the term independent in their mission statements, while Morgan James Publishing did not. Thus, the focus on relationships is not only a tie between independents and small companies but also a blurring of the self-publisher and traditional-publisher lines in some cases.

Collaboration

Independent publishers seek to democratize the gatekeeping process by branding themselves as partners with authors and readers, rather than literary authorities and tastemakers. Related to the focus on relationships discussed in the previous paragraph, this “partnership” between authors and publishers is stressed in the mission statements for these independent publishing companies. For example, Diversion tries to establish both “creative and collaborative partnerships with authors,”[93] while BenBella Books aims to attract authors “who value personal attention, a partnership philosophy,” stressing that key to this is the understanding that “publishing is a partnership between author and publisher.”[94] In speaking directly to authors in their mission statement, hybrid publisher Greenleaf Book Group say, “We can partner with you on every aspect of developing and promoting your big idea.”[95]

Emotion

Independent publishers emphasize emotion over automation. In the current publishing environment—which has been called the post-digital age of publishing[96] or the late age of print[97]—the emotional artform of editorial judgement and intuition exists alongside algorithmic selection.[98] While, in the twenty-first century, both the intuitive curation and big-data-driven selection are part of publishing processes, the mission statements of this sample of independent publishers reveals the emphasis of independent publishers on the emotional side of the publishing business. The most common collocates of independent are passionate, warlike, and authoritative terms such as completely, stanchly, fiercely, radically, diversified, and leading. Cottage Door Press asserted that their press was built “through hard work, dedication, and love.”[99] Page Street Publishing proclaim themselves passionate publishers: “As publishers, we, too, are passionate.”[100] BenBella Books advises all to “publish with passion” and state that “passion cannot be created or marketed into a book.” This passion “only emerges as the result of an author delighting, entertaining, illuminating, or educating in a way that resonates with the reader.” One particularly interesting thing about BenBella’s focus on passion as being central to the way the business is run is that their mission statement assures that this focused passion does not seek to put BenBella on a gatekeeping, curating, or tastemaking pedestal: “But we aren’t snobs,” the mission statement claims; “just because a book is intelligent doesn’t mean it can’t also be fun.”[101]

As these examples and this content analysis have shown, location, diversity, relationships, partnership, and emotion are central to the mission statements of independent publishers. However, in examining “independent” as a positioning and branding tool, it is prudent to ask: Are these claims true? Are independent publishers really more focused on relationships, diversity, and local communities than corporate giants are? Understanding that mission statements are rhetorical and communicative pieces that reveal how publishers would like to be portrayed (and not necessarily reflect what they are), we should reflect on the accuracy of these mission statements in an effort to better understand independent in publisher discourse.

In terms of independent vs corporate, it may be more productive to think of these terms on a continuum, rather than an all or nothing. Independent has been used as a catch-all term to describe, for the most part, publishers not owned by conglomerates, but this leaves the corporate publishers as one category, without distinguishing the differences in autonomy and independence that exist in the corporate-imprint relationship within the Big 5. Again, Thompson attests to the variability in the way that different corporations and their imprints operate: “The world of corporate publishing is, in practice, a plurality of worlds, each operating in its own way.”[102]

In terms of location and local community, the publishing of local authors and involvement in the local literary community might not be as important to independent publishers (particularly in contrast to corporate publishers) as it seems. To be certain, the inclusion of office location reveals an emphasis on location in the mission statement discourse, but examples like the PubWest Best Practices Survey Research Report, which analyzed survey data from primarily small-to-medium-sized (and often independent) members of the trade publishing organization PubWest, tell a different story. Despite there being a section of questions devoted to community involvement, the data revealed that the emphasis on locality and local authors was not “a major factor” and that for most of these publishers, “publishing local authors was present, but not a particular emphasis, and it was difficult to ascertain whether the presence of examples of local authors was indicative of the list as a whole without more contextual information.”[103]

In terms of diversity, there is not clear data to support the claim that independent publishers are more diverse than conglomerates. Noël staunchly disagrees with the claim that “alternative authors and ideas . . . would not find their place in conglomerates,” saying that “such an assertion is obviously controversial as associating ‘easy’ books with large companies and serious ones with independent publishers is an oversimplified statement.”[104] To the claim that large corporate publishers are not interested in publishing debut authors, Thompson asserts that “nothing could be further from the truth” and argues instead that large corporate publishers are willing to gamble on debut authors with “reckless abandon.”[105]

Additionally, we see terms like independent and small being used as positively charged vocabulary juxtaposed with the negatively charged, unfeeling connotations that accompany corporate and large when referring to companies. But as Simon, McCarthy, and Hall point out, the assumption that “smallness or independence are better, or worse, than largeness or ‘corporateness’” is an oversimplification. As these authors reveal,

the more interesting observation may be to note all the ways in which largeness as a corporate quality can be unimpressive or ineffectual, and all the ways in which, in today’s publishing world, smallness sometimes goes with other necessary characteristics of good publishing, like careful title selection, painstaking editing, and strong advocacy for writers’ voices.[106]

In short, there is data to support that independent publishers are not as different from their corporate counterparts as they desire to portray themselves. However, because of the positive connotations of being small, economically autonomous, local, relationship focused, and supporting of underrepresented and local authors, independent becomes a staple in publisher discourse to differentiate themselves and their product offerings from the corporate publishers that dominate market share in the industry.

Conclusion

From the analysis of the use, purpose, and meaning of independent in publisher discourse, as evidenced by the 39 independent publisher mission statements, it is clear that a particular philosophy is central to the social and cultural currency that the term independent provides. This philosophy emphasizes locality, diversity, relationships, partnering, and emotion. Most of the 39 publishers that were examined also fit into the other two commonly accepted definitions of independent publisher: they were small in size and economically autonomous by most measures. However, the frequency of distribution of these independent companies by corporate companies, namely the Big 5, calls this autonomy into question.

Why would locality, diversity, relationships, partnering, and emotion be desirable qualities for a publisher in the twenty-first century? Social capital—as evidenced through the economy of favours for independent publishers—and autonomy are central to this answer. The return to personal care, author-friendly approaches, and editorially driven emphasis heralds back to a time in publishing before independent publisher was a commonly used term, a time when independents dominated the publishing industry landscape because family-run and family-owned was the norm. Therefore, the term independent brands non-corporate (and often small) publishers with a particular philosophy that speaks to contemporary reader and author fears that stem from a situation where a select few giants hold the dissemination of literature, knowledge, and culture and in which the gatekeepers and curators have a powerful position. Perhaps publisher discourse related to the term independent reveals more about reader and author interests, concerns, and desires than it does about the actual innerworkings and business administration of independent publishers.

Parties annexes

Appendix

Table 1

Research Sample of Independent Publishers

Biographical note

Rachel Noorda is Director of the Book Publishing Master’s program at Portland State University. She has a PhD in Publishing Studies from the University of Stirling. Her research interests include twenty-first century book culture, diaspora communities, Scottish publishing, small business marketing, international marketing, and entrepreneurship. Rachel has been published in Publishing Research Quarterly, Quaerendo, National Identities and TXT, and has forthcoming publications in The Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America, Handbook of Marketing and Entrepreneurship, and Book History.

Notes

-

[1]

Sophie Noël, “Keeping Neoliberal Economic Principles at a Distance,” Global Management, Local Resistances: Theoretical Discussion and Empirical Case Studies 129 (2015): 220–37.

-

[2]

Alastair McCleery, “The Return of the Publisher to Book History: The Case of Allen Lane,” Book History 5, no. 1 (2002): 163.

-

[3]

John Thompson, Merchants of Culture: The Publishing Business in the Twenty-First Century 2nd edition (New York City: Plume, 2012).

-

[4]

Evan Brier, “The Editor as Hero: The Novel, the Media Conglomerate, and the Editorial Critique,” American Literary History 30, no. 1 (2018): 85–107.

-

[5]

Melanie Ramdarshan Bold, “An Accidental Profession: Small Press Publishing in the Pacific Northwest,” Publishing Research Quarterly 32, no. 2 (2016): 87.

-

[6]

Independent Book Publishers Association website, “Our History,” https://www.ibpa-online.org/page/history.

-

[7]

Bay Area Independent Publishers Association website, “About Us,” https://www.baipa.org/baipa/.

-

[8]

Independent Book Publishers Association website, “Affiliate Associations,” https://www.ibpa-online.org/page/affiliates.

-

[9]

Dan Simon, Tom McCarthy and David Hall, “Editorial Vision and the Role of the Independent Publisher,” A History of the Book in America 5 (2009): 210–22; André Schiffrin, The Business of Books: How International Conglomerates Took Over Publishing and Changed the Way We Read (London: Verso, 2001); Susan Hawthorne, Bibliodiversity: A Manifesto for Independent Publishing (North Geelong: Spinfex Press: 2014).

-

[10]

Laura Miller, Reluctant Capitalists: Bookselling and the Culture of Consumption (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006).

-

[11]

Megan Le Masurier, “Independent Magazines and the Rejuvenation of Print,” International Journal of Cultural Studies 15, no. 4 (2012): 383–98.

-

[12]

David Hesmondhalgh, The Cultural Industries (London: Sage, 2013).

-

[13]

Patryk Galuszka and Blanka Brzozowska, “Early Career Artists and the Exchange of Gifts on a Crowdfunding Platform,” Continuum 30, no. 6 (2016): 744–53.

-

[14]

Daniel Hallin, “Neoliberalism, Social Movements and Change in Media Systems in the Late Twentieth Century,” The Media and Social Theory (Abingdon-on-Thames: Routledge, 2008): 57–72.

-

[15]

Michael Shuman, The Small-Mart Revolution: How Local Businesses Are Beating the Global Competition (Berrett-Koehler, 2007); David Hess, Localist Movements in a Global Economy: Sustainability, Justice, and Urban Development in the United States (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2009).

-

[16]

Simon, McCarthy and Hall, “Editorial Vision,” 211.

-

[17]

Miller, Reluctant Capitalists.

-

[18]

Penguin Random House, HarperCollins, Hachette, Macmillan, and Simon and Schuster are commonly referred to as the “Big 5” because of their dominance in trade publishing in terms of market share and revenue.

-

[19]

Thompson, Merchants of Culture; Fitzgerald in Corporations and Cultural Industries (2011) discusses Bertelsmann (the multimedia multinational conglomerate that owns Penguin Random House) as an example of a highly decentralized large corporation that gives relative autonomy to its subsidiaries.

-

[20]

Mark Davis, “Literature, Small Publishers and the Market in Culture,” Overland 190 (2008): 4–10; Emmett Stinson, “Small Publishers and the Emerging Network of Australian Literary Prosumption,” Australian Humanities Review 59 (April/May 2016): 23–42.

-

[21]

Ramdarshan Bold, “An Accidental Profession,” 99.

-

[22]

Small Business Administration website, “Table of Size Standards” 2017, https://www.ecfr.gov/cgi-bin/text-idx?SID=b919ec8f32159d9edaaa36a7eaf6b695&mc=true&node=pt13.1.121&rgn=div5#se13.1.121_1201.

-

[23]

John Storey, Graeme Salaman, and Kerry Platman, “Living with Enterprise in an Enterprise Economy,” Human Relations 58, no. 8 (2005): 1033–54.

-

[24]

Claire Squires and Padmini Ray Murray, “The Digital Publishing Communications Circuit,” Book 2.0 3, no. 1 (2013): 10.

-

[25]

Thompson, Merchants of Culture.

-

[26]

Ramdarshan Bold, “An Accidental Profession,” 84–102.

-

[27]

Rachel Noorda, “Transnational Scottish Book Marketing to a Diasporic Audience, 1995–2015,” PhD diss., University of Stirling, 2016; European Commission website, “What is an SME?” (2014), https://ec.europa.eu/growth/smes/business-friendly-environment/sme-definition/. Accessed Aug 2018.

-

[28]

Sourcebooks website, www.sourcebooks.com.

-

[29]

Ibid., 8.

-

[30]

Ramdarshan Bold, “An Accidental Profession,” 84.

-

[31]

Laura Miller, “Shopping for Community: The Transformation of the Bookstore into a Vital Community Institution,” Media, Culture & Society 21, no. 3 (1999): 385–407; Miller, Reluctant Capitalists.

-

[32]

Stinson, “Small Publishers,” 29.

-

[33]

Brooke Warner, “Why Distributors Are Book Publishing’s New Gatekeepers,” Huffington Post (2016).

-

[34]

Noël, “Neoliberal Economic Principles,” 220.

-

[35]

David Emblidge, “City Lights Bookstore: A Finger in the Dike,” Publishing Research Quarterly 21, no. 4 (2005): 30–39.

-

[36]

Simone Murray, Mixed Media: Feminist Presses and Publishing Politics (London: Pluto Press, 2004).

-

[37]

Lin Nin, Social Capital: A Theory of Social Structure and Actions (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001), 7.

-

[38]

Pierre Bourdieu. “The Forms of Capital (1986),” Cultural theory: An anthology 1 (2011): 81–93.

-

[39]

Stephen Baron, John Field, and Tom Schuller, Social Capital: Critical perspectives (OUP Oxford, 2000), 4.

-

[40]

Robert Putnam, “Bowling Alone: America’s Declining Social Capital,” in Culture and Politics (Palgrave Macmillan, New York, 2000), 223–34.

-

[41]

Baron, Field and Schuller, Social Capital.

-

[42]

Thompson, Merchants of Culture.

-

[43]

Hesmondhalgh, The Cultural Industries, 73.

-

[44]

Pierre Bourdieu The Rules of Art: Genesis and Structure of the Literary Field, trans. Susan Emanuel (Cambridge: Polity Press, 1996), 142.

-

[45]

David Hesmondhalgh, “Bourdieu, the media and cultural production,” Media, culture & society 28, no. 2 (2006): 222.

-

[46]

Pierre Bourdieu. “The Field of Cultural Production, or: The Economic World Reversed,” Poetics 12, no. 4-5 (1983): 311–56.

-

[47]

David Throsby, “Cultural capital,” Journal of Cultural Economics 23, no. 1-2 (1999): 3–12.

-

[48]

Arthur Thompson and Alonzo Strickland, Strategic Management: Concepts and Cases 13th ed. (New York City: McGraw-Hill, 2003).

-

[49]

Barbara Bartkus and Myron Glassman, “Do Firms Practice What They Preach? The Relationship Between Mission Statements and Stakeholder Management,” Journal of Business Ethics 83 (2007): 207–16.

-

[50]

American Marketing Association website, “Marketing Dictionary: Mission Statements,” https://web.archive.org/web/20170129171136/https://www.ama.org/resources/pages/dictionary.aspx?dLetter=M.

-

[51]

Christopher Bart, Nick Bontis, and Simon Taggar, “A Model of the Impact of Mission Statements on Firm Performance,” Management Decision 39, no. 1 (2001): 19–35; Sharon Kemp and Larry Dwyer, “Mission Statements of International Airlines: A Content Analysis,” Tourism Management 24, no. 6 (2003): 635–53; Sebastian Desmidt, Anita Prinzie, and Adelien Decramer, “Looking for Value of Mission Statements: A Meta-Analysis of 20 Years of Research,” Management Decisions 49, no. 3 (2011): 468–83

-

[52]

Linda Stallworth Williams, “The Mission Statement: A Corporate Reporting Tool with a Past, Present, and Future,” The Journal of Business Communication 45, no. 2 (2008): 100.

-

[53]

Valerij Dermol, Nada Trunk Sirca, Katarina Babnik, and Kristijan Breznik, “Connecting Research, Higher Education and Business: Implications for Innovation,” International Journal of Euro-Mediterranean Studies 6, no. 1 (2013): 65–80.

-

[54]

Thompson and Strickland, Strategic Management.

-

[55]

Dermol, Sirca, Babnik, and Breznik, “Connecting Research, ” 65–80.

-

[56]

Meredith David, Forest David, and Fred David, “Mission Statement Theory and Practice: A Content Analysis and New Direction,” International Journal of Business, Marketing, and Decision Science 7, no. 1 (2014): 95–110.

-

[57]

John Swales and Priscilla Rogers, “Discourse and the Projection of Corporate Culture: The Mission Statement,” Discourse & Society 6, no. 2 (1995): 238.

-

[58]

David Carson, Stanley Cromie, Pauric McGowan, and Jimmy Hill, Marketing and entrepreneurship in SMEs: an innovative approach (Pearson Education, 1995); Gerald Hills., Claes M. Hultman, and Morgan P. Miles, “The Evolution and Development of Entrepreneurial Marketing,” Journal of Small Business Management 46, no. 1 (2008): 99–112; Ian Fillis, “A Methodology for Researching International Entrepreneurship in SMEs: A Challenge to the Status Quo,” Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development 14, no. 1 (2007): 118-–35; David Carson, and Audrey Gilmore, “SME marketing management competencies,” International Business Review 9, no. 3 (2000): 363–82.

-

[59]

Desmidt, Prinzie, and Decramer, “Looking for Value of Mission Statements,” 468–83; John Slate, Craig Jones, Karen Wiesman, Jeanie Alexander, and Tracy Saenz, “School Mission Statements and School Performance: A Mixed Research Investigation,” New Horizons in Education 56, no. 2 (2008): 17–27.

-

[60]

Bartkus and Glassman, “Do Firms Practice What They Preach?”

-

[61]

Barabara Bartkus, Myron Glassman, and R. Bruce McAfee, “A Comparison of the Quality of European, Japanese, and US Mission Statements: A Content Analysis,” European Management Journal 22, no. 4 (2004): 393–401; Noor Afza Amran, “Mission Statement and Company Performance: Evidence from Malaysia,” International Journal of Business and Behavioral Sciences 2, no. 4 (2012): 98–107.

-

[62]

Albert Boerema, “An Analysis of Private School Mission Statements,” Peabody Journal of Education 81, no. 1 (2006): 180–202; Christopher Morphew and Matthew Hartley, “Mission Statements: A Thematic Analysis of Rhetoric Across Institutional Type,” The Journal of Higher Education 77, no. 3 (2006): 456–571; Liz Morrish, and Helen Sauntson, “Vision, Values and International Excellence: The ‘Products’ that University Mission Statements Sell to Students,” in The Marketisation of Higher Education and the Student as Consumer, (Abingdon-on-Thames: Routledge, 2010), 87–99; James Davis, John Ruhe, Monle Lee, and Ujvala Rajadhyaksha, “Mission Possible: Do School Mission Statements Work?”, Journal of Business Ethics 70, no. 1 (2007): 99–110; Steven Stemler, Damian Bebell, and Lauren Ann Sonnabend, “Using School Mission Statements for Reflection and Research,” Educational Administration Quarterly 47, no. 2 (2011): 383–420; Douglas Grbic, Frederic W. Hafferty, and Phillip K. Hafferty, “Medical School Mission Statements as Reflections of Institutional Identity and Educational Purpose: A Network Text Analysis,” Academic Medicine 88, no. 6 (2013): 852–60; Timothy B. Palmer and Jeremy C. Short, “Mission Statements in US Colleges of Business: An Empirical Examination of Their Content with Linkages to Configurations and Performance,” Academy of Management Learning & Education 7, no. 4 (2008): 454–70; Steven Stemler and Damian Bebell, School Mission Statement: The Values, Goals, and Identities in American Education (Abingdon-on-Thames: Routledge, 2013); Jessica Velcoff and Joseph R. Ferrari, “Perceptions of University Mission Statement by Senior Administrators: Relating to Faculty Engagement,” Christian Higher Education 5, no. 4 (2006): 329–39; Sally Kuenssberg, “The Discourse of Self-Presentation in Scottish University Mission Statements,” Quality in Higher Education 17, no. 3 (2011): 279–98, Michael W. Firmin and Krista Merrick Gilson, “Mission Statement Analysis of CCCU Member Institutions,” Christian Higher Education 9, no. 1 (2009): 60–70.

-

[63]

Williams, “The Mission Statement” 94–119.

-

[64]

Bartkus, Glassman, and McAfee, “A Comparison of the Quality of European, Japanese and US Mission Statement,” 393–401; Boerema, “An analysis of private school mission statements,” 180–202; Williams, “The Mission Statement,” 94–119; Pradeep Dharmadasa, Yasantha Maduraapeurma, and Siriyama Kanthi Herath, “Mission statements and Company Financial Performance Revisited,” International Journal of Managerial and Financial Accounting 4, no. 3 (2012): 314–24; Elizabeth G. Creamer, Michelle R. Ghoston, Tiffany Drape, Chloe Ruff, and Joseph Mukuni, “Using Popular Media and a Collaborative Approach to Teaching Grounded Theory Research Methods,” International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education 24, no. 3 (2012); Dermol, Sirca, Babnik, and Breznik, “Connecting Research, Higher Education and Business,” 65–80; David et al, “Mission Statement Theory and Practice,” 95–110; Ammar Ali Alawneh, “The Impact of Mission Statement on Performance: An Exploratory Study in the Jordanian Banking Industry,” Journal of Management Policy & Practice 16, no. 4 (2015): 73–87.

-

[65]

Kimberly Neuendorf and Anup Kumar, “Content Analysis,” The International Encyclopedia of Political Communication 1 (2002): 221–30.

-

[66]

Vijay Bhatia, Worlds of Written Discourse: A Genre-Based View (London: A&C Black, 2004).

-

[67]

Sasquatch Books website, “About,” http://www.sasquatchbooks.com/about/.

-

[68]

Jim Milliot, “Penguin Random House Busy Sasquatch,” Publishers Weekly (Oct 2017).

-

[69]

Warner, “Why Distributors Are Book Publishing’s New Gatekeepers.”

-

[70]

Penguin Random House website, “Our Story,” https://www.penguinrandomhouse.com/about-us/our-story/.

-

[71]

Macmillan website, “Our Publishers,” https://us.macmillan.com/publishers/.

-

[72]

Thompson, Merchants of Culture.

-

[73]

European Commission website, “What is an SME?”

-

[74]

Small Business Administration website, “Table of Size Standards.”

-

[75]

And many as “micro” publishers—see European Commission definition.

-

[76]

Chelsea Green Publishing website, “Mission & About Us,” https://www.chelseagreen.com/about/new-mission-about-us/.

-

[77]

Greystone Books website, “About Us,” https://greystonebooks.com/pages/about-us.

-

[78]

Sasquatch Books website, “About,” http://www.sasquatchbooks.com/about/.

-

[79]

Shambhala Publications website, “About,” https://www.shambhala.com/about-shambhala-publications/.

-

[80]

Natasha Gilmore, “Simon and Schuster Launches Muslim Imprint for Children’s Books,” Publishers Weekly (2016).

-

[81]

Claire Kirch, “Penguin Young Readers Announces Imprint for Diverse Books,” Publishers Weekly (Feb 2018).

-

[82]

Page Street Publishing website, “About Us,” https://www.pagestreetpublishing.com/about-us.

-

[83]

Graywolf Press website, “About Us,” https://www.graywolfpress.org/about-us.

-

[84]

Jump! website, “About Jump!” https://www.jumplibrary.com/about/.

-

[85]

Europa Editions website, “About Us,” https://www.europaeditions.com/about-us.

-

[86]

Diversion Books website, “About,” http://www.diversionbooks.com/about/.

-

[87]

Christian Grönroos, “From Marketing Mix to Relationship Marketing: Towards a Paradigm Shift in Marketing,” Asia-Australia Marketing Journal 2, no. 1 (1994), 9–29; Michael Harker and John Egan, “The Past, Present, and Future of Relationship Marketing,” Journal of Marketing Management 22, no. 1-2 (2006): 215–42.

-

[88]

David Carson, Stanley Cromie, Pauric McGowan, and Jimmy Hill, Marketing and Entrepreneurship in SMEs: An Innovative Approach (London: Pearson Education, 1995); Audrey Gilmore, David Carson, and Ken Grant, “SME Marketing in Practice,” Marketing Intelligence and Planning 19, no. 1 (2001): 6–11; Ian Fillis, “A Methodology for Researching International Entrepreneurship in SMEs: A Challenge to the Status Quo,” Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development 14, no. 1 (2007): 118–35.

-

[89]

Familius website, “About Us,” http://www.familius.com/about-us.

-

[90]

Chelsea Green Publishing website, “Mission & About Us,” https://www.chelseagreen.com/about/new-mission-about-us/.

-

[91]

Brown Books Publishing Group website, www.brownbooks.com.

-

[92]

Independent Book Publishers Association website, “IBPA Hybrid Publisher Criteria” (2017), https://www.ibpa-online.org/page/hybridpublisher.

-

[93]

Diversion Books website, “About,” http://www.diversionbooks.com/about/.

-

[94]

BenBella Books website, “About BenBella,” https://www.benbellabooks.com/about/.

-

[95]

Greenleaf Book Group website, “About Greenleaf,” https://greenleafbookgroup.com/about.

-

[96]

Claire Squires, “Taste and/or Big Data? Post-Digital Editorial Selection,” Critical Quarterly 59, no. 3 (2017): 24–38.

-

[97]

Ted Striphas, The Late Age of Print: Everyday Book Culture from Consumerism to Control (New York City: Columbia University Press, 2009).

-

[98]

Michael Bhaskar, Curation: The Power of Selection in a World of Excess (New York City: Hachette, 2016).

-

[99]

Cottage Door Press website, “Our Story,” https://cottagedoorpress.com/pages/our-story-1.

-

[100]

Page Street Publishing website, “About Us,” https://www.pagestreetpublishing.com/about-us.

-

[101]

BenBella Books website, “About BenBella,” https://www.benbellabooks.com/about/.

-

[102]

Thompson, Merchants of Culture, 130.

-

[103]

PubWest, “PubWest Best Practices Survey Research Report 2017,” https://pubwest.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Final-2017-PubWest-Report_27Mar.pdf.

-

[104]

Noël, “Keeping Neoliberal Economic Principles at a Distance,” 227.

-

[105]

Thompson, Merchants of Culture, 142–43.

-

[106]

Simon, McCarthy and Hall, “Editorial Vision.”

Bibliography

- Alawneh, Ammar Ali. “The Impact of Mission Statement on Performance: An Exploratory Study in the Jordanian Banking Industry.” Journal of Management Policy & Practice 16, no. 4 (2015): 73–87.

- American Marketing Association website. “Marketing Dictionary: Mission Statements.” https://web.archive.org/web/20170129171136/https://www.ama.org/resources/pages/dictionary.aspx?dLetter=M.

- Amran, Noor Afza. “Mission Statement and Company Performance: Evidence from Malaysia.” International Journal of Business and Behavioral Sciences 2, no. 4 (2012): 98–107.

- Baron, Stephen, John Field, and Tom Schuller, Social Capital: Critical Perspectives. Oxford University Press: Oxford, 2000.

- Bart, Christopher, Nick Bontis, and Simon Taggar. “A Model of the Impact of Mission Statements on Firm Performance.” Management Decision 39, no. 1 (2001): 19–35.

- Bartkus, Barbara and Myron Glassman. “Do Firms Practice What They Preach? The Relationship Between Mission Statements and Stakeholder Management.” Journal of Business Ethics 83 (2007): 207–16.

- Bartkus, Barbara, Myron Glassman, and R. Bruce McAfee. “A Comparison of the Quality of European, Japanese, and US Mission Statements: A Content Analysis.” European Management Journal 22, no. 4 (2004): 393–401.

- Bay Area Independent Publishers Association website. “About Us.” https://www.baipa.org/baipa/.

- Bhaskar, Michael. Curation: The Power of Selection in a World of Excess. New York City: Hachette, 2016.

- Bhatia, Vijay. Worlds of Written Discourse: A Genre-Based View. London: A&C Black, 2004.

- Boerema, Albert. “An Analysis of Private School Mission Statements.” Peabody Journal of Education 81, no. 1 (2006): 180–202.

- Bourdieu, Pierre. The Field of Cultural Production: Essays on Art and Literature. New York City: Columbia University Press, 1993.

- Bourdieu, Pierre. “The Forms of Capital.” Cultural Theory: An Anthology 1 (2011): 81–93.

- Bourdieu, Pierre. The Rules of Art: Genesis and Structure of the Literary Field, trans. Susan Emanuel. Cambridge: Polity Press, 1996.

- Brier, Evan. “The Editor as Hero: The Novel, the Media Conglomerate, and the Editorial Critique.” American Literary History 30, no. 1 (2018): 85–107.

- Carson, David, Stanley Cromie, Pauric McGowan, and Jimmy Hill. Marketing and Entrepreneurship in SMEs: An Innovative Approach. London: Pearson Education, 1995.

- Carson, David, and Audrey Gilmore. “SME marketing management competencies.” International Business Review 9, no. 3 (2000): 363–82.

- Creamer, Elizabeth G., Michelle R. Ghoston, Tiffany Drape, Chloe Ruff, and Joseph Mukuni. “Using Popular Media and a Collaborative Approach to Teaching Grounded Theory Research Methods.” International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education 24, no. 3 (2012).

- David, Meredith, Forest David, and Fred David. “Mission Statement Theory and Practice: A Content Analysis and New Direction.” International Journal of Business, Marketing, and Decision Science 7, no. 1 (2014): 95–110.

- Davis, James, John Ruhe, Monle Lee, and Ujvala Rajadhyaksha. “Mission Possible: Do School Mission Statements Work?” Journal of Business Ethics 70, no. 1 (2007): 99–110.

- Davis, Mark. “Literature, Small Publishers and the Market in Culture.” Overland 190 (2008): 4–10.

- Dermol, Valerij, Nada Trunk Sirca, Katarina Babnik, and Kristijan Breznik. “Connecting Research, Higher Education and Business: Implications for Innovation.” International Journal of Euro-Mediterranean Studies 6, no. 1 (2013): 65–80.

- Desmidt, Sebastian Anita Prinzie, and Adelien Decramer. “Looking for Value of Mission Statements: A Meta-Analysis of 20 Years of Research.” Management Decisions 49, no. 3 (2011): 468–83.

- Dharmadasa, Pradeep, Yasantha Maduraapeurma, and Siriyama Kanthi Herath. “Mission Statements and Company Funancial Performance Revisited.” International Journal of Managerial and Financial Accounting 4, no. 3 (2012): 314–24.

- Emblidge, David. “City Lights Bookstore: A Finger in the Dike.” Publishing Research Quarterly 21, no. 4 (2005): 30–39.

- European Commission website. “What is an SME?” (2014). http://ec.europa.eu/growth/smes/business-friendly-environment/sme-definition/index_en.htm.

- Fillis, Ian. “A Methodology for Researching International Entrepreneurship in SMEs: A Challenge to the Status Quo.” Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development 14, no. 1 (2007): 118–135.

- Firmin, Michael W. and Krista Merrick Gilson. “Mission Statement Analysis of CCCU Member Institutions.” Christian Higher Education 9, no. 1 (2009): 60–70.

- Galuszka, Patryk and Blanka Brzozowska. “Early Career Artists and the Exchange of Gifts on a Crowdfunding Platform.” Continuum 30, no. 6 (2016): 744–53.

- Gilmore, Audrey, David Carson, and Ken Grant. “SME Marketing in Practice.” Marketing Intelligence and Planning 19, no. 1 (2001): 6–11.

- Gilmore, Natasha. “Simon and Schuster Launches Muslim Imprint for Children’s Books.” Publishers Weekly (2016).

- Grbic, Douglas, Frederic W. Hafferty, and Phillip K. Hafferty. “Medical School Mission Statements as Reflections of Institutional Identity and Educational Purpose: A Network Text Analysis.” Academic Medicine 88, no. 6 (2013): 852–60.

- Grönroos, Christian. “From Marketing Mix to Relationship Marketing: Towards a Paradigm Shift in Marketing.” Asia-Australia Marketing Journal 2, no. 1 (1994): 9–29.

- Hallin, Daniel. “Neoliberalism, Social Movements and Change in Media Systems in the Late Twentieth Century.” The Media and Social Theory. Abingdon-on-Thames: Routledge, 2008.

- Harker, Michael and John Egan. “The Past, Present, and Future of Relationship Marketing.” Journal of Marketing Management 22, no. 1-2 (2006): 215–42.

- Hawthorne, Susan. Bibliodiversity: A Manifesto for Independent Publishing. North Geelong: Spinfex Press: 2014.

- Hess, David. Localist Movements in a Global Economy: Sustainability, Justice, and Urban Development in the United States. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2009.

- Hesmondhalgh, David. The Cultural Industries. London: Sage, 2013.

- Hesmondhalgh, David. “Bourdieu, the Media and Cultural Production.” Media, Culture & Society 28, no. 2 (2006).

- Hills, Gerald E., Claes M. Hultman, and Morgan P. Miles. “The Evolution and Development of Entrepreneurial Marketing.” Journal of Small Business Management 46, no. 1 (2008): 99–112

- Independent Book Publishers Association website. “Affiliate Associations.” https://www.ibpa-online.org/page/affiliates.

- Independent Book Publishers Association website. “Our History.” https://www.ibpa-online.org/page/history.

- Kemp, Sharon and Larry Dwyer. “Mission Statements of International Airlines: A Content Analysis.” Tourism Management 24, no. 6 (2003): 635–53.

- Kirch, Claire. “Penguin Young Readers Announces Imprint for Diverse Books.” Publishers Weekly (Feb 2018).

- Kuenssberg, Sally. “The Discourse of Self-Presentation in Scottish University Mission Statements.” Quality in Higher Education 17, no. 3 (2011): 279–98.

- Le Masurier, Megan. “Independent Magazines and the Rejuvenation of Print.” International Journal of Cultural Studies 15, no. 4 (2012): 383–98.

- McCleery, Alastair. “The Return of the Publisher to Book History: The Case of Allen Lane.” Book History 5, no. 1 (2002): 161.

- Miller, Laura. “Shopping for Community: The Transformation of the Bookstore into a Vital Community Institution.” Media, Culture & Society 21, no. 3 (1999): 385–407.

- Miller, Laura. Reluctant Capitalists: Bookselling and the Culture of Consumption. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006.

- Milliot, Jim. “Penguin Random House Busy Sasquatch.” Publishers Weekly (Oct. 2017).

- Morphew, Christopher and Matthew Hartley. “Mission Statements: A Thematic Analysis of Rhetoric Across Institutional Type.” The Journal of Higher Education 77, no. 3 (2006): 456–571.

- Morrish, Liz, and Helen Sauntson. “Vision, Values and International Excellence: The ‘Products’ that University Mission Statements Sell to Students.” In The Marketisation of Higher Education and the Student as Consumer, 87–99. Routledge, 2010.

- Murray, Simone. Mixed Media: Feminist Presses and Publishing Politics. London: Pluto Press, 2004.

- Neuendorf, Kimberly and Anup Kumar. “Content Analysis.” The International Encyclopedia of Political Communication 1 (2002): 221–30.

- Nin, Lin. Social Capital: A Theory of Social Structure and Actions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001.

- Noël, Sophie. “Keeping Neoliberal Economic Principles at a Distance.” Global Management, Local Resistances: Theoretical Discussion and Empirical Case Studies 129 (2015): 220–37.

- Noorda, Rachel. “Transnational Scottish Book Marketing to a Diasporic Audience, 1995–2015.” PhD diss., University of Stirling, 2016.

- Palmer, Timothy B. and Jeremy C. Short. “Mission Statements in US Colleges of Business: An Empirical Examination of Their Content with Linkages to Configurations and Performance.” Academy of Management Learning & Education 7, no. 4 (2008): 454–70.

- PubWest. “PubWest Best Practices Survey Research Report 2017.” https://pubwest.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Final-2017-PubWest-Report_27Mar.pdf.

- Putnam, Robert D. “Bowling alone: America’s declining social capital.” In Culture and Politics, 223–34. Palgrave Macmillan: New York, 2000.

- Ramdarshan Bold, Melanie. “An Accidental Profession: Small Press Publishing in the Pacific Northwest.” Publishing Research Quarterly 32, no. 2 (2016): 84–102.

- Schiffrin, André. The Business of Books: How International Conglomerates Took Over Publishing and Changed the Way We Read. London: Verso, 2001.

- Shuman, Michael. The Small-Mart Revolution: How Local Businesses Are Beating the Global Competition. Berrett-Koehler, 2007.

- Simon, Dan, Tom McCarthy and David Hall. “Editorial Vision and the Role of the Independent Publisher.” A History of the Book in America 5 (2009): 210–22.

- Slate, John, Craig Jones, Karen Wiesman, Jeanie Alexander, and Tracy Saenz. “School Mission Statements and School Performance: A Mixed Research Investigation.” New Horizons in Education 56, no. 2 (2008): 17–27.

- Small Business Administration website, “Table of Size Standards.” Updated 2017. https://www.ecfr.gov/cgi-bin/text-idx?SID=b919ec8f32159d9edaaa36a7eaf6b695&mc=true&node=pt13.1.121&rgn=div5#se13.1.121_1201.

- Sourcebooks website. www.sourcebooks.com.

- Squires, Claire and Padmini Ray Murray. “The Digital Publishing Communications Circuit.” Book 2.0 3, no. 1 (2013): 10.

- Squires, Claire. “Taste and/or Big Data? Post-Digital Editorial Selection.” Critical Quarterly 59, no. 3 (2017): 24–38.

- Stallworth Williams, Linda Stallworth. “The Mission Statement: A Corporate Reporting Tool with a Past, Present, and Future.” The Journal of Business Communication 45, no. 2 (2008): 100.

- Stemler, Steven and Damian Bebell. School Mission Statement, The: Values, Goals, and Identities in American Education. Abingdon-on-Thames: Routledge, 2013.

- Stemler, Steven, Damian Bebell, and Lauren Ann Sonnabend. “Using School Mission Statements for Reflection and Research.” Educational Administration Quarterly 47, no. 2 (2011): 383–420.

- Stinson, Emmett. “Small Publishers and the Emerging Network of Australian Literary Prosumption.” Australian Humanities Review 59 (April/May 2016): 23–42.

- Storey, John, Graeme Salaman, and Kerry Platman. “Living with Enterprise in an Enterprise Economy.” Human Relations 58, no. 8 (2005): 1033–54.