Résumés

Abstract

In his 1995 seminal work, The Translator’s Invisibility, Lawrence Venuti examines the impact of how translations are reviewed on the visibility of the translator. The American scholar contends that a fluent translation approach, which ultimately makes the work of the translator “invisible” to the final reader, is the main criterion by which translations are read and assessed by reviewers; any deviations from such fluent discourse are thus dismissed as inadequate. The present research will draw upon a corpus of British and French reviews collected from two broadsheet supplements in each country to analyze the extent to which the media’s reviews of published translations continue to reinforce—or indeed challenge—the notion of translators’ invisibility. The research will demonstrate that, whilst fluency and transparency are still revered by a large number of reviewers, especially in the UK, the reviews in this corpus show a remarkable degree of openness towards diverse translation approaches.

Résumé

Dans son important ouvrage paru en 1995, The Translator’s Invisibility, Lawrence Venuti examine l’incidence de la réception critique des oeuvres traduites sur la « visibilité » des traducteurs. Le chercheur américain y soutient qu’un style de traduction fluide, qui rend le travail du traducteur « invisible » aux yeux du lecteur final, constitue le principal critère qu'utilisent les critiques dans le jugement qu'ils posent sur une traduction. Aux yeux de ceux-ci, tout écart à cette fluidité rendrait la traduction insatisfaisante. Cet article, qui s’appuie sur un corpus de critiques recueillies dans deux journaux grand public britanniques et français, a pour but d’analyser dans quelle mesure les critiques renforcent – ou bien contestent – la notion de l’invisibilité des traducteurs. L’article conclut que, même si fluidité et clarté sont toujours prisées par la plupart des auteurs de critiques, surtout en Grande-Bretagne, on trouve dans celles composant le corpus une grande ouverture d’esprit quant à la diversité des stratégies utilisées par les traducteurs.

Corps de l’article

A translated text whether prose or poetry, fiction or nonfiction is judged acceptable by most publishers, reviewers and readers when it reads fluently, when the absence of any linguistic or stylistic peculiarities makes it seem transparent, giving the appearance that it reflects the foreign writer’s personality or intention or the essential meaning of the foreign text—the appearance, in other words, that the translation is not in fact a translation, but the “original.”[1]

The above quotation alludes to what Lawrence Venuti defines as invisibility in his 1995 seminal work, The Translator’s Invisibility: A History of Translation. The renowned translation scholar believes that the work of translators in contemporary British and American cultures is concealed not only by the way in which the translators themselves use the target language to naturalise the cultural elements and linguistic features of the source text for their target audience, but also by how translations are chosen by publishers, received and reviewed. Venuti considers the “violent” domesticating practices which are so prevalent in the English-speaking world to be unacceptable and calls upon translators to adopt what he terms “foreignizing” and “visible” practices in their work.[2] However, this would involve contravening what Venuti believes to be the golden rule set out by publishers and, according to him, reinforced by reviewers: he asserts that a fluent translation product—which “invisibly inscribe[s] foreign texts with British and American values and provide[s] readers with the narcissistic experience of recognising their own culture in a cultural other”[3]—is the ultimate goal of the translation process in the eyes of publishers and reviewers. Indeed, Venuti sees this as just a small part of the whole strategy to assert the dominance of Anglo-American values in the literary market, imposing these on other cultures through translation from English into other languages, while “producing cultures in the United Kingdom and the United States that are aggressively monolingual”[4] and averse to the foreign.

But what role exactly do reviewers play in this strategy? In The Translator’s Invisibility, Venuti examines a sample of reviews of translated works from a range of British and American periodicals, both literary and mass-audience, across a 60-year period. Venuti discovers that

on those rare occasions where reviewers address the translation at all, their brief comments usually focus on its style. . . And over the past sixty years the comments have grown amazingly consistent in praising fluency while damning deviations from it, even when the most diverse range of foreign texts is considered.[5]

Venuti supports his argument with a selection of excerpts from the reviews under investigation. The reviews seem to commend those translations which are “elegant,” “flowing,” and “fluent” —for example, “the translation is a pleasantly fluent one: two chapters of it have already appeared in Playboy magazine”[6]. However, they universally deplore those which are “wooden,” “clunky,” and “unidiomatic” —for example, “Helen Lane’s translation of the title of this book is faithful to Mario Vargas Llosa’s, ‘Elogio de la Madrasta,’ but not quite idiomatic.”[7]

However, Venuti does not elaborate upon whether the reviewers actually provide any justification or examples from the translated text to support their comments and indeed implies in his broader argument that they do not. In at least one case, though, namely that of the 1990 New York Times Book Review above, the extract is taken slightly out of context. The reviewer, Anthony Burgess, actually does expand on his comment, providing a justification which, having not read the original Spanish source text or the English target text myself, seems difficult to criticize:

Helen Lane’s translation of the title of this book is faithful to Mario Vargas Llosa’s, “Elogio de la Madrasta,” but not quite idiomatic. Since it reproduces the title of an essay written for a school assignment by a villainous young character, Alfonsito, something like “I adore my stepmother” might be better than “In Praise of the Stepmother.” The definite article sits awkwardly, turning the lovely stepmother, Lucrecia, into a kind of monument (like those statues in Italian stonemasons’ yards that represented “The Poet”), when she is all too warmly carnal.[8]

Moreover, Burgess also goes on to defend the translator, explaining that it is the differences between the two languages that are to blame for the elements of loss in Lane’s translation of Vargas Llosa’s novel. This example clearly demonstrates the problematic nature of Venuti using this review (and potentially others) to support his argument, as the reviewer does actually address some of the aspects that Venuti claims are generally neglected by reviewers.

Another potential flaw in Venuti’s investigation is its brevity in combination with its diachronicity. Any conclusions drawn from a study that examines reviews of 14 translated works over a 60-year period—Venuti only appears to look at one review for each of the books—can be at very best tentative. Whether he is simply using these select reviews as illustration or whether his corpus really is this small is admittedly difficult to ascertain, since the focus of The Translator’s Invisibility is not on reviews of translated literature, or in other words is not conceived as an in-depth study into the kind of language reviewers use to discuss translations. Questions around the methodology, such as how he chose those fourteen books and the reviews from different periodicals, also remain unanswered. Whilst this is understandable, it leaves open the possibility that Venuti may simply have chosen the reviews that most powerfully reinforce his arguments by praising fluency or damning foreignising practices; however, we must acknowledge that his study gave the issue of the translator’s visibility more prominence in the field of translation studies.

Anthony Pym is also critical of the way in which Venuti describes the reign of fluency as radically English. Pym provides a case study of how the Brazilian press praises fluency just as much as the reviews cited by Venuti and he thus believes that the “regime of invisibility could be just as strong there (I might say the same for Spain or France) as it is in Anglo-Americandom.”[9] The only actual reference that Venuti makes to the French context in his Invisibility chapter is when he compares the number of translations published in the UK and the US to various European countries in percentage terms. The current research project should allow us to judge to what extent Pym was correct in asserting that the regime of invisibility may be encouraged just as much by French reviewers as it allegedly is in the United Kingdom.

Whatever we may think about the validity of the conclusions of Venuti’s brief, but innovative, investigation, they gave rise to a good number of studies on the reviewing of translated literature in the late 1990s and 2000s (see Fawcett 2000,[10] Vanderschelden 2000,[11] and Bush 2004,[12] amongst others). These studies have provided weight to Pym’s argument that the regime of invisibility may well be just as strong in France as it is in the United Kingdom. They demonstrate that, in France, the translator or the fact of translation tends to be almost universally acknowledged, especially compared to the United Kingdom where this appears to be done on a rather more random basis. The studies also provide further evidence that the invisibility of the translator was encouraged by the criteria by which translations are reviewed in the United Kingdom in the late 1990s and early 2000s, namely transparency, fluency, and lucidity, but it may be also argued that the very fact that French reviewers—particularly those included in the Vanderschelden study—tend not to engage with the translation at all goes even further to concealing the work of the translator. The present research project will now attempt to build on these previous studies, assessing to what extent reviewers engage with the translation and whether target-oriented modes of translation continue to be revered by reviewers in the United Kingdom and France in the present day.

To do so, the research will draw upon a corpus of reviews collected from two broadsheet supplements in each country: The Times Literary Supplement and The Guardian in the United Kingdom and Le Monde and Libération in France. In a deviation from previous studies, which have tended to either focus on reviews of translations of fictional works or those of non-fiction works, this corpus includes all reviews of translated works published in the broadsheet supplements in the year 2015, regardless of the genre and no matter whether they write expressly about translation or not. Whereas Fawcett did not include reviews of translated works that “were treated as if they were English-language originals and no comments whatsoever of either a particular or general nature were made about translation”[13] in his investigation, the present research will evaluate in what percentage of cases the translation or translator is acknowledged and commented upon; it was thus important to collect all reviews of translated works. This gave rise to a relatively large number of reviews being collected, as can be observed from the figure below:

Figure 1

The number of reviews collected and included in the corpus from the United Kingdom and France in the year 2015

The number of reviews collected here shows certain parallels to the aforementioned Peter Bush study. He found that, over a two-month period, The Times Literary Supplement published 31 reviews, whereas Le Monde published around 80 reviews, and a similar trend can be observed in this collection of reviews. If we extrapolate the 31 reviews Bush collected during the two-month period in 2004 to the whole year, this would give rise to approximately 186 reviews, thus allowing us to assert that the number of reviews of translated works may have increased slightly in The Times Literary Supplement over the past ten years or so. If we do the same for the reviews in Le Monde, this would result in approximately 480 reviews in the year 2004, allowing us to predict that the number of reviews of translated works in Le Monde has potentially dropped, although it is, of course, not possible to be certain. However, compared to the United Kingdom, the number of reviews of translated works published in French broadsheets in 2015 remains considerably greater: Le Monde and Libération published 550 between them, compared to the 299 managed by The Times Literary Supplement and The Guardian. Of course, this is not to say that more column space is afforded to translation reviews in France than in the United Kingdom, as the reviews may be well more detailed and longer in the United Kingdom; however, the present research shall not focus on this particular issue.[14] The number of reviews included in this corpus will lend great validity to the findings and conclusions of this research and will enable us to go beyond existing studies into how translations are reviewed in the United Kingdom and France.

With the methodology for collection and the number of reviews included in the corpus now outlined, we move on to present the findings for the United Kingdom and France, beginning with the percentage of reviews that acknowledge the fact of translation, either directly or indirectly by naming the translator (see figure 2 below):

Figure 2

The percentage of reviews that acknowledge the translation or the translator in the British and French broadsheets

The results above may be considered somewhat surprising, especially given that previous studies outlined that the translator is generally acknowledged on a rather more random basis in the United Kingdom. More than 85% of reviews of translated works in both of the British broadsheets in 2015 acknowledge the fact of translation or mention the name of the translator. Indeed, The Times Literary Supplement acknowledges the fact of translation, directly or indirectly, without fail in each of its reviews of translated works. Given that both Vanderschelden and Bush discovered that the fact of translation was almost always acknowledged in France in the early 2000s, it was perhaps to be expected that Le Monde and Libération would also acknowledge the fact of translation in more than 95% of cases in the year 2015. Le Monde and Libération fail to acknowledge the fact of translation in just three out of 429 reviews and five out of 121 reviews respectively. Judging by these numbers, one could thus assert that translators have indeed become more visible on a very basic level in comparison to what Venuti found back in 1995, especially in the United Kingdom.

Another key fey factor when discussing the acknowledgement of the translation or the translator is the prominence of the location of the acknowledgement. Both Bush and Vanderschelden found that the fact of translation or the translator is almost systematically mentioned alongside the title of the work or in the heading of the review. This is certainly still the case for The Times Literary Supplement, Le Monde, and Libération. However, the first mention of the translation/translator generally comes within the main body of the text of the review in The Guardian. Whether the prominence of the location of the acknowledgement of the translation is of great significance at all is debatable and the author of this research project has thus far been unable to ascertain whether reviewers are provided with guidelines by the broadsheets as to how they should acknowledge the fact of translation in their reviews; however, the three publications included in this study in which the translator’s name appears before the main body of the review or alongside the title of the work achieve greater consistency in ensuring that the fact of translation is acknowledged: as we have seen, at least 95% of reviews in The Times Literary Supplement, Le Monde, and Libération acknowledge the fact of translation in some regard compared to just 86.4% of reviews in The Guardian.

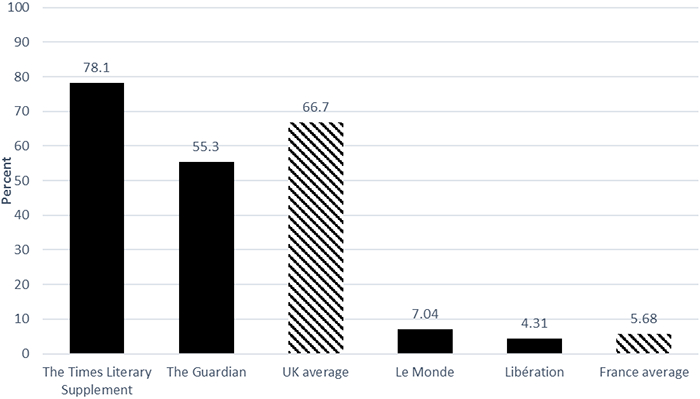

However, when it comes to commenting upon the quality of a translation, the picture is vastly different, as can be observed from the figure that follows:

Figure 3

The percentage of reviews that, having acknowledged the fact of translation, also make a comment on the quality of the translation in the United Kingdom and France

It is the French broadsheets that fare dramatically worse here: indeed, both Le Monde and Libération reviewers manage to provide a comment on the translation in less than one in ten reviews in which they have already acknowledged the fact of translation. These findings are similar to those of Bush and Vanderschelden, who both discovered that reviews very rarely comment on the quality of the translation in France. Both of the British broadsheets, on the other hand, go on to comment upon the quality of the translation after they have acknowledged the fact of translation relatively frequently—and The Times Literary Supplement reviewers even do so in almost four out of five reviews. Perhaps, then, we can suggest that Venuti’s criticism of reviewers for only addressing the translation on very rare occasions is now more applicable to the French context than the Anglo-American world. However, it is also important to mention at this point that, whilst generalizations are being made about the broadsheets in the United Kingdom and France for the purposes of this research, a small minority of reviewers, such as Michael Hofmann in The Times Literary Supplement and Nicolas Weill in Le Monde, almost always engage with the translation, providing a detailed commentary and often comparing the translation with the original source text; this may slightly skew the results of the research and offer a not entirely accurate portrayal of the way in which the broadsheets at hand review translations. Nonetheless, the sheer number of reviews included in the corpus should still allow us to pick up on certain trends regarding how translations are currently being reviewed and commented upon in British and French broadsheets.

Admittedly, a great deal of the reviews, particularly in the United Kingdom, that comment upon the translation quality do so with a brief blanket judgement, usually in the form of a single adjective, such as “fluent” or “accurate.” As far as this is concerned, Venuti’s argument about the brevity and superficiality of comments still seems to hold, although a minority of reviews do indeed substantiate their comments with further analysis and examples from the translated text. Vanderschelden, in her paper on quality assessment and literary translation, questions the purpose of such judgements, stating that “it could be argued that this type of commentary on a translation is of little value and has limited impact; if anything, it reinforces the general attitude of casualness towards the work of the translator.”[15] However, Lewis, a translator from German and French into English, takes the opposing view, declaring that she will “readily acknowledge the satisfaction even a single adjective—supple, fluid, accomplished—can bring. I’m happy to take the reviewer’s judgement on face value, without expecting any examples or justifications.”[16]

Regardless of whether we agree with the former comment or not, it is still important for us to analyze the type of words used to describe translation in the United Kingdom and France and whether they are used positively or negatively to allow us to draw comparisons with Venuti and subsequent studies. A selection of the words used to comment upon translations will be presented in the following section. These words have all appeared frequently in previous studies into the reviewing of translations and give us a glimpse of the greater picture: not only do they provide us with a broad range of comments relating to target-oriented translation (such as “fluent” and “lucid”), but they also include comments relating to source-oriented modes of translation (such as “accurate” and “faithful”). The majority of comments made about a translation in the reviews are more general in nature (subjective value judgements, e.g. “expertly” and “well”); however, these will not be covered within the scope of this research, which focuses exclusively on how target-oriented and source-oriented modes of translation are assessed by British and French reviewers.[17]

Previous studies in the United Kingdom indicated that transparency, which encompasses various notions such as clarity, fluency, lucidity and readability, was the main tenet by which translations are assessed and reviewed. However, the adjectives “clean/clear,” “flowing,” “fluent,” “lucid,” and “readable” are only used 25 times in the 299 translation reviews published by The Times Literary Supplement and The Guardian (and the word “transparent” itself, incidentally, never appears). As may be expected, they are used positively on each occasion to praise the translation. These kinds of words are used more frequently in The Times Literary Supplement than The Guardian; indeed, the latter only uses “fluent” and “readable” from this selection of words—and in one instance for each. It is thus difficult to assert whether broadsheets in general continue to have a strong affinity for target-oriented modes of translation; however, we can clearly see that the reviews in TheTimes Literary Supplement do still encourage transparency as one of the main goals of the translation process. The following example demonstrates how one review in The Times Literary Supplement uses the words “fluent” and “clear” to praise a translation:

“It is indeed timely that the Yale Jewish Lives’ series should have commissioned this wonderful, readable book, with the impressive Arthur Goldhammer responsible, as with many other recent French histories, for a clear and fluent translation.”[18]

None of the reviews collected from the French broadsheets, on the other hand, use words relating to target-oriented modes of translation, such as “fluide,” “limpide” or “lisible.” Indeed, most of the French reviews that actually comment upon the translation do so more generally using subjective value judgements, such as “excellent,” “magnifique,” and “superbe.” Yet the reviewers who do engage with the translation on a less subjective level seem to show admiration for those translators who have adopted source-oriented modes of translation. The words and phrases “a su rendre” and “restitue” appear twice and once respectively in Le Monde to commend the accuracy of the translation to the original source text (in line with Vanderschelden’s previous assertion that reviewers have a general affinity for accuracy). The following examples illustrate how these phrases are used to praise the translator for not deviating too far from the source text:

“La traduction a su rendre, à coups d’imparfait du subjonctif, la préciosité affectée et cocasse du protagoniste . . . et le moralisme assumé de l’écrivain.”[19]

“Julia Kristeva . . . signe une préface à l’anthologie établie et traduite par Aline Schulman, Les Chemins de la perfection, qui réunit cinq oeuvres principales de la Madre. Cette traduction sobre restitue toute l’audace incisive de l’écriture originale.”[20]

A similar trend may also be observed in the British broadsheets. Whilst transparency has always been—and, according to the findings of this research, continues to be—viewed positively by translation reviewers, previous studies have demonstrated that reviewers tend to have a “strong dislike of source-oriented modes of translation.”[21] The words used to test this claim in the present corpus were “accurate,” “precise,” and “preserving.” Despite the relative lack of use of these words by broadsheet reviewers compared to the words relating to transparency outlined above, they tend to indicate that source-oriented modes of translation are not always frowned upon, much like in France. The word “precise” is used positively, once in The Times Literary Supplement and once in The Guardian, whilst the word “accurate” is used positively once in The Times Literary Supplement. The following example illustrates how the word “accurate” is used to commend the work of the translator in achieving fidelity to the source text:

“More information should have been given. That aside, while both collections will give readers ample pleasure, Wolf’s [translation] conveys a much more accurate idea of Schönwerth’s aims and achievements.”[22]

However, it also becomes clear that translators in the United Kingdom can seemingly achieve an ‘optimal’ degree of accuracy, as too much emphasis on faithfulness to the source text may be considered pedantic by reviewers. This notion applies to the word “preserving” (or the verb “preserve”), which is used more frequently than any other word relating to source-oriented translation, and positively in eight of nine cases in The Times Literary Supplement. The first example below demonstrates how “preserving” is used positively when the translation provides greater access to the original source text and its crucial elements, whereas the second example illustrates how the word is used negatively when features of the source text are retained to such an extent that they detract from the overall reading experience:

“This translation deserves high praise. Yates has managed to preserve the tone of the original Catalan without having recourse to potentially awkward archaisms. He does this by combining contemporary vocabulary with words that were used two or three generations ago.”[23]

“The translations of his verse that he undertook himself or supervised . . . never quite captured the genuine Brodsky, coming across as over-ingenious, almost light-verse-like, in their insistence on preserving rhyme and metre.”[24]

Whilst this may be the case, in line with the general positivity demonstrated towards faithfulness and the retention of key source text features outlined above, British reviewers often take a negative view when the target text is not faithful enough to the source text and entails a degree of loss: “lost” appears three times in The Times Literary Supplement and once in The Guardian, and is used negatively on each occasion; “inaccurate” appears once in The Times Literary Supplement and is also used negatively to criticize the degree to which the translator has deviated from the original source text:

“Unfortunately, there are problems with the translation. Émile’s picaresque humour has been lost in horribly unnatural dialogue, rendered not from the Spanish original, but from French—hence the bizarre retention of French names.”[25]

“It is unfortunate that, for a writer who prided himself on being a stylist, Morand should be let down by Euan Cameron’s often sloppy and inaccurate translation. Wrong notes include ‘police car’ for ‘numéro de police’ (licence plate), ‘Roman’ for ‘roman’ (Romanesque), ‘Russian mountains’ for ‘montagnes russes’ (fairground rollercoaster) and the distinctly unEnglish-sounding ‘women cooks’ and ‘bitch of a life.’”[26]

This notion of “lost in translation,” which appears four times in the British broadsheet reviews, only appears in one French review from Libération. However, the reviewer is not critical of the translator, outlining that generally the translation remains faithful to the source text, whilst also accepting that the very process of translating between two languages entails some degree of loss:

“À l’arrivée, le texte original et sa traduction française se répondent, chacun avec les spécificités de sa langue. Mais le français résiste par moments et l’on perd des petits trésors en chemin—personne n’y peut rien, ce sont deux musiques différentes.”[27]

The analysis of the reviews collected from two broadsheets in both the United Kingdom and France conducted in this research has demonstrated that the notion of invisibility of both the translation and the translator observed by Venuti in the Anglo-American context in The Translator’s Invisibility and by subsequent studies has now changed in several significant ways. Firstly, the fact of translation and translators are now very rarely completely ignored in reviews. Indeed, we have seen that the broadsheets in both the United Kingdom and France acknowledge the translation directly or indirectly in at least 85% of cases. The translator is thus more visible on a very basic level in both countries. Secondly, reviews now address the translation, at least to some extent, more frequently in the United Kingdom. Venuti’s claim that reviewers very rarely address the translation in the United Kingdom has been disproven here, with at least 55% of reviews that acknowledge the fact of translation also commenting upon the translation in some manner in the British broadsheets. The picture is vastly different in France, however, with less than eight percent of reviews in both Le Monde and Libération building on their acknowledgement of the fact of translation to comment upon the translation. It has thus been suggested that Venuti’s assertion is now more applicable to the French context than the British context.

This research has also shown that target-oriented forms of translation linked to transparency are still revered by reviewers in the United Kingdom, especially in The Times Literary Supplement. However, British reviewers now demonstrate greater openness towards source-oriented forms of translation, with faithfulness and accuracy appearing in overwhelmingly positive terms in this collection of reviews. The French broadsheet reviewers, on the other hand, never used words relating to transparency, yet invariably praised those translations which were faithful and accurate, retaining key features of the source text. Overall, it seems fair to suggest that reviewing practices in the United Kingdom and France have improved to at least some extent over the past two decades in that translators and their work have become more “visible” in the British and French broadsheets in the present day.

Parties annexes

Appendices

Appendix 1

All of the adjectives and phrases used by British broadsheet reviewers to comment upon translations/translators in the United Kingdom. This table also gives an indication as to whether they are used to refer to translations/translators positively or negatively.

Appendix 2

All of the adjectives and phrases used by French broadsheet reviewers to comment upon translations/translators in France. This table also gives an indication as to whether they are used to refer to translations/translators positively or negatively.

Biographical note

Martyn Gray is currently a third-year PhD student at the University of Nottingham under the supervision of Dr. Kathryn Batchelor and Dr. Pierre-Alexis Mével. His research focuses on the reception of published translations across three platforms (Amazon, broadsheets and specialized journals) in the United Kingdom, France and Germany. He graduated from the University of Nottingham with a first-class degree in French and German and then undertook a Master’s degree in Translation with Interpreting at the University of Nottingham.

Notes

-

[1]

Lawrence Venuti, The Translator’s Invisibility: A History of Translation (Oxon: Routledge, 1995), 1.

-

[2]

Ibid., 266.

-

[3]

Ibid., 12.

-

[4]

Ibid., 12.

-

[5]

Ibid., 2.

-

[6]

This quotation comes from a 1969 edition of The Times Literary Supplement. It is cited on page 3 of the aforementioned The Translator’s Invisibility: A History of Translation.

-

[7]

This quotation comes from a 1990 edition of the New York Times Book Review. It is also cited on page 3 of The Translator’s Invisibility: A History of Translation.

-

[8]

Anthony Burgess, “On Wednesday He Does His Ears,” New York Times Book Review (1990), http://www.nytimes.com/1990/10/14/books/on-wednesday-he-does-his-ears.html.

-

[9]

Anthony Pym, “Venuti’s Visibility,” Target 8, no. 2 (1996): 170.

-

[10]

Peter Fawcett, “Translation in the Broadsheets,” The Translator 6, no. 2 (2000). In the conclusion to his paper, Fawcett reveals eight critical parameters and features by which translations tend to be assessed: a preference for transparent translation; a strong dislike of source-oriented modes of translation; paucity of evidence to back up criticism; criticism made on the basis of undefined authority; the non-provision of information that to academics is standard; very infrequent attempts to provide the reader with the original text; and a remarkable degree of frankness in negative criticism. These criteria form the basis for this research project.

-

[11]

Isabelle Vanderschelden, “Quality Assessment and Literary Translation in France,” The Translator 6, no. 2 (2000). The key discoveries of Vanderschelden’s paper are as follows: according to reviewers, the status of a book as a translation is of secondary importance and, most of the time, not worth commenting upon in the body of the review; however, when the translation is commented upon, the majority of French reviews make a brief blanket judgement, often in the form of a single adjective such as “excellent” or “remarquable,” or cite the translator briefly in parenthesis. She also discovers that there is a general affinity for translations that are both “accessible” and “accurate.”

-

[12]

Peter Bush, “Reviewing Translation: Barcelona, London and Paris,” independent article published by Brunel University (2004). Bush’s main finding is that, although the translator is often mentioned in the heading of a review, reviews of translations in the United Kingdom and France generally do not comment on the translation.

-

[13]

Fawcett, “Translation,” 296.

-

[14]

Such quantitative analysis of reviews of translations (e.g. How many words long is each review? What percentage of the review is actually dedicated to discussing the translation? etc.) could well form the basis of future research approaches in this field.

-

[15]

Vanderschelden, “Quality Assessment,” 285.

-

[16]

Tess Lewis, “On Reviewing Translations: Tess Lewis,” Words Without Borders (2011), http://www.wordswithoutborders.org/dispatches/article/on-reviewing-translations-tess-lewis.

-

[17]

For a detailed overview of all of the adjectives used to comment upon the quality of translation in the British and French broadsheets, including the more general, subjective comments, please refer to appendices 1 and 2 below.

-

[18]

Julian Wright, “A State Jew,” The Times Literary Supplement (2015), http://www.the-tls.co.uk/tls/reviews/biography/article1604532.ece.

-

[19]

Nicolas Weill, “Sauvages capitalistes !” Le Monde (2015), http://www.lemonde.fr/livres/article/2015/09/24/sauvages-capitalistes_4769420_3260.html#QTUb6PMDchHaAIBm.99. “By using the imperfect subjunctive on occasion, the translation has been able to reproduce the feigned and comical preciosity of the protagonist . . . and the assumed moralism of the author [my translation].”

-

[20]

Sean Rose, “Thérèse d’Avila nous revient, charnelle et incisive,” Le Monde (2015), http://www.lemonde.fr/livres/article/2015/05/14/therese-d-avila-nous-revient-charnelle-et-incisive_4633442_3260.html#HTwyQ46wpXx636gv.99. “Julia Kristeva has written a preface for the anthology established and translated by Aline Schulman, The Way of Perfection, which brings together five of the main works of the Madre. This understated translation reproduces all of the incisive boldness of the original writing [my translation].”

-

[21]

Fawcett, “Translation,” 305.

-

[22]

Ritchie Robertson, “Prince Dung-Beetle,” The Times Literary Supplement (2015), http://www.the-tls.co.uk/tls/reviews/literature_and_poetry/article1616443.ece.

-

[23]

Matthew Tree, “Strumpet Call,” The Times Literary Supplement (2015), http://www.the-tls.co.uk/tls/public/article1648601.ece.

-

[24]

Ellendea Proffer Teasley, “Poets and Heroes,” The Times Literary Supplement (2015), http://www.the-tls.co.uk/tls/reviews/biography/article1628352.ece.

-

[25]

Julius Purcell, “Wrinkles by Paco Roca Review—A Tender Graphic Novel about Alzheimer’s Disease,” The Guardian (2015), https://www.theguardian.com/books/2015/feb/13/wrinkles-paco-roca-review-graphic-novel-older-people-alzheimers.

-

[26]

Nicholas Hewitt, “Against Time,” The Times Literary Supplement (2015), http://www.the-tls.co.uk/tls/reviews/fiction/article1575690.ece.

-

[27]

Thomas Stélandre, “Eimear McBride, prose combat,” Libération (2015), http://next.liberation.fr/livres/2015/11/13/prose-combat_1413200. “In general, the original text and the French translation correspond with one another, each with its own particularities from the respective language. But the French is sometimes resistant and it loses some of the small treasures in the process. But nobody can do anything about that—the two languages are just inherently different [my translation].”

Bibliography

- Hewitt, Nicholas. “Against time.” The Times Literary Supplement (2015). http://www.the-tls.co.uk/tls/reviews/fiction/article1575690.ece.

- Purcell, Julius. “Wrinkles by Paco Roca Review—A Tender Graphic Novel about Alzheimer’s Disease.” The Guardian (2015). https://www.theguardian.com/books/2015/feb/13/wrinkles-paco-roca-review-graphic-novel-older-people-alzheimers.

- Robertson, Ritchie. “Prince Dung-Beetle.” The Times Literary Supplement (2015). http://www.the-tls.co.uk/tls/reviews/literature_and_poetry/article1616443.ece.

- Rose, Sean. “Thérèse d’Avila nous revient, charnelle et incisive.” Le Monde (2015). http://www.lemonde.fr/livres/article/2015/05/14/therese-d-avila-nous-revient-charnelle-et-incisive_4633442_3260.html#HTwyQ46wpXx636gv.99.

- Stélandre, Thomas. “Eimear McBride, prose combat.” Libération (2015). http://next.liberation.fr/livres/2015/11/13/prose-combat_1413200.

- Teasley, Ellendea Proffer. “Poets and Heroes.” The Times Literary Supplement (2015). http://www.the-tls.co.uk/tls/reviews/biography/article1628352.ece.

- Tree, Matthew. “Strumpet Call.” The Times Literary Supplement (2015). http://www.the-tls.co.uk/tls/public/article1648601.ece.

- Weill, Nicolas. “Sauvages capitalistes !” Le Monde (2015). http://www.lemonde.fr/livres/article/2015/09/24/sauvages-capitalistes_4769420_3260.html#QTUb6PMDchHaAIBm.99.

- Wright, Julian. “A State Jew.” The Times Literary Supplement (2015). http://www.the-tls.co.uk/tls/reviews/biography/article1604532.ece.

- Burgess, Anthony. “On Wednesday he Does his Ears.” New York Times Book Review (1990). http://www.nytimes.com/1990/10/14/books/on-wednesday-he-does-his-ears.html.

- Bush, Peter. “Reviewing Translation: Barcelona, London and Paris.” Independent article published by Brunel University (2004). http://www.brunel.ac.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0006/110697/Peter-Bush-pdf,-Reviewing-Translations-Barcelona,-London-and-Paris.pdf.

- Fawcett, Peter. “Translation in the Broadsheets.” The Translator 6, no. 2 (2000): 295–307.

- Lewis, Tess. “On Reviewing Translations: Tess Lewis.” Words Without Borders (2011). http://www.wordswithoutborders.org/dispatches/article/on-reviewing-translations-tess-lewis.

- Pym, Anthony. “Venuti’s Visibility.” Target 8, no. 2 (1996): 165–177.

- Vanderschelden, Isabelle. “Quality Assessment and Literary Translation in France.” The Translator 6, no. 2 (2000): 271–293.

- Venuti, Lawrence. The Translator’s Invisibility: A History of Translation. Oxon: Routledge, 1995.

Primary Sources

Secondary Sources

Liste des figures

Figure 1

The number of reviews collected and included in the corpus from the United Kingdom and France in the year 2015

Figure 2

The percentage of reviews that acknowledge the translation or the translator in the British and French broadsheets

Figure 3

The percentage of reviews that, having acknowledged the fact of translation, also make a comment on the quality of the translation in the United Kingdom and France