Résumés

Abstract

Malapropisms have received little specific attention in studies concerning the translation of humorous phenomena, as researchers have usually addressed the broader category of wordplay. Malapropisms, however, while a subtype of wordplay, also represent a phenomenon in their own right, and their longstanding use as a humorous device in literature, as well as the particular translation problems they pose, largely justify a separate analysis. Additionally, more often than not, the translation of malapropisms has been addressed from a prescriptive point of view. Therefore, in addressing the translation of malapropisms in the Spanish versions of Joseph Andrews, this paper has a double aim. Firstly, it seeks to highlight the need for a comprehensive framework of analysis capable of singling out the particular features of malapropisms within a given text, paying attention most notably to their function in the text as a whole, their typological range, and the translation techniques employed to deal with them, as well as some extratextual factors that may help explain certain decisions taken by translators and their degree of acceptance within the target literary system. Secondly, it draws attention to descriptive analysis, showing how, by improving knowledge of the phenomena involved, it can prove useful for further translations.

Keywords:

- malapropism,

- typology,

- function,

- translation technique,

- Fielding

Résumé

Les malapropismes, ou impropriétés de langage, n’ont pas été étudiés en profondeur dans le cadre des travaux sur la traduction de l’humour, car ce sont les jeux de mots, une catégorie plus vaste, qui a plutôt fait l’objet de l’attention des chercheurs. Bien qu’ils soient une sorte de jeux de mots, les malapropismes représentent cependant un phénomène à part entière. Une analyse distincte se justifie, car, d’une part, ils constituent de longue date un procédé humoristique littéraire et, d’autre part, ils posent des problèmes de traduction particuliers. De plus, leur traduction a souvent été envisagée sous un angle normatif. Notre étude, qui est consacrée à la traduction des malapropismes dans les versions espagnoles de Joseph Andrews, a donc un double objectif. Le premier vise à mettre en évidence la nécessité d’un cadre global d’analyse pouvant faire ressortir les caractéristiques spécifiques des malapropismes dans un texte donné. Ce cadre doit permettre notamment d’analyser leur fonction dans la totalité du texte, leur typologie et les procédés de traduction dont ils font l’objet, ainsi que certains facteurs extratextuels permettant d’expliquer certaines décisions de traduction et leur degré d’acceptation dans le système littéraire cible. Le deuxième objectif est d’attirer l’attention sur l’analyse descriptive pour montrer comment une meilleure connaissance des phénomènes en jeu peut se révéler utile dans d’autres situations de traduction.

Mots-clés :

- malapropisme,

- typologie,

- fonction,

- procédé de traduction,

- Fielding

Corps de l’article

1. Introduction

Poetry, humour and wordplay lie at the centre of the age-old debate about the untranslatability of literature. However, since the emergence of descriptive translation theories, it has become clear that a more realistic and optimistic approach was needed to tackle these “intractable” problems. The adoption of a target-oriented viewpoint resulted in a change in focus, moving away from the inevitably subjective “ought” to an approach that centres on the “is” of translation, what translators actually do and issues of acceptability. In so far as wordplay is concerned, Delabastita (1993) marked a turning point towards a greater array of research perspectives, with audiovisual translation and Shakespeare being perhaps the subjects receiving the greatest attention. Nevertheless, little has been done specifically on malapropisms, a particular type of wordplay whose distinctive features require special treatment in order to single out the key factors involved in its translation. Some studies dealing with malapropisms are almost exclusively quantitative (Offord 1990), while others stress qualitative analysis in order to derive useful advice to enhance the effectiveness of translation for the stage (Sanderson 2002). Others are openly prescriptive and are grounded in a very restrictive conception of translation, a conception which they employ as a measuring rod for analysis (Soto Vázquez 1993; 2001; 2008; Sánchez Rodríguez 2005).

It is my aim to present a study that is both qualitative and quantitative, seeking not only to identify patterns in the use of translation techniques, but also to examine the effects they produce in the target text (TT) as a whole. Henry Fielding’s The History of the Adventures of Joseph Andrews and his Friend Mr. Abraham Adams was chosen as the object of study for a number of reasons, not least the abundance of malapropisms it contains. But also of importance was the stark contrast between Fielding’s prestigious position in the literary canon as one of the fathers of the English novel and his neglect by translation researchers and Spanish publishers almost until the last third of the 20th century. Therefore, this study also intends to draw attention to his singularity and literary weight by examining some features of his writing and how they have been dealt with in the Spanish translations, something which may in turn lead to consider how the author might have been perceived in Spain (at least to a certain extent) and the appraisal given to the translations of the novel studied. In this respect, the very few studies on the translation of Fielding’s malapropisms into Spanish are strongly evaluative (Sánchez Rodríguez 2005; Soto Vázquez 2008). So much so, that they even end up discrediting the translators of Joseph Andrews. In this paper it is argued that their value judgements originate in a very rigid conception of translation. As will be shown, approaching the issue from a new perspective can yield a different assessment.

There are two translations of Joseph Andrews into Spanish. They were done by José Antonio López de Letona (Fielding 1742/1977) and by José Luis López Muñoz in1978 (Fielding 1742/2001), but only the latter offers a variety of translation strategies for malapropisms, the former almost invariably “avoiding” their translation. Therefore, there will appear to be limitations in the scope of this paper, mostly concerning the description of a wide translational repertoire. However, in keeping with the wider framework I intend to provide, it will also be of interest to look for possible reasons behind any translational decision, including omissions, and to observe their acceptance in the target context. In addition to that, although only a case study is dealt with in this paper, it may well be considered a very revealing one, in the sense that it provides a diverse host of strategies and some evaluative data about their degree of appropriateness within the target context. This will also be of help in assessing the acceptability of the different translation strategies.

2. Methodology

This study deals with a controversial concept. Indeed, a universally accepted definition of malapropism is not to be found. Therefore, the conceptual debate on the term must first be outlined in order to then justify the scope given to the phenomenon in this paper. Following the terminological controversy, the function of malapropisms in literature and in the source text (ST) will also be briefly described so as to understand the significance of the phenomenon and then examine in the analysis how this function may have been transferred to the TT. Prior to the analyses and mainly with a view to exploring possible reasons behind translation decisions, a brief account of the impact of Joseph Andrews in Spain will be included, mostly focusing on the main features of the different editions and some of the particular circumstances surrounding the translations. Then, a typology for malapropisms and a list of translation techniques will be provided so as to serve as a tool for the subsequent analysis and classification of the malapropisms in Joseph Andrews. This typology is based on phonetic, morphological, syntactic and semantic criteria. An additional criterion that seeks to classify malapropisms depending on their existence or non-existence in the lexicon of the language is also introduced as a result of the stance adopted on the definition of the term. Further justification for this criterion will be found in point 6 below. The list of translation techniques follows Delabastita’s (1993) scheme for the translation of puns and Toury’s (1995) framework for the translation of metaphors. Thereafter, a ST/TT comparison of fragments containing malapropisms will be carried out, emphasising their typological features, the techniques used by translators, the possible shifts in relation to the ST, and the effects produced in the TT. Only a few representative cases will be presented in the qualitative analysis (due to limitations of space), but all the malapropisms in Joseph Andrews will be included in the quantitative analyses in order to extract any possible patterns in their translation regarding technique frequency and differences in typology. The implications of all this for the TT as compared with the ST will be examined as well.

3. What is a malapropism?

Originating in the character of Mrs. Malaprop, from Richard Brinsley Sheridan’s The Rivals (1775),[1] the definition of malapropism entails differences in nuance depending on the source consulted. Generally speaking, the term admits a broader definition and a narrower one, with the subsequent range of variation between the poles. The narrow definition can be exemplified by Hockett’s characterisation:

[…] a malapropism is a ridiculous misuse of a word, in place of one it resembles in sound, especially when the speaker is seeking a more elevated or technical style than is his wont and the blunder destroys the intended effect. The incongruity is heightened if the speaker himself gives no sign of awareness of the blunder.

Hockett 1973: 110

The Oxford English Dictionary (OED)’s definition, however, allows far more leeway: “ludicrous misuse of words; an instance of this.”[2] Taking a somewhat middle ground between the two, the Encyclopaedia Britannica’s account is as follows: “verbal blunder in which one word is replaced by another similar in sound but different in meaning.”[3] A slightly different definition is given by the Merriam-Webster Dictionary: “The usually unintentionally humorous misuse or distortion of a word or phrase; especially: the use of a word sounding somewhat like the one intended but ludicrously wrong in the context.”[4]

Obviously, awareness or intention seems to be out of the question when it comes to literature. Indeed, it is the author who makes deliberate use of malapropisms for specific purposes which will, subsequently, have to be considered by translators. However, as it must be a word “similar in sound but different in meaning”[5] it will necessarily be an existing term. But, if it may also be the “distortion of a word,”[6] it follows that it can be a non-existing term, a nonsense word. This view is also implicitly shared by authors such as Cuddon and Preston, who accept correxions or squintasense as examples of malapropisms (Cuddon and Preston 1998: 489). And the Merriam-Webster definition even admits distortion at phrase level. Moreover, if phonetic similarity is agreed upon in some definitions, the broad or non-exclusive definitions by the OED and the Merriam-Webster Dictionary also allow for semantic impropriety to be the only basis of some malapropisms, with no need for any similarity in sound with the intended term. Aitchison, in turn, reminds us of Mrs. Malaprop’s confusion of word classes, for instance the use of an adjective for a verb (Aitchison 2008: 251). Things become even more entangled when the OED provides some examples of malapropisms taken (precisely) from Joseph Andrews, such as confidous, a non-existing word where the key lies in the misuse of the suffix. And there are more examples of malapropisms in the novel that go beyond some of the above definitions.

To put it in a nutshell, either there are types of malapropisms that do not fit the definitions provided or only some of the linguistic errors in Joseph Andrews can be considered malapropisms proper. This paper takes a broad concept of malapropism. That means that non-existing words (words not included in dictionaries) and words that bear no phonetic similarity to the presumed correct word in the given context will be labelled as malapropisms. The reason for this is that it is not my primary goal to set clear boundaries on the term and produce a new definition, but to analyse speech errors in the novel. Therefore, these errors will be referred to as malapropisms, although they may fit its different definitions in varying degrees. If it is taken into account that speech errors in Joseph Andrews are almost exclusively made by the character of the chambermaid Mrs. Slipslop, this decision may find further support in the fact that the OED includes the term slipslop with a (quite broad) definition similar to that of malapropism: “A blunder in the use of words, esp. the ludicrous misuse of one word for another; the habit of making mistakes of this nature.”

4. The function of malapropisms in Joseph Andrews

Malapropisms are a deep-rooted phenomenon in English literature, to such an extent that Otto Jespersen (1905: 145) considered English fiction to be unrivalled in its use of “characters made ridiculous to the reader by the manner in which they misapply or distort ‘big’ words.” Schlauch (1987) points out that malapropisms were probably present in popular literature a few centuries before Shakespeare. The Bard’s Dogberry, from Much Ado About Nothing (1598-1599),[7] is one of the characters most frequently used to exemplify malapropistic use. Other illustrious representatives are Mrs. Malaprop herself, from Brinsley Sheridan’s The Rivals (1775; see note 1); Smollett’s Winifred Jenkins, from The Expedition of Humphry Clinker (1771),[8] and Fielding’s Mrs. Slipslop.[9] Unquestionably a humoristic resource, other literary purposes are usually attached to malapropisms, namely characterisation. Thus, if malapropisms can play a major role in character description, at the same time they can also be portraying some aspects of the social environment wherein characters interact. Regarding Joseph Andrews, some authors share Hatfield’s view (1968) about the (social) corruption of language as a key feature in Fielding. So does Soto Vázquez when he includes Fielding’s malapropisms within the general framework of Hatfield’s thesis:

Fielding, a keen observer of society, closely followed the evolution of behaviour in his sociocultural milieu and was able to identify those groups responsible for the progressive corruption of language […]. Also, being well acquainted with the hypocritical upper-classes who introduced the semantic changes, he builds his theory on the deterioration of language and puts it across through some characters of literary fiction. For example, his Slipslop, who makes a lot of malapropisms… […] Fielding’s aim to reflect his attitude towards the linguistic inaccuracies present in the language leads him to make use of many literary resources […], especially the use of jargon and malapropisms.

Soto Vázquez 2008: 40; translated by the author[10]

Hatfield (1968: 9) concedes that there is not such a thing as a “fully developed theory of language” in Fielding, let alone a fully developed theory of the corruption of language. He has traced in Fielding’s writings his concern about, and criticism of, language distortions; but the underlying concern of the author is with social corruption, which linguistic corruption ultimately mirrors. According to Irwin, Fielding mainly uses language as a pretext for the discussion of moral values (Irwin 1969: 507). Some of those moral concerns are undeniably at the root of Joseph Andrews, and are closely connected to Fielding’s views of the comic:

The only Source of the true Ridiculous (as it appears to me) is Affectation. […] Now Affectation proceeds from one of these two Causes, Vanity, or Hypocrisy: for as Vanity puts us on affecting false Characters, in order to purchase Applause; so Hypocrisy sets us on an Endeavour to avoid Censure by concealing our Vices under an Appearance of their opposite Virtues.

Fielding 1741-1742/1999: 6

Malapropisms are then humorous and ridiculous as they reveal affectation, the vanity of those pretending to be more than they really are. Malapropisms disclose an eagerness for social mobility, and are perhaps evidence of the prestige associated with the language of the educated, which can make the latter a desirable good among the lower classes. Joseph Andrews takes place in a social milieu where class distinctions can be very subtle and where people may prove highly class-sensitive. Mrs. Slipslop, being a curate’s daughter, feels entitled to constantly remind people that she is not merely a chambermaid, hence her calamitous linguistic display (Fielding 1741-1742/1999: 21). In addition, malapropisms often “reveal psychic texture” (Hardy 1979: 58). That is to say, at times they may be the result of Freudian slips of the tongue, unveiling the speaker‘s real feelings or repressed thoughts. For example, this occurs when Mrs. Slipslop, after being almost accused by her mistress Lady Booby of excessive fondness for Joseph, quickly states that she will instantly follow her orders and dismiss him “with as much reluctance as possible” (Fielding 1741-1742/1999: 31). Reluctance is certainly what she feels, but obviously it was not her intent to make such an open statement. In that sense, malapropisms also become evidence of hypocritical behaviour, as is often the case with Mrs. Slipslop, thus contributing to one of Fielding’s essential themes.

To sum up, the role of malapropisms in Joseph Andrews may be regarded as serving a threefold purpose, as they operate as a humorous device, as a tool for characterisation (mainly of Mrs. Slipslop and partly of the social milieu of the times), and also as a contribution to the key themes in the novel.

5. Reception of Joseph Andrews in Spain: the Spanish translations

Henry Fielding (1707-1754) is best known as a novelist, and more specifically as the author of one of the first great English novels, Tom Jones; but he had previously been a renowned playwright. Then, the publication of the Licensing Act of 1737[11] put an abrupt end to his career as a dramatist, and Fielding turned to prose fiction with the advent of the next decade. Joseph Andrews is the first of his novels to appear (1742), although Jonathan Wild (1743) may have been written earlier. By then, Fielding had already published An Apology for the Life of Mrs. Shamela Andrews (1741), a short and merciless parody of Richardson’s Pamela: or, Virtue Rewarded (1740).[12] The plot of Joseph Andrews would also appear to owe much to Richardson’s enormously successful novel, as the Joseph of the title is no other than Richardson’s Pamela’s brother. Mirroring Pamela’s plot, now it is the handsome Joseph who has to “heroically” resist his mistress’ advances, but the novel goes far beyond the mere parody and marks the starting point for a personal narrative voice, which will reach its height with Tom Jones (1749). Finally, Amelia (1751) will be Fielding’s last novel. On the whole, in spite of some criticism, mostly regarding moral points, weakness or lack of complexity in the make up of some characters, and a narrative voice too prone to digressions and intrusions of all sorts, Fielding’s novels enjoyed a resounding success from the very beginning. They were soon translated into many languages, and Fielding was to become one of the most influential authors for nineteenth-century writers, as well as one of the most prominent English novelists of all times.

Notwithstanding this prestige, Fielding’s impact in Spain does not seem to have been on a par with his literary status. It is true that Amelia and Tom Jones (see Appendix below) were translated relatively early into Spanish (1795-1796 and 1796 respectively, both from the French version), but the next Spanish translation of Fielding was not to be found until 1933, when Tom Jones was translated directly into Spanish for the first time by Sans Huelin (Fielding 1749/1933). Thereafter, it was not until the 1960’s that three more translations and four adaptations of Tom Jones saw the light; largely as a result of the successful Oscar-winning film by Tony Richardson (Tom Jones, 1963).[13] Then, the only two Spanish translations of Joseph Andrews were published in the 1970’s; but Jonathan Wild was first translated as late as 2004 (Fielding 1743/2004, translated by Pérez Pérez, see Appendix), and there was no modern translation of Amelia until 2005 (Fielding 1751/2005, translated by Pérez). Until rather late in the 20th century, therefore, there appears to be little interest in translating Fielding into Spanish. The neglect of Joseph Andrews appears particularly striking and difficult to explain. Censorship having prevented two translations from being published by the end of the 18th century (in 1798), the novel fell thereafter into oblivion until the surprising appearance of not one, but two translations in the 1970’s: the first by José Antonio López de Letona (Fielding 1742/1977) and only a year later the second by José Luis López Muñoz (Fielding 1742/2008, translated by López Muñoz 1978). This simultaneous and sudden attention to Joseph Andrews may partly be explained by a revived interest in new or, as in this case, unpublished works. In the so-called transition years after Franco’s death in 1975, Spanish society started exploring its newly-gained liberties. Publishing houses seem to have been “on the hunt” for novelties during this period. For instance, Tristram Shandy (1759-1767) was also translated into Spanish for the first time, with three consecutive translations in only four years.[14] The first one (Sterne 1759-1767/1975) was translated by López de Letona, who would two years later translate Joseph Andrews for the same publishing house. Unaware of this translation, López Muñoz was already working on his own version before López de Letona’s was published (López Muñoz 2009, interview). Certainly, there are differences between these Spanish translations. López de Letona’s lacks an introduction, notes are scarce and there are only a few lines on the back cover devoted to the author’s biographical record. As far as the text is concerned, spelling and even syntactic errors are not infrequent. This may indicate that the translator was subject to time constraints and could not afford to revise the text adequately, since López de Letona himself says that at the time he was translating for Ediciones del Centro nearly against the clock and for the fun of it (López de Letona 2009, interview). In sharp contrast, Alfaguara presented an edition with a complete study on Fielding’s work by the translator himself, as well as an abundance of notes that serve mainly to elucidate cultural aspects. Whereas López de Letona’s translation was not reissued and soon went out of print, new editions of López Muñoz’s were published in 1997 (Fielding 1742/1997, translated by López Muñoz 1978) and 2008 (Fielding 1742/2008, translated by López Muñoz 1978), the latter having been revised by the translator. Moreover, if reissuing may signal acceptance of a translation, the fact that López Muñoz’s translation received the 1980’s National Translation Award (the most prestigious of its nature in Spain) is possibly even more revealing. In spite of this, as regards the translation of malapropisms, both versions have been subject to harsh criticism in the only two (brief) studies on the Spanish translations of the novel. The short article by Sánchez Rodríguez (2005) is even disqualifying. Noteworthy is the fact that his analysis does not even consider well-known strategies such as compensation as a potential “balancing” resource; nor does Soto Vázquez (2008), when he refers to inadmissible omissions or gratuitous malapropisms in López Muñoz’s translation. Likewise, Soto Vázquez hardly seems to approve of a translation technique differing from the devices used in the original malapropisms. That is the case when he defends that contracto should be the (only) choice in the following excerpt:

Soto Vázquez dismisses López Muñoz’s option (pernicial) because in his view it does not fit into the context and the translator has not taken into account that contract comes from the Latin contractus (Soto Vázquez 2008: 53). But arguably, it is López Muñoz’s option that best fits into the context, as it is the most likely to trigger associations with an intended term pernicioso [pernicious] that would make perfect sense in the sentence. Furthermore, the Spanish reader may consider very improbable a misuse of a word as usual as contrato, even by uneducated people; but not so if a high-register word like pernicioso is chosen. On the other hand, some options considered easy and evident are approved of, the translation of sect into secta being a case in point. In this instance a pun based on phonetic similarity in English (Slipslop says sect but she actually means sex) disappears in Spanish (secta/sexo). Additionally, Sánchez Rodríguez’s reasoning for explaining some malapropisms are dubious. Not least when he argues (Sánchez Rodríguez 2005: 282) that Slipslop’s mistaking of graceless for gracious may be attributable to Joseph appearing unpolished by aristocratic standards, although this claim does not fit Fielding’s portrayal of Joseph:

His Countenance had a Tenderness joined with a Sensibility inexpressible. Add to this the most perfect Neatness in his Dress, and an Air, which to those who have not seen many Noblemen, would give an Idea of Nobility.

Fielding 1741-1742/1999: 33

It would, therefore, seem that both studies are too restrictive in their assessment of the translations, and stick to terms such as fidelity or loyalty as the only guiding principle, without any further explanation as to how these long-standing controversial terms ought to be interpreted, thus ignoring two thousand years of translational debate. Perhaps the only thing they reveal is a willingness to equate fidelity with a strict ST orientation in the translation of malapropisms, or with strict adequacy, in Toury’s terms (Toury 1995).

6. Typology of malapropisms in JosephAndrews

The following typology attempts to characterise speech errors in Joseph Andrews in a way that enables comparisons with the translators’ solutions to be drawn. Linguistic categories are used in the classification, but this should not be taken as an attempt to produce a definitive linguistic typology for malapropisms. Rather, the typology is conceived as a potential tool for translators and translation researchers. Malapropisms can be approached from different angles at a time, and consequently the categories proposed in this paper will not be mutually exclusive. On the contrary, some malapropisms may be included in various categories, with each one of them highlighting a specific aspect that is more or less relevant to making the malapropism work. For instance, hint-or-fear has been formed by composition, and accordingly it will be included in the morphological criterion. But it seems quite obvious that its phonetic similarity to interfere plays a crucial role for its effectiveness. It may even be argued that separating morphological and phonetic criteria results in a more useful tool for the full characterisation of the malapropism in the original. Although morphology might suffice to describe this malapropism, I deem it preferable to separate sound from formation, as it must be assumed that both will have to be weighed by translators when deciding on an effective solution; and they are presumably less likely to remain together in the translation because of the structural differences between the languages involved. Moreover, in accordance with the previously discussed debate on the definition of malapropisms, it seems advisable to include a criterion accounting for the existence or non-existence of the word produced as a malapropism, thus broadening the range of criteria for comparing original and translated malapropisms. Obviously, by existence in the lexicon I mean that the term in question is included in dictionaries. As already seen, to some authors confusion between existing words is the premise to admit a malapropism as such, but other sources also accept non-existing terms. In fact, a number of the latter can be found in Joseph Andrews. Also, although this criterion might be considered as essentially pertaining to semantics or phonology, insofar as it concerns aspects such as nonsense words or phoneme replacement, both these categories do not comprehend all the malapropisms studied, as is the case with this additional criterion. So, from a translational point of view, it would be highly interesting to compare how many existing and non-existing words are found in both the ST and the TT, because that would yield a more comprehensive picture of the kind of malapropic discourse produced in each. And, in any case, the semantic criterion presented here seeks to elucidate the kind of semantic relationship between a malapropism and the actual word presumably intended, a relationship that will only be considered when both of them, the word in praesentia and in absentia, are “real” words. For other purposes, an additional subtype labelled “nonsense words” may be included within the semantic category. Yet for this paper I prefer to highlight and separately consider the existence/non-existence criterion for its usefulness as a tool for translation analysis. As a whole, then, attention shall be paid to the following:

-

Phonetics:

Same or similar initial and middle phonemic sequences: particle [particulars];

Same or similar final phonemic sequence: respect [suspect];

Same or similar initial and final phonemic sequences: compulsion [compassion];

Same or similar middle and final phonemic sequences: mophrodites [hermaphrodites];

Same or similar initial, middle and final phonemic sequences: ironing [irony].

-

Morphology:

Substitution, addition or omission of affixes: confidous [confident]; incommodated [accommodated];

Erroneous verbal inflection: commencated [commenced];

Composition: hint-or-fear [interfere];

Lexeme substitution: jinketting [junketing];

Combination of several methods, for example, lexeme distortion and erroneous suffix: ragmaticallest [pragmatical and suffix -est].

-

Syntax:

Shifting of word classes: nonsense man [nonsensical man].

-

Semantics:

Semantic opposition: reluctance [willingness];

Semantically related terms: regulations [rules];

Semantically unrelated terms: preambles [arguments];

Semantic shift due to association of homonyms: for instance, the noun contract acquires negative meaning related to its homonym verb.

-

Existence in the lexicon:

Word existing in the lexicon: fragrant [flagrant];

Word non-existing in the lexicon: currycuristick [characteristic].

7. Translation techniques for malapropisms

In this section a list of translation techniques will be presented. They stem from some previous similar proposals developed within the descriptive translation studies field, namely Delabastita’s strategies for the translation of puns (Delabastita 1993: 191-221) and Toury’s for the translation of metaphors (Toury 1995: 82-83). The main reason lies in the accounting for compensation and omission cases that this kind of categorisation provides. Therefore, the following list is proposed:

-

Malapropism into malapropism (M → M):

Same type of malapropism

Different type of malapropism

Malapropism into non-malapropism (M → non-M): there is text material in the TT corresponding to the original malapropism, although no actual malapropism is included in the translation;

Malapropism into zero (M → Ø), that is, pure omission of the ST segment containing a malapropism, ranging from only a word to a more extensive part of the text;

Non-malapropism into malapropism (non-M → M): the TT contains a malapropism intended as a translational solution for a ST segment that does not include any malapropism;

Zero into malapropism (Ø → M), that is to say, the addition in the TT of new text material non-existing in the ST and containing a malapropism;

Editorial techniques, mostly footnotes.

8. Qualitative analysis

What follows is a sample of cases which enable us to analyse techniques applied by translators, look for patterns and compare their result in the TT to the original. Backtranslations in italics are included for the sake of clarity.

The clergyman Adams wants to teach Joseph and is sounding out Slipslop in order to have the matter mentioned to her mistress, hence Slipslop’s answer. Preambles does not seem to invoke a phonetically similar term. On the contrary, it is just semantic inappropriateness that is found here, apparently due to Mrs. Slipslop’s ignorance of the actual meaning of this Latin-based word. López de Letona uses a M → non-M technique, whereas López Muñoz produces a malapropism also based on semantic inappropriateness, choosing an abstract word (concepto) whose meaning is not semantically related to that of the original preambles, although it may still be out of reach for Slipslop.

Slipslop produces two malapropisms by incorrectly adding the suffix ous, which usually accompanies words of Latin or Greek origin. The repetition of this error may also show that it is a kind of mistake typical of Mrs. Slipslop’s idiolect. In concisely it is the semantic similitude to shortly that seems to be decisive in triggering the malapropism. Deviations in meaning aside, López de Letona translates into non-malapropism in all the cases. As opposed to the original malapropisms, López Muñoz chooses existing words to form his malapropisms, again opting for complex terms, but without following the incorrect addition of suffixes of the ST malapropisms. He produces a strange and incorrect collocation with inquebrantable, more commonly used with abstract nouns. The word can also remind of incuestionable [unquestionable] in sound, but some syntactic adjustments would be needed for either term to fit into the sentence. This translation is not repeated in the following appearance of confidous, where he translates into non-malapropism, as he also does for concisely. For necessitous, he prefers a semantically incorrect option (ineluctable), but showing some similarity in form to that of inquebrantable, as it occurs between confidous and necessitous. Therefore, various techniques are employed, but coherence is best found in the preference for complex words and in a form of similitude between his options that mirrors relationships existing between the original malapropisms.

This is an example of non-M → M in López Muñoz. The word competente reminds of conveniente [convenient], although it may be argued that the meaning of the verb competer [be incumbent on] may also add to Slipslop’s confusion. In any case, this can be considered an instance of compensation.

In this excerpt, Slipslop tries to make advances to Joseph, and she gets angry because his respectful reaction disappoints her. López de Letona translates the malapropisms into non-malapropisms in all cases. López Muñoz also produces non-malapropisms for the corresponding malapropisms in the ST. However, he uses the technique non-malapropism into malapropism with disminuirte, which in this case would correspond to despise. What seems to be relevant here is that López Muñoz avoids apparently “easy” translations, like that of refer (prefer) into referir (preferir), choosing to introduce compensation as a device. López Muñoz may have considered the word preferir to be too common in Spanish to give rise to such a mistake, making it sound somehow “fake,” and possibly even revealing the presence of the translator.[15]

In this passage, out of spite, Slipslop has falsely accused Joseph of wenching to discredit him before their mistress. As usual, López de Letona translates into non-malapropism. López Muñoz combines two techniques. On the one hand, he uses M → Ø for upheld, which presumably stands for beheld. The lapse may have some connotations, as out of spite and self-interest Slipslop is not “upholding” Joseph (she is doing quite the contrary, in fact), although she knows that it would be the fair thing to do. On the other hand, López Muñoz uses again the non-M → M technique, with desfavorable [unfavourable] replacing the natural poco favorecido [ill-favoured or not too well-favoured]. It must however be said that, although incorrectly used here, desfavorable is of course an existing word. In fact, its actual meaning may reveal what has really happened and an involuntary complaint by Mrs. Slipslop, because her moves on Joseph have not been met by the expected favourable response. That is to say, Joseph has been desfavorable to her. Again, the premise for López Muñoz seems to be the search for credibility in the mistake. Therefore, a malapropism can, when necessary, be produced from a word other than the one giving rise to it in the original, and thus the connotations derived may also be different. However, these are also consistent with what has happened in the novel previously.

Before this reply by Slipslop, she has complained about her mistress’ behaviour and praised her late master, and Adams has just reminded her that she used to do quite the reverse. In this example López Muñoz makes use of resources analogous to those of the original malapropisms. On the one hand, he translates confidous into non-malapropism, but introduces a new malapropism with antecedentemente, a non-existing word similar in form to the correct anteriormente [previously]. The inappropriate suffix and the semantic similarity between lexemes (antes/anterior) add to the plausibility of the malapropism. On the other hand, the same incorrectness in the suffixation of wondersome is followed to form maravillante. For his part, López de Letona translates into non-malapropisms.

9. Quantitative analysis

A mere look at the total number of malapropisms in every text may already yield a clear picture of the strategies followed by each translator:

Table 1

Total number of malapropisms in source text and translations of Joseph Andrews

The translation of malapropisms as such, therefore, does not appear to have been a priority for López de Letona, while in López Muñoz’s version there is a decrease of 26% in relation to the ST, allowing us to conclude that the textual weighting of malapropisms is significantly lower in his translation than in the original.

Table 2

Translation techniques of malapropisms in Joseph Andrews

As seen above, the M → M technique is the one López Muñoz uses most frequently. Omissions or “non-translation” constitute nevertheless a relatively high percentage of his choices (36% adding up the techniques M → non-M and M → Ø). On the other hand, compensation (represented by non-M → M cases) amounts to a moderate percentage. It seems to play a sort of “balancing” role, and overuse is thus avoided. Moderation appears to be the rule for a technique whose limits are shown by the zero cases of Ø → M recorded. Finally, the technique that would most clearly betray the presence of a translator (footnotes) is not used at all. As for López de Letona, his strategy has mainly been the non-inclusion of malapropisms (97% of cases) in his translation.

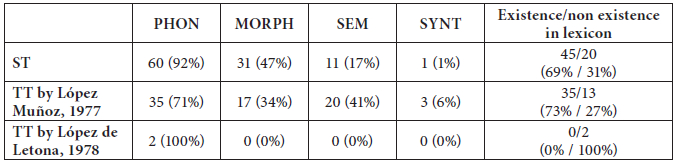

Table 3

Typology of malapropisms in ST and TT

López de Letona’s main strategy makes typological analysis of his malapropisms scarcely significant. Accordingly, as regards typology I will be focusing exclusively on López Muñoz. Although phonetic malapropisms are the most abundant in both his version and in the ST, in the latter they are more frequent in both relative and absolute terms making up 21% of the total more than in López Muñoz’s version. Conversely, semantic malapropisms as a percentage of the total are 24% more frequent in López Muñoz’s version than in the original. Malapropism type coincidence occurs in 20 cases (52% of M → M cases). When López Muñoz introduces a new malapropism with the non-M → M technique, the preferred type is the phonetic one (70% of cases), followed by the morphological and semantic types. So, the overall impression is that López Muñoz follows the ST typological pattern rather freely as regards frequency. As for the existence-in-the-lexicon criterion, analysis yields results that are proportionally quite similar, with a slight preference for existing terms in López Muñoz’s version.

Lastly, there are fewer repetitions of the same malapropism in the TT. In the ST 14 malapropisms are repeated, including the inflection of the same term (result/resulted). All are found twice, except for confidous which is repeated six times. In López Muñoz’s version seven malapropisms are repeated, all of them twice.

10. Conclusions

The first and most obvious conclusion of this study on the translation of malapropisms in Joseph Andrews is that they have been handled radically differently by the two translators. On the one hand, López de Letona chooses to overwhelmingly “ignore” them, by translating them into non-malapropisms or omitting them altogether. In his translation, malapropisms have not been assigned any functional relevance and therefore have not constituted a translation priority. Unlike López de Letona, López Muñoz makes an effort to include a large number of malapropisms in his translation, thus granting them functional relevance within the novel. Nevertheless, in his translation there are 26% fewer malapropisms than in the original English text, and consequently they have considerably less textual weight. This decrease, however, is fairly common in translations, as shown by other studies dealing with translation of wordplay (see Offord 1990 and Delabastita 1993); although reasons may vary, and may go beyond the mere structural differences between languages. In this particular case, it is not easy to pinpoint the exact reasons for the divergence in strategies pursued by the two translators. The two translations were produced in consecutive years, although they were published in very dissimilar editions. One possible (and quite tempting) explanation resides in the translators’ relative competence; but there may be more to it than that. Also to be considered is the fact that malapropisms appear in italics in the ST, so they are not likely to be overlooked; it would at least be expected for the translator to grant them some particular importance.

López de Letona had already translated demanding texts, such as Tristram Shandy, for the same publishing house. This was an important challenge, as he was the first to translate the novel into Spanish. Furthermore, his translation was broadly accepted, as it was republished at least five times between 1985 and 2005. Joseph Andrews, however, appears to have been carried out “in a hurry,” without a thorough final revision of the text. This may explain the presumed strategy of avoiding malapropisms, as they might have been considered too time-consuming, and may have posed a problem for meeting the deadline. Circumstances were quite different for López Muñoz, for whom time constraints do not seem to have been an issue (if that may ever be said about a translation!). The latter also included an abundance of footnotes and a complete study for the introduction of his version, which may have contributed to his awareness of the intricacies of the text.

As for omissions in López Muñoz, these may be revealing in terms of the tolerance of the target context to this strategy; his translation did after all receive the main award of its kind in Spain, and this may be seen as an endorsement of his work. As Delabastita (1997: 9) put it: “the translational afterlife of a text is actually an extremely rich testing ground for a study of reading strategies in connection with wordplay.” In this sense, it is noteworthy that López Muñoz’s translation has been republished as recently as 2008, while López de Letona’s never was. Perhaps omission of some malapropisms, in spite of what seems to be an overall attempt to render them, can be accounted for by turning to this statement by Offord (1997: 258): “[sometimes] producing poor wordplay in the translation is worse than producing no wordplay at all.” As stated by Delabastita (1993: 262), in wordplay language draws attention to itself and can thus pose a risk to the so-called translator’s invisibility (Venuti 1995). In this sense, López de Letona’s is an extreme case, as that risk is eliminated by avoiding the translation of malapropisms.

Additionally, the absence of footnotes may show that they are accorded a very low degree of acceptance as a strategy for the translation of malapropisms. So, other resources are preferred, and reading fluency has to be preserved above other considerations.

In some cases, when reading fluency is accorded a high priority, one of the preferred strategies is compensation, which in López Muñoz plays a balancing role. This translator, however, is careful not to overuse this strategy. These appear to be the limits of compensation in this case, together with the fact that the Ø → M technique is not employed. López Muñoz, therefore, sets limits to the degree of creative freedom in which he indulges by not adding any new textual material containing malapropisms.

Another factor, however, seems to have been at play in the translator’s resort to compensation, namely credibility in the linguistic mistake. In other words, the malapropism or the term triggering the malapropism (the word in absentia) must be perceived as complex enough to make the mistake plausible. Most of these terms in absentia are of Latin or Greek origin, and sometimes the similarity between the English terms both in praesentia and in absentia and their corresponding Spanish terms is obvious; this can make translation seem like an easy task. However, it may be argued that the register assigned to those words in English is not the same as it is in Spanish, where Latin or Greek-based terms may well be perceived as common terms. Consequently, an easy translation (i.e. refer (prefer) into referir (preferir), contract into contracto) may appear fake or artificial to the Spanish reader, thus making the translation conspicuous, a risk that is to be avoided at all costs. This would explain why López Muñoz prefers to forgo an easy translation and introduce new malapropisms that may seem more plausible to the Spanish reader.

In López Muñoz, some differences in typology have been observed, with less than half of the cases reproducing exactly the same typology of the source malapropisms. But on the whole the translation shows the same assortment of types as the original. This may be seen as evidence of the translator’s awareness of them. That is to say, types of malapropism are chosen rather freely by López Muñoz, with typological reproduction being largely dependent on the attainment of a satisfactory solution. It may then be concluded that functionality is the overriding criterion for him, with type in second place.

In López Muñoz, the most notable differences in typology as compared to the ST are the increase in the semantic category (24%) and the decrease in the phonetic one (21%). Humour being a largely subjective issue, it is certainly problematic to make inferences as to whether phonetic similarity between the words in praesentia and in absentia is the most successful feature in causing humour; were this to be true, López Muñoz’s version would have to be considered less humorous than the original. It may well be so, as it is arguable that semantic inappropriateness is not as likely to trigger the exact term in absentia in the mind of the reader, thus diluting the pleasure associated with immediate recognition. This issue, however, would have to be judged by studying the degree of similarity in the ST and the TT on a case per case basis. Be that as it may, there is no denying that there is a shift in the way Slipslop’s speech is characterised in the TT as compared to the ST.

Another noteworthy aspect is repetition of the same malapropism, which is rather less frequent in López Muñoz. Only seven malapropisms are repeated in his version, against fourteen in the ST (two times each in both texts, except confidous, which is repeated six times in the ST). As a result, it may be said that López Muñoz’s version is less consistent as regards the characterisation of Slipslop’s idiolect, since malapropism repetition makes her speech more recognisable and clearly defined.

Lastly, it may be concluded that this descriptive analysis has a bearing on the translation of malapropisms elsewhere; for as already seen, the study of López Muñoz’s Joseph Andrews sheds light on some of the main factors to be considered when translating malapropisms:

The term in absentia or word originating the malapropism in the ST;

The complexity or register of the term originating the malapropism in the target language;

The typological range of the ST malapropisms, as a host of possibilities to be taken into account by the translator, beyond the exact typological reproduction in each pair;

The analysis of connotations (hidden thoughts, desires, references within the plot, and so forth) associated with a malapropism;

The use of compensation as a potential balancing resource;

The repetition of the same malapropisms in the ST as providing consistency and cohesion in building the character’s idiolect.

Parties annexes

Appendix

Original work by Henry Fielding

Fielding, Henry (1741): An Apology for the Life of Mrs. Shamela Andrews. London: A. Dodd.

Fielding, Henry (1741-1742/1999): The History of the Adventures of Joseph Andrews And of his Friend Mr. Abraham Adams.An Apology for the Life of Mrs. Shamela Andrews. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Fielding, Henry (1743/1982): Jonathan Wild. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Fielding, Henry (1749/2005): The History of Tom Jones, A Foundling. London: Penguin

Fielding, Henry (1751/1987): Amelia. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Spanish translations and adaptations of Henry Fielding’s novels

Tom Jones (1749)

Fielding, Henry (1749/1796): Tom Jones ó El Expósito. (Translated by Ignacio De Ordejón) Madrid: Imprenta de D. Benito Cano.

Fielding, Henry (1749/1933): La historia de Tomás Jones, el expósito. (Translated by Guillermo SansHuelin) Madrid: Espasa-Calpe. (Reissued Espasa-Calpe, 2009).

Fielding, Henry (1749/1961): La historia de Tom Jones. (Translated by Enrique De Juan) Maestros ingleses II. Barcelona: Planeta. (Reissued Planeta, 1989).

Fielding, Henry (1749/1964a): Tom Jones. (Adapted by Javier Tomeo) Barcelona: Ediciones Marte.

Fielding, Henry (1749/1964b): Tom Jones. (Adapted by Juan Bautista CuyásBoira) Sant Cugat del Vallés: Delos-Aymá.

Fielding, Henry (1749/1964c): Tom Jones. (Adapted by Ramón Moix) Barcelona: Mateu.

Fielding, Henry (1749/1964d): Tom Jones. (Translated by Carlos GonzálezCastresana) Barcelona: Bruguera.

Fielding, Henry (1749/1965): Tom Jones. (Unknown abridger). Barcelona: Gassó Hermanos, S.A.

Fielding, Henry (1749/1967): Tom Jones. (Translated by María Casamar) Barcelona: Ramón Sopena. (Edition revised by Fernando Galván. Madrid: Cátedra, 1997).

Fielding, Henry (1749/1978): Tom Jones. (Translated by Mercedes Soriano) Madrid: Club Internacional del Libro.

Joseph Andrews (1742)

Fielding, Henry (1742/1977): Vida y andanzas de Joseph Andrews. (Translated by José Antonio LópezdeLetona) Madrid: Ediciones del Centro.

Fielding, Henry (1742/2008): La historia de las aventuras de Joseph Andrews. (Translated by José Luis LópezMuñoz 1978) Madrid: Alfaguara.

Jonathan Wild (1743)

Fielding, Henry (1743/2004): Jonathan Wild. (Translated by Miguel Ángel PérezPérez) Madrid: Cátedra.

Amelia (1751)

Fielding, Henry (1751/1795-1796): Historia de Amelia Booth. (Unknown translator) Madrid: Imprenta de la Viuda de Ibarra. (Reissued Barcelona: Seix-Barral, 1969).

Fielding, Henry (1751/2005): Amelia. (Translated by Esther Pérez) Mataró: Ediciones de Intervención Cultural.

Acknowledgements

The author of this article is supported by a fellowship from Generalitat Valenciana (BFPI/2009/0045).

Research funds for this article have been provided by project FFI2009-09544, funded by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation.

Notes

-

[1]

Brinsley Sheridan, Richard (1775/1979): The Rivals. London: A & C Black.

-

[2]

Oxford English Dictionary (n.d.): Malapropism. Visited on 9 September 2012. <http://www.oed>.

-

[3]

Encyclopaedia Britannica (n.d.): Malapropism. Visited on 15 April 2013. <http://www.britannica.com>.

-

[4]

Merriam-Webster Dictionary (n.d.): Malapropism. Visited on 15 April 2013, <http://www.merriam-webster.com>.

-

[5]

Encyclopaedia Britannica (n.d.): Malapropism. Visited on 15 April 2013, <http://www.britannica.com>.

-

[6]

Merriam-Webster Dictionary (n.d.): Malapropism. Visited on 15 April 2013, <http://www.merriam-webster.com>.

-

[7]

Shakespeare, William (1598-1599/1997): Much Ado About Nothing. Cambridge/New York: Cambridge University Press.

-

[8]

Smolett, Tobias (1771/1993): The Expedition of Humphry Clinker. London: J. M. Dent; Vermont: Charles E. Tuttle.

-

[9]

The chambermaid Mrs. Slipslop, from Joseph Andrews, is the most prominent malapropistic character in Fielding’s novels.

-

[10]

Fielding, fino observador de la sociedad, siguió muy de cerca la evolución de los comportamientos en su entorno sociocultural y supo identificar a aquellos grupos que eran responsables de la progresiva corrupción lingüística […]. Igualmente, como buen conocedor de las clases altas e hipócritas que introducían los cambios semánticos, construye su teoría del deterioro de la lengua y la proyecta en algunos personajes de creación literaria. Así, Mrs. Slipslop que comete abundantes malapropismos… […] La pretensión de Fielding de reflejar su actitud frente a las incorrecciones lingüísticas presentes en el lenguaje utilizado le lleva a adoptar múltiples recursos literarios […], sobre todo, el uso de las jergas y los malapropismos.

-

[11]

The Theatrical Licensing Act 1737. In: John Raithby, ed. (1811). The Statutes at Large of England and of Great Britain. Vol. IX. London: Eyre & Strahan, 526-529.

-

[12]

Richardson, Samuel (1740/1980): Pamela: or, Virtue Rewarded. Middlesex: Penguin Books.

-

[13]

Tom Jones (1963): Directed by Tony Richardson. United Kingdom: Woodfall Film Productions.

-

[14]

Sterne, Laurence (1759-1767/1975): Vida y opiniones del caballero Tristram Shandy. (Translated by José Antonio López de Letona) Madrid: Ediciones del Centro.

Sterne, Laurence (1759-1767/1976): Tristram Shandy. (Translated by Ana María Aznar) Barcelona: Planeta.

Sterne, Laurence (1759-1767/1978): La vida y las opiniones del caballero Tristram Shandy. (Translated by Javier Marías) Madrid: Alfaguara.

-

[15]

Other than for considerations on “good” or “bad” translations, I fully share Vega’s view (2004: 567) on the way translations are judged in Spain. It seems unquestionable that fluency and invisibility have traditionally been the two major requirements for a translation to be praised; and this applies not only to Spain (see Venuti 1995).

Bibliography

- Aitchison, Jean (2008): The Articulate Mammal. An Introduction to Psycholinguistics. Oxford: Routledge.

- Cuddon, John Anthony and Preston, Claire (1998): A Dictionary of Literary Terms and Literary Theory. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers.

- Delabastita, Dirk (1993): There’s a Double Tongue: An Investigation into the Translation of Shakespeare’s Wordplay with Special Reference to Hamlet. Amsterdam/Atlanta: Rodopi.

- Delabastita, Dirk (1997): Introduction. In: Dirk Delabastita, ed. Traductio: Essays on Punning and Translation. Manchester: St. Jerome, 1-22.

- Hardy, Barbara Nathan (1979): Dramatic Quicklyisms: Malapropic Wordplay Technique in Shakespeare’s Henriad. Salzburg: Universität Salzburg.

- Hatfield, Glenn W. (1968): Henry Fielding and the Language of Irony. Chicago/London: University of Chicago Press.

- Hockett, Charles F. (1973): Where the Tongue Slips, There Slip I. In: Victoria Fromkin, ed. Speech Errors as Linguistic Evidence. The Hague: Mouton, 93-119.

- Irwin, Michael (1969): Henry Fielding and the Language of Irony [Review of the book Henry Fielding and the Language of Irony ]. Review of English Studies. xx(80):507-508.

- Jespersen, Otto (1905): Growth and Structure of the English Language. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

- Offord, Malcom (1990): Translating Shakespeare’s Wordplay. In: Peter Fawcett and Owen Heathcote, eds. Translation in Performance: Papers on the Theory and Practice of Translation. Bradford Occasional Papers. Vol. 10. Bradford: University of Bradford, 101-140.

- Sánchez Rodríguez, Luis (2005): La función del malapropismo en Joseph Andrews. Anuario de Estudios Filológicos. xxviii:277-283.

- Sanderson, John (2002): La teoría de la relevancia aplicada a la traducción del malapropismo para la representación teatral. In: Marta Falces, Mercedes Díaz, and José María Pérez, eds. Proceedings of the 25th International Conference of AEDEAN. (25th International AEDEAN Conference, Granada, 2001). Granada: University of Granada (CD ROM edition).

- Schlauch, Margaret (1987): The Social Background of Shakespeare’s Malapropisms. In: Vivian Salmon and Edwina Burness, eds. A Reader in the Language of Shakespearean Drama. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins, 71-99.

- Simpson, John and Weiner, Edmund, eds. (1989): The Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Soto Vázquez, Adolfo Luis (1993): El inglés de Charles Dickens y su traducción al español. A Coruña: Universidade da Coruña.

- Soto Vázquez, Adolfo Luis (2001): Shakespeare’s Use of Malapropisms and their Reflection in Spanish Translation. Babel. 48(1):1-22.

- Soto Vázquez, Adolfo Luis (2008): Novela regional inglesa y sus traducciones al español: Henry Fielding y Walter Scott. Estudio textual y traductológico. A Coruña: Universidade da Coruña.

- Toury, Gideon (1995): Descriptive Translation Studies and Beyond. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

- Vega, Miguel Ángel (2004): De la Guerra Civil al pasado inmediato. In: Francisco Lafarga and Luis Pegenaute, eds. Historia de la traducción en España. Salamanca: Ambos Mundos.

- Venuti, Lawrence (1995): The Translator’s Invisibility. A History of Translation. London: Routledge.

Interviews

- Email interview with José Luis López Muñoz, translator, on 30 July 2009.

- Phone interview with José Antonio López de Letona, translator, on 16 September 2009.

Liste des tableaux

Table 1

Total number of malapropisms in source text and translations of Joseph Andrews

Table 2

Translation techniques of malapropisms in Joseph Andrews

Table 3

Typology of malapropisms in ST and TT