Résumés

Abstract

Despite the fact that translation teaching research has been gaining momentum over the last two decades, little has been written and therefore known about translation assessment in the teaching context. This article reports on a data-based empirical study of translation testing in China. The issues raised in it range from teachers’ attitudes towards testing to its objectives, design, contents, frequency, and its pedagogical roles. It is suggested that more research be done on translation testing, of which the first task is to develop a theoretical framework to provide guidance for translation testing practice and research. It is further recommended that translation testing be made more teaching-oriented and brought closer to the real world of professional translation.

Keywords/Mots-clés:

- translation testing,

- teachers’ attitudes towards testing,

- design of translation tests,

- pedagogical roles of translation tests,

- China

Résumé

Même si la recherche en enseignement de la traduction a eu le vent dans les voiles ces dernières années, peu de choses ont été diffusées sur l’évaluation de la traduction dans le contexte universitaire. Cet article présente une étude fondée sur des données d’évaluation de traductions en Chine. Les questions soulevées vont de l’attitude des enseignants face à l’évaluation jusqu’aux objectifs, modèles, contenus, fréquences et leurs fonctions pédagogiques. Il s’agit de développer les recherches en évaluation dont la première tâche est de développer un cadre théorique pour guider l’évaluation de la pratique et de la recherche. On recommande également que l’évaluation de la traduction soit davantage liée à l’enseignement et plus en conformité avec le monde réel de la traduction professionnelle.

Corps de l’article

Statement of the Problem

Over the last few decades, there has been a dramatic increase in the number of studies on translation and interpretation (Gile 1995; Fan 1997). Among others, the pedagogy of translation has received unprecedented attention worldwide, including the Chinese-English translation research community, since the early 1990s. With translator training gaining prominence, translation assessment and testing[1] have been naturally incorporated as an integral part of the educational environment (Cao 1996). While there has been a wealth of research on translation teaching methodology and development of teaching materials, study on translation testing and assessment can scarcely be found (Mason 1986; Ghonsooly 1993; Xu 1998). This lack of research has resulted in (1) translation testing lagging behind the progress of teaching methodology and material development, hence its incompatibility with them, (2) students’ complaints about the current practice of translation assessment (as revealed in a survey conducted by the Department of Translation, CUHK, in 1998), and (3) most importantly, teachers’ little knowledge of new development in educational measurement and language testing and thus their lack of understanding of possible alternatives of translation testing.

To change this situation, a critical inquiry into translation testing and assessment seems to be in order. In early 2000, we started a research project on translation testing at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, the purpose of which was to make a critical investigation of the current practices of translation assessment, and meanwhile, drawing on the research on educational measurement in general and language testing in particular, explore alternative methods of assessment that could better determine students’ translation competence and which would also be more teaching-oriented.

Three research questions were developed to guide the project.

What is the current situation of translation testing and assessment?

How can research on educational measurement in general and language testing in particular inform translation testing and assessment?

What alternative methods of assessment are available to teachers in order to improve translation testing and assessment?

It was also decided that the project would be divided into two phases, with Phase One focusing on understanding the current practices of translation testing and assessment and Phase Two on alternative methods of translation testing and assessment. The present paper is a report of the preliminary findings of Phase One.

The Study

The Design

Phase One of the project consisted of two parts. The first part of the study was a questionnaire survey administered to translation instructors at tertiary institutions in China. In formulating interview questions, I followed Denzin’s (1970) suggestions and made sure that the questions were clear, precise and motivating. The questionnaire comprised 27 questions altogether, falling into three parts, namely Personal Information, Teaching Context and Practices & Perceptions of Translation Testing and Assessment. The questionnaire included both open-ended questions and questions with fixed alternatives. One hundred and seventy questionnaires were mailed out and 95 completed questionnaires returned, a return rate of 55.9 percent.

As Cheung at al pointed out in their study of professional translation in Hong Kong, “while its conciseness makes it a convenient method of sampling straightforward facts and opinions, the resulting data usually cannot reveal actual social processes at work” (1993:13). Therefore, following the questionnaire survey, in-depth interviews were held with 12 of the respondents to further explore their understanding of being translation teachers, perceptions of translation testing and assessment, and their suggestions for changes in translation testing. Special attention was given to probing their perceptions of translation testing that were not reflected or captured in the questionnaire survey.

The interviews used in this study were semi-structured, which is conducted in a systematic and consistent order, but allows the interviewer sufficient freedom to digress and probe far beyond the answers to their prepared and standardized questions (Berg 1989:17). All interviews, lasting from one to two hours, were audiotaped and transcribed as soon as possible afterwards.

Data Analysis

Data analysis is not a simple description of the data collected but a process by which the researcher can bring interpretation to the data (Powney and Watts 1987). The themes and coding categories in this study emerged from an examination of the data rather than being determined beforehand and imposed on the data (Bogdan and Biklen 1992). The researcher, following the strategy of analytic induction (Goetz and LeCompte 1984; Bogdan and Biklen 1992), repeatedly read through the completed questionnaires and the interview transcripts during and after the study. In this process, recurrent themes and salient comments were identified and noted for the final report.

Participants of the Study

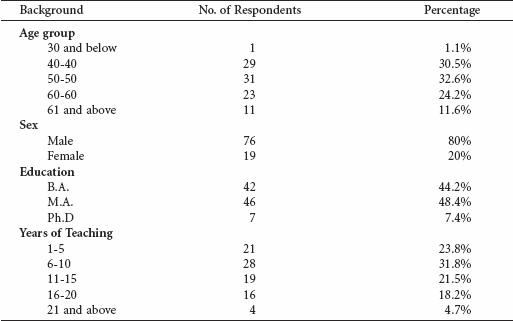

The respondents of the questionnaire survey were 95 translation teachers in tertiary institutions in Mainland China. Thirty-one of them were in their forties (32.6%), 29 in their thirties (30.5%), 23 in their fifties (24.2%), 11 above sixty (11.6%) and one below 30 (1.1%). Seventy-six of them were male (80%) and only 19 of them were female (20%). Forty-two of them were BA holders (44.2%), 46 MA holders (48.4%) and seven Ph.D. holders (7.4%). Their years of teaching translation varied from two to forty-five years, with an average of approximately 11 years and half. At the time of the study, 28 of them (31.8%) had taught translation for six to ten years, 21 (23.8%) for two to five years, 19 (21.5%) for 11 to 15 years, 16 (18.2%) for 16 to 20 years, and four (4.7%) for over 20 years. A summary of the information is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1

Background of the respondents

In selecting interview informants, I, following Patton’s “maximum variation sampling” (in Lincoln and Guba 1985:200), allowed for maximum variation in informants’ age, sex, teaching experience, teaching contexts, and the grades they taught.

Ethical Considerations

Participation in this study was on a voluntary basis. Participating teachers were informed about the study, why it was done and what would happen to the results of the study. They were also given an opportunity to ask questions and to offer suggestions. The anonymity and confidentiality of the study were emphasized. Also the right to choose to be part of the study or not and the right to opt out at any time during the study were discussed. Consent forms restating this information were signed before the study began.

Setting for the Study

Before going to the findings of the study, it is necessary to give an account of the research setting, i.e., the context of translation teaching in China, in order to situate our discussions.

Universities in China are based on a four-year system. Translation courses are offered usually in the third and fourth year in many tertiary institutions. Forty-five of the 95 surveyed teachers reported that their students were usually fourth-year students (47.4%), thirty-seven teachers reported that their students were mainly third-year students (38.9%), nine teachers reported that their students were second year students (9.5%), and four teachers reported that their students were first year students (4.2%) (see Figure 2).

In Mainland China, there is up till now only one translation department and one school of translation and interpretation, the former at the undergraduate level while the latter at the postgraduate level. Almost all translation courses or programs are offered by departments of English or departments of foreign languages. Only a small number of universities offer MAs and Ph.Ds. in translation. Among the surveyed teachers, 43 were teaching in departments of English (45.2%), 47 in departments of foreign languages (49.5%) and five in departments of French, Russian or German (5.3%) in different universities (Figure 3).

Figure 2

Students Enrolled in Translation Courses

Figure 3

Respondents’ Teaching Departments

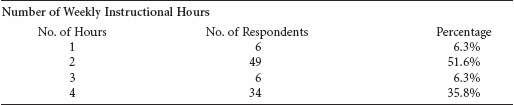

Translation, though a compulsory element, is only allocated two to four hours per week for one to four consecutive teaching terms. Among the 95 surveyed teachers, 49 teachers reported that translation was taught for two hours per week (51.6%), 34 teachers reported that translation was taught four hours per week (35.8%), and six teachers reported that translation was taught for three hours per week (6.3%) and six other teachers reported that translation was taught for one hour per week (6.3%) in their respective universities (Figure 4).

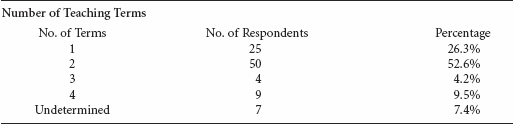

Among the 95 surveyed teachers, 50 teachers reported that translation was taught for two terms during the four year program (52.6%), 25 teachers reported that translation was taught for only one term (26.3%), nine teachers reported that translation was taught for four terms (9.5%), four teachers reported that translation was taught for three terms (4.2%), and seven teachers reported that the instruction time varied depending on availability of teachers (7.4%) (see Figure 5).

Figures 4-5

Weekly Instructional Hours and Number of Teaching Terms

Figure 4

Figure 5

In most cases, translation was taught as another skill in addition to listening, speaking, reading and writing in English or other foreign languages. Seventy-seven of the surveyed teachers (81%) reported that the translation courses they taught were one or several of the courses that English or other foreign language major students must take in their programs, fifteen teachers reported that the translation courses were one or several of the courses that translation major students must take in their programs (15.8%), and three teachers said that the translation courses were one or several of the courses that non-foreign language and non-translation major students must take in their programs.

Students take translation courses for different reasons. In most universities, students majoring in foreign languages are required to take translation courses. Translation is one of the sections in most national foreign language examinations, such as the Test for English Majors (TEM) for English major students and College English Test (CET) for non-English major students. Sixty-six of the surveyed teachers cited curriculum requirement as the reason for students taking translation courses (69.5%). Another reason was more pragmatic, that is, to become translators after graduation. Forty respondents referred to this as the reason for students taking the course (42.1%). The third reason why students took translation was to learn a foreign language well. Translation was regarded as an effective way to help with learning and acquisition of a second language. Fifty-eight respondents reported that their students took the course for the purpose of improving their overall competence in the second language (69.5%). Four respondents reported that students took translation because they were interested in the subject (4.2%) (see Figure 6).

Figure 6

Students’ Purposes for Taking Translation

Students taking translation courses worked at different jobs after graduation. Sixty-two surveyed teachers reported that some of their students became English or other foreign language teachers in tertiary institutions (65.3%); Forty-five teachers reported that some of their students became professional translators (47.4%); Thirty-seven teachers reported that some of their students became English or other foreign language teachers in secondary or elementary schools (38.9%); Thirty teachers reported that some of their students became scientists and engineers (31.6%); Fifteen teachers reported that some of their students became management personnel in foreign investment companies or government offices dealing with foreign affairs and international relations (9.5%) (see Figure 7).

Figure 7

Students’ Occupation after Graduation

Findings of the Study

As the result of my going through the completed questionnaires and the interview scripts repeatedly, the following emerged as the major themes.

The Importance of Translation Testing

The participants of the study were overwhelmingly in support of the present study on translation testing and considered it very important and worthwhile. When asked how important they thought translation testing was in the teaching of translation, 52 respondents rated it very important (54.7%), 37 respondents rated it extremely important (38.9%), four respondents rated it important (4.2%), and one respondent each rated it unimportant and not important at all (1.1%) (see Figure 8).

Figure 8

Importance of Translation Testing

Role of Testing in Translation Teaching

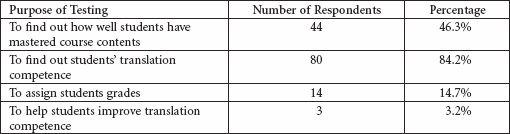

What role should testing play in translation teaching? Eighty respondents thought that the purpose of testing was to assess students’ translation competence, or to put it simply, how well students could translate up to the time of being tested. Forty-four respondents believed that the purpose was to find out how well students had mastered course contents. Fourteen teachers reported that the purpose was to fulfill the teaching requirement, that is, to assign students grades for the course. Three teachers believed that testing itself was to help students improve their translation competence. However, according to the respondents, they usually had more than one purposes for a test. In fact, most respondents reported more than one purposes for testing (see Figure 9).

Figure 9

Role of Testing in Translation Testing

Frequency of Translation Testing

The respondents also reported on the frequency of translation testing in a translation course they taught. They were told to refer to one typical translation course they were teaching if they were teaching more than one translation courses at the time of this research. Although a huge fluctuation was seen in the frequency at which translation tests were conducted across universities, ranging from nil to 38 tests and examinations per term, 53 teachers reported that they gave around one to three tests per term (55.8%), that is, they either gave a mid-term and a final test or simply a final test at the end of the course. Only 16 teachers reported that they gave four to six tests per term (16.8%). Fourteen teachers reported that they gave seven or more tests per term (14.7%). Seven teachers did not give tests but only asked students to write term papers on translation which were used as the basis for assigning them grades (7.4%) (see Figure 10).

Figure 10

Frequency of Tests

Questions Used in Translation Tests

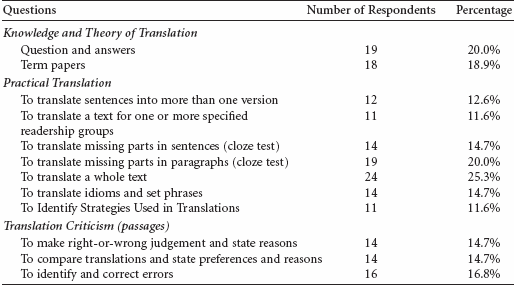

In the survey, the respondents were asked to tick from a list the kinds of questions that they had used in translation tests. The questions they used fell into four groups: questions on knowledge and theory of translation, translating sentences, translating passages and translation criticism (see Figure 11).

Figure 11

The Kinds of Questions Used in Translation Tests

The respondents were also requested to report on the test questions that they had used but were not listed in the questionnaire, the results of which are tabulated in Figure 12.

Figure 12

Other Kinds of Questions Used in Translation Tests

Satisfaction with Current Translation Testing

Seventy-three respondents reported that they were generally dissatisfied with the current situation of translation testing (76.8%). Seven teachers were extremely dissatisfied with the situation (7.4%) while ten teachers reported that they found the present situation satisfactory (10.5%). One teacher considered the current situation extremely satisfactory.

Discussions

Attitudes towards Translation Testing

The respondents were overwhelmingly supportive of this study on translation testing, in the form of active participation by completing and returning the questionnaires and offering encouraging comments. The respondents attached great importance to testing. Over ninety percent of the respondents believed that translation testing is important or extremely important and deserves much more attention than it has received so far. Two reasons might be accountable for the lack of study on translation testing despite its recognized importance. First, testing and assessment have always been difficult in almost all educational contexts. For instance, one hurdle for the highly-acclaimed Communicative Approach in second/foreign language education has been the difficulty in assessing learners’ communicative competence which the method claims to develop. As a result, this approach has been considerably limited in its application in many ESL/EFL situations (Li 1999). Likewise, translation testing is also much more difficult and complicated compared with other aspects of translation teaching. It is thus understandable that there has been little study on this topic so far. Secondly, translation teaching research is obviously very young (Kiraly 1995). Therefore, it is predictable that studies on the topic of translation testing are yet to come.

The teachers were also concerned about the current practice of translation testing. Over eighty percent of the respondents reported that they were dissatisfied or extremely dissatisfied with the current situation. But due to lack of study and little exchange of ideas, they often found themselves helpless when confronted with testing problems. As one informant said, “I know there are problems with translation testing, but there’s really not much I can do.” The teachers recognized the importance of assessment in their work, but unfortunately often felt inadequately trained in this area (Stiggins and Bridgeford 1985).

The respondents believed that the present study was timely and they seemed to value the study a great deal. As one respondent commented, “the project itself has made a difference already because the questionnaires sent out were actually calls to all teachers that translation testing is something that merits our attention.” The respondents also made interesting and constructive suggestions, including, making the findings of this study available as soon as possible, organizing at some point a conference on translation testing for exchange of ideas, and setting up a translation testing research centre with the aim to develop a database of test papers and promote translation testing research.

Goals and Objectives of Translation Testing

Translation tests tend to perform one of the following functions: evaluation of translation proficiency, diagnosis of particular areas of strength and weakness in translation proficiency, and evaluation of achievement relevant to a particular instructional unit or program. Tests can also serve to motivate students in their translation learning endeavor (or the contrary) and may be used in the evaluation of instructional programs. Therefore, assessment and testing can be roughly said to have two major purposes: to grant a license and to inform teaching. According to Hart (1994), the best kinds of assessment must support the learning of both students and teachers. As tests have a profound influence on what is taught and how it is taught, they are closely related to the teaching methodology. Therefore, in translation teaching, assessment must become an integral part, and only for the purpose of teaching and learning (Turnbill 1989; Townsend et al 1997).

However, it is found in the present study that for most teachers the predominant purpose of translation testing was to assess students’ translational competence. While approximately forty-six percent of the surveyed teachers thought that the purpose was to evaluate students’ achievement or diagnose areas of weakness and strength regarding a particular teaching unit or program, almost twice as many teachers believed that the purpose was to assess students’ translation abilities. It seems obvious that the goals and objectives of translation testing need to be adjusted so that it serves both teaching and learning.

Design of Translation Tests

A variety of tasks are in use in translation test papers today. The task used most often is to have students translate an entire text or several passages of a text. About ninety-four percent of the respondents reported that they used it frequently in translation tests. The respondents cited three reasons for this choice. First, teachers generally believe that context is important in translation and that asking students to translate an entire text or several passages is probably the best way to reflect this philosophy in testing. Secondly, it is also the teachers’ belief that having students translate an entire text or several passages can better measure students’ mastery of translation skills and methods than, say, translating a number of decontextualized sentences or phrases. Thirdly, since professional translators usually deal with entire texts or passages rather than sentences or individual words, having students translate texts or passages also brings classroom teaching closer to the real world of professional translation.

However, the surveyed teachers seemed to have overlooked the possible disadvantages of using texts or passages as testing tasks. When this kind of task is used, the number of texts that can be included in one single test paper will be highly limited. If students happen to be unfamiliar with the subject matter of the selected texts, their performance might not be a good indicator of their actual translation competence, and this will then totally defeat the purpose of such a test. Besides, when passages are chosen as testing tasks, the kinds of questions that can be included in one test paper will be again limited. Such a test paper may seem dull and uninteresting to students.

The second kind of task that is often used in translation tests, according to the respondents, is to translate sentences. About sixty percent of the respondents reported that they used it frequently. One advantage of this kind of task as test items is that more test items can be included in a test paper and a much broader range of translation techniques and strategies can be assessed in one single test. While translating passages reflects the importance of context in translation, translating sentences “highlights the importance of the accuracy in translation,” according to some surveyed teachers.

The third kind of task most frequently used in translation tests can be broadly called translation criticism. Usually, students are required to read two or more translations of the same original, which can be an entire text or several passages, identify the better or the best translation, or identify any errors, and give reasons for their choices. To complete such tasks, students need to have adequate translation competence in order to identify the errors, or to be able to tell the differences between two or more translations and determine which version is better or the best. Students also need to have a good understanding of translation strategies and methods in order to provide the reasons for their choices. The advantage of this kind of task is that, as one respondent commented, “it tests students’ translation ability as well as their understanding of translation theory. It’s a good way to enable students to link theory with practice.”

Another kind of task often used in translation testing is multiple-choice questions. They were used in assessing students’ knowledge of translation theory and their abilities in translating sentences. However, many respondents were strongly against using them at all. They argued that students could choose the right answers but might not be able to produce quality translation by themselves. Therefore, multiple-choice questions could not truly test students’ translation competence or diagnose their strengths or weaknesses after learning a particular unit. They believed that students themselves should be encouraged to gain hands-on experience with translation.

Contents of the Test

What is assessed in translation testing, according to the present study, seems to fall roughly into two major categories. The first is what is usually referred to as translation theory, taken broadly to include translation history and other general knowledge about translation. Multiple-choice questions are usually used in testing translation theory. This seems to suggest a separation between translation theory and practice in testing since it is obvious that such a recall of facts on translation theory and knowledge does little to help students’ actual translation performance. The other focus of assessment is students’ translation competence. The findings of the present study seem to suggest that all tests are obviously oriented towards measuring what is believed to be translators’ competence, i.e., what students can do in translation at the time of the test. While translation competence can be one of the aims of translation testing, it is pedagogically unconducive to have it as the only testing purpose. The best kinds of assessment support the learning of both students and teachers (Hart 1994). Therefore, we might conclude that the current translation assessment mechanism does suggest separation of testing from teaching.

Translation competence, according to Neubert (1995), consists of three kinds of competence: language competence, subject competence and transfer competence. However, the findings of the present study suggest that learners’ language competence and to a lesser extent their mastery of translation methods and strategies have been the main focus of most tests while students’ competence in intercultural communication and subject knowledge have been barely assessed at all. Emphasis has been placed on mechanical linguistic transfer instead of students’ creativity and problem-solving abilities, which are essential to a successful translator (Li, 2000).

It goes without saying that bilingual competence is essential to translators. Therefore both the foreign language and the mother tongue competence should be assessed in translation testing. However, the findings of the present study show that translation tests tend to assess students’ foreign language competence alone. Students’ mother tongue competence has seldom been assessed. Furthermore, translation tests have quite often been no more than tests of students’ reading comprehension of the original text, especially when students are required to do translation from a foreign language into their mother tongue.

In addition, most of the testing tasks have been literary translations in nature. Students who perform well in such tests may not necessarily be good translators of non-literary texts. However, in sheer volume and financial worth technical and business translation far exceeds the translation of literary texts (Kingscott 1995; Venuti 1995). Therefore, as suggested by some respondents, translation teaching and testing should include more non-literary translation tasks in order to bring testing closer to the real world of professional translation.

Grading of Translation Papers

Scoring of translation test papers is notoriously subjective and unreliable. It is the most problematic aspect in translation testing. The problem lies in the difficulty in achieving objectivity and consistency in the process of grading students’ translations. In discussing the grading of translation test papers, the respondents generally found it difficult and felt frustrated. As one respondent commented, “it is easy to set question papers, but it is very difficult to grade them.” Despite different translation quality assessment criteria or models proposed by translation scholars (e.g., House 1981; Fan 1990), none has been accepted by all. In other words, there are almost as many translation criteria as translation teachers.

Secondly, the surveyed teachers also felt that it was difficult to achieve consistence in the grading or scoring of translation tests. Over 80 percent of the surveyed teachers considered current testing, particularly the scoring and grading of students’ translations, unsatisfactory or extremely unsatisfactory. Since it is impossible to work out a set of criteria that all translation teachers will agree to in the foreseeable future or probably ever, the reliability of translation testing will always remain a problem unless radical changes take place in translation testing philosophy and practice.

Implications

More Study on Translation Testing

More efforts and resources should be devoted to research on translation testing. Testing is an important part of translation teaching and has profound influences on curricular decisions about what to teach and how to teach. However, little study has been done so far although many people have long been aware of the importance. Therefore, one of the most obvious implications of this study is that more efforts must be devoted to translation testing if translation teaching is to move a step further. While more in-depth research is to be done on aspects that have been briefly touched upon in literature on translation testing, efforts should also be made to study the aspects that have so far been largely neglected, e.g., how teachers can make better use of test results, and how testing results can be used to plan for improved testing in the future (Hamp-Lyons: 298).

Development of a Theoretical Framework for Translation Testing

A most serious problem in current translation testing practice is its haphazardness. As pointed out earlier, there has been little research on translation testing so far. Teachers might have become aware of the problems in testing but so far there has been little exchange of ideas among them, not to mention any agreement on the objectives, design and grading of translation tests. Translation teachers have each been devising their own tests and using them in their own ways. To remedy such a situation, a theory of translation testing is of paramount importance. Such a theory should provide clear guidance for the designing, administering and grading of translation testing. It should also provide principles regarding post-test application of test results to assist with translation teaching.

Linking Testing with Teaching

As an integral part of instruction, translation testing has different functions in teaching, i.e., that of providing feedback about the success of the course, reporting individual student achievement, diagnosing student learning, consolidating student knowledge prior to the next instruction unit, directing students over priorities and influencing their approach to learning and so on (Pratt 1994:106-107). Thus, assessment may be naturalistic or formal, preordinate or non-ordinate, formative or summative, norm-referenced or criteria-referenced, immediate or continuous, or assessed by the teacher or by the students. In current translation testing, assessment has been primarily used to assess learners’ translation competence, whereas other uses of assessment, which are pedagogically more valid, are largely left out. Accordingly, formal, preordinate, summative, norm-referenced, teacher administered assessment has been the predominant and often the only form of assessment, with other forms of assessment hardly used at all.

Curriculum should drive assessment, not vice versa. For this reason, our main interest should be in discovering the progress students are making with respect to the learnings we consider important. This means that we should be interested in assessing not on a calendar basis, e.g., at the end of each year, semester, or month, but on a curricular basis. The appropriate point for summative assessment, for instance, is when the student has had an adequate opportunity to learn something. Therefore, in order to make translation tests fulfill their teaching role, their diagnostic function must be stressed. Since students are likely to consider tests as reflecting the teacher’s view of what is important, the tests should obviously relate closely to the what has been taught (Alderson and Clapman 1996:185).

It is also worth mentioning that, because of its nature, it is actually very difficult to assess translation competence by using one or several formal examinations. Both teachers and students have come to see this. In a recent survey conducted by the Department of Translation, the Chinese University of Hong Kong in 1998 regarding student satisfaction over the B.A. translation program, approximately seventy percent of the students reported that they did not like summative assessment and desired more informal and formative examinations, for instance, more home and class assignments.

Improving the Accountability and Comparability of Translation Tests

Clear objectivity in translation tests cannot be completely achieved due to the complex nature of translation. Nonetheless, some predetermined rating criteria must be used to “channel” the examiner’s attention towards the factors considered most important in the communicative act of translation. The criteria chosen for general consideration should include not only the traditional set (grammar, vocabulary, fluency, and comprehension) but also the so-called criteria of communication: fluency, function and purpose, quality and amount of communication, and communication effectiveness and function. According to my experience, it is best to place emphasis on the latter group and allow the former set to qualify or explain the conclusions reached. Thus I value the extent to which an individual can reproduce the original message clearly more than his excellence in rhetoric. Style of writing, in fact, should only be considered a factor when it affects expressiveness and effectiveness of communication. Likewise, grammar and vocabulary become significant only when the accuracy of the message is affected.

The key to achieve some objectivity in translation tests is the checklist and rating scale. How one uses the chosen (and weighted) criteria in arriving at rating decisions is much in dispute. My experience suggests that it is unnecessary to compute separate scores but that intimate knowledge of the rating levels is necessary so that the rater can transfer his essentially subjective judgements to that scale efficiently. Criteria, written down as reference, are essential to maintaining the examiner’s approach to performance rating for all students. Practical knowledge of the rating scale gives the criteria a functional basis. With the foregoing in mind, a rating scale must be developed that relates directly to students.

The measurement in translation testing might have adequate reliability if we could have each translation graded by several teachers. But in reality, this is extremely difficult to achieve, limited by the time and the resources available. However, whenever possible, more than one assessor should be invited to rate each translation in order to improve the reliability of the test results.

Bringing Translation Testing Closer to the World of Professional Translation

It was found in this study that there is a considerable discrepancy between translation testing and the real world of professional translation. However, “In any assessment, it is necessary to ask, what real-world capability is being assessed?” (Pratt 1994:121). Therefore, I believe that testing should also be brought closer to translation reality. For instance, more non-literary texts should be included in translation tests since our graduates will be primarily translating pragmatic texts at work. In translation testing, some questions such as multiple-choice questions which discourage students from gaining hands-on experience in translation practice should be minimized or completely avoided. In designing translation tasks, attention should also be given to development of students’ analytic and problem-solving abilities, which are essential to successful and competent translators.

Alternatives for Translation Testing

In educational assessment, teachers and students are increasingly less satisfied with traditional standardized tests than ever before in this era of change and innovation. Alternative forms of assessment have been keenly sought. For instance, in writing assessment, many have turned to holistic assessment (Turnbill 1989) and portfolios have been widely used to document and assess students’ progress in writing (Belanoff and Dixon 1991). Others have turned to computers for assistance in assessment (McCurry and McCurry 1992). I believe this could also be the future direction for translation assessment. “We must constantly remind ourselves that the ultimate purpose of evaluation is to enable students to evaluate themselves” (Costa 1989:2). Therefore, efforts should be made in seeking ways to give students control over translation assessment instead of giving teachers the sole authority over it (McCurry and McCurry 1992; Duke and Sanchez 1994).

Conclusion

Translation testing is an important aspect of translation teaching. Teachers have generally felt the need for more research on it. Therefore, we who teach and conduct research on translation need to play a more active role in studying the issue of translation assessment. It is high time to develop and maintain translation assessment theories and practice which are in line with our teaching.

This is a preliminary study. It is mainly a description of current translation testing practice and teachers’ perceptions of them. Many issues raised herein deserve much more in-depth research. For instance, further study needs to be carried out regarding designing of testing questions, e.g., how to work out pedagogical criteria for grading students’ translations, how to assess students’ translation competence, cultural knowledge and encyclopedic knowledge, and how to enhance the validity and reliability of translation testing. All these questions await further exploration.

Parties annexes

Note

-

[1]

This article is mainly concerned with testing in the teaching context, and it is therefore different from other obviously competence-based translation tests, such as accreditation and licensing tests, though they may share some common issues. In addition, we are less interested in systemwide assessment than in the use of assessment by teachers in their classrooms.

References

- Alderson, J. C. and C. Clapman (1996): “Assessing student performance in the ESL classroom,” TESOL Quarterly.

- Belanoff, P. and M. Dixon (1991): Portfolio grading: Process and product, Portsmouth, Boynton/Cook.

- Berg, B. L. (1989): Qualitative research methods: For the social sciences, Boston, Allyn and Bacon.

- Bogdan, R. and Biklen, S. K. (1992) Qualitative research for education: An introduction to theory and methods. London: Allyn & Bacon.

- Campbell, S. J. (1991): “Towards a model of translation competence,” Meta 36-2/3, p. 329-343.

- Cao, D. (1996): Towards a model of translation proficiency, Target 8-2, p. 325-340.

- Cheung, Y., Xu, Y., Chan, S. and C. Yim (1993): Professional Translation in Hong Kong: How and by Whom, Hong Kong, Centre for Translation Studies, Hong Kong Polytechnic.

- Costa, A. L. (1989): “Reassessing assessment,” Educational leadership 46-7, p. 2.

- Delisle, J. (1981): L’enseignement de l’interprétation et de la traduction, Ottawa, Editions de l’Université d’Ottawa.

- Denzin, N. K. (1970): The Research Act: A theoretical Introduction to Sociological Methods. Chicago, Aldine Pub. Co.

- Duke, C. and R. Sanchez (1994): “Giving Students Control Over Writing Assessment,” English Journal 83-4, p. 47-53.

- Fan, S. (1990): “A Statistical Method for Translation Quality Assessment,” Target 2-1, p. 43-67.

- Fan, S. (1997): “A Historical Survey of CE/EC Translation Teaching Materials Since 1949,” presented at the Conference on Translation Teaching, Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong.

- Gentile, A. (1991): “The Application of Theoretical Constructs from a Number of Disciplines for the Development of a Methodology of Teaching in Interpreting and Translating,” Meta 36-2/3, p. 344-351.

- Ghonsooly, B. (1993): “Development and Validation of a Translation Test,” Edinburgh Working Papers in Applied Linguistics 4, p. 54-62.

- Gile, D. (1995): Basic Concepts and Models for Interpreter and Translator Training, Amsterdam/Philadelphia, John Benjamins Publishing Company.

- Goetz, J. P. and M. D. LeCompte (1984): Ethnography and Qualitative Design in Educational Research, New York, Academic Press.

- Hart, D. (1994): Authentic Assessment: A Handbook for Educators, New York, Addison-Wesley.

- House, J. (1981): A Model for Translation Quality Assessment, Tubingen, Gunter Narr.

- Kingscott, G.. (1995): “The Impact of Technology and the Implications for Teaching,” in Dollerup, C. and V. Appel (eds), Teaching and Interpreting3, Amsterdam, Benjamin.

- Kiraly, D. C. (1995): Pathways to Translation: Pedagogy and Process, Kent, Ohio, Kent State University Press.

- Lincoln,Y. S. and E. G. Guba (1986): Naturalistic Inquiry, Beverly Hills, California, Sage Publications.

- Lincoln,Y. S. and E. G. Guba (1986): “But is it Rigorous? Trustworthiness and Authenticity in Naturalistic Evaluation,” New Directions for Program Evaluation 30, p. 73-84.

- Lorscher, W. (1991): Translation Performance, Translation Process and Translation Strategies. A Psycholinguistic Investigation, Tubingen, Narr.

- Mason, I. (1987): “A Text Linguistic Approach to Translation Assessment,” in Keith, H. and I. Mason (eds), Translation in the Modern Languages Degree, London, Centre for Information on Language Teaching and Research.

- McCurry, N. and A. McCurry (1992): “Writing Assessment for the Twenty-First Century,” Computer Teacher 19, p. 35-37.

- Neubert, A. (1995): “Competence in Translation: A Complex Skill. How to Study and how to Teach it,” in Snell-Hornby, M. Pöchhacker, F. and K. Kaindl (eds) Translation Studies: An Interdiscipline, Amsterdam, Benjamin.

- Powney, J. and M. Watts (1987): Interviewing in Educational Research, London, Routledge.

- Pratt, D. (1994): Curriculum Planning: A Handbook for Professionals, FL, Orlando, Harcourt Brace Javanovich, Inc.

- Shreve, G. M. (1997): “Cognition and the Evolution of Translation Competence,” in Danks, J. H., Shreve, G. M., Fountain, S. B. and M. K. McBeath (eds) Cognitive Processes in Translation and Interpreting, London, Sage Publications.

- Tirkkonen-Condit, S. (1992): “The Interaction of World Knowledge and Linguistic Knowledge in the Processes of Translation: A Think-aloud Protocol Study,” in Lewandowska-Tomaszczyk and Thelen (eds), Translation and meaning, Part 2, Rijkshogeshool Maastricht, Faculty of Translation and Interpreting.

- Townsend, J., Fu, D. and L. L. Lamme (1997): “Writing Assessment: Multiple Perspectives, Multiple Purposes,” Preventing School Failure 41-2, p. 71-76.

- Turnbill, J. (1989): “Evaluation in a Whole Language Classroom: The What, the Why, the How, the When,” in E. Daly (ed) Monitoring Children’s Language Development: Holistic Assessment in the Classroom, Portsmouth, NH, Heinemann.

- Venuti, L. (1995): The Translator’s Invisibility: A History of Translation, London and New York, Routledge.

- Viaggio, S. (1994): “Theory and Professional Development: Or Admonishing Translators to be Good,” in C. Dollerup and A. Lingarrd (eds), Teaching Translation and Interpreting 2, Amsterdam, John Benjamins Publishing Company.

- Wilss, W. (1992): “The future of translator training,” Meta 37-3, p. 391-396.

- Wilss, W. (1996): Knowledge and Skills in Translator Behavior, Amsterdam, John Benjamins Publishing Company.

- Xu, L. (1998): “On Undergraduate Translation Assessment,” Chinese Translators’ Journal 3, p. 29-32.

Liste des tableaux

Figure 1

Background of the respondents

Figure 2

Students Enrolled in Translation Courses

Figure 3

Respondents’ Teaching Departments

Figure 6

Students’ Purposes for Taking Translation

Figure 7

Students’ Occupation after Graduation

Figure 8

Importance of Translation Testing

Figure 9

Role of Testing in Translation Testing

Figure 10

Frequency of Tests

Figure 11

The Kinds of Questions Used in Translation Tests

Figure 12

Other Kinds of Questions Used in Translation Tests