Résumés

Abstract

This article discusses the source text and reading situation of opera surtitles. It introduces opera from a multimodal viewpoint and differentiates between the dramatic text and the stage interpretation. With two versions of surtitles, it approaches two different surtitling strategies, the one that concentrates on the libretto and the other that focusses on the particular stage interpretation. As a result, the article asks if we should consider the stage interpretation to be the only appropriate source text of surtitles.

Keywords/Mots-clés:

- libretto,

- multimodality,

- multisemiotic text,

- opera,

- surtitling

Résumé

Quel est le texte de départ et quelle est la situation de lecture des sous-titres d’opéra ? Pour répondre à cette double question, l’auteure présente d’abord l’opéra dans une perspective multimodale, différenciant entre le texte dramatique et les représentations. A partir de deux versions sous-titrées, elle envisage deux stratégies de sous-titrage, l’une centrée sur le livret et l’autre orientée sur l’interprétation scénique, toujours particulière. Il en ressort que cette dernière pourrait être la seule source appropriée pour sous-titrer.

Corps de l’article

1. Approaching opera

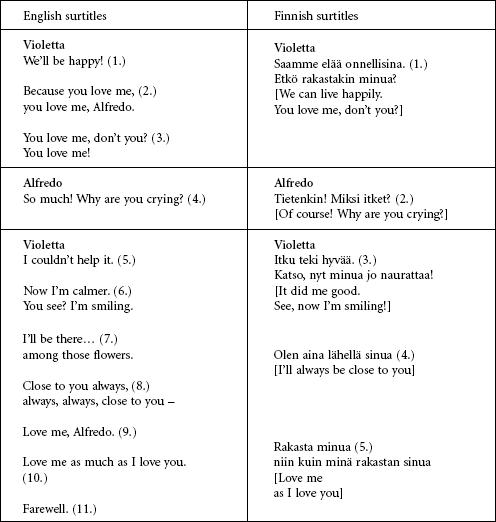

Let us first look at two versions of surtitles for a scene in Verdi’s La Traviata:

In the scene, the characters say (in singing) the following:

Violetta

Sarem felici, sarem felici,

perché tu m’ami, tu m’ami,

Alfredo, tu m’ami, non è vero?

Tu m’ami? Alfredo, tu m’ami, Alfredo, non è vero?Alfredo

Oh quanto! Perché piangi?Violetta

Di lagrime avea d’uopo.

Or son tranquilla.

Lo vedi? Ti sorrido, lo vedi?

Or son tranquilla, ti sorrido.Sarò là,

tra quei fior,

presso a te sempre, sempre,

sempre, presso a te –Amami, Alfredo. Amami quant’io t’amo.

Amami Alfredo, quant’io t’amo,

quant’io t’amo…Addio!

Apart from language, at least two factors differentiate the two versions of surtitles from each other. The first significant difference is the number of titles: the English version uses over twice as many titles as the Finnish one to tell the same story. Another difference to notice is the use of verbal repetition. The translator of the English version wants to emphasise the musical structure of the piece, or, as he states: “The captions need to make the audience aware of this stroke of genius on Verdi’s part, so they are similarly repetitive” (Dean 1999: 18). In Violetta’s first part, the English translation repeats the phrase “you love me” four times whereas the Finnish version says it only once. In Violetta’s second part, the English surtitles repeat the word “always” three times in one title; here, the Finnish version uses no repetition. By repeating specific words in his translation, the English surtitler wishes to express in writing the verbal-musical structure created by Verdi, whereas the Finnish surtitler only expresses the core contents of the message and does not imitate the verbal-musical structure.

For me, the differences imply that the surtitles approach both their source text and their target group differently. In addition to taking the verbal-musical structure into account, the English version translates the libretto more literally; besides repetition, it, for example, mentions things that the Finnish version leaves out (see e.g. title 7). From a spectator’s point of view, the reading of the English version requires much more time and attention than the Finnish one.

Surtitles are read as part of the stage interpretation in an opera performance. In the next sections, I shall discuss the character of opera as a piece of art and the peculiarities of an opera performance.

2. Multimodal view to opera performance

The richest collection of semical facts seems indeed to be that produced by the performance of an opera. The artists communicate with the audience in a variety of ways: through words, music, mime, dance, the costumes of the actors; through the music of the orchestra, the setting and the lighting on-stage and in the auditorium; through the architecture of the theatre. […] In short, a whole world here gathers and communicates for the length of several hours.

Buyssens 1943: 56; transl. by Marvin Carlson

As an art form, opera is multisemiotic and multimodal in nature. Multimodality considers all texts (verbal, non-verbal, visual, auditive) as being realised in several semiotic modes (Kress 2000: 146) and underlines the fact that within a given social-cultural domain, the ‘same’ meanings can be expressed in different semiotic modes (Kress & van Leeuwen 2001: 1). The multimodality of opera is illustrated in the quotation above. Buyssen’s statement also stresses that opera, like any theatre form, is communication that at a minimum presupposes a person A (actor) representing X (character) while S (spectator) looks on (Fischer-Lichte 1992: 7). For the communication to be successful, a shared language and a shared socio-cultural context are needed. If S does not understand the words A speaks or the gestures A makes (when representing X), the message A intends to convey does not “get through.” This is a crucial point for the function of surtitles.

3. Dramatic text vs. mise en scène

Opera is on the one hand the dramatic text, i.e. the score. It is the basis for any interpretation of the piece of art, and, by nature, the score exists in order to be interpreted. In the form of verbal-musical text and stage directions, the score expresses the intentions of the authors, that is, the composer and the librettist/s; thus it cannot be ignored in the stage interpretation. However, as Patrice Pavis notes, (Pavis 1982: 133-151) the dramatic text only suggests one possible mise en scène which should not be considered the ideal, the original or the true dramaturgical interpretation of the piece.

As a multimodal text, the operatic score is composed of verbal and visual signs (especially for those who cannot read a musical score) and it is in printed form. It is worth noting that the score is already an intersemiotic translation (see Jakobson 1959: 233; 1971: 261) of the text which, before being transcribed by the authors and “deposited” on paper, holds the status of “situational” discourse (Pavis 1982: 142).

From a reader’s point of view, the score is not tied to a specific time or place: it can be read wherever, whenever and in whatever order; the reading process has its past and future. The text is static and does not disappear if left without notice. If something is not understood, it can be re-read and studied with the help of dictionaries, music books or similar aids. Furthermore, in practice the confrontation of reader and text lacks the possibility of interaction, and these two do not share a situational context; the producers of the score are separated from the product. In addition, the reading of the score is a private event.

On the other hand, opera is a theatrical event, a performance or one particular mise en scène of the dramatic text. The mise en scène articulates the respective director’s interpretation of the dramatic text and makes the score “speak.” However, the transformation from written text to enunciation should not be considered a translation from one semiotic system into another: performance and text are of a totally different character (Pavis 1982: 145):

[W]hereas the score is based on a linguistic system of arbitrary signs (and thus must be first of all translated into signifieds before being understood), the stage is founded on iconic signs which present a figurative form of that reality of which they are the signs.

Pavis 1982: 142

From a spectator’s point of view, an opera performance is a temporal, spatial, situational and public event: a theatre performance that does not take place before an audience is not a theatre performance (see Ficher-Lichte 1992: 7). Production and interpretation of an opera performance are synchronous: the network of signs which the cultural system of opera produces cannot be separated from its producers (id.: 6), for example, the singers and the orchestra. The text has to be interpreted here and now, and the interpretation process is based on two-sided personal interaction within a shared situational context. In addition, the uniqueness, dynamism and spontaneity of the performance demand the spectator’s full attention. You can’t just rewind the text if you missed something. Furthermore, the performance dies when being born, and as such it cannot be captured, recorded or documented: no video is identical with the original performance. For more on the differences between stage and screen, see Marcia Citron (2000).

4. Surtitles as part of the performance

Surtitles are interpreted in a specific situation: the opera performance. They cannot be read in advance or bought afterwards in a printed form. In addition, the reader cannot decide how fast or in which order s/he wants to read the titles. That is decided both by the surtitler and by the stage interpretation.

Surtitles come to life in the performance and are a situational text by nature: they are only created for the performance, and without it they lose their intended meaning. It is inappropriate to read them without the performance.[1] As a result, the temporal proceeding of the stage interpretation can be seen as one meaning-making element of the surtitles, since it is crucial for their understanding to read them in a certain tempo and rhythm.[2] Another characteristic of the surtitles is their ever-changing and incomplete nature: every live surtitling is different from any other since it follows the proceeding of the stage interpretation; and if changes are made in the stage interpretation, to props or costumes for example, this should be taken into account in the translation if necessary.

My argumentation concerning surtitling is based on the following logic: if a spectator chooses to read the surtitles, the more titles there are the more time s/he needs for reading them; naturally, that time is taken away from interpreting other semiotic modes in the performance. As we know, theatrical signs are produced and read live and synchronously and must be interpreted ‘here and now.’ Furthermore, people do not come to opera to read the surtitles but to enjoy the performance as a whole. For them, surtitling is a device for approaching the other symbolic modes and as such a very functional rather than expressive text.

As a result of the characteristics of the reading situation, surtitling has a very specific function: The audience uses the surtitles for communicating with other symbolic modes used in the performance for creating meanings. In practice this means that surtitles mostly serve as a medium for the verbal content but also help to comprehend music and acting. In regard to music, which cannot be translated into words, surtitles can help the audience get more out of the musical dramaturgy, as Fmusic critic Hannu-Ilari Lampila has noted (Lampila 1997: 762). Since music can, among other functions, transcend, magnify, embellish, comment or improvise upon the libretto, it creates a kind of subtext, a musical commentary on what goes on between the interstices of dialogue and what the verbal text has not in itself realised (Lindenberger 1985: 125). Referring to Lampila’s notion, we can conclude that in order to understand the subtext, we first have to comprehend the text. Since with opera, where the verbal text has as significant a function as the other symbolic modes, the comprehension of verbal lines is always somewhat difficult, surtitling can be considered an important invention in the history of opera performance.

5. In search of the source text of surtitles

When one starts to translate a novel, it is very easy to define and indicate the source text. In surtitling, this is not the case. Does one translate the dramatic text or the stage interpretation or perhaps something else? Most of the few articles written about surtitling (Hurt & Widler 1998, Hay 1998, Dewolf 2001, Dean 1999) prefer the first option:

Übertitel [sind] Übersetzungen, die während der Aufführung parallel zum gesungenen Originaltext auf einem Display oberhalb der Bühne angezeigt werden […]. Anders als bei den Fernsehuntertiteln tritt bei Übertiteln die zusätzliche Schwierigkeit auf, dass die optische Information der Aufführung vom Originaltext abweichen kann. Der Übersetzer ist daher gezwungen, nicht nur den Ausgangstext, sondern auch die Inszenierung zu berücksichtigen […].

Hurt & Widler 1998: 262

The statement above distinguishes between the source text (Ausgangstext) and the staging (Inszenierung), which is to be interpreted that the latter is not seen as being part of the former. In addition, if the word Originaltext (in: “gesungener Originaltext,” “die optische Information der Aufführung kann vom Originaltext abweichen”) is used here in the meaning of source text (it can also mean the libretto/score in its original language), it supports the idea that surtitles are based on the dramatic text.[3]

The following quotation denounces explicitly what it considers to be the source text:

[T]he surtitles are based on the libretto and follow as closely as possible the original text and style […]. Those who denounce the literary quality of translations have little conception of the defects in the original [= libretto].

Dewolf 2001: 181

The Royal Opera House Covent Garden in London, for example, has chosen a surtitling strategy that supports the above presented conception of the libretto being the source text of surtitles. At Covent Garden, the surtitles aim at providing the audience with as objective information about the libretto as possible. This strategy is based on the company’s policy which regards the surtitles as belonging to the neutral services offered by the opera house; therefore, they must not mediate the artistic ideas of the director (Hurt 1996: 88-89). According to the company, the biggest problem with this strategy is the “lack of precision” of the titles, which the audience of Covent Garden most often also criticises (ibid: 93).

According to Hurt and according to my own experience as surtitler,[4] there is also an opposite surtitling strategy in use. It sees surtitles as being part of the Gesamtkunstwerk of opera and aims at integrating them into the particular staging (see Hurt 1996: 86). This strategy is interesting since it, in my opinion, questions the libretto’s status as the sole source text of surtitles. I approach these two strategies by returning to the translations for a scene in La Traviata I introduced in chapter 1. Referring to the differences in the number of titles and in the use of repetition, I would suggest that whereas the English version is based on the (sung) libretto, which can be seen both in its contents and its use of repetition, the Finnish version focusses on the stage interpretation. The former wants to tell the audience a detailed version of the plot and translate into written form everything that is being sung. The latter, on the contrary, aims at mediating in writing only the essential contents: for example, it does not translate Violetta’s phrase “da quei fior,” which, from the point of view of drama dynamics, is redundant. In addition, the Finnish version does not imitate the verbal-musical repetitive structure but suggests, by omitting verbal repetition, that the singers and orchestra express it clearly enough and more effectively. By concentrating on the essential verbal contents, the surtitles leave the audience more time for interpreting the signs other symbolic modes create.

With regard to repetition, it is worth noting that repetition has quite a different function in written verbal, spoken verbal and musical language. Bergström (2000: 90-91) compares the repetition used in nonmusical drama with that of operatic language in the following way:

[I]n crises when the protagonist is facing an ordeal – the loss of love, of a beloved, or of life […] we tend to say the same thing over and over again, repeating the same thoughts until the words get under the skin and make us bleed and understand. Only then are we ready to accept and meet the situation at hand. As long as the words are charged with feeling, we do not experience them as repetitious.

In opera, the repetition of a word, several words or a whole thought is one of the most common devices for structuring a dispute within the soul. It is not only an imitative device but can also correspond to the basic structure of music where a theme is established, repeated, developed and brought to a conclusion (Bergström 2000: 91). If singers treat repetition ironically, they not only destroy the idea of the drama but the music as well (id: 41). Finnish theatre and opera director Sakari Puurunen expresses similar ideas about repetition:

In my view, an aria is like a narrator’s text. If it lasts 3 to 6 minutes, it has to have something very significant to tell us: something to be compared with a story about how I felt and what I did when I saw a little boy run across a street and get hit by a car. This kind of a story can be a long one, as long as it is believable. But if the aria’s text does not carry a meaning, if it only repeats the phrase ’oh, I love you, oh, I love you,’ then it is very hollow. Love as such is, of course, a big thing, but it should be expressed in a unique way, not just by repeating the same thing over and over again.

Huovinen & Puurunen 1995: 226-227; transl. by RV

The use of repetition in surtitles clarifies the difference between symbolic modes: if the phrase ‘I love you’ is repeated in written form five to six times, it loses its uniqueness; it is not supported and varied by the singer’s expression and the emotionality of the music since the title cannot be interpreted synchronously with the verbal-musical text.

6. Several strategies for one source text?

Above, we witnessed a dichotomy of surtitling strategies.[5] But is the practice of surtitling so black and white? Do we rely solely on these two strategies? I would suggest that with surtitling, as with all translating, there are as many translating strategies as there are surtitlers. In opera, this is partly due to the fact that surtitles demand considerable reduction and selection of textual units, regardless of the assumed surtitling strategy. First of all, the number of words in the libretto is reduced to one-third, to give a rough estimate. Secondly, the verbal mode of opera is in musical-dramaturgical form – the verbal text has been matched to a melody or vice versa which results in an inseparable couple[6] – and this is enacted in singing together with orchestration, acting and scenery.

Thus, the surtitler has a large number of symbolic modes to choose from, and s/he has to select and is also relatively free to select whatever signs s/he wants. However, when choosing the relevant signs s/he always has to take into account all the modes that make up an opera performance. Even if s/he wants to choose the seemingly easy “verbal-into-verbal” translation method and concentrate on the libretto, s/he has to alter the verbal text in the case of props, for example, if they have been changed or removed. And, most significantly, s/he has to time the surtitles according to the tempo and rhythm of the performance. This means reducing the number of words and re-writing the libretto.

As a result, I want to pose the following questions: Is libretto, the dramatic text, really the source text of surtitles, as the articles cited above suggest? Or should we consider the stage interpretation[7] to be the source text, which means that we acknowledge the entity of an opera performance instead of dividing the operatic whole into text (libretto) and context (other semiotic modes)? In my opinion, I think we should. We only have to think about the function and reading situation of the surtitles and the characteristics of live performance to notice that even the most extreme as-close-to-libretto-as-possible surtitling strategy must take account of the opera’s metamorphosis from dramatic text into stage interpretation. A surtitled opera performance cannot equal a karaoke tape, in which each sung word is written in the subtitles.

To conclude my argumentation about the source text I propose that the surtitlers rely on one source text but emphasise its elements differently in their translations. This emphasis is not rigid and unchanging but varies between translations and within any single one translation, according, for example, to the way the director uses symbolic modes to create meanings.

7. Conclusion

Whether we confront a theatre performance as theatre or translation scholars, we cannot defeat it by fall since it escapes most of our analytical weapons. That notwithstanding, it is essential for all multimedia translation to observe and analyse the source text from a holistic, multisemiotic and multimodal viewpoint. Surtitling opera is about seeing and hearing, reading and writing; that applies to almost all multimedia translation. Pushing the written libretto aside and focussing on the stage interpretation brings the surtitler closer to the target group and the peculiarities of the actual reading situation. This multimodal approach requires as much verbal as visual, musical and dramatical literacy: to maintain the drama dynamics, not only a text analysis, but a continuous performance analysis is required (see Virkkunen 2002: 273-274). An opera performance is a unique event to be enjoyed, and, at best, the surtitles can become an almost unnoticeable part of it.

Parties annexes

Notes

-

[1]

The two versions of surtitles in chapter 1 illustrate how hollow they seem without their source text and the authentic situational context. Unfortunately a performance can never be presented or re-produced in written or any other symbolic form. Multimedia publications can only partially solve the problem of presentation.

-

[2]

Let us imagine a situation possibly familiar to us from TV where the source text and the subtitles proceed at a different pace. As a result, we cannot make sense of the subtitles: what are they talking about? The verbal text and the animated images tell a different story, or the same story at a different pace.

-

[3]

However, I want to point out that elsewhere Christina Hurt (1996: 87) supports the idea that surtitles should be based on the stage interpretation: “Übertitel sind integriert in den Gesamtzusammenhang der Opernaufführung und können folglich auch nicht losgelöst von diesem übersetzt werden.”

-

[4]

Since 2000, I have worked as a freelance translator/surtitler for the Finnish National Opera, the Savonlinna Opera Festival and the regional operas in Joensuu and Oulu. My previous studies on surtitling (Virkkunen 2000; 2001; 2002) are mostly based on the experience I have gathered working in the mentioned Finnish opera companies; they reflect the surtitling principles and strategies applied by Finnish surtitlers.

-

[5]

This dichotomy has been presented and discussed by Hurt (1996: 86).

-

[6]

There are, of course, cases where these two have been separated, e.g. in singable opera translations. Though, listening to translated operas only confirms the notion of inseparability.

-

[7]

I use the term stage interpretation instead of performance or mise en scène since the latter two presuppose an audience and describe a theatrical event. In one sense, however, the performance also functions as the source text since the surtitling is done live and each and every title is displayed according to the tempo, rhythm and dynamics of the stage interpretation; the translating process does not end until the last title has been projected, and it continues even after that because the source text is never complete. But, if we want to analyse the surtitling process more extensively, we should concentrate on the stage interpretation which evolves according to the director’s interpretation during the rehearsal period and as such does not require an audience (though there is always somebody, e.g. the director, following the rehearsals).

References

- Bergström, G. (2000): In Search of Meaning in Opera, Stockholm, Teatervetenskapliga institutionen.

- Buyssens, E. (1943): Les langages et le discours. Essai de linguistique fonctionnelle, dans le cadre de la sémiologie, Bruxelles, Office de publicité.

- Citron, M. J. (2000): Opera on Screen, New Haven & London, Yale University Press.

- Dean, J. (1999): The Craft of Writing English Captions. Seattle Opera Magazine, 1998/99 Season, Spring Edition, pp. 14-18.

- Dewolf, L. (2001): Surtitling operas. In Yves Gambier & Gottlieb, Henrik (eds.): (Multi)media Translation. Concepts, Practices, and Research. Benjamins Translation Library, volume 34. Amsterdam & Philadelphia, John Benjamins Publishing Company, pp. 179-188.

- Fischer-Lichte, E. (1992): The Semiotics of Theater, Translated by Jeremy Gaines and Doris L. Jones. Bloomington & Indianapolis, Indiana University Press.

- Hay, J. (1998): Subtitling and Surtitling. In Yves Gambier (ed.): Translating for the Media. Papers from the International Conference “Languages and the Media.” Berlin, November 22-23, 1996. University of Turku, Centre for Translation and Interpreting, pp. 131-137.

- Huovinen and S. Puurinen (1995): Jalkapuu. Teatterimiehen muistelmia. Porvoo, Helsinki and Juva, WSOY.

- Hurt, C. (1996): Übertitel als Teil einer Operninszenierung am Beispiel von Wagners Siegfried. In Christine Heiss & Rosa Maria Bollettieri Bosinelli (eds.): Traduzione multimediale per il cinema, la televisione e la scena, pp. 85-94.

- Hurt, C. and C. Wilder (1998): Untertitelung/Übertitelung. In Snell-Hornby, Mary et al. (eds.): Handbuch Translation. Tübingen, Stauffenburg, pp. 261-263.

- Jakobson, R. (1959): On Linguistic Aspects of Translation. In Reuben A. Brower (ed.): On Translation (Harvard Studies in Comparative Literature 23). Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press, pp. 232-239.

- Jakobson, R. (1971): Selected Writings II. The Hague & Paris, Mouton.

- Kress, G. (2000): Text as the punctuation of semiosis: pulling at some of the threads. In Ulrike H. Meinhof & Jonathan Smith (eds.): Intertextuality and the media. From genre to everyday life. Manchester & New York, Manchester University Press, pp. 132-154.

- Kress, G. and T. Van Leeuwen (2001): Multimodal Discourse. The Modes and Media of Contemporary Communication. London, Arnold.

- Lampila, H.-I. (1997): Suomalainen ooppera. Porvoo & Helsinki & Juva, WSOY.

- Lindenberger, H. (1985): Opera. The Extravagant Art. Ithaca & London, Cornell University Press.

- Pavis, P. (1982): Languages of the Stage. Essays in the Semiology of the Theatre. New York, Performing Arts Journal Publications.

- Virkkunen, R. (2001): Tekstitys oopperassa (Surtitling for the Opera). Tampere University Press.

- Virkkunen, R. (2002): Tekstitys osana oopperaesitystä (Surtitles as Part of an Opera Performance). PhLic thesis. Tampere University.