Résumés

Abstract

The aim of this paper is to present the fundamental aspects of competence-based translator training. It begins with an overview of research on Translation Competence (TC) and its acquisition (ATC), with particular emphasis on the PACTE group’s TC and ATC models, which have been validated through experimental research. It subsequently deals with four cornerstones of competence-based translator training, namely the pedagogical approach called competence-based training; specific competences in translator training; the translation task and project-based approach as a methodological and curriculum design framework; and competence assessment in translator training. The paper provides examples of how to design translator training curriculums that centre on competence development and establishes assessment guidelines.

Keywords:

- translation competence,

- acquisition of translation competence,

- competence-based training,

- translation task and project-based approach,

- assessment

Résumé

Cet article a pour but de présenter les aspects fondamentaux qui régissent une formation de traducteurs fondée sur les compétences. Nous présenterons d’abord un bref panorama des recherches relatives à la compétence de traduction (CT) et à son acquisition (ACT), en mettant l’accent sur les modèles de CT et d’ACT du groupe PACTE validés par des recherches expérimentales. Nous aborderons ensuite les quatre axes qui sous-tendent la formation des traducteurs fondée sur les compétences : l’approche pédagogique appelée formation par compétences ; les compétences spécifiques au cours de la formation des traducteurs ; l’approche par tâches et projets de traduction en tant que cadre méthodologique et de conception du cursus ; et l’évaluation des compétences en cours de formation. Nous illustrerons notre propos par des exemples de cursus pour la formation des traducteurs centrée sur le développement des compétences et proposerons des modèles d’évaluation.

Mots-clés :

- compétence de traduction,

- acquisition de la compétence de traduction,

- formation par compétences,

- approche par tâches et projets de traduction,

- évaluation

Resumen

El objetivo de este artículo es presentar los aspectos fundamentales que rigen una formación de traductores basada en competencias. En primer lugar, se presenta un breve panorama de la investigación realizada sobre la competencia traductora (CT) y su adquisición (ACT); se incide especialmente en los modelos de CT y de ACT del grupo PACTE, que han sido validados mediante investigaciones experimentales. Posteriormente, se abordan cuatro ejes que sustentan una formación de traductores basada en competencias: la línea pedagógica denominada formación por competencias; las competencias específicas en la formación de traductores; el enfoque por tareas y proyectos de traducción, como marco metodológico y de diseño curricular; la evaluación de competencias en la formación de traductores. Se aportan ejemplos de cómo elaborar diseños curriculares para la formación de traductores centrados en el desarrollo de competencias y se establecen pautas para la evaluación.

Palabras clave:

- competencia traductora,

- adquisición de la competencia traductora,

- formación por competencias,

- enfoque por tareas y proyectos de traducción,

- evaluación

Corps de l’article

Enseigner à traduire, c’est faire comprendre le processus intellectuel par lequel un message donné est transposé dans une autre langue, en plaçant l’apprenti-traducteur au coeur de l’opération traduisante pour lui en faire saisir la dynamique.

Delisle 1980: 16[1]

1. Introduction

More than three decades have passed since the Quebecker Delisle (1980) brought about a radical change in translation teaching. He was the first to advocate the need for a focus on working through the translation process appropriately in such teaching, as well as to propose learning objectives and an active methodology geared to students participating fully in their learning process. These ideas have inspired many a translator trainer. Despite progress over recent years in research into the kind of translation teaching Delisle introduced, comparisons with the situation of related disciplines (for example, language teaching) show that much remains to be done.

Due to changes in the translation profession and constant academic and professional mobility, new curriculum designs that meet society’s demands and offer scope for international harmonization are required. Furthermore, translator training cannot ignore new pedagogical models that advocate competence-based training and an integrated approach to teaching, learning and assessment.

This paper aims to lay a foundation for competence-based translator training. To that end, it firstly describes Translation Competence (the ultimate goal of such training) and its acquisition. It subsequently looks at the essential properties of competence-based training and suggests categories of specific competences for translator training. Lastly, it puts forward the translation task and project-based approach as a methodological and curriculum design framework highly suited to competence development, and proposes assessment guidelines.

2. Translation Competence and its acquisition

The study of Translation Competence (TC) and its acquisition (ATC)[2] is relatively new, compared to other disciplines.

In Applied Linguistics, the term communicative competence was coined in the mid-1960s, and the concept has long been the object of analysis (Hymes 1971; Canale 1983; Bachman 1990; etc.). In Work Psychology, the notion of professional competence has been used, with a behavioural focus, since the 1970s, and various authors (McClelland 1973; Boyatzis 1982; 1984; Spencer, McClelland and Spencer 1994; etc.) have put forward a competence-based management model that is the mainstay of competence-based human resource management. In recent years, competence-based training (see section 3) has been advocated in the Pedagogy field.

Cognitive Psychology, meanwhile, has produced a set of notions of particular relevance to the study of competences, namely declarative knowledge (know-what), operational knowledge (know-how), explanatory knowledge (know-why) and conditional knowledge (know-when) (Ryle 1949; Anderson 1983; Paris, Lipson and Wixson 1983; Wellington 1989; etc.). Also of note is the field of Expertise Studies, which examines the properties of expertise and how expert performance is acquired (Ericsson, Charness, Feltovitch, et al. 2006; etc.) from a multidisciplinary perspective.

2.1. Translation Competence

TC began to be analyzed in Translation Studies in the mid-1980s, and became prominent in the 1990s.

2.1.1. The evolution of research

In my view, the evolution of research on TC can be divided into two main periods with different characteristics (Hurtado Albir submitted b).

2.1.1.1. Early studies of Translation Competence

The initial period started in the mid-1980s (with the exception of Wilss 1976), when the first TC models were proposed. The majority of the proposals dealt with TC tangentially.

These first proposals are mostly models that break TC down into various components (Bell 1991; Neubert 1994; Kiraly 1995; Cao 1996; Hurtado Albir 1996a, 1996b; Hansen 1997; Risku 1998; etc.). They highlight that:

TC requires other competences besides those of a linguistic nature;

TC comprises different components (linguistic and extralinguistic knowledge, documentation skills, the ability to use tools, transfer competence, etc.);

The components of TC are of different types (knowledge, abilities, skills, attitudes);

There are certain differences between direct and inverse translation. Identifying transfer competence as a component of TC is characteristic of the period in question.

Few authors associated TC with expertise or emphasized the importance of its strategic component at this time. Empirical-experimental studies of written translation began in the late 1980s but only dealt with partial aspects of TC’s components rather than focusing on TC in its entirety.

2.1.1.2. Consolidation of research on Translation Competence

Since 2000, TC has become an object of study in its own right. Research on it has increased notably and acquired greater importance within translation research. In this period, TC has more often been deemed a particular type of expert knowledge that requires declarative and, predominantly, procedural knowledge, and empirical validations have been designed. Additionally, a more interdisciplinary framework has been established, with many of the proposals made being based on research in other disciplines.

Research has been carried out from a range of perspectives and with different approaches. Examples include:

The didactic perspective (Kelly 2005; González Davies 2004; Katan 2008);

The relevance-theoretic perspective (Gutt 2000; Gonçalves 2005; Alves and Gonçalves 2007);

The expertise studies perspective (Shreve 2006; Göpferich 2009);

The knowledge management perspective (Risku, Dickinson and Pircher 2010);

The professional and behavioural perspectives (Gouadec 2007; Rothe-Neves 2005).

However, empirical-experimental research aimed at validating the models put forward has been performed in only a few cases (Gonçalves 2005; Alves and Gonçalves 2007; Göpferich 2009).

2.1.2. PACTE’s research on Translation Competence

The PACTE group was established in 1997 to carry out empirical-experimental research on TC and ATC.

PACTE developed an initial TC model (PACTE 2000), which was revised following an exploratory study. PACTE (2003) defines TC as the underlying system of knowledge, abilities and attitudes required to be able to translate. TC is expert knowledge and involves declarative and predominantly procedural knowledge. It comprises five sub-competences and activates a series of psycho-physiological components:

Bilingual sub-competence: predominantly procedural knowledge required to be able to communicate between two languages;

Extralinguistic sub-competence: predominantly declarative knowledge, both implicit and explicit, about the world in general, and field-specific;

Knowledge of Translation sub-competence: predominantly declarative knowledge, both implicit and explicit, about translation and aspects of the profession;

Instrumental sub-competence: predominantly procedural knowledge related to the use of documentation resources and information and communication technologies applied to translation;

Strategic sub-competence: procedural knowledge required to ensure the efficacy of the translation process and to solve problems arising. Strategic competence is an essential component of TC as it controls the translation process by activating and creating links between all other sub-competences as they are required;

Psycho-physiological components: different types of cognitive and attitudinal components and psycho-motor mechanisms.

According to PACTE’s model, TC’s specific sub-competences are the Knowledge of Translation, Instrumental and Strategic sub-competences, which have thus been the focal point of our experimental research.

PACTE carried out an exploratory test, a pilot study and, lastly, an experiment involving 35 professional translators and 24 foreign-language teachers (see PACTE 2008, 2009, 2011a, 2011b; Hurtado Albir submitted a). Our experiment’s results have enabled us to identify characteristics and distinguishing features of TC (Table 1), as well as to verify that:

TC is an acquired competence that differs from bilingual competence;

TC affects the translation process and its product (translation quality);

the Strategic sub-competence is fundamental;

there are differences related to directionality (direct/inverse translation).

Table 1

Distinguishing features of Translation Competence (Hurtado Albir submitted a)

2.2. The Acquisition of Translation Competence

2.2.1. Studies performed

The majority of the very few ATC models proposed to date are based on observation and experience, and studies performed in other disciplines. Notable examples include the natural translation ability (a universal, innate capability of all bilinguals) put forward by Harris (Harris 1977; etc.); Toury’s process of socialization as concerns translating (1995: 241-258); Shreve’s process of development from natural to constructed translation (1997); the five-stage model (novice, advanced beginner, competence, proficiency and expertise) propounded by Chesterman (1997: 147-149), drawing on Dreyfus and Dreyfus (1986); the model based on connectionist approaches described by Alves and Gonçalves (2007); and Kiraly’s four-dimensional model of the emergence of translator competence (2013).

2.2.2. PACTE’s research on the Acquisition of Translation Competence

PACTE (2000) defines ATC as:

A dynamic, spiral process that, like all learning processes, evolves from novice knowledge (pre-translation competence) to TC. It requires learning strategies. During the process, both declarative and procedural types of knowledge are integrated, developed, and restructured;

A process in which the development of procedural knowledge – and, consequently, of the Strategic sub-competence – is essential.

A process in which the sub-competences of TC are developed and restructured.

In November 2011 we carried out an experiment with 130 Translation and Interpreting students from the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, and are currently concluding our analysis of its results (PACTE 2014, 2015, forthcoming). The data we have analyzed so far show that:

TC is an acquired competence that evolves as learning progresses;

ATC affects the translation process and its product. The way processes take place evolves, as does translation quality;

ATC involves a progression from a static to a dynamic concept of and approach to translation;

In that progression, the greatest degree of dynamism corresponds to procedural knowledge;

As TC is acquired, there is an increase in the effective combined use of internal support (cognitive resources) and different types of external resources;

Based on a comparison with our TC experiment, the new generations use documentary sources more frequently and effectively.

3. Competence-based training

A new pedagogical model called competence-based training (CBT)[4] has been advocated in recent years. As Lasnier (2000: 22) indicates, CBT is a logical continuation of objective-based learning.

In CBT, which features an integrated approach to teaching, learning and assessment, curriculum design revolves around competences. CBT has its foundations in cognitive constructivist and socio-constructivist learning theories, and it entails the operationalization of research carried out in the last 20 years with the aim of making learning more meaningful for students.

There are different definitions of competence in CBT. Lasnier proposes the following:

Une compétence est un savoir-agir complexe résultant de l’intégration, de la mobilisation et de l’agencement d’un ensemble de capacités et d’habiletés (pouvant être d’ordre cognitif, affectif, psychomoteur ou social) et de connaissances (connaissances déclaratives) utilisées efficacement, dans des situations ayant un caractère commun.

Lasnier 2000: 32[5]

This definition highlights three characteristic aspects of competences:

Know-how-to-act. Competences are not solely know-how. They involve more than just having operational knowledge;

Integration. A competence entails the integration of different types of skills and abilities (cognitive, affective, psycho-motor and/or social) and declarative knowledge (know-what). It thus includes knowing (a combination of specific discipline-related knowledge), know-how (abilities for solving practical problems) and know-how-to-be (affective and social abilities);

Use in context. Only when capable of using it effectively in a given context has an individual acquired a competence.

CBT distinguishes between specific (or discipline-related) competences, which are inherent to a particular discipline, and general (or transversal) competences, which apply to all disciplines. Each discipline must determine the general and specific competences that define the professional profile by which it is characterized. CBT is thus geared to a holistic type of training.

The Tuning Educational Structures in Europe project (González and Wagenaar 2003, 2005) identifies three types of general competence (González and Wagenaar 2003: 70ff.):

Instrumental competences: analysis and synthesis, information management, organization and planning, decision-making, problem-solving, IT skills, etc.;

Interpersonal competences: criticism and self-criticism, ethical behaviour, interpersonal skills, appreciation of diversity and multiculturalism, teamwork, etc.;

Systemic competences: learning, creativity, working independently, project management, etc.

It should be stressed that university curriculum’s specific competences are established according to the specific knowledge and abilities involved in the most common professional practices of the relevant professional profile, the description of which is thus of great importance. A professional profile is defined on the basis of the corresponding profession’s prevailing and emerging best practices. It explains profession’s main functions and the tasks through which they are fulfilled. To describe such a profile, it is necessary to analyze social needs and study the labour market to detect new fields of professional activity (emerging practices). Defining a professional profile helps identify the competences required, and they, in turn, facilitate the identification of elements of training (Yániz and Villardón 2006: 17-20).

4. Specific competences for translator training

The first step in designing any curriculum consists of establishing the specific competences to be acquired through the training to be provided, based on the relevant professional profile.

4.1. Categories of competences

Drawing on my proposal regarding learning objectives (Hurtado Albir 1996a; 1999a), I have put forward six categories of competences for translator training (Hurtado Albir 2007; 2008), which represent the first operationalization of PACTE’s TC model.

Methodological and strategic competences: applying the methodological principles and strategies necessary to work through the translation process appropriately. They are related to the Strategic and Knowledge of Translation sub-competences in PACTE’s TC model. They also entail the development of certain psycho-physiological components;

Contrastive competences: differentiating between the two languages involved, monitoring interference. They are related to the Bilingual sub-competence and are important in the context of introducing students to translation;

Extralinguistic competences: mobilizing encyclopaedic, bicultural and thematic knowledge to solve translation problems. They are related to the Extralinguistic sub-competence and are important in specialized translation;

Occupational competences: operating appropriately in the translation labour market. They are related to the Knowledge of Translation sub-competence (knowledge of aspects of professional practice);

Instrumental competences: managing documentary resources and an array of tools to solve translation problems. They are related to the Instrumental sub-competence;

Translation problem-solving competences: using appropriate strategies to solve translation problems in different text genres. They entail integrating competences and psycho-physiological components.

These categories are a means of classifying the competences that characterize a curriculum design or a particular subject (inverse translation, legal translation, technical translation, audiovisual translation, etc.). Such competences must be adapted to their pedagogical context in every case and specified for each subject. For instance, the specific competences involved in the subject Introduction to Direct Translation (taught before the different branches of specialized translation) can be expressed as follows (Hurtado Albir 2007; 2008; 2015a/b):

Applying basic methodological principles and strategies to work through the translation process appropriately;

Differentiating between the two languages involved, monitoring interference;

Mobilizing encyclopaedic, bicultural and thematic knowledge to solve basic translation problems;

Managing basic aspects related to the translation profession;

Managing basic documentary resources to solve translation problems;

Solving translation problems in non-specialized texts from different fields.

4.2. Competence operationalization

For competences to take shape, they must be operationalized so that teaching conducive to their acquisition can be planned. Many proposals have been made regarding competence operationalization (for example, Lasnier 2000: 46ff.). Mine (Hurtado Albir 2007; 2008; 2015a/b) takes the following aspects into account:

A competence’s definition (action verb + object + complement);

A competence’s elements, that is, observable behaviours that are part of it and can be used as indicators for its assessment;

Associated discipline-related content;

Possible tasks for competence acquisition;

Assessment procedures.

Examples of competence operationalization for the subject Introduction to Direct Translation can be found in Hurtado Albir 2007, 2008 and 2015a/b.

5. Methodological framework: the translation task and project-based approach

The translation task and project-based approach, which I have put forward in various publications (Hurtado Albir 1992; 1993; 1996a; 1999a; 2007; 2008; 2015a/b; etc.), is a suitable methodological framework for ATC. It has been used as a framework for a research project on designing the different subjects involved in translator training (Hurtado Albir 1999a) and for the production of the Aprender a traducir handbook series.

5.1. The translation task and project-based approach

The main aim of the task-based approach, which arose in the language teaching field (see Nunan 1989, among others), is to give curriculum design scope for the integration of its different elements, that is to say, learning objectives, content, methodology and assessment. The approach consists of instructional design as a set of tasks, and regards the task as the unit on the basis of which the learning process is organized. It notably distinguishes between preparatory tasks and final tasks, with the former laying the groundwork for the performance of the latter.

Based on the characteristics of a task identified by Zanón (1990: 22), I have defined a translation task as a unit of work that is representative of translation practice, intentionally aimed at learning to translate, and designed with a specific objective, a structure and a work sequence (Hurtado Albir 1999a: 56). Translation tasks are the cornerstone of teaching unit production and curriculum design in translator training.

Teaching units are organized into different tasks that prepare students for one or more final tasks. Such tasks can be performed in or outside classrooms, with or without guidance, individually or in groups (pairs, teams, etc.). They differ according to the nature of the competence (or indicator) and learning objectives involved. Various tasks for different types of learning objective are proposed in Hurtado Albir 1996a.

The length and number of a unit’s tasks may vary. An open task encompassing various learning objectives and featuring greater sequentiality tends to be referred to as a project. Translation projects (with larger-scale final tasks, for example translating a film) are particularly relevant to specialized subjects.

Of special importance are what Lasnier calls integrating tasks (Lasnier 2000: 148, 196), which activate one or more specific competences and at least one general competence.

5.2. Diversity in terms of instruments and tasks

A range of instruments can be used to design tasks (see Hurtado Albir 2015b: 15):

Texts: source language texts to be analyzed or translated, and/or target language texts to be analysed or corrected;

Translations to be analyzed, compared, revised or corrected;

Questionnaires of different kinds (with open or closed questions) on various matters (translation problems encountered, knowledge of translation, self-assessment, etc.);

Contrastive exercises, exercises related to documentary resources, etc.;

Worksheets of different kinds to be completed;

Information sheets on different conceptual aspects;

Support texts (in the source and target languages) on different conceptual aspects;

Translation process recordings (made with programs such as Camtasia or Translog) for analyzing pauses (indicative of translation difficulties), corrections, the types of search performed, the documentary resources used, etc.

Texts to be translated must be pedagogically useful, in other words, contain various prototypical translation problems or the specific problems students are to work on. It is important that texts be authentic, although they may sometimes be adapted for teaching purposes (summarized, modified in terms of wording or cultural references, etc.).

In the translation task and project-based approach, teaching units are organized on the basis of different kinds of tasks that progressively prepare students for the final task(s) they must complete to show that they have acquired the necessary competences and fulfilled the established learning objectives. A final task thus acts as a unit’s assessment task. Some units may not have a specific final task for assessment purposes, while others may have more than one.

Various types of task may be included in a teaching unit (Hurtado Albir 1996a; 2015b: 14):

Tasks involving translating texts. This, evidently, is the main type of task used in translation teaching, but by no means the only one.

-

Tasks involving preparation for translating texts:

Pre-translation tasks (source text analysis);

Gist translation (summarizing a source text in the target language);

Extended translation (developing a source text’s information in the target language);

Comparative translation analysis (analyzing different translations of a source text to identify correct solutions and errors);

Translation revision;

Translation correction (identifying errors).

Such tasks may be used as preparation for a unit’s final task or as final tasks in their own right. Many of them are tasks that professional translators perform.

-

Tasks for acquiring and reinforcing knowledge:

Reading support texts and information sheets;

Debates (in classrooms or online);

Analysis of parallel source and target language texts (that is, texts from the same genre and subject area);

Completing questionnaires.

These tasks allow for the acquisition of different kinds of knowledge related to a unit’s objectives, and can also be used as preparation for translating texts.

Tasks involving writing different kinds of reports, which could deal with the translation profession, a translation process, a translation process recording (featuring a student’s own or another translator’s process), contrastive source and target language difficulties (catalogue of fundamental differences), etc.

Of particular importance are translation reports (commented translation), which provide information on the process followed when translating a text, the problems encountered, the documentary resources used, etc. While translations only give a lecturer information on the product of a student’s translation process, translation reports offer an insight into the process itself and the student’s ability to undertake it appropriately. Translation reports have a dual function, in that they not only enable lecturers to gain such an insight but also make students aware of the translation process, thus helping them reflect on their learning process and monitor its evolution.

5.3. Preparing teaching units

5.3.1. Sequencing in teaching units

The first step in preparing teaching units is to decide how they are to be distributed within a course; in other words, to decide on the learning sequences and the progression to be established.

Lasnier defines a learning sequence as “un regroupement cohérent de tâches intégratrices et d’activités d’apprentissage visant l’intégration d’un ensemble de compétences et l’appropriation de contenu disciplinaire ayant un caractère commun” (Lasnier 2000: 211)[6]. Sequencing thus involves bringing competences and content with shared characteristics together.

When establishing a progression, the knowledge and abilities a student needs to be able to acquire new knowledge and abilities must be taken into consideration. A progression in terms of competences and competence indicators should therefore be established. Units that require the integration of competences and, consequently, include integrating tasks should be grouped at the end of the progression.

Tables 2, 3 and 4 contain examples of sequencing in teaching units from the Aprender a traducir handbook series.

Ten teaching units for the first stage of the subject Introduction to Direct Translation (Table 2) are established in Hurtado Albir (2015a/b). The first of them is a diagnostic unit designed to provide the lecturer with information on students’ characteristics, as well as to prompt students to reflect on what they know and their expectations in relation to the teaching of the subject. In the final unit students assess their own learning process and the teaching activity. They also repeat certain tasks from the first unit so that they can see and reflect on their achievements. One of the units (no. 5) is contrastive in nature. Each unit includes a self-assessment task.

Table 2

Teaching units for Introduction to Direct Translation (Hurtado Albir 2015a/b)

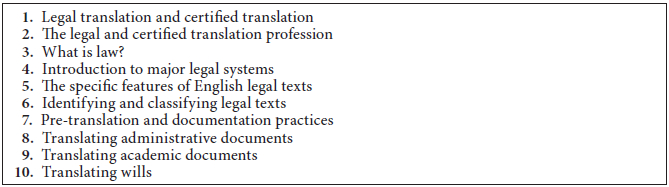

Borja (2007) proposes ten teaching units for a legal translation course (Table 3). The first seven units combine content and abilities related to legal translation and serve as preparation for translating texts from various legal genres.

Table 3

Teaching units for a legal translation course (Borja 2007)

Jiménez (2012) puts forward a dozen teaching units for an interpreting course (Table 4). The first eight units combine different content and abilities related to interpreting and serve as preparation for carrying out the activity in different forms.

Table 4

Teaching units for an interpreting course (Jiménez 2012)

5.3.2. Designing teaching units

In my opinion, the following should be taken into consideration when designing a teaching unit:

Its function within the set of teaching units that make up a course;

The learning objectives to be fulfilled, which are related to competence indicators;

The (general and specific) competences, including indicators, to be worked on. In the case of competences developed in various units, it is necessary to establish the progression that should occur from one unit to the next in terms of indicators;

Content associated to the competences involved;

-

The unit’s tasks. The following must be specified for each task:

its objective;

the instruments to be used (texts, worksheets, support texts, etc.) and the teaching environment involved (classroom-based / non-classroom-based sessions, IT and documentary resources, etc.);

task performance guidelines, including the steps to be followed and group dynamics, which should vary (individuals, pairs, the whole class, etc.) to foster cooperative work;

the assessment procedure (generally formative assessment in this case).

Complementary tasks or tasks to be performed after the final task may also be included sometimes.

The unit’s assessment (instruments and procedure). A unit’s final task tends to be its assessment task, although there may be more than one assessment task. Each unit thus requires an assessment rubric (see section 6). It is important that self-assessment tasks be included to encourage students to reflect on what they have learned through the unit. Self-assessment can revolve around the unit’s learning objectives.

Table 5 contains an example of the structure of a teaching unit for the subject Introduction to Direct Translation(French-Spanish). The featured unit deals with the translation profession (see Table 2, unit 3).

Table 5

Design of the teaching unit The translation profession (Hurtado Albir 2015a/b)

This unit has five preparatory tasks and one final task.

Task 1. Read a French text about professional translators’ competences and answer questions on it in Spanish;

Task 2. Fill in worksheets on the different types of translator (texts translated, fields of work and employment status); types of brief and translation tasks; and characteristics of the translation of different text genres;

Task 3. Read an introductory text on the Fédération Internationale des Traducteurs and answer questions in Spanish. Fill in a worksheet on professional guilds and associations of translators;

Task 4. Read a text by the Société Française des Traducteurs on problems in the translation profession in France and answer questions in Spanish;

Task 5. Read an extract from the Charte du traducteur and fill in a worksheet in Spanish on translators’ rights and duties. Use information from professional guilds and associations to fill in a worksheet on codes of ethics, remuneration for translations, etc.

As many of the unit’s tasks involve reading in French and reformulating essential ideas in Spanish, students also learn to identify information and transfer it from one language to another. As mentioned previously, the final task (writing a report in Spanish in this case) is the unit’s assessment task. There is also a self-assessment task requiring students to appraise themselves in relation to the unit’s learning objectives.

6. Competence assessment in translator training

In CBT, assessment is regarded as a tool for learning rather than as a mere grading system.

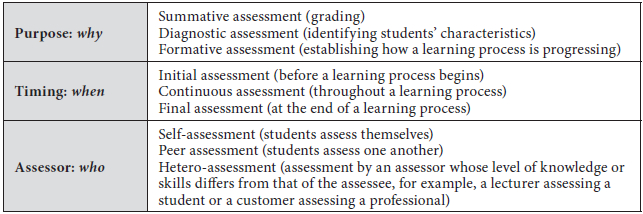

There are different types of assessment, and they can be classified by purpose, timing and assessor (Table 6).

Table 6

The different types of assessment (Galán-Mañas and Hurtado Albir 2015)

I feel that competence assessment in translator training must include all the above types of assessment. Additionally, it should seek to (Hurtado Albir 2007; 2008; 2015b: 16-17):

Assess the product and the process. Both the result of performing tasks (a translation, a revision, a report, etc.) and the process followed in doing so should be assessed. To that end, it is necessary to work with assessment tasks and instruments which provide information on problems identified, approaches to solving them, the documentary resources used, etc.;

Assess knowledge, abilities and attitudes. For that purpose, a variety of assessment tasks and instruments which provide information of different kinds must be used. Different assessment strategies with a dynamic, multidimensional approach are thus required;

Apply assessment criteria, which act as a grading guide for lecturers and make students aware of what is expected of them. Assessment rubrics are important in that regard, as their descriptions of criteria and quality levels make it possible to appraise assessment task performance, simplify providing students with feedback, and allow for self-assessment and peer assessment;

Attribute great importance to formative assessment. Such assessment is aimed at obtaining information on a learning process, so as to make students aware of their progress and enable lecturers to evaluate their teaching activity. Tasks involving the appraisal of what students have learned must therefore feature constantly;

Promote student self-assessment, in other words, encourage students to reflect on and appraise their own learning process. As future professionals, they must be capable of such appraisal for process enhancement purposes. Student self-assessment is also important from a lecturer’s perspective, as it provides information on a student’s perception of their own learning process, as well as on possible flaws in teaching activity. Every unit thus ought to include self-assessment tasks (which also help students learn to perform such assessment), such as activities involving reports, worksheets or questionnaires;

Promote assessment from different perspectives. In addition to lecturers assessing students and students assessing themselves, it is necessary, in the interests of cooperative learning, to foster peer assessment, involving students appraising one another’s work so as to learn from their classmates’ correct solutions and errors. This is conducive to more feedback.

The most common assessment task in translation teaching is translating texts, an activity that can provide information on different competences and indicators, including a student’s command of the target language, comprehension of the foreign language involved, and ability to solve translation problems. However, translating a text only gives information on translation’s product (the student’s chosen solutions) in a specific case. It does not offer a sufficient insight into the extent of the students’ TC, as it reveals nothing about the process they have followed, the problems they have identified, the (internal and external) strategies they have used or their implicit knowledge of translation. Other complementary assessment tasks that furnish further information on students are therefore necessary.

All instruments and tasks that can be used to prepare teaching units (see section 5.2) allow for summative and formative assessment alike (see Martínez Melis and Hurtado Albir 2001; Hurtado Albir 2007; 2008; 2015b: 16-22; Galán-Mañas and Hurtado Albir 2015). The most suitable instruments and tasks depend on the competence indicators to be assessed in each case.

6.1. Competence assessment instruments

Possible assessment instruments include:

Texts to be translated. To provide reliable information, texts must contain prototypical translation problems corresponding to each level of TC (novice, intermediate, etc.) and related to the objectives and competences to be assessed;

Questionnaires, which may be of different kinds, for example on knowledge of aspects of translation, on translation problems in a text, self-assessment questionnaires, learning process assessment questionnaires, etc.;

Reflective diaries, which are personal reports in which a student can record their experiences related to their learning process, both in and outside the classroom, as well as to the teaching they receive (content, materials, progression, etc.). Such diaries may take the form of blogs, making them accessible to other students and the lecturer;

Reports, which may be of different kinds. Students should provide information on a task they have performed (a translation, a debate, a group activity, etc.) or on their learning process;

Translation process recordings. A recording (made with programs such as Camtasia or Translog) of a student’s on-screen activity while they translate can be used as a complementary assessment instrument (an alternative or a complement to a translation report), as it reflects their translation process. Such recordings can be used for grading purposes or for self-assessment, peer assessment or formative assessment;

Student portfolios. A student portfolio contains productions chosen by a student to illustrate their progress over a given period. The student must select and reflect on pieces of work they have produced which show what they have learned during a course. It is important that the student’s reasons for their choices and a self-assessment report on their learning process be included. A student portfolio should thus feature work (translations, revisions, questionnaires, glossaries, etc.) corresponding to a range of tasks (final or otherwise) from different teaching units, possibly with corrections of any errors made and the student’s thoughts on the relevant tasks; an explanation of the student’s choices; and a final self-assessment report. Portfolios are an excellent competence assessment instrument as they allow for the integration of various (specific and general) competences;

Rubrics. Every task requires a rubric as a guide to its assessment. Rubrics indicate how marks are to be assigned by describing the aspects to be appraised and performance levels, making it clear what is expected of students.

6.2. Competence assessment tasks

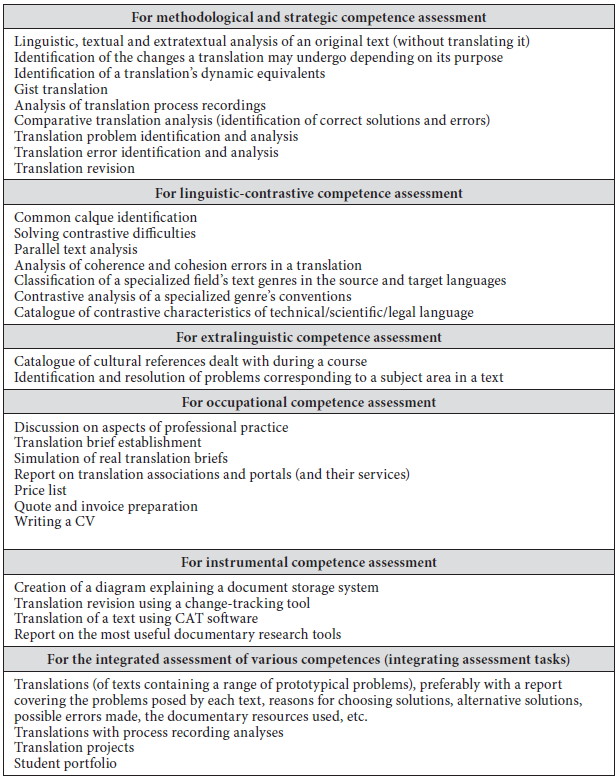

Assessment tasks vary depending on the competences and competence indicators to be appraised. Table 7 contains examples of such tasks, organized according to the specific competences they can be used to assess.

Table 7

Examples of assessment tasks (Galán-Mañas and Hurtado Albir 2015)

It is important to ensure diversity where assessment tasks are concerned so as to be able to appraise the various components of students’ TC, as well as to allow for their different learning styles. Diversity is also linked to progression, as assessment tasks should differ according to the stage of the learning process taking place.

When it comes to correcting tasks, it is advisable to promote peer assessment. Students can exchange their completed translations, worksheets or questionnaires and correct one another’s work. Alternatively, a lecturer can select certain translations (for example, the three best and the three worst) for students to correct. The goal is not to assign grades but rather to learn, so such practices are formative.

The assessment of group tasks should include an appraisal of how well each group has worked as a team. This might involve students writing a report covering the following (Hurtado Albir 2015b: 19):

Planning: meetings, deadlines established and time envisaged;

Workload distribution and coordination;

Meetings held and their respective purposes;

The time devoted to the task as a whole and to each activity it involved;

Incidents: any problems (logistical, teamwork-related, etc.) that arose and the solutions adopted (if applicable);

A teamwork appraisal: workload distribution, the performance of each activity involved, cooperation and communication between group members, time management, etc.;

Suggested improvements (if applicable).

6.3. Assessment criteria. Assessment rubrics

Assessment tasks and instruments should be chosen, first and foremost, on the basis of the competence indicators to be assessed. Each such task requires specific assessment criteria and a rubric, which act as a guide to its assessment.

Rubrics are marking guides that describe the aspects of a task (or of a learning objective or competence) to be appraised and performance levels, making it possible to gauge how well the aspects in question have been tackled. Rubrics explain what is expected of students, facilitate the provision of feedback, and allow for self-assessment and peer assessment. For a rubric to fulfil its purpose, it must establish different performance levels for each aspect to be assessed, forming a grading scale (poor/good/ excellent; poor/insufficient/sufficient/good/excellent; from 0 to 5 or 10; etc.), and specify the acceptable number of errors for each level of the scale.

It is important that rubrics be made available to students before they carry out the corresponding tasks, so that they are aware of the criteria on the basis of which they will be assessed and know what is required of them.

6.3.1. Translation assessment

This section deals with correcting errors and assessing translation quality.

6.3.1.1. Correcting errors

It is a best to use correction criteria when correcting translations. Table 8 contains an example of standard translation correction criteria, which should be adapted to the kind of translation being dealt with. Errors are divided into three categories (Hurtado Albir 1996a; 1999b), specifically errors related to the meaning of the original text; errors related to expression in the target language; and pragmatic errors, that is to say mistakes liable to prevent the translation fulfilling its purpose (in terms of its brief and target audience).

Table 8

Error correction criteria (Hurtado Albir 2015b: 20; 2015a: 216-217)

The seriousness of an error depends on its significance in relation to the text as a whole (it may affect a key idea or a large section of the text); its significance in terms of textual coherence (it may cause a high degree of incomprehensibility, for example); and the extent to which it changes the information contained in the original text. Combinations of errors are common (for example, lexical and morphosyntactic errors, or a wrong sense or nonsense stemming from poor expression).

Where correcting translations is concerned, students’ ability to spot their own errors and find acceptable solutions for themselves ought to be fostered. To that end, rather than simply giving out correct solutions, a lecturer should help students identify each error they make, along with its nature and cause, with a view to remedying it (improving their source or target language skills, their ability to use documentary resources, their analytical skills, etc.). Translation correction criteria can be a source of such help, and it is therefore important that students be aware and make use of them. This enables the lecturer to offer a diagnosis rather than a solution when correcting a translation, leaving the student to find the latter for themselves. The student can then go back to their translation, rectify their mistakes and resubmit it (or include it in their student portfolio).

Establishing a progression in terms of correcting errors is a good practice. At the beginning of the learning process, it is advisable to focus particularly on opposite sense, wrong sense, nonsense, the addition and omission of information, and linguistic and textual errors.

6.3.1.2. Translation assessment rubrics

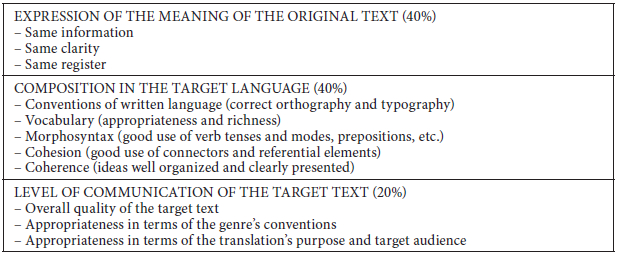

Table 9 contains an example of a standard translation assessment rubric, which should be adapted to the kind of translation being dealt with and the pedagogical context. The rubric revolves around three main considerations, namely the expression of the meaning of the original text, composition in the target language and the level of communication of the target text. As indicated previously, it is important to establish different performance levels, in the form of a grading scale, for each aspect to be assessed.

Table 9

Translation assessment rubric (Hurtado Albir 2015b: 21)

To assess translation quality, it is also necessary to establish a progression where criteria and their weighting are concerned. At the beginning of the learning process, for instance, register of language is not a key issue and a lower degree of importance (10%) could be attributed to the target text’s level of communication.

6.3.2. Other examples of assessment rubrics

As mentioned previously (see section 6.2), there are other possible assessment tasks in translation teaching besides translating texts. Rubrics must therefore be produced for all such tasks.

Some examples of rubrics that could be used in the subject Introduction to Direct Translation are provided below. It is worth reiterating that a rubric must establish different performance levels, in the form of a grading scale, for each aspect to be assessed if it is to be effective.

6.3.2.1. For assessing a translation with a report and a brief to be specified (Table 10)

This is the final task of the unit on solving translation problems in different text genres (see Table 2, unit 9). Students have to translate a text, establishing a feasible translation brief for themselves, and write a report on their translation (covering translation problems posed by the text, the documentary resources used, their reasons for choosing solutions, alternative solutions, the time spent on the task, possible errors made, etc.).

Table 10

Rubric for assessing a translation with a report and a brief to be specified (Hurtado Albir 2015b: 173)

6.3.2.2. For assessing a final self-assessment report (Table 11)

As the final task of the self-assessment unit (see Table 2, unit 10), students have to write a final self-assessment report on what they have learned in the subject. The rubric can also be used to appraise other self-assessment reports.

Table 11

Rubric for assessing a self-assessment report (Hurtado Albir 2015b: 177)

7. Conclusions

My aim in this paper has been to present the fundamental aspects of competence-based translator training, dealing with matters related to Translation Competence and its acquisition, and to translation teaching.

I have sought to highlight the importance of training future translators on the basis of competences, and of those competences being designed in such a way as to familiarize students with professional practice.

I have also looked to show that the translation task and project-based approach is a suitable methodological framework in that regard, as it allows for the integrated development of general and specific competences, and that it entails the following benefits (Hurtado Albir 2007; 2015b: 13):

It makes generating situations related to professional activity and carrying out authentic tasks possible;

It provides an active methodology centred on students, in which they learn to translate by performing tasks;

It leads to a form of teaching that revolves around working through processes. Preparatory tasks enable students to assimilate the processes they must activate to successfully complete the final task ahead of them. They grasp principles, learn to solve problems and acquire strategies to that end;

It provides a flexible curriculum design framework that is open to modifications and student participation;

It allows for elements of training methodologies such as problem-based learning, case studies, cooperative learning and situated learning to be integrated into task design.

Lastly, I have endeavoured to show that competence-based translator training requires new assessment procedures through which all the competences that make up Translation Competence can be appraised. With that in mind, I have put forward guidelines for undertaking such assessment.

I hope my proposals contribute to progress in translation teaching that places students in the centre of the translating operation so that they can understand its dynamics, as Delisle taught us many years go.

Parties annexes

Biographical note

Amparo Hurtado Albir is full professor at the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona’s (UAB) Departament de Traducció i Interpretació since 1999. She has also taught translation studies and French to Spanish translation at the Escuela Universitaria de Traductores e Intérpretes of the UAB, at the École Supérieure d’Interprètes et de Traducteurs (ÉSIT) of the Université Sorbonne Nouvelle – Paris 3, at the Facultat de ciències humanes i socials of the Universitat Jaume I (UJI) in Castellón de la Plana (Valencia), and at the Facultat de Traducció i d’Interpretació of the UAB. Moreover, she is a professional French to Spanish translator and holds a Ph.D. in Translation Studies from the ÉSIT. She has directed research projects on translation pedagogy and translator competence acquisition at the UJI and the UAB. She is the principal investigator of the PACTE (Procés d’Adquisició de la Competència Traductora i Avaluació) research group, which has conducted experimental research on translation competence acquisition in written translation since 1997.

She is the author of numerous publications on translation theory, translation pedagogy, and translation competence, namely: La notion de fidélité en traduction (Paris: Didier Érudition, 1990); Enseñar a traducir. Metodología en la formación de traductores e intérpretes (ed.) (Madrid: Edelsa, 1999); Traducción y Traductología. Introducción a la Traductología (Madrid: Cátedra, 2001/2011; 5th revised edition); and Aprender a traducir del francés al español. Competencias y tareas para la iniciación a la traducción (Edelsa: Universitat Jaume I / Madrid: Castellón, 2015). She has also published articles in Meta.

Notes

-

[1]

“Teaching someone how to translate means teaching the intellectual process by which a message is transposed into another language; that is, placing the student in the centre of the translating operation so that he can understand its dynamics” (Delisle, Jean 1988: 3).

-

[2]

See Hurtado Albir 2010 and submitted b for a more detailed explanation of these concepts and the evolution of research on TC.

-

[3]

In PACTE, we distinguish between a static (linguistic and literal) and a dynamic (textual, interpretive, communicative and functionalist) concept of translation.

-

[4]

See Hurtado Albir 2007 and 2008 for further information on CBT and its application to translation teaching.

-

[5]

“A competence is a complex form of know-how-to-act resulting from the integration, mobilization and organization of a combination of (cognitive, affective, psycho-motor and/or social) skills and abilities and (declarative) knowledge used efficiently in situations with common characteristics” (Translation: Paul Taylor).

-

[6]

“A coherent grouping of integrating tasks and learning activities geared to the integration of various competences and the appropriation of discipline-related content with common characteristics” (Translation: Paul Taylor).

Bibliography

- Alves, Fabio and Gonçalves, José Luiz (2007): Modelling translator’s competence: relevance and expertise under scrutiny. In: Yves Gambier, Miriam Shlesinger and Radegundis Stolze, eds. Translation Studies: Doubts and Directions. Selected Papers from the IV Congress of the European Society for Translation Studies. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 41-55.

- Anderson, John Robert (1983): The Architecture of Cognition. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Bachman, Lyle F. (1990): Fundamental Considerations in Language Testing. London: Oxford University Press.

- Bell, Roger T. (1991): Translation and Translating. London: Longman.

- Borja, Anabel (2007): Estrategias, materiales y recursos para la traducción jurídica. Aprender a traducir, no. 3. Castellón/Madrid: Universitat Jaume I/Edelsa.

- Boyatzis, Richard E. (1982): The Competent Manager: A Model for Effective Performance. New York: Wiley-Interscience.

- Boyatzis, Richard E. (1984): Identification of Skill Requirements for Effective Job Performance. Boston: Mcber.

- Canale, Michael (1983): From communicative competence to communicative language pedagogy. In: Jack C. Richards and Richard W. Schmidt, eds. Language and Communication. London: Longman, 2-27.

- Cao, Deborah (1996): Towards a model of translation proficiency. Target. 8(2):325-340.

- Chesterman, Andrew (1997): Memes of Translation. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Delisle, Jean (1980): L’analyse du discours comme méthode de traduction. Ottawa: Université d’Ottawa.

- Delisle, Jean (1988): Translation: An Interpretive Approach. (Translated by Patricia Logan and Monica Creery) Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press.

- Dreyfus, Hubert L. and Dreyfus, Stuart E. (1986): Mind over Machine. The Power of Human Intuition and Expertise in the Era of the Computer. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Ericsson, K. Anders, Charness, Neil, Feltovitch, Paul J., et al. (2006): The Cambridge Handbook of Expertise and Expert Performance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Galán-Mañas, Anabel and Hurtado Albir, Amparo (2015): Competence assessment procedures in translator training. The Interpreter and Translator Trainer. 9(1):63-82.

- González Davies, María (2004): Undergraduate and postgraduate translation degrees: Aims and expectations. In: Kirsten Malmjkaer, ed. Translation as an Undergraduate Degree. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 67-81.

- Gonçalves, José Luiz (2005): O desenvolvimiento da competência do tradutor: em busca de parâmetros cognitivos. In: Fabio Alves, Célia Magalhães and Adriana Pagano, eds. Competência em tradução: cognição e discurso. Belo Horizonte: Editora da UFMG, 59-90.

- González, Julia and Wagenaar, Robert G., eds. (2003): Tuning Educational Structures in Europe. Final Report. Phase One. Bilbao: Universidad de Deusto.

- González, Julia and Wagenaar, Robert G., eds. (2005): Tuning Educational Structures in Europe II. Bilbao: Universidad de Deusto.

- Göpferich, Susanne (2009): Towards a model of translation competence and its acquisition: The longitudinal study TransComp. In: Susanne Göpferich, Arnt L. Jakobsen and Inger M. Mees, eds. Behind the Mind: Methods, Models and Results in Translation Process Research. Copenhagen: Samfundslitteratur, 12-38.

- Gouadec, Daniel (2007): Translation as a Profession. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Gutt, Ernst-August (2000): Issues of translation research in the inferential paradigm of communication. In: Maeve Olohan, ed. Intercultural Faultlines. Research models in Translation Studies I: textual and cognitive aspects. Manchester: St. Jerome Publishing, 161-179.

- Hansen, Gyde (1997): Success in translation. Perspectives: Studies in Translatology. 5(2):201-210.

- Harris, Brian (1977): The Importance of Natural Translation. Working Papers in Bilingualism. 12:96-114.

- Hurtado Albir, Amparo (1992): Didactique de la traduction des textes spécialisés. Actes de la 3ème Journée ERLA-GLAT. Lexique spécialisé et didactique des langues. Brest: UBO-ENST, 9-21.

- Hurtado Albir, Amparo (1993): Un nuevo enfoque de la didáctica de la traducción. Metodología y diseño curricular. In: Roser Gauchola, Claude Mestreit and Manuel Tost, eds. Les langues étrangères dans l’Europe de l’Acte Unique. Barcelona: ICE de la Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, 239-252.

- Hurtado Albir, Amparo (1996a): La enseñanza de la traducción directa ‘general.’ Objetivos de aprendizaje y metodología. In: Amparo Hurtado Albir, ed. La enseñanza de la traducción. Estudis sobre la traducció, no. 3. Castellón: Universitat Jaume I, 31-55.

- Hurtado Albir, Amparo (1996b): La cuestión del método traductor. Método, estrategia y técnica de traducción. Sendebar. 7:39-57.

- Hurtado Albir, Amparo, ed. (1999a): Enseñar a traducir. Metodología en la formación de traductores e intérpretes. Madrid: Edelsa.

- Hurtado Albir, Amparo (1999b): La iniciación a la traducción directa. In: Amparo Hurtado Albir, ed. Enseñar a traducir. Metodología en la formación de traductores e intérpretes. Madrid: Edelsa.

- Hurtado Albir, Amparo (2007): Competence-based curriculum design for training translators. The Interpreter and Translator Trainer. 1(2):163-195.

- Hurtado Albir, Amparo (2008): Compétence en traduction et formation par compétences. Traduction, Terminologie, Rédaction. 21(1):17-64.

- Hurtado Albir, Amparo (2010): Competence. In: Yves Gambier and Luc van Doorslaer, eds. Handbook of Translation Studies. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 55-59.

- Hurtado Albir, Amparo (2015a): Aprender a traducir del francés al español. Competencias y tareas para la iniciación a la traducción. Aprender a traducir, no. 6. Castellón/Madrid: Universitat Jaume I/Edelsa.

- Hurtado Albir, Amparo (2015b) Aprender a traducir del francés al español. Competencias y tareas para la iniciación a la traducción. Guía didáctica. Aprender a traducir, no. 6. Castellón/Madrid: Universitat Jaume I/Edelsa.

- Hurtado Albir, Amparo, ed. (submitted a): Researching Translation Competence. PACTE Group. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Hurtado Albir, Amparo (submitted b): Translation and Translation Competence. In: Amparo Hurtado Albir, ed. Researching Translation Competence. PACTE Group. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Hymes, Dell (1971): On Comunicative Competence, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Jiménez, Amparo (2012): Primeros pasos hacia la interpretación inglés-español. Aprender a traducir, no. 4. Castellón/Madrid: Universitat Jaume I/Edelsa.

- Katan, David (2008): University training, competencies and the death of the translator. Problems in professionalizing translation and in the translation profession. In: Maria Teresa Musacchio and Geneviève Henrot, eds. Tradurre: Formazione e Professione. Padova: CLEUP, 113-140.

- Kelly, Dorothy (2005): A Handbook for Translator Trainers. Manchester: St Jerome.

- Kiraly, Don (1995): Pathways to Translation. Pedagogy and Process. Kent: The Kent State University Press.

- Kiraly, Don (2013): Towards a View of Translator Competence as an Emergent Phenomenon: Thinking Outside the Box(es) in Translator Education. In: Don Kiraly, Silvia Hansen-Schirra and Karin Maksymski, eds. New Prospects and Perspectives for Educating Language Mediators. Tübingen: Gunter Narr, 197-224.

- Lasnier, François (2000): Réussir la formation par compétences. Montreal: Guérin.

- Martínez Melis, Nicole and Hurtado Albir, Amparo (2001): Assessment in Translation Studies. Meta. 46(2):272-287.

- McClelland, David (1973): Testing for competencies rather than for intelligence. American Psychologist. 28:1-14.

- Neubert, Albrecht (1994): Competence in translation: a complex skill, how to study and how to teach it. In: Mary Snell-Hornby, Franz Pöchhacker and Klaus Kaindl, eds. Translation Studies. An Interdiscipline. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 411-420.

- Nunan, David (1989): Designing Tasks for the Communicative Classroom. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- PACTE (2000): Acquiring Translation Competence: Hypotheses and methodological problems in a research project. In: Allison Beeby, Doris Ensinger and Marisa Presas, eds. Investigating Translation. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 99-106.

- PACTE (2003): Building a Translation Competence model. In: Fabio Alves, ed. Triangulating Translation: Perspectives in Process Oriented Research. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 43-66.

- PACTE (2008): First results of a Translation Competence experiment: Knowledge of translation and Efficacy of the translation process. In: John Kearns, ed. Translator and Interpreter Training. Issues, Methods and Debates. London: Continuum, 104-126.

- PACTE (2009): Results of the validation of the PACTE Translation Competence model: Acceptability and Decision-making. Across Language and Cultures. 10(2):207-230.

- PACTE (2011a): Results of the validation of the PACTE Translation Competence model: Translation project and Dynamic translation index. In: Sharon O’Brien, ed. Cognitive Explorations of Translation. London: Continuum, 30-53.

- PACTE (2011b): Results of the Validation of the PACTE Translation Competence model: Translation problems and translation competence. In: Cecilia Alvstad, Adelina Hild and Elisabet Tiselius, eds. Methods and Strategies of Process Research: Integrative Approaches in Translation Studies. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 317-343.

- PACTE (2014): First Results of PACTE Group’s Experimental Research on Translation Competence Acquisition: The Acquisition of Declarative Knowledge of Translation. In: Ricardo Muñoz Martín, ed. Minding translation. Con la traducción en mente. Special issue 1. MonTI. Monografías de Traducción e Interpretación:85-115.

- PACTE (2015): Results of PACTE’s Experimental Research on the Acquisition of Translation Competence: Acceptability and Decision-making (Translation Process Research Workshop 4, Las Palmas, 15-17 January 2015).

- PACTE (forthcoming): Results of PACTE’s Experimental Research on the Acquisition of Translation Competence: the Acquisition of Declarative and Procedural Knowledge in Translation. The Dynamic Translation Index. Translation Spaces. 4(1).

- Paris, Scott G., Lipson Marjorie Y. and Wixson Karen K. (1983): Becoming a strategic reader. Contemporary Educational Psychology. 8:293-316.

- Risku, Hanna (1998): Translatorische Kompetenz. Kognitive Grundlagen des Übersetzens als Expertentätigkeit. Tübingen: Stauffenburg.

- Risku, Hanna, Dickinson, Angela and Pircher, Richard (2010): Knowledge in translation practice and translation studies: Intellectual Capital in Modern Society. In: Daniel Gile, Gyde Hansen and Nike K. Pokorn, eds. Why Translation Studies Matters. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 83-96.

- Rothe-Neves, Rui (2005): A abordagem comportamental das competências: aplicabilidade aos estudos da tradução. In: Fabio Alves, Célia Magalhães and Adriana Pagano, eds. Competência em tradução. Cognição e discurso. Belo Horizonte: Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, 91-107.

- Ryle, Gilbert (1949): The Concept of Mind. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- Shreve, Gregory M. (1997): Cognition and the Evolution of Translation Competence. In: Joseph H. Danks, Gregory M. Shreve, Stephen B. Fountain, et al., eds. Cognitive Processes in Translation and Interpreting. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, 120-136.

- Shreve, Gregory M. (2006): The deliberate practice: translation and expertise. Journal of Translation Studies. 9(1):27-42.

- Spencer, Lyle M., McClelland, David C. and Spencer, Signe M. (1994): Competency assessment methods: history and state of the art. New York: Hay/McBer Research Press.

- Toury, Gideon (1995): Descriptive Translation Studies – and beyond. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Wellington, Jerry (1989): Skills and Processes in Science Education. London: Routledge.

- Wilss, Wolfram (1976): Perspectives and limitations of a didactic framework for the teaching of translation. In: Richard W. Brislin, ed. Translation. New York: Gardner, 117-137.

- Yániz, Concepción and Villardón, Lourdes (2006): Planificar desde competencias para promover el aprendizaje. Bilbao: Universidad de Deusto.

- Zanón, Javier (1990): Los enfoques por tareas para la enseñanza de las lenguas extranjeras. Cable. 5:19-27.

Liste des tableaux

Table 1

Distinguishing features of Translation Competence (Hurtado Albir submitted a)

Table 2

Teaching units for Introduction to Direct Translation (Hurtado Albir 2015a/b)

Table 3

Teaching units for a legal translation course (Borja 2007)

Table 4

Teaching units for an interpreting course (Jiménez 2012)

Table 5

Design of the teaching unit The translation profession (Hurtado Albir 2015a/b)

Table 6

The different types of assessment (Galán-Mañas and Hurtado Albir 2015)

Table 7

Examples of assessment tasks (Galán-Mañas and Hurtado Albir 2015)

Table 8

Error correction criteria (Hurtado Albir 2015b: 20; 2015a: 216-217)

Table 9

Translation assessment rubric (Hurtado Albir 2015b: 21)

Table 10

Rubric for assessing a translation with a report and a brief to be specified (Hurtado Albir 2015b: 173)

Table 11

Rubric for assessing a self-assessment report (Hurtado Albir 2015b: 177)

10.7202/003624ar

10.7202/003624ar