Résumés

Abstract

Translators deploy a range of skills and draw on different types of knowledge in the exercise of their profession, but are some skills and knowledge types more important than others? What is the ideal combination nowadays? This study aims to investigate the relative importance of the different skills and knowledge that translators need in the specific context of translation at inter-governmental organizations. A survey was conducted of over 300 in-house translators and revisers working at over 20 inter-governmental organizations and with 24 different languages among them. The survey consisted of two questionnaires: one on the importance of different skills and knowledge, the other on the extent to which skills and knowledge are found lacking among new recruits. The results confirm that translators need more than language skills: in addition to general knowledge and in some instances specialized knowledge, they need analytical, research, technological, interpersonal and time-management skills. Correlating the findings of the two questionnaires produces a weighted list of skills and knowledge that can be used as a yardstick for adjusting training programmes and recruitment testing procedures in line with empirically identified priorities. The methodology should also be applicable to the identification of skill sets in other professions and contexts in which new recruits are closely observed, such as in-house interpreting.

Keywords:

- translation competence,

- skills,

- knowledge,

- training,

- inter-governmental organizations

Résumé

Dans l’exercice de leur profession, les traducteurs sont amenés à faire preuve de toute une gamme d’habiletés et à puiser dans différents types de connaissances, mais en y a-t-il de plus importantes que d’autres et quelles sont-elles ? La présente étude vise à examiner l’importance relative des différentes habiletés et connaissances nécessaires aux traducteurs dans le contexte spécifique des organisations intergouvernementales. Une enquête a été effectuée auprès de plus de 300 traducteurs et réviseurs employés à l’interne par plus de 20 organisations intergouvernementales, et parlant au total 24 langues différentes. L’enquête était fondée sur deux questionnaires : le premier portait sur l’importance de différentes habiletés et connaissances, le second, sur celles qui étaient jugées insuffisantes chez les nouvelles recrues. Les résultats ont confirmé que les traducteurs ne pouvaient se contenter de compétences linguistiques. Ils doivent, en plus de posséder des connaissances générales et, dans certains cas, des connaissances spécialisées, faire preuve d’habiletés analytiques, technologiques et relationnelles, et ils doivent savoir effectuer des recherches et bien gérer leur temps. Grâce au recoupement des réponses aux deux questionnaires, une liste pondérée d’habiletés et de connaissances a été dressée, laquelle peut servir de référence pour ajuster les programmes de formation et les procédures d’évaluation lors du recrutement, conformément aux priorités définies de manière empirique. Cette méthodologie devrait également pouvoir s’appliquer à l’identification d’ensembles de compétences dans d’autres professions et contextes, dans lesquels le travail des nouvelles recrues fait l’objet d’une attention particulière, comme dans le cas des interprètes travaillant à l’interne.

Mots-clés :

- compétence traductionnelle,

- habiletés,

- connaissances,

- formation,

- organisations intergouvernementales

Corps de l’article

1. Introduction

Translators clearly deploy a range of skills and draw on different types of knowledge in the exercise of their profession, but which skills or knowledge types are more important than others? Is extensive knowledge of languages more important than the ability to use dictionaries? Is the ability to punctuate sentences correctly more important than solid grounding in economic theory? Greater understanding of the skill-set required would be of benefit not only to translators themselves but also to those who train and employ them, and ultimately to Translation Studies as a discipline and to the profession itself.

Research into what it takes to translate well, which has generally come to be referred to as “translation competence,” has so far concentrated on broadly categorizing skills and knowledge types in order to create a framework for translator training. The study presented here approaches the subject from a different angle and in a particular context: that of recruitment at inter-governmental organizations (IGOs). Rather than contemplating the broad needs of translation graduates about to embark on their careers, the study aims to identify the specific needs of IGO translation services. The first step was to identify the relative importance of the skills and knowledge that IGO translators use (through an “impact questionnaire”) and to employ this as a point of departure for drawing up the candidate profile that organizations should be looking for in their selection procedures. Complementary data was obtained on the relative scarcity of the various components of that profile among new recruits (through a “recruits questionnaire”), and then the findings of the two questionnaires were correlated to produce a weighted listed of skills and knowledge that has implications for recruitment and training at IGOs. Over 300 translators, revisers and heads of service working at 20 IGOs participated in the survey, and the preliminary findings are presented here. The article closes with a brief discussion of the implications of the study and suggestions for further research.

1.1. Translation competence and translation at inter-governmental organizations: a review of the literature

Translation Studies scholars have mainly limited their exploration of translation competence to multi-componential models on which to base translator training. These range from traditional three-part competence models that distinguish a source-language processing component, a target-language processing component, and a strategic component of some kind, such as those of Bell (1991), Cao (1996), Hatim and Mason (1997) and Nord (2005), through to complex models involving 48 separate skills and knowledge types grouped into six “competences” (EMT 2009). The differing conceptualizations, definitions and levels of specification of these models, as well as their proliferation, have been commented on by Orozco and Hurtado Albir (2002), Pym (2003), Arango-Keeth and Koby (2003), Way (2008) and Angelleli (2009). The lack of empirical study devoted to these models has been noted by Waddington (2001) and bemoaned by PACTE (2008), who, together with Campbell (1991), have begun to make some inroads in this regard by producing hard data on the relations between certain components of their own models.

No empirical research seems to have been done, however, into the relative importance of the components of translation competence. Nor, apparently, has a methodology been devised for doing so. And that applies to any context, let alone the rather hermetic world of IGO translation. This is probably because the underlying driver of the discussion of translation competence in Translation Studies has been the need or desire to design and justify translator training programmes. As Pym notes, “[i]n most cases, the complex models of competence coincide more or less with the things taught in the institutions where the theorists work” (Pym 2003: 487). For syllabus planning or justification purposes, the catalogues of competencies loosely grouped under various headings serve as frames of reference. The concerns and interests of academic institutions are not necessarily the same as those of IGO human resources officers, however, and from the IGO recruitment perspective, what is needed is not a catalogue, but a shopping list in which skills and knowledge types are prioritized on the basis of the empirical analysis of the organization’s needs.

So what are the needs of IGOs as far as the profile of new recruits is concerned? Considering the enormous volume of translation work that IGOs handle and the hordes of translators they employ, it is rather surprising that so few studies have been made of IGO translation. This could be the result of lack of interest in the subject among translation scholars, whose reputation for ivory-tower attitudes is such that whole books are published on the issue. Consider, for example, Chesterman and Wagner’s Can Theory Help Translators? A dialogue between the ivory tower and the wordface (2002) and Baer and Koby’s Beyond the Ivory Tower. Rethinking translation pedagogy (2003). It could also be the result of reluctance on the part of IGO translation services to encourage enquiry into their workings. This might in turn stem from the confidential nature of some of the documents IGOs handle, time limitations and other practical constraints, the obligation of staff to protect the image of the IGO, a fear of tarnishing a reputation for high standards of excellence, or a combination of all these and other, unknown factors. In any case, the literature on IGO translation seems to have been produced mainly by those who are or were insiders, such as Koskinen (2000; 2008) and Wagner, Bech and Martinez (2002) from the European Commission’s Directorate-General for Translation, and by those working, if not with IGOs, then with large institutions: Mossop from the Canadian Government’s Translation Bureau (1988; 2001), and Williams (1989) who has worked with the same Bureau as a consultant. To supplement the scholarly literature, we have also examined publications and statements issued by IGOs (e.g., EMT 2009; European Commission 2009; Sekel 2008; Hindle 1965/1984). These works provide insights into the nature of translation work at IGOs, what shapes their approach to translation and the expectations of professional translators but, as in the case of the literature on translation competence, these works do not attempt to establish the relative importance of the components of the set of skills and knowledge required.

2. Methodology

2.1. Main Hypothesis and Definition of Terms

The aim of the study is to identify the translator profile components that IGOs need to look for and to rank them by their importance, particularly from the recruitment perspective. The main hypotheses tested were quite simple:

H1: Some components of translation competence are more important than others in IGO translation;

and

H2: Some components of translation competence are more often lacking than others among new recruits at IGOs.

where:

Components of translation competence refers to the skills and knowledge needed to produce translations that meet required standards. Knowledge is understood as information assimilated through learning, and skills are understood to be abilities that have been developed through training or experience.

Important refers to two vital aspects of the work of IGO translation services: their productivity and their reputation. Translators with the right set of skills and knowledge ideally produce more error-free translations, errors being features of translations that need to be corrected because they undermine the communicative aims of the organization or harm its reputation. Errors may be produced by defective judgment, deficient knowledge or carelessness. The number of errors translators produce has an impact on the productivity of the translation service: the fewer errors there are in the translations, the less revision work they generate and the greater the productivity of the service. Revisers are not infallible, however, and not all translations get revised: the seriousness of errors, defined in terms of the degree to which they harm the prestige of the organization, also needs to be taken into account. IGOs therefore want to find translators who have the skills and knowledge needed to minimize both the quantity and the seriousness of the errors that can be generated in the translation process, in other words, the translators who will have the least negative (or the most positive) impact on the productivity and the reputation of the IGO.

IGOs refers to inter-governmental organizations, which are understood to be organizations comprised mainly of sovereign States, usually referred to as member States. NATO, the United Nations and all its bodies, the various entities of the European Union, the Organization of American States, the OECD and the International Committee of the Red Cross are all examples of IGOs.

New recruits are translators who have been working for the organization for less than one year.

2.2. The design of the survey

Competence cannot be measured directly, but only through product and process analysis, i.e., through the manifestations and displays of that competence. Text analysis, however, can only suggest the skills and knowledge that translators apply when they translate; it cannot rank them in order of importance. Process analysis, meanwhile, is not practical on a large scale as a research method. The remaining way to find out about the skills and knowledge used in IGO translation is to consult the people with the greatest first-hand experience in using and observing their application and repercussions and hence the greatest awareness of their relative importance to the organization. A survey was therefore chosen as the data collection tool.

First, a questionnaire was designed for translators, revisers and heads of IGO translation services in which they would be asked to rate, on a five-point Likert scale, the impact that different skills and knowledge types have on the effectiveness of the translations produced by the organization. “Effective translations” were defined as those that achieve the communicative aims of the organization and protect its image. This will be referred to as the impact questionnaire and it can be found in Annex 1.

As input for translator training or preparation for work at IGOs, the ranking of skills and knowledge types by respondents to the impact questionnaire is useful. To identify recruitment priorities, however, the findings would need to be correlated with data on the relative scarcity of these same skills and knowledge types among new recruits. A high-impact skill or knowledge type that was already being found in abundance through current recruitment procedures (e.g., knowledge of French vocabulary in the case of English translators) would not have the same implications for recruitment as a high-impact one that was not being found in great quantities (e.g., knowledge of unconventional weapons). A second questionnaire was therefore designed for revisers and heads of IGO translation services, as those most familiar with the skills and knowledge of new recruits (self-report data on supposedly former shortcomings being interesting but less valuable). It asks them to rate, also on a five-point Likert scale, the frequency with which new recruits lack different skills and knowledge types. This will be referred to as the recruits questionnaire and it can be found in Annex 2.

The list of skills and types of knowledge presented for rating in both questionnaires was drawn up on the basis of the broad categories identified in the literature on translation competence and the specific skills and knowledge suggested by the review of the literature on IGO translation, as well as on the basis of the feedback from the two pilots that were conducted at one IGO prior to the survey. Two revisers participated in the first pilot, and three translators and four revisers in the second.

The base list of 40 skills and knowledge types presented for rating in the questionnaires is given below. It should be borne in mind that the purpose of the study was to obtain a hierarchy of skills and knowledge types as input for the design of text-based translation tests. Consequently, the level of specificity for the text-production skills is greater than for other types of skill, and interpersonal and other skills and knowledge types that do not lend themselves to text-based testing were excluded. The numbers alongside each skill or knowledge type are those used to identify them in the research. Short descriptions are used for the sake of space. For the full descriptions used in the questionnaires, see Annex 1 or 2. Also for convenience, the following acronyms have been used: SL for source language, TL for target language, SC for source culture, TC for target culture, ST for source text and TT for target text.

Knowledge for comprehension: Knowledge of: (1) the SL, (2) different varieties of the SL, (3) the SC, (4) the subject, and (5) the organization;

Analytical skills: The ability to: (6) understand complex topics, (7) master new subjects quickly, (8) work out the meaning of obscure texts, (9) detect inconsistencies contradictions, nonsense, etc. (10) detect logical, mathematical or factual errors, and (28) ensure the coherence of the TT;

Target-text production skills and knowledge: Knowledge of: (12) TL spelling, (14) TL punctuation rules, (13) the finer points of TL grammar, (23) TL varieties and (24) the TC. (11) An extensive vocabulary in the TL. The ability to (15) produce idiomatic translations, (16) produce translations that flow smoothly even when the ST does not, (17) select and combine words in the target language to capture the exact and detailed meanings (nuances) of the ST, (20) convey the ST message clearly, (21) convey the intended effect of the ST, (25) tailor language to the reader, (22) achieve the right tone and register, (19) produce an elegantly written target text regardless of how elegantly written the source text is, (18) recast sentences in the target language (to say the same thing in different ways), and (27) ensure the completeness of the TT;

Research skills: The ability to track down sources to: (30) understand the topic, (29) check facts, (31) mine reference material for accepted phrasing and terminology, and to (32) judge the reliability of sources;

Computer skills: The ability to: (33) type accurately and fast, work with (39) more than basic Word functions, (37) translation memory software, and (40) Excel and PowerPoint, and to (38) make effective use of terminology tools;

Other skills: The ability to: (34) maintain quality under pressure, (35) explain translation decisions, (36) follow complicated instructions about what to do with a text, and (26) adhere to in-house style conventions.

Respondents were also asked in both questionnaires to report and rate any other skills or types of knowledge not presented in the base list. Questions on text-processing responsibilities, editing and revision practice were included to contextualize findings about some of the skills and knowledge types. Being able to create pie charts in Excel is of little importance, for example, if translation services have a graphic design department that does it for them. And the importance of being able to translate poorly written originals depends on how systematically source texts are edited. Direct questions to obtain information on the expectations of new recruits at the IGOs were also included to contextualize the findings for the purposes of recruitment test design. A high frequency rating in the recruits questionnaire (i.e., the suggestion that a skill or type of knowledge is often lacking) might not be relevant if the skill or knowledge type in question can be developed after recruitment through training or in-house experience. Knowledge of the organization and in-house spelling rules, for example, can usually be mastered on the job.

2.3. The survey respondents

To reach the largest possible number of translators and revisers at IGOs, the backing of the International Annual Meeting on Language Arrangements, Documentation and Publication (IAMLADP) was sought and obtained. IAMLADP is a forum and network of managers of international organizations employing conference and language service providers, mainly translators and interpreters. The questionnaires were prepared in electronic format and sent out in February 2010. Respondents received an e-mail inviting them to complete the questionnaires online, and data were collected over a period of three months. The sample population was relatively homogeneous inasmuch as the respondents worked in the same domain, had similar academic profiles and had all passed similar recruitment examinations. The final realized sample included 165 completed impact questionnaires, of which 163 were usable, and 157 completed recruits questionnaires, of which 153 were usable. The answers from all the usable questionnaires were included in the analysis.

The impact questionnaire was completed by 7 heads of unit, 27 revisers and 129 translators from over 24 bodies of the United Nations (UN), the European Union (EU) and other organizations.[1] Translators working in a wide range of language combinations (24 different languages) participated. The recruits questionnaire was completed by 128 revisers and 25 heads of service from over 20 bodies of the United Nations, the European Union and other IGOs.[2] The results are based on the work of new recruits revised by revisers working with 22 languages among them.

3. The results of the questionnaires

3.1. The results of the impact questionnaire: the relative impact of skills and knowledge types

The mean impact ratings for the skills and knowledge types presented in the impact questionnaire are shown in Table 1. Ratings were awarded in response to the question:

For the purposes of this survey, effective translations are those that achieve the communicative aims of the organization and protect its image. How large is the impact of the following skills and knowledge types on the effectiveness of translations at your organization? 1 = extremely small; 5 = extremely large; N/A = not applicable because the skill or knowledge is not required.

Table 1

Impact ratings of selected skills and knowledge types[a]

(Response count and mean rating)

where TT = target text; TL = target languages; SL = source language; ST = source text. Descriptions of skills and knowledge have been abbreviated for the sake of space. For the full descriptions, see the impact questionnaire in Annex 1.

Being able to make sure that all the content of the original is relayed in the translation is apparently the most important skill translators need to have at IGOs. Although a rather fundamental aspect of the translator’s task in any context, it may assume particular importance in certain IGO settings such as committee meetings, in which participants are working from parallel language versions and any omissions (or unnecessary additions for that matter) may incur comment, confusion and delays and hence embarrassment and costs. Being able to express ideas clearly in the target language and having sound knowledge of the source language are also unsurprisingly rated as highly important assets. Ensuring coherence, i.e., internal consistency within each translation and all the documents produced by their translation services, is another understandable priority in IGO translation services. Translations are the written records of the institution’s workings. Possibly more unexpected is the fact that analytical skills are among those rated as being highly important (mean rating of 4.5 or above). The ability to work out obscure passages in the source text and the ability to detect inconsistencies, contradictions, nonsense, unintended ambiguities, misleading headings, etc., are ranked 7th (mean rating 4.64) and 14th (mean rating 4.54), respectively. This may be explained by the need to translate unedited source texts. The importance of being able to maintain quality even when working under pressure of time (ranked 12th) reflects another common aspect of IGO translation work, especially when servicing meetings.

It should be noted that even the skills and knowledge types at the bottom end of the ranking produced by the impact questionnaire are not considered unimportant. On a scale of 1-5, a rating of 3 or more suggests the skill or knowledge type is at least of some importance. This applies to 38 of the 40 included in the list. The only two to which it does not apply are the ability to detect mathematical errors and the ability to work with Excel and PowerPoint, which were also reported as not required at all by about 12% of respondents. In other words the vast majority of skills and knowledge types presented for rating were considered to have an impact of the effectiveness of IGO translation work.

The hierarchy reflects the opinions of 163 translators, revisers and heads of unit working in over 20 translation services. As such it provides an indication of the relative importance that professional translators working for inter-governmental organizations collectively attach to the skills and knowledge required on the job. As Kelly notes, professional considerations are one of the factors that should define the learning objectives of training programmes (Kelly 2005: 22-28). This information could therefore be of interest to translators thinking of working for IGOs and translator training institutions. The fact that knowing how to spell correctly is apparently more important than being able to work with translation memory software, for example, may come as a slight surprise, as might the low ranking of cultural knowledge.

3.1.1. The additional skills and knowledge reported in the impact questionnaire as being needed on the job: an insight into translation at IGOs

The optional question in the impact questionnaire on other skills and knowledge required was answered by 48 people (29% of respondents), and general observations were made by 50 (31%). The responses provide several insights into the nature of translation work at IGOs today. The skills and knowledge types that, according to the survey participants, are required in addition to the 40 included in the ranking can be loosely grouped as shown below. The number of times each one was mentioned is presented in parentheses, and the respondents’ own wording is used as much as possible:

Communication skills to be able to elicit assistance or answers from others in the organization, especially authors of source texts (11)

Ability to work with revisers: openness to feedback and ability to learn from it (10)

Team work skills, including for working on large translation projects and with shared translation memories (8)

Language skills: ability to learn new languages, translate from several source languages, ability to create new terminology for new concepts, to adapt to the style used in the unit (8)

Knowledge of translation theories and practices (6)

Critical thinking skills (ability to “reason through” the translation, a “second channel” in the brain to think beyond just choosing the right word) (5)

Organization and time management skills (5)

General knowledge, awareness of current and world events (5)

Interpersonal skills: patience with authors, requesters and colleagues (4)

Flexibility, adaptability to cope with unpredictable workload, changes in procedures, etc. (4)

Experience in other international organizations, ability to cope with life in another country, awareness of cultural differences (3)

Ability to work independently (3)

Ability to deal with a wide range of specialized subjects (3)

Self-revision skills (1)

Willingness to search for information (1)

As shown in the above list, interpersonal skills such as the ability to work as a member of a team and communicate with “clients” are mentioned more than any other type. Several comments on the need to be able to seek clarification from authors were accompanied by remarks on the poor quality of source texts and the ability to argue points diplomatically and “not to be rattled by criticisms of one’s English from people not really qualified to make them,” as one translator put it.

There were also complaints about the restrictions imposed by tradition and conventions. One respondent commented that “[c]omplying with the in-house rules and conventions is sometimes more important than the ability to reproduce a text elegantly or even accurately,” and another stated that “translators have to ‘forget’ their general knowledge and use the terms agreed on at the inter-institutional level even if they don’t agree with them or have a better suggestion.”

In addition to suggesting other skills and knowledge types, several respondents to the impact questionnaire took the opportunity to emphasize the importance of expert subject knowledge (of economics and legal systems for instance). This was ranked only 29th by respondents across all organizations, possibly revealing the prime importance of this knowledge in some organizations (rated 5 by 70 respondents) but not in others.

A number of respondents said they had nothing to add and commented on the comprehensiveness of the list of skills and knowledge types presented for rating. Some took the opportunity to sum up what they thought translators at IGOs need. One EU translator wrote: “Basically, we need a thorough knowledge of source languages and the ability to efficiently find whatever info/terminology we need and convey the message in the target language clearly while adhering to in-house rules, often [translating] from source texts of poor linguistic quality.” What would appear to be a seasoned reviser at the ILO noted: “The skills required haven’t changed much: thorough knowledge of source and target languages, highly developed analytical skills, and the ability to assimilate new knowledge quickly.” Both, incidentally, mention two not wholly unrelated aspects of IGO translation that are not usually given much attention in translator training programmes or recruitment: the translation of poorly written source texts and the need for superior analytical skills.

3.2. The results of the recruits questionnaire: the relative scarcity of different skills and types of knowledge among new recruits

The mean frequency with which each skill or knowledge type was found lacking among new recruits is presented in Table 2. Ratings were awarded in response to the question:

Please think about the mistakes you usually correct when going over translations done by new recruits. How often do you think those mistakes are due to a lack of the following? 1 = Almost never and 5 = Almost always.

Table 2

Frequency with which selected skills and knowledge types are found lacking among new recruits[a]

(Number of responses and mean rating)

Where TT = target text; TL = target languages; SL = source language; ST = source text. Descriptions of skills and knowledge have been abbreviated for the sake of space. For the full descriptions, see the recruits questionnaire in Annex 2.

New recruits at least sometimes lack 18 of the 40 skills and knowledge types that revisers were asked to rate on the five-point scale (these were all rated above 3). Of these, almost half (8) are related to target-language writing skills; 3 are research skills, 2 refer to analytical skills (working out obscure passages and detecting inconsistencies); 2 to specialized knowledge (of subject areas and of the organization), 1 to capturing detailed and exact meanings (nuances), 1 to in-house style and 1 to productivity. In other words, in addition to linguistic skills traditionally associated with translation and deficient TL writing skills usually associated with revision work, analytical skills (the ability to detect inconsistencies in the source text and to judge the reliability of sources) are among those rated, on average, as more often than not lacking among new recruits. Indeed, the relative inability of new recruits to figure out meaning is generating almost as much revision work as their (expected) ignorance of in-house style. And this shortcoming is not due to their lack of language skills since their SL knowledge is only relatively rarely found to be deficient (ranked 22nd with a mean frequency rating of only 2.78).

3.2.1. The additional skills and knowledge types reported as lacking among new recruits

The optional question on other skills and knowledge types that new recruits often lack and need was answered by 26 people (17% of respondents), and general observations were made by 48 (31%). The answers have been grouped as follows (the number of times each one was mentioned is presented in parenthesis) and respondents’ own wording is used as far as possible:

General knowledge, awareness of current affairs (10)

Organization and time management skills, including ability to attain the right balance between speed and quality (7)

Quality management skills: how and when to adjust criteria, ability to check for internal consistency and read for sense (7)

Knowledge of translation and terminology theories, strategies and practices (6)

Target language skills: thorough grasp of own language, correct grammar; the ability to write idiomatically, avoid “apishly reproducing the structure of the source text,” and achieve the right tone and register (6)

Ability to work with computer-based translation memory, glossary-building, machine-translation and voice-recognition tools and to judge the results obtained (5)

Client orientation, professional conduct (3)

Awareness of the SL structures that pose translation challenges (2)

Sensitivity to the subtext and implications of what the text is saying (2)

Ability to approach and work effectively with authors of source texts (2)

Team work skills (2)

Ability to work with poorly written source texts (1)

Ability to work with revisers: openness to feedback and ability to learn from it (1)

Willingness to take the time needed to search properly for information (2)

Several revisers also took the opportunity in the comments section to stress the shortage of certain components of the skill and knowledge set: subject or technical knowledge (ranked 7th in the frequency ratings), for example, was mentioned again eight times, and knowledge of the organization and its activities (ranked 13th) was referred to again three times. There were in general more remarks about the lack of target-language writing skills than about deficient source-language comprehension skills.

The component most often mentioned as lacking among new recruits (in addition to those presented for rating in the recruits questionnaire) was general knowledge. This is considered vital because, as one reviser put it, “[t]he more understanding you have of the general background, the better are your translations.” There were several comments on how younger translators in particular rarely read newspapers or news magazines to keep themselves informed of current affairs.

There were a number of observations about the inferior quality of the translations produced by new recruits in general: they “tend to translate words and not meanings”; “[s]ince most documents are written by non-native speakers, the translations can be meaningless”; they lack the ability to “step back” and read their own work for “internal consistency.” Also, reaffirming the high ranking of the abilities to produce idiomatic translations and to produce translations that flow smoothly, some respondents reported that there is “too much tendency to stick to the [original language]” and “translations are too literal.” A number of revisers also expressed concern over an apparent lack of translation strategies and techniques (mentioned six times in the comments), which is possibly reflected in the relatively high ranking of the ability to recast sentences.

Several comments were made about time and workload management and having to work to increasingly shorter deadlines. Some lamented new recruits’ inability to keep up; others lamented the lack of room afforded under the more “market-oriented approach” for “continuous learning by (new) translators, which is a vital prerequisite to staying abreast with new knowledge.”

There were also comments about working with poorly written originals, which require the “ability to understand, navigate through and decode the various types of ‘pidgin’ English […which] is becoming more and more usual within international organizations.” These came from revisers working at organizations in which documents are only rarely sent for editing prior to translation.

The number of comments on the need for translators with advanced computer skills (5) seems to point to two views of training needs among revisers. There are those who seem to think translators should have mastered the relevant technology before recruitment, and others who think there is a need to get “back to basics,” instead of worrying about how to use new technologies, which they maintain can usually be learned quickly on the job.

4. Using the findings of the two questionnaires to identify recruitment and training priorities

The findings of both the impact questionnaire and the recruits questionnaires have implications for recruitment at IGOs. Adjusting selection procedures to identify candidates with the profile that emerges from the findings of the impact questionnaire should help organizations find translators who will have the most positive impact on the effectiveness of their translations. Adjusting selection procedures according to the findings of the recruits questionnaire, meanwhile, should help reduce the revision workload and hence enhance the quality and efficiency of the translation service. The findings of the two questionnaires therefore need to be correlated. The relative impact of a component of the skill and knowledge set has a bearing on how much attention should be paid to its relative scarcity among new recruits. Or to put it the other way round, the relative scarcity of a skill or knowledge type determines how much attention should be paid to its impact. Subject knowledge, for example, is often found to be lacking (ranked as the 7th most frequent cause of revision work) but is rated as relatively less important than 28 other components of the skill and knowledge set in the impact questionnaire. Conversely, knowledge of the source language, which is ranked as the 4th most important component, seems to be relatively easy to find among new translators or is being well tested for, inasmuch as it only rarely or sometimes accounts for the errors that revisers have to correct (mean frequency rating of 2.74). In order to improve the quality of translation work and reduce the revision load, organizations need to recruit more translators who, in addition to the more important skills and knowledge types already being successfully assessed in recruitment, have the important ones that are currently not being found in sufficient quantities. These skills and knowledge types can be pinpointed by mapping the impact and frequency ratings of the components of the skill and knowledge set on a scatter chart. Priorities can then be determined by applying the logic of qualitative risk analysis, as described by Tusler (1996) for example, in order to classify the components into four categories: tigers, foxes, anteaters and hedgehogs (an adaptation of Tusler’s equally whimsical labels), each with their own implications for training and recruitment.

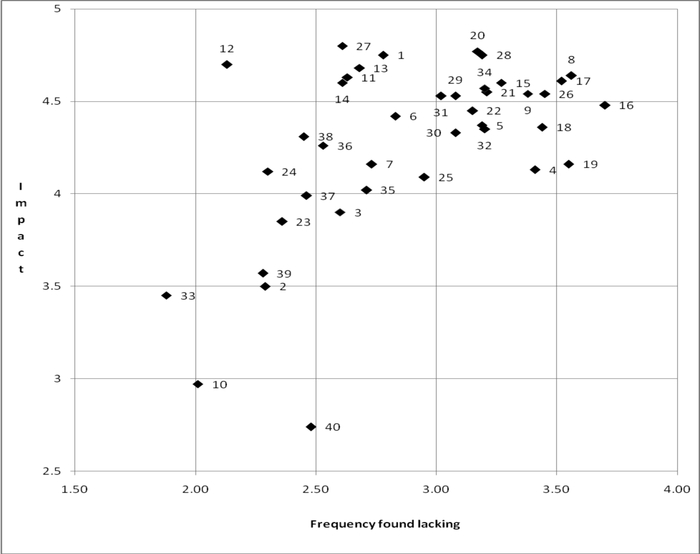

Figure 1 shows the correlation of the impact and frequency ratings for the skills and knowledge types on the base list presented for consideration in the corresponding questionnaires. The other skills and knowledge types mentioned by respondents as being important in IGO translation or as sometimes lacking among new recruits (mainly general knowledge and interpersonal skills) have not been included because the focus of this research is on obtaining input for text-based translation skills testing. These additional types of skills and knowledge are obviously highly relevant, however, and should be factored into candidate selection. To identify recruitment priorities, impact ratings of 4.5 or more and frequency ratings of 3 or more are considered high. These cut-off points are not completely arbitrary: they isolate the high-impact skills and knowledge types that at least sometimes account for the errors that revisers have to correct. The resulting groupings and the implications of classification in each grouping are presented below. The items within each category are listed by cluster from top right to bottom left, i.e., from the highest priority to the lowest from the recruitment perspective. The numbers in brackets correspond to the numbering used in Figure 1.

Figure 1

Inter-governmental organizations: skills and knowledge types by frequency found lacking among new recruits and impact on the effectiveness of translations

Key to figure

Knowledge of SL

Knowledge of SL varieties

Knowledge of SL culture(s)

Subject knowledge

Knowledge of the organization

Understand complex topics

Master new subjects quickly

Work out the meaning of obscure passages

Detect inconsistencies, contradictions, etc.

Detect mathematical errors in the ST

An extensive TL vocabulary

Knowledge of TL spelling rules

Knowledge of TL grammar

Knowledge of TL punctuation rules

Produce idiomatic translations

Produce translations that flow smoothly

Capture nuances of ST

Recast sentences in the TL

Write elegantly regardless of the ST

Convey the ST message clearly

Convey the intended effect of the ST

Achieve the right tone and register

Knowledge of TL varieties

Knowledge of TL culture(s)

Tailor language to the readers’ needs

Adhere to in-house style conventions

Ensure the completeness of the TT

Ensure the coherence of the TT

Track down sources to check facts

Track down sources to understand the topic

Mine reference material for phrasing

Judge the reliability of information sources

Type accurately and fast

Maintain quality even under time pressure

Explain translation decisions and problems

Follow complicated instructions

Work with translation memory software

Work with electronic terminology tools

Handle more than basic Word functions

Work with Excel and/or PowerPoint

4.1. The hedgehogs: low-impact commonly found skills and types of knowledge

Understand complex topics (6), Work with electronic terminology tools (38), Follow complicated instructions (36), Master new subjects quickly (7), Tailor language to the readers’ needs (25)

Explain translation decisions and problems (35), Knowledge of TL culture(s) (24)

Work with translation memory software (37)

Knowledge of SL culture(s) (3)

Knowledge of TL varieties (23)

Handle more than basic Word functions (39), Knowledge of SL varieties (2)

Type accurately and fast (33)

Detect mathematical errors in the ST (10)

Work with Excel and/or PowerPoint (40)

The hedgehogs are the lowest recruitment priorities. New recruits usually have these skills and types of knowledge, and their impact on the effectiveness of translations at IGOs is relatively small. They are scattered quite widely within the group. At one end of the spectrum, the ability to understand complex topics is very close to being classified as a fox. At the other end, typing, mathematical and word-processing skills are rated so low that they probably do not need to be factored into assessment at all. The presence of cultural knowledge in this group is somewhat surprising considering the amount of comments made on the need for general knowledge.

4.2. The foxes: high-impact commonly found skills and types of knowledge

Knowledge of SL (1)

Ensure the completeness of the TT (27)

Knowledge of TL grammar (13), An extensive TL vocabulary (11), Knowledge of TL punctuation rules (14)

Knowledge of TL spelling rules (12)

The foxes are needed because of the impact they have on the quality and productivity of the translation service. They include the basic prerequisite of source language knowledge and the ability to ensure a fundamental quality of a good translation: that it transmits all the information contained in the source text. These skills and types of knowledge are not often found lacking among new recruits and are therefore not generating much revision work, which means they are either relatively easy to acquire or are being found in relative abundance through current selection procedures. They are certainly all routinely tested in recruitment examinations.

4.3. The anteaters: low-impact oft-lacking skills and types of knowledge

Produce translations that flow smoothly (16), Achieve the right tone and register (22)

Recast sentences in the TL (18), Knowledge of the organization (5), Judge the reliability of information sources (32), Write elegantly regardless of the ST (19), Track down sources to understand the topic (30), Subject knowledge (4)

The anteaters also matter: although they do not have such a great impact on the effectiveness of translations at IGOs, their absence generates a large proportion of revision work. The first two in this category, the abilities to produce translations that flow smoothly and to achieve the right tone and register, came close to being classified as tigers.

4.4. The tigers: high-impact oft-lacking skills and types of knowledge

Work out the meaning of obscure passages (8), Capture nuances of ST (17)

Convey the ST message clearly (20), Ensure the coherence of the TT (28), Adhere to in-house style conventions (26), Detect inconsistencies, contradictions, etc. (9)

Produce idiomatic translations (15), Maintain quality even under time pressure (34), Convey the intended effect of the ST (21)

Track down sources to check facts (29)

Mine reference material for phrasing (31)

Tigers should be top recruitment priorities. Not only is their absence generating a lot of revision work, but also they have a strong impact on the effectiveness of the translations that IGO translation services produce. These are the skills that IGOs need to find more of, in addition to the skills and knowledge in the fox and anteater categories that they already successfully assess. Alternatively they need to develop these skills in-house soon after recruitment.

4.5. The ideal candidate

The profile of the ideal candidate for IGO translation work that emerges from this study therefore is of a translator who, in addition to strong target-language writing abilities, sound source-language knowledge and good research skills, has superior analytical skills and a keen eye for detail to work out obscure meanings, to rectify or flag inconsistencies and to capture the nuances of the original. Furthermore, this translator can produce clearly written idiomatic target texts that are internally consistent and convey the intended effect of the source text. And they can do so fast. Ideally they also have thorough knowledge of in-house style conventions, good research skills and experience of working with background documents. Translators with that specific profile are the ones that IGOs, based on the views of their translators and revisers, need to find in greater quantities.

5. Discussion

These findings correspond to IGOs as a whole, and the hierarchy presented above suggests the profile of the candidates that IGO should in general be looking for if they wish to improve the output of their translation services in terms of both quality and productivity. It could therefore be of interest to potential applicants for IGO translation work and their trainers.

To be of value to IGO recruitment officers, however, these findings need to be broken down further, by individual organization and possibly even by language service since the expectations of new staff translators and the opportunities for post-recruitment skills development might vary considerably from one organization to the next. The profile of the ideal candidate at NATO, for example, might not be the same as at the EU, and the skill set required in the Arabic translation service at the United Nations Office in Geneva may not be the same as the set required in the Russian service. The composition and weighting of the set of skills and knowledge required by in-house staff might also differ from that of external freelance translators. A more focused analysis could also enhance decisions about where the cut-off should be when classifying skills and knowledge types as high or low impact and high or low frequency when correlating the results of the two questionnaires.

Once broken down by organization or language service, the candidate profile can be adjusted according to expectations of new recruits. High-priority skills and knowledge that translators are not expected to have when they first join the organization can become on-the-job training priorities. This might apply to mastery of in-house style guidelines, the ability to work with reference documents and knowledge of the organization, for example. The weighting of the remaining components of the skill and knowledge set can then be used to identify adjustments that need to be made to current testing practice. The high-impact, oft-lacking components (the tigers) that are not being weighted heavily or assessed at all in recruitment examinations should be incorporated and weighted heavily in grading schemes, certainly more heavily than the skills and knowledge types in the other categories. By the same logic, the components in the fox and anteater categories need to be weighted between the hedgehogs and the tigers. Such adjustments should help IGOs find more candidates who match the particular profile they seek.

6. Conclusions

The study confirms that translators need more than language skills: in addition to general and sometimes specialized knowledge, they need analytical, research, technological, interpersonal and organization skills. It also shows that some skills and knowledge types are more important than others and ranks them by their importance in the context of IGO translation. The study also identifies the most common shortcomings of new recruits at IGOs. Whether these are the result of current IGO selection procedures or a general characteristic of novice translators is a matter for further research. The weighted list of skills and knowledge types obtained by correlating the impact and frequency ratings indicates the profile that IGOs need to look for and, by extension, the skills and knowledge that translators and translator trainers interested in this market niche may wish to develop. The high ranking of analytical skills in both questionnaires poses an interesting challenge to translator training. When considered in light of current testing practice and the expectations of new recruits, the skills and knowledge profiles obtained through the methodology presented here can be used to identify recruitment and/or on-the-job training priorities not only in specialized branches of translation, but possibly also in other fields in which new recruits are closely monitored, such as interpreting.

Parties annexes

Appendices

Appendix 1. The Impact Questionnaire. Translation: The Skills and Knowledge Required

Respondent Profile

1. Which Organization are you currently working for?

2. What is your current position in the organization?

☐ |

Head of Department/Unit/Service |

☐ |

Reviser |

☐ |

Translator |

3. Please base your answers in the following sections on the work of either in-house translators or external translators (but not both). Which will you base your answers on?

☐ |

The work of in-house translators |

☐ |

The work of external translators |

4. Which languages do you translate from in your current post?

☐ |

Arabic |

☐ |

Chinese |

☐ |

English |

☐ |

French |

☐ |

German |

☐ |

Portuguese |

☐ |

Russian |

☐ |

Spanish |

☐ |

Others If you answered “Other(s),” please specify |

5. Which languages do you translate into in your current post?

☐ |

Arabic |

☐ |

Chinese |

☐ |

English |

☐ |

French |

☐ |

German |

☐ |

Portuguese |

☐ |

Russian |

☐ |

Spanish |

☐ |

Others If you answered “Other(s),” please specify |

The Relative Importance of Specific Skills and Knowledge

For the purposes of this survey, effective translations are those that achieve the communicative aims of the organization and protect its image.

1. How large is the impact of the following skills and knowledge types on the effectiveness of translations at your organization? 1 = extremely small; 5 = extremely large; N/A = not applicable because the skill or knowledge is not required

Knowledge of the source language (vocabulary, expressions, rhetorical devices)

Knowledge of the different varieties of the source language

Knowledge of the source-language culture(s) (history, geography, economic and political situation, customs, value-laden concepts, sensitive issues, etc.)

Knowledge of the subject (technical knowledge, e.g., of economics, international law, science, technology)

Knowledge of the organization and how it works

The ability to understand complex topics

The ability to master new subjects quickly (i.e., gain more than a layperson’s knowledge)

The ability to work out the meaning of obscure passages in the source text

The ability to detect inconsistencies, contradictions, nonsense, unintended ambiguities, misleading headings, etc. in the source text

The ability to detect mathematical errors in the source text

An extensive vocabulary in the target language

Knowledge of spelling rules in the target language

Knowledge of the finer points of grammar of the target language

Knowledge of punctuation rules in the target language

The ability to produce idiomatic (natural-sounding) language in the target text

The ability to produce translations that flow smoothly even when the source text does not

The ability to select and combine words in the target language to capture the exact and detailed meanings (nuances) of the source text

The ability to recast sentences in the target language (to say the same thing in different ways)

The ability to produce an elegantly written target text regardless of how elegantly written the source text is

The ability to convey the source-text message clearly

The ability to convey the intended effect of the source text

The ability to achieve the appropriate tone and register in the target text

Knowledge of target-language varieties

Knowledge of target-language cultures (knowledge of history, geography, economic and political situation, customs, traditions, belief systems, value-laden concepts, sensitive issues, etc.)

The ability to tailor the language of the target text to the readers’ needs

The ability to adhere to in-house style conventions

The ability to ensure the completeness of the target text (i.e., no unwarranted omissions)

The ability to ensure the coherence of the target text (e.g., consistent terminology use, no contradictions, logical connections of ideas)

The ability to track down sources of information to check facts

The ability to track down sources to obtain a better grasp of the thematic aspects of a text (understand the topic)

The ability to mine reference material for accepted phrasing and terminology (those used by the organization or in a specialized field)

The ability to judge the reliability of information sources

The ability to type accurately and fast

The ability to maintain quality even when translating under time pressure

The ability to justify translation decisions and explain translation problems posed by the source text (e.g., to authors, users or revisers)

The ability to follow complicated instructions about what needs to be done with a text (additions that need translating, parts that need relocating, patching together, revising against new versions, etc.)

The ability to make effective use of translation memory software

The ability to make effective use of electronic terminology tools

The ability to work with more than basic Word functions (formatting, macros, track changes, tables, autocorrect, etc.)

The ability to work with Excel documents and/or PowerPoint presentations

2. Are new recruits expected to have all the skills and types of knowledge you have rated from 1-5 before they join the organization? If not, please specify which knowledge or skills are expected to be acquired after recruitment

3. Please list any other skills or types of knowledge that have an impact on the effectiveness of translations at your organization and rate their impact using the same scale as above (1 = extremely small impact; 5 = extremely large impact). E.g., Knowledge of translation theory: 3

Comments

1. Please use the space below to make any observations about the skills and knowledge that translators need at your organization or to comment on the questionnaire. Your input will be much appreciated

2. Thank you so much for taking the time to answer the questionnaire. Which e-mail address would you like the summary of the survey findings to be sent to?

Appendix 2. The Recruits Questionnaire. The Skills and Knowledge of New Recruits

Respondent Profile

1. Which Organization are you currently working for?

2. What is your current position in the organization? If you revise (or have regularly revised) the work of other translators in the organization, please put “reviser,” even if this is not officially your position

☐ |

Head of Department/Unit/Service |

☐ |

Reviser |

3. Please base your answers in the following sections on the work of either in-house translators or external translators (but not both). Which will you base your answers on?

☐ |

The work of in-house translators |

☐ |

The work of external translators |

4. Which languages do you translate from in your current post?

☐ |

Arabic |

☐ |

Chinese |

☐ |

English |

☐ |

French |

☐ |

German |

☐ |

Portuguese |

☐ |

Russian |

☐ |

Spanish |

☐ |

Others If you answered “Other(s),” please specify |

5. Which languages do you translate into in your current post?

☐ |

Arabic |

☐ |

Chinese |

☐ |

English |

☐ |

French |

☐ |

German |

☐ |

Portuguese |

☐ |

Russian |

☐ |

Spanish |

☐ |

Others If you answered “Other(s),” please specify |

The Skills and Knowledge that the New Recruits May Lack

For the purposes of this questionnaire, new recruits are translators who have been working with the organization for less than 12 months.

1. Please think about the mistakes you usually correct when going over translations by new recruits. How often do you think those mistakes are due to a lack of the following things? 1 = Almost never; 5 = Almost always; N/A = Not applicable because the skill or knowledge is not required of new recruits

Knowledge of the source language (vocabulary, expressions, rhetorical devices)

Knowledge of the different varieties of the source language

Knowledge of the source-language culture(s) (history, geography, economic and political situation, customs, value-laden concepts, sensitive issues, etc.)

Knowledge of the subject (technical knowledge, e.g., of economics, international law, science, technology)

Knowledge of the organization and how it works

The ability to understand complex topics

The ability to master new subjects quickly (i.e., gain more than a layperson’s knowledge)

The ability to work out the meaning of obscure passages in the source text

The ability to detect inconsistencies, contradictions, nonsense, unintended ambiguities, misleading headings, etc. in the source text

The ability to detect mathematical errors in the source text

An extensive vocabulary in the target language

Knowledge of spelling rules in the target language

Knowledge of the finer points of grammar of the target language

Knowledge of punctuation rules in the target language

The ability to produce idiomatic (natural-sounding) language in the target text

The ability to produce translations that flow smoothly even when the source text does not

The ability to select and combine words in the target language to capture the exact and detailed meanings (nuances) of the source text

The ability to recast sentences in the target language (to say the same thing in different ways)

The ability to produce an elegantly written target text regardless of how elegantly written the source text is

The ability to convey the source-text message clearly

The ability to convey the intended effect of the source text

The ability to achieve the appropriate tone and register in the target text

Knowledge of target-language varieties

Knowledge of target-language cultures (knowledge of history, geography, economic and political situation, customs, traditions, belief systems, value-laden concepts, sensitive issues, etc.)

The ability to tailor the language of the target text to the readers’ needs

The ability to adhere to in-house style conventions

The ability to ensure the completeness of the target text (i.e., no unwarranted omissions)

The ability to ensure the coherence of the target text (e.g., consistent terminology use, no contradictions, logical connections of ideas)

The ability to track down sources of information to check facts

The ability to track down sources to obtain a better grasp of the thematic aspects of a text (understand the topic)

The ability to mine reference material for accepted phrasing and terminology (those used by the organization or in a specialized field)

The ability to judge the reliability of information sources

The ability to type accurately and fast

The ability to maintain quality even when translating under time pressure

The ability to justify translation decisions and explain translation problems posed by the source text (e.g., to authors, users or revisers)

The ability to follow complicated instructions about what needs to be done with a text (additions that need translating, parts that need relocating, patching together, revising against new versions, etc.)

The ability to make effective use of translation memory software

The ability to make effective use of electronic terminology tools

The ability to work with more than basic Word functions (formatting, macros, track changes, tables, autocorrect, etc.)

The ability to work with Excel documents and/or PowerPoint presentations

2. Are there other skills or types of knowledge that new recruits may lack and should have at your organization? Please list them and award them a rating using the same scale as above (1 = Almost never to 5 = Almost always). E.g., Knowledge of translation theory: 3

Document Processing

1. In order to contextualize the findings, please answer the following questions about document processing at your organization using the scale provided (never, rarely, sometimes, often, always)

How often are source texts edited (for style and/or content) before they are translated?

How often are source texts pretranslated before being sent to the translator (previously translated text is highlighted or provided)?

How often are source texts referenced before being sent to the translator (names are checked, official translations of terms given, background documents and sources identified, etc.)?

How often in practice are translations fully revised against the source text?

How often are translations (whether revised or not) sent to the author or requester for approval?

2. In your translation unit, are translators responsible for the following aspects of the translated text?

Formatting |

Yes/No |

Spelling |

Yes/No |

Adhering to in-house style conventions |

Yes/No |

Observations |

Comments

1. Please use the space below to make any observations about the skills and knowledge that new translators need and may lack at your organization or to comment on the questionnaire. Your input will be much appreciated

2. Thank you so much for taking the time to answer the questionnaire. Which e-mail address would you like the summary of the survey findings to be sent to?

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank the Working Group on Training of IAMLADP for distributing the questionnaires through its focal points, the translators, revisers and heads of service of the various organizations that took part in the survey, and in particular the translators and revisers at the United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean for participating in the pilots. The views expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the United Nations.

Notes

-

[1]

The exact number of organizations is difficult to determine because the specificity of answers varied. The distribution of replies to the impact questionnaire was as follows: European Union bodies: ESSC and Committee of the Regions (65); Council of the EU (13); European Patents Office (2); unspecified European Union (2); United Nations system: UNOG (27), unspecified UN (12), ECLAC (8), UNHQ (4), FAO (3), UNOV (2), UNON (1), ICAO (1), ECA (1), ESCWA (1), ITU (1), ICC (1), ILO (1), Special tribunal for the Lebanon (1), and World Bank (1); ICRC (1); Non-IAMLADP members invited to participate by the researcher: IDB (1), IIC (4), SELA (1); freelancers working for more than one organization (8); and an unspecified Commission (1).

-

[2]

The exact number of organizations is difficult to determine because the specificity of answers varied. The distribution of replies to the recruits questionnaire was as follows: UNOG (20), UNOV (1), UNON (2), unspecified UN (20), ICAO (2), ECLAC (6), ECA (1), ESCWA (1), ITU (1), ILO (3), ICC (2), WFP (3), Special tribunal for the Lebanon (1), Special tribunal for the Ruanda (1), ITLOS (1), FAO (3), World Bank (3), IMF (1); Non-IAMLADP members invited to participate by the researcher (2 organizations, 4 respondents): IDB (2), IIC (2); 65 EU (EESC and Committee of the Regions (45), EU Patent Office (3), Council of the EU (16), EBRD (1)); 1 freelance reviser working for more than one organization.

Bibliography

- Angelelli, Claudia (2009): Using a rubric to assess translation ability. Defining the construct. In: Claudia Angelelli and Holly Jacobson, eds. Testing and Assessment in Translation and Interpreting Studies. A Call for Dialogue between Research and Practice. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins, 13-47.

- Arango-Keeth, Fanny and Koby, Geoffrey (2003): Assessing assessment. Translation training evaluation and the needs of industry quality assessment. In: Brian Baer and Geoffrey Koby, eds. Beyond the Ivory Tower: Rethinking Translation Pedagogy. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins, 117-134.

- Baer, Brian J. and Koby, Geoffrey, eds. (2003): Beyond the Ivory Tower. Rethinking Translation Pedagogy. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

- Bell, Roger T. (1991): Translation and Translating: Theory and Practice. London: Longman.

- Campbell, Stuart (1991): Towards a Model of Translation Competence. Meta. 36(2/3):329-343.

- Cao, Deborah (1996): Towards a Model of Translation Proficiency. Target. 8(2):325-340.

- Chesterman, Andrew and Wagner, Emma (2002): Can Theory Help Translators? A Dialogue between the Ivory Tower and the Wordface. Manchester: St Jerome.

- EMT (2009): Competences for professional translators, experts in multilingual and multimedia communication. Visited on 24 October 2011, http://ec.europa.eu/dgs/translation/programmes/emt/.

- EUROPEAN COMMISSION (2009): Translation and interpreting – Languages in Action. Visited 24 October 2011, http://ec.europa.eu/dgs/translation/publications/brochures/index_en.htm.

- Hatim, Basil and Mason, Ian (1997): The Translator as Communicator. London: Routledge.

- Hindle, William (1965/1984). A Guide to Writing for the United Nations. New York. Department of Conference Services, United Nations. Internal document (ST/DCS/3). Visited on 24 October 2011, http://www.un.org/depts/OHRM/sds/lcp/English/docs/a_guide_to_writing_for_the_united_nations.pdf.

- Kelly, Dorothy (2005): A Handbook for Translator Trainers: A Guide to Reflective Practice. Translation Practices Explained. Vol. 10. Manchester: St. Jerome.

- Koskinen, Kaisa (2000): Institutional Illusions. Translating in the EU Commission: A Finnish Perspective. The Translator. 6(1):49-65.

- Koskinen, Kaisa (2008): Translating Institutions. An Ethnographic Study of EU Translation. Manchester: St Jerome.

- Mossop, Brian (1988): Translating Institutions: A Missing Factor in Translation Theory. TTR. 1(2):65-71.

- Mossop, Brian (2001): Revising and Editing for Translators. Manchester: St Jerome.

- Nord, Christiane (2005): Text Analysis in Translation: Theory, Method, and Didactic Application of a Model for Translation-Oriented Text Analysis. Amsterdam/New York: Rodopi.

- Orozco, Mariana and Hurtado Albir, Amparo (2002): Measuring Translation Competence Acquisition. Meta. 47(3):375-402.

- PACTE (2008): First Results of Translation Competence Experiment: “Knowledge of Translation” and “Efficacy of the Translation Process.” In: John Kearns, ed. Translator and Interpreting Training: Issues Methods and Debates. London: Continuum, 104-126.

- Pym, Anthony (2003): Redefining Translation Competence in an Electronic Age. In Defence of a Minimalist Approach. Meta. 48(4):481-497.

- Sekel, Stephen (2008): United Nations Translators and Interpreters – Silent Partners in the Diplomatic Process. Keynote Address delivered by Mr. Yohannes Mengesha, Assistant Secretary-General of the United Nations, at the 18th FIT World Congress, 4-7 August 2008 Shanghai, China. Posted on the intranet (staff-only) website of the United Nations Secretariat in September 2008.

- Tusler, Robert (1996). An Overview of Project Risk Management. Visited on 24 October 2011, http://www.netcomuk.co.uk/~rtusler/project/elements.html.

- Waddington, Christopher (2001): Different Methods of Evaluating Student Translation: The Question of Validity. Meta. 46(2):311-325.

- Wagner, Emma, Bech, Svend and Martínez, Jesús (2002): Translating for the European Union Institutions. Manchester: St Jerome.

- Way, Catherine (2008): Systematic Assessment of Translator Competence: In Search of Achilles’ Heel. In: John Kearns, ed. Translator and Interpreting Training: Issues Methods and Debates. London: Continuum, 88-103.

- Williams, Malcolm (1989): The Assessment of Professional Translation Quality: Creating Credibility out of Chaos. TTR. 2(2):13-33.

Liste des figures

Figure 1

Inter-governmental organizations: skills and knowledge types by frequency found lacking among new recruits and impact on the effectiveness of translations

Key to figure

Knowledge of SL

Knowledge of SL varieties

Knowledge of SL culture(s)

Subject knowledge

Knowledge of the organization

Understand complex topics

Master new subjects quickly

Work out the meaning of obscure passages

Detect inconsistencies, contradictions, etc.

Detect mathematical errors in the ST

An extensive TL vocabulary

Knowledge of TL spelling rules

Knowledge of TL grammar

Knowledge of TL punctuation rules

Produce idiomatic translations

Produce translations that flow smoothly

Capture nuances of ST

Recast sentences in the TL

Write elegantly regardless of the ST

Convey the ST message clearly

Convey the intended effect of the ST

Achieve the right tone and register

Knowledge of TL varieties

Knowledge of TL culture(s)

Tailor language to the readers’ needs

Adhere to in-house style conventions

Ensure the completeness of the TT

Ensure the coherence of the TT

Track down sources to check facts

Track down sources to understand the topic

Mine reference material for phrasing

Judge the reliability of information sources

Type accurately and fast

Maintain quality even under time pressure

Explain translation decisions and problems

Follow complicated instructions

Work with translation memory software

Work with electronic terminology tools

Handle more than basic Word functions

Work with Excel and/or PowerPoint

Liste des tableaux

Table 1

Impact ratings of selected skills and knowledge types[a]

Table 2

Frequency with which selected skills and knowledge types are found lacking among new recruits[a]

10.7202/002190ar

10.7202/002190ar