Résumés

Abstract

Recent historical translation research done on Basque state-owned television shows that while the Basque-speaking channel has used dubbed translation of children’s programmes to promote and standardize the use of Basque, the Spanish-speaking channel has competed in the wider market of Spanish broadcasting channels with fiction for adults. The choice of products to be broadcast for diverse target audiences clearly reflects a diglossic situation in terms of language distribution but it also serves to illustrate government language planning policies. Since Basque television is controlled by political instances (power), manipulation and ideology clearly have an influence both selecting the programmes and controlling the type of (Basque) language used when translating and dubbing imported products.

Keywords:

- audiovisual translation,

- Basque television,

- dubbing,

- minority language

Résumé

Une étude récente, menée sur les chaînes de télévision basques sous l’angle de l’histoire de la traduction, montre que la chaîne de langue basque a eu recours au doublage pour les programmes destinés aux enfants afin de promouvoir et normaliser la langue basque, tandis que la chaîne hispanophone a diffusé des programmes de fiction pour adultes en concurrence avec le vaste marché des chaînes espagnoles. Le choix des produits à diffuser selon l’audience visée reflète, d’une part, une situation de diglossie quant à la répartition des langues, et d’autre part, la politique de planification linguistique du gouvernement. Étant donné que la télévision basque est sous contrôle politique (pouvoir), la manipulation et l’idéologie entrent directement en jeu dans le choix de la programmation et de la langue utilisée (le basque) pour la traduction et le doublage des produits importés.

Mots-clés :

- traduction audiovisuelle,

- télévision basque,

- doublage,

- langue minoritaire

Corps de l’article

In recent years Translation Studies has initiated a deliberate move away from a purely linguistic approach toward frameworks that transcend this dimension and place their object of study firmly within a socio-cultural context.

Díaz Cintas 2003: 357

1. Introduction

The aim of this paper is to show the socio-cultural context of audiovisual translation (AVT) in the Basque Country. It is the result of work done by researchers working under TRALIMA (translation, literature and audiovisual media), a Basque research group whose members share a historical point of view of translation and translations.[1]

There are not many diachronic studies in the field of screen translation. In the context of Spanish culture, Díaz Cintas (2001: 102) calls for the exploration of new avenues of research that would encompass the linguistic as well as the cultural dimension and, in his review of Ballester’s study on censored films, he mentions research done along those lines by Spanish scholars “such as Camino Gutiérrez-Lanza and Luis Serrano within the Framework of TRACE” (Díaz Cintas 2003: 360). And it is precisely from the TRACE project on censored translations that research on Basque television was initially planned and is now being carried out.[2]

When dealing with (regional) television, historical studies are also scarce. The issue of the role of minority languages in the audiovisual media in Spain was first addressed in a systematic way by Izard (1999). Her truly pioneering work on Catalan television helped fill a gap and opened the way to further investigation centred on the language of small minorities that, as Danan (1991: 613) states, “are becoming more vocal and claiming their rights to a regional culture” as European unity increases.

Historical studies on AVT in the Basque Country seek to systematically map the question of translations broadcast on both Basque state television channels for a geographically well-identified audience. The compilation of catalogues of translated audiovisual programmes is the major thrust for these descriptive studies which have a solid empirical base. Peritextual and contextual data is collected and analysed to establish criteria for the selection of case studies that are representative of general phenomena and not mere curiosities. Also considered is the fact that the diachronic description of any object of study must look at both the preceding period and the subsequent evolution (Uribarri 2010). In this respect we implement a methodological protocol (Merino 2010) that has proved effective when investigating censored translations in the historical period that gave way to the restructuring of the Spanish state in autonomous regions. Our argumentation is based on the empirical work and the conclusions reached by Barambones (2006; 2010) and Cabanillas (2005).

It can be said that in the Basque country AVT into the Basque language is done only and almost exclusively for one client: the Basque state television’s first channel, ETB1. The second channel, ETB2, which broadcasts in Spanish, does not commission translations. The source of foreign programmes already translated and dubbed in Spanish is usually FORTA,[3] an organisation founded to serve as a coordinating body for the purchasing and distribution of audiovisual material to be shared and broadcast by the TV stations of the different Spanish autonomous regions (Cabanillas 2005: 25). Most of these channels broadcast in Spanish, except for the Catalan TV3 and Channel 33 (Izard 2001: 401) and the Galician TV, and compete in their own regions with nationwide Spanish public channels (TVE1 and TVE2) and the main private stations.

In the early years following its launch on 31 December 1982, ETB1 needed foreign programmes to be able to cater to a market in Basque which was being created from scratch. When Basque television started broadcasting, Spain had just gone through a political period of transition from which a new state of autonomous regions emerged. The issue of minority languages such as Basque was clearly present in the creation of the new television channels confronted with a need to promote and standardise those languages never before used in the audiovisual media, since “[m]inority groups now realize that the media could be a useful tool to promote and reinforce their language and cultural identity” (Gambier 2003: 171). The use of translation to import new programmes was soon seen as imperative and children were the preferred target of language policies aimed at revitalising the Basque language.

When the second Basque television channel, ETB2, began broadcasting in Spanish in 1986 the choice of programmes offered complemented that of the only channel that had been broadcasting in Basque until then, ETB1, and tended to compete with large scale Spanish national channels. While animation and cartoons were the prototype of translated programmes on ETB1, films and series were heavily represented in the second channel. Unlike foreign programmes dubbed in Basque, those dubbed in Spanish and broadcast by Basque Television were transmitted rather than translated and they did not generate a market for Spanish dubbing within the Basque Country. One of the most representative film genres chosen for broadcast on ETB2 on a daily basis from 1999 to the present, namely Westerns, were dubbed years and even decades earlier. In this respect there is a clear link between ongoing studies into ETB2 and research on Westerns done from censorship archives (Camus 2009).

The use of dubbing, as opposed to subtitling, or the tight control exerted over language in general is not at all new in Europe or in Spain for that matter. As early as 1934, Baeza, a well-known cinema critic wrote an article in defence of national languages and cultures against the hegemony of American films, the way of life they portrayed and the ‘colonisation’ of English. The defence of cultural identity, the very idea of a nation and, last but not least, economic matters were as current in the 1930s as they are nowadays. Issues of power, ideology, manipulation and language planning have always been in the background. As Toury (1999: 17) points out: “If it wishes to have any chance of success, planning is always in need of a power base. In fact, very often it is performed for the very sake of attaining power and building a power base.” We will see that censorship is a complex reality that takes different shapes from the outright state control of audiovisual production during the Franco regime to more diffuse situations nowadays. The empirical research done in AVT should contribute to develop and nuance this concept further.

2. The Basque language or Euskera

The Basque language, or Euskera, is a non-Indo-European language which has not so far been linked to any other language with any degree of certainty. This does not mean that Euskera is an isolated language that has had no contact with the civilisations which have passed through the region where it is spoken. For instance, the presence of Latin-based words in the lexicon attests to the mark left by Latin on the Basque language.

In the present day, the area where Basque is spoken falls within three different political administrative areas: the autonomous communities of Euskadi and Navarre in Spain and the regions of Labourd, Lower Navarre and Soule in the French Département of the Atlantic Pyrenees. However, Basque is an official language, jointly with Castilian Spanish, only in Euskadi and certain parts of Navarre. As a result, Basque is in a minority position in areas where either Spanish or French is the dominant language. Furthermore, it should be pointed out that according to data from the most recent sociolinguistic survey carried out by the Basque Government (2008), there are no Basque monolinguals above the age of 16.

In spite of the small size of the Basque Country, the history and isolation that have shaped the rural areas have contributed to dividing Basque into six different dialects and various subdialects, which are substantially different in terms of their phonetics, lexicon and morphology. The lack of a common standard language has had a negative impact on cultural production in Basque, which was of little significance until well into the second half of the twentieth century.

Two factors have been decisive in the recent flowering of cultural production in Basque. Firstly, in 1968, the Royal Academy of the Basque Language, the Euskaltzaindia, undertook the task of establishing a unified literary standard for the language; secondly, the instatement of democracy in Spain brought with it political decentralisation giving rise to the establishment of a regional autonomous government in the Spanish Basque Country. These new administrative structures made it possible to pass laws aimed at promoting and developing the Basque language. Thus, Article 3.2 of the 1978 Spanish Constitution and Article 6 of the 1979 Statute of Autonomy of the Basque Country recognise Basque as an official language in Euskadi alongside Spanish as the other official language. The granting of official status then required legislation to accommodate Basque as a joint official language. In 1982, the Basic Law for the Use of Basque (Ley 10/1982 básica de normalización del uso del euskera) set out the basic framework for the use of Basque in public administration, education and the media, and established the means by which the language would be integrated into public life.

The standardisation process was not without controversy in that certain groups viewed the promotion of a standard language as discrimination against dialects. Hence, the promotion of a standard language based on one of the central dialects created a sense of alienation in some speakers of the peripheral dialects. In addition, there was the problem inherent to any standardisation process, namely, which forms and usages were to be accepted as correct and which would be excluded.

The debate gave way to a general acceptance of the new standard. Gradually, the use of the standard language in the spheres of education, media and administration served to disseminate the rules stipulated by the Euskaltzaindia. Over time, the domains of use for both the standard and non-standard varieties came to be established through an ongoing dynamic process.

According to the above mentioned survey carried out by Basque Government (2008), the population over the age of 16 in the administrative regions of Euskadi, Navarre and the French Basque Country stands at 2,589,600. Of these, 665,000 (25.71%) are bilingual. The results of the survey also show that the rise in the number of bilinguals has occurred mainly in Euskadi and make clear how important it is that the authorities recognise Basque as an official language. By the same token, in the French Basque Country, where Basque is not official, there is a steady decline in the bilingual population and a rise in monolingual French speakers.

Despite the general rise in competency of the Basque language in Euskadi, its public presence remains weak and there has even been a decline in the use of Basque in the domestic sphere. In Euskadi, 18.6% of the population uses Basque as much as or more than Spanish, and 70.4% uses only Spanish. These results reveal a situation of partial social bilingualism of a diglossic nature (Etxebarria 2003: 2).

It should be pointed out that until Basque was granted official status, it was limited to use within the family and among friends, which led to a “vicious circle whereby the minority language fails to generate the full range of terminology needed to cope with all aspects and domains of modern life” (O’Connell 2003a: 42). Becoming an official language broke this vicious circle and brought Basque into modernity and towards being on a par with Spanish. Basque could now be used in fields where it had never before been used, such as public administration, education or television, and this involved the huge task of adapting the language to these new communication needs. However, the relationship between Basque and Spanish continues to be disproportionate, and even the public administration of the Basque Autonomous Community has shortcomings in the treatment of Basque as an official language.

3. Basque-language television and linguistic standardisation

The organisation of the Spanish state into devolved regional governments permitted the linguistic decentralisation of the media in Spain and gave Basque and the other regional languages access to the media. This put an end to the almost complete invisibility of the regional languages during the Franco dictatorship (1939-1975). During this period, the state television, TVE, paid virtually no attention to Basque and until 1975 no Basque was heard on Spanish television, nor even acknowledgement of its existence. As noted by Díaz Noci (1998: 445; our translation): “In the seventies, regional centers were set up, and in the Basque Country, in Bilbao, the Telenorte news program included a few minutes of Basque each week.” This Basque language airtime lasted from 1975 until 1977 and since then Spanish Television has discriminated against Basque and continues to do so today. The attitude of the central administration has changed little since the arrival of democracy, continuing to opt almost exclusively for the monolingualism of the dictatorship. Not so in Catalonia, where the central administration gave unequivocal backing to the use of Catalan on state radio and television even though there were already regional television stations broadcasting in Catalan. In consequence, the Basque Government had a monopoly on the use of Basque on television until the appearance of local television stations in the early nineties.

It was in this setting that the Basque Parliament, in accordance with Article 19 of the Statute of Autonomy, passed a law on the 20th of May 1982 to create the Basque State Broadcaster, Radio Televisión Vasca – Euskal Irrati-Telebista. As a result, Basque State Television, ETB, began broadcasting on the 31st of December 1982. The rubric of the law recognises the key role of Basque State Television in the process of cultural identification and in the promotion and social integration of the standardised version of Basque. So it was that ETB set out to become a decisive factor in the construction of a national identity in its capacity as a “vital instrument for information and political participation for Basque citizens [and] an essential medium for cooperation with the state educational system and for the promotion and dissemination of Basque culture, keeping especially in mind the promotion and development of Basque” (BOPV 1982: 1250;[4] our translation).

The initial broadcasts by ETB made it clear that Basque was a minority language in the sphere of audiovisual media and with no clearly defined model of standard language supported by Basque society. When ETB began broadcasting, there was no standard model of spoken language and the written standard – developed as a model for literary language – was less than 15 years old and still in a process of consolidation.

Conscious of the need to promote and use a standard language that would be understood by most of the population, the Basque State Broadcaster adopted a policy in support of the standard language. Thus, the first ETB style guide, published in 1992, states that in news programmes unified Basque, or batua, must be used and if different versions or forms of a word exist, the version approved for standard Basque must be used. Subsequently, in 2005, ETB established quality standards for the use of Basque in various programming areas. These standards take unified Basque as a model and follow the rules set down by the Royal Academy of the Basque Language, though for the first time some room is given for the use of dialects:

Batua Basque is the standard working model for our presenters and reporters. As a general rule, as well as following the criteria and rules set out by the Euskaltzaindia for the use of unified Basque, presenters may enrich their standard speech with elements of their own regional dialects.

EITB 2006: 13;[5] our translation

Compliance with these rules is evident not only in in-house productions but also in dubbed audiovisual products. In terms of phonetic standards, there is close observance of the rules set down by the Euskaltzaindia for the careful pronunciation of standard Basque.

With respect to the educational function of audiovisual media, it should be pointed out that the media in general – and television in particular – make use of a wide variety of linguistic registers which may help to improve viewers’ spoken skills, especially in the case of children. Thanks to their enormous social impact, the media serve as the ideal means for the dissemination and transmission of vocabulary, since “providing media in a language puts large amounts of language use into the public domain, whether in print, video and audio recordings, or multimedia formats” (Cormack 2007: 55). Along the same lines, O’Connell (2003a: 60), in reference to the Irish case, recommends “the exploitation of Irish-language broadcasting and print as key media for the initial transmission and repeated reinforcement of new terminology, especially for the benefit of younger viewers.”

By opening Basque up to domains which were completely new to it and thanks to its vast influence on society, Basque State Television has made a direct contribution to the dissemination of certain structures and expressions which would otherwise have been much more difficult to spread throughout society. In the long process to consolidate unified Basque, ETB has been the principal vehicle for the transmission of the modern standard form. During its 28-year history, it has served as a cohesive force for the Basque-speaking community and a key player in the acceptance and implementation of a unified Basque language.

4. Main programming characteristics

Television programming creates a specific model of television which characterises each channel and sets it apart from other channels. In this respect, one of the factors which differentiates the Basque-speaking channel ETB1 from ETB2, which broadcasts entirely in Spanish, and from most other mainstream channels is the amount of time given to children’s programmes. Also noteworthy is the fact that within ETB, children’s programmes are broadcast only on ETB1. As such, there is a clear strategy centred on broadcasting children’s programmes in Basque with the aim of capturing a young audience and promoting the use of Basque from an early age. Something similar occurred in Ireland with TnaG (the Irish-language television channel, relaunched as TG4 in 1999), a clear manifestation of “the policy of preserving the language through concentrating on young people” (Watson 2003: 119). Another relevant factor in this policy to promote children’s programmes is the fact that nearly all are dubbed products, which means that “formats and content are frequently international, rather than domestic, in origin” (Cormack 2007: 56), and so have little connection with the local culture.

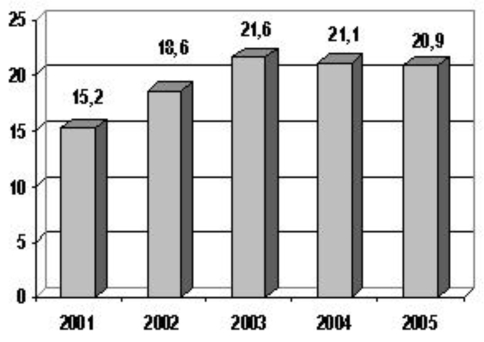

The special treatment given to this sector of the population has been a constant throughout ETB1’s history and is reflected in Figure 1 for the period of 2001-2005:

Figure 1

Airtime for children’s programmes (%)

The second characteristic of ETB1’s programming model is the scant time given to general fiction. This is precisely the type of programme to which other channels dedicate most airtime and, together with the miscellaneous category, forms the backbone of the programming content. This situation stands in stark contrast to ETB2’s programme selection: in 2008, fiction made up just 5.9% of airtime on ETB1, whereas it was 46.3% on ETB2 (Arana, Amezaga et al. 2010: 25).

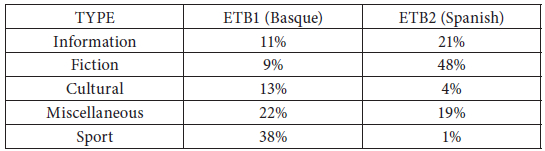

Finally, another characteristic feature of ETB1 is the emphasis given to sports programmes. While sports programming on ETB2 is almost negligible (0.3% in 2008), ETB1 uses a vast amount of human and economic resources on these programmes, which take up an average of 15% of airtime (16.92% in 1995-2000, 13.16% in 2001-2005, and 13.2% in 2008). The investment in sports is justified by its appeal for most of the audience and by the fact that not knowing Basque does not prevent viewers from being able to follow the programmes. In 2008, sports programmes brought in 38% of ETB1’s audience compared with 9% for fiction. Table 1 shows how the main programme types contribute to the viewing figures for each channel:

Table 1

Total audience by programme type in 2008

In light of these data, there is no doubt that each of the channels has been assigned a different function. While the Spanish-speaking ETB2 focuses on information and fiction, the Basque-speaking ETB1 is given over to sports and children’s programmes. As a result, the Basque-speaking channel shows a shortfall in fiction programming, specifically in series and feature films, although attempts have been made to make up for this with in-house productions. Rather paradoxically, this means that teenage viewers who want to see imported series or films are forced to switch channels and, in doing so, to switch languages.

This programming model is yet another example of the diglossic situation of Basque with respect to Spanish, and while Spanish-speaking viewers have access to a wide range of audiovisual programmes and types, Basque-speaking viewers are unable to watch most programmes in Basque. Furthermore, this diglossic situation continues on two levels: firstly, in contrast with ETB2, and secondly, in contrast with the rest of the mainstream channels which broadcast in Euskadi. It is striking that, as far as ETB1 and ETB2 are concerned, the Basque State Broadcaster is itself responsible for creating the imbalance between the programming on its two channels, in spite of the vast human and economic resources at its disposal.[7] The data seems to indicate that ETB has so far chosen not to offer a global service in Basque, thus aggravating the diglossic situation of Basque.

As a result of changes in the management of ETB following the regional government elections held in May 2009, and in response to the dismal audience figures for the Basque-speaking channel (May 2010 saw the lowest figures in its history with just 2%), the new directors introduced changes to ETB1 in an attempt to revitalise the programming and to turn it into a competitive mainstream channel. One of the changes affected children’s programmes, which were transferred from ETB1 to ETB3, a Basque language channel which started up in October 2008 with broadcasts targeted at children and young viewers. Accordingly, ETB3 has become the children’s channel of the Basque state television with an audience share of around 1%. ETB1 does not currently broadcast children’s programmes, which is again detrimental to ETB1’s nature as an all-purpose channel.

5. Translation policy and practice

Basque state television has been the main and almost exclusive client for AVT into Basque. The fact that demand depends on a single client has obvious risks since all work is subject to the priorities established by the powers that control the state television. As such, ETB plays a decisive role in the audiovisual market as the instigator of the dubbing process and is a determining factor when it comes to deciding upon “the set of foreign texts available to both the translator and to the readers in general of the translated text” (Carbonell 1999: 194; our translation). Consequently, the production and reception of translations is conditioned by the patronage (Lefevere 1992) operated by the Basque channel of the state broadcaster in so far as it provides the funding to support the AVT industry. In addition to controlling what is broadcast, ETB imposes linguistic control on all the translated products thus forcing the dubbing studios – and by implication the audiovisual translators – to comply with the quality standards required by the ETB language department. If dubbing studios do not meet these linguistic and artistic standards, they may risk losing their contract. Ultimately, this results in a high degree of control over the type of language present in translated audiovisual products.

The following sections describe how ETB has handled both dubbing and subtitling, and explain the underlying motivation for choosing one mode or another throughout ETB’s history.

5.1. Subtitling in Spanish

In its early years, ETB1 opted for subtitling foreign programmes in Spanish together with dubbing into Basque, so that viewers had access to two different versions of the same audiovisual product. To create the Spanish subtitles, translators used the Basque dubbing as the source text and not the original. This format for broadcasting foreign productions is quite unusual since viewers are presented with two target versions of the same original without being able to access the original text, and other national or regional broadcasters rarely use this practice.

The motivation behind it is clear. Since most of the viewers did not know Basque, the Spanish subtitles provided access for a substantial part of the population who otherwise would not have watched ETB. Another reason is that many Basque speakers found it difficult to understand the Basque used in the dubbing since it was quite different to their own varieties. For these Basque speakers the subtitles enabled them to follow the programmes. In addition to sociolinguistic reasons, there was also an educational motivation. Programmes in Basque subtitled in Spanish could aid the learning process of those people who were studying Basque, supporting and complementing the Basque that was being taught in schools.

This broadcasting format always drew strong criticism from wide sectors of the Basque-speaking community, who advocated a completely Basque television service. For Basque speakers, who also know Spanish, the presence of Spanish subtitles was more of a hindrance than a help since they found themselves distracted into making comparisons between what they heard and what they read. This format may be seen as reinforcing the domination of Spanish, as highlighted by O’Connell in the case of English subtitles in Irish language programmes:

Yet if minority language television carries major language subtitles as is the case with TG4’s English language subtitles on Irish programmes, new Irish technical and other terms are less likely to be picked up by viewers because they will be focused on the English language technical vocabulary in the subtitles.

O’Connell 2007: 214

During these early years, Spanish subtitles were also used in children’s programmes. Although, as pointed out by Karamitroglou (2000: 253), it is true that “from an educational point of view subtitling might prove better than dubbing not only because it promotes reading abilities but also because it accommodates fewer idiomatic expressions and anglicisms,” it is no less true that children view television as a means of entertainment and dubbing provides fairly effortless access for those who have not yet mastered reading fast enough or long enough to be able to follow subtitles. Consequently, it seems logical to favour dubbing because it requires less cognitive effort.

In any case, from 1991 onwards children’s programmes no longer included Spanish subtitles because, among other reasons, the bilingual education system had been in place for 10 years and children had by then a reasonably good knowledge of Basque. The creation in 1986 of ETB2, which was entirely in Spanish, meant that Basque State Television was broadcasting for the Spanish-speaking population of the Basque Country and there was little sense in maintaining the Spanish subtitles on ETB1, which were finally phased out in 1993.

5.2. Subtitling in Basque

Films in original version with Basque subtitles have been few and far between in ETB1’s programming. According to Larrinaga (2007: 98), subtitles were first used systematically for Buster Keaton comedies. Thirty films were broadcast over three seasons between 1983 and 1986. Later on, ETB1 made a bid to offer original language films with Basque subtitles from November 2000 to July 2001 with a series on Saturday nights called Klasikoak jatorriz [classics in original version] which included more than 30 films such as Casablanca, Doctor Zhivago or Last Tango in Paris. This bid to offer original language films with Basque subtitles was taken up again in 2010 on ETB3.

ETB1 does not only use interlingual subtitles but also makes use of intralingual subtitles in Basque. Currently, subtitles in standard Basque are used when the use of dialects could cause comprehension problems for the audience. The most well known case may be the pastoral plays or popular theatre performed in the Souletin dialect (spoken in the French region of Soule), which is hard to understand to the vast majority of Basque speakers. The use of standard Basque subtitles can serve as “a valuable instrument for giving over airtime to the speech forms furthest from what could be called common Basque” (Larrinaga 2000: 3;[8] our translation).

5.3. Dubbing

Dubbing is the most widely used translation form when broadcasting foreign programmes on ETB. There are various reasons why dubbing rather than subtitling is used. Firstly, when ETB came into being, there was no cinema production in Basque, and as such there was no audiovisual tradition or experience in the Basque-speaking world. As a result, everything had to be started from scratch in order to create local forms of audiovisual translation. This context, together with the need to start broadcasting as soon as possible, meant that the only viable option was to dub imported products. It was easier to train dubbing staff than it was to create the infrastructure required to produce programmes in-house, as discussed by Barambones (2006). This study analyses ETB1’s programming during its first ten years and highlights the overwhelming presence of imported productions: 62% compared to 38% in-house in 1987. The study also shows how the amount of dubbing begins to decrease from 1988 onwards as in-house productions gain more ground.

Another reason is connected to educational and linguistic issues. As Ávila (1997: 23; our translation) points out, “once democracy was established, dubbing in Catalan, Valencian, Galician and Basque […] became a key element for achieving linguistic integration and standardisation.” Aware of the role that dubbing could play in the standardisation and propagation of Basque, the Basque Government came down clearly in favour of dubbing rather than subtitling, since in order to standardize a language, “it is essential to control how it is spoken” (Ávila 1997: 23; our translation).

The third reason for promoting dubbing is a question of habit and what viewers are used to. As it is a common practice in Spain for films to be dubbed both in the cinema and on television, Basque speakers were used to viewing dubbed films (in Spanish), and dubbing was seen as the most convenient way to watch a film. Broadcasting foreign language material with Basque subtitles would have been poorly received since, as Danan (1991: 607) observes, “people seem to prefer whatever method they were originally exposed to and have resultantly grown accustomed to.” When compared to similar situations in Europe, one might think that a region the size of the Basque Country should have given more space to subtitling than to dubbing, which is more expensive. Yet, the choice of dubbing may also be explained by the fact that Basque television is part of the Spanish audiovisual system and the diglossic situation of Basque in that cultural system encourages the imitation of Spanish habits.

Finally, given ETB’s interest in the standardisation and promotion of Basque, for over 25 years ETB1 has given priority to children’s programming and, particularly, dubbed cartoons, which are not normally subtitled because younger children cannot read or do not read well enough to take in the information in the subtitles (O’Connell 2003b: 230).

With respect to the language model used in dubbed products, Barambones (2010) argues that in the case of cartoons dubbed into Basque, there is a notable degree of formality in terms of lexicon and morphosyntax. This strategy has a clear didactic goal and is related to the educational and standardising functions associated with Basque state television. However, this language model is ultimately a false didacticism since it makes use of forms which belong to the standard written form and not to the spoken register, rendering the audiovisual text less expressive and less credible. It seems clear that the search for an appropriate language model in Basque has not yet reached its conclusion. One of the reasons for this is the reduced amount of audiovisual production in Basque. Whereas literary production in Basque has served as a model for translations and literary translation itself has been an important factor in the development of a varied and modern literary language in Basque, the small amount of original audiovisual production in Basque has prevented the creation of similar synergies in this field.

6. Conclusions

AVT was of vital importance during the inception and subsequent evolution of Basque state television. The absence of a film industry to drive the production of original audiovisual work resulted in the decision to import and then translate and dub foreign productions. For the first ten years of ETB1’s existence “American series and feature films dominated the Basque television landscape and became the staple diet for its consumers” (Barambones 2006: 68).

At the same time, the political and cultural patrons of the time, aware of television’s educational and standardising power, gave priority to the dissemination of a specific language model to the detriment of other non-standard registers. The language policy and the excessive weight given to ETB’s role as an effective tool for learning and propagating Basque gave rise to a model of programming centred on improving linguistic quality and increasing understanding of Basque. The educational and standardising functions assigned to the Basque television channel are reflected in the special treatment given to children’s programmes over the last 25 years. However, this eagerness to promote Basque among the younger viewers has led ETB1 to deprive the adult audience of foreign productions, in contrast to other mainstream channels and especially its sister channel, the Spanish-speaking ETB2.

AVT in the Basque Country takes place in a complex social setting, a cultural system of dynamic forces populated by different agents defending their economic, political and cultural interests, and at a given moment within a historical context. Specific historical events paved the way for the first AVTs into Basque, which, once the censorship of the Franco dictatorship had disappeared and political power was decentralised, began to appear in a wider context of linguistic and cultural change. The political hegemony of Basque nationalism for the last 30 years has sought to recover and promote Basque by means of changes in legislation and in education, and through the creation of ETB, which was intended to play an important part in these linguistic and cultural changes.

However, AVT in the Basque Country takes on an ambivalent position within the cultural system, generating diverse, and even contradictory, effects at different crossroads. So, the promotion of standard Basque is part of an effort to establish a national language that has marginalised dialects in an uncomfortable parallel to the attempts made earlier under Franco’s rule to strengthen national unity by eliminating ‘peripheral’ languages. Similarly, the precedence given to the propagation of a correct standard form – understandable at the time, given Basque’s precarious position – has slowed the development of a working audiovisual language. The emphasis given to children’s and sports programmes in Basque and the lack of other programmes for adults (who can only watch them in Spanish) serves to strengthen rather than correct the diglossic imbalances. Finally, the Basque state broadcaster instigates cultural and linguistic change and innovation by promoting Basque (linguistic plurality as opposed to Franco’s monolingualism) but at the same time bolsters traditional cultural preconceptions by showing on ETB2 Westerns that were dubbed under the Franco censorship.

AVT on ETB is simply a reflection of the diglossic situation prevalent in the Basque Country. A comprehensive study of the control and censorship of (audiovisual) translations can be an interesting way of detecting and analysing cultural conflict and changing social norms. To achieve this goal, a thorough and wide-reaching descriptive work based on data collection is needed, which will ultimately enrich the theoretical underpinnings.

Through various studies, the TRACE project has examined the concept of censorship, a broad and complex concept which includes various mechanisms aimed at directing and controlling communication and discourse. In this sense, censorship and manipulation should be considered not only in the production of texts but also in their distribution and social propagation. As argued by Bourdieu (1991), it is in these domains that the role of informal (structural) censorship is especially relevant, above and beyond institutional censorship. Equally, the concept of censorship should be broadened by including other related concepts that impact upon social communication and on cultural development such as cultural planning, patronage, the mechanisms of canonisation, political correctness and the media as entertainment.[9] These concepts should allow scholars to reformulate and expand on work carried out in the ever changing field of AVT.

Parties annexes

Notes

-

[1]

University of the Basque Country, UPV/EHU, UFI11/06. Consolidated research group IT518-10, TRALIMA, funded by the Basque Government (Education, Universities and Research). Visited on 27 March 2012, <http://www.ehu.es/tralima>.

-

[2]

The TRACE (translation and censorship) research project has produced historical accounts of film translations, and a few Masters’ dissertations dealing with translations broadcast on Spanish television. The most recent works include a doctoral thesis on translations broadcast by ETB1, the Basque Public Television’s Basque language channel (Barambones 2010), and a Master’s dissertation which analyses the case of the second ETB channel, which broadcasts in Spanish. TRACE (FFI2008-05479-C02-02. is funded by the Spanish Ministry for Science and Innovation: Traducciones censuradas inglés/alemán-español (TRACE 1939-1985). Estudios sobre catálogos y corpus (Censored translations English/German-Spanish. Studies on catalogues and corpus, TRACE 1939-1985). Visited on 2. March 2012. <http://www.ehu.es/trace> and <http://trace.unileon.es>.

-

[3]

FORTA. Visited on 27 March 2012, <http://www.forta.es>.

-

[4]

BOPV (1982): Ley 5/1982, de 20 de mayo, de creación del Ente Público “Radio Televisión Vasca.” Boletín Oficial del País Vasco/Basque Country Official Gazette, no. 71, June 2, 1250-1262.

-

[5]

EITB (2006): Contracting-Programming Review 2002-2005. Euskal Irrati Telebista-Radio Televisión Vasca.

-

[6]

SGAE (2007-2009): Anuario SGAE de las artes escénicas, musicales y audiovisuales 2007-2009 [Spanish Society of Authors Report on the performing, musical and audiovisual arts]. Visited on 2 December 2010, <www.artenetsgae.com/anuario/anuario2007-2009/frames.html>.

-

[7]

ETB has more than 1,000 employees and a budget of 134 million euros for 2011.

-

[8]

Larrinaga, Asier (2000): La subtitulación en ETB-1. Mercator, Aberystwyth University. Visited on 27 March 2012, <http://www.aber.ac.uk/~merwww/images/asier.pdf>.

-

[9]

A couple of interesting examples of this attitude can be found in the censoring during the 2011 Oscars award ceremony of certain statements and scenes using the seven-second profanity delay and in the fact that the film The King’s Speech has been distributed in a censored version in the US in order to qualify for a PG-13 rating.

Bibliography

- Arana, Edorta, Amezaga, Josu and Azpillaga, Patxi (2010): Mass Media in the Basque Language. Vitoria-Gasteiz: Servicio Editorial de la Universidad del País Vasco. Visited on 2 December 2010, http://www.ehu.es/euskara-orria2/euskara/mas.asp?num=289.

- Ávila, Alejandro (1997): El doblaje. Madrid: Cátedra.

- Baeza, Juan de (1934): Hace falta una censura. Cinegramas. 1(4):1-4.

- Barambones, Josu (2006): A historical survey of Basque Television Foreign Programming: 1983-1992. Mercator Media Forum. 9:59-68.

- Barambones, Josu (2010): La traducción audiovisual en ETB1: Estudio descriptivo de la programación infantil y juvenil. Bilbao: University of the Basque Country.

- Basque Government (2008): Fourth Sociolinguistic Survey 2006. Vitoria-Gasteiz, Servicio Central del Publicaciones del Gobierno Vasco. Visited on 27 March 2012, http://www.euskara.euskadi.net/r59-738/en/contenidos/informacion/inkesta_soziolinguistikoa2006/en_survey/adjuntos/IV_incuesta_en.pdf.

- Bourdieu, Pierre (1991): Censorship and the Imposition of Form. In: John B. Thompson, ed. Language and Symbolic Power. (Translated by Gino Raymond and Matthew Adamson) Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 137-159.

- Cabanillas, Cande (2005): Traducciones de productos audiovisuales en ETB2: 1999-2003. Master dissertation, unpublished. Vitoria-Gasteiz: University of the Basque Country.

- Camus, Carmen (2009): Traducciones censuradas de novelas y películas del oeste 1939-1969. Doctoral thesis, unpublished. Vitoria-Gasteiz: University of the Basque Country.

- Carbonell, Ovidi (1999): Traducción y cultura. De la ideología al texto. Salamanca: Colegio de España.

- Cormack, Mike (2007): The Media and Language Maintenance. In: Mike Cormack and Niamh Hourigan, eds. Minority Language Media. Concepts, Critiques and Case Studies. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters, 53-68.

- Danan, Martine (1991): Dubbing as an expression of nationalism. Meta. 36(4):605-614.

- Díaz Cintas, Jorge (2001): Los Estudios sobre Traducción y la traducción fílmica. In: Miguel Duro, ed. La traducción para el doblaje y la subtitulación. Madrid: Cátedra, 91-102.

- Díaz Cintas, Jorge (2003): Book review: Ballester Casado, Ana (2001): Traducción y nacionalismo. La recepción del cine americano en España a través del doblaje (1928-1948). Granada: Editorial Comares. The Translator. 9(2):357-361.

- Díaz Noci, Javier (1998): Los medios de comunicación y la normalización del euskera: balance de dieciseis años. Revista Internacional de Estudios Vascos. 43(2):441-459.

- Etxebarria, Maitena (2003): Español y euskera en contacto. Linred: Revista Electrónica de lingüística. 1:1-16. Visited on 2 December 2010, http://www.linred.com/articulos_pdf/LR_articulo_10072003.pdf.

- Gambier, Yves (2003): Introduction. Screen Transadaptation: Perception and Reception. The Translator. 9(2):171-189.

- Izard, Natàlia (1999): Traducció audiovisual i creació de models de llengua en el sistema cultural català. Doctoral dissertation, unpublished. Barcelona: Universitat Pompeu Fabra.

- Izard, Natàlia (2001): La traducción audiovisual: registros lingüísticos, función y modelos de análisis. In: Eterio Pajares, Raquel Merino and José Miguel Santamaría, eds. Trasvases culturales 3: literatura, cine, traducción. Bilbao: Universidad del País Vasco, 399-405.

- Karamitroglou, Fotios (2000): Towards a Methodology for the Investigation of Norms in Audiovisual Translation. Rodopi: Amsterdam.

- Larrinaga, Asier (2007): Euskarazko bikoizketaren historia. Senez. 34:83-103.

- Lefevere, André, ed. (1992): Translation, Rewriting and the Manipulation of Literary Fame. Routledge: London.

- Merino, Raquel (2010): Building TRACE (translations censored) theatre corpus: some methodological questions on text selection. In: Micaela Muñoz and Carmina Buesa, eds. Translation and Cultural Identity: Selected Essays on Translation and Cross-Cultural Communication. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 116-138.

- O’Connell, Eithne (2003a): Minority Language Dubbing for Children. Screen Translation from German to Irish. Frankfurt: Peter Lang.

- O’Connell, Eithne (2003b): What Dubbers of Children’s Television Programmes Can Learn from Translators of Children’s Books? Meta. 48(1-2):222-232.

- O’Connell, Eithne (2007): Translation and Minority Language Media: Potential and Problems: An Irish Perspective. In: Mike Cormack and Niamh Hourigan, eds. Minority Language Media. Concepts, Critiques and Case Studies. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters, 212-228.

- Toury, Gideon (1999): Culture Planning and Translation. In: Alberto Alvarez-Lugrís and Anxo Fernández-Ocampo, eds. Anovar-anosar, estudios de traducción e interpretación. Vigo: Servicio de Publicacións da Universidade de Vigo, 13-26.

- Uribarri, Ibon (2010): German Philosophy in Nineteenth-century Spain: Reception, Translation, and Censorship in the Case of Immanuel Kant. In: Denise Merkle, Carol O’Sullivan, Luc van Doorslaer, et al., eds. The Power of the Pen: Translation & Censorship in Nineteenth-Century Europe. Vienna: LIT Verlag, 77-96.

- Watson, Iarfhlaith (2003): Broadcasting in Irish. Minority Language, Radio, Television and Identity. Dublin: Fourt Court Press.

Liste des figures

Figure 1

Airtime for children’s programmes (%)

Liste des tableaux

Table 1

Total audience by programme type in 2008

10.7202/002446ar

10.7202/002446ar