Résumés

Abstract

The aim of the study is to look into differences between broadcasting and newspaper news translation in their approaches to rendering the lead of the news report. For this purpose, the study analyzes shifts in English translations of Korean newspaper reports and compares them with the results of a previous study on broadcasting translation. The analysis suggests that while lead reduction is characteristic of broadcasting translation, lead expansion figures more prominently in newspaper translation. The paper gives a detailed account of these differences and offers some tentative explanations about what gives rise to them. It also discusses the differences in terms of the degree of latitude the translator exercises in editing the TT and their implications for different roles played by the translator in the two modes of translation.

Keywords/Mots-clés:

- news translation,

- register analysis,

- translator’s role,

- text type analysis,

- text structure

Résumé

À la suite de notre recherche qui a pour but d’examiner la traduction des chapeaux pour le journal télévisé, nous nous sommes penché sur la traduction des quotidiens. Nous avons d’abord examiné les modifications qui se produisent lors de la traduction des chapeaux coréens vers l’anglais pour la presse écrite et nous avons comparé les résultats de cette analyse à une étude antérieure sur la traduction pour le journal télévisé. Si les chapeaux deviennent plus courts lorsqu’ils sont traduits pour le journal télévisé, ils deviennent plus longs pour la presse écrite. Notre étude tente de proposer une explication plausible de ce phénomène, en tenant compte de facteurs tels que la marge de manoeuvre accordée au traducteur et les rôles variés joués par celui-ci selon le mode de la traduction.

초록

본 연구의 목적은 뉴스보도문의 리드 번역에 있어서 방송번역과 신문번역의 접근방식의 차이점을 규명하는데 있다. 이를 위하여 본 연구에선 한국신문 기사의 영역본에서 발생하는 shift를 분석하고 이를 이전의 방송번역에 관한 연구의 결과와 비교하였다. 분석 결과 리드 축소가 방송번역의 특징인데 반하여 신문번역에서는 리드 확장이 더 두드러졌다. 본 논문에서는 이러한 차이점을 상술하고 그러한 차이점이 발생하게 된 이유에 대한 잠정적인 의견을 제시하고 있다. 또한 TT를 변형시키는데 있어서 번역자가 행사하는 재량권의 정도의 차이와 그에 따른 각 번역형식에서의 번역자의 역할이 어떻게 달라지는지를 논하고 있다.

Corps de l’article

I. Introduction

This study aims to find out if there are any differences in the way Korean news reports are translated into English for newspapers and broadcasting, with the focus on shifts occurring in the ‘summary lead’ part of the news story. A summary lead is the first sentence(s) in a straight news story that serves to summarize the news event. By principle, a lead is to be written to include only the most important facts of the story.

A previous study (Lee, C.S. 2002) found that in broadcasting news translation the lead of the news report was often reduced in such a way that it was more concise and focused in English. Korean news reports tend to include in their leads information that is not part of the essential facts of the story. The study showed a high degree of consistency in removing this kind of information from the lead in the process of translation.

It is a well-known fact that broadcasting news writing places greater emphases on brevity than newspaper writing because the text is to be transmitted orally. For this reason, the lead of a broadcasting news report tends to be shorter and simpler in linguistic structure than that of a newspaper report. Conversely, it is not hard to find newspaper reports with leads too long and complex to be acceptable by broadcasting standards. In light of this, we can assume that ‘lead reduction’ may not occur in newspaper translation as frequently as in broadcasting translation.

The study investigates this hypothesis by analyzing English translations of Korean newspaper reports for comparison with the results of the previous study on broadcast news translation. The study, though dealing with language-specific translation problems, may have implications for general translation studies by illustrating how differences in mode of register (print vs. broadcasting reporting) can affect translation strategies (Halliday and Hasan 1989).

II. Background

2.1. American Language of Journalism & Its Global Spread

Clark (1994: 8), in his seminal work titled ‘the American Conversation and the Language of Journalism,’ characterized the modern American language of journalism as ‘front-loaded’ or ‘top-loaded.’ The most important facts are presented at the top, the least important at the bottom, in a structure popularly known as ‘inverted pyramid’. The rationale behind this form is that it offers the reader a quick grasp of the most important information, while enabling news editors to cut the story from the end without sacrificing crucial information.

Stories written in this format are headed by a summary lead, a quick round-up of the principal facts of the event reported in the story. The body that follows the lead, then, doles out details in declining order of importance. By principle, the summary lead should be brief and summarize the heart of the event reported. The length of typical summary leads is no more than 35 words, and it recounts the most important of the six basic elements of an event, the 5 W’s and H. (Itule and Anderson 1994: 58-60).

Despite frequently raised questions about its usefulness and a growing voice advocating feature-style writing, the inverted pyramid form still remains the mainstay of news writing in English.[2] According to a 2001 survey by the Readership Institute, American newspapers used the pyramid form for 71 percent of their stories on weekdays, with feature-style writing accounting for 16 percent (Readership Institute 2001: 6).

The spread of the Internet and web publishing is also reinforcing the inverted form’s importance for news writing. According to the ‘web usability’ guru Jakob Nielsen (1997a; 1997b), web users scan web pages instead of reading word by word, and they are impatient to ‘get their answers immediately.’ This explains why the inverted pyramid is the ‘story form of choice for most of the news on the Internet’ (Scanlan 2002).

It is not just the US or other English-language nations that are using the inverted pyramid form for news writing. The style has spread to the rest of the world over the last decades so that it is being practiced on a daily basis by journalists around the world. In discussing the influence of American journalism in Europe, Pietiläinen (2002: 96) quotes various sources to show that the inverted pyramid form, which was regarded as alien in the past, is now a standard in many countries like France and Sweden. He interprets this development as an offshoot of ‘cultural diffusion … of the Anglo-American model’, which is driving ‘an increasing move towards the standard that first developed in the USA and Britain’.

There is ample evidence indicating that Korean news media are also ‘Americanized’ to a large extent in the way they write reports. A quick glance through a Korean newspaper is sufficient to see that the inverted pyramid form is the standard choice for reporting everyday news events in Korea as well. Nearly all breaking news is reported in this style. For example, the Joongang Ilbo, one of the ‘Big 3’ national dailies in Korea ran 77 ‘news stories’ in the Feb 28, 2005 edition (excluding news briefs, background reports, features and interviews). Of them, 54 (70%) were in the inverted pyramid format. This is consistent with an observation by Yun & Kim (2000: 186) that approximately 80 percent of news items in Korean dailies are written in the inverted pyramid format. In addition, Korean textbooks on news writing invariably refer to American sources and practices as models, freely borrowing English terminology and jargon in explaining news writing principles (Yun and Kim 2000; Lee, J. K. 1998).

2.2. Previous Research on Differences in Summary Lead Structure between Korean and English

Despite the broad acceptance of the inverted pyramid style by Korean news media, evidence suggests subtle differences in the way the summary lead is written. In Korean news stories, the summary lead tends to include details that are not among the most important facts, such as names, titles, numbers and so forth. This makes the lead look unnecessarily long and cluttered by English standards.

For the translator working into English, this difference raises the question of whether to keep or remove the unessential details from the Korean lead. A recent study of my own (Lee, C.S. 2002) found that in broadcast news translation such details were consistently removed, which resulted in a lead reduced in content. Out of 24 instances in which the lead has been altered, lead reduction accounted for 15, outnumbering 9 instances in which the lead was expanded.[3]

Lead reduction occurred in 3 ways. The most frequent type, observed in 7 instances, involved deleting unessential background information carried by adjectival clauses. (In the example below, ST refers to the Korean ST presented here as a literal English translation, and TT to the English translation.)

The English lead is visibly shorter than the Korean. This, on top of other operations such as use of simpler syntactic structure and expressions, results from striking out the background information about Malaria, namely the fact that it ‘reappeared in Korea in1993.’

Second, when the lead contained too many news elements, some of the less important news elements were taken out. This type of reduction accounted for 5 occurrences.

In the above example, the Korean lead contains all the five W’s. ‘who’(the Seoul Metropolitan Government), ‘what’ (will alter….), where (Seoul, the Sonogsu Bridge), when (for a period from…) and why (‘for bridge expansion work’). The fact that this event is taking place in Seoul is not mentioned explicitly, but it can be clearly deduced by any Korean listener from the place proper nouns, ‘the Seoul Metropolitan Government’ and ‘the Songsu Bridge’. In contrast, the English lead reduces these to two elements, ‘what’ (Alternations will be made…) and ‘where’ (the Songsu Bridge).

The third type of reduction occurred through deleting the ‘attribution’, the source of the information reported. This occurred in 3 instances of reduction.

The Korean lead clearly states the source of the news by using the verb ‘announced’, complimented by the temporal reference ‘today’. This information is dropped in the English version.

There were also 9 instances of lead expansion. Three of them involved adding information from outside the ST to bridge the gap in background information to facilitate TT comprehension as illustrated in the example below.

In this example, the ‘Saemankum project’, the focus of the news, has been in the news for a long time in Korea. The assumed familiarity with the project explains why the Korean text makes no remarks on where the project is located. This information, however, cannot be presupposed for foreign listeners. So, the English translation added information explaining where the area is (‘in North Chollar Provice’) and specifying its geographical feature (the fact that it is a ‘tidal basin’). The added information is considered an essential part of the news if it is to make better sense to the foreign audience.

The second type of expansion involved transition in voice from ‘passive’ to ‘active’, resulting in the addition of the ‘Who’ element as exemplified below.

The Korean lead is built around what action will happen, without specifying the agent of the action. In contrast, the English lead adds an explicit ‘who’. This is made by shifting from passive to active voice. The operation, however, does not add much to the lead, thereby very limited in its effect on expanding the lead.

2.3. Differences in Lead Structure between Broadcasting and Newspapers

The study cited above shows a clear preference for shorter leads in broadcasting news translation. It is quite possible that the preference is influenced by the traditional emphasis placed by broadcasting news reporting in English on clarity, brevity and colloquial style in comparison to print news reporting (Itule and Anderson 1994: 566-567).

In fact, English newspaper reports are known to be more prone to longer leads than broadcasting. Consider the following CNN Radio and AFP reports covering the same news event. The AFP lead, almost double the CNN lead in length, has the noun ‘conference’ being modified by a lengthy present participle clause, plus the addition of an attribution. Modifying clauses of this kind are unlikely in the lead of a broadcasting report because they make the lead too long and too difficult for the announcer to recite without disrupting his breathing. Yet, they are very common in print news reports.

The fact that English newspapers often use longer and more complex leads than broadcasting gives rise to the following questions for the present study. ‘Does lead reduction occur so frequently in newspaper translation as in broadcasting translation?’ ‘Is there a possibility that the opposite is true, namely that the lead is expanded more often than reduced in newspaper translation?’ ‘Are there any differences in the circumstances under which the lead is either reduced or expanded between the two modes of translation?’ The following section summarizes the work I have done to find answers to these questions.

III. Methodology

The data analyzed in the present study was composed of translated English news reports and their corresponding Korean originals retrieved from the website of the Chosun Ilbo, one of the ‘Big 3’ national newspapers in Korea. (‘Ilbo’ means ‘daily newspaper’.)[4]

The English website of the Chosun Ilbo publishes news from two sources, translation of Korean news reports and ‘Arirang TV’, an independent satellite-based English television service. The English samples analyzed were clearly identifiable as translations. They matched the Korean original in content. In addition, most texts were identified by the name of the reporter who wrote the original Korean copy.

I first scanned English news stories dated between Jan. 1 and March 15, 2005 in the Biz/Tech area, and for those identifiable as translations I tracked down their originals by searching the Korean website. I then compared the two texts for shifts in the content of the lead. The samples thus collected amounted to 36 pairs.

IV. Data Analysis & Findings

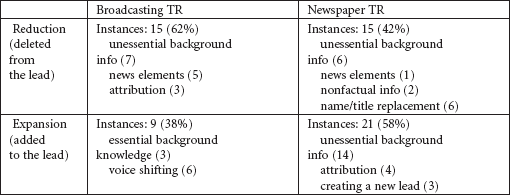

Data analysis showed that lead reduction did not occur as frequently as in broadcast news translation. Instead, more shifts involved expansion than reduction. Out of the 36 pairs, 15 (42%) involved reduction, and 21 (58%) expansions. This contrasts with the findings of the broadcast news translation study mentioned earlier (Lee, C.S. 2002) which pointed to the opposite, with reduction accounting for 15 (62%) and expansion for 9 (38%) out of a total of 24 pairs analyzed.

Not only was there a difference in the relative frequency of reduction and expansion but also the circumstances under which they occurred varied considerably between the two modes of translation as shown in Table 1.

Table 1

Differences in Lead Translation between Broadcasting and Newspapers

4.1. Lead Reduction

Lead reduction occurred basically in two ways – deletion and replacement. Deletion accounted for 9 instances of reduction. Of them, 6 resulted from striking out phrases or clauses containing background information unessential to the lead. This is exactly the same as the type illustrated by Example 1 in broadcasting translation. The information deleted from the lead was either lost for good or stated in a separate sentence after the lead. The following is an example of the first case.

The English translation took out of the ST lead the phrase ‘which is for creating …’ that modifies the noun ‘plastic surgery’. The phrase is equivalent to the non-defining relative clause in English that is not required to identify a person or an object but is there just to give additional information. The translator opted to delete this information for good. This compares with the example below where the same type of information is taken out from the lead but, instead of being discarded, is written into a separate sentence after the lead.

Other types of information than background-supplying phrases or clauses were also subjected to deletion. One involved removing news elements as illustrated by Example 2 in broadcast translation and two instances deleting nonfactual information. The following exemplifies the latter case. The translator deleted the part of the Korean lead that expresses a sense of expectation, a nonfactual, subjective statement that adds little to the factual summary.

The next type of reduction involved replacing lengthy references to persons or organizations with more general descriptions. This occurred in six instances.

In the example above, the English translation uses a general description to refer to the ‘Who’ element of the news, instead of ‘job title + personal name’ used in the Korean lead. The name and the job title are given in the next sentence after the lead. The effect that replacement had on reducing the lead was rather minimal compared to that resulting from deletion-based reduction.

4.2. Lead Expansion

As explained early, lead expansion was limited in broadcasting translation both in the types of operation involved and in the extent to which they actually expand the lead. In contrast, in newspaper transition, lead expansion was more pervasive and varied in the circumstances under which it occurred.

To be more specific, of the 21 instances of lead expansion, 14 instances resulted from adding information considered unessential to the lead. This is the exact opposite of Example 1 in broadcasting translation and Example 7 and 8 in newspaper translation in which unessential background information was deleted from the lead. Of the 14 instances, 4 involved adding background information from outside the ST.

In the example above, adding the information about the BBC report nearly doubles the length of the lead in English. There seems to be no compelling reason for this information to be included in the lead. It is not part of the core facts told in the lead. Nor does it seem motivated by the need to fill the gap in background knowledge for foreign readers as was the case in Example 4.

In the other 10 instances, the lead was expanded by moving forward information from the body into the lead.

In this example, the information about Bill Gates praising Reigncom, which was not part of the lead in the ST, was moved up into the lead in the TT.

Another type of lead expansion was typified by adding the attribution, the source of the news stated in the lead, as can be seen in the italicized part in Example 11. In the data analyzed in this study, this type of expansion occurred in 4 instances excluding Example 11.

Finally, three instances of lead expansion involved replacing the original with a completely different new lead. By principle, there is no law that the replaced lead should always be longer than the original, but that was the case in the present study. In all of these cases, the original Korean lead was suggestive rather than factual in summarizing the event, with more of a feature-style flavor than of a factual summary lead.

In this example, the translator discarded the lead of the Korean story and created a new lead for the English version by integrating the information supplied by the two sentences immediately after the lead in the Korean text. The result is a lead more factual in summarizing the situation reported in the story. The translator might have judged the Korean lead as lacking substance to serve as a summary lead.

V. Discussions

The findings reported above show that lead reduction does not occur in newspaper translation as frequently as in broadcasting translation. To the contrary, more instances involved shifts that resulted in lead expansion. So, it may be the case that lead expansion is more characteristic of newspaper translation. The greater frequency of lead expansion also indicates that in newspaper translation the translator is not so much restrained by concern with the length of the lead as in broadcasting.

What this shows is that in both cases the translator(s) is well informed of and guided by the different register styles preferred by the ‘oral’ and ‘written’ modes of news writing. Broadcast writing places greater emphasis than newspaper writing on brevity and simplicity, which appears to be the key to explaining the marked contrast in the translator’s attitude on the presence of unessential background information in the lead. In broadcasting news translation, such information was invariably deleted from the TT lead not just because of its lack of contribution to the lead but also possibly because of the structural complexity it creates by adding subjunctive or adjectival clauses to the lead sentence(s). In contrast, the newspaper translator often chose to add such information to the lead, creating a lead not only longer but also more complex than in the ST.

The two modes of news translation also differ greatly in the types of information added to the lead. In broadcasting translation, added information was limited to two cases in which it was judged either indispensable for contextualizing the news event for foreign readers (for example, explaining where a certain region is located in Korea) or inevitable as a result of syntactic modification (shifting from passive to active voice). In other words, added information was geared toward solving specific translation problems. In contrast, in newspaper translation, adding information to the lead appears to be more a matter of personal whim than compelled by a need to solve any specific translation problems.

This, coupled with the cases where the lead was completely rewritten, points to the fact that the newspaper translator was exercising greater latitude than the broadcast translator in deciding how the lead should be formed. This leads us to observe that there may be some differences in the role played by the translator in the two modes of translation. While both translators appeared to be fulfilling their traditional role as ‘cultural mediator’ and ‘decision maker’ (Leppihalme 1997: 19), the newspaper translator also acted much more visibly as a ‘gatekeeper’ (Vuorinen 1995; Fujii 1988) by taking advantage of greater freedom to determine what is to be included or excluded in the lead.

The greater discretion exercised by the newspaper translator in forming the news may also indicate that newspaper translation has greater scope for ‘managing’ (steering the situation in a direction favorable to the text producer’s goal) as opposed to ‘monitoring’ (giving an unmediated account of the situation) than broadcasting translation (Shunnaq 1994).

The relatively small size of data analyzed for this study, however, prohibits me from making conclusive remarks about any of the points above. Future research will have to employ a larger corpus and a more elaborate statistical analysis to shed more credible light on the points raised in this paper.

Parties annexes

Biography

Chang-soo Lee

Prof. Lee is currently a professor at the Graduate School of Interpretation & Translation, Hankuk University of Foreign Studies, Seoul, Korea. As a graduate of the GSIT, he earned his Ph.D. from Boston University in Applied Linguistics in 1996, with specialization in discourse and conversation analysis. His research interest in translation studies has focused on issues relating to discourse and text linguistic analysis.

Notes

-

[1]

This work was supported by Hankuk University of Foreign Studies Research Fund of 2006.

-

[2]

‘Hard’ news generally refers to breaking news and events. Its main goal is to describe WHO did WHAT, WHERE, WHEN, HOW and WHY. In comparison, ‘soft’ news is features such as human-interest stories that are written to advise or entertain the reader. But the distinction is not always clear-cut.

-

[3]

The data analyzed in this 2002 study was extracted from a bilingual Korean-English news program aired daily on KBS Radio 1. The program runs about 6 or 7 minutes. For each news item, the Korean report precedes the English version, which an internal source confirmed as a translation of the Korean version. The data consist of 35 pairs of Korean and English reports recorded on randomly selected nine days.

-

[4]

Initially, I planned to use samples from all three newspapers since they all publish English news online. But I had to give up the other two newspapers because they did not serve the purpose of this research very well. One (the Donga Ilbo) relied on literal translation to such an extent that no structural shifts were observable between Korean and English. With the other one (the Joongang Ilbo) that publishes an English newspaper, it was hard to find English texts that were actual translations of Korean reports without too much editing.

References

- Lee, J.-K. (1998): Basic News Writing and Reporting, Seoul, Namwu-wa-swup.

- Yun, S.-H. and C.-O. Kim (2000): Newspaper and Broadcast Coverage and Reporting, Seoul, Naman.

- Clark, R. P. (1994): The American Conversation and the Language of Journalism, St. Petersburg, Florida, The Poynter Institute for Media Studies.

- Fujii, A. (1988): “News translation in Japan”, Meta 33-1, p. 32-37

- Halliday, M. A. K. and R. Hasan (1989): Language, Context, and Text: Aspects of Language in a Social-semiotic Perspective, Oxford, Oxford University Press.

- Itule, B. D. and D. A. Anderson (1994): News Writing and Reporting for Today’s Media, New York, McGraw-Hill.

- Lee, C.-S. (2002): “Strategies for translating Korean broadcast news reports into English”, Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Translation and Interpretation Studies, Seoul, Korea, Graduate School of Interpretation and Translation, HUFS, p. 93-111

- Leppihalme, R. (1997): Culture Bumps, Clevedon, Multilingual Matters Ltd.

- Nielsen, J. (1997a): “Changes in Web Usability since 1994”, <http://www.useit.com/alertbox/9712a.html>.

- Nielsen, J. (1997b): “How Users Read on the Web”, <http://www.useit.com/alertbox/9710a.html>.

- PietilÄInen, J. (2002): The Regional Newspaper in Post-Soviet Russia – Society, Press and

- Journalism in the Republic of Karelia 1985-2001, An Academic Dissertation, Finland, Tampere University Press.

- READERSHIP INSTITUTE (2001): “Newspaper content – what makes readers more satisfied”, Report by Readership Institute, Media Management Center at Northwestern University, <http://www.readership.org/content/editorial/data/what_content_satisfies_readers.pdf>

- Scanlan, C. (2002): “The Web and the Future of Writing”, <http://www.poynter.org/dg.lts/id.14501/content.content_view.htm>.

- Shunnaq, A. (1994): “‘Monitoring’ and ‘Managing’ in Radio News Reports”, In R. De Beaugrandeet al. (eds.), Language, Discourse and Translation in the West and Middle East, Amsterdam/Philadelphia, p. 103-114, <http://www.poynter.org/content/content_view.asp?id=14501>.

- Vuorinen, E. (1995): “News Translation as a Gatekeeping”, In M. Snell-Hornby et al. (ed.), Translation asIntercultural Communication, Selected papers from the EST Congress, Prague 1995, Prague, Amsterdam, John Benjamins Publishing Company, p. 325-338.

Korean

English

Liste des tableaux

Table 1

Differences in Lead Translation between Broadcasting and Newspapers

10.7202/002778ar

10.7202/002778ar