Résumés

Abstract

Are assessment tools for machine-generated translations applicable to human translations? To address this question, the present study compares two assessments used in translation tests: the first is the error-analysis-based method applied by most schools and institutions, the other a scale-based method proposed by Liu, Chang et al. (2005). They have adapted Carroll’s scales developed for quality assessment of machine-generated translations. In the present study, twelve graders were invited to re-grade the test papers in Liu, Chang et al. (2005)’s experiment by different methods. Based on the results and graders’ feedback, a number of modifications of the measuring procedure as well as the scales were provided. The study showed that the scale method mostly used to assess machine-generated translations is also a reliable and valid tool to assess human translations. The measurement was accepted by the Ministry of Education in Taiwan and applied in the 2007 public translation proficiency test.

Keywords:

- translation test,

- error-analysis,

- assessment scales,

- translation evaluation,

- evaluation criteria

Résumé

Les outils d’évaluation des traductions automatiques sont-ils applicables à la traduction humaine ? Pour répondre à cette question, la présente étude compare deux modalités d’évaluation : la première est la méthode d’analyse des erreurs utilisée par la plupart des écoles et des institutions, la seconde fait appel à une échelle basée sur la méthode proposée par Liu, Chang, et al. (2005). Ces auteurs ont adapté les échelles d’évaluation de la qualité des traductions de Caroll. Dans la présente étude, douze évaluateurs ont été invités à ré-évaluer les textes utilisés dans les travaux de Liu, Chang, et al. (2005) par différentes méthodes. Sur la base des résultats obtenus et des commentaires des évaluateurs, un certain nombre de modifications ont été apportées à la méthode de mesure ainsi qu’aux échelles. L’étude a montré que la méthode fondée sur l’échelle principalement utilisée pour évaluer les traductions automatiques constitue un outil fiable pour évaluer les traductions humaines. Cette méthode a été acceptée par le ministère de l’Éducation de Taïwan et appliquée en 2007 pour les tests du certificat de traduction.

Mots-clés :

- tests de traduction,

- analyse des erreurs,

- échelles d’évaluation,

- qualité des traductions,

- critères d’évaluation

Corps de l’article

1. Introduction

How does one evaluate a translation in an examination setting? The most widely used method seems to be the time-honored error-deduction formula: an evaluator marks errors and deducts from a starting score for any error he or she observes. Inevitably, the systems vary considerably. For example, there are 22 categories of errors in the Framework for Standardized Error Marking of American Translators Association (ATA). Any single error can cost an examinee 2 to 16 points out of a total of 180. The marking scale of Canadian Translators, Terminologists and Interpreters Council (CTTIC) is much simpler – there are basically only two categories: translation errors and language errors. A major translation error deducts 10 points from 100, and a minor one, 5 points; a major language error also deducts 10 points, but a minor one can deduct 5 points or 3 points.[1] Irrespective of the number of categories, these marking schemes share certain common problems. For example, can the summation of points deducted represent the true quality of a translation? As McAlester (2000: 235) previously noted, “the mere summation of errors in a translation has often not corresponded with my subjective evaluation of it.” Williams (2001: 326) has also pointed out that “the establishment of an acceptability threshold based on a specific number of errors is vulnerable to criticism both theoretically and in the marketplace.” If a test involves hundreds of examinees and dozens of graders,[2] such a method may lead to more problematic issues, such as a lack of consensus and a lack of consistency. While one grader may perceive an error as serious, another may feel that it is minor or even trivial. Furthermore, very few graders are able to guarantee consistency in their decision making throughout the entire evaluation process since it may take anywhere from several days to several weeks to complete the entire process.

In 2003, Taiwan’s Ministry of Education decided to launch the first public translation and interpretation proficiency test by the end of 2007, and a research team for the test was formed.[3] Although various tests for certification in the field of translation have taken place around the world for decades, there has been very little research devoted specifically to the Chinese-English language pair. China, the biggest Chinese-speaking country, only launched the China Aptitude Test for Translators and Interpreters (CATTI) in 2003; to date, there had been no explicit explanation of the evaluation method used in this particular aptitude test (Mu 2006: 469).

The research team in Taiwan was first headed up by Minhua Liu, the former director of Taiwan’s first graduate institute of translation and interpretation. Having been involved in the professional examination framework used by that institution for years, Liu decided to forgo the error-deduction system altogether. Instead, she adapted scales that were originally designed by Carroll (1966) to assess the quality of both human and machine translations. In Carroll’s as well as Liu’s scales, the unit of measurement was taken to be a single sentence instead of the entire text. There were two 5-point scales used in Liu’s measurement criteria; one of these scales was Readability (tongshun 通順) and the other was Fidelity (zhongshi 忠實).[4] Each sentence was given a grade for its Readability and a grade for its Fidelity. Both grades for all sentences were then summated and converted to percentages.

Liu recruited 193 students from 10 classes of three universities in Taiwan to participate in her study. The result showed that the reliability among Fidelity graders was satisfactory, but less so among Readability graders with only medium correlation. The Readability scale was apparently not as reliable as the Fidelity scale. In terms of validity, Liu used seniority (junior, senior students or graduate students) and subject major (English major or translation major) as external criteria. However, since the subjects were picked from different universities, the performance of some junior students from one university might be better than senior students of another university. Students majoring in translation were not necessarily better than those majoring in English. Seniority and subject major as a result proved to be rather unreliable and confusing external criteria.

2. Research purpose

As Williams (1989: 16) said, “[v]alidity and reliability have to be maximized if the TQA [translation quality assessment] system is to be accepted in the field.” Since Liu’s measurement was designed for Taiwan’s public translation proficiency test, two questions had to be tackled before its application: how to improve the reliability of the Readability scale, and how to prove the validity of such a system.

To address the first question, we modified the grading procedure. In her research, Liu recruited two teams of raters, one for Readability and the other for Fidelity. The Readability category raters were not given the source text. They were asked to read the translations as TL texts. The system appeared reasonable, but some of the raters complained of the difficulties in evaluating a translated piece without the source text.[5] Another problem was that, after correcting a dozen papers, an experienced teacher or translator could easily figure out the original message even without the aid of the source text. Once a rater suspected serious misunderstandings in a sentence, he or she might hesitate to give it a high score in readability even if it was clear and highly readable. So we had the same raters score both Readability and Fidelity.

As for the second question, we were inspired by the research by Waddington (2001). In that research, 5 reviewers were asked to evaluate the translations of 64 students by 4 different methods. The researcher tried to use 17 external criteria to decide which method was the most reliable. To his surprise, “the four methods have proved to be equally valid in spite of the considerable differences that exist between them” (Waddington 2001: 322). We decided that if the external criteria were not reliable enough, we might prove the validity of the scales by comparing it with other practices. Therefore, we recruited two teams of raters. One team graded the papers based on the error analysis method, and the other graded the same papers by the scales.

3. The procedure

The examinees’ papers of Liu’s research were re-used. In her research, there were 193 subjects in total. Among the 97 English-Chinese papers, we selected 30 covering each grade interval. As for the 102 Chinese-English papers,[6] since the grades of all the papers fell below the passing grade of 80, we only selected 26 papers by the students and asked 4 qualified translators to produce new papers. The total number of Chinese-English papers was also 30. The length of the English text to be translated was 242 words and that of the Chinese text to be translated was 398 characters.[7]

A workshop was organized in July 2007, in which 12 experienced translation teachers and professional translators were invited as raters. The raters were given a 2-hour session of instruction and practice before they began to grade. They were then divided into four groups. Three raters were required to grade 30 English-Chinese papers by the error-marking method; three were to grade the same papers by the scales. The other six raters followed suit for the Chinese-English papers.

After the workshop, we adapted the two measures proposed by Stansfield, Scott, et al. (1992) and relabeled the criteria as Accuracy (xunxi zhunque 訊息準確) and Expression (biaoda fengge 表達風格) instead of Fidelity and Readability, defining grades 1 through 6 for the former and 1 through 4 for the latter based on the results and raters’ feedback. To avoid confusion, we called the measurement of the workshop 5/5 scales and the latest version 6/4 scales. We then invited two raters for each direction to evaluate the same papers by 6/4 scales.

As a result, we collected the following scores for each paper:

From Liu’s original research project;

By 3 raters using error-analysis method in the workshop;

By 3 raters using 5/5 scales in the workshop;

By 2 raters using 6/4 scales after the workshop.

The four methods are briefly described as follows:

Liu’s scales: In Liu’s research, 2 raters scored a paper, sentence by sentence, for its Readability (Table 1) and another 2 raters scored the same paper, also sentence by sentence, for its Fidelity (Table 2) against the original text. Each rater used a scale from 1 to 5, 5 being the best and 1 the worst;

Tableau1

Liu’s Fidelity scale

Tableau 2

Liu’s Readability scale

-

Error-analysis method in the workshop:

For misunderstanding: penalized from 2 to 8 points for each error;

For inappropriate usage, register, style: penalized 1 point for each error;

For misspelling (for English), wrong characters (for Chinese), punctuations – penalized 1 point for each error;

For sound solutions to translation difficulties or good style: rewarded 1 or 2 points;

The full mark is 100 points and the passing grade is 80;

The scales used in the workshop (5/5 scales): We basically adopted the scales designed by Liu, yet each rater was asked to score both Fidelity and Readability;

The scales revised after the workshop (6/4 scales): In the workshop, many raters suggested that we revise the scales and put more weight in the Accuracy category, the reason being that they found some well-written sentences that conveyed a totally different message from the original. According to our 5/5 scales, such sentences should be scored 6 points in total (1 for accuracy and 5 for expression). But most of the raters declared that it would be unacceptable for such a sentence to get 6 points out of 10. Some raters even argued that, if the message was totally wrong, it was pointless to score its readability. Since the public translation test is restricted to non-literary texts, the research team agreed to add more weight on accuracy. We revised the scales accordingly. In the latest scales, there were six grades for Accuracy (Table 3) and four grades for Expression (Table 4). By doing so, we also hoped to increase the reliability of the Expression scale since raters tended to give the same scores when there were only 4 grades available rather than 5.

Tableau 3

The Accuracy scale for 6/4 scales

Tableau 4

The Expression scale for 6/4 scales

4. The hypotheses

Our original hypotheses before the workshop were:

The reliability between raters will be improved if we change the procedure and make the same raters score both Accuracy and Expression;

The results of both methods (error analysis and scales) are similar, so the scale method is valid in assessing human translations.

After the workshop, we made a slight modification over the first hypothesis. The new version was:

If the same raters score both Accuracy and Expression, and the ratio of the two criteria is 6 to 4, the reliability between raters will be improved.

5. Results

5.1. English to Chinese

The four scores[8] we collected for the 30 sample papers are shown in Table 5.

Table 5

Scores of English-Chinese papers

We found that 5 students out of 30 would pass the exam if graded by Liu’s scales. The pass percentage by Liu’s method was the highest among the four methods here. The average score was also the highest (74.2/100). We assumed that it was because in Liu’s research, Readability and Fidelity were graded by two different teams of raters, the final score of a certain paper was probably higher. Even if one paper was marred by serious and frequent mistranslations, it might be scored high in Readability if it read well. The total score of such a paper by Liu’s method was very likely to be higher than if it was graded by error-analysis formulas.

Table 6

Inter-rater correlations of English-Chinese papers

The highest correlation was found between raters of 6/4 scales (0.786). There were moderate to high correlations between raters of the other two methods in the workshop (0.602–0.735). In Liu’s research, the correlations between raters of Readability ranged from 0.256 to 0.811 (Liu, Chiang et al. 2005: 99). Therefore, 6/4 scales proved to be a more stable and reliable assessment tool.

Table 7

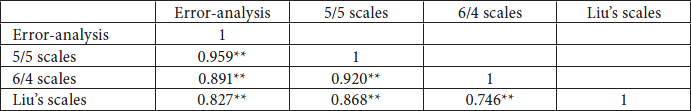

Correlations among methods (English-Chinese group)

In Table 7, we found that all three methods in our research indicated high correlations (r>0.8). Thus all three methods proved valid. However, there was only a moderate correlation between the three methods and Liu’s scales (0.595–0.615). It appeared that if a paper was assessed separately by two raters (one for accuracy and one for expression), the result might be different from other methods.

Table 8

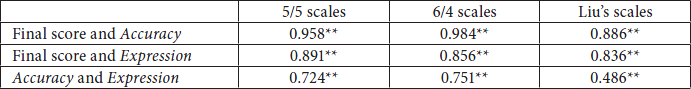

Correlation of the criteria (English-Chinese group)

All the correlations between the final score and Accuracy by the three sets of scales were very high (0.886–0.958) and all higher than that between the final score and Expression. It appeared that Accuracy was the more valid measure of translation ability, just as Stansfield, Scott et al. (1992: 461) concluded. This finding supported our decision to weigh on Accuracy over Expression. In terms of the correlations between the two scores, both 5/5 scales (0.724) and 6/4 scales (0.751) were higher than Liu’s scales (0.486). Actually, the correlations between the two criteria by 5/5 scales and 6/4 scales were quite close to what Stansfield, Scott et al. (1992: 461) found. In that study, the correlations between Accuracy and Expression were 0.74 to 0.75. Given our teaching experience, we believe that the two scores related is reasonable: a student who is good at reading in English is often, though not always, good at expression in Chinese; while a student who is poor at reading in English tends to be weak in expression even in Chinese, his or her native language.[9]

5.2. Chinese to English

The scores of the Chinese-English translations are shown in Table 9. Since in Liu’s study, no one passed the exam in this direction, we prepared 4 papers for this study. The average score by Liu’s scales figured at the lowest since the four best papers were absent. The average scores by the two sets of scales used in the present study were close (65.7 and 65.1).

Table 9

Scores of Chinese-English papers

As for the inter-rater correlation (Table 10), just like the English-Chinese section, the highest correlation was also found between raters of 6/4 scales (0.832). It seemed the raters using scales were more likely to reach a consensus than those who adopted the error-analysis method. In Liu’s study, the inter-rater correlations were moderate to high (0.563–0.722) for Fidelity and moderate to high (0.587 – 0.765) for Readability (Liu, Chang et al. 2005: 108-109). The inter-rater correlations of the two scale methods in the present study were all higher than those in Liu’s study.

Table 10

Inter-rater correlation of Chinese-English papers

Similar to the results of the English-Chinese papers, the three methods used in the present study reached high correlation (r > 0.8), so the marking for all three methods was valid (Table 11). But the results of the three methods also reached high correlation with Liu’s scales, indicating that the four methods differed little. This may be explained by the fact that none of the 26 papers was of high-quality. Since the subjects were university students and native speakers of Chinese, the translations into Language 2 were unsatisfying. In Waddington’s (2001) experiment, the students were also asked to translate into English, not their native language. The four methods in that study also showed very high correlations (from 0.822 to 0.986).

Table 11

Correlations among methods (Chinese-English group)

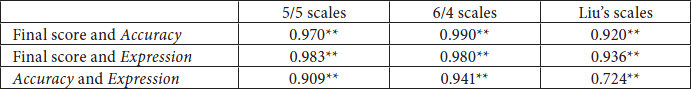

In all three scale methods, the correlations between the two criteria and the final score were very high (Table 12). There were also very high correlations between Accuracy and Expression in the two sets of scales for the present study. Although we believed the two scores should be related to a certain degree, the fact that the two scores can almost replace each other was worrying. It seemed that the scales failed to distinguish the two different constructs.

Table 12

Correlation of the criteria (Chinese-English group)

According to some raters, the two scores were highly correlated because too many sentences conveyed no meaning at all and it was difficult for them to judge whether it failed in expression or accuracy. If more native speakers of English and qualified translators were to attend the public exam, the correlation between the two scores might be lower.[10]

6. Conclusion

To provide a more reliable evaluation tool for Taiwan’s first public translation exam, we made several changes over Liu’s scales:

We made one rater score both criteria instead of two raters;

We changed the ratio of the two scales from 5/5 to 6/4, with emphasis on Accuracy.

And to prove the scales as a valid instrument for assessing translations in the exam, we compared the scales with the error-analysis method.

In both English-Chinese and Chinese-English groups, the inter-rater correlations of 6/4 scales were the highest. Our first hypothesis was verified. If we change the procedure and make the same raters score both Accuracy and Expression, the reliability among raters will be improved. 6/4 scales proved to be a reliable tool for evaluating translation exams.

For validity, our hypothesis was also verified. In the English-Chinese group, all three methods used in the present study showed high correlations, proving all three methods to be valid. In contrast, the correlations between Liu’s scales and other methods were only moderate.

However, the results from the Chinese-English group told a different story – all four methods showed high correlations. Although 6/4 scales still proved a valid tool, it seemed the result was almost the same whether Accuracy and Expression were evaluated separately by two raters or together by one rater. Since all the examinees were Chinese-speaking, it is possible that this result was affected by the fact that these examinees were translating into their second language. Admittedly, 6/4 scales may not be an ideal measurement for teaching translation into L2. The reason for this is that the dominant factor for translation into L2 is actually writing competence in L2 rather than L1 comprehension. Thus, the use of only four grades in the Expression category may not be enough to distinguish good learners from bad ones. However, for a large-scale test, 6/4 scales still proved to be an effective and consistent evaluation tool.

The high correlation between Accuracy and Expression in the Chinese-English group remained alarming however. Whether it reflected the nature of translation (the two competences were highly related) or a design glitch (the raters failed to consider two criteria separately) would demand further research.

Parties annexes

Notes

-

[1]

Williams (2004) has reviewed various existing quantitative systems. Secară (2005) also conducted a quite comprehensive survey of the error-annotation schemes.

-

[2]

In the translation exam of Taiwan in December 2007, more than 750 examinees took the exam and 2. graders were engaged to score more than 2000 papers (each examinee had 1 to 4 papers and each paper was scored by 2 graders). The grading process lasted over 2 weeks.

-

[3]

Taiwan’s first public translation exam was held by the Ministry of Education. The preparation work started four years before that and several research projects were conducted. Both Liu’s research and the present research were funded by the National Institute of Compilation and Translation. After 2006, Liu’s research focused on interpretation testing rather than translation testing.

-

[4]

Carroll’s scales of Intelligibility and Informativeness both ranged from 1 to 9, while both of Liu’s scales ranged only from 1 to 5. According to Carroll’s scales, 9 points in Intelligibility meant “perfectly clear and intelligible,” but 9 points in Informativeness meant “the translation conveys completely different meaning from the original.” To avoid confusion, Liu reversed the scale of Informativeness. In Liu’s scales, 5 points in Readability meant “the translation is perfectly clear and readable” and 5 points in Fidelity meant “the translation conveys all the meaning of the original.”

-

[5]

In Rothe-Neves (2002), the participant reviewers had a similar response. In the study, he asked 5 professional translators to evaluate 12 Portuguese translations of the same English text without giving them the original text. He wanted to prove that the quality of a translation could be judged without the source text, but some reviewers complained that “errors were not systematic approached” (Rothe-Neves 2002: 126).

-

[6]

Several students took the exams in both directions.

-

[7]

There were two English texts and three Chinese texts in Liu’s study. We only selected one English text and one Chinese text.

-

[8]

Each of the four scores was the average score of all raters using that method.

-

[9]

Of course, this principle is not applied to beginners of language learning.

-

[10]

According to the tentative statistics, in the official test of 2007, the correlations between Accuracy and Expression of Chinese-English papers did fall between 0.7 and 0.8.

Bibliography

- Carroll, John (1966): An experiment in evaluating the quality of translations. In: John Pierce, ed. Language and Machines: computers in Translation and Linguistics. Report by the Automatic Language Processing Advisory Committee (ALPAC). Publication 1416. Washington: National Academy of Sciences / National Research Council, 67-75.

- Liu, Minhua, Chang, Wuchang, Lin, Shihhua, et al. (2005): Jianli guojia zhongyingwen fanyi nengli jianding kaoshi pingfen yu mingti jizhi [A Study on the Establishment of National Assessment Criteria of Translators and Interpreters]. Taipei: National Institute of Compilation and Translation.

- McAlester, Gerard (2000): Translation into a Foreign Language. In: Christina Schäffner and Beverly Adab, eds. Developing Translation Competence. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 229-241.

- Mu, Lei (2006): Fanyi ceshi ji qi pingfen wenti [Translation testing and grading]. Waiyu jiaoxuei ji yenjiu [Foreign Language Teaching and Research]. 38(6):466-480.

- Rothe-Neves, Rui (2002): Translation Quality Assessment for Research Purposes: An Empirical Approach. Cadernos de Tradução. 2(10):113-131.

- Secară, Alina (2005): Translation Evaluation – a State of the Art Survey. Proceeding of the eCoLoRe/MeLLANGE Workshop. Leeds: 39-44.

- Stansfield, Charles, Scott, Mary and Kenyon, Dorry (1992): The Measurement of Translation Ability. The Modern Language Journal. 76(4):455-467.

- Waddington, Christopher (2001): Different Methods of Evaluating Student Translations: The Question of Validity. Meta. 46(2):311-325.

- Williams, Malcolm (1989): Creating Credibility out of Chaos: The Assessment of Translation Quality. Traduction, Terminologie, Rédaction. 2(2):13-33.

- Williams, Malcolm (2001): The Application of Argumentation Theory to Translation Quality Assessment. Meta. 46(2):326-344.

- Williams, Malcolm (2004): Translation Quality Assessment: An Argumentation-Centred Approach. Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press.

Liste des tableaux

Tableau1

Liu’s Fidelity scale

Tableau 2

Liu’s Readability scale

Tableau 3

The Accuracy scale for 6/4 scales

Tableau 4

The Expression scale for 6/4 scales

Table 5

Scores of English-Chinese papers

Table 6

Inter-rater correlations of English-Chinese papers

Table 7

Correlations among methods (English-Chinese group)

Table 8

Correlation of the criteria (English-Chinese group)

Table 9

Scores of Chinese-English papers

Table 10

Inter-rater correlation of Chinese-English papers

Table 11

Correlations among methods (Chinese-English group)

Table 12

Correlation of the criteria (Chinese-English group)

10.7202/004583ar

10.7202/004583ar