Résumés

Abstract

Drawing upon the theory of reception aesthetics, this paper aims to systematically explore the news translator’s subjectivity and the constraints involved in transediting hard news texts. The translator, who actively receives, selects and conveys information, plays a decisive role in striking an appropriate balance between accuracy and acceptability during the transediting process. By optimally exerting his/her subjectivity, the translator can produce appropriate target news that communicate effectively. Interest in the translator’s subjectivity has continued to grow since the cultural turn in translation studies which introduced a range of new approaches. These either focus exclusively on the translator’s subjectivity or emphasize the constraints impinging upon it, but, in either instance fail to provide a comprehensive account. In contrast, the theory of reception aesthetics, which takes both aspects into account, provides a more thorough theoretical framework. This paper first performs a theoretical analysis of the reciprocity between the translator’s subjectivity and its corresponding constraints. A case study on English-Chinese news transediting in the Taiwanese press is then conducted to further explain how to apply the theoretical analysis in order to examine and assess the translator’s constrained subjectivity in actual transediting practice.

Keywords:

- reception aesthetics,

- news transediting,

- translator’s subjectivity,

- constraints

Résumé

S’appuyant sur la théorie de l’esthétique de la réception, le présent article vise à explorer rigoureusement la subjectivité du traducteur de nouvelles, ainsi que les contraintes de la transédition de textes faisant état des actualités. Le traducteur, qui reçoit, sélectionne et transmet les informations de manière active, joue un rôle décisif dans la recherche du juste équilibre entre exactitude et acceptabilité au cours du processus de transédition. En exerçant sa subjectivité de manière optimale, le traducteur peut produire des nouvelles efficaces sur le plan communicatif. L’intérêt à l’égard de la subjectivité du traducteur n’a cessé de gagner du terrain depuis le tournant culturel de la traductologie, qui a permis l’émergence de nouvelles approches. Toutefois, celles-ci se concentrent exclusivement sur la subjectivité du traducteur ou sur les contraintes dont elle fait l’objet, mais dans les deux cas, elles ne réussissent pas à tout embrasser. Par contraste, la théorie de l’esthétique de la réception, qui prend en compte ces deux points de vue, fournit un cadre théorique plus pertinent. L’article présente tout d’abord une analyse théorique de la réciprocité entre, d’une part, la subjectivité du traducteur et, d’autre part, les contraintes correspondantes. Il fait ensuite état d’une étude de cas sur la transédition de nouvelles de l’anglais en chinois dans la presse taïwanaise, afin d’illustrer comment appliquer concrètement cette théorie à l’examen et à l’évaluation de la subjectivité du traducteur et des contraintes auxquelles elle est soumise.

Mots-clés :

- esthétique de la réception,

- transédition de nouvelles,

- subjectivité du traducteur,

- contraintes

Corps de l’article

1. Introduction

In the press, news transediting is a special type of translation combining both the translating and editing processes (Stetting 1989), and it serves as a gateway to interlingual and intercultural news communication.[1] Using various strategies, including selection, deletion, addition, combination, synthesis, abridgment and recomposition, news transediting reshapes the source news to cater to the needs and interests of the target readers and to comply with the target news organization’s socio-political stances (Vuorinen 1997; Li 2001; Cheng 2002; Orengo 2005). These news transediting characteristics reveal an inherent contradiction. On the one hand, the transedited news texts should be factually consistent with their sources to conform to journalistic ethics. On the other hand, to communicate as effectively as possible, the source news texts must be adjusted to accommodate the target culture (Ma 2006).

As an active gate-keeper who allows some source information to pass through the channels of communication while keeping other information out (Fujii 1988; Vuorinen 1997; Hursti 2001), the news translator plays a pivotal role in reconciling this contradiction while maintaining a proper balance between accuracy and acceptability. Nevertheless, his/her subjectivity is not completely free from constraints but is, in some measure, governed and controlled. Only when the translator optimally exerts and appropriately constrains his/her subjectivity, can suitable, desirable and accurate target news texts be produced to enhance effective cross-cultural communication.

It should be noted that news translators here may refer either to (1) journalists transediting news texts or to (2) translators who work with journalists and generally have the title of transeditor.[2] The former usually possess relevant journalistic knowledge as well as substantial work experience in the media but do not receive any translation training. They rarely regard themselves as translators, who, in their view, seem to play a more passive and low-ranking role. The latter, on the contrary, are not usually trained journalists but do have a background in translation or other academic disciplines. No doubt they gradually develop effective journalistic skills and a better news sense through the process of being transeditors (see Chen 2008: 36; Bielsa and Bassnett 2009: 81-83). Both types of news translators carry out similar tasks of translating, editing and rewriting.

Despite its significance, the news translator’s subjectivity has been largely neglected and under-studied in existing research on news transediting in the press, which primarily focuses on transediting strategies, gate-keeping functions and relevant contextual factors.[3] Adopting reception aesthetics as a general analytical framework, therefore, this paper intends to explore theoretically the appropriate reciprocity between the news translator’s subjectivity and the corresponding constraints in the transediting of hard news texts.[4] Unlike soft news, which revolves around human-interest stories, hard news generally refers to those news stories that are timely, factual, important and serious on issues such as politics, economics, business and major crime (Fedler, Bender et al. 2001: 121). An empirical study on English-Chinese news transediting in the Taiwanese press is here conducted to demonstrate how to apply the theoretical analysis to actual transediting practice.

2. Previous accounts of the translator’s subjectivity

The translator’s subjectivity, defined as the subjectivity that the translator displays during the translation process, includes such features as the translator’s cultural consciousness, reader awareness, personal traits, social and ideological positions, linguistic competence, aesthetic tendency and creativity, all of which may manifest themselves through textual appropriation, adaptation and intervention. This section will review and assess previous work on the translator’s subjectivity in translation studies.

Early translation practices began with the translating of religious and literary works. In these translations, the translator’s faithfulness to the source text or to the author was of primary importance. The translator was compared to a servant inferior to the author of the original work (Bassnett 1993: 147), and translation was regarded as imitative work. During the 1950s and 1960s, as linguistics became a prominent discipline, the notion of equivalence dominated translation studies, giving rise to some linguistic approaches to translation, such as the theories proposed by Nida (1964) and Catford (1965). These linguistic approaches emphasized the equivalence between expressions in the source and target languages. In this context, the translator’s work was not viewed as creative but rather as mechanical. The criteria of both faithfulness and equivalence give top priority to the source text while overlooking the translator’s subjectivity.

The cultural turn in translation studies after the 1970s brought about a range of new perspectives that promoted a rise in the translator’s status and subjectivity to varying degrees. Translation scholars applying the polysystem theory and the norms approach, together with those of the manipulation school, paid particular attention to historical contexts and the cultural implications of translation. They maintained that a translation was greatly affected and constrained by its target culture, including its socio-political factors, power structures, ideologies and poetics (see Even-Zohar 1978; Toury 1978; Hermans 1985; Bassnett and Lefevere 1990; Lefevere 1992). Rather than passively transferring source meanings, the translator takes the initiative in considering and evaluating these various influences. Scholars examining translation from deconstructionist, feminist and postcolonial perspectives argued that the source text had no fixed meaning and that the translator should actively control and intervene in the source text (see Godard 1990; Niranjana 1992; Venuti 1995; Simon 1996; Robinson 1997; Davis 2001). The translator acts as a manipulator, carrying out political and cultural intervention through rewriting and recreation. As an active constructor, the translator enjoys the freedom to attach meanings to the target text.

The approaches coming out of this cultural turn acknowledge the translator’s subjectivity but fail to provide a comprehensive account of it. They either focus exclusively on constraining factors or merely emphasize unrestrained subjectivity. In contrast, the theory of reception aesthetics, aiming to understand both subjectivity and its constraints, can serve as a more thorough theoretical framework to explore the optimal realization of the news translator’s subjectivity. Section 3 will first give a brief review of the main notions of reception aesthetics, followed by the justification for applying this theory to hard news transediting in Section 4.

3. Main notions of reception aesthetics

Drawing on hermeneutics and phenomenology, the Constance School in Germany developed reception aesthetics in the 1960s. Reception aesthetics scholarship is represented by the work of Hans Robert Jauss and Wolfgang Iser. As a consequence of this theory, literary studies shifted focus from the author or text to the reader, who is viewed as an inseparable factor in the aesthetic significance of literary works and a decisive part in actualizing the meaning of the text.

3.1. Jauss’s reception theory

Jauss (1982: 19) argues that the “historical life of a literary work is unthinkable without the active participation of the addressees” because the reader’s reception decides the aesthetic value of a work. He proposes two central notions concerning the reader’s reception: horizon of expectations and aesthetic distance. As indicated by Holub (1984: 59), the horizon of expectations refers to “a structure of expectations or… a mind-set that a hypothetical individual might bring to any text” (i.e., the pre-understanding that a reader possesses before beginning to read). Based solely on this horizon, the reader can carry on an aesthetic dialogue with the literary text to comprehend and achieve a fusion of horizons. The reader’s horizon, which changes over time, determines the way a literary text is appreciated as well as the reader’s focuses and attitudes while reading. The resulting textual interpretation is inevitably subjective and selective.

Two subcategories of the horizon can be further identified: narrow literary expectations and broader life expectations. The former is derived from the reader’s previous aesthetic experiences regarding literary structures, styles and genres, whereas the latter is formed by the reader’s socio-cultural assumptions and individual lived experiences (Rush 1997: 79-81). It is obvious that the reader’s horizon of expectations is, to a great extent, influenced and structured by his/her surrounding environment and context.

Aesthetic distance is defined by Jauss (1982: 25) as the “disparity between the given horizon of expectations and the appearance of a new work.” If the distance is too large, the work may appear too overwhelming. The difficulty, then, is much more likely to emerge as the reader finds it hard to fuse his/her horizon with the work. Consequently, he/she might find it unattainable and express distaste for it. If the distance is too small, boredom sets in, and the reader may lose interest even though the fusion of horizons is easy to achieve. In order for a literary work to be successfully received by the reader, it should adequately surpass his/her horizon and enrich the reader’s knowledge and life experiences (see Hu and Zhang 1988: 281).

3.2. Iser’s theory of aesthetic response

Iser’s theory places high priority on the reader’s significant role in the construction of meaning. He contends that a literary work does not exist with a determined meaning, but rather it provides only a schematic structure. Aside from several textual perspectives, the structure also contains numerous gaps and blanks that can be filled and actualized only by the reader through the reading process. As an active and creative recipient, the reader (prompted or compelled by the indeterminacy and vacancy of the text) will give substance to the textual omissions, make the uncertainty definite and eventually realize the meaning and aesthetic value of the literary work (Iser 1978: 21-24, 182-187). This blank/gap-filling process is referred to as concretization and is based on the reader’s personal experiences and preconceptions (i.e., horizon of expectations). It is thus subjective and imaginative. No two concretizations of the same text are precisely identical, even if they are from the same reader (Iser 1978: 171-174).

To further explain the effective text-reader interaction, Iser puts forward the notion of the implied reader, a hypothetical figure the author addresses in his/her literary work. Such a notion consists of “both the pre-structuring of the potential meaning by the text and the reader’s actualization of the potential through the reading process” to integrate the reader’s presence and participation (Iser 1974: xii). To achieve successful literary communication, the author needs to incorporate the reader into the text by pre-arranging various textual perspectives that can enable the reader to both interpret the text adequately and appreciate its aesthetic value. These different perspectives (e.g., those of the narrator, characters and plot) are not explicitly connected to one another, and each of them is usually presented as a fragment. Then, after being encouraged to exercise his/her imagination and creativity by the blanks/gaps within and between the differing perspectives, the reader should take the initiative in concretizing what is unexpressed to cohere all textual viewpoints. This concretization is not without limits, but is controlled by the textual perspectives and circumscribed by the meaning potential of the literary text (Iser 1978: 35-38; 1993: 33-34).

4. The justification for applying reception aesthetics

The reason why reception aesthetics can provide a more thoroughgoing analytical framework here is twofold. Firstly, this theory is more comprehensive than varied approaches under the paradigm of the cultural turn because it can explain the operation of the news translator’s subjectivity as well as account for its constraints stemming from the three immediate factors (i.e., the source news, the demands of the target news organization and the target audience) at both the comprehension and production stages. Secondly, it highlights some important but neglected aspects of the news translator’s constrained subjectivity and provides guidelines for analyzing them.

The news translator as an active reader would inevitably exhibit his/her subjectivity when reading and interpreting the source news, which in turn may considerably influence how the translator produces the target news. Such a phenomenon during the comprehension stage, however, has not been widely explored in the field of news transediting. In accordance with reception aesthetics, the exercise of the translator’s subjectivity at this stage can be illustrated in terms of his/her individual horizon of expectations. Furthermore, the corresponding constraints can also be identified, that is, those from the source news, which contains definite facts, and from the translator’s working environment, that is, the target news organization.

Extant studies on news transediting (whose focuses have been mentioned in Section 1) do not directly address the translator’s subjectivity at the production stage. Yet it can be concluded from them that the translator’s subjective agency is in some way reflected in using transediting strategies to fulfill his/her role as gate-keeper and successfully convey the relevant and newsworthy information. The theory of reception aesthetics sheds further light on one aspect largely ignored in those studies, namely, the news translator’s prearrangement of the target perspectives, which may contribute to the more efficient communication of the selected newsworthy information. Existing research also widely examines the constraints regulating the production of transedited news. The constraining forces thus identified include those related to the demands of the target news organization (e.g., journalistic conventions, writing styles, length and space limitations and the target news organization’s editorial policies and stances) as well as those of the target readers’ interests and needs. Reception aesthetics further brings to the fore the readers’ horizons of expectations, as the target recipients do not simply passively absorb whatever is presented in the transedited news. The importance of taking the readers’ horizons into account has also been acknowledged by some journalism scholars applying reception aesthetics to news production (Tsang and Tsai 2001; Xie 2002; He 2003; Wu 2006). These scholars indicate that the active and positive acceptance by the audience is a yardstick against which the effects of news communication can be measured; thereupon, it is essential for news writers to keep the intended readers in mind at all times during the production stage, meticulously considering their horizons.

5. The news translator’s subjectivity and its constraints

Having justified the feasibility of applying reception aesthetics to the process of transediting, this section will provide a detailed theoretical account of the appropriate interdependence between the translator’s subjectivity and its constraints in hard news transediting at the comprehension and production stages. In actual practice, the comprehension and production stages do not necessarily progress in strict order and may overlap or interweave with each other. Nevertheless, for the sake of clarity, they will be treated as separate phases.

5.1. The comprehension stage

Taking on the role of the primary and special reader of the source news, the news translator enters the reading process with a given horizon of expectations, which consists of (1) broader expectations formed by his/her socio-cultural and historical background, beliefs, values, political affiliation, language competence and personality, and (2) narrow expectations toward the news genre constituted by his/her knowledge of news media, journalistic conventions and generic structures as well as by his/her news reading habits and experiences (Wu 2006: 147). This horizon guides the translator’s selection of news information, reading focus and evaluation of the source news. Because the translator is situated in the setting of the target news organization, his/her horizon formation is inevitably influenced and governed by the news organization’s social, political and cultural viewpoints and specific editorial policies. This impact is especially evident in the translator’s internalization of those perspectives.

To achieve the best fusion with the source text, the news translator must spend more effort than the original intended readers, as the source news does not keep his/her horizon in mind and may often maintain a considerable distance. The translator is not always able to completely fuse his/her horizon with the original work due to differing historical and social backgrounds, cultural contexts and other subjective factors. What can be achieved is a maximum fusion, through which the translator revises, updates, alternates or reconfirms previous assumptions and obtains a sufficient understanding of the source news.

The news translator’s subjectivity also manifests itself in the active concretization of the gaps and blanks embedded within the source perspectives, which include the source newspaper’s own reporting angles as mainly expressed in the headline and the lead (i.e., the opening sentence or paragraph in a news text) as well as external viewpoints cited therein. Although performed on the basis of the translator’s own horizon, concretization is not done at will. The target news organization’s stances, especially those internalized in the translator’s horizon, will to some extent structure the ways the translator creates concrete textual meaning. This constraining force, however, should not be too overwhelming and undermine the definite facts covered in the source news. The translator may adopt the target news organization’s stances rather than follow the guidance of various source perspectives (which are primarily arranged for the source readers), but his/her interpretation should not deviate far from what is communicated in the source news.

5.2. The production stage

Using as a foundation the fusion of horizons and concretization achieved in the comprehension stage, the news translator embarks on the actual job of news transediting. At this stage, the translator, who performs multiple roles (i.e., as translator, editor and writer), fulfills his/her gate-keeping functions to achieve the following two goals: to produce the target news capable of attracting the target readers’ attention and to forge an effective text-reader relationship. News texts usually do not address actual readers, but rather an assumed audience that shares the news organization’s values and beliefs. The actual reader may or may not be the intended addressee of a given news text but is directed and expected to take that role and to respond accordingly (see Reah 2002: 35-51). The intended reader then resembles Iser’s implied reader. To prompt active reader involvement, the translator needs to identify and address the readership in the target news either explicitly or implicitly. Hence, his/her subjectivity during the production stage is prominently revealed in the pre-structuring of the target perspectives and the gaps/blanks that can guide and stimulate the intended target readers. This pre-structuring is achieved through the translator’s adoption of various transediting strategies that adjust the source messages obtained at the comprehension stage. Those messages deemed unimportant will be cut out, and the remaining parts will be assembled, reorganized or rewritten into a news report in another language.

According to reception aesthetics, the pre-structured perspectives of a literary work lead readers to progressively explore and realize the potential meaning of the work, whereas the blank spots are used to evoke the reader’s imagination and creativity. Unlike literary works, transedited hard news attempts to offer the most updated and important information within a limited space. What matters is clear and precise information rather than creative imagination. The pre-set perspectives, especially the target reporting angles (which are usually exhibited in the headline and lead), are organized (1) to highlight the news values that can draw in the intended readers, and (2) to straightforwardly and immediately orient the target readers with the aim of establishing successful text-reader interactions. Likewise, instead of provoking multiple imaginations, the gaps/blanks are primarily arranged to invoke the target readers’ corresponding memories in an attempt to join their individual experiences to the various textual perspectives and to further strengthen the existing news values as well as reconfirm initial reading orientations.

The target readers, as the news translator’s main concern when he/she exerts subjectivity, would surely introduce a constraining force. Specifically, the translator needs to consider not only the readers’ interests but also their horizons of expectations, especially their socio-cultural values, political attitudes and language competence together with their reading habits and experiences, as opposed to those of the source readers. With the readers’ horizons in mind, the translator can be directed to structure the target perspectives appropriately and produce the target news with a proper aesthetic distance that enriches the readers’ horizons and satisfies their interests. On the other hand, he/she can design a range of gaps and blanks (either through rhetorical devices or through the lack of precise connections between different perspectives) to elicit the most relevant memories from the target readers.

The news translator is also subject to the editorial policies and stances held by the target news organization, which usually hopes to convey its viewpoints and attitudes to the readers with some effect. Normally, rather than a single translator, a transediting team that may include the news translator, the director of the foreign news section, editors and other senior staff carries out the task of news transediting. During the transediting process, such an editorial line is of paramount importance, as it clearly and overtly monitors the operation of the translator’s subjectivity. The director and editors, who generally support the target news organization’s stances and policies, usually inform the translator of the favored news angles and oversee or modify the transedited texts when necessary to make sure that the designed target perspectives, which are arranged to match the readers’ preferences and interests, are consistent with the newspaper’s viewpoints (Ji-Hae 2007: 224-226; Chen 2008: 36). Alternatively, the target news organization may specify in its stylebook what the translator can or cannot include in the target news.

The ethics of journalism and the conventions of news writing style in the target culture give rise to the third main constraint. News transediting is embedded in the system of news production in general, and the ethics of news reporting (including accuracy, truthfulness, objectivity and fairness) govern the news translator as a media practitioner when arranging varying target perspectives. Therefore, the readers and the target news organization should not influence the translator to the detriment of the facts reported in the source news. Moreover, the translator working for a news organization needs to observe its news writing practices, which are stated in the stylebook and may encompass common requirements of journalistic style and special conventions of transedited news in the target culture. The common requirements refer to such things as clarity, conciseness and correctness, whereas the special conventions may govern culture-specific language styles, source attribution patterns, space limitations and the generic structure of transedited news, which regulates how the translator organizes the overall semantic meaning and arranges the main focus along with other corresponding but less essential information.

6. Introduction to the case study

Having provided a theoretical account on the translator’s constrained subjectivity, this paper presents a case study to elucidate how this account can also be applied (1) to explain the reciprocity between the translator’s subjectivity and its constraints as embedded in actual transedited news items, and (2) to evaluate how well the subjective agency and the governing constraints can be balanced in real-world transediting practice. Section 6.1 first explains the methodology to be followed, and the case study data is introduced in Section 6.2.

6.1. Methodology

Although the operation of the translator’s subjectivity and related constraints is not directly observable, it usually results in the adjustment and reshaping of the source news that consequently lead to a number of changes in the transedited texts. In view of this, the overall shifts appearing in the target news can be considered the external manifestation or evidence of such an operation. Using some actual transedited news texts and their source counterparts as its data (see Section 6.2), the case study will follow the two-step procedure to explore the translator’s constrained subjectivity:

Step one: examining the overall shifts in the target news to obtain relevant textual evidence

Step two: applying the theoretical account to interpret and assess the translator’s constrained subjectivity based on the shifts identified at Step one

Here Step one deserves to be elaborated to clarify how to investigate overall transediting shifts. As indicated in previous studies on English-Chinese news transediting (Chen 2008; 2009),[5] when English hard news is transedited into Chinese, the source and target news resemble each other in the generic structure (the global form) but differ greatly in the accompanying semantic macrostructure (the global meaning), whose organization is determined by the generic structure, as mentioned in Section 5.2. According to White’s (1997; 1998) orbital structure approach, the generic structure of hard news is typically composed of a nucleus and a set of satellites. The analysis at Step one, therefore, will focus predominantly on the semantic shifts that can be identified by comparing the global meanings of the source and target news texts when presented in the orbital structure. That is to say, by examining the content changes occurring to the target nuclei and satellites, a clear picture of the overall semantic shifts can emerge. In what follows, the specific features and mutual relationship of the nucleus and satellites are explained further.

Based on systemic functional grammar (Halliday 1994), White proposes an orbital structure (nucleus-satellite) for the hard news item. The nucleus, the opening phase of the hard news story, consists of a headline and a lead that are essentially interlinked and can be viewed as a single unit, as the headline usually serves as a concise paraphrase of the lead. Acting as the anchor point, the opening nucleus encapsulates the core information of the news story, pinpoints the most newsworthy aspects and sets out the reporting angle (Iedema, Feez et al. 1994: 110-115; White 1997: 111-112).

All the textual components following the headline/lead nucleus make up the second phase and act as dependent satellites circulating around the central nucleus. They are arranged orbitally rather than linearly and chronologically. To be specific, these satellite components are not sequentially connected to each other to accumulate meanings, but all reach back to the nucleus and expand it through such specifications as elaboration, contextualization, explanation, appraisal and justification. The fundamental function of the second phase is not to introduce completely new information but to extend or enhance the meanings already presented in the headline/lead nucleus (White 1997: 115; 1998: 194).

The nucleus-dominated and orbitally-organized structure of the hard news story is also manifested in its thematic structure, in which the headline/lead nucleus functions as the hyper-theme. The theme, according to Halliday (1994: 37), “is the element which serves as the point of departure of the message; it is that with which the clause is concerned.” Like this clause theme, the hyper-theme (i.e., the textual theme) sets out the subject matter or an orientation of what is to come but at a more global textual level than a clause. In addition, the hyper-theme “is predictive; it establishes expectation about how the text will unfold” (Martin and Rose 2003: 194). Presenting the central concerns of the whole news text, the nucleus, in the manner of the hyper-theme, normally tends to foretell and single out the theme choices in the subsequent satellites, with the information introduced by the satellites all relating back to itself (White 1998: 200-201).

It is worth mentioning that apart from White’s orbital structure, there also exist other commonly cited approaches to the generic structure of hard news, such as the inverted pyramid form proposed in journalism training literature (e.g., Evans 1972; Rich 2000), Van Dijk’s (1988) cognitive perspective and Bell’s (1991) narrative structure. The reason why this paper adopts White’s analysis is that the nucleus-satellite structure not only highlights the significant role of the headline/lead as the focal point but also specifies the relationship between the headline/lead and the remaining components. This relationship can in turn make plain the internal arrangement of the target semantic macrostructure as compared with that of the source and can greatly help to clarify how the various source perspectives are recomposed in the target news. In contrast, the other three approaches all account for the structure of the hard news item by reference to the notion of importance, though they hold different ideas about the constitutive elements of news. The principle of importance merely points out that the most substantial information is placed at the start (the headline/lead part), whereas the other points follow in order of diminishing importance, without elucidating their mutual connection.

6.2. Case study data

The main types of news transediting practised in Taiwan include: (1) transediting without traces of sources and (2) transediting of news texts from wire services (such as Reuters, AFP, UPI and AP), foreign news organizations (both news channels and newspapers) or a combination of both (Chen 2008: 38). As the comparison of the source and transedited news is a fundamental part of the case study, this paper concentrates on transediting of news items solely from foreign newspapers. Without the specification of sources, the translator’s subjectivity involved in the first type of news transediting cannot be examined. Due to the continuous updating of news by wire services, it is difficult to identify which source versions were adopted for the transedited pieces. Tracing the source texts from foreign newspapers, nonetheless, is comparatively easy because they are final products, and their publication dates and the names of the source newspapers are both clearly indicated in the transedited news.

The case study data in this paper thus covers 10 hard news texts in English from the online versions of the New York Times and the Washington Post and 10 Chinese transedited news texts from the online versions of the China Times and the Commercial Times, two newspapers under Taiwan’s China Times Group, in which news transediting is commonly undertaken by a transediting team, and the news translator therein is usually not a well-trained journalist working from English but rather a transeditor cooperating with journalists (Chen 2008: 36). The collected data are illustrated in table 1, using the headlines of the source and target news.[6]

Table 1

Case study data

As illustrated in table 1, the news events of the data collected revolve around three main topics: (1) Chinese president Hu Jintao’s four-day visit to the U.S. in 2006, (2) China’s exports of tainted products (including pet food and toothpaste) in 2007, and (3) China’s internet censorship and video surveillance in 2008. All these news events involve U.S. opinions on China, and foreign news concerning these opinions is often transedited by the Taiwanese press, given the significant role of the U.S. in conflicts between China and Taiwan. Because the U.S. and Taiwan have different political relations with China, however, noticeable differences arise in their respective newspapers with regard to the political stances toward China. These dissimilarities in turn influence the way the news translators in Taiwan transedit foreign news from U.S. newspapers. At the time of the source news reports, the U.S. considered China an ally, though not a truly strategic partner due to differences in values and common goals.

The news coverage at this time concerning China by the New York Times and the Washington Post generally reflected this policy. The China Times and the Commercial Times have kept historically cordial relations with the Kuomintang (i.e., the pro-reunification Nationalist Party), which is the founding party of the Republic of China on Taiwan. They tend to favor the concept of “one China” but sometimes lean toward maintaining Taiwan’s status quo. These two target newspapers, nevertheless, interpret “one China” from a cultural perspective rather than from a political viewpoint, as China does, and they also disapprove of the government of the People’s Republic of China (Wei 2000; Hsiao 2006). On account of this, when producing the target news texts listed in table 1, the China Times and the Commercial Times did not view China as an ally but as an “imperfect friend” (i.e., the “Other”) at best. In virtue of the differing attitudes of the target and source newspapers, it is to be expected that the translator would adapt or customize the source news texts to some degree and that the interaction and negotiation between the translator’s subjectivity and its corresponding constraints are likely to be more prominent.

7. Data analysis

Following the methodology set out above, this section will investigate the semantic shifts occurring in both the target nuclei and satellites of the hard news stories. With the shifts as evidence, the translator’s conditioned subjectivity at both the comprehension and production stages will be systematically inferred and evaluated under the guidance of the theoretical account proposed in Section 5.

7.1. The subjectivity and constraints manifested in the target nuclei

The source and target nuclei are both summarized in English in table 2. Compared with the source nuclei, nearly all of the target nuclei have different foci or extra messages that are in one way or another concerned with unfavorable aspects of China (see the italicized parts in table 2).

Table 2

Comparison of the source and target nuclei

Although it may not be possible to determine if the shifts resulted from the translator’s comprehension activity, production activity or a combination of both processes, those shifts identified in the target nuclei still help us to infer how the translator’s subjectivity and its constraints exercised their influence during both stages.

The shift of focus in the target nuclei may first suggest that the news translator, situated in the journalistic cultures of the China Times and the Commercial Times, comprehended the source texts with his/her horizon of expectations, which in turn led to the changes in emphasis during the course of reading. As mentioned earlier, the two target newspapers regarded China as an “imperfect friend” (i.e., the “Other”), and this attitude may have been internalized by the translator. When he/she exercised subjectivity through the fusion of horizons and concretization, the information critical of China may have evoked and reconfirmed the translator’s past experience and thus become more prominent in his/her interpretation of the source news.

The shifts occurring in the target nuclei were mainly caused by the operation of various transediting strategies adopted by the translator (including retopicalization, combination, synthesis and abridgement) that restructured the source nuclei and satellites in the target texts. Therefore, these shifts may also reveal the translator’s subjectivity in the arrangement of the target newspapers’ own reporting angles in the nuclei. Such an arrangement seemed to be chiefly regularized by the principle of negative Other-presentation, concomitant with the target newspapers’ stance toward China. This principle enables an in-group to express that an out-group is inferior through the following two discursive moves: emphasizing negative information and suppressing positive information about the “Other” (Van Dijk 1998: 33). The newspaper exerted its governance in two ways. First, the translator, on his/her own initiative, followed the strategy of negative Other-presentation to reset the target nuclei. Second, other transediting members (such as the director or the editors) may have changed the texts if the target nuclei designed by the translator appeared inconsistent with the stance held by the target newspapers.

Moreover, the arrangement may reflect the translator’s consideration of the readers’ horizons and interests. The translator may have assumed that the target readers of the China Times and the Commercial Times shared the newspaper’s political values and beliefs (Hsiao 2006). In doing so, he/she presupposed that the negative and destructive messages about China, which fulfilled the news values of consonance, proximity and negativity (see Van Dijk 1988: 121-124), could grasp their attention.[7]

Although mostly distinct from their source counterparts, the target nuclei generally do not go beyond the overall facts conveyed in the source news, and the ethics of reporting are largely observed. However, it is worth noting that the term 中共 (the CCP [the Chinese Communist Party]) adopted in the target nuclei is not concordant with its source counterpart (i.e., China or Chinese) and seems to change the original meaning. The target nuclei in news items (1), (5) and (9) all contain this term, as demonstrated by the underlined parts in table 2. The Chinese headlines from news items (5) and (9) serve as illustrating examples (see table 1).

The term the CCP may not have been adopted in the source texts because it might be a breach of etiquette to refer to foreign governments by the name of the ruling party. As pointed out in the New York Times Manual of Style and Usage, “the name of the country is simply China. Communist China is acceptable to make a special point – a contrast, for example – or in a quotation” (Siegal and Connolly 1999: 77, emphasis in the original). The shifts occurring to the source terms China and Chinese seem to be commonly seen in the transedited news published by the China Time Group. Similar shifts are also identified in Chen (2009), which investigates the ideology-related norms governing the transedited news items on Taiwan-China political conflicts published from 1999 to 2004 by the China Times and the Commercial Times. Chen further suggests that the longstanding power struggle between the Kuomintang and the CCP, that is the Chinese civil war from 1927 to 1949, may be the main reason contributing to such shifts. With respect to this, it is likely that, consciously or subconsciously, the news translator or other transediting members of the target newspapers (which are affiliated with the Kuomintang) adopted the term 中共 (the CCP) to express disapproval of the Mainland China government.

The semantic shifts in the target nuclei, along with the space limitations imposed by the target newspapers, result in the different semantic composition of the satellites in the target texts. After comparing the source and target news, the source components recurrently selected to be the target satellites and those regularly deleted are illustrated respectively in Sections 7.2 and 7.3, in which the translator’s constrained subjectivity will be accounted for, using those repeatedly chosen and deleted components as evidence.

7.2. The subjectivity and constraints manifested in the target satellites

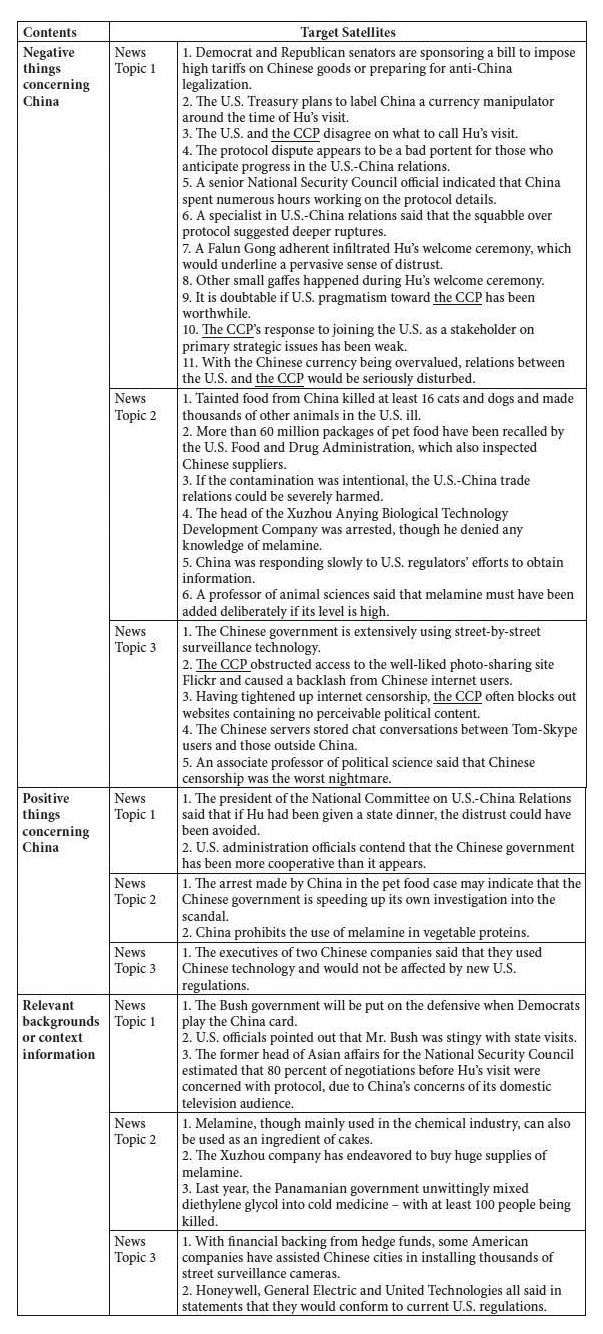

The main source messages regularly selected and rendered into the target satellites are generally classified into three types, as illustrated and summarized in English in table 3:

Table 3

Target satellites

The above target satellites all provide further detailed information about the focal points conveyed in the target nuclei. The satellites related to “negative things concerning China,” which account for a large portion of the target satellites, are most directly connected to and consonant with the target nuclei. Such dominance once again reflects the prominence of unfavorable information about China in the translator’s comprehension through his/her constrained horizon of expectations, as discussed in Section 7.1.

This dominance may also reveal the translator’s subjectivity in setting up other perspectives and planning gaps or blanks. Employing the strategies of selection, synthesis, abridgement and recomposition, a range of external sources was organized to present viewpoints detrimental to China. Thus, the reading orientations set in the target nuclei were reconfirmed and further strengthened. Taken together, all of these pre-structured perspectives (both in the nuclei and satellites) could lead the target readers to arrive at the intended meaning of the target news by awakening or refreshing their memories of China as an “imperfect friend” and then guiding them to fill in gaps or blanks accordingly. The possible constraining forces at this phase are similar to those governing the translator’s arrangement of the reporting angles in the target nuclei, so they are not restated here.

Regarding the positive satellites about China and the relevant backgrounds or context information, they may suggest the translator’s active fusion with the source news that in turn expanded and changed his/her horizon with something new and incongruent. However, they may also imply the translator’s concern about the target readers’ horizons and his/her compliance with the ethics of reporting. The translator chose some information conceived as novel and dissimilar to the readers’ horizons to enrich their experiences, to prevent their interests from diminishing and to meet the very purpose of reading a newspaper (i.e., to gain new and current information). Besides, deleting all information that is favorable to China may have resulted in biased and partial news reports that would deviate too far from the journalistic ethics of accuracy and objectivity.

Aside from the regularities in the semantic content, three other recurrent features are identified. First, about 20% of the target satellites use the term 中共 (the CCP) to refer to China (as illustrated by the underlined parts in table 3) even though this term does not appear in the corresponding source news. Similar examples have already been provided in Section 7.1.

Secondly, the names of the source newspapers or the source texts are frequently referred to as news sources in most of the target satellites. Such additions indicate that the viewpoints reported in the transedited news originated from either the Washington Post or the New York Times, as in examples (1) and (2) in Table 4:

Table 4

Identifying the news sources

Third, one target satellite is usually composed of messages from two or more source satellites through the strategies of combining, synthesizing and abridging, as shown in examples (1) and (2) in Table 5:

Table 5

Combining, synthesizing and abridging

Each of the target satellites listed above is composed of two source satellites. The source satellites are not translated word for word into Chinese but are synthesized and abridged into one target satellite with irrelevant information deleted, such as the source information of “[b]ut melamine is not approved for use in animal or human foods and therefore any use of it would be illegal” in example (1) in Table 5.

The three aforementioned features all indicate the forces restricting the translator’s subjectivity when producing the target texts. The term 中共 (the CCP) used in the target text suggests the prevailing constraint stemming from the target newspapers’ negative presentation of China as an out-group (addressed in Section 7.1).

Using newly added news sources reveals the binding forces from the special conventions of news transediting in the target culture. The original newspapers or original texts are routinely referred to as cited sources in the transedited hard news in the Taiwanese press, as pointed out by Chen (2008: 38). The newly added sources also indicate the influence of the target readers’ interests and expectations on the translator’s text design. Due to U.S. involvement in mediating Taiwan’s relationship with China, the translator may have assumed that the intended readers of the target news would show concern over the U.S. stance toward China or China-U.S. relations and expect to be informed of such information provided by credible and reliable sources. In this case, citing the New York Times and the Washington Post (two prestigious and authoritative U.S. newspapers) as the original sources of the target texts could embody the news value of reference to elite groups and consequently raise the target reader’s attention.

The tendency to synthesize and abridge two or more source satellites into one target satellite may first signify the demands of the target news writing style. In English journalistic writing, a satellite often contains only one piece of information in order to convey a clearer meaning. Conversely, Chinese newspapers are not subject to such a limitation, and one satellite often comprises several pieces of information (Kuo and Nakamura 2005: 407). In addition, this tendency makes the space restriction on the transedited texts clear. A transedited text is generally shorter than its original text. The strategies of synthesis and abridgement thus enable the news translator to bring together related messages and reshuffle them in a more concise way to meet the space requirements.

7.3. The subjectivity and constraints manifested in the deleted portions

The source information that was repeatedly deleted in the target news is outlined in English in Table 6. The deleted portions can be broadly categorized into two types: (1) positive things concerning China and (2) detailed or irrelevant information.

Table 6

Deleted portions

Those parts affirming aspects of China appear to be contradictory (1) to the translator’s previous experiences or knowledge about China, (2) to the target newspapers’ impression of China as the “Other,” and (3) to the target readers’ assumed unfavorable attitudes toward China. On this ground, they may fail to fulfill the news values of consonance, proximity and negativity. This failure in turn may explain why only half of the positive statements about China were kept in the target texts (see Table 3), and the other half were deleted.

The translator’s constrained subjectivity, as revealed by these deletions, is much the same as that manifested in the target satellites offering negative information on China, so they are not elucidated again. Nevertheless, it should be mentioned that the deleted portion – Hu’s foreign policy address at Yale offering an upbeat vision on China-U.S. relations – is directly associated with the source nucleus of news item (4), as shown in Table 2. By completely omitting this portion, which was conceived as the central message in the source news, the corresponding transedited text may seem somewhat partial.

The removal of details or irrelevant information exhibits the translator’s awareness of the readers. These deleted parts, all pertaining to the events solely about China and the U.S. or concerned with very detailed messages, may have been regarded as superfluous and cumbersome in the transedited news. The omissions listed in table 4 also indicate the space restriction. Compared to the target satellites, the deleted parts, which are far less pertinent to the target readers’ expectations and needs, may have weakened their reading interests. With such editing, the primary meanings of the target texts can be brought into clearer focus.

8. Conclusion

Being socially, politically and culturally regulated, news transediting needs to fulfill multi-faceted requirements from the source news, the target audience and the demands of the target news organization. Thus, transediting relies to a great degree on the news translator – a crucial gate-keeper in the transediting process – to appropriately exercise his/her subjectivity and to adequately respond to diverse constraints. Only in this way can cross-lingual and cross-cultural news communication be enhanced by satisfactory and truthful transedited news.

Even so, the question of how the translator can properly balance his/her subjectivity and the relevant constraints has received surprisingly little attention. To address this oversight, this paper has proposed a theoretical account of the ideal reciprocity between the translator’s subjectivity and its constraints at both the comprehension and production stages of hard news transediting. To do this, this paper has drawn on the insights provided by the theory of reception aesthetics (such as the notions of horizon of expectations, aesthetic distance, concretization and the implied reader). Although reception aesthetics is a theory related to literary criticism, it offers workable guidelines to sufficiently and suitably define the translator’s constrained subjectivity, as illuminated in Sections 4 and 5.

This paper has also conducted a case study on English-Chinese news transediting to illustrate that the proposed theoretical account also carries a practical value, as it is applicable to real-world news transediting practice. More precisely, using as relevant evidence the overall semantic shifts that appear in the generic structure of the transedited news items, the interaction between the translator’s subjectivity and its governing constraints in actual practice can be systematically interpreted and assessed by adopting the theoretical account of reception aesthetic, as a guiding principle and as a criterion for evaluation.

Furthermore, it is clear from the case study analysis that striking a proper balance between the subjectivity and its constraints is not an easy task for the news translator, especially when the source and target newspapers hold distinct political attitudes toward the news events at issue. This case study has revealed that the translator, under the supervision of other transediting members, may be obliged to comply with constraints from the target newspaper. It follows that the joint effort of the translator and other transediting members is needed to prevent the binding force of the target newspaper from becoming overwhelming and to ensure an optimal realization of the translator’s subjectivity.

It is hoped that this research can contribute to a better understanding of the efficient and satisfactory exertion of the translator’s subjectivity, and that more future research in this area can be facilitated, such as a study investigating the impact of other constraints (e.g., the general media environment, the wider social context and the marketing factors in the target culture) or that examining the translator’s subjectivity in transediting of other news genres (e.g., soft news, editorials and specialist columns). Additionally, more case studies could be carried out that explore other possible practical values of the theoretical account proposed in this paper. For example, an empirical case study could be performed to investigate the feasibility of adopting this theoretical analysis as a top-down training model for hard news transediting in the press.

Parties annexes

Remerciements

This research was funded by the National Science Council, Taiwan (NSC 97-2410-H-027-006). An earlier version of this paper was presented at 2009 NTUT International Conference on Applied Linguistics and Sociolinguistics: The Form and the Content, 6-7 November 2009, National Taipei University of Technology, Taiwan. I am grateful to the two anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments and suggestions.

Notes

-

[1]

Most existing studies on cross-linguistic news communication in the press do not adopt the term news transediting even though the translated news texts examined in those studies involve considerable editing work. Instead, they opt for such terms as news translation and press translation. In the Taiwanese press, from which the case study data presented in this paper was taken, there are two types of news translation: full translation and transediting. For the former, the translator generally follows the generic and semantic structures of the source news texts and does not make much adjustment; for the latter, the translator usually needs to drastically reshape the source news to meet the expectations of the target newspaper and its readers (Li 2009: 189).

-

[2]

According to Bielsa and Bassnett (2009: 81-82), in big news agencies (e.g., AFP and Reuters) it is journalists who translate news, as translation is seen as an integral part of news production; in IPS (Inter Press Service), however, translators are employed to work with journalists. The model adopted by major Taiwanese newspapers such as the China Times and the United Daily News is similar to that of IPS.

-

[3]

For information on various transediting strategies, please see Kirk (1999), Li (2001), Huang (2002), Liu (2004) and Cheng (2004); for the studies on gate-keeping functions, please refer to Fujii (1988), Vuorinen (1997) and Hursti (2001); for previous research on the contextual factors surrounding news transediting, please consult Sidiropoulou (2004), Bassnett (2005), Kuo and Nakamura (2005), Orengo (2005), Davies (2006), Chen (2007; 2008), Holland (2007), Ji-Hae (2007), Valdeón (2008) and Bielsa and Bassnett (2009). All the above studies are concerned with news transediting in the press. Tsai (2005; 2006; 2009) and Lee (2006), on the other hand, provide some insights on transediting in broadcast news media.

-

[4]

Hard news and soft news differ in topics, functions, structures, writing styles and uses of language. Thus, the translator’s subjectivity manifested in the transediting of these two types of news may be different. This paper focuses on the subjectivity expressed in hard news transediting, which can serve as a starting point for future research on the translator’s subjectivity in soft news transediting.

-

[5]

Ya-mei Chen (2009): 〈從引述的編譯探討新聞編譯之意識型態規範〉[Quotation as a Key to the Investigation of Ideology-related Norms in News Transediting], unpublished. The 13th Taiwan Symposium on Translation and Interpretation Training. Taipei, 10-12 January, 2009.

-

[6]

In tables 1 and 2, ST refers to the source texts, and TT refers to the target text. English back translations of the Chinese headlines listed in table 1 are provided in parentheses.

-

[7]

For more information on news values, please see Galtung and Ruge (1981), Van Dijk (1988: 119-124), Bell (1991: 155-160) and Allan (1999: 62-64).

Bibliographie

- Allan, Stuart (1999): News Culture. Buckingham: Open University Press.

- Bassnett, Susan (1993): Comparative Literature: A Critical Introduction. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Bassnett, Susan (2005): Bringing the News Back Home: Strategies of Acculturation and Foreignization. Language and Intercultural Communication. 5(2):120-130.

- Bassnett, Susan and Lefevere, André, eds. (1990): Translation, History and Culture. London: Pinter.

- Bell, Allan (1991): The Language of News Media. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Bielsa, Esperança and Bassnett, Susan (2009): Translation in Global News. London: Routledge.

- Catford, John C. (1965): A Linguistic Theory of Translation. An Essay in Applied Linguistics. London: Oxford University Press.

- Chen, Ya-mei (2007):〈再探新聞編譯的歸化現象—以神盾艦軍售新聞的中譯為例〉[Adaptation in News Transediting Revisited]. Translation Quarterly. 45:34-52.

- Chen, Ya-mei (2008): The Translator’s Constrained Mediation in Trans-editing of News Texts Narrating Political Conflicts. Cultus: The Journal of Intercultural Mediation and Communication. 1:34-55.

- Cheng, Maria (2002): 〈新聞編譯的原則與策略〉[Principles and Strategies of Transediting for the News Media]. Journal of Translation Studies. 7:113-134.

- Cheng, Maria (2004): 《傳媒翻譯》 (Translation for the Media). Hong Kong: City University of Hong Kong Press.

- Davies, Eirlys E. (2006): Shifting Readerships in Journalistic Translation. Perspectives: Studies in Translatology. 14:83-98.

- Davis, Kathleen (2001): Deconstruction and Translation. Manchester: St. Jerome Publishing.

- Evans, Harold (1972): Newsman’s English. Oxford: Heinemann.

- Even-Zohar, Itamar (1978): Papers in Historical Poetics. Tel Aviv: Porter Institute.

- Fedler, Fred, Bender, John R., Drager, Michael W., et al. (2001): Reporting for the Media. 7th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Fujii, Akio (1988): News Translation in Japan. Meta. 33(1):32-37.

- Galtung, Johan and Ruge, Mari (1981): Structuring and Selecting News. In: Stanley Cohen and Jock Youn, eds. The Manufacture of News. London: Constable, 52-63.

- Godard, Barbara (1990): Theorizing Feminist Discourse/Translation. In: Susan Bassnett and André Lefevere, eds. Translation, History and Culture. London: Pinter, 87-96.

- Halliday, Michael. A. K. (1994): An Introduction to Functional Grammar. 2nd ed. London: Edward Arnold.

- He, Guo-ping (2003):〈新聞傳播的接受之維—以接受美學為理論參照〉(On the Reception Dimension of News Communication: Theoretical Reference to the Reception Aesthetics). Journal of Beijing Institute of Technology (Social Sciences Edition). 5(6):8-11.

- Hermans, Theo, ed. (1985): The Manipulation of Literature: Studies in Literary Translation. Beckenham: Croom Helm.

- Holland, Robert (2007): Language(s) in the Global News: Translation, Audience Design and Discourse (Mis)representation. Target. 18(2):229-259.

- Holub, Robert C. (1984): Reception Theory: A Critical Introduction. London and New York: Methuen.

- Hsiao, Yi-jing (2006):〈台灣閱報民眾的人口結構及政治態度之變遷〉[Changes in Demographic Characteristics and Political Attitudes of News Readers in Taiwan: 1992-2004]. Taiwan Foundation for Democracy. 3(4):37-70.

- Hu, Jing-zhi and Zhang, Shou-ying (胡經之、張首映) (1988): 《西方二十世紀文論史》[A History of the Twentieth Century Western Literary Theories]. Beijing: China Social Sciences Press.

- Huang, Zhong-lian (2002): 《變譯理論》[Theory on Translation Variations]. Beijing: China Translation and Publishing Corporation.

- Hursti, Kristian (2001): An Insider’s View on Transformation and Transfer in International News Communication: An English-Finnish Perspective. In: Ritva Leppihalme, ed. Helsinki English Studies. The Electronic Journal of the Department of English at the University of Helsinki. Visited 27 March 2005, <http://www.eng.helsinki.fi/hes/Translation/insiders_view.htm>.

- Iedema, Rick, Feez, Susan and White, Peter (1994): Media Literary. Sydney: New South Wales Department of School of Education.

- Iser, Wolfgang (1974): The Implied Reader: Patterns of Communication in Prose Fiction from Bunyan to Beckett. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Iser, Wolfgang (1978): The Act of Reading. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Iser, Wolfgang (1993): Prospecting: From Reader Response to Literary Anthropology. Baltimore and London: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Jauss, Hans R. (1982): Toward an Aesthetic of Reception. (Translated by Timothy Bahti) Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Ji-hae, Kang (2007): Recontextualization of News Discourse: A Case Study of Translation of News Discourse on North Korea. The Translator. 13(2):219-242.

- Kirk, Sung Hee (1999): A Translation Analysis of Newsweek Korea. In: Jeroen Vandale, ed. Translation and the (Re)location of Meaning, Selected Papers of the CETRA Research Seminars in Translation Studies 1994-1996. Leuven: CETRA Publications, 401-422.

- Kuo, Sai-hua and Nakamura, Mari (2005): Translation or Transformation? A Case Study of Language and Ideology in Taiwanese Press. Discourse & Society. 16(3):393-417.

- Li, Defeng (2001): 〈國際新聞編譯方法探索〉[Adaptive Translation of International News from English into Chinese: An Exploration of Methods]. Journal of Translation Studies. 6:47-60.

- Li, Defeng (2009):《新聞翻譯: 原則與方法》[Translating Journalistic Texts: Principles and Methods]. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

- Lee, Chang-soo (2006): Differences in News Translation Between Broadcasting and Newspapers: A Case Study of Korean-English Translation. Meta. 51(2):317–327.

- Lefevere, André (1992): Translation, Rewriting, and the Manipulation of Literary Fame. London: Routledge.

- Liu, Qi-zhong (2004):《新聞翻譯教程》[Textbook on News Translation]. Beijing: China Renmin University Press.

- Ma, Jing-xiu (2006):〈英漢新聞編譯的求同存異策略〉[Seeking Common Ground While Preserving Discrepancies in English-Chinese News Adaptation]. Journal of Liaoning Technical University (Social Science Edition). 8(4):421-423.

- Martin, James and Rose, David. (2003): Working with Discourse: Meaning Beyond the Clause. 2nd ed. London: Continuum.

- Nida, Eugene A. (1964): Toward a Science of Translating. Leiden: E. J. Brill.

- Niranjana, Tejaswini (1992): Sitting Translation: History, Post-structuralism, and the Colonial Context. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Orengo, Alberto (2005): Localising News: Translation and the ‘Global-National’ Dichotomy. Language and Intercultural Communication. 5(2):168-187.

- Reah, Danuta (2002): The Language of Newspapers. 2nd ed. London: Routledge.

- Rich, Carole (2000): Writing and Reporting News. Belmont: Wadsworth Publishing Company.

- Robinson, Douglas (1997): Translation and Empire: Postcolonial Theories Explained. Manchester: St. Jerome Publishing.

- Rush, Ormond (1997): The Reception of Doctrine: An Appropriation of Hans Robert Jauss’ Reception Aesthetics and Literary Hermeneutics. Rome: Pontifical Gregorian University.

- Sidiropoulou, Maria (2004): Linguistic Identities Through Translation. Amsterdam: Rodopi.

- Siegal, Allan M. and Connolly, William. G. (1999): The New York Times Manual of Style and Usage. Revised and expanded ed. Toronto: Random House.

- Simon, Sherry (1996): Gender in Translation – Cultural Identity and the Politics of Transmission. New York: Routledge.

- Stetting, Karen (1989): Transediting – A New Term for Coping with a Gray Area between Editing and Translating. In: Graham Caie, Kirsten Haastrup, Arnt L. Jakobsen, et al., eds. Proceedings of the Fourth Nordic Conference for English Studies. Copenhagen: University of Copenhagen, 371-382.

- Toury, Gideon (1978): The Nature and Role of Norms in Literary Translation. In: James S. Holmes, José Lambert and R. van den Broeck, eds. Literature and Translation. New Perspectives in Literary Studies. Leuven: ACCO, 83-100.

- Tsang, Kuo-jen and Tsai, Yean (2001):〈新聞美學 — 試論美學對新聞研究與實務的啟示〉[News as Aesthetic Narrative: An Exploration]. Mass Communication Research. 60: 29-60.

- Tsai, Claire (2005): Inside the Television Newsroom: An Insider’s View of International News Translation in Taiwan. Language and Intercultural Communication. 5(2):145-153.

- Tsai, Claire (2006): Translation through Interpreting: A Television Newsroom Model. In: Kyle Conway and Susan Bassnett, eds. Translation in Global News: Proceedings on the Conference Held at the University of Warwick 23 June 2006. Coventry: The Center for Translation and Comparative Cultural Studies, University of Warwick, 59-71.

- Tsai, Claire (2009): Chasing Deadlines and Cross Borders: Translation in Taiwan Television News Production. Doctoral dissertation, unpublished. Coventry: University of Warwick.

- Valdeón, Roberto A. (2008): Anomalous News Translation: Selective Appropriation of Themes and Texts in the Internet. Babel. 54(4):299-326.

- VanDijk, Teun. A. (1988): News as Discourse. Hillsdale: L. Erlbaum.

- VanDijk, Teun. A. (1998): Opinions and Ideologies in the Press. In: Allan Bell and Peter Garrett, eds. Approaches to Media Discourse. Oxford: Blackwell, 21-63.

- Venuti, Lawrence (1995): The Translator’s Invisibility: A History of Translation. London: Routledge.

- Vuorinen, Erkka (1997): News Translation as Gatekeeping. In: Mary Snell-Hornby, Zuzana Jettmarová and Klaus Kaindl, eds. Translation as Intercultural Communication: Selected Papers from the EST Congress, Prague 1995. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 161-171.

- Wei, Ran (2000): Mainland Chinese News in Taiwan’s Press: The Interplay of Press Ideology, Organizational Strategies, and News Structure. In: Chin-chuan Lee, ed. Power, Money, and Media: Communication Patterns and Bureaucratic Control in Cultural China. Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 337-365.

- White, Peter (1997): Death, Disruption and the Moral Order: The Narrative Impulse in Mass-Media Hard News Reporting. In: Frances Christie and James R. Martin, eds. Genres and Institutions: Social Processes in the Workplace and School. London: Cassell, 101-133.

- White, Peter (1998): Telling Media Tales: The News Story as Rhetoric. Doctoral dissertation, unpublished. Sydney: the University of Sydney.

- Wu, Ding-yong (2006):〈接受美學對于報紙新聞傳播的啟示〉[The Influence of Receptive Theory on Newspaper Media]. Journal of South-Central University for Nationalities (Humanities and Social Sciences). 26(1):146-150.

- Xie, Chang-ching (2002):〈接受美學與新聞傳播效應〉[Receptive Aesthetics and Effects of News Communication]. Journal of Xuzhou Normal University (Philosophy and Social Sciences Edition). 28(4):58-60.

Liste des tableaux

Table 1

Case study data

Table 2

Comparison of the source and target nuclei

Table 3

Target satellites

Table 4

Identifying the news sources

Table 5

Combining, synthesizing and abridging

Table 6

Deleted portions

10.7202/002778ar

10.7202/002778ar