Résumés

Abstract

For the last 15 years, higher education has dramatically changed in terms of its mission and modes of delivery, involving many changes in how teachers approach course design and implementation, mainly because the final aim of learning is no longer the transmission of knowledge but the acquisition of competences for professional practice that promote graduates’ employability. One of the most affected processes has been evaluation, insofar as assessing these competences requires using strategies beyond the mere evaluation of declarative knowledge. Traditionally, evaluating in translation degrees has been said to be based on continuous assessment. However, the meaning and implications of ‘continuous assessment’ and its relation to ‘formative’ and ‘final’ assessment have often been misinterpreted as revealed in the literature. In this paper, we analyse the most common misconceptions in higher education assessment and, particularly, in translation teaching and learning. Furthermore, we present constructive alignment as a solid pedagogical framework for use in this field. Combining several formative methods and instruments is found to be most beneficial after reviewing the methods and instruments available and measuring the extent to which the intended learning outcomes were achieved as well as spotting individual learners’ needs. This paper emphasises the usefulness of continuous formative assessment as compared to continuous summative assessment, which measures the results of learning but does not act on the learning process.

Keywords:

- constructive alignment,

- formative assessment,

- summative assessment,

- continuous assessment,

- meaningful learning

Résumé

Au cours des quinze dernières années, la nature de l’enseignement supérieur a considérablement changé en ce qui concerne sa mission et les façons de faire. Cette évolution implique de nombreux changements dans la manière dont les enseignants gèrent la conception et la mise en oeuvre des cours, principalement parce que l’apprentissage ne vise plus la transmission de connaissances, mais l’acquisition de compétences professionnelles qui promeuvent l’employabilité des diplômés. L’un des processus les plus affectés est l’évaluation, en ce sens qu’évaluer des compétences requiert employer des stratégies qui vont au-delà de la simple évaluation des connaissances déclaratives. Traditionnellement, il a été soutenu que l’évaluation dans les cursus de traduction correspond à un système d’évaluation continue. Cependant, il y a eu des interprétations erronées de la signification réelle et des implications du terme « évaluation continue » et de sa relation avec l’évaluation « formative » et « finale ». Cet article vise à analyser les interprétations erronées les plus fréquentes dans le domaine de l’évaluation dans l’enseignement supérieur et dans l’enseignement de la traduction. Nous proposons ensuite l’alignement constructif comme cadre pédagogique solide. Conformément à l’examen des méthodes et des outils disponibles pour déterminer dans quelle mesure les acquis d’apprentissage escomptés sont atteints et identifier les besoins d’apprentissage, le type d’évaluation le plus efficace combine plusieurs méthodes et outils de formation. Cet article met l’accent sur l’utilité de l’évaluation continue formative, par opposition à l’évaluation continue sommative, qui n’agit pas sur le processus d’apprentissage.

Mots-clés :

- alignement constructif,

- évaluation formative,

- évaluation sommative,

- évaluation continue,

- apprentissage significatif

Corps de l’article

1. Introduction

From the students’ point of view, assessment is defined by the curriculum and determines what and how students learn insofar as what they think they will be tested on (Biggs and Tang 2011: 197). Most teachers and trainers will agree that assessment is central to the teaching and learning system and, yet, in higher education assessment has traditionally not been given much weight in course design because the prevailing concept of teaching has focused on what teachers did rather than on what students learnt or how they learnt it. Hence, traditional assessment was often norm-referenced and aimed at determining which students were best at remembering what they had been taught. In this context, poor results were attributed to student performance issues and not to teaching (Altbach, Reisberg, et al. 2009: 112). Over the last two decades, theoretical developments on student learning that prioritise learning outcomes (Biggs 1993) have brought about a shift in the higher education community (particularly in Europe and in The United States) from a teacher-centred input model to a model that is student-centred and based on outputs (Altbach, Reisberg, et al. 2009: 114). This paradigm shift, which involves a change from norm-referenced to criterion-referenced assessment, is best exemplified by the Bologna process and is flourishing dynamically in translator-training environments. Assessment in translation teaching and learning has been approached from a number of perspectives, the most common one being the evaluation of translations as products that contain errors, instead of the evaluation of the teaching and learning process, as pointed out by a number of authors in the Spanish context, which will be addressed in this paper (Rabadán and Fernández Nistal 2002; Kelly 2005; 2006; Varela and Postigo 2005; Conde Ruano 2009; Elena 2011; Presas 2011; 2012). Yet, the formative approach is gaining ground among Spanish university teachers, who are keen to adapt their methods to the current model.

In this paper, we review the literature on translation assessment within the Spanish context analysing the most common misconceptions in assessment in higher education. A solid pedagogical framework for use in constructivist translation teaching and learning is presented as well. We propose a critical review of the methods and instruments available to translation teachers, not only to measure the degree of acquisition of the competences included in the curriculum but mainly to spot individual learner’s needs and take the relevant measures as well. To this end, we describe the benefits of properly combining different types of assessment tasks (among which portfolios, projects, questionnaires or exams) and we highlight the importance of aligning each intended learning outcome (ILO) with the most suitable teaching and learning activities (TLAs) and assessment tasks (ATs) and rubrics to achieve the intended learning outcomes. In addition, the usefulness of the continuous formative approach is emphasised as compared to the continuous summative approach, which measures the results of learning but does not act on the learning process.

2. Literature review

Until the early Twenty-first Century research in the field of translation teaching and learning focused on the search for normalised assessment criteria and appropriate rating scales for measuring the seriousness of errors, but it did not identify specific learning outcomes beyond producing a “good translation” or relate such outcomes to the assessment criteria (Waddington 2000). The proposed rating scales were rooted in traditional assessment, which was based on two principles: validity and reliability (Kiraly 2000: 142; Waddington 2000). Waddington (2001) compared the quality of holistic assessment methods and error-based analytical assessment methods and found that combining these two approaches was most beneficial. However, he focused on measuring the effect of individual errors on the overall quality of texts because he considered errors to be the main factor in assessment and an aid to help teachers understand the learning process (Waddington 2003: 409). The main shortcoming of this approach was that it considered the quality of the final translated text to be the only key to the assessment of students’ performance, instead of considering the whole translation process and defining the key elements required to achieve the intended outcome, as had already been suggested by Hatim and Mason (1997: 164-175). Currently, many researchers still focus on defining a norm-referenced assessment method to improve grading of translations or measure the seriousness of errors in translations without further pedagogical considerations. Yet, a change from points-based grading methods to holistic ones became apparent in an empirical study performed by Garant (2009) in Finland, who found “almost polar opposites in attitudes towards grading in 1997 and 2001” and a clear consensus toward holistic grading in 2008, suggesting the emergence of a pedagogical basis for professional translator training (Garant 2009: 13).

Halfway between traditional approaches and the approach favoured by the current pedagogical models are the proposals made within the framework of translation competence research. In this field of work, Beeby (2000) used a model of evaluation based on the end product to assess the development of translation competence and to improve the training and learning processes as well as student performance. She suggested the use of exams and translation diaries, and the development of marking criteria that could be applied quickly and easily. Martínez Melis and Hurtado (2001) attempted to find a general principle that could be applied to all types of assessment by analysing the notion of translation assessment and identifying its characteristics in three areas: evaluation of published literary translations, evaluation of professionals at work and evaluation of trainees. They suggested the need to consider how to evaluate, which involves defining criteria and developing evaluation instruments. For these authors, there are three objects of assessment in translation teaching: the translation competence of students, the study plan and the programme. However, they built their proposal on pre-existing models of translation competence (PACTE 1998; 2000) that were too general for application within a student-centred approach, and on models of translation problems and errors that were devised for the evaluation of translations (Nord 1991; Hurtado 1995). Overall, they provided a good description or review of what should be assessed and how to use an error-based approach, but they did not integrate the various elements of assessment to produce a pedagogical proposal, insofar as they searched for and proposed criteria and instruments that were valid across all the areas of translation assessment. Also within the PACTE group, Orozco (2000) proposed an instrument to measure translation competence from B into A in the initial stages of training. Later Orozco and Hurtado (2002: 380) devised three instruments to measure and observe the acquisition of translation competence: one instrument measured the behaviour of translators when faced with translation errors, a second one measured translation errors and a third one measured knowledge about translation. The authors claimed that these instruments are useful for translation teaching in general because they allow teachers to measure their students’ progress and their own approach to teaching. Nevertheless, these instruments have only been used for research purposes or have been partially applied to translator training by some authors, including Kelly and Cámara (2008), who used the instrument for measuring knowledge as a tool for diagnostic assessment at the beginning of the year in order to further develop the curricular design posited by Kelly (2005), based on a mixed model that partially applied constructive alignment to assessment. More focused on translation teaching and learning were the proposals made by Adab (2000) and Van Lawick and Oster (2006). According to Adab (2000), evaluation helps determine the level of competence achieved and identifies problems related to translation competence and subcompetence. For this author, the use of clearly established criteria that are known by students “helps them move towards a more constructively useful and objectifiable form of translation assessment” (Adab 2000: 220). This aspect was also highlighted by Van Lawick and Oster (2006), who focused on the need to carefully plan and coordinate the objectives, competencies, activities and assessment methods of every course in the programme in order to ensure that students successfully acquire the envisaged cross-curricular competences. Orozco (2006: 47) acknowledged the importance of defining the competences and goals to be assessed, as well as of establishing how and when to assess, but did not consider the need to design the activities based on specific learning goals beyond the acquisition of translation competence, thus separating learning and teaching from assessment.

The proposals made by Adab (2000) and Van Lawick and Oster (2006) are in line with the constructivist approach favoured by the Bologna process (Presas 2011; 2012) and originally advocated in the field of translation pedagogy mainly by Kiraly (2000), who suggested the need to change traditional assessment practices and to include a professional perspective that helped students perform like professional translators. For Kiraly (2000: 143), the concepts of trustworthiness and authenticity became essential to guarantee that assessment would be credible, valuable and fair. He suggested including an authentic component by taking into consideration professional standards instead of using an error-based approach to assessment. Thus, the emphasis moved from errors to decision-making processes. Just as Adab (2000), he claimed that students should know the assessment criteria before performing the tasks, and he considered that those criteria should be expressed in terms of the “potential” employability of the group from a professional perspective. Although he did not provide specific examples of assessment instruments, he proposed the use of rubrics and portfolios. The need to include the professional perspective was also highlighted by McAlester (2000: 230), who suggested that the evaluation of the work of students should have predictive value with regard to their potential professional competence and should consider production issues such as timeliness, language quality and accuracy, as well as translation problems (McAlester 2000: 234).

In Spain, the need to further develop economical and fair assessment methods within a social constructivist framework was pointed out by Conde Ruano (2009: 231). However, this author argued for the need to define a common assessment framework based on translation theory for all translation teachers to remove arbitrariness from assessment processes (Conde Ruano 2009: 234). This is in contrast to the principles of constructivist assessment methods, which foster diversity and creativity (Biggs and Tang 2011: 263). For Conde Ruano (2009), the objects of assessment are the students and their capabilities as seen in their products (translations). In a constructive learning environment, it is the teaching and learning process which is at stake and, therefore, assessment must be concerned not only with products but also with processes, understood as the performance of teaching and learning activities that lead students to gaining the declarative and functioning knowledge needed to translate and correct translated texts. In this sense, assessment must be formative and must provide effective feedback to both students and teachers. With the arrival of the European Higher Education Area and its student-centred teaching-learning paradigm aimed at the acquisition of professional competences, the constructivist approach became more or less widespread, thus triggering a ‘pedagogical turn’ in the conception of assessment among a number of translation teachers, who started searching for new ways of teaching and evaluating that conformed better to such a paradigm and improved the teaching and learning process. Thus, in the last few years, most authors have been concerned with the search for appropriate assessment methods and instruments and with the incorporation of specific tasks different from the final exam and of instruments to assess the progress of translation trainees. Elena (2011) reviewed the characteristics of diagnostic, formative and summative assessment and identified five factors in the design of any teaching activity: level of development, types of learning tasks, types of relationship between learning and teaching, and types, criteria and instruments of assessment, which came close to an integral approach to assessment. She proposed incorporating alternative active methodologies such as cooperative learning, project-based learning, case studies and student portfolios and made a deeper analysis of the usefulness of the portfolio as a good tool for assessment of translation as a process. Similar analyses of the portfolio were proposed by Cáceres, Rico, et al. (2007), Tortadès (2006), who used real translation assignments and involved translation professionals in assessment, and Rojas (2004), who suggested a number of integrated assessment instruments that could be used separately, among which a form for self-diagnosis of the students’ capabilities, a record of aspects to improve, a checklist for the revision of translations and a rating scale, all of which could be adapted to different courses and levels. Hence, Rojas (2004) proposed an integral approach that aligned learning objectives, tasks and assessment and allowed for the incorporation of collaborative learning.

Non-Spanish authors such as Li (2006) and Federici (2010) also proposed the portfolio as the main assessment instrument in the translation classroom. Both authors highlighted the reflective nature of the method and the benefits of detailed feedback in the form of rubrics for improving and measuring students’ progress. Rubrics were also used by Presas (2011; 2012) within the meaningful learning model. The author proposed an assessment tool composed of a commented translation task, assessment benchmarks and a rubric that fulfilled criteria for validity and transparency (Presas 2011). A year later, she further developed the tool and proposed using self-assessment to determine the skills, strategies and resources applied to carry out a task, to assess the extent to which the process and product are satisfactory and the extent to which performing a task has an impact on learning itself (Presas 2012). The meaningful learning model adopted by Presas comes close to constructive alignment in that it acknowledges the need to align learning outcomes and objectives with assessment, but fails to align the activities or tasks proposed in the classroom with the intended learning outcomes and the assessment instruments used, as evidenced in the application of the model to the case study proposed by the author, who acknowledges the experimental nature of her analysis and points out the need to exclude arbitrariness from assessment by designing rigorous assessment instruments. The need to objectively evaluate the process was also highlighted by Guajardo, Acosta, et al. (2013) who, within the framework of authentic assessment, proposed using rubrics to that end.

As stated in the above paragraphs, most authors currently agree on three essential aspects of assessment: 1) the need to consider not only the product but also the process, 2) the need to adopt a complete assessment approach that relates the course competencies or objectives, the teaching and learning activities performed by students and the assessment methods and tasks used, and 3) the need to incorporate reflective and formative assessment to enhance learning. However, a solid theoretical framework or a valid application of the chosen framework is often lacking. In the next section, we highlight some common misconceptions in assessment as a pedagogical practice, proposing constructive alignment as a principal upon which to design translation courses, and we propose a set of formative assessment tasks composed of format and grading criteria that are useful for improving the teaching-learning process of both teachers and students.

3. Some common misconceptions in assessment

In the previous section, we referred to the ‘pedagogical turn’ fostered by the implementation of the student-centred approach in translation teaching and learning. The formative perspective adopted by European Universities has led many translation teachers to study, understand and apply many pedagogical principles that were not familiar to them previously. For this reason, the application of such principles has often been fuzzy and has brought about some misinterpretations, which are briefly described below:

a) Assessment is independent from teaching and learning. Traditionally, the assessment tasks used in translator training settings have been almost invariably the same, mainly translation exams and assignments, regardless of the specific intended outcomes or the teaching and learning activities performed throughout the year. Indeed, most of the authors cited in the introduction of this paper have considered the assessment of translations in isolation, instead of considering it as an essential component of teaching and learning. As stated by Li (2006),

even if many teachers realize that their assessment and evaluation procedures are important to their teaching, too many lack the requisite skill for developing and using them (…) Lacking knowledge in educational measurement impedes effective TT [Translation Teaching], for poor testing seriously weakens what is otherwise good teaching.

However, in a constructivist framework, assessment is only one piece of the teaching-learning puzzle, composed of curriculum, teaching method and assessment, which cannot be completed if only one piece is missing or defective. Thus, for our students to achieve the intended learning outcomes, such outcomes must be perfectly aligned with the teaching and learning activities and the assessment tasks and rubrics used to guide and measure their progress and performance.

b) Formative and summative assessment are opposing types of assessment. In the search for an effective assessment model that could help students improve their level of attainment, many teachers and researchers, such as Martínez Melis and Hurtado (2001: 277) or Varela and Postigo (2006: 122-123) in the field of translation have assumed that there is an antithesis between these two concepts defined in the late 1960s by Michael Scriven, who made a clear distinction between formative and summative evaluation in terms of their goals and of the use of the information gathered. However, there is no opposition as such between the two concepts: the goal of formative evaluation is to change the process on the basis of the information gathered, whereas the goal of summative evaluation is to provide information about whether a program has met its intended goals once the programme has been created and implemented. Many authors have misinterpreted this distinction, and formative and summative assessment have often been seen as two separate types of assessment requiring different types of assessment tasks, for instance, summative assessment includes examinations only, whereas formative assessment includes a range of activities (Martínez Melis and Hurtado 2001: 284). Rather, the terms formative and summative refer to different interpretations of information. Formative assessment can be defined as a planned process in which teachers and learners use assessment-based evidence to adjust their current learning tactics (Popham 2008: 6-7), whereas summative assessment is used to verify whether instruction has been effective. The key role of formative assessment in translation training has been highlighted by Kelly (2005), Orozco (2006), Li (2006), Federici (2010) and Presas (2012).

c) Time and purpose of assessment are equivalent. This common misconception is based on the false assumption that formative assessment is equivalent to continuous assessment and summative assessment is equivalent to final assessment. Why has this misconception been so frequent among university teachers? Because formative assessment is continuous in the sense that it provides effective feedback throughout the process, and summative assessment is final in the sense that it checks where students stand with respect to each of the intended learning outcomes for the course and, at the end of the year, these positions are converted into a grade. So, why is this assumption false? Because formative and summative refer to the purpose of assessment, whereas continuous and final refer to the timing of assessment. Thus, continuous assessment encompasses the formative and summative purposes of assessment. Also, summative assessment can be used to gather information at different times of the year according to course planning, and not only at the end of the year. In the field of translation, many teachers and researchers like Orozco (2006) identified formative assessment with a type of continuous assessment that consisted in the in-class correction of translation activities and the marking of some pieces of evidence collected throughout the course. Yet, in the described system, no individual feedback was given to students, such that the formative function of assessment was not present. This system could be called ‘continuous summative assessment,’ insofar as its only purpose was to verify whether instruction was effective at different times of the year, but apparently no adjustments were made to the teaching and learning techniques used. Actually, continuous summative assessment has been the traditional assessment method in the translation classroom. Throughout the year, translation assignments were corrected mostly in the classroom and some of them were corrected by the teacher using error-based rating scales, but no formative feedback was given to students on their individual performances during the translation process, such that there was a continuous correction of products aimed at spotting errors probably with hardly any influence on the students’ learning process (Orozco 2006; Van Lawick and Oster 2006; Oster 2006). At the end of the year, a final assignment and a final exam usually determined the level of attainment of students (Martín Martín 2010). In a formative environment, assessment is continuous, and assessment tasks and their rubrics can be used formatively and/or summatively. For this reason, students must know exactly which assessment tasks are formative and which are summative (Biggs and Tang 2011: 197).

4. A solid pedagogical framework: Constructive alignment

4.1. Why constructive alignment?

What is constructive alignment?

‘Constructive’ comes from the constructivist theory that learners use their own activity to construct their knowledge as interpreted through their own existing schemata. ‘Alignment’ is a principle in curriculum theory that assessment tasks should be aligned to what it is intended to be learned, as in criterion-referenced assessment. […] The teacher’s tasks are to set up a learning environment that encourages the student to perform those learning activities, and to assess student performances against the intended learning outcomes.

Biggs and Tang 2011: 97

The constructivist principles behind constructive alignment are in agreement with the principles behind the new paradigm used in higher education. Also, the alignment of the intended outcomes, the teaching and learning activities, the assessment tasks and the criteria used to assess such tasks makes this approach a highly consistent one insofar as all components of the system support each other. In planning a course based on constructive alignment, teachers must reflect deeply on which particular outcomes are specific to the course and relevant to students’ learning in order to be capable of aligning each ILO with the relevant TLAs and ATs. Constructive alignment focuses on what and how students are to learn, rather than on what topics the teacher is to teach, and specifies not only what is to be learned, the topic, but how it is to be learned and to what standard. Besides, constructive alignment is flexible and can be applied in a wide variety of contexts and to different teaching styles. Thus, it may include declarative and functioning knowledge, formative and summative assessment, norm-referenced and criterion-reference assessment, which allows for different combinations of assessment tasks and formats depending on the purpose of the task. In addition, the teaching and learning activities can be designed for large classes, small classes, groups or individuals, and may be teacher-managed, peer-managed or self-managed, as best suits the ILO, and the criteria are specifically designed to allow judgement as to student’s performance in the task leading to the ILO (Biggs and Tang 2011: 104-105).

4.2. Can constructive alignment be applied to translator training?

Of course, it can. Actually, if applied systematically, constructive alignment applied to translation courses allows for establishing a more fine-grained correspondence between specific items within the envisaged competences or subcompetences, the activities carried out by students and the assessment used. As translation teachers, we often select general competences for our course, competences that are so general that they cannot be acquired through a specific activity or set of activities. This approach has been common in translation pedagogy, particularly among ‘translation competence researchers’ (Tortadès 2006: 103; Orozco 2000; 2006; Martínez Melis and Hurtado 2001; Orozco and Hurtado 2002). In addition, institutional constraints impose the use of exams (Kelly 2005: 136), and this is the reason why final exams or assignments have been so common: by selecting general competences for designing our course we have been focusing on the overall picture and the final product, rather than on the steps required to work on the acquisition of such competences, and have consequently felt the need to assess the overall picture instead of assessing both the final one and the process required to achieve this. The key to the successful implementation of constructive alignment in a translation course is defining the intended learning outcomes beyond the translation competences and subcompetences and their integration with the other components of teaching. According to Biggs and Tang (2011), constructive alignment provides us with a conceptual framework that allows us to reflect on the following three questions, which will guide the stages of course planning and correspond, respectively, to three essential components of teaching as mentioned in previous sections; namely, the curriculum, teaching method and assessment:

1) What do I want my students to learn? To apply constructively aligned assessment to translation teaching, we must be well aware that the intended final learning outcome to ‘correctly translate a text from a language into another’ must be divided into more specific intended outcomes that will depend on the types of texts or pairs of languages involved. It is the teacher who, based on previous research, experience and market demands, sets the specific intended learning outcomes for the course. First, the teacher will determine the needs of the students in terms of the theoretical concepts (declarative knowledge) that are essential to acquire the expected competences and strategies (functioning knowledge), as well as the specificities of the type of translation he or she teaches, be it legal, scientific, technical, economic or literary, among others. Once the needs are identified, he or she will define the relevant intended learning outcomes and express them as verbs that indicate the level of understanding and performance they are expected to achieve. Garant (2009: 14) found that assessment depends also on the views that teachers have on translation as an activity. The way, we, as teachers perceive translation will affect the selection of contents, teaching and learning activities and assessment tasks used. For this reason, it does not seem advisable to try to apply general models of translation assessment or translation competence assessment without a deep reflection on the needs of our students, as suggested by Kelly and Cámara (2008). This stage of the planning process is essential but cannot be completed without considering the following two aspects, which give us the key to correct alignment.

2) What is the best way considering the circumstances and within the available resources of getting them to learn it? Two specific aspects must be considered at this stage of course planning:

a) What are the activities that will help my students progress toward the acquisition of the intended learning outcomes? How and when must they perform such activities? Will there be different paces of progression within the classroom that will require different schedules? Can those differences in the pace of progression be corrected with specific measures, such as a different schedule for some students or the use of collaborative work? Do all the activities envisaged in the planning correspond to the intended learning outcomes? Do I expect that all the activities envisaged in the course will help my students learn how to translate the relevant types of text? Such an approach involves more activities than ‘just translating and correcting translations’ because of the complexity of the processes involved in the translation activity, which will vary depending on the type of translation.

b) Do I, my institution, and my students have the resources required, be they cognitive, attitudinal or material? This is a highly relevant question for the design of any course, particularly within constructivist translator training insofar as designing a course without considering the actual circumstances or resources can easily lead to failure. For example, we agree that collaborative work with real cross-course translation assignments is an optimal way to acquire the learning outcomes intended for our courses. Yet, to successfully implement this type of activity, we must make sure that we have all the resources required for the activity: vertical and horizontal coordination within the degree program, collaboration from teachers of other courses, professional tools and software licenses, professional reviewers, the legal requirements for paid work, not to mention translation competence at professional standards, which is only possible, at least in theory, at the end of the degree programme. If any of these resources are lacking, then our students will not achieve the intended outcomes and our planning will have failed. Therefore, every project or activity must be devised or adapted to fit our intended outcomes, circumstances and resources.

3) How can I know when and how well they have learned it? This question involves assessment issues such as type of assessment (diagnostic/formative/summative), assessment tasks (format and criteria) and scheduling or timing of assessment. When discussing the previous components of teaching, we made it clear that there must be a complete three-way correspondence in ILOs, TLAs and TAs. Therefore, at this stage of planning, we must have defined our students’ needs and the activities required to fulfil those needs, as well as the best times to perform each activity. Now, it is the time to determine to what extent our students have reached the intended outcomes, to ensure that they are able to achieve these outcomes at the right time and to allow for alternative ways to reach the outcomes in case they are not learning as we want them to, that is, with the appropriate priorities, level of performance and pace of learning and through the appropriate activities. When it comes to designing course assessment, five questions must be answered:

What is being assessed?

When must each ILO and activity be assessed?

How is it going to be assessed?

Who will be the agents involved in assessment?

Why?

In the next section, we will delve into the specific case of translation teaching and learning, but at this point a general answer to all these questions can be advanced thus laying the basis for the discussion in the next section. In a formative assessment scenario, every activity performed by our students should be assessed to some extent, because it must be based on effective feedback so that students may reorient their learning according to the objectives of the course as highlighted by Presas (2011; 2012). In order for students to reorient their learning throughout the course, assessment must be continuous and progressive and must conform to the time allotted for the course schedule. This means that feedback on each course unit should be given to students before moving on to the next one so that feedback is still relevant and effective. Yet, what are the best types of assessment to retrieve the information we need as course facilitators? What formats and criteria are most suitable for each type of activity? How can we transform the judgement about how well students’ performances meet the criteria into standard grading criteria? A variety of approaches, formats and criteria are available to university teachers, who should select them based on the ILOs and TLAs included in the design of the course. Overall, we will use a formative approach to guide our students during their learning process, a summative approach to prioritise the learning outcomes, give variable weight to each activity according to the importance of the learning outcomes that correspond to each activity and thus obtain gradings; and a diagnostic approach to retrieve information about our progress as teachers and about the progress of our students at different stages of the course. At this stage, we must be well aware that assessing every activity does not necessarily mean that the teacher corrects and marks it all: assessment can be performed by the teacher, the students or professionals depending on the type of feedback required and its purpose. However, it is the teacher who must provide students with the criteria that will be used to assess each task and to explain to them which tasks will be assessed summatively so that they understand the relevance of each activity or task and how they are related to the course ILOs. Finally, the why question affects the previous four questions and will depend on our approach to teaching and learning. Nevertheless, it is essential that the conductors of the course know the exact answer to this question insofar as it is the key to successful course planning and implementation.

Hence, through constructive alignment we question what we are doing during those crucial stages and reflect on whether there are other ways to carry them out leading to a transformation and eventual improvement of our approach to teaching and learning through a process that consists of four stages: reflect-plan-apply-evaluate.

5. Constructively aligned assessment in translation

In order to successfully design constructively aligned teaching and assessment, we need to: 1) anticipate all the elements of our teaching and learning programme related to assessment, namely, the main theoretical concepts and skills needed to correctly translate and revise a text, the most suitable teaching and learning activities to achieve the ILOs, the contribution of each activity to the acquisition of the ILOs, the most suitable evaluation method for each activity, the specific assessment tasks involved in formative and summative assessment, the most suitable assessment format and criteria for each task, and lastly the agents involved in assessment, and 2) align each activity with specific formative objectives and the most suitable assessment method, in such a way that assessment covers every aspect of learning.

Once we have defined the relevant ILOs and designed the most suitable TLAs to achieve these ILOs, we must select the assessment tasks that indicate whether and how the students can meet the criteria contained in the ILOs. The ATs must address the same type of skill or competence as the TLAs so that the alignment will be complete and meaningful. To do so, the verbs used to define our ILOs, such as ‘understand,’ ‘explain,’ ‘apply,’ ‘hypothesize,’ ‘revise’ or ‘translate,’ must be embedded in the teaching and learning activities and in the assessment tasks, acting as markers for the alignment. Finally, we need to construct a grading scheme or set of criteria for those tasks. In addition to providing both students and teachers with a measurement of their level of attainment with regard to the ILOs, a good grading scheme must help students perform their tasks and improve their performance according to what is expected and must help teachers determine the final grades. Thus, we can affirm that every AT is composed of two elements, format and grading criteria, in which neither can be separated.

The distinction between teaching and learning activities, assessment tasks and assessment grading criteria has not always been clear. For example, Martínez Melis and Hurtado (2001: 284-285) differentiated two types of assessment instruments for measuring the students’ translation competence: grading scales and ‘other instruments’ or ‘assessment exercises,’ as the authors called them later in their paper. Yet, the category ‘assessment exercises’ included a wide variety of in-class activities, such as translation exercises, comparative translations, reasoned translation, the solution of isolated problems, comprehension exercises, multiple-choice tests and questionnaires, translation diaries or documentation exercises that can be used either as TLAs or ATs according to the purpose of the task. When used as ATs, each of these formats must be accompanied by a set of grading criteria that provides students with formative feedback. Accordingly, grading scales and assessment exercises cannot be considered as two separate types of assessment instruments, insofar as both categories are interdependent.

5.1. Assessment formats and grading criteria for constructively aligned translation teaching and learning

Because constructively aligned teaching is based on careful and reflective course design, the ATs that can be used within this theoretical framework are vast and will depend on our approach to translation and translation training. Actually, the variety of TLAs available to translation teachers that has already been described above by the authors cited in this paper, among others, can be fully exploited when correctly aligned with ILOs and ATs. As suggested earlier in this paper, assessment tasks are composed of task format and task grading criteria. Formats of assessment are limited, but some of them have proved particularly effective in student-centred approaches in which assessment is used to enhance learning and, more specifically, in translation courses focused on the acquisition of the knowledge and skills required to successfully complete a translation. In this section, we suggest four assessment formats for use in constructively aligned teaching and learning: questionnaires, portfolios, projects and exams. Correctly combining these formats in the design of our course will allow us to design a wide variety of assessment tasks according to the assessed ILOs. In addition, we will discuss the main grading instrument in constructive alignment, rubrics, and we propose some examples of aligned TLAs, ILOs and TAs, along with the agents involved and the relevant methods of assessment.

5.1.1. Assessment formats

5.1.1.1. Questionnaires

Questionnaires have been widely used in reflective translation teaching and learning (Martínez Melis and Hurtado 2001; Waddington 2001; Orozco and Hurtado 2002; Presas 2011; 2012), mainly to retrieve information about the students’ opinions regarding their previous knowledge or our performance as teachers (diagnostic assessment), to consider the steps needed to perform a given translation task (formative assessment), and to measure to what extent students have assimilated “the methodological and professional principles, the theoretical content, the extralinguistic knowledge and the psychological aptitudes” (Martínez Melis and Hurtado 2001: 285) required to achieve the intended learning outcomes (formative and summative assessment), but also to ascertain the attitudes of students towards the proposed tasks or their ability to work in groups (Bogain and Thorneycroft 2007: 4). Sometimes, teachers have limited the use of questionnaires to self-assessment, as did Presas (2011). Indeed, in a formative assessment environment, questionnaires are best suited for activities that help students reflect on their own progress and on teachers’ performance. In table 1, we suggest a selection of possible types of questionnaires for use in translation teaching and learning and align them with specific ATs and ILOs for which they are particularly well suited. As shown in the table, the agents involved are mainly students when performing self-assessment activities or students and teachers when they are used for diagnostic purposes.

Table 1

Assessment formats: Questionnaires

5.1.1.2. Portfolios

A portfolio is a collection of a student’s representative work. As such, the portfolio format allows for the assessment of functioning knowledge through a wide range of tasks that may include all the types of TLAs. Li (2006) and Federici (2010) proposed the portfolio as the main assessment format in the translation classroom. As pointed out in the literature review section, both authors highlighted its reflective nature and the benefits of detailed feedback in the form of rubrics for improving and measuring students’ progress. Li (2006) focused on the need to integrate teaching and testing to achieve effective learning, which requires constant feedback in the form of detailed descriptions of what should be done and helps students focus on learning how things are done instead of the measurement of their errors. Portfolio assessment is highly compatible with constructively aligned teaching and learning because it creates a real sense of harmony between instructional goals and assessment and thus motivates students to perform better (Biggs and Tang 2007: 95-96). Motivation was also one of the arguments put forward by Federici (2010), who proposed an experimental criterion-referenced system to assess students’ translation as a process, particularly a revision process. The experimental system was grounded on reflective practice and revision. In this system, the portfolio was combined with two other formats, namely a translation commentary referring to translation theories and a final exam simulating ‘working conditions’ (Federici 2010: 173). Yet, as acknowledged by the author, the assessment system is designed to cater to different learning styles, but no reference is made to the intended learning outcomes or the best way to achieve them through the activities and assessment modalities used. In this system, the search for improvement and for self-correction becomes the focal point. According to the author,

the chance to resubmit their material once corrected works as an incentive towards engaging with their work once more. The students know the areas in which they could improve; they cannot rely on corrections, but they are given time to revise their translation, thus increasing the quality of their output. The possibility to resubmit enforces a self-assessment that is only positive

Federici 2010: 184

The usefulness of portfolio assessment to educate translation students in study and reflective skills was also highlighted by Garant (2009: 15), whereas Rojas Campos (2004) insisted on the need to carefully design the course and to combine different assessment methods and tasks to enhance learning and to improve and simplify the teaching practice.

5.1.1.3. Projects

The project format focuses on functioning knowledge. Projects can be performed individually or in groups. As stated by Fernández and Sempere (2010: 141), translation projects are conceived as learning experiences in which students will have to face a variety of problems, such as translation-related problems, technical problems, management problems and team-work problems, that will help them achieve various ILOs in a coherent and constructive manner. As in portfolios, projects may include a wide variety of TLAs beyond the final product that cover all the aspects of teaching and learning. Each of the activities included in a translation project must be aimed at acquiring the competences required to produce a translation that meets professional standards (Veiga Díaz 2012: 401-403). Assessment of projects demands deep reflection from teachers, who must assign a fair weight to a complex task often developed by more than one student. Although group projects are best suited to train group work skills, students tend to focus on their own task and disregard the contribution of the other members of the group to the project. For this reason, the project format is usually combined with other formats such as questionnaires or exams that help teachers determine the extent to which individual students are aware of how their contribution fits into the project as a whole. Projects have been seen as the key to professional translation training (Kiraly 2000; 2005; 2012). Yet, as pointed out earlier in this paper, the design and assessment of translation projects must be adapted to the circumstances and the resources available.

5.1.1.4. Exams

Translation exams, together with translation assignments, have been the focal points of assessment for decades and have been used by translation teachers either alone or in combination with other instruments with different approaches to translator training, among whom Martínez Melis and Hurtado (2001), Oster (2006), Conde Ruano (2009), Khanmohammad and Osanloo (2009), Martín Martín (2010), or Elena (2011) are examples. Traditionally, exams have been used summatively with the main aim of assigning a grade to our students’ performance. In constructively aligned assessment of translation teaching and learning, exams can be used summatively and formatively for measuring the extent to which our students have achieved particular ILOs related to both declarative and functioning knowledge. Exams designed to assess ILOs related to declarative knowledge will require the student to extensively write about the theoretical concepts needed to successfully perform a translation. The usefulness of this format is limited in constructive teaching and learning, but it can be used as a prioritising tool to make our students aware of the importance of remembering some strategic concepts while translating a text and to spot the concepts that are most difficult to understand. Also, the exam format can be used to test whether our students are able to perform at the expected standard under controlled circumstances. When using this format, we must be well aware of the ILOs involved (for example, solving problems under pressure, applying particular translation strategies), their importance with respect to the objectives of the course (How much weight will this task be given?), as well as the correct scheduling of the activity to verify the extent of the progress and the viability to act on the learning process (Will the exam be scheduled at the end of the year or at the end of a given unit or block? Will such scheduling allow for my students to use feedback to improve their learning?). For exams to be formative, the grading criteria used must be descriptive of the expected characteristics of the product and students must receive detailed feedback so that they can improve their performance. When students work in groups, exams can be a good format for measuring individual performance. Table 2 summarizes the main types of exams used in translation teaching settings.

Table 2

Assessment formats: Exams

5.1.2. Grading criteria: Rubrics

In this subsection, we will focus on rubrics as the perfect instrument for establishing a formative grading scheme that help students achieve the intended learning outcomes of a translation course (Rojas Campos 2004; Li 2006; Federici 2010; Presas 2011; 2012; Guajardo, Acosta, et al. 2013). “A rubric is a coherent set of criteria for students’ work that includes descriptions of levels of performance quality on the criteria” (Brookhart 2013: 4). Rubrics are particularly useful in constructively aligned assessment for translator training because they allow both students and teacher to evaluate progress against a specified set of criteria defined usually by the teacher based on curriculum goals and intended learning outcomes. Because rubrics help coordinate instruction and assessment, when working with well-constructed rubrics, alignment is guaranteed and structured feedback is contained in the tool, which makes assessment of the performance of large groups of students easier and faster. Why are rubrics particularly useful in translator training settings? It is because the main purpose of rubrics is to assess students’ performances by observing the process of doing something or the product of their work and give them feedback about the degree of performance quality, meeting the needs of translation students: feedback on the translation process, the translation as a product and the quality of both process and product. Rubrics are also particularly useful in the assessment of cross-curricular competences insofar as they can be used to assess physical skills, use of equipment, oral communication or work habits, as well as translations, essays, reports, commentaries or any other academic products that demonstrate understanding of concepts (Brookhart 2013: 4-5). The composition of rubrics is flexible and can be task-specific or prepared for use with a number of activities, such that it can be reused with tasks that refer to the same learning outcome and support students self-evaluation. Accordingly, rubrics can be used as the grading criteria complementing all the assessment formats discussed in the previous subsections of this paper: questionnaires, portfolios, projects and exams.

Furthermore, rubrics can be analytic or holistic: analytic rubrics describe the work of students based on each criterion separately, whereas holistic rubrics enable an overall judgment by evaluating all the criteria simultaneously. Combining analytic and holistic allows students to understand different levels of detail: detailed analytic rubrics allow them to identify specific errors, whereas holistic rubrics allow them to see the consequences of errors, group them into different categories and identify areas where they are performing best. According to Brookhart (2013: 7-13), analytic rubrics give diagnostic information to teachers and formative assessment to students. They are easier to link to instruction and can be adapted to summative assessment but are more time-consuming than holistic rubrics, which are good for summative assessment but do not convey information about what to do to improve so, therefore they are not good for formative assessment. Rubrics can be shared with students at the beginning of an assignment to help them plan and monitor their own work according to the qualities it should have and thus focus on developing the skills required to successfully complete the task. Yet, to be effective, rubrics must be very well constructed. Because well-constructed rubrics are based on deep reflection on the criteria by which learning must be assessed, they help us avoid confusing the activity with the learning goal. In other words, they help us avoid confusing the completion of the task with learning, as has commonly been the case with continuous assessment in translator training. For students, a rubric is a cohesive tool that allows them to tackle their work based on a set of criteria, receive feedback, revise and apply what has been learned to another task that will be based on the same criteria, thus enhancing learning.

The preparation of evaluation sheets or rubrics that are valid for the evaluation of translations has been a concern among translation trainers, but many of them have found it difficult to find the right level of detail, as they attempted to create a rubric that was valid for any translation. In Spain, the earliest attempt was made by Robinson (1998), who tested the validity of a rubric by demonstrating that it could be used for different groups of students with similar results. Robinson (1998: 580-581) claimed that the proposed scale was suitable for the holistic and detailed correction of exams and proposed its use as an active pedagogical tool for teaching translation, since it was seen to be useful in self- and peer-assessment. Years later, Robinson (2005) proposed the use of a rubric containing assessment criteria that were known to students to guarantee the reliability, validity and transparency of translation exam marking. More recently, Khanmohammad and Osanloo (2009), reviewed the rubrics proposed in the field of translation assessment and have proposed a detailed rubric including five items, accuracy, equivalence, register and culture, grammar and style, and shifts, omissions or additions, whereas Gallego (2011) proposed an automated revision-correction task that could be revised by any student in the classroom. Toledo Báez (2012) proposed a very simple holistic assessment rubric with only two criteria (transfer quality and writing quality) and integrated it with a software to assess electronic assignments. Similarly, Li (2006) adopted a simple analytical grid used for language courses to assess translation correctness and Federici (2010: 182) devised a feedback sheet where students found the grade range clearly stated and reference to the criteria used to mark translations.

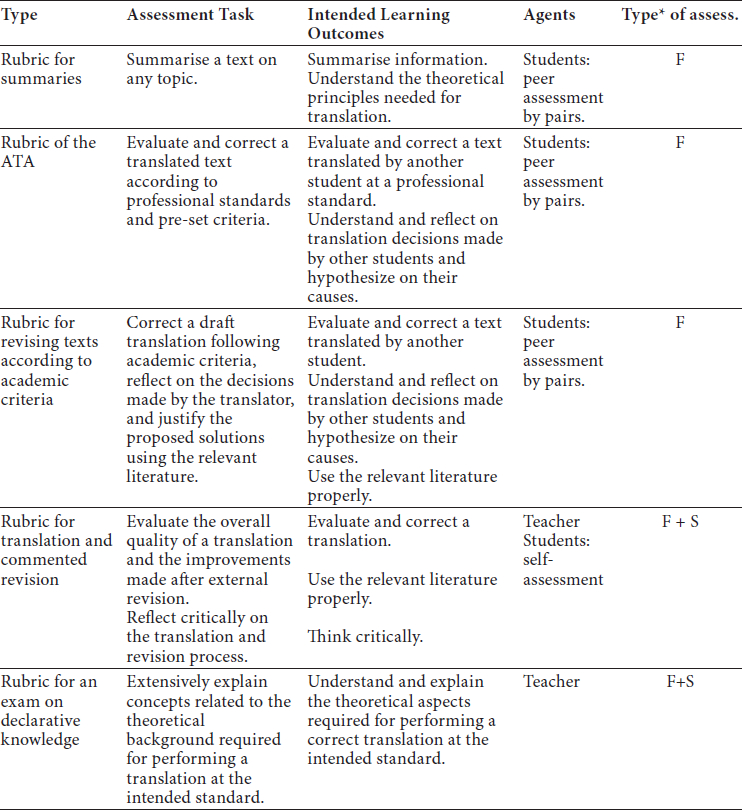

The reviewed rubrics were aimed at assessing translations. Yet, as suggested above, the usefulness of rubrics in translation pedagogy goes far beyond the mere assessment of translations. Within the meaningful learning approach, Presas (2012) used rubrics for summative assessment of the performance of her students for a number of activities. She acknowledged the difficulty of stating good rubrics, particularly of writing accurate performance-level descriptions, and, actually, the rubrics proposed by the author showed various limitations: overgeneralised performance-level descriptions, the scoring of more than one content-area skill at a time (for example, objectivity, accuracy and detail were scored as a single criterion) and the mixing of criteria with learning outcomes (for instance, the ‘presentation’ criterion included two subcriteria: spelling typographical errors and correct implementation of norms of layout, which could actually be understood as learning outcomes), all of which were identified by Popham (1997) as the main flaws of rubrics. Nevertheless, the approach adopted by Presas (2012) is a real example of formative assessment and of student-centred teaching and learning. Table 3 shows some of the rubrics that can be used to assess the performance of translation trainees, along with the relevant assessment tasks and ILOs, the agents and the type of assessment involved, and Table 4 illustrates a rubric used to assess the ILO ‘explain,’ typically assessed through a report, a commentary or an exam-format assessment task.

Table 3

Rubrics

Table 4

Example of a rubric to assess the ILO ‘Explain theoretical concepts related to translation’ (adapted from Biggs and Tang 2011: 42)

The rubric proposed in Table 4 allows for giving formative feedback to our students and to grade our students’ performance. In addition, it enables students to identify the key aspects of the assessment task, so that the criteria contained in the rubric will help them improve their learning process.

6. Conclusions

The analysis of the methods commonly used to assess the performance of translator trainees has revealed a transition from analytic error-based approaches (in which assessment was used to measure the ability to produce a translation at the end of the teaching and learning period) to holistic criterion-referenced approaches, in which criteria are used formatively as a guide to enhance learning, usually within a constructive framework. Thus, emphasis has moved from translation errors to decision-making processes, so errors are no longer used to penalise students but to construct knowledge by giving effective feedback to students and to teachers by using both analytic and holistic methods. Yet, the approaches to assessment have often lacked a sound theoretical background, thus allowing for misconceptions and poor applications of theoretical concepts in the field of pedagogy. Constructive alignment provides a solid and integral framework to assess the performance of translation trainees and is determined by the following factors:

Correspondence of intended learning outcomes, tasks and assessment methods.

Combined use of different assessment instruments to detect and correct product- and process-related errors during the process and to measure the level of attainment of the intended learning outcomes.

Selection of the most suitable criteria to assess each activity.

Constant feedback for every activity.

If properly designed and applied, the four types of assessment tasks proposed in this article (questionnaires, portfolios, projects and exams) in combined use are best suited for a constructively aligned assessment in translation training insofar as they can be used diagnostically, to detect strengths and weaknesses at various stages of the teaching and learning process; formatively, to enhance learning by giving continuous effective feedback; and summatively, to measure the level of attainment of the ILOs and to assign a grade to students.

Parties annexes

Bibliography

- Adab, Beverly (2000): Evaluating Translation Competence. In: Christina Schäffner and Beverly Adab, eds. Developing Translation Competence. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 215-228.

- Altbach, Philip, Reisberg, Liz and Rumbley, Laura (2009): Trends in Global Higher Education: Tracking an Academic Revolution: A Report Prepared for the UNESCO 2009 World Conference on Higher Education. Paris: Unesco.

- Beeby, Allison (2000): Evaluating the Development of Translation Competence. In: Christina Schäffner and Beverly Adab, eds. 2000. Developing Translation Competence. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 185-198.

- Biggs, John (1993): From theory to practice: A cognitive systems approach. Higher Education Research and Development. 12(1):73-85.

- Biggs, John and Tang, Catherine (2011): Teaching for Quality Learning at University: What the Student Does. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

- Bogain, Ariane and Thorneycroft, Val (2007): Translation, theory and practice: an interactive approach. Studies about Languages. 11.

- Brookhart, Susan M. (2103): How to create and use rubrics for formative assessment and grading. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

- Cáceres Würsig, Ingrid, Rico Pérez, Celia and Strotmann, Birgit (2007):Portafolios integral del alumno de traducción e interpretación. Madrid: Editorial Rueda.

- Conde Ruano, Tomás (2009): Propuestas para la evaluación de estudiantes de traducción. Sendebar. 20:231-255.

- Elena, Pilar (2011): El aprendizaje activo en traducción y su evaluación. Estudios de Traducción. 1:171-183.

- Federici, Federico (2010): Assessment and quality assurance in translation. In: Valerie Pellatt, Kate Griffiths and Wu Shao-Chuan, eds. Teaching and testing interpreting and translating. Oxford: Peter Lang, 171-190.

- Fernández Prieto, Chus and Sempere Linares, Francisca (2010): Shifting from translation competence to translator competence. In: Valerie Pellatt, Kate Griffiths and Wu Shao-Chuan, eds. Teaching and testing interpreting and translating. Oxford: Peter Lang, 131-148.

- Gallego Hernández, Daniel (2011): Una alternativa a la revisión de traducciones: aplicación de las TIC a la enseñanza de la traducción económica. In: Tortosa Ybáñez, María Teresa, Álvarez Teruel, José Daniel y Pellín Buades, Neus. IX Jornadas de Redes de Investigación en Docencia Universitaria: nuevas titulaciones y cambio universitario. Alicante: Universidad de Alicante.

- Garant, Mikel (2009): A Case for Holistic Translation Assessment. In: Jyrki Kalliokoski, Tuija Nikko, Saija Pyhäniemi and Susanna Shore, eds. AFinLA-e Soveltavan kielitieteen tutkimuksia. 1:5-17.

- Guajardo Martínez, Ana Gabriela, Acosta Domínguez, Sonia, Basich Peralta, Evangelina and Lemus Cárdenas, Miguel Ángel (2013): La evaluación auténtica: las rúbricas y la evaluación de la traducción. In: Congreso Internacional de Idiomas 2013. Sociedad en el Siglo XXI:Vivir las lenguas. Mexicali: Universidad Autónoma de Baja California.

- Hatim, Basil and Mason, Ian (1997): The Translator as Communicator. London: Routledge, 164-175.

- Hurtado Albir, Amparo (1995): La didáctica de la traducción. Evolución y estado actual. In: Purificación Hernández and José María. Bravo, dirs. Perspectivas de la traducción. Valladolid: Universidad de Valladolid, 49-74.

- Kelly, Dorothy (2005): A Handbook for Translator Trainers. A Guide to Reflective Practice. Manchester: St Jerome.

- Kelly, Dorothy (2006): Adecuación de los sistemas y criterios de evaluación a los objetivos y resultados previstos del aprendizaje en la formación universitaria de traductores. In: Sonia Bravo Utrera and Rosario García López, eds. Estudios de Traducción: problemas y perspectivas. Las Palmas de Gran Canaria: ULPGC, 717-729.

- Kelly, Dorothy and Cámara Aguilera, Elvira (2008): La evaluación diagnóstica en la formación de traductores: el análisis de necesidades como elemento esencial de la programación. In: Luis Pegenaute, Janet Decesaris, Mercedes Tricás and Elisenda Bernal, eds. Actas del III Congreso Internacional de la Asociación Ibérica de Estudios de Traducción e Interpretación. La traducción del futuro: mediación lingüística y cultural en el siglo XXI. Barcelona 22-24 de marzo de 2007. Vol. 2. Barcelona: PPU, 225-236.

- Khanmohammad, Hajar and Osanloo, Maryam (2009): Moving toward Objective Scoring: A Rubric for Translation Assessment. Journal of English Language Studies. 1(1):131-153.

- Kiraly, Donald (2000): A Social Constructivist Approach to Translator Education. Empowerment from Theory to Practice. Manchester: St Jerome.

- Kiraly, Donald (2005): Project-based learning. A case for situated translation. Meta. 50(4):1098-1111.

- Kiraly, Donald (2012): Growing a Project-Based Translation Pedagogy: A Fractal Perspective. Meta. 57(1):8-95.

- Li, Haiyan (2006): Cultivating Translator Competence: Teaching and Testing. Translation Journal. 10(3).

- McAlester, Gerard (2000): The evaluation of translation into a foreign language. In: Christina Schäffner and Beverly Adab, eds. Developing Translation Competence. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 229-241.

- Martín Martín, José Miguel (2010): Sobre la evaluación de traducciones en el ámbito académico. Revista Española de Lingüística Aplicada. 23:229-245.

- Martínez Melis, Nicole and Hurtado Albir, Amparo (2001): Assessment in Translation Studies: Reseach Needs. Meta. 46(2):272-287.

- Nord, Christiane (1991). Textanalyse und Übersetzen. Heidelberg: J. Groos Verlag.

- Orozco Jutorán, Mariana (2000): Building a Measuring Instrument for the Acquisition of Translation Competence in Trainee Translators. In: Christina Schäffner and Beverly Adab, eds. Developing Translation Competence. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 199-214.

- Orozco Jutorán, Mariana (2006): La evaluación diagnóstica, formativa y sumativa en la enseñanza de la traducción. In: María José Varela Salinas, ed. La evaluación en los estudios de traducción e interpretación. Seville: Bienza, 47-68.

- Orozco Jutorán, Mariana and Hurtado Albir, Amparo (2002): Measuring Translation Competence Acquisition. Meta. 47(3):375-402.

- Oster, Ulrike (2006): Diversificación de la evaluación en la enseñanza de lengua alemana para traductores. In: Actes de la VI Jornada de Millora Educativa i V Jornada d’Harmonització Europea. Castellón: Publicacions de la Universitat Jaume I, 985-995.

- Pacte (1998): La competencia traductora y su aprendizaje: Objetivos, hipótesis y metodología de un proyecto de investigación. IV Congrés Internacional sobre Traducció. Barcelona: Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona.

- Pacte (2000): Acquiring Translation Competence: Hypotheses and Methodological Problems in a Research Project. In: Allison Beeby, Doris Ensinger and Marisa Presas, eds. Investigating Translation. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 99-106.

- Popham, W. James (1997): What’s Wrong – and What’s Right – with Rubrics. Educational Leadership. 55(2):72-75.

- Popham, W. James (2008): Transformative Assessment. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

- Presas, Marisa (2011): Evaluación y autoevaluación de trabajos de traducción razonada. In: Silvia Roiss, Carlos Fortea Gil, María Ángeles Recio Ariza, et al., eds. En las vertientes de la traducción del/al alemán, Berlin: Frank and Timme, 39-53.

- Presas, Marisa (2012): Training Translators in the European Higher Education Area. A Model for Evaluating Learning Outcomes. The Interpreter and Translator Trainer. 6(2):138-169.

- Rabadán, Rosa and Fernández Nistal, Pilar (2002): La traducción inglés-español: fundamentos, herramientas, aplicaciones. León: Servicio de Publicaciones de la Universidad de León.

- Robinson, Bryan (1998): Traducción transparente: métodos cuantitativos y cualitativos en la evaluación de la traducción. Revista De Enseñanza Universitaria, extraordinary issue, 577-589.

- Robinson, Bryan (2005): Descriptores, distribuciones, desviaciones y fronteras: un planteamiento objetivo ante la evaluación del alumno de traducción mediante exámenes. Sendebar. 16:167-180.

- Rojas Campos, Óscar (2004): El portafolio y la evaluación del proceso en traducción. Letras. 1(36):27-64.

- Toledo Báez, María Cristina (2012): Propuesta de una plantilla de evaluación de traducciones con la competencia traductora como base. In: Pilar Ordóñez López and Tomás Conde, eds. Estudios de traducción e interpretación, Vol. I, Perspectivas transversales, 131-140.

- Tortadès, Àngel (2006): Evaluación de la traducción en un entorno de aprendizaje colaborativo. In: María José Varela Salinas, ed. La evaluación en los estudios de traducción e interpretación. Seville: Bienza, 93-112.

- Van Lawik, Heike and Oster, Ulrike (2006): La evaluación de competencias transversales en la titulación de Traducción e Interpretación. In: María José Varela Salinas, ed. La evaluación en los estudios de traducción e interpretación. Seville: Bienza, 69-92.

- Varela Salinas, María José and Postigo Pinazo, Encarnación (2005): La evaluación en los estudios de traducción. Translation Journal. 9(1).

- Varela Salinas, María José and Postigo Pinazo, Encarnación (2006): La evaluación en los estudios de traducción. In: María José Varela Salinas, ed. La evaluación en los estudios de traducción e interpretación. Seville: Bienza, 113-131.

- Veiga Díaz, María Teresa (2012): Aprender novos métodos para ensinar vellos mesteres: dificultades no deseño dun proxecto de aprendizaxe colaborativa para a aula de tradución científico-técnica. In: Xornada de Innovación Educativa 2012. Vigo: Universidade de Vigo, Área de Innovación Educativa, Vicerreitoría de Alumnado, Docencia e Calidade, 397-404.

- Waddington, Christopher (2000): Estudio comparativo de diferentes métodos de evaluación de traducción general (Inglés-Español). Madrid: Publicaciones de la Universidad Pontificia Comillas.

- Waddington, Christopher (2001): Should translations be assessed holistically or through error analysis? Hermes, Journal of Linguistics. 26:15-37.

- Waddington, Christopher (2003): A positive approach to the assessment of translation errors. In: Ricardo Muñoz Martín, ed. I AIETI. Actas del I Congreso Internacional de la Asociación Ibérica de Estudios de Traducción e Interpretación. Granada, 12-14 de Febrero de 2003. Vol. 2. Granada: AIETI, 409-426.

Liste des tableaux

Table 1

Assessment formats: Questionnaires

Table 2

Assessment formats: Exams

Table 3

Rubrics

Table 4

Example of a rubric to assess the ILO ‘Explain theoretical concepts related to translation’ (adapted from Biggs and Tang 2011: 42)

10.7202/012063ar

10.7202/012063ar