Résumés

Abstract

This paper examines the ebb and flow of organizational power and control during an organizational change where a CEO mobilized narratives to liberate his company from top-down control. The emergent conceptual model makes sense of what appears to be discursive disorder – a cacophony of change narratives. Its contribution is twofold. Firstly, by identifying three ‘narratives in the making’ – the initial, counter and corrective narratives, it elaborates the meso-level narrative mechanisms at the heart of discursive struggles during change and extends Boje’s (2010) triad of narrativity. Secondly, it confirms the utility of the ‘organizational becoming’ and CCO perspectives of organizing for understanding change.

Keywords:

- Narrative,

- organizational change,

- organizational becoming,

- practice,

- liberation management

Résumé

Cet article examine les dynamiques de pouvoir et de contrôle lors d’un changement organisationnel au cours duquel un CEO a recours à la narration pour libérer son entreprise d’un fonctionnement trop rigide. Le modèle conceptuel qui émerge de notre analyse donne un sens à ce qui semble être un trouble discursif - une cacophonie narrative. Notre contribution est double. Tout d’abord, en identifiant trois ‘récits en construction’ – récit initial, contre-récit et récit-correctif, nos résultats mettent en lumière les mécanismes narratifs de niveau méso au coeur des luttes discursives du changement et étendent également la théorie de la triade narrative de Boje (2010). Deuxièmement, nos résultats confirment l’utilité des perspectives des processus organisant permanents et CCO pour la compréhension des changements organisationnels.

Mots-clés :

- Narratifs,

- changement organisationnel,

- organisation en devenir,

- pratiques,

- Libération d’entreprise

Resumen

Este artículo examina la evolución del poder y del control en una organización durante un cambio organizacional, donde un directivo moviliza el uso de la narrativa para liberar a su empresa de control de arriba a abajo. El modelo conceptual que surge da sentido a lo que parece ser, un trastorno discursivo – una cacofonía de las narrativas de cambio. Su contribución es doble. En primer lugar, mediante la identificación de tres ‘narrativas en gestación’- la narrativa inicial, la opuesta y la correctiva; que elaboran los mecanismos narrativos de nivel intermedio, en el corazón de las luchas discursivas durante el cambio y se extiende a Boje (2010) en la tríada de la narrativita. En segundo lugar, se confirma la utilidad de la ‘organización en gestación’ y de las perspectivas del CCO de la organización para comprender el cambio.

Palabras clave:

- Narrativa,

- cambio organizacional,

- práctica,

- gestión de liberación

Corps de l’article

Organizational reality is increasingly viewed as constituted in and through communication (Cooren, Kuhn, Cornelissen & Clark, 2011; Giroux, 1998; Putnam, Nicotera & McPhee, 2008) in ways that are rarely linear and involve struggles of a discursive nature (Thomas & Hardy, 2011; Vaara, 2010). It can be construed as “a collective storytelling system” (Boje, 1991) that is contingent and highly dynamic. This paper takes this proposition as its starting point and applies a narrative perspective (Hardy & Phillips, 2004; Rhodes & Brown, 2005) to examine the ebb and flow of organizational power and control during a change initiative. We draw on a solitary case, with all the benefits and limitations that this incurs, to look behind the apparent disorder and cacophony of narratives that occurs during change to explicate the way change narratives both stabilize and undermine organizing. In so doing, we provide further evidence that the exploration of narratives is necessary to fully appreciate organizational becoming (Brown, 2006; Thomas, Sargent & Hardy, 2011; Tsoukas & Chia, 2002).

We see our contributions to the literature as twofold. Firstly, we identify three different types of ‘narratives in the making’ – initial, counter and corrective - adopted by internal stakeholders as they engage with the change process. Secondly, we use these narratives as the foundation of a model that captures the narrative mechanisms operating at the meso level of discursive struggles that define the change process.

We use the case of TELTEK (not its real name), a call center where the CEO constructed and mobilized narratives to institute ‘liberation management’ (LM) (Peters, 1992; Peters & Bogner, 2002). This philosophy proposes that organizational actors’ contributions to the achievement of corporate goals can be optimized if they are freed from organizational constraints such as rules, procedures, strict role definitions and red tape (Terry, 2005). Successfully communicating a new vision (Kanter, 1984) or grand narrative (Lyotard, 1993) is vital if organizational members are to be empowered to act in accordance with this vision (Arnaud, 2011). Our study addresses how the TELTEK’s CEO used both narrative to initiate, shape, and stabilize new ways of working and thinking across the organization that were consistent with LM. We reveal the narrative actions of both the CEO and his staff to show how the sense they created both ‘liberated’ and constrained the organization.

The paper begins by exploring our current understanding of the relationship between narrativity and organizing. It then describes TELTEK and the nature of its CEO’s liberation management project (LMP). This is followed by a brief explanation of the research design. We then describe and discuss our findings and the emergent conceptual model and show how this fits Hegel’s theory of dialectics (i.e., thesis-antithesis-synthesis). In doing so, we reveal the dynamic and somewhat uneasy interplay between the different sorts of narratives that are woven through the CEO’s innovative liberation management project. Finally, these findings are discussed in terms of the reviewed literature to show how they provide evidence that not only do narratives operate as tactical and strategic tools (Tyler, 2007), they also construct power relations (Boje & Smith, 2010), advance organizational goals (Tyler, 2007) and at the same time challenge this advance by virtue of the cacophony of narratives created. While we accept Vaara’s (2010) proposal that there are multiple levels (i.e., micro, meso, and macro) of organizational discourse, our analysis has been restricted to the often-overlooked meso level where narratives are in the making. This choice of level of analysis is consistent with our aim, which is to expand the focus of studies on organizational becoming (Thomas et al., 2011). Even with this limited focus, the analysis has confirmed that narrativity gives the organization a contested and heterogeneous flavor (Cunliffe, Luhman & Boje, 2004) that is simultaneously an expression of liberation and “hegemonic and subversive” control (Brown, Gabriel & Gherardi, 2009, p. 325). We hope this new example of the installation of liberation management provides an interesting new example of how narratives are integrated into the process of organizational becoming.

Theoretical Background

If we accept that “situations, organizations, and environments are talked into existence” (Weick, Sutcliffe & Obstfeld, 2005, p. 409), then to take a discursive approach to organizing is to portray language, talk, discourse, and communication not simply as reflecting but also as constituting organizational phenomena and actions (Chanal, 2000; Cooren et al., 2011; Putnam & Nicotera, 2008; Robichaud, Giroux & Taylor, 2004). This perspective is referred to as the communication constituting organization (CCO) perspective and has considerable relevance when considering reorganization. This is because changing the way organizing is done is typically a time of “doing things with words” at the micro (Austin, 1962) as well as meso discursive levels as part of a process of instituting a new “Grand Narrative” or “meta-narrative” (Lyotard, 1979) to (re)integrate organizational dimensions.

Scholars who study organizing from a narrative perspective have defined stories and narratives in a variety of ways, sometimes conflating the two. Conversely, there has been a range of ways in which the relationship between narrativity and the organization has been portrayed (Brown et al., 2009; Prichard, Jones & Stablein, 2004; Rhodes & Brown, 2005). A lot of time can be spent trying to reconcile the meaning of stories, narratives and the storytelling or narrativity that produces them. In this regard, we find Brown et al.’s (2009) approach most appealing. They observe:

There are, in particular, no hard and fast rules for distinguishing between stories and narratives or storytelling and narrativisation. Nor is there consensus on how stories and narratives may be distinguished from definitions, proverbs, myths, chronologies and other forms of oral and written texts. …, therefore, we do not devote effort to fruitless definitional exegesis, and refer to stories and narratives interchangeably

Brown et al. 2009: p. 324-325

We are heartened by this acknowledgement of the contested nature of these terms. At the same time, we believe we can make a useful distinction. To us a story becomes a narrative when told. In other words, the process of narration transforms stories into narratives. We ask our participants to turn their storied experience into a narrative through the collaborative process that creates the research interview.

The literature has so far presented this process as a form of retrospection; as a quest to understand what has occurred. The LMP, however, is about creating a new world, a new future (Lyotard, 1979). This means in our research interviews we were interested in TELTEK’s employees’ prospection as well as the retrospection that is associated with making sense of their experiences (Mills, 2005, 2006). Narratives or stories provide a powerful mechanism for framing expectations of the future (Beech, MacPhail & Coupland, 2009; Gergen, 2009; Johansson, 2004; Lyotard, 1979). As such, narratives are intimately implicated in the process of “organizational becoming” (Clegg, Kornberger & Rhodes, 2005; Tsoukas & Chia, 2002). The narrativity that gives rise to meta-narratives that frame the organization’s future ensures communication is inextricably coupled to making change happen (Kanter, 1984). This view of organizational change considers the micro context of communicative action (Thomas et al., 2011) as constitutive of organizing and consequently makes change natural and ongoing as actors engage in sense making actions. If we accept that narratives are “complexes of in-progress stories and story-fragments, which are in a perpetual state of becoming” (Brown, 2006, p. 733), we can start to appreciate the chaotic and polyvocal nature of organizational becoming. If we then consider that organizations are not closed systems but rather interact with their environments, appropriating discursive resources from the environment and weaving them into the in-progress stories and story fragments then the nature of organizing becomes more polyvocal, chaotic and autopoietic (Luhmann, 1986). This is consistent with the view that there is no grand narrative but rather communities of meaning interwoven by a plethora of micro-narratives (Lyotard, 1979). Brown (2006) explains this well, observing:

The result is a fabric that is in a constant state of becoming, unraveling in some areas, embroidered over in others. At times much of the fabric may appear relatively coherent and consistent, as consensus on the meaning of important actions and events dominate, while at other times the fabric may take on a knotted or frayed character as different individuals and groups contest narratively what is truly distinctive or really enduring about their organization.

Brown, 2006, p. 736

This paper is interested in this last kind of contribution to the narrative “fabric”, the one that is suffused with contestation yet leaves no doubt that within all organizations narratives are powerful organizing agents stabilizing organizational process (Arnaud & Mills, 2012; Boje, 1991; Gabriel, 2000; Kopp, Nikolovska, Desiderio & Guterman, 2011), providing devices for knowledge sharing and meaning making (Birch, 2000; Chesley & Wenger, 1999), expressing affect (Mills, 2006) and operating as tools for achieving managerial objectives (Bray, Lee, Smith & Yorks, 2000) such as organizational change (Doolin, 2003). Indeed, recent literature establishes narratives and storytelling as tactical and strategic tools (Boje, 2008; Vaara & Reff Pedersen, 2013). According to Tyler (2007), narratives advance organizational goals through the way they are embodied in all manner of official actions and associated texts including those operating at the meso organizational level (e.g., in general meetings, organizational chart, principles, rules, procedures, technologies, and websites) (Boje & Smith, 2010). At the micro level, narratives engage with the rhetorical activity at the center of organizational strategizing (Jarzabkowski & Seidl, 2008) and more informal encounters such as everyday discussions (Samra-Fredericks, 2003).

Research at the meso discursive levels has tended to focus on managerial use of narratives but managerial narrativity is only part of the story. Managers’ narratives needs to be understood alongside the alternative and even antagonistic representations created by other organizational stakeholders (Boje, Luhman & Baack, 1999; Tyler, 2007) as no one party has control over an organization’s discursive space. This means it is important to understand the process through which reluctant and discordant narratives arise, particularly among non-managerial staff, and how they can be managed if we are to understand how power relations are expressed and operate (Boje & Smith, 2010; Hardy & Phillips, 2004), creating discursive struggles (Vaara, 2010) and confirming organizations as “sites of hegemonic struggles” Brown (2006, p. 733). Following Vaara’s (2010) claim, this paper aims to advance our knowledge about such struggles.

The discourse literature has been largely focused on how discursive practice produce collections of discursive texts that shape and fix power relations at a particular moment (Hardy & Phillips, 2004; Rhodes & Brown, 2005). Over time, these states of power evolve as a consequence of the discursive struggles between some stakeholders. As such, our understanding of the power dynamic has to incorporate both power and resistance over time in order to explain the way organizational change (Beech et al., 2009; Thomas & Hardy, 2011) is mediated by discourse: “discourse shapes relations of power while relations power shape who influence discourse over time and in what way” (Hardy and Phillips, 2004, p. 299).

Narratives, as a dynamic discursive form, can be understood, “as sites of hegemonic struggle” (2006, p. 733) so, according to Rhodes and Brown (2005, p. 173), “Studying power from a narrative perspective enables it to be understood as a dynamic phenomenon, the form and enactment of which is subject to change over time.” The narratives at the heart of this perspective can take many forms. Boje & Smith (2010) proposes a triadic model of storytelling that incorporates three genres of narratives and incorporates consideration of the temporality of narrative processes. These three genres are (1) narratives that are retrospective and secure or “fossilize” the past, (2) living stories that are constantly unfolding in the never ending present and (3) antenarratives that are hypotheses or pre-stories that operate as “bets on the future”. They propose the interaction between these retro-, now- and prospective narratives explains the dynamic and agential nature of storytelling but also the way multivocal and networked living stories become stable and univocal (Boje & Smith, 2010).

Vaara (2010, p. 30), who asserts the full potential of the linguistic turn for organization studies has not yet been realized, argues for a “multifaceted interdiscursive approach” to the study of organizing. At the meta level, he proposes researchers need to “focus attention on struggle over competing conceptions of strategy”, in terms of where a company should go and its required organization. At the meso level, Vaara argues for an examination of “alternative strategy narratives to better understand the polyphony and dialogicality” of organization. Finally, at the micro level, he claims (Vaara, 2010, p. 31) it can be “useful to reflect on rhetorical tactics and skills situated in conversation to promote or resist a specific view”. Figure 1 schematically represents these three levels of discourse and the way they inform each other.

FIGURE 1

Multiple Levels of Discourse (based on Vaara 2010)

During change processes, organizing and organizations become more ambiguous and uncertain places (Weick, 1995). They become precarious phenomena (Cooren et al., 2011) as the sensemaking at interfaces between stakeholders becomes more challenging and their discourses become more diverse and require even more coordination. This is especially true when introducing unfamiliar and radical initiatives such as “liberation management” (Peters, 1992; Terry, 2005), which entails freeing stakeholders from existing organizational constraints. Existing ways of talking and making sense get challenged and possibly displaced. The result is that stakeholder interfaces become both more ambiguous and challenging and at the same time important sites where new ways of organizing are negotiated. At the heart of how stakeholders make sense of these interfaces will be narratives, which are inevitably part of how people make sensible their experience (Weick, 1995).

Our study examined how narrativity operated across stakeholder interfaces during the implementation of a “liberation management” (LM) initiative. In particular, we sought to establish how context interacted with narratives to shape and stabilize the sensemaking at organizational interfaces. To do this we examined how sense was embodied in stories produced by the CEO and other TELTEK internal stakeholders.

A Case of Liberation Management: TELTEK

TELTEK (not the actual name) is a medium size Call Center company of 370 employees with an 18 million EURO annual turnover. It is an autonomous subsidiary of a larger group of companies. The CEO describes the company’s mission as providing the other companies in the group with after-sales services and customer relationships services (e.g., help desk, car failure diagnostics for garages, juridical assistance). Employees are chosen with skills to match the primary service delivered by each department. For example, all those working in the department supporting garages are qualified car repair technicians with previous job experience working in a garage whereas the IT technicians are answering the IT helpdesk hotline. Each department represents a kind of mini-company with its own managerial approach. This means that processes, work schedule flexibility, and team management vary among departments.

The call centre industry is challenging as margins are low due to international competition. Much of France’s call-center activity is now serviced offshore. In order to stay competitive, the TELTEK CEO has focused on providing new added-value services to clients and, in so doing, staying ahead of the competition. The “Liberation Management Project” (LMP) to “free” TELTEK is part of his strategy to achieve this objective. He hopes LMP, by freeing the organization from current routines, will facilitate ongoing innovation and establish a competitive advantage from the frontline upwards. This has important implications in the context of a call center where traditionally organizing is very much top-down and even neo-Taylorian, and where processes and roles are strictly defined (Boutet, 2005; Calderón, 2005; Linhart, 2010).

Method

TELTEK is presented here as a single empirical case study (Yin, 2009). It is based on thirty three interviews plus general assembly videos and observation, two focus groups and document (e.g., reports, minutes, internal memos, newsletters, PowerPoint and Prezi presentations, charts, and videos) collected from October 2102 to February 2013. CEO, senior managers, middle managers, front line employees and support staff were asked both to narrate their experience of the LMP over the last 12 months and their expectations about the future of the LMP. To resultant narratives allowed us to reconstruct what happened within TELTEK over the previous months and identify three narrative plots. The initial, counter and corrective narratives we identified provided a temporal map of the implementation of the LMP, illustrating Ricoeur’s (1988) notion of cosmological time.

The interviews were collected in three stages. First, we conducted two interviews with the CEO in order to appreciate both the origins and motivation of LMP, and its empirical implementation within TELTEK. These interviews also helped us to begin identifying narratives that subsequently we triangulated with managers’ and employees’ interviews to identify the initial sensegiving narrative. Secondly, we interviewed senior managers in order to appreciate how much they were sharing the initial narrative of LMP but also to identify any counter narratives. These were subsequently confirmed by comparing them with data from interviews with employees. Finally, we conducted a third interview with the CEO and the two focus groups and attended the annual TELTEK meeting in order to collect data that helped us constituting the corrective narratives. At this point, we also identified that senior managers were now sharing the CEO’s corrective narratives which appeared to be giving them more impact.

Further data were gathered from a video of the CEO’s speech and Prezi presentation during the “launch” general meeting prior to researchers entering the field (October 2012) and three interviews (Total of 8 hours of interviews) with the CEO (between October and December 2012). These data provided the bulk of the data that allowed the initial LM (liberation management) narratives to be identified. Interviews with TELTEK employees (from October 2012 to December 2012) provided addition narratives including the counter narratives. Participants for these interviews were recruited from across all organizational positions (including elected staff representatives and a union representative). This ensured the interfaces between the employees at different levels, within departments and professional groups were examined (Eisenhardt & Graebner, 2007). Executive committee members were also interviewed. In total 40 hours of recorded conversation was collected.

In addition, we attended the “update” general meeting at the end of February 2013 that sought to inform employees about LM initiative progress in TELTEK. On that occasion the various speeches were recorded. The data collected during this “LM update” event were sources of the CEO and official counter-narratives. Following that event, two focus group interviews were held with operational-level staff and middle managers respectively to explore the similarities and differences in the stories around the LMP that had emerged in the individual interviews, and following the “update” general meeting.

All instances of recorded conversation including meetings were transcribed. The narrative data were then coded in a manner inspired by the constant comparison technique described in the Grounded Theory Approach (Glaser & Strauss, 1967). Our iterative technique ensured data were coded using codes that emerge from the data rather than a pre-emptive conceptual framework. These codes then provided the foundation for categories that were combined to create a conceptual framework that embraced all data. This analysis revealed a system of narratives incorporating initial narratives, counter narratives and corrective narratives. Thus, our unit of analysis was narrative rather than interaction (Osman & Mounoud, 2006). As noted earlier in this paper, we appreciate that the term narrative is contested and agree with Brown et al. (2009) that there is a degree of futility in trying to tightly define it. We therefore chose to define narrative broadly as language that recounted, explained, questioned or proposed events, actions and circumstances associated with the introduction of the LMP.

Narratives as Tools of the LMP Implementation

The data collection spanned the period from the ‘LM launch’ event to immediate following of the ‘LM update’ event. Various narratives representing different aspects of the LMP were identified and analyzed. Inspired by Vaara’s (2010) advocacy for a “multifaceted interdiscursive approach” to the study of organizing, we looked at how the micro (interaction / conversation), meso (narratives) and macro level (organizational discourse) interacted. In this paper we have chosen to focus on the meso level as our data were particularly rich at this level. At this level we were able to distinguish narratives that served different functions in relation to the advancement of the LMP. These were labeled sensegiving narratives, counter narratives and corrective narratives (see Table 1). In column one excerpts from sensegiving narratives that were an integral part of the CEO’s launch process for the LMP are presented. In column two excerpts from contradictory narratives that resulted in response to the primary sensegiving narratives are displayed. In column three, excerpts from of the corrective narratives formulated by the CEO and his team in reaction to the contradictory or counter narratives are presented. Together, the narratives from which these excerpts were drawn contributed to a dynamic process of proactive and reactive sensegiving that was linked to employees’ sensemaking. These narratives introduced and then supported or defended the implementation of the LMP. The finding the CEO and his team had to take action to sustain the initial change proposal illustrates how change is a contested process that occurs at the interface between advocacy and reaction. Table 1 contains excerpts from the interviews that provide insights into this dynamic interaction between narratives and sensegiving and sensemaking.

Several of the CEO’s narratives (meso level) promoting the LMP (i.e., sensegiving) were identified as drawing on a ‘Grand narrative of liberation’. We chose to study the four narratives that were most strongly linked to this grand (macro level) narrative. These four meso narratives were labeled as Liberating in order to survive, Freeing Teltek employees, Fostering innovation and Being transparent to capture the main thesis of each one. These CEO-sourced narratives were intended to be sensegiving and as such introduce and support the implementation of the LMP. They acted as strategic tools because they were deliberately employed to introduce a future that played out in the employees’ workplace practice.

Liberating in order to survive. The CEO’s narrative that captured the LMP purpose centered on the essential truth as he saw it – that staff needed to be liberated in order to work in ways that would make the company competitive. It was a very powerful narrative in terms of the sense it was designed to communicate to staff. He used it to say, “We don’t have any choice about changing in this way; it is a matter of survival”. In this way he framed the LM project as a matter of life or death (a rhetorical tactic – micro level). Such messages carry a strong and clear strategic intent and do not provide much latitude for misinterpretation. Even so, our interviews with his employees revealed that his declared sensegiving intent was not always realized. Counter narratives (meso level) emerged that captured resistance, cynicism and unwillingness by some to accept the basic premise upon which the CEO’s narrative was based – that staff free from constraining institutional structures can make a difference to the productivity of a company and so freeing them is a good thing to do.

Freeing TELTEK employees. This basic premise was most clearly evident in the freeing ‘TELTEK employees” narrative. The CEO used this to advocate for empowering the front line workers. The narrative proposed that, “Everyone is now empowered to make decision about what they do and how they do it” (CEO). This then provided a basis for questioning the legitimacy of support functions. The CEO asked, “Do we still need support functions?” in a liberated workplace. In this and other ways his rhetorical tactics supported a narrative proposing new alternatives for organizing work. The new reality was presented in terms of new processes, roles, and scopes of responsibility and changed support activities. Thus, his sensegiving narrative was about a new future rather than an account that secured the past. It was prospective rather than retrospective and so deviated from how we most commonly encounter narratives (Boje, 2011). This finding builds on Boje’s (2010) triadic model of storytelling, highlighting the centrality of antenarrative, Boje’s prospective genre of storytelling, during a strategic organization change process.

Table 1

Illustrating Narrative Dynamics and the Resolution of Discursive Tensions

Fostering innovation. The CEO’s ‘fostering innovation’ narrative was process oriented. Unlike the ‘Freeing TELTEK employees’ which provided justification for his LMP by painting the picture of a new world where innovation was possible, this ‘Freeing TELTEK employees’ narrative looked at the processes involved in liberation, specifically what liberation in action would mean in behavioral terms. One comment captured this behavioral orientation: “After only eight months there are already lots of achievements. It’s great to see that. We are … they are moving!”.

Being transparent. The CEO’s narrative ‘Being transparent’ communicated his strong belief in giving all employees equal access to information. He commented that, “Everyone in TELTEK now has access to financial information”, and “We are completely transparent”. Such rhetoric (micro level discourse) were consistent with his initial narrative that addressed the laudability of the LMP by narrating the changes in transparency that are both necessitated and a consequence of the change process. In this narrative, transparency was cast as a morally defensible requirement of contemporary management.

The CEO’s initial sensegiving narratives presenting and promoting LM were confronted with contradictory or counter narratives created by employees. These counter narratives addressed aspects of what the CEO said that challenged employees’ expectations about work. They also addressed and reframed the CEO’s motives where they were perceived as inconsistent with their knowledge of him. Collectively, the counter narrative action undermined the smooth emergence of the new liberated organization by causing resistance to or confusion about the redefinition of rules, identities and power relations between stakeholders. Our data analysis revealed that many employees’ LMP narratives specifically addressed the narratives the CEO used to launch the project. The following sections illustrate how the CEO’s initial sensegiving narrative action was ‘countered’.

Responses to ‘Liberating in order to survive’. Different interpretations of the LMP’s initial narrative were expressed in counter narratives that assigned different meanings to the CEO’s intent. Comments such as “it is an ego trip” (operational employee) and “this is like an inside joke…” (support team manager) illustrate the sort of rhetoric (micro level discourse) that contributed to the tone of the antagonistic counter narrative environment that developed. The counter narrative action that integrated such comments brought into question the plausibility of the CEO’s proposition that LMP was a pathway to survival. At the same time it fostered the emergence of confusion and resistance.

Responses to ‘Freeing TELTEK employees’. Numerous counter narratives emerged reflecting the gap that employees perceive between their own situation and what the CEO was proposing. For example, instead of focusing on freedom to take appropriate survival action (as in the CEO’s narrative), some frontline (operational) employees focused on the need for control in order to survive. This is captured in the following excerpt: “This liberation management thing, I love the idea, but this is not my company. My day to day activities are about control, not freedom.” (operational employee).

It was clear that roles and identities were shaken by the counter narrative action that included claims an unsavoury future was inevitable. One worker asked, “What am I going to become? According to what they (CEO) say, there will be no need for managers anymore…”. The freedom proposed by the CEO’s narrative advocating LM as the way forward was reframed in the counter narratives as destabilizing or threatening. One worker captured this by saying, “We don’t know where we are going, there is no destination…. It is scary.” (support employee).

Responses to ‘Fostering innovation’. In response to the CEO’s narrative promoting progress through the implementation of the LM project accompanied by individual and collective recognition, counter narratives emerged founded on expectations of difficulties and failures. One worker noted, “This requires skills that everybody hasn’t got!” (VP Methods and Quality). Another addressed the apparent lack of rewards in the new LM era by complaining: “I came with a new concept developed in my own time. But I didn’t get any reward in terms of evolution or salary. I’m done with it (LM)!” (Operational employee).

Responses to ‘Being transparent’. In the face of the strong transparency narrative of the CEO, counter narratives emerged that stressed the prevalence of misinformation. One worker noted: “They are manipulating us. Who can tell they are not giving us the real information?!” (operational employee). For several other employees the LM project was seen as a major attempt by management to manipulate them – “We are pawns rather than players” narrative. This counter narrative and the perceptions embedded within it fueled questions about the CEO and his team’s commitment to transparency and was used to justify a lack of trust for management.

Corrective Narrative Action

The response to the CEO-sourced sensegiving narratives was unprecedented counter narrativity that provided clear evidence of the tensions that were emerging at key intra-organizational interfaces. Differences between the sensegiving narratives of the CEO and supporters of LMP and the sensemaking narratives of other stakeholders created an environment characterized by cynicism, frustration, fear, and self-interest. The organization that was emerging in the face of the LMP was characterized by more discursive struggles and confusion than that which existed prior to the start of the LMP. It had less stable stakeholder interfaces and, ironically, was less sure of its ability to innovate. For instance, some employees who were happy with the previous organization became frustrated by or afraid of what the future held for them. They narrated stories that wove together events that suggested order and predictability had been replaced with a new disorder and dissatisfaction.

Such was the discontent that the CEO, now supported by all the top team members, was confronted by counter narratives on a daily basis. This prompted corrective narrative action. Thus, a new wave of sensegiving occurred as the CEO and senior managers adjusted existing narratives, introducing new narratives to confront and neutralize or accommodate the counter narratives. In so doing, another layer of strategic sensegiving narrative action emerged. These corrective action narratives took different forms, but essentially could be classified according to whether they reinforced or revised the initial sensegiving narratives. The following sections give examples of narrative action designed to counter challenges to the original narratives that launched the LMP.

Advancing the “Liberating in order to survive narrative’ in the face of counter narrativity. The CEO and top managers corrective narratives that were used to answer the counter narratives questioning the LMP purpose, reinforce the primary sensegiving narrative, with the emphasis on the evidences/proofs that reflect the compulsory and essential dimension of the LMP for TELTEK “Margins are reducing and budget objectives are not met. We need to find solutions together” (CEO); “Price negotiations on CRS (customer relationship services) are harder than ever and margins are low” (VP Business development).

Advancing ‘Freeing TELTEK employees’ in the face of counter narrativity. The notion of liberation did not sit well with many workers so it was hardly surprising that much of the workers narrative action conveyed cynicism about the CEO’s objective to liberating them. The CEO’s response to such narrative action was to engage in retelling the liberation narrative using new terms. He adjusted the narrative so it no longer referred to the path of liberation and instead involved a path of trust. This is captured in the following narrative element: “We are entering a new phase, the ‘path of trust’” (CEO).

The LMP project was reframed as now being about trust. Furthermore, the CEO and his team addressed the perception that the LMP was not going well and that there was no consistency about its implementation by coupling ‘the path of trust’ to the notions of multiple pathways and the availability of support as workers moved along their particular pathways towards liberation. The following narrative excerpts show how the CEO and senior managers presented these new framings: “Support functions are important. They are rethinking their roles to accompany and facilitate the journey” (CEO). “We are here to support your ideas.” (VP Methods and Quality). “Our role is to help you give meaning to numbers.” (Accounting manager). “There is no pre-defined destination or method for LM, and we are finding our way along all together.” (CEO). “Each department accordingly to its own constraints is making progress on the path of trust” (CEO).

Advancing ‘Fostering innovation’ in the face of counter narrativity. The Workers were confronted with evidence that the LMP was creating undesirable effects and narrated instances of service failures and interpersonal tensions which were at times woven into substantial ‘not fostering innovation’ narratives. The CEO and his team confronted these counter narratives by acknowledging the problems and reframing them from being signs of failure to being evidence of innovation. Innovation, they proposed inevitably brings mishaps and misadventures. The following excerpt from a ‘LMP update event’ captures this corrective sensegiving activity: “Several departments are developing new services and products. Lots of trials, errors and some success, and that naturally goes along with innovation” (CEO); “Innovation is like nature. Seeds are planted, some start to grow and die, some develop into baby plants, fewer reach the stage of young plants, and fewer produce flowers… it is all about innovation” (VP Methods and Quality).

Other corrective narratives from the CEO addressed individual complaints about lack of rewards. Such complaints were used by workers to illustrate how the LMP was not fostering innovation but merely extracting more work from workers without additional payment. The CEO’s narrative action served to show that there are indeed rewards for individuals that created a successful innovation. The following excerpt shows how this was done: “Danny who developed the idea of a juridical data base with paid access is now evolving to project manager, and is in charge to implement this new product” (CEO).

Advancing ‘Being transparent’ in the face of counter narrativity. The CEO’s corrective narrative action answered counter narratives, suggesting all was not as the CEO and his team originally portrayed the LMP. The symbolic act of removing all managers’ office doors was used to materialize the corrective narrative that insisted transparency was an integral part of liberation. The following is a narrative element from a ‘LMP update event’ that captures this corrective action: “There is no withholding of information. All managers including me have had their office door removed. Only doors of meeting rooms are still in place for noise reduction purposes in the platforms” (CEO). Such corrective narrative action, reinforced the liberation message and showed how the CEO and his team were adapting to the ‘not transparent’ narratives they heard around the company.

Our analysis reveals how patterns of narrative action were hidden beneath the apparent disorder and polyphony of different stakeholders’ narratives and combined to create a dynamic sensegiving and sensemaking process to support a process of organizational becoming. Two distinctive types of CEO sensegiving narrativity were identified – the proactive sensegiving that launched the LMP and then the corrective narratives, either reinforcing initial sensegiving narratives or adjusting these, that were prompted by counter narratives created by employees who took issue with some aspect of the initial sensegiving narratives. This narrative system incorporated retrospective, now-spective and prospective dimensions to provide a temporal dimension that located the organizational becoming process and the meaning making associated with it in time and space.

Discussion

Our study looked at how TELTEK’s CEO uses narrativity to shape and stabilize the sensemaking at intra-organizational interfaces during a change initiative. We show how the sense embodied in the narratives he and other actors produced both ‘liberated’ and constrained the organization by virtue of the interplay created between the sensegiving, counter and corrective narratives that were produced. The main contribution of this empirical research is the model that captures this narrative mechanism. In doing so, it confirms the existence of multiple micro narratives (Lyotard, 1979) and advances Boje’s (2011) triadic model of storytelling by positioning prospective narrativity during change as integral to strategic change. This is a significant contribution that hopefully will encourage scholars to give greater importance to storytelling as a central aspect of sensegiving during change.

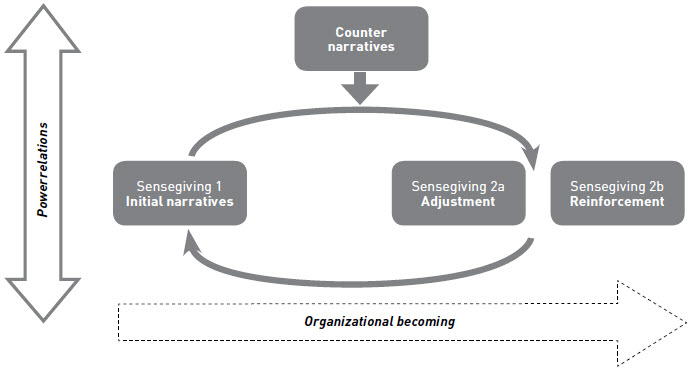

Our conceptual model makes sense of the apparent disorder and polyphony of the narrativity during change and provides the basis for two further contributions to the literature. Firstly, by clearly identifying the interplay between three different patterns of ‘narratives in the making’ – the initial, counter and corrective narratives – adopted by internal stakeholders as they engage with the liberation management project, we reveal a previously unidentified narrative mechanism that lies at the meso level of discursive struggles during change. Secondly, by virtue of the way our model elaborates upon the role communication plays in change implementation and organizational context (re)definition, we provide an empirically-based model that links the CCO perspective (Chanal, 2000; Cooren et al., 2011; Putnam & Nicotera, 2008; Robichaud et al., 2004) to the organizational becoming (Clegg et al., 2005; Tsoukas & Chia, 2002) literature. In so doing, we are hopeful that our model of change narrativity will not only provide a framework to further our own research (Figure 2) but also one that could be usefully employed by others seeking to advance our understanding of the power of strategic storytelling during change.

Discursive struggles as embodiment of power relations

Narratives that originate from the top echelons of the organization were often confronted with alternative versions, particularly during change when internal stakeholders are reluctant to accept the changes entangled within these sensegiving narratives. The counter narratives produced gave substance to the power relations (Boje & Smith, 2010; Hardy & Phillips, 2004) within the organization and were at the heart of the discursive struggles that ensued (Vaara, 2010). Paradoxically, the CEO attempted to use narrativity as the primary sensegiving tool, to instigate a ‘new organizational order’ and way of operating (i.e., LM) characterized by a flatter power distribution. His narrative action, rather than creating a single grand narrative (Lyotard, 1979), at the organizational level created varying levels of shared understanding and commitment to this new way of organizing called liberation management. Counter narratives emerged at all levels in the organization in response to the CEO’s strategic sensegiving. Rather than creating a new monophonic order, heightened polyphony was evident within the organization accompanied by uncertainty, confusion, cynicism and fear. The “natural behavior context” (Boje, 1991, p. 109) of storytelling was disrupted and a more precarious organization (Cooren et al., 2011) began emerging. The CEO used corrective narratives to either reinforce or adapt the original sensegiving narratives advocating for LM and the LMP (See figure 2) in the face of this emerging precariousness. This corrective narrativity was clear evidence that the CEO and his team were sensitive to the changing discursive landscape accompanying their innovation project (i.e., LMP), and that the sociopolitical context and emerging communities of meaning (Lyotard, 1979) could not be ignored.

Taken together, the findings from our exploration of the narratives associated with the TELTEK CEO’s attempt to liberate his organization in order to facilitate innovation reveal a collective but complicated storytelling system (Boje, 1991) comprised of intersecting and conflicting levels of narrative and counter narrative.

FIGURE 2

Model of Narrativity during Change

Beech et al. (2009) found that although storytelling can have the appearance of dialogue, this is not actually the case as each party’s narratives are self-contained with the narrators not collaborating in the narration of the others’ stories. Our findings suggest otherwise. Where Beech et al. (2009) concluded that narratives can be seen as anti-dialogic, promoting ‘”fantasized images of the other”, as captured in Figure 2, in some aspects our findings show the opposite. In particular, the corrective narratives are evidence the CEO and his team listened to and took account of the workers’ counter narratives rather than persisting with the sensegiving narratives that launched the project. This suggests a system where narratives engage with others and are characterized by reaction, refinement and re-narration that is never finished.

Organizational Becoming as Discursive Struggles

This emerging model captures the prominence of meso level discursive struggles (Brown, 2006; Vaara, 2010) that were at the heart of workers experience of the process of change created by the LMP while acknowledging that these must be seen within the context of macro and micro discursive processes. It shows how, from both a process and temporal perspective, polyphony constitutes a necessary step that has to be navigated before some degree of narrative consensus around an innovation can emerge and a new form of organizing can be reach (van Hulst, 2012). Our findings suggest that corrective narrative strategies play an important role in change management as they can be used as sensegiving tools to encourage convergence between disparate narratives. Figure 2 captures the narrative process exposed by our study. The layers span Vaara’s (2010) levels of discourse but we have focused on the meso level where stories materialize through narratives exchanges because we found considerable evidence that the narrativity at this level was at the heart of the conflict associated with the LMP. Not only did narratives provided the CEO and his team with the vehicle for primary sensegiving (i.e, proactive sensegiving) about the LMP, they prompted counter narrative action from within this team and the workforce as a whole that subsequently stimulated corrective sensegiving narrative action from the CEO. It is the elucidation of these narrative dynamics at the meso level that is the primary contribution of this paper. These dynamics suggest that organizational becoming is not only constituted by macro and micro communication action (Thomas et al., 2011) but also by the meso communication action created as shared and competing narratives, both sensegiving (e.g., the CEO’s corrective narratives) and compliant or resistant sensemaking narratives (e.g., frontline staff’s counter narratives) engage with each other to create the lived-in experience of organizational change.

Conclusion

Our analyses reveal that the introduction of an innovation such as the LMP does not install an organizational grand narrative (Lyotard, 1979) but rather generates layers of intersecting sensegiving and sensemaking narratives that engage with each other to give the organization a contested and heterogeneous flavor (Cunliffe et al. 2004) while simultaneously providing expressions of liberation and “hegemonic and subversive” control (Brown et al. 2009, p. 325). Our model captures how change generates different types of narrative action, sensegiving, counter and corrective narratives, which are variously retrospective, now-spective and prospective in nature. It accounts for the way a change initiator (In our case the CEO and his team) must take corrective narrative action to address the challenges posed to the change process by counter narratives. Our model captures this dynamic ‘poly-narrative’ essence of change and links it to the process of organizational becoming (Clegg et al., 2005; Tsoukas & Chia, 2002) and the CCO perspective (Chanal, 2000; Cooren et al., 2011; Putnam & Nicotera, 2008; Robichaud et al., 2004) but further analysis is indicated to fully reveal how the macro and micro narrative processes were integrated into our essentially meso level organizational analysis. Even so, we are optimistic that this narrative representation of change that incorporates the temporal dimension of narrativity by building on Boje’s (2010) triadic model of storytelling is promising. It provides a framework for further research into organizational becoming that recognizes the complexities of organizational narrativity and the centrality of narrativity to the enactment of organizational change.

Parties annexes

Biographical notes

Nicolas Arnaud, HDR, is Associate Professor in the Department Management Organisation & Law and hold the position of Deputy Director of Audencia Grande Ecole at Audencia, School of Management. His research interests include collective skill and middle managers practices from a communication perspective. His works have been published in various journals including Group & Organization Management, International Management, Finance Contrôle Strategie, Revue Française de Gestion, Gérer et Comprendre. He also recently published an organizational communication textbook.

Colleen E. Mills is an Associate Professor in the Management Department at the University of Canterbury. Her research examines organizational processes, particularly during times of uncertainty and change. Her research, which has produced models of sense making about communication during change and organisational gossip, is published in various journals including Group and Organization Management, International Small Business Journal, International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour and Research, Journal of Business Communication, Australian Journal of Communication, Journal of Managerial Psychology and Education + Training. She serves on several Editorial Boards including Group and Organization Management and Communication Research and Practice.

Céline Legrand is Associate Professor at Audencia School of Management and Joint-Head of the Management Organization and Law Department. Her research interests include CEOs, top management groups and managers practices. Her research work has been published in Management International, Revue Interdisciplinaire sur le Management l’Humanisme et l’Entreprise, Revue Gestion.

Bibliography

- Arnaud, N. (2011). “Du monologue au dialogue. Étude de la transformation communicationnelle d’une organisation”, Revue française de gestion, 210(37), 15-31.

- Arnaud, N.; Mills, C. E. (2012). “Understanding the inter-organizational agency: A communication perspective”, Group & Organization Management, 37(4), 452-485.

- Austin, J. L. (1962). How to to things with words, Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Beech, N.; MacPhail, S. A.; Coupland, C. (2009). “Anti-dialogic positioning in change stories: Bank robbers, saviours and peons”, Organization, 16(3), 335-352.

- Birch, C. L. (2000). The whole story handbook: Using imagery to complete the story experience, Little Rock, AR: August House.

- Boje, D. M. (1991). “The storytelling organization: A study of story performance in an office-supply firm”, Administrative Science Quarterly, 36(1), 106-126.

- Boje, D. M. (2008). Storytelling organizations, London: Sage.

- Boje, D. M. (2011). Storytelling and the future of organizations: An antenarrative handbook, New York, NY: Routledge.

- Boje, D. M.; Luhman, J. T.; Baack, D. E. (1999). “Hegemonic stories and encounters between storytelling organizations”, Journal of Management Inquiry, 8(4), 340-360.

- Boje, D. M.; Smith, R. (2010). “Re-storying and visualizing the changing entrepreneurial identities of Bill Gates and Richard Branson”, Culture & Organization, 16(4), 307-331.

- Boutet, J. (2005). “Au coeur de la nouvelle économie, l’activité langagière”, Sociolinguistica, 13-21.

- Bray, J.; Lee; J., Smith, L.; Yorks, L. (2000). Collaborative inquiry in practice, Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Brown, A. D. (2006). “A Narrative Approach to Collective Identities”, Journal of Management Studies, 43(4), 731-753.

- Brown, A. D.; Gabriel, Y.; Gherardi, S. (2009). “Storytelling and change: an unfolding story”, Organization, 16(3), 323-333.

- Calderón, J. A. (2005). “L’implication quotidienne dans un centre d’appels: les nouvelles “initiatives éducatives””, Travailler(1), 75-94.

- Chanal, V. (2000). “Langage, changement organisationnel et gestion de l’innovation”, Management International, 4(2), 29-39.

- Chesley, J. A.; Wenger, M. S. (1999). “Transforming an organization: using models to foster a strategic conversation”, California Management Review, 41(3), 54-73.

- Clegg, S. R.; Kornberger, M.; Rhodes, C. (2005). “Learning/Becoming/Organizing”, Organization, 12(2), 147-167.

- Cooren, F.; Kuhn, T.; Cornelissen, J. P.; Clark, T. (2011). “Communication, organizing and organization: An overview and introduction to the special issue”, Organization Studies, 32(9), 1149-1170.

- Cunliffe, A. L.; Luhman, J. T.; Boje, D. M. (2004). “Narrative Temporality: Implications for Organizational Research”, Organization Studies, 25(2), 261-286.

- Doolin, B. (2003). “Narratives of change: Discourse, technology and organization”, Organzation, 10(4), 751-770.

- Eisenhardt, K. M.; Graebner, M. E. (2007). “Theory Building from Cases: Opportunities and Challenges”, Academy of Management Journal, 50(1), 25-32.

- Gabriel, Y. (2000). Storytelling in organizations: Facts, fictions, and fantasies, New York: Oxford University Press.

- Gergen, K. J. (2009). An invitation to social construction (2nd ed.), London: Sage.

- Giroux, N. (1998). “La communication dans la mise en oeuvre du changement”, Management international, 3(1), 1-14.

- Glaser, B. G.; Strauss, A. L. (1967). “The theory of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research”, New York: Aldine de Gruyter.

- Hardy, C.; Phillips, N. (2004). “Discourse and power”, in D. Grant, C. Hardy, C. Oswick, N. Philipps and L. Putnam (Eds.), The Sage handbook of organizational discourse (pp. 299–316).

- Jarzabkowski, P.; Seidl, D. (2008). “The Role of Meetings in the Social Practice of Strategy”, Organization Studies, 29, 1391-1426.

- Johansson, A. W. (2004). “Narrating the entrepreneur”, International Small Business Journal, 22(3), 273-293.

- Kanter, R. M. (1984). Change masters, New-York: Simon and Schuster.

- Kopp, D. M.; Nikolovska, I.; Desiderio, K. P.; Guterman, J. T. (2011). “’Relaaax, I remember the recession in the early 1980s...’: Organizational storytelling as a crisis management tool”, Human Resource Development Quarterly, 22(3), 373-385.

- Linhart, D. (2010). La modernisation des entreprises, Paris: La découverte.

- Luhmann, N. (1986). “The autopoiesis of social systems”, in F. Geyer and J. Zouwen (van der) (Eds.), Sociocybernetic paradoxes: Observation, control and evolution of self-steering systems (pp. 172-192), London: Sage.

- Lyotard, J.-F. (1979). “La condition postmoderne: rapport sur le savoir”, Paris: Éditions de Minuit.

- Lyotard, J.-F. (1993). “Excerpts from The postmodern condition: A report on knowledge”, in J. Natoli and L. Hutcheon (Eds.), A postmodern reade (pp. 71-90), New-York: Suny Press.

- Mills, C. E. (2005). “Moving forward by looking back: a model for making sense of organisational communication”, Australian Journal of Communication, 32(2), 19-43.

- Mills, C. E. (2006). “Modelling sensemaking about communication: how affect and intellect combine”, Southern Review: Communication, Politics & Culture, 38(2), 9.

- Osman, L. C. B.; Mounoud, E. (2006). “Action organisationnelle et isomorphisme institutionnel: Une grande banque française face à Internet”, Management International, 10(3), 35-48.

- Peters, T. (1992). Liberation management: Necessary disorganization for the nanosecond nineties, New York: Fawcett Columbin.

- Peters, T.; Bogner, W. C. (2002). “Tom Peters on the Real World of Business”, The Academy of Management Executive (1993-2005), 40-44.

- Prichard, C.; Jones, D.; Stablein, R. (2004). “Doing research in organizational discourse: the importance of researcher context”, in D. Grant, C. Hardy, C. Oswick and L. L. Putnam (Eds.), The Sage handbook of organizational discourse (pp. 213-236), Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Putnam, L. L.; Nicotera, A. M. (Eds.). (2008). Building theories of organizing: The constitutive role of communication, New York: Roultedge.

- Putnam, L. L.; Nicotera, A. M.; McPhee, R. D. (2008). “Communication Constitutes Organization”, in L. L. Putnam and A. M. Nicotera (Eds.), Building theories of organizing: The constitutive role of communication (pp. 1-20), New York: Routledge.

- Rhodes, C.; Brown, A. D. (2005). “Narrative, organizations and research”, International Journal of Management Reviews, 7(3), 167-188.

- Ricoeur, P. (1988). Time and narrative., Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Robichaud, D.; Giroux, H.; Taylor, J. R. (2004). “The metaconversation: The recursive property of language as a key to organizing”, Academy of Management Review, 617-634.

- Samra-Fredericks, D. (2003). “Strategizing as Lived Experience and Strategists’ Everyday Efforts to Shape Strategic Direction”, Journal of Management Studies, 40(1), 141-174.

- Terry, L. D. (2005). “The thinning of administrative institutions in the hollow state”, Administration & Society, 37(4), 426-444.

- Thomas, R.; Hardy, C. (2011). “Reframing resistance to organizational change”, Scandinavian Journal of Management, 27(3), 322-331.

- Thomas, R.; Sargent, L. D.; Hardy, C. (2011). “Managing organizational change: Negotiating meaning and power-resistance relations”, Organization Science, 22(1), 22-41.

- Tsoukas, H.; Chia, R. (2002). “On Organizational Becoming: Rethinking Organizational Change”, Organization Science, 13(5), 567-582.

- Tyler, J. A. (2007). “Incorporating storytelling into practice: How HRD practitioners foster strategic storytelling”, Human Resource Development Quarterly, 18(4), 559-587.

- Vaara, E. (2010). “Taking the linguistic turn seriously: Strategy as a multifaceted and interdiscursive phenomenon”, in J. A. C. Baum and J. Lampel (Eds.), The Globalization of Strategy Research (Advances in Strategic Management) (Vol. 27, pp. 29-50), New York: Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Vaara, E.; Reff Pedersen, A. (2013). “Strategy and chronotopes: A Bakhtinian perspective on the construction of strategy narratives”, M@n@gement, 16(5), 593-604.

- van Hulst, M. (2012). “Storytelling, a model of and a model for planning”, Planning Theory, 11(3), 299-318.

- Weick, K. E. (1995). Sensemaking in Organizations, Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Weick, K. E.; Sutcliffe, K. M.; Obstfeld, D. (2005). “Organizing and the process of sensemaking”, Organization Science, 16(4), 409-421.

- Yin, R. K. (2009). Case study research, Design and methods, Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Parties annexes

Notes biographiques

Nicolas Arnaud, HDR, est professeur associé dans le département Management Organisation et Droit et occupe depuis 2012 le poste de Directeur Adjoint Audencia Grande Ecole. Ses recherches portent sur la compétence collective et les pratiques managériales dans une perspective communicationnelle. Ses travaux ont été publié dans différents journaux tels que Group & Organization Management, Management International, Finance Contrôle Strategie, Revue Française de Gestion, Gérer et Comprendre. Il est également l’auteur de plusieurs manuels et de nombreux articles de

Colleen E. Mills est professeure associée au Département de Management de l’université Canterbury. Elle s’intéresse aux processus organisationnels, particulièrement en contexte d’incertitude et de changement. Ses recherches l’ont conduite à élaborer des modèles de sense-making concernant la communication en situation de changement ainsi que sur les rumeurs, qui ont été publiés dans de nombreuses revues telles que Group and Organization Management, International Small Business Journal, International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour and Research, Journal of Business Communication, Australian Journal of Communication, Journal of Managerial Psychology and Education + Training. Elle est membre de plusieurs comités éditoriaux incluant Group and Organization Management et Communication Research and Practice.

Céline Legrand est professeure associée à Audencia et Co-Coordinatrice du département Management Organisation et Droit. Dans ses recherches elle s’intéresse aux dirigeants, aux équipes de direction et aux pratiques des managers. Ses travaux de recherche ont été publiés dans Management International, Revue Interdisciplinaire sur le Management l’Humanisme et l’Entreprise, Revue Gestion.

Parties annexes

Notas biograficas

NicolasArnaud, HDR, es profesor asociado en el Departamento de Organización de Gestión y Derecho desde 2012, y ocupa el cargo de Director Adjunto de Audencia Grande Ecole. Su campo de investigación se centra en las destrezas colectivas y las prácticas de gestión desde una perspectiva comunicacional. Sus trabajos han sido publicados en numerosas revistas como Group & Organization Management, International Management, Finance Contrôle Strategie, Revue Française de Gestion, Gérer et Comprendre. Es también autor de varios libros y numerosos artículos.

Collen E. Mills es profesora asociada en el departamento de Administración de la Universidad de Canterbury. Su investigación examina el proceso organizacional y enfoca sobre todo en periodos de incertitud y cambio. Su investigación ha producido modelos de “sense making” en lo que concierne a la comunicación en situaciones de cambio y acerca de los rumores; estos artículos han sido publicados en numerosas revistas como Group and Organization Management, International Small Business Journal, International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour and Research, Journal of Business Communication, Australian Journal of Communication, Journal of Managerial Psychology and Education + Training. Es también miembro de varios comités editoriales incluyendo Group and Organization Management, Communication Research and Practice.

Céline Legrand es profesora asociada en Audencia y una de las coordinadoras del departamento de administración, organización y derecho. En sus investigaciones se interesa sobre todo en los dirigentes, los equipos de dirección y las prácticas administrativas. Sus trabajos de investigación han sido publicados en Management international, Revue Interdisciplinaire sur le Management l’Humanisme, l’Entreprise, Revue Gestion.

Liste des figures

FIGURE 1

Multiple Levels of Discourse (based on Vaara 2010)

FIGURE 2

Model of Narrativity during Change

Liste des tableaux

Table 1

Illustrating Narrative Dynamics and the Resolution of Discursive Tensions