Résumés

Abstract

This paper investigates the impact of family control on domestic and international acquisition’s payment. This effect is important to understand since it will underpin all the future financial flexibility of the merged firms in a context of accelerating international market integration. We find that the percentage of cash payment in acquisitions is positively associated with family voting rights, but we highlight that family wedge is negatively associated with cash payment, which indicates the important role of control-enhancing mechanisms. Dilution risk is crucial at an intermediate level of control, since this relationship is nonlinear. Moreover, we show that both unused debt capacity and the increase in debt capacity are used by family firms to finance the relevant deals, but that these firms become overleveraged after merging, losing some financial flexibility in exchange for equity control purposes.

Keywords:

- Acquisitions,

- method of payment,

- family firms,

- leverage target,

- firm misevaluation

Résumé

On étudie l’impact d’un contrôle de type familial sur les moyens de paiement choisis lors d’acquisitions réalisées au niveau domestique et international. Cette décision sous-tend le niveau de flexibilité financière dont disposera ultérieurement la firme. Nos résultats montrent que le pourcentage du paiement réalisé à l’aide de liquidités augmente avec le niveau des droits de vote possédés par la famille, mais que la possession d’un «wedge» a l’effet inverse. Le risque de dilution joue un rôle crucial à des niveaux intermédiaires de contrôle. Enfin, les firmes familiales utilisent leur capacité d’endettement disponible pour financer ces opérations, mais deviennent surendettées après.

Mots-clés :

- Acquisitions,

- méthode de paiement,

- firmes familiales,

- ratio cible d’endettement,

- erreur d’évaluation de la firme

Resumen

Estudiamos el impacto de un control de tipo familiar de los medios de pago elegidos en los casos de adquisiciones locales e internacionales. Esta decisión se encuentra en la base del nivel de flexibilidad financiera de la se dispondrá la firma ulteriormente. Nuestros resultados muestran que el porcentaje de pago efectuado por medio de liquidez aumenta con el nivel de los derechos de voto que posee la familia, pero que la posesión de un «wedge» tiene el efecto inverso. El riesgo de dilución tiene un papel preponderante en los niveles intermedios de control. Por último, las firmas familiares utilizan la capacidad de endeudamiento de la que disponen para financiar estas operaciones, exponiéndose a un sobreendeudamiento.

Palabras clave:

- Adquisiciones,

- método de pago,

- firmas familiares,

- radio de endeudamiento,

- error de evaluación de la firma

Corps de l’article

A lot of firms in the world are controlled by their founders, or by the founders’ families and heirs (Burkart et al., 2003). Such a family ownership is common among privately held companies, but also significant among publicly traded firms. Anderson and Reeb (2003) find that family ownership is present in one third of the S&P 500 and accounts for 18% of outstanding equity. Contrary to their anticipations, they find family firms perform better than non family firms, as Sraer and Thesmar (2007) for France. In fact their results are not consistent with the hypothesis (private benefits extraction) developed by Shleifer and Vishny (2003) that minority shareholders are affected by family ownership. This finding suggests that family ownership is an effective organizational structure.

Caprio et al. (2011) show that family firms tend to adopt conservative management policies, and for example they undertake fewer mergers and acquisitions than non-family firms. But they also need to grow and to invest abroad. Although cross-border acquisitions offer strategic, behavioral and economic benefits, as well as new opportunities, they also expose the acquirer to considerable risks, including, economic, currency, legal and political risks. Thus acquirers of foreign targets face a trade-off between the costs and benefits of international business expansion (Barbopoulous et al., 2012). But, and even more importantly, families are long-term owners, and their main objective is the intergenerational transfer of managerial and ownership control. Thus, family firms, when they decide to undertake a merger or an acquisition attach particular importance to the method of payment of the transaction since both cash and stock payments could definitively affect ownership and capital structures.

Thus family firms face a choice when they want to acquire another company. Issuing a number of new shares for a stock payment can dilute the ownership interests of existing shareholders, while borrowing to raise funds for a cash offerings increases the acquirer’s financial leverage and risk. Examining this tradeoff, would be related to Faccio and Masulis study (2005), but they don’t consider family firms specifically, and focus on the European Union in its entirety mixing common law and civil law countries in the same sample, even if at the end they split it taking into account continental countries and the others. This subject has also some commonalities with Martynova and Renneboog (2009) work, using European data to study the impact of takeover financing on the expected value creation of the takeover transaction. Concerning US data, Basu et al. (2009) are looking for the eventuality of families’ entrenchment at low levels of ownership in case of mergers. Finally André and Ben-Amar (2010) paper is the most closely related to our project, but is devoted to Canadian firms. Concerning France this paper fills the void analyzing the relationship between corporate control and choice of payment method in acquisitions. Besides, other related prior studies show that the payment decision may be also affected by financial constraints (Ghosh and Jain, 2000) and by asymmetry of information (Chemmanur et al., 2009).

It is important to understand here that the choice of a specific means of payment signals private information at least about target value and synergy values, and then split wealth and risk differently among the different stakeholders. But it doesn’t create value by itself. Mixed payments may be considered as a partial insurance device by risk-averse shareholders. Nevertheless the design of an acquisition payment scheme is essential to be properly established, because the balance between cash and stocks will affect the future financial flexibility of the merged entity, and will determine its financial capacity to answer the new challenges faced in the future. Moreover, it redesigns the financial coalition in charge of the firm’s guidance. Take notice that financial constraints encountered by family firms may lead to “corner solutions” for full cash financing (equity control motive) or for an all-equity financed deal (in case of severe credit rationing). Specificities of family-controlled firms’ agency conflicts make the study of managers’ decisions particularly interesting, especially since family members often contribute to firm management. On the one hand, debt financing might be considered too risky due to increased bankruptcy probability. This scenario may happen since family firms are more reluctant to increase financial risk (e.g. to raise the financial leverage) than non-family firms are, because their portfolios are less diversified. On the other hand, they may prefer to avoid equity financing since new stocks will gradually dilute family control. Thereafter, future generations of the founding family will be profoundly affected if the family loses control. Thus the main aim of the paper is to examine whether the payment decision of French family acquirers is more affected by the firm’s control motive than by the risk reduction motive for domestic and cross-border acquisitions.

We consider France to be an appropriate institutional context to study this relationship, since there is a dominance of family firms in the French market. Moreover, the French acquisition market is one of the most active in Europe. Faccio and Lang (2002) show that two-thirds of French firms are controlled by a single family. This market is also characterized by a high level of wedge that could be explained by the discrepancy between the voting rights (effect of the dual class shares) and the cash flows rights owned. Besides, more than twenty percent of significant French firms’ employees are under the management of a relative of the founder (Bach, 2010).

Using a sample of 265 acquisitions in the period 1997-2008, we find that the percentage of cash used in payment is positively associated to family voting rights. The relationship is nonlinear and the avoidance of stock payment is particularly high at an intermediate level of control. However, dilution of firm control is not a serious determinant of payment decision at low and very high levels of voting rights. The inflexion points are 16.81% and 84.24%. We also highlight a strong link between the percentage of cash and the family wedge, which indicates that the use of control-enhancing mechanisms increases the likelihood of cash payment.

Our paper contributes to several areas of research. A number of studies have examined the relation between method of payment and managerial ownership or largest shareholder ownership. First, we shed light on the lack of studies on family ownership. Second, we show that the relationship between the percentage of cash used in payment and voting rights is nonlinear, inconsistent with Faccio and Masulis (2005) who find a linear relationship for Continental Europe acquirers. Thus it highlights that if for very low or very high equity stake, there no departure from the standard case, but for an intermediate’s one, the control motive in French family firms is so important that it dominates all other drivers of the payment scheme’s decision Third, we shed light on the lack of studies on the impact of acquirer debt capacity and acquisition financing. Fourth, we conclude that family firms and non-family firms have similar leverage deviation pre-acquisitions. However, their leverage deviations are different after the transactions and this fact has managerial implications since a significant loss of financial flexibility (debt overhang for example) occurs in these family acquiring firms, impeding some developments in the future, taking for granted the accelerating international market integration. Finally, we fill the gap in the French acquisition market literature by examining the determinants of payment decisions in France and abroad.

Related literature

In this section, we provide an overview of the existing literature of family firms’ characteristics and their payment decision motivations. At the same time, we present studies that analyze the role of debt capacity and acquirer misevaluation as determinants of the method of payment.

Equity control in mergers and acquisitions

Families usually invest most of their private wealth in their company and are not widely diversified. Thus, family shareholders would be more averse to factors that would increase the risk of their loss of control than would non-family shareholders. Franks et al. (2012) suggest that European family firms benefit from “developed relationship banking” that provides access to external financing. Existing theoretical literature has investigated whether a large shareholder’s control motive influences the mix of debt and equity used in a firm’s capital structure to maintain control. Harris and Raviv (1988) and Stulz (1988) focus on managerial control and find that the capital structure decision depends on the level of managerial voting rights, since equity financing will introduce control dilution and lead to outside block holder intervention. Therefore, authors conclude that manager voting rights are negatively associated to the likelihood of equity financing.

Risk avoidance is one of the most important costs that large and undiversified shareholders can impose on the firm (Shleifer and Vishny, 1986). Anderson et al. (2003) show that family firms are less diversified than non-family firms. Therefore, families have strong incentives to minimize firm risk, due to the undiversified nature of their portfolios and their desire for firm survival. To reduce firm risk and the likelihood of firm bankruptcy, families may seek capital forms that decrease probabilities of default, indicating greater reliance on equity financing rather than debt financing.

Based on Stulz’s (1988) theoretical arguments, previous research has examined the relationship between corporate control considerations and the method of payment in acquisitions. Most studies focus on managerial ownership. Amihud et al. (1990), Yook et al. (1999) and Chang and Mais (2000) show that in order to maintain their controlling power over a firm, managers in the U.S. are reluctant to use stock as a medium of acquisitions payment. Martin (1996) and Ghosh and Ruland (1998), highlight that the relationship is nonlinear. At very low and very high levels of ownership, managers may not be sensitive to the dilution problem. However, at an intermediate level of control, a stock payment may lead managers to lose their control positions.

Faccio and Masulis (2005) focus on European acquirers and study the role of the largest shareholder’s ultimate control in payment decision, without giving importance to their type of block holder. They find a nonlinear relationship for a sample of U.K. and Irish firms. However, for Continental Europe acquirers, Faccio and Masulis (2005) show that the higher the dominant shareholder voting control, the greater the likelihood of cash payment.

As far as we know, there are only two studies that focus on family ownership. Basu et al. (2009) find that entrenched U.S. families, who are interested in preserving their control over the firm, are less likely to choose stock as the method of payment. However, families whose incentives are aligned with those of minority shareholders are more likely to do what is best for the firm, even if it results in some slight reduction of control rights. Using a sample of Canadian acquisitions, André and Ben-Amar (2010) find that the percentage of cash payment increases with the percentage of family voting rights. They also find that this percentage decreases with the use of control enhancing mechanisms.

In our analysis, we hypothesize that control motivation outweighs risk reduction motivation and we expect a positive relationship between family control and the proportion of cash used in French acquisitions payment. Moreover, we hypothesize that this relationship depends on the level of family control and predict that it is nonlinear. Finally, we hypothesize that control-enhancing mechanisms affect payment decisions and we expect a negative association between the family wedge and the percentage of cash.

Debt capacity in mergers and acquisitions

Following the predictions of trade-off theory, when firms adjust their capital structures, they tend to move toward a target debt ratio (Hovakimian et al, 2001; Leary and Robets, 2005 and Kayhan and Titman, 2007). The increase in leverage may be due to the utilization of pre-acquisition debt capacity. Underleveraged acquirers tend to finance the transaction with debt for two reasons. First, debt financing allows a firm to adjust the capital structure and to attain the target leverage. Second, it avoids the use of equity financing and by consequence dilution of control. Harford et al. (2009) and Uysal (2011) study the relationship between the payment method of U.S. acquisitions and the deviation of acquirer leverage from its target level. They find that the pre-acquisition leverage deviation significantly affects the payment method. When a firm is underleveraged with respect to the target level of debt, it is more likely to use cash payment.

On the other hand, Ghosh and Jain (2000) suggest that an increase in financial leverage after an acquisition could result from an increase in debt capacity. This increase in debt capacity may represent one of the main motives of acquisitions. Therefore, it should lead to debt financing. Harford et al. (2009) show that acquisition induces change in target leverage, and is positively associated with the use of debt financing as Lantin, (2012). In our study, we hypothesize that both the unused debt capacity and the increase in debt capacity due to mergers and the acquisition of tangible assets are positively related to the percentage of cash used in acquisitions payment.

Acquirer misevaluation

The uncertainty about acquirer value introduces an adverse selection effect. Myers and Majluf (1984) and Hansen (1987) predict that acquirers prefer to finance transactions with cash when they consider their stock undervalued and prefer to finance with equity when they consider their stock overvalued. This misevaluation problem is mainly due to information asymmetries between managers and outside investors. Shleifer and Vishny (2003) also hypothesize that acquirers will use stocks if they think that their shares are overvalued, and will pay with cash if they believe their shares undervalued or correctly valued.

From a managerial point of view, paying with shares for the acquiring company allows for risk sharing if merger is not quite successful. Risk here, is of an informational nature about the true value of the acquired company as well as an economic risk concerning the future. As for the acquired company, it may not be easy to assess accurately the potential gains of synergy that may stem from the acquisition, and its shareholders may want to get some part of the payment in cash to lower risk. Thus, if the information asymmetry is important for both sides, a mixed payment may be chosen and considered as a partial insurance device. For the acquiring company paying with cash will leave acquirer’s shareholders with all the benefits of synergies, if they happen to be large. Thus the cash-percentage proposed by the acquiring company constitutes a key element of private information regarding synergy gains estimate. This being said, when opacity exists for cross-border transactions, many small deals are paid only in cash (Chevalier and Redor, 2010). Conversely, when the value of the transaction is increasing sharply, a share payment has to take place in addition with a cash payment. Yook et al. (1999) and Chang and Mais (2000) study the impact of information asymmetry and conclude that it influences significantly the payment method decision. Chemmanur et al. (2009) find that acquirers chose stock offers which are overvalued and cash offers which are correctly valued. In our analysis we expect a negative association between the percentage of cash used in acquisition payment and an overvaluation of the acquirer value.

Data and methodology

This section presents the sample selection process, the methodology and variables used to explain the payment method. Finally, it describes the summary statistics of our sample.

Sample selection

The sample of corporate acquisitions is drawn from completed deals undertaken by French listed acquirers between January 1997 and December 2008. Operations are identified from the Thomson One Banker Merger and Acquisition database. Acquisitions involving firms operating in highly regulated industries, such as financial and utility sectors, are excluded. Acquisitions are defined as occurring when the bidder controls less than 50% of the target’s share before the announcement and more than 50% after the transaction. We limit our sample to acquisitions whose deal value is more than €1 million and which is at least 1% of the acquirer’s market value of equity measured at the end of the fiscal year prior to the announcement date. Our sample includes, with respect to these criteria, 265 acquisitions made by 177 firms[1]. Acquirers’ stock prices and accounting data are extracted from the Datastream database. Ownership data is manually collected from acquirer Annual Reports preceding and closest to the acquisition announcement.

Methodology and variable definitions

We consider the proportion of cash used to pay the acquisition as a dependent variable. This is a censored variable, which varies by definition between zero and one. Thus, we adopt a Tobit specification[2], and we use the quasi-maximum likelihood (Huber/White) standard errors to adjust for heteroskedasticity. Our independent variables used to explain the percent of cash used in French acquisitions are the following (Appendix A lists variables used in this study):

Family control

Fam_Vote: We use the same methodology as La Porta et al. (1999), Claessens et al. (2000) and Faccio and Lang (2002) to measure the voting rights held by the family[3]. This procedure considers the pyramidal structures and the double voting rule. Voting rights are measured as the weakest link in the control chain.

Fam_Wedge: The family wedge, or the family excess control, is measured by the ratio of the level of voting rights to the cash-flow rights. The cash-flow rights are measured after taking into account the whole chain of control[4].

Financial constraints

Leverage deviation: We define the leverage deviation as the difference between a firm’s actual and predicted leverage. Following Hovakimian et al. (2001) and Leary and Robets (2005), we focus on market leverage instead of book leverage[5]. We use the same Tobit regression model as in Kayhan and Titman (2007) to calculate a firm’s predicted leverage (see appendix B). In contrast to their model and conforming to Harford et al. (2009), we estimate separate annual regressions to predict leverage rather than estimating a pooled regression model. Market leverage is calculated as the total debt scaled by the sum of total debt and the market value of equity. The relation between this variable and the proportion of cash is expected to be negative.

Induced change in target leverage: This variable captures how the acquisition changes the firm’s target level of leverage. It is measured as predicted market leverage in year +1 subsequent the completion of the acquisition minus predicted market leverage in year -1. Year 0 is the year of acquisition completion. The relation between this variable and the proportion of cash is expected to be positive.

Average leverage: It is the three-year preceding the acquisition average market leverage. The borrowing capacity of the acquirer is related to its leverage ratio (Faccio and Masulis, 2005). We expect a positive relation between the average leverage and the use of cash for payment.

Bankruptcy risk score: This variable measures the likelihood of distress and represents a proxy for adjustment costs of capital structure. Following Graham (1996), to calculate this score we use a modified version of the Altman-Z score based on Mackie-Mason (1990). This variable is defined as total assets divided by the sum of the following items: 3.3 EBIT + sales + 1.4 retained earnings + 1.2 working capital. The relation between the bankruptcy risk and the proportion of cash used for payment is expected to be negative.

Cash reserve: Acquirers having large amounts of cash reserves are more likely to use cash to finance the acquisition (Harford, 1999). The pecking order theory predicts that, as a result of adverse selection costs, firms prefer to finance their investments with internal funds or debt rather than equity. Cash reserves are measured as the firm’s cash and cash equivalents level divided by total assets. We expect a positive impact of cash reserves on the use of cash as a method of payment.

Acquirer misevaluation

Valuation error: This variable measures an acquirer’s value taking into account the effects of private information, since an important determinant of the payment method is this private information about its own value. We adopt Chemmanur et al. (2009) methodology to measure this variable:

Where P0 is the acquirer’s closing stock price on the day before the acquisition announcement and V0 is the intrinsic value of the acquirer’s stocks conditional on insiders’ private information at the acquisition. We estimate the intrinsic value using Ohlson’s (1990) Residual Income Model (RIM) following the set-up used by D’Mello and Shroff (2000) and Jindra (2000). Appendix C presents the method used to estimate the intrinsic value. Given that an acquirer chooses the method of payment after observing its stock price as of the announcement day (Chemmanur et al, 2009), we measure the misevaluation of the acquirer’s stock on the day before this announcement day[6].

RUNUP: Chang and Mais (2000) and Faccio and Masulis (2005) use the prior stock performance as a proxy for acquirer overvaluation (or undervaluation). The higher the RUNUP, the higher the likelihood to use stocks in payment since the acquirer is considered overvalued. The RUNUP is calculated as the cumulative abnormal return over the year proceeding the acquisition announcement month[7].

Market-to-Book ratio: Prior research documents a positive relation between the market-to-book ratio and the likelihood of stock payment (Martin, 1996; Faccio and Masulis, 2005). Following La Porta (1997) and Shleifer (2000), we consider the market-to-book ratio as a proxy for a firm’s valuation errors. Rhodes-Kropf et al. (2005) test the impact of valuation errors on acquisition activity. Based on a decomposition of the market-to-book ratio, authors find that misevaluation affects the method of payment.

Descriptive statistics

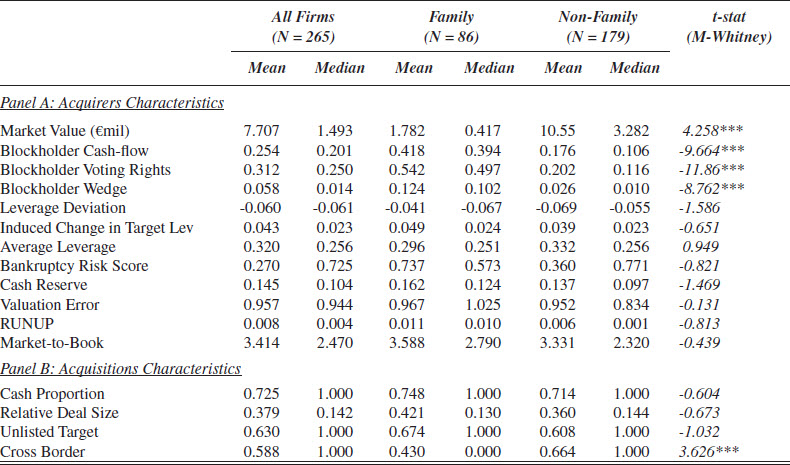

Table 1 provides relevant summary statistics of variables and the significance test between family and non-family firms. Following Barontini and Caprio (2006), a firm is defined as a family one when an individual or a family controls more than 51% of voting rights, or controls at least 10% of voting rights and more than double the voting rights of the second largest shareholder. Family firms are acquirers in 32.4% of cases (86 out of 265)[8].

Table 1

Summary statistics

Family firm is determined when an individual or a family controls more than 51% of voting rights, or controls more than double the voting rights of the second largest shareholder. Market Value is measured at the end of the fiscal year preceding the acquisition. Blockholder Cash-flow is holdings of the ultimate blockholder. Blockholder Voting Rights is voting rights held by the ultimate blockholder. Blockholder Wedge is the difference between the ultimate blockholder’s voting rights and cash-flow rights. Leverage Deviation is the acquirer’s market leverage minus its target market leverage estimated using Kayhan and Titman’s (2007) model, one year prior the acquisition. Induced Change in Target leverage is the change in target market leverage from year -1 to +1 around the acquisition. Average Leverage is the three-year average market leverage, before the acquisition. Bankruptcy Risk Score is Mackie-Mason’s (1990) modified version of the Altman-Z score: total assets divided by (3.3 EBIT + sales + 1.4 retained earnings + 1.2 working capital). Cash Reserve is cash and cash equivalents divided by book value of assets. Valuation Error is the acquirer under- or overvaluation estimated based on Chemmanur et al. (2009) recommendations. RUNUP is the cumulative abnormal return over the year proceeding the acquisition announcement month. Market-to-Book ratio is measured one year prior the acquisition. Cash Proportion is the percent of cash used in payment. Relative Deal Size is the deal value divided by the market value. Unlisted Target is a dummy variable equal to 1 if target is a unlisted firm and 0 otherwise. Cross Border is a dummy variable equal to 1 if the target is not a French firm, and 0 otherwise. ***, ** and * denote significance at the 1%, 5% and 10% levels, respectively.

Panel A shows that the ultimate shareholder holds 54.2% of voting rights in family firms and 20.2% in non-family firms. Discrepancy between cash-flow rights and voting rights is higher in family firms. Mean wedge value is equal to 12.4% in family firms and to 2.6% in non-family firms. Table 1 provides information about acquirer firm leverage deviation. Pre-acquisition leverage deviation for all firms is negative, consistent with Ghosh and Jain (2000) study for the U.S. market. This evidence suggests that acquirers have unused debt capacity. Specifically, the mean leverage deviation is -0.041 and -0.069 for family and non-family firms, respectively. The mean acquisition-induced change to a firm’s leverage deviation is positive and equal to 0.043, consistent with Harford et al. (2009). This acquisition-induced change is 0.049 and 0.039 for family and non-family firms, respectively. We find that the average market leverage of all acquirers represents about one third of total assets. Statistics indicate that family firms have higher cash reserve than non-family firms, 16.2% and 13.7%, respectively. Panel A shows that means of valuation errors are positive and inferior to one, which indicates that both family and non-family acquirers are undervalued. We note that the median valuation error of family firms is slightly superior to one.

Family firms are smaller than non-family firms. The mean market capitalization of family firms is equal to € 1.78 billion, for non-family firms, it is equal to € 10.55 billion. However, Panel B shows that the relative deal ratios are quite similar. It is equal to 42.1% for family firms and 36% for non-family firms. Panel B also shows that cash proportion used in acquisition payment is 74.8% and 71.4% for family and non-family firms, respectively. Recall that Linn and Switzer (2001) have found that cash acquisitions were empirically associated with better operating performance. We find that 66.4% of non-family firm acquisitions are cross-border. However, only 43% of family firm deals are overseas, and financed with cash. This is consistent with a more conservative managerial attitude with respect to internationalization.

Results and discussion

In this section, beyond the idea of designing the gain sharing process through the financial set up of the acquisition, we test the impact of family control and of other determinants on the method of acquisition payment. We investigate the non-linear relationship between family control and the percentage of cash payment. Finally, we study acquirer changes in pre- and post-acquisition leverage deviation.

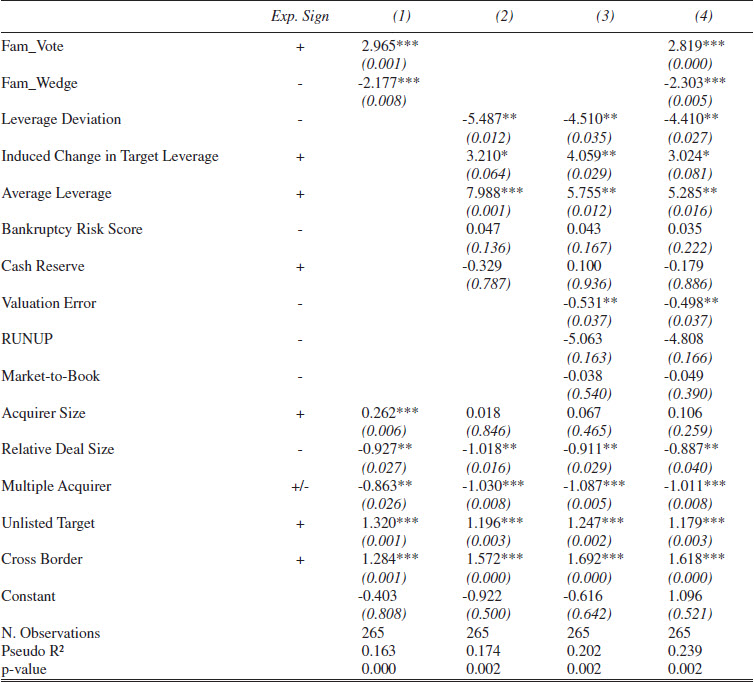

Family control and the cash proportion in acquisition payment

Table 2 presents the results of our Tobit regressions explaining the proportion of cash used in French acquisitions. Model (1) shows that the relationship between the family voting rights and the percentage of cash is positive and significant at the level of 1%. This evidence suggests that the higher the family control, the higher the likelihood to use cash in acquisition payments. This is observed for domestic and foreign deals. This evidence indicates that families are averse to a dilution of their control position. Families avoid the use of stocks in order to maintain family control. This result confirms the control motive hypothesis, consistent with Amihud et al. (1990), Yook et al. (1999), and Chang and Mais (2000) who find similar results studying managerial ownership. Our findings are in line with those of André and Ben-Amar (2010) who find a positive relation between family voting rights and the percentage of cash in Canadian acquisitions.

We find that the percentage of cash is negatively related to the family wedge. This relationship is statistically significant at the level of 1%. This evidence shows that families that maintain firm control thanks to pyramidal structures and double voting rules are less sensitive to the risk of dilution related to stock payments. Therefore, French control-enhancing mechanisms play an important role in determining the method of payment in acquisitions. Our findings confirm those of André and Ben-Amar (2010) and are in line with those of Ellul (2009) which highlights that families that can keep control through control-enhancing mechanisms have a lower propensity to use leverage.

Model (2) tests the impact of financial constraints on the choice of method of payment. We find that the pre-acquisition year leverage deviation is significantly negatively associated with the percentage of cash used in the acquisition payment. Therefore, when a firm is overleveraged (Lantin, 2012), it has a lower likelihood to pay for the acquisition with cash and take on even more debt. This finding supports the proposition that firms have leverage targets and that these targets affect financing decisions in acquisitions. Our analysis indicates that underleveraged firms are characterized by an unused debt capacity, thus the likelihood of using cash payment in acquisitions is high. These results are similar to those of Gosh and Jain (2000) and Uysal (2011). For underleveraged firms, on the one hand, debt financing allows a firm to avoid equity financing, and by consequence a dilution of control. On the other hand, it may be considered as an opportunity to adjust the firm’s capital structure. Model (2) also shows that acquisition-induced change in target leverage is significantly positively associated to the cash proportion. This result indicates that it is more likely to use debt financing given that the acquisition will improve the acquirer’s debt capacity. Harford et al. (2009) find a similar result and explain that managers are more likely to structure a leverage-increasing acquisition if their firm’s target leverage increases as a result of the acquisition.

Model (3) studies acquirer misevaluation hypothesis. We find a negative and significant relationship between the percentage of cash and the acquirer valuation error. That is, the higher the extent of acquirer overvaluation based on insider private information, the higher the likelihood of choosing stock as the method of payment. These findings are in line with the predictions of Hansen (1987), and Shleifer and Vishny (2003). Using the RUNUP and the market-to-book ratio as measures of acquirer misevaluation, we also find that it is negatively related to the likelihood of cash payment. However, these relationships are not statistically significant.

In model (4) we include all independent variables and we obtain similar results. We control for the relative size of the target to the acquirer in all models. We find that firms acquiring large targets are more likely to use stock payment. We also control for the public status of the target. As predicted by Hansen (1987), we show that it is more likely to use cash in presence of cross-border deals (highly significant coefficient). International development through M&A then compels firms to financial planning and to have at their disposal unused debt capacity, since as in Chevalier and Redor (2010) it is the principal vehicle of deal’s financing. This finding can be explained by differences in legal environment between countries, and thus by reluctance of shareholders to an equity offer. We also show that cash payment is more probable when the target is an unlisted firm. This is in line with Faccio and Masulis results (2005) because acquired company’s shareholders seem to be less interested by a stock payment since the sale of their assets is often due to restructuring or liquidity problems. This result also supports acquirer aversion to creating a new blockholder, since ownership of unlisted targets is often concentrated. Finally, we control for target nationality.

Table 2

Determinants of the cash proportion used in acquisition’s payment

Family Vote is voting rights held by the family. Family Wedge is the ratio of the family voting rights to the family cash-flow rights. Leverage Deviation is the acquirer’s market leverage minus its target market leverage estimated using Kayhan and Titman’s (2007) model, one year prior the acquisition. Induced Change in Target leverage is the change in target market leverage from year -1 to +1 around the acquisition. Average Leverage is the three-year average market leverage, before the acquisition. Bankruptcy Risk Score is Mackie-Mason’s (1990) modified version of the Altman-Z score: total assets divided by (3.3 EBIT + sales + 1.4 retained earnings + 1.2 working capital). Cash Reserve is cash and cash equivalents divided by book value of assets. Valuation Error is the acquirer under- or overvaluation estimated based on Chemmanur et al. (2009) recommendations. RUNUP is the cumulative abnormal return over the year proceeding the acquisition announcement month. Market-to-Book ratio is measured one year prior the acquisition. Cash Proportion is the percent of cash used in payment. Relative Deal Size is the deal value divided by the market value. Unlisted Target is a dummy variable equal to 1 if target is a unlisted firm and 0 otherwise. Multiple Acquirer is a dummy variable equal 1 if acquirer makes at least three acquisitions between 1997 and 2008. Cross Border is a dummy variable equal to 1 if the target is not a French firm, and 0 otherwise. The estimation is based on a Tobit model. Year dummies are added in the regressions to account for macroeconomic changes in the time series. The statistics are based on Huber/White (sandwich estimator) heteroskedasticity-consistent standard errors. ***, ** and * denote significance at the 1%, 5% and 10% levels, respectively.

Table 3

Cash proportion: a non linear function of family control

Family Vote is voting rights held by the family. Family Wedge is the ratio of the family voting rights to the family cash-flow rights. Leverage Deviation is the acquirer’s market leverage minus its target market leverage estimated using Kayhan and Titman’s (2007) model, one year prior the acquisition. Induced Change in Target leverage is the change in target market leverage from year -1 to +1 around the acquisition. Average Leverage is the three-year average market leverage, before the acquisition. Bankruptcy Risk Score is Mackie-Mason’s (1990) modified version of the Altman-Z score: total assets divided by (3.3 EBIT + sales + 1.4 retained earnings + 1.2 working capital). Cash Reserve is cash and cash equivalents divided by book value of assets. Valuation Error is the acquirer under- or overvaluation estimated based on Chemmanur et al. (2009) recommendations. RUNUP is the cumulative abnormal return over the year proceeding the acquisition announcement month. Market-to-Book ratio is measured one year prior the acquisition. Cash Proportion is the percent of cash used in payment. Relative Deal Size is the deal value divided by the market value. Unlisted Target is a dummy variable equal to 1 if target is a unlisted firm and 0 otherwise. Multiple Acquirer is a dummy variable equal 1 if acquirer makes at least three acquisitions between 1997 and 2008. Cross Border is a dummy variable equal to 1 if the target is not a French firm, and 0 otherwise. The estimation is based on a Tobit model. Year dummies are added in the regressions to account for macroeconomic changes in the time series. The statistics are based on Huber/White (sandwich estimator) heteroskedasticity-consistent standard errors. ***, ** and * denote significance at the 1%, 5% and 10% levels, respectively.

Non-linearity between family control and the cash proportion

As we may infer the avoidance of stock payment should be particularly high at an intermediate level of control. Conversely as we may conjecture, dilution of the firm control may not be an important determinant of the means of payment for very low or very high levels of voting rights owned by the controlling group. To test the non-linear relation between family control and the percentage of cash used in payment, we include in our regressions the squared and the cubed values of the family voting rights as proxies for the creation of a rival blockholder if the acquisition is paid with stocks.

In the first regression of table 3, we consider a linear relation between family control rights and the fraction of cash. We find a significant positive relation between the two variables. Results of regression 3, document a non-linear association between family control level and the likelihood of cash payment. We find that family voting control is significant and negative in the level and cubed value, and positive in the squared value. Our results suggest that control considerations influence the choice of the method of payment in acquisitions. In particular, families with an intermediate level of control are more likely to avoid dilution and therefore choose cash as the method of payment. Our findings are consistent with control not being a serious concern at low levels of voting rights, then becoming important at intermediate levels, but becoming less important again at very high levels. The inflexion points are 16.81% and 84.24%.

Aversion to new block holder creation is not pronounced in family firms with low and high control levels. This new block holder may enhance value due to its potential monitoring role. The positive relationship with the percentage of cash payment for an intermediate level of voting rights is consistent with the findings of Amihud et al. (1990), Martin (1996), and Ghosh and Ruland (1998) for U.S. acquirers. However, our findings are different from those of Faccio and Masulis (2005) who find a linear, rather than cubic, relation between cash payment and voting rights for Continental Europe acquirers. Therefore, we conclude that French family shareholders are much more likely than others to avoid dilution when they have control of an intermediate level. The divergence between our findings and those of Faccio and Masulis (2005) can be explained by the fact that these authors studied the control level of the largest shareholders and did not consider specifications of family shareholders. Our results differ also on this point from those of André and Ben-Amar (2010) on the Canadian case. But it may come from the different legal systems prevailing across European countries, creating for French companies (civil law country) stronger motivations to maintain high voting control (La Porta et al., 1997).

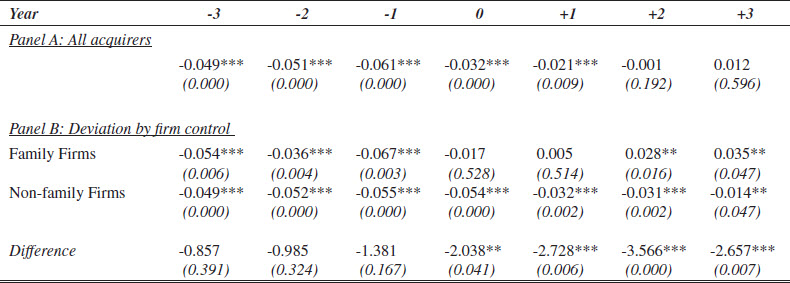

Changes in acquirers’ pre- and post-acquisition leverage deviation

Table 4 presents median statistics on the evolution of leverage deviations over the period from years -3 to +3 around the acquisition. Panel A shows that during the pre-acquisition year, acquirers are significantly underleveraged. We want to emphasize, that unused debt capacity is the cornerstone of the financial policy allowing cross-border acquisitions to be financed with cash without dramatically increasing the bankruptcy risk of the acquiring company. The leverage deviation for all acquirers is -0.049, -0.051, and -0.061, in year -3, -2 and -1, respectively, consistent with Gosh and Jain (2000) and Harford et al. (2009). This high leverage deviation decreases gradually following the acquisition in line with Lantin (2012) remarks. In years 0, and 1 it attains -0.032 and -0.021, respectively, and still is statistically significant. In years +1 and +2 the leverage deviation becomes statistically insignificant and near to zero, which indicates that the majority of acquirers adjust their capital structure to attain their target leverage. This result confirms the significant relation between the unused debt capacity and the financing decision of the acquisition.

In panel B, we study the evolution of leverage deviations over the same period, distinguishing between family firms and non-family firms. During the three years preceding the acquisition, we find that both family and non-family firms are significantly underleveraged. Results also show that there is no significant difference between their leverage deviations. Following the acquisition, we find that the evolution of leverage deviations depends on who controls the firm.

In family firms, leverage deviations are approximately equal to zero in the year of the acquisition and in year +1. However, in year +2 and +3, family firms become significantly overleveraged, 0.028 and 0.035, respectively. On one hand, this finding may indicate that family firms benefit from acquisition-induced improvement in their debt capacity. The improvement is particularly remarkable in family firms, since they are often characterized by small size. But on the other hand, one may consider that family firms were compelled to adopt a “financial forcing” strategy to pay the acquired assets. This may curb next developments and have negative managerial implications for the future. Moreover their bankruptcy risk is increasing. Our result is consistent with Andres (2011) who finds that family firms are heavily leveraged which is probably the consequence of reluctance to issue equity. Concerning non-family firms, we find that the adjustment of the capital structure is slow compared to family firms. The leverage deviation decreases over the period 0 to +3, but is still significantly negative. It is equal to -0.054 in year 0. Then it is about -0.031 in years +1 and +2. Finally, it goes down to -0.014 in year +3.

Table 4

Median leverage deviation pre-and post-acquisition

Family firm is determined when an individual or a family controls more than 51% of voting rights, or controls more than double the voting rights of the second largest shareholder (we have used several definitions for family control, but the results are not different). Leverage Deviation is the acquirer’s market leverage minus its target market leverage estimated using Kayhan and Titman’s (2007) model. Wilcoxon test is used for median leverage deviation. Mann-Whitney test is used for the difference in between family and non-family firms in the median leverage deviation. ***, ** and * denote significance at the 1%, 5% and 10% levels, respectively.

Robustness checks

In this section, we test the robustness of our results by using alternative definitions of the method of payment and a spline function to examine the non-linear relation between family control and proportion of cash payment. In addition, we revise the relative deal size criteria when selecting our sample. Finally, we consider alternative measures of independent variables used.

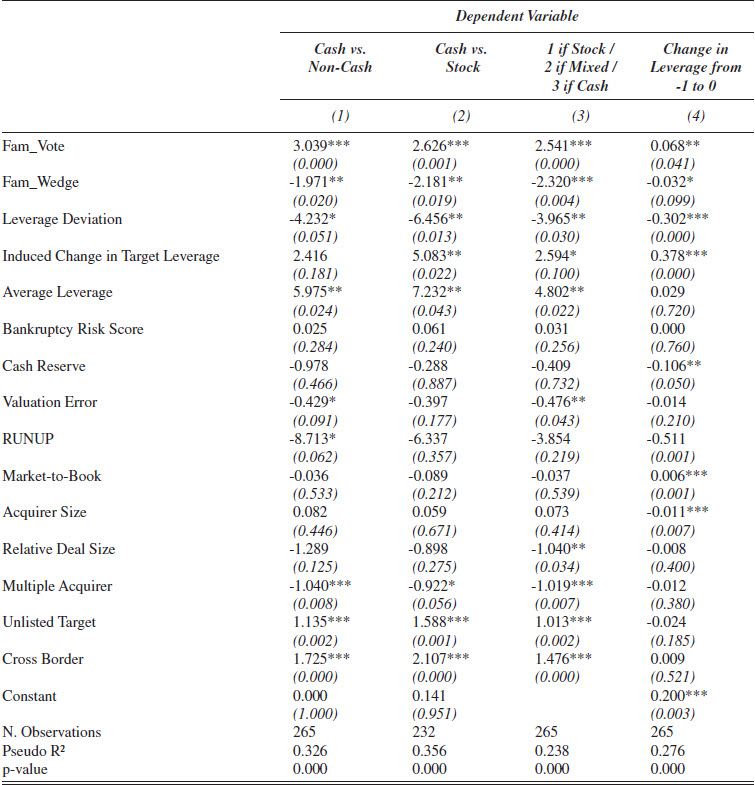

Alternative measures of the method of payment

In many acquisitions, the acquirer does not always determine the actual proportion of cash payment. Target shareholders are offered a choice of stock or cash payment. For that reason, the decision is more characterized as choosing between cash, stock, or mixed payment. Table 5 tests the robustness of our results using different presentations of the method of payment, and thus, different estimation methods.

In model (1), the dependent variable is 1 if the acquisition is integrally paid with cash, and 0 if paid with stock or with a mixture of cash and stock. In model (2), the dependent variable is 1 if the acquisition is integrally paid with cash, and 0 if integrally paid with stock. These two models are estimated with a logistic regression method. While these models compare between two alternatives of payment, model (3) allows us to focus on the qualitative decision to pay with cash, stock, or a mixture. The dependent variable in this model is 1 if the acquisition is paid with stock, 2 if paid with a mixture, and 3 if paid with cash. We use the ordered logistic regression to estimate model (3). Finally, we use the change in leverage from year -1 to 0 as a proxy for the method of payment. This variable allows us particularly to detect acquisitions paid with cash and financed with debt. We estimate model (4) using the Mackinnon and White (1985)’s OLS heteroskedasticity-consistent standard errors procedure. The four regressions confirm the robustness of our results, since we obtain the same variable signs and similar statistical significance. It is interesting to note that multiple acquisitions are negatively associated with cash, since repetitive deals lead inevitably acquiring firms to open their equity, because they face leverage restrictions. Family control and financial constraints variables are still highly significantly associated to the likelihood of cash payment.

Non-linear relationship between family control and the percentage of cash

To test the robustness of the non-linear relationship between the family voting rights and the proportion of cash payment, we use a spline function variable approach. The first segment of the spline is from 0 percent to 20 percent voting rights (low level), the second segment is from 20 percent to 60 percent (intermediate level), and the third one implies voting rights greater than 60 percent (high level). Each coefficient measures the slope of the regression line over those intervals. The variables are defined as follows:

Table 5

Determinants of the method of payment

In model (1) the dependent variable is a dummy equal to 1 if only cash is used for payment, and 0 otherwise. In model (2) the dependent variable is dummy equal to 1 if only cash is used for payment, and 0 if only stocks are used. In model (3) the dependent variable is equal to 1 if only stocks are used, equal to 2 if mixed payment is used and equal to 3 if only cash is used. In model (4) the dependent variable is the market leverage at the year of acquisition minus the market leverage one year prior the acquisition. The estimation is based on a Logit regression for models (1) and (2), on an Ordered Logit regression for the model (3), and on and OLS regression for the model (4). Year dummies are added in the regressions to account for macroeconomic changes in the time series. The statistics are based on Huber/White (sandwich estimator) heteroskedasticity-consistent standard errors for model (1) to (3), and on MacKinnon and White (1985) adjustment in model (4). ***, ** and * denote significance at the 1%, 5% and 10% levels, respectively.

We set cut-off points at the 20 percent and 60 percent control levels because they present commonly used levels of the largest shareholder voting rights (Faccio and Masulis, 2005; André and Ben-Amar, 2010), and because stock paid acquisitions are much more likely to threaten the effective control of the acquirer’s largest shareholder when their voting rights are within this range.

Table 6 shows that we obtain similar conclusions about the non-linear relationship between family control and the percentage of cash payment. We find that the association is positive and statistically significant for an intermediate level of control, while it is negative for a low or a high level of control. Thus it highlights that if for very low or very high equity stake, there no departure from the standard case, but for an intermediate’s one, the control motive in French family firms is so important that it dominates all other drivers of the payment scheme’s decision.

Table 6

Nonlinearities between family control and the cash proportion: Spline function

The estimation is based on a Tobit model. Independent and control variables are those used in table 3. The statistics are based on Huber/White (sandwich estimator) heteroskedasticity-consistent standard errors. ***, ** and * denote significance at the 1%, 5% and 10% levels, respectively.

Additional robustness tests

First, we focus on a large acquisition that it is supposed to have an important impact on capital and ownership structures. We use a subsample of acquisitions, in which the relative size of the deal value to the acquirer’s market value of assets is at least 10%. We repeat our analysis using this subsample, composed of 154 acquisitions, and we find that results are qualitatively unchanged. Second, we used the Harford et al. (2009) model, rather than Kayhan and Titman’s (2007) model, to estimate the target leverage. In contrast to Kayhan and Titman’s (2007) model in which all variables are measured during the prior year, Harford et al. (2009) consider the effect of future year profitability on leverage. They explain that their model allows them to avoid the effect of unexpected profitability on firm’s leverage ratio. We obtain leverage deviations closest to those obtained by Kayhan and Titman’s model. Third, we use alternative measures of leverage. We use long term debt rather than total debt and we use book leverage rather than market leverage. Analysis based on these variables confirms our results. Fourth, we use family cash-flow rights rather than family voting rights. We also use dummy variables for family firms based on different cut-offs (10%, 20% or 25%). We measure family wedge as the difference rather by the ratio of the level of voting rights to the cash-flow rights. Analysis confirms the signs and statistical significance of our results. Finally, we measure differently these independent variables: the Valuation error, cash reserve and RUNUP. We measure cash reserve by scaling cash and cash equivalents by the deal value rather than by the book value of assets. Notice that cash reserve doesn’t seem to have any importance for determining the means of payment. We measure the RUNUP over 2 years prior the acquisition announcement instead prior one year. Nothing in our results changes dramatically.

Conclusion

Merging with another company is certainly a strategic decision and one of the most important decisions to undertake for the CEO and the board of directors. It may underlie the future of the firm. During M&A transactions, the design of a specific payment scheme is related to information asymmetries. The buyer questions the economic value of acquired assets, and the seller questions the future synergy gains. The chosen financial set-up will underpin the split of the gains and risks for each stakeholder. However, all of this has also managerial consequences, since the capital structure of a family acquiring firm must have been actively prepared before the deal to absorb cross-border acquisition essentially paid with cash. Moreover, in case of intermediate equity stake in a family acquiring company, over-leveraging of the new entity will take place after the merger. If some financial flexibility has been relinquished, it will be perhaps more difficult for the resulting firm to face future challenges, or to respond to external shocks like technological discoveries, deregulation, and changes in macroeconomic conditions. Thus, the choice of a means of payment is important because it may constraint future managerial attitude or prospects of the firm. Finally making an acquisition may hinder the financial flexibility of the firm, increases its bankruptcy risk, so the choice of means of payment deserves fine-tuning. But in case of multiple acquisitions, our results show that resorting to equity becomes necessary.

Nevertheless, it is also a risky decision from another point of view, especially for family firms since control conservation is at stake. Choice of means of payment is thus determinant. Using a sample of 265 acquisitions undertaken by French listed firms during 1997-2008, we find that the percentage of cash used in payment is significantly positively associated to family voting rights. This finding indicates that the payment decision is dominated by corporate control motivation. Our analyses show that this relationship is nonlinear, which indicates that control is not a serious concern at low levels of voting rights, then becomes important at intermediate levels, and less important again at very high levels. These findings are different from those of Faccio and Masulis (2005) that indicate a linear relationship for Continental European firms. But as we consider France only, control conservation at intermediate level of ownership seems highly crucial, perhaps because of the specificities of legal system in place. Additional tests show that our results are robust even when we use family cash flow rights rather than voting rights. They are also robust when we use a spline function to study nonlinearity instead of the squared and the cubed value of voting rights. We highlight a strong link between control-enhancing mechanisms and the method of payment. The family wedge is significantly negatively associated to the percentage of cash. This result indicates that families that maintain control of the firm thanks to pyramidal structures and the double voting rule are less averse to dilution of control following a stock payment.

Parties annexes

Appendices

Appendix A. Variable definitions

Appendix B. Predicting target leverage

In this appendix, we present the Kayhan and Titman (2007) model used to predict the target leverage.

Authors estimate a Tobit regression model that regresses the debt ratio on a set of variables that have been suggested in the previous literature as determinants of capital structure (Titman and Wessels, 1988; Harris and Raviv, 1991; Rajan and Zingales, 1995; Hovakimian et al, 2001). To increase the likelihood that causality runs from independent variables to dependent variables, and not vice versa, all independent variables are lagged variables.

Profitability is defined as earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization scaled by total assets. The relation between profitability and leverage is expected to be negative because firms will prefer to finance with internal funds rather than debt (Myers and Majluf, 1984).

Size is defined as the natural logarithm of sales. This determinant is expected to be positively correlated with leverage, since large firms are likely to have greater access to external capital, and a higher debt capacity resulting from greater diversification. Large firms are less prone to bankruptcy.

Tangible assets are defined as net property, plant, and equipment scaled by total assets. This proxy for the collateral ability of the assets is expected to be associated with higher debt capacity. Firms with more tangible assets can more easily use their assets as collateral for loans, diminishing the risk of the lender suffering the agency costs of debt.

Market-to-book ratio compares a company’s current market price to its book value. The highly levered firms are more likely to suffer from underinvestment problems. Therefore, these firms are characterized by high growth opportunities. A higher market-to-book ratio indicates that a firm has larger growth opportunities, and is expected to be negatively correlated with leverage.

Research and development expenses are divided by sales is an indicator for the uniqueness of the firm’s products. Customers, workers and suppliers of firms that produce unique or specialized products probably suffer high costs in the event that they liquidate (Titman and Wessels, 1988). Moreover, firms with higher R&D expenses are expected to have larger growth opportunities and drive a greater proportion of their value from intangible assets (Harford et al, 2009). The R&D expenses are expected to be negatively correlated to firm’s leverage. We set missing values to zero.

Dummy variable for research and development equals one for firms with missing R&D expenses and zero otherwise.

Selling expenses divided by sales is also an indicator for the uniqueness of the firm’s products. Therefore, it is expected to be negatively correlated to debt levels.

Industry dummies allow to control for other firm characteristics that could be common to firms in a particular industry. These dummy variables correspond to the 17 industries classified by Fama and French (1997).

Appendix C. The residual income model

As Chemmanur et al. (2009), we implement the residual income model following the set-up used by D’Mello and Shroff (2000) and Jindra (2000). Firm value is determined as the sum of its book value and discounted future earnings in excess of a normal return on book value.

B0: The book value of equity per share at the end of the fiscal year in which the acquisition was announced;

EPS : the earnings per share;

r : The required rate of return on the acquirer’s equity. We measure as the firm-specific rate of return, obtained from the market model with beta calculated over 251 trading days ending on the 11th trading day before the acquisition announcement. The risk-free rate is the annualized one-month EURIBOR rate in the month preceding the acquisition announcement. The market risk premium is the annualized average difference between the rate of return on the SBF 250 value-weighted index and the one-month EURIBOR rate over thirty-six months before the acquisition announcement.

TV : The terminal value and is calculated as follows:

If the terminal value is negative, Chemmanur et al. (2009) recommend setting it equal to zero because managers are unlikely to keep making negative NPV investments forever. The terminal value is calculated as an average of residual earnings in years 2 and 3 to avoid the effect of a possible unusual performance in year 3.

To measure the intrinsic value of acquirer’s shares, we suppose that the required rate of return (across firms) is a constant of 13% in robustness checks tests.

Biographical notes

Houssam Bouzgarrou is currently an Associate Professor of finance at Manouba University (Tunisia). He was previously an Assistant Professor at Rennes 1 University (France). His research interests are M&A, corporate governance and banking. He obtained a Ph.D from Rennes 1 University. He has published several articles in international journals (International Review of Financial Analysis; International Journal of Business and Finance Research; Journal of applied Business Research; Bankers, Markets and Investors; Recherches en Sciences de Gestion). He can be contacted at: Department of Accounting and Finance, High Institute of Accounting and Business, Manouba University, Campus Universitaire, 2010 la Manouba, Tunisia.

Patrick Navatte is currently a Full Professor of finance at IGR/IAE of Rennes, University of Rennes 1. He is a member of UMR CNRS 6211 CREM. He is a member of AFFI (French Finance Association). He has published several articles in international journals (International Review of Financial Analysis; European Financial Management; European Finance Review; Finance Letters; Finance; Bankers, Markets and Investors; Revue des Sciences de Gestion; Revue Française de Gestion).

Notes

-

[1]

During the period 1997 – 2008, 131 of the acquirers realized only one acquisition. However, 1. firms realized two acquisitions, 24 completed three deals, 6 completed four deals and 2 realized five acquisitions.

-

[2]

Amemiya (1984) show that the Tobit estimation eliminates biases associated with OLS regressions in the presence of a censored dependent variable.

-

[3]

We consider as family blockholder, an individual or a group of individuals that appertain to the same family.

-

[4]

If family A owns 60% of direct cash-flow of B and B owns 30% of direct cash-flow of C, family A owns ultimately 60%×30% = 18% of cash-flow of C.

-

[5]

Welch (2004) recommends using a market value-based debt ratio in the context of trade-off theory, and a book value-based debt ratio in the context of pecking order theory.

-

[6]

To check the robustness of our results, we consider the stock price three-day before the announcement date. Results are qualitatively unchanged.

-

[7]

This variable also allows to control for timing effects whereby acquirers would be more likely to pay with equity following an abnormal run-up in their stock price (Harford et al, 2009).

-

[8]

Since there are one or more shareholders that hold voting rights similar to the family considered as the largest shareholders, Barontini and Caprio (2006) conclude that the corporation may be thought of as being controlled by a coalition more by than the family.

Bibliography

- Amemiya, T. (1984). Tobit models: A survey. Journal of Econometrics, 24, 3–61.

- Amihud, Y., B. Lev, and N. Travlos (1990). Corporate control and the choice of investment financing: The case of corporate acquisitions. Journal of Finance, 45, 603–616.

- Anderson, R., S. Mansi, and D. Reeb (2003). Founding-family ownership and the agency cost of debt. Journal of Financial Economics, 68, 263–285.

- André, P., and W. Ben-Amar (2010). Family control and financing decisions in mergers and acquisitions. Working Paper, IFSAM.

- Andres, C. (2011). Family ownership, financing constraints and investment decisions. Applied Financial Economics, 21, 1641–1659.

- Bach, L. (2010). Why are family firms so small? Theory and evidence from France. Working Paper, Stockholm School of Economics.

- Barbopoulos, L., Paudyal K., and G. Pescetto (2012). Legal systems and gains from cross-border acquisitions. Journal of Business Research, 65, 1301-1312.

- Barontini, R., and L. Caprio (2006). The effect of family control on firm value and performance: Evidence from continental Europe. European Financial Management, 12, 689–723.

- Basu, N., L. Dimitrova, and I. Paeglis (2009). Family control and dilution in mergers. Journal Banking and Finance, 33, 829–841.

- Burkart, M, Panunzi F, and A. Shleifer (2003). Family firms. Journal of Finance, 58, 2167-2201.

- Caprio, L., E. Croci, and A. Del Giudice (2011). Ownership structure, family control, and acquisition decisions. Journal of Corporate Finance, 17, 1636–1657.

- Chang, S., and E. Mais (2000). Managerial motives and merger financing. The Financial Review, 35, 139–152.

- Chemmanur, T. J., I. Paeglis, and K. Simonyan (2009). The medium of exchange in acquisitions: Does the private information of both acquirer and target matter? Journal of Corporate Finance, 15, 523–542.

- Chevalier A, Redor E, (2010). The determinants of payment method choice in cross-border acquisitions. Bankers, Markets and Investors, 106, 4 – 14.

- Claessens, S., S. Djankov, and L. H. P. Lang (2000). The separation of ownership and control in East Asian corporations. Journal of Financial Economics, 58, 81–112.

- D’Mello, R., and P. Shroff (2000). Equity undervaluation and decisions related to repurchase tender offers: An empirical investigation. The Journal of Finance, 55, 2399–2424.

- Ellul, A. (2009). Control motivations and capital structure decisions. Working paper, Indiana University.

- Faccio, M., and L. H. P. Lang (2002). The ultimate ownership of Western European corporations. Journal of Financial Economics, 65, 365–395.

- Faccio, M., and R. W. Masulis (2005). The choice of payment method in European mergers and acquisitions. Journal of Finance, 60, 1345–1388.

- Fama, E. F., and K. R. French (1997). Industry costs of equity. Journal of Financial Economics, 43, 153–193.

- Franks, J., C. Mayer, P. Volpin, and H. F. Wagner (2012). The life cycle of family ownership: International evidence. Review of Financial Studies, 25, 1675–1712.

- Ghosh, A., and P. Jain (2000). Financial leverage changes associated with corporate mergers. Journal of Corporate Finance, 6, 377–402.

- Ghosh, A., and W. Ruland (1998). Managerial ownership, the method of payment for acquisitions, and executive job retention. Journal of Finance, 53, 785–798.

- Graham, J. R. (1996). Debt and the marginal tax rate. Journal of Financial Economics, Vol. 41, pp. 41–73.

- Hansen, R. G. (1987). A theory for the choice of exchange medium in mergers and acquisitions. Journal of Business, 60, 75–95.

- Harford, J. (1999). Corporate cash reserves and acquisitions. Journal of Finance, 54, p 1969–1997.

- Harford, J., S. Klasa, and N. Walcott (2009). Do firms have leverage targets? Evidence from acquisitions. Journal of Financial Economics, 93, 1–14.

- Harris, M., and A. Raviv (1988). Corporate control contests and capital structure. Journal of Financial Economics, 20, 55–86.

- Harris, M., and A. Raviv (1991). The theory of capital structure. Journal of Finance, 46, 297–355.

- Hovakimian, A., T. Opler, and S. Titman (2001). The debt-equity choice: An analysis of issuing firms. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 36, 1–24.

- Jindra, J. (2000). Seasoned equity offerings, overvaluation, and timing. Working Paper, Ohio State University.

- Kayhan, A., S. and Titman (2007). Firms’ histories and their capital structures. Journal of Financial Economics, 83, 1–32.

- La Porta, R., F. Lopez-de-Silanes., A. Shleifer, and R. Vishny (1997). Legal determinants of external finance. Journal of Finance, 52, 1131–1150.

- La Porta, R., F. Lopez-de-Silanes, and A. Shleifer(1999). Corporate ownership around the world. Journal of Finance, 54, 471–517.

- Lantin F, (2012). « Les effets de la notation financière sur les stratégies d’internationalisation des firmes multinationales européennes » Management international, vol 17, N°1, 25-37.

- Leary, M. T., and M. R. Roberts (2005). Do firms rebalance their capital structure? Journal of Finance, 60, 2575–2619.

- Linn S C, Switzer J A, (2001). Are cash acquisitions associated with better post combination operating performance than stock acquisitions? Journal of Banking and Finance, 25, 1113 - 1138,

- Mackie-Mason, J. K. (1990). Do taxes affect corporate financing decisions? Journal of Finance, 45, 1471–1494.

- MacKinnon, J. G., and H. White (1985). Some heteroskedasticity consistent covariance matrix estimators with improved finite sample properties. Journal of Econometrics, 29, 53–57.

- Martin, K. J. (1996). The method of payment in corporate acquisitions, investment opportunities, and management ownership. The Journal of Finance, 51, 1227–1246.

- Martynova M, and L Renneboog (2009). What determines the financing decision in corporate takeovers: cost of capital, agency problems, or the means of payment. Journal of Corporate Finance, 15, 290-315.

- Myers, S. C., and N. S. Majluf (1984). Corporate financing and investment decisions when firms have information that investors do not have. Journal of Financial Economics, 13, 187–221.

- Ohlson, J. (1990). A synthesis of security valuation theory and the role of dividends, cash flows, and earnings. Contemporary Accounting Research, 6, 648–676.

- Rajan, R. G., and L. Zingales (1995). What do we know about capital structure? Some evidence from international data. Journal of Finance, 50, 1421–1460.

- Rhodes-Kropf, M., D.T. Robinson, and S. Viswanathan (2005). Valuation waves and merger activity: The empirical evidence. Journal of Financial Economics, 77, 561–603.

- Shleifer, A. (2000). Inefficient markets: An introduction to behavioural finance. Working Paper, Oxford University Press.

- Shleifer, A., and R. Vishny (1986). Large shareholders and corporate control. Journal of Political Economy, 94, 461–488.

- Shleifer, A., and R. Vishny (2003). Stock market driven acquisitions. Journal of Financial Economics, 70, 295–311.

- Sraer, D., and D. Thesmar (2007). Performance and behavior of family firms: Evidence from the French stock market. Journal of the European Economic Association, 5, 709–751.

- Stulz, R. M. (1988). Managerial control of voting rights: Financing policies and the market for corporate control. Journal of Financial Economics, 20, 25–54.

- Titman, S., and R. Wessels (1988). The determinants of capital structure choice. Journal Finance, 43, 1–19.

- Uysal, V. B. (2011). Deviation from the target capital structure and acquisition choices. Journal of Financial Economics, 102, 602–620.

- Welch, I. (2004). Capital structure and stock returns. Journal of Political Economy, 112, 106–131.

- Yook, P., P. Gangopaddhayay, and G. M. McCabe (1999). Information Asymmetry, Management Control and the method of payment in acquisitions. Journal of Financial Research, 22, 413–427.

Parties annexes

Notes biographiques

Houssam Bouzgarrou est actuellement un Maitre-Assistant en finance à l’université de la Manouba (Tunisie). Il était auparavant un ATER à l’université de Rennes 1 (France). Ses thématiques de recherches sont les opérations de F&A, la gouvernance et les firmes bancaires. Il a obtenu un doctorat de l’université de Rennes 1. Il a publié plusieurs articles dans des revues internationales (International Review of Financial Analysis; International Journal of Business and Finance Research; Journal of applied Business Research; Bankers, Markets and Investors; Recherches en Sciences de Gestion). Il peut être contacté à : Département comptabilité et finance, Institut Supérieur de Comptabilité et d’Administration des Entreprises, Université de la Manouba, Campus Universitaire, 2010 la Manouba, Tunisie.

Patrick Navatte est actuellement un Professor de finance à l’IGR/IAE de Rennes, Université de Rennes 1. Il est membre de l’UMR CNRS 6211 CREM. Il est membre de l’AFFI (Association Française de Finance). Il a publié plusieurs articles dans des revues internationales (International Review of Financial Analysis; European Financial Management; European Finance Review; Finance Letters; Finance; Bankers, Markets and Investors; Revue des Sciences de Gestion; Revue Française de Gestion).

Parties annexes

Notas biograficas

Houssam Bouzgarrou es Profesor Asistente en Finanzas en la Universidad de la Manouba (Túnez). Anteriormente, se desempeñó como ATER en la universidad de Rennes 1 (Francia), la misma en la que obtuviera su doctorado. Los temas de sus investigaciones son, entre otros, las operaciones de F&A, la gobernanza y las firmas bancarias. Ha publicado numerosos artículos en revistas internacionales (International Review of Financial Analysis; International Journal of Business and Finance Research; Journal of applied Business Research; Bankers, Markets and Investors; Recherches en Sciences de Gestion). Se lo puede contactar en: Département comptabilité et finance, Institut Supérieur de Comptabilité et d’Administration des Entreprises, Université de la Manouba, Campus Universitaire, 2010 la Manouba, Túnez.

Patrick Navatte se desempeña como Profesor de finanzas en el IGR/IAE de Rennes, Université de Rennes 1, Francia. Es miembro del UMR CNRS 6211 CREM así como de la AFFI (Asociación Francesa de Finanzas). Ha publicado numerosos artículos en revistas internacionales (International Review of Financial Analysis; European Financial Management; European Finance Review; Finance Letters; Finance; Bankers, Markets and Investors; Revue des Sciences de Gestion; Revue Française de Gestion).

Liste des tableaux

Table 1

Summary statistics

Family firm is determined when an individual or a family controls more than 51% of voting rights, or controls more than double the voting rights of the second largest shareholder. Market Value is measured at the end of the fiscal year preceding the acquisition. Blockholder Cash-flow is holdings of the ultimate blockholder. Blockholder Voting Rights is voting rights held by the ultimate blockholder. Blockholder Wedge is the difference between the ultimate blockholder’s voting rights and cash-flow rights. Leverage Deviation is the acquirer’s market leverage minus its target market leverage estimated using Kayhan and Titman’s (2007) model, one year prior the acquisition. Induced Change in Target leverage is the change in target market leverage from year -1 to +1 around the acquisition. Average Leverage is the three-year average market leverage, before the acquisition. Bankruptcy Risk Score is Mackie-Mason’s (1990) modified version of the Altman-Z score: total assets divided by (3.3 EBIT + sales + 1.4 retained earnings + 1.2 working capital). Cash Reserve is cash and cash equivalents divided by book value of assets. Valuation Error is the acquirer under- or overvaluation estimated based on Chemmanur et al. (2009) recommendations. RUNUP is the cumulative abnormal return over the year proceeding the acquisition announcement month. Market-to-Book ratio is measured one year prior the acquisition. Cash Proportion is the percent of cash used in payment. Relative Deal Size is the deal value divided by the market value. Unlisted Target is a dummy variable equal to 1 if target is a unlisted firm and 0 otherwise. Cross Border is a dummy variable equal to 1 if the target is not a French firm, and 0 otherwise. ***, ** and * denote significance at the 1%, 5% and 10% levels, respectively.

Table 2

Determinants of the cash proportion used in acquisition’s payment

Family Vote is voting rights held by the family. Family Wedge is the ratio of the family voting rights to the family cash-flow rights. Leverage Deviation is the acquirer’s market leverage minus its target market leverage estimated using Kayhan and Titman’s (2007) model, one year prior the acquisition. Induced Change in Target leverage is the change in target market leverage from year -1 to +1 around the acquisition. Average Leverage is the three-year average market leverage, before the acquisition. Bankruptcy Risk Score is Mackie-Mason’s (1990) modified version of the Altman-Z score: total assets divided by (3.3 EBIT + sales + 1.4 retained earnings + 1.2 working capital). Cash Reserve is cash and cash equivalents divided by book value of assets. Valuation Error is the acquirer under- or overvaluation estimated based on Chemmanur et al. (2009) recommendations. RUNUP is the cumulative abnormal return over the year proceeding the acquisition announcement month. Market-to-Book ratio is measured one year prior the acquisition. Cash Proportion is the percent of cash used in payment. Relative Deal Size is the deal value divided by the market value. Unlisted Target is a dummy variable equal to 1 if target is a unlisted firm and 0 otherwise. Multiple Acquirer is a dummy variable equal 1 if acquirer makes at least three acquisitions between 1997 and 2008. Cross Border is a dummy variable equal to 1 if the target is not a French firm, and 0 otherwise. The estimation is based on a Tobit model. Year dummies are added in the regressions to account for macroeconomic changes in the time series. The statistics are based on Huber/White (sandwich estimator) heteroskedasticity-consistent standard errors. ***, ** and * denote significance at the 1%, 5% and 10% levels, respectively.

Table 3

Cash proportion: a non linear function of family control