Résumés

Abstract

This essay explores the nineteenth-century development of pilgrimage to authors’ houses and locales in light of British and American regionalism and literary reception. It focuses on the trope of “author country” in the celebrated careers and commemoration of Longfellow and the Brontës, and examines American “homes and haunts” books that represent ritual visits to these different authors. Various representations and sites, including portraits, statues, waterfalls, and houses, mark the indigenous qualities of national literature and international attractions.

Corps de l’article

The front page of the “Careers” Section of The Chronicle of Higher Education on 11 August 2006 printed a pseudonymous confession: a professor recalls the thrill he felt in the Harvard archives when he was “permitted to run [his] hand through the beard of Walt Whitman” (Benton C1). That a tenured English professor allows himself to confess to going on pilgrimages under the veil of a pseudonym may reflect on our profession’s disavowal of such commonplace motives. After all, pilgrimage may be “some kind of universal human instinct” that moves members of any social body (C4).[1] It seems a little embarrassing that an academic should be excited by intimacy with the hairs of a poet’s beard preserved in a plaster death mask.[2] Yet I suggest that literature professors would have very little inheritance were it not for such things as death masks; professional critics descend from such forebears in literary trade as autograph-collectors, spirit-rappers, and pilgrims to Whitman’s Camden haunts who wrote of their travels. Our theories suppress author-worship, but many critical books and course syllabi might be elegies to the heroic dead. I’m struck by how much our canons depend on practices associated with pilgrimage.

The same period that codified professional authorship and academic studies of national literatures saw the rise of both spiritualism and literary tourism.[3] Like other forms of pilgrimage, tours of literary shrines answered to spectators’ demands for a mixture of entertainment and self-improvement at the thresholds of mortality.[4] In the later decades of the nineteenth century, volumes of “homes and haunts” capitalized on developments in travel, publishing, education, and leisure, serving as travel memoirs, guidebooks, and albums of literary portraiture and criticism. From the 1890s, literary house museums and author societies were founded in significant numbers, notably in England with an influx of American dollars. Both British and North American constructions of national culture and landscape relied on itineraries—printed as well as performed—of re-collection, at once rooted in specific times, places, and personalities and exchangeable in an international trade.[5] Inevitably, the homeland of English literature at first drew more pilgrims than the relatively unmarked landscapes of the New World, but as more North Americans participated in the invention of author country in England, they also developed literary landmarks and haunts at home.

Any imagined community gains substance from a heritage that may be revisited. The audience response to writers (as well as other famous figures) marks places as attractions—as in Dean MacCannell’s semiotic model, “a relationship between a tourist, a sight, and a marker” (41). A registered literary site may by prompted by an accessible, intact house; a much-described, painted, or photographed landscape or cityscape; plaques or gravestones marking birth, residence, or burial; statues or images not only of the author but also of characters or places in the works; and of course the texts representing past and prescribing future tours. The pilgrim returns to the site as if invited to participate in the act of creation that put it on the map: to improvise a familiar narrative, interweaving episodes of the author’s life, scenes or lines written or set there, and traditions of previous pilgrimages.[6] The uncanny effects associated with literary pilgrimage are overdetermined by the disembodied voices of texts, the reanimation of traces of the past, the transgression of spatial boundaries of home and homeland, and other causes. While the hallucinations of author country derive from classical poetic convention, the tourist industry and the Internet have only increased the influence of literary personalities as genii loci haunting their homes and permeating their regions or cities, stamping their names on maps and characterizing the national culture (Griswold).

Government and nonprofit agencies as well as publishing and hospitality industries—and I would argue, academic experts—share an investment today in preserving and replicating the aura of such haunting. Yet during most of the twentieth century literary scholarship seems to have turned its back on the crowd as it demoted regionalism and denied the commercial aspects of the most worthy literature. This is not to say that all criticism written by professors of English avoided the veneration of authors as ancestors rooted in place, but that their pilgrimages sought to be pure of profit or entertainment motives. And canonicity was conceived of as the opposite of provinciality, as great writers were said to transcend their particular historical and geographical context. On the contrary, the reception of any writer still eminent today is likely to reveal aspects of a local saint’s cult or fan club, just as pilgrimages of the faithful have always served trade and international relations.

How regionalism, associated with nostalgia for the rural past or collective origin (Wilson x-xii; Miller 2-5), inspires both nationhood as an aggregate of internal differences and international relations is a matter for much more exploration.[7] Similarly, the interrelations among literary historiography, the Gothic, and spiritualism deserve as much consideration as the economic transactions of literature have received in recent decades.[8] In this essay, I focus on literary pilgrimage and regional haunting in a transatlantic frame. I will pursue the trope of “author country” in the extraordinary international celebrity of Longfellow, the Brontës, and their respective places, and illustrate transatlantic pilgrimage through various examples of American “homes and haunts” books, particularly those by Elbert Hubbard and Theodore F. Wolfe. Other examples of renowned writers and published pilgrims would serve as well, though each situation is unique. (Given the greater public and scholarly interest in the Brontës than in Longfellow through several generations, I will examine the poet’s context more thoroughly than that of the novelists.)

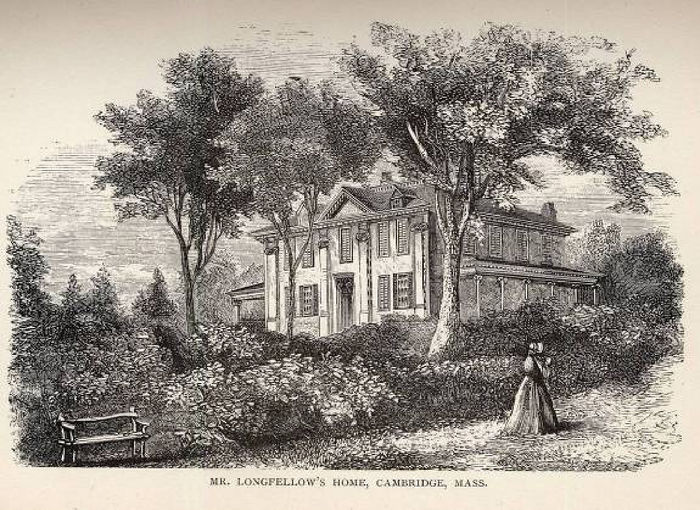

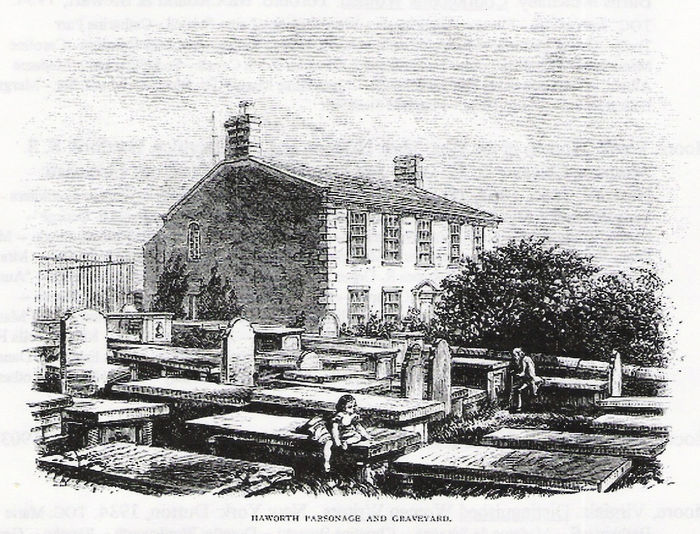

Much could be made of the differences between Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, a male poet in the American context, and Charlotte, Emily, and Anne Brontë, women novelists in Britain. But rather too much has been made, in literary studies, of the transatlantic divide if not those of gender and genre. A thorough comparison of these examples of author country and pilgrimage would have to take into account the irregular behavior of literary reception in light of changing tastes and events. These writers never met—Longfellow’s visits to England bracketed the short years of the Brontës’ careers—and there is no sign of influence (although Longfellow did read their novels [Wagenknecht 21]). Yet in distinctive ways Longfellow and the Brontës created landmarks that drew experts and devotees alike. They afforded the British and North American publics a sense of regional place as a vanishing heritage that nevertheless could be found at the end of a convenient journey in the present. Both locations sampled the distinct flavors of their regions and hence added to a national menu—a sense of the United States and Britain as encompassing all internal variations—but at the same time these sites were hospitable to a cosmopolitanism at home anywhere. In both cases, named waterfalls, featured buildings, statues, movies or websites provide the appropriate marking of an attraction. Most prominently, the houses where these writers lived and died have become museums. My first beaten track is to the Vassal-Craigie-Longfellow House, run by the National Park Service since 1972, and restored and rededicated in 2002 (figure 1). My second leads to the Brontë Parsonage Museum established in 1928 (figure 2). These and similar images of both houses recurred in numerous publications about visits to the authors’ vicinity; here, the figures outside of the house implicitly locate the reader as a visitor, much as the narrated descriptions of the houses allow a vicarious visit.

Figure 1

[H. Billings], “Mr. Longfellow’s Home, Cambridge, Mass.” from R. H. Stoddard et al, Poets’ Homes: Pen and Pencil Sketches (Boston: Lothrop, 1877) 17; rpt. in Elbert Hubbard, Little Journeys to the Homes of American Authors (New York: Putnam’s, 1896), facing 298.

Figure 2

“Haworth Parsonage and Graveyard.” From Ellen Nussey, “Reminiscences of Charlotte Brontë,” Scribner’s Monthly 2:1 (May 1871): 18–31. [p. 25] Courtesy of Cornell University Library, Making of America Digital Collection. [Making of America,2005, http://cdl.library.cornell.edu/cgi-bin/moa/ (accessed August 10, 2007).]

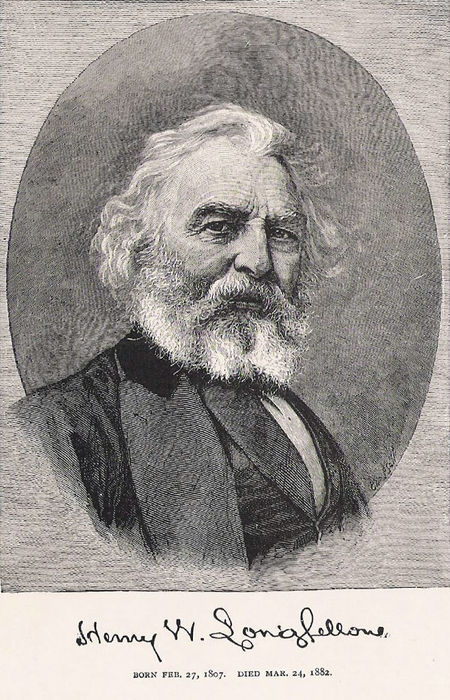

Along with such similarities, the Longfellow and Brontë sites preserve very different spirits or associations with their former occupants. The Craigie or Longfellow house is always impressive but welcoming, with friendly specters in the sunny garden or comfortable study. Some accounts try to endow the house not only with relics of colonial history but with Gothic story elements reminiscent of both Miss Havisham and Bertha Mason: anecdotes of the widowed crone Mrs. Craigie, Longfellow’s landlady when he first moved in, and of his second wife’s gruesome death by fire in 1861.[9] Yet the theme of all sketches of the house is the poet’s “hospitality” and repletion: “as long as the heart of humanity shall beat, his voice will be heard ... singing words of consolation and hope” (Stoddard 15-16). The much smaller and humbler Haworth parsonage, in contrast, is almost unrelievedly Gothic; it both incarcerates the sisters and keeps people out, and it sits in a storm-ridden wasteland: it is purgatory in comparison to Longfellow’s paradise. At one time, Longfellow “country”—a land of refined consolation (“into each life some rain must fall” [Longfellow, “The Rainy Day,” Ballads])—was as settled as the more officially named Brontë Country today—a land of rebellious desolation (“Heaven did not seem to be my home” [Emily Brontë, Wuthering Heights, 82). Longfellow’s life, in spite of its well-known sorrows, was long and richly recognized, producing a portrait industry and a crowded visitors’ book, whereas the Brontës in their brief lives produced a scarcity of portraits, received few visitors, and met only belated fame, mostly for Charlotte. [10] (figure 3) (figure 4). The customs of literary visiting and travel were as much a part of being a writer then as the book tour or poetry reading is today. And yet the Brontë sisters traveled little after Emily and Charlotte returned from Brussels; only Charlotte began to network with Harriet Martineau, Elizabeth Gaskell, and others. Longfellow, in contrast, chose a literary career and set out, as a young college teacher at Bowdoin, on journeys to acquire the languages and cultures of Europe; later in his role as Smith Professor of Modern Languages at Harvard 1834-1854 he was a famous host, guest, and object of pilgrimage (Irmscher 40-41), while the theme of dedicated places pervades his work.

Figure 3

Figure 4

“Charlotte Bronte,” from Evert Augustus Duyckinck, Portrait Gallery of Eminent Men and Women of Europe and America (New York: Johnson, Wilson, 1873) 2: 44. George Richmond’s drawing of Charlotte Brontë (1850) has been engraved and tinted for this gallery, which boasts that it is “illustrated with highly finished steel engravings from original portraits by the most celebrated artists.” See http://nl.wikipedia.org.

Longfellow’s career, set in the rising cultural capital of Cambridge, converted indigenous and colonial sources into polished comparative literature, as if sending down American roots for the sake of cosmopolitan branches. The Brontës in their Yorkshire moors appeared ineluctably provincial, self-taught, as if revealing a wild heart unspoilt by industrialized, imperial Britain. The differences between these writers’ settings have in some respects determined their current respective “places”: what were once cosmopolitan and provincial have now been reversed. Although Longfellow had his contemporary detractors, his supremacy fell sharply after the 1920s (Irmscher 7-23), whereas the Brontë industry steadily increased with the founding of the Brontë Society in 1893 and opening of the parsonage as a museum in 1928. Yet in striking ways, both parties depended on Victorian affinities for regionalism, and continue to serve similar cultural functions. They left indelible imprints on their permanent homes and on their regions, all the more because of the themes of gothic haunting, death, and mourning in their works and biographies. Their renown was transatlantic, as is so often the case in Victorian literary celebrity, and helped to constitute the touring and magazine-buying classes while encouraging publishers such as Lippincott’s, Putnam’s, Longman, Virtue, or Black to produce illustrated books of “pilgrimage.” I will characterize representations of Longfellow Country and Brontë Country before retracing some “homes and haunts” sketches by Hubbard, Wolfe, and others.

Pilgrimage, migration, and sense of place are themes of much of Longfellow’s writing. His first non-scholarly publication was Outre-Mer: A Pilgrimage Beyond the Sea (1833-1835): travels in France, Spain, and Italy in the “antique” style of Washington Irving. While in one sense Longfellow was the bard of New England—rendering America as New England’s land (Calhoun xi)—in another he was an ambassador of cosmopolitan letters and colonial diaspora. His comprehension of the continent, like Washington Irving’s, was polyglot;[11]Evangeline (1847) offered a founding legend of the Francophone Acadians, and The Song of Hiawatha (1855) included transliteration of Native American vocabulary and material from Schoolcraft’s folkloric research (Gorman 274-75). Both works adapt histories of forced migration while exalting a protagonist who possesses transcendent powers, inexhaustible mobility, and deep funds of grief for a dying beloved. The elegiac mode within these romances befits an antebellum sense that both the natural ways of the continent and the promise of the early republic were falling off. Longfellow himself was the opposite of exotic, and avoided self-revelation or the heroic persona of the poet (Irmscher 46-49). Like the Brontë novels with their wild hinterlands of folklore and dialect, however, Longfellow’s works made a nation feel at home by familiarizing it with its own ghosts. Longfellow draws less directly on gothic convention than Irving in “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow,” and he avoids the agitated register of Brontean Romanticism. But his strategy of comfort is not unlike that of Dickensian Christmas ghost stories: the resurgence of dead or dying folkways in the flickering parlor lights of modern middle-class life may spook us into renewed domestic attachments and shared memory. Not only American but British readers wanted what Longfellow represented.

It was patriotic for Americans to love Longfellow, and it was patriotically British to love him as the American poet whose regional difference somehow united an Anglophone world. Working in a tradition of historical narrative that invites readers to tour a foreign place—Scott’s The Heart of Midlothian or Byron’s Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage are fine examples—Longfellow invented regional romances that become fixed in place as history. Long after the cult of Longfellow has faded, and after students have ceased to memorize his poems, the prevalence of the famous works remains.[12] Statues of Evangeline function like saints’ memorials in both Nova Scotia and Louisiana, commemorating Cajun heritage. At Grand Pré in Nova Scotia, she stands before a church,[13] and in Longfellow Evangeline State Park in St. Martinville, Louisiana, she sits above a plaque identifying Emmeline LaBiche (the supposed original “Evangeline,” according to Felix Voorhies’s fictional Acadian Reminiscences [1907]). This figure solidifies layers of representation, including Hollywood film adaptation of historical fiction spun from Longfellow’s poem: the actress Dolores del Rio, who played Evangeline in Carewe’s silent film (1929), posed for the statue and donated it.[14] Although Longfellow, the man and the poetry, has been abstracted in such nominal references, his creations have shaped concrete encounters. A waterfall in Minneapolis is named for the heroine of Hiawatha, Minnehaha (or Laughing Water). In 1913 Helen Archibald Clarke depicted Longfellow’s Country: an illustrated biography of the settings of the poet’s life and works in a somber literary geography that plows Longfellow into American native ground along with George Washington and colonial heritage in general. It duly features Minnehaha Falls.[15] (figure 5). Today, Minnehaha Falls is an attraction in a recreation area along the Mississippi river. As the park’s website affirms, “The New England poet, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, gave a Minneapolis waterfall national fame, but he himself never saw the fifty-three foot falls he wrote of in 1853 [sic]” (National Park Service: Mississippi). Longfellow’s absence is doubly marked at a site he never haunted in life: a two-thirds scale replica of Longfellow’s Cambridge house, built by a Minneapolis entrepreneur Robert F. Jones in 1907 as a novelty for his botanical and zoological park, was moved nearer to the falls in 1994; it serves as the information center for Minnehaha Regional Park (National Park Service: Mississippi).

Figure 5

“The Falls of Minnehaha,” photograph copyright Underwood & Underwood (1909), in Helen Archibald Clarke, Longfellow’s Country (New York: Doubleday, Page, 1913) 200.

In effect, Minnehaha is a Wordsworthian Lucy of the Great Lakes District, whereas Evangeline becomes a blend of saint and Walter Scott heroine. To fix otherwise ubiquitous spirits in one place may be one way to convert terror into fond sentiment; if anyone was victimized, the tribute diffuses the blame, and the audience collaborates in recreating a shared national history. The statues and the waterfall moreover could be seen as a form of “imaginative expansion,” in which audiences adopt the characters in novels “as if they were both fundamentally incomplete and the common property of all,” producing various sequels or reenactments (Brewer 2).[16] The phenomenon of projecting literary figures into the world continues through Pickwick to Sex and the City, but it is not limited to character, nor is it an invention of eighteenth-century reception. The eponymous parks are feats of imagination and apparatuses of regional as well as national imagined community, a form of epideictic rhetoric that organizes social relations through a public exhibit or performance. They fuse the North American practice of naming places with anglicized Native American words; the international custom of commemorating authors through their homes; the trope of marking real counterparts of fictional or poetic settings; and even the regional fancy for scale icons large or small.[17] Clearly, there is nothing specifically postmodern or post-Disney in such rhetorical displays, and it is hardly news that art and religion or any of the highest values and beliefs may turn a profit. In literary pilgrimage the business of tourism and the desire to honor the dead coincide, not so much with dissonance as with an uncanny side-effect.

Longfellow’s animation of the North American landscape follows a longstanding practice in European poetry, as if inviting the reader to eavesdrop on prosopoetic voices in nature. The ventriloquist poet induces readers to imitate this projection of personality into space. The spirit of the text imaginatively inhabits locations where it was conceived or its action was set, and the audience returns to these places to seek an answering inspiration. Accordingly, in Longfellow’s Country (1913), Helen Archibald Clarke recommends “summer pilgrimages” to the New England coast “in company with the poets”; “we may track to their sources the springs of the poet’s fancy—storing our minds with curious or by-gone lore” (3). Preserving both the “country” and the cultural heritage of a people, such reenactments may be performed as if in solitude, but become collective rituals. Gray’s “Elegy in a Country Churchyard” was a classic example of how this might be done, how indeed to see the typical scene of one’s home country (Buzard, Beaten 186-7; Watson 39-47).[18]Hiawatha assumes the pose of Gray’s elegy in its invocation (though its distinctive trochaic tetrameter sounds somewhere between a chant and a ballad):[19]

Hiawatha, Introduction, stanzas 9-10Ye who love the haunts of Nature,

... Ye who love a nation’s legends,

Love the ballads of a people,

... Ye, who sometimes, in your rambles

Through the green lanes of the country,

... Pause by some neglected graveyard,

For a while to muse ... .

All of North America ostensibly provides a country churchyard and thus an open-air museum of the nation’s legends, familiar already from previous iterations. Longfellow himself appeared to haunt America imagined as a New England village, but he also adumbrated the distinctive regions on the continent.[20] British readers perhaps welcomed a poet who spoke their language yet made the foreign accessible.

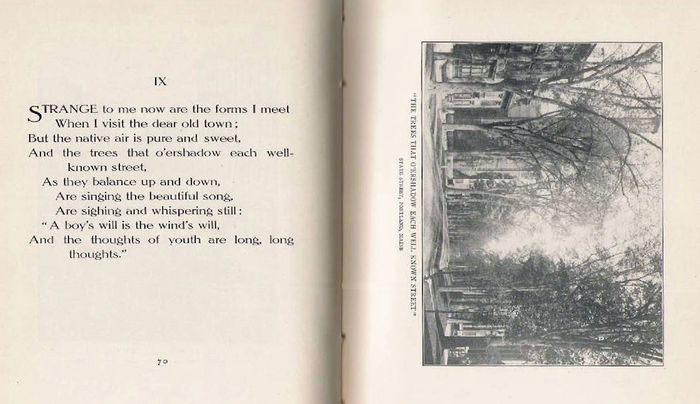

Though his famous long poems invoke the wild, Longfellow also sought to preserve the American small-town past, as in the poem “My Lost Youth,” by revisiting the haunts of his own childhood. George Thornton Edwards in turn frames the poet’s retrospective pilgrimage to Portland, Maine, in a volume published in 1907 on the centennial of Longfellow’s birth, The Youthful Haunts of Longfellow. The “pleasant streets of the dear old town” appear in a series of contemporary photographs to accompany stanzas of “My Lost Youth” (G. Edwards 4) (figure 6). Edwards tries to read every aspect of Portland as a fitting synecdoche of the poet, and typological prophecy is everywhere. “If Longfellow could have had the selection of the place of his birth, he could not have found on either continent a town more delightful ... for his refining” (3). This memorial guide to Portland collects and advertises whatever is “sacred” to the poet’s memory or most “primitive” and unchanged, but it is palpably a nostalgic, fragile construction. The reader repeats the poet’s own sense of belated return as well as his strain to recognize spirit in the mundane. On an earlier return, Longfellow interpreted the rapid transformations of the town as his own: the poem “Changed” begins, “From the outskirts of the town, / Where of old the mile-stone stood, / Now a stranger, looking down / I behold the shadowy crown / Of the dark and haunted wood. / Is it changed, or am I changed?” (G. Edwards 106). Edwards in the poet’s posthumous footsteps observes with dismay that “the birthplace of the poet, which formerly fronted on a beautiful beach is now surrounded by tall grain elevators, tumble down tenements and noisy engines of trade and industry” (113). Still, the reader is invited to “shake off for a few hours the hurry which seems to be innoculated [sic] in all Americans of to-day,” to sit under the oak trees where Longfellow used to sit daydreaming over a book, and to “appreciate more fully the poet’s feelings” (117-18). The town tenuously preserves the way New England used to be as it embodies a generic individual American’s past; the speaker’s pronoun—“am I changed?”—allows for the reader’s identification.[21]

Figure 6

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, “My Lost Youth,” IX, and “The Trees That O’ershadow Each Well Known Street: State Street, Portland, Maine,” in George Thornton Edwards, The Youthful Haunts of Longfellow (Portland, ME: Edwards, 1907) 70-71.

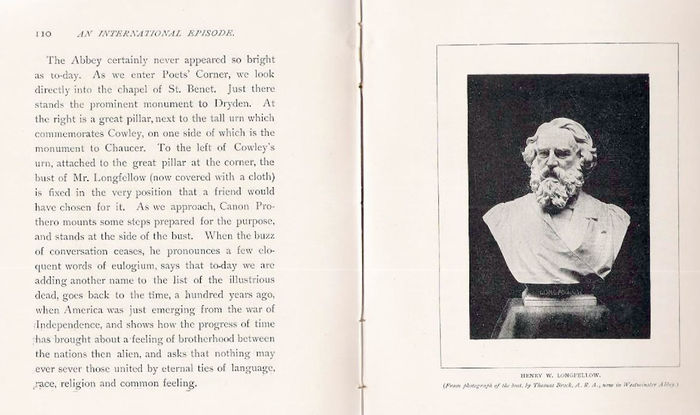

Clearly Longfellow had to leave Portland in order to merit a statue in the city’s “most beautiful avenue,” away from business streets (G. Edwards 3-4). His bildungsroman required that he lose the provincial and become a professor of cosmopolitan letters without forfeiting his native contact with nature. Longfellow’s iconic stature was heightened by his European connections, including his exchange of hospitality with Victorians. He and Dickens traded amicable visits at Craigie House and Gads Hill Place, houses that both signaled their owner’s success and ties to their respective national histories.[22] Longfellow was the guest of both Tennyson and Queen Victoria in 1868-1869 (Calhoun 151; Gorman 308-12). The Illustrated London News in 1869 suggested that Longfellow had more English readers than any living English poet (Wagenknecht 311). In January 1882, Oscar Wilde made a pilgrimage to the ailing Longfellow in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and they laughed together over Victoria’s remark on his fame in England: “O I assure you, Mr. Longfellow, you are very well known. All my servants read you” (Calhoun 3). A bust of Longfellow by Sir Thomas Brock was installed in Westminster Abbey in 1884, a testimony to renewed transatlantic bonds: an inscription reads, “This bust was placed among the memorials of the poets of England by the English admirers of an American poet, 1883” (Longfellow Remembrance Book 102-16; Irmscher 250-51).[23] (figure 7). In 1926 Henry Gorman critically and even sarcastically portrayed Longfellow as A Victorian American who failed in his duty to break free of the Queen’s culture; Longfellow was welcomed in England as an “ambassador,” “the representative of the New World ... as ... a shadow of the Old World and a definite development of kindred ties” (Gorman 313).

Figure 7

From “An International Episode” and “Henry W. Longfellow (From photograph of the bust, by Thomas Brock, A.R.A., now in Westminster Abbey),” Longfellow Remembrance Book: A Memorial for the Poet’s Reader-Friends (Boston: Lothrop, 1888), 110-11.

Gorman’s objection to Longfellow’s shadowy doubling of an English poet reveals the twentieth century’s commitment to a Whitmanesque autogenesis; for earlier audiences, ties to England were no defect. But Longfellow also functioned in his lifetime and after as a representative of the New World. The interior of his house became as familiar as the Oval Office, with particular focus on scenes and objects associated with the act of composition.[24] According to custom, the poet’s birthplace and later home were designated as shrines, insistently national. Today, one can take a virtual tour of Longfellow’s Cambridge house at the National Park Service site (Longfellow National Historic Site). The bust of Washington presides in the entry hall, reminding all that Washington lived here during the War of Independence. Before and after Longfellow’s death, there were public rites of recognition, as when he received honorary degrees at Oxford and Cambridge, or when Portland, Maine held festivities for his seventy-fifth birthday, a few weeks before he died in 1882, and erected a statue to him in 1888. Other signs of respect include an authorized biography in 1886 and centennial celebrations of the class of 1825 at Bowdoin College (where Longfellow and Hawthorne were classmates). In 1910 the Longfellow Memorial Park was built in the existing park between the house and the Charles River, with a bronze bust of Longfellow displayed before a marble bas relief of characters from his works (the memorial, by Daniel Chester French, was dedicated in 1914; see Clarke 242-43). Though still today we find new reifications of Dickens and his literary progeny,[25] the commemoration of Longfellow and his works noticeably dropped off after the First World War. Yet there are signs of revival. The Maine Historical Society is promoting the 200th anniversary of Longfellow’s birth in 2007, much as Yorkshire in 2005 marked the 150th anniversary of Charlotte Brontë’s death (VisitBritain).

Brontë Country is far more heavily promoted than Longfellow Country, with considerably less patriotic emphasis. No critic ever disparaged the Brontës as ambassadors of Victorian culture to the New World, though American publishers and readers snapped up their works. The house where General Washington once resided conveyed an aura of official sanction and prosperity, whereas the parsonage and various schools seem to offer only precarious shelter to the ill-fed, poorly dressed spinsters. Publishers’ neglect, hostile reviews, and controversy are said to have hounded their novels, which have been attacked and praised as full of Chartism and feminist rebellion. In short, the Brontës were mainstream with their international public more as outsiders than insiders. Their victimization and protest might nevertheless appear quintessentially English to the Americans who played a key role in preserving Brontë memorabilia and sustaining the tourist industry that surrounds their former home.[26] England in any case has enfolded the weird sisters in its national canon: a memorial to the Brontës was added to the Poets’ Corner in 1939.

Besides a sentimental documentary, there are many Internet sites entitled “Brontë Country” (Eagle Intermedia); a Brontë Country Partnership, soliciting you to “Find Your Inspiration,” is the main engine of Yorkshire tourism. Just as you can take a virtual tour of Craigie House, you can examine the inside of Haworth parsonage and such locations as Top Withens (supposed prototype of Wuthering Heights) in 360 degrees (Haworth Village). Perhaps your wish to be there is so strong that you are willing to gaze upon live but static images of Haworth streets in all hours and weathers: “you can visit there without moving from your computer keyboard thanks to our ‘Brontecam’” (Brontë Parsonage Museum and Brontë Society). Such solicitation of the sojourner offers an amusing counterpart to the invocation in Hiawatha, “Ye who love the haunts of nature,” or to the instructions in Longfellow’s Country or Longfellow Remembrance Book to read al fresco in a hallowed spot. For 150 years, the disciples of the Brontës have created a storyworld Yorkshire, a living museum for reenacting the novels. Rather than stability and national civilization in Portland or Cambridge, people seek here oppressiveness and wildness, rough equivalents of Longfellow’s Indian or Cajun country—not perhaps incompatible with the melodrama of Victorian repression that they also anticipate. Contemporary Hollywood and the BBC have repeatedly recreated the romance plots if not the Gothic uncanny of the novels (at least fifteen film or video productions of Wuthering Heights alone).[27]

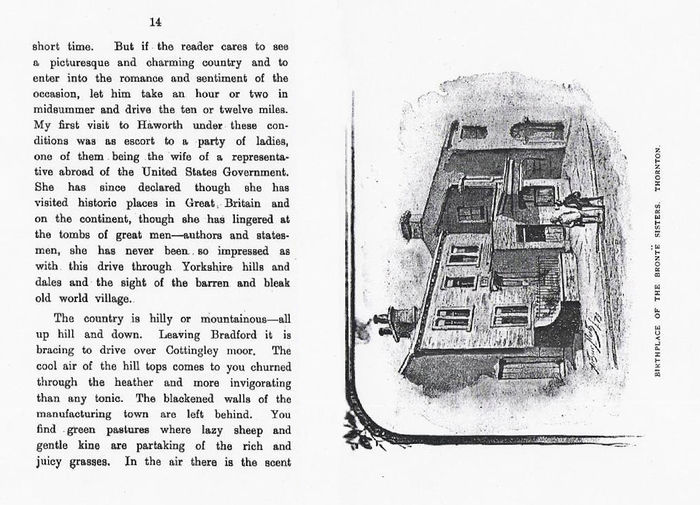

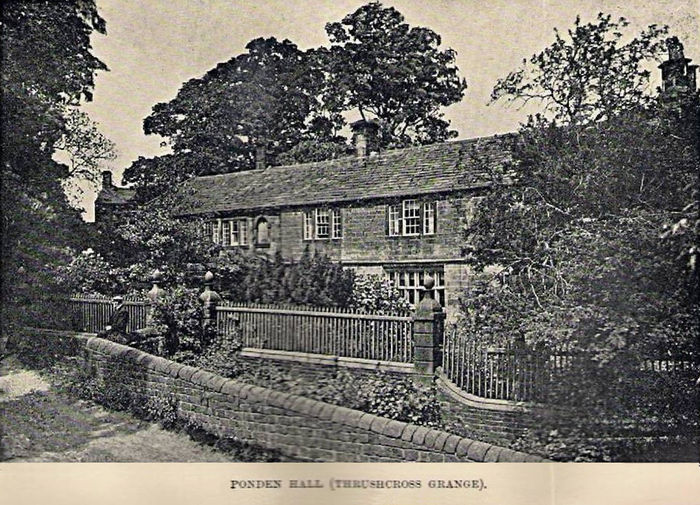

In pilgrimages to Haworth, imagery focuses on the austere house beside the graveyard. Elizabeth Gaskell provided her own sketch of the parsonage, graveyard, and church for the biography of her friend (figure 8). In keeping with the customary marking of writers’ houses, the birthplace of the novelists in Thornton and of their father Patrick Brontë in Ireland are frequently represented but less frequently visited (not fitting into a day in Haworth) (figure 9). But the Brontë legend is exceptional in the degree to which devotees have lodged competing claims not only for authors’ residences but also for the originals of fictional houses. Various buildings large and small, preserved, ruined, or obliterated, provide the supposed incarnations of Thornfield, Ferndean, Wuthering Heights, Thrushcross Grange, and other more or less haunted houses in the novels. From scholarly biographies to celebrity or tourist albums on the Brontës and their “landscape” or “world,” images of these buildings appear to document as well as illustrate the creation of the great works.[28] To offer just one example, a photograph of Ponden Hall appears as an illustration in a 1900 edition of Wuthering Heights as if it were the actual Thrushcross Grange (Emily Brontë) (figure 10). These real places, with their hypothetical authenticity as antecedents to fiction, provide more for the pilgrim to do when in Northern England, while they invite readers to estimate the Brontës as representational artists of the region. A map of the novelists’ sojourns becomes a route for anyone who wants to pursue scholarly or amateur imaginative expansion of the novels, placing Heathcliff here or Shirley there and watching the action play on.

Figure 8

Elizabeth Gaskell, “Haworth Church and Parsonage,” frontispiece vol. 2, The Life of Charlotte Bronte (London: Smith, Elder, 1857). Courtesy of Special Collections, University of Virginia Library.

Figure 9

Claude Meeker, “Haworth; Home of the Brontes,” and Arthur North, “Birthplace of the Brontë Sisters. Thornton,” Bronte Society Publications Part II (Bradford: Treweek, 1895) 14-15.

Figure 10

“Ponden Hall (Thrushcross Grange),” in Emily Bronte, Wuthering Heights, Intro. Mrs. Humphry Ward (New York: Harper, 1900), 46.

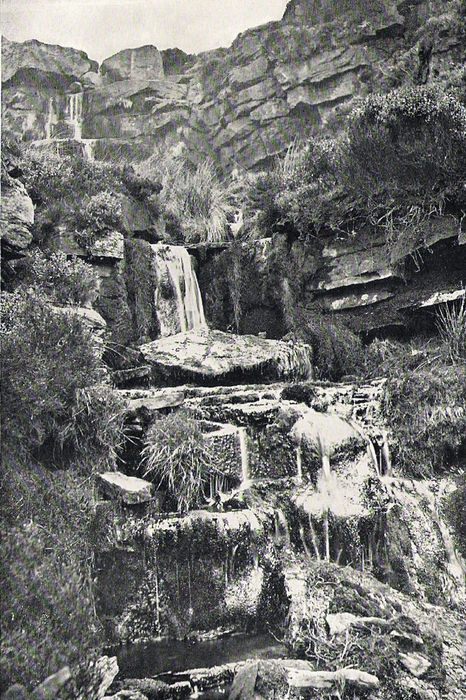

A collective literal-mindedness makes people visit buildings supposedly described in novels or occupied by famous authors, but it goes hand in hand with spiritualist or magical thinking. Not only the homes but the haunts of Yorkshire shape a collective recreation of the sisters, their genius, and the region that inspired it. If the moors made them, then the moors might make us almost in their image, as the walks of the sisters are reenacted by thousands of tourists. One “thing to do” in Haworth is to walk to the Brontë Falls, a rite of touristic remembrance begun by the Brontës themselves, who took their guests there.[29] Photographic impressions of the falls have become standard in editions of the novels, biographies, and guides (figure 11). Though this particular walk may display Nature as only mildly uplifting, the predominant experience sought in the district is sublime or disturbing. Many pilgrims, like one English visitor in 1867, experience Haworth as “wild and gloomy” and somehow lonely in spite of crowds: it “might have been a corner of a desert land in which a lonely colony of adventurers had scooped out a home; and yet it is within four miles of a railway station” and visited by “thousands of pilgrims” (“Winter-Day” 191-92). Americans have managed to make themselves at home in this remote colony: “it will not perhaps surprise those of my readers who know anything of the state of things at Stratford and Abbotsford, to learn that a large number of these [summer] visitors are Americans,” including a notable party of artists, “American ladies and Italian gentlemen,” who “gained an entrance almost by force” to the parsonage, in spite of the present owners’ policy against the constant intrusions (“Winter-Day” 197-99). The slight comedy of the touristic village gives way to the uncanny during this Victorian visitor’s walk on the snowy moors: “a strange, weird, inexpressible influence possessed the mind ... . There was literally the stillness of death over the landscape ... . A sense of something awful and oppressive seemed to hover over the great wilderness. And this spot where we now stood was Charlotte Brontë’s favourite haunt” (“Winter-Day” 201).

Figure 11

“The Bronte Waterfall,” in Emily Brontë, Wuthering Heights (New York: Harper, 1900) 221; rpt. in Elizabeth Gaskell, The Life of Charlotte Bronte (New York: Crowell, 1904).

The Brontës died too young to offer hospitality to many eminent writers the way Longfellow hosted Dickens or Wilde. The sexton sold the eager visitor of 1867 on the idea that there was a sort of transatlantic congress in Haworth Church, when Charlotte Brontë, Harriet Martineau, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and Thackeray worshipped together there one Sunday (“Winter-Day” 194)—in the manner of a conversation painting or an anachronistic tableau of the dead that often illustrates literary canons. But in later decades, a number of famous writers did make their pilgrimage to Haworth a matter of record, from Matthew Arnold to Virginia Woolf and Sylvia Plath. Muriel Spark, in a collection of essays on the Brontës, reprints her BBC TV recording of 1961 in which she attests to being almost “haunted” by Emily Brontë. Spark describes getting lost in the Haworth graveyard, “a sea of stones ... a bit frightening in an enjoyable sort of way ... . I had left my London personality behind me.” Although Spark immediately claims, “I have always resisted the Brontë pilgrim idea,” she envisions the graveyard, in reality not easy to get lost in, as a vast, wild portal to Emily’s vision of “eternity” (314-15).

All the Brontë children were dead by 1855, whereas Longfellow continued to thrive for three more decades. In 1860, a New Yorker could pay a call on Patrick Brontë with Gaskell’s Life of Charlotte Brontë as his guidebook. In 1868, Londoners crowded to catch a glimpse of Longfellow. As the publication of literary pilgrimages gathered momentum, writers sought living authors to visit and interview or gathered mementos of the dead. By 1895, enough North American tourists were hunting literary celebrities to warrant series of “homes and haunts” books, as in Theodore Wolfe’s Literary Shrines[30] or Elbert Hubbard’s Little Journeys to the Homes of Famous People.[31] Hubbard even more than Wolfe established a reputation as an author in turn, and pilgrims sought contact with him at his own haunt, the cooperative craft colony, Roycrofters.[32] Contemporary readers, I suggest, regarded Wolfe’s or Hubbard’s memoirs of literary pilgrimage as works of literature after their kind.

As I have noted, both Hubbard and Wolfe include both Haworth and Longfellow’s house in their narrated tours. The narratives seem bent on rendering “home” and “haunt” synonymous, seeking uncanny yet friendly reanimation through objects and surroundings that their well-traveled fellow-Americans may readily encounter for themselves. Wolfe’s Literary Shrines: The Haunts of Some American Authors, companion to his British pilgrimage, weaves cohorts of authors together by vicinity, marking portions of New England (and Whitman’s Camden, New Jersey) for literary remembrance. “In and Out of Literary Boston” includes a summary, by running title, of literary Cambridge: “Smithy, Chapel, and River of Longfellow’s Verse—Abodes of Lettered Culture—Holmes ... Fuller—Longfellow—Lowell—Longfellow’s City of the Dead and its Precious Graves,” making movement through a locale resemble browsing through the catalogue of a national library or touring a mausoleum. Arriving at “the colonial Cragie [sic] house,” Wolfe recognizes a collective presence of “precious associations” of Washington and of “our popular poet of grace and sentiment.” “The picturesque mansion wears the aspect of an old acquaintance” because of familiarity with what Longfellow had written about it. The objects are doubly and triply relics, as the poet himself preserved and dwelt on nostalgic or literary associations with them. Wolfe inventories the house that when the poet was alive already functioned as both a museum and an autobiographical anthology of poems:

On the entrance door is the ponderous knocker [touched by Washington]; a landing ... holds “The Old Clock on the Stairs” [Longfellow’s famous poem]; at the right of the hall is the study, with its priceless mementos ... . Here is his chair, vacated by him but a few days before he died; his desk; his inkstand which had been Coleridge’s; ... the antique pitcher of his “Drinking Song;” the fireplace of “The Wind over the Chimney;” the arm-chair carved from the “spreading chestnut-tree” of the smithy, which was presented to him by the village children and celebrated in his poem “From my Arm-Chair.” ... From his window we see, beyond the Longfellow Memorial Park, the river so often sung in his verse ... .

107-08

A photograph of Craigie House confirms the continuing existence of the setting that Longfellow’s poetry strove to haunt. The writings instruct later generations to encounter the spirits of “intellectual séances [the house’s] walls have witnessed,” the Dante Club of Lowell, Howells, Fields, et al (108).

Within a year of Wolfe’s textual tour of Cambridge being published in Philadelphia by Lippincott, Putnam’s published in New York the second volume of Hubbard’s Little Journeys series, in fact a reissue of its 1853 collection Homes of American Authors by various authors, incorporating Hubbard’s editorial forewords and his new piece on Whitman (which features various male contemporaries’ rhapsodies on the poet’s “‘perfectly proportioned manliness’” [Hubbard, American Authors 175]). George William Curtis’s 1853 portrait of Longfellow begins by recreating the young professor’s first approach to the Craigie house as a pilgrim, “one calm afternoon in the summer of 1837”; he rents the very room in which Washington slept (Hubbard, American Authors 301-06), before eventually coming to own the house and rival the founding father in eminence. Curtis, like Wolfe and Hubbard in numerous visits to authors’ houses forty years later, features artifacts associated with great men—“the huge, old-fashioned brass knocker” that “Washington touched”—and the vision of the long-dead who already haunt the house: “every room has its poetic passage, every window its haunting face, every garden-path its floating and fading form” (Curtis 299-301). Spiritualism or fairy magic runs through the narrated pilgrimage. Though “no tradition records a ghost in those ghostly chambers” (334), Curtis imagines that Longfellow was greeted by “radiant phantoms” from the colonial days of the house, eager to have a poet portray them in “permanent forms of beauty” (301-02).[33]

The depiction of the same talismanic objects and the same apparitions and anecdotes in various narrated visits to Longfellow’s house suggests how public and representative the poet’s domestic life had become. The piece by Curtis reprinted in Hubbard’s Little Journeys becomes a direct source for a sketch in a collaborative volume, Poets’ Homes by R. H. Stoddard and others (1877), with its frontispiece and opening image of Longfellow, then alive and more than “any living man ... known all over the world ... . His words seem to travel on the swift rays of light that penetrate unto the uttermost parts of the earth.” The publisher (and professional pilgrim) James T. Fields testified to encountering editions of Longfellow in far away places; the poet “has the touch of nature that makes the whole world kin” (Stoddard et al 1). The attraction of the house combines intimacy with an imperial museum;[34] Longfellow is both a personal spirit of home and American nature, and a cosmopolitan communication.[35] Accordingly, this anonymous piece in 1877 portrays the living Longfellow as host (Stoddard et al 14-15), and praises the family for creating a genuine “home. Taste has guided the hand of wealth, and from year to year have been added beauties of art, curiosities from every land, and sacred relics” (6). Again, the visitor imagines “fairies in the flower-cups, and spirits gliding down the shaded walks” from the colonial past. “Sitting in the half-ruined summer-house, I almost wished that ... my soul might pass into the flower growing beside me” (8-9). Such fancy does not distract the writer from itemizing the significant contents of the house, though the sheer quantity of “curiosities” threatens to overwhelm the pilgrimage in a mere “catalogue of description” (11-13). As in the most compelling house museums, the material collection of authentic originals, each associated with some famous person, event, or work of art, vies with the spiritual influence of inhabitants living and dead.

Similar blends of historical empiricism and biographical spiritualism appear in Haworth and the countless recorded pilgrimages to it. Both Theodore Wolfe and Elbert Hubbard include visits to Haworth in their much-reprinted collections of literary pilgrimage, again drawing on haunting associations though without the aura of sweet success that pervades Longfellow’s house. Of course, by the time these American entrepreneurial pilgrims are writing in the 1890s, many visitors and published narratives have prepared the way. Wolfe in A Literary Pilgrimage among the Haunts of Famous British Authors (1895) addresses fellow pilgrims (5) without the slightest sense of venturing into the unknown. “At Keighley our walk begins, and, although we have no peas in our ‘pilgrim shoon,’ the way is heavy with memories of the sad sisters Brontë who so often trod the dreary miles” (121-22), and undoubtedly of Gaskell and later fans. At the famous Black Bull, Branwell’s haunt, Wolfe sleeps “in a bed once occupied by Henry J. Raymond” (123), that is, the New York Times editor who at some time before 1861 befriended Patrick and the widower Nicholls, handled various relics, and was generally “agreeably disappointed” that Haworth was no slough of despond (see Reid). Wolfe instead plays up the melancholy of the place, and marvels that “the genius of a little woman” has converted it into a shrine for “visitors from every quarter of the world” (122), though “most ... come from America” (125). Although Wolfe’s deictics, his repeating “here ... here” and present tense, suggest a tour of the parsonage, his inaccurate layout makes it clear that he was unable to gain entrance.[36] Instead he prowls the countryside—the “dispiriting” “houseless waste” that was nevertheless “a welcome relief from their tomb of a dwelling” (128)—and visits the private museum with its “Brontë mementos” (133).

The irreverent Hubbard offers a different sort of pilgrimage to Haworth in a short, four-part biographical excursion, “Charlotte Brontë,” in Little Journeys to the Homes of Famous Women.[37] After humorous remarks on the self-made clergyman from Ireland, he brings his reader directly to the spot: part II begins, “I got out of the train at Keighley.” Like Wolfe, he alludes to pilgrimage, and provides the expected vision of the dark tower: the way is “rough as the Pilgrim’s Progress road to Paradise” (Hubbard, “Charlotte Brontë,” 131), the village wild and high, of unwelcoming bleak stone. But whereas Wolfe serves the pilgrim spirit straight, Hubbard mocks the inauthenticity of tourism. Identifying himself as “only a tourist in search of the picturesque” (126), he interviews an old clerk in a factory who knew the Brontës, and hangs out with textile workers along the road.

Hubbard is as capable as Wolfe of pretending to know the inside of a writer’s house that he has never entered, but in this case he was more successful. Hubbard receives a tour of the parsonage from the rector’s wife, who while continuing to knit recites her “song”—repeated by Hubbard without quotation marks:

This is Charlotte’s room, this is the desk where she wrote Jane Eyre—leastwise they say it is. This is the chair she sat in, and under that framed glass are several sheets of her manuscript. The writing is almost too small to read; ... She was a wonderful tidy body ... Here are letters she wrote: you can look at them if you choose ...

Those books were hers too—many of them given to her by great authors. See, there is Thackeray’s name written by himself ... . another from Robert Browning—do you know who he was?

138-39

The hostess offers him a sprig of the boxwood “planted by Charlotte’s own hands” (138-39), a customary relic. The final section of Hubbard’s piece belies his ironic disengagement: he indeed worships Charlotte and will cherish that sprig. He disputes the widespread claim that the Brontës’ lives were tragic: “why prate of [Charlotte’s] sorrows! did she not work them up into art?” (144). The wildness of her country fed her genius: “No writer who ever lived has made such splendid use of winds and storm-clouds and driving rain as did Charlotte Brontë” (141). Whereas Longfellow is a universal spirit in an imperial collection that is also the ideal of a peaceful American home, Brontë is a genius in a hermitage who effectively takes over the globe: “From the lonely, bleak parsonage on that stony hillside she sent forth her swaying filament of thought and lassoed the world ... . [A]ll those who reverence the tender heart and far-reaching mind acknowledge her as queen” (143-44).

Sober or insouciant, the American men of letters capitalize on literary travels at home and abroad, helping to confirm the standard canons and routes. The series of pilgrimages by Wolfe and Hubbard ran through several editions as readers vicariously touched the doorknocker that Washington touched at Craigie House, stayed at the Black Bull, Branwell Brontë’s haunt, or brought home a sprig of Charlotte’s own boxwood. A kind of reverse colonization by self-improving Americans may have reinforced the English cultural hegemony as it claimed the hospitality owed to kin (urgently in a period of immigration from Eastern Europe, Asia, or elsewhere). But in such discourses you are enfranchised to travel to literary sites regardless of nationality—or rather, in a naturalized community that spans the Anglophone world. The same British audiences that flocked to Haworth in part because the Americans made it a craze also read of pilgrimages to New England writers and paid their respects at Longfellow’s house if fortune brought them across the Atlantic, or crowded to see him on his last trip to England in 1868. Devotees celebrate the authentically indigenous genius while promoting international recognition. While the collection of Bronteana in Haworth is largely an American achievement, Longfellow’s house is an anthology of American history and international literary relations.

As the parks, house museums, statues, and waterfalls attest, literature effectively marks tourist attractions. Such sites, like the homes and haunts books and websites, deploy epideictic rhetoric that summons readers or potential pilgrims to a collective performance of cultural history. At the same time, they invite imaginative expansion of both biography and fictitious text, as if virtually transposing characters and authors into the same time and place as the pilgrims. Like many forms of serial entertainment, textual and actual pilgrimages dwell on the pleasures of repetition in controlled conditions, the brush with death that is as harmless as the cheerful colonial ghosts at Craigie house. Visitors, intruding on what was once private, feel entitled to the common property of an international public. Yet what they expect is an encounter in author country—as in the root “contrā, against, opposite, lit. that which lies opposite or fronting the view, the landscape spread out before one: cf. the old Pr. Equivalent encontrada, that encountered or met with” (OED Online). Something different that is uncannily familiar may meet you there, some local peculiarity that marks the coherence of the whole, some authentic after-effect of the life or works. The tour is thoroughly charted and booked, but you never know, you might actually get an unbidden chill touching the hair of Whitman’s beard, or—as I did—surprise yourself in tears staring at the horsehair couch on which Emily Brontë is said to have died.

Parties annexes

Biographical Notice

Alison Booth

Alison Booth, Professor of English at the University of Virginia, is the author of Greatness Engendered: George Eliot and Virginia Woolf (Cornell UP, 1992) and How to Make It as a Woman: Collective Biographical History from Victoria to the Present (U Chicago P, 2004; winner of the Barbara Penny Kanner prize). She has edited an essay collection, Famous Last Words: Changes in Gender and Narrative Closure (UP of Virginia, 1993) and the forthcoming Longman Cultural Edition of Wuthering Heights. This essay forms part of a book-length project, “Homes and Haunts: Transatlantic Author Country.”

Notes

-

[1]

Benton’s pseudonym was adopted not only for this topic but also for other eyewitness accounts of academic life. Dean MacCannell was among the first theorists, following Erving Goffman (62), to link tourism to sacred ritual and pilgrimage (42-43); Victorians used the term “pilgrimage” for travel with cultural aims. Arguably all tourism is cultural, though some is ostensibly unrelated to heritage or “culture” (Lennon and Foley 7). On pilgrimage and literary tradition, see Philip Edwards.

-

[2]

Postmodern participant-observers go on ironic sentimental journeys to such sites as Graceland (Marling; see also Vowell), but the result is not a typical scholarly monograph.

-

[3]

The interdependence of these developments warrants consideration beyond the scope of this essay. The best historical and textual study of British literary tourism is Nicola Watson’s The Literary Tourist (2006), but studies of cultural tourism proliferate; see, for instance, Timothy and Boyd, and Robinson and Andersen. The first professor of English was appointed at Harvard in 1876; Oxford had a chair of English literature by 1904 (Parker).

-

[4]

“Graves, tombs, cemeteries and funeral monuments” have served as attractions for all kinds of travelers, in what Tobias Düring calls “necro-tourism” (251, 265). See Anne Trubek. In one perspective, all tourism is “dark,” a kind of controlled experiment in leaving everyday life if not a strategy to improve one’s afterlife (Gitlitz and Davidson 7).

-

[5]

Among the best of an increasing number of studies of place and national memory in Britain and the U.S. are Elizabeth K. Helsinger’s Rural Scenes and National Representation and Cecilia Tichi’s Embodiment of a Nation. The association of places with spirits of the past pervades European Romanticism and Orientalism as well; see Rigby and Smethurst.

-

[6]

Actual visitors may have a wide range of motives and responses, of course. Research, worship, and entertainment readily intersect in literary tourism.

-

[7]

For some recent studies of regionalism in the U.S. or British contexts, see Baker, Duck, McCracken-Flesher, Davis et al., and Buzard, Disorienting. For perspectives on the American investment in literary regional demarcations, laudatory and pejorative, see essays in collections by Wilson as well as Mallory and Simpson-Housley. Canonic status may have excluded the provincial, but it has been readily granted to works stamped with a sense of rural place.

-

[8]

Further studies of literary tourism could amplify an understanding of the interplay of spiritual and economic value suggested in Derridean models of the commodity.

-

[9]

Mrs. Craigie evidently was a blue-stocking given to reading Voltaire (Curtis 307-08); one day Longfellow saw her reading at the open window with the “canker-worms” that were devouring the “stately old trees before the house ... crawling over her dress” and her turban; she replied to his alarm by saying “they are our fellow-worms, and have as good a right to live as we” (310). This scene is associated with an old landlady warning her young male tenant as she lay on her deathbed, “Young man, never marry, for beauty comes to this!” (311) (see also Stoddard, et al., Poets’ Homes 5-6). In 1861, “Mrs. Longfellow was sealing up some curls which she had just cut from the heads of her little daughters. Her thin dress caught fire from a lighted match, and, before her husband could rescue her, she was burned fatally, dying the next morning” (Bolton 86-87).

-

[10]

Julia Cameron’s famous photograph of Longfellow in 1868 may be viewed at various websites, including <http://www.nga.gov/feature/artnation/cameron/biography_3d.htm >.

-

[11]

In 1994 the Longfellow Institute was founded at Harvard to study non-Anglophone literatures of the U.S. (Irmscher 21).

-

[12]

In spite of many grown-up schoolchildren’s quiet revenge of forgetting “The Village Blacksmith,” there are still Longfellow fans who meet at the Wayside Inn to share poetry (<http://www.dlstewart.com/longfellow/CraigieHouse.htm>).

-

[13]

See <http://www.evangeline.ns.ca>, ("Attractions link"), <http://www.gocanada.about.com>, (search for "Nova Scotia"), or <http://www.novascotia.com> ("About Nova Scotia" has "History & Heritage" link).

-

[14]

According to a website, Dolores del Rio donated the statue “after she starred in the motion picture adaptation of Longfellow's Evangeline, filmed in this area in 1929. Sculptor Marcelle Rebecchini used del Rio as his model. Daprato Studios in Chicago, Illinois cast the statue. Del Rio herself inaugurated the work at a gala ceremony in St. Martinville in April, 1931.” See Acadian Memorial, “Area Attractions,” <http://www.acadianmemorial.org/english/area.html 29 August 2006>. See also <http://www.evangelinetrail.com> and <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Acadians>.

-

[15]

Notably this book appeared before the rejection of Victorian taste in the 1920s; it continued the reverential tone of volumes published at the end of Longfellow’s life (see, for instance, Longfellow Remembrance Book 93-94). The title resembles others published in the early twentieth century, such as Kitton’s The Dickens Country and Melville’s The Thackeray Country (both 1905).

-

[16]

Brewer focuses on the theatrical conventions of eighteenth-century British readership, whereby such characters as Lemuel Gulliver or Tristram Shandy continue to perform beyond the original texts.

-

[17]

For example, the giant Peach Water Tower in Gaffney, South Carolina; competing “world’s largest” balls of twine in Darwin, Minnesota and Cawker City, Kansas; a replica of Elvis’s Graceland in Orlando Florida; or the miniature Graceland in which the singer Pink buried her dead dog, Elvis (http://AskMen.com).

-

[18]

The etymology of “country” in the Oxford English Dictionary includes the range from “a region, district,” to “the territory or land of a nation,” to “rural districts” contrasted with urban; its second definition refers to a delimited space associated with a people or a person. It cites in this regard, “1905 F. G. Kitton (title) The Dickens Country.”

-

[19]

Wikipedia’s current entry on “trochee” provides Longfellow’s Hiawatha as defining example.

-

[20]

Stephen Nissenbaum points out the changes in constructions of New England as an American heartland or past, particularly after the Civil War. The supposedly archaic New England village of white houses with a common green in fact developed in the 1830s with the rise of wealthier tradesmen and industrialists, around the beginning of Longfellow’s career (105-08, 110-18).

-

[21]

According to Nissenbaum, prototypical New England used to be Connecticut, but has moved northward to the formerly uncivilized New Hampshire and Maine with industrialization and suburban development (105-06).

-

[22]

Dickens liked to think that Falstaff haunted the highways near Gads Hill (Kitton 184-85, 204; James Fields 212).

-

[23]

Louise Imogen Guiney’s poem, “Longfellow in Westminster,” concludes the Longfellow Remembrance Book. Addressed to the American child visiting the Abbey expecting to “renew the legends” of “monk and knight” learned at “your mother’s knee,” the poem admonishes the tourist to “salute, a-thrill with pride” the image of an exalted poet of purity and faith: “He stands among [England’s] mightiest; / We craved it not, yet be it so.” Clearly it was a coup to get a place in the mother-country’s churchyard. The verse implies that the American poet may not be as great as the English poets but he is morally superior, and England’s “cloistral aisles” are already a kind of historical theme park.

-

[24]

See Samuel Hollyer’s portrait, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow in His Library at Craigie House, Cambridge (1881) (Maine Historical Society); Longfellow in his Craigie House study, mid-1870s (unknown photographer; plate 21, Calhoon [208-09], National Park Service, Longfellow National Historical Site); and images of the study today at Longfellow National Historic Site (<http://lnhstest.brinkster.net/Level2/house/Floor1/Study/Study.htm>). Longfellow RemembranceBook features a table and a desk, among other relics and interiors (91, 99).

-

[25]

Dickens World, an “indoor visitor complex themed around the life, books and times of one of Britain’s best loved authors” in his childhood town, opened 25 May 2007. The site promises time travel and haunting encounters: a visit to the Dikensian world, and lifelike apparitions of characters.

-

[26]

Claude Meeker, the U.S. consul at Bradford, first published “Haworth; Home of the Brontës” in a Cincinnati paper before it appeared in Bradford in 1895. Henry Bonnell, a Philadelphia member of the Society, donated his collection of first editions and manuscripts to the Society; after his death, the collection ensured that the new Parsonage Museum was also a center of scholarship (The Brontë Parsonage Museum and Brontë Society).

-

[27]

Hiawatha became a movie as early as 1903 and as recently as 1997 (about ten versions). Five versions of Evangeline appeared by 1929.

-

[28]

Such documentary illustrations appear in Bentley 94-102; Pollard 124-29 .

-

[29]

An old postcard features the Brontë Falls, Haworth (Keighley Online). Brochure and Guide to Haworth (Yorkshire), 1947, offers a walking tour from the village. “Brontë Waterfall sounds alluring, but the Fall itself is mostly disappointing ... . After heavy rain or sudden thaw the Fall can be decidedly pretty. At its foot is a naturally planted rock ... and this is known as the ‘Brontë Chair,’ this area having been a favourite resort of the gifted sisters.” The reader is then guided to “the direct way to the immortal ‘Wuthering Heights’” ([Preston] 38). An artfully illustrated guidebook first published in 1967 and reissued in 1979 provides both walking tours and advertisements of shops and accommodation (Mitchell).

-

[30]

Wolfe’s Literary Shrines, A Literary Pilgrimage, Literary Haunts and Homes, and Literary Rambles appeared in various editions in Philadelphia and London. Wolfe is identified as “physician and littérateur” and the author of Literary Pilgrimage and Literary Shrines, “two widely popular books,” in Oscar Fay Adams’ 1901 Dictionary of American Authors (433). Adams in turn is noted on the title page as “Author of ‘The Story of Jane Austen’s Life,’ ‘Post-Laureate Idyls,’ etc.; Editor of ‘Through the Year with the Poets,’ etc.” By 1943, Wolfe is omitted from Burke and Howe’s American Authors and Books 1640-1940.

-

[31]

The first Little Journeys volume was published by Putnam’s in 1895; Hubbard serialized the sketches once a month for fourteen years, volumes published or reprinted by Roycrofter’s or by World. The 1928 reprint of the Little Journeys series includes Hubbard as frontispiece in the volume of Good Men and Great, with his biography right before those of George Eliot and Carlyle. Putnam’s published not only Hubbard but a series of literary biographies by Marion Harland capitalizing on the rhetoric of home life that was especially popular in the South after Reconstruction.

-

[32]

The Roycrofters drew in one year as many as “twenty-eight thousand pilgrims ... representing every State and Territory of the Union and every civilized country on the globe,” as he boasted in 1902 (“Autobiographical” xxv).

-

[33]

Eliza Richards discusses the association of “modern spiritualism” in the U.S. with literary respectability, and mentions Longfellow, Oliver Wendell Holmes, and other New England figures as participants (278).

-

[34]

The house features a suite “fitted up by Mr. Longfellow’s son in Japanese style,” with a gallery of photographs of “Japanese beauties” (Stoddard 13).

-

[35]

The writer Annie Fields, James T. Fields’ wife, as late as 1924 published recollections of visiting Longfellow: “this was ... his house beautiful, and such he made it ... . The atmosphere of the man pervaded his surroundings and threw a glamour over everything ... . [an] indescribable influence of tenderness, sweetness, and calm that filled the place” (26). “The poems and journals are full of his enjoyment of nature as seen from its windows” (24).

-

[36]

“Visitors are rarely admitted to the vicarage; among those against whom its doors have been closed is the gifted daughter of Charlottes’s literary idol, to whom ‘Jane Eyre’ was dedicated, Thackeray” (128).

-

[37]

The first part begins, “Rumor has it that there be Americans who are never happy unless passing for Englishmen. And I think I have discovered a like anomaly on the part of the sons of Ireland—a wish to pass for Frenchmen” (117). In cavalier tone, he tells of Patrick’s change of name and garbles some of Gaskell’s myths about the family life (burning pieces of silk dress, firing pistols [122]).

Works Cited

- Adams, Oscar Fay. Dictionary of American Authors. 4th ed. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1901.

- AskMen.com. “Pink’s Doggie Graceland.” 19 January 2007. 3 March 2007 <http://www.askmen.com/gossip/pink/pink-doggie-graceland.html >.

- Baker, Anne. Heartless Immensity: Literature, Culture, and Geography in Antebellum America. Anne Arbor, MI: U of Michigan P, 2006.

- Bentley, Phyllis. The Brontës and Their World. New York: Viking, 1969.

- Benton, Thomas H. “A Professor and a Pilgrim.” Careers. The Chronicle of Higher Education (11 August 2006): C1, C4.

- Bolton, Sarah K. Famous American Authors. New York: Crowell, 1905.

- Brewer, David A. The Afterlife of Character, 1726-1825. Philadelphia: U Pennsylvania P, 2005.

- Brontë Country Partnership. Visit Brontë Country. n.d. <http://www.visitbrontecountry.com>. 3 March 2007.

- Brontë, Emily. Wuthering Heights. New York: Harper, 1900.

- The Brontë Parsonage Museum and Brontë Society. “History.” 25 February 2007. <http://www.bronte.org.uk/ >.

- Burke, W. J. and Will D. Howe. American Authors and Books 1640-1940. New York: Gramercy, 1943.

- Buzard, James. The Beaten Track: European Tourism, Literature, and the Ways to “Culture”, 1800-1918. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1993.

- Buzard, James. Disorienting Fiction:The Autoethnographic Work of Nineteenth-Century British Novels. Princeton: Princeton UP, 2005.

- Calhoun, Charles C. Longfellow: A Rediscovered Life. Boston: Beacon, 2004.

- Clarke, Helen Archibald. Longfellow’s Country. New York: Doubleday, Page, 1913.

- Curtis, George William. “Henry W. Longfellow.” Homes of American Authors. 1853. Rev. ed. Elbert Hubbard, American Authors. Vol. 2 of Little Journeys to the Homes of Famous People. 299-334.

- Davis, Leith, Ian Duncan, and Janet Sorensen, eds. Scotland and the Borders of Romanticism. New York: Cambridge UP, 2004.

- Dickens World. 30 October 2007. <http://www.dickensworld.co.uk>.

- Duck, Leigh Anne. The Nation’s Region: Southern Modernism, Segregation, and U.S. Nationalism. Athens, GA: U of Georgia P, 2006.

- Düring, Tobias. “Travelling in Transience.” The Making of Modern Tourism. Ed. Harmut Berghoff, Barbara Korte, Ralf Schenider and Christopher Harvie. New York: Palgrave, 2002. 249-66.

- Eagle Intermedia. Brontë Country. 2005. 30 October 2007. <http://www.bronte-country.com>.

- Edwards, George Thornton. The Youthful Haunts of Longfellow. Portland, ME: Edwards, 1907.

- Edwards, Philip. Pilgrimage and Literary Tradition. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2005.

- Fields, Annie. “Longfellow.” Authors and Friends. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1924. 3-64.

- Fields, James T. Yesterdays with Authors 1871. Rpt. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1900.

- Gaskell, Elizabeth. The Life of Charlotte Brontë. 2 vols. London: Smith Elder, 1857.

- Gitlitz, David M. and Linda Kay Davidson. Pilgrimage and the Jews. Westport, CT: Praeger, 2006.

- Goffman, Erving. Relations in Public. New York: Basic, 1971.

- Gorman, Herbert S. A Victorian American, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. 1926. Rpt. Port Washington, NY: Kennikat, 1967.

- Griswold, Wendy, and Nathan Wright. “Cowbirds, Locals, and the Dynamic Endurance of Regionalism.” American Journal of Sociology 109 (May 2004): 1411-51.

- Guiney, Louise Imogen. “Longfellow in Westminster.” Longfellow Remembrance Book. 115-16.

- Harland, Marion. Charlotte Brontë at Home. Literary Hearthstones: Studies of the Home-Life of Certain Writers and Thinkers. New York and London: Putnam’s, 1899.

- Haworth Village. 360 Degree Panoramas. 30 October 2007. <http://haworth-village.org.uk>.

- Helsinger, Elizabeth K. Rural Scenes and National Representation: Britain 1815-1850. Princeton: Princeton UP, 1997.

- Hubbard, Elbert. American Authors. Vol. 2 of Little Journeys to the Homes of Famous People. New York: Putnam’s, 1896.

- Hubbard, Elbert. “Autobiographical.” Good Men and Great. Vol. 1 of Little Journeys to the Homes of the Great. Cleveland, OH: World, 1928. xiii-xliii.

- Hubbard, Elbert. “Charlotte Brontë.” Little Journeys to the Homes of Famous Women. Vol. 3 of Little Journeys. New York: Putnam’s, 1897. 115-72.

- Irmscher, Christoph. Longfellow Redux. Urbana, IL: U of Illinois P, 2006.

- Keighley Online. Brontë Falls. Postcard, Lilywhite Ltd., Brighouse. “Old Haworth Postcards.” 30 October 2007. <http://www.keighleyonline.co.uk/art22/>.

- Kitton, Frederick George. The Dickens Country. London: Black, 1905.

- Lennon, John, and Malcolm Foley. Dark Tourism. London: Continuum, 2000.

- Longfellow, Henry Wadsworth. Ballads and Other Poems. Cambridge, MA: Owen, 1842.

- Longfellow, Henry Wadsworth. Hiawatha: A Poem. 1856. Chicago: Reilly & Britton, 1909. University of Virginia Library Electronic Text Center. 2000. 30 October 2007. <http://etext.lib.virginia.edu/toc/modeng/public/LonHiaw.html>. Longfellow Remembrance Book: A Memorial for the Poet’s Reader-Friends. Boston: Lothrop, 1888.

- MacCannell, Dean. The Tourist. 1976. Rev. ed. Berkeley: U of California P, 1999.

- Maine Historical Society. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow in His Library at Craigie House, Cambridge (1881), by Samuel Hollyer. Maine Memory Network. 2007. 30 October 2007. <http://www.mainememory.net/bin/Detail?ln=15907>.

- Mallory, William E., and Paul Simpson-Housley, eds. Geography and Literature. Syracuse: Syracuse UP, 1987.

- Marling, Karal Ann. Graceland: Going Home with Elvis. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 1996.

- McCracken-Flesher, Caroline. Possible Scotlands: Walter Scott and the Story of Tomorrow. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2005.

- Meeker, Claude. “Haworth; Home of the Brontës.” Brontë Society Publications. Part II. Bradford: Terweek, 1895. Rpt. in Transactions and Other Publications of The Brontë Society. Vol. 1, London: Dawson, 1965. 1-44.

- Melville, Lewis [Lewis Saul Benjamin]. The Thackeray Country. London: Black, 1905.

- Mitchell, W. R. Haworth and the Brontës: A Visitor’s Guide. Clapham, N. Yorkshire: Dalesman, 1979.

- National Park Service. Longfellow National Historic Site. 1 February 2007. <http://www.nps.gov/long/>.

- National Park Service.. Mississippi National River and Recreation Area. Minnehaha Regional Park. 20 May 2004. 3 March 2007 <http://www.nps.gov/miss/maps/model/minnehaha.html>.

- Parker, William Riley. “Where Do English Departments Come From?” ADE Bulletin 011 (January 1967): 8-17.

- Pollard, Arthur. The Landscape of the Brontës. Photographs by Simon McBride. Exeter: Webb & Bower/London: Michael Joseph, 1988.

- [Preston, A. H., ed.] Brochure and Guide to Haworth (Yorkshire). N.p., [1947].

- Reid, T. Wemyss. Charlotte Brontë. London: Macmillan, 1877. Rpt. in Early Visitors To Haworth: From Ellen Nussey to Virginia Woolf. Ed. Charles Lemon. Haworth: The Brontë Society, 1996. 66-7.

- Richards, Eliza. “Lyric Telegraphy: Women Poets, Spiritualist Poetics, and the ‘Phantom Voice’ of Poe.” The Yale Journal of Criticism 12 (1999): 269-94.

- Rigby, Kate. Topographies of the Sacred: The Poetics of Place in European Romanticism. Charlottesville, VA: U of Virginia P, 2004.

- Robinson, Mike, and Hans Christian Andersen, eds. Literature and Tourism. London: Continuum, 2002.

- Smethurst, Colin, ed. Romantic Geographies: Proceedings of the Glasgow Conference, September 1994. Glasgow: University of Glasgow French and German Publications, 1996.

- Spark, Muriel. “At Emily Brontë’s Grave Haworth, April 1961. A BBC TV Recording.” Rpt. The Essence of the Brontës. London: Peter Owen, 1993. 314-16.

- Stoddard, R. H. et al. Poets’ Homes: Pen and Pencil Sketches of American Poets and Their Homes. Boston: Lothrop, 1877.

- Tichi, Cecilia. Embodiment of a Nation: Human Form in American Places. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 2001.

- Timothy, Dallen J., and Stephen W. Boyd. Heritage Tourism. Harlow, Essex, England: Pearson, 2003.

- Trubek, Anne. “The Evidence of Things Unseen: The Sweet Gloom of Writers’ House Museums.” Believer Magazine. October 2006. 30 October 2007. <http://www.believermag.com/issues/200610/>.

- VisitBritain. “Yorkshire Marks Charlotte Brontë Anniversary.” December 2004. 3 March 2007 <http://www.visitbritain.com/corporate/presscentre>.

- Voorhies, Felix. Acadian Reminiscences: with the true story of Evangeline. Intro. Andrew Thorpe. New Iberia, La. : Frank J. Dauterive, [1907].

- Vowell, Sarah. Assassination Vacation. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2005.

- Wagenknecht, Edward. Longfellow: A Full-Length Portrait. New York: Longmans, Green, 1955.

- Watson, Nicola. The Literary Tourist: Readers and Places in Romantic & Victorian Britain. London: Palgrave, 2006.

- Wikipedia. “Trochee.” 3 May 2007. 7 May 2007 <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trochee>.

- Wilson, Charles Reagan, ed. The New Regionalism. Jackson, MS: UP of Mississippi, 1998. “A Winter-Day at Haworth” (1867). Chambers’s Journal of Popular Literature, Science, and Art: Fourth Series 217 (22 February 1868): 125-8. Rpt. in The Brontës: Interviews and Recollections. Ed. Harold Orel. London: Macmillan, 1997. 191-205.

- Wolfe, Theodore H. Literary Haunts and Homes: American Authors. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1901.

- Wolfe, Theodore H. A Literary Pilgrimage: Among the Haunts of Famous British Authors. 1895. 10th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1897.

- Wolfe, Theodore H. Literary Rambles at Home and Abroad. Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1901.

- Wolfe, Theodore H. Literary Shrines: The Haunts of Some Famous American Authors. Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1895.

Liste des figures

Figure 1

Figure 2

“Haworth Parsonage and Graveyard.” From Ellen Nussey, “Reminiscences of Charlotte Brontë,” Scribner’s Monthly 2:1 (May 1871): 18–31. [p. 25] Courtesy of Cornell University Library, Making of America Digital Collection. [Making of America,2005, http://cdl.library.cornell.edu/cgi-bin/moa/ (accessed August 10, 2007).]

Figure 3

Figure 4

“Charlotte Bronte,” from Evert Augustus Duyckinck, Portrait Gallery of Eminent Men and Women of Europe and America (New York: Johnson, Wilson, 1873) 2: 44. George Richmond’s drawing of Charlotte Brontë (1850) has been engraved and tinted for this gallery, which boasts that it is “illustrated with highly finished steel engravings from original portraits by the most celebrated artists.” See http://nl.wikipedia.org.

Figure 5

Figure 6

Figure 7

Figure 8

Figure 9

Figure 10

Figure 11