Résumés

Abstract

Graduate student unions are beginning to attract attention in Canada and the United States. In Canada, unionization on campuses is especially important for organized labour, as union density has dropped below 30 percent for the first time in five decades. Graduate student unionization is also important in the wider context of precarious employment in North America. Despite the decline in overall union density, graduate student unions have continued to grow in the past decade. However, there is a paucity of scholarly research in this area. In this article, we trace the historical origins of graduate student unions in Canada, discuss relevant legal concerns, analyze pertinent collective bargaining and strike issues, and suggest avenues for future research.

Résumé

Les syndicats d’étudiants diplômés commencent à capter considérablement l’attention des universitaires et des praticiens en Amérique du Nord. Au Canada, la syndicalisation sur les campus universitaires prend de l’importance dans le monde du travail syndiqué, au moment où la densité syndicale a plongé en bas de 30 % pour la première fois depuis cinq décennies. Entre 1992 et 1997, le membership syndical a perdu 255 000 personnes, une baisse moyenne de 51 000 par année, ce qui représente une perte de 7 % de l’effectif. Malgré le déclin de la densité globale, les syndicats étudiants ont continué à croître au cours de la dernière décennie. Cette propension à se syndiquer peut être reliée à la situation financière critique dans le monde universitaire canadien, qui a à son tour exercée un impact sur les salaires, la charge de travail, les frais de scolarité et possiblement dans l’avenir sur l’endettement des étudiants. Le syndicalisme apparaît alors comme le véhicule permettant graduellement aux étudiants diplômés de faire connaître leurs intérêts.

Par ailleurs, on constate l’inexistence des publications scientifiques sur le syndicalisme chez les étudiants aux études supérieures. En tenant compte de la nature éphémère de ces syndicats, où les étudiants maintiennent leur membership seulement au cours des périodes limitées aux études supérieures, il est alors intéressant de constater qu’ils peuvent créer une préoccupation additionnelle au système de gestion des universités par le recours éventuel à la grève ou au ralentissement des activités. La section locale 3 903 du SCFP (Syndicat canadien de la fonction publique), qui représente le syndicat des étudiants diplômés de l’Université York, fournit un exemple frappant de l’influence d’un tel syndicat à ce niveau. Comme tel, il devient important que des recherches soient réalisées sur la syndicalisation des étudiants diplômés, car leur intérêt à se syndiquer semble se maintenir avec autant d’intensité.

Pour obtenir de l’information et des données sur la syndicalisation des étudiants diplômés, nous avons effectué une revue de la documentation pertinente, une revue de l’information fournie sur les sites Internet des syndicats étudiants, et nous avons interviewé plusieurs représentants des syndicats et des administrations.

Au premier chef, nous avons observé que l’organisation des étudiants diplômés au Canada s’est produite en deux mouvements : les premières sections locales sont apparues dans les universités au milieu des années 1970 en Ontario et en Colombie-Britannique. La deuxième vague s’est produite au cours de la dernière décennie, avec quelques additions dans la période intermédiaire. Les raisons communes aux deux vagues sont de l’ordre des taux de rémunération et de la charge de travail. Des efforts plus récents ont été motivés par des perspectives réduites d’emploi et par des frais de scolarité accrus.

Au Canada, comme elle le prévoit pour d’autres groupes de salariés, la loi permet aux diplômés de s’organiser et de négocier collectivement, une fois qu’ils rencontrent les seuils de support et de communauté d’intérêts au sein des unités d’accréditation. Ces droits ont été reconnus par une décision importante de la Commission des relations de travail de l’Ontario en 1975 dans le cas des assistants diplômés de l’Université de York. Ce cas a pavé la voie à la syndicalisation des assistants d’enseignement en Ontario et dans le reste du Canada.

Avant cette décision, la position du Conseil des gouverneurs de l’Université York était à l’effet que les étudiants diplômés et les assistants d’enseignement ne se qualifiaient pas comme des salariés au sens du Code du travail de l’Ontario. L’université soutenait que les étudiants diplômés qui agissaient comme assistants dans l’enseignement et dans la recherche se retrouvaient dans la même catégorie que les étudiants bénéficiaires de bourses ou de prêts venant de l’université. L’Association des étudiants diplômés soutenait pour sa part que les diplômés qui travaillaient comme assistants d’enseignement ou de recherche constituaient une catégorie distincte parce que le travail qu’ils accomplissaient n’était pas relié à leurs études; par conséquent, les fonds obtenus devaient être considérés comme un salaire. La Commission des relations de travail de l’Ontario déclara que les étudiants diplômés engagés comme assistants d’enseignement et les autres engagés comme tuteurs ou directeurs de cours au Collège Atkinson (le programme du soir de l’université) se qualifiaient comme salariés au sens du Code du travail de l’Ontario, alors que les étudiants diplômés en étaient exclus. Un membre dissident de la Commission se rangea du côté de la décision majoritaire tout en étant d’avis que les assistants diplômés pouvaient aussi se qualifier. Ceci devenait la première décision de ce type au Canada, ouvrant ainsi la voie à la syndicalisation chez les étudiants diplômés à titre de salariés tels que prévu par le Code du travail.

Nous avons également constaté que le taux de syndicalisation varie d’une province à l’autre. Effectivement, les taux sont plus élevés en Nouvelle-Écosse, en Ontario, en Colombie-Britannique et en Saskatchewan; ils le sont moins en Alberta, au Québec et au Nouveau-Brunswick. Dans la dernière partie de cet essai, nous avons élaboré un modèle sous forme de diagramme des antécédents de la syndicalisation des étudiants diplômés et nous avons suggéré des avenues de recherche pour le futur.

Dans le monde syndical, l’organisation de ceux qui ne sont pas syndiqués demeure un enjeu significatif. Par exemple, au SCFP, le travail de syndicalisation est perçu comme vital. En effet, le taux d’attrition est de l’ordre de 5 % par année, par conséquent, il faut recruter autour de 9 000 nouveaux membres chaque année seulement pour maintenir le niveau de l’effectif syndical. Les universités offrent donc un bon potentiel de syndicalisation.

Il faut poursuivre les recherches sur le sujet. Les étudiants diplômés occupent une place importante dans la société. Non seulement fournissent-ils le leadership dans le monde universitaire et celui des affaires une fois leurs études complétées, mais encore ils fournissent également un leadership dans des milieux syndiqués longtemps après leur diplômation. Ils peuvent être lourdement endettés lorsqu’ils quittent l’université, et cela peut continuer même par la suite pour de longues périodes. Sans l’aide de la syndicalisation pour leur procurer une rémunération acceptable, cet endettement serait sans aucun doute accru. Par conséquent, la syndicalisation de ces groupes demeure importante pour s’assurer de la qualité de vie des étudiants diplômés, qui dépendent de ce type de travail pour maintenir une aide financière pendant leurs études.

Resumen

Los sindicatos de estudiantes graduados han comenzado a llamar la atención en Canadá y en Estados Unidos. En Canadá, la sindicalización en las universidades es particularmente importante para el movimiento laboral, puesto que la densidad ha descendido por debajo del 30 por ciento por la primera vez en cinco décadas. Sindicalizar los estudiantes graduados es también importante en el amplio contexto del empleo precario en America del Norte. A pesar del deterioro de la densidad sindical global, los sindicatos de estudiantes graduados han seguido creciendo durante la ultima década. Existe sin embargo una restricción respecto a la investigación académica. En este documento, nosotros examinamos los orígenes históricos de los sindicatos de estudiantes graduados en Canada, discutimos las cuestiones legales mas importantes, analizamos las cuestiones pertinentes a la negociación colectiva y la huelga, y sugerimos pistas por futuras investigaciones.

Corps de l’article

Graduate student unions are beginning to attract considerable academic and practitioner attention in North America (Duane, 2003; Lafer, 2003; Hayden, 2001; Saltzman, 2000). In Canada, unionization on campuses is potentially important for organized labour, as union density has dipped below 30 percent for the first time in five decades (Rose and Chaison, 2001; Galt, 2003). Between 1992 and 1997, membership declined by 255,000, representing a seven percent loss of total membership (Macredie and Pilon, 2001; Yates, 2002). Despite the decline in overall union density, graduate student unions have continued to grow in the past decade. This propensity to unionize may be associated with the tough financial situation facing Canadian universities, which has affected wages, workload, tuition, and eventual student indebtedness. In terms of organizing young workers, universities offer unprecedented opportunities for union recruitment, as they are undoubtedly the largest gathering place of student workers. As Tannock and Flocks (2002) note, student workers have the freedom to discuss their jobs without direct supervision; therefore, universities become potential powerful sites to launch mass campaigns for student workers to learn about workplace rights, discuss the value of unions, and make contacts for becoming organized. In 1997, there were 1,875,400 young employees in Canadian workplaces, representing 17 percent of the workforce and 5.7 percent of all union members (Grayson, 2001; Lipsig-Mumme, 1999).

Graduate students’ primary concerns are their studies and the acquisition of their respective degrees; however, many are employed to assist faculty members and administration with research, teaching, and other duties. The employment of graduate students is essential in financially supporting their ongoing studies. While universities struggle to keep labour costs as low as possible and simultaneously increase tuition in order to balance their budgets, graduate students in Canada are becoming more vulnerable to the demands placed on them by faculty, university and government. One tool employed by students to address these pressures is union representation.

The scholarly literature on graduate student unions in Canada is limited. Despite the transitory nature of student membership in these unions, restricted to their years of study, these unions attract attention from the university’s administrative system due to their potential for strikes and slowdowns. In this article, after reviewing the context, we will explore the origins of graduate student unions in Canada, discuss collective bargaining and strike issues, suggest potential areas of future research, and develop a theoretical framework and model that may be tested through quantitative studies.

Methodology

Approach

The lack of previous research on graduate student unions in Canada necessitated an exploratory research design. We use an historical-comparative approach in tracing the origins of the unions and the related collective bargaining and strike issues. This approach, combined with in-depth analyses of specific cases, allows for the use of quantitative data to support the largely qualitative analysis. Based on our findings, we will propose a theoretical model that may be tested in future research. The importance of the time dimension made an historical approach with its narrative qualities essential. Limited residual records plague scholars doing research on transitory groups such as graduate students, whose stay at universities lacks the permanence of staff or faculty, and is marked by regularly jettisoned records.

Operationalization and Definition of Key Terms

For the purposes of this research, graduate students are defined as all students engaged in post-graduate study in Canadian universities. The discussion of graduate student unions focuses primarily on teaching assistants but it also includes graduate and research assistants when they are included in the bargaining unit. All bargaining units that solely encompass tutors, sessional or part-time instructors or other academic employees were considered as being outside the parameters of this research.

Graduate student unions were defined as those possessing a collective agreement, whether or not the bargaining unit was affiliated with a larger national union. Additionally, students who joined larger bargaining units, such as those of the support staff, were deemed unionized for the purposes of this study, even though they were not part of a distinct unit.

Data Collection and Analyses

While the origins of the earliest of these unions are documented in archives and more recent locals appear sporadically online, comprehensive knowledge of the trajectory of the unionization of this group is lacking. The gaps in this knowledge base were filled through the use of a multi-tiered survey. The initial contact with graduate student unions was made by e-mail survey from directories listed online. These queries sought to verify if the students were indeed unionized, when the unit was formed, if there was strike activity, and any other information available or that would be willingly supplied.

A follow-up telephone survey was conducted to reach union locals that did not reply to the e-mail survey across Canada to ascertain whether or not a graduate student union existed at the universities in question. Universities without graduate programs were readily able to verify no graduate students existed to unionize. In the first round of the telephone survey, student union locals were contacted. When information deficiencies persisted, this round of inquiry was followed by a survey of student governments, then offices of the deans of graduate studies and finally concluded with the last round of telephone calls to Human Resources Departments at the remaining universities. In addition to the surveys, archival data were examined, primarily through union documents and press reports. The relevant statutory and various case laws were examined to help understand the criteria necessary to trigger student unionization and the associated constraints. The context for the unionization of graduate teaching assistants follows in the next section.

Context of Graduate Student Unions

Legal Overview

In Canada, as with other groups of employees, provincial and territorial legislation allows graduate students to organize and bargain collectively once they meet the defined thresholds of support and community of interest within the bargaining units. The first wave of union organization in the 1970s was initiated through a crucial 1975 Ontario Labour Relations Board (OLRB) decision in the case of the Graduate Assistants Association at York University (Graduate Assistant’s Association v. York University, OLRB Decisions, September 1975, 683). This case, which established that teaching assistants employed by universities are employees and have the right to organize and bargain collectively, paved the way for the unionization of teaching assistants in Ontario and the rest of Canada (Graduate Assistants Association v. McMaster University, OLRB Decisions, July 1979, 685; Graduate Assistant’s Association v. Carleton University, OLRB Decisions, February 1978, 179).

Prior to this decision, it was the position of the Board of Governors at York University that graduate and teaching assistants did not qualify as employees within the meaning of the Ontario Labour Relations Act. The university maintained that those graduate students assisting in research and teaching fell into the same category as students receiving scholarships, bursaries, or loans from the university. The Graduate Assistants Association maintained that graduate and teaching assistants were distinct because the work they performed was unrelated to the graduate student’s academic studies, and thus the funds received constituted wages. The OLRB ruled that graduate students of York University employed as teaching assistants and those employed as tutors and course directors at Atkinson College (the university’s evening program at that time) qualified as employees within the framework of the Act, while graduate assistants were excluded. Essentially, the OLRB ruled that teaching assistants were employees because the work was of direct and immediate benefit to the employer (Graduate Assistant’s Association v. York University, 1975). Further, the research and teaching work performed by the graduate students was not an integral aspect of their academic programs. However, the Board held that “Student Graduate Assistants” at York were not employees because the work was of a somewhat spurious or trivial character, and was done for financial purposes. Only one board member dissented. He concurred with the majority decision but argued that graduate assistants should also qualify. A year later, the British Columbia Labour Relations Board rejected the OLRB position on the employment status of graduate assistants, and ruled that interns and residents were also employees (Rogrow and Birch, 1984). These two decisions represented the first of their kind in Canada, thus opening up the possibility of unionization for all graduate students as employees as defined by the Labour Relations Act.

The legal situation in the United States is somewhat different from Canada, but it is relevant because U.S.-based cases are cited in cases pertaining to graduate student unions in Canada. In the United States, state laws govern unionization in public universities, and federal law applies to private universities. Graduate unions have enjoyed much more success in public universities. The Teaching Assistants’ Association at the University of Wisconsin was the first student union to gain recognition in 1969 (Cavell, 2000; Saltzman, 2000). By the end of the century, a majority (about 32) of the major public research and doctoral universities had recognized graduate student unions (Ehrenberg et al., 2002). However, not all states have relevant laws protecting the rights of graduate students to organize and bargain collectively. Further, in some states that guarantee this right, student unions, as is the case with other state employees, are not permitted to strike (Hayden, 2001; Leatherman, 2000).

Private universities in the United States have had a different history. Essentially, collective bargaining in the private sector is governed by the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA), and the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB). Prior to 2000 the NLRB consistently ruled that graduate teaching and research assistants were not employees under the law, and as such, were not covered by the NLRA (Rohrbacher, 2000; Rowland, 2001). In 2000, the NLRB reversed course in affirming an NLRB Director’s decision to hold an election for a unit of research assistants at New York University (Hayden, 2001; Gartland, 2002). The teaching assistants’ union was successful and bargained the first collective agreement for graduate students the following year (Ehrenberg et al., 2002). However, a more recent decision (Brown University v. NLRB, 342 NLRB 2004) has reversed NYU. That is, graduate universities at private universities, as was the situation in pre-2000, do not have the right to organize and bargain collectively because the NLRB held that they are primarily students and not employees under the law. This decision does not affect public universities. Overall, in both the public and private higher educational sectors, approximately 20 percent of all graduate employees in the United States are covered by union contracts (Lafer, 2003).

Other Contextual Issues: Precarious Work Arrangements and Youth Organizing

The employment of graduate students can best be described as temporary, since they work limited hours and only while enrolled. Even though graduate students may be very dependent upon this type of temporary work to support their studies, they do not occupy a core position in the academic framework, making their positions transitory and precarious. Cranford, Vosko and Zukewich define precarious employment as “forms of employment involving atypical employment contracts, limited social benefits and statutory entitlements, job insecurity, low job tenure, low earnings, poor working conditions and high risks of ill health [placing] emphasis on the quality of employment” (2003: 455).

The conditions of employment for teaching assistants share many of the dimensions of precarious employment delineated above. Outside of the union environment, graduate teaching assistants are challenged by limited access to job security, higher wages, extended benefits and increased risks of ill health due to stress. Despite its transient nature, this sector remains important to the future of the Canadian labour movement.

The scattered nature of teaching assistants’ work did not make them good candidates for certification except from within the university campus and consequently, not the target of frequent unionization drives until the last decade. In 1996, the Canadian Labour Congress (CLC) adopted a resolution that called for youth to become a central outreach and organizing priority for all union affiliates. Declining union density in Canada has stimulated this interest in rejuvenating the labour movement by organizing youth, particularly in low-wage jobs in the retail, food and hospitality industries (MacDonald, 1999). The nature of graduate student teaching assistantship distinguishes the group from the typical low-wage earner in retail, food or hospitality; consequently, these broad-based appeals generate little more than awareness for graduate students. Pre-existing awareness of unionization underlies recent certification of new locals (Duane, 2003; Lazarovici, 2002). Universities are highly organized communities that include student unions, ethnic and linguistic student organizations, faculty and support-staff unions (Tannock and Flocks, 2002). To respond to this opportunity, working student centres on university campuses have been created at three universities in Toronto (York, Ryerson and the University of Toronto), and have attracted interest elsewhere. Although the foci of these centres are not primarily the university as employer, there is an opportunity generated for awareness.

The Origins, Prevalence, and Functions of Graduate Student Unions in Canada

Origins and Evolution

The unionization of Canadian graduate students occurred in two waves. The earliest universities to establish their own union locals did so in the mid-to-late 1970s, largely in Ontario and British Columbia (Rogrow and Birch, 1984). The second wave has been in the last decade, with few additions in the intervening period. Shared motivation for both waves appears to be the rate of pay and the workload. More recent efforts seem to be further stimulated and reinforced by reduced opportunities for future employment and increased tuition costs.

The first successful organization of a bargaining unit for graduate students was established at Victoria College of the University of Toronto in 1973, and certified in August 1974 as Local 1 of the Graduate Assistants Association (GAA); however, it never signed its first contract (Graduate Assistants Association, 1980). The University of Windsor graduate students were organized as a de facto teaching assistants union in that summer as well. The union was not a legal bargaining unit but its recognition by the senate and board of governors gave it legitimacy. The president of Windsor’s Graduate Student Society, Frank Miller, cited “a growing sense of dissatisfaction due to the insensitivity of the administration” and a university-wide strike as being pivotal in the organization of graduate assistants (McCracken, 1973). McGill University teaching assistants formed the McGill Teaching Assistant Association in 1974 and staged an unofficial strike in 1976, long before certification.

During the 1972 to 1973 academic year, the University of Toronto graduate students at the main campus revived their failed attempt of the previous year to organize. The extended efforts of the teaching assistants continued to March 5, 1974, when the GAA made its application for certification. As proved to be the case in many certification drives to follow, timing remained a difficulty for the organization of graduate students. The date for the vote on the certification of the GAA was set for late May 1974, well after the end of the semester. Appeals in the university newspaper, The Bulletin, indicated that both the administration and union organizers felt that the date could have skewed the results in favour of the other side (University of Toronto Bulletin, 1974).

The frequent turnover of staff in the case of teaching assistants, who may be hired for only a year or two, makes it incumbent on organizers of any graduate student union to start with education and information for new employees every autumn. Whatever momentum is gathered in any given academic year could be lost by May. This was the case for the efforts of graduate students at many universities. As a result, the initial certification process often spans many years, as in the case of the University of Toronto students, who were forced to abandon their efforts in 1973, but finally became Local 2 of the GAA in 1975 (CUEW, 1985).

Local 1 of the GAA was quickly absorbed into Local 2. Local 3 at York University, which represented teaching assistants and sessional instructors, followed these locals. Local 4 was formed at Ryerson Polytechnic Institute in 1978 for sessional and part-time faculty. In 1979, the teaching assistants formed Local 5 at Lakehead University. In 1980, McMaster University teaching assistants and contract faculty, and the graduate assistants in the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education (OISE) formed Locals 6 and 7, respectively. In 1980, the Graduate Assistants Association was renamed the Canadian Union of Educational Workers (CUEW). Local 9 was formed in 1985 at the University of Manitoba for student instructors (CUPE, Local 3902, 2003). Very few of these early CUEW locals were devoted exclusively to teaching assistants or graduate students; they were largely concerned with sessional or contract faculty.

In some cases, union membership came early to graduate students by virtue of being lumped together with support staff or, more frequently, with sessional or part-time faculty. In the case of the University of Windsor, the bargaining unit was university-wide. At Simon Fraser University, the graduate students joined the Teaching and Support Staff Union in 1978. At some universities, the impetus for the organization of graduate students was part and parcel of the efforts of sessional teachers, who often form a second unit of the local.

The first flurry of union locals for teaching assistants, with operations largely in Ontario and British Columbia, did not stimulate a national trend in the 1980s. The second wave of union certification came primarily in the 1990s. McGill University teaching assistants, through the FNEEQ (Fédération nationale des enseignantes et enseignants du Québec), established their union in 1992, but did not sign a contract until 1998. Dalhousie University teaching assistants and part-time teachers initially formed an informal committee to unionize, and on August 31, 1994, CUEW Local 12 was certified (CUPE, Local 3912, 2003). The local officially became CUPE Local 3912 on January 1, 1995. Ongoing negotiations between all the CUEW locals and CUPE culminated in an official merger on January 1, 1995. CUPE became the official union for the graduate students formerly represented by CUEW. Financial concerns prompted the merger, but the resulting amalgamation increased political clout and the strike fund (Murdock, 1995). Organizing drives at Saint Mary’s and Mount Saint Vincent Universities resulted in part-timers or sessionals being represented by CUPE Local 3912 by September 1995. In 1995, the local sought acceptable grievance and arbitration procedures, job security, standardized workload, and a sizeable increase in pay which was low for part-timers in Canada and the Atlantic provinces. The University of Windsor formed a union affiliated with Public Service Association Committee (PSAC) in 1996, as did the University of Western Ontario. These successful union drives set the stage for more recent and ongoing efforts.

Attempts to certify new union locals across the country continue despite resistance from universities and some graduate students alike. As recently as February 12, 2003, the Graduate Student Association Council of the University of New Brunswick discussed the prospect of teaching assistant (TA) unionization (Graduate Student Association Council, 2003). The discussion opened up the possibility of collective bargaining, while others expressed reservations about the process. The organization of TAs has often been limited by the mentality that they were only of a temporary nature. As Sarah Reigel, a TA at Queen’s University, explained: “some people even used the short term nature of their employment as a reason for voting against unionization, because they didn’t feel it was “fair” to make a decision that would affect students not yet at Queen’s” (Reigel, n.d.). After two unsuccessful certification bids in the 1980s, in the 1997 to 1998 academic year, the Teaching and Research Assistant Certification Campaign (TRACC) at Queen’s University failed to join CUPE. The teaching assistants reorganized as Queen’s University TAs for Unionization (QUTU) to stage another certification drive in 2003. A vote took place February 5, 2004; however, the university challenged the voters’ list and the OLRB subsequently ordered the ballots sealed. That challenge has been resolved and the students were once again unsuccessful in their bid to unionize graduate students (Queens News Centre, 2004).

The ongoing certification drive at Université de Montréal and preliminary discussions at Université Laval parallel recent efforts in Ontario. Alliance de la Fonction publique du Canada (AFPC/PSAC) has attempted to step in to fill the virtual void in Québec, where FNEEQ is the sole representative of teaching assistants. Compared to Ontario, Quebec offers several opportunities for unions to increase their density rates. This marks a step toward broadening the base of unionized teaching assistants across the country.

Coverage

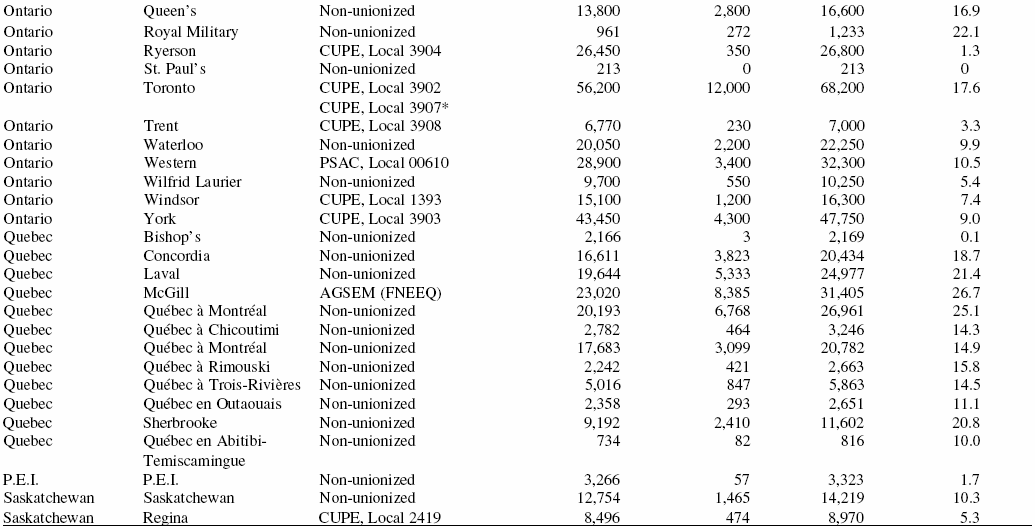

Rates of graduate student unionization vary across the country, ranging from no union locals to full unionization, with a national rate of 41 percent (see Tables 1 and 2). The highest rates of unionization are in Saskatchewan, British Columbia, Nova Scotia and Ontario. In many cases, the absence of a bargaining unit for graduate students is due to the fact that the university is entirely or primarily an undergraduate teaching institution. In the case of the ten-year old University of Northern British Columbia, the graduate student population totals less than 10 percent and the newness of the university may account for the fact that it is the only non-unionized university in the province. Table 1 highlights the number of graduate student unions and union coverage in each province as of March 2004. Table 2 provides a breakdown by university of the proportion of graduate students and unionization where applicable.

As can be seen, a very low population of graduate students seems to be indicative that there will be no union local on campus for teaching assistants. Certain pockets of the country, such as the Atlantic provinces, have a lower rate of union coverage because they have limited or no graduate student populations. Memorial University in Newfoundland remains the only major exception. Queen’s University in Ontario does not have a union despite its relatively high proportion of graduate students. Alberta stands out in the west where only the University of Alberta’s Graduate Student Union has signed a collective agreement with the university.

Table 1

Graduate Student Union Locals in Canadian Universities, 2003

Additional information was drawn from the union local websites.

Quebec, with its low rate of student unionization, stands out because most of the universities in Quebec have substantial graduate student populations. A comparison of the average rate of unionization as a percent of total employment from 1999 to 2003 indicates that Quebec had the highest rate of unionization (40.3 percent) in all of North America, yet, it has one of the lowest rates of graduate student unionization (Fraser Forum, 2004). Only the graduate students at McGill are unionized through the AGSEM (Association of Graduate Students Employed at McGill), part of FNEEQ, and signed their first collective agreement in 1998. Jordan Geller, the president of the AGSEM, argues that the meagre unionization of graduate students in Quebec can be attributed to “student apathy, an unwillingness to ‘rock the boat’ and the social order in Quebec, where students and young workers are paid poorly and it is considered the norm.”[1] Geller reports that the case of the McGill students is “unusual because the Post Graduate Student Society, unlike other graduate student associations took a passive role in the drive for unionization. The push toward unionization at McGill was a grassroots movement that should be credited to the determination and hard work of specific individuals.” In general, Geller felt that the province’s major union (to which FNEEQ belongs), the Confédération des syndicats nationaux (CSN), was not ‘in touch’ with the graduate students and its presentations lacked appeal for students, having more to offer to sessionals. As a latecomer to unionization, the ASGEM’s work is stimulated by members that have had previous experience with teaching assistant unions in universities such as York and McMaster. CUPE, Local 3902 at the University of Toronto was helpful during ASGEM’s last strike.

In the case of McGill University, the university offered its teaching assistants wages and teaching conditions that were competitive among Canadian universities, which effectively stalled the movement toward certification. However, the university administration at McGill forestalled these efforts with the Senate “Ad Hoc Committee to Investigate the Employment of Graduate Students in a Teaching Capacity” in December 1975, which followed on the heels of the establishment of the McGill Teaching Assistants Association (MTAA) in 1974. The document acknowledged that teaching assistantships provided income for graduate students, enriched departments, maintained the educational program of the university and improved the teaching profession (Senate, 1975). In order to address the concerns of the teaching assistants, workloads were set at twelve hours a week, no fifth year appointments would be made without approval of the Dean, and stipends, indexed for cost-of-living increases, would be competitive with those at other Canadian universities. An eight-day unofficial strike in 1976 resulted in an agreement on a base salary of $3,750 per year with cost-of-living indexation (AGSEM, 2004). This generous settlement effectively awarded McGill teaching assistants better pay and working conditions than those in other universities establishing the early union locals. Rates of pay and working conditions were similar during the 1980s at the city’s other English-language university, Concordia. These proactive actions on the part of university administration delayed the certification of unions in Quebec and are still a major factor in the limitation of the unionization on Quebec campuses.

Table 2

Proportion of Unionized Students by School

* University of Toronto became successor employer to this bargaining unit on July 1, 1996 when Ontario Institute for Studies in Education (OISE) merged with the university’s Faculty of Education (University of Toronto Human Resources Department, Labour Relations, University of Toronto Certified Bargaining Agents: General Info, www.utoronto.ca/hrhome/bargain.htm, accessed July 30, 2004).

** In Canada, given exclusive representation for a union of all employees in a bargaining unit, it can be assumed that all graduate students are covered by unions where collective agreements are in force.

At Université Laval, administrative challenges and resistance to the formation of a union of research assistants have endured for more than a decade. On July 3, 1990 the APARSQ (l’Association des professionnels et des assistants de recherche en sciences du Québec), supported by the Centrale de l’enseignement du Québec, now the Centrale des syndicates du Québec, applied for the accreditation of their union for research assistants in the university and its research hospitals. The university was resolute in its insistence that it merely held grant funds in trust for professors conducting research. It did not control the hiring of research assistants, nor did it determine their work and therefore could not be defined as an employer. The faculty union SPPRUL (Syndicat des professionnelles et professionnels de recherche de l’Université Laval) joined the research assistants in their assertion that research was part of the university’s mission (SPPRUL, 2001). In 1996, the Tribunal du travail deemed that the university was indeed the employer and allowed the union to go forward for certification (SPPRUL, 2001). The university then launched an appeal of this decision that put the entire matter in abeyance until 2001. Thus the process was delayed for over a decade, forcing the research assistant unionization drive to a temporary halt. The painstaking definition of research assistants within Université Laval managed to separate students from the group, thus preventing student research assistants from participating in the future union.

Mathieu Dumont, union organizer for AFPC, argues that the long delay in organizing Quebec’s teaching assistants is the product of several factors. First and foremost, university administrations have presented barriers. Secondly, the unions have been slow to approach the graduate student education sector because of the difficulty in organizing such a scattered workforce and it has taken time to develop an infrastructure to handle the group. Dumont also indicated that the internet, and its inherent capacity to communicate with the dispersed workforce, has assisted in the process. The ongoing drive at UQAM has faced pockets of “resistance from cultural communities. In particular, students from France have a different conception of the unionization process and do not realize that by not signing their cards they prevent the formation of the union local.”[2]

While PSAC attempted to make inroads recently in Quebec, CUPE continues to dominate the rest of Canada, covering over 75 percent of graduate student unions. Derek Blackadder, the CUPE organizing representative for Ontario, indicates that “CUPE has been able to capture this sector due to the amalgamation of CUEW with CUPE. This merger has contributed to the consolidation and success of graduate student unionization in the country.”[3] What remains to be seen is how successful PSAC will be in Quebec. Should it dominate in the province, a potential conflict could arise between the two unions as PSAC’s share of the coverage increases.

Collective Bargaining and Strike Issues

Not unlike other unions, graduate student organizations have been primarily engaged in bargaining and striking for better wages, job security, and improved working conditions. In 1980, Ryerson’s contract faculty waged CUEW’s first strike for job security, fair hiring practices, and equal pay for equal work. Despite the early organization of contract faculty, the university’s teaching assistants were only certified in 2003. Canada’s first teaching assistants’ strike occurred in 1981 at York University. This strike focused on class sizes, job security, and wages. In 1984, after the provincial government lifted the Inflation Restraint Act, York students staged their next strike over wages, job security and participation in academic bodies of the university.[4] On February 23, 1989, over 2600 teaching assistants and lecturers at University of Toronto walked out over unfair hiring practices, job security, class size, wages, and workload (CUEW/SCTTE Connexions, 1989). In 1991, the University of Toronto teaching assistants accepted the university’s proposal of a lower wage offer, but with the promise of a workload study (Thompson, 1991). This represented a significant agreement because workload issues had always been a part of negotiations; however, this was the first time that workload had taken precedence over wages. The proposed investigation concerning class size and job descriptions addressed a long-standing issue for teaching assistants. The committee, composed of two teaching assistants and two administrators, was to review two divisions monthly, as designated by the union. The University of Toronto graduate students hoped for a university-wide standardization of workloads. CUPE Local 3902 was one of three unions simultaneously on strike at the University of Toronto, which added to the strike’s impact.

Three decades later, the issues that drove the campaign for certification of this first union are perennial in the ongoing negotiations between graduate students and university administrators. The rate of pay and setting a fair number of hours of work were an essential part of this early drive just as they are today. In 1973, some teaching assistants at the University of Toronto were paid an annual minimum of $400 yearly for four hours a week, while the maximum was $2,400 in the department of political economy. There were 444 pay categories for graduate students (McCracken, 1973). Rates of pay varied from department to department. Some students were paid by the hour or by the marked paper. Students could be fired without cause and had no avenue for appeal. The first collective agreement at University of Toronto reduced 444 pay categories to 3. At the same time, hiring and grievance procedures were introduced (CUPE, Local 3902, 2003).

Not surprisingly, the wage issue has consistently mobilized students into action. An 18 percent wage cut in 1997 at the University of Victoria rapidly mobilized graduate students to organize as Local 89 of the Canadian Federation of Students, despite a failed attempt to organize in 1992 to 1993. Then on March 31, 1998, teaching assistants joined lab assistants and language instructors to form CUPE, Local 4163.

Similarly, the 2003 negotiations at the University of British Columbia focused on wages, health coverage and tuition assistance. CUPE, Local 2278, represents the University of British Columbia teaching assistants and ranks its members as one of the lowest-paid unionized groups in Canada. Negotiations in 2003 at Carleton University have teaching assistants seeking a cap to class size in the wake of the double cohort (CBC, 2003). On April 24, 2003, 900 teaching assistants went on strike at McGill University in Montreal. Their concerns included competitive wages across campus, maternity leaves, bereavement, and vacation pay. Wages for McGill University teaching assistants were among the lowest in the country at $14.50 to $18.49 per hour at that time. The initial and early commitment in 1975 to cost-of-living indexation had fallen by the wayside and produced a catalyst for the certification of AGSEM. The strike resulted in an increased rate of pay that ranges from $16.24 to $19.76. However by 2007, wages will be equalized across the departments with all students earning $22.24 per hour. Compared to the rest of Canada, the current wage rates are still quite low in comparison to other unionized teaching assistants (see Table 3).

In the last decade, tuition rebates have figured more prominently in the demands of graduate student unions. Where tuition rebates have not been offered, wage increases have been sought. The York University strike held in 1997 provides a contemporary example of the importance of new issues such as tuition rebates, health and dental plans, parental leave and same-sex benefits. These newer issues are exacerbated by reduced funding to universities, which provokes increased tuition and student debt loads (OCUFA, 2002; Starnes, 2002; CURC, 1999). Reduced funding also potentially increases faculty teaching workloads and in turn that of graduate teaching assistants (Healy, 2000; Schofield, 2000).

Table 3

Teaching Assistants Top Rates of Hourly Pay, 2003

*not unionized

After three decades of union growth in this sector, perhaps there is no better example of the strength of these unions than the 2000 York University strike. It demonstrated the power of a graduate student union when strategies and activities are effectively planned and executed, with high involvement from its membership. On October 26, 2000, CUPE Local 3903, representing approximately 2100 teaching assistants, contract faculty, and the newly certified union of graduate assistants (GAs) at York University went on strike. The strike lasted 78 days and is recorded as one of the longest strikes in Canadian university history.

The main objective for the university was to limit cost increases and to remove any direct connection between tuition fees and wages or other benefits. The union demanded tuition-indexing, uniform wages across departments, a small amount of summer funding, and some minimal health benefits (Kuhling, 2002). Although the strike represented three separate groups with their own agendas, they also shared common concerns, thus adding strength and leverage to the overall effort (Lipsig-Mumme, 2001).

The strike also demonstrated an unprecedented amount of support from the York University Faculty Association (YUFA), Canadian Auto Workers (CAW) locals, and the students (Kuhling, 2002). The university ultimately brought the deadlock to the forefront when they made a request to the Ministry of Labour to order a ratification vote on its final offer. This was the second time since 1997 that a strike at the university threatened the graduation of students, thus impinging on the reputation of the university. A large majority of faculty members refused to cross the picket lines, leaving students without classes to attend, regardless of their intention.

The ratification vote was not entirely a success for the university as the teaching and graduate assistants rejected York’s final offer by a vote of 69 percent and 78 percent respectively. However, contract faculty accepted the offer by 53 percent. The success of this acceptance was short-lived for the university since contract faculty refused to cross the picket lines. With both sides at an impasse, negotiations resumed and an agreement was reached four days later. For 400 graduate assistants, this was their first contract.

In addition to increased wages, a health benefits package (80 percent paid by the employer first year and 100 percent in the second year), discrimination and harassment language, and a grievance procedure were made part of the settlement. They also negotiated groundbreaking language to include transsexual transition status and gender expression and gender identity as a basis for discrimination (Kuhling, 2002).

Analysis, Discussion and Research Questions

An analysis of the historical information, legal cases, and the research reveals several interesting issues. A number of interconnected variables pertaining to environmental, organizational, union, and personal factors emerge that may influence graduate students to form organizations to represent their collective interests.

Environmental Factors

Unionization may be affected by factors in the larger, macro system, such as the state of the economy and the political and legal environments (Fiorito, Gallagher and Greer, 1982; Murray and Reshef, 1988; Ofori-Dankwa, 1993). Even though these variables have been used to partly explain the formation of traditional labour unions, they are relevant to the student union movement as well. The actors in this system, namely the government, the universities with their corporate alliances, and the students and their unions, all play an integral role within these arenas, and lead to a better understanding of graduate student unionization.

Economic Issues

There have been dramatic changes in the funding of Canadian universities over the past two decades, reflecting, in part, the state of the economy. In 1978, government funding accounted for 84 percent of Canadian universities’ operating budgets, but by 2002, that funding had declined to about 60 percent (Starnes, 2002). Universities can no longer rely on public funding only and must secure means to generate income to help finance their institutions. Income has been sourced from corporate partnerships, increased tuitions, and an increased talk of privatization of universities.

Revenues generated from corporate sponsorship and increased tuition fees are proving to be viable sources of income for universities. For example, from 2001 to 2002, 55.8 percent of university revenue in Ontario came from non-government grants, of which 27.5 percent were from student fees, and government transfers represented 44.2 percent (Shaker, 2002). In 1992 to 1993, Ontario universities were granted $10,204 per student funding, but in 2001 to 2003 only $6,831 was allocated per student. Corporate influence is sufficiently evident on most campuses in Canada and can take many forms. Corporate advertisements in washroom stalls, exclusive soft-drink suppliers which can generate as much as $10 million over 11-year periods (Schofield, 2000), buildings in endowed names (Tudiver, 1999), and the selling of research contracts with science, engineering and business schools, at the expense of humanities and social science programs (C.D. Howe Institute, 2002; Laidler, 2002) are just a few examples of corporate influence at Canadian universities. Is the increasing amount of corporatization in Canadian universities leading to increased graduate student unionization? This is an issue that needs to be researched.

Furthermore, it may be argued that the decision to unionize results from a rational assessment of the costs and benefits of joining a union, and the costs and benefits of not doing so (Farber and Saks, 1980; Kochan, 1980). The cost of education has been increasing across Canada. For example, in the past decade, Alberta has reported the highest increases at 167.5 percent, followed by Ontario with an increase of 130.5 percent. The lowest increases are found in British Columbia with only a 56.9 percent increase in tuition in the last decade (Statistics Canada, 1991–2003 in CURC, 2003). Furthermore, a comparison of summer earnings to actual tuition fees paid shows that a student in Quebec earned, for instance, on average, $3,100 in summer employment income during 2001, and paid $2,815 in tuition in 2002–2003 (HRDC, 2000–2001 in CURC, 2003). The highest tuition fees are found in Nova Scotia, with $4,771 paid out per year, but summer employment income only amounting to $3,700. Therefore, are increasing tuition costs driving student unionization? Are the earnings that students make leading to increased unionization?

A related issue for graduate students concerns the time-to-completion. The average time-to-completion for Ph.Ds ranges from 14 terms in the physical and applied sciences to as many as 18 terms in the humanities (Berkowitz, 2003). In a cohort study of doctoral students from 1980 to 1984, the graduation rate was 57 percent (Yeates, 2003). Without a significant change in graduation rates, tuition, debt load and alternative sources for funding, graduate students will potentially continue to organize for collective bargaining rights. This leads us to several questions: Is research funding related to graduate student unionization? Is time-to-completion increasing the rate of graduate student unionization?

Political and Legal Factors

In Canada, the political and legal frameworks are intertwined in the industrial relations system. With the exception of inter-provincial entities, such as firms in transportation and banking, labour law is developed and administered through the political, legal and administrative systems of the ten provinces. At the provincial level, it is not unusual for labour laws to be changed once a new political party accedes to government. For instance, the NDP government in Ontario in the early 1990s banned the use of permanent strike replacement workers, but this prohibition was lifted once the Conservatives came to power (Singh and Jain, 2001). Bill 132, enacted while the Conservative government was in power, allowed for private for-profit universities and the Liberals have recently announced a plan to allow the RCC College of Technology, a private university, to grant bachelor degrees following through on a Conservative policy.[5] It is very likely that the political and legal environment in Canada will have an effect on graduate student unionization, but there is no research on this issue. Are graduate students’ intentions to form a union higher in provinces with a pro-union political party in government? What is the relationship between pro-union labour laws and graduate student unionization? Is the rhetoric surrounding privatization influencing graduate students to organize?

Organizational and Work Related Factors

As one of the earliest explanations for workers joining unions suggested, workers do so to obtain job security and to improve employment conditions (Perlman, 1928). With the increased threat of privatization, comes the threat of job security. As well, the precarious nature of graduate student work also leads to the threat of job security. As work becomes available from faculty, there is no guarantee as to whom will be given the work, and therefore, there is no guarantee of employment for workers. Is the precarious nature of graduate student work leading to increased organizing activity? Is the threat of privatization impacting on graduate students’ decision to organize?

In several provinces, job conditions for graduate students can be aggravated by increased enrollment and reduced funding which results in increased student indebtedness (Shaker, 2002). With increased enrollment comes the pressure of additional workload for faculty. The implications for graduate students are disconcerting. A number of graduate students act as research and teaching assistants or markers within their faculties. Unfortunately, with an increased student-faculty ratio, the amount of workload will increase, not only for faculty, but in all probability for the graduate assistants who help to fill the gap. There will be more students to meet with, more assignments to be graded, and more tutorials to facilitate. Are higher workloads for graduate students related to an increased propensity to unionize? Are issues of job security increasing the need to unionize? There is need for research on this issue. Increased workloads may ultimately lead to lower levels of job satisfaction. Job dissatisfaction and autocratic leadership catalyze the decision to unionize, as it provides workers with a collective voice and a way to eliminate sources of dissatisfaction (Brett, 1980; Freeman and Medoff, 1984; Heneman and Sandver, 1983; Premack and Hunter, 1988). Are lower levels of job satisfaction related to higher propensities to join a union in Canada?

Union Factors

With decreasing density, unions have had to seek alternative recruits in order to sustain union growth in an environment that continues to challenge union goals. Although only 40.7 percent of universities have unionized graduate students, there remain significant organizing opportunities, particularly in Quebec, where only one of the universities has representation. As discussed, Quebec has the highest levels of unionization in North America (40.3 percent), but one of the lowest levels of graduate student unionization, leaving a question as to why Quebec has not organized more graduate student unions. While the aggressive stance of university administrators may have forestalled effective unionization, is the situation in Quebec related to provincial union dynamics? Are there differences amongst the various national unions that contribute to the organizing success in any of the universities?

Personal Factors

The decision to unionize is ultimately an individual one. The ideological orientation and attitudes of workers to unions may also influence the decision, with those holding left-leaning positions more prone to unionization (Adams, 1974; Heneman and Sandver, 1983; Kochan, 1979). Workers and students may join unions because of their political and ideological beliefs and philosophies (Wheeler and McClendon, 1991; Hemmasi and Graf, 1993). Those who believe in group solidarity join unions because they perceive unions as a major vehicle for successful collective action (Haberfeld, 1995). Workers’ and students’ attitudes towards unions may also influence the value they place on collective action (Brett, 1980; Lowe and Rastin, 2000; Newton and Shore, 1992). As Brett (1980) found, the likelihood that dissatisfied employees will form a union depends on whether they accept the concept of collective action and believe that unionization will lead to positive outcomes for them. It is logical to expect that graduate students will be similarly influenced. Additional research has focused on the effects of early introduction to unions (i.e. family members favoured unions), and the effect that important others may have on a potential member’s propensity to become engaged in union activity (i.e. co-workers may sell the concept of unionizing as a valuable tool to collective voice). There is some evidence, although limited, that early family experiences may be related to one’s belief in unionism (Barling, Fullagar and Kelloway, 1992; Gordon et al., 1980). In union organizing campaigns, socialization tactics could be expected to influence an individual’s belief in unions (Tetrick, 1995). This is an area in need of research. Furthermore, the attitudes of administrators may also influence union formation. Some administrators, as discussed in the York case in the 1980s, and at Yale (Hayden, 2001; Rowland, 2001) have resisted unionization; however, the pro-collective bargaining perspective of the Chancellor of the University of Wisconsin resulted in the first graduate student union in the United States (Saltzman, 2000). Thus, it may be prudent to conduct research on the relationship between the attitudes of administrators and unionization. Are beliefs and attitudes important variables in explaining graduate student organizing?

Towards a Theoretical Framework and a Testable Model

A number of theories may be used in future research to test many of the research questions posed in this article. Organizational and work-related factors are generally related with dissonance theories of unionism. That is, workers join unions because there is a dissonance between expectations of work and the experience of work. Dissonance may manifest itself as job and pay dissatisfaction and the experience of unfair treatment (Charlwood, 2002; Kochan, 1980).

Amongst the personal factors discussed in this article, beliefs and attitudes emerged as reasons why individuals may unionize. A second theory that has been used extensively to explain an employee’s behaviour is the Theory of Reasoned Action (Fishbein and Ajzen, 1975). The theory posits that an individual’s behavioural intention is the single best predictor of whether or not they will engage in a behaviour. Behavioural intention is, in turn, determined by a person’s attitudes toward the behaviour, specifically his or her positive or negative evaluation of the consequences of performing the behaviour. An individual’s attitude toward a behaviour is composed of two components: behavioural beliefs about the outcomes a behaviour is believed to yield, and an evaluation of these outcomes (favourable or unfavourable). For example, a graduate student may believe that belonging to a union will ensure that they are treated fairly, and therefore their positive attitudes towards joining a union will increase their job security. Subjective norms are a function of normative beliefs about the social expectations of significant others such as spouse, parents, co-workers or close friends. Subjective norms are the perceived social pressures an individual faces when deciding whether to behave in one way or another. Therefore, a model that includes variables such as beliefs, attitudes, intentions to participate, and job dissatisfaction may lead to a better understanding of graduate student unionization. Figure 1 represents a possible theoretical framework to test our theory. In our analysis, we identified a number of key issues that may be affecting graduate student unionization. Some of these were the effects of increasing tuition, lower than expected earnings levels, time-to-completion, increased workloads, privatization of universities, precarious employment, level of national union involvement and public policy set by political parties who may or may not be pro-union. Each of these may lead to beliefs that unionization is indeed important, and will ensure such things as increased job security, increased wages, and reasonable tuition and benefits levels. Achieving those objectives may lead to more positive attitudes towards unionization that will increase the likelihood of a graduate student’s willingness to join a union and the eventual unionization of a local. For some students, job dissatisfaction may also lead to intentions to unionize because they are unhappy with their current state and feel the only way to deal with the issues are to unionize.

Conclusion

The intent of this article was to review the context in which graduate student unions have formed, to uncover potential research questions, and to develop a theoretical framework with variables that could be measured and relationships tested in future quantitative studies on graduate student unionization. It is evident that for trade unions, organizing the unorganized remains an important issue. For instance, organizing is considered to be the life-blood of the CUPE union where attrition rates are approximately five percent annually (CUPE, 2002). Therefore, 9,000 new members are required every year just to maintain CUPE’s membership levels. Universities offer an opportunity from which unions such as CUPE can increase their membership levels. In the past, the labour movement has focused on large traditional groups to organize, such as workers in the steel and automotive sectors, without much consideration to other groups. With the emergence and growth of the contingent workforce, locked into precarious work arrangements, including youth workers, unions may have to devote more time and resources to the non-traditional sectors. However, it seems as if the central labour bodies in Canada are allowing graduate students to develop grassroots movements, rather than intervening directly. Thus, while it appears as if organized labour is silent on the issue, they actually work in the background and lend support as needed.

Figure 1

Testing a Theory of Graduate Student Unionization in Canada

As discussed, there are numerous research opportunities from which to build on our understanding of this transitory group of activists. Until more empirical research is conducted, we will not fully understand this phenomenon. Graduate students potentially provide necessary leadership in either academia or in business upon completion of their degrees and may provide leadership in unionized environments long before graduation. As Gomez, Gunderson and Meltz note, “if youths are introduced to unionization early in their careers, they will more likely develop attitudes, networks and norms that foster continued unionization. In other words, unionism begets unionism” (2001: 4). The unionization of these groups continues to be important to ensure the quality of life for graduate students who depend on this type of work for financial support throughout the tenure of their studies.

Parties annexes

Notes

-

[1]

Interview with Jordan Geller of the AGSEM on March 10, 2004.

-

[2]

Interview with Mathieu Dumont, AFPC, on March 3, 2004 (translated).

-

[3]

Interview with Derek Blackadder, CUPE, on March 1, 2004.

-

[4]

The Inflation Restraint Act was enforced as law in Canada in 1974. The intent of this Act was to bring down inflation, and as such, wage increases were constrained.

-

[5]

On October 29, 2000, the Conservative government of Mike Harris introduced Bill 132 into the Ontario Legislature, introducing private for-profit universities in Ontario and clearing the way for fundamental restructuring of colleges and universities (CUPE Research Branch, October 26, 2000, p. 2). The Sea to Sky University Act is a private bill establishing a new university in British Columbia. SSU will be a private, non-secular, non-profit liberal arts institution with enrolment of initially 400 and ultimately 1,200 students. It will offer British Columbians expanded academic choice and a high-calibre internationally oriented curriculum subject to rigorous quality standards (Ralph Sultan, 2002 Legislative Session: 3rd Session, 37th Parliament, May 29).

References

- Adams, Roy. 1974. “Solidarity, Self-interest, and the Unionization Differential between Europe and North America.” Relations Industrielles/Industrial Relations, 29 (3), 497–512.

- AGSEM. 2004. “Archives: History of the First Contract Negotiation (1994–1997), http://www.web.net/~agsem/history_hist_negotiation.htm (accessed December 22, 2004).

- Barling, J., C. Fullagar, and E. K. Kelloway. 1992. The Union and Its Members: A Psychological Approach. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Berkowitz, Peggy. 2003. “The Long Haul.” University Affairs, February, 8–12.

- Brett, Jeanne. 1980. “Why Employees Want Unions.” Organizational Dynamics, Spring, 47–59.

- C. D. Howe Institute. 2002. “Funding Problems Undermining Universities’ Contributions to Knowledge Economy.” Communiqué, April 23.

- Cavell, Lori. 2000. “Graduate Student Unionization in Higher Education.” ERIC Digest 2000. [Online] http://www.eriche.org.

- CBC Ottawa. 2003. “Carleton TAs want Class Size Limits.” January 13, http://ottawa.cbc.ca/template/servlet.

- Charlwood, Andy. 2002. “Why do Non-Union Employees Want to Unionize? Evidence from Britain.” British Journal of Industrial Relations, 40 (3), 463–491.

- Cranford, Cynthia J., Leah F. Vosko and Nancy Zukewich. 2003. “The Gender of Precarious Employment in Canada.” Relations Industrielles/Industrial Relations, 58 (3), 455–482.

- CUEW (Canadian Union of Educational Workers). 1985. Members’ Manual 1985. Toronto.

- CUEW/SCTTE Connexions. 1989. “On Strike.” Vol. 6, April, 3.

- CUPE (Canadian Union of Public Employees), Local 2278. http://www.cupe2278.ca/why_strike.htm (accessed April 13, 2003).

- CUPE (Canadian Union of Public Employees), Local 3902. “History of the Union.” Members Manual. http://www.cupe3902.org/membinfo/membman/history.html (accessed April 4, 2003).

- CUPE (Canadian Union of Public Employees), Local 3912. 2002. “About 3912: Our History.” http://cupe3912.ca/temp/about/historyall.html (accessed March 29, 2003).

- CUPE (Canadian Union of Public Employees). 2002. “Ontario Universities and the Double Cohort: What will be the Impact on CUPE Members?” Education. November 6, 1–15. http://cupe.ca/issues/education/showitem.asp (accessed June 1, 2003).

- CURC (Canadian Undergraduate Research Consortium). 1999. Graduating Students Survey. as cited in CAUT. 2003. CAUT Almanac of Post-Secondary Education, 27 (5), 19.

- Duane, Daniel. 2003. “Eggheads Unite.” New York Times, May 6, 23.

- Ehrenberg, R., D. Klaff, A. Kesborn and M. Nagowski. 2002. “Collective Bargaining in American Higher Education.” Paper presented at the Cornell Higher Education Research Institute Conference, New York, June 4–5.

- Farber, H., and D. Saks. 1980. “Why Employees Want Unions: The Role of Relative Wages and Job Characteristics.” Journal of Political Economy, 88, 349–369.

- Fiorito, Jack, Daniel Gallagher and Charles Greer. 1982. “Determinants of U.S. Unionism: Past Research and Future Needs.” Industrial Relations, 21 (1), 1–32.

- Fishbein, Martin and Icek Ajzen. 1975. Belief, Attitude, Intention and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research. Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley.

- Fraser Forum. 2004. “Measuring Labour Markets in Canada and the United States.” Vancouver: The Fraser Institute: September, 1–12.

- Freeman, Robert, and John Medoff. 1984. What Unions Do. New York: Basic Books.

- Galt, Virgina. 2003. “Unions Covering Fewer of Canada’s Workers: Labour Movement Needs New Members to Stem.” Labour Reporter, Monday, October 13, B-1.

- Gartland, Gregory. 2002. “Of Ducks and Dissertations: A Call for a Return to the National Labor Relations Board’s ‘Primary Purpose Test’ in Determining the Status of Graduate Assistants Under the National Labor Relations Act.” University of Pennsylvania Labor and Employment Law Journal, 4, 624–643.

- Gomez, R., M. Gunderson and N. Meltz. 2001. From Playstations to Workstations: Youth Preferences and Unionization in Canada. Toronto: Centre for Economic Performance.

- Gordon, M. E., J. W. Philpot, R. E. Burt, C. A. Thompson and W. E. Spiller. 1980. “Commitment to the Union: Development of a Measure and an Examination of its Correlates.” Journal of Applied Psychology, 65, 474–499.

- Graduate Assistants Association. 1980. Handbook 1979/80. Toronto: GAA.

- Graduate Assistant’s Association (Applicant) v. Carleton University (Respondent) v. Carleton University Support Staff Association (Intervener). Ontario. Labour Relations Board. Decisions. February 1978, 179–183.

- Graduate Assistant’s Association (Applicant) v. McMaster University (Respondent). Ontario. Lbour Relations Board. Decisions. July 1979, 685–689.

- Graduate Assistant’s Association (Applicant) v. York University (Respondent). Ontario. Labour Relations Board. Decisions. September 1975, 683–689.

- Graduate Student Association Council. 2003. “Minutes of the Fourth Regular Meeting of the Graduate Student Association Council, 2003–04 Fiscal Year.” February 12, 2003, http://www.unb.ca/web/GSA/minutes/2002-2003/M02-12-03.html (accessed June 6, 2003).

- Grayson, J. 2001. Students Who Are Willing To Join Unions. Toronto: Centre for Research on Work and Society.

- Haberfeld, Yitchak. 1995. “Why Do Workers Join Unions? The Case of Israel.” Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 48 (4), 656–667.

- Haines, Phil. 2004. “Corporate Canada Enters the Academic Realm.” Brock Press, March 16.

- Hayden, Grant. 2001. “The University Works Because We Do: Collective Bargaining Rights for Graduate Assistants.” Fordham Law Review, 69, 1233–1264.

- Healy, Teresa. 2000. “Our Universities Work Because We Do: CUPE Comments on Ontario’s Bill 132.” October 26, 1–18.

- Hemmasi, Masoud, and Lee Graf. 1993. “Determinants of Faculty Voting Behavior in Union Representation Elections: A Multivariate Model.” Journal of Management, 19 (1), 13–32.

- Heneman, Herbert, and Marcus Sandver. 1983. “Predicting the Outcome of Union Certification Elections: A Review of the Literature.” Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 36 (4), 537–559.

- Kochan, Thomas. 1979. “How American Employees View Labor Unions.” Monthly Labor Review, 104 (4), 23–31.

- Kochan, Thomas. 1980. Collective Bargaining and Industrial Relations. Homewood, Ill.: Richard D. Irwin.

- Kuhling, Claric. 2002. “How CUPE 3903 Struck and Won.” Just Labour, 1, 77–85.

- Lafer, Gordon. 2003. “Graduate Student Unions: Organizing in a Changed Academic Economy.” Labor Studies Journal, 28 (2), 25–43.

- Laidler, David. 2002. Renovating the Ivory Tower: Canadian Universities and the Knowledge Economy. Policy Study 3. Ottawa: Renouf Publishing Company, April, 288.

- Lazarovici, Laureen. 2002. “Reaching out to the Future: Unions Develop Key Leadership Skills Among Young Workers.” American at Work.

- Leatherman, Courtney. 2000. “NLRB Ruling May Demolish the Barriers to TA Unions at Private Universities.” The Chronicle of Higher Education, 46, 18–20.

- Lipsig-Mumme, C. 1999. “The Language of Organizing: Trade Union Strategy in International Perspective.” Center for Research on Work and Society, Working Paper Series, No. 19, December.

- Lipsig-Mumme, C. 2001. “The Three Faces of Victory: The Unravelling Stops Here – How York Strikers Took on Privatization and Won.” Straight Goods, January 29, 1–3, www.straightgoods.com/item416.asp (accessed June 30, 2003).

- Lowe, Graham and Sandra Rastin. 2000. “Organizing the Next Generation: Influences on Young Workers’ Willingness to Join Unions in Canada.” British Journal of Industrial Relations, 38 (2), 203–222.

- MacDonald, Michael. 1999. “New Labour Leader Calls for Youth Drive.” The Canadian Press, May 7.

- Macredie, I, and J. Pilon. 2001. “A Profile of Union Members in Canada.” Paper presented at the International Conference on Union Growth, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, April 31-May 1.

- McCracken, Rosemary. 1973. “U of T Graduate Student Teachers Seek Union to Standardize Wages.” The Globe and Mail, December 11.

- Murdock, Rebecca. 1995. “Merger Mania: The Rise of Canada’s Super Unions.” Canadian Dimension, 29 (6).

- Murray, A., and Y. Reshef. 1988. “American Manufacturing Unions Statis: A Paradigmatic Perspective.” Academy of Management Review, 13, 615–626.

- Newton, Lucy, and Lynn Shore. 1992. “A Model of Union Membership: Instrumentality, Commitment, and Opposition.” Academy of Management Review, 17 (2), 275–298.

- OCUFA (Ontario Council of University Faculty Associations). 2002. Speaking notes as cited in CUPE: Solidarity in Action. http://www.cupe.ca/issues/education (accessed 01/06/2003).

- Ofori-Dankwa, Joseph. 1993. “Murray and Reshef Revisited: Toward a Typology/Theory of Paradigms of National Trade Unions.” Academy of Management Review, 18 (2), 269–284.

- Perlman, Selig. 1928. A Theory of the Labor Movement. New York: Macmillan.

- Premack, S., and J. Hunter. 1988. “Individual Unionization Decisions.” Psychological Bulletin, 103, 223–234.

- Queen’s News Centre. 2004. “Ballots Sealed for Labour Board Count.” Friday, February 6, 2004, http://qnc.queensu.ca/update/index.php (accessed March 3, 2004).

- Reigel, Sarah. n.d. “Looking Back on Trac: Organizing Queen’s.” http://www.louisville.edu/journal/workplace/issues5tracc.html (accessed June 6, 2003).

- Rogrow, Robert and Daniel R. Birch. 1984. “Teaching Assistant Unionization: Origins and Implications.” The Canadian Journal of Higher Education, 14, 11–29.

- Rohrbacher, Bernard. 2000. “After Boston Medical Center: Why Teaching Assistants Should have the Right to Bargain Collectively.” Loyola Law Review, 33, 1850–1916.

- Rose, Joseph B., and Gary N.Chaison. 2001. “Unionism in Canada and the United States in the 21st Century.” Relations Industrielles/Industrial Relations, 56 (1), 34–65.

- Rowland, Joshua. 2001. “Forecasts of Doom: The Dubious Threat of Graduate Teaching Assistant Collective Bargaining to Academic Freedom.” Boston College Law Review, 42, 942–970.

- Saltzman, Gregory. 2000. “Union Organizing and the Law: Part-time Faculty and Graduate Teaching Assistants.” The NEA 2000 Almanac of Higher Education, 43–55.

- Schofield, E. 2002. “Teachers on Strike.” Maclean’s, 113 (51), December 18, 45.

- Schofield, J. 2000. “A Tough Sell on Campus: Quebec Students Protest Corporate Encroachment.” Maclean’s, April 10.

- Senate. 1975. McGill University, Senate Document D5-37, 10th December 1975. AGSEM. 2004 “Archives: History of the First Contract Negotiation (1994–1997).” http://www.web.net/~agsem/history_hist_negotiation.htm (accessed December 22, 2004).

- Shaker, Erika. 2002. “OCUFA Forum: Ontario Confederation of University Faculty Association.” Forum, Fall, 11–15.

- Singh, Parbudyal, and Harish Jain. 2001. “Striker Replacements in Canada, the United States and Mexico: A Review of the Law and Empirical Literature.” Industrial Relations, 40 (1), 22–53.

- SPPRUL (Syndicat des professionnelles et professionnels de recherche de l’Université Laval). 2001. “Les professionnelles et professionnels de recherche: une force à l’Université Laval.” http://www.ulaval.ca/spprul/html/histo1.html (accessed June 30, 2003).

- Starnes, Colin. 2002. “Core Funding Lost in the Shuffle.” CAUT Bulletin, November, A12.

- Tannock, S., and S. Flocks. 2002. The Canadian Labour Movement’s Big Youth Turn. University of California, Berkeley: Canadian Youth in the Labour Movement.

- Task Force. 1999. Task Force on Graduate Student Employment Recognition, Representation, Rationalization, and Remuneration. Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research. University of Alberta, July.

- Tetrick, L.E. 1995. “Developing and Maintaining Union Commitment: A Theoretical Framework.” Journal of Organizational Behavior, 16, 583–596.

- Thompson, Clive. 1991. “TAs Back to Work.” The Varsity, March 18, 1,8.

- Tudiver, Neil. 1999. Universities for Sale: Resisting Corporate Control over Canadian Higher Education. A CAUT Series Title. Toronto: James Lorimer & Company, 248 p.

- University of Toronto Bulletin. 1974. “Provost Urges Teaching Assistants to Vote on ‘Serious’.” 27 (29), 17 May, 1–2.

- Wheeler, Hoyt, and John McClendon. 1991. “The Individual Decision to Unionize.” The State of the Unions. G. Strauss, D.Gallagher, and J. Fiorito, eds. Madison, Wisc.: Industrial Relations Research Association, 47–83.

- Yates, C.A.B. 2002. “Expanding Labour’s Horizons: Union Organizing and Strategic Change in Canada.” Just Labour, 6, 31–40.

- Yeates, Maurice. 2003. “Graduate Student Conundrum.” University Affairs, February, 28–29.

Liste des figures

Figure 1

Testing a Theory of Graduate Student Unionization in Canada

Liste des tableaux

Table 1

Graduate Student Union Locals in Canadian Universities, 2003

Table 2

Proportion of Unionized Students by School