Résumés

Abstract

The purpose of this paper was to examine the relationships among pay satisfaction, job satisfaction, and turnover. While there is a fairly large body of literature on pay satisfaction/dissatisfaction-turnover relationship, there are reasons to expect different outcomes in occupations – such as social work and nursing – where job satisfaction, versus pay, may be of equal, if not greater importance. Essentially, it may be argued that in these sectors, workers are driven more by job satisfaction rather than their paychecks. Yet, there is little empirical research on this issue; thus, a primary purpose of this study is to address this research need. This study will add to the recent research that has focused on key human resources management and industrial relations issues related to the nursing profession in Canada. Furthermore, many studies use a unidimensional measure of pay satisfaction even though the literature suggests that there are better measures. Using a four-dimensional instrument in this study, we improve on past practices.

Using a sample of 200 nurses in a unionized hospital in Ontario to test our hypotheses, we found support for both (viz., 1. The four pay dimensions will affect turnover intent differently; and 2. Job satisfaction will add incrementally to the explained variance in the pay satisfaction-turnover relationship). The findings support the contention that nurses may be more motivated by their jobs, versus their pay. The findings may be good news for organizations that want to better manage labour costs. There are different ways for hospitals to improve their workplace environment in order to increase satisfaction with intrinsic job factors and reduce turnover.

Keywords:

- pay satisfaction,

- equity and justice,

- job satisfaction,

- turnover intentions

Résumé

Cet article examine la relation entre la satisfaction à l’égard de la rémunération, la satisfaction au travail et le roulement de la main-d’oeuvre. Alors qu’il existe un corpus plutôt vaste de littérature sur la satisfaction/insatisfaction à l’égard de la rémunération, il y a des raisons de penser que les résultats pourraient différés pour certaines professions, comme dans le cas du travail social et celui des soins infirmiers, où la satisfaction au travail comparativement à celle à l’égard de la rémunération peut être d’importance égale ou même supérieure. Essentiellement on peut argumenter que dans ces secteurs, les travailleurs et travailleuses sont davantage motivés par la satisfaction au travail que par leur chèque de paie. Pourtant il y a peu de recherche empirique sur ce sujet. Un premier objectif de l’étude est de combler en partie du moins ce manque. Elle ajoutera ainsi aux études récentes qui mettent l’accent sur la gestion des ressources humaines clés dans les organisations et les problèmes de relations industrielles liées à la profession des soins infirmiers au Canada. Plusieurs études utilisent une mesure unidimensionnelle de la satisfaction à l’égard de la rémunération alors que la littérature suggère que de meilleures mesures pourraient être utilisées. Aussi en proposant une mesure à quatre dimensions, nous croyons pouvoir améliorer les pratiques passées de recherche dans ce domaine.

À partir d’un échantillon de 200 infirmiers et infirmières d’un hôpital torontois nous obtenons des résultats empiriques qui tendent à appuyer nos deux hypothèses, à savoir : 1) que chacune des quatre dimensions de la rémunération exerce un effet différent sur l’intention de quitter, et 2) que la satisfaction au travail constitue un facteur additionnel dans l’explication de la variance dans la relation satisfaction à l’égard de la rémunération-roulement (intention de quitter). Cela constitue un appui à l’argument que les infirmiers et les infirmières sont sans doute davantage motivés par les conditions d’exercice de leur travail que par leur rémunération. De tels résultats peuvent être une bonne nouvelle pour les organisations désireuses de mieux gérer leurs coûts de main-d’oeuvre puisqu’il y a différentes façons pour les hôpitaux d’améliorer l’environnement de travail dans le but d’accroître la satisfaction à l’égard des caractéristiques intrinsèques du travail et ainsi réduire le roulement du personnel.

Mots-clés :

- satisfaction à l’égard de la rémunération,

- équité et justice,

- satisfaction au travail,

- intention de quitter

Resumen

El propósito de este documento es de examinar las relaciones entre satisfacción del salario, satisfacción del empleo y cambio de empleo. Mientras existe una impresionante cantidad de literatura sobre la relación satisfacción/insatisfacción del salario y cambio de empleo, hay razones para esperar diferentes resultados en las ocupaciones tales como trabajo social y enfermería – donde la satisfacción del empleo, versus salario, puede ser de igual sino de mayor importancia. Esencialmente, puede argumentarse que en estos sectores, los trabajadores son más interesados por la satisfacción del empleo que por sus cheques de pago. Además, hay pocos estudios empíricos sobre esta problemática; así, un primer propósito de este estudio de responder a esta necesidad de investigación. Este estudio se añade a la reciente investigación que ha focalizado las problemáticas claves de gestión de recursos humanos y de relaciones industriales respecto a la profesión de enfermería en Canadá. Más aún, muchos estudios utilizan una medida unidimensional de la satisfacción del salario aunque la literatura sugiere que hay mejores medidas. Usando un instrumento de cuatro dimensiones en este estudio, se mejora las prácticas pasadas.

Se utiliza una muestra de 200 enfermeras en un hospital sindicalizado de Ontario para evaluar nuestras hipótesis siendo éstas validadas: 1. Las cuatro dimensiones de pago van afectar la intención de cambio de empleo de manera diferente; 2. La satisfacción del empleo aumenta la contribución para explicar la varianza en la relación satisfacción salarial – cambio de empleo. Estos resultados confirman el punto de vista que las enfermeras pueden estar más motivadas por sus empleo, versus sus salarios. Los resultados pueden ser buenas noticias para las organizaciones que quieren administrar mejor los costos del trabajo. Hay diferentes maneras en los hospitales de mejorar el ambiente en el lugar de trabajo de manera a aumentar la satisfacción con los factores intrínsecos del empleo y reducir así el cambio de empleo.

Palabras clave:

- satisfacción salarial,

- equidad y justicia,

- satisfacción del empleo,

- intención de cambio de empleo

Corps de l’article

Introduction

Pay satisfaction is of primary concern to both employers and employees. For employees, pay is of obvious importance in terms of satisfying their economic needs. It is important that they are satisfied with their overall pay as this may impact their attitudes and behaviours. As Heneman and Judge (2000: 85) concluded, “research has unequivocally shown that pay dissatisfaction can have important and undesirable impacts on numerous employee outcomes.” Employee dissatisfaction with pay, for instance, can decrease commitment to the job, increase stealing, and catalyze turnover (Currall et al., 2005; Greenberg, 1990; Miceli and Mulvey, 2000). For employers, some of whom may spend as much as 70-80% of their budget in wages and benefits in the service sector, the issue has implications for the survival of the organization if they do not get decent returns on their investments. Furthermore, an organization’s reward system is increasingly viewed as a strategic tool in aligning the interests of workers and management and improving firm performance; that is, organizations may use their pay system to motivate strategic behaviours (Lawler, 1971, 1990; Milkovich and Newman, 2008), making it crucial that employees are satisfied with their pay.

For many organizations, employee turnover is a key concern because of the time and money involved in addressing this issue, among other factors. It is the importance of this phenomenon, in part, that has led to turnover attracting immense scholarly attention. As Holtom, Mitchell and Lee (2008: 232) note, “…it is not surprising that turnover continues to be a vibrant field despite more than 1500 academic studies addressing the topic.” From a financial perspective, turnover can be very costly. When an employee leaves an organization, it forces it to spend scarce resources – both time and money – to either replace the employee, or get others to cover the work. Organizations spend a significant portion of their budgets recruiting and training new employees; estimates for the losses range from a few thousands to more than two times the person’s salary (Cascio, 2000; Hinkin and Tracey, 2000; Holtom, Mitchell and Lee, 2008). Some costs, such as the disruption of the organization’s daily operations and the emotional stress and, at times, the work overload it causes those who remain, are difficult to capture in monetary terms. Undesirable turnover can also project a negative image of the organization – both internal and external; thus, it is not surprising that voluntary turnover continues to attract the attention of scholars and practitioners alike.

While there is a fairly large body of literature on pay satisfaction/dissatisfaction-turnover relationship (see Williams, McDaniel and Nguyen, 2006, for a meta-analysis), there are reasons to expect different outcomes in occupations – such as nursing and social work – where intrinsic job satisfaction, versus pay, may be of equal, if not greater importance (Boughn and Lentini, 1999; Curtis, 2007; Green, 1988; Long, 2005). Dochery and Barns (2005) found that nurses were intrinsically driven to join the profession; they liked the idea of working with and helping people and they valued work for its inherent interest and importance, and not so much for its pay. Essentially, it may be argued that in these occupations, such as nursing, employees are driven more by job satisfaction rather than their paychecks. Yet, as Lum et al. (1998: 308) stated, “…as far as nurses are concerned, there are no studies which report the concurrent effects of pay supplements upon pay satisfaction and turnover intent.” A decade later, there has been little work done on this issue. In the nursing literature, most of the studies focus on other determinants of turnover (Bame, 1993; Barron and West, 2005; Brannon et al., 2002), but the consequences are similarly problematic as in other professions (Buerhaus, Staiger and Auerbach, 2003; Burnard, Morrison and Phillips, 1999; Chan and Morrison, 2000; Cheung, 2004; Curtis, 2007; Lynn and Redman, 2005; Lum et al., 1998; North et al., 2005; Shields and Ward, 2001). In summary, high turnover has a direct impact on organizational performance (Waldman et al., 2004), staff motivation and group cohesion (Mottaz, 1988), and the quality of patient care (Aiken et al., 2002; Buerhaus, Staiger and Auerbach, 2006).

This study will add to the recent research that has focused on key human resources management and industrial relations issues related to the nursing profession in Canada (Blythe et al., 2008; Zeytinoglu et al., 2007). As stated above, there is little or no research on this issue in occupations, such as nursing, where pay is perceived to be of secondary importance to employees. One explanation for the relative paucity of research on the pay satisfaction-turnover relationship is the notion that intrinsic job satisfaction (or how employees feel about the nature of the job tasks themselves) are the most valued aspects of nursing and that RNs are willing to “sacrifice” pay in favour of rewards such as supervisory excellence, good co-workers relations, promotional opportunities, recognition, and pride in their ability to express their skills and knowledge as a nurse (Seymour and Buscherhof, 1991).

In Canada, registered nurses (RNs) are the largest group of health care workers and as such are considered the foundation of Canadian healthcare. It is estimated that by 2011, Canada could be short 78,000 nurses, and by 2016, the shortage could reach epidemic proportions of 113,000 nurses (CNA, 2002). Although the nursing shortage is not a new phenomenon, prior shortages were managed by short-term planning. The current situation may demand a more long-term solution that addresses employee job satisfaction and pay, among other factors. As nursing shortages threaten the access to and the quality of patient care, healthcare managers and human resources professionals have the responsibility to implement practices that would increase staff retention. One component of a successful retention program is a satisfactory and competitive compensation package (Chan and Morrison, 2000; Currall et al., 2005; Lum et al., 1998; Sturman and Carraher, 2007). Thus, the second objective of this paper is to highlight how organizations may address the turnover problem, specifically through its link with pay and job satisfaction.

Third, there is considerable evidence that compensation satisfaction is a multidimensional construct although there is no universal agreement whether there are three (Carraher, 1991; Scarpello, Huber and Vandenberg, 1988), four (Heneman, Greenberg and Strasser, 1988; Heneman and Schwab, 1985; Judge, 1993; Scarpello, Huber and Vandenberg, 1988), or five (Garcia and Posthuma, 2009; Mulvey, Miceli and Near, 1992) dimensions. Yet, as Lum et al. (1998) note, many pay satisfaction-turnover studies have used unidimensional constructs to measure pay satisfaction (see for example, Keaveny and Inderrieden, 2000), or focused on only one aspect of pay satisfaction, usually pay level (see Williams, McDaniel and Nguyen, 2006, for a meta-analysis of pay level satisfaction). In the current study, we apply Heneman and Schwab’s (1985) Pay Satisfaction Questionnaire (PSQ), the most frequently used measure of multidimensional pay satisfaction, in order to examine the relationship between pay level, pay raise, benefits, and pay administration and turnover intent. Pay level refers to the individual’s current direct wage or salary, while pay raises refer to the individual’s change in pay level. Benefits reflect indirect pay to the individual such as health insurance and payment for time not worked. Pay structure/administration refers to the hierarchical relationships created among pay rates for different jobs within the organization and procedures by which the pay system is administered (Heneman and Schwab, 1985; Milkovich and Newman, 2008). We hope to broaden the understanding of the impact of different pay dimensions on turnover intent and expand on Tekleab, Bartol and Liu (2005) findings which demonstrated that pay level and pay raise, although related to each other, have independent effects on employee turnover intent. In their findings, only pay raise was significantly and negatively related to turnover. The present study elaborates on Tekleab, Bartol and Liu (2005) findings by applying Heneman and Schwab’s (1985) PSQ, looking at satisfaction with benefits and pay administration, in addition to satisfaction with pay level and pay raise.

In the following sections, we review the literature and develop the hypotheses, describe the methodology used, and present the results. Finally, the discussion section focuses on the reasons for some unexpected (and expected) results and limitations of the paper. Our findings also have practical implications for health care managers and human resources professionals, providing them with a better understanding of the importance of all aspects of pay satisfaction – pay level, benefits, pay raise and pay structure – in a successful retention plan.

Literature Review and Hypotheses

Pay Satisfaction and Turnover Intent

According to equity theory, pay satisfaction is based on perceptual and comparative processes (Adams, 1963; Lawler, 1990; Lum et al., 1998). Equity theorists posit that employees seek the equilibrium between what they invest or put into their jobs in terms of effort, knowledge and skills, and what they get as an outcome through compensation or recognition (Adams, 1963; Greenberg, 1987, 1990; Milkovich and Newman, 2008). Employees perceive what is fair by comparing their work to those with referent others, either internal to the organization (e.g. those holding similar positions within the same organization) or external (e.g. those holding similar positions with a different employer). Equity is achieved when the input-output ratio of the employee equals that of a referent other. What an individual selects as a reference depends on its availability and relevance. Lawler (1971) further suggests that satisfaction or dissatisfaction with pay is influenced by the discrepancy between what employees perceive they should receive for their inputs (or their pay) and what they contribute to the organization.

There are three outcomes when employees compare their input/output ratio with referent others that may influence their performance. In situations where the outcomes or outputs are perceived to exceed inputs, the individual is being over-rewarded. On the contrary, if inputs are perceived to exceed the outputs, the individual is being under-rewarded. The optimal situation is when inputs equal outputs and the reward is considered equitable. If the input-output ratio is not in balance, individuals will experience distress caused from guilt of being over-rewarded or the feelings of resentment from being under-rewarded, and these feelings will serve as a motivational factor leading to restoration of equity (Greenberg, 1987, 1990; Huseman, Hatfield and Miles, 1987; Huseman and Hatfield, 1990). Employees who feel under-rewarded will attempt to restore equity by reducing inputs such as increasing absenteeism, coming late to work, taking longer breaks, and decreasing productivity, or by leaving the organization, all of which are very costly for an employer (Greenberg, 1990).

In addition to equity theory, the literature on organizational justice is pertinent in this review, especially two of its key components used to evaluate fairness: distributive justice and procedural justice (Fassina, Jones and Uggerslev, 2008; Greenberg, 1990; Tekleab, Bartol and Liu, 2005; Van Buren, 2008; Welbourne, 1998). Distributive justice applies to the fairness of the outcome or, in the current study, the amount paid/pay level. Procedural justice is a process-oriented construct used to evaluate the fairness of methods and appraisal systems, such as rules and procedures that are implemented to determine the amount paid (Miceli and Mulvey, 2000; Singh, Fujita and Norton, 2004), or in this study, the organization’s pay structure/administration, pay raises, and benefits determination. Tekleab, Bartol and Liu (2005) found that distributive justice mediates the relationship between the overall pay satisfaction and satisfaction with pay level and pay raise, while procedural justice was a strong predictor of pay raise only. Since there is evidence that different cognitive processes are used in evaluating different components of pay satisfaction (Judge, 1993), it is reasonable to believe that these pay dimensions are somewhat independent from one another and as such will have independent impact on turnover intent.

Given the foregoing, we can rationalize that pay satisfaction is caused, in part, by perceptions regarding the equity of one’s pay. Pay satisfaction can be seen as a surrogate for fairness and justice, which in return has a direct impact on employees’ motivation and therefore their job satisfaction (Eby et al., 1999). Fairness and perceived pay equity, in addition, are linked to organizational commitment and turnover (Brooke, 1986; Greenberg, 1987; Rhodes and Steers, 1981; Williams, McDaniel and Nguyen, 2006). Hence, the degree to which an individual is committed to their employer can be enhanced by an individual’s perception of how they are rewarded for their inputs.

In terms of the empirical research, most of the studies on pay satisfaction and turnover report a negative relationship (see Williams, McDaniel and Nguyen, 2006 for a meta-analysis). That is, turnover/turnover intent decreases with improvements in pay satisfaction, and vice versa (Dailey and Kirk, 1992; Motowildo, 1983). While Bevan, Barber and Robinson (1997) found little difference in terms of pay satisfaction between people who stay and those who leave the organization, other studies found differences (Cameron, Horsburgh and Armstrong-Strassen, 1994; Gardulf et al., 2005; Grant et al., 1994; Hom and Griffith, 1995; Seymour and Buscherhof, 1991). Lum et al. (1998) further found that pay satisfaction had both direct and indirect effects on turnover intent.

While research has indicated that different pay components reflect distinct aspects of pay satisfaction and may have different consequences in terms of the extent/degree of this relationship (Tekleab, Bartol and Liu, 2005), the overall direction of the relationship is always projected as negative. However, the four dimensions may have differential impact on organizational outcomes, including turnover. Judge (1993) demonstrated that the four dimensions of the PSQ are empirically separable and that a combination of even the most highly related dimensions will result in loss of important information on the causes of pay satisfaction. Furthermore, even the cognitive processes governing evaluation of pay fairness are different for different pay components. Previous studies have shown that distributive justice has more direct effects on pay level satisfaction (Sweeney and McFarlin, 1993) while procedural justice is a strong predictor of pay raise (Tekleab, Bartol and Liu, 2005).

Theoretically, procedural justice may have a greater impact on turnover intentions versus distributive justice. That is, employees may view the procedures that influence their pay as more important in potential withdrawal decisions versus the amount they receive (Greenberg, 1990). This is especially pertinent in environments where pay does not significantly differ across organizations (as the nursing sector in Ontario’s hospitals). They may view their absolute pay as the best in the circumstances, and focus more on the processes involved, as well as aspects other than pay that relate to their work. Thus, the pay satisfaction dimensions that relate to procedural justice, viz., pay raises, benefits, and pay structure/administration, will have a more intense negative effect on turnover intentions, versus pay level (which relates more to distributive justice). For instance, employee benefits tend to accumulate over time usually as a result of group representation processes – through collective bargaining or political gains from group pressures at the organizational and societal levels. As Tremblay, Sire and Balkin (2000: 273) posit,

…many employee benefits become more valuable over time, such as vacation time, the right to take sabbaticals, or retirement plans. As the employee invests more time in the organization, these benefits increase in value, rewarding the employee for his or her loyalty to the firm. We expect the procedures that govern the use of employee benefits to be more salient to employees than the outcomes of using the benefits.

Similarly, given that nurses may view pay levels as less important than other aspects of their work (Dochery and Barns, 2005), the issues related to “the way the organization administers pay”, “the pay structure,” “information shared about pay issues of concern,” and “consistency of the pay policies,” – all items in the pay structure dimension (Heneman and Schwab, 1985) – assume even greater importance in organizational outcomes, including turnover.

From the foregoing, it is expected that the pay satisfaction dimensions/components will relate to turnover intentions in the same direction (negative) but given their conceptual differences, the intensity (size effect) of this relationship will vary. Thus, it is hypothesized that:

HYPOTHESIS 1: While the general relationship between pay satisfaction and turnover will be negative, the effects (size) will be different.

Pay Satisfaction, Job Satisfaction, and Turnover Intent

There is a large body of literature on the pay and job satisfaction relationship (Ago, Mueller and Price, 1993; Tremblay, Sire and Balkin, 2000; Weiner, 1980) and the job satisfaction-turnover relationship in the management and industrial relations literature (see for instance, Lum et al., 1998; Mobley et al., 1979). Equity theory and organizational justice have been generally used to theoretically explain these relationships. In summary, and as mentioned above, employees who feel under-rewarded will attempt to restore equity by reducing inputs such as increasing absenteeism, coming late to work, taking longer breaks, and decreasing productivity, all of which are very costly for an employer (Greenberg, 1990; Lawler, 1990; Lum et al., 1998). For employers, some interventions that may restore equity for those who perceive being under-paid is to increase outcomes such as pay and benefits, promotional opportunities and job security, and offer better working conditions. Since many employees have limited or no influence on the outcomes, they may simply quit their jobs after trying and failing to restore equity (Greenberg, 1987). However, as Vandenberghe and Tremblay (2008: 276) point out, “research on the link between pay satisfaction and intended and actual turnover has been limited. Moreover, most of that research has focused on satisfaction with pay level and use an undifferentiated measure of pay satisfaction.” Consequently, they focused on how organizational commitment influences this relationship. In this study, we focus on job satisfaction.

In the nursing literature, several studies have found that wages and salaries impact overall job satisfaction but rarely went a step further to determine the relative importance between job and pay satisfaction in terms of their effects on turnover (Carr and Kazanowski, 1994; Frisina, Murray and Aird, 1988; Fung-kam, 1998; Huey and Hartley, 1988). For instance, Fung-kam (1998) found that the three factors that have the most influence on job satisfaction were autonomy, professional status, and pay. Many studies do not find pay to be associated with overall job satisfaction among RNs (Butler and Parsons, 1989; Cavanagh, 1992; Reineck and Furino, 2005). On the contrary, Williams (1990) and Best and Thurston (2006) found pay satisfaction and autonomy the most important components of overall job satisfaction in a sample of Canadian nurses. In terms of the studies that attempted to assess the relative importance of job and pay satisfaction, most – if not all – treat pay satisfaction as a unidimensional construct. For instance, Curtis (2007) found that pay level made the least contribution to nurses’ current level of satisfaction.

The pay satisfaction-turnover nursing literature, even though it is in its infancy, reveals a consistent relationship. Lum et al. (1998) found that pay satisfaction had a negative relationship with turnover intent in a sample of 361 Canadian RNs. Seymour and Buscherhof (1991) reported that nurses rated remuneration (pay and fringe benefits received for the work done) as the second most important job factor, and more important than interactions with others and work autonomy. In the same study, 29.6% of nurses indicated their pay dissatisfaction as the major reason for leaving the profession. The emerging research indicates that pay satisfaction is a determinant of turnover intent (theoretically explained in the preceding section). However, most of these studies use a unidimensional measure of pay satisfaction and this is compounded by the fact that there are only a few studies on the pay satisfaction-turnover relationship among nurses (Lum et al., 1998). Furthermore, there is a need to test the incremental effects of job satisfaction on the pay satisfaction-turnover relationship. There was no need to hypothesize on the direct job satisfaction-turnover relationship; as Lum et al. (1998: 308) concluded, “…the relationship between satisfaction and turnover has been consistently found in many turnover studies. However, it usually accounts for less than 16 per cent of the variance in turnover…it is apparent that models of the employee turnover process must move beyond satisfaction as a primary explanatory variable.” Thus, we will test for the incremental effects of intrinsic and extrinsic job satisfaction (excluding pay), over pay satisfaction, on turnover. Given the theoretical arguments (discussed earlier) and empirical research on the job satisfaction-turnover relationship, it is hypothesized that:

HYPOTHESIS 2: Job satisfaction will add incrementally to the explained variance in the relationship between pay satisfaction and turnover intent.

Methods

Sample and Procedures

Previously used reliable and valid measures were utilized to develop a questionnaire (a copy may be requested from the first author). The survey had a total of 38 questions divided in three sections. The first eight questions sought to identify participants’ demographics. The second section asked the participants to identify their level of satisfaction with regard to their pay level, pay raise, benefits, and structure/administration, as well as job satisfaction. A five point Likert Scale with five being “Very Satisfied” and one being “Very Dissatisfied” was used to rate the levels of satisfaction. The final section included four questions that were aimed at identifying the respondents’ turnover intent.

The survey was conducted in a hospital in Toronto, Ontario (Canada), where RNs are unionized under the Ontario Nursing Association. For this study, only full-time and part-time RNs providing direct patient care in the in-patient units were considered. A total of 583 surveys were distributed to 455 full time and 128 part time RNs who were randomly selected from the list of all full-time and part-time RNs employed in in-patient units. The questionnaire was delivered in their mailboxes asking for voluntary participation. Two hundred and two nurses completed and returned the questionnaire (a 35% response rate), of which 200 were usable.

Of this sample, 160 (81.2%) were employed as regular full time RNs. There were no statistically significant differences between the full- and part-time nurses on the key variables of this study (for instance, see the effects of the employment status variable in Tables 1 and 2), thus the full sample was treated as homogenous. This is not surprising since part-time nurses in Ontario have similar pay levels and working conditions as their full-time counterparts. Female RNs comprised 93.4% of the sample. Eleven percent of the respondents were between 18 and 25 years old, 35% were between 26 and 35 years old, 28% were between 36 and 45 years old, and 26% were 46 years of age or older. Respondents were in the nursing profession ranging between 3 months to 41 years with a mean of 13.6 years. On average, they worked for the hospital for 8.2 years. With respect to the highest education level achieved, 44% had a college diploma and 52% had a bachelors’ degree in nursing. Slightly more than half (54%) reported being married.

Measures

Turnover Intent: Research shows that behavioral intentions of turnover are strongly related to actual turnover (Irvine and Evans, 1995) and as such, turnover intent has been widely accepted as an outcome measure (Firth et al., 2004; Hart, 2005; Irvine and Evans, 1995; Lum et al., 1998).

Four items were used to measure turnover intent. Three were adapted from Lum et al. (1998) to fit the nursing context; these items asked participants to identify how likely is it that they seriously thought about looking for: a) another job at another hospital; b) a non-nursing job; and c) taking everything into consideration how likely is it that they will make a serious effort to find a new job within the next year. A final question was added in order to identify the likelihood of the participants finding nursing jobs outside Canada (How likely are you to look for a nursing job outside Canada?). The yes/no questions in the Lum et al. (1998) study were modified to allow for the use of the Likert Scale. All four turnover intent questions were rated using a 5-point Likert Scale with five being “Very Likely” and one being “Very Unlikely” to rate the likelihood of the nurses leaving. The Cronbach ? estimate of the 4-item turnover intent measure was .78.

Pay Satisfaction: Heneman and Schwab’s (1985) four dimensional Pay Satisfaction Questionnaire was used to measure pay satisfaction. There were four questions on pay level (e.g. How satisfied are you with your current salary? How satisfied are you with the size of your current salary?); four questions on pay raise (e.g. How satisfied are you with the way your pay raises are determined? How satisfied are you with the raises you have typically received in the past?); four questions on benefits (e.g. How satisfied are you with the number of benefits you receive? How satisfied are you with the value of your benefits?); and six questions on pay structure/ administration (e.g. How satisfied are you with the way the organization administers pay? How satisfied are you with the differences in pay among jobs in the hospital?). The Cronbach ? estimates of internal consistency for Pay Level, Pay Raise, Benefits, and Pay Administration were .91, .83, .93, and .90, respectively.

Job Satisfaction: A 5-item measure was used to assess job satisfaction. The items included aspects of both intrinsic satisfaction and extrinsic satisfaction (but excluded pay, generally regarded as an extrinsic motivator). The first four items were: satisfaction with the work itself; promotional opportunities; the way you are being supervised; and the level of satisfaction with coworkers. Given that the potential number of job satisfaction factors is probably limitless, we selected four items that are recognized in the research as being of vital importance for nurses’ job satisfaction (Kleinman, 2004; Laschinger et al., 2004; Shields and Ward, 2001). These four items were extracted from Smith-Randolph (2005), who used them in a nursing context and are very similar to many in the Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire and the Job Descriptive Index. An overall job satisfaction item was added (Overall, how satisfied are you with your job?), which adds to the overall reliability of the scale (Nagy, 2002; Scarpello and Campbell, 1983; Wanous, Reichers and Hudy, 1997). The alpha coefficient for the job satisfaction scale was .77.

Controls: Control variables included employment status, number of years in the profession, marital status, and education. While important, these variables were not the focus of this study but were included because they can affect the hypothesized relationships.

Data Analysis

The data were first analyzed using descriptive statistics and reliability analysis. The hypotheses were tested using regression analyses. In the regressions, control variables were first entered, followed individually by the pay satisfaction variables (to test the first hypothesis). To test Hypothesis 2 (job satisfaction will add incrementally to pay satisfaction), hierarchical regression analyses were used to assess nurses’ turnover intent as influenced by demographics (controls), satisfaction with the four pay dimensions, and job satisfaction. Job satisfaction was entered last, after the other variables were entered as a block.

Results

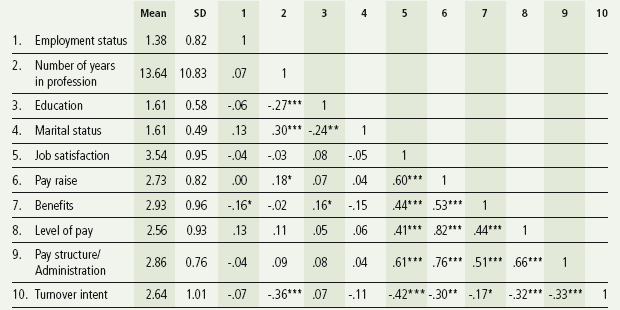

Table 1 shows the means, standard deviations, and correlations. As shown, pay raise (r = -.30, p < .01), benefits (r = -.17, p < .01), pay level (r = -.32, p < .01), and pay structure/administration (r = -.33, p < .01) are all significantly correlated with turnover intent. Job satisfaction is also negatively related with turnover intent at a significant level (r = -.42, p < .01). While this raises some concern about common method bias, a Harman test commonly used to assess common variance (Podsakoff et al., 2003) suggests that the items are different (e.g., no single factor explained more than 40% of the variance).

While not directly related to the hypotheses, a few other correlations/relationships between the nurses’ demographics and the pay dimensions are interesting. Pay raise is the only significant pay dimension correlated with the number of years in profession (r = .18, p < .05), suggesting that more experienced nurses are more satisfied with their pay raise but not with the other three pay dimensions. Education is positively related to benefits satisfaction (r = .16, p < .05).

Table 1

Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations

Hypothesis 1 suggested that while the overall relationship between pay satisfaction and turnover will be negative, the effects will be different. There is support for this hypothesis. Each of the four pay dimensions was entered into a model separately, with the four demographic controls (employment status, years in profession, marital status, and education), to assess its unique effects on turnover. The regression results also show that, while negative, the four dimensions have different effects on turnover intent (Table 2; Models 1, 2, 3 and 4). Model 6 (which includes all the pay satisfaction dimensions as a block) provides an interesting tale, one that supports Hypothesis 1. That is, only two of the dimensions – pay structure/administration and pay raise – retain their significance. These dimensions are usually associated with procedural justice. However, the fairly high inter-correlations may have influenced the results, thus they should be interpreted with caution.

Table 2

Hierarchical Regression: Turnover Intent (Dependent Variable)

The regression results testing the incremental effects are also shown in Table 2. In Model 1, the four demographic variables were entered (employment status, number of years in profession, education, and marital status) and the only variable that had a significant association with turnover intent was number of years in profession β = -.36, p < .001). Satisfaction with pay level was added in Model 2 and was found to be significant (β = -.28, p < .001) with a .07 change in adjusted R2 over Model 2. In Models 3, 4 and 5, satisfaction with pay structure/administration, satisfaction with benefits, and satisfaction with pay raise were assessed separately; all were significant in explaining turnover intent (pay structure/administration ? = -.31, p < .001; benefits: β = -.19, p < .01; pay raise: β = -.24, p < .01 ). In each instance, the pay component added significantly to Model 1 (controls) in terms of adjusted R-square. In Model 6 (base model to compare with Model 7), all the pay dimensions were entered as a block, followed by job satisfaction (Model 7). As can be seen, job satisfaction was significant (β = -.49, p < .001; R2 = .37; adj. R2 = .31). There is an increase of .14 in adjusted R-square between models 6 and 7, suggesting support for Hypothesis 2 (job satisfaction adds incrementally to pay satisfaction in explaining turnover). Once job satisfaction is entered, only two of the pay dimensions/components remain statistically significant (pay raise and pay level).

Discussion and Conclusions

As the results reveal, pay satisfaction is negatively related to turnover but the intensity of these relationships vary. Essentially, the results support previous findings that the four dimensions are conceptually different and as such will have different impact on various outcome measures, including turnover (Heneman and Schwab, 1985; Judge, 2003; Tekleab, Bartol and Liu, 2005). This suggests that the cognitive processes involved in judging fairness vary by pay component (Sweeny and McFarlin, 1993; Tekleab, Bartol and Liu, 2005).

As the results further show, both pay satisfaction and job satisfaction influence turnover among nurses. It is thus important that all aspects of pay – level, structure, benefits and raises – be taken into consideration in dealing with this issue. This study further suggests, however, that increases in compensation alone may not be sufficient to decrease turnover. The results support the findings by Shields and Ward (2001) who reported that job satisfaction is a more important determinant of the intention to quit amongst unionized RNs, versus their compensation. As noted in the introductory and literature review sections, there is a likelihood that some professionals, such as nurses, may be more attached to their jobs and display less propensity to quit because of the satisfaction they get from “their calling” (Boughn and Lentini, 1999; Dochery and Barns, 2005; Green, 1988). Thus, they may be more willing to endure the agonies of pay dissatisfaction, once their job satisfaction is kept intact, than employees in other occupations in general, where the pay dissatisfaction-turnover evidence is “unequivocal” (Heneman and Judge, 2000).

While this study found that all four dimensions of pay satisfaction/dissatisfaction are important factors in influencing turnover, the strengths of the relationships become truncated when job satisfaction is considered. This diminished effect of pay dissatisfaction on turnover intent may lie in the compensation determination process in a unionized environment, viz., through collective bargaining, and in this case between the Ontario Nurses Association and the Ontario Hospital Association. That is, this study may help to demonstrate how unions help to “take wages out of competition.” Scholars and practitioners have historically argued that a union’s key role is to standardize wages across units they represent thus taking away pay as a tool that may be manipulated by management (Commons, 1909; Gunderson, 1998; Kuttner, 1997; Renaud, 1998).

Within the framework of equity theory, the union environment can influence RNs pay satisfaction in three ways: perceived lack of control over input-output equilibrium, lack of relevant and attractive referent sources, and inflated perception of fairness (Gomez-Mejia and Balkin, 1984). Unionized employees are aware that regardless of their performance (inputs), their pay (outputs) will remain the same simply because wages are determined by collective bargaining and it is beyond the control of their supervisors. In a unionized environment, differences in the level of pay are typically determined by seniority. It is also plausible that unionized employees do not have referent sources readily available. In this case, all ONA members across the province of Ontario are paid relatively the same, which reduces the range of reference sources used for pay comparison. If the referents receive the same wage that is in accordance with the principles and strategies of the common union (ONA), then the RNs may be aware that their pay level will not change if they look for employment at a different hospital. It is likely that nurses’ knowledge that compensation is relatively the same, regardless of employer, makes pay satisfaction less salient when making a decision to quit. That is, with pay at comparatively similar levels in competing hospitals, the lure of better pay is diminished. What becomes important is the improvement in the work environment. Referring back to equity theory, it can be argued that in order to bring the input-output ratio to equilibrium, employees may reduce their inputs but they may also strive to increase their outputs whether they are defined as an increase in pay or improvement in the work conditions. It is also possible that the presence of a union positively affects the perception of fairness due to members’ right to a grievance procedure should they think managements’ actions are unfair (Miceli and Mulvey, 2000).

There are three potential limitations to the study. First, there is a limit on generalizing the results to other situations. The sample for this study came from one city hospital where RNs are unionized. Larger and more representative samples of RNs are needed in future studies. This study does not provide insights on the relation between pay satisfaction and turnover intent among the non-unionized workforce. Previous research suggests that union members are, in general, more satisfied with their pay than non-union members since, as already mentioned, union membership can influence perception of pay satisfaction in several ways (Gomez-Mejia and Balkin, 1984). Further research is required in both unionized and non-unionized environments. The second potential limitation of this study is in the application of Heneman and Schwab’s (1985) PSQ in a unionized environment. Questions pertaining to satisfaction with the supervisor’s influence on pay raise or satisfaction with the pay level of other jobs in the hospital seemed to be irrelevant for this sample. Based on these findings, it is highly plausible that unionized environments would require the use of different research instruments. Finally, given that this was a cross-sectional study, with all the responses coming from a single source/questionnaire, it is possible that common method bias may exist. However, as mentioned in the results section, statistical tests suggest that this is not a major problem. The results also suggest that the five key independent variables relate quite differently with turnover intent. Furthermore, the items emanated from established measures, and the pay satisfaction dimensions are conceptually different constructs – all of which help to reduce common method errors (Podsakoff et al., 2003; Spector, 2006).

There are several implications for practice. Since the results provide strong evidence that job satisfaction – both intrinsic and extrinsic – is a very important determinant of intention to quit amongst unionized RNs, retention strategies should also focus on increasing job satisfaction (and not just increasing pay and benefits). Organizations have to ensure their environments encourage staff RNs to effectively utilize their knowledge, expertise, and skills in order to deliver quality patient care.

It is agreed that the current nursing shortage is a product of multiple factors at various levels; economic, workplace, social, and demographic changes in Canadian society have contributed to the complexity of the situation. The structural and organizational changes in the 1990s had severe impacts on the Canadian health care system as thousands of healthcare workers lost their jobs during the nation-wide bed closures in order for hospitals to meet their financial commitments. As a result, a significant proportion of Canadian nurses left the country seeking employment elsewhere, mostly in the US (Hagerman, 2005; CNA, 2005), while many have left the profession altogether (Bauman et al., 2001). The most prominent trends affecting the present state and the future of Canadian healthcare is the recent history of healthcare funding trends, changing demographics and low enrolment in nursing education programs. Thus, retention strategies need to go beyond the workplace.

However, health care professionals and managers have some control over the workplace and can influence retention. There are different ways for hospitals to improve their workplace environment in order to increase job satisfaction and reduce turnover. For instance, it is important for the hospital to have a supportive infrastructure that fosters professional accountability and empowers nurses in their roles (Upenieks, 2005) and have a job environment that enhances respect and recognition of nurses, improves communication between nurses and management, and enhances professional development and decision-making opportunities (Johnson, 2000). Nurses are striving for greater autonomy and control over their environment, and participation in the decision-making process (Finn, 2001; Lum et al., 1998; Upenieks, 2005). They also want organizations to clearly communicate their intentions, activities and performance (Lum et al., 1998), and provide more respect and recognition of continued contributions (Upenieks, 2005). Constructive ways to spread formal power that allow for more autonomy and greater control of the workplace can be achieved through participatory management or shared governance models (Upenieks, 2005). In addition, organizations in which nurses are empowered to practice their profession to their full potential also optimize conditions for providing safe patient care (Armstrong and Laschinger, 2006).

Development and implementation of long term retention strategies are pivotal in ensuring that the health care institutions will be able to provide access to the variety of health care services. Successful retention strategies need to address those issues that are important to nurses. Current research, although rich with evidence pertaining to the importance of job satisfaction, is not conclusive when it comes to its importance on the pay satisfaction-turnover intent relationship. This study contributed to the existing literature by providing evidence that both pay satisfaction (all four components) and job satisfaction are important. Given that the presence of a union may have influenced the results, and that this study was restricted to one hospital, future studies should attempt to compare pay satisfaction and turnover intent between unionized and non unionized nurses across health care establishments in order to better understand how pay satisfaction impacts turnover intent in a wide variety of organizations.

Parties annexes

Notes biographiques

Parbudyal Singh

Parbudyal Singh is Associate Professor, School of Human Resource Management, York University, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Natasha Loncar

Natasha Loncar is a graduate from the Masters in Human Resource Management program, School of Human Resource Management, York University, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Bibliography

- Adams, J.S. 1963. “Toward an Understanding of Inequity.” Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 67, 422-436.

- Ago, A., C. Mueller and J. Price. 1993. “Determinants of Job Satisfaction: An Empirical Test of a Causal Model.” Human Relations, 46, 1007-1027.

- Aiken, H.L., S.P. Clarke, D.M. Sloane, J. Sochalski and J.H. Silber. 2002. “Hospital Nurse Staffing and Patient Mortality, Nurse Burnout, and Job Dissatisfaction.” The Journal of the American Medical Association, 288 (16), 1987-1993.

- Armstrong, K.J., and H. Laschinger. 2006. “Structural Empowerment, Magnet Hospital Characteristics, and Patient Safety Culture: Making the Link.” Journal of Nursing Care Quality, 21 (2), 124-135.

- Bame, S.I. 1993. “Organizational Characteristics and Administrative Strategies Associated with Staff Turnover.” Health Care Management Review, 18 (4), 70-87.

- Barron, D., and E. West. 2005. “Leaving Nursing: An Event-History Analysis of Nurses’ Careers.” Journal of Health Services Research and Policy, 10 (3), 150-157.

- Baumann, A., L. O’Brien-Pallas, M. Armstrong-Stassen, J. Blythe, R. Bourbonnais, S. Cameron, D. Irvine Doran, M. Kerr, L. McGilis Hall, M. Vézina, M. Butt and L. Ryan. 2001. Commitment and Care: The Benefits of a Healthy Workplace for Nurses, their Patients and the System. Ottawa: Canadian Health Services Research Foundation.

- Best, M.F., and N.E. Thurston. 2006. “Canadian Public Health Nurses’ Job Satisfaction.” Public Health Nursing, 23 (3), 250-255.

- Bevan, S., L. Barber and D. Robinson. 1997. Keeping the Best: A Practical Guide to Retaining Key Employees. London, UK: Grantham Book Services.

- Blythe, J., A. Baumann, I. Zeytinoglu, M. Denton, N. Akhtar-Danesh, S. Davies and C. Kolotylo. 2008. “Nursing Generations in the Contemporary Workplace.” Public Personnel Management, 37 (2), 137-156.

- Boughn, S., and A. Lentini. 1999. “Why Do Women Choose Nursing?” Journal of Nursing Education, 38, 151-161.

- Brannon, D., J.S. Zinn, V. Mor and J. Davis. 2002. “An Exploration of Job, Organizational, and Environmental Factors Associated with High and Low Nursing Assistant Turnover.” The Gerontologist, 42 (2), 159-169.

- Brooke, P.P. Jr. 1986. “Beyond the Steers and Rhodes Model of Employee Attendance.” Academy of Management Review, 11, 345-361.

- Buerhaus, P.I., D.O. Staiger and D.I. Auerbach. 2003. “Is the Current Shortage of Hospital Nurses Ending? Emerging Trends in Employment and Earnings of Registered Nurses.” Health Affairs, 22 (6), 191-198.

- Buerhaus, P.I., K. Donelan, B.T. Ulrich, L. Norman and R. Dittus. 2006. “State of Registered Nurse Workforce in the United States.” Nursing Economics, 24 (1), 6-12.

- Burnard, P., P. Morrison and C. Phillips. 1999. “Job Satisfaction Among Nurses in an Interim Secure Forensic Unit in Wales.” Australian and New Zealand Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 8, 9-18.

- Butler, J., and R.J. Parsons. 1989. “Hospital Perception of Job Satisfaction.” Nursing Management, 20 (8), 45-48.

- Cameron, S.J., M.E. Horsburgh and M. Armstrong-Strassen. 1994. “Job Satisfaction, Propensity to Leave and Burnout in RNs and RNAs: A Multivariate Perspective.” Canadian Journal of Nursing Administration, 7, 43-64.

- Carr, K.K., and M.K. Kazanowski. 1994. “Factors Affecting Job Satisfaction of Nurses Who Work in Long-Term Care.” Journal of Advanced Nursing, 19, 878-883.

- Carraher, S.M. 1991. “A Validity Study of Pay Satisfaction Questionnaire (PSQ).” Educational and Psychological Measurement, 51, 491-495.

- Cascio, W. 2000. Costing Human Resources: The Financial Impact of Behavior in Organizations. Cincinnati, OH: Southwestern.

- Cavanagh, S.J. 1992. “Job Satisfaction of Nursing Staff Working in Hospitals.” Journal of Advanced Nursing, 17, 704-711.

- Chan, E.Y., and P. Morrison. 2000. “Factors influencing the Retention and Turnover Intentions of Registered Nurses in a Singapore Hospital.” Nursing and Health Sciences, 2, 113-121.

- Cheung, J. 2004. “The Decision Process of Leaving Nursing.” Australian Health Review, 28 (3), 340-340.

- CNA (Canadian Nurses Association). 2002. Planning for the future: Nursing Human Resources Projections. Ottawa, Canada: CNA.

- CNA (Canadian Nurses Association). 2005. Highlights of 2003 Nursing Statistics. < http://www.cna-nurses.ca/CNA/documents/pdf/publications/CNA_HHR_Fact_Sheet_e.pdf > (accessed July 25, 2005).

- Commons, J. 1909. “American Shoemakers, 1648-1895.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 24 (November).

- Currall, S.C., A.J. Towler, T.A. Judge and L. Kohn. 2005. “Pay Satisfaction and Organizational Outcomes.” Personnel Psychology, 58 (3), 613-640.

- Curtis, E.A. 2007. “Job Satisfaction: A Survey of Nurses in the Republic of Ireland.” International Nursing Review, 52, 92-99.

- Dailey, R., and D. Kirk. 1992. “Distributive and Procedural Justice as Antecedents of Job Dissatisfaction and Intent to Turnover.” Human Relations, 45, 305-317.

- Dochery, A., and A. Barns. 2005. “Who’d be a Nurse? Some Evidence on Career Choice in Australia.” Australian Bulletin of Labour, 31 (4), 350-383.

- Eby, L.T., D.M. Freeman, M.C. Ruch and C.E. Lance. 1999. “Motivational Bases of Affective Organizational Commitment: A Partial Test of an Integrative Theoretical Model.” Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 72, 463-483.

- Fassina, N., D. Jones and L. Uggerslev. 2008. “Meta-Analytic Tests of Relationships Between Organizational Justice and Citizen Behavior: Testing Agent-System and Shared Variance Models.” Journal of Organizational Behavior, 29, 805-828.

- Finn, C.P. 2001. “Autonomy: An Important Component for Nurses’ Job Satisfaction.” International Journal of Nursing Studies, 38, 349-357.

- Firth, L., D.J. Mellor, K.A. Moore and C. Loquet. 2004. “How Can Managers Reduce Employee Intention to Quit?” Journal of Managerial Psychology, 19 (1/2), 170-187.

- Frisina, A., M. Murray and C. Aird. 1988. What Do Nurses Want? A Review of Satisfaction and Job Turnover Literature. The Nursing Manpower Task Force of the Hospital Council of Metropolitan Toronto Report, Toronto, Ontario.

- Fung-kam, L. 1998. “Job Satisfaction and Autonomy of Hong Kong Registered Nurses.” Journal of Advanced Nursing, 27, 355-363.

- Garcia, M., and R. Posthuma. 2009. “The Five Dimensions of Pay Satisfaction in a Maquiladora Plant in Mexico.” Applied Psychology, 58 (4), 509-519.

- Gardulf, A., I.L. Soderstrom, M.L. Orton, L. Eriksson, B. Arnetz and G. Nordstrom. 2005. “Why Do Nurses at a University Hospital Want to Quit their Jobs?” Journal of Nursing Management, 13, 329-337.

- Gomez-Mejia, L.R., and D.B. Balkin. 1984. “Faculty Satisfaction with Pay and Other Job Dimensions Under Union and Nonunion Conditions.” Academy of Management Journal, 3, 591-602.

- Grant, G., M. Nolan, B. Maguire and E. Melhuish. 1994. “Factors Influencing Job Satisfaction among Nurses.” British Journal of Nursing, 3, 615-620.

- Green, K. 1988. “Who Wants to be a Nurse?” American Demographics, 10, 46-49.

- Greenberg, J. 1987. “A Taxonomy of Organizational Justice Theories.” Academy of Management Review, 12, 9-22.

- Greenberg, J. 1990. “Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow.” Journal of Management, 16 (2), 399-432.

- Gunderson, M. 1998. “Harmonization of Labour Policies under Trade Liberalization.” Relations Industrielles / Industrial Relations, 53 (1), 24-52.

- Hagerman, L.A. 2005. “Fears For the Future.” The Canadian Nurse, 101 (4), 11-12 (electronic version).

- Hart, S.E. 2005. “Hospital Ethical Climates and Registered Nurses’ Turnover Intentions.” Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 37 (2), 173-177.

- Heneman, H.G., and D.P. Schwab. 1985. “Pay Satisfaction: Its Multidimensional Nature and Measurement.” International Journal of Psychology, 20, 129-141.

- Heneman, H.G., and T.A. Judge. 2000. “Incentives and Motivation.” Compensation in Organizations: Progress and Prospects. S. Rynes and B. Gerhart, eds. San Francisco, CA: New Lexington Press, 61-103.

- Heneman, H.G., D.B. Greenberg and S. Strasser. 1988. “The Relationship between Pay for Performance Perceptions and Pay Satisfaction.” Personnel Psychology, 41, 741-761.

- Hinkin, T.R., and J.B. Tracey. 2000. “The Cost of Turnover: Putting a Price on the Learning Curve.” Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly, 41, 14-21.

- Holtom, B., T. Mitchell and T. Lee. 2008. “Turnover and Retention Research: A Glance at the Past, a Closer Review of the Present, and a Venture into the Future.” Academy of Management Annals, 291, 231-274.

- Hom, P.W., and R.W. Griffith. 1995. Employee Turnover. Cincinnati: South-Western.

- Huey, F., and S. Hartley. 1988. “What Keeps Nurses in Nursing?”American Journal of Nursing, 2, 181-188.

- Huseman, R.C., and J.D. Hatfield. 1990. “Equity Theory and the Managerial Matrix.” Training and Development Journal, 44 (4), 98-103.

- Huseman, R.C., J.D. Hatfield and E.W. Miles. 1987. “A New Perspective on Equity Theory: The Equity Sensitivity Construct.” Academy of Management Review, 12 (2), 222-234.

- Irvine, D., and M. Evans. 1995. “Job Satisfaction and Turnover among Nurses: Integrating Research Findings across Studies.” Nursing Research, 44, 246-253.

- Johnson, E.J. 2000. “The Nursing Shortage: From Warning to Watershed.” Applied Nursing Research, 13 (30), 162-163.

- Judge, T.A. 1993. “Validity of the Dimension of the Pay Satisfaction Questionnaire: Evidence of Differential Prediction.” Personnel Psychology, 46, 331-355.

- Keaveny, T., and E. Inderrieden. 2000. “Gender Differences in Pay Satisfaction and Pay Expectations.” Journal of Managerial Issues, 12 (3), 363-379.

- Kleinman, C.S. 2004. “Leadership: A Key Strategy in Staff Nurse Retention.” The Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing, 35 (3), 128-132.

- Kuttner, L. 1997. Everything for Sale: The Virtues and Limits of Markets. New York: Alfred K. Knopf and the Twentieth Century Fund.

- Laschinger, H.K.S., J. Finegan, J. Shamian and P. Wilk. 2004. “A Longitudinal Analysis of the Impact of Workplace Empowerment on Work Satisfaction.” Journal of Organizational Behavior, 25, 527-545.

- Lawler, E. 1971. Pay and Organizational Effectiveness. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Lawler, E. 1990. Strategic Pay: Aligning Organizational Strategies and Pay Systems. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Long, R. 2005. Strategic Compensation in Canada. Toronto: Nelson.

- Lum, L., J. Kervin, K. Clark, F. Reid and W. Sirola. 1998. “Explaining Nursing Turnover Intent: Job Satisfaction, Pay Satisfaction, or Organizational Commitment?” Journal of Organizational Behavior, 19, 305-320.

- Lynn, M.R., and R.W. Redman. 2005. “Faces of the Nursing Shortages: Influences on Staff Nurses’ Intentions to Leave Their Positions or Nursing.” Journal of Nursing Administration, 35 (5), 264-270.

- Miceli, M.P., and P.W. Mulvey. 2000. “Consequences of Satisfaction with Pay System: Two Field Studies.” Industrial Relations, 39, 62-87.

- Milkovich, G.T., and J.M. Newman. 2008. Compensation. 8th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Irwin.

- Mobley, W., R. Griffith, H. Hand and B. Meglino. 1979. “Review and Conceptual Analysis of the Employee Turnover Process.” Psychological Bulletin, 36 (3), 493-521.

- Motowildo, S. 1983. “Predicting Sales Turnover from Pay Satisfaction and Turnover.” Journal of Applied Psychology, 68, 484-489.

- Mottaz, C.J. 1988. “Work Satisfaction among Hospital Nurses.” Hospital and Health and Service Administration, 33 (1), 57-74.

- Mulvey, P.W., M.P. Miceli and J.P. Near. 1992. “The Pay Satisfaction Questionnaire: A Confirmatory Factor Analysis.” Journal of Social Psychology, 132, 139-141.

- Nagy, M.S. 2002. “Using a Single-Item Approach to Measure Facet Job Satisfaction.”Journal of Occupation and Organizational Psychology, 75, 77-87.

- Needleman, J., P. Buerhaus, S. Mattke, M. Stewart and K. Zelevinsky. 2002. “Nurse Staffing and Quality of Care in Hospitals in the United States.” The New England Journal of Medicine, 246 (22), 1715-1722.

- Newman, J.E. 1974. “Predicting Absenteeism and Turnover: A Field Comparison of Fishbain’s Model and Traditional Job Attitude Measures.” Journal of Applied Psychology, 59 (5), 610-615.

- North, N., E. Rasmusses, F. Hughes, M. Finlayson, T. Ashton, T. Campbell and S. Tomkins. 2005. “Turnover amongst Nurses in New Zealand’s District Health Boards: A National Survey of Nursing Turnover and Nursing Costs.” New Zealand Journal of Employment Relations, 30 (1), 49-62.

- Podsakoff, P., S. Mackenzie, J. Lee and N. Podsakoff. 2003. “Common Method Biases in Behavioural Research: A Critical Review of the Literature and the Remedies.” Journal of Applied Psychology, 85 (5), 879-903.

- Reineck, C., and A. Furino. 2005. “Nursing Career Fulfillment: Statistics and Statements from Registered Nurses.” Nursing Economics, 23 (1), 25-31.

- Renaud, S. 1998. “Unions, Wages and Total Compensation in Canada: An Empirical Analysis.” Relations Industrielles / Industrial Relations, 53 (4), 710-739.

- Rhodes, S.R., and R.M. Steers. 1981. “Conventional vs. Worker-Owned Organizations.” Human Relations, 34, 1013-1035.

- Scarpello, V., and J. Campbell. 1983. “Job Satisfaction: Are All the Parts There?” Personnel Psychology, 36 (3), 577-600.

- Scarpello, V., V. Huber and R.J. Vandenberg. 1988. “Compensation Satisfaction: Its Measurement and Dimensionality.” Journal of Applied Psychology, 73, 163-171.

- Seymour, E., and J.R. Buscherhof. 1991. “Sources and Consequences of Satisfaction and Dissatisfaction in Nursing: Findings from a National Sample.” International Nursing Studies, 28, 109-124.

- Shields, M.A., and M. Ward. 2001. “Improving Nurse Retention in the National Health Service in England: The Impact of Job Satisfaction on Intentions to Quit.” Journal of Health Economics, 20, 677-701.

- Singh, D., F. Fujita and S.D. Norton. 2004. “Determinants of Satisfaction with Pay among Nursing Home Administrators.” Journal of American Academy of Business, 5 (1/2), 230-236.

- Smith-Randolph, D. 2005. “Predicting the Effect of Extrinsic and Intrinsic Job Satisfaction Factors on Recruitment and Retention of Rehabilitation Professionals.” Journal of Health Care Management, 50 (1), 49-61.

- Spector, P. 2006. “Method Variance in Organizational Research: Truth or Urban Legend?” Organizational Research Methods, 9 (2), 221-232.

- Spetz, J., and S. Adams. 2006. “How Can Management-Based Benefits Help the Nurse Shortage?” Health Affairs, 25 (1), 212-218.

- Sturman, M.C., and S.M. Carraher. 2007. “Using a Random-Effect Model to Test Differing Conceptualizations to Multidimensional Constructs.” Organizational Research Methods, 10 (1), 108-135.

- Sweeney, P.D., and D.B. McFarlin. 1993. “Workers’ Evaluations of the ‘Ends’ and the ‘Means’: An Examination of Four Models of Distributive and Procedural Justice.” Organization Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 55, 23-40.

- Tekleab, A.G., K.M. Bartol and W. Liu. 2005. “Is it Pay Levels or Pay Raise that Matter to Fairness and Turnover?” Journal of Organizational Behaviour, 26, 899-921.

- Tremblay, M., B. Sire and D. Balkin. 2000. “The Role of Organizational Justice in Pay and Employee Benefit Satisfaction, and its Effects on Work Attitudes.” Group and Organization Management, 25 (3), 269-290.

- Upenieks, V. 2005. “Recruitment and Retention Strategies: A Management Hospital Prevention Model.” Nursing Economics, 21 (1), 7-23.

- Van Buren, H. 2008. “Fairness and the Main Management Theories of the Twentieth Century.” Journal of Business Ethics, 82, 633-644.

- Vandenberghe, C., and M. Tremblay. 2008. “The Role of Pay Satisfaction and Organizational Commitment in Turnover Intentions: A Two-Sample Study.” Journal of Business and Pschology, 22, 275-286.

- Waldman, J.D., F. Kelly, S. Arora and H.L. Smith. 2004. “The Shocking Cost of Turnover in Health Care.” Health Care Management Review, 29 (1), 2-7.

- Wanous, J., A. Reichers and M. Hudy. 1997. “Overall Job Satisfaction: How Good Are Single-Item Measures?” Journal of Applied Psychology, 82 (2), 247-252.

- Weiner, N. 1980. “Determinants and Behavioral Consequences of Pay Satisfaction: A Comparison of Two Models.” Personnel Psychology, 33, 741-758.

- Welbourne, T. 1998. “Untangling Procedural and Distributive Justice: Their Relative Effects on Gainsharing Satisfaction.” Group and Organization Management, 23 (4), 325-346.

- Williams, C. 1990. “Job Satisfaction: Comparing CC and Med/Surg Nurses.” Nursing Management. 21 (7), 104A, 104D, 104H.

- Williams, M., M.A. McDaniel and N. Nguyen. 2006. A Meta-Analysis of the Antecedents and Consequences of Pay Satisfaction.” Journal of Applied Psychology, 9, 392-413.

- Zeytinoglu, I., M. Denton, S. Davies, A. Baumann, J. Blythe and L. Boos. 2007. “Associations between Work Intensification, Stress and Job Satisfaction.” Relations Industrielles / Industrial Relations, 62 (2), 201-225.

Liste des tableaux

Table 1

Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations

Table 2

Hierarchical Regression: Turnover Intent (Dependent Variable)

10.7202/005297ar

10.7202/005297ar