Résumés

Abstract

Because of increased market uncertainty, employers today often do not guarantee job security and employees increasingly perceive such a state, often with trepidation. Employees who have relatively insecure jobs tend to feel mistreated by their managers. This study examines the relationship between the work places where jobs are mostly insecure and employee perception of abusive supervision, and the moderating role of a relational mechanism of perceived social worth at work.

The conservation of resources (COR) perspective is used to guide analysis. This perspective provides competing rationales for employee acquisition/preservation of resources and ensuing abusive supervision. In a two-wave panel survey, 271 full-time employees with various occupations completed two questionnaires. Results indicate that job insecurity is positively associated with abusive supervision. This association is stronger for employees who perceive higher social worth at work.

There is limited research investigating how managerial/leadership effectiveness varies in workplaces where job’s are insecure. Moreover, a relational mechanism of social worth has rarely been used to examine the phenomenon of job insecurity. Although literature shows employees’ perception of job insecurity leads them to increase work input/effort to make themselves more valuable and worthy of remaining in the organization, this does not mean that they will be more likely to notions such as management prerogative on their employer’s authority. Ironically, leadership, in particular, tends to be undermined when jobs are insecure as our findings show that insecure subordinates tend to perceive themselves experiencing supervisory abuse. To address this malaise, practical implications for organizations, supervisors, and subordinates are proposed and complementary practices are discussed to differentiate high social-worth employees from others.

Keywords:

- job insecurity,

- abusive supervision,

- perceived social worth,

- conservation of resources

Résumé

En raison de l’incertitude accrue des marchés, bien des employeurs actuellement ne garantissent plus la sécurité d’emploi et les employés perçoivent un tel état, souvent avec inquiétude. Les employés dont les emplois sont relativement précaires ont tendance à se sentir maltraités par leurs supérieurs. Cette étude examine la relation entre les lieux de travail où les emplois sont généralement précaires et la perception des employés concernant la supervision abusive, ainsi que le rôle modérateur du mécanisme relationnel de la valeur sociale perçue au travail.

La perspective de conservation des ressources (COR en anglais) est utilisée pour guider l’analyse. Cette perspective fournit des réponses contradictoires sur l’acquisition/préservation des ressources par les employés et la supervision abusive. Dans le cadre d’une enquête par panel à deux vagues, 271 employés à plein temps exerçant diverses professions ont rempli deux questionnaires. Les résultats indiquent que la précarité d’emploi est associée positivement à une supervision abusive. Cette association est plus forte dans le cas des employés qui perçoivent une valeur sociale plus élevée au travail.

À ce jour, peu de recherches ont été menées pour étudier dans quelle mesure l’efficacité des gestionnaires et des dirigeants varie dans les lieux de travail où les postes sont précaires. De plus, un mécanisme relationnel de valeur sociale a rarement été utilisé pour examiner le phénomène de l’insécurité de l’emploi. Bien que la littérature montre que la précarité d’emploi conduit les employés à augmenter leur travail et leurs efforts afin de se rendre plus utile et digne de demeurer dans l’entreprise, cela ne signifie pas qu’ils seront plus enclins à des notions telles que la prérogative de la direction sur l’autorité de leur employeur. Ironiquement, le leadership, en particulier, a tendance à être compromis lorsque les emplois sont instables. En effet, nos résultats montrent que les subordonnés précaires ont tendance à se percevoir en situation d’abus de supervision. Dans le but de remédier à ce malaise, des considérations pratiques pour les organisations, les superviseurs et les subordonnés sont formulées et des pratiques complémentaires sont discutées afin de différencier les employés à valeur sociale élevée des autres.

Mots-clés:

- insécurité d’emploi,

- supervision abusive,

- valeur sociale perçue,

- conservation des ressources

Resumen

Debido a la mayor incertidumbre del mercado, los empleadores de hoy en día son menos adeptos a garantizan la seguridad laboral y los empleados perciben cada vez más esta situación, a menudo con temor. Los empleados que tienen trabajos relativamente inseguros tienden a sentirse maltratados por sus gerentes. Este estudio examina la relación entre los lugares de trabajo donde los empleos son mayormente inestables y la percepción de los empleados respecto a la supervisión abusiva, y el papel moderador de un mecanismo relacional de valor social percibido en el trabajo.

Se utiliza el enfoque de la conservación de recursos (COR) para guiar el análisis. Esta enfoque proporciona argumentos competitivos para la adquisición/preservación de recursos por parte de los empleados y la consiguiente supervisión abusiva. En una encuesta de panel con dos momentos de colecta de datos, 271 empleados trabajando a tiempo completo y con ocupaciones diversas, completaron dos cuestionarios. Los resultados indican que la inestabilidad laboral se asocia positivamente con la supervisión abusiva. Esta asociación es más fuerte para los empleados que perciben un mayor valor social en el trabajo.

Existen investigaciones limitadas que estudian cómo la eficacia gerencial de liderazgo varia en los lugares de trabajo donde el trabajo es inestable. Además, rara vez se ha utilizado un mecanismo relacional de valor social para examinar el fenómeno de la inestabilidad laboral. Aunque la literatura muestra que la percepción de los empleados sobre la inestabilidad laboral los lleva a aumentar los esfuerzos del trabajo para hacerse más valiosos y dignos de permanecer en la organización, esto no significa que sean más propensos a nociones como la prerrogativa de la administración sobre la autoridad de su empleador. Irónicamente, el liderazgo, en particular, tiende a debilitarse cuando los empleos son inestables, ya que nuestros resultados muestran que los subordinados inestables tienden a percibirse a sí mismos experimentando abuso de supervisión. Para abordar este malestar, se propone implicaciones prácticas para las organizaciones, supervisores y subordinados y se discuten prácticas complementarias para diferenciar a los empleados de alto valor social de los demás.

Palabras claves:

- inestabilidad laboral,

- supervisión abusiva,

- valor social percibido,

- conservación de recursos

Corps de l’article

Introduction

A major airline company in Europe planned to restructure and downsize in October 2015 because of intensifying market competition. Stressed by the awareness that their jobs had become insecure, the employees of the company claimed to have felt mistreated by their employer (Malm, 2015). In November 2015, the employees of a Taiwanese semiconductor company feared that their jobs would be less secure if their employing company was later acquired. They worried that they would be subject to abusive supervision by the acquiring company, which denied that this would be the case (Liberty Times Net, 2015). Notably, these phenomena in both Western and Eastern countries are the analytic fodder for job insecurity literature, which has widely shown that job insecurity is in essence a matter of employee perception (e.g., Schumacher et al., 2016; Teng et al., 2019; Van Hootegem et al., 2019). Hence, this study’s research question is: “How does employee perception of job insecurity relate to negative labor-management relations, conceptualized as employee perception of abusive supervision (Klaussner, 2014)?”

Because of rapidly changing technology and ensuing economic change over the last two decades, today, employers often do not guarantee job security (Wang, Lu and Siu, 2015; Coupe, 2019). Hence, as employers increase their flexibility for performance (e.g., De Cuyper et al., 2012; Schumacher et al., 2016), employees perceive an overall work context of increased job insecurity (i.e., the risk of job loss, see Guo et al., 2019; Coupe, 2019). This perception of job insecurity is prevalent in today’s workplaces (Chirumbolo 2015; Guo et al., 2019) and has become a mainstream characteristic of employees’ working life (Sverke, Hellgren and Näswall, 2006; Coupe, 2019), and an issue that they are concerned about (Bassanini et al., 2013; Schumacher et al., 2016). There is literature on employment relations and work organization that has been devoted to understanding employees in the work context of job insecurity, which has sought to better understand what employees do to retain their jobs and the associated issues of negative employee emotions, stress at work, resistance to change, turnover intention, and deterioration in employee work attitudes and behaviours (e.g., Chirumbolo, 2015; König et al., 2011; Schumacher et al., 2016; Teng et al., 2019; Van Hootegem et al., 2019).

The literature concerning job insecurity and employee perception of abusive supervision mostly focuses on the effect of the job-insecurity context on employees’ reactions to their jobs and organizations, and largely overlooks employees’ reactions to their supervisors. This is a gap that the present study aims to fill by focusing on employees’ reactions to perceived abusive supervision. Such a contribution is important because, although essentially an industrial relations-type concern (Klaussner, 2014), abusive supervision also influences managerial effectiveness and organizational performance (Tepper, 2007; Wang et al., 2015). In this latter sense, most employees dislike job insecurity (Coupe, 2019; Schumacher et al., 2016). Understanding the effect of job insecurity on abusive supervision would be beneficial for employers. They can better understand how their supervising style is influenced by job insecurity and influences employees’ perceptions of job insecurity. In addition, this study focuses on a negative element of the employment relationship as perceived by employees. Because people are more responsive to negatively perceived contexts than they are to positively perceived ones, negative contexts influence people more than positive ones (Baumeister et al., 2001).

Abusive supervision is defined as “subordinates’ perceptions of the extent to which supervisors engage in the sustained display of hostile verbal and nonverbal behaviors, excluding physical contact” (Tepper, 2000: 178). Notably, abusive supervision is a subjective assessment (Harvey et al., 2014), and the behaviours of a supervisor may be evaluated differently by different subordinates. Abusive supervision is a well-documented, common and problematic workplace phenomenon (Mackey et al., 2017); its consequences on employees and organizations have been well investigated (e.g., Kernan, Racicot and Fisher, 2016; Mackey et al., 2017; Xu, Zhang and Chan, 2019), but its antecedents have received limited research attention. The literature which does exist mostly focuses on the roles played by individual factors and work contexts as reported by supervisors (Mawritz, Folger and Latham, 2014; Zhang and Bednall, 2016) and subordinates (Klaussner, 2014). The second contribution of this study is that it examines the work context of employees reporting a perception of job insecurity, which is noteworthy because abusive supervision is measured by subordinates’ reporting. Further, this study provides a different theoretical lens, conservation of resources theory that differs from the lens of contexts reported by supervisors, i.e., the perspectives of injustice and psychological contract violations (e.g., Kernan et al., 2016; Klaussner, 2014; Mackey et al., 2017; Zhang and Bednall, 2016). As job insecurity refers to employees’ loss of resources at work (De Witte, 1999) and supervisors can be a source of both resource gain and loss (Harvey et al., 2014), the two perspectives mentioned above ignore the possibility that employees’ perceptions of abusive supervision can be reactions to their experience of resource loss at work. The third contribution of this study is that it presents a complementary perspective of the role of resources, for which the conservation of resources (COR) theory is particularly relevant (Hobfoll, 1989).

As indicated by Sverke et al. (2006: 20), the moderation of the effects of job insecurity deserves additional attention because, even if the moderators may not change an insecure employment situation into a more favourable one, they all may have beneficial effects for the individual and the organization if they weaken the negative reactions. A costly outcome of job insecurity is that the most qualified and valuable employees (those most worthy of remaining in the organization) typically leave first (Murphy et al., 2013: 515). Thus, worthy employees’ who perceive job insecurity is a critical consideration for managers who seek to prevent the negative consequences of such perceptions on the part of employees. The fourth contribution of this study is to understand whether the effect and perception of job insecurity on abusive supervision is moderated by employee perceptions of their worth at work, which is conceptualized as perceived social worth, as indicated by the degree to which employees’ actions are valued/appreciated in the workplace (Grant, 2008) and, as stated later, is sometimes viewed as a resource gain of employees. Considering that there is possibly such a moderating role of perceived social worth at work (Grant, 2008), job insecurity research should explore such mechanisms to learn how the detrimental consequences of job insecurity can be reduced (Richter, 2011).

Theory and Hypotheses Development

This study examines how job insecurity within the workplace relates to abusive supervision. Job insecurity, in this study, refers to employee perception of an overall work context of job insecurity in the organization. This subjective view of job insecurity is embodied in job insecurity literature, which indicates that employees in the same work situation or environment may perceive different levels of job insecurity (e.g., De Cuyper et al., 2012; König et al., 2011; Van Hootegem et al., 2019) due to subjective elements rather than the characteristics of the situation per se (Lazarus and Folkman, 1984).

We introduce the theoretical perspective of COR (Hobfoll, 1989, 2002) in the following to understand how job insecurity relates to abusive supervision. As job insecurity is a major job stressor (e.g., Callea et al., 2017; König et al., 2011) and COR is a theoretical lens that has been frequently discussed in the literature on stress (Ng and Feldman, 2012), we propose that COR will be useful for understanding how abusive supervision is influenced by job insecurity.

COR theory proposes that an individual’s resources are those that are either valued in their own right by the individual or serve as a means to attain or protect other valued resources. COR theory emphasizes that: 1- resources include symbolic value in addition to instrumental value; 2- both perceived and actual losses of resources can be harmful (Brotheridge and Lee, 2002); and 3- resource loss—either anticipated or realized—can accumulate. The theory suggests that people have limited resources (including time, physical and emotional energy, and attention); strive to gather, protect, and retain those resources; take care not to unduly deplete them; and make an effort to acquire additional resources (Ng and Feldman, 2012). That is, COR theory consists of both a ‘resource conservation’ tenet and a ‘resource acquisition’ tenet (Ng and Feldman, 2012: 219). The ‘resource conservation’ tenet asserts that, as a consequence of resource loss, people will become more cautious in consuming their remaining resources, take care not to deplete their resources too deeply in order to protect them, and avoid situations that will lead to resource loss. Namely, people focus on resource conservation by defending their existing resources and tend not to invest in the creation of additional resources. However, the ‘resource acquisition’ tenet of COR theory asserts that, because resource loss creates a negative psychological state, people will work hard, invest their resources and engage in behaviours to generate/accumulate new/additional resources to offset any future losses (Ng and Feldman, 2012).

These two tenets of COR theory provide different theoretical perspectives about the relationship of job insecurity to abusive supervision and each makes antithetical predictions. Dunnette (1966), Anseel and Lievens (2007) and Ng and Feldman (2012) note that, as researchers have no a priori expectation about which theory would be supported, they state competing hypotheses. The approach of considering alternative hypotheses provides richer information that can be productively integrated into theory (Rousseau, 1995: 160), avoids narrowness in research and increases the odds of finding some interpretable effects (Twenty, Doherty and Mynatt, 1981). Hence, we propose competing hypotheses of a negative and positive relationship between job insecurity and abusive supervision as follows.

Job insecurity is the potential threat of job loss (Probst, 2000) and thereby presents a risk that employees will be deprived of their important needs that work fulfills, such as income, social contacts, identity, status, time structure, the ability to develop individually and socially, and/or predictability in the near future (De Witte, 1999). These are employees’ resources because they are either valued in their own right by the individual or serve as a means to attain or protect other valued resources. That is, job insecurity has been understood from a resource-based perspective (De Cuyper et al., 2012) and refers to the loss of important (financial, psychological, social, and societal) resources (De Witte, 1999: 159).

Hence, according to the ‘resource acquisition’ tenet of the COR theory, insecure employees will engage in resource-investment behaviours, as has been shown in the literature on job insecurity. For example, employees threatened by job insecurity increase their inputs into the organization (Wong et al., 2005; Yi and Wang, 2015). They may work harder, be absent less often (Staufenbiel and König, 2010) and participate more in opportunities for learning, workplace friendships and work effort (Mao and Hsieh, 2013; Wong et al., 2005). These behaviours improve employees’ performance/productivity (Wong et al., 2005) and require an investment of physical (e.g., time and presence), emotional (e.g., relationship maintenance/enhancement), and cognitive (e.g., vigilant attention, more/deeper communication, and feedback receiving and giving (Kahn, 1990)) resources. These resource-investment behaviours allow insecure employees to acquire and accumulate additional resources by, for example, managing impressions in self-serving ways, accruing value at work, increasing their worth to the organization, and garnering status/respect (Staufenbiel and König, 2010; Wong et al., 2005) to keep their jobs or at least reduce job insecurity. In other words, for supervisors, the resource-investment behaviours of insecure employees lead to increased usefulness, i.e., higher utility; the literature has evidenced that subordinates who provide higher utility to their supervisors will experience less supervisory abuse (Tepper, Moss and Duffy, 2011).

For employees, attention influences the interpretation of ambiguous information (White et al., 2011) and employees with more job insecurity pay more attention to increasing their resource acquisition and accumulation to earn higher performance appraisals from supervisors and thus mitigate job insecurity. As a result, increased job insecurity may lead employees to increasingly interpret supervisors’ critical, negative feedback (which conforms to Tepper’s operationalization of abuse) as an indication of a way to engage in improvement/development rather than consider that they are victims of abusive supervision.

In short, the resource acquisition tenet of COR theory suggests that job insecurity induces employees’ resource investment-acquisition-accumulation to protect against future job loss. Those actions, in turn, will increase the employees’ utility for supervisors and cause the employees to interpret supervisors’ behaviours as indicators of how they can improve. Hence, we propose:

Hypothesis 1a: Job insecurity is negatively associated with employee ratings of abusive supervision.

In contrast, the ‘resource conservation’ tenet of the COR theory (Ng and Feldman, 2012) asserts that, as a consequence of resource loss, people will focus on resource conservation, defend their existing resources, avoid resource depletion and tend not to invest in the creation of additional resources. Job insecurity, as noted earlier, refers to the loss of important resources (De Witte, 1999: 159). In line with the consequences of resource loss, the findings of previous research suggest that insecure employees will reduce their consumption of resources that require physical (e.g., time, presence), emotional (e.g., relationship maintenance/enhancement) and cognitive (e.g., attention, communication, trust and confidence) energy. This reduction in consumption includes, for example, decreased communication, trust, and confidence among employees (Doherty, 1996); decreased job involvement, organizational commitment and loyalty (e.g., Cheng and Chan, 2008); increased workplace individualism, demoralization and suspicion (Doherty, 1996); and increased disengagement and distance from the job and the organization (Cheng and Chan, 2008; Yi and Wang, 2015). In short, insecure employees will engage in resource conservation, exhibit a consequent reduction in consumption and become disengaged from the job and the organization. To supervisors, these behaviours will render insecure employees less useful, i.e., diminish their utility. Some literature indicates that subordinates with less utility for supervisors will experience more supervisory abuse (Tepper et al., 2011).

Conversely, insecure employees’ reduction in consumption compels such employees to perceive their job situation in a negative way, which we propose leads to a negative perception of supervisors for three reasons. First, supervisors can be the organizational embodiment (Eisenberger et al., 2014) and are manifestations of their organizations (Harvey et al., 2014) because employees receive organizational demands, resources, rewards and discipline primarily through their supervisors, who have a duty to achieve organizational goals. Second, supervisors are often considered to be legitimate representatives of organizations (Ogunfowora, 2013), which reinforces their surrogate role. Finally, attribution theory indicates that adjusted people tend to attribute success to internal elements and failure (i.e., loss) to external elements (Forgas, Bower and Moylan, 1990). Thus, employees may attribute the threat of job loss and the ensuing resource loss to the external factor of their supervisors because supervisors play an important role in assessing their performance, their value at work and whether the employer views them as worthy of being retained. As such, supervisors become a natural target for blame when employees perceive job insecurity in the organization.

In summary, the ‘resource conservation’ tenet of COR theory suggests that job insecurity will promote negative perceptions of supervisors; that is, subordinates view supervisors’ behaviours through an increasingly negative lens. For example, more insecure subordinates may perceive their supervisors’ behaviours, such as diminished communication, objective critical feedback, and discipline enforcement, to be silent treatment, inaccurate negative feedback, inappropriate blame, a lack of credit for accomplishments, or the displacement of supervisors’ anger or negative feelings. That is, insecure employees may view legitimate managerial behaviours as abuse; thus, job insecurity increases employees’ perceptions of abusive supervision. Additionally, when insecure subordinates use a more negative lens to view supervisors’ behaviours, they may pay selective attention to supervisors and selectively remember the negative aspects and behaviours of supervisors because having a negative attitude towards a thing will direct attention to the negative qualities of that thing (Fazio and Towles-Schwen, 1999). Altogether, more insecure subordinates may report more supervisor abuse on subjective, perceptual measures of this abuse (Tepper, 2000: 190).

The arguments proposed above focus on employee perception of abusive supervision because this has been mostly measured in previous research (Mackey et al., 2017; Tepper, 2007). It is likely that employees who perceive job insecurity in an organization experience actual abusive behaviours. Specifically, job insecurity can deplete employees’ resources, causing them to offer little resistance to negative treatment (De Cuyper et al., 2009), thus decreasing their ability to defend themselves. Additionally, a higher perception of job insecurity leads to the belief that there is a higher risk of job loss (Bassanini et al., 2013). This belief causes employees to become more worried about being disciplined and terminated by supervisors, and subordinates have relatively low levels of retaliatory power (Tepper et al., 2006). Hence, job insecurity decreases employees’ willingness to defend themselves. Victim precipitation theory indicates that those who are hesitant (i.e., unable or unwilling) to defend themselves are more likely to draw the attention of aggressive individuals (Tepper et al., 2006). Therefore, insecure employees are more likely to become the targets of supervisory abuse.

In short, insecure employees will experience more abusive supervision, both perceptually and objectively. We propose the following:

Hypothesis 1b: Job insecurity is positively associated with employee ratings of abusive supervision.

This study proposes that perceived social worth at work is a job resource that moderates the job insecurity-abusive supervision relationship. According to COR theory, job resources refer to physical, social, or organizational job aspects that have three functions: achieving work goals, providing protection from threats and the associated psychological costs, or encouraging personal development (Xanthopoulou et al., 2009: 184). Because these three functions are facilitated by the ability to control and be influential, the objects or conditions referring to individuals’ sense of their ability to maintain control over their actions and influence their environment are resources at work (De Cuyper et al., 2012). Perceived social worth is the degree to which employees perceive that their actions at work are appreciated and valued by other workers (Baumeister and Leary, 1995). Because perceived social worth relates to employees’ own actions at work, those actions are under their control. The appreciation and value of others that employees perceive suggest that the employees’ actions have an impact on others. As such, employees’ perceived social worth inculcates a sense of control over their work and an impact on their environment and thus is a job resource for employees.

COR theory (Hobfoll, 1989) asserts that those with more resources are less vulnerable to resource loss and that a gain in resources will help offset a loss. Thus, being a resource gain, perceived social worth contributes to a greater affordability of resource losses and a decrease in resource losses from job insecurity. Accordingly, for Hypothesis 1a, which proposes that increased resource investment by insecure employees leads to reduced abusive supervision, those who perceive higher social worth can more afford resource losses and perceive less losses from job insecurity; thus, their resource investment will be less, and abusive supervision will be less reduced. That is, perceived social worth attenuates the negative relationship of job insecurity with abusive supervision. For Hypothesis 1b, which proposes that increased resource conservation by insecure employees leads to increased abusive supervision, those with higher social worth can more afford resource losses and perceive less losses from job insecurity; thus, they will be less inclined to engage in resource conservation and abusive supervision will be less increased. That is, perceived social worth attenuates the positive relationship of job insecurity with abusive supervision. Accordingly, we propose the following:

Hypothesis 2: The relationship between job insecurity and abusive supervision will be weaker for employees who perceive high social worth than for those who perceive low social worth.

Method

Sample and Data Collection

A two-wave panel survey over a four-week period was conducted to collect the data for this study. Self-reports were necessary because, as specified earlier, the concepts, job insecurity and abusive supervision, are perceptual measures that are, by definition, self-reported (Wong, DeSanctics and Staudenmayer, 2007). Additionally, the control variables indicated below are perceptual measures. The survey was piloted using 30 full-time employees attending evening classes at a university in Taiwan to examine whether it contained inappropriate or unclear items. In response to the opinions of respondents in the pilot, where necessary, items were reworded.

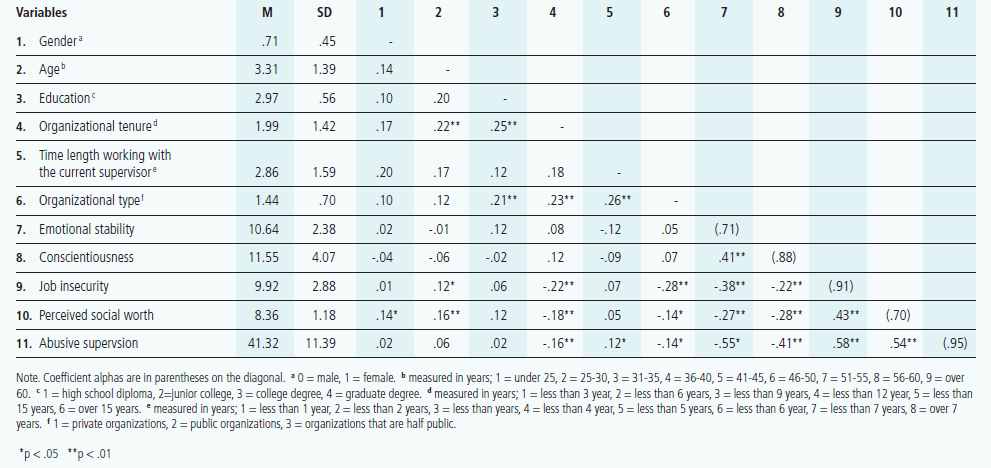

As indicated by Podsakoff et al. (2003), introducing a time lag between the measurement of the predictor and criterion variables creates a temporal separation to control the common method bias. Therefore, a two-wave panel survey design was used in order to be less subject to the common method bias caused by self-reported measures. Questionnaires were distributed to 550 full-time employees working in a variety of occupations in Taiwan who were recruited through their employers or through full-time employees attending evening classes at a university in Taiwan. To increase their willingness to participate, respondents received a gift upon completing the second questionnaire. A total of 417 employees completed both questionnaires, and 271 employees provided comprehensive responses, yielding a final response rate of 49.3%. Of the completed surveys, sixty-five percent (95 questionnaires) missed data on the outcome measure, i.e., abusive supervision, among other missing data, and twenty-seven percent (39 questionnaires) missed data on the categorical variables (gender, age, education, organizational tenure, time length with current supervisor, and organization type). Deleting cases listwise with missing data on the outcome measure was used as a way of handling missing data (Schlomer, Bauman and Card, 2010: 2). This technique is preferable to many others for handling questionnaires with incomplete answers (Allison, 2001). A profile of the 271 participants in the sample is shown in Table 1.

Table 1

Characteristics of the Sample

Note. a 0 = male, 1 = female. b measured in years; 1 = under 25, 2 = 25-30, 3 = 31-35, 4 = 36-40, 5 = 41-45, 6 = 46-50, 7 = 51-55, 8 = 56-60, 9 = over 60. c 1 = high school diploma, 2 = junior college, 3 = college degree, 4 = graduate degree. d measured in years; 1 = less than 3 year, 2 = less than 6 years, 3 = less than 9 years. 4 =less than 12 year, 5 = less than 15 years, 6 = over 15 years. e measured in years; 1 = less than 1 year, 2 = less than 2 years, 3 = less than 3 years. 4 = less than 4 year, 5 = less than 5 years, 6 = less than 6 year, 7 = less than 7 years, 8 = over 7 years. f organizations are 1 = privately owned and not part of the government, 2 = owned and operated by the government, or 3 = not owned by the government but the government is their biggest shareholder.

Time 1 Measures

In the first phase of the survey, the respondents completed the items measuring independent, moderating and control variables. The responses for all items were scored on a five-point Likert scale that ranged from “(1) strongly disagree” to “(5) strongly agree”. Higher total scores indicated higher degrees of the variables measured.

Job insecurity. As noted earlier, job insecurity in this study refers to an employee’s perception of an overall work context of insecurity for jobs in his/her organization and, thus, a scale of cognitive job insecurity was used (Staufenbiel and König, 2011). The three items of the scale are: “Overall, employees’ jobs are secure in my working organization”, “Generally speaking, employees can keep their jobs in the near future in my working organization”, and “Overall, employees will be employed for a long time in my present workplace” (all items were reverse-scored; Staufenbiel and König, 2011) (Mean = 9.92, SD = 2.88, alpha = .91). Our wording, intended to lead respondents to consider their organizations’ context of job insecurity, is consistent with the wording in previous studies, which measured the human resource management practice of job security in work organizations (e.g., Barrick et al., 2015). All factor loadings (ranging from .86 to .89) of the three items exceeded the threshold value of .50.

Perceived social worth. A two-item scale was used to measure the perceived social worth of respondents (Grant, 2008): “I feel that others appreciate my work” and “I feel that other people value my contributions at work” (Mean = 8.36, SD = 1.18, alpha = .70). The factor loadings of the two items (.72 and .74, respectively) exceeded the threshold value of .50.

Control variables. Because prior studies have found that employees’ emotional stability and their conscientiousness will influence their perception of abusive supervision (Henle and Gross, 2014; Mackey et al., 2017), both concepts were included as control variables. Each was measured using five items from the International Personality Item Pool (Goldberg et al., 2006). Sample items of emotional stability were, “I am relaxed most of the time” and “I am not easily bothered by things.” All the emotional stability items except one had the factor loadings higher than the threshold value of .50 (ranging from .56 to .66). One item had the factor loading below 0.50 and thus was removed from the emotional stability scale, resulting in a four-item scale (Mean = 10.64, SD = 2.38, alpha = .71). Sample items of conscientiousness were, “I do things by the book” and “I pay attention to details.” All factor loadings (ranging from .68 to .87) of the five items of conscientiousness exceeded the threshold value of .50 (Mean = 11.55, SD = 4.07, alpha = .88).

Other control variables included respondents’ gender, age, education, organizational tenure, and length of time working with their current supervisor because these variables have been found to influence employee perception of abusive supervision (e.g., Henle and Gross, 2014; Mackey et al., 2017; Zhang and Bednall, 2016). Moreover, respondents were asked to indicate their organizational type, namely: 1- privately-owned and not part of the government; 2- owned and operated by the government; or 3- not owned by the government, but the government is their largest shareholder. The data regarding organizational types were collected because in Taiwan it is common knowledge (e.g., Cheers, 2011) that public organizations do not lay off employees unless employees break the law or make serious errors. The same is true, to a lesser degree, in Taiwanese organizations that are not owned by the government but whose largest shareholder is the government (e.g., ETtoday.net, 2015). In other words, organizational type may confound the effect of job insecurity; thus, it was included as a control variable in this study.

Time 2 Measures

Time 2 occurred four weeks after time 1. In the second wave of the survey, the respondents completed the items measuring their perception of abusive supervision. The responses for all items were scored on a five-point Likert scale that ranged from “(1) strongly disagree” to “(5) strongly agree”. Higher total scores indicated a stronger perception of abusive supervision. A 15-item scale developed by Tepper (2000) was used to measure employee perception of abusive supervision (Mean = 41.32, SD = 11.39, alpha = .95). Sample items were “My supervisor gives me the silent treatment” and “My supervisor reminds me of my past mistakes and failures.” All factor loadings (ranging from .54 to .82) of the 15 items exceeded the threshold value of .50.

Data Analyses

In addition to the two-wave panel survey design, procedural and statistical techniques were used to control for common method biases (Podsakoff et al., 2003). In our procedure, we guaranteed respondents anonymity and confidentiality to decrease the biases of social desirability and leniency. During our statistical analyses, the possibility of common method bias was tested using Harman’s one-factor test (Podsakoff and Organ, 1986). A principal component factor analysis of the items measured yielded five factors with eigenvalues greater than 1.0 and accounted for 65.9% of the variance. Five factors, rather than one factor, were identified, and the first factor did not account for a large percentage of the variance (28.1%). Thus, common method bias did not appear to be a serious threat to the findings of this study. Additionally, using AMOS, we completed a confirmatory factor analysis to test the fit of a one-factor model (all items were loaded on a common factor) and a five-factor model (job insecurity, abusive supervision, perceived social worth, emotional stability, and conscientiousness). The data showed that the five-factor model had a better fit (X2 =729.97, df =367, X2/df =1.99, GFI =.84, NNFI =.92, CFI =.93, RMSEA =.06 [CI =.054, .067], RMR =.04) than the one-factor model (X2 =1711.28, df =377, X2/df =4.54, GFI =.67, NNFI =.70, CFI =.72, RMSEA =.11 [CI = .109, .120], RMR =.09), indicating a low probability of common method variance .

Further, we used unmeasured latent method construct (ULMC, see Williams, Cote and Buckley, 1989) to test for the influence of common method variance. First, we tested our measurement model including the five variables as five factors (job insecurity, abusive supervision, perceived social worth, emotional stability, and conscientiousness; Correlation 1 original ~ Correlation 10 original, C1O~C10O). The second measurement model included one unmeasured common method factor in the hypothesized measurement model to examine whether the effect of unmeasured common method factor is present (Correlation 1 Parcel ~ Correlation 10 Parcel, C1P~C10P). The result is that the addition of one unmeasured common method factor into the hypothesized measurement model did not significantly improve model fit (CMIN =13.82, p >.05, i.e., we cannot reject that C1O~C10O-C1P~C10P). Hence, we concluded that common method variance was not a significant influence on our findings.

As indicated above, the factor loadings for all items exceeded the threshold value of .50. The composite reliabilities for the scales of job insecurity, abusive supervision, perceived social worth, emotional stability and conscientiousness were .91, .95, .70, .71, and .88, respectively, and all composite reliabilities exceeded the threshold value of .60 (Fornell, 1982). The average variance extracted for the scales of job insecurity, abusive supervision, perceived social worth, emotional stability and conscientiousness were .77, .56, .54, .38, and .60, respectively. The average variances extracted for all constructs except one exceeded the benchmark of 0.50. Fornell (1982) and Chin (1998) have indicated that average variance extracted above 0.36 is acceptable. Thus, all the average variances extracted were acceptable. Altogether, the scales used in measuring those constructs were deemed to have satisfactory convergence reliability. The squared correlations among constructs (ranging from .05 to .34) were less than the variances extracted by the constructs (ranging from .38 to .77). This showed that the constructs were empirically distinct (Fornell, 1982). Thus, the convergent and discriminant validity measures were satisfactory.

To determine the unique contribution of job insecurity, beyond that of the control variables, to the prediction of abusive supervision, hierarchical regression analyses were performed. Specifically, the control variables were put into the equation first, followed by job insecurity, to examine the effect of job insecurity on abusive supervision. In a subsequent analysis, the control variables were put into the equation first, followed by the predictor variable, the moderator and the interaction term of the predictor variable and moderator, to examine whether the moderation hypothesis proposed was empirically supported. Given that the demographic variables (gender, age, and education) were not significantly related to the outcome variable, abusive supervision (see Table 2), we removed these control variables from the analyses to reduce the estimation bias and benefit the interpretation of the results (Becker et al., 2016). The hierarchical regression analyses without those control variables included were presented and used to examine the proposed hypotheses.

Table 2

Means, Standard Deviations and Correlations

Note. Coefficient alphas are in parentheses on the diagonal. a 0 = male, 1 = female. b measured in years; 1 = under 25, 2 = 25-30, 3 = 31-35, 4 = 36-40, 5 = 41-45, 6 = 46-50, 7 = 51-55, 8 = 56-60, 9 = over 60. c 1 = high school diploma, 2=junior college, 3 = college degree, 4 = graduate degree. d measured in years; 1 = less than 3 year, 2 = less than 6 years, 3 = less than 9 years, 4 = less than 12 year, 5 = less than 15 years, 6 = over 15 years. e measured in years; 1 = less than 1 year, 2 = less than 2 years, 3 = less than years, 4 = less than 4 year, 5 = less than 5 years, 6 = less than 6 year, 7 = less than 7 years, 8 = over 7 years. f 1 = private organizations, 2 = public organizations, 3 = organizations that are half public.

*p < .05 **p < .01

Results

Table 2 presents the means, standard deviations, and correlations for this study. It shows that job insecurity was related to older age, shorter organizational tenure, working in private organizations, less emotional stability and conscientiousness, more perceived social worth and abusive supervision. Abusive supervision was related to shorter organizational tenure, a longer time with the current supervisor, working in private organizations, less emotional stability and conscientiousness, higher job insecurity and perceived social worth. This finding is consistent with previous findings that less emotional stability and conscientiousness relate to abusive supervision (Henle and Gross, 2014).

In Table 3, Model 2, which used a hierarchical regression, shows that the addition of job insecurity accounted for a significant amount of variance (increment of adjusted R2: .12, F(9, 261)= 42.26, p <.01; F change(1, 261)= 65.05, p <.01) beyond that attributable to the effect of control variables. The regression coefficient for job insecurity was .41 (p <.01), indicating that job insecurity positively predicted abusive supervision. This result supported Hypothesis 1b, which predicted a positive relationship between job insecurity and abusive supervision, and did not support Hypothesis 1a, which predicted a negative relationship.

Table 3

Results of Hierarchical Regression Analysis for Abusive Supervision

As shown in Table 3, Model 3, which used a hierarchical regression, shows that the addition of perceived social worth accounted for a significant amount of variance (increment of adjusted R2: .07, F(10, 260)= 47.99, p <.01; F change (1, 260)= 41.15, p <.01) beyond that attributable to the effects of control variables and job insecurity. In Table 3, Model 4, which used a hierarchical regression, shows that adding the interaction term of job insecurity and perceived social worth accounted for a significant amount of variance (increment of adjusted R2: .01, F (11, 259)= 42.94, p <.01; F change (1, 259)= 3.90, p <.05) beyond that attributable to the effects of control variables, job insecurity, and perceived social worth. The results indicated a statistically significant interaction (the regression coefficient: β= .60, p <.05) between job insecurity and perceived social worth in predicting abusive supervision. To examine this interaction, we performed a simple slopes test and used the Aiken and West (1991) approach where we examined the moderator at values ± 1 standard deviation from the mean. Simple slopes tests suggest that the relationship between job insecurity and abusive supervision is positive and statistically significant at high levels of perceived social worth at work (+1 SD; effect=1.45, t=6.14, se=.236, 95%CI [.983, 1.911]) and statistically significant at lower levels of perceived social worth at work (-1 SD; effect=.914, t=3.80, se=.24, 95%CI [.44, 1.387]). Using this approach, we see a stronger relationship between job insecurity and abusive supervision for employees who perceive higher social worth at work (please see Figure 1). However, Hypothesis 2 predicted that this relationship would be attenuated for employees who perceived higher social worth at work. Thus, the moderating effect of perceived social worth that was empirically supported showed a pattern that was antithetical to that postulated in Hypothesis 2. Therefore, the data failed to support Hypothesis 2.

Figure 1

Job Insecurity and Perceived Social Worth on Abusive Supervision

Discussion

The results indicate that job insecurity increased employee perception of abusive supervision, an unambiguously negative element of the employment relationship (Klaussner, 2014), and that the effect was stronger for those who perceived higher social worth at work. Our findings have several different kinds of theoretical implications. First, it appears that abusive supervision is more prevalent in work contexts characterized by job insecurity for employees with higher social worth at work.

Our results support Hypothesis 1b and thus provide evidence for COR theory: resource loss in the form of perceived job insecurity leads to resource loss in the form of perceived abusive treatment from supervisors (as positive treatment from supervisors is a job resource; Dubois et al., 2014). With regard to the consequence of job insecurity, the ‘resource conservation’ tenet of the COR theory is empirically supported in this study. However, contrary to the prediction of Hypothesis 2, the positive relationship of job insecurity to abusive supervision is stronger for employees who perceive higher social worth at work. A possible rationale for this unexpected finding is that gaining more resources at work, employees with higher perceived social worth should be of more value to the employer. However, the employer also treats this cohort of employees to job insecurity. These employees could consider this insecurity to be undeserved or inconsistent with their value to the organization and would feel some degree of cognitive dissonance. To reduce this dissonance, they are more likely to react in a more negative way and blame their supervisors, who personify the employer (Eisenberger et al., 2014). Thus, these employees would perceive their supervisors more negatively and report higher levels of abusive supervision.

Our findings suggest that a caveat should accompany the assertion of COR theory, that those with more resources are less vulnerable to resource loss and that a gain in resources will help offset a loss. Specifically, perceived social worth at work is a job resource for employees because it allows for a sense of control over their work and for them to impact their environment, as stated earlier. Accordingly, employees’ perceived social worth is a resource that is generated by the employees themselves, and, in contrast, the resource loss induced by job insecurity is a resource that is generated by the organization (e.g., income, social contacts, identity, status, time structure, and/or predictability in the near future). The finding regarding Hypothesis 2 suggests that employees’ with more resources generated by themselves neither made them less vulnerable to, nor offset the loss of resources generated by, the organization. In other words, a suggested complement to COR theory is as follows: individuals with more resources that are generated by a particular source are less vulnerable to the loss of the resources generated by that source, and a gain in resources generated by a source will help offset a loss of the resources generated by that source. According to this suggested complement, we propose the managerial implication that will be explained below. Future research is needed on this caveat to gain a deeper understanding of the tenets of COR theory (Hobfoll, 1989).

While the perspectives of injustice (e.g., Klaussner, 2014; Mackey et al., 2017) and psychological contract violation (e.g., Kernan et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2016) have been much used as theoretical frameworks to explain abusive supervision, this study expands these by considering the perspective of resources and COR theory. However, the three perspectives are not as distinct as they appear. Specifically, COR theory posits that an object or condition that can assist employees in achieving work goals, reducing job demands, or stimulating personal growth and development is a job resource (Hobfoll, 1989) and both perceived and actual resource loss can be harmful (Brotheridge and Lee, 2002). Both the justice and psychological contract that employees perceive at work will facilitate job performance (McDermott et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2014); thus, both assist employees in achieving work goals and are job resources. Accordingly, perceived injustice and psychological contract violation at work are losses of justice and psychological contract resources, respectively, and both losses can be harmful. In other words, the resource perspective can underlie the injustice and psychological contract violation perspectives and will thus be more parsimonious for understanding abusive supervision.

Our results failed to support Hypothesis 1a, which predicted a negative relationship between job insecurity and abusive supervision. However, this does not exclude the possibility that job insecurity among some employees or in some cases may trigger actions in the form of resource acquisition, as per the prediction of COR theory, thus leading to a lower perception of abusive supervision. For example, job insecurity more likely evokes resource investment in the creation of additional resources to offset a potential job loss: 1- for employees who are sure that the additional resources reduce job insecurity; 2- in organizations that accentuate firm-specific resources (knowledge/skills); or 3- in countries with a more liberal approach to employment protection regulation. To date, these seem not yet to be the case among the employees in this study.

A second key contribution of this study is that its findings inform and extend the research stream on job insecurity. The literature on job insecurity has focused little on employee attitudes towards and perception of leaders, with more work called for to understand the implications of job insecurity for individuals and organizations (Schumacher et al., 2016; Sverke et al., 2006). Because abusive supervision eventually deteriorates individual and organizational performance (e.g., Tepper, 2007; Wang et al., 2015), the findings of this study are important for managerial interventions that assist employees in managing their ongoing perception of job insecurity and that assist supervisors in preventing their style of workforce management, and ensuing supervisory effort/interaction from being undermined by a prevailing work context of job insecurity, a major job stressor (e.g., Callea et al., 2017) in today’s organizations.

Limitations and Future Directions

The limitations of this study should be noted. While abusive supervision is influenced by job insecurity, it might itself influence job insecurity. As specified below, such influence will not be an issue in this study. First, a two-wave panel survey design was conducted, as indicated previously. Second, the present study focuses on the overall work context subjectively perceived by insecure employees for jobs in their organizations and uses a scale for subjective job insecurity (Staufenbiel and König, 2011) that uses terms to help the respondents consider the overall organizational context. Our wording, which was intended to lead respondents to consider their organizations’ context in reflecting on job insecurity, is consistent with the wording used in previous studies that measured the human resource management practice of job security in work organizations (e.g., Barrick et al., 2015). The work context of job insecurity is a concept that is related to organizational aspects, while abusive supervision is a micro-level concept, because it focuses on the interactions of a few individuals (see Neuman, 2011: 71, i.e., an employee’s perception of his/her supervisor’s behaviours). It is inherent that organizational concepts act as stimuli and micro-level concepts act as responses, and research tests the effects of stimuli on responses (Rosenberg, 1968: 13). Accordingly, this study examines the effect of the work context of job insecurity on employee perception of abusive supervision.

With the acceptable response rate, no attempt was made to establish the representativeness of the sample, and the data collected did not permit a direct test of the underlying rationale for job insecurity. A more explicit examination is needed in future studies. Additionally, this study was conducted only in Taiwan and it is likely that future studies using samples from other countries or cultures would provide a more robust test of the hypotheses as cultural differences affect employee perception at work (Lu and Lin, 2014; Wu and Xu, 2012). Taiwanese tend to have Chinese cultural values (Mao and Hsieh, 2013). These values have a strong authority orientation and are more likely to embody authoritarianism (Wu and Xu, 2012), which may lead employees to more easily accept supervisors’ behaviour and to have fewer negative perceptions of supervisors. This would weaken the relationship between job insecurity and abusive supervision. That is, the Taiwanese context may decrease, rather than increase, effect sizes. It is thus unlikely that cultural influences in Taiwan compromised the validity of the results.

Managerial Implications

Organizations employ job insecurity to heighten productivity, flexibility and resultant performance (e.g., De Cuyper et al., 2012; Teng et al., 2019; Van Hootegem et al., 2019); however, a dilemma for these organizations is that job insecurity enhances employee perception of abusive supervision, a negative labour-management relationship (Klaussner, 2014), which is disadvantageous to supervisors/managers, who embody their organization (Eisenberger et al., 2014). Furthermore, it is this insecurity that eventually undermines organizational performance (Tepper, 2007; Wang et al., 2015). It is hereby suggested that organizations should cultivate an organizational climate that makes all members (i.e., employees and managers/supervisors) not only aware of the aims of job insecurity and its importance for the organization, but also makes them aware that supervisors are to achieve organizational aims, including increased job insecurity, which may cause some discomfort for employees. Supervisors need to be conscious of the dilemma stated above and should have sensitivity and leadership training to adjust/improve supervisory behaviours, which may include, for example, supervisors reminding subordinates about their responsibility to achieve/implement organizational aims/practices, making clear the aims of their behaviours at work and encouraging subordinates in ambiguous situations to ask for help to avoid misunderstandings. For subordinates, they should focus on resource investment in performance (i.e., engaging in behaviours to accumulate additional resources for performance) rather than resource conservation (i.e., defending existing resources and engaging in a reduction in resource consumption) to diminish the perception of abusive supervision.

Considering that job insecurity is adopted to enhance performance and that those employees with higher perceived social worth tend to have more resources, as stated earlier, and higher performance (Grant, 2008) and should thus be more valuable to supervisors and the organization, our findings reveal another dilemma in that such employees will have higher perceptions of abusive supervision. According to the complement to COR theory proposed earlier—that those with more resources generated by a source are less vulnerable to resource loss from that source and that a gain in resources from a source will help offset a resource loss from that source—we propose that job insecurity induces the resource loss brought about by the organization and that this loss will be more affordable and offset by the resource gain from the organization. Therefore, we propose that an organization with increased job insecurity, i.e., a declining human resource management practice relating to job security (e.g., Barrick et al., 2015), can use complementary practices, such as formal, organizational incentive programs and informal, non-financial incentive programs (e.g., giving more recognition/appraisal, offering more assistance, and/or showing more care/concern) by supervisors to differentiate high social-worth employees from others. For high social-worth employees, gaining resources from these complementary practices can offset the resource losses induced by job insecurity because both types of resources are brought about by the organization; thus, these employees can attenuate the abusive supervision they experience. This approach may help address the trade-off that appears to exist between gaining the benefit of job insecurity and undermining worthy employees’ perceptions of their supervisors.

Parties annexes

References

- Aiken, Leona S. and Stephen G. West (1991) Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

- Allison, Paul D. (2001) “Missing Data.” In Michael S. Lewis-Beck (Ed.) Sage University Papers Series on Quantitative Applications in the Social Sciences. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, p. 7-136.

- Anseel, Frederik and Filip Lievens (2007) “The Relationship between Uncertainty and Desire for Feedback: A Test of Competing Hypotheses.” Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 37, 1007-1040.

- Barrick, Murray R., Gary R. Thurgood, Troy A. Smith and Stephen H. Courtright (2015) “Collective Organizational Engagement: Linking Motivational Antecedents, Strategic Implementation, and Firm Performance.” Academy of Management Journal, 58, 111-135.

- Bassanini, Andrea, Thomas Breda, Eve Caroli and Antoine Rebérioux (2013) “Working in Family Firms: Less Paid but More Secure? Evidence from French Matched Employer-Employee Data.” ILR Review, 66, 433-466.

- Baumeister, Roy, Ellen Bratslavsky, Catrin Finkenauer and Kathleen D. Vohs (2001) “Bad Is Stronger than Good.” Review of General Psychology, 5, 323-370.

- Baumeister, Roy and Mark Leary (1995) “The Need to Belong: Desire for Interpersonal Attachments as a Fundamental Human Motivation.” Psychological Bulletin, 117, 497-529.

- Becker, Thomas E., Guclu Atinc, James A. Breaugh, Kevin D. Carlson, Jeffrey R. Edwards and Paul E. Spector (2016) “Statistical Control in Correlational Studies: 10 Essential Recommendations for Organizational Researchers.” Journal of Organizational Behavior, 37, 157-167.

- Brotheridge, Céleste M. and Raymond Lee (2002) “Testing a Conservation of Resources Model of the Dynamics of Emotional Labor.” Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 7, 57-67.

- Callea, Antonino, Alessandro Lo Presti, Saija Mauno and Flavio Urbini (2017) “The Associations of Quantitative/ Qualitative Job Insecurity and Well-Being: The Role of Self-Esteem.” International Journal of Stress Management. Advance online publication: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/str0000091.

- Cheers (2011) Struggling for a Job in the Government? Retrieved from: http://www.cw.com.tw/article/article.action?id=5005281, (April 28th, 2011).

- Cheng, Grand and Darius K. S. Chan (2008) “Who Suffers More from Job Insecurity? A Meta-Analytic Review.” Applied Psychology, 57, 272-303.

- Chin, Wynne W. (1998) “Commentary: Issues and Opinion on Structural Equation Modeling.” MIS Quarterly, 22, 7-16.

- Chirumbolo, Antonio (2015) “The Impact of Job Insecurity on Counterproductive Work Behaviors: The Moderating Role of Honesty-Humility Personality Trait.” The Journal of Psychology, 149, 554-569.

- Coupe, Tom (2019) “Automation, Job Characteristics and Job Insecurity.”International Journal of Manpower.“ 40, 1288-1304.

- De Cuyper, Nele, Elfi Baillien and Hans De Witte (2009) “Job Insecurity and Workplace Bullying among Targets and Perpetrators: Moderation by Employability.” Work and Stress, 23, 206-224.

- De Cuyper, Nele, Anne Makikangas, Ulla Kinnunen, Saija Mauno and Hans De Witte (2012) “Cross-lagged Associations between Perceived External Employability, Job Insecurity, and Exhaustion: Testing Gain and Loss Spirals according to the Conservation of Resources Theory.” Journal of Organizational Behavior, 33, 770-788.

- De Witte, Hans (1999) “Job Insecurity and Psychological Well-Being: Review of the Literature and Exploration of some Unresolved Issues.” European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 8, 155-177.

- Doherty, Noellen (1996) “Surviving in an Era of Insecurity.” European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 5, 471-478.

- Dubois, Carl-Ardy, Kathleen Bentein, Jamal Ben Mansour, Frederic Gilbert and Jean-Luc Bédard (2014) “Why some Employees Adopt or Resist Reorganization of Work Practices in Health Care: Associations between Perceived Loss of Resources, Burnout, and Attitudes to Change.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 11, 187-201.

- Dunnette, Marvin (1966) “Fads, Fashions, and Folderol in Psychology.” American Psychologist, 21, 343-352.

- Eisenberger, Robert, Mindy Krischer Shoss, Gökhan Karagonlar, Gloria Gonzalez-Morales, Robert E. Wickham and Louis C. Buffardi (2014) “The Supervisor POS–LMX–Subordinate POS Chain: Moderation by Reciprocation Wariness and Supervisor’s Organizational Embodiment.” Journal of Organizational Behavior, 35, 635-656.

- ETtoday.net (2015) Forty Thousands Took the Entrance Examination for 2000 Vacancies in Post Office (A Partly Public Organization). Retrieved from: http://www.ettoday.net/news/20151102/588727.htm#ixzz3vQ2P9ejZ, (October 30, 2015).

- Fazio, Russell H. and Tamara Towles-Schwen (1999) “The MODE Model of Attitude-Behavior Processes.” In Shelly Chaiken and Yaacov Trope (Eds.) Dual Process Theories in Social Psychology. New York: Guilford, p. 97-116.

- Fornell, Claes (1982) A Second Generation of Multivariate Analysis: Methods, vols. I and II. New York: Praeger.

- Forgas, Joseph P., Gordon H. Bower and Stephanie J. Moylan (1990) “Praise or Blame? Affective Influences on Attributions for Achievement.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59, 809-819.

- Goldberg, Lewis R., John Jonson, Herbert W. Eber, Robert Hogan, Michael C. Ashton, C. Robert Cloninger and Harrison G. Gough (2006) “The International Personality Item Pool and the Future of Public-Domain Personality Measure.” Journal of Research in Personality, 40, 84-96.

- Grant, Adam M. (2008) “The Significance of Task Significance: Job Performance Effects, Relational Mechanisms, and Boundary Conditions.” Journal of Applied Psychology, 93, 108-124.

- Guo, Ming, Shuzhen Liu, Fulei Chu, Long Ye and Qichao Zhang (2019) “Supervisory and Coworker Support for Safety: Buffers between Job Insecurity and Safety Performance of High-Speed Railway Drivers in China.” Safety Science, 117, 290-298.

- Harvey, Paul, Kenneth J. Harris, William E. Gillis and Mark J. Martinko (2014) “Abusive Supervision and the Entitled Employee.” The Leadership Quarterly, 25, 204-217.

- Henle, Christine A. and Michael A. Gross (2014) “What Have I Done to Deserve This? Effects of Employee Personality and Emotion on Abusive Supervision.” Journal of Business Ethics, 122, 461-474.

- Hobfoll, Stevan E. (1989) “Conservation of Resources: A New Attempt at Conceptualizing Stress.” American Psychologist, 44, 513-524.

- Hobfoll, Stevan E. (2002) “Social and Psychological Resources and Adaptation.” Review of General Psychology, 6, 307-324.

- Kahn, William A. (1990) “Psychological Conditions of Personal Engagement and Disengagement at Work.” Academy of Management Journal, 33, 692-724.

- Kernan, Mary C.; Bernadette M. Racicot and Allan M. Fisher (2016) “Effect of Abusive Supervision, Psychological Climate, and Felt Violation on Work Outcomes.” Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies, 23, 309-321.

- Klaussner, Stefan (2014) “Engulfed in the Abyss: The Emergence of Abusive Supervision as an Escalating Process of Supervisor-Subordinate Interaction.” Human Relations, 67, 311-332.

- König, Cornelius J., Tahira M. Probst, Sarah Staffen and Maja Graso (2011) “A Swiss-US Comparison of the Correlates of Job Insecurity.” Applied Psychology: An International Review, 60, 141-159.

- Lazarus, Richard S. and Susan Folkman (1984) Stress, Appraisal and Coping, New York: Springer.

- Liberty Times Net (2015) “Protesting Acquisition by ASC, Three Thousand Employees of SPIL Held a Demonstration.” Retrieved from: http://news.ltn.com.tw/news/business/paper/932499, (November 15th, 2015).

- Lu, Chin-Shan and Chi-Chang Lin (2014) “The Effects of Perceived Culture Difference and Transformational Leadership on Job Performance in the Container Shipping Industry.” Journal of Marine Science and Technology, 22, 463-475.

- Mackey, Jeremy D., Rachel E. Frieder, Jeremy R. Brees and Mark J. Martinko (2017) “Abusive Supervision: A Meta-Analysis and Empirical Review.” Journal of Management, 43, 1940-1965.

- Malm, Sara (2015) “No Need to Get Shirty! Air France Executive is Forced to Climb a Fence After Staff Attack Him and Rip off His Shirt When He Announces 2,900 Job Losses.” Daily Mail News.com, October 5th. Retrieved from: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-3260474/Air-France-managers-flee-staff-storm-meeting-job-cuts.html, (August 12th, 2017).

- Mao, Hsiao-Yen and An-Tien Hsieh (2013) “Perceived Job Insecurity and Workplace Friendship.” European Journal of International Management, 7, 646-670.

- Mawritz, Mary B., Robert Folger and Gary P. Latham (2014) “Supervisors’ Exceedingly Difficult Goals and Abusive Supervision: The Mediating Effects of Hindrance Stress, Anger, and Anxiety.” Journal of Organizational Behavior, 35, 358-372.

- McDermott, Aoife M., Edel Conway, Denise M. Rousseau and Patrick C. Flood (2013) “Promoting Effective Psychological Contracts through Leadership: The Missing Link between HR Strategy and Performance.” Human Resource Management, 52, 289-310.

- Murphy, Wendy Marcinkus, James P. Burton, Stephanie C. Henagan and Jon P. Briscoe (2013) “Employee Reactions to Job Insecurity in a Declining Economy: A Longitudinal Study of the Mediating Role of Job Embeddedness.” Group and Organization Management, 38, 512-537.

- Neuman, W. Lawrence (2011) Social Research Methods: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches. 7th ed. Boston, MA: Pearson.

- Ng, Thomas S. W. and Daniel C. Feldman (2012) “Employee Voice Behavior: A Meta-Analytic Test of the Conservation of Resources Framework.” Journal of Organizational Behavior, 33, 216-234.

- Ogunfowora, Babatunde (2013) “When the Abuse is Unevenly Distributed: The Effects of Abusive Supervision Variability on Work Attitudes and Behaviors.” Journal of Organizational Behavior, 34, 1105-1123.

- Podsakoff, Philip M., Scott. B. MacKenzie, Jeong-Yeon Lee and Nathan P. Podsakoff (2003) “Common Method Biases in Behavioral Research: A Critical Review of the Literature and Recommended Remedies.” Journal of Applied Psychology, 88, 879-903.

- Podsakoff, Philip M. and Dennis W. Organ (1986) “Self-Report Problems in Organizational Research: Problems and Prospects.” Journal of Management, 12, 531-544.

- Probst, Tahira Michelle (2000) “Wedded to the Job: Moderating Effects of Job Involvement on the Consequences of Job Insecurity.” Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 5, 63-73.

- Richter, Anne (2011) Job Insecurity and its Consequences: Investigating Moderators, Mediators and Gender. Stockholm, Sweden: Stockholm University.

- Rosenberg, Morris (1968) The Logic of Survey Analysis. New York: Basic Books.

- Rousseau, Denise M. (1995) “Publishing from a Reviewer’s Perspective.” In L. L. Cummings and Peter J. Frost (Eds.), Publishing in the Organizational Sciences. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, p. 51-163.

- SAS Resource Center (2018) Web Page. Retrieved from: http://www.sasresource.com/faq80.html, (August 11th, 2018).

- Schlomer, Gabriel L., Sheri Bauman and Noel A. Card (2010) “Best Practices for Missing Data Management in Counseling Psychology.” Journal of Counseling Psychology, 57, 1-10.

- Schumacher, Désirée, Bert Schreurs, Hetty Van Emmerik and Hans De Witte (2016) “Explaining the Relation between Job Insecurity and Employee Outcomes during Organizational Change: A Multiple Group Comparison.” Human Resource Management, 55, 809-827.

- Staufenbiel, Thomas and Cornelius J. König (2010) “A Model for the Effects of Job Insecurity on Performance, Turnover Intention, and Absenteeism.” Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 83, 101-117.

- Staufenbiel, Thomas and Cornelius J. König (2011) “An Evaluation of Borg’s Cognitive and Affective Job Insecurity Scales.” International Journal of Business and Social Science, 2, 1-7.

- Sverke, Magnus, Johnny Hellgren and Katharina Näswall (2006). Job Insecurity: A Literature Review, SALTSA report. ISSN 1404-8485; 2006:1 Stockholm: Arbetslivsinstitutet och SALTSA.

- Teng, Eryue, Li Zhang, Yang Qiu and Adrian Wilkinson (2019) “Always Bad for Creativity? An Affect-Based Model of Job Insecurity and the Moderating Effects of Giving Support and Receiving Support.” Economic and Industrial Democracy, 40, 803-829.

- Tepper, Bennett J. (2000) “Consequences of Abusive Supervision.” Academy of Management Journal, 43, 178-190.

- Tepper, Bennett J. (2007) “Abusive Supervision in Work Organizations: Review, Synthesis, and Research Agenda.” Journal of Management, 33, 261-289.

- Tepper, Bennett J., Michelle K. Duffy, Chris A. Henle and Lisa S. Lambert (2006) “Procedural Injustice, Victim Precipitation, and Abusive Supervision.” Personnel Psychology, 59, 101-123.

- Tepper, Bennett J., Sherry E. Moss and Michelle K. Duffy (2011) “Predictors of Abusive Supervision: Supervisor Perceptions of Deep-Level Dissimilarity, Relationship Conflict, and Subordinate.” Academy of Management Journal, 54, 279-294.

- Twenty, Ryan D., Michael E. Doherty and Clliford R. Mynatt (1981) On Scientific Thinking, Columbia University Press: New York.

- Van Hootegem, Anahi, Hans De Witte, Nele De Cuyper and Tinne Vander Elst (2019) “Job Insecurity and the Willingness to Undertake Training: The Moderating Role of Perceived Employability.” Journal of Career Development, 46, 395-409.

- Wang, Hai-Jiang, Chang-Qin Lu and Oi-ling Siu (2015) “Job Insecurity and Job Performance: The Moderating Role of Organizational Justice and the Mediating Role of Work Engagement.” Journal of Applied Psychology, 100, 1249-1258.

- White, Lauren K., Jenna G. Suway, Daniel S. Pine, Yair Bar-Haim and Nathan A. Fox (2011) “Cascading Effects: The Influence of Attention Bias to Threat on the Interpretation of Ambiguous Information.” Behaviour Research and Therapy, 49, 244-251.

- Williams, Larry J., Joseph A. Cote and M. Ronald Buckley (1989) “Lack of Method Variance in Self-Reported Affect and Perceptions at Work: Reality or Artifact?” Journal of Applied Psychology, 74, 462-468.

- Wong, Sze-Sze, Gerardine DeSanctics and Nancy Staudenmayer (2007) “The Relationship between Task Interdependency and Role Stress: A Revisit of the Job Demands-Control Model.” Journal of Management Studies, 44, 284-303.

- Wong, Yui-Tim, Chi-Sum Wong, Hang-Yue Ngo and Hon-Kwong Lui (2005) “Different Responses to Job Insecurity of Chinese Workers in Joint Ventures and Stated-Owned Enterprises.” Human Relations, 58, 1391-1418.

- Wu, Min and Erica Xu (2012) “Paternalistic Leadership: From Here to Where?” In H. Xu and M. H. Bond (Eds.), The Handbook of Chinese Organizational Behavior: Integrating Theory, Research, and Practice. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing, p. 449-466.

- Xanthopoulou, Dr Despoina, Arnold B. Bakker, Evangelia Demerouti and Wilmar B. Schaufeli (2009) “Work Engagement and Financial Returns: A Diary Study on the Role of Job and Personal Resources.” Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 82, 183-200.

- Xu, Qin, Guangxi Zhang and Andrew Chan (2019) “Abusive Supervision and Subordinate Proactive Behavior: Joint Moderating Roles of Organizational Identification and Positive Affectivity.” Journal of Business Ethics, 157, 829-843.

- Yi, Xiang and Shu Wang (2015) “Revisiting the Curvilinear Relation between Job Insecurity and Work Withdrawal: The Moderating Role of Achievement Orientation and Risk Aversion.” Human Resource Management, 54, 499-515.

- Zhang, Yucheng and Timothy C. Bednall (2016) “Antecedents of Abusive Supervision: A Meta-Analytic Review.” Journal of Business Ethics, 139, 455-471.

- Zhang, Yiwen, Jeffery A. LePine, Brooke R. Buckman and F. Wei (2014) “It’s Not Fair… or Is It? The Role of Justice and Leadership in Explaining Work Stressor-Job Performance Relationships.” Academy of Management Journal, 57, 675-697.

Liste des figures

Figure 1

Job Insecurity and Perceived Social Worth on Abusive Supervision

Liste des tableaux

Table 1

Characteristics of the Sample

Note. a 0 = male, 1 = female. b measured in years; 1 = under 25, 2 = 25-30, 3 = 31-35, 4 = 36-40, 5 = 41-45, 6 = 46-50, 7 = 51-55, 8 = 56-60, 9 = over 60. c 1 = high school diploma, 2 = junior college, 3 = college degree, 4 = graduate degree. d measured in years; 1 = less than 3 year, 2 = less than 6 years, 3 = less than 9 years. 4 =less than 12 year, 5 = less than 15 years, 6 = over 15 years. e measured in years; 1 = less than 1 year, 2 = less than 2 years, 3 = less than 3 years. 4 = less than 4 year, 5 = less than 5 years, 6 = less than 6 year, 7 = less than 7 years, 8 = over 7 years. f organizations are 1 = privately owned and not part of the government, 2 = owned and operated by the government, or 3 = not owned by the government but the government is their biggest shareholder.

Table 2

Means, Standard Deviations and Correlations

Note. Coefficient alphas are in parentheses on the diagonal. a 0 = male, 1 = female. b measured in years; 1 = under 25, 2 = 25-30, 3 = 31-35, 4 = 36-40, 5 = 41-45, 6 = 46-50, 7 = 51-55, 8 = 56-60, 9 = over 60. c 1 = high school diploma, 2=junior college, 3 = college degree, 4 = graduate degree. d measured in years; 1 = less than 3 year, 2 = less than 6 years, 3 = less than 9 years, 4 = less than 12 year, 5 = less than 15 years, 6 = over 15 years. e measured in years; 1 = less than 1 year, 2 = less than 2 years, 3 = less than years, 4 = less than 4 year, 5 = less than 5 years, 6 = less than 6 year, 7 = less than 7 years, 8 = over 7 years. f 1 = private organizations, 2 = public organizations, 3 = organizations that are half public.

*p < .05 **p < .01

Table 3

Results of Hierarchical Regression Analysis for Abusive Supervision