Résumés

Summary

The development of work–life policies—e.g., employee assistance programs, on-site childcare, flextime, part-time, compressed week, and so on—is increasingly important for a growing number of organizations. Though such programs provide benefits for both employees and employers, usage rates are still low. Scholars have called for research that addresses this phenomenon and more particularly explains the underlying processes of individual decision-making concerning work–life balance, and describe why and how certain social groups differ in their approaches to policy use. Our inductive study –based on 44 individual interviews- aims to address these issues. We found that the policies are used differently depending on the employees’ social group, and that certain salient social identities—such as gender, parenthood and managerial status—shape their use. Such programs are a structural and cultural change for organizations and often present an opportunity for redefining the centrality of work. Indeed the values inherent in them, including resting and taking time for oneself or for one’s family, may conflict with the traditionally masculine values associated with the ‘ideal worker’, intuitively linked to performance and production of positive results. The clash between the two, which permeated the interviews, causes employees to fall back on the social identity or identities they find meaningful. Our findings show three main strategies that individuals use when they feel that their social identity is threatened: (1) engage in workaround activities to avoid using work-life policies; (2) try to compensate for policies use (by engaging in projects outside one’s job or doing overtime work) ; and (3) significantly limit policies use. These results contribute to literature by showing that many managers and men do not feel legitimate to use work-life policies and find workarounds to manage without them, thus perpetuating stereotypical masculine norms. We demonstrate that the identity threat that underlies work-life policies taking may help women in the short term, but also contributes to their discrimination in the long run as well as is detrimental to the work-life balance of men.

Key-words:

- work-life policies,

- gender,

- social identity,

- policy use

Résumé

Le déploiement des politiques de conciliation vie professionnelle- vie personnelle (programmes d'aide aux salariés, crèches, horaires flexibles, temps partiel, semaine compressée, etc.) est de plus en plus important pour de nombreuses organisations. Bien que ces dispositifs offrent des avantages tant aux salariés qu'aux employeurs, leur taux d'utilisation reste faible. Les chercheurs ont appelé à plus de travaux pour expliquer ce phénomène, notamment les processus sous-jacents de la prise de décision individuelle concernant l'équilibre vie professionnelle- vie personnelle, et décrire pourquoi et comment certains groupes sociaux diffèrent dans leurs approches de l'utilisation de ces dispositifs. Notre étude inductive - basée sur 44 entretiens individuels - vise à répondre à ces questions. Nous avons constaté que les politiques de conciliation sont utilisées différemment selon le groupe social des salariés, et que certaines identités sociales saillantes - comme le genre, la parentalité et le statut de manager - influencent leur usage. En effet, ces dispositifs représentent un changement structurel et culturel pour les organisations et offrent souvent l'occasion de redéfinir la centralité du travail. Les valeurs inhérentes à ces politiques, notamment le fait visible de prendre du temps pour soi ou pour sa famille, peuvent entrer en conflit avec les valeurs traditionnellement masculines associées au "travailleur idéal", intuitivement liées à la performance, la disponibilité et la production de résultats positifs. Le conflit entre les deux, qui a imprégné les entretiens, amène les salariés à se replier sur l'identité ou les identités sociales qu'ils trouvent significatives pour eux. Nos résultats montrent trois stratégies principales que les individus utilisent lorsqu'ils sentent que leur identité sociale est menacée : (1) ils s'engagent dans des activités de contournement pour éviter d'utiliser les politiques de conciliation travail-vie privée ; (2) ils essaient de compenser l'utilisation des politiques, en s’engageant dans des projets professionnels hors-travail ou en effectuant des heures supplémentaires ; et (3) ils limitent significativement l'utilisation des politiques. Ces résultats contribuent à la littérature en montrant que beaucoup de managers et de nombreux hommes ne se sentent pas légitimes d’utiliser ces politiques, et trouvent des stratégies de contournement pour éviter de les utiliser, perpétuant ainsi les normes masculines au travail. Nous démontrons également que la menace identitaire qui sous-tend l'adoption des politiques de conciliation peut aider les femmes à court terme, mais contribue également à les freiner dans leur carrière à long terme et nuit à l'équilibre vie professionnelle-vie personnelle des hommes.

Précis

Le déploiement des politiques de conciliation vie professionnelle- vie personnelle (programmes d'aide aux employés, crèches, horaires flexibles, temps partiel, semaine compressée, etc.) est de plus en plus important pour de nombreuses organisations. Bien que ces dispositifs offrent des avantages tant aux employés qu'aux employeurs, leur taux d'utilisation reste faible. Les chercheurs ont appelé à plus de recherche pour expliquer ce phénomène, notamment les processus sous-jacents de la prise de décision individuelle concernant l'équilibre vie professionnelle- vie personnelle, et décrire pourquoi et comment certains groupes sociaux diffèrent dans leurs approches de l'utilisation de ces dispositifs. Notre étude inductive - basée sur 44 entretiens individuels - vise à répondre à ces questions. Nous avons constaté que les identités sociales telles que le genre, la parentalité et le statut de manager déclenchent des perceptions de légitimité différentes qui, à leur tour, façonnent l'utilisation des politiques de conciliation. Ces résultats contribuent à la littérature en montrant que de nombreux managers et hommes ne se sentent pas légitimes d’utiliser ces politiques, et trouvent des solutions de contournement pour éviter de les utiliser, perpétuant ainsi les normes masculines au travail. Nous démontrons que la menace identitaire qui sous-tend l'adoption des politiques de conciliation peut aider les femmes à court terme, mais contribue également à leur discrimination à long terme et nuit à l'équilibre vie professionnelle-vie personnelle des hommes.

Mots-clefs:

- conciliation vie professionnelle- vie personnelle,

- genre,

- identité sociale,

- usage

Corps de l’article

Introduction

A growing number of organizations have been devoting resources to the development of work–life policies, e.g., employee assistance programs, on-site childcare, flextime, part-time, compressed week, and so on —to support their employees’ multiple life roles (Kossek, Lewis, and Hammer, 2010). Such policies enable organizations to adapt to changing work–life needs and have been associated with positive outcomes: better job performance (Gajendran and Harrison, 2007); increased well-being at work (Kossek et al., 2011; Moen et al., 2016); higher earnings (Gariety and Shaffer, 2001; Weeden, 2005); and talent attraction and retention (Beauregard and Henry, 2009). Despite the benefits, work-life policies still have a surprisingly low rate of use (Williams, Blair-Loy and Berdhal, 2013; Bourdeau, Ollier-Malaterre, and Houlfort, 2019).

The existing literature on work-life policies provides some insights into their advantages (e.g., Beauregard and Henry, 2009; Moen et al., 2016) and disadvantages (e.g., Brescoll, Glass, and Sedlovskaya, 2013; Coltrane et al. 2013; Leslie et al., 2012; Wharton, Chivers, and Blair-Loy, 2008). Reasons for under-use, however, still lack empirical evidence. There have been calls for an explanation of the underlying processes of individual decision-making on work–life balance (Powell et al., 2019) and for studies that describe why and how certain social groups differ in their approaches to policy use (Perrigino et al., 2018).

We wish to address that gap in the literature by asking why employees do not use the work–life policies offered by their organizations. To this end, we have studied two organizations known for their innovative work-life programs, specifically by asking 44 individuals how they perceive and use them. Using an inductive research strategy (Gioia, Corely, and Hamilton, 2012), we have teased out the connections that interlink salient social identities, perceived policies legitimacy and actual policies use. We have found that policies use is especially affected by social identities, such as gender, parenthood and managerial status.

Our research contributes to the literature on work-life balance (WLB) in three ways. First, we provide a framework that indicates how social identities trigger perceptions of legitimacy, which in turn shape policies use. Our findings provide empirical evidence to support hypotheses that employees—especially men and managers—refrain from program use because they fear backlash (Perrigino et al., 2018) and stigmatization (Williams, Blair-Loy, and Berdahl, 2013). Second, our model explains how current policies use perpetuates pre-existing stereotypical norms, thus furthering inequality in career advancement for women and contributing to overburdened work lives for men. Third, we detail three identity-protecting strategies that managers and male employees use to avoid unnecessary stigmatization due to policies use.

The work–life policies puzzle

The existing literature (e.g., Brescoll, Glass, and Sedlovskaya, 2013; Perrigino et al., 2018; Williams, Blair-Loy, and Berdahl, 2013) offers possible reasons for the disconnect between increasing availability of work-life programs and their low rate of use. Employees might not want to use them out of concern that their careers might suffer (Brescoll, Glass, and Sedlovskaya, 2013). Such fears are well-founded, as there is evidence that employees who take leave or use flexible work practices experience slower wage growth (Coltrane et al. 2013), earn fewer promotions, have poorer performance evaluations (Leslie et al., 2012; Wharton, Chivers, and Blair-Loy, 2008) and are perceived as being less motivated and less dedicated to work (Rogier and Padgett 2004). These outcomes create work–family backlash, a “phenomenon reflecting the negative attitudes, behaviors, and emotions associated with the ability and use of work-life balance policies” (Perrigino et al., 2018: 606). The norms that discourage policies use (Minnotte and Minnotte, 2021), and create backlash and stigmatization, stem from specific social identities. We therefore draw on social identity theory (Tajfel and Turner, 1985) to examine the links between identities, norms and actual policies use.

Social identity and ideal norms

Social identity theory offers insights into how individuals adapt work–life management to social norms (Foucreault et al., 2018). Its premise is that people will categorize themselves and others into social groups that define their self-concept in intergroup situations (Ashforth and Mael, 1989; Hornsey, 2008; Tajfel and Turner, 1985). In salient social groups, one will thus identify ideal group members, i.e., ‘prototypes’ who act as group paragons, and adjust one’s own attitudes and behaviours in order to become more like them (Hornsey, 2008). One will likewise learn to surmount the tensions that arise when working for an employer whose expectations differ from one’s social identity (Reid, 2015). Such circumstances may threaten values, meanings or behaviours associated with one’s social identity, thereby triggering a need for identity protection (Petriglieri, 2011; Chen and Reay, 2020).

The ‘Ideal Worker’ Norm

As the prototypical group member in work organizations, the ‘ideal worker’ may influence employees’ attitudes and behaviours. The ‘ideal worker’ is highly committed (Williams, 2000) and consistently available for work (Acker, 1990). This norm promotes a “work devotion schema” (Blair-Loy, 2003; 2004) that focuses on making work the central or sole focus in an individual’s life, without the distractions of family interference. It is still the dominant and expected norm in most organizations, regardless of the changes that a workplace may have gone through (Reid, 2015). It creates difficulties (Coltrane et al., 2013; Rudman and Mescher, 2013; Williams et al., 2013; Tanquerel and Grau-Grau, 2020), especially for those who struggle to embrace its inherent expectations (Stone, 2007; Humberd et al., 2015).

Work-life policies challenge social identities that are built to the ‘ideal worker’ norm (Tanquerel and Grau-Grau, 2020). Resistance may develop when this new norm comes into conflict with the work devotion schema and gendered identities, such as masculinity and motherhood (Williams et al., 2016). Managers tend to favour employees who use flexibility policies to increase productivity rather than to accommodate family responsibilities (Leslie, Park, Mehng, and Manchester, 2012). Those who do use flexibility programs for more ‘caring’ reasons risk stigmatization and marginalization (Coltrane et al., 2013; Rudman and Mescher, 2013; Williams et al., 2013). Such factors tend to compel individuals to find alternative strategies to maintain an expected identity (Tanquerel and Grau-Grau, 2020).

Implications of the ‘Ideal Worker’ Norm for Women

The ‘ideal worker’ is a gendered norm based on outdated male work patterns (Minnotte and Minnotte, 2021). So long as their non-work lives had been taken care of by women, men were seen as ‘ideal workers’ by employers because of their availability and unencumbered status as employees (Dumas and Sanchez-Burks, 2015). Today, women pay a higher price for violating the ‘ideal worker’ norm (Kmec et al., 2014) because they are still expected to do the housework and look after the needs of family members (Ladge and Little, 2019). Hence, it is particularly difficult for them to become ‘ideal workers,’ as this role would clash with the role of the traditional ‘good mother.’ The contemporary ‘good mother’ is expected to compromise on her own needs for the sake of her family and prioritize family over career goals (Kvande, Brandth, and Halrynjo, 2017).

Implications of the ‘Ideal Worker’ Norm for managers

The ‘ideal worker’ norm is equally meaningful to managers. It may vary by social class and by occupation (Neely, 2020). Elite professional identities, for example, demand extreme devotion to work (Williams, 2000). Managers and elite employees might display their extreme work schedules to show how important they are (Williams, 2000). We suggest that redefining work or work–life balance will affect managers and non-managers in different ways with respect to social norms. This may partially explain differences in use of work-life policies; however, little research has focused on how managers as a social group use them.

Overall, the existing literature (Williams et al., 2016; Tanquerel and Grau-Grau, 2020; Minnotte and Minnotte, 2021) mostly indicates that the ‘ideal worker’ norm remains an obstacle to work–life initiatives. Nevertheless, there is still much to be learned about how individuals make decisions that impact their work–life balance (Powell et al., 2019). Study of identities may help (Williams et al., 2016), particularly by improving comprehension of policies use (Perrigino et al., 2018). Additionally, with better understanding of the underlying processes of policies use, employers may be better able to address under-use and thereby increase their employees’ well-being and eliminate workplace inequity.

1. Methodology

1.1 Research setting

To study the surprising mismatch (Edmondson and McManus, 2007) between the increasing supply of work-life policies and the stagnant demand for them, we used an approach uniquely suited to ‘why’ and ‘how’ questions: qualitative research (Doz, 2011). We began with a small shipping subsidiary known for its strong work–life policies and local initiatives for promoting innovative work–family balance programs. Its 25 employees include mail carriers, administrative and sales personnel and managers. It has received the national government’s Professional Equality label, which certifies the employer’s expressed responsibility for and interest in endorsing work–life balance. It is also a founding member of a major European work–life balance network. Its policies include financial aid, housing assistance, support for ill or disabled children, flexible start and finish times, compressed workweeks, part-time opportunities, sabbaticals, parental leave and special arrangements to accommodate sporting, cultural and banking activities. To portray a wider view of the issues in this research, we supplemented our study with a second organization that has similar work–life policies. It, too, has received certification for being a family-oriented company. As a subsidiary of a large tractor and farm equipment company, it has sales and marketing personnel, accounting assistants and managers among its employees.

By choosing different types of organizations that benefit from elaborate work-life policies, we were able to explore a variety of individual perceptions behind policies use. Our sample included men and women, managers and non-managers, and blue-collar and white-collar workers in two economic sectors in southern Europe. By covering multiple levels of organizational hierarchy, and sector and gender diversity, we ensured that our analysis did not inadvertently embrace or prioritize the values of a given social or gendered class. It was also our intention to broaden the scope of perceptions of WLB beyond North America and address the call for more diverse field studies (Williams et al., 2016).

Figure 1

Interviewee Characteristics

1.2 Data Collection and Analysis

The data were collected and analyzed in three stages. The first author visited the first organization (two days per week for a period of three months), often accompanying workers on their deliveries. The informal discussions and observations provided a deep understanding of the context and the methods for informing people about work-life policies, as well as reactions to them. Following Gioia, Corely, and Hamilton (2012), the first author used open-ended questions to cover three main topics: the interviewees’ perception of the centrality of work in their lives; how they perceived work–life policies in general; and the motivations for and the decision-making behind policies use. The interviewees were asked to explain the company’s work-life policies and share their thoughts on them, with the interviews generally lasting one to two hours. After the first author interviewed all the employees in the first organization, she assessed that she had not gained sufficient insight into her object of analysis, and she sought out a second organization that provided access to a more diverse group of people (Corbin and Strauss, 2008) who ostensibly benefited from similar policies. The observation period was less intense in the second organization (around 40 hours). During data collection, a key concern that surfaced was the interviewees’ perceptions of the policies. The first author used open coding techniques (Gioia, Corely, and Hamilton, 2012; Corbin and Strauss, 2008) to capture emerging patterns, while taking into consideration the interviewees’ words, impressions and experiences. These initial codes and reflections informed our choices during later stages of the research.

During the second stage, we read through the transcribed interviews in their original language. We discussed the patterns that came to light during the first stage and the research question, and together we developed a system of temporary categories for salient concepts. We used the categories to reconcile data from the first interviews. We went through the remaining interviews separately, regularly discussing the content and emerging concepts. These temporary ‘themes’ (Gioia, Corely, and Hamilton, 2012; Corbin and Strauss, 2008) comprised policy types, the interviewees’ patterns of use, their feelings about the policies, beliefs about policy use and conjectures about whether they were entitled to use the policies, and general beliefs about the organizations and time spent at work. We also studied the interviewees’ mode of discourse, analyzing what was said, what was not said and the choice of words. These observations helped us understand overall perceptions of policy use.

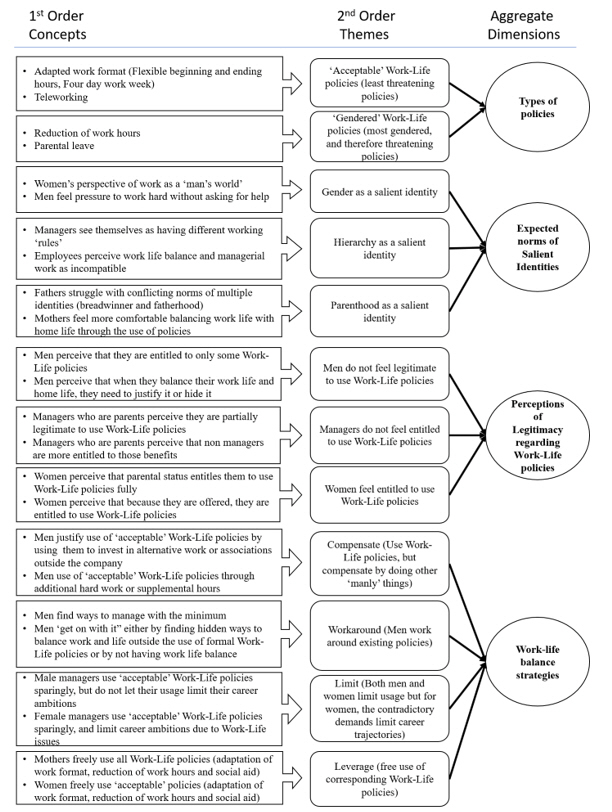

Once the key concepts began to take shape, we moved toward a more formal coding process during the third stage. We looked for patterns, meanings and relationships nested in the themes that might help explain how individuals used work-life policies. During our reflections, we considered whether our temporary themes were second-order (more specialized) themes or whether they were broader in nature. Using abductive reasoning, we created several potential data structures (see Figure 2 for the final data structure). Moving back and forth between the possible relationships, the salient concepts and the literature, we focused on an explicative representation of “what’s going on here” (Gioia, Corely, and Hamilton, 2012: 20). As it became clear that groups of people were approaching policies use in similar ways by gender, by parental status and by managerial status, we decided to use social identity theory to understand how these identities informed policies use. This is how our theoretical framework emerged.

Figure 2

Final Data Structure

2. Results

2.1 Available Work-Life Policies

Both organizations offer a variety of substantial work–life policies. We divided them into two categories: ‘gendered’ policies and ‘acceptable’ policies. ‘Gendered’ policies, which provide reduced hours and extended parental leave, are used only by mothers, who generally perceive that they are entitled to use them:

I benefited from an adoption leave. I went abroad for several months. I took maternity leave and then took a part-time position. I had the unfailing support of my boss.

mother, non-manager

We considered the policies to be ‘gendered’ because several employees believed that there are clear, negative consequences for those who take advantage of them. One employee explained:

Reductions in working hours are not very well regarded.

mother, manager

‘Acceptable’ policies, meanwhile, include adapted work formats and teleworking. They are used by men and women, and by managers and non-managers:

I chose to work for 4 days at the beginning to try [how it felt]. Finally, I said to myself, it’s necessary [for me] to agree to work longer days to get an additional day of rest.

male employee, non-manager

In other words, the ‘acceptable’ policies are the ones that, when used, are not generally perceived as having undesirable consequences.

2.2 Hidden Motives Behind Work–Life Policies Non-Use and Under-Use

When you see that [policy use] is not developed, it’s because of something. You can see it… You hear comments: “that guy took…or girl took...” I’m talking about this company, maybe other companies don’t do this but this one, it’s a bit conservative… A bit macho….

father, manager

Although the policies available at both organizations are actively publicized, their level of accessibility remains unclear. Many employees perceived a discrepancy between organizational performance goals and the work-life policies. One manager contended that individuals need to be responsible for themselves:

The company will always ask you to move it up a gear. It will always want you to go at a speed that sometimes you can’t keep up with. So I think it depends more on you, to get as close as possible to that speed that the company, the business, the market demands of you, without having to give up everything else.

father, manager

Due to the tension between these two contradictory agendas, many employees were wary of using work-life policies, as doing so could harm their career prospects:

Professionally, these [work-life] policies can slow down a career, especially in a commercial company. It slows down career progression if you have a reduced working day.

mother, non-manager

Although both companies are well known for their innovative policies, and the respective HR departments proactively publicize them, there can still be confusion and concern about using programs that may conflict with organizational goals. Additionally, employees had different opinions about the worth of such policies, their entitlement to them and the consequences of using them. In the next section, we will show how various groups perceived the legitimacy, or lack thereof, of policies use.

2.3 Men, Including Fathers, Do Not Feel Entitled to Use Work-Life Policies

In both organizations, some men did not feel they should use any work-life policies, especially if they are not fathers:

Me, I don’t have any errands to run, or anything. I don’t have to do any shopping, or pick up the kids. None of that, so for me it’s pretty simple, I don’t need it.

male, non-manager

This perspective differs considerably from those of female employees in the same position. Women use such policies without hesitation, even if only to take time off for themselves. Men, however, often feel they cannot use them—even if the HR department tells them otherwise. That widespread perception prompted one worker to claim that the policies are discriminatory because they are only for women. His view stemmed not from the actual written policies but rather from the idea that the HR department had not explicitly offered him any of the policies, even though the information was readily available. He spoke angrily:

Nobody has asked me. I don’t know if it exists and if it exists, they haven’t told us... Nobody has told me anything. I’m sure we could have things, but since they haven’t told us, I don’t know.

father, manager

Because men mostly do not feel entitled to the benefits of work-life policies, they conduct themselves accordingly. In our dataset, we encountered not a single man who had taken parental leave or reduced his hours to manage home life. Instead, men used only those policies that they perceived to be ‘acceptable’ and therefore not stigmatized.

Moreover, some men believed that they had to compensate for any policy use through direct or indirect payback. Others would not risk policy use even on such conditions. Male employees adopted the following payback strategies.

2.3.1 Compensation Strategies

Some men compensated for using work-life policies by paying back their employer: they worked harder or agreed to extra hours. For example, one man confessed his fear of retaliation for using such programs if he declined to accept overtime work:

I have a 4-day week, but if I’m asked to do additional hours, I say yes right away. That’s the whole thing. Maybe I’m also unconsciously afraid of being seen as bad if I say no. Well, I really have the impression, even if it’s not true, not necessarily… I’m afraid of that.

male, non-manager

Many men were willing to use ‘acceptable’ policies but justified using them on the grounds that they used the time away from the workplace to work outside the organization in other capacities. For instance, some men devoted time to second jobs, started businesses or participated in associations for sports or politics. The employee below explained what prompted him to finally accept teleworking:

I have a company. I don’t take care of all of it, but there are certain functions I have to do. Before, what I was doing was managing the two things without having a life. So, I [said to myself], look, either I stop traveling or I have to quit. So, for personal reasons, also because of the child, I requested the possibility of teleworking.

father, non-manager

This worker had children, so he was entitled to reduce his hours in addition to teleworking or doing a 4-day workweek. Yet he did not try to benefit from the programs. Additionally, his discourse aimed to justify policies use by emphasizing his outside work, not his children. This explanation sharply contrasts with what the mothers would say.

2.3.2 Workaround Strategies

Another male strategy was to find ways outside use of formal policies to create a balance between time for work and time for home life. For instance, one salesperson explained how he built flexibility into his work routine so that he did not have to use work-life policies:

I am a salesperson. My office is here in Madrid, but depending on the opportunities, I can leave at noon, for one day or one week, depending on the client and the opportunity. You see customers until eight, eight-thirty in the evening. You travel. You come. You go. It is part of my job to spend more time being on alert. I have to be on the phone, I have to be doing errands… So if one day I need to pick up my son at daycare, of course I will do it during those times.

father, non- manager

Finally, some men tried to find ways to manage with no use of work-life policies and would wear such ostensible commitment as a badge of honour:

I have never taken a day of sick leave for children in my life. Because I have managed otherwise, and I tell you, I feel that I did not have children to take advantage of [work-life policies]. I have never received social aid for families either. That’s my business.

father, manager

Overall, men do not perceive their needs as sufficiently legitimate to justify use of work-life policies. So they either compensate through overtime work, if they do use them, or find ways to work around work-life imbalances.

2.4 Women, Including Mothers, Feel Entitled to Use Work-Life Policies

In contrast to men, women experience and acknowledge the organization as a ‘man’s world.’

The professional world is a man’s world. It is a world made by men. Unfortunately, women have gone into it, full force, giving 150%, and also carrying most of the [family burden]. If it is a world made by men, then the rules that govern it are those of men.

mother, manager

This way of seeing things is perhaps why women experience work–life policies use differently, as we will discuss below.

2.4.1 Leverage Strategies

Because of their attitude toward work-life policies use, women can leverage the available programs without reserve. Whether they are mothers or have outside work, they feel they have the right to use them. For example, one woman said:

I said to myself, why not? I work more during some days and have other days when I work less or more days off to allow me to do something else on the side. It allows me to go to the gym for 2.5 hours every day or to go play sports.

mother, non-manager

Additionally, women feel that parental status fully entitles them to fewer work hours. This tendency was consistently observed across all non-manager mothers:

When I knew about the schedule adjustments, I immediately said that I preferred to change, because I was alone at the time and I had my little girl to take care of.

mother, non-manager

Due to these beliefs, mothers experience no guilt or reservation when requesting reduced hours, a request seen as ‘normal’ behaviour:

I feel particularly fortunate because I have two small children. With the first one I took parental leave, and with the second one, I took a reduced working day for two-and-a-half years. I have no complaints because whenever I needed it, I asked for it, [and] they gave it to me. And now I am back to my normal working day from eight to five-thirty.

mother, non-manager

Only women normalize policies use in this way. The parental experience is very different for fathers, who try to adapt without recourse to such programs:

Instead of leaving at 7 o’clock, I say to myself, I’ll finish this in a half hour, leave earlier and I’ll be with my daughter for a half hour more. But it’s a change of mentality for everyone. Before I didn’t have to do it. Even though I was married, I felt like a bachelor who was more dedicated to work than to anything else.

father, manager

It is startling to observe the difference between the way men and women view and use work-life policies. Interestingly, when it comes to managers who are also parents, we do not see such differences and the same patterns recur for both men and women.

2.5 Managers, Including Fathers and Mothers, Do Not Feel Entirely Entitled to Use Work-Life Policies

Managers who are fathers see themselves as having a different set of ‘rules’ they must abide by:

It’s true that it’s difficult to manage your work time as a manager. You can’t say to yourself: I have to finish at half past twelve, and at half past twelve I’m gone. Even if I try to do it, I can’t. You start something or you get a phone call. You’re not going to hang up or say to the person: no, it’s half past noon, I’m done. You can’t do that.

father, manager

Similarly, mothers also hold managerial duties to a higher standard:

It’s not a job that ends at 5:30. It’s a job that implies endless working days, having to work on weekends, being called at whatever time.

mother, manager

Because of informal rules such as these, managers consider themselves only partially able to use work-life policies. Several interviewees talked about such programs being great for workers but did not feel that they, as managers, could enjoy them:

I didn’t want a reduced working day (I had it during the breastfeeding period but nothing else). I’m a manager, so it’s like a reduced working day and my type of work don’t reconcile very well.

mother, manager

Like non-manager male employees, managers who are parents suspect that use of work-life policies may have consequences:

I think that in this company, it would be OK if you take a leave of absence. It is not that they would throw you aside because you’ve asked for it. But because your position has to be filled, … in a year of work [your replacement] surely demonstrates at least what you’ve demonstrated. So they’re not going to fire that person so that you can come back.

father, manager

2.5.1 Limiting Strategies

Because of such tensions, manager parents seek to limit their use of work-life policies. One way is to use only ‘acceptable’ policies , as the quote below shows. The manager here felt he could not take reduced hours because of the impression it gave to others:

Reconciling is OK, as long as it doesn’t affect my professional development. For example, there are people who may be working 4, 5 or 6 hours. But even if your office is the last one I see with the light on, it seems that you haven’t worked… So I have no problem with adapting my working day to make it compatible with my family, so long as it doesn’t affect my professional development in my company.

father, manager

The female managers in our study show the same behavioral patterns. Another limiting strategy is to use such policies sparingly:

It seems to me that those of us in IT have to be here all day, in case the cable goes down or the server goes down. It’s true, well in a way... Asking for a reduction in working hours is still a taboo .

mother, manager

One difference between male and female managers, however, is how they perceive and adapt to their career trajectory. For men, this did not seem to be much of a problem, whereas many women confessed they had passed up opportunities for promotion if, as a consequence, they would have been unable to manage the work–life balance. One manager explained her choice:

With a managerial position, it’s impossible to complete work on a schedule from 8:30 to 5:30. This isn’t expected from a manager… And that’s why I declined the offer of a promotion. I was proud that they had offered it to me and thought of me, but it wasn’t the most appropriate time in my family situation. For me, my family situation was more important than this great job opportunity.

mother, manager

3. Discussion

As mentioned earlier, the work–life balance literature (e.g., Williams, Berdahl and Vandello, 2016; Bourdeau, Ollier-Malaterre and Houlfort, 2019) has shown a divergence between an increase in the availability of work-life policies and a more modest increase in their use. The literature also proposes how this divergence may be partially due to the norm of the ‘ideal worker’ (Las Heras, Chinchilla and Grau Grau, 2019; Neely, 2020; Minnotte and Minnotte, 2021). We examined why employees are not using work-life policies despite their growing availability within organizations. We found that the policies are used differently depending on the employees’ social group, and that certain salient social identities—such as gender, parenthood and managerial status—shape their use. Such programs have been a structural and cultural change for organizations (Kossek et al., 2010) and often present an opportunity for redefining the meaning of work. At the same time, the values inherent in them, including resting and taking time for oneself or for one’s family, may conflict with the ideal norms that define salient identities. Our results show three ways in which the ‘ideal worker’ norm inhibits policies use in the cases of male employees and female managers.

First, from an organizational perspective, the traditionally masculine values associated with the ‘ideal worker’ are intuitively linked to performance and production of positive results—e.g., increased profit, status and recognition. This linkage contrasts with work–life policies that endeavour to redefine success in terms of well-being and time spent with the family. The clash between the two, which permeated the interviews, causes employees to fall back on the social identity or identities they find meaningful. Our findings show three main strategies that individuals use when they feel that their social identity is threatened: (1) engage in workaround activities to avoid using work-life policies; (2) try to compensate for policies use; and (3) significantly limit policies use.

Second, expectations for men’s social identities tend to align with ‘ideal worker’ norms and the employer’s focus on financial achievement and performance. Such expectations hinder men (both fathers and non-fathers) from taking advantage of work-life policies. In the organizations we studied, men did not feel entitled to use the programs, so they did one of two things: they compensated for using them by working additional hours or by working on other projects outside the company; or they found workarounds to manage their private life discreetly, either with or without policies use. This attitude differed drastically from that of non-manager women, who used such programs without reserve. Hence, policies use by non-managers strengthened gender norms for both men and women. Men used only certain programs, while rejecting stigmatized ones like reduced hours or parental leave.

Third, the ‘ideal worker’ norm shapes the way managers, both men and women, treat work-life policies. In both cases, managers limit their use of programs in two ways. One is to take advantage only of ‘acceptable’ policies and the other is to use any work-life policies sparingly. In the case of managers, it is noteworthy that, while the ‘ideal worker’ norm influences both men and women, it affects each gender differently. For male managers, the ‘ideal worker’ norm does not impact their career trajectory. For female managers, it keeps them from accepting positions at higher levels in the organizational hierarchy. These gender differences are depicted in Figure 3.

Figure 3

How Social Identities Shape Work-Life Policies Use

3.1 Theoretical Contribution

As outlined previously, our theoretical framework indicates why employees do not fully use work-life policies. Our empirical study supports the work of Williams and colleagues (2016), who suggest that social norms are still powerful organizational forces that shape how employees respond to such programs. We explore the reasons by revealing the dynamics between the salient identities of employees and their perceptions of legitimacy. Legitimacy implies that an individual’s actions are desirable, proper or appropriate within a certain socially constructed system of norms, values, beliefs and definitions (Suchman, 1995). Our findings indicate that not everyone—and this is especially true for managers and male employees—believes in the validity of wanting more flexibility in the workplace and a better work-life balance. When individuals identify with the ‘ideal worker’ norm, they may perceive such measures as being neither appropriate to their positions nor welcome in the light of dominant organizational norms, even if the employer actively advocates the opposite.

In the organizations we studied, the gap between work-life discourse and the reality of work—, which reflects a focus on performance goals—means that some employees do not consider themselves to be legitimate. To better understand this gap, we refer to legitimacy research (e.g., Bitektine and Haack, 2015) to explain the attitudes of some individuals in our study. Legitimacy includes social evaluation through collective consensus and through the evaluator’s self-judgment (Haack and Sieweke, 2018). Consequently, when managers and male employees do not receive validation from their work environment for policy use (Williams et. al., 2013), they come to believe in their own lack of legitimacy. Moreover, we provide evidence that policies use can be perceived as feminizing or at least threatening the ‘ideal worker’ image, thus leading to the emergence of hidden strategies for management of personal lives. Our framework provides insight into the strategies that managers and male workers use to achieve work–life balance while continuing to conform to traditional conceptions of gendered behaviours.

Our research also responds to calls (e.g., Perrigino et al., 2018) for better understanding of why and how current use of work-life policies by both men and women perpetuates ‘ideal worker’ stereotypes. Indeed, we argue that policies use strengthens social norms. Given how the traditional role of caregiving creates expectations for women to devote more attention to the family (Eagly, 1987), we thought it worthwhile to examine the evidence on how such expectations can provide women with a legitimate reason to use work-life policies. Because women feel more justified than men to use them, they use them more often, thus strengthening stereotypes of men as ‘ideal workers,’ and the notion that ‘ideal workers’ are men because they are unencumbered.

Particularly intriguing is our finding that the ‘ideal worker’ norm leads female managers to abandon career advancement. Working mothers experience a clash of social ideals: the ‘ideal worker’ should always be available to his/her employer and the ‘ideal mother’ should always be available to her family (Ladge and Greenberg, 2015; 2019). Identity threat theory may explain why female managers choose to forego promotion opportunities. Despite the recent blurring of gender roles (Powell et al., 2019), female managers anticipate work–life conflict and lack of support from their families. For ‘ideal worker’ mothers, a mother who takes leave and uses workplace flexibility is a bad employee; for ‘ideal mothers,’ a mother who invests too much time in work is a bad mother (Williams and Dempsey, 2014). This tug-of-war among women not only constrains their advancement within the organizational hierarchy but also strengthens stereotypical norms.

A final contribution of our research relates to advancement of our understanding of the strategies men and women use to protect their social identities while maintaining their work-life balance. Our findings not only show how employees internalize ideal norms into their salient identities but also how individuals handle the divergences between corporate performance goals and work-life mandates. Because work-life balance is not always in line with how male employees and managers view themselves, these workplace actors maintain or protect their identity by pursuing alternative, somewhat more informal, strategies to maintain their work–life balance. Our research supports previous studies by showing how, when feeling threatened, individuals are likely to turn to identity protection (Petriglieri, 2011) or identity restructuring (Chen and Reay, 2020). Our theoretical framework contributes to this corpus by exposing the underlying processes of identity protection within the work–life balance context.

3.2 Limitations and Future Research Directions

The limitations of this study provide several opportunities for additional research. First, we studied two companies from two industries in southern Europe. While our study responds to a call for research on work-life balance in diverse industries and countries (Williams et al., 2016), the specific contexts may not fully represent work environments in general. Research could be extended to different industries and countries, as a basis for comparison. Second, our study included men, women, managers, non-managers, parents and non-parents; however, all the managers in the sample were parents. Future research could compare our results with those obtained for managers without children to determine whether there are differences between the two groups. Finally, the COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted organizational structures (Schieman et al., 2021). By causing a shift to remote work, along with increased job and domestic demands in the face of reduced support, the pandemic has shattered the work/non-work boundary for many workers. It has initiated major structural and cultural changes in organizations. We recommend investigating how the pandemic has impacted the ‘ideal worker’ norm and work-life policies use to determine whether dominant norms have been overturned.

Practical Insights and Conclusion

Employers need to think about reconciling the contradictions between focusing on performance and wanting to promote work-life balance. If they send mixed messages that contain implicit goals and explicit offers, they will only create dissonance and distrust amongst their employees. Such contradictions will push the latter to fall back on stereotypical behaviours and values, the result being stigmatization of certain work-life policies and strengthening of attitudes that perpetuate inequality in the workplace. If employers wish to support work–life balance, they should ensure that the work-life policies are consistent and compatible with work practices and career goals. They must be attentive to the individual’s diverse identities and promote such programs not only for women but also for men and managers, so that work–life balance does not remain a mere promise but also something all employees believe they are entitled to enjoy. One way to initiate this change would be to encourage managers to shape how work-life policies are used and thereby trigger an evolution of dominant norms. Organizational success depends to some degree on employee well-being, an area in which some employers have been effective and gained due recognition. The mix of solutions invariably goes beyond just work-life initiatives and often includes such elements as balanced score cards that encourage employee well-being. Without these holistic approaches, organizations may provide misleading information about their social responsibility. This ‘work–life balance washing’ is detrimental both to employees (whether men or women) and to employers.

Parties annexes

References

- ACKER, J. (1990). ‘Hierarchies, Jobs, Bodies: A Theory of Gendered Organizations’. Gender & Society 4(2): 139–58.

- ASHFORTH, B. E. and MAEL, F. (1989). ‘Social Identity Theory and the Organization’. The Academy of Management Review, 14(1): 20-39.

- BEAUREGARD, T. A. and L. C. HENRY, (2009). ‘Making the link between work-life balance practices and organizational performance’. Human Resource Management Review, 19: 9-22.

- BITEKTINE, A. and HAACK, P. (2015). ‘The “macro” and the “micro” of Legitimacy: Toward a Multilevel Theory of the Legitimacy Process’. Academy of Management Review 40(1): 49–75.

- BLAIR-LOY M. (2003). ‘Competing Devotions: Career and Family among Women Executives’. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- BLAIR-LOY M. (2004). ‘Work devotion and work time’. In: C.F. Epstein and A.L. Kalleberg (Eds.). Fighting for Time: Shifting Boundaries of Work and Social Life (pp. 216–282).

- BOURDEAU, S., OLLIER-MALATERRE, A., and HOULFORT, N. (2019). ‘Not all work-life policies are created equal: Career consequences of using enabling versus enclosing work-life policies’. Academy of Management Review, 44: 172–193.

- BRESCOLL, V. L., GLASS, J., and SEDLOVSKAYA, A. (2013). ‘Ask and we shall receive? The dynamics of employer-provided flexible work options and the need for public policy’. Journal of Social Issues, 69: 367–388.

- CHEN, Y., and REAY, T. (2020). ‘Responding to imposed job redesign: The evolving dynamics of work and identity in restructuring professional identity." Human Relations 74(10): 1541-1571.

- COLTRANE S., MILLER E. C., DEHAAN T., and STEWART, L. (2013) ‘Fathers and the Flexibility Stigma’, Journal of Social Issues 69(2): 279–302.

- CORBIN, J., and STRAUSS, A. (2008). Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory, 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publishing.

- DOZ, Y. L. (2011). Qualitative research for international business. Journal of International Business Studies, 42(5): 582–590.

- DUMAS, T., and SANCHEZ-BURKS, J. (2015). ‘The Professional, the Personal and the Ideal Worker: Pressures and Objectives Shaping the Boundary between Life Domains’, The Academy of Management Annals, DOI:10.1080/19416520.2015.1028810.

- EAGLY, A. H. (1987). Sex Differences in Social Behavior: A Social Role Interpretation. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- EDMONDSON, A. C., and MCMANUS, S. E. (2007). ‘Methodological fit in management field research’. The Academy of Management Review, 32(4): 1155–1179.

- FOUCREAULT, A., OLLIER-MALATERRE, A. and MÉNARD, J. (2018). ‘Organizational Culture and Work-Life Integration: A Barrier to Employees’ Respite?’. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 29(16): 2378–2398.

- GAJENDRAN, R. S., and HARRISON, D. A. (2007). ‘The good, the bad, and the unknown about telecommuting: Meta-analysis of psychological mediators and individual consequences’. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92: 1524– 1541.

- GARIETY, B. S., and SHAFFER, S. (2001). ‘Wage differentials associated with flextime’. Monthly Labor Review, 3: 68–75.

- GIOIA, D. A., CORLEY, K. G., and HAMILTON, A. L. (2012). ‘Seeking qualitative rigor in inductive research: Notes on the Gioia methodology’. Organizational Research Methods, 16: 15-31.

- HAACK, P. and SIEWEKE, J. (2018). ‘The Legitimacy of Inequality: Integrating the Perspectives of System Justification and Social Judgment’. Journal of Management Studies 55(3): 486–516.

- HORNSEY, M. J. (2008). ‘Social identity theory and self‐categorization theory: A historical review’. Social and Personality Psychology Compass 2(1): 204-222.

- HUMBERD B., LADGE J. J. and HARRINGTON B. (2015). ‘The “new” Dad: Navigating Fathering Identity within Organizational Contexts’. Journal of Business and Psychology 30(2): 249–66.

- KMEC, J.A., TRIMBLE O’CONNOR L., and SCHIEMAN S. (2014). ‘Not Ideal: The Association between Working Anything but Full Time and Perceived Unfair Treatment.’ Work and Occupations 41(1):63–85. .

- KOSSEK, E. E., LEWIS, S., and HAMMER, L. (2010). ‘Work family initiatives and organizational change: Mixed messages in moving from the margins to the mainstream’. Human Relations, 61: 3–19.

- KOSSEK, E. E., and MICHEL, J. (2011). ‘Flexible work schedules’. In: S. Zedeck (Ed.), APA Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 1: 535–572. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- KVANDE, E., BRANDTH, B., and HALRYNJO, S. (2017). ‘Integrating work and family’. In: B. Brandt, S. Halrynjo, and E. Kvande (Eds.), Work-Family Dynamics: Competing Logics of Regulation, Economy and Morals: 1–16. London: Routledge.

- LADGE, J. J., and LITTLE, L. M. (2019). ‘When expectations become reality: Work-family image management and identity adaptation’. Academy of Management Review, 44: 126–149.

- LADGE, J. J., and GREENBERG, D. (2019). Maternal Optimism: Forging Positive Paths through Work and Motherhood. 1st Edition. Oxford University Press.

- LADGE, J. J., and GREENBERG, D. (2015). ‘Becoming a Working Mother: Managing Identity and Efficacy Uncertainties During Resocialization’. Human Resource Management 54(6).

- LAS HERAS MAESTRO, M., CHINCHILLA ALBIOL, N. and GRAU GRAU, M. (2019). The New Ideal Worker:Organizations between Work-Life Balance, Gender and Leadership. Springer Ed.

- LESLIE L. M., PARK, T.-Y., MEHNG, S. A., and MANCHESTER, C. F. (2012). ‘Flexible Work Practices: A Source of Career Premiums or Penalties?’ Academy of Management Journal, 55(6): 1407–1428. doi:10.5465/ami.2010.0651.

- MINNOTTE, K. L. and MINNOTTE, M. C. (2021). ‘The Ideal Worker Norm and Workplace Social Support among U.S. Workers’. Sociological Focus, 54:2, 120-137,

- MOEN, P., KELLY, E. L., FAN, W., LEE S., ALMEIDA, D., KOSSEK, E. and M. BUXTON, O., (2016). ‘Does a Flexibility/Support Organizational Initiative Improve High-Tech Employees’ Well-Being? Evidence from the Work, Family, and Health Network’. American Sociological Review 2016, Vol. 81(1) 134– 164.

- NEELY, M. T. (2020). ‘The portfolio ideal worker: Insecurity and inequality in the new economy’. Qualitative Sociology 43(2): 271-296.

- PERRIGINO, M. B., DUNFORD, B. B., and WILSON, K. S. (2018). ‘Work–family backlash: The "dark side" of work–life balance (WLB) policies’. The Academy of Management Annals, 12(2), 600–630. https://doi.org/10.5465/annals.2016.0077

- PETRIGLIERI, J. L. (2011). ‘Under threat: Responses to and the consequences of threats to individuals' identities’. Academy of Management Review, 36(4), 641-662.

- POWELL, G.N., GREENHAUS, J.H., ALLEN, T.D. and JOHNSON, R.E. (2019). ‘Introduction to special Topic Forum on Advancing and Expanding Work-Life Theory from Multiple Perspectives’. Academy of Management Review, 44(1): 54-71.

- REID E. (2015). ‘Embracing, Passing, Revealing, and the Ideal Worker Image: How People Navigate Expected and Experienced Professional Identities’. Organization Science 26(4): 997–1017.

- ROGIER, S. and PADGETT, M. (2004). ‘The Impact of Utilizing a Flexible Work Schedule on the Perceived Career Advancement Potential of Women’. Human Resource Development Quarterly. 15 (1).89-104

- RUDMAN L. A. and MESCHER K. (2013). ‘Penalizing Men Who Request a Family Leave: Is Flexibility Stigma a Femininity Stigma?’. Journal of Social Issues 69(2): 322–40.

- SCHIEMAN, S., BADAWY, P. J. A., MILKIE, M., and BIERMAN, A. (2021). ‘Work-life conflict during the COVID-19 pandemic’. Socius: Sociological Research for a Dynamic World, 7(3), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/2378023120982856

- STONE P. (2007). ‘Opting Out? Why Women Really Quit Careers and Head Home?’ University of California Press, Berkeley.

- SUCHMAN, M. C. (1995). ‘Managing Legitimacy: Strategic and Institutional Approaches’, Academy of Management Review 20(3): 571–610.

- TAJFEL, H. and TURNER, J.C. (1985). ‘The Social Identity Theory of Intergroup Behaviour’. In: Worchel, S. and Austin, W.G., Eds., Psychology of Intergroup Relations, 2nd Edition, Nelson Hall, Chicago, 7-24.

- TANQUEREL, S. and GRAU-GRAU, M. (2020). ‘Unmasking Work-Family Balance Barriers and Strategies Among Working Fathers in the Workplace’. Organization, 27(5): 668-700.

- WEEDEN, K. A. (2005). ‘Is there a flexiglass ceiling? Flexible work arrangements and wages in the United States’. Social Science Research, 34: 454–482.

- WHARTON, A. S., CHIVERS, S., and BLAIR-LOY, M. (2008). ‘Use of formal and informal work-family policies on the digital assembly line’. Work and Occupations, 35: 327–350.

- WILLIAMS, J. C. (2000). ‘Unbending Gender: Why Work and Family Conflict and What to Do about It’. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- WILLIAMS, J. C., BLAIR-LOY M. and BERDAHL J. L. (2013). ‘Cultural Schemas, Social Class, and the Flexibility Stigma’. Journal of Social Issues 69(2): 209–34.

- WILLIAMS, J.C., DEMPSEY, R. (2014). ‘What Works for Women at Work: Four Patterns Working Women Need to Know’. New York: NYU Press

- WILLIAMS, J. C., BERDAHL, J. L., and VANDELLO, J. A. (2016). ‘Beyond work-life “integration’. Annual Review of Psychology, 67: 515–539.

Liste des figures

Figure 1

Interviewee Characteristics

Figure 2

Final Data Structure

Figure 3

How Social Identities Shape Work-Life Policies Use