Résumés

Abstract

In the nineteenth century, municipal authorities in Canadian cities faced a common set of environmental challenges associated with domestic livestock animals. This article examines the regulation of livestock in Montreal, Toronto, and Winnipeg. As these cities each grew over the course of the nineteenth century, their urban environments became ecologically more alike and their responses to animal nuisances reflected these ecological similarities. Municipal authorities in each of these cities adopted broadly similar approaches to the regulation of livestock animals. Over the course of the nineteenth century, municipal governments developed extensive and increasingly restrictive bylaws, pound systems, and public health regulations to control the use of livestock. These approaches to livestock regulation were the results of emerging common ecological transformations in cities as humans attempted to live together with domestic animals in increasingly densely populated spaces.

Résumé

Au 19e siècle, les autorités municipales du Canada faisaient face à un ensemble de défis environnementaux liés au bétail. Cet article étudie la réglementation du bétail à Montréal, à Toronto et à Winnipeg. Pendant que ces villes augmentaient de taille au 19e siècle, leur environnement urbain se ressemblait de plus en plus et leurs réponses à la nuisance animale reflétaient ces similitudes écologiques. Les autorités municipales dans chacune de ces villes ont adopté des approches similaires à la réglementation du bétail. Au cours du 19e siècle, les gouvernements municipaux ont développé des règlements détaillés et de plus en plus restrictifs, des systèmes de fourrière et des règlements de santé publique pour contrôler l’usage du bétail. Ces approches à l’égard de la règlementation du bétail furent le résultat de transformations écologiques communes et émergentes dans les villes pendant que les humains essayaient d’y vivre avec des animaux domestiques, dans des espaces de plus en plus densément peuplés.

Corps de l’article

In 1883, police in Montreal impounded 203 horses, 114 cows, 31 sheep, 13 goats, and 1 pig. In that same year, the City of Toronto paid compensation to four petitioners “for Sheep worried by Dogs.” T. Crawford, E. Blong, Allan Crabtree, and J.E. Verrall received $191.98 to offset the damages they incurred when their sheep came into conflict with dogs on the streets of Toronto. Also in that same year, Acton Burrows, deputy minister of agriculture for the province of Manitoba, wrote a letter to the mayor of Winnipeg, expressing concern over the spread of glanders among horses in the city and the “dozen carcasses of dead horses lying within the City limits.” He kindly requested that “for the protection of the many valuable horses in the City, it is most desirable that some steps be taken to have the bodies of horses dying from infectious or contagious diseases destroyed at once.” In the nineteenth century, municipal governments in Canada devoted substantial time and attention to the management and regulation of domestic livestock animals.[1]

As recent literature in urban geography, environmental history, and animal studies has shown, domestic animals played an important role in the development of industrial cities in the nineteenth century.[2] From London to Paris to New York City, cows, horses, pigs, and other livestock populated urban environments and contributed to economic growth and development. Indeed, the sustainability of large, dense populations of humans in nineteenth-century cities depended upon the exploitation of domestic animals for food and labour. Livestock husbandry was once a daily part of urban life (figure 1). As I have argued elsewhere, people developed cities as environments that facilitated a relationship among humans and domestic animals that can be characterized as asymmetrical symbiosis.[3]

Building upon that argument, this article provides comparative analysis of the management of animal nuisances in Montreal, Toronto, and Winnipeg in the nineteenth century, revealing insights into the processes and ecological consequences of urbanization. What stands out most from this analysis is that municipal authorities in each of these cities adopted broadly similar approaches to the regulation of livestock animals. They did so mainly because they faced a common set of environmental challenges and concerns associated with the presence of livestock animals in cities. The most significant differences in the responses of these municipal governments to the regulation of livestock occurred in Winnipeg, a city that was smaller and younger than Montreal and Toronto. Even still, Winnipeg’s regulations had much in common with those of the two largest cities in the country. Over the course of the nineteenth century, municipal governments developed extensive and increasingly restrictive bylaws, pound systems, and public health regulations to control urban livestock husbandry. These approaches to livestock regulation were the results of emerging common ecological transformations in cities as humans attempted to live together with other animals in increasingly densely populated spaces. As urban environments changed over the course of the nineteenth century—with increased crowding and environmental pollution—the terms of the relationship between people and livestock animals changed as well. For some, these animals became nuisances, hazards, and threats. For others, they remained vital to economic life in the city. Although most Canadian urban dwellers continued to rely upon animal bodies for labour and food, by the end of the nineteenth century, they sought further spatial segregation from livestock animals in their everyday lives.

Figure 1

Livestock animals were part of the ordinary experiences of nineteenth- and early twentieth-century urban life

This article contributes to our understanding of comparative urban ecology. In the nineteenth century, the common approach to the management of livestock in Montreal, Toronto, and Winnipeg was the result of ecological convergence associated with urbanization. Urban ecologists have shown that cities around the world share common ecological characteristics and patterns. As Jari Niemelä, D. Johan Kotze, and Vesa Yli-Pelkonen argue, “Urbanisation creates patchworks of modified land types that exhibit similar patterns throughout the world.” The development of these three nineteenth-century Canadian cities shows part of the process by which urban environments in Canada became ecologically alike and some of the ways municipal governments responded to these changes. Montreal, Toronto, and Winnipeg certainly did not have identical urban ecosystems. There are differences in climate, geography, populations of wild animals and insects, and much more. In spite of their local idiosyncrasies, however, these cities came to share many ecological characteristics with one another and with other industrialized cities around the world. All three cities experienced broadly similar environmental outcomes as a result of urbanization. The keystone species of urban environments (humans) unquestionably dominated cities of the nineteenth century and did so in ways that produced remarkable ecological convergence. Part of the ecological convergence was the introduction and use of dense populations of livestock animals. Had people used radically different compositions of livestock animals in North American cities, the ecological consequences of urbanization from one city to the next might have been quite different. For instance, if Montreal had relied mainly on oxen as draught animals instead of horses, it might have been spared the effects of the 1872 equine influenza epizootic that struck nearly every city in urban North America. If Winnipeggers had relied on goat’s milk, the environmental consequences might have looked rather different from those in Toronto or Montreal where bovine milk was the milk of choice. If the majority of Torontonians had abstained from eating the meat of pigs, the regulation of free-range livestock husbandry might have taken a different form. The common species composition and rapid human population growth of nineteenth-century Canadian cities produced similar environmental outcomes and challenges associated with so-called animal nuisances.[4]

The regulation of domestic livestock animals in Montreal, Toronto, and Winnipeg over the course of the nineteenth century is the main focus of this article. It does not, however, consider the place of wild animals in these cities, nor does it consider domestic companion animals. Wild animals and invasive synanthropes were certainly present in these three cities and they influenced transformations in urban ecology. For instance, rats, pigeons, raccoons, and squirrels were just some of the wild animal species to become “urbanized” over the course of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.[5] They were not, however, the object of municipal regulation in Canadian cities prior to the twentieth century. Domestic companion animals also lived in Canadian cities in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the most common of which were cats and dogs. However, municipal governments in Montreal, Toronto, and Winnipeg applied no regulatory attention to cats (they are almost entirely invisible in the historical record). They began regulating dogs in the nineteenth century, but for reasons that were distinct from livestock. For the most part, Canadian city dwellers did not use dogs for food and labour. The regulation of dogs as a nuisance therefore was distinct, because authorities did not simultaneously have to consider the economic role the animal played in the city. Dog regulations are not easily comparable to the regulation of urban livestock.[6] Finally, the statistics on the presence of dogs in nineteenth-century Canadian cities are not clear. Census enumerators did not track urban dog populations, as they did with urban livestock animals. Further historical research on wild animals and domestic companion animals in Canadian cities would add to our understanding of the development of urban environments and the ecological consequences of urbanization in Canada.

This article begins by comparing the demographic history of urban livestock animals in these three cities between the census years of 1861 and 1911, revealing the extent to which Canada’s largest and fastest-growing urban centres were composed of similar assemblages of domestic livestock animals and exhibited common changes over time. Next, it explores municipal regulations that addressed two primary environmental challenges related to the presence of domestic livestock in these urban environments: animal movement and animals as public health risks.

Counting Domestic Animals in Canadian Cities

Although the documentation of domestic livestock populations in nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Canadian cities is limited, there is sufficient evidence to show general trends in the animal compositions of Montreal, Toronto, and Winnipeg. That evidence reveals that Canada’s largest and fastest growing cities were inhabited by similar assemblages (and substantial numbers) of domestic livestock animals along with their human owners. Remarkably, enumerators for the agricultural census counted the livestock populations in cities, towns, and villages as early as 1851. As she argues in her ground-breaking article on the keeping of pigs in nineteenth-century Montreal, Bettina Bradbury found the agricultural censuses to be a “rough indication” of the livestock population, including those found in cities. She also emphasized the degree to which census data could represent only a snapshot of the animal populations of cities and likely underestimated the extent of urban livestock in Canada. In the case of the 1861 census in Montreal, for instance, that population was likely underestimated because the count took place in January, a time of year when many working-class families would have sold or slaughtered their animals to avoid the expenses associated with winter feeding and shelter.[7]

In spite of such limitations, the census data reveal certain patterns of change over time in the livestock animal populations of Montreal, Toronto, and Winnipeg between 1861 and 1911.[8] Enumerators had instructions to count livestock on all lots in “Cities, Towns and villages,” tracking the number and value of a wide range of species. This included horses, milch cows, pigs, sheep, oxen and other horned cattle, chickens, geese, ducks, turkeys, and beehives. The only significant urban livestock left out of the count were goats. While goats do not appear in the census, pound-keeper and police records reveal the presence of such animals. The inclusion of urban livestock in the agricultural census provides evidence of the importance of livestock husbandry to early urban economies in Canada. From 1861 to 1911, census takers kept consistent census categories for horses, milch cows, pigs, and sheep. In 1891, enumerators began to track chickens. With these records, we can compare what would become Canada’s three largest cities by 1911 and observe some trends in the changing urban animal population over time (figures 2–6).[9]

Figure 2

Horse populations of Montreal, Toronto, and Winnipeg, 1861–1911

Figure 3

Pig populations of Montreal, Toronto, and Winnipeg, 1861–1911

Figure 4

Milch cow populations of Montreal, Toronto, and Winnipeg, 1861–1911

Figure 5

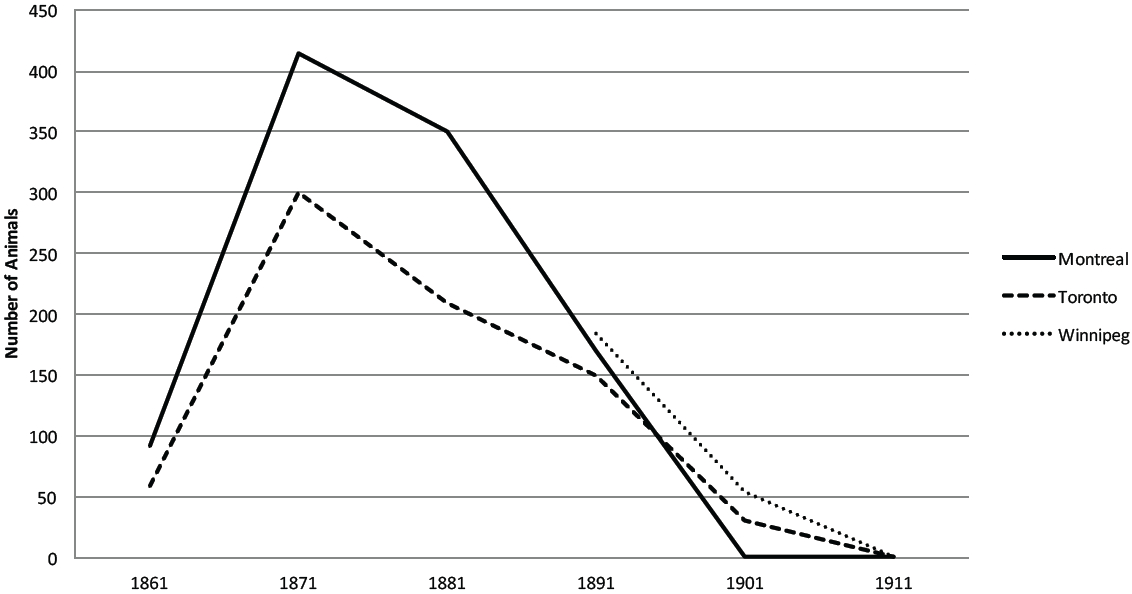

Sheep populations of Montreal, Toronto, and Winnipeg, 1861–1911

Figure 6

Hen and chicken populations of Montreal, Toronto, and Winnipeg, 1861–1911

The composition of domestic livestock animals in Montreal, Toronto, and Winnipeg consisted of a common assemblage of large ungulates, including horses, milch cows, pigs, and sheep. In Canada, there were no radical departures in the types of species urban dwellers used for food and labour. No city used oxen, mules, donkeys, or even camels in substantial numbers as alternatives to the four primary large domestic ungulates. Between 1861 and 1911, horses were the most populous large livestock animals, and sheep were the least populous in all three cities. Milch cows and pigs were also numerous in these cities.

All three cities experienced rapid urbanization and human population growth toward the end of the nineteenth century (figure 7). This was especially true for Winnipeg, one of Canada’s first western prairie towns to experience sudden exponential population growth at the turn of the century, jumping from a population of just over 25,000 in 1881 to more than 136,000 by 1911. While the human populations of these cities grew at extraordinary rates, large domestic ungulates (horses, milch cows, sheep, and pigs) declined as a proportion of the total population when compared to human population growth, especially toward the turn of the century (figure 8). For instance, in Montreal in 1871, there were about 5.75 large domestic ungulates for every hundred humans enumerated in the census for that year. As a proportion, however, large domestic ungulates declined to 0.86 for every hundred humans in the census by 1911, as humans became the fastest growing species of large mammals in the city by population. Toronto experienced a similar decline in the proportional number of large domestic ungulates in the city relative to the human population, dropping to 1.73 for every hundred people by 1911. In Winnipeg the decline was even sharper, partially a reflection of the rapid human population growth in the years between 1881 and 1911 as the city grew from a small prairie town to a regional metropolis. Overall, the evidence shows a general trend of Canadian cities becoming predominantly human habitat by the early decades of the twentieth century with a smaller place for large domestic livestock over time. Part of the explanation for the general and nearly simultaneous decline of large domestic ungulates in these cities can be found in the increasingly restrictive bylaws concerning the keeping of urban livestock. As municipal regulations became more restrictive, urban residents ceased keeping such animals or ceased reporting the presence of such animals to census enumerators.

The demographic history of livestock in urban environments, however, was not simply a story of gradual decline. While the human population of Canadian cities grew rapidly in the early years of the twentieth century, industrial urbanization did not herald the complete extirpation of domestic livestock animals from the urban environment. Instead, it transformed the ecology of cities as multi-species habitat, reconfiguring the distribution of animal species as practices of urban livestock husbandry changed over time. Domestic livestock continued to play a vital role in the functioning of Montreal, Toronto, and Winnipeg in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Industrial development and urban growth, however, caused livestock husbandry practices and the composition of animals in these cities to change. When examined by individual species and cities, there are noticeable differences in the histories of specific livestock animals in urban environments. Some experienced steady decline, some saw sharp decline, and some actually grew in population toward the end of the nineteenth century.

Urban dairy cows saw gradual decline in Montreal, but more rapid decline in both Toronto and Winnipeg. Between 1861 and 1911, the population of dairy cows in Montreal declined each year at an average of 30 per cent. In Toronto, the population increased from 1,102 to 1,237 cows between 1861 and 1871 and then declined by an average of 53 per cent until there were just 29 cows counted in 1911. In Winnipeg, where the census data is limited to just three years, the decline appears sharper with a steep drop of nearly 87 per cent between 1901 and 1911. This may have been the result of amendments to the city’s public health bylaw at the end of the nineteenth century, which radically limited the ability to operate urban dairies by setting restrictions on the number of animals that could be kept on a given property. Winnipeg had a substantial number of milch cows when compared to the much larger urban centres of Montreal and Toronto. This may have been the result of the city’s proximity to a rapidly growing agricultural frontier and the spread of domestic livestock husbandry across the prairie region alongside the massive influx of settler colonists in the early twentieth century. Amendments to the public health bylaw at the end of the nineteenth century, however, may have brought Winnipeg’s urban environment into closer alignment with Montreal and Toronto. Dairy cows served growing urban markets by providing the daily supply of milk. They were significant capital investments that required substantial care and attention. As such, the owners of urban dairy cows, especially small entrepreneurs, tended to vigorously defend their business interests against regulations that sought to curtail the keeping of cows within city limits. Until the late decades of the nineteenth century, grocers, innkeepers, and other small entrepreneurs kept cows to provide milk to their customers. For families with enough money to invest in a cow, women and children were typically responsible for caring for cows, including milking.[10] The number of dairy cows in Canadian cities also went into decline as dairying transformed into an industrial enterprise. This was accompanied by a shift in the gendered division of labour in livestock husbandry as men assumed primary responsibility for milking and caring for cows.[11] Small dairies became the subject of public health and nuisance complaints and investigations, especially toward the end of the nineteenth century as municipal public health authorities began to regulate the milk supply for bovine tuberculosis and other health risks.[12] By the turn of the century, keeping large livestock in increasingly crowded cities with limited available pasturage and high costs for fodder made the prospects of maintaining urban dairy cows untenable for most ordinary Canadian urban dwellers. Instead, larger industrial dairies operating in the immediate hinterlands of Montreal, Toronto, and Winnipeg and connected by railways came to replace urban dairies.

The cases of pigs and sheep in Canadians cities show unequivocal decline before the end of the nineteenth century. The populations of both species plummeted in Montreal, Toronto, and Winnipeg. Sheep were the least populous of the large domestic ungulates found in Canadian cities in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. They also were largely absent from municipal regulations concerning animal nuisances. They were rarely cited as causes of pollution, trespass, or other hazards. Montreal had the largest urban sheep herd at 414 animals in 1871, but that population rapidly vanished from the census. By 1911, enumerators found just 1 sheep in Toronto and none in Montreal and Winnipeg. Sheep were not ideal urban livestock animals. They could be used to supply mutton, but were more likely kept for wool. The commercial viability of an urban sheep herd was limited by available pasturage. They were also prey for growing populations of domestic and feral dogs, which became increasingly common in urban North America in the nineteenth century. For an individual family, sheep had little utility in supplementing household economies when compared to a pig, cow, or chicken. The case of sheep in nineteenth-century Canadian cities offers an example of a decline of one urban livestock species in the absence of regulatory prohibitions or public protest against their presence. Pigs, on the other hand, drew much more public attention and ire.

Figure 7

Rapid human population growth in Montreal, Toronto, and Winnipeg toward the end of the nineteenth century and the first decade of the twentieth century

Figure 8

Number of large domestic ungulates (horses, milch cows, pigs, sheep) for every 100 humans, 1871–1911

In nineteenth-century Canadian cities, pigs were useful animals, especially for working-class families, but to other urban dwellers they were troublesome. Pigs are independent foragers, and in the context of rapidly growing urban environments, they found plenty of food. The heaps of waste (especially food waste) that accumulated in cities prior to the development of extensive solid waste management systems created an ecological niche where free-roaming pigs thrived. Indeed, as Catherine McNeur found in the case of nineteenth-century New York City, “Not only were there more people around to own animals, but those people were also creating more garbage that, left uncollected on the streets, fed a burgeoning, free-roaming animal population.” This was an experience common to many rapidly growing North American cities. For working-class families, an animal that could feed itself without much need for tending proved advantageous and indeed necessary, given paltry wages. Urban free-range livestock husbandry served their needs quite well. Just one or two pigs could provide significant benefits for a household economy, as they could be sold for slaughter or used to feed hungry families. However, free-roaming pigs were a problem across urban North America and, in the cases of nineteenth-century Montreal, Toronto, and New York City, they became the subject of municipal campaigns to prohibit the keeping of pigs in the city. As the result of a mix of ethnic and class prejudices, and cultural perceptions of cleanliness, pigs in many Canadian and US cities were subject to some of the first restrictive regulations against urban livestock husbandry and subsequent prohibitions. While ethnic and class prejudices informed campaigns to remove urban pigs from some cities, historians must also consider the material factors involved in the presence of such animals in urban environments. The growing density of cities, the proclivity of pigs to contribute to pollution (via their waste and rooting behaviours), and the limited availability of pasturage also made the raising of pigs in cities less practical. In the cases of Montreal, Toronto, and Winnipeg, the populations of pigs in these cities collapsed in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Montreal established an outright prohibition on the keeping of pigs by the mid-1870s, while municipal authorities in Toronto and Winnipeg merely restricted the numbers of pigs that could be kept in the city. In Montreal, the census documented a peak urban pig population of 2,644 in 1861, a number that would decline by more than 93 per cent by 1881. In Toronto, the pig population similarly fell, dropping by 88 per cent between 1861 and 1881. And in Winnipeg the decline of the pig was even sharper, falling more than 95 per cent from a population of 225 in 1901 to just 10 in 1911. By the twentieth century, the pig, more so than any other urban animal in Canada, was driven out of cities.[13]

The loss of pigs, however, did not bring an end to livestock husbandry practices among Canada’s urban working class. As the pig went into decline, chickens continued to serve as sources of food and supplementary income for families in Canadian cities. In fact, they were the most populous urban livestock animal counted in the census between 1891 and 1911. Today, many cities across North America are experimenting with the reintroduction of urban chicken raising, generating new questions and concerns about regulation and public health.[14] For urban families in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, chickens offered eggs and meat that could provide subsistence or be sold. They also required less space and forage than larger animals, such as pigs. According to census figures, Toronto had the largest urban chicken population in Canada. Between 1891 and 1911, the chicken population of Toronto grew from 16,714 to 21,226, an increase of 21 per cent. By 1911, there were 5.6 chickens for every hundred humans in Toronto. Montreal and Winnipeg, on the other hand, saw gradual decline in their urban chicken populations after 1901.

In all three cities the population of horses grew in the latter decades of the nineteenth century. In Montreal and Toronto, the horse population grew and peaked in 1891, according to census data. In 1881, the census recorded 4,479 horses in Montreal, and that number grew to 6,751 by 1891. Toronto saw the largest recorded urban horse population in Canada in 1891 with 7,401 horses. The horse population in both cities declined thereafter. Concurrent evidence from city directory listings for livery stables shows a similar trend. For example, in Toronto the listings for livery stables increased to a peak in 1894 with sixty-two stables and declined to thirty-seven by 1900 (figure 9). In Winnipeg, the horse population grew between the 1891 and 1901 censuses before starting to decline. These figures correspond with the work of other historians who found that as cities in the United States industrialized and grew rapidly toward the end of the nineteenth century, the urban horse population also grew. As McShane and Tarr wrote, “The nineteenth-century city represented the climax of human exploitation of horse power.” Similarly, Ann Norton Greene contends that “horses were ubiquitous in nineteenth-century society,” and “particularly dense in and around the cities.”[15] Horses were the primary mode of intra-urban transportation in North American cities, critical for urban commuter street railway systems and the movement of goods via ordinary hauling and trucking.[16] They were also used in factories as sources of power to operate machinery. The introduction of electrified street railways and steam engines for factory machinery contributed to the decline of the urban horse population in North America, and the subsequent popularization of the automobile finally made the horse obsolete as a tool of urban transport.

Census data for Montreal, Toronto, and Winnipeg reveal that these three cities developed similar compositions of domestic livestock for food and labour over the course of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The greatest differences can be observed in Winnipeg, where urban growth occurred much later and more rapidly than the larger cities of central Canada. However, by the turn of the century, the species compositions of all three cities shared common characteristics. Urban growth did not result in the total extirpation of livestock from cities in the years between 1861 and 1911. The records show that the composition of species of domestic livestock animals in cities changed during these years as practices of urban livestock husbandry were transformed by a number of different factors, including technological innovations, public health concerns, reduced availability of pasturage, crowding, and changing market conditions. By 1911, urban dwellers in Canada continued to raise domestic livestock animals. While fewer people kept pigs, sheep, and cows by the beginning of the twentieth century, chickens and horses continued to have a place in cities, albeit one that diminished with time. In environments then with large numbers of people and similar assemblages of domestic livestock, municipal governments encountered common environmental challenges and concerns about livestock as urban nuisances. The regulation of animal nuisances in Montreal, Toronto, and Winnipeg took on similar characteristics as responses to these common environmental challenges.

Regulating Animal Nuisances

In the nineteenth century, domestic livestock animals in Canadian cities produced environmental challenges for municipal authorities that came to be known generally as nuisances. They ran about unattended, paying no mind to the boundaries of private property. They roamed, foraged, and frolicked without much care for the safety of people or the movement of street traffic. They occasionally stampeded and trampled human pedestrians. They urinated and defecated where they saw fit to such an extent that the smell of cities in the nineteenth century was unmistakable. And when they died, their corpses piled up in the streets sometimes for days. Peter Atkins argues, in the case of nineteenth-century London, that as authorities came to view animals as nuisances, they “were less likely to be thought to have legitimacy as urban dwellers and removing them and their associated nuisances was a way of guiding and disciplining the behaviour of their keepers and controlling a hazardous environment.”[17] While animal nuisance regulations certainly attempted to constrain urban livestock husbandry in Canada, they did not immediately set out to remove animals from cities. Instead, municipal authorities formed these regulations in response to a series of environmental challenges that were characteristic of urbanization. All three cities in this study experienced similar environmental challenges and adopted a common set of regulatory strategies.

Figure 9

Number of Toronto livery stables listed in city directories, 1870–1900

Municipal authorities in Montreal, Toronto, and Winnipeg came to face the same environmental challenges associated with their common assemblages of livestock animals: trespass, physical hazards and obstructions, and environmental pollution. In surveying the regulation of livestock in these cities, it is clear that addressing these matters occupied the attention of municipal governments early in their histories. Regulations governing livestock animals in Canadian cities were some of the earliest bylaws in Montreal, Toronto, and Winnipeg. And in Montreal and Toronto, the regulation of livestock predated municipal incorporation. These regulations were, for the most part, broadly similar and in some instances identical.

Colonial (and later provincial) governments specifically empowered municipalities to regulate livestock. This was an acknowledgement of the unique conditions of urban livestock husbandry. In Lower Canada, the legislature passed an act to incorporate Montreal in 1832, granting the new common council all prior authority and responsibilities of the former justices of the peace for the city. This included power to regulate streets, markets, and “all things which may in any way regard the improvement, cleanliness and convenience of the said City.” With these broad powers, the municipal government had the authority to regulate practices of livestock husbandry and the sale and slaughter of animals within the boundaries of the city.[18] The act of incorporation of the City of Toronto in 1834 similarly included general provisions for the regulation of public health, but it also explicitly included the power to regulate animals. It granted the common council for the City of Toronto the power “to regulate or restrain Cattle, Horses, Sheep, Goats, Swine and other animals, Geese or other poultry, from running at large within the limits of the said City of Liberties thereof; and to prevent and regulate the running at large of Dogs.”[19] Such powers had become common by the 1870s, when the province of Manitoba passed the City Charter for Winnipeg in 1873. As in Toronto, the city council for Winnipeg had the power to create bylaws “for restraining or regulating the running at large of any animals.” The City Charter also delineated further specific powers, including the power to regulate and license livery stables, manage public markets and the sale of live and slaughtered animals, and “prevent … cruelty to animals.” Finally, broad public health powers also led to the regulation of the keeping of livestock animals in the city.[20]

A complicated array of urban actors representing different interests placed pressure on municipal governments to regulate animal nuisances. Both the owners of land and the owners of domestic animals took it upon themselves to pressure local governments to regulate animals in cities. For landowners, trespass and property damage was a primary concern. The protection of their livestock and accessibility of pasturage were the main concerns of animal owners. Many working-class city dwellers insisted on the continued right to keep livestock and resisted bylaws restricting such practices. They were joined by businesses that relied upon domestic livestock animals, especially dairies and butchers. In the latter decades of the nineteenth century, urban sanitary reformers called upon city councils to address public health risks associated with animals as sources of environmental pollution. Finally, animal welfare organizations, including the Canadian Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, the Toronto Humane Society, and the Winnipeg Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Women, Children and Animals, also played a role in the regulation of animals in these Canadian cities. However, as Darcy Ingram’s research shows, their efforts were directed mainly at federal anti-cruelty legislation rather than municipal bylaws. These organizations came to play a role in the enforcement of anti-cruelty regulations.[21]

Controlling Animal Movement

The growth of dense settlements of people and domestic livestock animals produced conditions for conflict over trespass. Free-roaming, autonomous horses, cattle, and pigs wandered onto private property, obstructed traffic, and occasionally attacked pedestrians. The movement of livestock was one of the earliest common animal nuisance challenges for municipal authorities in Montreal, Toronto, and Winnipeg. Municipal governments imposed restrictions on animal movement through pound and trespass bylaws in response to the conflicts that arose as a consequence of the free movement of livestock. Pound bylaws imposed limits on free-range livestock husbandry and established rules to determine compensation for damaged property, including damage to animals and other forms of property. Initially, these bylaws were broad and permissive, usually prohibiting the free movement of animals on properly fenced private property and public roadways while allowing specific species to continue to move freely elsewhere within the city limits. Livestock often used unoccupied city lots as informal commons for grazing. Before the end of the nineteenth century, however, all three municipalities eliminated free-roaming animals from the city centre, moving livestock husbandry to the suburban fringe.

In Lower Canada, the legislature and the justices of the peace for the District of Montreal first empowered police in Montreal to enforce limits on livestock husbandry and the movement of animals in 1810. The Rules and Regulations of the Police for the City and Suburbs of Montreal established many of the primary areas of animal regulation that would become common in other Canadian cities in the nineteenth century. According to Article 12 of these rules, horses, pigs, and goats could not forage freely in the streets, squares, or lanes within the city limits. The regulations empowered anyone to seize such animals and hold them until the owners paid a fine. Other urban livestock, such as cattle and sheep, were still permitted to graze unattended. A free-roaming pig, on the other hand, was considered so troublesome that the regulations permitted “any person to kill such hog,” if it could not be captured. If the owner of such a pig refused to pay a fine or failed to claim the animal’s body, “the person killing the said hog may retain it for his own use.” The specific targeting of pigs in such regulations was not unique to Montreal.[22]

After the incorporation of the City of Montreal in 1832, the municipal government began to enclose available common pasturage and eventually outlawed all species of domestic animals from roaming unattended. In 1840, the council passed Bylaw 4, which established a city pound at Place Viger on Saint-Denis Street. It created a position of city pound-keeper and granted that person the power to impound “all horses, horned cattle, sheep, goats and hogs found straying on or damaging the property of any person or straying on the beaches, highways, or public grounds within the City limits.” This restriction focused specifically on animals that trespassed on private property and some public property. Unoccupied lots, however, remained open as pasturage.[23]

In 1870 as both the human and domestic livestock populations of the city grew and the potential for trespass and property conflict increased, Montreal’s city council expanded its system of pounds by establishing several pound facilities and empowering all city police to “act as keepers of the said pounds respectively.”[24] Amendments to the pound bylaw established pounds at the Cattle Market in St. James Ward and at St. Gabriel Market in St. Ann’s Ward. It also created small pounds at every police station. “It shall be the duty of all constables of the police force of the said City,” read Bylaw 43, “whenever they see or meet any horse, cattle, swine, hog, sheep, or goat, running at large in contravention of this by-law, or whenever their attention is directed by any citizen to any such animal running at large, as aforesaid, to immediately drive the same to the nearest pound.” Montreal was the only city in Canada in the nineteenth century to empower its police force to also serve as pound-keepers. Enlisting the city police in the management of domestic animals in this manner was extraordinary, but it may have been a reflection of the growing complexity of managing Montreal’s urban environment, a much more populous city than Toronto and Winnipeg by 1870. It was also a result of the simultaneous aggressive public health campaign against the keeping of pigs. This new bylaw all but ended the possibility of legally continuing the practice of free-range livestock husbandry within the boundaries of Montreal.[25]

In Toronto, conditions were much the same. Colonial administrators in Upper Canada understood the need to restrain free-range livestock husbandry in dense settlements of humans. By placing constraints on the practice of keeping animals within towns and villages, colonial authorities hoped to control the practice of free-range livestock husbandry in the colony, which had “been found occasionally inconvenient and detrimental,” according to early Upper Canadian law. In 1794, the colonial assembly of Upper Canada passed “An act to restrain the custom of permitting horned cattle, horses, sheep, and swine, to run at large,” which granted local inhabitants in the colony the power to establish limits on free-range livestock husbandry through “their annual town meetings.” The legislation specifically targeted animals “found running at large in any town, township, [or] reputed township.” Upper Canadian law more specifically targeted town-dwelling pigs in 1803 when the assembly passed an amendment to the 1794 statute that forbade “any person or persons residing in the several towns of York, Niagara, Queenston, Amherstburgh, Sandwich, Kingston, or New Johnstown, to have any swine going at large in the said towns.” These early statutes illustrate the extent to which the free movement of livestock within towns and villages in the colony caused similar concerns in Upper Canada and Lower Canada.[26]

Not long after the incorporation of the City of Toronto, the council passed its first bylaw constraining the movement of livestock animals in 1834. Bylaw 4, “An Act concerning Nuisances and the good Government of the City,” set constraints on the practice of free-range livestock husbandry in the city. Similar to earlier statutes that restricted free-running livestock animals within the town of York, Section III of the first nuisance bylaw for the City of Toronto specifically targeted pigs, stipulating that “no swine shall be permitted to run or be at large in any of the streets or any of the sidewalks of this city.” The bylaw imposed fines for such offences, and the council appointed a man named Isaac White as the first pound-keeper for Toronto. The bylaw, however, was not well enforced, according to a number of city residents who complained to the council of swine running at large throughout the city. In August 1835, they petitioned the council to provide better enforcement of the nuisance bylaw. Such petitions and endorsements from particular aldermen often led to expanded regulation of animals in the city.[27]

After receiving further petitions and complaints about other free-roaming creatures in the city, including horses and horned cattle, the Toronto city council expanded its regulation of livestock movement with its first pound bylaw in October 1837. This bylaw applied to a wide range of animals, including horses, oxen, sheep, and pigs, prohibiting such animals from running at large anywhere within the city limits. It specifically protected property owners who enclosed their lots with properly constructed fencing, a requirement similar to that in Montreal. While the first pound bylaw prohibited certain animals from roaming unattended in Toronto, cattle were excluded from this prohibition. The council still permitted the free-range grazing of cattle in Toronto outside of private property boundaries and public streets. Cattle could graze on unoccupied lots and other spaces in Toronto. In 1840, however, the city council further restricted this practice, gradually shrinking the permissible common pasturage for cattle. The bylaw granted the pound-keeper the authority to impound any cow found running at large between Peter Street and Berkeley Street. In 1845, those boundaries expanded east to Parliament Street.[28]

Legal free-range livestock husbandry came to an end for cattle-owners in Toronto in 1858 when the council amended the pound bylaw. Cattle could no longer roam within the city limits “unless the same are being driven from or to pasture by their owners.” Again, the by-law limited the use of cattle in the city, but it did not prohibit the presence of such animals. After 1876, however, it became more difficult to raise cattle in Toronto. Amendments to the pound bylaw eliminated all free-range grazing, prohibiting “horses, cows, cattle, goats, sheep, swine or geese to run at large within the limits of the said City.” As such, cattle owners had to make use of pasturage outside of the city boundaries or rely entirely upon fodder to feed their animals.[29]

Although much smaller in size and population, Winnipeg followed a similar course to that of Montreal and Toronto as it too encountered conflicts over free-roaming animals in the city. In June 1874, within a year after incorporation, the city council in Winnipeg passed a pound bylaw to establish a public pound, appoint a city pound-keeper, and regulate the movement of livestock animals in the city. Initially, the bylaw forbade the free-running of horses, bulls, and swine within the limits of the city. It also defined penalties for any animal that strayed onto private property. As in the case of Toronto, the city council in Winnipeg still permitted cattle to graze unrestricted on unoccupied lots. This lasted until 1880 when the council began to introduce limits on this practice. After receiving some complaints about cows straying onto private property in the night, the council amended the pound bylaw to establish a curfew on cattle, prohibiting evening grazing between 9 p.m. and 5 a.m. In 1885, further amendments established a pound limit, a defined area in the centre of the city where no species of domestic animal could run at large. Cattle, however, could still graze outside of the pound limit on unoccupied lots. While the pound limits grew over the remainder of the nineteenth century, by 1900 the city still permitted free-range livestock husbandry for cattle outside of those limits. By the end of the nineteenth century, Winnipeg had five public pounds administered by five different pound-keepers.[30]

Of course, bylaws, pounds, pound-keepers, and police did not rid the streets of roaming animals. The regulation of livestock in nineteenth-century cities was often more aspirational than actual. Livestock animals continued to stray onto private and public property, cause damages, obstruct traffic, and occasionally attack people throughout the nineteenth century. Complaints about free-roaming animals regularly appeared in local newspapers and municipal correspondence. For instance, in June 1870, the Montreal Herald reported, “Two fat oxen were found at large in Craig Street on Monday night, which Constable Beauchamp hurried off to the pound.”[31] In 1872, the Toronto Mail reported,

The hopes of relief which were entertained by those of our citizens who have suffered from the nocturnal visits of wandering pigs and cows do not seem yet near realisation. Complaints are common of grubbed up floral treasures and grass plots, wherever neck of cow can reach over or snout of pig rummage under the railings of gardens. Given the sturdy persistency of the domestic hog, acted upon by the cravings of never-to-be-satisfied porcine stomach, and anything within reach, short of cast-iron, has a bad chance of surviving. Our sidewalks too are in a disgracefully unpleasant condition as a consequence of these perambulations.[32]

Pigs similarly bothered the editors of the Daily Free Press in Winnipeg, who complained in 1874, “Pigs continue to roam the streets and explore gutters, utterly regardless of the poundkeeper.”[33] In September 1883, Thomas Mooney, the city pound-keeper for Winnipeg reported impounding thirty-three cows, three horses, and a pig.[34]

The persistence of free-roaming domestic livestock in cities is best illustrated in the case of Montreal where police were responsible for capturing stray animals since 1870. Police in Montreal regularly impounded horses, cows, pigs, goats, and sheep throughout the nineteenth century. Annual police reports of impounded animals reveal the degree to which the urban environment was filled with the autonomous perambulations of domestic livestock. The police reported capturing hundreds of animals each year, with a peak of more than seven hundred found in 1892. According to these reports, horses were the most common animals police impounded in nineteenth-century Montreal (figure 10).

Free-roaming livestock had become such a common characteristic of urban environments in Canada that municipal governments established increasingly elaborate and restrictive systems of public pounds in order to manage property conflicts between the owners of livestock animals and the owners of stationary forms of property. Pound bylaws set out rules for determining compensation when animals were found to have wandered onto private property and caused damage or when physical property was found to have harmed animals. The autonomous movements of livestock and the competing property interests of urban residents required municipal governments to intervene in order to ensure the protection of property rights while maintaining (and attempting to control) the place of livestock in the urban environment.

Animals as Pollution and Public Health Risks

Over the course of the nineteenth century, the presence of domestic livestock in cities aroused concerns about the role of animals as sources of environmental pollution and risks to human health. The dense and rapid human population growth in Montreal, Toronto, and Winnipeg resulted in environmental problems found in cities throughout urban North America. In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, water contamination, solid waste accumulation, sewage, and air pollution plagued municipalities in both Canada and the United States. Moreover, North American cities suffered periodic epidemics of devastating crowd diseases. Montreal, Toronto, and Winnipeg succumbed to several such outbreaks as their populations grew. Domestic livestock animals were thought to contribute to these problems, and they became the objects of concern for sanitary reformers.

Anxieties concerning livestock animals as sources of urban pollution were driven by dominant notions of the dissemination of disease associated with the miasmatic theory, the belief that foul-smelling air and dirty environments produced illness. Epidemics of smallpox, cholera, typhoid fever, typhus, rabies, and tuberculosis brought increased attention to urban animals in the nineteenth century. The public health responses to these epidemics often focused on a general concern over decaying organic matter and foul-smelling air or miasma. Public health and sanitary reformers pointed to livestock animals as one of the primary sources of such contamination. As a result, municipal authorities focused increasing regulatory attention on the bodies and excrement of livestock in cities and towns.

Municipal governments in Montreal, Toronto, and Winnipeg developed similar regulations over the course of the nineteenth century in an effort to mitigate potential adverse health effects associated with animal bodies and excrement. They focused mainly on animals as sources of miasma, attempting to address concerns over foul-smelling air, ventilation, drainage, and the contamination of water. Ethnic and class perceptions also shaped public health policies toward domestic livestock animals in cities. The perceived value of particular species and the economic uses and behaviours of certain animals figured in the development of nuisance, public health, and other bylaws.

The earliest nuisance bylaws were the first to establish municipal rules governing the practice of keeping animals in cities in order to guard against public health risks and sources of environmental pollution. The 1810 Rules and Regulations of the Police for the City and Suburbs of Montreal laid out some of the earliest efforts to control the bodies and excrement of animals in the city. Article 7 set out the guidelines for the disposal of “dung, rubbish, or filth of any kind,” forbidding the dumping of such waste in local rivers, streets, and public squares. Any such waste had to be removed from the streets in closed carts.[35] Article 10 set out guidelines for the disposal of animal carcasses, a common sight in nineteenth-century cities. Dead animal bodies could be an obstruction to traffic and an environmental and public health hazard. Sanitary reformers certainly viewed animal carcasses as primary sources of miasma. As such, cities regulated the disposal of animal bodies. In Montreal, the 1810 regulations specifically stipulated, “No dead dogs, cats or other animals whatsoever, shall be left above ground, in any part of the city or suburbs, nor thrown into the Great or Little River, but the same shall be buried, without the city, at least three feet under ground, under the penalty of forty shillings.”[36]

Even though city regulations required individuals to remove and bury animal carcasses, many thousands of animal bodies were left in the streets each year. A September 1874 note in the Montreal Daily Witness that “a dead horse lies off Mill street in the common, in rear of Forfar street,” was one of regular complaints found in city newspapers in nineteenth-century Canada.[37] The Montreal Herald similarly complained of animal carcasses on city streets. In one instance, it sarcastically reported on “The Reign of Cats and Dogs” in Montreal, where “more than a dozen of cats and dogs are reported as lying about the streets. Where is our Canadian enterprise? Dog skin gloves command a good price. It is a sad waste of the raw material.”[38] Animal carcasses were just one of the common environmental problems associated with domestic animals in urban environments.

Figure 10

Animals impounded by Montreal Police, 1880–1893

One of the duties of the Montreal police was the removal and disposal of unclaimed animal bodies. According to statistics in the annual reports of the chief of police for the City of Montreal, the police removed hundreds of bodies each year (figure 11). Prior to municipal campaigns to euthanize stray animals and license pets, dogs and cats dominated these figures. Horses were the next most common dead animal found in the streets of late nineteenth-century Montreal. As the horse population grew in the 1890s, so too did the number of abandoned horse carcasses, peaking in 1892 at 198. The police stopped reporting figures on the specific species of dead animals found in the streets in 1893, but annual reports by 1900 but still included general statistics reporting 297 dead animals found.

Montreal’s public markets and the sale and provision of animals as food (both live and slaughtered) came under the 1810 police regulations as well. These regulations established oversight of market conditions for trade of food in the city, guarding against adulteration and other unfair practices. They also ostensibly oversaw the health and safety of the city’s food supply, granting a market clerk the power to inspect the quality of meats and fish, govern the cleanliness of market stalls, and restrict the sale of live animals to particular conditions and places. For instance, in 1810, live cattle, horses, and pigs could be sold only at specific markets in areas adjacent to market buildings. Similarly, these regulations governed the work of butchers, prohibiting the slaughter of live animals outside of regulated facilities. The waste materials of slaughter were also controlled, preventing the dumping of “the belly or guts of any animal” in the streets or local rivers.[39]

Building again upon the 1810 regulations for the Montreal police, the council for the City of Montreal passed a nuisance bylaw in 1841 that laid out basic health requirements for keeping animals and managing waste associated with animals in the city. Section 8 of this bylaw required “that any person or persons who shall keep any swine, dogs, foxes or any other such animals on their premises in the said City shall maintain the houses, buildings or pens in which the same shall be kept in such a clean state that neighbours and passengers may not be incommodated by the smell therefrom.” This would become a common standard of health for the keeping of domestic livestock in nineteenth-century Canadian cities, including Toronto and Winnipeg. Residents were also required to bury any dead animals and they were not permitted to dispose of such animals in any local body of water, including the St. Lawrence River, similar to the 1810 regulations. Finally, the bylaw prohibited the storage of waste products associated with livestock, including manure, offal, “or any other putrid or unwholesome substances.” These were somewhat basic regulations, but they clearly focused on sources of miasma, decaying organic material.[40]

In Toronto, the city government first managed the potential negative health effects of urban animals through its health bylaw, which the council passed in 1834. Four of the fourteen sections of Toronto’s first Board of Health bylaw focused on the regulation of livestock animals and animal by-products. Passed by the council on 9 June 1834, Toronto’s eighth bylaw established a Board of Health with the power to oversee animal bodies. Dead animals and offal were of particular concern as nuisances and threats to public health. This bylaw required that butchers, “after killing any Beeves, Calves, Sheep, Hogs or other Cattle shall destroy the offals, Garbage and other offensive and useless parts thereof or convey the same into some place where the same shall not be injurious or offensive to the Inhabitants.” Additionally, the bylaw stipulated that Toronto residents shall not “cast or leave exposed the dead Carcass of any Horse, Cow, Hog, Dog or other Animal in any Street, Lane, Alley, Yard, or Lot.” These early public health bylaws directly addressed perceived health risks associated with deceased domestic animals and their bodies, whether those butchered for human consumption or those that fell dead in the streets. Of course, residents regularly ignored these rules throughout the nineteenth century. One needed only to look at the Don River in the 1880s, where there were “dead carcasses which are seen daily floating in the sluggish stream,” according to one newspaper description.[41]

Similarly, the first public health bylaw in Winnipeg provided early rudimentary regulations governing animal bodies and excrement as potential health risks for humans. In May 1874, the city council passed Bylaw 12, “A by-law relating to the Public Health,” half of which focused on rules on the interactions of human and animal bodies in the urban environment. For instance, it included the city’s earliest regulations of the food supply, outlawing the sale of “any tainted damaged or unwholesome fish, meat, fruit, vegetable, or any article of food of any kind whatsoever.” Water carters were specifically forbidden to sell any water drawn from any source used as “a watering place by cattle, horses, or other animals, and which by reason of such use, or from any other causes, has become foul or impure.” And, as in Montreal and Toronto, the first public health bylaw in Winnipeg governed the removal and disposal of animal carcasses in the city.[42]

In the latter decades of the nineteenth century, municipal governments in Canada began to use public health arguments to severely curtail livestock husbandry in cities and impose limited bans on the keeping of animals. They did so, often in response to reports of high rates of mortality and the outbreak of epidemic diseases, including cholera, smallpox, typhoid fever, typhus, and tuberculosis. The emergence of a sanitary reform movement in Canada and the United States raised concerns about livestock animals as environmental health nuisances and sources of such diseases. According Martin Melosi, “Sanitarians spread the word about environmental sanitation as essential to fighting epidemic disease.”[43] As Linda Nash has shown, the emergence of germ theory in the late nineteenth century did not replace older environmentalist understandings of disease and health. Instead, “nineteenth-century medicine was intellectually capacious, and most physicians had no difficulty mixing germ theories with long-standing environmentalist beliefs.”[44] As such, sanitary reformers targeted the smells associated with animal bodies and excrement as sources of harmful environmental pollution and potential causes of epidemic diseases.[45] In the late nineteenth century, sanitary reformers in Canadian cities sought to impose new restrictions on the keeping of livestock as a means of cleansing urban environments to prevent the spread of epidemic diseases and reduce mortality. They were often influential in the development of new public health bylaws, occasionally taking direct roles on municipal health committees.

The Montreal Sanitary Association, for instance, led efforts in that city to regulate the keeping of livestock in order to mitigate environmental and public health hazards. This organization played a significant role in shaping policy of the city’s Health and Market Committee. In 1865, the Health and Market Committee presented a series of recommendations to the city council to address the regular occurrence of summer outbreaks of disease, particularly cholera. “In view of this threatened attack we are all culpable to the last degree if we do not use all our energies to ward off an epidemic of this fatal disease,” wrote the city’s two medical health officers, Drs. Girdwood and Rottot. They recommended a series of reforms to cleanse the city, some of which focused on livestock animals. They called for an expanded system of scavengers to remove, among other things, offal and manure from city streets. They also recommended the creation of public slaughterhouses, new requirements for cleaning butchers’ stalls at public markets, and new rules for the treatment of live animals at markets “that they be kept in a place sheltered from the sun, as the feverish condition brought on by the present treatment renders such animals unfit for food.”[46] By the 1860s, municipal health authorities in Montreal were clearly associating livestock animals with adverse health and environmental conditions. The owners of pigs often found themselves before the Recorder’s Court to face fines for violations of the nuisance bylaw. For instance, in September 1865, the Herald reported several cases of Griffintown residents charged with keeping “filthy pigsties” found to be “injurious to health as well as offensive to the eye.” The reporter also found that “most of the offenders sent their wives to answer to the charge, and these in most cases loudly pleaded their poverty. Their poverty—even if such stories were always true—the Recorder gave them to understand, was no excuse for dirt and filth, and as to the keeping of pig-sties within the city, the practice would soon be disallowed.”[47] As Bettina Bradbury’s research has shown, this case also illustrated the extent to which sanitary reformers targeted urban working-class residents (often women) in their campaigns to cleanse the city.[48]

Figure 11

Dead animals found by Montreal police, 1880–1893

In October 1868, the city council adopted the Health and Market Committee’s recommendation to prohibit the keeping of pigs in Montreal, resulting in a new bylaw later that year that excluded pigs from the central wards of the city, limiting such practices to the outskirts. Six years later, the council amended this bylaw to extend its application to all parts of the city, simply stating, “No person shall rear, keep or feed any pig within the limits of the City of Montreal.” Further restrictions came in 1876 when the city passed major reforms to the public health bylaw, outlawing the keeping of any “horse, cow, calf, pig, sheep, goat or fowl” within a house or tenement. These bylaws and amendments all but eliminated the keeping of livestock animals in the densest parts of Montreal by the mid-1870s (except for large livery stables for horses). In the years following these restrictions, the city’s medical officers of health and police were able to report increased enforcement of such regulations. “There were several cases of pigs kept within the city limits,” wrote Sub-Chief of Police E. Flynn in his 1875 report to the city council, “which we caused to be removed.” While there continued to be some resistance among working-class residents and butchers in the 1870s, eventually large livestock animals, including pigs and cows, became less common in Montreal.[49]

Sanitary reformers in Toronto similarly raised concerns about the keeping of livestock in the city, drawing links between animals, miasmas, and the threat of epidemic disease. In 1866, the Toronto Board of Health issued a public notice in which the board highlighted how recent bylaw amendments addressed the threat of cholera in the city. The city’s new public health bylaw granted expanded powers to the Board of Health to control how animals were kept on private dwellings, ensuring that “no cows or other cattle, swine or goats shall be kept in the City unless proper drains are connected with the sheds, stables or pens, as shall thoroughly carry off all liquid filth issuing therefrom so that it shall not in any way constitute a nuisance, or a danger to the public health.” Under the amendments in Bylaw 431, city council appointed two health inspectors with the power to investigate private residences to determine and evaluate the conditions of, among other things, stables and the proximity of animal dwellings to houses.[50] Quoting directly from Edwin Chadwick’s influential work on the sanitary conditions of London, the Board of Health notice instructed city residents that “from the uncleanness of person, dwelling or premises, or locality, combined with improper food and intemperate or irregular habits, arises the chief danger from Cholera or other epidemics; hence the importance of paying strict attention to sanitary precautions.” Part of the city’s sanitary precautions included the regulation of the “keeping of Cattle, Swine, &c,” and specifically the “cleansing of yards, and drainage of stables, cow sheds, &c.” Under Toronto’s expanding public health regime, livestock animals were directly regulated as sanitary threats to human health and vectors of disease. Yet these regulations still permitted city dwellers to keep cattle, horses, pigs, chickens, and other livestock on their properties.[51]

In Toronto, Edward Playter, a sanitary reform advocate and editor of the Sanitary Journal, described disease and environment as inextricably linked, drawing animals and decaying animal matter into his view of the health of cities:

It has been noticed that, without exception, a high general death-rate occurring in towns and cities indicates a foul condition of the atmosphere; whereas, sudden outbreaks of disease are usually referable to the water supply … Besides these normal constituents of the atmosphere a great number of substances find their way into it. The works and habitations of men however furnish the most important impurities. In addition to the solid particles from the soil, and the debris of vegetation and of dead animals which had lived in the air, and the numerous and varied substances arising from manufactories and workshops, there are the vapors and gases arising from the decomposition of organic matter, numerous living creatures, the contagiums of specific diseases, and, especially enclosed spaces as inhabited room, the products of respiration and exhalations from the human body.[52]

Just as in Montreal, livestock animals in Toronto were swept up in a wave of public health reforms aimed at cleansing the fouled air and waters in the name of stemming deadly epidemics.

In the mid-1870s, residents of Riverside complained about pollution of the Lower Don River from the Gooderham and Worts swill milk and cattle byre facilities at Ashbridge’s Bay marsh. The distillery company, like many others in North America, sold and reused swill wash from its whiskey operations to feed cattle to produce low-cost milk and beef. As Jennifer Bonnell has argued, the city council was unresponsive to the demands of the eastside neighbourhood associations that complained about the smells from the Gooderham and Worts byres. The editor of the Globe argued that every city must have an industrial district subject to such pollution. He asked readers, “Is it possible to have a great city without great smells?” It was not until the 1890s, after intervention from the Provincial Board of Health, that the city responded to the demands to clean up the marsh. It did not, however, prohibit the company from keeping cattle in this marginal industrial district of the city.[53]

In July 1882, closer to the densely settled neighbourhoods of central Toronto, residents of Bleecker Street complained to a local alderman about a cow byre owned by Henry O’Brien located just north of Carlton Street. According to a report in the World, Alderman John Kent argued that the byre “not only depreciated the value of the property in the vicinity but it was injurious to the health of persons living near by.” Similarly, “long-suffering citizens,” according to an editorial in the World, complained about cow byres located on the property of St. Joseph’s Convent. The editor’s arguments, however, appeared to focus more on aesthetics than health, as he complained that “the beautiful convent building and the ugly and foul-smelling cow-byre are certainly not in artistic harmony together.” The Committee on Markets and Health investigated the matter and recommended that the city amend the nuisance bylaw to set new restrictions on the keeping of cattle and pigs. It was more responsive to resident petitions in neighbourhoods closer to the city centre. On 7 August, the council passed bylaw 1231, amending the nuisance bylaw to prohibit the keeping of pigs anywhere in the City of Toronto and severely restrict the ability to keep cattle. Within the central city, a single cow could not be kept closer than forty feet from a dwelling. If a person kept two cows, the distance increased to eighty feet. If one wanted to keep more than two cows in the city, he required written consent from three-fourths of the residents within a 150-yard radius of the proposed byre or stable. This effectively outlawed the keeping of cattle in the most densely settled parts of the city. However, it conveniently excluded outlying neighbourhoods, including the cattle byres at Ashbridge’s Bay. While these amendments outright banned the keeping of pigs in Toronto, it left open some measures to continue to permit raising cows. For instance, section 5 of the by-law stated, “The above rules and regulations shall not be construed to prevent vacant lots in any part of the City being used as pasture land or as a paddock.”[54]

These regulatory changes provoked mixed reactions and eventual resistance. The new nuisance bylaw was met with satisfaction at the World, where the editor had covered the issue most extensively. He claimed that the new bylaw would effectively remove cow byres from the city centre, a vestige of the past, in his view:

In times past there may have been fair occasion, and even necessity, for cow-byres within the limits; but the necessity has now disappeared. During recent years a new system of milk supply for the city has been established, and it is now in complete and efficient operation. The era of dairy farms has come, and the railways centreing [sic] in Toronto bring in morning and evening ample supplies of fresh milk from all quarters. With this abundant supply of milk coming in fresh from the country, the last excuse for the toleration of cow-byres within the city has disappeared.[55]

While some saw the fresh delivery of milk from nearby country dairies as a modern solution to the continued presence of cows in the city, others acknowledged the continued use of local dairies and the need to accommodate livestock husbandry in Toronto. In fact, the city council had postponed a decision on this matter earlier in May on the grounds that it would impose a hardship on cattle owners prior to the winter season when they would typically sell or slaughter their animals. Numerous milk dealers and cow owners signed a petition to the Committee on Markets and Health pleading for the enforcement of the nuisance bylaw to be postponed for a year. The committee recommended that the bylaw be delayed to allow cow dealers to sell off their herds in the winter, and the city council obliged.[56]

The next year, Daniel McKnight attempted to challenge Bylaw 1231 in provincial court on the grounds that the local nuisance bylaw in Toronto was an illegal interference with trade. While the court did not agree with McKnight’s broader argument regarding restraint on trade, it did find flaws with the bylaw and quashed part of it. In particular, Justice C.J. Wilson argued that the prohibition on the keeping of pigs in the city was ultra vires of provincial legislation. He wrote, “A general prohibition, therefore, against the keeping of pigs within the city, although the keeping of them is not pretended to be a nuisance, cannot be maintained.” The court held that the city could not generally prohibit the keepings of pigs, but could only set regulatory restrictions to prevent pigs from becoming a nuisance to others. It upheld the restrictions on cow byres because they specified particular rules for keeping cows in the city, but the section on pigs was “a total prohibition, nuisance or no nuisance.” As such, the court prevented the City of Toronto from entirely prohibiting the keeping of pigs and other domestic livestock animals in the nineteenth century.[57] In the 1890 amendments to the public health bylaw, the city restricted the keeping of any pigs, goats, or other horned cattle to enclosures no closer than seventy-five feet from a dwelling and twenty-five feet from a public highway, effectively outlawing the keeping of large livestock animals in all parts of Toronto except for the suburban margins.[58]

By the latter decades of the nineteenth century, Winnipeg faced similar environmental and health conditions concerning livestock animals and the threat of crowd diseases. While the municipal government did not attempt to introduce prohibitions on the keeping of any specific animals, it did introduce significant restrictions through amendments to its public health bylaw in 1899 in response to concerns over the spread of tuberculosis via the urban milk supply. Winnipeg approached the threat of tuberculosis in a manner similar to other municipalities in North America in the late nineteenth century. Its public health officials targeted the link between bovine tuberculosis and human health. Beginning in 1894, the city’s medical health officer, Maxwell S. Inglis, advocated for new bylaws regulating the milk supply and mandating tuberculin testing and the inspection of dairies within and beyond the city limits. Marion McKay has described the debate over bovine tuberculosis in the years prior to 1900 as a stalemate. Urban and rural cattle owners resisted the efforts of the Board of Health to mandate tuberculin testing and inspect premises without guarantees of compensation for the destruction of diseased animals.[59]

While dairy owners blocked the city’s early efforts to regulate milk, the new public health bylaw passed in May 1899 and set restrictions on the keeping of livestock, particularly cattle. The bylaw governed the rules for the disposal of manure on premises where animals were kept. For instance, properties with three or fewer “horses, cows or other animals are kept” were required to dispose of manure once a week, while properties with more than eight animals had to remove manure daily. Similar to the regulations in Toronto, the 1899 public health bylaw in Winnipeg established limits on the number of cattle that could legally reside on a property, gradually moving such animals to less dense parts of the city. For example, no more than two cows could reside on a property within a distance of one hundred feet of another building and only with “the consent in writing of all the persons so resident within one hundred feet of such stable or other building.” Cattle owners seeking to keep up to eight animals had to keep any stables at least three hundred feet from other buildings, relegating them to the outer fringes of the rapidly growing city. Cattle yards were also prohibited anywhere south of Henry Avenue and within twelve blocks of Main Street. Unlike Montreal and Toronto, however, the city council still permitted residents of Winnipeg to keep “swine, dogs, foxes or other animals” on their properties as long as the smell from such animals did not affect neighbours.[60]

Conclusion

By the end of the nineteenth century, the regulation of animal nuisances in Montreal, Toronto, and Winnipeg had become more restrictive, limiting urban livestock husbandry and precipitating changes in the populations of such animals. The populations of large food animals, including cattle and pigs, quickly vanished from census records while the populations of horses and chickens remained high in the first decade of the twentieth century. The similarities in the restrictive regulation of livestock husbandry in Canadian cities were responses to the common environmental changes that occurred as a result of rapid urbanization and human population growth. Crowding exacerbated problems of trespass, property conflict, environmental pollution, and the spread of epidemic diseases. As Montreal, Toronto, and Winnipeg each grew over the course of the nineteenth century, their urban environments became ecologically more alike and their responses to animal nuisances reflected this convergence.

Comparative studies in urban environmental history offer insight into the ecological processes of urbanization. The regulation of livestock is just one area of urban environmental policy where historians can examine the ecological transformations associated with urbanization in the nineteenth century. Cities across North America also confronted issues of air pollution, water contamination, solid waste accumulation, and numerous other environmental challenges associated with industrial urbanization. Examining how municipal authorities responded to these challenges across numerous jurisdictions helps further reveal the common characteristics of urban ecosystems.

Parties annexes

Biographical note

Sean Kheraj is associate professor of Canadian and environmental history in the Department of History at York University. He is the author of Inventing Stanley Park: An Environmental History, and he is the editor-in-chief of the Network in Canadian History and Environment.

Notes

-

[1]

Annual Report of the Chief of Police (Montreal: 1884), 19; “Detailed Statement of the Receipts and Expenditures on Account of the City of Toronto,” Appendix to City of Toronto Council Minutes, 1884; Acton Burrows to mayor of Winnipeg, 19 April 1883, City Council Correspondence, City of Winnipeg Archives (hereafter CWA).

-

[2]