Résumés

Abstract

Because few women of Chinese heritage came to Canada, Chinese migrant communities before 1950 are described as “bachelor societies.” Sojourners’ own ambition to return home with more wealth, the imposition of ever-increasing head taxes on migrants from China, the 1923 Chinese Exclusion Act, and deeply entrenched racism toward people of Chinese heritage meant that the vast majority were doomed to live their lives without the emotional, material, or domestic support or companionship provided by wives and children. They were de facto bachelors, if not bachelors in fact. New research, however, shows that since the 1910s young men of Chinese heritage carved out spaces for themselves in Toronto’s urban sexual culture, and young white women a space for themselves in Toronto’s Chinatown. During the first half of the twentieth century, many men of Chinese heritage enjoyed sex, companionship, love, and family life. Perhaps as many as a third were married to or lived common-law with women of white heritage, and many more frequently engaged in sexual and intimate relationships with sex workers they sometimes sought as long-term companions. The evidence presented here challenges the current perception that “Chinese bachelors” lived sexless, loveless lives. These relationships were not without controversy, of course, but many people within the community accepted them, and women of white heritage, including sex workers, were integrated into the community in diverse ways.

Résumé

Parce que peu de femmes d’origine chinoise sont venues au Canada, les communautés de migrants chinois d’avant 1950 sont qualifiées de « sociétés de célibataires ». L’ambition des migrants de s’enrichir avant de rentrer au pays, l’imposition de taxes d’entrée toujours plus élevées sur les migrants en provenance de Chine, la loi sur l’exclusion des Chinois de 1923 et le racisme profondément enraciné envers les personnes d’origine chinoise font que la grande majorité des migrants sont condamnés à vivre sans la compagnie ou le soutien affectif, matériel ou ménager d’épouses et d’enfants. Ils sont célibataires de fait, sinon célibataires en fait. De nouvelles recherches montrent toutefois qu’à partir des années 1910 des jeunes hommes d’origine chinoise se sont taillés une place dans la culture sexuelle urbaine de Toronto et des jeunes femmes blanches une place correspondante dans le quartier chinois de Toronto. Au cours de la première moitié du XXe siècle, de nombreux hommes d’origine chinoise ont connu le sexe, la camaraderie, l’amour et la vie de famille. Peut-être au moins un tiers d’entre eux sont mariés ou vivent en union libre avec des femmes d’origine européenne, et bien d’autres poursuivent fréquemment des relations sexuelles et intimes avec les travailleuse du sexe qu’ils cherchent parfois comme compagnons de longue durée. La preuve présentée ici remet en question la perception actuelle que ces « célibataires chinois » ont vécu une vie sans sexe ni amour. Ces relations n’étaient pas sans controverse, bien sûr, mais beaucoup de gens au sein de la communauté les ont acceptées, et les femmes blanches, y compris les travailleuse du sexe, ont été intégrées dans la communauté de diverses façons.

Corps de l’article

In 1919, Corporal H. Neeson from the small Ontario town of Campbellford and his wife Louisa of Norfolk, England, moved to the city of Toronto with their first child, Eileen.[1] Neeson and Louisa met while he was a member of the South African Constabulary and she was a nursing sister in the Boer War. Eileen’s early years were spent in South Africa, her mid-childhood years in Reading, England, and her teenage years in Toronto’s tony Avenue Road neighbourhood where she enjoyed the conventional privileges of upper-middle-class stature. Some time in 1923, however, Eileen’s life took a very unconventional turn. Chu Yat Bo passed through the neighbourhood selling wares from the Oriental Shoppe, a Yonge Street store where he was employed. When Bo, who Canadianized his name to Harry Chu (figure 1), arrived at the Neeson home, Major Neeson invited him inside. Neeson “had done a lot of travelling, and was interested in people and their stories.”[2] Eileen met Chu that day, and she was charmed. She recruited a girlfriend to accompany her on visits to Chu’s Yonge Street shop, but these chaperoned encounters soon gave way to secretly arranged lone dates. Over steaming cups of tea Harry and Eileen grew increasingly enamoured of each other.

Members of Chu’s kinship network became alarmed by the budding romance, and one day Harry was abruptly shipped home to Guangdong province, where he was pressured to enter an arranged marriage. After his wife gave birth to a son, Harry returned to Toronto alone, as was the practice and the fate of male migrants of Chinese heritage who travelled overseas for remunerative work. By the time Harry returned, Eileen had also married and had given birth to twins. Eileen’s marriage was not a happy one, and when she learned Harry was back in Toronto she resumed her visits. In 1932 or 1933 she left her Anglo-Canadian husband to establish a household with Harry. Eileen assumed she would retain custody of the children of her first marriage, but she was sadly mistaken. Men retained legal right of custody of children, and as a white woman who chose a Chinese lover, Eileen had virtually no chance of successfully challenging her husband’s claim.[3]

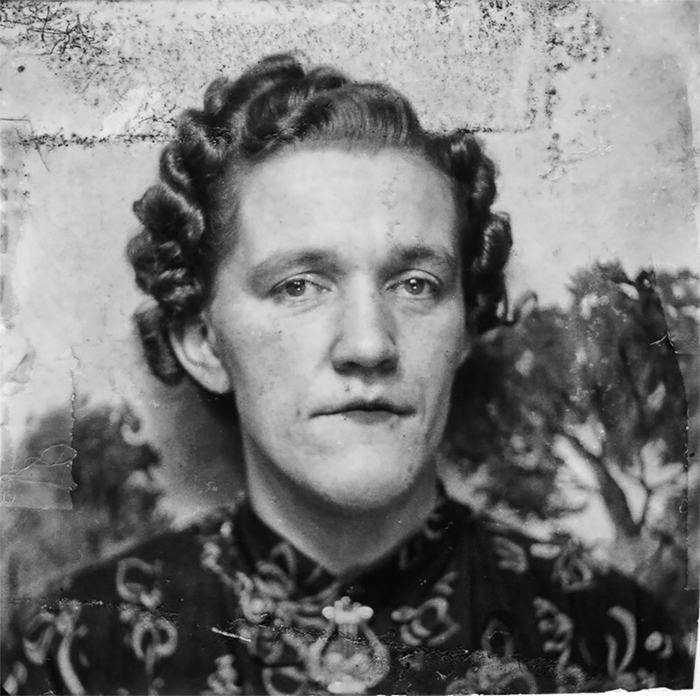

Figure 1

Chu Yat Bo / Harry Chu, Toronto, 1920s

Historians have long assumed that because of a preference for women of Chinese heritage or because of the intense racism to which migrants of Chinese heritage were subjected, interracial relationships such as these were anomalous.[4] This article shows that they were much more common than we thought. Whether or not they had wives in China, men developed a range of sexual and affective relationships with Canadian-born and immigrant women of non-Asian heritage. Eileen Neeson was an exception only in that she was upper middle class. In all other respects, she was one of a growing number of white women in a sexual and intimate relationship with a man of Chinese heritage. These relationships were not without controversy, but many people within the community accepted them, and women of white heritage, including sex workers, were integrated into the community in diverse ways.

This article maintains that the twin processes of racialization and heterosexualization—both structured by the imperatives of the Canadian settler colonial state—were felt experiences that affected the marriage market with as much force and in similar ways as they affected the labour market. The past two decades of scholarly work on emotions have pushed historians of migration and sexuality beyond the field’s primary focus on socioeconomic processes and their dynamics, and agency among the exploited, to include felt experience.[5] Historians treat agency as a process of rational calculation, but rational calculation and emotional drive are intricately interconnected.[6] Because emotions and discourses on emotions “are the results of processes of social and cultural construction based on socioeconomic frameworks,” paying attention to emotions expands approaches to relations of power. As Nicole Eustace points out, “Shifting patterns in who expresses which emotions, when, and to whom provide a key index of power in every society. Every expression of emotion constitutes social communication and political negotiation. Truly, the personal is political.”[7]

Writing the history of emotion from “the bottom up,” in this case from the perspective of people who shared intimacy across racial lines in the first half of the twentieth century, is challenging. In conducting this research I located photographs of such couples from the period under study and have interviewed their children, but their parents left behind no letters, diaries, novels, plays, or other first-hand accounts that could shed light on how they navigated their feelings, to borrow a phrase from William Reddy. Reddy, Peter Stearns, and Carol Z. Stearns have advanced the study of the history of emotions in such circumstances by proposing: (1) emotionology, the study of the collective emotional standards of a society, and (2) the study of emotional regimes, “the set of normative emotions and the official rituals, practices, and emotives that express and inculcate them; a necessary underpinning of any stable political regime.” Finally, Claire Langhamer reminds us that in the absence of direct sources, we can read against the grain of prescriptive and similar material.[8]

In the early twentieth century, the Canadian state was a eugenic state invested in building a white, Christian nation based on distinctly British political and cultural ideals, among them racial purity. For the average white Canadian, state and provincial policies were absorbed through educational materials that promoted a white Christian nation and depicted “others” as dangerous outsiders or simply ignored them. Stereotypes were reflected in and reinforced through journalistic constructions of the “yellow peril” and narratives of the sexual enslavement of white women by the Chinese, and popular cultural productions such as the Fu Manchu books, radio plays, movies, Hilda Glynn Howard’s 1921 novel The Writing on the Wall, Emily Murphy’s 1922 “exposé” The Black Candle, and J. S. Woodsworth’s Strangers within Our Gates. [9] Government policy was used in an attempt to rid the country of people of Chinese heritage through restrictive immigration policies. Racism seemed to ensure that without Chinese women present, those already inside the country were unable to reproduce.

Because few women of Chinese heritage came to Canada, Chinese migrant communities before 1950 are described as “bachelor societies.”[10] Sojourners’ own ambition to return home with more wealth, the imposition of ever-increasing head taxes on migrants from China, the 1923 Chinese Exclusion Act, and deeply entrenched racism toward people of Chinese heritage meant that the vast majority were doomed to live their lives without the emotional, material, or domestic support or companionship provided by wives and children. Like Harry Chu, many made the long journey back to Guangdong to marry and father children. They returned to Canada to continue working, with the expectation that they would send the bulk of their earnings to their wives. They were de facto bachelors, if not bachelors in fact.[11] Men’s implied celibacy serves as a poignant marker of how racism affected them at the most intimate level of existence.

The presumption of celibacy is based on the assumption that the only female partners available to men of Chinese heritage were women of Chinese heritage or sex workers paid to do the deed, and because sex workers are not often seen as legitimate subjects of history, their existence is written out of the story so fast you almost never know they were there.[12] Given the socially sanctioned and institutionally enforced racism of the time, it is perhaps not surprising that scholars would make this assumption. Research, however, shows that a significant number of men of Chinese heritage in Toronto, perhaps as many as a third, were married to or lived common-law with women of white heritage, and many more frequently engaged in sexual and intimate relationships with sex workers they sometimes sought as long-term companions.[13]

Such a finding confirms what historians of sexuality have long argued. Whenever we put sex at the centre of our historical vision, our understanding of the past changes. However, historians of sexuality often neglected non-white groups in studies of how urbanization and industrialization changed heterosocial cultures. Historians of Canada and the United States have shown that at the end of nineteenth and beginning of the twentieth century young men and women had more money and freedom, but cramped housing meant that budding adolescent heterosexuality shifted away from the family household and into the commercialized leisure spaces that emerged for just that purpose. The presence of people of Asian heritage and white racism contributed significantly to the sexual geography of new urban environments. “Chinatown” and “Chinamen” signified sexual danger and cultural degradation. Historical studies of migrants of Asian heritage have paid close attention to the way social and political processes of racial othering included sexual othering, but the actual experiences of young men of Chinese heritage have been ignored.[14] As it turns out, young men of Chinese heritage did carve out spaces for themselves in Toronto’s urban sexual culture.

During the first half of the twentieth century, many Toronto-based men of Chinese heritage enjoyed sex, companionship, love, and family life, and they negotiated these relationships in a manner and setting similar to men of white heritage. A desire for physical contact, sexual engagement, companionship, and economic stability led women and men to form mutually beneficial relationships. Some were based on the exchange of intimacy for material goods, shelter, or money, others on love and affection. Some married. Many relationships produced children, some wanted, some not. Whatever the nature of the relationships, evidence of their existence challenges the current perception that during the first half of the twentieth century men of Chinese heritage residing overseas lived sexless, loveless lives as isolated “bachelors.”[15]

Mavis Chu’s oral testimony was the key that initially unlocked this history. Her childhood was seamlessly integrated into the warp and woof of a unique sexual and affective culture that began to take shape in the 1910s and continued to flourish into the postwar era. The findings presented here are based on interviews with Mavis and twenty-nine additional people, who grew up in families of Chinese heritage, eleven of whom had birth mothers of white heritage. Oral testimonies in Paul Siu’s mid-century, Chicago-based study The Chinese Laundryman and Kwok B. Chan’s 1980s study of people of Chinese heritage in Montreal supplement my interviews. The records of Toronto’s Women’s Missionary Society (WMS) of the Presbyterian Church yield further data. Experiences of some women and men who engaged in interracial intimacies were also drawn from news reports in the mainstream paper, the Toronto Star, and in tabloids like HUSH Free Press.

This article focuses on Toronto between 1910 and 1950, a period of rapid urbanization, industrialization, and modernization. At the time of European settlement in the mid-1700s, Cayuga, Mohawk, Neutral, and Seneca peoples occupied the area. Less than hundred years later it was an established colonial settlement and the capital of Upper Canada. By the late 1800s Toronto was a booming metropolis, attracting migrants and immigrants from Europe and the United States and workers recruited from China by the Canadian Pacific Railway. The earliest known resident of Chinese heritage set up shop as a laundryman in 1878. However, the number of residents of Chinese heritage remained low until the 1910s.[16] Unlike Vancouver and Hamilton, Toronto did not impose restrictive laws forcing commercial establishments to remain within the “Chinatown” area.[17] Early city directories and oral history interviews show that men and women of Chinese heritage lived and ran businesses throughout the city. Nevertheless, a significant number settled in the ward, a mixed area of multi-occupied houses and shacks of roughcast or frame structure. Doubling and sometimes trebling up helped keep rents low. Here people of Jewish, Eastern European, Italian and, increasingly, Chinese heritage lived cheek-by-jowl.[18]

After a period of elevated in-migration by people of Chinese heritage in the 1910s, the corner of Dundas and Elizabeth Streets earned the moniker “Chinatown,” but to understand the experience of people of Chinese heritage we need to divest ourselves of the meaning that “Chinatown” has acquired. First, the neighbourhood was more diverse than it was Chinese. As David Angel says, “To tell the history of Chinatown you can’t tell just the history of the Chinese. You have to tell the history of the Italians, the Jews, Indians.”[19] Angel, who grew up in the neighbourhood, is of Asian, African, Irish, and Cherokee heritage and spent almost all of his adolescence in the company of his two best friends, one of Jewish and the other of Italian heritage. Chinese-owned shops, not residents’ heritage, defined Chinatown. For example, Mavis Chu grew up on Walton Street just four blocks northeast of Elizabeth and Dundas. Many of her neighbours were also of Chinese heritage, yet they did not live in Chinatown. For them, Chinatown was a place you went to get groceries, eat at a restaurant, or visit the barber.[20] Understanding the diversity of the neighbourhood and the way people imagined it helps us to unpack some of our assumptions about the nature and rhythm of everyday life, including how unessential ethnic heritage was inside the ward.

One thing that did set people of Chinese heritage apart was the fact that there were so few women of the same heritage. Women did not usually join their male counterparts on their voyage to Gold Mountain. They remained at home, where they were responsible for their children, for their husband’s parents and ancestors, and for the family plot. The absence of women of Chinese heritage, however, did nothing to diminish sexual desire amongst male migrants.[21] In her research on the Canadian newspaper Gongbao, Belinda Huang found romantic stories, pornographic fiction, collections of essays on sexual intercourse and sexuality, and advertisements for aphrodisiacs to be common features. More than sex, some men longed for companionship and children.

In 1946 a man of Chinese heritage produced a revealing article for HUSH Free Press, a popular (and often anti-Asian) tabloid magazine. “The average male Chinese labors under a disability in this Christian country,” he wrote. “Under certain conditions which are not too liberal, he can be admitted to Canadian citizenship; but the Canadian government doesn’t want him to bring any women with him. That rather puts him ‘on the spot.’ He is a very human fellow. He likes female companionship. He likes kiddies. What shall he do?—live like a celibate, or share someone else’s wife, or get a white wife or lady friend of his own. What would you do under similar circumstances?”[22]

Men actively pursued three types of relationships: dating and long-term companionate relationships; common-law and legal marriage; and commercial sex, which was sometimes also companionate. The writer claimed men of Chinese heritage had “hundreds [of women] to pick from”: “Some of them are good, average women seeking only a thrill. Some are trampettes seeking pick-ups. Many of them are unfortunates looking for food, shelter, money and kindness which their own race refuses them; and they find these things, sometimes on a quid pro quo basis, sometimes in the form of pure kindness and sympathy.”[23]

Whether driven by poverty or by an attraction to the exotic “other,” women of white heritage pursued relationships with men of Chinese heritage even when it meant risking incarceration on charges of incorrigibility.[24] Like girls and women who sought out the companionship of men of white heritage in the newly established movie theatres, dance halls, and roller rinks, women flirted with men of Chinese heritage who worked at, managed, or owned one of the many small inexpensive restaurants that popped up in the late 1910s and early 1920s.

Canadians of white heritage recognized that immigration laws prohibiting entry to women of Chinese heritage meant that men would seek out relationships with non-Chinese women.[25] It was largely because of white opposition to race-mixing, interracial marriage, and mixed-race children that laws were passed in British Columbia, Saskatchewan, and Ontario prohibiting men of Chinese heritage from hiring “white women.”[26] Many non-Asians opposed these laws and supported efforts to overturn them. Nevertheless, fears that white women would be endangered by Chinese men abounded, and from the 1880s to the Second World War, the idea that men of Asian heritage posed a “yellow peril” was reinforced in the political sphere, the courts, the print media, on the streets, and in workplaces, although with decreasing intensity with each passing decade.

Ontarians of white heritage were much less hostile than those in British Columbia, but anxieties about white women mixing with Chinese men certainly existed and were channelled into law in 1914 and again in 1928. On 1 May 1914 members of the provincial legislature followed steps taken in British Columbia and Saskatchewan and gave assent to an Act to Amend the Factory, Shop and Office Building Act, which read, “No Chinese person shall employ in any capacity or have under his direction or control, any female white person in any factory, restaurant or laundry.” At the time Saskatchewan’s act was being appealed to the Privy Council, and it was decided that nothing should be done with the Ontario amendment until the appeal had concluded. The issue was forgotten and the amendment lay dormant until 1927, when Ontario consolidated its laws in the Revised Statutes of Ontario. Historian James W. St.G. Walker explains that, according to custom, all laws on the books were proclaimed as a body. Consequently, the 1914 amendment came into effect, but no one took notice until August 1928, when the Toronto Star called on the city to enforce it.[27] Mayor McBride responded by giving men of Chinese heritage “a week or ten days in which to get rid of their white women employees, and if they do not do so in that time they will be arrested.”[28]

Consul-General for China Chow Kwo Haien argued that neither the province nor the city had a right to discriminate against foreign residents.[29] Pastor of the Eastern Chinese Mission in Toronto W. D. Noyes and others joined Chow in his fight to defeat the law, and it was soon “de-proclaimed.”[30] Even if the law was only briefly and unintentionally in force in Ontario, these events remind us that a significant number of non-Asian Torontonians viewed the commingling of women of white and men of Chinese heritage as sexually and morally dangerous and socially deviant. The Globe and Mail’s editorial, for example, denounced the act as “hideously unjust” for “lump[ing] all Chinese . . . as a class of invariable moral degenerates,” yet concluded “the indiscriminate mixing of different colours and races is criminally unwise.”[31]

Female employees of white heritage strongly disagreed. Eighty waitresses petitioned the lieutenant governor to get rid of the law altogether. They described their employers as “perfect gentlemen.” We are “well satisfied with [our] present employment and have no complaints wherever to make as regards [our] employers.”[32] The petition was probably organized by a lawyer representing the interests of Chinese employers, making it possible that women signed the petition for fear of losing their jobs. Other sources, however, illustrate that many of those who worked for, worshipped with, and socialized alongside people of Asian heritage abhorred the racism such legislation institutionalized, suggesting that the petitioners’ claims were their own. A Toronto-based missionary of white heritage who lived for many years in China and spoke Toishan, the dialect of most Toronto residents of Chinese heritage, conducted his own survey of waitresses. They “felt no need of protection and resent interference with their liberty of action,” he reported.[33] Chatelaine, Canada’s leading women’s magazine, explored the debate in a feature article that cited a National Council of Women of Canada study that concluded women who worked for men of Chinese heritage were well paid, and that waitresses of white heritage were more likely to be harmed by men of white heritage.[34]

When provided the opportunity, female employees challenged racist depictions of the “heathen Chinee.”[35] At the Royal Commission on Chinese Immigration hearings held in Portland, Oregon, in 1884, retail worker Gertrude Rathburn testified that she preferred her current position with a Chinese merchant to previous positions she held in “white shops.” Men of Chinese heritage are “perfectly respectful, much more than Americans. They never show the least tendency to take a liberty” and they “pay better . . . I should prefer working for them than a Jew any day,” she added, demonstrating that her feelings toward her employer should not be mistaken for an anti-racist politic.[36] Earlier that month Vancouverite Edith Wharton, a twenty-year-old opium smoker who was “educated” but now was a “fast girl,” was asked how the men she met in opium “dens” treated her: “Waking or sleeping, one act of rudeness from a Chinaman I have never experienced. In that respect they are far superior to white men. Unless you speak to them they will not even speak to you; and, indeed, after the first whiff of the opium you have no desire to speak . . . But I have known Chinamen who were not opium-smokers, and I believe they are far more certain not to offend or molest a woman than white men, especially white men with a glass [of alcohol] in [them].”[37]

These very same arguments, including the disparaging comparison with Jews, were made in the 1930s by Vancouver waitresses who defended their right to work against the imposition of a ban on the employment of white women in Chinatown restaurants.[38]

These incidents tell us about more than the structural history of white racism; they also tell us about racism’s emotional history. Such conflicts, as Rosanne Sia points out, were a source of pain, anger, and suffering for both white women and men of Asian heritage. Willingly choosing to work, consort with, and in some cases marry men of Asian heritage was so far beyond the imaginative capacities of most people of white heritage that white women’s presence in Chinatown was explained in one of two ways: they were innocent victims of rapacious Oriental lust, or they unwittingly fell under the “hypnotic” power of the “mysterious” Chinese.[39] Indeed, women who worked in Chinese restaurants were assumed to be prostitutes. Both parties were harmed by these characterizations—women because it robbed them of any agency, and men because it alienated them from masculine respectability—but in the restaurant world at least, their struggle was a shared one. According to Sia, “Waitresses and [people of] Chinese [heritage] created terms of exchange that fulfilled mutual interests, needs, and desires. They created a world worth fighting to preserve.”[40]

Oral history evidence suggests that young working-class women got a better deal in heterosexual relationships with men of Chinese heritage than they did with men of white heritage, at least during the dating stage. They enjoyed significant autonomy, so much so that ambitious and enterprising women were able to maintain more than one lover for long periods of time.[41] They also enjoyed a lighter domestic labour load. Many of the men assumed responsibility for cooking meals.[42] Sociologist Paul Sui’s Chicago narrators described sex workers as lao-kai (sweethearts). One man roasted a chicken “Chinese-style” to take to his lao-kai during their interview. Asked how much money he gives her when he visits, he responded, “As much as I can afford. Sometimes I give her all I have in my pocket. It depends on how she pleases me, see? If she is sweet to me, I would give her even my bones.”[43] Tabloid coverage of women’s court trials indicate that some men provided women with all manner of material goods, from clothes, to jewellery, to radios, and cash.[44] Author and activist Velma Demerson describes such arrangements in her relationship with Harry Yip.[45] Demerson had first-hand experience as the lover of a man of Chinese heritage, and while Yip was too poor to provide her with material goods, he did perform many of the domestic tasks she would have had to do herself were she in a relationship with a white man.

Why did women get a better deal? “Race-mixing” was stigmatized and racial “purity” idealized.[46] To attract and keep the interest of women of white heritage, men of Chinese heritage had to cede some authority, become less patriarchal, and provide for them in ways non-Asian men would never dream of doing. They had to overcome stereotypes that undermined their masculinity; everywhere, it seemed, they were characterized as effeminate, weak, conniving, and untrustworthy.[47] Men increased their participation in domestic labour and made fewer demands on women’s time, to compensate for their diminished social capital. Women accepted, and likely relished, the redistribution of labour.[48] According to Mavis Chu, once married, men sometimes acted as the family patriarch and, in her home at least, their rules about raising children were accepted and followed. Outside of marriage, however, “men gave into the demands of their girlfriends in order to appease them so they wouldn’t move on to other relationships.”[49]

Women who partnered with men of Chinese heritage were typically young and working class.[50] Some were Ontario-born of British heritage; others were Irish, Italian, and Russian. Some were from the United States, and a disproportionately high number were French Canadian. Newspaper accounts of women arrested for consorting with men of Chinese heritage and who were accused of engaging in prostitution indicate that some began socializing and engaging in sex as early as fourteen, but most were sixteen or seventeen. Perhaps some were survival sex workers, but most were likely working girls exercising their autonomy and acting on their sexual desires and financial needs. Marriage certificates and records of the WMS indicate that those who married were typically between eighteen and twenty years old. Some married couples, as we shall see later, operated bawdy houses together. Other couples met, courted, and married outside the context of the sex trade. In all cases, restaurants were a popular meeting ground.

Since the late nineteenth century, more and more young men and women were out earning wages, and eating and socializing in mixed public spaces. They negotiated the heterosocial world with peers, not parents, at their side.[51] Racism restricted the ability of men of Asian heritage to access the rich heterosocial culture that blossomed in and around roller rinks, vaudeville and movie theatres, and dance halls in the early twentieth century. Chinese-run restaurants, however, offered a very similar stage for flirtation and experimentation. In the 1920s the number of restaurants owned and operated in Toronto by men of Chinese heritage skyrocketed, from 32 in 1917 to 202 in 1923.[52] Scattered across the city, these restaurants sold Western-style food at lower prices, making them the economical choice for working-class Torontonians.[53] Few were on a tighter budget than young women. The 1911 census shows that there were 63,013 “working girls” in Toronto, yet women’s annual average of $667 per annum was 55.2 per cent of what male wage earners brought home.[54] Blue-collar female workers fared worse, of course, averaging only $578 per annum. Their wages ranged “from $9.01 per week for women in service to more than $15 per week in some forms of textile industry.”[55] In 1919 the Ontario Department of Labour calculated the minimum cost of board and lodging for wage-earning women at $6 to $7 per week. Few working-class women could afford even that. Thus inexpensive restaurants were a boon. Many young single workers did not have access to cooking facilities, and even for those who did, inexpensive restaurants saved them having to prepare their own meals after a ten- or twelve-hour workday.[56]

Wage discrimination also explains the disproportionately high number of French-Canadian women appearing in tabloid reports of vagrancy and similar charges laid in cases involving men of Chinese heritage. In every Canadian province francophones earned lower wages than anglophones.[57] In Toronto, limited English language skills combined with anti-Catholic sentiment made finding remunerative employment even more challenging. The more economically marginalized women were, the more willing they were to venture past the stigma associated with anything “Chinese” and eat at restaurants owned and operated by people of Chinese heritage.[58] Once there, perhaps they discovered that men of Chinese heritage were less prejudiced toward French Catholics than were Torontonians of British heritage. As Dick Hoerder observes of the post-migration experience, “Structural racism . . . [and] the segregation into enclaves, Chinatowns or other, was undercut by mutual support and respect.”[59] Unmarried or far from any marriage partner and living on the margins of respectable Anglo-Protestant society, French-Canadian women in Toronto were perhaps that much more willing to transgress the social prohibition against interracial sociality with people of Chinese heritage.[60]

In turn-of-the-century Toronto, heterosocial opportunities blossomed, but not for people of Chinese heritage. According to narrators, people of Asian heritage were restricted to seating at the rear of movie theatres. If this was the practice in theatres, it is likely that public venues such as roller rinks, dance halls, and the nearby vaudeville theatre were informally if not formally segregated. Inside restaurants owned by people of Chinese heritage, the danger of verbal reprisals or physical violence for race “mixing” was minimized.[61] More than a stepping stone to economic stability and advancement, restaurants facilitated men’s participation in the vibrant urban dating scene. A 1935 report about these relationships explained that couples typically met “in [or near or around] restaurants . . . Over time they get to know each other . . . they fall in love . . . and then they marry.”[62] Restaurants were probably the safest place for a man to approach a woman, and for women to openly engage with him. By returning regularly, young women and men became acquainted over time.

Such were the circumstances in which Velma Demerson, eighteen years old, half British and half Greek, met Harry Yip. Demerson’s mother lived on the outside edge of respectability. She was a fortune-teller, ran a working-class boarding house, and entertained a series of male lovers who contributed to the sense of chaos, instability, and conflict that marked Demerson’s everyday home life. One day a waiter of Chinese heritage asked Velma out on a date, and she accepted. “My new friend guides me up the stairs of a rather ancient house to his isolated room on the third floor,” she recounts in her autobiography. “He hangs up my coat, removes my shoes, and puts my feet in his slippers.”[63] On her second visit Harry presents her with her own pair of slippers and a key to his apartment. She began to spend more and more time there, coming and going as she wished. Harry’s apartment was a welcome retreat from her mother’s home. He kept the cupboards stocked and cooked all their meals.

Men, especially young men, adopted some and adapted other North American heterosocial gender styles and roles. They donned fashionable suits and slicked back their hair. Harry Yip wore tinted glasses and a fedora. “He is my George Raft, my Humphrey Bogart,” Demerson gushed.[64] A 1932 Toronto Star article explained, “Young Chinese Canadians[65] are western through and through, western in their mode of living, in their pleasure, [and] in their dress.”[66] Hollywood movies, shows at the local vaudeville theatre, English classes taken at churches servicing the community, and the behaviour of customers and people on the street provided all the education men needed in North American style and fashion, heterosociality, and gender role expectations. When men like Harry Yip assumed domestic responsibility for cooking, for example, they knew they were providing something most other men did not.

No matter how Western they appeared, however, social sanctions against race-mixing made dating perilous for both parties. Women of white heritage who dared socialize with Asian men risked more than their reputation, as Demerson found out. In the 1910s simply being in a Chinese restaurant was cause for suspicion, and the morality squad arrested women found in them.[67] In May 1910 Constable Black arrested Emma Richardson for “‘hanging around Chinatown joints.’” The magistrate sentenced her to six months in the Mercer Reformatory for Women.[68] In June 1912 Levina Bowden was arrested “in a Chinese restaurant . . . where she was smoking cigarettes.” She was charged as a vagrant and sentenced to twenty-five dollars and costs or fifty days.[69] Whether for a meal, for cash, for adventure, or for love, women who associated with men of Chinese heritage were seen as a social problem resulting from the stresses of urban life in the industrialized city and were categorized by morality police and certain (but not all) judges of the court to be in need of “re-direction.”[70]

As these stories indicate, for white women simply being seen in Chinatown was enough to attract the attention of state authorities.[71] Morality officers imposed the racialized values of the settler colonial state by discouraging women from consorting with men of Asian heritage, by threatening to arrest them, and, when that didn’t work, by laying charges against them. The police likely enjoyed success with this method, but women sometimes held their ground and fought back against the intimidation. In 1943 two officers picked up Jean and Lillian, both of white heritage and accompanied by men of Chinese heritage. Jean had previously been warned against hanging around with “Chinamen,” but she ignored the warning and the police charged her with vagrancy. In court the arresting officer testified, “She says she will go with all the Chinks she can, and will not be put out of Chinatown. She told me it was none of my business what she was doing.” When asked why he picked her up, the officer replied, “Because she talked to different Chinamen every night,” because she had a brand new bicycle, and because she was not working. Although she was not charged with prostitution, the officer’s testimony implied as much. Jean told the court that she had been dating Harry Louie, the owner of the Parkdale Café, for three years, that she had her own address and a part-time job at a Chinese café. The male judge dismissed the charges.[72]

Not everyone was so lucky. At the same court hearing Audrey Haley, seventeen, was brought in “by those experienced Chinatown policeman, John Murray, Cecil Pane and Roy Haliburton,” who charged her with vagrancy. Haliburton told the magistrate he saw Audrey on the street at 5 a.m. “with an Indian girl.” Audrey explained that she lived with Fred, a “Chinaman,” at a nearby boarding house. Magistrate Prentice remanded her for custody.[73] Morality squad officers could simply pluck women off the streets and out of cafés and restaurants and arrest them under a variety of laws, and sometimes the courts backed them up.[74] Other state agents acted similarly. In 1915 a customs official stopped a couple of white and Chinese heritage from entering the United States. The man was detained and the woman sent back to Toronto, where she was charged with vagrancy and given a suspended sentence, “‘after promising to have nothing to do with any Chinaman.’”[75] The state used its power to disrupt intimate relationships they deemed immoral, improper, and un-Canadian.

Incorrigibility charges were sometimes laid at the request of mothers and fathers.[76] At her mother’s prompting, Velma Demerson’s father had her arrested and charged under the Juvenile Delinquents Act as “incorrigible,” on the grounds that she was unmarried and living with a man. Sentenced to the Belmont Home for Girls, Velma and the other inmates were transferred to the much more punitive Mercer Reformatory for Women, an adult prison for women convicted of serious crime, when the Belmont was converted into a senior’s home. While at the Mercer she gave birth to her son, Harry Junior.[77] Had Demerson and Yip married, her parents and the courts would not have been able to intervene, and she would have been spared the years of physical and emotional suffering at the hands of the Mercer staff.

As crimes, vagrancy and incorrigibility hardly seem significant, yet they were among the most common charges women faced, and punishments were often heavy.[78] During the first decades of the twentieth century, sexual promiscuity among women was framed as a social, moral, and health problem caused by the rise of the urban working girl and the evil temptations of city life. Feminists and moral reformers were keen to use the coercive powers of the police, the courts, and the prison system to punish, control, and correct women who stepped outside the bounds of sexual respectability,[79] so they expanded the regulatory tools available. In addition to existing vagrancy laws, in Ontario the Female Refuges Act (OFRA) and the Juvenile Delinquents Act (JDA) introduced new ways to impose restrictive controls.[80] Incorrigibility, or the refusal to follow parental or state dictates, was first introduced with the OFRA in 1897 but was more often used under the 1908 JDA. The act was a response to the crisis of poverty, and the street crime and sexual promiscuity it produced in rapidly expanding urban centres like Toronto, problems that many considered to be compounded by the increased autonomy of young people and decline of parental control and Christian influence. Young men were targeted for property crimes like theft, women for crimes related to sexual morality.[81] As Tamara Myers explains of the same phenomenon in Montreal, “As a group, female delinquents were identified as agents of immorality and, given the combination of their age, gender, and unwillingness to surrender to filial duty, they became a force to contend with. Their independence—personified by the working girl and cultural consumer—was read in sexual terms.”[82] Women and girls of white heritage who crossed the race line and mixed with men of non-white heritage were more likely to be harassed by the police and punished by the courts.[83] Like the men they consorted with, single working girls and women who engaged in heterosocial activities were characterized as a threat to the nation-state.

Marriage provided a quick escape from parental and state control, but it created new problems just as quickly as it solved old ones. Women who married men of Chinese heritage lost many social and economic privileges their white heritage had extended to them. Once married, women suffered the stigma of having a Chinese surname. This made getting work even more difficult—their names revealed that they were married (married women were often fired from their jobs), and that the husband was of Chinese heritage. Both were heavy strikes against them. Most men earned less than their white counterparts, thus a wife’s earnings made a significant difference to the family income. One option was for a woman to lie and work under her maiden name, but that meant that unless she was paid in cash, she needed a bank account in her maiden name to cash her paycheque. Many chose to take in boarders, a strategy common among immigrant and migrant groups, and perfectly suited to the ward where the demand for cheap housing for single men and women was consistently strong.

Another significant impact was the loss of status as a British subject. Marriage law dictated that when women married, they assumed the nationality of their husband. Demerson indicates this was common knowledge among white women who dated men of Chinese heritage.[84] Given that men were acutely aware of their precarious legal status in Canada, this seems likely. The impact of this aspect of Canada’s marriage law created complex problems, as Demerson herself discovered when she set out to go to Hong Kong to join her young son, Harry Yip Junior. The Canadian government assumed that her marriage to a Chinese citizen meant that the government of China would recognize Demerson as a citizen of their country, but they did not, and consequently would not issue her a passport. The only way she could get to Hong Kong was to move to a new city and reapply for a Canadian passport using her maiden name. Her deception was never discovered, but had it been, she would have faced criminal charges.[85] Given her previous conviction under the Juvenile Delinquents Act, it is likely that she would have been returned to prison as a result.

Finally, marriage did not mean that women were any less subject to police regulation. White women in the company of men of Chinese heritage were assumed to be sex workers or simply girls gone bad and were questioned and sometimes even arrested. When vagrancy charges were hard to lay, the police had other tools available to them. In a 1943 account of one such case, Evelyn Grace Wong (figure 2) reported that one plainclothes police officer said to his partner, “There is a girl who lives with a Chino on Walton Street.” They then approached her, and when she refused to give her name, they charged her with being drunk. She refused to give them her name, she explained to the court, because they did not identify themselves as police officers. When they did, she complied. The magistrate nevertheless registered the conviction and imposed a fine of five days or ten dollars and costs.[86]

Despite these obstacles, women of white heritage and men of Chinese heritage married each other according to the laws of the country and with the blessing of Christian ministers.[87] The evidence is too scant to be conclusive, but it does suggest that mixed-race marriages were much more common than we might have imagined. The 1931 census documented 2,554 men of Chinese heritage residing in Toronto. A 1935 non-governmental report suggested that 85, or 3.35 per cent, were married to white women. An examination of marriage certificates issued at Toronto’s City Hall in 1921, 1924, 1927, and 1930 supports this estimate.[88] Seventeen new marriages of Anglo-Canadian, Anglo-American, and French-Canadian women to men of Chinese heritage occurred (1921: 7, 1924: 3, 1927: 10, 1930: 2). Of these, most men were between thirty and forty years old and employed as waiters (3), chefs (3), cooks (4), and restaurant keepers (5), the last being the most financially prosperous. One was an “agent” and another a barber. The women were on average ten years younger than their husbands and were employed as waitresses (3), domestics (2), and salesladies (2). One was a switchboard operator and one a laundress. Six listed no occupation.

Figure 2

Evelyn Grace Wong

Legally married couples were only the tip of the iceberg. A great many more lived common-law. Perhaps they wanted to avoid the social and legal problems marriage created for women, perhaps some of the women knew their partners had a wife in China and did not want to marry them, or perhaps they simply preferred to live outside the constraints of legal marriage.[89] Whatever the case, there were so many interracial couples that in 1937 the WMS hired Mrs. W. F. Adams for the sole purpose of working with “white women married to Chinese in Toronto.”[90] In her first year on the job, Adams documented over two hundred mixed “marriages.” Two years later the secretary of the Women’s Missionary Society reported, “There are nearly 800 in the city [accounting for 31.3 per cent of the male population], and the number is increasing.”[91] It is possible that the estimate was provided by Adams herself and that she exaggerated the numbers in order to protect her position, but evidence from Montreal, New York City, and the Canadian census suggests that, as she became more integrated and more trusted in the community, she became more aware of the number of informal relationships that existed.[92] If accurate, the Women’s Missionary Society’s estimates suggest approximately 10 per cent of couples legally wed and 90 per cent opted for what we might call open-ended relationships where both parties were free to leave at any time.[93] An exact count is impossible, but there seems little doubt that in the first half of the twentieth century interracial relationships were a common feature of everyday life among English-speaking men of Chinese heritage.

Everyone from tabloid journalists to Presbyterian missionaries agreed that intermarriage was a direct consequence of Canadian immigration laws that restricted women of Chinese heritage from entering Canada. Where the tabloids decried the growing phenomenon of race-mixing and called upon “authorities” to prevent it, the WMS was sympathetic to white women’s struggles. Disowned by their families, rejected by white society, and eschewed by most people of Chinese heritage, these women lived their lives and raised their children without the benefit of kinship or friendship networks. Ironically, though they lived in the very heart of a booming metropolis, their daily lives unfolded in overwhelming isolation. As Lui found in 1950s Chicago, a white woman had to relinquish her contacts with the white world and “seldom takes part with her husband in the social world in Chinatown . . . As a result the family is at the margin between two social worlds, and it may involve tremendous inner and cultural conflicts among members of the mixed marriage.”[94] Whatever they thought of the Bible study classes organized for their benefit, women of white heritage embraced the WMS’s outreach efforts. Missionaries’ efforts to win souls for Christ helped break their isolation, and white wives praised WMS members for their non-judgmental attitude.

Unfortunately Adams’s community-building work did not survive her 1944 retirement.[95] The children of these marriages interviewed for this project describe their mothers’ lives as lonely and friendless. None recall their mothers participating in church or any other kind of community-based social activities. Gordon Chong’s mother suffered extreme depression throughout his childhood. So debilitating was her illness that his father assumed all child-rearing duties. It was he who bundled Gordon and his siblings off to school each morning. After-school hours were spent doing homework in a family friend’s restaurant, where they also took their dinner. Their father brought them home, bathed them, and put them to bed. The cause of his mother’s depression is unknown, but doubtless the isolation she endured exacerbated it.[96] Mavis Chu recalls that white women would seek out her mother’s advice from time to time, but white female partners of Chinese men did not form even a coffee klatch.[97]

And yet Chu’s mother was surrounded by women of white heritage. Eileen contributed to the household budget by renting out five of the seven rooms in their two-storey house to single men of Chinese heritage. Harry Chu died just six years after they married, and Eileen married Mon Lew soon after. (She was extended an offer of marriage by an upper-middle-class white man on the condition that she give up her children. She declined.) Once Lew was installed in the house, at least once a week a different boarder’s “girlfriend” came visiting. Eileen protested, but Mon Lew insisted that if they barred the women they would lose the boarders. Over time these women’s comings-and-goings became part of the everyday rhythm of the household. Mavis vividly recalls how

we knew on Wednesday night it was, say, Flo would come to see somebody upstairs and we’d just say they were their girlfriend . . . I remember we were babysitting one night, my brother and I, and [Flo] brought us a bag of chips. Well that was really neat. We’d say, “Hi Flo.” ’Cause she had to come in through the hall and walk past us . . . I suppose what they were giving was sexual favours, and probably for a price. So I would say they were “call girls” because they had an arrangement with some of the men that they would come on certain days.[98]

Girlfriends sometimes joined the men who gathered in the family kitchen to play mahjong late into the night.

Sex-trade workers became so well integrated into Mavis’s household that some came to be considered family. A regular companion of Mavis’s “uncle” earned the honorific “Auntie.”[99] Mavis recalls how Aunt Joan became her advocate. “I was taking up tap dancing [and when there was a problem] Joan went to the school and asked why that was going on, where my mother was more timid and she wouldn’t do that. I admired Joan for that.”[100]

Joan and Eileen Neeson became close friends. Concerned that Eileen had not had a holiday for as long as she had known her, Joan took her to Montreal for a week-long break and introduced her to her family, including her two young daughters. When some years later Joan decided to marry, she wanted to erase her sex-trade past and cut ties with the Chu family. She was important enough to Mavis, however, that when Mavis married she went to considerable lengths to find her and invite her to the wedding.

Sex work in a family home was sometimes a source of conflict. In 1947 Annabelle Eng and her husband allowed Mary Long, common-law wife of Frank Long, to stay with them during a period of conflict in the Long marriage. Shortly after arriving, Mary began entertaining male visitors. It was likely a way to raise the cash she needed to support herself and her newborn son. Mary’s entertaining enraged the Engs, who accused her of engaging in prostitution in their home. After a confrontation between the two women, Mary Long charged Annabelle Eng with causing damage to her baby carriage. When they appeared in court, Eng explained to the judge, “Ours is a respectable home and we have three children. I don’t want them to see anything like this. It would not be good for them.”[101] Like Eileen, Eng tried to maintain normative standards of propriety. Eng eventually won the battle to keep the sex trade out of her home, but she could not have shielded her children from it. Virtually every one of the men and women who provided oral testimony evidence for this study vividly recalls, sometimes fondly, sex workers in and around the neighbourhood. Many recount the prices street-level workers charged, since it was the refrain with which they approached passing men. In the 1950s it was “Ten and three?” meaning ten dollars for a room and three dollars for sex.[102] One woman remembers the heavily made-up sex workers who dropped off their perfumed clothes at her family’s laundry. As a young girl, these women appeared to her as worldly, mysterious, and exotic. And they were nice.[103]

Figure 3

Auntie Joan and Mavis Chu

Most Canadians regarded sex workers as social outcasts, morally depraved, and outside the family. Their labour was criminalized and stigmatized, and if they had children they were more at risk of having them removed by the state than were other women. These attitudes had no place in Toronto’s Chinatown. Sex workers were not just present, and they were more than merely tolerated. They were an important part of everyday life for men of Chinese heritage and the community that supported them, as an oft-repeated anecdote about pharmacist Tom Lock illustrates. In addition to Chinese herbal medicines and North American pharmaceuticals, Lock stocked condoms and aphrodisiacs, which his clients purchased in healthy quantities. During slow periods of the day, he passed the time watching—and timing—sex workers and their clients as they slipped in and out of the Guangtong Hotel across the street. “That didn’t take long!” he was known to quip. Those who knew him invariably tell this story as a humorous tale about everyday life in Chinatown, not as a shameful part of the past.[104] Lock’s attitude toward sex workers was learned at home. His mother was an active member in the Presbyterian Church, but that did not get in the way of her close friendship with the person who ran the Rex Hotel on Queen Street, then “the biggest whorehouse in Toronto.”[105] His much older sister came to know a sex worker who turned tricks near her home. While working, the worker left her toddler Virginia, whose biological father was of Chinese heritage, alone on the sidewalk to amuse herself. At these times Lock’s older sister would often keep a watchful eye on Virginia; eventually she adopted her as her own.[106] When Tom’s sister died, their mother assumed responsibility for Virginia. Virginia and Tom were raised as brother and sister.

Sex workers helped the community grow and prosper. They moved their propositioning skills from the streets to the seats and filled restaurants owned by people of Chinese heritage. By purchasing meals and attracting customers, they increased revenues. Restaurants owned by men of Chinese heritage became known as places where young, poor women could get fed, either out of sympathy or in exchange for providing sexual services. Dubbed “consent girls” by the tabloids, young women actively bargained sex for food and shelter and were sometimes able to make good money for themselves in the process.[107] Many men of Chinese heritage operated run-down hotels that earned substantial sums of money from the sex trade. One explained to a friend how he could rent a single room multiple times in one night because they were used for only half an hour. “And I don’t even have to change the bed[ding].”[108] Sex workers were useful to men in other ways. For example, a Chinatown shopkeeper who adopted a mixed-race boy to raise as his own hired a sex worker to pose in court as his common-law wife. The adoption was approved.[109]

Treating sex workers as if they matter and acknowledging bachelors’ need and desire for sex and intimacy is not something most historians are trained to do. Like gambling dens and opium smoking, exchanging sex for money is often treated as the disreputable side of the history of migrants of Chinese heritage. In a recent publication, for example, historian John Zucchi writes, “By the late 19th century the rich associational life of Chinese bachelors, distant husbands and a few families filled in the quarters. True, gambling dens and brothels retained a presence but temples, schools, churches and other properties owned by organizations emerged with time.”[110] By phrasing it in this way, we apply a standard of measurement from the viewpoint of mainstream white society, not from the viewpoint of Chinatown residents for whom gambling dens and brothels were as valued as churches, temples, and schools, if not more so. The measure of respectability, in other words, is taken according to a set of values that many people in the community did not themselves share.[111]

Another way we can see the different set of socio-sexual values that evolved in this unique urban context is in the evidence that some sex workers and “consent girls” married men of Chinese heritage. Rose Rosenfeld is an example. Born in 1917, Rose was the rebellious daughter of Jewish Russian-Polish parents who refused to conform to the social dictates that constrained young women’s lives. All the evidence suggests that she engaged in the sex trade in some fashion, and she maintained ties to that social circle well after she turned to other means of support.[112] Bringing children into the world complicated her life and forced her to creatively adapt to the normative demands put on her. Her friend Kitty raised her first child, perhaps because he was born with a disability and Kitty was willing to take over his care. The Children’s Aid Society took custody of her second. To avoid losing Jim, her third, she married Chen Ng, a laundry worker. She and Chen rented rooms to boarders, almost all of whom were female sex workers whom Jim came to know by their nicknames, among them “Horse Face Betty” (figure 4) “Bocci,” and “the Big Job.” His mother also ran a bootlegging business out of their Elm Street home that bordered on Chinatown. When Chen died, Rose married again, and again she chose a man of Chinese heritage. Lew Doe (figure 5) was likely the biological father of Rose’s last child.[113]

Figure 4

“Horse-Face” Betty, Toronto, Ontario

Some couples were in the sex trade business together. In 1916, A. B. and her husband S. B. were incarcerated for keeping a house of ill fame. French Canadian P. P., who married H. W. in 1920, spent the rest of the decade in and out of prison on charges related to possession of opium, vagrancy, and keeping a common bawdy house located in the heart of Chinatown. Tabloid coverage of the courts shows that numerous couples were jointly charged with running bawdy house operations, indicating that marriage did not always end involvement in the sex trade.[114] White women could also play a very informal role in arranging sex. In 1935 the police arrested Isobel McIntyre and Violet Rushford. Rushford was living common-law with George Gin, with whom she had a baby. According to the story, McIntyre had come to the Rushford-Gin home to engage in sex with Gin’s friend George Lee in exchange for money.[115]

Sex, intimacy, and desire were part of the migration experience for people of Chinese heritage. As we know, many if not most men planned to return to Guangdong and did not bring wives with them. Should they have wanted to, racist immigration laws made it difficult if not impossible to do so. This did not necessarily mean, however, that migrant men led lonely, isolated, and celibate lives. As we have seen, they sought out sexual and affective relations with women of white heritage. Beginning in the 1910s, young women and men created a vibrant culture of interracial heterosociality. The men and women who are the subjects of this article were not always the most “respectable” members of Toronto society, but their stories offer important clues to how those on its margins forged economic, social, and affective relationships that defied the conventional values of their times.

Figure 5

Rose R. and Lew Doe with children

Examining the sexual mores and practices, including the illicit and the illegal, of men of Chinese heritage and the women who partnered with them enriches our understanding of how race and racism shaped the migration experience. It also deepens our understanding of working-class experience during the first half of the twentieth century and adds a new layer to the history of exclusion that dominates the narrative of “Chinese Canadian experience.” Paying attention to interracial relationships and the children these liaisons produced raises the question of why white women and interracial children have been excluded from the history of Chinese overseas experience, the history of people in Canada of Chinese heritage, and the history of Chinatowns. Part of the answer is that sex workers and women who lived outside the bounds of respectability are more likely to be excluded from history, especially when history writes a group of people defined by a social identity into the annals of the Canadian past. Because sex workers and “consent” girls are not regarded as respectable, erasing them from history might seem the cost of writing people of Chinese heritage into the historical record. The other issue is the way in which race functions amongst this generation of people of Chinese heritage. Mixed-race couples and their children have always been treated as outside the community proper, and the history we have reflects that point of view. Finally, the exclusion of interracial relationships is reproduced in our history because we have thoroughly convinced ourselves of racism so pervasive that we assumed few people of white heritage would form intimate relationships with people of Chinese heritage. We were wrong.

Identity categories like “working-class,” “sex worker,” and “Chinese Canadian” enable people with shared cultural and economic experiences to mobilize as a group, but these stories illuminate how lived experience always exceeds an identity category’s boundaries. We must take care not to limit our frame of vision to such categories when we look back to the past.

Knowing that the matrix of gender, race, and sexual oppression produced new social relationships does not lessen the fact that Canada’s racist policies wreaked emotional and material havoc in the lives of thousands of people of Chinese heritage. None were living under conditions entirely of their own choosing. But within those constraints there were choices available, and the choices had profound consequences for those who made them. White women were isolated from their families and were never fully accepted by the broader Chinese Canadian community. They were vulnerable to arrest and imprisonment, and men were susceptible to social and legal harassment for consorting with women of white heritage, just as they were to economic oppression on the job market and in the education system.

These findings have important implications for the history of migrants of Chinese heritage. They put to rest the dominant image of absolute sexual celibacy and husbandly devotion to overseas wives. An earlier generation of feminist scholars might have interpreted the heterosexual culture described here as an example of male prerogative and patriarchal privilege in the migrant experience. Clearly gender was a factor in shaping the experiences of men and women, but these relationships were negotiated ones, and in a comparative context women sometimes came out ahead. Racial ideologies diminished male authority, and women reaped the benefits. Men of Chinese heritage and women of white heritage negotiated the urban sexual landscape as it appeared before them, and in so doing fashioned a unique and dynamic heterosexual culture and family life experience. They saw no shame in it then. We should not now.

Parties annexes

Acknowledgements

This project is indebted to Mavis Chu, who brought this history to my attention. I am deeply grateful for research assistance provided by Anne Cummings, Anne Toews, Candice Klein, Brock Hessel, and Natasha Chenier, and for editorial comments provided by Mavis Chu, Cameron Duder, Nicholas Kenney, and the two anonymous reviewers. I gratefully acknowledge research funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council.

Biographical note

Elise Chenier is an associate professor in the Department of History at Simon Fraser University, where she researches and teaches courses on the history of sexuality and modern Canadian history. All of the primary source research materials for this project are available on the Simon Fraser University library server at interracialintimacies.org. Interracial Intimacies is an open-access research and teaching resource tool for high school, university, and post-graduate students.

Notes

-

[1]

Names have been altered by the informant, Mavis Chu, to protect the identity of extended family members.

-

[2]

Mavis Chu, interview by Elise Chenier, 1 June 2011.

-

[3]

Ibid.

-

[4]

For important exceptions, see Jean Barman, “Beyond Chinatown: Chinese Men and Indigenous Women in Early British Columbia,” BC Studies 177 (January 2013): 39–64; and Mary Ting Yi Lui, The Chinatown Trunk Mystery: Murder, Miscegenation, and Other Dangerous Encounters in Turn-of-the-Century New York City (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2005).

-

[5]

Hasia R. Diner, “Ethnicity and Emotions in America: Dimensions of the Unexplored,” in An Emotional History of the United States, ed. Peter N. Stearns and Jan Lewis, 197–217 (New York University Press, 1998).

-

[6]

Alf Lüdtke, “Potential and Perspectives of the History of Everyday Life,” in History of Emotions in America, ed. Jessica C. Gienow-Hecht (New York: Berghahn Books, 1998), 41.

-

[7]

Nicole Eustace, Eugenia Lean, Julie Livingston, Jan Plamper, William M. Reddy, and Barbara Rosenwein, “AHR Conversation: The Historical Study of Emotions,” American Historical Review 117, no. 5 (December 2012): 1487–1531, doi:10.1093/ahr/117.5.1487.

-

[8]

manyheadedhailwood, “Claire Langhamer, ‘Everyday Love and Emotions in the 20th Century,’” The Many-Headed Monster, http://manyheadedmonster.wordpress.com/2013/08/28/claire-langhamer-everyday-love-and-emotions-in-the-20th-century/.

-

[9]

Thomas J. Cogan, “Western Images of Asia: Fu Manchu and the Yellow Peril,” Waseda Studies in Social Sciences 3, no. 2 (November 2002): 37–64; Hilda Glynn Howard, The Writing on the Wall (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1974); Emily F. Murphy, The Black Candle (Toronto: T. Allen, 1922); J. S. Woodsworth, Strangers within Our Gates: Or, Coming Canadians (Toronto: F. C. Stephenson, 1909).

-

[10]

Recent studies that foreground gender in migration include Katharine M. Donato, Joseph T. Alexander, Donna R. Gabaccia, and Johanna Leinonen, “Variations in the Gender Composition of Immigrant Populations: How They Matter,” International Migration Review 45, no. 3 (2011): 495–526; Donna Gabaccia and Elizabeth Zanoni, “Transitions in Gender Ratios among International Migrants, 1820–1930,” Social Science History 36, no. 2 (2012): 197–221; Nancy L. Green, “Changing Paradigms in Migration Studies: From Men to Women to Gender,” Gender & History 24, no. 3 (2012): 782–98.

-

[11]

Yuen-fong Woon, The Excluded Wife (Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1998).

-

[12]

For a critique of how historians have approached gender imbalance, see Adele Perry, “‘Oh I’m Just Sick of the Faces of Men’: Gender Imbalance, Race, Sexuality, and Sociability,” BC Studies 105/106 (Spring/Summer 1995): 27–44.

-

[13]

Historical documentation and analysis of interracial marriages in the United States during the same period can be found on the site for the Chinese in Northwest America Research Committee, http://www.cinarc.org/Intermarriage.html.

-

[14]

Examples of historical studies of the racial stereotypes and social and legal prohibitions that made interracial socializing between women and men seem unlikely include Henry Yu, “Mixing Bodies and Cultures: The Meaning of America’s Fascination with Sex between ‘Orientals’ and ‘Whites,’” in Sex, Love, Race: Crossing Boundaries in North American History, ed. Martha Hodes (New York: New York University Press, 1998): 444–63; Madge Pon, “Like a Chinese Puzzle: The Construction of Chinese Masculinity in Jack Canuck,” in Gender and History in Canada, ed. Joy Parr and Mark Rosenfeld, 88–100 (Toronto: Copp Clark, 1996); Patricia Roy, A White Man’s Province: British Columbia Politicians and Chinese and Japanese Immigrants, 1858–1914 (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 1989); Constance Backhouse, “The White Women’s Labor Laws: Anti-Chinese Racism in Early Twentieth-Century Canada,” Law and History Review 14, no. 2 (October 1996): 315–68; Peter S. Li, The Chinese in Canada, 2nd ed. (Toronto: Oxford University Press, 1998); Paul C. P. Siu, The Chinese Laundryman: A Study of Social Isolation, reprint (New York: New York University Press, 1987); Nayan Shah, “Between ‘Oriental Depravity’ and ‘Natural Degenerates’: Spatial Borderlands and the Making of Ordinary Americans,” American Quarterly 57, no. 3 (2005): 703–25.

-

[15]

Barman makes this point in Barman, “Beyond Chinatown,” 15–16, and note 22.

-

[16]

Chuen-yan David Lai, Chinatowns: Towns within Cities in Canada (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 1988), 97.

-

[17]

Ibid., 99.

-

[18]

Richard Dennis, “Private Landlords and Redevelopment: ‘The Ward’ in Toronto, 1890–1920,” Urban History Review 24, no. 1 (October 1995): 21–35.

-

[19]

David Angel, interview by Elise Chenier, June 2011.

-

[20]

Lai, Chinatowns, 5–7.

-

[21]

Why so few women came to North America is explained in detail in Madeline Y. Hsu, Dreaming of Gold, Dreaming of Home: Transnationalism and Migration between the United States and South China, 1882–1943 (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2000).

-

[22]

“Chinese Love and Gambling Fascinate ‘White’ Women,” HUSH Free Press, 23 February 1946.

-

[23]

Ibid.

-

[24]

See Velma Demerson, Incorrigible (Waterloo, ON: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2004); on the exoticization of people of Asian heritage, see Yu, “Mixing Bodies and Cultures.”

-

[25]

“Drastic Chinese Immigration Laws Cause Mixing of the Twain: Fifteen Chinese Women Admitted to Canada in Twenty-Three Years,” HUSH Free Press, 18 January 1947. This reasoning informed parliamentary debates about Chinese immigration restrictions and compelled even experts in the child welfare field to advocate for their elimination. See Robert E. Mills, “The Placing of Children in Families, Part II,” Canadian Child and Family Welfare 14, no. 1 (July 1938): 52; K. Paupst, “A Note on Anti-Chinese Sentiment in Toronto,” Canadian Ethnic Studies / Études ethniques du Canada 9, no. 1 (1977): 54–9.

-

[26]

Constance Backhouse, “White Female Help and Chinese-Canadian Employees: Race, Class, Gender and Law in the Case of Yee Clun, 1924,” Canadian Ethnic Studies 26, no. 3 (1994): 34–52; Joan Sangster, “‘Pardon Tales’ from Magistrate’s Court: Women, Crime, and the Court in Peterborough County, 1920–50,” Canadian Historical Review 74, no. 2 (1993): 161–97; Backhouse, “White Women’s Labor Laws”; James W. St G. Walker, “Race,” Rights and the Law in the Supreme Court of Canada: Historical Case Studies (Waterloo, ON: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 1997).

-

[27]

Walker, “Race,” Rights and the Law in the Supreme Court of Canada, 114–15.

-

[28]

“Chinese Given Week to Replace Women,” Toronto Star,28. August 1928.

-

[29]

Ibid.

-

[30]

Ann Elizabeth Wilson, “A Pound of Prevention—or an Ounce of Cure? A Plea for National Legislation on a Growing Problem,” Chatelaine, December 1928, 12, 13, 55; Walker, “Race,” Rights and the Law in the Supreme Court of Canada, 114–16.

-

[31]

Ibid., 115.

-

[32]

Carolyn Strange and Tina Merrill Loo, Making Good: Law and Moral Regulation in Canada, 1867–1939 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1997), 122.

-

[33]

Walker, “Race,” Rights and the Law in the Supreme Court of Canada, 116.

-

[34]

Wilson, “A Pound of Prevention.”

-

[35]

Backhouse, “White Women’s Labor Laws,” 361.

-

[36]

Canada, Report of the Royal Commission on Chinese Immigration Report and Evidence, CIHM/ICMH Digital Series, no. 14563 (Ottawa: Printed by order of the Commission, 1885), 173, http://www.canadiana.org/ECO/mtq?doc=14563.

-

[37]

Ibid., 150–1.

-

[38]

Rosanne Sia, “Making and Defending Intimate Spaces : White Waitresses Policed in Vancouver’s Chinatown Cafes” (MA thesis, University of British Columbia, 2010), 51.

-

[39]

See Lui, Chinatown Trunk Mystery, 144; Roy, White Man’s Province, 18; Mariana Valverde, “When the Mother of the Race Is Free: Race, Reproduction and Sexuality in First-Wave Feminism,” in Gender Conflicts: New Essays in Women’s History, ed. Franca Iacovetta and Mariana Valverde (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1992), 14. Examples from Toronto’s tabloids include “Yellow Man Debauches Young Girl: Orillia Chinaman’s Mysterious Power over Beautiful Young Girl,” HUSH Free Press, 28 November 1929; “‘Chinese Mad’ Women!!: The Magic Spell of the Yellow Hand—In Rosedale and the Underworld—Well Connected Girl Admits 54 Visits to Chinese Dens—Sordid Story,” HUSH Free Press, 16 June 1932; “Beware of the Yellow Peril: Young Girl Seduced in College Street Love-Nest?,” HUSH Free Press, 4 February 1932; “White-Slaver Convicted: Infamous Headquarters of Chinese Men and White Women—Register Reveals Identity of Many Prominent Canadians—Small-Town Girls Frequent Visitors,” HUSH Free Press, 17 September 1932; “Winnipeg White Slaver: Chinaman Holds Canadian Girls in Bondage,” HUSH Free Press, 29 January 1931; “Yellow Kisses: Strange Passion for Chinese Butler Traps Mrs. True Mandevell Sincoup—Husband Interrupts Settee Siesta—Rector’s Daughter Divorced,” HUSH Free Press, 12 October 1935; “White Slave Lures: Sinister Servant-Girl Snare Used by Convicted Montreal Procuress, Mme. St. Maurice, to Drag Young Girls into the Vice Joint’s Clutches,” HUSH Free Press, 28 September 1935; Evangeline Dalton, “The Yellow Peril: White Girl Tells of Shocking Orgies with Chinaman,” HUSH Free Press, 28 April 1932; “Young Girl Succumbs to the Spell of the Orient: Driven Along by Squalor, Misery and Disease, She Reaches the End of the Road,” HUSH Free Press, 1 September 1945; “White Slave Girl Victim Rescued from Vice Den: Police Crack Down on Chinatown, Break Up White Slave Gang and Send Leaders to Jail,” HUSH Free Press, 23 May 23, 1942; “Tricked by White Mate Oriental Seeks Revenge: Chinese Code Death on White Girls Deserting Chink for Other Chink,” HUSH Free Press, 15 July 1944; “Vancouver Yellow Peril: Take a Census Now—Deport Every Chinaman without Immigration Papers!,” HUSH Free Press, 16 March 1935.

-

[40]

Sia, “Making and Defending Intimate Spaces,” 14.

-

[41]

Garland, interview; “Tricked by White Mate Oriental Seeks Revenge,” HUSH Free Press, 15 July 1944; “Two Chinamen Fight Over Young White Woman,” Justice Weekly, 17 March 1951.

-

[42]

Chu, interview; J. Rosenfeld, interview by Elise Chenier, 4 June 2012.

-

[43]

Siu, Chinese Laundryman, 266.

-

[44]

“16-Year-Old White Girl Convicted Robbed 50-Year-Old Chinese Lover,” Justice Weekly, 9 February 1946; “Helped Old Chinaman Spend $1,000 Then Deserted Him, Crown Attorney Says of Young White Girl in Court,” Justice Weekly, 27 April 1946; “Overnight Marriage Has Court Sequel: Wife Leaves Chinese Hubby; Takes Radio,” Justice Weekly, 1 March 1947.

-

[45]

Demerson, Incorrigible.

-

[46]

Mariana Valverde, The Age of Light, Soap, and Water: Moral Reform in English Canada, 1885–1925 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1991); Angus McLaren, Our Own Master Race: The Eugenic Crusade in Canada, Canadian Social History Series (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1990).

-

[47]

Roy, White Man’s Province; Judy Fong Bates, China Dog and Other Tales from a Chinese Laundry (Toronto: Sister Vision, 1997); Pon, “Like a Chinese Puzzle.”

-

[48]

Anthony Chan claims that married couples in which both partners were Chinese maintained patriarchal social practices from Guongdang province. Chan, Gold Mountain; for an example of a woman who rejected those customs, see Denise Chong, The Concubine’s Children: Portrait of a Family Divided (Toronto: Penguin Books, 1996).

-

[49]

Mavis Chu, email correspondence, 25 July 2013.

-

[50]