Résumés

Abstract

In the 1950s and 1960s modernist town planning reordered countless cities through urban renewal and freeway-building projects. Applying rational planning expertise generated emotional responses that often lingered long after redevelopment occurred. This article considers the emotional response to urban renewal in two cities advised by the British town planner Gordon Stephenson. In Perth, Australia, Stephenson was amongst a group of experts who planned a freeway that obliterated part of the valued river environment and threatened a historic structure. In Halifax, Stephenson prepared the initial scientific study used to justify dismantling part of the downtown and a historic black community on the urban fringe. While the Perth case generated an explosion of emotional intensity that failed to prevent environmental despoliation but saved some heritage assets, the Halifax example initiated a lingering emotional dispute involving allegations of neglect and racism. Comparing cases resulting from the activities of a noted practitioner illustrates differing emotional trajectories produced in the wake of the modernist planning project.

Résumé

Dans les années 1950 et 1960, l’urbanisme moderniste a réorganisé d’innombrables villes dans le cadre de projets de rénovation urbaine et de construction d’autoroutes. L’application de mesures de planification rationnelle a entrainé des réactions émotionnelles qui ont perduré bien au delà des réaménagements. Cet article examine la réponse émotive à la rénovation urbaine dans deux villes ayant suivi les recommandations de l’urbaniste britannique Gordon Stephenson. À Perth, en Australie, Stephenson était parmi un groupe d’experts qui a planifié une autoroute qui a détruit une partie d’un environnement riverain populaire et menacé une structure historique. À Halifax, Stephenson a préparé l’étude scientifique initiale utilisée pour justifier le démantèlement d’une partie du centre-ville et d’une communauté noire historique en zone périurbaine. À Perth, une explosion d’intenses émotions n’a pas réussi à empêcher la spoliation de l’environnement mais a pu sauver certains biens patrimoniaux, tandis qu’à Halifax un conflit émotionnel persistant a vu le jour autour d’accusations de négligence et de racisme. La comparaison de deux cas résultant des activités d’un praticien renommé illustre différentes trajectoires émotionnelles produites dans le sillage de l’urbanisme moderne.

Corps de l’article

The decades following the Second World War produced the heyday of modernist town planning. Technology and the application of science underpinned postwar reconstruction and urban renewal. Many of the planners, architects, and engineers active in the 1950s and 1960s were veterans with first-hand experience of the authority of science and the promise of progress. They enthusiastically embraced technological solutions for major urban projects. Engineers built dams, bridges, and freeways to facilitate urban growth. New technologies allowed architects to dramatically change building form and offer the promise of quality and affordability. City planners applied scientific methodology in broad surveys and plans to improve urban functionality and attack signs of urban decay and blight. The modern movement was, in pioneering planning historian Gordon Cherry’s words, “a heroic adventure which could actually improve man’s condition . . . The future city was seen as massive, comprehensively and rationally planned, using new materials, new technologies and new forms of energy.”[1]

Many of those who embraced progress were deeply committed to improving society and solving problems. They viewed systems of transportation designed for nineteenth- and early twentieth-century needs as inadequate for rapidly growing cities where car ownership was increasing. Residents of sprawling new suburbs needed efficient routes to get to work. In many cities, aged inner-city housing stock had deteriorated and lacked modern plumbing. With the rise of the welfare state, governments sought to improve housing conditions: scientific planning promised to hasten the demise of the slums. Many planners accepted Le Corbusier’s dictum: “Authority must step in, patriarchal authority, the authority of a father concerned for his children.”[2] In the postwar period, planners assiduously applied their growing authority for redeveloping cities.

By the 1950s, governments in many nations supported urban renewal, highway building, and other forms of redevelopment through funding and legislative programs.[3] The redevelopment agenda suited governments eager to do something positive and progressive to address urban problems and strengthen national economies. Although critiques of the negative effects of urban renewal on neighbourhood form and minority populations began as early as the 1960s, before the 1970s political leaders and local business interests generally welcomed the transformations rendered by redevelopment.[4] As recent reappraisals of the legacy of urban renewal have argued, powerful builders were successfully getting things done and driving growth.[5] History has shown, however, that the legacy of urban renewal differs widely across nations and among cities.[6]

With the ascendance of scientific approaches, technological innovations, and concerted governmental action to change urban conditions, the sense of place that people felt towards their cities came under threat in the 1960s. An extensive literature considers the meanings of place and space, reflecting the “spatial turn” in the human sciences instigated by scholars like Henri Lefebvre, Yi-Fu Tuan, David Harvey, and Edward Soja. Psychological research into memory has also contributed to the development of the theory of place attachment.[7] Sociologist Peter Marris used place attachment to explain the way a community mourns for places lost to urban renewal,[8] while historian Peter Read grappled with the meaning of lost places, examining the bereavement people feel when place is destroyed.[9] People have strong cultural attachments to familiar places, for, as urban historian and architect Dolores Hayden argued, “Urban landscapes are storehouses for . . . social memories, because natural features such as hills or harbors, as well as streets, buildings and patterns of settlement frame the lives of many people and often outlast many lifetimes.[10] As Tuan said, people cannot develop a sense of place if the world is constantly changing.[11]

Recently the “affective turn” highlighted the role of emotions in influencing residents’ sense of place. Citing Sarah Dunant and Roy Porter’s observation that rapid transformation erodes old structures and values, leading people to feel a loss of control and uncertainty about the future,[12] cultural theorist Sara Ahmed linked emotion and place. Ahmed noted that the word emotion derives from the Latin, emovere, meaning “to remove, expel, to banish from the mind, to shift, displace.”[13] In the familiar modern sense, emotions are seen as agitations of the mind, but emotions also reveal attachments holding people in place and connecting them to the world. The word emotion once described civil unrest and public commotion. Even today, Ahmed argues, emotions represent sites of political and cultural work through which activism takes place.[14] Emotional contagion, as she puts it, enables emotions to move between bodies. Emotions thus affect action and create political possibilities.[15] In debates about cities, participants often resort to the tactical use of passion, deploying it strategically to influence outcomes.[16]

A leading historian in the field of emotions, Peter Stearns, called on historians to consider the role of changing emotions in explaining protest history.[17] Sociologist James Jasper did just that at a conceptual level by charting the emotions of protest movements.[18] What begins as inchoate anxiety, fear, or indignation, argued Jasper, transforms into “moral outrage directed at concrete policies and decisionmakers.”[19] With someone or something blamed, people articulate common problems and solutions wherein a sense of righteousness draws power from positive and negative emotions: hope, fear, outrage, or anger. He notes that as protest movements gain strength, “defining oneself through the help of a collective label entails an affective as well as cognitive mapping of the social world.”[20] Protest becomes “a way of saying something about oneself and one’s morals, and finding joy and pride in them.”[21] Shifting from the conceptual to the actual, Ahmed noted, “It is hope that makes involvement in direct forms of political activism enjoyable . . . Hope is crucial to the act of protest: hope is what allows us to feel that what angers us is not inevitable, even if transformation can sometimes feel impossible.”[22] According to Jasper, the strength of identification with a social movement comes from its emotional pull: emotion is necessary for people to shift to active protest. Within a movement, reciprocal and shared emotions—affective ties of friendship, love, solidarity, loyalty—are generated. Even when success is unlikely, pride and dignity may grow as people identify with a cause. On occasion, protest succeeds, but often frustration, exhaustion, and unrealistic expectations can lead groups to disband. As political economist Albert Hirschmann once observed, “The turns from public to private to the public life are marked by wildly exaggerated expectations, by total infatuation, and by sudden revulsions.”[23]

This article takes up Stearns’s challenge to consider the role of emotions in protest history by examining reactions to technocratic modernist planning in two major urban redevelopment projects inspired in large part by the same international expert. Comparative analysis offers useful insights into the ways that diverse communities respond to perceived threats to their understanding of place. Contrasting reactions to work inspired by a single influential international planner in disparate parts of the world help to illuminate the power of expertise in the immediate postwar period while demonstrating varying ways in which groups participating in planning processes mobilized emotion to voice their concerns and demand political action. The protest groups that formed after local governments acted on Gordon Stephenson’s advice in Perth and Halifax constituted what historian Barbara Rosenwein called emotional communities: “groups of people animated by common or similar interests, values, and emotional styles and valuations.”[24] The analysis reveals that some of these groups proved more successful than others in deploying emotions to address their concerns about urban change.

From the 1950s through the 1970s, modernist planning frequently polarized communities, with some people welcoming the new, while others bitterly opposed change. The cases here involve protest groups that erupted within a decade of each other in continents far apart. Although the stories differ in important ways—with one focusing on immediate community responses to environmental change and heritage destruction, while the other reports a simmering long-term dispute over racial discrimination—they share a legacy. Both cases were initiated through the redevelopment plans of eminent modernist British architect and town planner Gordon Stephenson, who practised in Britain, Australia, and Canada during his long career.

Stephenson trained as an architect at the University of Liverpool in the late 1920s. He subsequently won a postgraduate scholarship to study at the Institut d’Urbanisme at the University of Paris in 1930–2, where he worked in the modernist architect Le Corbusier’s atelier for a year. Returning to Britain, Stephenson lectured at the University of Liverpool, disseminating modernist ideas. After earning a master’s degree in city planning at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Stephenson returned to England, where he joined Lord Reith’s Reconstruction Group in the Ministry of Works and Building in 1941. He became a member of Patrick Abercrombie’s team working on the Greater London Plan of 1944 and planned Stevenage, Britain’s first postwar new town. Returning to the University of Liverpool in 1948 as Lever Professor of Civic Design, he modernized Liverpool’s curriculum and reinvigorated the Town Planning Review journal. In 1953 Stephenson began his international work, travelling to prepare a regional plan for Perth, capital of Western Australia. Taking up the position of foundation professor of planning at the University of Toronto in 1955, Stephenson conducted urban renewal studies in Halifax, Nova Scotia (1956–7), Kingston, Ontario (1958–60), London, Ontario (1960), and Ottawa (1958–66). In 1960, the University of Western Australia offered him the role of consultant architect on the expansion of its campus and the position of foundation professor for a new architecture program. Stephenson returned to Australia as an international authority on civic design and planning. In his university position, he was free to take on consultancy work and travelled extensively, designing university campuses throughout the world, working on a metropolitan strategy for Australia’s national capital, Canberra, and advising Australian state governments, until his retirement in the late 1980s. Describing himself as “compassionate” in later years, but operating in a consistently rational or scientific mode, Stephenson epitomized the postwar international planning expert who confidently disseminated modernist solutions wherever he went.[25]

Stephenson’s plan for Perth provided the underlying blueprint for the city’s development for more than fifty years. In it he proposed “reclamation” or obliteration of the Swan River’s Mounts Bay in order to construct a freeway. Stephenson’s study of Halifax, Nova Scotia, led local authorities to conclude that they should clear downtown slums and relocate an old community of African Canadians. In both cases, with the assistance of other experts, Stephenson applied modernist strategies and scientific studies to insist that particular kinds of changes served the “greater good.” Government authorities ignored evidence of emotional pain and dismissed community protests about loss of valued places and features as they applied their plans. They would allow neither community nor environmental concerns to delay “betterment” or progress. In Perth, local protest groups organized effectively to publicize their issues at the time: they saved part of a historical building but ultimately failed to prevent construction of a freeway and the destruction of the Mounts Bay river environment. In Halifax the residents of Africville began from a position of political weakness: a poor black community with limited voice to prevent its own destruction. Over four decades, however, the descendants of Africville drew on changing racial dynamics in Canada and beyond to strengthen their opposition and eventually earn reparations and an apology. Thus the cases illuminate some of the emotional histories of urban change generated in response to the modernist planning of a particular planning practitioner.

Mounts Bay: Legacy Lost

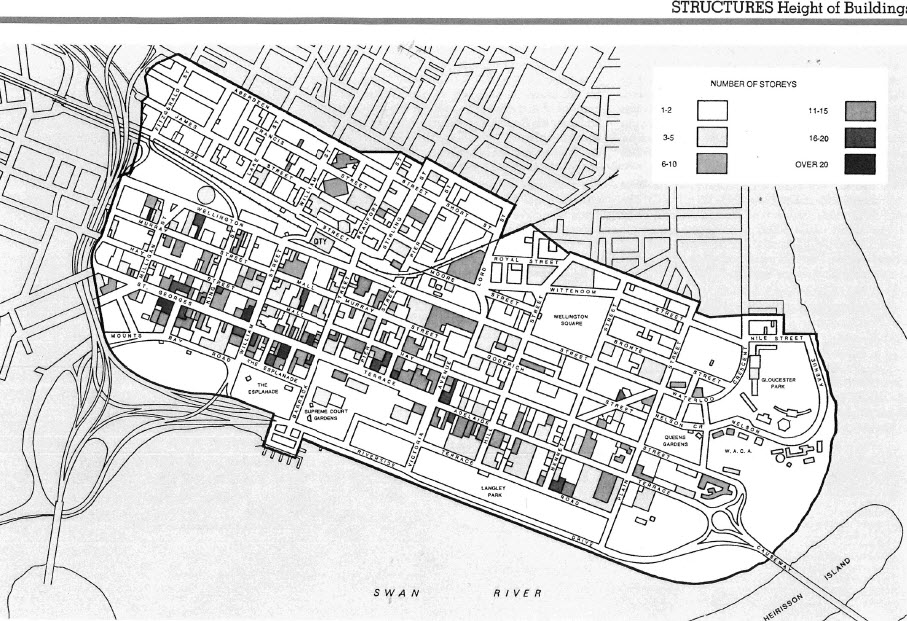

In the enthusiasm of postwar reconstruction, Australia seemed poised for big things.[26] One grand idea imported to Australia from the United States was the freeway system, as noted urban historian Graeme Davison observed.[27] Hence, when Perth brought in British town-planning expert Gordon Stephenson to prepare a plan for the metropolitan area, decision-makers offered little objection to the highways (freeways) and switch roads (interchanges) he proposed for the city. Road engineers, who had the technical know-how, heavily influenced Stephenson.[28] Freeways became the key means of providing access from the city centre to and between the centres of growth his plan proposed.[29] Building the freeway would necessitate reclamation of a section of the Swan River and demolition of one of the city’s historic buildings (figure 1).

In his report, Stephenson hinted at an emotional response as he recognized the Swan River’s importance: “The river, about which the Metropolitan Region has developed, provides a setting matched by very few cities in the world. Not only does its cool, blue expanse appear in delightful views from many points, but its waters also give infinite pleasure to thousands . . . It is in effect a vast and magnificent wedge of open space driving right into the heart of the metropolis.”[30]

As he planned the freeway, however, Stephenson coolly recommended obliterating Mounts Bay at the foot of the city. The bay, part of Perth Water in the Swan River, was once a fishing ground for the displaced Whadjuk Noongar people and was known as the city’s reflecting pool. Stephenson described the wide bay as merely “an expanse of shallow water which is more or less stagnant for a great part of the year.”[31] The bay and nearby historic buildings could be sacrificed to the needs of the motorist. Stephenson showed little sympathy for historic buildings that stood in the way of development. He proposed demolishing an “antiquated building”—the historic Barracks.[32] It blocked the view of Parliament House, which Stephenson argued would provide a more “fitting climax to the finest and most important street in the State”: the building also stood in the way of the planned freeway.[33]

Several protest groups developed in response to the freeway proposal. Three aspects of the development drew attention: river reclamation associated with the building of the bridge (1955–9); further river reclamation for the freeway interchange and a car park (1961–73); and demolition of the Barracks (1960–8). In 1955, the government announced it would build a bridge across the Narrows, the narrowest section of the river.[34] It would fill forty-three acres of Mounts Bay for an approach to the bridge. People quickly became concerned about the extent of reclamation. Letters to the editor of the morning daily newspaper revealed comments charged with emotion: anxiety, fear, dismay, indignation, or anger. In June 1955 the West Australian newspaper gave prominence to a half-page diatribe from an anonymous letter-writer, full of righteous indignation, headlining the story “‘Desecration’ in Regional Plan is Attacked”: “The despoliation of Perth Water on which the beauty and charm of the city so largely depends . . . is a sacrilege. The proposed cross-town road is contrary to elementary principles of city planning. The road is a grotesque compound of deep cuttings and costly bridges.”[35]

Figure 1

Map of the City of Perth and Mounts Bay showing the freeway interchange as built

The next day’s editorial asked, “Would it be possible to modify the reclamation scheme?”[36] A flurry of letters to the editor expressing anxiety and dismay followed. Typical was one that read, “One of the prettiest views of our city—the reflection of lights and signs in the curve of the bay . . . will soon be gone.”[37] The town planning commissioner (Stephenson’s collaborator) responded, arguing that there had been an exhaustive study by experts. While he admitted that “no-one will deny the first view of the tree-lined Mounts Bay foreshore is one of the most attractive parts of an approach to Perth,” he believed there was “no reason why the new foreshore line . . . should not be equally attractive.”[38] This did not deflect the ire of letter-writers who quickly moved to righteous anger, calling the plan “crude vandalism.”[39]

Blame was now apportioned as well-to-do residents expressed concern. Harold Boas, who lived in Cliff Street overlooking Mounts Bay and had been Perth’s inaugural town planning commissioner in the 1930s, proposed an alternative route. Commenting scathingly on the role of engineers, the government’s secrecy, and the exclusion of the public from the process of review, Boas wanted to “induce citizens to become conscious of the idea that, after all, the city is made for them and their enjoyment and that they shall not remain just pawns in the hands of bureaucracy.”[40] While many remained dismayed by the loss of “a beautiful reflecting pool and graceful sweep at the foot of Mount Eliza,”[41] filling continued, and the Narrows Bridge opened with great fanfare on 13 November 1959.[42]

Detailed planning for the interchange, to link the Narrows Bridge to the northern leg of the freeway, commenced in 1961 with the appointment of Chicago engineering consultants De Leuw Cather and Co. to prepare a new design. Geographer Martyn Webb argued that the engineers “turned Stephenson’s English Road system into a California Freeway system.”[43] Final plans for the interchange, involving a two-tier scheme and a further nineteen acres of reclamation, went before Parliament at the end of 1963. As the West Australian fulminated with a sense of outrage, “Parliament was used as a rubber stamp to meet the requirements of the engineering programme.”[44] With the release of details of the project, naming of the freeway after a former premier, and the claim by activists that the interchange was to be three-tier rather than two, protest escalated in early 1964.[45] The Sunday Times headlined rumours: “Freeway Secrets: Road Will Be 40 Ft. in Air.”[46]

The protest movement gathered strength as two committees were established. A citizens’ committee, which previously prevented development in Perth’s Kings Park, expanded activities to fight further river reclamation: the Citizens’ Committee for the Preservation of King’s Park and Swan River formed in January 1964.[47] Headed by Bessie Rischbieth, influential feminist and social activist at an international level, the committee brought formidable lobbying skills to apply to the cause. Committee members included Professor of Education Colsell Sanders, Director of Adult Education Hew Roberts, noted conservationist Vincent Serventy, as well as well-to-do members of Western Australia’s pioneering families. An influential supporter was Florence Hummerston, one of the few members of Perth City Council opposing river reclamation. Several leading citizens involved with the committee lived near the river in parts of the city that would be directly affected by construction. They lobbied through newspaper advertisements, press releases, flyers, packed public meetings, a television interview, petitions to Parliament, and ministerial delegations. Outrage permeated their missives: “Having taken 85 acres of Perth Water, which incidentally appears to be mainly for the purpose of taking traffic through Perth, it will be found that the car parking problem is insoluble—even if the whole of Perth water is made into one megalomaniac car park . . . Perth Water has been vandalized out of existence.∏[48]

A second protest group formed: the Swan River Preservation Committee, led by a retired businessman ex-major W. B. Garner.[49] Little is known of their members, though several featured in the West Australian’s social pages and one, Dr. R. D. McKellar, was a leading orthopedic surgeon. This committee, like the citizens’ committee, attracted the well-to-do and the well-educated. One submission to the premier, which they delivered in a deputation, noted that its petition had been signed by a large number of “reputable people.” They took the moral high ground in the submission, writing with righteous anger, “To claim that the removal of the shallows by the proposed reclamation work is in the interests of river beautification is sheer ‘eyewash’—the shallows and beaches form an essential part of the enjoyment and beauty of any river and are as essential as the water itself . . . let us not establish a bitumen and concrete barrier between the City and the very reason for its existence, the Swan River—an ugly memorial to those indifferent authorities whose one fetish is catering for the motor car in the cheapest possible way.”[50]

Despite its members’ social prominence and high emotion, the group’s deputation had no effect. The government announced that reclamation of the Swan River for the interchange would begin. It was expected to cost £4 million and included “six sweeping flyovers and bridges which will revolutionise the city’s traffic patterns.”[51]

A model of the proposed freeway went on public display. Hundreds of people inspected it. There was praise from expected quarters. Deputy Mayor Alf Curlewis, chairman of the city’s Town Planning Committee, thought it “a bold and wonderfully thought out plan,” and architect Harold Krantz found it “a first class solution to our problems . . . [that] could not have been better designed”. Bessie Rischbieth used more emotional terms to describe the freeway as “the rape of the river.”[52]

Once the extent of public antipathy became clear, political opinion began to shift, though too late to have much effect.[53] The Opposition said that the government’s intention to press on with reclamation showed “no respect for the strong public opinion” and urged that a special session of Parliament be called to reconsider the plans.[54] Protestors deluged the newspapers with letters reiterating their arguments, often couched in emotional terms. The state president of the Women’s Service Guilds, in a letter signed by twenty-two other women, wrote, “Criticism is rampant among almost every section of the community. No government dare ignore such a consensus of public opinion.”[55] The citizens’ committee held a packed meeting, at which Rischbieth declared passionately, “There are women on the warpath . . . We must not stop. We are going to win.”[56]

Despite the moral outrage and anger directed at the government, neither it nor the premier was moved.[57] Work on reclaiming a further nineteen acres of the Swan River for a car park began.[58] In a final flurry, emotional letters expressing anger, indignation, shame, and attachment to place came thick and fast: “All too soon our lovely views of the river will be obscured by a monstrous embankment, enclosing the city from the river like a prison wall. When visitors come from far away, we will have to hang our heads in shame for what has been done to our lovely river in the name of progress. No doubt in time the fine embankment will be embellished with a row of box trees, though I think weeping willows would be more appropriate.”[59]

Frustration, sadness, and resignation also became evident: “One gets weary of fighting a losing battle. How many have voiced their opinions about the Swan River only to be completely ignored?”[60] The emotional pull of the river, and residents’ deep attachment to place was clear. “The Premier . . . prefers to follow the advice of ‘world-renowned experts’ rather than that of Perth people. But has it occurred to him that these imported and ephemeral experts may not know, as Perth people do, that the Swan River is the soul of the city?”[61]

Figure 2

Bessie Rischbieth’s last stand

Rischbieth took a final stand: barefoot and defiant at the edge of the Swan River directly in the path of a truck dumping sand to fill the bay.[62] The photograph (figure 2) became an icon of protest in Perth, but her protest was to no avail.[63] After another six years of compaction and engineering works, the interchange opened on 30 November 1973.[64] The rationalists, inspired by Stephenson, carried the day. Drained of hope and means, the emotional community that had formed in opposition to the freeway dissolved into history.

Concern about the route of the western leg of the freeway had surfaced a decade earlier when it became clear that a deep cutting would slash through existing streets and destroy the historic Barracks (figure 3). The Barracks, built in 1866, accommodated the British Pensioner Guards who accompanied convicts to Western Australia. The building had been used for government offices since the late 1890s, with inexpensive temporary additions to accommodate increasing staff numbers. Despite its dilapidated rear sections, the Barracks remained imposing in the early 1960s. Its twin towers and mock Tudor battlements still spoke of the rule of law, as they had done nearly a hundred years earlier when they looked down on convict Perth.

Figure 3

The Barracks Archway with one wing gone and the other partially demolished, 10 June 1966

The Barracks embodied Western Australia’s British heritage as a penal settlement. Best-selling writer Dorothy Sanders tugged at the heart strings when she expressed the reaction of many to the threat of demolition through the voice of one of her heroines, a daughter of one of Perth’s old families: “West Australians could not explain to a man from abroad that the Barracks held a beauty for them he would never be able to see with foreign eyes. That building stood for their history, their birth pangs. As a nation they had not come trailing clouds of glory from some other world. Their primordial memory was one of discovery ships, pioneer ships, convict ships, immigrant ships. The Barracks, relic of the birth of a nation, reminded the citizens they were not born of privilege but of hardship, endurance and the will to survive.”[65]

Many West Australians vehemently opposed demolition of the Barracks.[66] The National Trust joined with the Royal Western Australian Historical Society (RWAHS) to present the premier with a petition containing 700 signatures to save the Barracks, but the government proved unresponsive. At a public meeting in 1961, five community groups joined the trust and the RWAHS to form the Barracks Defence Council (BDF). With many of its members already seasoned by earlier controversies, the BDF had considerable organizational skill, instituting a public opinion poll, organizing speakers and media publicity that resulted in extensive newspaper coverage. Accusing the government of acting like Big Brother, they printed pamphlets and stickers, raising the level of the debate and linking the political and the emotional by depicting the arch in silhouette flying a black banner emblazoned with the rallying cry “Preserve Democracy.”[67]

The impact of the BDF was such that, in early April 1963, its members received an invitation to a meeting of an interdepartmental government planning committee to consider the feasibility of retaining just the archway and the towers. Taking the high moral ground and rejecting the proposal, the BDF angrily demanded that at least two short sections of the wings be retained as well. Another petition to the premier followed, this time signed by 2,241 people.[68] The archway received a temporary reprieve from demolition as, in an exasperated attempt to defuse the situation, the premier announced, “Let [the archway] stand after the wings are gone so that the Government and the public can form a final opinion. I believe that thinking people, and those with some responsibility, will say that the archway must go.”[69]

The premier’s comments implicitly constructed those opposing improvements as irresponsible and emotional. Indeed, as the scheduled date for the demolition of the wings—March 1966—approached, emotions heated up again. The BDF attempted to organize a Sunday afternoon car rally through the city to protest demolition. The police refused permission.[70] Nevertheless, police stood by passively when more than two hundred university students stormed the Barracks, marching up St. George’s Terrace with placards reading “Improve the town—pull it down.”[71] Public opinion polling, however, showed 2,688 votes for retention and only 59 for demolition, leading the bishop of Perth to use highly charged emotional language in warning the government of the “mounting public opinion against the sacrifice of the Barracks on the altar of an engineering Moloch.”[72]

After demolition of the wings was complete, leaving the arch in front of the deep scar that marked the freeway works, the West Australian took a poll of passers-by to gauge public views. Apart from a disparaging comment from a taxi driver “on its own it looks like a pimple on a pumpkin,” most described considerable pride when they looked at the arch. “‘I hadn’t taken much notice of the Old Barracks till they took the wings away’ said a housewife, ‘Now I think the archway looks marvellous. It gives distinct character to this end of the terrace.’” “It reminds me of Paris’s Arc de Triomphe,” said a teenage schoolboy. Others described it as striking, mellow, picturesque, and elegant, declaring with satisfaction, “It is not a public nuisance. Posterity will thank us.”[73]

The pressure against demolition of the arch forced the government to commission a Gallup poll. Days before publication of its results, a local television station ran its own poll, which showed that 44 per cent favoured retention, 32 per cent favoured demolition, and 24 per cent remained undecided. A panel of experts discussed the results on television. They included Stephenson, who pronounced dispassionately that the arch had no place in the vista to Parliament House. But others, including Bishop Tom Riley, spoke of the archway’s emotional significance and historical attachments. Outspoken City Planner Paul Ritter, a seasoned media performer, engaged in histrionics when he threatened to jump from the top of the arch if they tried to pull it down. The premier was implacable.[74] When the results of the government-sponsored Gallup poll also showed most people against demolition, the premier put the issue to Parliament in a non-party vote in 1966. The crowded public gallery expressed relief, breaking into enthusiastic applause when, in a historic vote, Parliament rejected the premier’s motion to remove the arch.[75] Politicians were beginning to respond to the growing level of public passion in discussions about the future of the city.

As the Daily News in Perth explained, in an editorial headlined “Big Brother Rebuffed,” “The Barracks archway became a symbol. People tended to identify its planned destruction with so much of the recent casual scarring of the city in the name of progress—and, in a general sense, with governmental and departmental arrogance . . . Whatever the aesthetic value of the archway, it is to be hoped that the successful fight for its survival has taught the Government a lesson—that it cannot consistently act on the basis that Big Brother knows best.”[76]

On the face of it, the freeway development appeared to have fulfilled its intentions. Traffic now flows over the Narrows Bridge and streams off various interchange ramps along freeways, one through the chasm between Parliament House and the Barracks Arch. Mounts Bay lies largely forgotten, buried beneath the interchange by thousands of tons of sand, concrete, and bitumen. Yet those who shed tears and shouted slogans earned some victories. Although reduced to an arch alone, the Barracks still blocks the view to Parliament House and stands recognized for its heritage value. The arch was placed permanently on the Register of the Australian National Estate in 1978 and on the State Heritage Register in 2001. Part of its historic value came from its role as a symbol of “growing awareness of cultural heritage in Perth in the 1960s,” with its retention “a direct result of a groundswell of popular support and protest in the face of government proposals for demolition.”[77] The emotions the structure elicited underpinned the outpouring of community support that led to its retention, thus enhancing its historic merit.

What of the score-sheet for passionate protest versus modernist progress? Progress won in Perth. It was a powerful mantra of the era in a city in the grip of a development ethos and anxious to be seen as modern. Although fragments of the city’s built heritage survived the modernist onslaught, the riverine landscape was brutalized. Despite good organizational skills, effective publicity, and a powerful emotional campaign, the protest movement proved no match for those in authority and power, who pressed inexorably for rational modern solutions. Stephenson and the other international experts provided the scientific justifications political leaders heeded through much of the 1960s. In that context, residents’ emotional responses to threats to their sense of place had little hope of stalling progress.

Africville: A Wound That Won’t Heal

As modernist planning ideology rippled around the globe, cities reacted by planning freeways to move traffic more efficiently, but also by redeveloping older urban districts to enhance living conditions and economic growth. Like freeway planning, urban renewal typified the paternalistic, top-down approach of modernist planning and often resulted in public protest. In Halifax, Nova Scotia, urban renewal generated remarkably little protest during its first decade, even as a large area of the central city was cleared of its ramshackle housing, shops, and factories.[78] As clearance later moved to the north end of the peninsula, however, relocation generated lingering resentment and a range of powerful emotions that reshaped race relations in the city.

Africville, a small settlement on the shore of Bedford Basin in north Halifax, about six kilometres from the city centre, owed its origins to William Brown and William Arnold. These Black Loyalists from the United States arrived in Canada after the war of 1812 and purchased lots in 1848. Soon eight families of African descent lived in the area.[79] As the isolated community grew, some owners registered their deeds while others built homes in a pattern of informal settlement. Victorian disdain and racism left Africville socially and economically isolated.[80] Facilities that governments hesitated to locate near the heart of the city landed on Africville’s doorstep. Africville residents found themselves living near the slaughterhouse, prison, dump, infectious diseases hospital, and sewage pits. Their repeated requests for city services fell on deaf ears, leaving them with concerns about health, fire, and public order. Municipal plans in the 1940s designated Africville as industrial land. By 1954 the city manager recommended relocating the community, noting that it lacked services provided elsewhere, and the city needed the land for other purposes, including industry and a bridge to Dartmouth.[81]

In 1956 Halifax hired Gordon Stephenson—then a professor at the University of Toronto—to produce an urban renewal study.[82] Stephenson’s report provided the scientific basis for slum clearance in the city core.[83] His maps also identified social problems—such as households on public assistance (figure 4) and juveniles in trouble—in Africville. Despite the established history of the settlement, Stephenson described Africville as “an encampment, or shack town” of about seventy families, which needed to be rehoused.[84] He acknowledged the high rate of home ownership for black families there,[85] and his maps revealed the lack of police coverage.[86] In the paternalistic voice common in his era, Stephenson wrote, “Africville stands as an indictment of society and not of its inhabitants. They are old Canadians who have never had the opportunities enjoyed by their more fortunate fellows.”[87] Because council asked him to make specific recommendations only for central Halifax, however, Stephenson’s report did not suggest immediate action in Africville.

Figure 4

Map from Stephenson’s 1957 study showing households accepting social assistance

As clearance proceeded in central Halifax, local authorities and media began to ruminate on the “Africville problem.”[88] Pointing to Stephenson’s report as justification, a 1962 staff report described blighted housing and dilapidated structures in Africville, and identified the area as part of a future “industrial mile” along the Basin.[89] Planners proposed a waterfront freeway along the shore as part of the long-term plan to modernize the city.[90]

Early in the process Africville residents spoke out with pride to assert their rights to property ownership and freedom, and to oppose the dismantling of their community.[91] News reports of an August 1962 meeting, called by their elected provincial representative, described residents as “bitter” over city inaction to provide them with services; the reporter noted that many speakers rose to “blast city hall officials” for not issuing requested building permits.[92] Within weeks, however, divergent interests among residents and lack of unified leadership meant that non-Africville people became spokespersons for the community. Civil rights leader Alan Borovoy visited in August 1962 and encouraged residents to create a political alliance to promote their interests. The Halifax Human Rights Advisory Committee (HRAC) was soon formed, with three Africville residents among its ten unelected members.[93] Excluded from their traditional leadership roles, and feeling powerless to prevent the momentum of modernization, descendants of original families in Africville gradually seemed to become resigned to relocation.

The same year, Africville gained national notoriety. An article in the Toronto Globe and Mail condemned the racial segregation and blight evident in Halifax and urged council to move people from Africville for their own good.[94] A local paper covered a research study on Africville, describing the community as Halifax’s “number one embarrassment.”[95] A national reporter for Maclean’s magazine picked up the Africville thread in an article on racism in October 1962.[96] City council members took such critiques seriously, arguing that action to address Africville was 100 years overdue: “The recent article in Maclean’s made one feel like Halifax was being classified as a Mississippi situation.”[97] As coverage of segregation and civil rights grew in the United States, Halifax officials felt ashamed and embarrassed for delays in acting to resolve Africville, their own “social malignancy.”[98]

City council unanimously adopted a report urging removal of residents and demolition of homes in October 1962.[99] The black chairman of HRAC told council he was disappointed: “The impression the Africville people have of you is of a big white brother pushing the black children around, and they resent it.”[100] Resentment was building. In mid-1963 HRAC asked council to bring town-planning expert Albert Rose, who had been deeply involved in the Regent Park clearance scheme in Toronto, to Halifax to evaluate the situation. After spending two hours in Africville and meeting with a range of people, Rose “found it difficult to believe that a community existed” in this “slum.”[101] Rose urged the city to get on with relocation.[102] He opposed building a new community specifically for Africville residents nearby (as some had requested)[103] because of concerns over renewed segregation, and instead he argued for integrating them in public housing. A second nationally renowned expert in modern town planning had supported Stephenson’s advice on removal. Media support for clearance grew, with one article describing Africville as a shack town, shantytown, ghetto, blemish, and blot.[104] International media coverage, calling Halifax racist for failing to act on Africville, ultimately triggered council action.[105]

Between 1965 and 1970, residents were moved from Africville and homes were destroyed. Those with clear title received “market rate” compensation, while those without received $500 (an amount residents thought paltry for homes and independence lost). The relocation triggered bitterness, powerlessness, mistrust, and sadness among the black community. One resident explained, “People just didn’t trust each other. A lot of suspicion came along with the [relocation]. One [resident] was getting more than the other.”[106] Residents raised concerns about broken promises, the fairness of compensation, and appropriateness of new homes provided.[107] By contrast, self-congratulatory media reports gave the white community a sense of accomplishment at cleaning up “this dreary Negro ghetto”: “Soon Africville will be but a name. And, in the not too distant future that, too, mercifully will be forgotten.”[108] The tropes seen in media coverage of the period suggested that the city was helping folks who could not help themselves. Redevelopment of the city centre was offered as an exemplar of betterment that followed slum removal.

Despite the city’s efforts to portray clearance as progressive, the late 1960s brought black consciousness to Halifax. In 1968 Black Panthers visited the city, and in 1968–9 local residents established the Black United Front.[109] While their parents left Africville shedding quiet tears, the new generation angrily argued for fighting oppression and racism. After the 1970 Encounter on Urban Environment event—a public forum with invited experts diagnosing the ills of the city, including racism—former residents created the Africville Action Committee.[110] The release of the Africville Relocation Report in 1971[111] began to change the discourse about Africville by systematically identifying injustices with relocation.[112]

Three women, friends and former residents of the community, organized the Africville Genealogy Society in 1983, which began annual reunions on the site,[113] thereby creating a forum for debate about the fate of the community and a mechanism for defining and strengthening emotional responses to loss. Young professionals in the black community spoke out for recognition of the injustices committed in destroying Africville. The city created Seaview Park on the Africville site in June 1985, leading a former resident to say, “My heart is sad, yet joyful.”[114] Through the 1980s, coverage about Africville reflected divergent storytelling and growing emotional responses. On the one hand, mainstream authorities and media increasingly acknowledged that relocation was a mistake, suggesting that the “ghost of Africville” cast a menacing pall.[115] At a church service to commemorate residents’ loss a reporter heard, “We had freedom . . . We had no money, no work, but we got along fine.”[116] Annual reunions facilitated social bonding and storytelling about Africville. On the other hand, some opinion leaders in the city continued to hold that relocation was the right decision to overcome a racist history and to remove the “notorious Halifax ghetto.”[117] “Reviled by most Halifax residents as a blot on the city’s history, the memory of Africville is revered by many blacks as a vital part of their heritage,” a reporter noted. “Instead of being forgotten, the bleak slum has attained mythical status among people who once lived there.”[118] As the emotional memory of Africville intensified within the black community, whites felt a level of disquiet. A range of emotional communities had formed around the legacy of Africville: some remembered with regret and nostalgia, some with anger, and some with puzzlement.

Through the 1980s, resignation about loss turned increasingly into anger and resentment, especially for younger descendants of Africville. A black councillor affirmed, “You can’t ride roughshod over people . . . You can’t treat them as less than human.”[119] Stories about the relocation described the terrible crime the city committed on the people of Africville, taking everything that people valued, and forcing them onto welfare. Media reports often quoted descendants decrying the city’s deployment of garbage trucks to help people move and destruction of the church under cover of darkness as examples of shameful indignities visited on residents.[120] As perspectives on relocation shifted, former residents insisted Africville was vibrant, independent, and a great place to grow up. A former resident noted that residents “lost something . . . important—their community.”[121] Indignant agitation to remedy injustice grew.

A major exhibit and conference at Mount Saint Vincent University Art Gallery in 1989 provided a significant rallying point for changing the story. “Africville: The Spirit That Lives On” legitimized pride in the heritage of Africville, countering the city’s narrative that Africville was a slum.[122] The exhibit celebrated life in Africville: “Visitors writing in the guest-book speak of reliving memories or of new understanding of black anger or of white shame.”[123] Former residents remembered the church as the soul of the community. The political rhetoric of betterment through urban renewal began to yield to history reinterpreted.

While the exhibit went on national tour in 1990,[124] city officials continued to consider permitting service roads and industrial plans for the Africville site. Protests from the Africville Genealogy Society, pressing for return of the land or compensation for unfair expropriation, brought scathing rebukes from the mayor.[125] Descendants increasingly argued for protecting Africville as a heritage site. In late 1991 the province promised to spend $200,000 to build a replica of the church, leaving former residents elated. One reporter noted, “The black community in Halifax has won a major victory in its fight to preserve the site of Africville, a landmark many view as a monument to racism in Nova Scotia.”[126]

The release of the 1991 film Remember Africville,[127] along with a book in 1992,[128] intensified and focused emotions. In the documentary, former residents described a strong and vibrant community. Those who had promoted relocating residents articulated pained regret; they contextualized their choices in the modernist planning values dominating the era. Some saw themselves as enacting the 1957 Stephenson report, doing what was right to reduce segregation, and responding in expected ways to address concerns. By the 1990s press coverage often repeated the trope that the community was “relocated and bulldozed in the name of urban planning” or building bridges: a modernizing project.[129] Once justified by authorities as reducing segregation or enabling industrial development, the relocation now represented a disgraced planning paradigm and experts (such as Stephenson) who peddled it, while the community was defined as a site of heritage and culture.[130]

Annual reunions continued to build commitment to action and community as Africville became “a spirit, an icon, a metaphor, a home.”[131] Although the society reached a tentative deal with the city on land and an education fund in late 1994,[132] it subsequently sued the city in 1996 for compensation, an apology, and rebuilding of the church. By that time frustration with the city’s inaction encouraged the society to press its claims more forcefully, and negotiations continued through the early 2000s. Press coverage then typically described Africville as a tight-knit community, a heritage site, or a unique culture. Media articles often depicted clearance as evidence of racism and injustice; city officials rarely defended relocation. Having been fighting for action for almost two decades, representatives of the society used strong emotional language to make their points, calling the city’s actions degrading and insulting.[133] In 2001 they took their case to a United Nations conference against racism in South Africa, talking about the destruction of community, culture, and heritage.[134] The president of the society described Halifax as “probably one of the most racist cities in Canada.”[135]

In July 2002 the government of Canada recognized Africville as a national historic site and promised $2 million to help pay for a replica church.[136] Press coverage described the relocation as “one of the most severe episodes of racial discrimination in Canadian history,” and noted, “above all, Africville has become a symbol of the link between social well-being and community heritage for all Canadians.”[137] Heritage designation brought tears of joy and pride. A former resident of Africville told a reporter, “They tore our home from us, but they didn’t take our soul . . . they didn’t break us.”[138] Africville had been transformed from the experts’ story about a segregated slum to a community’s tale of redemption, triumph, and multiculturalism.

Despite promises from many levels of government, action on rebuilding the church and providing an apology languished. In 2004 a local paper reported, “Former Africville residents and their descendants accused city hall of racism and thievery, then demanded justice for their lost community during a raucous Grand Parade protest.”[139] International condemnation of the city[140] raised the stakes, and the emotions. It also highlighted cleavages within the black community, over community versus individual compensation.

Negotiations proceeded at a snail’s pace, with emotional claims of racism, “apartheid,”,[141] and “atrocities.”[142] Instead of framing displacement as a story of individual and community loss, or failed planning, the new narrative emplaced Africville within a historical legacy of systemic discrimination and injustice.[143] The raw emotions of loss, regret, and pain experienced by the first generation dispossessed at Africville ultimately gave way to indignation and disdain among the descendants. Leaders of the society dismissed earlier planning justifications, saying “the relocation had less to do with industry than being a racist act” as officials had “no intention of helping people.”[144] They focused on telling the story of Africville as a vibrant and “close-knit community that remains an indelible part of the city’s history.”[145]

In 2010, forty years after the relocation, the mayor issued a formal apology to former residents and their descendants and announced a funding package of $4.5 million from three levels of government.[146] In 2012 work finished on the rebuilt Africville Church and Museum, and the community celebrated its lost settlement (figure 5).[147]

Figure 5

Rebuilt Africville Church

The story of Africville involves competing black and white histories.[148] The black history of Africville began with independence, poverty, and exclusion. In the 1960s, residents presented their case as proud, law-abiding homeowners who requested municipal services to improve community quality and who wanted to keep their homes. By the 1970s their sad tale of dispossession, humiliation, financial distress, and powerlessness took a heavy toll. The 1980s brought a revolutionary story of struggle, the search for justice, and faith in community. The 1990s saw pride of heritage, effective political engagement, and demands for action begin to engender transformation. The final chapter, the 2000s, brought the African Nova Scotian community to open the rebuilt church in Africville and reassert symbolic ownership of the site, renamed Africville Park. Although the emotional pain of losing independence and pride of ownership may never disappear for former residents, pride in bringing the city to an apology and compensation has helped to strengthen the community of descendants.

The white history of Africville began with the legacy of slavery. Before the 1960s, whites saw Africville as a slum and shack town inhabited by ruffians.[149] Experts such as Stephenson and city officials described the site as future industrial land and the community as temporary. In the 1950s and 1960s planning experts provided statistics and maps that argued that Africville had to go. The (white) establishment saw itself as having the responsibility to overcome a legacy of terrible living conditions. Loo noted, “As much as Africville and its relocation were the outcome of longstanding racism, the decision to raze the community was also a manifestation of a set of ideas characteristic of a particular historical moment. Relocation was an outcome of the progressive politics of the late 1950s and early 1960s and the solutions they offered to inequality.”[150]

In the 1970s and 1980s media stories and staff reports identified success. By the 1990s, however, white histories of Africville began to acknowledge mistakes while claiming good intentions. In the 2000s, white histories admitted injustice while assuming responsibility to improve conditions, as decision-makers apologized and provided compensation. Emotional regimes shifted between shame and pride at different points in the story.

Over the course of these decades, white disdain for living conditions in Africville transformed first into pride in a clearance job accomplished, but subsequently into shame for having displaced disadvantaged people. Black shame about substandard living conditions in Africville transformed after relocation into pride in community and heritage, before ultimately into disdain for a political and social system that discriminated against African Nova Scotians. More than any other community in Nova Scotia, Africville has defined race relations and modernist planning mistakes. Its loss generated and reflected strong emotions. For those of African descent, it represented dispossession and generated sadness, anger, and resentment. At the same time, though, Africville came to signify identity, pride, perseverance, and cultural heritage. For planners and municipal officials, Africville triggered abject lessons: professional judgments framed by cultural expectations may not always stand the tests of history. Decisions supported by the best modernist planning strategies and experts of the 1950s and 1960s find themselves accused generations later of cultural destruction and racism.

Soul versus Science

The postwar planners had great faith in scientific methods and expert judgment as tools for transforming cities into more efficient and prosperous places. The modernist ideals of the era valued progress over tradition, community, and environment. Technocrats socially constructed urban transformation as logical, progressive, and visionary. Responses to the work of Gordon Stephenson only touch the surface of modernist town planning and the protests it generated, but they offer useful insights into the range of emotional responses that ensued as urban redevelopment proceeded. British and American planning and engineering experts provided the scientific arguments that decision-makers needed to modernize cities in Australia and Canada. In the public processes surrounding urban redevelopment in this period, authorities and those supporting development rallied around the expertise of planners such as Stephenson while dismissing the claims of those protesting change as emotional, irrational, unreasonable, and old-fashioned.

Although those promoting modernist development projected an aura of rationality, their statements reflected their pride in the potential for transformation. They framed the consultation and decision processes in ways that minimized the power of other emotions. Both cases show that emotions can affect political decisions. In Perth, during nearly twenty years of unsuccessful lobbying against river reclamation for the freeway, the emotional frenzy that was whipped up, and continued uneasiness amongst politicians over complete demolition of the adjacent Barracks resulted in a rare and historic parliamentary vote against a premier. The Halifax case similarly makes clear that emotions can play a role in authorities’ actions: embarrassment over international coverage reporting racial segregation and ghetto conditions in Africville strengthened the determination to relocate residents in the 1960s, while shame over allegations of systemic racism created the conditions for a reparations package and apology forty years later.

The cases profiled illustrate ways in which those protesting the building of freeways, the destruction of heritage, and the loss of community used passion tactically as they made their cases.[151] Much redevelopment occurred in Perth and Halifax before the era when concerted citizen action could stop bulldozers in their tracks. In these cases, disputes created opportunities for emotional communities to form and transform. When residents in Perth and Halifax spoke of the potential to lose the soul of the place, they sought to persuade decision-makers to change their choices. Protesters evoked emotional attachments to place and people as a mode of persuasion. At times they shed quiet tears of desperation; at times they angrily denounced injustice. Sometimes their emotions worked to influence outcomes; sometimes they had little effect. In Perth effective organization, an emotional campaign around community history and sense of place, and public support began to influence decisions only in the 1970s. In Halifax, emotions continued to affect outcomes through decades of lobbying.

Particular outcomes reflect the operation of many factors. Local events may mean that a road is built in one city while public opinion kills a project in another place. Key political interventions from groups, media, and individual leaders significantly influence decisions in ways that cannot easily be predicted. Global political contexts and the dominance of particular intellectual paradigms (such as modernism in the 1950s and 1960s) affect the choices people consider and then make. And of course timing matters, because it shapes the elements evaluated in any decision. Emotions related to environments, objects, and people affected by proposed changes enter the volatile mix.

The work of historians such as Rosenwein and Stearns, and sociologists such as Jasper, on the cultural role of emotions in history, provides valuable insights for the study of urban protest. While emotions can lend power to protest movements, the contexts within which protesters deploy emotions in protest movements reveal the unequal power relations in society that make success difficult for those challenging the interests of large-scale change.

Nevertheless, both cases discussed reflect the ways in which planning processes respond to transformations in power structures. As people resist oppression, decisions can shift. In Perth, saving the Barracks Arch resulted in large part from emotional interventions that involved reinterpreting the history of the city’s convict past to celebrate the structure as a legacy. Members of all three protest groups in Perth were well educated and from comfortable backgrounds, but the one group that drew on images of a disadvantaged past for emotional power ultimately had the greatest success. In Halifax, the descendants of Africville reclaimed their heritage by forcing authorities to acknowledge their emotional pain and address racism. Groups in Halifax harnessed the growing militancy and educational achievements of younger generations in service of claims for reparation. In both cases, emotions associated with protest played a significant role in acknowledging oppression, linking it with a history of struggle, and ultimately gaining group aims.

The residents of Africville received some measure of compensation for their losses, but Perth Water will never recover, and most of the Barracks is only history. Modernist planning wreaked havoc on many human and ecological communities that will never be restored. As for Gordon Stephenson, his legacy proves mixed. Stephenson was a planner of his times, consistently promoting urban redevelopment and improved living conditions in the cities he advised. It seems unlikely that he wished to cause the residents of Perth and Halifax the emotional pain that his advice ultimately produced, but it is equally clear that his recommendations had lasting implications not only on the built form of these cities but on those who live within them.

Parties annexes

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Victoria Prouse and Kate O’Shaughnessy for assistance with background research for this paper.

Biographical notes

Jenny Gregory is Winthrop Professor of History at the University of Western Australia. She has published widely on aspects of urban history and heritage. Her publications include City of Light: A History of Perth since the Fifties (2003) and the edited collections Seeking Wisdom: A Centenary History of the University of Western Australia (2013) and the Historical Encyclopedia of Western Australia as editor-in-chief (2009). Current projects include research into lost heritage places, their emotional legacy and their digital representation, and a study of the impact of British town planning on twentieth-century Australian cities. She has been head of the School of Humanities since 2009 and is director of UWA’s Centre for Western Australian History, was inaugural president of the History Council of WA (2001–6), and president and chair of the National Trust of Australia (WA) (1998–2010).

Jill L. Grant is professor of planning at Dalhousie University. Her research focuses on the planning of residential environments, urban development, and planning history. She is the author or editor of dozens of articles and five books, including Seeking Talent for Creative Cities (2014, University of Toronto Press), A Reader in Canadian Planning: Linking Theory and Practice (2008, Thomson Nelson), and Planning the Good Community: New Urbanism in Theory and Practice (2006, Routledge).

Notes

-

[1]

Gordon E. Cherry, Cities and Plans: The Shaping of Urban Britain in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries (London: Edward Arnold, 1988), 107.

-

[2]

Le Corbusier, The Radiant City, trans. Pamela Knight, Eleanor Levieux, and Derek Coltman (New York: Orion, 1967), 152.

-

[3]

James Q. Wilson, ed., Urban Renewal: The Record and the Controversy (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1966); Christopher Klemek, The Transatlantic Collapse of Urban Renewal: Postwar Urbanism from New York to Berlin (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011).

-

[4]

Early critiques include Jane Jacobs, The Death and Life of Great American Cities (New York: Penguin, 1961); Herbert Gans, “The Failure of Urban Renewal,” in Wilson, Urban Renewal, 537–57.

-

[5]

Hilary Ballon and Kenneth T. Jackson, eds., Robert Moses and the Modern City: The Transformation of New York (New York: W. W. Norton, 2007).

-

[6]

Klemek, Transatlantic Collapse of Urban Renewal.

-

[7]

Irwin Altman and Setha Low, Place Attachment (Human Behavior and Environment) (New York: Plenum, 1992).

-

[8]

Peter H. Marris, Loss and Change (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1986).

-

[9]

Peter Read, Returning to Nothing: The Meaning of Lost Places (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996).

-

[10]

Dolores Hayden, The Power of Place: Urban Landscapes as Public History (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1995), 9.

-

[11]

Tuan Yi-Fu, Space and Place: The Perspective of Experience (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1977), 6.

-

[12]

S. Dunant and R. Porter, eds., The Age of Anxiety (London: Virago, 1996), xi, cited in Sara Ahmed, The Cultural History of Emotions (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2004), 72.

-

[13]

Ahmed, Cultural History of Emotions, 11.

-

[14]

Ibid., 10.

-

[15]

Rachel C. Rieder, review of Ahmed, Cultural History of Emotions, in jac: An Online Journal of Rhetoric, Culture and Politics 26, nos. 3–4, 700–6.

-

[16]

F. G. Bailey, The Tactical Uses of Passion: An Essay on Power, Reason, and Reality (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1983).

-

[17]

Peter N. Stearns, “Emotions History in the United States: Goals, Methods, and Promise,” in Emotions in American History: An International Assessment, ed. Jessica C. E. Gienow-Hecht (New York: Berghahn Books, 2010), 23.

-

[18]

James M. Jasper, “Emotions of Protest: Affective and Reactive Emotions in and around Social Movements,” Sociological Forum 13, no. 3 (1998): 409–19. Jasper has written extensively on cultural approaches to the sociology of protest movements.

-

[19]

Ibid., 409, citing William A. Gamson, Talking Politics (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992).

-

[20]

Ibid., 415.

-

[21]

Ibid.

-

[22]

Ahmed, Cultural History of Emotions, 184.

-

[23]

Albert O. Hirschmann, Shifting Involvements (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1982), 102, cited by Jasper, “Emotions of Protest,” 419.

-

[24]

Barbara Rosenwein, qtd. in J. Plamper, “The History of Emotions: An Interview with William Reddy, Barbara Rosenwein, and Peter Stearns,” History and Theory 49 (2010): 253.

-

[25]

A special issue of Town Planning Review 83, no. 3 (2012), edited by David Gordon and Jenny Gregory, profiled the career of Gordon Stephenson. See also Gordon Stephenson, Compassionate Town Planning (Liverpool: University of Liverpool Press, 1994).

-

[26]

Ian Alexander, “The Post-war City,” in The Australian Metropolis: A Planning History, ed. Stephen Hamnett and Robert Freestone (St Leonards, NSW: Allen & Unwin, 2000), 99.

-

[27]

Herald, 22 May 1955, cited in Graeme Davison, Car Wars: How the Car Won Our Hearts and Conquered Our Cities (Crow’s Nest, NSW: Allen & Unwin, 2004), 75. The history of freeway development in Australia has received limited attention, in contrast to the United States, where, although protest movements against freeway development have been researched, the approach has tended to focus at the policy level. See, for example, Raymond A. Mohl. “The Interstates and the Cities: The U.S. Department of Transportation and the Freeway Revolt, 1966–1973,” Journal of Policy History 20, no. 2 (2008): 193–226; Raymond A. Mohl, “Stop the Road: Freeway Revolts in American Cities,” Journal of Urban History 30, no. 5 (2004): 674–706; Zachary M. Schrag, “The Freeway Fight in Washington, D.C.: The Three Sisters Bridge in Three Administrations,” Journal of Urban History 30, no. 5 (2004): 648–73.

-

[28]

Leigh Edmonds, The Vital Link:A History of Main Roads Western Australia 1926–1996 (Nedlands, WA: University of Western Australia Press, 1997), 135.

-

[29]

Gordon Stephenson and Alastair Hepburn, Plan for the Metropolitan Region: Perth and Fremantle Western Australia (Perth, WA: Government Printing Office, 1955), 117, 125, 175.

-

[30]

Ibid., 97.

-

[31]

Ibid., 117.

-

[32]

Ibid., 185.

-

[33]

Jenny Gregory, City of Light: A History of Perth since the 1950s (Perth, WA: City of Perth, 2003), 117–24.

-

[34]

West Australian, 9 April 1955.

-

[35]

West Australian, 20 June 1955.

-

[36]

West Australian, 21 June 1955.

-

[37]

West Australian, 27 June 1955.

-

[38]

West Australian, 9 July 1955

-

[39]

West Australian, 13 July 1955.

-

[40]

West Australian, 14 July 1955.

-

[41]

Rae Oldham and John Oldham, letter, West Australian, 21 May 1959; Andrea Witcomb and Kate Gregory, From the Barracks to the Burrup: The National Trust in Western Australia (Sydney: University of New South Wales Press, 2010), 86.

-

[42]

“The Narrows Bridge Opens Today,” West Australian, 13 November 1959.

-

[43]

Martyn Webb, interview with one of the authors, 2003.

-

[44]

West Australian, 31 December 1963.

-

[45]

Citizens’ Committee for the Preservation of King’s Park and Swan River (CCPKPSR), “An Historical Note, October 1965,” Swan River Reclamations (Perth: CCPKPSR, 1966), 5.

-

[46]

“Freeway Secrets: Road Will Be 40 Ft. in Air,” Sunday Times, 2 February 1964.

-

[47]

Handwritten news release, “ABC News,” 23 January 1964, CCPKPSR Papers, acc. 2552/16, MN 634, Battye Library (BL).

-

[48]

F. E. Lefroy, South Perth, letter, West Australian, ca. 30 January 1964, acc. 2552A/18, MN 634, BL.

-

[49]

Members of the Swan River Preservation Committee had written letters to the paper on the subject in 1959. Perth Daily News, 7 February 1964, acc. 2552A/18, MN 634, BL. (Both Perth and Halifax had papers that went simply by the title Daily News. The references therefore differentiate by city.)

-

[50]

Committee for Preservation of Swan River, deputation to premier, 17 February 1964. A photograph of the meeting appeared in the West Australian the following day.

-

[51]

West Australian, 20 February 1964.

-

[52]

Perth Daily News, 21 February 1964.

-

[53]

Phil McManus, “Your Car Is as Welcome as You Are: A History of Transportation and Planning in the Perth Metropolitan Region,” in Country: Visions of Land and People in Western Australia, ed. Andrea Gaynor, Mathew Trinca, and Anna Haebich (Perth: Western Australian Museum, 2002), 197.

-

[54]

West Australian, 21 March 1964.

-

[55]

West Australian, 20 March 1964

-

[56]

West Australian, 8 April 1964.

-

[57]

West Australian, 30 March 1964.

-

[58]

West Australian, 16 April 1964.

-

[59]

K. Elkington, Subiaco, “Embankment,” West Australian, 17 April 1964.

-

[60]

E. M. Cameron, Mt. Pleasant, “Losing Battle,” West Australian, 19 April 1964.

-

[61]

B. Reid, Nedlands, “Cars in the City,” West Australian, 19 April 1964.

-

[62]

Perth Daily News, 21 April 1964.

-

[63]

Perth Daily News, 23 April 1964.

-

[64]

Edmonds, Vital Link, 189.

-

[65]

Dorothy Lucie Sanders, Monday in Summer (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1961), 173.

-

[66]

Geoffrey Bolton, “The Good Name of Parliament,” in The House on the Hill, ed. David Black (Perth: Western Australian Parliamentary History Project, 1991); Gregory, City of Light, 117–24; Keryn Clark, “Barracks Arch,” in Historical Encyclopedia of Western Australia, eds Jenny Gregory and Jan Gothard, 121–2 (Crawley, WA: University of Western Australia Press, 2009); Witcomb and Gregory, From the Barracks to the Burrup, 238–46.

-

[67]

Mrs. Ray Oldham, honorary secretary, BDF, to Bessie Rischbieth, 27 June 1962, “Correspondence, Newspaper Cutting re the Preservation of Perth Barracks,” item 22, 1961–2, acc. 2552, Bessie Rischbieth Papers, MN 634/1, BL; and sticker, “Papers re Barracks Defence Council,” item 6, 1962, acc. 2425A, Bishop C. L. Riley Papers, MN 567, BL.

-

[68]

Bishop C. L. Riley to Premier David Brand, letter, 3 April 1963, Riley Papers.

-

[69]

West Australian, 9 April 1963.

-

[70]

“Police Ban Car-Rally Protest on Barracks”, unsourced newspaper cutting, 18 March 1966, Riley Papers.

-

[71]

West Australian, 26 March 1966.

-

[72]

Bishop C. L. Riley, president, BDF, public statement after BDF meeting, 24 March 1966, endorsed at special conference of member organizations on 5 April 1966, Riley Papers.

-

[73]

West Australian, 15 July 1966.

-

[74]

“TV Panel Divided over Archway” and “Survey Retain Arch”, unsourced newspaper cuttings, 4 October 1966, Riley Papers.

-

[75]

West Australian, 20 October 1966.

-

[76]

Perth Daily News, 20 October 1966.

-

[77]

Western Australian Register of Heritage Places, Barracks Arch Assessment Documentation, 22 June 2001.

-

[78]

Jill Grant, The Drama of Democracy: Contention and Dispute in Community Planning (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1994).

-

[79]

Donald Clairmont and Dennis Magill, Africville: The Life and Death of a Canadian Black Community, rev. ed. (Toronto: Canadian Scholars’ Press, 1987), 36.

-

[80]

Judith Fingard, Janet Guildford, and David Sutherland, Halifax: The First 250 Years (Halifax: Formac Publishing, 1999), 116.

-

[81]

Clairmont and Magill, Africville.

-

[82]

Gordon Stephenson, A Redevelopment Study of Halifax Nova Scotia (Halifax: Corporation of the City of Halifax, 1957).

-

[83]

Jill L. Grant and Marcus Paterson, “Scientific Cloak / Romantic Heart: Gordon Stephenson and the Redevelopment Study of Halifax, 1957,” Town Planning Review 83, no. 3 (2012): 319–36.

-

[84]

Stephenson, Redevelopment Study, 27. Nelson notes the incongruence in Stephenson’s labelling a community over a century old an “encampment.” Jennifer J. Nelson, “The Space of Africville: Creating, Regulating and Remembering the Urban ‘Slum,’” Canadian Journal of Law and Society 15, no. 2 (2000): 163–85.

-

[85]

Stephenson, Redevelopment Study, 32.

-

[86]

Ibid., 41.

-

[87]

Ibid., 27–8.

-

[88]

“Africville: Time for Action Is Now,” Halifax Mail Star (HMS), 23 December 1963.

-

[89]

Africville District Takeover Being Viewed as Necessity: Halifax Planning Board Considers Report Tuesday,” HMS, 1 August 1962.

-

[90]

Clairmont and Magill, Africville. The expressway was never built as the result of public opposition in the early 1970s.

-

[91]

B. A. Husband, “Proposal for Africville,” HMS, 11 August 1962.

-

[92]

“Residents Want to Keep Homes in Africville,” HMS, 9 August 1962.

-

[93]

Clairmont and Magill, Africville.

-

[94]

Mary Casey, “Africville Awaits the Wreckers,” Toronto Globe and Mail, 24 August 1962.

-

[95]

“Local Negroes Need Help: Far-sighted Policy Needed, Says Dalhousie Report,” HMS, 4 October 1962.

-

[96]

David Lewis Stein, “The Counterattack on Diehard Racism,” Maclean’s, 20 October 1962, 26–7, 91–3.

-

[97]

“Africville: Early Action Urged,” HMS, 25 October 1962.

-

[98]

“Africville: Time for Action Is Now.”

-

[99]

Clairmont and Magill, Africville.

-

[100]

“Africville: Early Action Urged.”

-

[101]

Clairmont and Magill, Africville, 140.

-

[102]

Loo argues that in selecting Rose the committee must have understood that this outcome was inevitable. Tina Loo, “Africville and the Dynamics of State Power in Postwar Canada,” Acadiensis 39, no. 2 (2010): 23–47.

-

[103]

B. A. Husbands, “Proposal for Africville,” HMS, 11 August 1962.

-

[104]

“Africville: Time for Action Is Now.”

-

[105]

Raymond Daniell, “Nova Scotia Hides a Racial Problem,” New York Times, 14 June 1964; Richard Bobier, “Africville: The Test of Urban Renewal and Race in Halifax, Nova Scotia,” Past Imperfect 4 (1995): 163–80.

-

[106]

Clairmont and Magill, Africville, 162.

-

[107]

Ibid.

-

[108]

“End of Africville,” HMS, 7 July 1967.

-

[109]

“Black History of Nova Scotia: A Chronology of Events,” Halifax Public Libraries, 2013, http://www.halifaxpubliclibraries.ca/ahmonth/timelines/bhns.html.

-

[110]

Fingard et al., Halifax, 175–7.

-

[111]

Donald Clairmont and Dennis William Magill, Africville Relocation Report (Halifax: Institute of Public Affairs, Dalhousie University, 1971).

-

[112]