Résumés

Abstract

Between the mid-1970s and the mid-1980s there was a wave of citizen-initiated preservation activity in Washington, DC, much of it directed towards identifying and expanding neighbourhood historic districts. These efforts were driven by several different events and influences that coalesced in the period: a new sense of local control that came with the establishment of municipal self-government in the District of Columbia after 1975; the expectation that a comprehensive historic preservation law would be enacted in the district; the U.S. Supreme Court’s affirmation of the legality of preservation controls in 1978; and the renewed salience of the idea of place that affected everything from community art and neighbourhood activism to urban design and architectural theory. This paper addresses this moment of intense activity by investigating the ways in which preservation advocates in one neighbourhood, Dupont Circle, sought to expand their historic district. The proposal to add several square miles of new territory to the designated historic area was led by a predominantly white preservation organization, the Dupont Circle Conservancy. The proposal aroused significant opposition from a group calling itself the 14th and U Street Coalition, which styled itself as the representative of African-American interests and historical identity in neighbouring Shaw. They protested that the Dupont Circle preservationists were attempting to annex their neighbourhood and with it, their history. At first glance this conflict appears to be a predictable case of inner city gentrification fought along the lines of racial identity. But when examined more carefully, the series of claims and counter-claims embedded in the conflict exposed a more nuanced set of issues related to skin tone, class, and historical entitlement. The conflict highlighted the absence of any agreement about what constituted the historicity of such a historic area and cast doubt over who might be qualified speak on behalf of the history contained in such an area.

Résumé

Entre les années 1970 et 1980, la ville de Washington, DC, est l’objet d’un mouvement en faveur de la préservation du patrimoine bâti initié par des citoyens. Ces derniers réclament l’agrandissement des secteurs patrimoniaux protégés. Différents évènements et circonstances incitent les groupes de citoyens à unir leurs efforts au cours de cette période : une nouvelle perception de contrôle local qui émerge avec l’établissement du gouvernement municipal du District de Columbia à partir 1975, de nouvelles attentes quant au fait que la municipalité doive élaborer des règlements extensifs touchant à la préservation du patrimoine, l’affirmation en 1978 de la légalité des lois de conservation par la Cour suprême des États-Unis et la montée en puissance que la notion de l’esprit du lieu a eu des répercussions en ce qui à l’art communautaire, à l’activisme, au design urbain et à la théorie architecturale. Cet article se concentre sur cette période d’activité intense en examinant comment les partisans de la conservation patrimoniale de Dupont Circle ont tenté d’agrandir le territoire protégé de ce quartier. La proposition pour l’agrandissement substantiel de la zone historique a été menée par un groupe, le Dupont Circle Conservancy, composé principalement de blancs. Elle a été fortement contestée par un groupe se nommant le 14th and U Street Coalition et qui se disait être le représentant des intérêts afro-américains et de l’identité historique du quartier voisin Shaw. Selon ce groupe, les protagonistes de la préservation de Dupont Circle cherchaient à annexer leur quartier, et, en même temps, leur histoire. À première vue, il appert que cet exemple représente un cas prévisible de lutte raciale causée par l’embourgeoisement d’un quartier urbain central. Or, une analyse plus approfondie montre que cet évènement implique une série de requêtes démontrant des nuances ayant trait à la couleur de la peau, la classe sociale et les revendications historiques. Ce conflit a surtout fait ressortir l’absence de tout consensus sur la signification même de l’intérêt historique du quartier et a mis en question la légitimité de ceux qui se sont exprimés sur la valeur historique du secteur.

Corps de l’article

Introduction

Who decides what is historically significant in the urban environment? In theory, anyone is entitled to stake a claim, to say that my house, our church, these streets are worthy of preservation as a significant place. In the United States, for example, anyone can prepare a nomination for the National Register of Historic Places. In practice, however, as preservation historian Randall Mason has acknowledged, assessing the significance of a place is a complicated undertaking and one that has been controlled largely by preservation, planning, and design professionals, who have overseen a growing professional apparatus for historic preservation in the United States since the 1960s. But despite the fact that expert control of the process of identifying historic significance in the built environment is the norm, the idea that an expert can adjudicate such claims according to objective criteria is difficult to sustain. As critical, historical research on the development of historic preservation has advanced in recent years, it has become ever clearer that in practice a designation of historic significance is never purely the result of careful inspection of the place itself. Rather, such designations are also the products of the various regimes of assessment and evaluation that affect the cultural perception of place in the broadest sense. Such perceptions are inextricably tied to social codes and patterns of judgment that cannot be addressed by reference to given criteria of significance and the immanent qualities of a building or district. Consequently, assessments of significance are often contested.[1]

The difficulties are compounded when an ensemble of buildings, a precinct, landscape, or district, not simply a significant individual building, is assessed for its historic significance. Where are the boundaries of the significant place? How can those boundaries be justified? Who should be consulted about them? Who makes the final decision? Whose history is represented by what is enclosed within those boundaries? And does that history belong, in some sense, to the present-day advocates for preserving that place? In the United States there is a significant “how to” literature dedicated to addressing some of these questions. This literature teaches advocates and consultants how to compile the evidence on behalf of a proposal, match it to the established criteria, and allow the assessment process to run its course. But, generally speaking, advocates and preservation professionals who have taken responsibility for making these assessments have not articulated the regimes of evaluation and authority that lie behind a statement of significance. This is not their job. In some cases, however, the conflict aroused by a particular effort to preserve a place brings such questions of cultural authority and historical entitlement unavoidably into focus.[2]

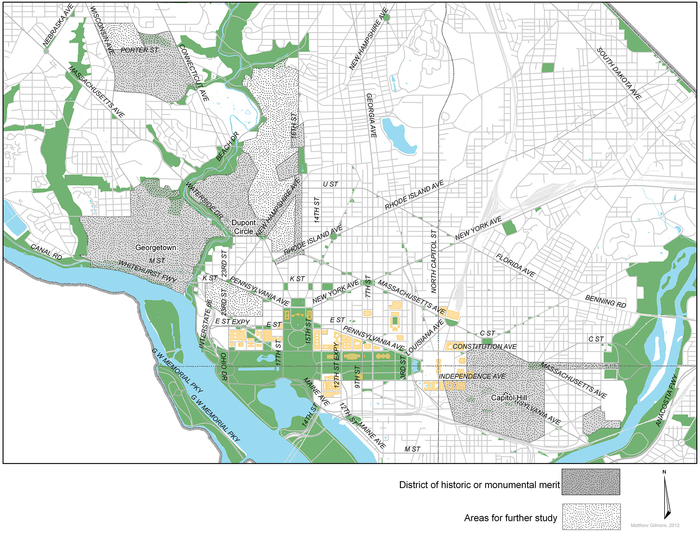

Such was the case in Washington, DC, in the late 1970s and early 1980s as preservation advocates in the Dupont Circle neighbourhood attempted to enlarge, by a significant degree, the historic district in their area. The attempt was part of a larger, loosely co-ordinated effort by neighbourhood organizations, restoration societies, and preservation advocates in the period, to define much of the inner city, residential landscape in Washington as historically significant (see figure 1). Energies in this period were focused in particular on the Victorian cityscape.[3] The groups that were behind this effort implicitly made a claim on behalf of the value of Washington’s intown neighbourhoods as a shared, culturally enriching resource. Such values were opposed to the narrowly pecuniary interests of certain property owners and developers who, preservationists argued, sought to exploit urban intensification and changing patterns of land use for their private benefit. As the city’s first citizen-based, citywide preservation advocacy group Don’t Tear It Down rhetorically asked in their first newsletter in 1971, “citizen” or “developer$”?[4]

Figure 1

Washington, DC, showing historic districts, 2012. Twenty-eight are neighbourhood districts, and most of these form part of an arc of such districts stretching from Georgetown in the northwest quadrant to Anacostia in the southeast.

As it turned out, though, Dupont Circle preservation advocates antagonized not just propertied interests, as they expected and intended, but also a substantial group of citizen-activists in neighbouring Shaw, represented by an organization calling itself the 14th and U Street Coalition. This group of African-American residents and business owners challenged the right of the predominantly white preservation and neighbourhood groups from Dupont Circle to determine the shape and significance of a historic district that would include substantial sections of the area that many believed to be clearly within the historically black, Shaw neighbourhood. The proposed historic district expansion brought to the surface competing visions and claims about the meanings and entitlements of the historic urban environment. Such competing claims about who could define the scope of historic significance in the area, and to what end, complicated the idea that there was a simple public interest in the past.

This conflict about historic district protections and who might define them was particularly resonant in Washington, DC, for two reasons. First, in the 1970s and early 1980s, the period during which this conflict unfolded, the question of how Washington, DC, should be governed and by whom was a question of lively interest. With a newly acquired set of entitlements related to municipal “home rule,” inhabitants of the city were anxious to explore the ways in which they could exercise some control over decision-making that affected their daily lives. Second, Washington’s “intown” areas were home to one of the nation’s most active housing restoration trends by the 1960s. During the 1970s and 1980s that interest in restoring individual dwellings was translated into a wider ambition to preserve the scale and historic character of the nineteenth-century city. Historic districts were the key to this process, and their designation in Washington was more expansive than in any other major city in the United States during the same period. Therefore, to understand the contretemps surrounding historic district designations, which did not amount to overt racial or class conflict, but were much more than the bickering of unhappy neighbours, requires an understanding of how the housing restoration trend in the inner city paved the way for historic preservation and foreshadowed its racial tensions.[5]

Restoration

In the 1960s and 1970s, many U.S. cities were in the grip of what has widely been identified as an “urban crisis.” Yet, in the midst of this, there emerged a significant grassroots effort to revive urban neighbourhoods. This revival was based on a variety of forms of neighbourhood activism, but unquestionably the most influential factor was the trend to restore old houses in central city areas. This “back to the city trend,” called “brownstoning” in New York and “urban pioneering” or simply the “restoration trend” elsewhere, has recently attracted the interest of historians. Sulieman Osman’s Brownstone Brooklyn, for example, uncovered some of the deeper historical sources of the restoration trend missed by social scientists who have been studying gentrification since the 1980s. But historic preservation itself has not, so far, been accorded due recognition within this process by urban historians or social scientists. Within the preservation discourse, knowledge of successful efforts in Charleston and New Orleans in the 1920s and 1930s and the innovative regeneration program in the College Hill neighbourhood of Providence, Rhode Island, are well known. But urban historians have not acknowledged that historic preservation, especially historic district designation, was the main method by which restoration groups attempted to secure their investment—cultural and community, as well as financial—against the more intensive real estate investment and redevelopment activity that their restoration efforts often catalyzed.[6]

In Washington, DC, Georgetown is the acknowledged place of origin of the restoration culture, with activity to repair historic houses and protect the scale and character of the streetscapes underway as early as the 1920s. But by the 1960s the Capitol Hill neighbourhoods, immediately to the east of the U.S. Capitol, and Dupont Circle, in the inner northwest, at the edge of the city’s commercial centre, had become the places where restoration activity was most intense (figure 2). Both areas were popular with those who wished to restore houses, as they possessed strong locational advantages as well as an appealing stock of relatively affordable row housing. Analysis of census tract data from the 1970s and 1980s by housing researcher Frank H. Wilson has revealed several demographic trends associated with this restoration process. But in general terms his and other work from the period demonstrates that small households of white homeowners were obtaining properties that had formerly been inhabited by larger households of mostly black renters.[7]

Figure 2

On the left of the cover of the 1924 pamphlet The Future of Georgetown, which advocated for the protection of existing streetscapes, residential scale, and use. On the right is the cover of the pamphlet for the 1963 Capitol Hill Restoration Society house and garden tour.

During the late 1960s concerns about displacement caused by restoration activities in Washington surfaced in the press.[8] A racially charged critique of the restoration movement took aim at an apparent misappropriation of the economic value of inner city property. One inner city Washington neighbourhood group, the Capitol East Community Organization (CECO), an umbrella group that advocated for the needs and interests of the area’s African Americans, garnered national attention for its attack on the restoration movement. The director of the organization, Linwood Chatman, described the agents of the restoration movement in the real estate business as “scavengers” and claimed that black renters had already been “flushed out” of restoration areas.[9] Sam Smith, the activist editor of the neighbourhood newspaper the East Capitol Gazette supported this critique and was quoted as saying that the restoration movement was “strip mining” the area and that it was, in effect, a major impediment to social justice aims. “Exploiters moved in quickly,” he said, “made a fast buck, and drove out blacks in an attempt to fashion another Georgetown.”[10]

Some recognition of this problem amongst the restoration advocates themselves was evident in local newspaper reports as early as 1965, and in 1967 the Capitol Hill Restoration Society openly acknowledged the potential negative consequences of restoration for long-standing, renting populations.[11] But for the most part, liberal, middle-class whites were aggrieved by criticism of the restoration movement. Phillip Ridgely’s letter to the editor of the national magazine City, where an in-depth article detailing this conflict was published in its August–September issue of 1970, forcefully represented the restorationist perspective. Ridgley described CECO and Sam Smith as “bomb-throwers” who “have accomplished nothing for the community, black or white.” He went on to describe his own position: “I have been resident on the Hill since 1964 and find that it is probably the most liberal group in the metropolitan area. That’s why I get so disgusted when I read articles about those who have done so much to renew this urban area, depicted as some sort of white conspiracy.”[12]

The difficulty for self-conscious liberals such as Ridgely was in accepting that their good intentions might have negative consequences, foreseeable or not. Conversely, critics of the restoration movement sought to identify villains rather than the structural, economic forces and the emerging patterns of cultural taste that were driving change.

The sense of mutual incomprehension exposed by this exchange seems to have inspired a more inclusive approach to historic preservation in Capitol Hill in the 1970s. However, the lessons learned by Capitol Hill preservationists did not have the same impact over in Dupont Circle. There, the uncertainty of white preservationists about the relevance of race to the historic significance and historic preservation action generally, resulted in a prolonged dispute with their neighbours in Shaw.

To understand that dispute also requires some comprehension of the wider events that shaped the field of historic preservation as a whole during these years and the changes underway in local politics in Washington at the time. Three events, all concentrated in 1978, provide the context for the dispute about the expansion of the Dupont Circle Historic District: the U.S. Supreme Court’s Penn Central decision regarding the validity of New York City’s historic landmarks law; the passage of a comprehensive historic preservation law in Washington, DC; and the election of Marion Barry as Washington mayor.

Local Politics and Preservation Law

In June 1978 the United States Supreme Court settled a decade-long dispute between New York City and Penn Central Transportation over the fate of the Grand Central Terminal. The majority opinion in the case found that New York City’s Landmarks Law was valid and did not enable the “taking” of property as the appellants suggested. The decision underlined the legitimacy of historic landmarks laws nationally by confirming that such legislation could reasonably be expected to serve the public good and propelled historic preservation into a new phase of legal certainty and political confidence.[13]

One of the attorneys for the amici curiae in the Penn Central Supreme Court case was David Bonderman. Within months of his successful involvement in that case Bonderman was intimately involved in drafting the language for a D.C. historic preservation law, DC Law 2-144. It is hardly surprising, therefore, that when the DC City Council passed a historic preservation bill in November 1978 it conformed closely to the principles outlined in the Supreme Court decision. Consequently, when it came into effect the following year, the result was one of the most robust historic preservation laws in the country. The intention of the law was to provide meaningful legal protection for all historic districts and landmarks in the District of Columbia. This expansive set of new municipal preservation protections buoyed the efforts of many of the neighbourhood associations, who were at that time looking to designate or expand historic districts in anticipation of just this kind of law.[14]

In the very same month that the council passed the historic preservation bill, Marion Barry was elected mayor of Washington, giving the city its first executive with a strong, local political base since Alexander “Boss” Shepherd in the 1870s. For most of its history the District of Columbia—originally known as the federal territory—was governed by the U.S. Congress. While several different systems of government operated during the nineteenth century, efforts to revive some form of local government were slow to develop during the twentieth century. Bills to establish municipal self-government were introduced to Congress several times between 1948 and 1966, and the campaign for “home rule” was ongoing during the postwar decades. But it was not until 1973 that Congress finally passed the District of Columbia Home Rule Act. Walter Washington was the first elected mayor after the passage of the act, but he faced no significant opposition when he stood for the position in 1974. It was only after he stepped down that a serious political campaign was mounted for the office. This brought new forces into view and exposed divisions among Washington voters that had been papered over by the energy invested in the campaign to achieve “home rule.”[15]

Marion Barry had carefully built political support in the city for more than a decade, but his supporters could not be characterized easily. He garnered votes from affluent, predominantly white wards west of Rock Creek Park, as well as those of some of the city’s poorest residents in areas with high concentrations of African Americans east of the Anacostia River. Where most of the black elite stood behind Sterling Tucker, Walter Washington’s anointed successor, Barry had run as a coalition-builder and reformer, winning sympathy from a constituency that felt little connection with the city’s black middle class, the group who were widely seen as the natural source of municipal, political authority.[16]

Barry’s election as mayor provided a sense of confidence for the white, middle-class activists who led the “intown” restoration and preservation groups. Under Barry’s leadership, they believed, Washington’s local government would now be responsive to local interests and a broad range of democratically oriented positions. The sense of expectation among poor, inner-city blacks was greater still. Barry had positioned himself as their champion and now faced a series of demands that included economic justice, political empowerment, and cultural liberation. As Howard Gillette has written, Barry’s “victory sent a mixed message. Identified with the causes closest to the black power movement, he had nonetheless made himself acceptable to whites.”[17]

The conflict that emerged about the proper extent of the Dupont Circle Historic District in the early 1980s saw representatives of the two main groups within Barry’s constituency lined up against one another. On one side were the liberal, white, middle-class “intowners,” who formed the rump of the restoration culture, and on the other, inner-city blacks of very modest means, who looked to Barry for economic empowerment and political self-determination. Preservation politics in the period reflected these contradictions and tensions within Barry’s constituency. The home rule campaign had brought disparate groups together to fight for a common aim and take control of city government and the urban environment. Preservation likewise promised a mechanism for grassroots control of decision-making. In both cases insensitive and impersonal forces—the federal government and private developers—were common enemies to rally against. But the detail of designating historic districts, just like the priorities and preferences of local government itself, eroded the goodwill and sense of common purpose that had underpinned earlier support for general principles.

Historic Districts

Notwithstanding the racial tension that had arisen in Capitol Hill in the late 1960s and the civil unrest that rocked Washington in the wake of Martin Luther King’s assassination in April 1968, the restoration process continued strongly in the 1970s, resulting in increased efforts to designate and expand historic districts. Groups such as the Capitol Hill Restoration Society (CHRS) and the Dupont Circle Citizens Association (DCCA) saw a need to ensure aesthetic and economic investments that had been made by “pioneers” in areas of restored housing would not be eroded by piecemeal redevelopment. This led them to look to historic preservation protections where previously they had focused mostly on zoning as a means of preventing undesirable change, especially the shift towards higher densities associated with multi-unit apartment buildings.[18]

The neighbourhood groups did not have to begin from scratch. In 1964 an expert committee, called the Joint Committee on Landmarks (JCL), had defined the city’s key historical resources and suggested a number of historic districts be designated (figure 3). But the list and map of historic places that they created at that time remained indicative only, a guide for planning. A decade on, with widespread expectation that municipal home rule would lead to the passage of a comprehensive local preservation law, citizens’ groups representing intown residential areas began to examine how preservation laws might help protect their areas from unwanted demolitions and redevelopment projects. For such groups, the obvious implication of a local preservation law was that it would give strong legal standing to historic district designations. In such districts, historic significance was designated by reference to the pattern and ensemble rather than by reference to individually significant buildings. They thus enabled neighbourhood-scale protections, without the need to demonstrate the architectural significance of each individual item within the district. Legally enforceable historic district controls would thus give local citizens groups and restoration societies greatly increased power to control the rate and character of change in their neighbourhoods.[19]

Figure 3

Redrawing of the Joint Committee on Landmarks’ 1964 map of “ districts of historic or monumental merit.” Comparisons to the present historic district map reveal substantial similarities, with the notable exception that the 1964 suggestions for historic areas completely ignored the area between 16th Street North West and Capitol Hill.

The two areas where the most ambitious historic district expansions were proposed in Washington in the 1970s were the same two where restoration activity had been most prolific in the period immediately prior: Capitol Hill and Dupont Circle. The expansion proposals were led by the Capitol Hill Restoration Society and the Dupont Circle Citizens Association respectively and were viewed as a natural extension of earlier efforts to publicize restoration activity.

The process each area went through to delineate larger historic districts was contrasting. The Capitol Hill group worked closely with the District of Columbia’s Historic Preservation Office (HPO), and the boundaries it proposed were accepted and designated without controversy. Their nomination reflected some sensitivity to the issues of race and class, an understandable reaction perhaps to lessons learned back in the 1960s, when they were publicly maligned for promoting the displacement of poor blacks. The district nomination evinced a confident and knowledgeable tone when it came to African-American history. It acknowledged a substantial African-American population living and worshiping in the area in the nineteenth century, quoting local historian Letitia Brown, who observed, “By 1860, Negroes were scattered throughout the southeast quarter from South Capitol to 11th St East.”[20] The historical description also highlighted the preponderance of “modest housing” in the area inhabited by “middle class governmental workers” who formed “a solid community” that “supported a growing number of small commercial establishments.”[21] In other words, the nomination made it very clear that the historic district bid was not an attempt to “fashion another Georgetown,” as Sam Smith had accused in 1968. The nomination signalled that the Capitol Hill Historic District was not intended as an elite enclave of preserved magnificence. Rather, the document explicitly argued for an idea of the Capitol Hill area as encompassing significant racial and class diversity and generally modest pattern of residential buildings. The impression left by the nomination as a whole was that the area’s history was characterized by an overall harmony, but one that encompassed a substantial variety, much as the built fabric achieved a harmony of scale and rhythm out of a variety of styles and types of façade expression.

Certainly the Capitol Hill nomination lacked any detailed discussion of how race influenced patterns of dwelling, or how restoration activity might have affected Capitol Hill’s racial and class composition. Nowhere was reference made to racial tensions or the expression of racial hierarchy in the organization of space in the area. But in this it was a quintessential document of the moment of supposed social consensus fostered by the bicentennial preparations and celebrations. The nomination was researched and written in the period between 1974 and 1976, and submitted in July 1976, and reflected the sanctioned, multicultural narrative that informed the civic production of bicentennial history. It told a story of different peoples coming to share the same space and seemed to suggest the possibility that their interests could all be pursued and harmonized in that space.[22]

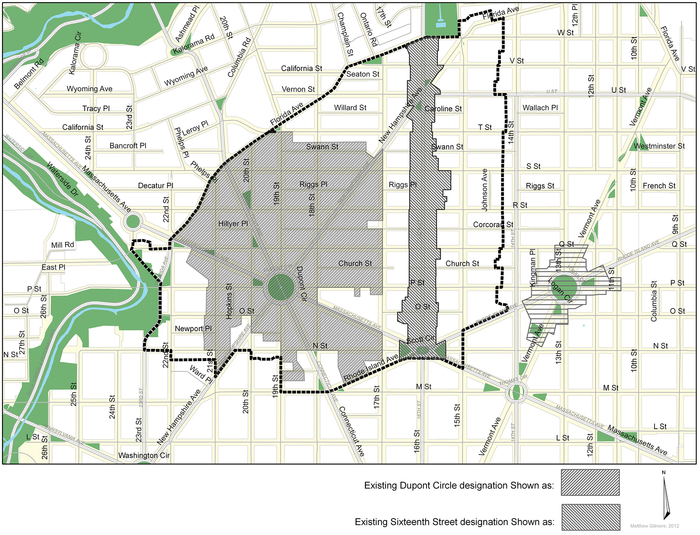

Preservationists in Dupont Circle embarked on a similar expansion effort in 1977, following the successful Capitol Hill bid (figure 4). But the sense of control over the interpretation of the area’s history was much less certain, and it lacked the ideological coherency reflected in the Capitol Hill nomination. The Dupont Circle Citizens Association did not collaborate with the city’s preservation office in preparing the nomination, but perhaps more importantly they focused on a quite different sense of historic significance. Their historic district nomination, which would have trebled the area inside the district, was prepared by Ronald Alvarez, who was a member of the Victorian Society of America and styled himself more as an architectural connoisseur than a historian. While progressive, or at least inclusive, at the level of architectural taste, the Alvarez nomination focused mostly on physical qualities and architectural resources in the proposed district and made only a few halting references to social patterns in life of the area. While the Dupont Circle proponents no doubt saw the lack of reference to race as a way of avoiding seemingly arbitrary social distinctions, it was a slightly anachronistic stance, given the focus on African-American history and culture in the period. Moreover, despite the apparent high-mindedness of attempting to relegate racial distinctions to the past, it ignored the powerful influence of racially restrictive covenants that had powerfully shaped dwelling patterns in the areas to the east of Dupont Circle, even well after the Shelley vs. Kramer Supreme Court decision had made it illegal to enforce such covenants.[23]

Figure 4

The DCCA did double the size of the existing historic district, but the city’s planners nevertheless sheared substantial sections from the original proposal when they submitted their report to the landmarks committee, who would adjudicate on the application and make the final decision about the boundaries of the district. The planners recommended that fewer blocks be included to the north, east, and south, and that a separate historic district be created on 16th Street. In so doing they recognized substantive justification for the expansion but disagreed with all of the boundaries suggested by the Alvarez-DCCA nomination except those drawn on the basis of topography. The largest section to be excluded was in the northeast corner of the proposed area. The city’s planning and preservation officials explicitly denied the claim that this part of the city belonged in Dupont Circle. Physically they pointed to a number of discordant elements in this section of the proposed district that made it heterogeneous with the rest of the historic district, but most importantly they argued that the blocks above Swann Street had never widely been considered to be part of Dupont Circle by local people.[24]

The 1977 Preservation Office staff report, which recommended excising a significant section from the proposed Dupont Circle Historic District expansion area, noticeably changed the way the Dupont Circle preservationists addressed the issue of race. Even before the city’s landmarks committee had made its final determination about the historic district, Dupont Circle preservationists attempted to sway their view by arguing that the D.C. Preservation Office was ignoring African-American history. In a letter to the Landmarks Committee, the Dupont Circle applicants noted that inclusion of the area between 15th and 17th Streets, much of which had been excised from the designated district, would “assure landmark status for many black history sites.”[25]

The following year the new head of the Dupont Circle Preservation Committee, Charles Robertson, renewed the campaign. In a letter to the chairman of the Landmarks Committee he mentioned a long list of significant individuals who had lived in the area, including members of Frederick Douglas’s family, before turning his argument to what he saw as the principle at stake:

The northern boundaries should be expanded to include the 1700 blocks of T Street, Willard Court, and U Street all of which were developed contemporaneously with the rest of the neighborhood, which conform architecturally, and which constituted one of the major black residential areas of the city at the close of the nineteenth and at the beginning of the 20th centuries. We were particularly dismayed by the elimination of ‘Strivers Row’ (1700 block of U Street), perhaps the most significant symbol of the assertion of black Washingtonians in the late Victorian period.[26]

Given that the DCCA had not used the term black history in their original application or given any detailed account of the role of African Americans in the history of the area, this represented a clear shift in strategy and a redefinition of the nature of the history supposed to be protected by the historic district. But their change of tack about the historic significance of social history to the historic district proposal did not sway the Landmarks Committee. They agreed with the staff report that many parts of the expansion area simply could not be described as being in the Dupont Circle neighbourhood and that, therefore, they should not be in the Dupont Circle Historic District.

Expansion Redux

The Dupont Circle Preservation Committee—now operating as a separate preservation-oriented group called the Dupont Circle Conservancy—began work on a new historic district nomination in 1980 and filed the application in 1982. Once again they sought to expand the district substantially to the north and east. In fact the Dupont Circle Conservancy basically reprised the boundaries identified in the earlier proposal but extended the boundary an additional block further east. It was a proposal that affected hundreds of properties, and real estate and business interests quickly raised voices in protest (figure 5).[27]

Figure 5

Proposed Dupont Circle Historic District Expansion proposal, 1980–3. The shaded area on the left shows the scope of the Dupont Circle Historic District as expanded in 1978.

The Dupont Circle Conservancy was confronted, however, with a less anticipated source of opposition, one that had not been evident during the 1977–8 expansion campaign. It came from the 14th and U Street Coalition, which represented small business operators on U Street and in nearby areas and was headed by a would-be political entrepreneur, Edna Frazier-Cromwell. Frazier-Cromwell protested that her organization and its members had not been consulted about the expansion proposal and that the Dupont Circle effort was a straightforward attempt to create for itself a wider zone of political and economic influence. This, she asserted, was completely unjustified by history, as she considered the area around 14th and U streets, which was to be included in the historic district expansion, to be in the heart of the historically African-American district, known since the 1960s as Shaw. She also argued that the redevelopment or restoration of the area, widely assumed to be inevitable, should be controlled by the community and minimize the displacement of existing residents and businesses. In a letter to Charles Robertson, she remarked that “many people are concerned that an historic district designation may adversely impact property owners in our community who are on fixed incomes.”[28] In saying this, Frazier-Cromwell made clear that her organization believed that the historic district expansion was a thinly veiled attempt to encourage further private market restoration in the area. The expansion of interest in restoration would lead inexorably to higher real estate prices, she suggested, thereby inflating rates as well as rents, and initiating rapid social change.

In response the Dupont Circle Conservancy launched a concerted effort to persuade the U Street Coalition that the historic district was not a tool of gentrification, or an effort to “colonize” Shaw, but rather a means of enhancing community control of its historic assets and hopefully of fostering pride in them as a result. The conservancy pointed to organizations in the area that were co-sponsoring the historic district nomination, the Midway Civic Association and the T Street Block Council, that were both composed mostly of African American members. The Dupont Circle Conservancy was anxious to demonstrate its awareness of the issue of affordable housing, as well as the fact that proponents of an enlarged historic district represented a broad coalition of interests, not simply prosperous whites. In his response to Frazier-Cromwell, Charles Robertson argued that developers will go “where they think they will make a profit, regardless of historic district lines.”[29]

Sensing, however, that they were making little progress and that the whole expansion effort might come undone as the result of the conflict with the U Street Coalition, the conservancy stepped up its campaign, working to influence Washington Post reporters Carole Schifrin and Anne Chase to write sympathetic articles about the proposal and offering to present their case to community groups.[30] Chase did publish a piece about the conflict in the Washington Post in April 1983 and quoted Gladys Scott Roberts, an African American from the Midway Civic Association, who said that the Dupont Circle Conservancy “were doing a marvelous job. They discovered there was a great black history in this neighborhood.”[31] Such commentary was deliberately mobilized to dispel the impression that the historic district expansion would enable racial succession from black to white in areas covered by the district. But the publicity did not go all one way. In fact, Chase’s article led with critics of the expansion. Director of the Shaw Project Area Committee Ibrahim Mumin was unequivocal about what the historic district represented. “It’s a land grab by the middle and upper middle class Caucasians who live around Dupont Circle to extend their political influence.”[32] Even more tellingly, Edna Frazier-Cromwell remarked, “I can just see the real estate brochures. ‘Luxury condominiums in Dupont Circle East.’”[33] While it was relatively easy to deflect Mumin’s comments, which implied an organized, racially motivated takeover, Frazier-Cromwell’s suggestion that the historic district would be an agent of predominantly white gentrification was much harder to resist.

As Marion Barry’s electoral defeat of Sterling Tucker in the Washington mayoral election of 1978 had shown, all was not black and white in DC politics, even if race was everywhere and in everything. The racial politics that attended the historic district dispute were deeply embedded in the class dynamics that were very particular to that part of Washington. Many African Americans, such as Maurice Thomas and Gladys Scott Roberts, who both lived in the contested area and participated in the effort to expand the historic district, accepted that they were a part of a redefined Dupont Circle area. While not universally the case, many of these people associated themselves with the area’s long-established African-American elite, sometimes referred to as Washington’s “black aristocracy.” This group tended to support the pursuit of civil rights and de jure racial equality. They had historically distanced themselves from the idea that African Americans should build strong, separate racial institutions and businesses. In contrast, race leaders and black newspaper editors in the Shaw area had tended to support strategies more attuned to economic autonomy and political empowerment. The most recent iteration of the latter perspective had emerged among black power advocates in the late 1960s and underpinned efforts to strengthen community control of urban renewal in Shaw and elsewhere. This racial and class dynamic remained relevant in the 1970s and shaped the conflict between the Dupont Circle preservationists and their opponents in the 14th and U Street Coalition.[34] Even though the community-controlled redevelopment agenda had faltered in Washington in the 1970s, and in Shaw in particular, Edna Frazier-Cromwell and her supporters still saw the language associated with that phase of community mobilization as a legitimate and powerful tool. For example, a U Street Coalition flyer prominently asserted their determination to “promote community controlled redevelopment and, yes it’s going to be difficult, but ultimately we will be the ones to determine what happens in our neighborhood.”[35]

Skin tone also remained important at this intersection of race and class identities, something that was certainly not lost on white, Dupont Circle Conservancy preservationists. The surviving correspondence from this battle, which is very rich, provides a glimpse of the complicated ways in which racially based claims could become sources of resentment and mobilize unexpected racial discourses. For example, a personal letter from Katherine Eccles to Charles Robertson discussing ways of dealing with the ongoing opposition to the Dupont Circle Conservancy’s historic district proposal contained a particularly pointed reference to Frazier Cromwell, describing her as a “high yella bitch.”[36] The implication of this epithet was that Frazier-Cromwell was insincere in her opposition to the historic district proposal and politically opportunistic. Eccles insinuated that not only was Frazier-Cromwell using race as a rallying point for local political action (playing the race card), she was doing so “inauthentically,” as her real social and racial identity should have aligned her with wealthier “strivers” who had traditionally been more closely associated with the Dupont Circle whites and who, in the historic district dispute, lined up behind the district expansion. Eccles here appropriated a black vernacular for drawing social distinctions—that between ordinary black folks and those who were “hi yella”—to enable herself to occupy an authentic position and set aside Cromwell’s critique of historic preservation as self-serving. Eccles’s own racial politics, as far as can be inferred from her public representations and correspondence with her fellow neighbourhood preservationists, were explicitly liberal and integrationist, so it obviously galled her when Frazier-Cromwell opposed the historic district on the grounds that it was an assertion of white privilege. Eccles’s use of the racially loaded expression “hi yella” not only highlighted the personal animosities that the historic district expansion stirred up, it also underlined the complex coding of social space in that part of Washington and the obvious difficulties of establishing a multi-ethnic or multiracial consensus on issues connected to urban identity and space.[37]

Charles Roberston and Katherine Eccles, who led the Dupont Circle Conservancy campaign expansion, and both of whom lived in the historically black, disputed area, never publicly contested the legitimacy of the goal of “community control.” Instead they disagreed with the claims made by their opponents about the meaning and effects of the historic district expansion. But as their frustration grew more obvious, their chances of succeeding in the historic district expansion also slowly dissipated. By April they acknowledged the inevitable. The attorney for the coalition supporting the expansion, Richard Friedman, circulated a memorandum on 19 April 1983, which indicated a substantial shift in strategy. It noted that the historic district advocates now fully accepted the validity of the concerns of residents in the eastern and northern sections of the expansion area as represented by Advisory Neighborhood Commission 1B, ShawPAC, 14th and U St Coalition, and St. Augustine’s Parish. As a result, the Dupont Circle Conservancy now proposed to work with people of these communities to help them develop a separate historic district that would require substantial further research and that would likely have no direct association with Dupont Circle. Friedman recommended that “discussion should focus on developing an approach that avoids any inappropriate geographic or political incursion of ‘Dupont Circle’ into areas that have not been associated with Dupont Circle historically and are not currently identified with Dupont Circle.”[38]

This effectively put an end to the Dupont Circle Conservancy’s efforts to expand the Dupont Circle Historic District. However, with the designation of a separate Strivers Row Historic District (1983) in the northeast corner of the nominated area following a recommendation from the city’s preservation office, and the designation of the Greater 14th St. (1994), Greater U St. (1998), and Shaw (1999) historic districts over the next two decades, almost all of the area originally included in the successive Dupont Circle Historic District nominations was given historic district protection. Yet the circumstances by which this happened and the individuals who controlled the process were completely altered, a consequence of the events discussed in this article. The assumption of responsibility for defining what was historically important in the surrounding district by Dupont Circle preservationists in the late 1970s and early 1980s not only looked like a strategic error in retrospect, it appeared to be an over-assertion of cultural taste and authority that was no longer tenable. The criticism that they had overreached, attempted to annex a portion of the city that did not belong to them, was one that resonated. Later historic district nominations in places such as Mount Pleasant were very carefully circumscribed and built high levels of local support before making any such public claims. From the time of the Dupont Circle conflict onwards, the question of who was speaking for what history was in the fore.

Conclusion

The overt acknowledgment of social antagonisms centred on competing claims about what was historically significant in the urban environment, and especially who had the authority to say so, tells us a lot about Washington, DC, in the late 1970s and early 1980s. It reveals the fact that many inhabitants of the intown neighbourhoods were interested in taking control of decision-making that affected their immediate physical environment. It also demonstrates that the protection of the historic environment was a key part of this, not simply a pastime for ladies in tennis shoes, as Philip Johnson had quipped.[39] The story of what happened around Dupont Circle also reveals that the capacity and entitlement to say that a place is historically significant, and thereby protect it, is a form of social power. Digging down into the details of these debates in Washington of thirty years ago also revealed that, as a form of social power, participants expected that it would be negotiated according to long-established codes that mediated such power, not excluding skin tone.

Once the question of social power was articulated by the opponents of the historic district expansions, it was almost inevitable that the question, historically significant for whom? would be politicized, recognized that is connected to the exercise of power. Inadvertent or not, going beyond a boundary, beyond what people knew, or thought they knew, as the Dupont Circle neighbourhood, revealed the audacity of claiming and naming what was historically significant. Who are you that get to say so? Is it your race, historical expertise, or something else on which your authority to make that claim is founded? The important thing is not so much the answer in this instance, as the discovery that the question had been able to remain concealed for so long.

Parties annexes

Acknowledgements

The maps accompanying this article were made by Matthew Gilmore of the DC Planning Office. Matthew is the list editor of H-DC and a great supporter of historical research in Washington, DC.

Biographical note

Cameron Logan is an Australian Research Council (ARC) Fellow in the Faculty of Architecture, Building and Planning, at the University of Melbourne. His research interests include the social politics of neighbourhood preservation and restoration; the conceptual problems related to the conservation and demolition of modern buildings; and changing ideas of monumentality and historicity from the nineteenth century onwards. He has published articles on heritage conservation and historic preservation in the Journal of Architecture and the APT Bulletin, among other venues, and is currently working on two book projects: an urban history of Washington, DC, and an architectural history of the modern hospital.

Notes

-

[1]

Randall Mason, “Fixing Historic Preservation: A Constructive Critique of ‘Significance,’” Design Observer 16, no.1. (Spring 2004): 64–71.

-

[2]

On how to assess significance, see “The Secretary of the Interior’s Standards for Evaluation,” http://www.cr.nps.gov/local-law/arch_stnds_3.htm; and Norman Tyler, Ted Ligibel, and Ilene R. Tyler, Historic Preservation: An Introduction to Its History, Principles and Practice, 2nd ed. (New York: Norton, 2009), 135–40.

-

[3]

Dupont Circle Historic District nomination form, January 1976, Neighborhood Resources (Dupont Circle), Kiplinger Library, Historical Society of Washington, DC (HSW); Capitol Hill Historic District nomination form, July 1976, Neighborhood Resources (Capitol Hill), HSW.

-

[4]

Wolf Von Eckardt, “Don’t Tear It Down,” Washington Post, 30 November 1974. Also see Leila J. Smith, “A Preservation Action Group for All Washington,” Washington Preservation Conference Proceedings (Washington, DC: National Trust for Historic Preservation, 1972), 71.

-

[5]

As early as 1960, journalists commented on the extent of the restoration trend in Washington, DC. Robert J. Lewis, “Washington’s Restoration Areas: A Series, IV. Georgetown,” Evening Star, 31 December 1960. For analysis of demographic change in the city, see Howard Gillette, Between Justice and Beauty: Race, Planning and the Failure of Urban Policy in Washington, D.C. (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1995), 151–4. In 2009 Washington had twenty-eight neighbourhood historic districts covering around twenty-five thousand properties, a significantly greater total than San Francisco and much greater in percentage of the city than New York City, two of the other big cities with expansive historic preservation protections. For information about the scope of the city’s historic preservation controls, see “District of Columbia Inventory of Historic Sites,” September 2009, http://planning.dc.gov/DC/Planning/Historic+Preservation/Maps+and+Information/ Landmarks+and+Districts/Inventory+of+Historic+Sites/Alphabetical+Edition.

-

[6]

Sulieman Osman, The Invention of Brownstone Brooklyn: Gentrification and the Search for Authenticity in Postwar New York (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011); on gentrification in Washington, DC, see Brett Williams, Upscaling Downtown: Stalled Gentrification in Washington, DC (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1988); on Providence, see Providence City Plan Commission, College Hill: A Demonstration Study of Historic Area Renewal (Providence: Providence City Plan Commission, 1959); and Briann Greenfield, “Marketing the Past: Historic Preservation in Priovidence Rhode Island,” in Giving Preservation a History: Histories of Historic Preservation in the United States, ed. Max Page and Randall Mason, 163–84 (Routledge: New York, 2004); and on Charleston, Robert R. Weyeneth, “Ancestral Architecture: The Early Preservation Movement in Charleston,” in Page and Mason, Giving Preservation a History, 257–82.

-

[7]

Dennis E. Gale, “Restoration in Georgetown, Washington, D.C.” (PhD diss., George Washington University, 1982); Frank H. Wilson, “Gentrification in Central Area Neighborhoods: Population and Housing Change in Washington, D.C., 1970–1980” (PhD diss., University of Michigan, 1985), 112–43; Dennis Gale, “The Back to the City Movement Revisited: A Survey of Recent Homebuyers in the Capitol Hill Neighborhood of Washington, D.C.” (occasional paper, Department of Urban and Regional Planning, George Washington University, Washington, DC, 1977); Gale, Washington, D.C.: Inner City Revitalization and Minority Suburbanization (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1987), 10–27.

-

[8]

“City Acts on SE Protest: Stops House, on Inspections,” Capitol East Gazette, December 1967. For earlier recognition of the code enforcement problem, see Lisle C. Carter (Washington Urban League), letter to the editor, Washington Post, 20 December 1955.

-

[9]

Peter Thomas Rohrbach, “Poignant Dilemma of Spontaneous Restoration,” City (August–September 1970): 65–7.

-

[10]

Ibid., 65.

-

[11]

Capitol Hill Joint Committee, “Capitol Hill Prospectus,” 1967, 17.

-

[12]

Philip A. Ridgely, letter to City, 1970, repr. in Historic Preservation 22, no. 4 (October–December 1970): 10.

-

[13]

Penn Central Transportation Co. vs. New York City, U.S. Supreme Court, 438 U.S. 104 (1978). On the legal implications of the ruling, see Carol M. Rose, “Preservation and Community: New Directions in the Law of Historic Preservation,” Stanford Law Review 33, no. 3 (Febebruary 1981): 473–534. On the wider set of developments propelling the field at the time, see Mike Wallace, “Preserving the Past: A History of Historic Preservation in the United States,” in Mickey Mouse History and Other Essays on American Memory (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1996), 202–3.

-

[14]

Historic Landmark and Historic District Protection Act of 1978, DC Law 2-144. For a detailed account of the background and content of the law, see Jeremy Dutra, “You Can’t Tear It Down: The Origins of the DC Historic Preservation Act,” 2002, Georgetown Law Scholarly Commons. http://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/hpps_papers/.

-

[15]

Nelson F. Rimensnyder, The Political Evolution of the District of Columbia: Current Status and Proposed Alternatives (Washington, DC: Library of Congress Congressional Research Service, 1975); D. Harry S. Jaffe and Tom Sherwood, Dream City: Race, Power and the Decline of Washington, D.C. (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1994), 94–104; Gillette, Between Justice and Beauty, 60–3.

-

[16]

Jaffe, Dream City, 79; Gillette, Between Justice and Beauty, 192.

-

[17]

Gillette, Between Justice and Beauty, 192.

-

[18]

For a historical perspective on the riots, see ibid., 179–83; a more journalistic account from the time is Ben Gilbert, Ten Blocks from The White House: An Anatomy of the Washington Riots (New York: F.A. Praeger, 1968).

-

[19]

Francis D. Lethbridge, “Goals of the Landmark Committee,” Records of the Columbia Historical Society (1963–5): 448–451; Carl Feiss, A Program for Landmarks Conservation in the District of Columbia: Recommendations to the National Capital Planning Commission on the Preservation of Historic Landmarks, Buildings, Monuments, Places and Districts of Historic, Architectural and Landscape Merit in Washington, D.C. Washington, 1963.

-

[20]

Capitol Hill Historic District nomination form, July 1976. The source for the quote was Letitia Brown, “Residence Patterns of Negroes in the District of Columbia, 1800–1860,” Records of the Columbia Historical Society (1971), 66–79.

-

[21]

Ibid.

-

[22]

Ibid.; James Borchert’s research, conducted at roughly the same time as the historic district research, makes clear that the Capitol Hill neighbourhoods were characterized by a clear pattern of dwelling based on race in the late nineteenth century, with African Americans inhabiting interior blocks and alleyways and whites the main streets. See Borchert, “Alley Landscapes in Washington,” in Common Places: Readings in American Vernacular Architecture, ed. Dell Upton and John Vlach, 281–91 (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1986). For an example of how black history was given a place within the pageant of the American past in Washington during the lead up to the bicentennial, see Ron Powell and Bill Cunningham, Black Guide to Washington (Washington: Washingtonian Books, 1975), produced with assistance from Afro-American Bicentennial Corporation. For a historical analysis of the production of historical meaning through the bicentennial celebrations, see John Bodnar, Remaking America: Public Memory, Commemoration and Patriotism in the Twentieth Century (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1992), 226–44.

-

[23]

Dupont Circle Historic District nomination form, January 1976. On Alvarez, see Dupont Circle Citizens Association, “Annual Report of the Secretary,” 1 June 1973–1 June 1974, folder 74, container 2, DCCA Records, Kiplinger Library, HSW; Mara Cherksky, “For Sale to Colored: Racial Change on S Street, NW,” Washington History 13, no. 2 (Fall/Winter 1996–7): 40–57.

-

[24]

HPO Staff Report, Dupont Circle Historic District, March 1977, Neighborhood Resources (Dupont Circle), Kiplinger Library, HSW.

-

[25]

Lee Daub et al. to Henry Brylawski, chairman of JCL, 30 June 1977, folder 38, container 2, Dupont Circle Conservancy (DCC) Records, Kiplinger Research Library, HSW.

-

[26]

Charles Robertson to chairman of JCL, 12 March 1978, folder 38, container 2, DCC Records, Kiplinger Research Library, HSW.

-

[27]

On the formation of the Dupont Circle Conservancy, see Articles of Incorporation, folder 12, container 1, DCC Records, Kiplinger Library, HSW; and correspondence between Charles Robertson and Dennis Brown, folder 12, container 1, DCC Records, Kiplinger Research Library, HSW. On the reaction of large-scale real estate interests, see Washington Board of Realtors, “Proposal: A Reasonable Approach to the Effects of Historic Preservation,” March 1982, folder 12, container 2, DCC Records, Kiplinger Research Library, HSW. The most vociferous opponent of historic districts in the real estate business at the time was lawyer Whayne Quinn. For his view on the situation, see “Historic Preservation: The Need for Reform,” Realtor, November 1981.

-

[28]

Edna Frazier Cromwell to Dupont Circle Conservancy, October 1982, folder 40, container 2, DCC Records, MS 607, Kiplinger Research Library, HSW.

-

[29]

Charles Robertson to Edna Frazier-Cromwell, 18 January 1983, folder 41, container 2, DCC Records, MS 607, Kiplinger Research Library, HSW.

-

[30]

Richard Friedman to Carole Schifrin, n.d. (ca. February 1982), folder 42, container 2, DCC Records, Kiplinger Research Library, HSW.

-

[31]

Anne Chase, “Shaw Leaders Oppose Plans for Historic District,” Washington Post, 27 April 1983.

-

[32]

Ibid.; ShawPac, which joined the U Street Coalition in this battle, replaced MICCO as the official advocate for Shaw residents in the urban redevelopment process. “ShawPac Is Formed,” Washington Afro-American, 10 August 1974.

-

[33]

Ibid.

-

[34]

On the “black aristocracy,” see Michael Andrew Fitzpatrick, “‘A Great Agitation for Business’: Black Economic Development in Shaw,” Washington History (Fall–Winter 1990–1): 48–73; and Morris McGregor, The Emergence of a Black Catholic Community: St. Augustine’s in Washington (Washington: Catholic University of America Press, 1999), 360–3. A WTOP editorial, “Black Power,” broadcast on 22 August 1968, spelled out the stakes of what black power might mean for urban redevelopment. Transcript of “Black Power,” folder 59, box 57, Walter Fauntroy Papers, Special Collections, Melvin Gelman Library, George Washington University. For a broader overview of black power in local political discourse, see “Black Power and the Struggle for Home Rule, 1970–2000,” in Smithsonian Anacostia Museum and Center for African American History and Culture, The Black Washingtonians: The Anacostia Museum Illustrated Chronology, 295–300 (Hoboken: J. Wiley, 2005).

-

[35]

“14th and U Street Coalition” flyer, 1982, folder 42, container 2, DCC Records, Kiplinger Research Library, HSW.

-

[36]

Katherine Eccles to Charles Robertson, 7 December 1982, folder 40, container 2, DCC Records, Kiplinger Research Library, HSW.

-

[37]

Robertson and Eccles had become very frustrated with Frazier-Cromwell at this point and believed she was interested primarily in furthering her own political career via her opposition to the Dupont Cicle Historic District expansion. They started a file on her that contained documents depicting her in a negative light. Among the documents were a newspaper article, “Illegal Election-Moves Charged,” Washington Times, 23 February 1983; and a letter, Mrs. William Johnston to Edna Frazier Cromwell, folder 42, container 2, DCC Records, Kiplinger Research Library, HSW. The events were also covered in the black press, but no wrongdoing was reported: “School Board Fills Vacancy: Frazier-Cromwell Picked,” Washington Afro-American, 4 June 1983.

-

[38]

Richard Friedman to Dupont Circle Conservancy, 19 April 1983, folder 42, container 2, DCC Records, Kiplinger Research Library, HSW.

-

[39]

Carlton Knight III, “Philip Johnson Sounds Off,” Historic Preservation 38 (September–October 1986): 34. For discussion of Johnson’s contribution to the preservation debate between the 1960s and the 1980s, see Daniel Bluestone, Buildings, Landscape and Memory: Case Studies in Historic Preservation (New York: W. W. Norton, 2011), 14–15.

Parties annexes

Note biographique

Cameron Logan est un chercheur du Conseil National de Recherche australien, rattaché à la Faculté d’Architecture de l’Université de Melbourne. Il fait des recherches notamment sur les politiques locales de préservation et de restauration du patrimoine dans les quartiers urbains, les problèmes conceptuels se rattachant à la conservation et à la démolition de bâtiments modernes et la transformation du concept de monumentalité à partir du 19e siècle. Il a publié des articles dans Journal of Architecture et APT Bulletin. Il rédige en ce moment deux livres, dont un portant sur l’histoire urbaine de Washington D.C. et l’autre traitant de l’architecture des hôpitaux modernes.

Liste des figures

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

Redrawing of the Joint Committee on Landmarks’ 1964 map of “ districts of historic or monumental merit.” Comparisons to the present historic district map reveal substantial similarities, with the notable exception that the 1964 suggestions for historic areas completely ignored the area between 16th Street North West and Capitol Hill.

Figure 4

Figure 5