Résumés

Abstract

This article examines a critique of the “diasporic nationalism” affecting the Irish in Canada through the lens of Toronto, a key destination for Irish immigrants in the nineteenth century. Situated in the period of the third home rule bill and the articulation of opinion about it in Toronto (1910–1914), the article concentrates on the city’s media and particularly the visual content of cartoons published in the strongly pro-empire Evening Telegram. The author demonstrates how a familiar repertoire of Irish symbols and myths was grafted onto the bodies of Toronto’s “Irish” and/or “Ulster” personalities, connecting them with events on the other side of the Atlantic. These satirical representations also informed readings of Irishness in Toronto. They suggest that while a nationalist “green” identity had acquired a respectable and largely middle-class character among Catholics of Irish birth and ancestry in the early twentieth century, there were still forces at work that resisted placement of the latter group on a footing equal to the city’s Protestant majority.

Résumé

Cet article examine une critique du « nationalisme diasporique » affectant les Irlandais du Canada à travers le prisme de Toronto, destination importante pour les immigrants irlandais protestants au XIXe siècle. Situé à l’ère de la troisième home rule bill et de l’articulation de l’opinion à son égard à Toronto (1910–1914), l’article porte les médias torontois et notamment sur le contenu visuel de caricatures publiées dans le résolument pro-empire Evening Telegram. L’auteur démontre comment un répertoire familier de mythes irlandais a été greffé sur le corps de diverses personnalités « irlandaises » ou « ulstériennes » de Toronto, les reliant avec des événements de l’autre côté de l’Atlantique. Ces représentations satiriques ont également informé la lecture de la nationalité irlandaise à Toronto. Elles suggèrent que, tandis qu’une identité nationaliste « verte » avait acquise au début du XXe siècle un caractère respectable et en grande partie de classe moyenne chez les catholiques de naissance et d’ascendance irlandaise, il y avait encore des forces à l’oeuvre qui s’opposaient à ce que ces derniers soient mis sur un pied d’égalité avec la majorité protestante de Toronto.

Corps de l’article

I

The campaign to institute a measure of self-government or “home rule” in Ireland inspired a variety of reactions from the Irish in Canada and the United States in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries while prompting politicians and other activists in Ireland to engage with the diaspora of multiple generations on the other side of the Atlantic. Promoted through the 1870s as a constitutional remedy to the problem of “British misrule” in Ireland, the return of a Dublin parliament nullified by the Act of Union in 1800 also provided an alternative to the physical-force separatism espoused by the secret Irish Republican Brotherhood or “Fenian” organization, well known to Canadians through their border raids of 1866 and 1870 as well as through widely shared beliefs about their role in the assassination of Thomas D’Arcy McGee in 1868.[1] Through the subsequent four decades, therefore, the idea of an “Irish nation” re-emerging from the shadows of Westminster rule and taking control of its own affairs through constitutional means became predominant.

Research on the “diasporic nationalism” of North American Irish immigrants and their descendants in the post-1860 period has focused mainly upon the Catholic Irish in American cities whose fundraising and other agitating activities continued to provide shape to a “green Atlantic.”[2] The monetary donations of hopeful Irish (and occasionally non-Irish) men and women were channelled across the Atlantic in the 1880s and 1890s to fund the campaigns and salaries of sitting politicians of the nationalist home rule party (hereafter the “Irish Party”) at Westminster.[3] The first attempt at enactment in 1886 was stymied by a split in the ranks of William Gladstone’s Liberals, while the second bill foundered on the rocks of the House of Lords veto in 1893. The Irish Party thereafter endured several years of division before reunification in 1900 under John Redmond. By the end of 1910, two general elections resulted in the Irish Party gaining and retaining the balance of power while supporting Herbert Asquith’s Liberal administration. Moreover, the Lords veto was in the process of reform, and the Parliament Act of 1911 left Britain’s upper house with the power to delay bills for no more than two parliamentary sessions. The prospect of John Redmond leading the Irish Party to the holy grail of self-government now appeared to be only just a matter of time.

The quest for Irish home rule touched Canadians in different ways throughout the period. Its Canadian supporters persistently argued that since Canada had already acquired home rule and remained loyal to the Crown, so too should Ireland. The charismatic leader of the Irish Party in the 1880s, Charles Stewart Parnell, visited Montreal and Toronto in 1880, and the Canadian Commons passed resolutions in 1882, 1886, and 1887 in favour of Irish self-government. The one-time Liberal premier of Ontario, Edward Blake, moreover returned to the land of his parents to win an Irish Party seat at Westminster in 1892 and worked to maintain fundraising momentum in Canada thereafter.[4] Although the relationship between “home rule” and “Irish nationhood” was rarely clarified by the Irish Party, it was assumed by most Irish Canadians in the early twentieth century that the return of the Dublin parliament would not result in the departure of Ireland from the imperial realm. There were, however, those in Canada who had quite different views about Ireland’s political future.

This article thus uses the context of urban Canada to examine that body of opinion that remained hostile to the home rule measure, not because it offered too little but because it offered too much. By the late nineteenth century, supporters of the Act of Union between Britain and Ireland were geographically concentrated in the northern Irish province of Ulster and socially dominated by the island’s Protestants.[5] While unionism had its sympathizers in many parts of the island, the Irish Party ruled the electoral roost in the three remaining provinces of Leinster, Munster, and Connaught. In Ulster, the ultra-loyal Orange Order male fraternity had operated as a key organizational vehicle through which resistance to home rule was expressed from the late 1870s.[6] By 1910, Ireland’s unionists faced the latest challenge to legislate for home rule and reiterated the argument that the outnumbered Protestants in a Dublin parliament could do little but watch as the social policies of the Catholic Church would become enforced by the political majority. To this end, they coined the instantly memorable slogan, “Home Rule Is Rome Rule,” words that would become familiar not only in Ulster but also in parts of Britain as well as Canada.[7]

Although efforts to mobilize against Irish home rule took multiple forms in Canada, notably through the Orange lodges housing Protestants of Irish birth and ancestry, the article explores the ways in which the Irish unionist position was articulated and represented in the pages of Toronto’s daily Evening Telegram newspaper (hereafter the Telegram) and through the medium of political cartoons in particular. Although substantial numbers of Irish resided in North America’s largest cities by the early 1900s, there has thus far been no focused analysis of how evolving relations between nationalists and unionists in Ireland between 1910 and 1914 were covered in text and image in the newspapers of any particular city. When the growing interest among Irish historians on how Irish (or, more properly, Anglo-Irish) affairs were represented in popular cultural forms is considered, the nineteenth century appears well served in contrast.[8] Less-than-complimentary caricatures of Catholic Irish immigrants in Victorian newspapers and illustrated magazines such as Harper’s Weekly and Puck in the United States and Punch in England have been documented by a range of commentators. L. Perry Curtis Jr. famously described the evolution of the simianized “peasant Paddy” in all his ramshackle splendour, which included possessions such as his clay pipe, plug hat, shillelagh, and occasional stick of dynamite, while Michael de Nie concluded that in the eyes of the nineteenth-century British press, “the eternal Paddy was forever a Celt, a Catholic and a peasant.”[9] As de Nie shows elsewhere, the cartoons that appeared in British newspapers at the time of the first home rule bill conveyed a dismissive attitude towards Ireland’s pretensions to self-government while flagging the potential damage of home rule to the empire, with many of them using the image of the pig to represent “Ireland’s status as an agricultural, rustic and backward nation, as well as the Irish peasantry’s supposed indifference to filth and muck.”[10] Old reliables such as Britannia and John Bull guarded the dependant “Irish child” while “even those comic newspapers that were generally supportive of . . . Irish policy expressed their opinions in a format that essentially denied the capacity of the Irish to govern themselves.”[11]

In the twentieth century, writers such as John Appel and Kerry Soper have argued that inglorious characterizations of the male Irish immigrant had become watered down in the United States in its first few decades, with less explicit versions of “Paddy” positioning him somewhere between a lovable rogue and a subversive trickster.[12] In Canada, meanwhile, Bruce Retallack has recently shown not only how simianized Irish figures informed depictions of French-Canadian habitants, but also how such caricatures survived for both groups into the 1900s. Retallack does not consider the impact of political events in early-twentieth-century Ireland, however, and concludes that post-1900 depictions of Irishmen were used to provide commentary on the Canadian socio-political context where “the crucial sectarian fault-line that threatened the stability of the new Dominion’s fragile political order” was what mattered.[13] While the Toronto Telegram evidence shows that there is more to the story, it enriches rather than contradicts Retallack’s insights about sectarian fault lines in Canada. It also offers a Canadian comparison to Joseph Finnan’s recent tracking of how the Anglo-Irish political dramas of 1910–1914 were played out in the cartoons of Britain’s Punch. With more than a faint echo to the studies focused on the Victorian era, Finnan noted the “clear distinction [made] between [the] English and Irish” during this latest twist in the Irish saga that worked, again, “to the detriment of the latter.”[14] It was not just the literate classes of London and Manchester who continued to consume stock images of Paddy during these years; the happy Irish peasant and his plug hat was reaching the eyes of a Toronto readership as well.

While the aforementioned body of work shows that the taking of one side in the Irish nationalist / Irish unionist debate by cartoonists and editors invariably involved the circulation of (negative) opinion about the other, there were also place-specific effects. As the article will show, examining the way in which affairs in Ireland were communicated in the Telegram provides insight not only on the ways in which ideas about “Irishness” in general were being represented and narrated in one section of Toronto’s print media, but also on how these contributions related directly to the city’s population of Irish birth and ancestry. Questions relating to Irish identity had a vexed enough history in Toronto. By 1880, the balance of Irish Protestants to Catholics was about 60:40, and tense moments that pitted the likes of the “Hibernians” or “Young Irishmen” against the “Orange Young Britons” were witnessed on the city’s streets during the 1870s in particular, contributing to its reputation as the “Belfast of Canada.”[15] Toronto was also a key destination for Ulster Protestant immigrants from the 1840s onwards; recent research on Irish-born Protestants in the late nineteenth century suggests between 50 and 65 per cent had been born in the northern province, with the regional origins of the city’s Catholic Irish more scattered in contrast.[16] The growth of the Orange Order was another indication of the Ulster immigrant presence in Toronto, and, as with its Irish counterpart, the city’s lodges communicated their opposition to Irish home rule in the 1880s and 1890s, largely through the pages of their weekly organ, the Sentinel. If arguments about an “Orange diaspora” have any validity, then, Toronto clearly emerges as the leading North American centre; indeed, some of the evidence presented later in the article suggests the vociferous mobilization of an “Ulster diaspora” that was drawn mainly from within that fraternal network.[17]

By the early 1900s, Irish immigration to Toronto had fallen far behind that of the English and Scots, while social relations between Catholics and Protestants had undergone some transformation. Mark McGowan, in particular, has described the “waning of the green” in which those of Catholic Irish descent steadily lost interest in Irish nationalist affairs and became good “Catholic Canadians.’[18] While there is much to commend in McGowan’s meticulous examination of life in post-1900 Catholic Toronto, his account pays little attention to how the home rule issue was dealt with by Irish nationalists in the city or about how the matter affected perceptions of “the Irish” among the city’s Protestant majority. His emphasis on religious associations and media also misses social collectivities in which those who identified with “the green” chose to articulate their identities, as well as how their continued interest in Ireland informed representations by populist organs such as the Telegram in turn. While the cartoons discussed in this article do not refute McGowan’s argument outright, they will show how Toronto’s Irish Catholics, for all of their social mobility, could still be considered a group apart by some of those on the other side of the ethno-religious boundary and how the local media could be active in such boundary-making.

II

The Evening Telegram was founded in 1876 by John Ross Robertson (1841–1918), the Toronto-born son of Scottish immigrants and a fierce defender of “British traditions” in Canada.[19] Possessed of strong Tory sympathies (his father volunteered in the defence of Upper Canada during the 1837 rebellion), Robertson’s love of parades and regalia induced him to join Temperance Loyal Orange Lodge (hereafter LOL) No. 301 in 1861 and he became a regular presence at the Order’s 12 July parades.[20] Yet for all of his Orange and Tory leanings, Robertson’s mission as a newspaper man was to create a publication for the Toronto masses that was unfettered by partisan influence, thus enabling him to claim that it had both independence and integrity. “Big-business” lobbyists, monopolists, spendthrift aldermen, and opponents of the public ownership of utilities would all be vilified as the Telegram combined ““sensational practices, maverick politics, and much local news to win the support of the less sophisticated and less prosperous readers in Canada’s cities.”[21] Such “independence” did not amount to political neutrality, however, as Robertson also ran successfully as an Independent Conservative in East Toronto in the 1896 federal election.[22]

Robertson’s attempt to combine populism with political conservatism was overwritten by an unwavering commitment to the vision of an English-speaking and predominantly Protestant Canada sitting proudly within Britain’s empire, a vision that set the tone for the newspaper from the beginning. By the time the Irish home rule issue had re-emerged in 1910, Robertson’s views on the world were reliably served by his editor, John Robinson Robinson (1862–1928). Born in Guelph, Ontario, “Black Jack” Robinson arrived in Toronto at the age of nineteen, where he secured a job as a reporter with the Liberal Globe before finding his rightful niche with the Telegram as editor at twenty-seven years of age. As one historian (and former columnist) of the paper later put it, “The gospel according to one John was the gospel of the other,” while another of Robinson’s colleagues dubbed him a “splendid bigot.”[23] Certainly, Robinson shared many of the interests and sympathies of Robertson and on the occasion of the former’s death in late September 1928, terms such as “ardent Torontonian,” “enthusiastic Canadian,” “great Britisher,” “imperialist,” and “staunch Presbyterian” were thrown around by multiple informants alongside labels such as “earnest,” “uncompromising,” “loyal,” and “a fighter.”[24]

The third Telegram figure relevant here is George S. Shields (1872–1952), who faithfully communicated the gospel according to Robertson and Robinson through his cartoons. The Toronto-born Shields served as assistant to Owen Staples (a noted Canadian painter and illustrator in his own right) before establishing himself as the principal cartoonist for the paper circa 1908 and would spend sixty-two years in its employment overall.[25] As with the paper’s proprietor and editor, Shields too would become initiated into the mysteries of Orangeism, becoming a member of Sproule LOL No. 2253 (Robinson joined Cameron LOL No. 613), and he later held provincial office in the service of the Tories between 1926 and 1934 after serving as alderman in Toronto’s eighth ward.[26] Shields’s insignia was, appropriately, a double shield, and he was the creator of almost all the cartoons discussed here.

Given the common linkage between these three Telegram men and the Orange institution, members of the fraternity (and their households) formed a key segment of the paper’s readership and the editorial policy and cartoon content provided some indication of this, not least when the question of Irish home rule was being discussed. In general, the “Tely” periodically covered the activities of the city’s Orange and Masonic bodies as well as their regional meetings and other get-togethers. The history of the Toronto District LOL was featured among Robertson’s well-known “Toronto landmarks” series in the appropriate month of July 1910, and primary lodge meetings and foundations were reported on in local and suburban news columns.[27] Such inclusions did not, however, preclude the paper from criticizing individuals from the Order, such as those Conservative politicians who in its eyes had “consistently run away from the duty of standing up for the ideals of that order in the House of Commons at Ottawa.”[28] The newspaper remained a key champion of conservative ideas concerning Britishness and Canada’s “British inheritance” during the Edwardian era, ideas that had been in circulation in Toronto’s public sphere since the city’s beginnings.[29]

Robertson’s attempts to establish his paper as a force within loyal Protestant Toronto had succeeded. By 1909, the Telegram ranked as the third most-read daily in the city behind the Toronto Star and Globe, with an average daily circulation of 45,572, ahead of its competitors the Mail and Empire, Toronto World, and Toronto News.[30] For one historian, it was “very different” from the other five Toronto dailies, leading with several pages of classified advertisements before arriving at an always concise and often extreme editorial message expressed in simple language.[31] If the Globe and the Mail and Empire were the “quality” morning dailies, the Telegram joined other evening papers such as the Star and the News in competition for a local audience of middle- and lower-income readers.[32] Robertson had every reason to feel confident about his paper as a conservative “voice of the people,” and the city’s sobriquet of “Tory Toronto” appeared secure enough as the ubiquitous presence of Orangemen among its elected officials testified, not just on city council but increasingly at the provincial and federal levels.

In conceptualizing Shields’s role as the Telegram cartoonist, Douglas, Harte, and O’Hara have argued that “successful cartoonists did not stray far from the general ideas of their likely readers,” a point worth noting when considering Shields’s Orange sympathies and the spirited series of anti–home rule meetings organized by members of the fraternity in local halls, churches, public venues, and city streets between 1912 and 1914.[33] As Perry Curtis has put it, “Cartoonists . . . live and practice within ideology, drawing literally and figuratively on prejudices that already lurk or inhere in their audiences” while reproducing dimensions of these prejudices in a dialectical relationship.[34] With regard to the content of cartoons and their social impact, political geographer Klaus Dodds has noted how such seemingly simple caricatures in mass market–oriented newspapers and magazines could bring important clarity of global geopolitical relations to their readerships in the early twentieth century.[35] Images, like texts, could also make certain groups, cultures, and opinions more visible than others, while amplifying the “common sense” interpretations of political events held by individuals and groups.[36] Curtis in turn considers cartoons as “texts laden with clues to the social and political dynamics of any given time and culture,” while their success, for Michael de Nie, rests upon the readers’ knowledge of the issues, personalities, and symbols that together enable them to sense the degree to which the cartoons “contain some element of perceived truth.”[37] While the cartoonist’s audience might not always agree with the images and stereotypes portrayed, they would still “get the gist” of them.

Shields could also draw upon the precedents set by a tradition of political cartooning in Canada that stretched back more than half a century.[38] Its most famous exponent in Toronto was John Wilson Bengough, who established the weekly satirical magazine Grip in 1873, drawing some of his own inspiration from American periodicals such as Harper’s Weekly. One of Bengough’s cartoons of the 1870s featured an Irish-Canadian Catholic figure with a clay pipe, shamrock, and sash that bore a close resemblance to those produced by Thomas Nast of Harper’s, whose work Bengough admired.[39] By the early 1880s, Bengough was caricaturing Toronto Irish personalities such as Patrick Boyle, John O’Donohoe, Edward Blake, and Catholic Archbishop John Joseph Lynch.[40] Other works reflected his criticism of the power of the Catholic Church, which Nast would also have approved of.[41] More than just a cartoonist, Bengough was a lecturer, labour reformer, and sabbatarian, and his activities did not fail to attract attention to his illustrations, and by the time Grip met its demise in 1894, the Telegram was a year or so into its stride of producing daily front-page cartoons.[42]

While the paper’s original cartoonist, Staples (whose cartoons were signed “Rostap”), had little hesitation in adapting Bengough’s artistic conventions to his own depictions of Irishmen, he also drew from the less-restrained caricatures of Nast, American Puck cartoonist Frederick B. Opper, and Punch’s John Tenniel that featured not only “Paddy” but also his family. This is clearly seen in his 1905 cartoon “Neighbours” (figure 1) where, true to Mark McGowan’s thesis of increased residential intermixing in the city, a Toronto Irish Catholic and member of the Ancient Order of Hibernians fraternity (about which more later) borrows the hat of his Orange Protestant neighbour for use on St. Patrick’s Day. Although relations between the two are clearly cordial, the physiognomy of the Orangeman’s face clearly differs from the prognathism used by Staples to depict those of the Catholic and his family.[43] There is no question about who in Staples’s eyes occupied the higher place in humanity’s hierarchy.

Figure 1

Evening Telegram, 17 March 1905

Printed on pink paper, the Telegram’s front-page cartoon was now a prominent visual diversion that reflected the sympathies of the proprietor and his loyal editor. While readers may have quickly followed through to other sections, not least the many pages of classified advertisements that distinguished the paper, the cartoon emblazoned on the front was usually worth a glance, even if the viewer did not always have the patience to work through its message. If a meaningful connection was made between viewer and cartoon, however, the glance became more of a gaze.

While the Telegram’s cartoons betrayed the paper’s near-obsessive focus on municipal issues such as the public ownership of utilities, the future of the city’s harbourfront, and the use of the city budget, certain national and provincial issues also received pictorial comment. Debates about trade reciprocity with the United States as well as the question of whether Canada should develop her own navy or simply build dreadnoughts for Britain were the subject of several cartoons in 1911, for example, with Liberal Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier the subject of consistently unflattering representations. Elsewhere, time-honoured figures such as John Bull, Jack Canuck, and Uncle Sam appeared and, true to the ideas of who belonged “in public” at the time, there were few women. One Orange obsession of the period, the proliferation of bilingual schools in Ontario, was a provincial issue receiving coverage in some cartoons, but when it came to politics that extended beyond North America, the saga in Ireland was undoubtedly the topic of choice. While this may appear anomalous, it fitted with the affections of Robertson and Robinson for “the British connection” in Canada as well as the interest in British and Irish affairs held by the newspaper’s audience, not simply those of Irish-Orange background but also the large numbers of immigrants from England and Scotland who had entered the city since the late 1890s.[44] Shields rarely featured stereotypical images of Scottishness or Englishness in his cartoons, however, and those containing the former were more likely than the latter.[45] Although the immigration of “foreigners” from southern and eastern Europe was a topic left alone by Shields during the period studied here, there was no shortage of news stories about their increased presence within the paper itself.

The “Irish” cartoons identified for the period between January 1910 and July 1914 are of mainly two types: those dealing directly with home rule and those commenting on local affairs within Toronto’s (Catholic) Irish community. A total of thirty-four cartoons addressed Irish home rule, the vast majority of them doing so unambiguously. As Finnan discovered in the case of Punch, the frequency of publication for these cartoons in the Telegram correlated broadly with the moments of high political drama in Ireland or Westminster (and particularly where developments in Ulster were concerned) during the period.[46] In 1912, when the third home rule bill appeared in Westminster and unionists signed the Ulster Covenant that pledged to fight against its imposition, ten cartoons appeared. Likewise, fifteen were printed during the first half of 1914, before a possible civil war in Ireland was averted by the intervention of the First World War.

Fourteen additional cartoons provide a perspective on relations within Toronto’s Catholic Irish community. As we shall see, however, a hallmark of Shields’s work was his connection of Toronto-based Irish personalities and groups with the politics of the “homeland” across the Atlantic so that to neatly divide “Toronto Irish” from “home rule” cartoons is problematic. This difficulty reflects the strongly localist orientation of the newspaper and Shields’s sense of the potential for Anglo-Irish issues to be filtered through locally recognizable figures in a manner that would have been impossible for a larger-scale publication such as Punch. But it is clear that the Telegram’s sustained interest in home rule between 1910 and 1914 encouraged Shields to increase his level of interest in the Catholic Irish world in his city accordingly. This was a world whose “green” Irish nationalist sensibilities had become largely middle-class and constitutionalist while also loyal to Canada and the Empire.[47] The United Irish League (UIL), established in 1902, was part of a wider continental effort to reignite transatlantic fundraising, and the Torontonians welcomed Irish Party leader John Redmond in 1904 and one of his key associates, T. P. O’Connor, in 1906 and 1910. Elsewhere, the Ancient Order of Hibernians (AOH) had asserted their presence in the city since their foundation in the early 1890s and though their membership numbers were levelling off, having reached a peak of 1,778 in 1905, they nonetheless advanced discourses about Ireland’s past, present, and future, not least through the appearance of fiery Irish-American speakers for their annual St. Patrick’s Day concerts.[48] Finally, the city’s Gaelic League branch, founded in 1906, organized lectures, language classes, and entertainments as part of an ostensibly non-political agenda to restore Irish “ethnic pride” through cultural revivalism.[49]

Rightly sensing that Canadians were passively in favour of granting home rule to Ireland, these three organizations felt no need to parade their enthusiasm for the measure on the streets of Toronto. St. Patrick’s Day parades had in any case long since been discontinued, as a low-profile approach to integrating to Canadian society was favoured, guided especially by the local clergy.[50] The familiar argument that Canadians had benefited from their own version of home rule did not come exclusively from Irish activists either. Ontario Liberal Premier George W. Ross remarked at the UIL’s Redmond meeting of 1904, for example, “Home Rule does not mean separation, but such a federation as would allow Great Britain and Ireland to remain one”; at the T. P. O’Connor meeting two years later, he stated, “We are all home rulers.”[51] Whether these organizations supportive of Irish home rule behaved in a respectable or low-profile manner is in many ways beside the point. Turning his attention to events in Ireland between 1910 and 1914, Shields could mine these organizations alongside the local political scene for the “green” personalities he required to undercut arguments for home rule.

III

The sympathies of the Telegram for Irish unionism were not difficult to trace in its coverage of the British general election of January 1910, for which Robinson acted as London correspondent. Occurring amidst the constitutional crisis brought on by the House of Lords’ rejection of the Liberal government’s “people’s budget,” Robinson’s dispatch of 29 January tellingly reported that the “Irish Unionists insist on no surrender of the Lords’ right to refer the Home Rule Bill to the people. Failing that, they declare they will fight rather than be alienated from the authority of the British Commons and subject to the ascendancy of a Dublin Parliament.”[52] A few days later, the first of the cartoons drawn to reflect the changed circumstances was published. Not the work of Shields or Staples, it featured a crouching Irish nationalist carrying an “Irish vote” tool bag, which he offered to exchange for a home “rule” from Liberal Prime Minister Asquith who, alongside Conservative leader Arthur Balfour, was dressed as a tradesman. Although the Irish nationalist figure was shady rather than menacing, the language was predictably colloquial: “I’ll thrade yez the hull kit f’r a Home Rule.”[53]

While such mangled pronunciations were also a trademark of Shields’s Irish cartoons, the use of generic nationalist figures was not. And while Shields preferred to relate the saga of Irish home rule to his Toronto audience mostly through the use of local “Irish” figures, two other aspects of his work are highlighted in the rest of the discussion: his re-appropriation of symbolic practices long used to satirize Irish nationalists and Ireland itself (but without the prognathic features), and his attempts to legitimize the unionist position through his imaginative renderings of (Orange) Ulster and Ulstermen versus (Green) Ireland and Irishmen. For the latter group, four Catholic Toronto residents in particular appeared in Shields’s cartoons during the period. Though all were or had been involved in party politics, none had been born or raised in Ireland.

The most ubiquitous character was Gaelic League founder and president Leonard D’Arcy Hinds (1868–1948). Hinds was born in Barrie, Ontario; his Dublin-born mother came to Canada when still an infant, and his Irish paternal grandfather had settled in Simcoe County after emigration in 1842.[54] Hinds was educated at Toronto’s St. Michael’s College and became a judgment clerk at Osgoode Hall in 1905 while immersing himself in not only Irish associational circles but also those of the local Tories, bringing him into contact with more than a few Orangemen.[55] His penchant for poetry, songwriting, and all things Gaelic was acknowledged after his publication in 1901 of a song, “Oh, who would not be Irish?”—an unabashed declaration of ethnic pride that subsequently became popular.[56] Long-time secretary of the city’s UIL branch, Hinds also managed the Irish-Canadian Athletic Club, whose ranks included Canadian Olympian runner Tom Longboat. Hinds’s usual companions in the cartoons were Ontario attorney-general and fellow Conservative James Joseph Foy; registrar general and well-known Liberal, Peter Ryan, and the energetic member of the Toronto Board of Control J. J. Ward. Foy was a Toronto-born lawyer who attended the Irish Race Convention in Dublin in 1896 alongside Toronto Archbishop John Walsh, while Ryan (whose father hailed from Ulster) had emigrated from the north of England in the 1870s.[57] Ward was born in London, Ontario, and migrated to Toronto at the age of eighteen to pursue a career as a merchant tailor and make his mark in the local social and political scene as a labour activist.[58] All four men were part of the UIL committee struck to receive T. P. O’Connor on his return in September 1910, and they were joined occasionally in Shields’s cartoons by John O’Neill, a Toronto-born industrialist and alderman.[59]

Shields’s choice of who to represent Toronto’s principal “ethnic Irishmen” had been made prior to 1910, when their appearance on the front page of the paper was usually confined to St. Patrick’s Day. One such cartoon of 1908, entitled “A Limerick or a Shamrock,” depicted the faces of Ryan, Foy, and Ward emblazoned on the leaves of a giant shamrock pinned to Hinds’s coat as he recited the chorus from his “battle song of the Gaelic League.”[60] The following year’s cartoon showed Hinds, Ward, and Foy in a street parade, despite the fact that St. Patrick’s Day processions had long since ceased in the city.[61] This ironic imagination of “the green men” still out on parade on the seventeenth was also conveyed through text and sometimes compounded by Orange references such as the entry in the “Ups and Downs” humour column in 1911 that described the “Gaelic League, LOL, D’Arcy Hinds, W.M.” as “the finest looking assemblage of peasantry [that] took longer to pass a given point than any other body of troops in the parade that did not take place yesterday.”[62]

Unlike Ward, Foy, and O’Neill, Hinds never appeared in Shields’s cartoons in anything other than an “Irish” context during these years. Hinds’s conception of his Irishness combined the apolitical cultural revivalism of the Gaelic League in Ireland with the “imperial home rule” nationalism that John Redmond embraced after the reunification of the Irish Party in 1900.[63] Reacting to a summary of the third home rule bill circulated in early 1912, Hinds remarked that the Irish in Ireland “should be satisfied now . . . [The measure] is just the same practically as we have in Ontario.”[64] He strongly repudiated physical-force nationalism, claiming in a letter to the Telegram in July 1914 that he was “the son of an Irishman who took a stand in opposition to the Fenians.”[65] Ward, in contrast, featured in many cartoons by virtue of his role as a city controller. His efforts to develop a seawall in the city’s harbour, for example, found expression in his self-description as the “De Lesseps of Parkdale” in April 1910.[66] But his “Irish” background could creep into some of these cartoons devoted to local politics. In a 1908 work entitled “local geography,” Ward responded to the definition of an island as “a small body of land entirely surrounded by water” by proclaiming, “Yes, be jabbers, an’ a lake’s a body of water complately surrounded be a sae wa-all.”[67] To what degree could this have been a reasonable rendering of the accent and speech habits of the Ontario-born controller?

The humour column’s reference to an “assemblage of peasantry,” however ironic, mirrored Shields’s taste for undermining the respectable image cultivated by Toronto Irish nationalists. It is in any case one of the chief tasks of the cartoonist to undermine, often through seemingly “innocent wit,” and Shields was most successful in this respect with his series of cartoons in which the “green gang” re-embraced their peasant roots through resettlement in a post–home rule Ireland.[68] “The First Fruits of Home Rule” (figure 2), published in November 1911, suggested that the new political dispensation in Ireland would draw even the most successful (Catholic) “Irish ethnics” from Canada, no matter how well governed, back to the “best country in the world.” Here, Foy, Hinds, O’Neill, Ryan, and Ward climb aboard the decidedly un-genteel steerage compartment of a ship bound for Ireland. All five are noticeably travelling light, and Foy’s summary statement, as well as his comrades’ reaction, is predictably brogue-heavy. “The Irish Village,” published on 1 March 1912 (figure 3), continued the adventures of the five Canadian Irishmen in “the new Ireland.” Here, the dubious fruits of Irish self-government are presented through their retreat to a rural communalism where Shields unsubtly revives the Victorian caricature tool kit of thatched cottages, pigs, harps, shamrocks, and shillelaghs with the Torontonians recast as contented stage-Irish peasants who have, through O’Neill’s comment, turned their backs on Canadian urban modernity with some relief. Now, Peter Ryan plays the harp to an admiring pig while J. J. Foy brandishes a “Come back to Erin” pamphlet or songbook, and in the background Ward and Hinds merrily indulge themselves in Irish dancing, supposedly transmitting the lessons learned from classes in Toronto’s Gaelic League. The Ireland of a home-ruling future was thus unlikely to rise above its long-perceived profile as a backward and non-industrial place where time stood still. It was in any event likely to be read as such by Telegram readers suspicious of what home rule really entailed, not least those who were members of Orange lodges. Both cartoons also raise questions about the relationship between the ethnic loyalties of the “Toronto five” and their identification as Canadians. Foy and his companions may have “made it” in terms of socio-economic accomplishments in the land of their birth, but their credentials as loyal Canadians were not being accepted unequivocally. Although the lampooning of Irish nationalists was hardly out of the ordinary, Shields may have found the continued fascination of these Canadians with Ireland, Hinds especially, to be an irritating aberration. Scottish and English immigrants to Toronto had, after all, quickly become comfortable with their lot as British subjects in Canada and were not publicly recalling and narrating their ethnic origins to an excessive degree. And for all the bluster of Hinds and his pals, they were highly unlikely to relocate to a home-ruling Ireland. Indeed, few of the Irish abroad were likely to return, scant as the economic opportunities were likely to be.

Figure 2

Evening Telegram, 3 November 1911

Figure 3

Evening Telegram, 1 March 1912

Shields’s representations were supplemented by editorials highly critical of Ireland’s home rulers in the aftermath of the passage of the Parliament Act in August 1911 whereby the Lords’ veto, supposedly one of the “British traditions” so beloved by Robertson and Robinson, was removed. By the end of that month, the Irish Party at Westminster were described as “patriots who would smash up all the rules of parliamentary procedure into fragments and beat the Government with pieces of the furniture . . . Rowdyism in Parliament has done more for Ireland than respectability in Parliament has ever done for Scotland.”[69] Though a long way from the tactics of Fenianism, or even the parliamentary obstructionists of the late 1870s, the spectre of dangerous and out-of-control Irishmen had re-emerged through comparison with the more restrained, rational, and respectful Scots.

Not only could middle-class Toronto Catholics of Irish background be imaginatively transplanted to the landscape of the homeland to expose the limits of home rule, but that same landscape could be evoked to provide a commentary on the latest intrigue emanating from “Irish Toronto,” and D’Arcy Hinds was unfailingly at the centre of things. His departure from the Irish-Canadian Athletic Club was followed by his founding of an Irish Club in 1910 that would provide another athletic outlet while assisting incoming immigrants.[70] His efforts received a setback the following year with the province’s refusal to grant a licence to sell alcohol in the premises on the grounds that it would merely become a “jolly club.”[71] Shields’s response in “The Great Eviction Scene” (figure 4) was to depict a despondent Hinds addressing Ryan outside an abandoned thatched cottage, the latter seated on a bucket surrounded by debris forcibly removed from the dwelling as he receives Hinds’s commendations for morally supporting a club that “is sufferin’, like so many of its payple suffered in the Ould Land.”[72] Here, Shields drew upon an established pictorial history of Irish evictions in which the occupants observed the removal of their possessions or the destruction of their dwelling by bailiffs and crews with crowbars and battering rams. If the tranquil peasant landscape of Ireland presented a useful device for critiquing home rule, more turbulent aspects of its history could also be used to chronicle events specific to Toronto in which the Irish, as their nationalist narrative continuously reminded them, had to once again face oppression and suffering.

Figure 4

Evening Telegram, 8 June 1911

Given his preference for local notables, Shields resisted including allegorical figures familiar to Irish and British readers such as Britannia or Erin in his Irish-related cartoons. The Gaelic Leaguer Hinds was a candidate especially ripe for “Paddification,” and cliché-heavy parodies of his poetic compositions also appeared regularly in the newspaper’s “Ups and Downs” column. On the occasion of T. P. O’Connor’s visit in 1910, the column adapted the chorus of T. D. Sullivan’s “God Save Ireland,” citing the source as “’Heaven Help Ireland and Other Poems” by the Sweet Singer of the Gaelic League: “We’re for Tay Pay, said they proudly / We’re for Tay Pay, say we all / Whether on the committee or on the wall, what care we? / What matter, if we’re here for Ireland’s call?”[73] Such humour did not always go unanswered, with the League’s John Daniel Logan, no mean poet himself, defending the organization’s singing of “God Save Ireland” as a strictly “social and spiritual” exercise bereft of political context; his follow-up comment that the League’s project of cultural recovery was necessary since Ireland had become “through injustice and political tyranny, the home of lost causes’” was hardly free of political content, however, and was the sort of language that Shields would mercilessly ridicule through references to a suffering “payple” in “The Great Eviction Scene.”[74] A few months later, this narrative device would again be ridiculed in “A Sham Home Ruler,” when Foy declared his intention to go to Ireland to help “Tay Pay O’Connor lift the Saxon’s heel off the neck of sufferin’ Erin.”[75] The turbulence of Ireland’s past became a key source of humour to suggest that though the days of “Ireland’s sufferin’” were indeed part of the past, they were not part of the present reality, especially given the passage of legislation to undo the estate system of land ownership on the island. For Shields, these narrations of “the cause of Ireland” distorted the reality of ongoing policies of “constructive unionism” on the island, and were especially unbecoming from the mouths of avowedly loyal Canadians, not least Ontario Attorney-General Foy.

But if Hinds’s attempts at poetry provided easy ammunition for the Telegram’s humorists, they could also unwittingly test the temperature of Irish nationalist feeling in Toronto. Not all of the city’s nationalist-minded Irish shared Hinds’s sentimental representations of ethnicity, and some may have also found his earnest loyalty to Britain’s empire wearisome if not contradictory, given the deep ambivalence shared among many about the place of the Crown in Ireland. The AOH was one organization whose divisions housed some of the more hardened opinions, and the expression of misgivings about Hinds’s two-stanza ode to Patricia, the popular daughter of the Duke of Connaught, incoming governor general of Canada, led to his resignation from Division 5 of the fraternity in December 1911. With a first line that began, “Oh, Paddy dear, and did you hear,” not all cared to continue to the end where Princess Patricia was declared “the fairest Princess on earth.”[76] The affair inspired four Shields cartoons published between late April 1912 and early September 1913. While that of 25 April 1912, depicting Hinds on the receiving end of the “AOH boot,” left little to the imagination, the most humorous cartoon placed the Barrie bard on a pedestal to mark the grounds in Osgoode Hall where he first composed the ode (“Don’t she look swate / In her New Spring Hat / Old Ireland’s darling / the Princess Pat”).[77]

Hinds’s taste for controversy did not end there. He also publicly fell out with Catholic Register editor Fr. Alfred Burke, whom he eventually sued for libel, giving rise to a further series of Shields satires between late 1910 and early 1912. A number of days after the reporting of his suit in January 1912, Hinds stood dressed as a matador, sword in hand and with a shamrock-decorated bandana around his head while facing the “papal bull” as Foy, Ward, and Ryan looked on.[78] A more curious offering was that published the day before the “Glorious Twelfth” of 1912 where Hinds and Ryan unveiled a portrait of Fr. Burke, dubbed the “Worshipful Master of Catholic Register LOL No. 23”; Hinds explained the portrait as “the ile paintin’ of the benefactor who has done more to boom the Orange Order in these parts than anybody else in all history except King William.”[79] This ironic positioning of Catholic Irish Torontonians as Orangemen had been deployed by Shields the previous year with a cartoon of Foy, Ryan, and Hinds handling a fife, drum, and horse respectively, and the cartoonist would repeat it in 1913 with the additions of Ward and O’Neill.[80]

Although not a large organization, the Gaelic League’s existence and activities, not least those of its gregarious president, provided the Telegram with licence to exaggerate its importance and perhaps also that of “green nationalism” within the city’s social fabric. D’Arcy Hinds’s capacity to circulate ideas about Irishness could in turn be seized upon by the likes of Shields, demonstrating how the construction of “Irish” ethnicity in the city was more than simply a one-way process. McGowan’s account of the “waning of the green,” however, pays no attention at all to Hinds or the Gaelic League.[81] What is clear, however, is that Shields’s pen gave Toronto’s home rulers an added visibility, even through cartoons that focused more on local controversies and feuds. The likes of the “Toronto five” acted for a time as suitable stand-ins for those at the parliamentary coal-face of Westminster, with Irish Party leader John Redmond appearing in only two Shields cartoons prior to 1914.[82]

IV

Activists in the nationalist “green Atlantic” presented the island of Ireland as a geographically coherent homeland, evoking it in romantic terms in song, verse, and myth in ways that made obvious its claims to nationhood. And while the Telegram’s representations of the island’s landscape reinforced impressions of it as backward and pre-modern, they were supplemented by others that aimed to underline arguments that Protestant and unionist Ulster was a different place entirely, and more than simply one of Ireland’s four historic provinces. As Klaus Dodds puts it in describing the outline of a “popular culture” approach to the study of geopolitics, “Popular representations of events and places are as important as the formal politics of international relations.”[83]

Alvin Jackson has argued that militant attitudes had been on the rise in Ulster some time before the passage of the Parliament Act.[84] While the Ulster Unionist Council (UUC) was formed in 1905, Toronto audiences had long been exposed to arguments that directly linked Ulster’s industrial character with its loyal, thrifty, and sober Protestant population, and the Telegram became a likely forum for such views to publicly re-emerge between 1910 and 1914.[85] One letter sent from Ulster published in January 1911, for example, reprised them in the context of emigration to the United States. Vilification of Catholic Irish immigrants for their part in the creation of Tammany-style urban political machines perpetually in thrall to liquor interests was followed by praise for Ulster’s Protestants for helping to build up “the soundest elements of [American] social and national life. The free-bred minority of Ireland have [also] done splendid service in every department of British life—political, colonial, religious, educational and commercial, and they have made Ulster the most prosperous and enlightened portion of Ireland.”[86] While there had long been an assured body of opinion that Ontario too had benefited from the immigration of Ulster Protestants, this was now suggested as a remedy to the crisis likely to erupt in Ireland should home rule become law. In August 1911, an editorial recommended that “the Ulster foes of home rule flee to Ontario”:

Ulster can either rise up in arms and resist Home Rule, bow its neck to the yoke of a Dublin Parliament or teach her people to emigrate. Quebec is often quoted as an argument in favour of Home Rule. Quebec is the most conclusive of all arguments against Home Rule. Clericalism will be as dominant over three-quarters of Ireland as clericalism now is over the whole of Quebec. Clericalism will be as irresistible in rural Ireland, Ulster included, as clericalism has proved itself to be in rural Quebec . . . A home and employment in Ontario offer more attractions to the opponents of Home Rule than a grave on any field of civil war in Ireland.[87]

The suggestion was repeated one year later, with hope expressed that “scores of thousands of the Ulster unionists [will] find the homes which they seek here in Ontario.”[88] Ontario, British in character and modern in outlook, would thus become further strengthened against the “Romish aggression” emanating from Quebec, a phenomenon then manifesting itself through the question of French language instruction in schools in both eastern and southwestern Ontario.[89] Such aggression, it was conceded, was more likely to triumph easily in Ireland. Such sentiments formed part of a wider Telegram agenda to monitor “encroachments from Rome” on Canadian civil society in a manner similar to the Orange Sentinel and publications such as Robert Sellar’s The Tragedy of Quebec.[90] A 1911 editorial, for example, suggested that the Orangemen’s 12 July procession commemorating the Battle of the Boyne be interpreted “not as victory that exalted one creed over another but as a triumph for the truth of popular sovereignty over the error of divine right.”[91] Despite such characteristic editorial broadsides, George Shields included very few caricatures of clergymen in his cartoons, Catholic or otherwise, during the period studied here.

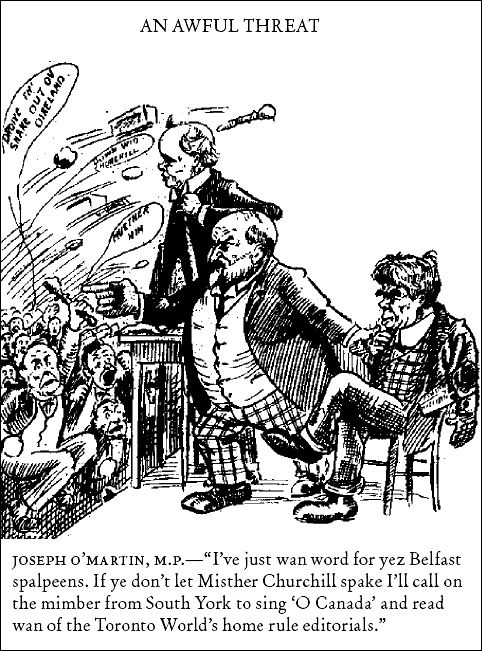

Shields’s interpretations of Ulster unionist resistance came to the fore on the occasion of the Belfast visit of the first lord of the Admiralty and youngest member of the Asquith Cabinet, Winston Churchill, in early February 1912. Nobody expected Churchill to get an easy ride in the north—predictions that came true enough—and Shields was sufficiently fascinated by the affair to publish four cartoons over a four-week period either side of the event. That of 27 January again parachuted known Canadian figures into the Irish scene. Now, the much-travelled Manitoba politician Joe Martin (“Joseph O’Martin”), then holding a Liberal seat at Westminster, joined with Toronto World owner and member of the Canadian Commons, W. F. Maclean, in attempting to quell a Belfast crowd hostile to Churchill (figure 5).[92] The cries of the unionist crowd are, perhaps surprisingly, expressed in brogue as if to suggest that deep down “the wild Irish” really were all the same, regardless of politics, while the threat of reading a pro–home rule editorial from the World allowed the Telegram to take another characteristic swipe at “Billy” Maclean, one of its main competitors in Toronto’s “penny press.” On 6 February, a less surprising image was that of Foy, Hinds, Ryan, and Ward, now fashioned as the “Irish Guards” protecting Churchill from unionist opponents on the Belfast streets (figure 6), with Hinds noticeably diminutive next to Churchill. One week later, Churchill and John Bull observed personifications of Australia, Canada, South Africa, and the United States in a bathtub clamouring for a “Home Rule for Ireland” bar of soap. Churchill’s claim that the boys in the tub will not be happy until the soap is picked up was responded to by Bull who asks, “But will I be happy if they do get it?”[93] Such reminders of the brewing political impasse in Ireland dovetailed with the first major public demonstration of support for Irish unionists in Toronto’s Massey Hall on 28 February 1912, an assembly dominated largely by Orangemen.[94]

Figure 5

Evening Telegram, 27 January 1912

Figure 6

Evening Telegram, 6 February 1912

With the third home rule bill introduced in Westminster in April 1912, ideas for the exclusion of Ulster were presented subsequently, notably by unionist leader Edward Carson in January 1913. A more defiant gesture came with the formation of the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) at the end of that month, and by September, a contingency plan had been made by the UUC for a provisional government to take over the province should home rule proceed without any exclusion measure. Shields responded to this increasingly militant atmosphere with his usual juxtaposition of Toronto and Irish personalities. Although Carson had been the leader of Irish unionism since February 1911, he did not appear in Shields’s cartoons until October 1913 when “With the Carsonian Conquerors” (figure 7) depicted him alongside Toronto’s Fred Dane, the Belfast-born Orange grand master of Ontario West. Unlike John Redmond, Carson had not visited Toronto, although statuettes of him were on sale in the city and new Orange lodges were being named in his honour.[95] The tea merchant Dane was prominent in this latest phase of Orange opposition and was the driving force behind the Canadian Unionist League, established as a fund-raising body in October 1913.[96] The cartoon projects a future military engagement, likely in Ulster, in which not only “Colonel Dane” is involved but also Toronto’s home rulers, led by D’Arcy Hinds, now taking their passions for Ireland’s cause to their logical conclusion. Confident and sturdy, Carson and Dane celebrate unionist victory while the defeated and injured Hinds recovers in the background.[97] A language of defiance was certainly present among Toronto supporters of unionism, and Telegram editor Robinson appeared at a Victoria Hall meeting in December 1913, where he insisted that “Ulster must never be allowed to become separated from the Union, to be an almost unrepresented and feeble power in a Nationalist Parliament at Dublin, dominated by the Ancient Order of Hibernians and its puppet, John Redmond.”[98] More menacing, perhaps, were the photographs of UVF drills published regularly in the paper between late 1913 and mid-1914 that emphasized progress made in preparing for future conflict.

Figure 7

Evening Telegram, 24 October 1913

Shields continued to represent Ulster resistance in various ways up until the onset of war in Europe, deploying political figures such as Carson, Asquith, Redmond, and Churchill with increased frequency. By late March 1914, “The Ulster Obstacle” featured a home rule train carrying Asquith and Churchill crashing into the rock of “Ulster resistance,” while in mid-April, “Halting the Measure” depicted Carson thwarting Asquith’s efforts to establish home rule over all of Ireland by delimiting where the northern border of the “Home Rule territory” should be drawn (figure 8).[99] Local figures continued to feature in some works, however, with ongoing developments such as unionist victories and losses in British and Irish by-elections interpreted mostly through the figure of Dane. In February 1913, Shields reacted to the Irish Party’s victory in the Ulster city of Derry by drawing a forlorn Dane with his Orange drum punctured by a “by-election brick”; an English unionist victory in November, however, led Dane to approve an “improved” Orange banner that read “Reading, Aughrim and the Boyne.”[100]

Figure 8

Evening Telegram, 18 April 1914

November 1913 was also the month when the nationalist Irish Volunteers were founded as a response to the UVF, inspiring further militaristic depictions, though not of the sort that would flatter the “green” nationalist side. In January, for example, “A Moving Picture by Cable” featured J. J. Foy excitedly presenting Peter Ryan with a picture of Hinds and the “Toronto Gaelic League Army” fighting “Carson’s Army”; what Foy does not seem to notice is that Hinds’s men are clearly in retreat.[101] In “The Irish Patrol” (figure 9), published in mid-March 1914, “Ireland” and “Ulster” are now identified as separate geopolitical entities. Here, Dane entrusts one-time Orange County master of Toronto and fellow Ulster-born immigrant William Crawford with the duty of guarding the Ulster frontier while Dane serves as the iconic Orange figure of King William III (William of Orange) sitting on his white charger. With “Ulstermen” as their primary identity, Crawford and Dane at once embody the Orange “no surrender” mantra and countless spoken and textual descriptions of the province’s unionists as “stout and defiant resisters.” They also suggest the possibility, still plausible, that some Toronto Protestants could take part in an “Ulster diasporic” response, should relations in Ireland continue to deteriorate, and words to that effect were controversially communicated to Carson by Canadian MP Captain Tom Wallace in late March.[102] The diasporic response of Toronto Irish nationalists, through Hinds’s “Gaelic League Army” was in contrast ridiculed as weak and amateurish, and the late March 1914 publication of A. Macintyre’s “Ireland For Ever,” inspired by Lady Elizabeth Butler’s painting “Scotland For Ever,” reprised the pig as the primary military vehicle for not only Ireland’s home rulers but also Asquith, Churchill, and David Lloyd George (see cover). The increasingly hopeless situation in Ireland, however, gave rise to more ambivalent feelings and the cartoon “A Snake in the Irish Eden,”[103] depicting the “serpent of lawlessness” slithering around Ulster, could be read as a critique of Carsonite brinkmanship as much as the determination of the province’s unionists to take their resistance to its ultimate conclusion. No such ambivalence was present, however, among the thousands who marched to Toronto’s Queen’s Park on 8 May 1914 in what was the most vivid demonstration yet of unionist sympathy in the city.[104]

Figure 9

Evening Telegram, 14 March 1914

Such outpourings of unionist support, whether in text, image, or speech, did little to convince Toronto’s home rule supporters. They had heard Redmond, O’Connor, and others relate how “the day is near” for more than a decade, and now they finally began to sense it. Hinds responded to the anti–home rule meeting of February 1912 by dubbing its supporters the “disloyal” ones.[105] Taking his cue from Redmond’s own lethargy in acknowledging the seriousness of the unionist position, Hinds described the latter in March 1914 as occupying “a false position. They are in the majority because their iniquitous laws drove out the men who opposed them,” adding that Ulster was unlikely to fight since the exclusion referenda “ought to . . . allay all their fears.”[106] Some days later, Redmond’s brother William spoke at Toronto’s Canadian Club, expressing delight that, despite the House of Lords’ recent rejection of the bill, the measure would be passed into law, with or without their consent. Unionist resistance was again treated as a temporary obstacle, with Redmond arguing that “the majority of the people of Ulster were undoubtedly in favour of Home Rule” with “tens of thousands of Protestant Irish” among its “staunchest supporters.”[107]

The increasing zeal with which the Telegram took the side of Irish unionism also contrasted with the reaction of other Toronto dailies, as the depiction of World owner Maclean in figure 4 suggests. Although highbrow papers such as the Globe and the Mail and Empire were oriented towards Liberal and Conservative audiences respectively, both targeted metropolitan readerships and had little need to resort to sensationalist headlines. They were unlikely to lampoon Toronto’s Catholic Irish personalities or draw explicit attention to “Orange” and “Green” identities, and the Globe was especially vigorous in its support for home rule in Ireland. The latter paper had also employed the Ulster-born ex-Orangeman Lindsay Crawford as its Irish correspondent, and his dispatches in early 1914 focused on divisions within Irish unionism (which were real enough, given Carson’s shifting emphasis towards Ulster) and what were, for him, exaggerated perceptions of the UVF as an effective military unit.[108] As the prospect of civil war loomed, the World issued a broadside claiming that “the whole trouble in Ireland arises from the action of brawlers like [Telegram editor Robinson] . . . while [he] may not be a typical Ulsterman he undoubtedly gives expression to the kind of things he thinks typical Ulstermen would say.”[109] The paper later featured a cartoon of Robinson using a “Protestant drum stick” to flog issues of the World, Globe, Star, and Catholic Register hanging on a clothesline.[110] The drum was a familiar Orange symbol and had been used by Shields in 1912 when he depicted John Redmond’s “Home Rule” drum being carried by the proprietors of the Globe, World and Star.[111] Always eager to face his local rivals, Robinson had long dismissed the Globe’s support for home rule as an exercise in “fishing for the Catholic vote,” but then the Telegram editor no doubt impressed his paper’s Orange readership by visiting Belfast alongside Fred Dane for the “Glorious Twelfth” celebrations in July 1914.[112]

One month later, the question of a possible eruption of war in Ulster was left to one side as Britain declared war on Germany and the thoughts of young Toronto men turned towards enlistment in an atmosphere suddenly charged with intense patriotic fervour. For the likes of D’Arcy Hinds, it was now a case of saving the empire and Canada’s place within it, and he was unsurprisingly a driving force in the formation of the 208th Irish battalion.[113] George Shields’s thoughts likewise switched to the evolving crisis in Europe, and, for the three months following the outbreak of war, Telegram readers became familiar with representations of the German enemy in the form of Kaiser Wilhelm, “the scourge of God,” “Captain Fritz,” and “the Devil of Louvain” alongside Prussian eagles, rats, and geese. Domestic heroes were represented by Shields’s pen in the form of Jack Canuck and courageous volunteer soldiers, while harsh judgments were meted out to unscrupulous plunderers, self-satisfied magnates, and Henri Bourassa for his criticism about Canada’s place in the conflict. The tribulations of Ireland, for a time, felt a long way off, but they would return.

V

While Joseph Finnan has argued that the home rule–related cartoons published in Britain’s Punch around the period covered here did not make the magazine “a proponent of Carson’s brand of unionism,” the same cannot be said of the Telegram, which remained consistently critical of home rule throughout.[114] Indeed, the Telegram, ever watchful of its local constituency, was by 1914 espousing not so much the cause of Irish unionism as that of Ulster unionism. While home rule elicited commentary in the Toronto dailies in general, especially during the first half of 1914, scholars have yet to establish how the issue was played out in text and image in the dailies of other “Irish cities” in North America. Finnan’s charge, however, that the British publication demonstrated “a persistent sense of amusement and condescension towards the Irish” through its cartoons fits with the Telegram evidence, with Toronto’s Catholic Irish nationalists clearly coming off worst.[115] Led by the “Paddified” Gaelic Leaguer D’Arcy Hinds, these middle-class Torontonians aiming for a constitutional solution in Ireland appear more as figures of fun than danger, however. They were romantics rather than radicals. While “the green” was no longer as vivid in the imaginations of Torontonians in 1914 as it had been in 1874, the sense of its presence remained. However the work of George Shields may have inspired casual amusement among the Telegram’s readership, it still drew boundaries between the different sorts of “Irish” in the city and within a cohort that was now mostly Canadian-born. While his cartoons resisted stereotypes based on alcohol and Fenianism, the romantic ethnic pride promoted by Hinds and others offered a less venomous source of satire. Elsewhere, one could also point to the often-idealized articulations of Irishness that regularly appeared in the pages of the weekly Catholic Register, a paper that staunchly supported Redmond’s Irish Party and retained its belief in the eventuality of home rule in Ireland after the rebellion in Dublin in Easter 1916.[116]

The recurring ethnicization of “the green” and its representatives in Toronto was therefore a two-way process of “difference-making” that utilized personalities drawn from within and beyond the city’s English-speaking Catholic community. It worked to preserve the idea of a largely benign but enduring sectarian division within “the Toronto Irish” now spared the street confrontations witnessed by late Victorian inhabitants. Though Toronto’s “Orange” and “Green” joined forces in the city’s efforts to defeat the central powers, the latent sense of two Irish tribes in the city remained for some time after 1919 as changed circumstances in Ireland led ultimately to revolution, partition, and then civil war, with unionist arguments about Ulster’s exceptionality culminating in the creation of Northern Ireland.

Parties annexes

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Patrick J. Duffy and Michael de Nie for comments on a previous draft of this article and the perceptive and encouraging comments of three anonymous referees. Versions of this article were presented at colloquia at York and McMaster universities, and the helpful remarks of participants at these sessions are acknowledged. The research assistance of Jeremy Kowalski is gratefully appreciated, as is the support of the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council through a standard research grant (award no. 410-2006-2187).

Contributor / Collaborateur

William Jenkins is an associate professor of geography and a member of the graduate programs in geography and history at York University. His published work has focused on agrarian change in nineteenth- and twentieth-century Ireland and Irish immigrants in nineteenth-century urban North America and has appeared in the Journal of Historical Geography, Immigrants and Minorities and the Journal of Urban History. He is completing a book on the comparative settlement experiences of Irish migrants and their descendants in Buffalo and Toronto between ca. 1867 and 1916.

William Jenkins est professeur adjoint de géographie et membre des programmes de deuxième cycle en géographie et en histoire à l’université la York University. Ses publications, qui ont jusqu’ici porté sur la transformation agraire en Irlande aux XIXe et XXe siècles et sur les immigrants irlandais dans les centres urbains de l’Amérique du Nord au XIXe siècle, sont parues dans la Journal of Historical Geography et la Journal of Urban History. Il termine actuellement un livre qui compare les expériences d’immigrants irlandais et de leurs descendants venus s’établir à Buffalo et Toronto vers 1867–1916.

Notes

-

[1]

See Hereward Senior, The Last Invasion of Canada: The Fenian Raids 1866–1870 (Toronto: Dundurn, 1991). It should be recognized that whether in Ireland or North America, the Fenians and home rulers did not remain strictly separate groups throughout the period. The “New Departure” of the late 1870s that brought them together in the context of agrarian conflict is but one example. See R. F. Foster, Modern Ireland 1600–1972 (London: Penguin, 1989), 400–428.

-

[2]

With a likely nod towards Paul Gilroy’s Black Atlantic, the term is coined by Kevin Whelan in “The Green Atlantic: Radical Reciprocities between Ireland and America in the Long Eighteenth Century,” in A New Imperial History: Culture, Identity and Modernity in Britain and the Empire 1660–1840, ed. Kathleen Wilson, 216–238 (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2004). See also David A. Wilson, “Introduction,” in Irish Nationalism in Canada, ed. David A. Wilson, 3–21 (Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2009).

-

[3]

Key recent accounts of the checkered history of Irish home rule are Alvin Jackson, Home Rule: An Irish History 1800–2000 (London: Phoenix, 2004); and Alan O’Day, Irish Home Rule 1867–1921 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1998). Among a vast literature on the United States, Thomas N. Brown’s Irish-American Nationalism 1870–1890 (Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1966) remains a standout work. Also noteworthy are David Brundage, “‘In Time of Peace, Prepare for War’: Key Themes in the Social Thought of New York’s Irish Nationalists, 1890–1916,” in The New York Irish, ed. Ronald H. Bayor and Timothy J. Meagher, 321–334 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996); Michael Doorley, Irish-American Diaspora Nationalism: The Friends of Irish Freedom 1916–1935 (Dublin: Four Courts, 2005); Eric Foner, “Class, Ethnicity, and Radicalism in the Gilded Age: The Land League and Irish-America,” Marxist Perspectives 1 (Summer 1978): 6–55; Michael F. Funchion, Chicago’s Irish Nationalists 1891–1890 (New York: Arno, 1976); Thomas E. Hachey and Lawrence J. McCaffrey, eds. Perspectives on Irish Nationalism (Lexington: University of Kentucky Press, 1989); Alan O’Day, “Irish Diasporic Politics in Perspective: The United Irish Leagues of Great Britain and America, 1900–14,” in The Great Famine and Beyond: Irish Migrants in Britain in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries, ed. Donald M. MacRaild, 214–239 (Dublin: Irish Academic, 2000); and Victor A. Walsh, “‘A Fanatic Heart’: The Cause of Irish-American Nationalism in Pittsburgh during the Gilded Age,” Journal of Social History 15 (1981): 187–204. Finally, Matthew Jacobson, Special Sorrows: The Diasporic Imaginations of Irish, Polish and Jewish Immigrants in the United States (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1995) puts the Irish mobilization in a wider context.

-

[4]

Margaret A. Banks, Edward Blake, Irish Nationalist: A Canadian Statesman in Irish Politics, 1892–1907 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1957); Benjamin Grob-Fitzgibbon, “The Curious Case of the Vanishing Debate over Irish Home Rule,” presented to the Second British World Conference, Calgary, June 2003. Blake was elected for the “anti-Parnellite” wing of the Irish Party, such were the factions that remained after the political downfall of Charles Stewart Parnell in 1890 and his death in 1891. For a discussion on the Land League and Irish National League branches in Toronto, see Brian P. Clarke, Piety and Nationalism: Lay Voluntary Associations and the Creation of an Irish-Catholic Community in Toronto, 1850–1895 (Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1993), 224–253, and D.C. Lyne, “Irish-Canadian Financial Contributions to the Home Rule Movement in the 1890s,” Studia Hibernica 7 (1967): 182–206.

-

[5]

See Gabriel Doherty, “The Ulster Question,” in Atlas of Irish History, ed. Sean Duffy (Dublin: Gill and Macmillan, 1997), 110–111.

-

[6]

Peter Gibbon, The Origins of Ulster Unionism: The Formation of Popular Protestant Politics and Ideology in Nineteenth-Century Ireland (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1975).

-

[7]

Philip Currie, “Toronto Orangeism and the Irish Question,” Ontario History 87 (1995): 397–409; Daniel Jackson, Popular Opposition to Irish Home Rule in Edwardian Britain (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009); and William Jenkins, “Views from ‘the Hub of the Empire’: Loyal Orange Lodges in Early Twentieth-Century Toronto,” in The Orange Order in Canada, ed. David A. Wilson, 128–145 (Dublin: Four Courts, 2007).

-

[8]

The pages of the English periodical Punch, established in 1841, have been a favoured site of investigation by historians of Ireland in this regard. See L. Perry Curtis Jr., Apes and Angels: The Irishman in Victorian Caricature, rev. ed. (Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1997); Joseph Finnan, “Punch’s Portrayal of Redmond, Carson and the Irish Question, 1910–18,” Irish Historical Studies 33, no. 132 (2003): 424–451; R. F. Foster, “Paddy and Mr. Punch,” in his Paddy and Mr. Punch: Connections in English and Irish History, 171–194 (London: Penguin, 1993); and Leslie Williams, “‘Rint’ and ‘Repale’: Punch and the Image of Daniel O’Connell, 1842–1847,” New Hibernia Review 1 (1997): 74–93. See also Michael de Nie, The Eternal Paddy: Irish Identity and the British Press 1798–1882 (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2004); Peter Gray, “‘Hints and Hits’: Irish Caricature and the Trial of Daniel O’Connell, 1843–4,” History Ireland 12, no. 4 (2004): 45–51; and Patrick Maume, “Repelling the Repealer: William McComb’s Caricatures of Daniel O’Connell,” History Ireland 13, no. 2 (2005): 43–47.

-

[9]

Curtis, Apes and Angels; de Nie, Eternal Paddy, 5.

-

[10]

Michael de Nie, “Pigs, Paddies, Prams and Petticoats,” History Ireland 13, no. 1 (2005): 44.

-

[11]

Ibid., 47.

-

[12]

See, for example, John J. Appel, “From Shanties to Lace Curtains: The Irish Image in Puck, 1876–1910,” Comparative Studies in Society and History 13 (1971): 365–375; and Kerry Soper, “From Swarthy Ape to Sympathetic Everyman and Subversive Trickster: The Development of Irish Caricature in American Comic Strips between 1890 and 1920,” Journal of American Studies 39 (2005): 257–296. Thanks to Patricia Wood, York University, for the latter reference.

-

[13]

G. Bruce Retallack, “Paddy, the Priest and the Habitant: Inflecting the Irish Cartoon Stereotype in Canada,” Canadian Journal of Irish Studies 28/29 (2002/2003): 144.

-

[14]

Finnan, “Punch’s Portrayal,” 432.

-

[15]

Brian P. Clarke, “Religious Riot as Pastime: Orange Young Britons, Parades and Public Life in Toronto,” in The Orange Order in Canada, ed. David A. Wilson, 109–127 (Dublin: Four Courts, 2007); and Martin J. Galvin, “Catholic–Protestant Relations in Ontario, 1864–1875” (MA thesis, University of Toronto, 1962).

-

[16]

William Jenkins, “Ulster Transplanted: Irish Protestants, Everyday Life and Constructions of Identity in Late Victorian Toronto,” in Irish Protestant Identities, ed. Mervyn Busteed, Jonathan Tonge, and Frank Neal, 200–220 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2008).

-

[17]

Donald M. MacRaild explores the notion of an “Orange diaspora” in “Wherever Orange Is Worn: Orangeism and Irish Migration in the 19th and Early 20th Centuries,” Canadian Journal of Irish Studies 28/29 (2002/2003): 98–117.

-

[18]

Mark G. McGowan, The Waning of the Green: Catholics, the Irish and Identity in Toronto 1887–1922 (Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1999).

-

[19]

See Ron Poulton, The Paper Tyrant: John Ross Robertson of the Toronto Telegram (Toronto: Clarke, Irwin, 1971).

-

[20]

Ibid., 13. Despite his support for the Orange Order, Robertson was never a hardened denominationalist and seems to have felt a greater belonging among the ranks of the city’s Freemasons. As Poulton notes (14), he became “Grand Master of the Grand Masonic Lodge of Canada West in 1890, travelling 10,000 miles in a single year to visit 130 lodges.” Robertson also completed a two-volume work on the history of Freemasonry in Canada.

-

[21]

Paul Rutherford, The Making of the Canadian Media (Toronto: McGraw-Hill Ryerson, 1978), 49. See also Minko Sotiron,: The Commercialization of Canadian Daily Newspapers 1890–1920 (Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1997), 114–124.

-

[22]

Robertson used his time in Ottawa to protest the Manitoba school bill in particular, using familiar Orange Order–speak about the siege of Derry in 1688 and the Battle of the Boyne in 1690. See Poulton, Paper Tyrant, 104.

-

[23]

Ibid., 132.

-

[24]

See, for example, Mail and Empire, 29 September 1928, and several other un-sourced obituaries collected in the Toronto biographies collection, film T686.3, Special Collections, Metropolitan Toronto Reference Library.

-

[25]

“George S. Shields Was Cartoonist, MPP, Councillor,” Globe, 27 December 1952. See also Scott Vokey, “Inspiration or Insurrection or Harmless Humour? Class Politics in the Editorial Cartoons of Three Toronto Newspapers during the Early 1930s,” Labour / Le Travail 40 (Spring 2000): 141–170.

-

[26]