Résumés

Abstract

Until the 1950s, most black men in Montreal worked for the railway companies as sleeping car porters, dining car employees, and red caps. The city’s English-speaking black community took root in Little Burgundy because it was close to Windsor and Bonaventure train stations. The area between Saint-Henri and Griffintown, north of the Lachine Canal, in the city’s Southwest Borough, was once known by many names. “Little Burgundy” was invented in the 1960s by city officials to describe their urban renewal plans for the area. If employment mobility was foundational in making this community, it proved just as central in its unmaking in the 1960s and 1970s. The shift from trains to cars and trucks had a two-fold impact on Little Burgundy. First, employment levels collapsed with the decline of passenger train travel, leaving many black men unemployed. Then the state built a highway through the neighbourhood to facilitate the mobility of mainly white suburban workers and consumers making their way to the central city. Next, the neighbourhood was “renewed” on a massive scale. What followed were years of dislocation and crisis. Much of the black community was dispersed as a result. It was no coincidence. The radical restructuring of North American cities disproportionately affected racialized minorities and poor whites. What was different here was that the area’s reputation for being the birthplace of black Montreal emerged after the community had been largely dispersed by urban renewal.

Résumé

Jusque dans les années 1950, les hommes noirs de Montréal travaillaient pour des compagnies ferroviaires comme porteurs et employés de wagons-lits et de wagons-restaurants. La communauté anglophone noire de la ville s’était installée dans le quartier de la Petite Bourgogne en raison de sa proximité avec les gares de trains Windsor et Bonaventure. La zone entre les quartiers Saint-Henri et Griffintown, au nord du canal Lachine dans le sud-ouest de la ville a porté plusieurs noms. L’expression « Petite Bourgogne » a été adoptée dans les années 1960 par l’administration de la ville pour évoquer leur projet de revitalisation de cette zone. Si la mobilité de l’emploi était cruciale dans la création de cette communauté, elle s’est avérée également importante pour sa dissolution au cours des années 1960 et 1970. La transition du train vers le transport routier a eu un double impact sur la Petite Bourgogne. Premièrement, le nombre d’emplois s’est effondré avec le déclin des trains de passagers, ce qui a laissé beaucoup d’hommes noirs sans emplois. Deuxièmement, le quartier a été massivement renouvelé. En conséquence, s’est ensuivi une longue période de déstructuration et de crise et la majorité de la communauté noire s’est dispersée. Cela n’était pas un hasard puisque la restructuration radicale des villes d’Amérique du Nord a affecté dans une mesure disproportionnée les minorités visibles et les défavorisés blancs. La différence ici était que la réputation de ce quartier en tant que lieu de naissance d’un Montréal noir est apparue après que cette communauté ait été largement dispersée par la revitalisation urbaine.

Corps de l’article

When it came time for us to eat in the [railcar] diner, they put a big curtain up and we weren’t allowed to eat off the menu. You weren’t allowed to stay in the hotel. Because the hotels would not have blacks in them. One time they sent me to Jasper. We stayed in the hotel, and I think the rooms were near the kitchen or something. So I go out and I see this big pool. So I jumped in the pool. My God, they pulled me out of this pool and they drained the pool. When I got back to Montreal they gave me twenty demerit marks because they had this system that if you had sixty demerit marks you’d get fired. They drained the pool…. The union said, “You are lucky that you didn’t get fired.”

—Charles Burke, Canadian National Railway Sleeping Car porter[1]

Born in the Montreal neighbourhood of Little Burgundy in April 1933, Charles Burke was hired by the railroad at eighteen. He heard that the CNR was hiring so he and his friend Earl went to the employment office at the station and submitted their applications as office boys. The following day, the company called them in. They gave Earl a slip to go upstairs and Charles a slip to go downstairs. Charles thought it strange but told himself, All right, I guess they need office boys downstairs. He was told to ask for Mr. Simpson. When Charles went downstairs, he saw trucks. “Good God, what a place to put an office,” he thought to himself. He found the room and it was a “black gentleman”:

I said, “I’m here to be an office boy.” He says, “You’re not going to be an office boy.” I says, “What do you mean?” He says, “We are going to train you to make beds and shine shoes. You are going to be a porter.” I says, “No, not a porter, are you crazy?” He says, “I talked to your mother.” And now my mother was like [Mike] Tyson. If you said anything wrong [there would be a beating]…. I says, “Don’t tell my mother. I’ll take the job. I’ll take the job.” I seen Earl the next day and I says, “Earl, they made me a porter.” He says, “What? I’m going to do something about that.” The next day I see Earl and his face was all black and blue. I says, “What is it?” He says, “When I told my father [who worked in the company’s offices], my father slapped me and laid on a beating.” … At that time, they were not hiring no blacks in the office. Blacks were either a porter or a redcap. Anyways, I took the job. But there was no [other] work. You couldn’t get work.”

Charles Burke was not alone in learning this hard lesson. Carl Simmons, a sleeping car porter on the Canadian Pacific Railway, interviewed by one of my students in 2005, recalled, “Most families, the head of the family worked for the railway. You couldn’t get another job. What other jobs could you get? There was too much racism.”[2] Others said much the same thing. Before Babsey Simmons’s father came to Montreal from the Caribbean and became a porter, he was a tailor, but “in those days, there were no jobs for coloured men whatsoever. The only job for them was on the train, as a porter, which was a very demeaning job at that point in time. They were underpaid but they did their job with dignity.”[3] Florence Phillips, whose husband was also a porter, agreed: “If they didn’t work on the train, then they worked what? Whatever they could get. It was very, very difficult to get a job here being black.” Few factory or service jobs were available to black workers. For their part, black women worked mainly as domestics in the homes of the wealthy. This began to change in only the Second World War, as a labour shortage led other employers to hire racial minorities and women. But even then, black workers got the least desirable jobs with the lowest pay. Ann Packwood recalled, “If you got a job here [in a factory] you had to be white in the daytime and you could be black at night.”[4]

Montreal’s emergence as a railway hub in the late nineteenth century led to the migration of hundreds of black workers from the United States, the Caribbean, and the Maritimes. “It was the beginning of the era in Montreal when the word porter was synonymous with the Black man,” wrote historian Dorothy Williams in The Road to Now.[5] Until the 1950s, most black men in the city worked for the railway companies as sleeping car porters, dining car employees, and redcaps. Historian Sarah-Jane Mathieu, in North of the Colour Line, argued that the Pullman Palace Car Company “permanently fixed the image of black men to the railroads with the introduction of its opulent sleeping cars in 1865.”[6] This racial practice was exported into Canada when Pullman introduced its palace cars here in the 1870s. The Canadian Pacific Railway and the Grand Trunk (later part of the CNR) followed suit.[7]

Montreal’s English-speaking black community took root in Little Burgundy because it was close to the Windsor and Bonaventure train stations. The area between Saint-Henri and Griffintown, north of the Lachine Canal, in the city’s Southwest Borough, was once known by many names: Saint-Antoine district, Ste-Cunégonde, Faubourg St. Joseph, the West End, even as part of Saint Henri. The multiplicity and fluidity of the area’s identity stood in sharp contrast to the more fixed identities of the adjoining neighbourhoods. The area’s multiracial character may have had something to do with this indeterminacy. Neighbourhood identity became fixed as “Little Burgundy” only in the 1960s after city officials adopted this name to describe their ambitious urban renewal project for the area bounded (see figure 1) by Guy Street (to the east), Atwater (to the west), the Lachine Canal (to the South), and the escarpment (to the North). Once described as part of the “city below the hill” by social reformer Herbert Ames, who documented the area’s poverty in the 1890s, Little Burgundy was also tied to the factories lining the banks of the Lachine Canal as well as the smaller ones scattered within its boundaries.[8]

Figure 1

The Montreal neighbourhood of Little Burgundy. The shaded area marks the îlots Saint-Martin, the first phase of the urban renewal of area.

This article points to the ways that employment mobility—where workers live in one locality but work in another—over the longue durée of the twentieth century made and remade this inner-city neighbourhood. For decades, the black community was extraordinarily dependent on railway employment. The decline of passenger train travel in the 1950s and 1960s therefore hit the community hard. Hundreds were laid off. At the same time, the shift from trains to cars and trucks led to the spatial reorganization of the city. New highways were built to bring white suburban workers and consumers downtown. Then a huge swath of the neighbourhood was demolished to make way for a new public housing project. Many black families moved out of the neighbourhood as a result of these changes, never to return. After renovation, there was little room for black homeowners and those with steady jobs. The geographic dispersal of the Anglo-black community, and the undermining of black-owned businesses and institutions, weakened their contemporary link to Little Burgundy just as its historical presence finally became firmly established in public consciousness.

Despite the transformation of the area, or perhaps because of it, Little Burgundy is now synonymous with black Montreal and the romance of the city’s jazz age, embodied by musicians like Oscar Peterson and Oliver Jones, or clubs like Rockhead’s Paradise. This was not always the case. Newspaper evidence makes clear that during the years leading up to and during urban renewal, Little Burgundy was not publicly represented as a racialized neighbourhood or (much more accurately) as a multiracial one. As the area had a clear white majority of French-speaking residents, white policymakers, urban planners, and media commentators viewed the area instead through a Quebec neo-nationalist lens where poverty was attributed to disparities between French and English. Ethnic (or linguistic) class, not race, was the dominant paradigm, thus submerging any recognition of underlying racial discrimination or of even the black presence. It was only years later, after the neighbourhood had been renewed with the highest concentration of public housing in the province, at a time when the area had become associated with crime and crack cocaine, that Little Burgundy’s black presence and history were finally recognized by others. However, by then the state had imposed a prescription to a problem that failed to consider the particularities of the black community, tearing asunder a social fabric that had served black Montrealers well.

The Black City Below the Hill

In the beginning, the heart of Montreal’s black community was concentrated east of Guy Street and west of Peel, near Rockhead’s Paradise and other jazz clubs, in the immediate vicinity of the train stations, before drifting westward to the area known today as Little Burgundy. The expanding central city made this geographic shift necessary. When asked what the area on the east side of Guy was called historically, Mary Wand laughed nervously and asked, “Well, can I say it?” Dorothy Williams, a black historian, invited her to proceed. Only then did Wand reply hesitantly, “It was called ‘Nigger Town.’ And it was predominantly black” in the 1920s and 1930s.[9] The population’s shift westward was caused by the expanding downtown commercial district and the consequent loss of residential housing in that area. Interviewed in the early 1980s, Mr. and Mrs. Packwood were part of this geographic shift as they remember moving to Lusignan Street (just West of Guy) in the 1920s, while there were still white lawyers, white doctors, and other white professionals living on Saint-Antoine and adjoining streets. “There were judges living on Richmond Square, and people of means,” they recalled. However, the white middle class moved out shortly after the First World War, as blacks began to move into the area. In Montreal, as elsewhere, abandonment and ghettoization have “complex and interwoven histories of race, residence, and work.”[10]

Figure 2

Quebec might not have had a system of legal segregation, as in the southern United States, but it did have a history of slavery and racial discrimination. Going into a bar, restaurant, cinema, or store for the first time, blacks never knew if they would be served. Proprietors had the right to serve whomever they wished, so there was always uncertainty. Fred Christie, a black man from Verdun, for example, was refused service at a bar at the Montreal Forum (Canada’s hockey palace) in 1936 and he took the case to the Supreme Court of Canada.[11] He lost. There were also cases of black tourists being refused hotel accommodation during Expo 67.[12] Even Bentley Adams, the prime minister of Barbados, a black man, was refused a room at a major hotel during a visit to the city in 1954.[13] These are only the cases that made headlines.

Archival research and oral history interviews confirm that anti-black racism was a fact of life in Montreal throughout the twentieth century. As Emily Robertson noted in a 2017 oral history interview, racial discrimination in Canada was often “a subtle business, you know, subtle business … If you go to a restaurant you were the last person they would come to serve.”[14] Racial discrimination in housing and employment are at the heart of this article, but it extended to all aspects of life, including mass transit: being kicked off of buses, left standing at bus stops, or victimized by racist taunts and comments. Florence Phillips recalled that she was frequently called names on city buses: it “didn’t make any difference what you wore.”[15] In June 1980 the Negro Community Centre’s (NCC) Vera Jackson wrote to the director of Montreal’s transit authority to say, “Again it has become necessary to write you concerning an incident involving one of your employees and a member of the Black community.… Police were called and they gave as their opinion that the individual bus driver has the right to make his own rules as concerns his bus.”[16] Policing itself was another flashpoint.[17] Historically, NCC Director Lawrence Sitahal told the media in 1986, “the Black community often finds itself the victim of police brutality and discrimination.”[18] The Centre for Research-Action on Race Relations had issued a major report two years earlier, detailing the magnitude of the problem in Montreal.[19] It makes for sobering reading.

While there were fewer legal barriers to mixed neighbourhoods in Montreal than in the United States, everyday racism limited housing choices. White landlords often refused to rent to black people. E.L. Swift, a leading black trade unionist in the Canadian Brotherhood of Railway Employees, told those gathered in 1960, “I have to tell you that as Negroes we have experienced severe acts of discrimination … especially in housing.”[20] At the same event, Ann Packwood agreed: “Renting a house is often a most embarrassing affair.” As a result, “most negroes lived in the lower St. Antoine district because of current barriers against them in housing elsewhere.”[21] Even so, starting in the 1940s, there is evidence of black suburbanization as families moved to other parts of the city. A wartime list of the addresses of every Montreal black porter working for the CPR at the time confirms this trend, as do oral history interviews. Mr. Chandler, for example, recalled that most CPR porters with seniority “had their own homes elsewhere like over the river, or in NDG [the Notre-Dame-de-Grace neighbourhood].”

The residents of Little Burgundy grew up with trains all around them. CPR trains ran above them along the escarpment, the CN tracks and yard ran through the neighbourhood itself, splitting it in two (between what is today Saint-Jacques and Notre-Dame), and more tracks served the factories alongside the Lachine Canal. It was therefore a vibrant, if noisy, part of the city.[22] “For a long time, that physical barrier of the railroad tracks was there,” recalled Abel Lewis. “You had an upper Little Burgundy and a lower Little Burgundy.” Interviewees recall that people on one side of the CN tracks did not associate much with those on the other side. Charles Burke, the porter quoted in the epigraph, recalled that some parts of Little Burgundy were “all French. And we always fought [as kids]. You had to become a fighter or a runner.” Charles was a runner. “I was a hell of a track star,” he smiled. “You had to know the rules of the neighbourhood or else you got your butt kicked.”

Sometimes kids took shortcuts across the tracks or played on railway lands, as there wasn’t much green space before the urban renovations. Abel Lewis told us about how he and his friends used to play cat and mouse with the CN Police: “There was a big empty railroad yard. That’s where we played most of our games because [that was] before the parks were built. There was only one park: Campbell Park. It was about half the size that it is now before they renovated it.”[23] The railway police “felt that it was very dangerous for us to be playing there and we totally disagreed with that.” One day, Abel and his friends thought that they would get even with one policeman in particular: “There was that railroad car with about half a dozen old lettuce heads because they used to leave that stuff in the car and take out later, and there was that one CN police [man] that used to throw us out always, we used to hate him. So one day we just got a whole bunch of lettuce heads, and there was a factory that used to be right near the railroad yard, so when he drove by on his patrol we just bombarded him with lettuce heads.”

Figure 3

Looking north up Atwater Street before urban renewal. Notice the CNR rail crossing in the foreground. No date.

For his part, Charles Burke told us about how he and his friends would sometimes break into freight cars on the way home from elementary school and steal boxes of cherries or other fruits. Sometimes they would also hop onto a moving train at Guy Street and jump off when it reached de la Montagne (Mountain) Street to speed their journey home from school. But one day one of his friends slipped and the train ran over his arm. Charles Burke never rode the rails again, but he got into plenty of other trouble. It was a rough part of the city. He recounted a story, clearly one of his favourites, about when his mother sent him out to get nails from the hardware store:

These guys cornered me and took the money. Then I went back home and my mother kicked my ass and she told me to go back and get the nails. So I ended up in a corner and some old Italian man befriended me and I got the nails. And I brought the nails home and he recruited me. Because there was a pool hall down at the corner, so he recruited me. All the young guys, we used to go up to the Forum when they had the wrestling. He would make us sell the little mickeys of liquor. We would sell them and we would get a couple dollars a bottle.… Then I graduated into learning how to pick pockets, so I became the number one pickpocket in the neighbourhood. They would call me to go and pick pockets. That wasn’t too far from Mountain and Saint-Antoine, to go to Rockhead’s Paradise, and then they had another club called the Saint-Michel across the way. I wasn’t too far from the docks. When the boats came in, the guys would come up to the clubs and we would approach them and say, “You looking for girls?” and pat them down and pick their pockets. The neighbourhood bully, any pocket that you picked you had to give him a part of the action…. I remember one time I picked a pocket, and there was close to two hundred dollars. I took the money home, but I was tired because I was young. I was a real renegade, and I was hanging out all night. And I went home and fell asleep and my mother came in and took all the money. She said, “I am going to buy you some clothes and that’s it” [laughs]. My mother was one of those mothers that would slap you before you could open your mouth. So, funny, one of the hustlers said, “I heard you made a big score. Where is my end?” I said, “Listen, my mother took all the money.” He says, “You tell your mother that that money is mine.” “You don’t want to mess with my mother.” This guy goes, and my mother hit him with a broom all the way up the street. He didn’t get any of the money.

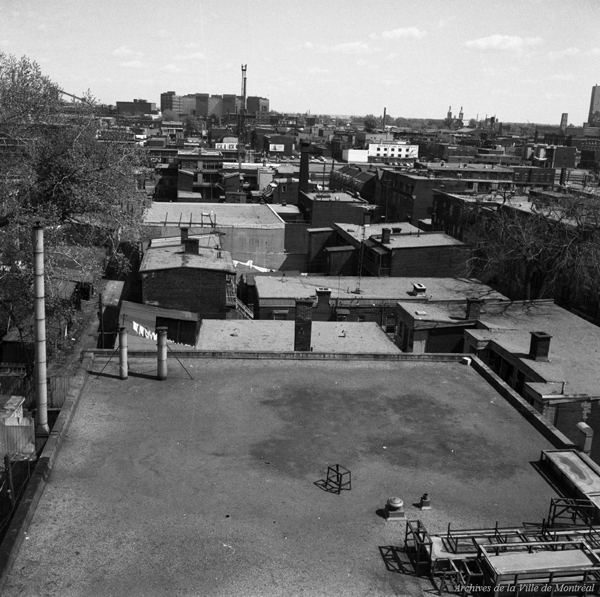

Figure 4

Looking south from atop the Canadian Buttons Ltd. factory on rue Saint-Antoine in Little Burgundy. Northern Electric’s Shearer Street factory in Point Saint-Charles is in the distance. 30 May 1967.

Figure 5

Others fondly remember growing up in a neighbourhood full of life. Many recalled watching open-air movies in Chatham Park or swimming in the Lachine Canal. Little Burgundy used to have many shops, restaurants, and taverns. “We used to have a lot of taverns, one on every corner,” recalled one man. There were also small industries on otherwise residential streets. English-speaking kids went to Royal Arthur, St. Anthony’s, or Belmont schools; French-speaking kids went to St. Joseph’s. Royal Arthur School appears to have had the highest concentration of black children, even before it became the last English school in the area. Almost everyone spoke of the neighbourhood’s special place in the city’s jazz scene during the 1940s and 1950s. According to Richard Lord, “For entertainment, we had Rockhead’s Paradise. And it was very fancy, sophisticated, because Mr. Rockhead only had the best shows, most of them coming in from Detroit and so forth at Rockhead’s Paradise. In the district of Little Burgundy, they had some outstanding musicians. Of course, everybody knows Oscar and Oliver Jones. But Oscar Peterson’s brother was very good too. He played the trumpet. And a lot of people in this district were very musically oriented.”[24] Rufus Rockhead is said to be the first black man to get a liquor licence in Montreal. James Franklin, originally from Halifax, worked at Rockhead’s for thirty-one years. He started out as a cleaner but slowly worked his way up to waiter, doorman, and finally maitre d’hôtel. He recalls all kinds of famous entertainers passing through Montreal such as Nat King Cole, Redd Foxx, Nipsy Russel, and many others.[25] These interviews remind us that Little Burgundy was very much tied into wider black networks, with frequent contact with Harlem, Detroit, and other centres of twentieth-century black culture.[26]

Black porters might have had the most poorly paid jobs on the railway, but they enjoyed high status within their community. “In the black community,” observed historian Dorothy Williams, “the railroad workers had status, prestige, and later, an image of professionalism.”[27] Black porters were often highly educated, as the CPR in particular recruited its porters from the black colleges of the southern United States.[28] They were also well travelled. Mobility had its advantages, contributing to the rising political awareness of shared socio-economic and political problems facing blacks across North America. Sarah-Jane Mathieu goes so far as to say that porters were at the political vanguard and helped produce a “powerful diasporic consciousness” in North America.[29]

Figure 6

There is ample evidence of this leadership in Little Burgundy. Sleeping car porters and their wives helped found virtually every major community institution before the 1960s. The Colored Women’s Club, for example, was formed in 1902 by fifteen wives of sleeping car porters. The local branch of the Garveyite Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA), created in 1919, was likewise formed by porters and was first located in a CPR building on Saint-Antoine, where the company housed its non-resident sleeping car porters.[30] The best-known member of this branch was Louise Langdon, mother of U.S. Black Power leader Malcolm X. For its part, the Union United Church, established in 1907, also had a strong connection to porters. In his history of the church, David Este wrote that a “small group of American-born railroad porters felt the Bethel AME Church was not meeting the requirements of all Blacks in the community. Motivated by the need for unity to avoid the discriminatory practices of the White churches and the desire to control their own institutions, the porters, after considerable discussion and debate”[31] formed a new church. The Reverend Charles Este, who came to Montreal in 1923 from Antigua, worked for a time as a porter and would later serve as a chaplain for one of the railway unions. Even the father of jazz legend Oscar Peterson was a railway porter. Most early black professionals in the city—social workers, lawyers, engineers, university teachers, and medical doctors—were able to go to university because of the paycheques of their fathers who worked the railroads and a commitment to education that ran deep within these families.

The Negro Community Centre, another important hub, formed in 1927, also had a strong connection to porters. Stanley Clyke, born in 1927 in Truro, Nova Scotia, worked as a porter for the CPR for eighteen years before getting his social work degree at McGill and becoming the NCC’s long-time director. From 1927 until its closure in 1991, the NCC provided cradle-to-grave services for the community. For children, it offered school lunch services, a free milk program, pre-school, sports, as well as piano, dance, art, and drama lessons. Children attending the NCC summer camps learned about Africa, slavery, and black pride.[32] In the 1960s and 1970s its cultural camps were named after international icons like Malcolm X, Marcus Garvey, Jean-Jacques Dessalines, and Patrice Lumumba. Children participated in skits re-enacting the work of Harriet Tubman and the Underground Railroad. The NCC even used its Umoja sports program to the same ends. Umoja means “unity” or “unite” in Swahili. Team names in the 1970s included the Ebonies, the Africans, Trotters, Black Heritage, and Chocolate City.[33] And each year basketball players showed their stuff during the Martin Luther King Basketball Tournament. At year’s end, the most outstanding female athlete received the Malcolm X Memorial Trophy, and the most sportsmanlike player got the Marcus Garvey Trophy.[34] Certificates of achievement were given to those graduating from high school. Adults also had a variety of programs serving their needs, including health clinics, a young mothers program, and a library of black culture and history. “Every weekend,” recalled Valerie Hernandez, “you had some place to go. And that was the focal point: the Negro Community Centre.”[35] It is thus significant that a strong identification with place emerged in the Little Burgundy area despite the employment mobility of men.

Black Railway Workers and the Fight for Jobs and Equality

The thick web of family and community within the neighbourhood extended onto the passenger trains that criss-crossed the country. Sons followed fathers and grandfathers onto the sleeping cars. As old porters came to retirement, a ritual formed in Little Burgundy where the man’s family, friends, co-workers, and bosses would greet him on his return from the final run. Retirement notices in the Black Worker, a union newsletter, highlighted such cases, often accompanied by photographs. C.D. Bourne served twenty-eight years on CPR trains, starting 6 June 1922, before completing his last run on 13 June 1950. He had six children, all high school graduates, with a son in dentistry, and a daughter who was the organist of their church.[36] For his part, J.L. Lord retired after thirty-six years of service in 1955 after making his final trip back from Saint John, New Brunswick. He was met by a throng of friends and family, including several family members in uniform. One of these was Richard S. Lord, later interviewed by one of my students in 2005.[37]

Employment mobility was foundational to Montreal’s black community: “But it was a tough life. Sleeping car porters were required to take care of the linen, blankets, pillows, and towels; make up and take down sleeping berths; awaken passengers; handle their luggage; guard their possessions against theft; clean the car; clean the washrooms and smoking rooms; polish the boots of passengers; and ensure the safety of passengers.”[38] Porters were therefore vulnerable to public complaints. They were trained to be courteous, even when confronted by everyday racism. Carl Simmons told us about how his father, also a porter, explained to him at a young age how things were. He saw everything during his years of service. They worked impossibly long hours. In the 1920s and 1930s there was no limit to the hours that they worked per day or per month. They were paid a fixed monthly salary of $87, no matter the actual hours worked: that number depended on the train assignment.[39] For example, sleeping car porters on the Montreal to Moncton run were on duty for 321 hours and 50 minutes per month. While on the road, they were on duty 43 hours after deducting six hours’ sleep—three each night, coming and going. There was no overtime. “No human being, under any circumstances, except to save life, should be asked to work such long hours as to seriously impair his health,” protested workers in 1927.[40]

The nature of the job required that black men be away from their families for large blocks of time. “I travelled this whole country,” recalled Mr. Chandler, who worked for the CPR from 1954 until 1966. He’d travel from Montreal to Vancouver and 1400 miles back again: “You would be travelling overnight, leaving there at 8:30 on a Friday night and arriving in Winnipeg at 8:35 Sunday morning. Remained in Winnipeg until Monday afternoon, report at work at 5:30, leave at 7:20 and be back in Montreal on Wednesday morning.”[41] Priscilla Gerald’s husband also travelled the country. Asked if she also had the chance to see Canada, she replied matter-of-factly, “No, I had to stay with my children.”[42]

Figure 7

Two porters assist passengers and other crew at the railway station in Jasper, Alberta, 1929.

For her part, Babsey Simmons agreed that her mother mostly raised her, but she was supported by her extended family and community institutions. Her father’s prolonged absences didn’t affect her negatively. It was considered normal. Others found opportunity. Charles Griffith’s father was on the Vancouver run sixteen days a month. As his father did not approve of his taking up tap dance at Union United Church, “that’s when I danced,” he smiled. When his father was home, he had to be careful: “I used to climb down from the second story on gas piping, find my tap shoes in a shed, and go dance. I had to climb back up the pipe into my bedroom window to go to sleep.” He just had to dance. But the prolonged time away from home also placed terrible pressure on families, and some marriages did not survive. This was the case with Charles Burke, who regrets not spending more time with his wife and kids. Out of necessity, families, like community organizations, were moulded around black male employment on the railway, addressing some of the problems that this employment incurred.

At first black porters got no help from white unions. Instead, white railway unions reinforced racial segregation in Canada, as in the United States, excluding blacks from union membership or relegating them to auxiliary status. White supremacy was the rule. In response, black porters in Canada formed their own union in 1917—the Order of Sleeping Car Porters. This was the first large black union in North America. Black trade unionists faced fierce opposition from the railways, which wanted cheap and docile porters. While the union managed to establish itself on the CNR, the anti-union CPR promptly fired the order’s black organizers. When the order applied to Canada’s Trades and Labour Congress for a charter, its application was referred to the Canadian Brotherhood of Railway Employees (hereafter Canadian Brotherhood), which had jurisdiction. The Canadian Brotherhood was an all-Canadian union, something rare at the time, as most unions were U.S.-based. It also organized workers industrially, meaning that it sought to organize almost all classes of railway workers. Yet to accept the Order of Sleeping Car Porters, the Canadian Brotherhood first had to eliminate the “whites only” clause in its constitution. The first try failed in 1918, but another the following year succeeded—making it amongst the first unions in Canada to abolish racial restrictions to membership.[43] Black railway workers were now full members, organized into four all-black local unions. Two of them—Local #104 and #128—were based in Little Burgundy.

Figure 8

Montreal Mayor Camillien Houde and Lord Bessborough (flanked by two sleeping car porters), 1930.

In the collective agreement, Black workers were put into their own seniority group—which meant that they were ineligible for promotion. Until challenged in the 1960s, a black porter remained one until retirement. Blacks employed in the dining cars as waiters and cooks found themselves on the defensive, as the CNR ended the practice of hiring blacks as waiters in the 1920s. Gradually their numbers dwindled until there were only black cooks left.[44] Racial segregation at work, however, meant that black workers had a lock on certain occupations, which led to large numbers being employed in the first place. Their pay may have been low, but porters could draw on their tips and developed other strategies of making-do.

Black trade unionists on the two railways worked hard to improve their conditions. “They fought for more rights, and more rights,” recalled Richard Lord. According to Carl Simmons,

Guys got together, black guys, working on the railway. Those worked as porters and club cars, and they said, “Why is it we can’t be in dining cars, too? Why is it we can’t be waiters in the dining cars?” The guys working out of Halifax, one time, wanted to stop shining shoes because some of them had rashes on their fingers. And so the government of Nova Scotia said, “You don’t have to shine shoes no more.” But you know what happened? That was only in the province of Nova Scotia. An hour and a half after you leave Halifax you’re in the province of New Brunswick and then you are in the province of Quebec. And Quebec and New Brunswick didn’t go for that. They said that it was none of our business.

To thwart unionization, in 1917 the CPR set up the Porters Mutual Benefit Association, a company union. CPR porters did what they could to provide sickness and health benefits, and settle grievances. Charles Ernest Russell, born in Barbados in 1883 and active in Union United Church and the UNIA, chaired it. In May 1939 he secretly approached A. Philip Randolph, a future civil rights icon, and then president of the U.S.-based Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (BSCP, an all-black union formed in 1925), and asked it to organize the CPR porters.[45] Russell wrote, “There are a great many of us who feel that the present time is most appropriate for us to become organized.” In response, Randolph travelled to Montreal that July to speak to a large public meeting at the UNIA hall. A successful union drive followed, winning their first contract in March 1945. The Montreal division had signed up 189 of 277 employees.[46] All railway porters in Canada now belonged to either the Canadian Brotherhood or the BSCP. One union was racially integrated, at least in theory, and the other was all-black. Each union, in its own way, was a product of the prevailing racism that restricted railway employment.

In North of the Colour Line historian Sarah-Jane Mathieu has condemned the actions of the Canadian Brotherhood and its leadership as racist: “Aaron Mosher [union president] set much of the tone for race relations in Canada’s labor movement, lending his union’s full-throated support for white supremacist dogma.”[47] But does the evidence support this wholesale condemnation? I am not so sure. Part of the problem is that Mathieu relies almost entirely on the historical records of the BSCP, a rival union, found in the United States. She largely fails to delve into the history of black militancy and resistance within the Canadian Brotherhood itself. This was a missed opportunity. She also fails to fully acknowledge that the Canadian union was probably the first railway union in North America to accept black membership. On the one hand, she condemns the Canadian Brotherhood for preserving its all-black locals, but on the other heralds the BSCP for doing much the same thing. In both cases, black railway workers were institutionally prevented from gaining promotion—though sociologist Agnes Calliste found that the Canadian Brotherhood was more effective in dismantling these barriers, albeit under pressure from its own black members.[48] Let me share two examples that further nuance Mathieu’s story.

The first relates to the immediate aftermath of A. Philip Randolph’s successful drive to organize CPR porters, and the negotiation of its first collective agreement in 1945. Fresh from his victory, Randolph called on the CNR porters to abandon their own union and join the BSCP. Mass rallies were held across the country in June and July 1945, drawing thousands. Again and again Randolph told those gathered, “The central social issue of these times is the question of race and color.”[49] By then Randolph was a civil rights superstar in the United States—having organized the wartime March on Washington movement for fair employment. As Randolph toured the country, the white leadership of the Canadian Brotherhood received urgent reports warning them that the union risked losing all of its sleeping car porters unless certain reforms were undertaken. S.H. Eighteen, the Montreal-based general chairman of the Sleeping, Dining and Parlour Car Division, and the senior black official in the union, wrote President Mosher to say that black members wanted a black man to represent them on staff:

I am not at all satisfied that the appointment of a coloured representative without authority to take grievances to the Management will satisfy them. They have made up their minds that no white man can understand their racial problems, and [they] feel that while they are coupled up with white dining car employees they will always be discriminated against on account of their colour. It is my opinion that whatever we do for them they will never be satisfied until they have complete autonomy amongst themselves, and have no white man interfering in the administration of their agreement insofar as it affects them.[50]

Eighteen then warned that the arrival of the BSCP from the United States was having a powerful effect “upon the coloured members of our organization.” Mosher heard similar reports from Toronto and Winnipeg. W.W. Overton, chairman of the Toronto Local, wrote to say that Randolph “served an argument of much truth, and in plain language.” He, too, called on the union to employ a “race representative to organize and help with our Grievances” before it was too late.[51]

Clearly alarmed, Mosher wrote to all the union’s porters to make the case for the Canadian Brotherhood, and against Randolph’s BSCP. Mosher declared that should the U.S. union be successful it “will result in race distinction in Canadian labour organizations and retard, if not completely break down, the efforts of the CBRE during the past thirty-five years to eliminate race distinction. From the very inception of the Brotherhood its policy has been to accord equal status to all workers in the transportation industry without regard to race, creed, or color.”[52] Mosher then noted that black porters in the United States had no choice but to create their own organization, as none of the white railway unions would have them. This was not the case in Canada. Not surprisingly, the circular did not put out the fire and Mosher finally relented, agreeing to hire E.L. Swift as special representative.[53] In return, black trade unionists stuck with their interracial union. In the years to come, black railway workers would rise to senior positions in the Canadian Brotherhood, revealing once again the dual nature of integration as a tool of both liberation and oppression.

Figure 9

A. Philip Randolph shakes hands with Canadian BSCP leader A.R. Blanchette in Montreal in 1957.

The second example comes from the late 1950s. The postwar decline of passenger travel put considerable pressure on black railway workers, as employment declined precipitously. Things came to a head in 1958 and 1959 when CN decided to take over operation of the remaining Pullman palace cars on its trains. This mattered, as the BSCP represented porters on these cars, whereas the Canadian Brotherhood represented those on the rest of the train. The change would mean that 160 Pullman employees faced job loss, unless the Canadian union could be convinced to give them “homestead rights.”[54] If accepted, Pullman porters would become members of the Canadian Brotherhood, albeit second-class ones, as their seniority “would be limited to those services now being performed by the Pullman Company.”

Randolph travelled to Toronto to meet with the Canadian Brotherhood about the matter. The Canadian leadership was sympathetic and strongly recommended homestead rights to its membership.[55] But this proposal faced stiff resistance from black trade unionists. The feeling was “we have to look after our own first,” as a growing number of CN porters had been laid off.[56] The union’s white national leadership pushed back, calling for a vote of members, and Randolph appealed to them directly in a March 1959 letter: “Now, I am addressing this letter to you as fellow brothers of the Sleeping Car craft of the CNR, in behalf of the Pullman Porters who are now sentenced to their economic death, to extend them your hand of cooperation.”[57] He appealed for racial solidarity as well: “Unfortunately, because of race and color, they will have nowhere to turn to look for employment in the Canadian community.”

The national union supported Randolph, countering suggestions that giving homestead rights would lead to more layoff. A March 1959 circular from the union’s national president, co-signed by S.H. Eighteen, argued, “The fate of this group of Pullman Car employees is a most unhappy one and stark tragedy stares many of them in the face unless some arrangement can be made to extend to them a helping hand. These men are faced with the total loss of employment in many cases after long years of service, through no fault of their own. They face the grim prospect of being thrown onto the ever-mounting pile of discarded workers, not because their jobs ceased to exist, but simply because management over their work has changed hands.”[58] The union proposed to give homestead rights to fifty-seven Pullman porters with a minimum of ten years’ service, with twenty-two having more than twenty years’ service.[59] Half of these men lived in Montreal.[60] Once again this appeal to class and racial solidarity failed to convince. CN porters voted down the proposal, 243 to 45, with similarly one-sided votes in the two Montreal union locals.[61] It wasn’t even close. As a result, the president of the Canadian Brotherhood expressed his bitter disappointment, warning that they could be next as railway employment continued to contract.

Declining employment in the railways also contributed to rising demands for racial equality. The campaign to dismantle employment segregation on the railways, waged by black workers, faced considerable opposition from fellow white trade unionists who were amongst its chief beneficiaries. In October 1957 Lee Williams, chair of the Winnipeg local, wrote the president of the Canadian Labour Congress, calling for an end to employment discrimination on passenger trains.[62] Canada had passed the Fair Employment Act in 1953, which made race and gender discrimination illegal in areas of federal jurisdiction. So, why then, were black trade unionists still prevented by their collective agreement from being promoted? Sleeping car conductors had been organized by the Canadian Brotherhood before letting the porters join. As a result they were organized into different local unions and different seniority groups. Since 1927 the collective agreement created two categories of employees: one comprising mainly white dining car employees and sleeping car conductors, and the other black porters. The collective agreement therefore effectively blocked promotion for black porters. As Williams explained, “The menace of unemployment and layoff intensifies the desire of members of each Group to hang on to their job and seniority rights they already have, and perhaps to try to expand their own employment opportunities.”[63]

Figure 10

A porter takes luggage for passengers about to board “The Dominion” at Montreal’s Windsor Station, circa 1947.

The effort to merge these two groups was met with fierce resistance. The union’s leadership had sought to merge the two groups earlier in the 1950s, but to no avail as white rank and file members voted against it twice. Lee Williams therefore went public.[64] In July 1963 he lodged an official complaint under the new anti-discrimination law. Williams was supported by the three other black union locals. For his part, D.E. Fenton, chairman of Local 128 in Little Burgundy, protested the delays in eliminating “the traditional division of sleeping car and dining car employees into two groups—one group comprising conductors, stewards, cooks and waiters and the second group for porters.”[65]

CNR porters were opposed to going to another membership referendum, as this was a civil rights issue and should not be subject to majority rule,[66] and they boycotted a referendum held in 1964. However, thanks to the manipulation of the referendum question by the union’s white leadership, this time the vote favoured the merger of the two bargaining units.[67] On the face of it, the membership voted against the merger 196 to 111, with 536 abstentions. But this time the motion put to a vote asked if they were “not in favour” of the merger. According to the union constitution, abstentions were counted as being in opposition to the motion. The negative wording of the motion thus allowed the union to count the abstentions as being in favour of ending race segregation.[68] Not democratic, perhaps, but effective. The CPR, by contrast, maintained its segregationist seniority practices until passenger service was taken over by VIA Rail in 1978.

With an end to job segregation, the CNR and CPR ended their practice of hiring only black workers for certain job categories. According to sociologist Agnes Calliste, the railways no longer “had a vested interest in employing them.”[69] Henceforth, there were fewer jobs for black workers. “It’s not like before,” sighed Priscilla Gerald. “When we came here anyway,” she recalled “there was a place for black people, especially with the railroad.” Mr. Chandler was one of those who lost his railway job during these years. When he started, “it was one of the best jobs you could get for a black man. Now there’s no room for the black man on the train because most of the porters are white. The pay is very good.” But he didn’t have the seniority. When he joined, he was 222 on the seniority list. When he was laid off, he was number 98. With no more incentive to hire black workers on the railway, desegregation, too, came with a price tag.

Race and Urban Renewal

Job losses on the railway were occurring at the very moment when the industrial foundation of Southwest Montreal was crumbling. One by one, the great industrial employers of the area closed their doors. Some industries relocated to greener suburban or provincial pastures, others closed for good.[70] Manufacturing employment fell a staggering 70 per cent between 1967 and 1988.[71] Working-class neighbourhoods emptied out during these years, with the Southwest Borough losing half of its population between 1961 and 2001.[72]

A major report released in 1989 highlighted four major reasons for the economic decline of the area.[73] The shift away from railway transportation to transport trucks favoured suburban locations with easy access to highways and other cities. Downtown areas were congested, making them hard to get to. The opening of the St. Lawrence Seaway in 1959, and the staged closure of the Lachine Canal, was another factor in the area’s decline. But even more important was the advancing age of industrial buildings. Multi-storey industrial buildings were largely seen as being incompatible with modern production methods. The physical limitations of the industrial sites also gave manufacturers no easy way to expand their operations. All of these issues factored into industrial decline, as well as a rapidly changing global environment of trade liberalization and fierce foreign competition.[74]

Yet the depopulation of Little Burgundy and other Southwest Montreal neighbourhoods was not only the result of deindustrialization. The shift from trains to cars and trucks had a three-fold impact on Little Burgundy. First, employment levels collapsed, with the decline of passenger train travel leaving many black men unemployed. Then the state built a highway through the neighbourhood to facilitate the mobility of mainly white suburban workers and consumers making their way to the central city. Much of the black community was in the northern half of the neighbourhood, concentrated along Saint-Antoine. This was precisely the area targeted by the city for the highway. Then the rest of the neighbourhood underwent urban renewal on a massive scale. These developments were integrally connected.

The building of highways and the Metro system also encouraged upwardly mobile industrial workers to move to middle-class neighbourhoods. Even then, moving up often meant moving out. In October 1965 Stanley Clyke, the NCC’s executive director, wrote, “The City of Montreal has recently announced Urban Renewal of a part of the area once thought of as the core of the Negro community. The English-Speaking Protestant population of the area is rapidly decreasing; Negroes have moved and are continuing to move to new suburban areas…. Meanwhile, in the neighborhood of the Centre, a core of Negro people still exist, some in distressingly substandard housing; others have bought homes there and repaired them in the hope of permanent occupation.”[75]

These comments suggest that the dispersal of Montreal’s black community was already underway, and urban renewal just finished the job. By the 1960s Little Burgundy was cast as an urban slum in need of state intervention. Priests in fourteen parishes in Montreal’s Sud-Ouest published a letter in December 1964 protesting the inhuman conditions prevailing in the area:, where “cold-flats” with no running hot water was still common. Their public appeal generated considerable media attention, leading the city’s Jean Drapeau–Lucien Saulnier administration to designate 265 acres of St. Joseph and Sainte Cunégonde parishes (in what is today Little Burgundy) the “pilot zone” for urban renewal in the city: the first phase of a “long-range, multi-pronged program of urban renewal.”[76] Over the next seven years, nearly 800 newspaper articles on the urban renewal scheme found their way into the vertical files of the City of Montreal.[77] At first the media struggled to locate the renewal project, as the names for the area were multiple and fluid. Eventually everyone settled on using “la Petite Bourgogne” or “Little Burgundy” in quotation marks: the name given to the project by the city. Hundreds of articles later, the quotation marks eventually came off.

According to the detailed report of the city, used to justify the clearance, the pilot area was characterized by three-storey row-housing, and home to 16,997 people, 70 per cent of whom were francophones. According to the white urbanists writing the report, “The atmosphere of the study area is bleak and forlorn. The narrow streets, squeezed between long rows of grey and anonymous houses, leave little room for sunshine and even less for a bit of greenery.”[78] The authors note the physical, economic, and population decline of the neighbourhood: “The study area is made up of older parishes which were formerly very large and prosperous.”[79] As the Montreal Star reported, the study was comprehensive: “The pilot zone for Montreal’s slum-clearance program has been sifted house by house and its history retraced so that city councillors will be as familiar with its problems as if they lived there.”[80]

Figure 11

The early phases of urban development began with the Ilôts Saint-Martin (#1 on the map) and followed with Quesnel-Coursol (#2).

And yet there was no mention of race in the report. Black residents, their institutions, and their history were rendered invisible by the report’s focus on poor white francophones.[81] Nor was there mention of black Montrealers anywhere in the hundreds of media reports published in the years that followed. Instead, they were subsumed under the linguistic category of the English-speaking minority—which was itself overshadowed by the primary focus on the marginalization of the French-speaking working class during Quebec’s Quiet Revolution. Nobody mentioned Oscar Peterson or Rufus Rockhead; no jazz age, nor Union United Church—all staples in the current representation of the neighbourhood. Instead, articles on the history of the area highlighted early French settlement and industrial development, perhaps mentioning French-Canadian strongman Louis Cyr.[82] Little Burgundy was almost universally presented as a poor francophone slum. For a time, language and class (often understood together) trumped everything else. The absence of race in the planning documents and in the public discourse of the time is itself a form of racism.

With Expo 67 coming, the deteriorating state of Montreal’s “popular” neighbourhoods was a source of shame.[83] Forged in the fires of the Industrial Revolution, these areas were renovated for new post-industrial possibilities in the 1960s and 1970s. Under Mayor Drapeau, the city embarked on rapid modernization with the building of highways, a Metro system, slum clearances, and an expanded city centre. Entire neighbourhoods disappeared. Little Burgundy was one of those affected the most, when much of it was razed to make way for the Ville-Marie autoroute and then a massive public housing estate. Highway construction began in 1967, resulting in the demolition of the strip between Saint-Antoine and the escarpment. Shirley Gyles recalled that “a lot of black families lived on that side of the street.” For her part, Nancy Oliver Mackenzie, a member of Union United Church, originally from Nova Scotia, drew a parallel between the highway expropriation in Montreal and what infamously happened to one black community in her home province: “They put the highway through and it’s kind of like Africville, Nova Scotia. Africville was a black area down by the water. The city just came one day and bulldozed, and people were all relocated to social housing on the Halifax side. People lost their church, their community. It was a bit like that when the highway came through. They took down a lot of places.”

Figure 12

Looking east along rue Saint-Antoine from the roof of the Canadian Buttons Limited factory, 31 May 1967. Richmond Square is located midway up the street. Everything north of the street, or to the left, was demolished as part of highway construction. Everything to the south, or the right (except the Tyndale Centre in the foreground), was demolished as part of the urban renewal project.

St. Anthony’s Church was razed, as was the Black Bottom Café, an after-hours jazz club. According to its owner, Charles Burke, the Black Bottom was named after a dance popular in the 1930s. He wanted to make a “statement about the music and about blackness.” Charles served coffee, chicken wings, and “soul food.” But the club was open only from 10 p.m. until 10 a.m. on Thursdays, Fridays, and Saturdays, so he could work on the trains as a porter the rest of the week. As he explains, “I had accumulated enough seniority on the railroad where I could have an organized run. I think I was running to Chicoutimi or some place. So my railroad work always gave me three days off. I was always home to work at the club.” The Black Bottom provided a meeting point for musicians who came there to jam after-hours.[84] This ended with expropriation, as the club stood in the way of the highway. He used the compensation to reopen in Old Montreal, but it was never the same: it had lost its mostly black clientele and with them, its “funk.”

Overall, the highway expropriation had a disproportionate impact on black Montrealers. Richard Lord told us that the highway expropriations resulted in the demolition of some of the nicest housing in the area, thus displacing “people that served their country well, who had deep roots in the area, broke up the community…. And you drove the people that was at one time named the servant class, because most of them were chauffeurs, maids, junior staff of companies, and you wiped them out so you left the low-income families in the area.” [85] Ethel Bruneau agreed: “I think when they put in the highway a lot of things closed, a lot of buildings got closed, a lot of facilities, a lot of people moved away.”[86] It was no coincidence, as the radical restructuring of North American cities have disproportionately affected racialized minorities and poor whites.[87] Just as urban decline has deep historical roots and was “ripe with injustices,” so, too, urban renewal.[88] As Ted Rutland argues in his important new study on urban planning in Halifax, Nova Scotia, “Displacing blackness, physically and symbolically, is the unending work of modern planning.”[89] These may be harsh words, but ones with the force of history behind them.

At the same time, the activist state also initiated the largescale urban renewal of Little Burgundy, including the recovery and redevelopment of former railway lands running through the heart of the neighbourhood. The urban renewal was undertaken in stages, starting with the Ilôts Saint-Martin in the northeast corner of the neighbourhood. In December 1966, the 160 families living in this eight-acre area received a notice of expropriation, including at least 19 black families. The NCC’s Stanley Clyke reported that these families found it doubly difficult to find new accommodation, in the face of racism.[90] Demolition began in November 1967, leaving only twenty-eight buildings standing. A button factory, which reportedly employed 400, was also demolished, exacerbating local job losses. The rest of the neighbourhood fell to the wrecker’s ball in stages. In all, the city built 914 HLM (habitations à loyer modique) units between 1969 and 1972, reaching 1,441 units by 1984.[91] Meanwhile, the area’s population dropped from 14,710 in 1966 to just 7,000 in 1973.[92]

This rapid sequence of events reflected the tenor of the times, a period when the United States was waging a high-profile “war on poverty” (U.S. President Lyndon B. Johnson declared war on poverty during his State of the Union Address in 1964), and urban renewal was tied to notions of modernization and progress.[93] “Across North America, we are restructuring towns, we are revalorizing them. Montreal was swept up in a current like the others,” declared Metro Matin in April 1965.[94] It was only natural then that Montreal launched “a war … against the most dilapidated neighbourhoods in the metropolis.”[95] City administrators adopted the “block-by-block” principal developed in New York City, where urban renewal was undertaken in stages in an effort to try to prevent people from being expelled from their districts entirely.[96] Lucien Saulnier, president of the Executive Committee of Montreal, also visited New Haven, Connecticut, to see how that city was approaching public housing redevelopment.[97] At the time, many commentators viewed the city’s approach to urban renovation in Little Burgundy as a substantial improvement on the way that the city had expropriated lands a few years earlier in Goose Village, across the canal from Little Burgundy.[98] The staged approach to urban renovation, however, prolonged the disruption over a decade.

At first the local media championed the renewal project, only criticizing its glacial progress. The first discordant voices came several hundred newspaper articles later, with the formation of the Réveil des Citoyens de Ste-Cunégonde, which quickly changed its name to la Petite Bourgogne, as the neighbourhood’s new identity hardened. In October 1966, the group declared, “Old working-class sectors are treated like ‘rags’ that the technocrats apparently are allowed to carve into whatever way they like. ‘But they are also home, precious to some people who for the most part cannot find shelter elsewhere that is within their means.’”[99] The defeat of all three Drapeau-Saulnier candidates in St. Ann district, which includes Little Burgundy, during the October 1966 municipal election, signalled that residents were not willing to be ignored any longer.[100]

While careful not to oppose the entire project, Little Burgundy residents demanded more explanation, more compensation, more time, temporary housing, design changes, and ultimately, better rent scales in the newly built public housing: citizen meetings multiplied.[101] In time, popular mobilization, here and in other Montreal neighbourhoods, generated a new consensus about the rights and duties of citizens. This constituted a significant shift in public policy. The citizens committee model itself was another innovation.

In the first area to be renovated, the residents of the Ilôts Saint-Martin were on the front lines of resistance. One hundred and fifty people attended a public assembly at l’Église Saint-Joseph in November 1966, where city officials outlined their proposal. According to Jeanne Leblanc, a leading white local activist, “It was nice, but we no longer had our neighbourhood.” Two groups of residents organized in the Ilôts Saint-Martin, one anglophone and the other francophone. To some degree, the linguistic line was also a racial one. The notice of eviction arrived on 7 June 1967, ordering residents to leave by 1 September. A day later, one hundred people met at Tyndale House—a local community centre—where they decided to protest at City Hall. They wanted more compensation, a delayed moving date, and temporary housing. In response, Lucien Saulnier attended a public meeting held at the NCC on 22 June, where he reassured residents that everything would be fine. Leblanc recalled this moment differently: “C’était la première fois que je voyais ‘LE POUVOIR’ de près, j’étais très émue.”[102] To make matters worse, all of this was happening during Expo 67, a period that saw sharply increased rents and lower vacancy rates. In response to the political pressure, the city doubled the indemnity to $200, increased its reimbursement of eligible expenses to $1000, and extended the moving deadline. In July, as the rest of Canada was celebrating the country’s centennial, a “souper d’au-revoir” was organized for residents. By October 1967 the Ilôts Saint-Martin were all but deserted.

Figure 13

The Stages of the Little Burgundy Urban Renewal Project, Ville de Montréal, Service d’Urbanisme. La Petite Bourgogne: Rapport general, September 1966.

Figure 14

Exterior of building to be expropriated in Little Burgundy, 10–11 May 1967.

Figure 15

Exterior of buildings to be expropriated in Little Burgundy, 10–11 May 1967.

If state power was on display at public meetings, it became almost visceral when city assessors entered people’s homes to take expropriation photographs. More than one thousand documentary images were taken in Little Burgundy between January and August 1967. In each one, a well-dressed city official holds up an identification card to locate the pictured exterior or interior. There were hundreds of photos of bathrooms, kitchens, living rooms, hallways, basements, and other spaces. These were modest homes and we glimpse real poverty. There were also photos of soon-to-be-demolished restaurants, taverns, stores, beauty salons, churches, offices, and factories. Little Burgundy was not simply a residential area, but a place of work, commerce, and sociability.

From time to time, Little Burgundy residents were caught in the photographs. Children usually appeared in exterior shots, curiously facing the camera; older residents found themselves squeezed to the edges of the photographic frame as they tried to stay out of the way in confined interior spaces. A number of workplace photos also recorded men and women at work. Having sifted through all of these photographs, I found only a handful of visual evidence of the presence of black Montrealers. One man (pictured figure 16) defiantly stayed at his kitchen table as the assessors photographed around him. Another man resolutely continued sitting on the chesterfield at the centre of the photograph, facing the camera, while the photograph was being taken. But most of the residents pictured during expropriation were white, many of whom were shown at work. The whiteness of the workforce at the Canadian Buttons factory on Saint-Antoine, for example, for which we have several dozen photographs, confirmed something that I had heard in oral history interviews about the hiring policies of this local employer. The expropriation photographs (figure 18, especially) thus record racial exclusion as well as the black presence.

Figures 16

A black resident of Little Burgundy finds himself in the frame of the expropriation photographs taken inside his home, 5 May 1967.

Figure 17

Canadian Buttons Limited expropriation photograph, rue Sainte-Antoine, 30 May 1967.

Figure 18

Canadian Buttons Limited expropriation photograph, rue Sainte-Antoine, 30 May 1967.

The nascent resistance to expropriation was recorded in Maurice Bulbulian’s 1971 NFB documentary film, La P’tite Bourgogne. It begins with the “deportation” of 1967 and ends with the beginning of reconstruction in 1968. Bulbulian celebrates the efforts of community members to be heard. According to La Presse, “The struggle that they have undertaken to be repatriated in their neighbourhood, for human conditions, is now legendary.”[103] La P’tite Bourgogne was launched in the neighbourhood and screened a remarkable fifty-two times to community groups in the first week. The film was part of an emerging critique of these projects. For many North Americans, the publication of The Urban Villagers, by Herbert J. Gans, which told the story of the erasure of a vibrant West Boston neighbourhood, and Jane Jacobs’s iconic The Death and Life of Great American Cities, challenged many of the assumptions behind urban renewal.[104] In response, city planners increasingly sought to temper their approach.

Faced with a rising tide of community resistance to its modernizing projects and changing public perceptions, the activist state invited increased public consultation. La Service d’Animation Sociale du Conseil des Oeuvres (later the Conseil de Développement social de Montréal), for example, sent social animators to Little Burgundy in 1966 to prepare citizens for the consultative processes associated with urban renewal. The Company of Young Canadians then stationed twenty-four young social animators in the neighbourhood between 1967 and 1971, even opening an office there. Social animation was premised on a logical progression from research to collective reflection and then action. These efforts led to the formation of the Réveil des Citoyens de la Petite Bourgogne and contributed to the emergence of a new generation of (white) francophone community organizations in the area. According to Suzanne Veit, who published a 1971 report on some of these efforts, “It was this time period that saw the birth of social animation in Quebec.”[105] Eventually, however, these often-privileged young people rubbed many neighbourhood activists the wrong way. Some community groups later spoke of being “invaded by animators” at the beginning of the urban renewal process. By 1971 the two neighbourhood groups that initially worked with the Company of Canadians would no longer do so. Mistrust had taken hold. After five years of meetings and struggle, and too little to show for it, citizen activists were exhausted and the initial enthusiasm “evaporated.”[106]

Today Little Burgundy has the highest proportion (56.3 per cent) of subsidized housing in Montreal and the largest concentration of public housing in Quebec. Much of the new public housing stock was restricted to those on social assistance, or with limited incomes. Many better-off residents were thus virtually ineligible to move back. In 1961 there were 4,129 housing units in Little Burgundy. In 1976, the number had been reduced to 1,940.[107] A 1989 report by the Comité pour le Relance de l’économie et de l’emploi du Sud-Ouest de Montréal provided damning proof that the urban renewal of Little Burgundy worsened class and racial segregation, while doing little to resolve social problems: “In effect, in Little Burgundy, we see since 1971 the disastrous social effects of urban renovation: from 1961 to 1971. The proportion of welfare recipients went from 10% to 40%. The massive demolition of housing forced out of the neighbourhood the most well-off who had the financial means to find lodging in other parts of the city. This group never returned to the neighbourhood.”[108] By the 1980s, 43.8 per cent of the residents of Little Burgundy lived below the poverty line (a rate surpassed only by Pointe-Saint-Charles at the time).[109] In 1986 the French-language school board ranked Little Burgundy (along with Saint-Henri) as the most marginalized area on the island of Montreal.[110]

Not surprisingly, the rapid transformation of Little Burgundy undermined the thick web of community institutions that served Montreal’s black community. One by one, the area’s English elementary schools closed their doors. The most devastating blow was the closure of Royal Arthur in 1981. Henceforth, English-speakers had to leave the neighbourhood once they reached school age. “I don’t see any schools left. They’re closing them all,” noted Mr. Pion in the early 1980s.[111] Many feared that school closures were sounding the death knell for the old community. For Rosemary Woods, “Now English-speaking kids have to be bused out of the neighbourhood. Who wants to move down here when they have to have their children bused all the way two or three miles from here?”[112] Likewise, for Yvonne McGrath, the school closure “hurt the Negro Community Centre because they used to prepare all the meals for the children from the school and also, they had all kinds of activities there for the children, and a lot of the people now may turn around and move because of the school’s closing to be closer.”[113] The closing of Royal Arthur took the “heart” out of the community, agreed Gordon Butt. A black neighbourhood organizer, Butt recalled, “St. Antoine was one of the richest looking community streets you ever want to see…. The old stone homes that were there were something. You have to see it to understand, the kind of destruction that took place in this community. And where did all those people go?… They took away the gut of the community. Everything was stripped. This community was stripped raw.”[114]

The annual reports of the NCC record the organization’s decline in no uncertain terms. As early as 1962, its leadership was “keeping a vigilant eye on possible impending physical and structural changes in the neighbourhood, for example, the approaches to the Champlain Bridge, the proximity of our area to the World Fair [Expo 67] site and the gradual westward trend in the building of highrise apartment and office complexes.”[115] The significance of the announced highway expropriations and urban renewal scheme was not lost on Stanley Clyke, who wondered aloud in October 1965 if the NCC should consider relocating to another part of the city.[116] It stayed put, but the NCC’s membership fell from 973 in 1959 to 515 in 1967. By the mid-1970s, membership hovered in the low 300s.

Falling membership was a matter of considerable concern. In 1966, for example, the president of the NCC reported, “Families have continued to move away from the neighborhood; new ones have moved in. Expropriations or the threat of expropriation … has left a large number of homes vacant along the north side of Saint Antoine Street and in that area to the south—now referred to as La Petite Bourgogne…. Families which have moved are now located in widespread areas of the city.”[117] At the same time, new black neighbourhoods were taking shape in other parts of the city, such as in the Van Horne area of Cote-de-Neige and Walkley in Notre-Dame-de-Grace. Accordingly, even on the eve of renewal, the NCC felt that the old depiction of black Montreal as “A Community Within” (the title of a 1955 CBC documentary film on the neighbourhood) “no longer holds true from a geographic point of view, but rather it might be said that integration of the Negro Community is rapidly taking place—at least in a physical sense.” The NCC had to change with the times, or die.

To survive, the NCC radically decentralized its operations in the 1980s to serve black communities in other parts of the city. For a time, this strategy worked and its membership recovered. But relatively few NCC members remained in Little Burgundy. In 1982–3, for example, only 256 of the NCC’s 861 members still lived in the old neighbourhood.[118] Eventually black organizations in other parts of the city chaffed at being under the direction of the NCC. It was all too much, and the NCC closed for good in 1992. Little Burgundy is now home to new immigrant communities, and a new generation of mainly francophone community organizations has appeared.

The wounds left by these sweeping changes were still fresh in the oral history interviews conducted in the early 1980s. At one point in the interview with her husband, Mrs. Pion jumped in to say that it “used to make me mad that the City would come in and say, ‘Eh! Get out of your homes.’” They put them into a temporary home on Notre Dame that was described as a “real fire trap.” The city-owned housing may have offered more room than before, but the “kids don’t seem to have places to go. That’s why they’re getting in so much trouble. They don’t have anywhere to go. Nothing to do, stuck on the corner and gang up.” E. Radcliffe, who had moved to Little Burgundy in 1959 from Nova Scotia, shared similar concerns. Before the renovations, the “old” houses were “big” but had cockroaches, bedbugs, and rats. Today, “there’s no more rats” and things were “much cleaner” in the city-owned housing. However, there were problems: “The kids ransack the place and they always damage things…. There’s kids breaking into houses and robbing going on.… There’s a lot of robbery.”[119] Mrs. Sherwood added, “All these people around here now are all new.”[120] It was disorienting.

The social consequences of this transformation were long term. Martine Thériault, a community organizer at the local CLSC (neighbourhood health clinic), interviewed in 2015, blames the social crisis, at least in part, on the social and cultural scars left by the expropriations.[121] According to her, “The neighbourhood of Little Burgundy is a quartier that is completely destroyed, and then rebuilt, but rebuilt in stages.” The renovations demolished not only buildings but also neighbourhood connections. This had devastating consequences for the black community: “The people of the black community, what they have seen, experienced in these transformations of the neighbourhood. They have many regrets about having seen their neighbours forced to leave. There was a lot of sadness I think for them, throughout this.”

Conclusion

By framing this article in terms of employment mobility, I have been able to draw together aspects of the black experience that are often considered apart. Race, residence, and work were profoundly intertwined in the history of Montreal, much as they were in other North American cities. A multiracial neighbourhood took root near the CNR and CPR stations, as hundreds of black men found employment as sleeping car porters, redcaps, and dining car employees. In many ways, railway porters were the labour aristocracy within black communities for the first half of the twentieth century—founding important local and national institutions that have endured. This was certainly the case in Montreal, where Union United Church and UNIA’s Liberty Hall continue to serve a city-wide English-speaking black community from Little Burgundy. But many other community institutions are no more, having fallen victim to suburbanization, economic crisis, and modern planning. Much like other historically black and multiracial neighbourhoods, Little Burgundy was targeted in the 1960s for highway expropriation and urban renewal.[122] The shift from trains to cars or trucks delivered a one-two punch: first, hundreds of black men lost their jobs on the railway, then they lost their homes to the highway. Much of the community was dispersed as a result, leaving behind a poorer and more transient population living in public housing. New immigrant communities have since settled in the area, particularly from South Asia, and new histories are being written, but there is still a residual anglophone black community living in Little Burgundy.