Article body

FIGURE 1

Apparition Room, installation view with projectors, lighting, audio, props, and furnishings.

While many artists use digital technology, how many really confront the question of what it means to think, see, and filter affect through the digital? How many thematize this, or reflect deeply on how we experience, and are altered by, the digitization of our existence?

Claire Bishop, “Digital Divide: Contemporary Art and New Media.”[1]

Apparition Room took the form of a four-part archival exhibition that celebrated the 50th anniversary of Western Front, one of the first artist-run centres (ARCs) in Vancouver, BC, and in Canada.[2] It was curated by longtime Vancouver- and Berlin-based curator Lee Plested and featured colourful lighting, props, and furnishings provided by Berlin- and Tokyo-based artist and scenographer Nile Koetting. Open to the public and by appointment, it comprised four consecutively curated exhibitions, each identified by a distinct title and theme: Under the Skin (on identity and the fragility of being), Abstract Means of Production (on the labour of making), and Narrating Susceptibility (on the act of storytelling). This atmospheric and transportive exhibition straddled both past and future through the activation and juxtaposition of traditional crafts – specifically, ceramics; rituals, in the form of a tea ceremony; and archives – with new media and digital technologies. For each exhibition, Plested carefully selected clips of digitized performance, video, and sound artworks by 50 different artists from Western Front’s vast audiovisual archives, which spans over 50 years of production. These clips were projected on different walls in the gallery space and accompanied by sound bites both from the original artworks and from audio works in the archives. Each of these elements played sporadically, leaving the viewer wondering where to look and what they would be listening to next. Waiting in anticipation, visitors were privy to a choreographed tea ceremony.[3] A host, wearing Issey Miyake colour-blocked pleats and a wireless microphone headset, methodically brewed and carefully poured the tea – a mixture prepared from locally foraged plants by Bryan Mulvihill (aka Trolley Bus) and T’uy’t’tanat-Cease Wyss – which was served to visitors in ceramic bowls made by local potters.

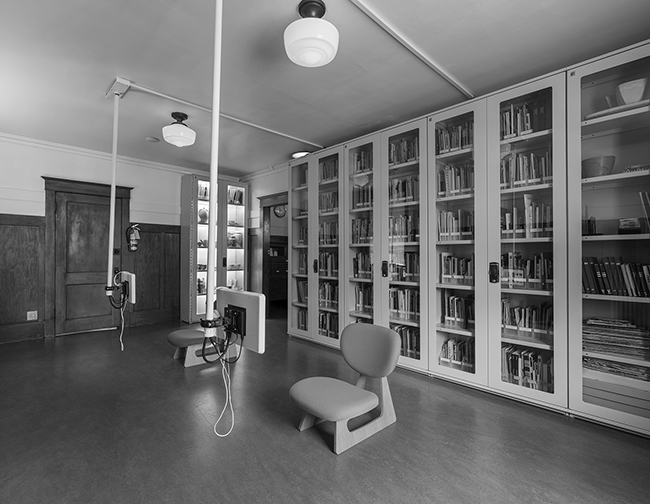

The four exhibitions took place in the main gallery, while different works played in their entireties in the ground floor reception area including Corinne Sworn’s Rag Papers, Jane Ellison and Eric Metcalfe’s Oh Yes, Oh No, and Abbas Akhavan’s Plant, to name a few. Expanding the exhibitions beyond the gallery walls granted visitors an opportunity to also consider the building itself in relation to the archives. While the exhibition text is silent on its history, the building dates back to 1922, when it was constructed as a hall for the Knights of Pythias, a fraternal organization and secret society. Having worked in the archives at Western Front from 2018 to 2019, I know that the Pythian Knights, as well as the many artists, musicians, poets, and dancers who have moved through these rooms and hallways, have all left traces in the archives. Upstairs in the library, in close proximity to the Grand Luxe Hall and Western Front’s archival holdings, sat two chairs facing iPads suspended from the ceiling: an open invitation for guests to sit and watch the full-length exhibited works and browse the digital archives.[4] While the library viewing room was only mentioned as a small note in the exhibition brochure, its inclusion as part of Apparition Room is evocative, bringing attention to the digital archives and the entangled roles of the curator, artist, and archivist today.

FIGURE 2

Apparition Room, installation view of Abbas Akhavan’s Plant (2013) in the ground floor reception.

FIGURE 3

Apparition Room, installation view of Western Front’s library and digital database viewing room.

As this was an archival exhibit celebrating the last 50 years of activities at Western Front, I expected to see a comprehensive display of archival records, but instead, the archives were used primarily as artistic materials to be sampled: the curator sliced, spliced, and collaged excerpts from different works and formats to create whole new works – more specifically, an assemblage that could “[bring] to life digitized artworks.”[5] While the archival turn and archival impulse in contemporary art and beyond are not new,[6] the recent creation of Western Front’s digital archival database and its ongoing digitization efforts are cited as primary catalysts for this exhibition.[7] It goes without saying that the digital was a strong underlying conceptual framework in Apparition Room – an unexpected centrepiece for a brick-and-mortar archival exhibition. Despite this futuristic curatorial approach, Plested’s perception of a digitized artwork (a digital record) falls into a trap common to perceptions of the act of digitization – that is, of thinking that digitization renders the work lifeless and in need of reviving post digitization. This assumption represents an underlying anxiety or fear about loss: loss of authenticity through transfer to a new format, loss of meaning through abstraction into digital coding, loss of information via the obsolescence of media technology,[8] and, ultimately, loss of access to memory. Plested’s choice to create new works parsed from fragments of digitized archival materials feels like an attempt to represent and capture a prevailing collective anxiety around digital loss; it evokes the way we fear our own memories blending, fracturing, and fading with the passage of time. By presenting the materials as a bricolage of different records and formats, Plested recalls familiar contemporary acts of “skimming” and “browsing” – assembling the archives into digestible components to ward off the impending feeling of information overload in the archives.[9] But similarly, I wonder how this history – represented as fractured and elusive, with minimal context – somehow lends itself to evading the past and what the consequences of this evasion might be. Whose stories are included, and whose stories are left out of this history?

FIGURE 4

Apparition Room, exhibition tour with Sierra Megas performing a tea ceremony.

To a formally trained archivist, the practice of removing an archival record from its original context of creation – in the way a curator, artist, or researcher does – challenges the established archival principles of respect des fonds, provenance, and original order. It does this by disrupting the archival bond that gives meaning to records by keeping them together, documenting the relationships between records as they relate to specific transactions of the past, present, and future. Further, the act of using archives to make new works raises questions about the legal and ethical rights of a curator or artist to manipulate and (re-)use the intellectual property (artwork) of another artist, as well questions about compensation for this use.[10] Coincidentally, when I raised these concerns with an artist friend, they responded that the creation of this new work was their favourite part about the exhibition as it freed the archives from their didactic and evidentiary function and allowed them to be reconsidered in new ways. This response left me wondering about the seeming conflicting between the role of the archivist, who preserves the record, and that of the curator or artist, who – in this contemporary moment – selects, recontextualizes, and creates new works for display. How do these roles collaborate or conflict with each other in this contemporary digital age?

In her foundational 2012 text “Digital Divide: Contemporary Art and New Media,” art historian Claire Bishop reflects on the ubiquitous nature of the digital technologies and processes that undergird contemporary art production and dissemination, which she argues has largely gone critically underacknowledged in the art world. Over 10 years later, Apparition Room encapsulates the art world’s ongoing and palpable nostalgia for legacy technologies (analog and craft) and continued fascination with social practices (in this case, hosting).[11] What has shifted, however, is Bishop’s observed ambivalence toward the digital: the digital is no longer speculative but inevitable and urgent, posing dire consequences for society and cultural memory unless action is taken by archivists and digital records creators alike to support and execute the creation, management, and preservation of digital records. The collision between digital and analog worlds in Apparition Room is a testament to our contemporary anachronistic reality and our exasperated efforts to grapple with the digital. Bishop’s question is now, simply, a statement of fact: We experience and are altered by our digital existence – every day, in nearly every way.

Even though Apparition Room was an on-site exhibition, it prompted more questions about the digital future of Western Front than about the physical archives of its past. In many ways, this falls in line with the legacy of Western Front as an institution that is well known for its audiovisual archives and as an early site of experimentation for new media technology and video art. From that perspective, it makes sense that the present focus would be on digital archives and digital production – the future of media. On the one hand, Apparition Room was an unexpected and experimental approach to an archival exhibition celebrating the 50th anniversary of a prolific artist-run centre. On the other hand, this approach thwarted an opportunity to engage more openly with the people who were directly involved in the founding, production, and preservation of Western Front and thus, missed an opportunity to be critical and self-reflexive about its past. As such, an unresolved tension between the past and the future sits at the core of the exhibition. How will this shape the next 50 years of Western Front? We will just have to wait and see what the 100th anniversary brings.

Appendices

Notes

-

[1]

Claire Bishop, “Digital Divide: Contemporary Art and New Media,” Artforum International 51, no. 1 (2012): 434–42, 436.

-

[2]

Artist-run centres (ARCs) use a distinct non-profit gallery and governance model that emerged in the late 1960s and early 1970s across Canada. Governed by elected boards of directors, ARCs were created to support new and innovative practices in the arts and provide essential services to community members. ARCs are integral to the creation and dissemination of art and discourse and contribute to the development of cultural work and artistic production across Canada by offering community-engaged exhibitions, programs, and activities. Some of the earliest ARCs that are still in operation maintain libraries and archival holdings documenting the activities of ARCs, artists, and independent collectives over the last 70 years. See Artist-Run Centre and Collectives Conference (ARCA) and Canadian Arts Coalition, “Artist-Run Centres: Community Contribution Situation” (meeting handout, Arts 308 project, Canadian Arts Coalition, n.p., 2013), 2–4, https://arcpost.ca/file_download/44/.

-

[3]

Visitors who registered for a tour of the exhibition took part in a choreographed tea ceremony.

-

[4]

Western Front recently launched a customized and open-source CollectiveAccess archival database, built by Whirl-i-gig.

-

[5]

Lee Plested, Apparition Room (Vancouver, BC: Western Front, 2023), 1, https://westernfront.ca/events/apparition-room.

-

[6]

Art critic and historian Hal Foster describes the archival impulse as an art form that undertakes “an idiosyncratic probing into particular figures, objects, and events in modern art, philosophy, and history.” Similarly, archivist Kathy Carbone uses the term the archival turn to describe a particular fascination with the archive that emerged in the 1990s, specifically in the humanities and social sciences. The preoccupation with the archive during this time brought it into broader fields of study and theory as a “symbol for expressions of power, what is remembered or forgotten in society, and what is knowable and who has the power to make knowledge.” Hal Foster, “An Archival Impulse,” October 110 (2004): 3–22, 3, https://www.jstor.org/stable/3397555; Kathy Carbone, “Archival Art: Memory Practices, Interventions, and Productions,” Curator: The Museum Journal 63, no. 2 (2020): 257–63, 258, https://doi.org/10.1111/cura.12358.

-

[7]

Plested, Apparition Room, 3.

-

[8]

Archivist Samantha R. Winn points to another form of anxiety around loss, felt specifically in the age of the Anthropocene due to the irrevocable threat of climate crisis. Winn shares the larger existential anxiety felt by memory workers: “If there will be no one to remember what was, then what will have been the purpose of memory work?” Samantha R. Winn, “Dying Well in the Anthropocene: On the End of Archivists,” Journal of Critical Library and Information Studies 3, no. 1 (2020): 2–20, 2, https://doi.org/10.24242/jclis.v3i1.107.

-

[9]

Bishop, “Digital Divide,” 440.

-

[10]

Audiovisual and media art archives often face issues about consent with regard to newly digitized records due to outdated contractual agreements that predate the birth of the Internet. Today, archival best practices incorporate ethical approaches, and archivists are trained to ask for consent from creators in order to maintain good relationships with people and communities in addition to documentation.

-

[11]

Bishop observes the rising interest in social practices as a manifestation of the analog and references art critic and curator Nicolas Bourriaud’s early texts on relational aesthetics as the “artist’s desire for face-to-face relations against the disembodiment of the Internet.” Bishop, “Digital Divide,” 437.

List of figures

FIGURE 1

FIGURE 2

FIGURE 3

FIGURE 4