Abstracts

Abstract

The objective of this study is to introduce, develop, and validate a scenario-based method to study the influence of context in international business decision-making. Scenario-based methods use real-life situations to collect data or measure context-sensitive constructs. This study includes the development of a scenario and five behavioral answers using a five-step process and rigorous data collection. Based on multiple interviews and a final sample of decision-makers from 149 French small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), the measurement tool’s internal and external validity meets the criteria of scale development. The tool enables the study of internationalization decision-making from new perspectives—for instance, through more rigorous contextual research or exploration of sensitive topics such as cognitive factors, motives, and behaviors in international business research.

Keywords:

- Scenario method,

- contextual research,

- decision-making,

- measurement tool,

- small and medium-sized enterprise (SME)

Résumé

Cette recherche développe et valide une méthode basée sur des scénarios pour étudier l’influence du contexte dans la prise de décision des entreprises internationales. En utilisant des situations réelles, cette méthode peut collecter des données ou mesurer des concepts sensibles au contexte. La présente recherche élabore un scénario avec cinq réponses comportementales via un processus en cinq étapes et une collecte de données rigoureuse. Basée sur des entretiens et un échantillon de 149 décideurs de PME françaises, la validité de l’outil respecte les critères de développement d’une échelle. Cet outil permet d’étudier la prise de décision en matière d’internationalisation sous de nouvelles perspectives, incluant une contextualisation rigoureuse et l’exploration de facteurs cognitifs, motivations et comportements en commerce international.

Mots-clés :

- Méthode des scénarios,

- recherche contextuelle,

- prise de décision,

- outil de mesure,

- petites et moyennes entreprises

Resumen

El objetivo de este estudio es introducir, desarrollar y validar un método basado en escenarios para estudiar la influencia del contexto en la toma de decisiones empresariales internacionales. Los métodos basados en escenarios utilizan situaciones de la vida real para recopilar datos o medir constructos sensibles al contexto. Este estudio incluye el desarrollo de un escenario y cinco respuestas comportamentales mediante un proceso de cinco pasos y una rigurosa recogida de datos. A partir de múltiples entrevistas y una muestra final de responsables de la toma de decisiones de 149 pequeñas y medianas empresas (PYME) francesas, la validez interna y externa de la herramienta de medición cumple los criterios de elaboración de escalas. La herramienta permite estudiar la toma de decisiones en materia de internacionalización desde nuevas perspectivas, por ejemplo, mediante una investigación contextual más rigurosa o la exploración de temas delicados como los factores cognitivos, los motivos y los comportamientos en la investigación en negocios internacionales.

Palabras clave:

- Método basado en escenarios,

- investigación contextual,

- toma de decisiones,

- herramienta de medición,

- pequeña y mediana empresa

Article body

Studies on the internationalization of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) started in the 1970s (Meier & Meschi, 2010; Ribau et al., 2018). Since then, more international business (IB) research has focused on SME internationalization, and numerous calls have been made for papers on international entrepreneurship (e.g., Child et al., 2022). Recently, a new stream of research has begun to study the link between the cognitive traits of decision-makers and the various dimensions of business internationalization (Maitland & Sammartino, 2015; Vlačić et al., 2023). More specifically, analyzing the factors that influence decisions relating to internationalization is becoming a more prominent subject within IB research. Recent publications by IB researchers (De Cock et al., 2021 ; Niittymies, 2020; Schweizer & Vahlne, 2022; Zucchella, 2021) argue for more work on the individual level and on the determinants of decision-making in an internationalization context. The term “individual level” is employed in the context of IB to indicate a shift in focus from the macro or organizational level to the study of individual actors’ roles, decisions, and behaviors within businesses.

The emphasis of IB research on individual decision-making highlights the critical influence of context on these decisions. The context in IB research at the individual level refers to the specific conditions and circumstances influencing the decisions and behaviors of individuals engaged in internationalization initiatives (Teagarden et al., 2018). This encompasses aspects particular to the individual, such as prior experience, personality traits, and social networks, as well as specific to the socio-political environment of the host country, such as cultural nuances, political stability, and economic conditions (Nguyen & Tull, 2022).

Indeed, the factors that influence the decision-making process within IBs can be observed at four levels—national, company, the social environment of the individual and host country, and individual (Rugman et al., 2011)—which reinforces the variety of contexts that organizational behavior researchers encounter and requires particular attention to be paid to the methods they use for contextual analysis (Peterson et al., 2012). More specifically, as Glaum & Oesterle (2007) indicate, researchers are utilizing unique methods such as case studies, surveys, and in-depth interviews to understand better the complex dynamics involved in IB decision-making. However, the majority of IB research is mainly focused on empirical methods that directly capture internationalization behaviors with limited contextual authenticity (Nguyen & Tull, 2022). These methods also have shortcomings, especially in capturing the nuanced contextual details that influence internationalization decision-making.

Even if some researchers encourage more contextualization in research (Jafari-Sadeghi et al., 2020; Kahiya, 2020; Nguyen & Tull, 2022), most current techniques are unable to take contextual factors such as cultural and socio-political circumstances into account. For example, standardized and pre-defined questions are frequently used in survey methods, which limits the depth of responses and might ignore complex contextual details (Chang et al., 2020). Similarly, specific information relating to the unique circumstances that shape internationalization decisions may be lacking in secondary data (Chang et al., 2020). In addition, although substantial information can be gained from qualitative interviews, they are subject to the interpretive nature of responses (Child, 2009), and individual viewpoints or interpretations may influence the understanding of contextual environments. These empirical designs lead to several biases (e.g., defense mechanisms, a posteriori rationalization, desirability bias, and affective dimensions) that affect the credibility of the respondents (Birkinshaw et al., 2011; Richter et al., 2016; Sinkovics et al., 2008). In other words, understanding internationalization decisions and the role of context is challenging when using direct research techniques (Glaum & Oesterle, 2007).

Since the 1970s, Nosanchuk (1972) has developed a research technique containing a “controlled amount of information” (p. 107), which describes the context of decisions and enables quantitative and elaborate data analysis. This is known as the vignette or scenario method (Aguinis & Bradley, 2014). It entails giving participants realistic, well-crafted scenarios or vignettes that illustrate specific situations or challenges related to the study’s core subject (Nosanchuk, 1972). Afterward, participants are asked to respond to these scenarios or make decisions based on their proposal, providing researchers with valuable details about participants’ attitudes, thinking processes, and decision-making behaviors (Bradbury-Jones et al., 2014). This technique is an especially effective way of studying complex and context-dependent phenomena, as it enables researchers to examine how people engage with different contexts in a realistic yet controlled environment (Aguinis & Bradley, 2014).

This scenario-based approach has rarely been used in existing IB research despite its potential for studying decisions and improving the rigors of contextual research. Our objective is to address this by introducing, developing, and testing the scenario method in the current study. The contributions of this research are twofold. First, we contribute to enhancing the contextualization of IB research (Child et al., 2022; Kahiya, 2020) by introducing scenario-based methodological techniques that can open up interesting possibilities for future research. We provide a comprehensive, step-by-step guide for building and evaluating scenarios. This systematic guide aims to assist researchers as they methodically integrate and analyze contextual factors within the field of IB research. Our proposed scenario-based technique improves the rigor of IB research by asking respondents to reflect on the presented situation, minimizing social biases and promoting a more impartial understanding of participants’ perspectives. It helps respondents to immerse themselves in the context and enables researchers to get more credible responses. Furthermore, this technique will help to capture complex phenomena associated with IB research—such as internationalization behavior, intentions, and motivations—that can be challenging to assess using direct data collection techniques due to biases.

Second, we focus on individual-level decision-making, which offers numerous future research opportunities into international entrepreneurship. The role of leaders is crucial to strategic decision-making, particularly in the case of SMEs, and the cognitive traits of these leaders and how they influence internationalization decisions are increasingly gaining scholarly attention (De Cock et al., 2021 ; Schweizer & Vahlne, 2022; Thévenard-Puthod, 2021). By introducing scenario-based techniques in IB and international entrepreneurship, our study provides a way to capture individuals’ personal and behavioral factors that can influence decision-making.

This paper begins with a literature review that discusses some of the limitations of direct empirical techniques such as surveys, case studies, and interviews. Next, it emphasizes how the scenario method can contribute to understanding the contextual influence in internationalization decisions. Then, we explain how we built the scenario, collected the data, and designed the data analysis. In the following section, we present the study results. Finally, the article concludes with a discussion of our findings.

How the scenario method can improve IB research

In this section, we discuss the limitations of direct data collection techniques and then argue how the scenario method can help to improve the strength of IB research.

Limitations of direct techniques

Various tools are commonly employed in IB research, including case studies, direct surveys, interviews, and cognitive diagrams (Nguyen & Tull, 2022; Peterson et al., 2012). Table 1 provides an overview of the cognitive content that many of these techniques rely on. Despite the fact that these methods are based on a solid but debatable principle—the premise that the respondent can and wants to respond—it is essential to understand the inherent limitations of these conventional methodologies.

Social, status, and prestige biases may arise from traditional approaches that rely on the premise that respondents are willing to respond (Roxas & Lindsay, 2012). Individuals who perceive what is expected of them may tailor their responses to fit these expectations and offer socially acceptable answers rather than honest views (Roxas & Lindsay, 2012). Because respondents may value conformity over expressing their genuine opinions, this phenomenon undermines the validity and accuracy of the collected data, particularly when examining the context of IB research.

In addition, direct approaches have further limitations due to four inherent biases. First, because of defense mechanisms, not all information is verbalized. While interviews highlight some information, they fail to gather the rest “either because it is less important or because it is unknown” (Fiol & Huff, 1992). Social contextual factors also profoundly influence an individual’s propensity to be open to internationalization, but these factors are mainly unconscious (Johns, 2006).

Second, there can be a desirability bias when the topic of the study is particularly sensitive, as is the case with internationalization (Glaum & Oesterle, 2007). As a result, the respondent may attempt to hide reasons that could lower their status. For example, in the context of internationalization, respondents may want to present their organizations as competent and successful in the global market. They may, therefore, be hesitant to reveal any factors that could contradict this positive image and lower their status, such as a lack of resources, limited experience or poor performance. Furthermore, Cossette & Audet (1992) note that speech depends on the effect the subject wants to convey or the results they are aiming for.

Third, the declarative mode strengthens problems related to ex-post rationalization. The interviewee searches for a link between their actions and their values. When this is absent, they feel psychological discomfort, known as cognitive dissonance (Harmon-Jones & Mills, 2019). To avoid this, they need to self-justify the decision, especially if they feel personally responsible for it (Davis & Bobko, 1986).

Finally, the affective dimension can only be partially comprehended by direct techniques. By structuring their answers around logical explanations of cause and effect, respondents are less likely to show their true emotions because they are cautious about how they describe the situation. This is amplified when the effect is not well perceived—for example, when the respondent is very concerned with their status (Eidelman & Crandall, 2012).

These elements suggest that direct techniques have limitations when collecting honest responses, as responses may not represent the unconscious part of cognition. Despite the fact that there are techniques to reduce such biases, such as addressing endogeneity issues, reverse coding items, attention checks, and asking the same question twice (Stapleton, 2019), such procedures fail to deal with the fundamental problem that respondents could modify their answers in accordance with their preconceived ideas. In other words, individuals might think back on their past experiences and take into account their current beliefs, which could affect their responses.

Limitations in the context of internationalization decisions

At the SME level, internationalization decisions are mainly made by individuals (Munteanu et al., 2022). This can be explained by the fact that SMEs often have fewer hierarchical levels and a smaller organizational structure (Ashraf et al., 2023). The most senior managers in many SMEs are frequently the owner, founder, or senior executive, and they have a more hands-on approach and direct influence over strategic decisions (Ashraf et al., 2023; Munteanu et al., 2022). Thus, the biases inherent in direct data collection methods become particularly susceptible to the internationalization process in the case of SMEs.

The decision to internationalize an activity is strategic, complex, and largely irreversible—it involves high stakes. The issues involved are tough to pinpoint, and there is significant uncertainty regarding the desired or expected results (Doh et al., 2017; Sharma et al., 2020). Indeed, uncertainty (as underlined in the IB literature (Acedo & Florin, 2006)), combined with the irreversibility of decisions, leads decision-makers to develop defense mechanisms to protect themselves—most commonly to help maintain their reputation. Moreover, it can be challenging to make rational decisions in complex and poorly structured situations, and the subject may be tempted to explain their reasoning using ex-post rationalization. Additionally, the reasons that are common to all internationalization decisions in large firms can be added to those specific to SMEs, which are sensitive to direct methods. These characteristics make it impossible for direct techniques to identify the reasons, causes, and motivations behind decisions to internationalize.

In the case of SMEs, internationalization is the result of compromise. On the one hand, senior managers understand the advantages of internationalization (e.g., diversification, growth markets); on the other hand, they face significant barriers (Oliveira & Johanson, 2021), such as a lack of resources. According to Ricard et al. (2016), barriers may be more easily overcome in an SME whose senior managers share a positive outlook on internationalization. These managers tend to oversimplify situations, overlook indications of risks around internationalization, and underestimate the cultural and psychic distance between the home and target countries. Senior managers can also speed up the implementation of international activities by making quick and intuitive decisions. All those processes are unconscious, which is why direct techniques have not been adapted to capture internationalization decisions, especially in the case of SME senior managers.

The scenario method and studying context in IB

This study suggests using a projective method—the scenario method—as a tool to examine and contextualize the decisions made by an SME’s senior management relating to internationalization. This method is an effective empirical way of overcoming the limitations of direct techniques, particularly when studying the context and behaviors in IB.

Table 1

Tools used in international business research

The scenario method requires respondents to react to a text that describes a fictitious yet realistic situation (Wright et al., 2013). When respondents believe they are talking about the activities of another person, they are less likely to make an effort to conceal the elements that influence their behavior (helping to reduce prestige bias). For example, a senior manager will not have to worry about their or their company’s status if their name and the company’s name are not involved. This freedom of expression allows rich information to be gathered.

Scenarios, or vignettes, are “short descriptions(s) of a person or a social situation” (Alexander & Becker, 1978). They must contain “precise references to what are thought to be the most important factors in respondents’ decision-making” (Brauer et al., 2009). This suggests they must contain two critical elements: a realistic situation and the proposal of at least two alternatives to respondents. The term “realistic situations” implies real and relatable social scenarios or circumstances (Durance & Godet, 2010), while the situations in these scenarios have to be ones that respondents can relate to or imagine from their own lives (Aguinis & Bradley, 2014). This also highlights the significance of providing scenarios founded on real-world events rather than being unrealistic or overly abstract (Durance & Godet, 2010; Shahid et al., 2021).

Initially designed by social psychology researchers, the scenario method rapidly began to be used in other research domains, such as marketing (Bittar, 2018; Tonkin et al., 2019), health (Jackson et al., 2015), and business ethics (Mudrack & Mason, 2022; Shahid et al., 2021; Shahid et al. 2023). However, this method and other projective techniques have been used less frequently in strategic and IB research. This lack of attention is surprising because authors have identified that it offers valuable insight when studying complex situations in other research domains (Auspurg & Hinz, 2014; Ramirez et al., 2015). For example, in the field of marketing, researchers have utilized it to understand consumer behavior and forecast market trends (Tonkin et al., 2019). Likewise, research on ethical decision-making has shown the efficacy of the scenario method (Ferrell et al., 2019). Using this approach, researchers may provide professionals with realistic scenarios of ethical difficulties they would typically confront in the business world (Ferrell et al., 2019; Mudrack & Mason, 2022).

There are several possible reasons why scenario methods are not often used in strategic and IB research. One is that scholars have recently shown an intense interest in researching the context of internationalization decision-making at the individual level (Maitland & Sammartino, 2015; Vlačić et al., 2023). This particular line of research requires the investigation of sensitive and complex issues, which are better suited for study using scenario-based methodologies. This is because contemplating the scenario does not diminish the respondents’ identities and prestige (Bradbury-Jones et al., 2014; Durance & Godet, 2010). In addition, scholars have historically preferred to use more conventional research techniques in these areas (Peterson et al., 2012; Rugman et al., 2011), and because they were accustomed to these techniques, they may have been hesitant to switch to more contemporary, projective ones (Delios et al., 2023).

The scenario method provides all respondents with a standardized stimulus that does not depend on the investigator (because it is a written text). A monadic questionnaire is easy and fast for decision-makers to complete, which maximizes the number of people who can participate in the study. Moreover, describing a detailed and realistic situation increases the interest and implications for decision-makers (Wright et al., 2013). Complex and robust methods are required to understand further and assess cross-national differences in understanding internationalization decision-making. The scenario method enables multivariate analysis such as factorial analysis, regression, and path analysis and enables cross-country comparison (Aguinis & Bradley, 2014; Auspurg et al., 2015).

Method

This section describes the steps involved in building the scenario, the research design, and the data collection approach.

Building a scenario

The process of building a scenario begins with identifying interesting, relevant, and realistic subjects. By thoroughly reviewing the literature and preliminary interviews, we determined that barriers are an essential aspect that influences the decision-making process of SMEs around matters of internationalization (Rugman et al., 2011; Zucchella, 2021). As a result, we developed a scenario that depicted the execution of internationalization activities as particularly challenging and focused on recognizing and understanding the various barriers involved. We then scored the barriers on a participant-by-participant basis: those managers who were more willing to implement internationalization activities received a lower score than those who preferred to stay in their home country. This made it easy to understand who was more inclined to internationalize and who was not.

Synthesizing previously used scenario methods, Chonko et al. (1996) designed a five-step method for building scenarios that represent real situations. Later, Wright et al. (2013) identified that research that employs the scenario method uses either one scenario and multiple items or vice versa. The former may be used in situations where scores are required and when using data analysis such as path modeling; the latter is mainly used in experimental design. Since this research aims to present a method that enables complex decision-making and links individual traits to decisions, using one scenario and multiple items was more appropriate.

Based on their work on strategic decisions, Auspurg and Hinz (2014) suggested that realistic scenarios increase the ability of respondents to comprehend the context appropriately. A realistic scenario indicates a situation constructed to resemble real, believable, and authentic events (Chonko et al., 1996). The purpose of these situations is to improve the respondent’s ability to relate to and comprehend the context that is being provided. According to Auspurg et al. (2015), having a realistic scenario is a prerequisite to obtaining the validity of the result. We, therefore, ensured that our scenario was realistic and relatable for our respondents.

Building on recommendations from Chonko et al. (1996), we followed a five-step process to introduce, build, and validate our chosen scenario method. The first step was to identify a typical management situation. This situation had to reflect SME internationalization in line with this study’s objective. The first step was carried out through qualitative interviews with relevant respondents. The second step was to describe the context of the scenario briefly. This had to be realistic and believable, allowing respondents to see themselves experiencing the situation. The objective was to maximize variance among the responses to improve internal validity. The third step was to present the scenario for peer judgment. This was done through qualitative interviews, showing respondents a pre-written scenario and letting them react. The objectives were twofold: to assess the realism of the scenario and to write down behavioral answers (items on the Likert scale). The fourth step aimed to pre-test the tool, which comprised the scenario and behavioral responses. This pre-test was done through face validity and quantitative data analysis. The last step was to transmit the finalized questionnaire to the participants. Figure 1 summarizes the sequence that was followed to build the scenario.

Figure 1

The scenario method

Data collection

As Chonko et al. (1996) suggested, four independent samples were required to build the scenario. The first dataset consisted of qualitative interviews in order to gain an overview of the decisions SMEs made around internationalization and to collect realistic narrative situations (step one of the scenario method). Nineteen interviews were conducted with the chief executive officers (CEOs) of SMEs in France. The scenario was then developed based on their responses and further research (step two).

The second dataset required other CEOs to react to the narrative situation and build behavioral answers; these items had to reflect the CEOs’ reactions (step three). Fourteen interviews were therefore conducted with the CEOs of SMEs in France.

Next, the designed tool—composed of one scenario and five behavioral answers—was pre-tested on a panel of experts (step four). Six experts (four academics and two CEOs) participated during this phase.

The final questionnaire was then sent to the respondents, who were CEOs from different SMEs (step five). The final scenario and the five associated behavioral answers are presented in Table 2. The respondents were asked to read the scenario and then evaluate their level of agreement on a five-point Likert scale (ranging from strongly disagree = 1 to strongly agree = 5). Data for demographic details and some other relevant variables were also collected.

The final sample for the questionnaire mainly comprised data from the CEOs of SMEs drawn from the French Chamber of Commerce and the Industry and KOMPASS databases. The SMEs were selected randomly from the industry and service sectors. The CEOs were mainly contacted through an email campaign. The return rate was about 7%, which is lower than other studies on the internationalization of SMEs (Petrou et al., 2020). However, we identified and discussed three main explanations for the low response rate, which indicate that the result was satisfactory: (1) the scope of the study was very specific, (2) the target respondents had little time to devote to matters unrelated to their routine company operations, and (3) it was possible for respondents to get distracted by other work and forget the questionnaire. We also used several actions to encourage higher return rates (we proposed sending them the research results and reminders) (Helgeson et al., 2002).

Table 2

Scenario and behavioural answers

We received a final sample of 149 French SME decision-makers. The sample size is comparable to other studies on the internationalization of SMEs that looked at behavioral responses on an individual level (Petrou et al., 2020; Ruzzier et al., 2007). The sample characteristics are provided in Table 3. In summary, 83% of respondents were male, 66% were above the age of 40, and 72% had an educational level of graduate and above. Other key facts include that 41% of respondents owned their company, and 36% of the SMEs were over 10 years old.

Table 3

Descriptive statistics

Percentages are given according to the total answered.

The difference between 100 and the percentages is the ‘other answer’ category percentage.

Data analysis

The data analysis had two objectives: first, to assess the newly designed tool’s internal validity, and second, to assess its capability to evaluate the international performance of the SMEs (external validity).

Assessing the measurement tool’s internal validity

Internal validity was crucial for granting the measurement tool a higher level of confidence (Woodman, 2014). Behavioral answers are similar to classical measurement scales; therefore, we employed the classical means used in scale development for the internal validity assessment. We followed the steps Churchill (1979) suggested and integrated recommendations from Gerbing & Anderson (1988).

We also used face validity to refine the measurement tool. A group of experts, composed of academics and company CEOs, was asked to assess the relevance of the scenario and behavioral answers, the clarity of the writing, and the ability of the tool to distinguish between different groups of respondents.

Assessing the measurement tool’s external validity

The most common criticism of the scenario method is that it favors internal over external validity. We checked the external validity by evaluating the correlation between the output of the measurement tool and the actual international performance of the SMEs included in the sample (Diamantopoulos & Winklhofer, 2001). As suggested by Chetty et al. (2014), the degree of SME internationalization was reflected by the international sales made by the companies. To measure the international performance of the SMEs, we calculated the international sales ratio (the international sales put over the total sales) of the companies included in the final sample (Calof, 1993; Khavul et al., 2010). This served as an independent index to be evaluated by the measurement tool we developed in this study. The measurement tool was considered externally valid if the score correlated with the company’s international performance.

The aim of this study and tool development is not to predict other variables within this paper but rather to ensure external validity by correlating it with the benchmark variable, which in this study is international performance. However, the usefulness and predictive capabilities of the tools are discussed in later sections of the paper.

Results

We organized our results around the two main objectives of this research. The first was to propose an original and reliable method to study the impact of context on behavior and decision-making concerning internationalization. This involved assessing the measurement tool’s internal validity. The second was to evaluate the tool’s external validity. This involved assessing the statistical links between actual performance (represented by the international performance of the SMEs) and the scenario.

Internal validity

The measurement tool’s internal validity was assessed by ensuring that the scale was unidimensional and had internal consistency (Churchill, 1979; Gerbing & Anderson, 1988). Following the steps recommended by Churchill (1979), we assessed the factor loadings of the five behavioral responses developed after qualitative interviews and the pre-testing phase with experts. Factor loadings represent the relationship between latent factors and observed variables (indicators). These loadings show the intensity and direction of the association between each observable variable and the underlying component (Anderson & Gerbing, 1988). High factor loadings show a significant correlation between the variable and the factor, while low loadings indicate a weaker relationship (Fornell & Larcker, 1981).

Using the principal axis factor extraction method, Table 4 shows that the items have high factor loadings after six iterations, which indicates that they are good indicators of the latent variable being measured in the analysis.

Table 5 represents the total variance explained by the items. Results indicate that one factor was extracted quickly (six iterations only), and the variance explained by the first factor was above 60%, which is a common criterion used to measure scale dimensionality.

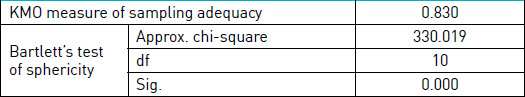

Table 6 shows the results obtained from the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure and Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity. KMO statistics evaluate the sample’s suitability for factor analysis. The range is 0 to 1, where higher values suggest a better fit for factor analysis (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). The results revealed that the KMO measure of sampling adequacy is 0.83, indicating the suitability of data for factor analysis. Furthermore, when Bartlett’s test yields a significant result (a significant p-value), it indicates that the data have enough correlation to move forward with factor analysis (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). The results of Bartlett’s test indicate a significant result, implying there is a significant correlation between the observed variables. In addition, the scale’s reliability met the standards benchmark, as Cronbach’s alpha was 0.860 (Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994).

Table 4

Factor matrixª

Extraction method: principal axis factoring.

Items correspond to behavioural answers given in Table 2.

ªOne factor extracted, six iterations required.

Table 5

Total variance explained

Table 6

KMO and Barlett’s test

External validity

External validity was inherent to the design of the scenario method. The first phase of the method was to perform qualitative interviews with respondents representing the final sample, and so the written scenarios were based on real narratives collected from CEOs. Data collection revealed that most CEOs passively pursued international opportunities, with the main stimuli coming from a client or potential partner looking to do business with a small company. We also noted that including a target country in the scenarios was a relevant detail. The scenario method requires at least one dimension for respondents to take a position. It appeared that a distant country (in terms of location, culture, and language) definitely forced respondents to do that.

The second phase of the method was to develop a realistic scenario. The third phase was to present the scenario to other respondents. This had two aims: to assess the respondents’ ability to identify themselves within the narrative and to collect their reactions in order to write behavioral answers. In terms of the first aim, we looked for evidence that showed the participants engaged with the scenario that was being presented. We found numerous elements that supported this, including the respondents using phrases such as “for me,” “if I was in this situation,” and “I personally would.”

Regarding the second aim, we wrote five behavioral answers based on the CEOs’ reactions (Table 2). The design of this phase reinforced the scenario method’s external validation because the CEOs evaluated the narratives and behavioral answers that emerged from those interviews.

Finally, the final tool’s predictive performance was assessed by measuring the link between the actual behavior of SMEs (measured by international performance) and behavior emerging from the scenario. As the measurement scale was unidimensional, the propensity to internationalize was calculated by adding up the item scores. Table 7 shows that the correlation between the propensity to internationalize and the actual behavior (international performance) was significant at the .001 level. Consequently, the measurement tool is considered to be externally valid.

Table 7

Correlation

The degree of freedom is equal to 122 as not all of the respondents answered the question on international sales.

Discussion

Our aim in this research was to introduce a scenario-based measurement tool for studying the internationalization of SMEs. Building on Chonko et al. (1996), we designed a scenario to assess the determinants of an SME’s internationalization. We validated the proposed five-step procedure to design a scenario for contextualizing IB research. We then developed behavioral answers that represented the internationalization stimuli faced by CEOs.

The results show that this tool is reliable and unidimensional. Furthermore, the significant correlation of the scenario scores with an objective measure of SME internationalization ensures the external validity of the tool. This result is particularly interesting as it helps to overcome one of the main criticisms of projective methods: favoring internal over external validation (Aguinis & Bradley, 2014).

Potential contributions to contextual studies

The scenario method could have various applications in the field of contextual studies, and studies focused on the influence of context on decision-making would particularly benefit from using this approach (Nguyen & Tull, 2022; Rugman et al., 2011).

Here, we have presented the first application of this method in the IB field, and the results are promising. While social desirability bias can often be a problem with direct approaches, as respondents may modify their answers to fit societal expectations (Roxas & Lindsay, 2012), the scenario method helps to reduce this bias. It puts respondents in real-life situations and gives them a familiar context to consider, but one where their answers are not directly related to their own experiences (Wright et al., 2013).

Furthermore, this method provides a controlled setting where researchers can isolate the influence of contextual elements on decision-making and alter specific variables (Ramirez et al., 2015). Respondents can immerse themselves in the events presented because of the controlled environment, which increases realism without requiring direct experience. Primarily, the scenario method works well when examining specific characteristics, like CEO attributes, in a context-based manner. By creating scenarios focusing on particular features, researchers can better understand how these traits interact with contextual circumstances to influence decision-making (Nguyen & Tull, 2022).

In summary, the scenario method appears to be an effective tool in mitigating biases and enabling an accurate investigation of decision-making processes within the intricate realm of IB.

Contextual research often uses qualitative interviews to collect data as well. Using common scenarios in international fields would help to set contextual elements and improve our knowledge of how decisions are made internationally. In addition, it would help to identify specific topics (e.g., speed of internationalization, country scope, country of origin) that have been only partially covered by the existing literature. By utilizing scenarios, scholars can rigorously examine these neglected aspects to develop a more thorough and nuanced understanding of decision-making in the context of business internationalization.

Variations on the scenario method, such as factorial surveys (Auspurg et al., 2015; Auspurg & Hinz, 2014), offer interesting alternative perspectives within IB literature. Factorial surveys are implemented in a different way to the scenario method. They often propose multiple scenarios (called vignettes) to respondents, including modalities of dependent variables. Only one Likert-style question follows each scenario, so the chosen scale is very important. Using factorial surveys requires a large number of scenarios, which may be challenging to establish in an international context. However, while the scenario method may seem more suited to international comparisons, factorial surveys could also be implemented to study specific topics, such as individual cultural influences on decisions.

Finally, using the proposed scenario-based measurement tool has implications beyond the IB field, such as the ability to study behavioral patterns in international entrepreneurship. It will help to introduce context to the degree that respondents can share their perspectives without those perspectives being influenced by bias. This will enable researchers to study sensitive topics such as internationalization motives and intentions.

Empirical and managerial relevance

Interest in IB research that focuses on the individual level has been growing in recent years. Therefore, the method presented in this article would benefit two major IB research streams.

First, the scenario method is especially relevant to management, particularly when exploring topics like psychic distance and global mindsets. Psychic distance has been widely studied in IB because it significantly affects a company’s performance (Evans & Mavondo, 2002). An individual’s sense of proximity to a given country will depend on both individual traits—including habits, social environment, location and type of studies, and personal and professional trips (Dow & Karunaratna, 2006)—and their overall sense of national belonging, including through their nationality (De Cock et al., 2021 ; Dow & Karunaratna, 2006; Kahiya, 2020).

The scenario method enables national, company, and individual levels to be studied simultaneously, which makes it promising for future research. Its primary benefit is that it gives managers a controlled and organized environment to interact with hypothetical but real IB scenarios. Managers can develop a deeper grasp of the possibilities and problems connected with internationalization by providing scenarios that need a global mindset or emulate different levels of psychic distance.

Second, the scenario method allows managers to evaluate their decision-making procedures in various international situations. This helps to uncover presumptions and biases that may be associated with cultural complexities and global perspectives. Numerous articles propose recommendations for companies that are willing to establish a global mindset among their managers (Arora et al., 2004; Cabrol & Nlemvo, 2013; Deng et al., 2021; Petricevic & Teece, 2019); however, very little research has focused on the impact of a global mindset on a company’s performance or behavior. Nummela et al. (2004) found that a global mindset significantly influences international performance. According to Arora et al. (2004), organizations should develop a global mindset to improve the success of their managers in working on a mission in an international context. The scenario method could help to deepen our understanding of the link between a global mindset and behavior by simultaneously measuring decisions and psychological traits.

Finally, managers can use the scenario method as a training tool to work together to negotiate challenging international settings. This interactive approach encourages experiential learning by allowing managers to experiment with various techniques, evaluate results, and modify their decision-making processes in a risk-free setting.

Limitations and future research avenues

Having highlighted the relevance of empirical and managerial research, we acknowledge that our study has two main limitations.

First is the existence of an instrumentation effect, which is a common characteristic of projective approaches such as the scenario method. Even with our best attempts to create scenarios that closely resemble real-life events, it is nevertheless possible that respondents may not completely immerse themselves in these situations. Our study included design remedies like peer reviews and qualitative interviews to lessen this limitation. However, a critical direction for future work entails investigating other scenarios and contexts to strengthen the scenario method’s generalizability outside of the parameters of our investigation.

Second, the study’s emphasis is on a particular national context. This decision may have restricted the broader significance of the findings to a more varied range of cultural and contextual settings, even while it allowed for an in-depth analysis of decision-making processes within that specific setting.

Furthermore, expanding the application of the scenario method to international situations is a viable direction for future research (Nguyen & Tull, 2022). By examining decision-making situations in many different countries, researchers can enhance our understanding of how decision-makers manage distinctive barriers in varied international contexts, in addition to bolstering the cross-cultural validity of the approach. It can also be used to study entrepreneurs’ cognition, motives, and behaviors (De Cock et al., 2021 ; Schweizer & Vahlne, 2022; Shahid et al., 2024).

Future studies should also expand the variety of scenarios offered to participants to reinforce the method’s robustness. Examining scenarios that differ in terms of complexity, cultural significance, and corporate circumstances can provide a more nuanced understanding of how people make decisions in global business settings (Rugman et al., 2011).

In addition, further research initiatives might include comparing different industries, organizational sizes, and geographical areas. This strategy would consider the scenario method’s usefulness for comparative research, providing insights into the nuances of how IB decision-makers react to contextual circumstances.

Concluding remarks

We have highlighted the limitations of using direct techniques to study internationalization behaviors and introduced a scenario-based measurement tool to enhance the context of IB research. We have introduced, developed, and demonstrated our proposed tool’s validity in assessing sensitive IB topics such as internationalization motives and intentions. We conclude that the scenario-based measurement tool has the ability to capture the true behavior of the decision-maker by allowing them to overcome any biases. Therefore, the proposed method can enrich IB and international entrepreneurship literature and deepen our understanding of internationalization decision-making.

Appendices

Biographical notes

Antonin Ricard has a PhD in Business Administration (AMGSM-IAE, 2012—best International Management thesis prize—ATLAS/AFMI-FNEGE), a general engineering degree (ESME Sudria, 2002), and an MSc in Telecommunications (Leeds University, 2002—with distinction). Since 2014, he has worked for IAE Aix-Marseille, where he co-created the ICube lab in 2017 (to support student entrepreneurs) and the Chair of Legitimacy and Entrepreneurship in 2019. He was elected Dean of IAE Aix-Marseille in May 2021. His research is focused on entrepreneurship through two perspectives: legitimacy and internationalization (decision-making, effectuation, process, network, psychological distance), and he publishes regularly in diverse journals (Journal of International Entrepreneurship, Journal of International Management, Journal of Vocational Behavior, M@n@gement, Management international, etc.).

Emmanuelle Reynaud is a Professor of Strategy at IAE Aix-Marseille (CERGAM), Aix-Marseille University. An author of numerous national and international articles and books, one of her co-authored publications was identified by the Revue Française de Gestion as one of the 20 most influential articles in the journal’s 40-year history. Emmanuelle Reynaud was awarded the Académie des Sciences Commerciales prize for her book Sustainable Development at the Heart of the Company. She has already published an article on the scenario method in Management international.

Daisy Bertrand has a PhD in psychological sciences from the University of Liège in Belgium. Since 2012, she has been a Research Engineer at the CERGAM (Centre d’Etude et de Recherche en Gestion d’Aix-Marseille) at Aix-Marseille University. She specializes in methodology, data analysis, and modeling. Her research mainly focuses on consumer behavior in the collaborative economy. However, through her specialization and collaboration, she also works on other management topics, notably entrepreneurship and corporate social responsibility.

Subhan Shahid is an Assistant Professor in the Strategy, Sustainable Development, and Entrepreneurship Department at KEDGE Business School in Marseille, France. His ongoing research explores the intersection of entrepreneurship and psychology, specifically delving into the emotional and cognitive underpinnings of entrepreneurial behaviors, including exit and well-being. In addition to these areas, he is interested in a wide range of topics, including frugal innovation, sustainability, economic growth, employee behaviors, and family business.

Note

-

[*]

Corresponding author

Bibliography

- Acedo, F. J., & Florin, J. (2006). An entrepreneurial cognition perspective on the internationalization of SMEs. Journal of International Entrepreneurship, 4(1), 49–67. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10843-006-0482-9

- Aguinis, H., & Bradley, K. J. (2014). Best practice recommendations for designing and implementing experimental vignette methodology studies. Organizational Research Methods, 17(4), 351–371. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428114547952

- Alexander, C. S., & Becker, H. J. (1978). The use of vignettes in survey research. Public Opinion Quarterly, 42(1), 93–104. https://doi.org/10.1086/268432

- Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural Equation Modeling in Practice: A Review and Recommended Two-Step Approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411–423. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.411

- Arora, A., Jaju, A., Kefalas, A. G., & Perenich, T. (2004). An exploratory analysis of global managerial mindsets: a case of U.S. textile and apparel industry. Journal of International Management, 10(3), 393–411.

- Ashraf, N., Wadho, W., & Shahid, S. (2023). Faultlines in Family SMEs: The U-Shape Effect of Family Control on Innovativeness and Performance. M@n@gement, 26(3), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.37725/mgmt.2023.8135

- Auspurg, K., & Hinz, T. (2014). Factorial survey experiments. Sage Publication, Inc, California, United States of America.

- Auspurg, K., Hinz, T., Liebig, S., & Sauer, C. (2015). The factorial survey as a method for measuring sensitive issues. In U. Engel, B. Jann, P. Lynn, A. Scherpenzeel, & P. Sturgis (Eds.), Improving survey methods: lessons from recent research (pp. 137–149). Routledge, New York, United States of America.

- Birkinshaw, J., Brannen, M. Y., & Tung, R. L. (2011). From a distance and generalizable to up close and grounded: Reclaiming a place for qualitative methods in international business research. Journal of International Business Studies, 42(5), 573–581. https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2011.19

- Bittar, A. de V. (2018). Selling remanufactured products: Does consumer environmental consciousness matter? Journal of Cleaner Production, 181, 527–536. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.01.255

- Bradbury-Jones, C., Taylor, J., & Herber, O. R. (2014). Vignette development and administration: a framework for protecting research participants. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 17(4), 427–440. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2012.750833

- Brauer, P. M., Hanning, R. M., Arocha, J. F., Royall, D., Goy, R., Grant, A., Dietrich, L., Martino, R., & Horrocks, J. (2009). Creating case scenarios or vignettes using factorial study design methods. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 65(9), 1937–1945. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2009.05055.x

- Cabrol, M., & Nlemvo, F. (2013). Diversité de comportement des entreprises à internationalisation précoce et rapide: essai de validation d’une typologie. Revue de l’Entrepreneuriat, Vol. 11(3), 111–136. https://doi.org/10.3917/entre.113.0111

- Calof, J. L. (1993). The impact of size on internationalization. Journal of Small Business Management, 31(4), 60–69.

- Chang, S.-J., van Witteloostuijn, A., & Eden, L. (2020). Common Method Variance in International Business Research. In In: Eden, L., Nielsen, B., Verbeke, A. (eds) Research Methods in International Business. (pp. 385–398). Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-22113-3_20

- Chetty, S., Johanson, M., & Martín Martín, O. (2014). Speed of internationalization: conceptualization, measurement and validation. Journal of World Business, 49(4), 633–650. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2013.12.014

- Child, J. (2009). Context, comparison, and methodology in Chinese management research. Management and Organization Review, 5(1), 57–74. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1740-8784.2008.00136.x

- Child, J., Karmowska, J., & Shenkar, O. (2022). The role of context in SME internationalization – A review. Journal of World Business, 57(1), 101267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2021.101267

- Chonko, L. B., Tanner, J. F., & Weeks, W. A. (1996). Ethics in salesperson decision making: A synthesis of research approaches and an extension of the scenario method. The Journal of Personal Selling and Sales Management, 16(1), 35–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/08853134.1996.10754043

- Churchill, G. A. (1979). A Paradigm for Developing Better Measures of Marketing Constructs. Journal of Marketing Research, 16(1), 64–73. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224377901600110

- Cossette, P., & Audet, M. (1992). Mapping of an idiosyncratic schema. Journal of Management Studies, 29(3), 325–347. https://doi.org/10.1111/ j.1467-6486.1992.tb00668.x

- Davis, M. A., & Bobko, P. (1986). Contextual effects on escalation processes in public sector decision making. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 37(1), 121–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(86)90048-8

- De Cock, R., Andries, P., & Clarysse, B. (2021). How founder characteristics imprint ventures’ internationalization processes: The role of international experience and cognitive beliefs. Journal of World Business, 56(3), 101163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2020.101163

- Delios, A., Welch, C., Nielsen, B., Aguinis, H., & Brewster, C. (2023). Reconsidering, refashioning, and reconceptualizing research methodology in international business. Journal of World Business, 58(6), 101488. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2023.101488

- Deng, Z., Liesch, P. W., & Wang, Z. (2021). Deceptive signaling on globalized digital platforms: Institutional hypnosis and firm internationalization. Journal of International Business Studies, 52(6), 1096–1120. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-021-00401-w

- Diamantopoulos, A., & Winklhofer, H. M. (2001). Index Construction with Formative Indicators: An Alternative to Scale Development. Journal of Marketing Research, 38(2), 269–277. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkr.38.2.269.18845

- Doh, J., Rodrigues, S., Saka-Helmhout, A., & Makhija, M. (2017). International business responses to institutional voids. Journal of International Business Studies, 48(3), 293–307. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-017-0074-z

- Durance, P., & Godet, M. (2010). Scenario building: Uses and abuses. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 77(9), 1488–1492. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2010.06.007

- Eidelman, S., & Crandall, C. S. (2012). Bias in Favor of the Status Quo. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 6(3), 270–281. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2012.00427.x

- Evans, J., & Mavondo, F. T. (2002). Psychic of distance performance: an organizational operations. Journal of International Business Studies, 33(3), 515–532. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8491029

- Ferrell, O. C., Harrison, D. E., Ferrell, L., & Hair, J. F. (2019). Business ethics, corporate social responsibility, and brand attitudes: An exploratory study. Journal of Business Research, 95, 491–501. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.07.039

- Fiol, C. M., & Huff, A. S. (1992). Maps for managers: where are we? Where do we go from here? Journal of Management Studies, 29(3), 267–285. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.1992.tb00665.x

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104

- Gerbing, D. W., & Anderson, J. C. (1988). An updated paradigme for scale development incorporating unidimensionality and its assessment. Journal of Marketing Research, 25(2), 186–192. https://doi.org/10.1177/ 002224378802500207

- Glaum, M., & Oesterle, M.-J. (2007). 40 years of research on internationalization and firm performance: More questions than answers? Management International Review, 47(3), 307–317. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11575-007-0018-0

- Harmon-Jones, E., & Mills, J. (2019). An introduction to cognitive dissonance theory and an overview of current perspectives on the theory. In Cognitive dissonance: Reexamining a pivotal theory in psychology (2nd ed.). (pp. 3–24). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/0000135-001

- Helgeson, J. G., Voss, K. E., & Terpening, W. D. (2002). Determinants of mail-survey response: Survey design factors and respondent factors. Psychology and Marketing, 19(3), 303–328. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.1054

- Jackson, M., Harrison, P., Swinburn, B., & Lawrence, M. (2015). Using a Qualitative Vignette to Explore a Complex Public Health Issue. Qualitative Health Research, 25(10), 1395–1409. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732315570119

- Jafari-Sadeghi, V., Nkongolo-Bakenda, J.-M., Dana, L.-P., Anderson, R. B., & Biancone, P. Pietro. (2020). Home Country Institutional Context and Entrepreneurial Internationalization: The Significance of Human Capital Attributes. Journal of International Entrepreneurship, 18(2), 165–195. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10843-019-00264-1

- Johns, G. (2006). The essential impact of context on organizational behavior. Academy of Magagement Review, 31(2), 386–408. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2006.20208687

- Kahiya, E. T. (2020). Context in international business: Entrepreneurial internationalization from a distant small open economy. International Business Review, 29(1), 101621. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2019.101621

- Khavul, S., Pérez-Nordtvedt, L., & Wood, E. (2010). Organizational entrainment and international new ventures from emerging markets. Journal of Business Venturing, 25(1), 104–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2009.01.008

- Maitland, E., & Sammartino, A. (2015). Managerial cognition and internationalization. Journal of International Business Studies, 46(7), 733–760. https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2015.9

- Meier, O., & Meschi, P.-X. (2010). Approche intégrée ou partielle de l’internationalisation des firmes: les modèles Uppsala (1977 et 2009) face à l’approche «International New Ventures» et aux théories de la firme. Management International, 15(1), 11–18. https://doi.org/10.7202/045621ar

- Mudrack, P. E., & Mason, E. S. (2022). Vignette Themes and Moral Reasoning in Business Contexts: The Case for the Defining Issues Test. Journal of Business Ethics, 181(4), 979–995. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-021-04944-8

- Munteanu, D. R., Vanderstraeten, J., van Witteloostuijn, A., & Cambré, B. (2022). A systematic literature review on SME internationalization: a personality lens. Management Review Quarterly. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11301-022-00279-4

- Nguyen, D. C., & Tull, J. (2022). Context and contextualization: The extended case method in qualitative international business research. Journal of World Business, 57(5), 101348. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2022.101348

- Niittymies, A. (2020). Heuristic decision-making in firm internationalization: The influence of context-specific experience. International Business Review, 29(6), 101752. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2020.101752

- Nosanchuk, T. a. a. (1972). The Vignette as an Experimental Approach to the Study of Social Status: An Exploratory Study1. Social Science Research, 120(1), 107–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/0049-089X(72)90060-9

- Nummela, N., Saarenketo, S., & Puumalainen, K. (2004). A global mindset - A prerequisite for successful internationalization? Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences, 21(1), 51–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1090-9516(99)00017-610.1111/j.1936-4490.2004.tb00322.x

- Nunnally, J. C., & Bernstein, I. H. (1994). Psychometric theory. McGraw-hill, New York, United States of America.

- Oliveira, L., & Johanson, M. (2021). Trust and firm internationalization: Dark-side effects on internationalization speed and how to alleviate them. Journal of Business Research, 133, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.04.042

- Peterson, M. F., Arregle, J.-L., & Martin, X. (2012). Multilevel models in international business research. Journal of International Business Studies, 43(5), 451–457. https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2011.59

- Petricevic, O., & Teece, D. J. (2019). The structural reshaping of globalization: Implications for strategic sectors, profiting from innovation, and the multinational enterprise. Journal of International Business Studies, 50(9), 1487–1512. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-019-00269-x

- Petrou, A. P., Hadjielias, E., Thanos, I. C., & Dimitratos, P. (2020). Strategic decision-making processes, international environmental munificence and the accelerated internationalization of SMEs. International Business Review, 29(5), 101735. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2020.101735

- Ramirez, R., Mukherjee, M., Vezzoli, S., & Kramer, A. M. (2015). Scenarios as a scholarly methodology to produce “interesting research.” Futures, 71, 70–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2015.06.006

- Ribau, C. P., Moreira, A. C., & Raposo, M. (2018). SME internationalization research: Mapping the state of the art. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences / Revue Canadienne Des Sciences de l’Administration, 35(2), 280–303. https://doi.org/10.1002/cjas.1419

- Ricard, A., Le Pennec, E., & Reynaud, E. (2016). Representation as a driver of internationalization: The case of a singular Russian SME. Journal of International Entrepreneurship, 14(1), 96–120. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10843-016-0173-0

- Richter, N. F., Sinkovics, R. R., Ringle, C. M., & Schlägel, C. (2016). A critical look at the use of SEM in international business research. International Marketing Review, 33(3), 376–404. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMR-04-2014-0148

- Roxas, B., & Lindsay, V. (2012). Social Desirability Bias in Survey Research on Sustainable Development in Small Firms: an Exploratory Analysis of Survey Mode Effect. Business Strategy and the Environment, 21(4), 223–235. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.730

- Rugman, A. M., Verbeke, A., & Nguyen, Q. T. K. (2011). Fifty Years of International Business Theory and Beyond. Management International Review, 51(6), 755–786. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11575-011-0102-3

- Ruzzier, M., Antoncic, B., & Hisrich, R. D. (2007). The internationalization of SMEs: developing and testing a multi-dimensional measure on Slovenian firms. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 19(2), 161–183. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985620601137646

- Schweizer, R., & Vahlne, J.-E. (2022). Non-linear internationalization and the Uppsala model – On the importance of individuals. Journal of Business Research, 140, 583–592. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.11.025

- Shahid, S., Becker, A., & Kundi, Y. M. (2021). Do reputational signals matter for nonprofit organizations? An experimental study. Management Decision. https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-12-2020-1670

- Shahid, S., Liouka, I., & Deligianni, I. (2023). Signaling sustainability: Can it entice business angels’ willingness to invest? Business Strategy and the Environment, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.3638

- Shahid, S., Mei, M. Q., & Battisti, M. (2024). Entrepreneurial fear of failure and exit intention: The moderating role of a conducive social environment. International Small Business Journal, https://doi.org/10.1177/02662426241229878.

- Sharma, P., Leung, T. Y., Kingshott, R. P. J., Davcik, N. S., & Cardinali, S. (2020). Managing uncertainty during a global pandemic: An international business perspective. Journal of Business Research, 116, 188–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.05.026

- Sinkovics, R. R., Penz, E., & Ghauri, P. N. (2008). Enhancing the Trustworthiness of Qualitative Research in International Business. Management International Review, 48(6), 689–714. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11575-008-0103-z

- Stapleton, P. (2019). Avoiding cognitive biases: promoting good decision making in research methods courses. Teaching in Higher Education, 24(4), 578–586. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2018.1557137

- Teagarden, M. B., Von Glinow, M. A., & Mellahi, K. (2018). Contextualizing international business research: Enhancing rigor and relevance. Journal of World Business, 53(3), 303–306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2017.09.001

- Thévenard-Puthod, C. (2021). Pour une meilleure appréhension de la variété des trajectoires d’internationalisation des entreprises artisanales. Revue de l’Entrepreneuriat, Vol. 20(4), 41–72. https://doi.org/10.3917/entre1.pr.0011

- Tonkin, E., Wilson, A. M., Coveney, J., Meyer, S. B., Henderson, J., McCullum, D., Webb, T., & Ward, P. R. (2019). Consumers respond to a model for (re)building consumer trust in the food system. Food Control, 101, 112–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2019.02.012

- Vlačić, B., Loureiro, M. G., & Eduardsen, J. (2023). The process of the process of internationalisation: cognitive and behavioural perspectives in small ventures. European J. of International Management, 19(3), 307. https://doi.org/10.1504/EJIM.2023.128813

- Woodman, R. W. (2014). The Role of Internal Validity in Evaluation Research on Organizational Change Interventions. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 50(1), 40–49. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021886313515613

- Wright, G., Cairns, G., & Bradfield, R. (2013). Scenario methodology: new developments in theory and practice. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 80(4), 561–565. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2012.11.011

- Zucchella, A. (2021). International entrepreneurship and the internationalization phenomenon: taking stock, looking ahead. International Business Review, 30(2), 101800. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2021.101800

Appendices

Notes biographiques

Antonin Ricard est titulaire d’un doctorat en sciences de gestion (AMGSM‑IAE, 2012 - prix de la meilleure thèse en management international - ATLAS/AFMI-FNEGE), d’un diplôme d’ingénieur généraliste (ESME Sudria, 2002), et d’un MSc en télécommunication (Leeds University, 2002 - avec distinction). Il travaille pour l’IAE Aix Marseille depuis 2014 où il a cocréé le laboratoire icube en 2017 (pour enseigner les compétences du futur à travers l’entrepreneuriat) et la chaire Légitimité et entrepreneuriat en 2019. Il a été élu doyen de l’IAE Aix Marseille en mai 2021. Ses recherches portent sur l’entrepreneuriat à travers deux perspectives : la légitimité et l’internationalisation (prise de décision, effectuation, processus, réseau, distance psychologique) et il publie régulièrement dans diverses revues (Journal of International Entrepreneurship, Journal of International Management, Journal of Vocational Behavior, M@n@gement, Management international...).

Emmanuelle Reynaud est professeur des Universités en stratégie à l’IAE Aix-Marseille (CERGAM), Aix-Marseille Université. Auteur de nombreux articles et ouvrages nationaux et internationaux, une de ses publications co-écrites a été identifiée par la Revue Française de Gestion en tant qu’un des 20 articles les plus influents des 40 années de cette revue. Pour l’ouvrage « le développement durable au coeur de l’entreprise », Emmanuelle Reynaud a reçu le prix de l’académie des Sciences Commerciales. Dans Management international, elle a déjà publié un article sur la méthode des scénarios.

Daisy Bertrand est titulaire d’un doctorat en sciences psychologiques de l’Université de Liège en Belgique. Depuis 2012, elle est ingénieure de recherche au CERGAM (Centre d’Etude et de Recherche en Gestion d’Aix Marseille) d’Aix Marseille Université. Elle est spécialisée en méthodologie, analyse et modélisation des données. Ses publications portent essentiellement sur le comportement du consommateur de l’économie collaborative. Cependant, par sa spécialisation et ses collaborations, ses travaux concernent également d’autres thématiques en gestion, notamment l’entrepreneuriat ou la RSE.

Subhan Shahid est professeur assistant au département Stratégie, développement durable et entrepreneuriat de l’école de commerce KEDGE à Marseille, en France. Ses recherches actuelles explorent l’intersection de l’entrepreneuriat et de la psychologie, en particulier les fondements émotionnels et cognitifs des comportements entrepreneuriaux, y compris la sortie et le bien-être. Outre ces domaines, il s’intéresse à un large éventail de sujets, notamment l’innovation frugale, la durabilité, la croissance économique, les comportements des employés et les entreprises familiales.

Appendices

Notas biograficas

Antonin Ricard es doctor en Administración de Empresas (AMGSM-IAE, 2012 - premio a la mejor tesis de negocios internacionales - ATLAS/AFMI-FNEGE), ingeniero (ESME Sudria, 2002) y posee un máster en Telecomunicaciones (Leeds University, 2002 - con matrícula de honor). Trabaja en el IAE Aix Marseille desde 2014, donde cocreó el laboratorio icube en 2017 (para enseñar las competencias del futuro a través del emprendimiento) y la Cátedra de Legitimidad y Emprendimiento en 2019. Ha sido elegido decano del IAE Aix Marseille en mayo de 2021. Su investigación se centra en el emprendimiento a través de dos perspectivas: la legitimidad y la internacionalización (toma de decisiones, efectuación, proceso, red, distancia psicológica) y publica regularmente en diversas revistas (Journal of International Entrepreneurship, Journal of International Management, Journal of Vocational Behavior, M@n@gement, Management international...).

Emmanuelle Reynaud es profesora titular de Estrategia en el IAE de Aix-Marselle (CERGAM), Universidad de Aix-Marselle. Autora de numerosos artículos y libros nacionales e internacionales, una de sus publicaciones en coautoría fue identificada por la Revue Française de Gestion como uno de los 20 artículos más influyentes en los 40 años de historia de la revista. Por su libro «El desarrollo sostenible en el corazón de la empresa», Emmanuelle Reynaud recibió el premio de la Académie des Sciences Commerciales. En Management International, ya ha publicado un artículo sobre el método de escenarios.

Daisy Bertrand es doctora en Ciencias Psicológicas por la Universidad de Lieja (Bélgica). Desde 2012, es ingeniera de investigación en el CERGAM (Centre d’Etude et de Recherche en Gestion d’Aix Marseille) de la Universidad de Aix Marseille. Está especializada en metodología, análisis de datos y modelización. Sus publicaciones se centran principalmente en el comportamiento de los consumidores y en la economía colaborativa. Sin embargo, a través de su especialización y colaboraciones, también trabaja en otros temas de gestión, en particular el espíritu empresarial y la RSE.

Subhan Shahid es profesor asistente en el Departamento de Estrategia, Desarrollo Sostenible e Iniciativa Empresarial de la Escuela de Negocios KEDGE de Marsella (Francia). Su investigación explora la intersección entre el espíritu empresarial y la psicología, concretamente profundizando en los fundamentos emocionales y cognitivos de los comportamientos empresariales, incluida la salida y el bienestar. Además de estas áreas, está interesado en una amplia gama de temas, como la innovación frugal, la sostenibilidad, el crecimiento económico, los comportamientos de los empleados y la empresa familiar.

List of figures

Figure 1

The scenario method

List of tables

Table 1

Tools used in international business research

Table 2

Scenario and behavioural answers

Table 3

Descriptive statistics

Table 4

Factor matrixª

Table 5

Total variance explained

Table 6

KMO and Barlett’s test

Table 7

Correlation

10.7202/045621ar

10.7202/045621ar