Abstracts

Abstract

This study brings forward new evidence regarding child protection (CP) intervention for First Nations children and contributes to a longitudinal understanding of their trajectories within CP services. It raises questions regarding the persisting, unmet needs of First Nations children, families, and communities by identifying the CP factors associated with a first decision to provide post-investigation intervention and a first decision to close a case following post-investigation intervention among First Nations children. Anonymized administrative data (2002–2014; n = 1340) were used to conduct multivariate analyses, including longitudinal analyses using Cox proportional hazards modeling. Among First Nations children, those who were very young, who were reported for serious risk of neglect, and whose situation included indicators of repeated individual or family contact with CP services were more likely to receive post-investigation intervention. Similarly, those who were very young, provided services for neglect or serious risk of neglect, and whose situation was investigated at least twice before intervention was provided were more likely to have a longer first episode of intervention. The longitudinal analyses also revealed that more than one in two First Nations children (51.7%) receiving post-investigation intervention experienced a placement in out-of-home care during their interaction with CP services. This study contributes to a better understanding of intervention for First Nations children in Canada. It highlights how First Nations children receiving CP intervention live in situations in which their needs persist over time and how current services do not appear able to respond to these situations adequately, supporting the move towards autonomous, Indigenous–led CP services.

Keywords:

- child protection,

- First Nations,

- post-investigation intervention,

- longitudinal trajectories,

- neglect

Article body

Introduction

First Nations children are overrepresented in child protection (CP) services as compared to non-Indigenous children. The most recent available data indicate that the population rates at different stages of CP services are 3 to 14 times higher for First Nations children living in Canada than for non-Indigenous or White children (Crowe et al., 2021; De La Sablonnière-Griffin et al., 2016; Fallon et al., 2021; Ma, et al., 2019; Sinha et al., 2011). The overrepresentation of Indigenous children occurs across settler nations (Bilson et al., 2015; Rouland et al., 2019; Segal et al., 2019). While various sources documented disparities, the magnitude and trends regarding disparity remain unclear. This is primarily caused by incomplete or poorly populated administrative data and a heavy reliance on cross-sectional data. A longitudinal understanding of CP intervention for First Nations children is required to proceed with changes that will truly benefit Indigenous children, families, and communities in Canada. Australian data show how CP cross-sectional data are a gross underestimation of the number of children who will be investigated by CP before 18 years old. While 5.5% of Indigenous children in Australia experienced a completed investigation in 2005–06 (Tilbury, 2009), 28 to 39% of Indigenous children born between 1990 and 2003 and followed to age 14 to 18 ever experienced the same outcome (Bilson et al., 2015; Segal et al., 2019). In brief, the longitudinal rates were up to seven times higher than cross-sectional rates. The most recent annual rates of First Nations children investigated in Canada are higher than the Australian rate reported above, ranging from 6.4% (De La Sablonnière-Griffin et al., 2016) to 17% (Crowe et al., 2021). While the Indigenous populations and CP systems differ, we can assume that the cross-sectional rates in Canada greatly underestimate the real percentage of children that will experience at least one CP investigation before reaching 18 years of age.

Considering the above, better documenting the longitudinal trajectories of Indigenous children in CP services appears to be of central importance. This type of research would contribute to answering the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s (TRC) Calls to Actions (TRC, 2015). It could uncover challenges still faced in serving Indigenous children, families, and communities, therefore providing pressure to ensure that CP systems remain accountable as changes are implemented. Considering the contemporary developments related to CP in Canada, such as an Act respecting First Nations, Inuit and Métis children, youth and families, and considering that the TRC’s Calls to Actions were released in 2015, the dearth of research on First Nations children’s trajectories in CP services in Canada is deplorable. The current study, by providing a longitudinal analysis of the first provision and first closure of post-investigation CP intervention for First Nations children by a mainstream agency, aims to address the limitations of current research, namely the lack of longitudinal and First Nations–specific (not comparative) CP-related research.

Decision-Making in CP for First Nations Children in Canada

Current research on CP services in Canada and concerning First Nations children has mostly focused on two CP decisions, substantiation, and placement (during or at the conclusion of the investigation). This body of research works towards determining the risk of First Nations children experiencing these decisions compared to non-Indigenous children. Research on substantiation offers two takeaway messages. First, when analyzing all forms of reported maltreatment, the rate of substantiation for First Nations children remains statistically significantly higher than for non-Indigenous children when controlling for characteristics of the report, the child or the household; the higher rate is accounted for by the presence of risk factors for their caregiving figures, including substance abuse, social isolation and caregivers having a history of child maltreatment themselves (Sinha et al., 2013; Trocmé et al., 2004; Trocmé et al., 2006). Second, when considering only neglect cases, the interaction between being First Nations and two risk factors (substance abuse and being a lone caregiver) explains the overrepresentation of First Nations children (Sinha et al., 2013). Research on placement is more equivocal, with early research indicating that risk factors explain the overrepresentation (Trocmé et al., 2004), while more recent research found that the disparity was maintained (Breton et al., 2012; Trocmé et al., 2006). Nonetheless, placement was more likely for all children investigated in agencies in which 20% or more of the investigations involved Indigenous children (Chabot et al., 2013; Fallon et al., 2013; Fallon et al., 2015; Fluke et al., 2010).

Placement is a critical issue for First Nations communities in Canada, as highlighted by the TRC and its Calls to Action (2015). Yet, providing post-investigation intervention in CP includes not only out-of-home care, but also in-home services. Exploring the factors associated with the decision to provide post-investigation intervention in CP among the general population is a slowly emerging field of research in Canada (Jud et al., 2012; Smith et al., 2019) and the US (Jonson-Reid et al., 2017). Globally, provision of post-investigation CP intervention, whether in or out-of-home, aims at preventing future maltreatment and remedying the current maltreatment situation (Capacity Building Center for States, 2018; Trocmé et al., 2019).

Cross-sectional data from Canadian research indicates that between 38% (Ma et al., 2019; Sinha et al., 2011) and 64.5% (Breton et al., 2012) of cases investigated involving First Nations children were transferred to post-investigation intervention, a proportion always higher than for the comparison group (non-Indigenous or White children). Two multilevel (case and agency level) Canadian studies sought to identify factors associated with the decision to provide post-investigation intervention (Jud et al., 2012; Smith et al., 2019). While they did not focus on Indigenous children’s experience, they both included an agency-level variable concerning Indigenous children (agencies in which 20% or more of their investigations were about Indigenous children vs. agencies with a lower proportion), and Smith and colleagues (2019) also included Indigenous identity as a case-level variable. None of these variables were found to influence the decision.

Ma, Fallon, Alaggia and Richard (2019), using the same data as Smith and colleagues (2019), explored factors related to this decision among First Nations specifically. This study first documented characteristics of the investigations transferred to post-investigation intervention. Just under half (44.6%) included neglect situations, about three quarters (74.2%) concerned a child that had been previously investigated, and placement occurred in about one-fifth (19.2%) of these cases. An exploratory, tree-based decision model identified 12 decision nodes[1] among investigations concerning First Nations children to predict post-investigation intervention. The characteristics with the greatest influence was low social support for the child’s primary caregiver. When the primary caregiver had few social supports, 65% of cases received post-investigation intervention. When the primary caregiver had few social supports, the primary form of maltreatment was not physical abuse, and at least one unsafe housing condition existed or was unknown, 94% of cases were transferred to post-investigation intervention. In contrast, only 15% of cases were provided post-investigation intervention when the primary caregiver had few social supports and the primary maltreatment type was physical abuse or, if following the other path, when the primary caregiver was not noted to have few social supports and alcohol abuse issues, and the child under investigation did not have depressive symptoms.

Closing the CP Case after Post-Investigation Intervention

Research discussing the decision to close CP services has mostly conceptualized the “end” with regards to placement and through a permanency lens (e.g., family reunification, placement until majority, etc.), with virtually no research focusing on children served in-home and/or through short-term placements. The overall lack of sound and accessible longitudinal data on post-investigation intervention likely plays an important role in the absence of such research (Jenkins, 2017; Jonson-Reid et al., 2017; Trocmé et al., 2019). Nevertheless, it is imperative to address the lack of conceptualization and knowledge pertaining to families served by CP services without out-of-home care experiences, as they tend to represent a larger group of families than those who experience placement (Keddell, 2018). Descriptive data over a period of three years following a screened-in report in the province of Quebec highlighted that 56% of First Nations children did not experience a placement, which appears to support this affirmation for the population of interest (De La Sablonnière-Griffin et al., 2016).

The current study pursued two intricately tied objectives, which were to understand the factors associated with a first decision to 1) provide post-investigation CP intervention (in-home, out-of-home care, or both) and 2) close a CP case after post-investigation intervention, among First Nations children.

Methods

Data Source

Anonymized administrative CP data of Côte-Nord, a northern region in the province of Quebec, have been used. The data configuration was such that the mainstream regional CP organization controlled the access to the data they gathered about First Nations children, which were thus physically possessed by this organization. To ensure a degree of control and in recognition of the ownership of the data by the First Nations, this research was conducted under the guidance of an advisory committee comprised of representatives from the regional CP organization and from the delegated Innu social services agencies. A larger regional consultation mechanism was also used sporadically to validate the research objectives, preliminary results, and interpretations, with delegates from all Innu social services agencies of the region, as not all communities were represented on the advisory committee.

Brief Review of CP Decision-Making and Intervention Process in Quebec, Canada

Alleged situations of child maltreatment are first notified to CP services by diverse reporters (e.g., school personnel, neighbours) and summarily assessed to determine if the situation will be fully investigated or not. Reports that are screened-in are investigated to reach up to two decisions: whether the allegations are substantiated and, if they are, whether the child’s safety and development are in danger. When the latter is the case, post-investigation intervention is implemented. Post-investigation intervention is based on court-ordered or voluntary protective measures; it can include home-based intervention and out-of-home care. When the investigation deems the situation unsubstantiated or when the case is substantiated but the security and development of the child are not in danger, the child’s family can be referred to public and community resources as needed.

Once a child receives post-investigation intervention, the case is periodically reviewed to determine if the child’s safety and development remain in danger. A CP case is closed once the child’s safety and development are no longer considered in danger and represent the end of all post-investigation intervention. There are multiple pathways to achieving a situation in which the security and development of the child is no longer in danger, including, but not limited to, parents having taken adequate measures to remedy the situation, reaching 18 years of age, adoption, custodianship, emancipation, and long-term placement.

First Provision of Post-Investigation CP Intervention

First Screened-In Report Cohort

To answer the first objective, we selected First Nations children (aged 0 to 17) living in a First Nations community, and who experienced a first CP report screened-in for investigation between April 1, 2002, and March 31, 2014, in the region under study. Children who were transferred to or from another region prior to a first screened-in report, as well as children for whom the investigation was not completed by the end of the observation period (September 9, 2014), were not included in this cohort. This cohort totaled 1,340 children. Because the research interest was the first provision of post-investigation intervention, and because not all children who enter post-investigation intervention do so at their first investigation, additional analyses were conducted on a subset comprised of all cases that did not result in post-investigation intervention at the termination of the first investigation. Children who were transferred to or from another region after the conclusion of the first investigation (with no post-investigation intervention provided) but before their first instance of post-investigation intervention in the region under study were excluded (n = 5), resulting in a subset cohort of 720 children for whom no post-investigation intervention was provided following the first investigation.

Dependent Variable. The outcome measured for the first screened-in report cohort is provision of post-investigation CP intervention.

First case closure

First Post-Investigation Intervention Cohort

To answer the second objective, all First Nations children (aged 0–17) who experienced a first provision of post-investigation intervention (with a start date between April 1st, 2002, and March 31st, 2013) from the initial pool of 1340 individuals were included. This subsample comprised a total of 702[2] children. The end date was selected to allow a minimal case file length: the minimal observation length is about one year and five months, specifically from March 31, 2013, to September 9, 2014.

Dependent Variable. The outcome measured for this cohort is case closure. Given that the analyses on this cohort are longitudinal, time was measured in days. For children with a case closure during the observation period, time is calculated between the date of the decision at the investigation stage and the date at case closure. For censored cases, meaning children still receiving post-investigation intervention at the end of the study period, time was calculated between the date of the decision at the investigation stage and September 9, 2014.

Covariates

All the covariates were measured at the entry point into their specific cohort, namely at the decision point of the screening stage for the first screened-in reports cohort, and at the decision point of the investigation stage for the second cohort. They all are dichotomous and, unless otherwise stated, mutually exclusive. The covariates are divided into three groups: characteristics of the child, characteristics of the CP situation, and interactions between the family and CP services.

Characteristics of the child were limited to gender and age. Gender is a nominal variable identifying if the child is a boy or a girl, with being a girl used as the reference category. Age was measured at the date of the decision and consisted of a series of four dichotomous variables (under 2; 2 to 5; 6 to 11; 12 to 17), and for which the 6‑to‑11 category acted as the reference group. The characteristics of the situation included: the presence of at least one screened-out report prior to the first screened-in report (yes/no [reference category]); the source of referral, a series of seven dichotomous variables (extended family and neighbours [reference category]; police; education [schools and daycare]; CP agencies; professionals from other public services; professionals from private services; and other/unidentified referral sources) and the alleged reasons for reporting the child. The alleged reasons are a series of five dichotomous variables (physical and/or sexual abuse, including serious risk of physical and sexual abuse [reference category]; neglect; serious risk of neglect; psychological maltreatment, including exposure to intimate partner violence; serious behavioural issues that parents are unable to address), which are not mutually exclusive (a child can have up to three alleged reasons). Two variables pertained to the interaction between the family and CP services. Family known to the CP agency (yes/no [reference category]) identified if one or both parents of the child in the cohort were previously identified as parents of another child for whom an investigation was completed before the reception of the first screened-in report of the child under study. The unidentified parent variable (yes/no [reference category]) indicated case files in which only one parent, or no parent at all, were identified.

For the second objective, we also added two variables pertaining to the situation: the number of investigations prior to provision of post-investigation intervention (one [reference category]/two or more); and out-of-home placement during the investigation stage (yes/no [reference category]).

Analytical Framework

Descriptive analyses for the two cohorts of children are presented in Table 1. Logistic regression was used for the first objective. Cox proportional hazards modeling was used for the second objective. This type of analysis models time to the event of interest while taking into consideration the different lengths of observations for each individual under study, in addition to allowing for multiple independent variables. For both objectives, all the independent variables were included in the multivariate models given that no multicollinearity issues were noted.

Table 1

Characteristics of Children in the two Cohorts

Results

First Screened-In Report Cohort

A detailed description of children in each cohort is presented in Table 1. At their first screened-in reports, most First Nations children were below the age of 6 (60.5%). The most frequent source of referral was a family member or someone else from the child’s surroundings (26.5%), although a similar proportion of children (26.1%) was reported by a professional from a public service other than the police, the education system, or a CP agency. Just under a third (32.5%) had at least one screened-out report prior to their first screened-in report. Among the alleged grounds for reporting the child, neglect (44.8%) and serious risk of neglect (43.5%) were the most frequent. As up to three reasons could be noted for a single report, the percentages add to more than 100%. Serious behavioural issues was the least frequent alleged reason (13.3%). For 41.0% of the children, their family was known to the CP agency. The security and development of 615 (45.9%) children were considered in danger at the first investigation, resulting in the provision of post-investigation intervention (outcome measured for model 1 in Table 2). Among the 720 children who were not provided post-investigation intervention on their first investigation, 27.1% (n = 195) eventually experienced post-investigation CP intervention following a second, third, or fourth investigation (outcome measured for Model 2 in Table 2).

The results from the first logistic regression model (Model 1, Table 2) indicate the variables associated with a higher or lower likelihood of experiencing the provision of post-investigation intervention based on a first investigation. First Nations children aged under 2 at the decision to screen-in the report were 1.6 times (Odds ratio [OR]: 1.558) more likely to experience post-investigation intervention provision than were children aged 6 to 11. Other variables associated with an increased likelihood of post-investigation intervention included: children with prior screened-out reports (OR: 1.474); those reported by a professional from a public (OR: 1.400) or a private service (OR: 2.544), compared to those reported by the child’s family or neighbours; children who were reported for serious behavioural issues (OR: 1.564) or serious risk of neglect (OR: 1.828), compared to those reported for abuse; and those who were from a family known to the CP agency (OR: 1.756). A single variable was associated with a decreased likelihood of post-investigation interventions: having been reported by the police (OR: 0.694). Reversed, this finding indicated that a child reported by their family was 1.44 times more likely to receive post-investigation intervention, compared to a child reported by the police. As reported in Table 2, serious risk of neglect and family known to the CP agency were the most important contributors to this decision according to the Wald statistics (as the value of the Wald statistics increases, so does the contribution of the variable tested).

Table 2

Logistic Regression Models Predicting Post-Investigation Intervention Provision on a First Investigation (Model 1) or on a Higher-Order Investigation (Model 2)

Model 1: [X2 (17, n = 1340) – 111.711, p < 0.000]

Model 2: [X2 (17, n = 720) – 68.893, p < 0.000]

*p < 0.05. **p < 0.01. ***p < 0.001.

The logistic regression model on the subset of cases that did not result in post-investigation intervention following the first investigation is presented in Table 2 (Model 2). These analyses show that three variables, measured at the first screened-in report, increased the likelihood of post-investigation intervention on a second or higher-order investigation: having been under 2 (OR: 3.029), compared to those aged 6 to 11; having been reported for serious behavioural issues (OR: 2.509), compared to those reported for abuse; and coming from a family known to the CP agency (OR: 2.146). One variable, measured at the first screened-in report, was associated with a reduced likelihood of post-investigation intervention: having been aged 12 to 17 (OR: 0.482), compared to those aged 6 to 11 (conversely, children aged 6 to 11 were 2.08 times more likely to eventually experience intervention than those aged 12 to 17). According to the Wald statistics, having been under 2 at the first screened-in report and family known to the CP agency were the most important contributors to this decision.

First Post-Investigation Intervention Cohort

With regards to the cohort with a first provision of post-investigation intervention, the descriptive analyses (Table 1) show little change on most variables. The distribution of reasons for intervention varied slightly from the reasons for investigation, but the main categories remained neglect (49.9%) and serious risk of neglect (48.9%). The smallest category changed: physical and/or sexual abuse, including serious risk of these types of abuse, was the least frequent reason for intervention (9.8%). About a quarter of all cases with post-investigation intervention were transferred after at least two investigations (24.5%), and just over a fifth (21.7%) of children were placed in out-of-home care (including kinship care) during the investigation. A total of 558 children (79.5%) experienced a case closure during the observation period.

The Cox model for the first case closure is presented in Table 3 on the following page. These analyses show that case closure was associated with having been a teenager (Risk ratio [RR]: 1.442; compared to children aged 6 to 11 at the start of post-investigation intervention) and with having been reported by a professional from a private service at the first screened-in report (RR: 1.890; compared to children reported by family). Four variables were associated with longer duration of intervention before closure. Children under 2 at the start of post-investigation intervention (RR: 0.556); reversed, those 6 to 11 at start of intervention were 1.80 times more likely to experience closure compared to those under 2. Children who were provided post-investigation intervention for neglect (RR: 0.804) or serious risk of neglect (RR: 0.779) were less likely to experience closure, compared to those receiving intervention for physical or sexual abuse; put differently, children receiving intervention for abuse were 1.24 (compared to neglect) and 1.28 (serious risk of neglect) times more likely to experience closure. Finally, children experiencing a first post-investigation intervention after at least two investigations (RR: 0.726) were less likely to experience case closure; reversed, those receiving post-investigation intervention following their first investigation were 1.38 times more likely to experience case closure.

Table 3

Cox Model Predicting Case Closure on First Post-Investigation Intervention

A single variable had a time-varying effect. Having received intervention for serious behavioural issues was initially associated with a decreased prospect of case closure (RR: 0.593, compared to cases involving abuse), but its effects changed over time, meaning that the risk of case closure increased with each passing day. According to the Wald statistics, having been under 2 at the start of post-investigation intervention and entering post-investigation intervention after a minimum of two investigations were the most important contributors to this decision.

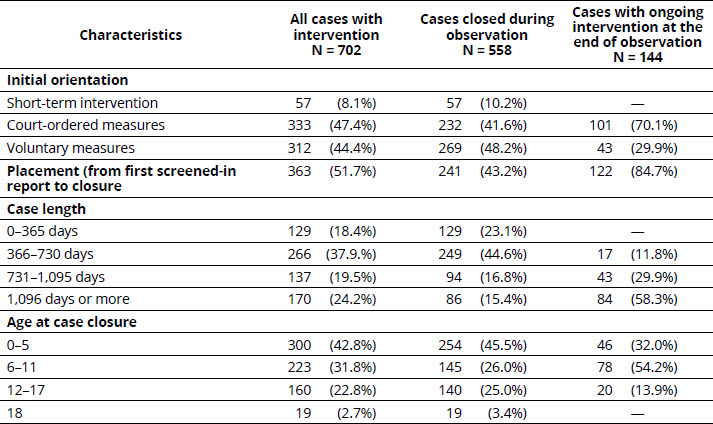

Additional descriptive analyses regarding post-investigation intervention are presented in Table 4. The observation length was not equal among all cases, ranging from a minimum of about 17 months to a maximum of about 11 years and 5 months. A small percentage of children (8.4%) were referred to short-term intervention, while the balance of children was almost equally split between voluntary (44.4%) and court-ordered measures (47.4%) at the initiation of the post-investigation services. More cases initially referred to voluntary measures were closed during the observation period (86.2% of 312 cases), than cases referred to courts (69.7% of 333 cases). Among cases still receiving intervention at the end of the observation period, 70.1% had initially been referred to courts. Placement was experienced by about half of the children (51.7%) at any point from their first investigation forward. Placement was highly prevalent in cases with ongoing post-investigation intervention at the end of observation, with 84.7% of children in this group having experienced at least one out-of-home care placement. In terms of case length, most children, among all cases (37.9%) and among cases closed (44.6%), received intervention from CP services for at least a year, but under two. Cases involving children aged 5 and under were the biggest group for both all cases opened (42.8%) and closed (45.5%), and cases involving school-aged children (6 to 11) represented the majority of cases with ongoing intervention (54.2%). Only a small portion of cases were closed when the child reached 18 years of age (3.4% of all closed cases).

Table 4

Descriptive Analysis of Cases Receiving Post-Investigation Intervention

Discussion

The aim of this study was to identify, among First Nations children, the factors associated with a first decision to provide post-investigation CP intervention and a first decision to close the CP case following post-investigation intervention. The results contribute to a better understanding of First Nations children’s trajectories within CP services in Canada, as it is one of the first to document and examine factors related to CP decisions and services occurring after the investigation stage. It also supports and extends previous findings regarding the role of neglect and of individual and/or family-level repeated contact with CP services in First Nations children’s trajectories.

Children that were more likely to receive post-investigation intervention for the first time were the very young children from families previously known to the CP agency, indicating family-level repeated contact with the CP system. A marker of repeated individual contact, the presence of at least one screened-out report, was also associated with provision of post-investigation intervention at a first investigation. Finally, the presence of serious risk of neglect as grounds for reporting was associated with post-investigation intervention following the first investigation. For some children, serious risk of neglect may serve as an indicator of repeated concerns, as it may relate to previous neglectful behaviours of the parents towards other children. For others, it may be related to the perceived caregivers’ capacities. While our study cannot draw firm conclusions, the high prevalence of serious risk of neglect among First Nations children’s cases and its association with provision of post-investigation intervention raises questions about how characteristics of First Nations caregivers may be interpreted with regards to assessing future risk to the point of warranting CP intervention. It raises questions about whether these risk factors are weighted differently than in non-Indigenous families, as previous research has shown that some household and parental risk factors were weighted differently when substantiating neglect investigations for First Nations children (Sinha et al., 2013).

Children who were reported by the police on their first screened-in report were less likely to receive post-investigation intervention following their first investigation. Police reports represented a substantial proportion of first screened-in reports (18.8%) for First Nations children, a proportion statistically significantly higher than for the majority group (De La Sablonnière-Griffin, 2020), which is congruent with the Ontarian study (Ma et al., 2019). Combined, these findings raise concerns around a possible visibility bias for First Nations families which may increase the overrepresentation of First Nations children at the investigation stage. A visibility bias refers to the elevated exposure of some groups to public services and mandated reporters, such as the police, because of “structural issues, such as poverty and violence” (Ma et al., 2019, p.60). The high frequency of police contacts self-reported by Indigenous peoples in Canada (David & Mitchell, 2021) appears to support this possibility. This study identified that Indigenous peoples were more likely to encounter police services for law enforcement issues (being arrested), but also for a host of reasons, including for non-enforcement issues (being a witness of a crime) or behavioural health-related issues (for themselves or their family). Given that police are a source of significantly more reports for First Nations children, but that these reports result in lower likelihood of post-investigation intervention, the exposure of First Nations families to police services may contribute to contact with CP in situations that were not, in fact, CP concerns.

Children entering post-investigation intervention at a very young age (below 2), who were provided services for neglect and/or serious risk of neglect and with repeated individual contact with CP services prior to the intervention (at least two investigations before intervention) were those more prone to a longer first episode of intervention. Situations of neglect under CP services are related to multiple adverse life circumstances, such as a parental history of mental/psychiatric problems and poverty (Mulder et al., 2018). CP agencies have little power to address or effect change regarding these adverse life circumstances (Carlson, 2017; Duva & Metzger, 2010; Morris et al., 2018), which could explain why these cases are less likely to be closed. First Nations families are confronted to many of these adverse life circumstances (Reading & Wien, 2009; Salée, 2006; Viens, 2019), which is likely contributing to longer CP serving time. In addition, the root causes of their adverse life circumstances lie in colonialist and discriminatory policies, both past and contemporary (Bombay et al., 2020; Czyzewski, 2011; Gone et al., 2019; TRC, 2015; Viens, 2019; Wilk et al., 2017), further limiting CP services’ capacity to support families in altering their life circumstances. Discriminatory policies included the federal government’s underfunding of child and family services for First Nations living in First Nations communities (First Nations Child and Family Caring Society of Canada et al. v Attorney General of Canada, 2016 CHRT 2). For an extended period, the funding structure concretely deprived First Nations children, families, and communities of resources to offer preventative and support services that could help alleviate situations deemed neglectful or at serious risk of being so (First Nations Child and Family Caring Society of Canada et al. v Attorney General of Canada, 2016 CHRT 2; Sinha & Kozlowski, 2013).

Finally, the longitudinal descriptive results shed light on what happens to First Nations children during the post-investigation intervention. In this study, about one fifth (21.7%) of children with post-investigation intervention were placed into care during the investigation leading to the post-investigation intervention (Table 1), a finding similar to Ontarian data (19.3%; Ma et al., 2019). However, the descriptive, longitudinal data revealed that placement is far more prevalent among First Nations children receiving post-investigation intervention; when considering all the interactions between the child and CP services, from their first screened-in report to either the closure of their case or the end of data available, more than one in two children (51.7%) ever experienced placement in out-of-home care during their interaction with CP services. While placement during the investigation stage was not associated with case closure, the sheer magnitude of placement experienced at any point by the First Nations children receiving post-investigation services warrants us to suggest that additional research on placement as it pertains to post-investigation service and case closure be conducted. Analyses including the types and lengths of placements and the moves while in care are needed to better understand how placement influences post-investigation CP intervention, service trajectories and case closure.

Implications for Practice and Policy

We recognize that First Nations living in Quebec aim to rely first and foremost on their own governance of CP services (Awashish et al., 2017) to ensure the well-being of First Nations children. Recent developments in Canada, most notably an Act respecting First Nations, Inuit and Métis children, youth and families, signal some support for these endeavours, albeit with important shortcomings regarding the funding component (Blackstock, 2019; Metallic et al., 2019). Reports and calls to action from two recent Quebec-wide Commissions (on relations between public services and the Indigenous population: Viens, 2019; on CP services: Special Commission on the Rights of the Child and Youth Protection [SCRCYP], 2021) also point to the importance of Indigenous-led and -governed CP services. It is, however, likely that concrete change will take time to occur (Paul, 2016).

The results from our study raise the question of whether CP services compensate for a lack of accessible and effective support and prevention services to meet the families’ needs. With children involved in CP coming from families already known at an early age and for reasons of serious risk of neglect, and with children receiving intervention for extended periods when neglect or serious risk of neglect are involved, it appears as though the families are not able to access services that would help address the situation. As such, the results from our study illustrate the discriminatory funding practices acknowledged by the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal (First Nations Child and Family Caring Society of Canada et al. v Attorney General of Canada, 2016 CHRT 2). While some prevention and support services have been put in place since 2009 in First Nations communities in Quebec, underfunding continues and important variations in the services offered occur (FNQLHSSC, 2011). In addition, difficulties in accessing mental health (Collin-Vézina et al., 2011; Lefrançois, 2016) and other public services (Viens, 2019) have been repeatedly noted, potentially compounding issues in First Nations families. First Nations children, families, and communities deserve adequately funded services responding to their needs.

Another issue pertains to CP practices around neglect, and more specifically around serious risk of neglect (Caldwell & Sinha, 2020; De La Sablonnière-Griffin et al., 2016). Serious risk of neglect is a sufficient ground for intervention in the Quebec legislation since 2007, although virtually no research has been conducted to document the situations served under this ground. Neglect is a culturally situated concept, intricately tied to parenting norms and expectations (Hearn, 2011). Parenting norms and expectations among Indigenous populations are known to be different from, but equally as conducive to healthy development as western practices (Cross et al., 2000; Croteau, 2107; Guay, 2015; Neckoway et al., 2007). Nonetheless, discriminatory actions in the CP system are repeatedly based on misunderstandings of Indigenous worldviews and parenting norms (Grammond, 2018; Guay, 2015; SCRCYP, 2021; Viens, 2019). Instead of trying to redefine what neglect, or by extension serious risk of neglect, implies, Caldwell and Sinha (2020) suggest we redesign our interventions to focus on children’s well-being. CP interventions towards situations of neglect are limited as they tend to focus on family-level risk factors, even when it is understood that neglect is not directly caused by parents or caregivers but rather embedded in larger structural issues. Using a child well-being lens would support interventions addressing the various levels involved (e.g., the family, but also the community and larger social structures), while better aligning with Indigenous worldviews, and consequently enabling a move towards culturally safer CP services.

Strengths and Limitations

This study is innovative in studying longitudinally the first trajectory in and out of post-investigation CP intervention for a group of First Nations children. Nonetheless, some limitations must be noted. First, it is possible that children have moved in the region under study during the study period. If these children had previously received CP intervention in another region, it was impossible to know from the data used. Thus, it is possible that the first post-investigation intervention in the study was not a child’s first CP intervention.

Second, the group of First Nations children studied was selected according to the data structure, politico-legal criteria regarding funding of First Nations children and family services, and the nature of our partnership. While we wanted to study CP intervention for First Nations children, we could not rely on self-identification given the use of administrative data. We selected children whom the CP workers identified as First Nations (information primarily derived from self-identification) and who resided in a First Nations community (information primarily derived from the address of the family). The residence status was selected for two reasons. The first reason stems from our acknowledgment of the funding discrepancies for children living in First Nations communities. The second reason is based on the nature of our partnership: the partnership was with delegated agencies serving First Nations children living in First Nations communities and did not include organizations representing or supporting First Nations families residing elsewhere. Our results are thus not generalizable to First Nations children residing outside of communities or for whom services are funded through a different mechanism.

Finally, by relying solely on administrative data, this study could not account for some caregivers and household factors identified as playing a role in CP decision-making, such as the family’s socio-economic status or substance abuse by a caregiver (Jenkins et al., 2017; Ma et al., 2019; Sinha et al., 2013). An avenue to better understand First Nations children’s trajectories in CP services would be to use a family framework. Henderson and colleagues (2017) illustrated that time to CP intervention was generally longer for the eldest child in a family (according to maternal birth order), leading to consequences such as being older at the time of a first intervention and thus being less likely to gain permanency if placed in out-of-home care. Understanding the eldest child’s trajectory and the temporal pattern of CP contacts, decisions, and intervention for siblings in relation to the eldest child’s situation would likely provide useful information to better serve First Nations families in contact with CP services.

Conclusion

This study brings forward new evidence regarding CP post-investigation intervention for First Nations children and contributes to a longitudinal understanding of their trajectories within CP services. It raises questions regarding the persisting, unmet needs of First Nations children, families, and communities. First Nations peoples living in Canada comprise a vibrant diversity of peoples; while the paths towards adequate services for First Nations children are likely as diverse as the First Nations themselves, First Nations–led, autonomous, and adequately funded services must be a realistic possibility for all Nations and communities that wish to embark on this path in order to best meet the needs of children and families who come into contact with CP services.

Appendices

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the advisory committee members, the members of the Indigenous coordination table and the managers and staff of the CPRCN/CISSS de la Côte-Nord who supported this project; the children and families discussed in this study; as well as Martin Chabot, for his vital work in creating the dataset used in this study.

Notes

-

[1]

A node identifies a characteristic that distinguishes the most between cases transferred to post-investigation services and cases closed at the investigation stage.

-

[2]

This number is lower than the total number of cases that were opened according to the first cohort of children studied. The reason for this difference is that the observation period for provision of post-investigation intervention is shorter with the second cohort. Concretely, for the first objective, this information is the outcome measured and is observed until September 9, 2014, whereas in the second cohort, it is the entry point into the cohort and is observed only until March 31, 2013.

Bibliography

- An Act respecting First Nations, Inuit and Métis children, youth and families. (2019). S.C. 2019, c. 24. https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/f-11.73/index.html

- Awashish, W., Collin, M.-N., Ellington, L., & Plamondon-Gomez, P. (2017). Another step toward self-determination and upholding the rights of First Nations children and families: Consultation process for the reform of the First Nations child and family services (FNCFS) program. FNQLHSSC. https://files.cssspnql.com/index.php/s/QhxLg6W5JU3ahGL

- Bilson, A., Cant, R. L., Harries, M., & Thorpe, D. H. (2015). A longitudinal study of children reported to the child protection department in Western Australia. The British Journal of Social Work, 45(3), 771–791. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bct164

- Blackstock, C. (2019). Indigenous child welfare legislation: A historical change or another paper tiger? First Peoples Child & Family Review, 14(1), 5–8. https://fpcfr.journals.publicknowledgeproject.org/index.php/FPCFR/article/view/367

- Bombay, A., McQuaid, R., Young, J., Sinha, V., Currie, V., Anisman, H., & Matheson, K. (2020). Familial attendance at Indian residential school and subsequent involvement in the child welfare system among Indigenous adults born during the sixties scoop era. First Peoples Child & Family Review, 15(1), 62–79. https://doi.org/10.7202/1068363ar

- Breton, A., Dufour, S., & Lavergne, C. (2012). Les enfants autochtones en protection de la jeunesse au Québec : leur réalité comparée à celle des autres enfants [Indigenous children under child protection in Quebec: Their reality compared to other children]. Criminologie, 45(2), 157–185. https://doi.org/10.7202/1013724ar

- Caldwell, J., & Sinha, V. (2020). (Re) Conceptualizing neglect: Considering the overrepresentation of Indigenous children in child welfare systems in Canada. Child Indicators Research, 13(2), 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-019-09676-w

- Capacity Building Center for States. (2018). Child protective services: A guide for caseworkers. Children’s Bureau, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.childwelfare.gov/pubs/usermanuals/cps2018/

- Carlson, J. (2017). ‘What can I do’? Child welfare workers’ perceptions of what they can do to address poverty. Journal of Children and Poverty, 23(2), 161–176. https://doi.org/10.1080/10796126.2017.1358588

- Chabot, M., Fallon, B., Tonmyr, L., MacLaurin, B., Fluke, J., & Blackstock, C. (2013). Exploring alternate specifications to explain agency-level effects in placement decisions regarding Aboriginal children: Further analysis of the Canadian Incidence Study of Reported Child Abuse and Neglect Part B. Child Abuse & Neglect, 37(1), 61–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2012.10.002

- Collin-Vézina, D., De La Sablonnière-Griffin, M., & Dutrisac, C. (2011). Development of a mental health services organization model among the First Nations of Quebec communities. FNQLHSSC. https://files.cssspnql.com/index.php/s/Z5xXiBJQVOuOyp9

- Cross, T., Earle, K. A., & Simmons, D. (2000). Child abuse and neglect in Indian country: Policy issues. Families in Society, 81(1), 49–58. https://doi.org/10.1606/1044-3894.1092

- Croteau, K. (2017). État des connaissances sur les enjeux relatifs à l’exercice de la parentalité des mères autochtones en situation de protection de la jeunesse [State of knowledge regarding parenthood of Indigenous mothers in child protection situations]. Intervention, 145, 53–62.

- Crowe, A., Schiffer, J., with support from, Fallon, B., Houston, E., Black, T., Lefebvre, R., Filippelli, J., Joh-Carnella, N., & Trocmé, N. (2021). Mashkiwenmi-daa Noojimowin: Let’s have strong minds for the healing (First Nations Ontario incidence study of reported child abuse and neglect – 2018). Child Welfare Research Portal. https://cwrp.ca/publications/mashkiwenmi-daa-noojimowin-lets-have-strong-minds-healing-first-nations-ontario

- Czyzewski, K. (2011). Colonialism as a broader social determinant of health. International Indigenous Policy Journal, 2(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.18584/iipj.2011.2.1.5

- David, J.-D., & Mitchell, M. Contacts with the police and the over-representation of Indigenous peoples in the Canadian criminal justice system. Canadian Journal of Criminology and Criminal Justice, e20200004. https://doi.org/10.3138/cjccj.2020-0004

- De La Sablonnière-Griffin, M. (2020). Les trajectoires de services des jeunes des Premières Nations et allochtones desservis par la protection de la jeunesse sur la Côte-Nord: Perspective sur la première récurrence de services [Doctoral dissertation, McGill University; Child Protection Services’ Trajectories of First Nations and non-Indigenous Children in the North Shore region: Perspective on the first service recurrence]. eScholarship@McGill. https://escholarship.mcgill.ca/concern/theses/7d278z878?locale=en

- De La Sablonnière-Griffin, M., Sinha, V., Esposito, T., & Trocmé, N. (2016). Trajectories of First Nations children youth subject to the Youth Protection Act – Component 3: Analysis of maintream youth protection agencies administrative data. FNQLHSSC. https://files.cssspnql.com/index.php/s/yaTlZtDakBS0pFE

- Duva, J., & Metzger, S. (2010). Addressing poverty as a major risk factor in child neglect: Promising policy and practice. Protecting Children, 25(1), 63–74.

- Fallon, B., Chabot, M., Fluke, J., Blackstock, C., MacLaurin, B., & Tonmyr, L. (2013). Placement decisions and disparities among Aboriginal children: Further analysis of the Canadian incidence study of reported child abuse and neglect part A: Comparisons of the 1998 and 2003 surveys. Child Abuse & Neglect, 37(1), 47–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2012.10.001

- Fallon, B., Chabot, M., Fluke, J., Blackstock, C., Sinha, V., Allan, K., & MacLaurin, B. (2015). Exploring alternate specifications to explain agency-level effects in placement decisions regarding Aboriginal children: Further analysis of the Canadian Incidence Study of Reported Child Abuse and Neglect Part C. Child Abuse & Neglect, 49, 97–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.04.012

- Fallon, B., Lefebvre, R., Trocmé, N., Richard, K., Hélie, S., Montgomery, H. M., Bennett, M., Joh-Carnella, N., Saint-Girons, M., Filippelli, J., MacLaurin, B., Black, T., Esposito, T., King, B., Collin-Vézina, D., Dallaire, R., Gray, R., Levi, J., Orr, M., Petti, T., Thomas Prokop, S., & Soop, S. (2021). Denouncing the continued overrepresentation of First Nations children in Canadian child welfare: Findings from the First Nations/Canadian Incidence Study of Reported Child Abuse and Neglect – 2019. Ontario: Assembly of First Nations.

- First Nations Child and Family Caring Society of Canada et al. v Attorney General of Canada. (2016). CHRT 2. https://www.canlii.org/en/ca/chrt/doc/2016/2016chrt2/2016chrt2.html

- First Nations of Quebec and Labrador Health and Social Services Commission [FNQLHSSC]. (2011). Évaluation de l’implantation des services sociaux de première ligne dans quatre communautés des Premières Nations du Québec [Implementation evaluation of the first-line social services pilot project in four Quebec First Nations communities]. FNQLHSSC. https://files.cssspnql.com/index.php/s/rgNpLt8DQakpA0y

- Fluke, J., Chabot, M., Fallon, B., MacLaurin, B., & Blackstock, C. (2010). Placement decisions and disparities among Aboriginal groups: An application of the decision making ecology through multi-level analysis. Child Abuse & Neglect, 34(1), 57–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.08.009

- Gone, J. P., Hartmann, W. E., Pomerville, A., Wendt, D. C., Klem, S. H., & Burrage, R. L. (2019). The impact of historical trauma on health outcomes for Indigenous populations in the USA and Canada: A systematic review. American Psychologist, 74(1), 20–35. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000338

- Grammond, S. (2018). Federal legislation on Indigenous child welfare in Canada. Journal of Law and Social Policy, 28(1), 132–151. https://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/jlsp/vol28/iss1/7

- Guay, C. (2015). Les familles autochtones: des réalités sociohistoriques et contemporaines aux pratiques éducatives singulières [Indigenous families: Sociohistorical and contemporary realities and unique educational practices]. Intervention, 141, 12–27.

- Hearn, J. (2011). Unmet needs in addressing child neglect: Should we go back to the drawing board? Children and Youth Services Review, 33(5), 715–722. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2010.11.011

- Henderson, G., Jones, C., & Woods, R. (2017). Sibling birth order, use of statutory measures and patterns of placement for children in public care: Implications for international child protection systems and research. Children and Youth Services Review, 82, 321–328. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.10.001

- Jenkins, B. Q. (2017). A systems approach to reducing child protection recurrence [Doctoral dissertation, Griffith University]. Griffith University Research Repository. https://doi.org/10.25904/1912/2475

- Jenkins, B. Q., Tilbury, C., Mazerolle, P., & Hayes, H. (2017). The complexity of child protection recurrence: The case for a systems approach. Child Abuse & Neglect, 63, 162–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2016.11.020

- Jonson-Reid, M., Drake, B., Kohl, P., Guo, S., Brown, D., McBride, T., Kim, H., & Lewis, E. (2017). What do we really know about usual care child protective services? Children and Youth Services Review, 82(Supplement C), 222–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.09.019

- Jud, A., Fallon, B., & Trocmé, N. (2012). Who gets services and who does not? Multi-level approach to the decision for ongoing child welfare or referral to specialized services. Children and Youth Services Review, 34(5), 983–988. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2012.01.030

- Keddell, E. (2018). The vulnerable child in neoliberal contexts: the construction of children in the Aotearoa New Zealand child protection reforms. Childhood, 25(1), 93–108. https://doi.org/10.1177/0907568217727591

- Lefrançois, B. (2016). Report of inquest concerning the deaths of Charles Junior Grégoire-Vollant, Marie-Marthe Grégoire, Alicia Grace Sandy, Céline Michel-Rock & Nadeige Guanish. Bureau du coroner. https://www.coroner.gouv.qc.ca/fileadmin/Coroners/Rapport_final_-_anglais.pdf

- Ma, J., Fallon, B., Alaggia, R., & Richard, K. (2019). First Nations children and disparities in transfers to ongoing child welfare services in Ontario following a child protection investigation. Children and Youth Services Review, 101, 207–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.04.010

- Ma, J., Fallon, B., & Richard, K. (2019). The overrepresentation of First Nations children and families involved with child welfare: Findings from the Ontario incidence study of reported child abuse and neglect 2013. Child Abuse & Neglect, 90, 52–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.01.022

- Metallic, N., Friedland, H., & Morales, S. (2019). The promise and pitfalls of C‑92: An Act respecting First Nations, Inuit and Métis children, youth and families. Yellowhead Institute. https://yellowheadinstitute.org/bill-c-92-analysis/#analysis2

- Morris, K., Mason, W., Bywaters, P., Featherstone, B., Daniel, B., Brady, G., Bunting, L., Hooper, J., Mirza, N., & Scourfield, J. (2018). Social work, poverty, and child welfare interventions. Child & Family Social Work, 23(3), 364–372. https://doi.org/10.1111/cfs.12423

- Mulder, T. M., Kuiper, K. C., van der Put, C. E., Stams, G.-J. J. M., & Assink, M. (2018). Risk factors for child neglect: A meta-analytic review. Child Abuse & Neglect, 77, 198–210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.01.006

- Neckoway, R., Brownlee, K., & Castellan, B. (2007). Is attachment theory consistent with Aboriginal parenting realities? First Peoples Child & Family Review, 3(2), 65–74. https://doi.org/10.7202/1069465ar

- Paul, J. (2016). Evaluation of child protection in federalist countries: Recommendations for increasing effectiveness and re-establishing self-determination within Indigenous communities. Journal of Policy Practice, 15(3), 188–211. https://doi.org/10.1080/15588742.2015.1044685

- Reading, C. L., & Wien, F. (2009). Health inequalities and social determinants of Aboriginal peoples’ health. National Collaborating Centre for Aboriginal Health. https://www.ccnsa-nccah.ca/docs/determinants/RPT-HealthInequalities-Reading-Wien-EN.pdf

- Rouland, B., Vaithianathan, R., Wilson, D., & Putnam-Hornstein, E. (2019). Ethnic disparities in childhood prevalence of maltreatment: Evidence from a New Zealand birth cohort. American Journal of Public Health, 0(0), e1–e3. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2019.305163

- Salée, D. (2006). Quality of life of Aboriginal people in Canada. IRPP Choices, 12(6), 1–40. https://irpp.org/wp-content/uploads/assets/research/aboriginal-quality-of-life/quality-of-life-of-aboriginal-people-in-canada/vol12no6.pdf

- Segal, L., Nguyen, H., Mansor, M. M., Gnanamanickam, E., Doidge, J. C., Preen, D. B., Brown, D. S., Pearson, O., & Armfield, J. M. (2019). Lifetime risk of child protection system involvement in South Australia for Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal children, 1986–2017 using linked administrative data. Child Abuse & Neglect, 97, 104–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.104145

- Sinha, V., Ellenbogen, S., & Trocmé, N. (2013). Substantiating neglect of First Nations and non-Aboriginal children. Children and Youth Services Review, 35(12), 2080–2090. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2013.10.007

- Sinha, V., & Kozlowski, A. (2013). The structure of Aboriginal child welfare in Canada. International Indigenous Policy Journal, 4(2), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.18584/iipj.2013.4.2.2

- Sinha, V., Trocmé, N., Fallon, B., MacLaurin, B., Fast, E., Prokop, S. T., & Richard, K. (2011). Kiskisik Awasisak: Remember the children. Understanding the overrepresentation of First Nations children in the child welfare system. Assembly of First Nations. https://cwrp.ca/publications/kiskisik-awasisak-remember-children-understanding-overrepresentation-first-nations

- Smith, C., Fallon, B., Fluke, J., Mishna, F., & Decker Pierce, B. (2019). Organizational structure and the ongoing service decision: The influence of role specialization and service integration. Human Service Organizations: Management, Leadership & Governance, 43(5), 375–391. https://doi.org/10.1080/23303131.2019.1661928

- Special Commission on the Rights of the Child and Youth Protection [SCRCYP]. (2021). Instaurer une société bienveillante pour nos enfants et nos jeunes [Building a caring society for our children and youth]. Gouvernement du Québec. https://www.csdepj.gouv.qc.ca/fileadmin/Fichiers_clients/Rapport_final_3_mai_2021/2021_CSDEPJ_Rapport_version_finale_numerique.pdf

- Tilbury, C. (2009). The over-representation of Indigenous children in the Australian child welfare system. International Journal of Social Welfare, 18(1), 57–64. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2397.2008.00577.x

- Trocmé, N., Esposito, T., Nutton, J., Rosser, V., & Fallon, B. (2019). Child welfare services in Canada. In L. Merkel-Holguin, J. D. Fluke, & R. D. Krugman (Eds.), National Systems of Child Protection: Understanding the International Variability and Context for Developing Policy and Practice (pp. 27–50). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-93348-1_3

- Trocmé, N., Knoke, D., & Blackstock, C. (2004). Pathways to the overrepresentation of Aboriginal children in Canada’s child welfare system. Social Service Review, 78(4), 577–600. https://doi.org/10.1086/424545

- Trocmé, N., MacLaurin, B., Fallon, B., Knoke, D., Pitman, L., & McCormack, M. (2006). Understanding the overrepresentation of First Nations children in Canada’s child welfare system: An analysis of the Canadian incidence study of reported child abuse and neglect (CIS‑2003). Centre of Excellence for Child Welfare. https://cwrp.ca/fr/publications/mesnmimk-wasatek-catching-drop-light-understanding-overrepresentation-first-nations

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada [TRC]. (2015). Honouring the truth, reconciling for the future: Summary of the final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. http://www.trc.ca/assets/pdf/Honouring_the_Truth_Reconciling_for_the_Future_July_23_2015.pdf

- Viens, J. (2019). Public Inquiry Commission on relations between Indigenous Peoples and certain public services in Québec: listening, reconciliation and progress – Final report. Gouvernement du Québec. https://www.cerp.gouv.qc.ca/fileadmin/Fichiers_clients/Rapport/Final_report.pdf

- Wilk, P., Maltby, A., & Cooke, M. (2017, 2017/03/02). Residential schools and the effects on Indigenous health and well-being in Canada – a scoping review. Public Health Reviews, 38(8), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40985-017-0055-6

List of tables

Table 1

Characteristics of Children in the two Cohorts

Table 2

Logistic Regression Models Predicting Post-Investigation Intervention Provision on a First Investigation (Model 1) or on a Higher-Order Investigation (Model 2)

Table 3

Cox Model Predicting Case Closure on First Post-Investigation Intervention

Table 4

Descriptive Analysis of Cases Receiving Post-Investigation Intervention