Abstracts

Abstract

Participation, a key component of strategy work, is examined to focus on bottom-up strategy work in this longitudinal study based on ob¬servations of a global firm’s strategy workshop. Results show some middle managers are better positioned than others to engage in strategy work because of previous international experience, prior strategy-workshop insights, and cultural, behavioral, and personality traits. A typology of strategist profiles identify those who characteristically participate, and associated vignettes reveal participation approaches. The research concludes strategy-workshop proposal consideration and adoption are subject to the participant’s identity, adding to the debate on the role identity plays in strategizing practices.

Keywords:

- participation,

- micro-strategizing,

- strategy workshops,

- identity,

- ethnography,

- strategy-as-practice

Résumé

Cet article s’intéresse à la participation dans la formation des stratégies par des workshops. Une étude ethnographique montre que certains participants sont mieux placés que d’autres pour s’engager dans ce travail en raison de leur expérience internationale, de leurs connaissances sur les workshops stratégiques et de leurs traits culturels, comportementaux et de personnalité. Une typologie des profils de stratèges identifie ceux qui participent de manière significative. La recherche conclut que la participation dans des workshops stratégiques est soumise à l’identité du participant et contribue au débat sur le rôle de l’identité du stratège dans l’élaboration des stratégies.

Mots-clés :

- participation,

- micro-strategie,

- workshops stratégiques,

- identité,

- ethnographie,

- strategie enpratique

Resumen

Este artículo se ocupa de la participación en la formación de estrategias a través de talleres. Un estudio etnográfico muestra que algunos participantes están en mejores condiciones que otros para participar en este trabajo debido a su experiencia internacional, su conocimiento de talleres estratégicos y sus rasgos culturales, conductuales y de personalidad. Una tipología de perfiles de estratega identifica a quienes participan de manera significativa. La investigación concluye que la participación en talleres estratégicos está sujeta a la identidad del participante y contribuye al debate sobre el rol de la identidad del estratega en el desarrollo de estrategias.

Palabras clave:

- participación,

- microestrategia,

- talleres de estrategia,

- identidad,

- etnografía,

- estrategia-como-práctica

Article body

Scholars have become increasingly interested in exploring middle managers’ role (Rouleau & Balogun, 2011; Besson & Mahieu, 2011; Wooldridge, Schmid, & Floyd, 2008) in the strategizing process (Golsorkhi, Rouleau, Seidl, & Vaara, 2015), especially in the international context (Boyett & Currie, 2004), and how their participation in this process can enhance strategies and subsequent strategy implementation (Wooldridge & Floyd, 1990; Raes, Heijltjes, Glunk, & Roe, 2011; Ahearne, Lam, & Kraus, 2014). Logically, for these ideas to be expressed and considered, middle managers must be involved in the strategizing activities (Laine & Vaara, 2015). However, even when they are invited to participate, middle managers confront problems engaging in strategy work (Mantere & Vaara, 2008).

This research investigates middle managers’ strategizing work in the particular context of workshops (Hodgkinson, Whittington, Johnson, & Schwarz, 2006). The literature converges toward the idea organizations commonly use this practice (MacKay, Chia, & Nair, 2020), but it still fails to provide tangible results from its occurrence (Johnson, Prashantham, Floyd, & Bourque, 2010). In that vein, we explore the assumption middle managers may refrain from participating or their voices are not recognized by other participants, especially top managers, and thus they do not deliver their ideas during these workshops. Our research question is: even when invited to participate, who really participates in strategy workshops and how do they participate?

Our analysis is grounded in the strategy-as-practice (SAP) approach that allows recognizing a broader range of actors in strategy work than the traditional top-down approach, which has mainly been limited to top managers (Vaara & Whittington, 2012; Hoon, 2007; Rouleau, 2005). Part of this research is elaborated on microlevel activities related to participation and studies that have also explored how specific practices either enable or impede participation (Laine & Vaara, 2015). However, the research shows little is still known about why strategy processes often lead to participation problems (Mantere & Vaara, 2008) and are thus not inclusive, especially in international firms (Boyett & Currie, 2004).

One important reason for this is linked to three assumptions about the nature of strategy work (Mantere & Vaara, 2008): (a) employees at lower levels are less strategically aware (Armenakis & Harris, 2002), (b) strategizing is closely linked to other activities that take place in the organization (Whittington, Molloy, Mayer, & Smith, 2006), and (c) its emerging nature and constant evolution (Burgelman et al., 2018). Moreover, middle managers’ involvement in strategy relies on top-level granting of legitimacy (Mantere, 2008).

This research relates to the results of an ethnographic study conducted in a 2016 strategy workshop within an international firm active in the technology sector. The analysis of who participates (i.e., who raises ideas and how) during each of the workshops subsessions and even during breaks provides a typology of nine participation profiles. We show a workshop invitation implies neither everyone contributes to the discussion nor all participants are equally equipped to strategize because of their personality types and traits, acquired skills, or ability to express their input and their relationships with others to gain support for their ideas. We propose one other view on why such workshops fail. We argue not only the emission but also the acceptance of ideas could rely on the identities of the participants and attributes linked to their personality types and traits.

This paper is structured as follows: in the first part, we illuminate the research gap existing in the literature on strategy workshops and the micro-strategizing practices managers use to promote their ideas not only in a generic but also workshop context. In the second part, we develop the research design. The participant typology as a key result finding is presented in the third part. The paper then discusses the role identity and personality play in strategic input’s adoption during strategy workshops. Lastly, we present the study’s contributions, limitations, and basis for further research.

Literature Review

Participation in Strategy Workshops

Reopening the Debate on Strategy Workshops

The debate on strategy workshops as strategy practice (Whittington, 2006) has been ongoing since the 2000s with some researchers seeing the aim of two- or three-day gatherings as a means for executives to escape their daily work settings in order to brainstorm on elaborating and changing their organizations’ strategies (Mezias, Grinyer, & Guth, 2001).

However, despite Mezias et al.’s (2001) descriptions of resulting advanced contributions, the literature continues to question why such workshops fail to keep their goals. While explaining the cognitive risks that make a top management team unable to agree, Hodgkinson and Wright (2002) revealed strategy workshops can fail because of a “misalignment with the ongoing practice that is brought about by consultants and external facilitators and praxis of strategizing in the firm” (Johnson et al., 2010, p. 1611). Beyond these conclusions, a more systematic survey with 1,337 returns concerning the practices of strategy workshop revealed such workshops mostly rely on a discursive, not an analytical, approach to strategy formation (Hodgkinson et al., 2006). These results confirm Bowman’s (1995) findings that the practice does not include middle managers, but rather remains the “business of top management” (p. 4).

The research that followed not only considered who gets invited to workshops and stated middle managers provide new and fresh contributions to the decision-making process but also focused on an anthropological approach to behavioral dynamics between actors based on the concept of ritualization (Bourque & Johnson, 2008; Johnson et al., 2010) - workshops are considered emotionally intensive rituals with various characteristics, such as removal of proposals degree, liturgy use, and specialist involvement.

These works’ explanations, to our knowledge, have not been questioned. We argue recent research on strategy workshops fails to identify who among the participants actually participates in the practice. More recent literature has focused on how to organize workshops to get the best outcome (Kryger, 2018; Healey, Hodgkinson, Whittington, & Johnson, 2015), and these authors call for not only objective measures of outcomes but also better study of both the “changes in communication frequency among participants” (Healey et al., 2015, p. 524) and the nature of proposals participants suggest, especially if these proposals diverge from the norms. Similarly, in seeking to analyze the nature of discourses and dialogues that take place during strategy workshops, Duffy and O’Rourke (2015) revealed a “group’s dialogue in the workshop discourse displayed an emphasis on achieving shared understanding rather than winning a debate” (p. 404 but they did not explain who does and does not take part in the dialogues.

Based on these identified gaps and calls and following Jarzabkowski, Balogun, and Seidl (2007) who found the “doing of strategy is shaped by the identity of the strategist” (p. 14), we argue besides the nature of the workshop, who among the participants is really taking part in the practice should matter and, consequently, should affect the workshop outcome.

A Practice Based Approach to Emerging Strategies in Strategy Workshops

Taking a pragmatic practice approach to understanding and explaining what is going on in an organization allows us to approach people in their everyday strategizing activities, which can include proposing and defining issues that require attention (Dutton, Ashford, O’Neill, Hayes, & Wierba, 1997), holding topical meetings, preparing reports and presentations (Chia, 2004), enacting micro-practices through everyday interactions and conversations (Rouleau, 2005), and other talk, tinkering, and everyday business actions (Jarzabkowski, Burke, & Spee, 2015), even those accompanied by jokes (Jarzabkowski & Lê, 2015).

As discussed by Jarzabkowski, Kaplan, Seidl, and Whittington (2015), emergence of a strategy involves continuous deliberation during which those who do the strategizing, independent of the level they may be at in the organization and how they do it form the patterns that emerge in distinct ways. Traditionally, strategizing has been represented as a top-down approach; however, there is increasing awareness strategizing must be a bottom-up process in which those who directly interact with the environment in which the organization is active contribute to strategy (Jarzabkowski, 2008). Studies into bottom-up perspectives for strategy making and organizational change (Wooldridge et al., 2008) further emphasized middle managers’ central role in bringing about change (Burgelman, 1983; Glaser, Stam, & Takeuchi, 2016; Heyden, Fourné, Koene, Werkman, & Ansari, 2017), even though middle managers’ initiatives and ideas are not necessarily always appreciated by top management (Dutton et al., 1997; Rouleau, 2005; Friesl & Kwon, 2017). Noting middle managers’ involvement in strategy work is reliant on a mix of formal and informal mechanisms (Vaara & Whittington, 2012), such participation still relies on the top level granting legitimacy (Mantere, 2008).

Middle Managers’ Micro-Strategizing Practices

What strategists do is connected to who the strategists are and the situation or setting in which they are and act. Wooldridge and Floyd (1990) elaborated on strategic involvement well beyond managerial ranks and noted that “who is involved may be every bit as important as how they are involved” (p. 232). While the involvement of, for example, middle managers should be substantive rather than nominative, the real purpose of increasing strategic involvement should be to improve the quality of decisions (Burgelman et al., 2018), not only facilitate implementation.

Early literature on middle managers mainly focused on understanding the changing nature of the middle manager’s role in contemporary organizations (Kanter, 1986; Dopson & Neumann, 1998). Later, strategy scholars started considering middle managers as legitimate strategic actors (Floyd & Wooldridge, 1997; Floyd & Lane, 2000; Wooldridge et al., 2008) and took their roles in top-down and bottom-up strategizing seriously. Such studies deliberated the middle manager’s role in both integrating ideas and diversifying views. Other studies have examined the middle manager’s involvement in sensemaking processes (Rouleau & Balogun, 2011) and how middle manager-initiated organizational change engenders an above-average level of employee support (Heyden et al., 2017). Although power relations affect all people in an organization, the middle manager’s strategizing is likely to be affected by the sense of power in not only hierarchical structures (Anicich & Hirsh, 2017, p. 662) but also a workshop setting, where different staff levels are represented. Across such findings, many scholars to emphasize the beneficial effects of middle managers’ involvement in strategy (Mantere, 2008).

Identity Work in Practice

Discourses Being Shaped in Strategy Workshops

Organizations commonly hold strategy workshops, which may influence a firm’s strategic direction by providing a formal event and unique forum in an informal setting to examine and change strategy content (Healey et al., 2015). In this paper’s context, strategizing is discussed in the sense of some level of deliberate strategy formulation, the organizing work involved in the implementation of strategies, and all the other activities that lead to the emergence of organizational strategies, conscious or not (Vaara & Whittington, 2012). The holding of strategy workshops can fall under what Mintzberg and Waters (1985) called process strategy whereby leadership tries to control the process of strategy but essentially leaves the content to others (i.e., the middle managers). In exploring the role of workshops in strategy development, Hodgkinson et al. (2006) highlighted the approach’s discursive nature and that they are not inclusive of organizational participants, notably middle managers. Scholars who have focused on the involvement in strategy work beyond top management showed there is interest in such participation and distinct information dissemination and commitment benefits exist (Wooldridge & Floyd, 1990; Mantere & Vaara, 2008; Laine & Vaara, 2015).

Empowering people to participate in strategy development also makes them subject to the strategy discourse, which results in changes to their identity as organizational members (Oakes, Townley, & Cooper, 1998). Through participation in discourses and practices, individuals involved in strategy “are transformed into subjects who secure their sense of meaning, identity and reality” (Knights & Morgan, 1991, p. 269). Involvement may also bring with it changes and new pressures (Clegg & Kornberger, 2015) that everyone may not be willing to bear.

Strategists and Their Identity Work

Strategy-as-practice (SAP) research has highlighted the roles and identities of the organizational members engaged in strategy work and has acknowledged identity matters (Knights & Morgan, 1991; Rouleau, 2005; Mantere & Vaara, 2008; Rasche & Chia, 2009; Seidl & Whittington, 2014; Nicolini & Monteiro, 2016). Vaara and Whittington (2012) suggested there is a need to better comprehend the special roles and identities individuals play in strategizing in various contexts. When the conceptualization of such identities are expressed through strategy discourse, they can affect emerging strategies and their acceptance. Importantly, the variety of discursive practices can either enable or constrain organizational actors as strategy practitioners (Vaara, 2010).

Identity dynamics are relevant because through these processes, strategists make sense of what is going on and what they are doing over time (Beech & Johnson, 2005). Both external and internal actors (including middle managers) are involved in strategy work; thus, the question of who can be considered a strategist arises (Hautz, Seidl, & Whittington, 2017). Going deeper, strategy practice research has defined strategy practitioners as “actors who shape the construction of practice through who they are, how they act and what resources they draw upon” (Jarzabkowski et al., 2007, p.11).

Goffman’s dramaturgical perspective provides further insights into the construction of strategists’ professional identities (Goffman, 1959) and ways in which strategy workshop participants act when they are either onstage or offstage in the workshop setting. The onstage performance differs from the offstage actions, where the actors (in our case, the strategists) let their guards down and do not put on a front for the workshop audience (Goffman, 1959, p. 112). Instead, when individuals are offstage, they engage in various roles depending on who they are with. This brings to light that what matters is not only the individual’s behavior and personality type and traits but also the setting, time, audience, and other attending workshop participants.

Research Design

In order to grasp the possible difference that might exist between strategizing practices across participants and how middle managers contribute to bottom-up emerging strategies, we used ethnographic techniques (Van Maanen, 1988), such as participant observation during the strategy workshops. We chose to refer to this type of workshop as the bottom-up strategizing practice widely developed for workshops across international firms and discussed in studies by other scholars (Hendry & Seidl, 2003; Hodgkinson et al., 2006; Schwarz, 2009; Healey et al., 2015).

Presentation of the Analysis Case: The Firm and the Strategy Workshop

The empirical context of this qualitative study is a global firm in the technology sector. The firm was experiencing external pressures, and although a high-level strategy had been developed, it needed to reassess this strategy going forward because it sought buy-in and support from the organization members at large. To this end, a week-long strategy workshop that (for the first time) included middle managers in addition to top management was organized. The workshop was held in February 2016 in the headquarters’ city, but at an off-site, rented location. Timewise, the workshop was held halfway into the organization’s quadrennial strategic cycle to raise awareness and facilitate implementation of the current plan, prepare for the next strategic cycle, and strengthen the team spirit.

For this workshop, the director invited 53 staff members to participate. Of these, 21 middle managers, senior middle managers, and director-level staff came from the field offices and 32 from the headquarters. Of the invitees, 20 (38%) were females, and 33 (62%) were males. If the same criteria had been set for these invitees as for an earlier workshop in 2011 (only senior middle managers and above), eight females (or 25%) of a total 31 participants would have been present.

The workshop was composed of plenary sessions and breakout working groups with presentations on key topics. Plenary sessions were led by appointed moderators from among the participants, and the breakout working groups assigned one of their members to report on the group discussions. This approach offered all participants the chance, not an obligation, to take, at some point, a lead role in fully understanding an issue and communicating it to the other participants, thus ensuring wider engagement in discussions. Following each session and working group report, the floor was open for comments and discussions to allow for exchange between the participants, regardless of their levels.

Data Sources and Data Collection

Data were gathered through participative observations during 40 sessions, which lasted eight to nine hours including coffee/tea and lunch breaks every day for five days, intended to focus on strategy-making activities.

Verbatim session transcriptions from audio recordings were produced for analysis. The main on-site researcher, a participant at the workshop, also recorded extensive field notes during the observations. The organization made official video recordings of workshop sections but the researcher relied on distinct audio recordings made with a simple organizer-authorized, visibly placed device, which was turned off during breaks and informal discussions.

Data analyzed for this research comes from 12 audio-recorded strategic episodes. Each of these episodes lasted between 25 and 98 minutes and followed a predetermined agenda, which was not always kept to the schedule because the participants were often engaged in lively discussions. The sessions could be considered distinct strategic episodes (Hendry & Seidl, 2003) because aspects of initiation, conduct, and termination could be observed. Eighteen hours of audio recordings from the interactive parts of the working sessions are available for the full study to which this paper contributes.

At the end of each day’s session, the on-site researcher documented observations that could not be registered from the audio or video recordings in a reflection journal. Having the said middle manager acting as an on-site researcher also allowed access to information on the workshop preparation and documentation.

Data Analysis and Coding

The analytical approach was open ended and inductive, and it was guided by a broad interest in how middle managers’ discourses, which may reflect who they are and the roles they play in the firm, shape their strategizing, and how these consequently affect decision making. The data coding process followed an iterative-inductive approach (O’Reilly, 2005).

The literature review on strategy work was used as a first-order category: who are strategists (e.g., Burgelman,1983; Whittington, 1996; Wooldridge & Floyd, 1990; Jarzabkowski et al., 2007), agency in strategy work (e.g., Chia & Holt, 2006; Mantere, 2008), what is strategic and what is not (e.g., Mintzberg & Waters, 1985), and where does strategizing take place (e.g., Hendry & Seidl, 2003; Hodgkinson et al., 2006; Jarzabkowski & Seidl, 2008). Through transcribing and reading the data with the literature review in mind, some interesting topics emerged. These relate to who takes action and strategizes (considering gender, practitioners, identity, and middle managers), what discourses take place and how are they put forward (requests to speak, being asked to present, and interruptions), what is proposed (proposals for change and improvement and complaints), how is input expressed (power, discourses, attitudes, issue selling, negotiation, and formulations), and whether this leads anywhere in the trajectory of decision making within the workshop setting.

We engaged in an iterative process to analyze the data. During data collection, we focused on observing discourses and interactions among the various organizational actors who contributed to the crafting and interpretation of the strategies (strategy work). We examined how the participants made sense of the information shared in presentations and exchanged in discussions and observed the situations they faced during the workshop, the actions they took, and how they exerted and expressed their views. After transcribing the recorded workshop sessions’ interactions, the scripts were divided into temporal segments to analyze possible differences over the duration of the workshop in terms of participation (beginning vs end of the workshop) and the nature of discussions (based on topic and highly strategic vs less strategic). The organizational hierarchy level the person interacting in the discourse held was also recorded. We also wanted to understand if some managers and groups thereof were more likely to ground their proposals in already agreed-to plans and link back to a common direction as stipulated in their firms’ official documents in their discourses.

The coding process informed second-order themes relating broadly to strategizing literature on sensemaking (Balogun, 2003), gender and equality (Rouleau, 2005; Vaara & Whittington, 2012), jokes (Jarzabkowski & Lê, 2015), improvisation (Vaara & Whittington, 2012), identity (Beech & Johnson, 2005), and role play (MacIntosh & Beech, 2011) and focused on the individual in a workshop setting.

Findings

Typology of Participants in a Strategic Workshop

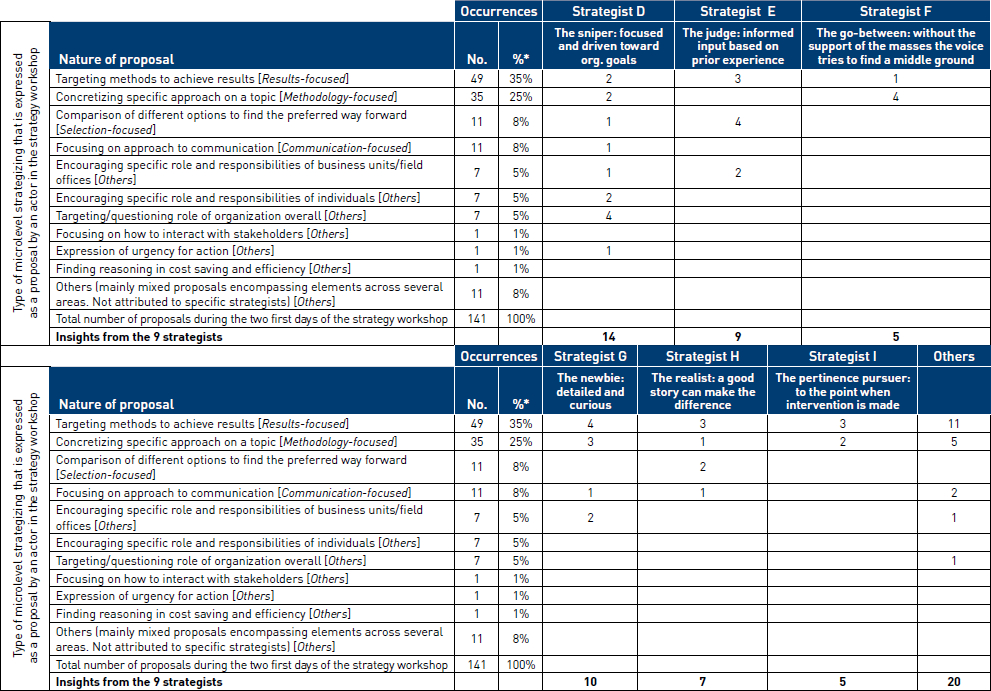

The data on the practitioners and their praxis in a strategy workshop setting were analyzed, and a typology of identity domains in strategizing in SAP research emerged based on the six types of practitioner profiles: the over-achiever, the diplomat, the sniper, the judge, the newbie, and the realist; and the four types of proposals they offered for consideration: results focused, methodology focused, selection focused, and communication focused. Each of these domains represents a possible area of praxis where the practitioner’s identity plays a role.

This typology (Table 1c) is thus a useful organizing device to understand the kind of discourses a certain type of individual can engage in to most likely gain support for their proposals. This can include understanding who is better suited and may be more successful when involved in strategy workshops based on their personal identity and personality and when additional support is required.

Three other practitioner profiles can also be traced in the proposals put forward in workshops; however, these are more in the shadow of what occurs in such a setting in terms of the quantity of proposals put forward. These practitioners are not silent bystanders in the workshop setting, as some others are, but they are less visible. However, this does not make them less important in the ongoing strategizing work. These are the advisor, the go-between, and the pertinence pursuer. Detailed practitioner profiles of those who are in the spotlight and use the workshop setting as a stage for proposals and those who remain in the shadows, but not as silent bystanders, can be found in Table 1.

Putting These Participants Onstage

Following Langley’s (1999, 2007) and Langley and Abdallah’s (2016) suggestions for presenting qualitative analysis results, we decided to present our results using a thematic approach. This choice enhances the generalization potential of our results, although it may reduce the accuracy of the description. Moreover, the SAP research field has used detailed vignettes to reveal underlying dynamics (Rouleau, 2005; Kaplan, 2011). In referencing the literature on workshops and strategizing to sharpen the insights developed from the data’s inductive analysis, we could identify sometimes complementary and, other times, conflicting dynamics associated with strategy workshops as orchestrated stage play (Fig.1).

Table 1

Linking the Type of Proposal for an Outcome from a Strategy Workshop to the Middle Manager Strategists’ Identities as Proposal Originators through Generalized Profiles (with detailed descriptions)

*This total number (and associated percentage) also includes the 21 proposals expressed by the director that can be attributed to multiple strategists, several of which may serve as summaries of collective sensemaking.

Figure 1

Strategy actors involved in strategy workshops: their positions, and actions

The presented data analysis findings reflect the bottom-up strategy work and what middle managers do in practice while strategizing during strategy workshops. The analysis of categories falls into four elements. First, the strategizing process can be considered a collective stage play. Second, invited middle manager do not participate equally in the stage play. Third, the stage play leads to specific content. Last, some middle managers use deviant practices to get their ideas adopted in the stage play. We elaborate on each of these discourses in distinct vignettes in the next section and present insights into how the profiles in Table 2 can be traced throughout the discourses that support the proposals and demonstrate they contribute to the collective strategy work that takes place in strategy workshops.

Thus, by defining a profile typology of middle managers and having associated some specific strategizing micro-practices to their personality types and traits, the results presented through the typology seek to answer the question of who participates in these workshops, and the associated vignettes present how they participate.

Vignette 1: Collective Stage Play During a Strategy Workshop

At the outset, we observed those who were more likely to take the floor and be in the limelight onstage to present their proposals and views were those the director had selected and assigned a certain role. Senior management had prevalidated the content they were to share as relevant for discussion at the workshop. This was particularly the case at the beginning of the workshop sessions week. At the workshop’s outset, it was mentioned that all attendees were present in their own personal capacity and not as a representative or spokesperson to defend their service areas or regions, affirming that everyone’s opinion was valuable.

Despite this assurance, the workshop structure and time pressure for each session together with the understanding of the floor giving-and-taking practices voiced at the outset of the workshop, few proposals were put forward, especially not from regional staff or female participants. Thus, if we imagine the workshop setting as a stage with spotlights on those who moderate a session, who have an authorized programmed presentation to make, and who take the floor to provide proposals and views, only a third of reoccurring participants are in this group (see Fig.1’s main actor). In several cases, the main actor was also represented by the over-achiever profile (as per Table 1). The rest of the workshop participants were left in the shadowed area of the stage, outside the limelight, and more passive in terms of taking the floor, observing, and engaging in one-on-one discussions with their proposals on the side (see Fig.1 extras and sometimes the audience). Considering the discourses throughout the workshop, the same people often engage (Table 2 characteristics: long experience in organization, loud and/or well-spoken behavioral types) and discuss their proposals publicly among the same people in what seems to become a dialogue at times with the moderator, who may ask for clarification, and the director, who may respond to a remark made and possibly steer the direction. These discourses and interactions that happen in the limelight onstage are nonetheless the ones recorded in the workshop notes for follow-up discussion, decision making, and implementation. Proposals therein are seen as workshop outcomes and considered for budgeted implementation. Why then do some share their proposals only around the table where they are seated in the shadow in an informal manner? (An observation made by the on-site researcher.) There may be several reasons for this:

a feeling of a lack of legitimacy (the floor had not been given, and there is no authorization from the hierarchy);

-

a lack of confidence due to a lower level in the hierarchy, being new to the organization or from a field office and neither familiar nor comfortable with possible judgement that could be associated with the floor taking (Fig.1’s newbie). Observation made (Strategist G: the newbie as per Table 1):

I have heard a lot of terms that to me, I cannot say as a newcomer anymore, I have to say ex-newcomer, are still overlapping and interrelated. And the distinction is not always clear[…]

discomfort with speaking publicly in the predominant language (English) because other languages are common in an international setting (See Table 2 with profiles); and/or

a lack of interest in engaging due to unclear incentives to take the floor.

As noted, based on our study, a framework for identifying factors that may affect individual’s participation in strategy work can be developed (See Table 1). Moreover, the actors and their actions and positions can be observed in the strategy workshop setting when they are onstage and offstage, and these inform the discussion (Table 1).

Table 2

Generalized Profiles of Strategy Workshop Practitioners

Vignette 2: Proposal Initiations and Trajectories

At the outset, top management invited everyone to share their ideas and noted the participants were present in the workshop not because of the department they represent, but because they have unique insights. However, in the interventions, when examples were given that may not have been on any prepared script, the hierarchical level of staff members present would come up, as would comments about staff being from headquarters versus field offices. As noted earlier, Table 2 provides typical profiles of the active practitioners in the strategy workshop. Intentional or not, this reiteration of hierarchical levels and location/association by top management and participants may have influenced the discussions and proposals. Staff were reminded of their positions, and this implicitly signaled whether their input had (or had not) relevance to workshop explorations. This was notable when proposals encompassing public sensemaking were followed by indication of time or tardiness (for six of the 141 proposals).

The various hierarchical groups’ discourses and the proportion of time allocated to their interventions were not equally distributed. Senior managers were more vocal than middle managers, and senior managers were afforded significantly longer interventions. It also emerged some members had undergone related training and understood problems and potential solutions in specific ways, but others had not. Females and males did not intervene in workshops with equal frequency. Males were in the majority at the workshop across all levels, and analysis of the discourses revealed females were comparatively quiet during the course of the workshop. In the first two days of the workshop, 141 proposals of different kinds were put forward. Of these, only 20 (14%) came from female participants. The nature of the proposals and their occurrences can be seen in Table 3, noting the majority of proposals either targeted methods to achieve desired results (results-focused) or concretized specific approaches to be taken on topical challenges that were being encountered (methodology-focused). The type of micro-level strategizing an actor in the strategy workshop proposed varied and belonged mainly to one of the following types of proposals: results-focused, methodology-focused, selection-focused, or communication-focused; other proposals were placed in an others grouping.

These proposals were considered throughout the workshop, and either (a) proposals were rejected, (b) proposals were neutrally viewed, or (c) proposals were adopted and perhaps, even implemented. Top management representatives also immediately rejected some proposals, which were never subject to discussion or input from others, sometimes without giving specific reasons. Other proposals were not directly rejected during the workshop; however, nothing concrete materialized back in the business, and they may still be pending realization. Similarly, some proposals were presented as team proposals; thus, to some degree, several practitioners supported the idea. However, if the meeting attendees did not openly support or reject the idea but remained neutral, there was no follow-up discussion. For several adopted proposals, middle managers proposed the initial idea, and then, top management supported the idea. Later in the workshop, middle managers offered additional feedback related to the same idea and provided possible implementation details (with reference to Table 2 characteristics, noting that support would come from those with longer experience in the organization). Finally, the director would support the idea’s adoption, and it would be carried forward. These could then be noted in the workshop output report and observed in actions taken following the workshop. Proposals receiving collective backing but lacking top management’s blessing remained just good proposals.

Table 3

Nature of Proposals and their Occurrences in the Strategy Workshop Sessions

Vignette 3: Being Heard in Strategy Workshops

Participating in and Contributing to Workshop Sessions

Fully participating in strategy meetings is not a simple undertaking, especially for female participants. (See Table 1 for Strategists C: The advisor, F: The go-between, I: The pertinence pursuer.) Some male workshop participants would raise their hand early on and be given the floor to speak first by the moderator during the allotted time for questions. Sometimes, the same participants would interject to complement and agree with a point a previous intervener had raised and thus cut the queue. Male participants more commonly exhibited aggressive floor-taking behavior (see Table 1 for Strategists A: The over-achiever, E: The judge, H: The realist), except when the main preceding presenter was a female and sought to clarify something. The session moderators could have but did not intervene to deal with such strident behavior. Perhaps, other workshop structures to allow for co-creation and collective strategizing could have been implemented. It is unknown if such behavior is linked to a lack of confidence, for which alternative measures could have been attempted.

The Individual in Focus

Within the strategy workshop, the individual’s strategizing actions, such as sensemaking, ideating, proposing, negotiating, supporting (or lack thereof), and personal behavior and personality type and traits have an effect on the organization’s selected strategies. One may assume an individual’s willingness and openness is at the core of actual constructive participation in the strategy workshop; the strategist’s predisposition and assertiveness are only among other factors. Certainly, the way in which individuals can sell their proposals across and up in the firm through specific traits, behaviors, and skills, especially communication skills, is important. However, other actions by the individual that emerge in strategy workshops may be conclusive. Preparing for the workshop, sharing ideas, and building rapport with others before making proposals and supporting others in their onstage performances and execution may be more important than any one individual’s specific (often inherent) traits. Middle managers who focus on selected items for which they then prepare themselves and others in a strategy workshop setting have an opportunity to see results stem from their associated strategizing actions.

Discussion

Consistency of Results With the Existing Literature

Our results are not only consistent with the literature on strategy workshops but also specify and center them with more detailed information on how different practitioners may react in a specific contextual workshop setting. This study focused on strategy workshops within a global firm, and our results partly confirm Hodgkinson et al.’s (2006) conclusions based on declared experiences of managers who participated in strategy workshops in U.S. firms over a decade ago. Thus, by observing these strategy workshops, we can confirm both top and middle managers can adopt a more discursive rather than analytical or factual approach to strategy formulation. This is more the enrichment of a proposal rather than any new proposal development per se. (Facts are almost never the basis for elaborating any new advanced proposal.)

We also show middle managers seem to make sense of proposals top managers have elaborated elsewhere, but not within this workshop. In this vein, we partly confirm Hodgkinson et al.’s (2006) findings, which argued middle managers are excluded from the real process of strategy formulation because it takes place outside the strategy workshop. More specifically, we demonstrate what an elitist approach to strategy development means by focusing on strategy formulation—not strategy development. We also show middle managers who actually take part in the process are those who have the codes, the experience, and, in some respects, the recognized legitimacy to strategize by top managers (Schuman, 1995).

Our work is consistent with more recent research results such as those of Jarzabkowski and Seidl (2008) and Johnson et al. (2010) who explained the workshop’s structure influences the strategy debate. However, we go further and also argue the moderator plays a role by influencing debates, or letting them go, and is often manipulated by top management.

We can discuss our results and their contribution to the existing literature by questioning the determinist approach of who can (and cannot) successfully participate in strategy workshops as if personal identity-related traits is the main factor for idea adoption during strategy workshops. Moreover, we can discuss our results for other identity-related traits, such as self-efficacy perception of knowledge on rituals or even leadership, and then on the topic of strategy workshops as the arena for strategy work and participation therein.

A Typology of Best Personality Traits for Having One’s Ideas Adopted?

The typology of the profiles of middle managers whose propositions are accepted, or not, suggests depending on their identity (e.g., national culture, age, size, and gender) and how this relates to and fits the firm’s predisposition, not every middle manager’s ideas will be accepted by the group during the strategy workshop. The most recent literature on strategy as practice focuses on not only the organizational identity concept (Li, Jarzabkowski, & Furnari, 2018; Ravasi, Tripsas, & Langley, 2020) but also individual identity (Basque, Rouleau, & Meziani, 2018). Regarding individual identity, our results are partly consistent with Basque et al. (2018) who stated the new boss’s identity facilitates other organizational members’ new discourse development and, therefore, a new positioning for actions. In our case, we note, depending on the workshop session’s participants, some middle managers might develop specific discourses. However, we find our first results and the work of Ravasi et al. (2020) tend to reveal the existence of a strategy/identity nexus. Therefore, depending on who you are (your identity and personality traits) and your strategizing process, your discourse would differ in not only its form but also its content.

Participation in Strategy Workshops: Self-Efficacy and Knowledge of Rituals or Individuals and Power Relationships?

One other interpretation of our typology and results would support a learning-anchored approach. Our results revealed, in practice, not every invited middle manager participates in the strategy workshop and in formulating proposals retained by the group or, moreover, by top managers who can ultimately upgrade the proposed strategy. Paradoxically, these results not only confirm but also contradict and expand existing work. Our case tends to not only confirm Hodgkinson et al.’s (2006) work because we also found not every middle manager, despite an invitation, indeed took part in the conversation and managed to have a proposal debated. However, our case does not reveal any sign of elitism, considering only those who are quite well-perceived by top management, maybe outside the workshop, participated. Here, elitism seems to refer more to the use of codes and ritual know-how and pertains to those who possess the self-confidence to talk and put forward appropriate proposals (Johnson et al., 2010). Considered like this, our results do not match Hodgkinson et al.’s (2006) conclusion because we consider such qualities are not personally intrinsic and can be learned. In some sense, our study’s finding that the female managers did not fully participate in the strategy workshop could be interpreted not as a sign of discrimination and sufferance from a sort of glass-ceiling effect coming from top managers or peers, but as an indication of a lack of self-esteem (Hackett & Betz, 1981).

Our data cannot reveal the power effects that could exist between actors because we only captured verbatim responses and thus cannot analyze them without a strong subjectivity (i.e., who is seeking what, who is an ally of whom, etc.). However, this is a profile, or portrait, of the middle manager who takes part in the practice and the strategy formulation process in the context of the strategy workshop. The intended goal may be of buy-in and support to reflect the main intent of the workshop studied in this paper; however, conflicts occur when participants think they are present for ideation and bottom-up conceptual proposal creation and elaboration and not merely buy-in. A match between the strategy workshop’s intent and the range of invitees’ expectations is therefore sought. Therefore, the workshop structure and the array of invitees may thus inadvertently bring about non-neutral effects. As a result, workshops may reflect and affect the organizational power arrangements. Why certain practitioners, but not others, were involved; how moderators and presenters were selected; how the workshop program structure was decided; and how time and significance was allocated and distributed among the interventions and diverse participants’ discourses may be questioned. We may even ask whether a newbie in a hierarchically structured organization can be a strategist.

In this larger sense, our results confirm Johnson et al.’s (2010) research. Our case deals with a strategy workshop with the objective of conducting a strategy of change, and the moderator was requested to play a neutral role. Now, the question is: if we had changed the role of the moderator, would our results differ? According to Johnson et al., the reply should be yes. If we adopt SAP’s widely used approach, power is at the core of the strategizing process, and what happens in the workshop should also be a matter of power between actors. If the moderator is encouraged to interrupt middle managers who speak too long or to put forward the moderator’s own personal proposals, the power relationship should change.

Contribution, Limitations, and Further Research

By defining a typology of middle-manager profiles and having associated some specific strategizing micro-practices to their personas, we argue our research partly fulfills the research gap on strategy workshop participation. We claim our typology proposes an interesting answer to the question, why do some strategy workshops not lead to radically new proposals. The answer relies not only on who gets invited-elites or middle managers-but also on the identity and personality attributes of those invited.

This research does suffer from several limitations. The most important one is the study is based on a single ethnographic case. The case we analyzed refers to a singular firm with a strong hierarchical structure and an international culture. Therefore, the limitation relies on the capacity to generalize the case (Eisenhardt & Gräbner, 2007; Langley, 1999). A second limitation is our typology is mostly based on analyzing audio recordings; therefore, it relies solely on the voices, tones, and discourses, and it does not integrate other forms of expression, such as movement.

Beyond these limitations, we argue our research suggests some further directions. Directly related to the just-mentioned limitations, the practice of micro-strategizing in strategy workshops could be analyzed with a focus on personality traits’ effects not only on discourses but also on moves and presence onstage. Second, we call for more studies on the construct of the strategy/identity nexus during strategy workshops by analyzing how participants adopt their own strategic positionings when facing or interacting with their colleagues while formulating strategic propositions. Last, we should also consider capturing how middle managers from this same organization micro-strategize during other strategic workshops. This may lead to better capturing not only the limits of personal identity on micro-strategies but also the potential learning process for micro-strategizing.

Appendices

Biographical notes

Christine Sund is Senior Advisor at the International Telecommunication Union. She holds a Doctorate in Business Administration (DBA) from Grenoble École de Management, is a graduate of the Thunderbird School of Global Management (MBA) and Aalto University (School of Economics), her research focuses on the contribution of middle managers to strategizing in organizations, considering their identity but also to gender. She uses her research findings in her teachings grounded in the stream of Strategy-as-Practice.

Séverine Le Loarne Lemaire is a full professor at Grenoble Ecole de Management and holder of the “Women and Economic Renewal” Chair. Her research focuses on the role of gender, and more generally on the identity of the person, as a vehicle for legitimizing the ideas that this person brings to companies or within entrepreneurial ecosystems. She is the author of innovation manuals as well as numerous research articles published in peer-reviewed journals.

Bibliography

- Armenakis, A. A., & Harris, S. G. (2002). Crafting a change message to create transformational readiness. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 15, p. 169-83.

- Atkinson, P., & Hammersley, M. (1994). Ethnography and participant observation. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of Qualitative Research, 23, p. 248-261. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Ahearne, M., Lam, S. K., & Kraus, F. (2014). Performance impact of middle managers’ adaptive strategy implementation: The role of social capital. Strategic Management Journal, 35(1), p. 68-87.

- Anicich, E. M., & Hirsh, J. B. (2017). The psychology of middle power: Vertical code-switching, role conflict, and behavioral inhibition. Academy of Management Review, 42(4), p. 659-682.

- Balogun, J. (2003). From blaming the middle to harnessing its potential: Creating change intermediaries. British Journal of Management, 14(1), p. 69-83.

- Balogun, J., & Johnson, G. (2004). Organizational Restructuring and Middle Manager Sensemaking. Academy of Management Journal, 47(4), p. 523-549.

- Basque, J., Rouleau, L., & Meziani, N. (2018, July). Talking About the “New” Boss: Unpacking the Strategy-Identity Nexus Through Discursive Presences. In Academy of Management Proceedings (Vol. 2018, No 1, p. 15195). Briarcliff Manor, NY 10510: Academy of Management.

- Beech, N., & Johnson, P. (2005). Discourses of disrupted identities in the practice of strategic change: the mayor, the street-fighter and the insider-out. Journal of Organizational Change, 18(1), p. 31-47.

- Besson, P., & Mahieu, C. (2011). Strategizing from the middle in radical change situations: Transforming roles to enable strategic creativity. International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 19(3), p. 176-201.

- Bourque, N., & Johnson, G. (2008). Strategy Workshops and “Away Days” as Ritual, in: The Oxford Handbook of Organizational Decision Making. Oxford.

- Bowman, C. (1995). Strategy workshops and top-team commitment to strategic change. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 10(8), p. 4-12.

- Boyett, I., & Currie, G. (2004). Middle managers moulding international strategy: An Irish start-up in Jamaican telecoms. Long Range Planning, 37(1), p. 51-66.

- Burgelman, R. A. (1983). ‘A process model of internal corporate venturing in the diversified major firm’. Administrative Science Quarterly, 28, p. 223-44.

- Burgelman, R., Floyd, S. W., Laamanen, T., Mantere, S., Vaara, E., & Whittington, R. (2018). Strategy Processes and Practices: Dialogues and Intersections. Strategic Management Journal, p. 1-28.

- Chia, R. (2004). Strategy-as-practice: reflections on the research agenda. European Management Review, 1(1), p. 29-34.

- Chia, R., & Holt, R. (2006). Strategy as practical coping: A Heideggerian perspective. Organization studies, 27(5), p. 635-655.

- Clegg, S., & Kornberger, M. (2015). Analytical frames for studying power in strategy as practice and beyond. In D. Golsorkhi, L. Rouleau, D. Seidl, & E. Vaara (Eds.), The Cambridge Handbook on Strategy-as-Practice (pp. 389-404). Cambridge: UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Dopson, S., & Neumann, J. E. (1998). Uncertainty, Contrariness and the Double-bind: Middle Managers’ Reactions to Changing Contracts. British Journal of Management, 9(3), p. S53-S70.

- Duffy, M., & O’Rourke, B. K. (2015). Dialogue in strategy practice: A discourse analysis of a strategy workshop. International Journal of Business Communication, 52(4), p. 404-426.

- Dutton, J. E., Ashford, S. J., O’Neill, R. M., Hayes, E., & Wierba, E. E. (1997). Reading the wind: How middle managers assess the context for selling issues to top managers. Strategic Management Journal, 18(5), p. 407-423.

- Eisenhardt, K. M., & Gräbner, M. E. (2007). Theory building from cases: opportunities and challenges. Academy of Management Journal, 50(1), p. 25-32.

- Emerson, R. M., Fretz, R. I., & Shaw, L. L. (1995). Writing ethnographic fieldnotes. Chicago guides to writing, editing. and publishing. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Floyd, S. W., & Lane, P. J. (2000). Strategizing throughout the organization: Management role conflict in strategic renewal. Academy of Management Review, 25(1), p. 154-177.

- Floyd, S. W., & Wooldridge, B. (1997). Middle management’s strategic influence and organizational performance. Journal of Management Studies, 34(3), p. 465-485.

- Friesl, M., & Kwon, W. (2017). The strategic importance of top management resistance: Extending Alfred D. Chandler. Strategic Organization, 15(1), p. 100-112.

- Glaser, L., Stam, W., & Takeuchi, R. (2016). Managing the risks of proactivity: A multilevel study of initiative and performance in the middle management context. Academy of Management Journal, 59(4), p. 1339-1360.

- Goffman, E. (1959), The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life, Penguin Books, London.

- Golsorkhi, D., Rouleau, L., Seidl, D., & Vaara, E. (2015). Cambridge Handbook of Strategy as Practice, Second edition. Cambridge Handbook of Strategy as Practice, Second Edition, Cambridge University Press.

- Hackett, G., & Betz, N. E. (1981). A self-efficacy approach to the career development of women. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 18(3), p. 326-339.

- Hautz, J., Seidl, D., Whittington, R. (2017). Open Strategy: Dimensions, Dilemmas, Dynamics. Long Range Planning, 50(3), p. 298-309.

- Healey, M. P., Hodgkinson, G. P., Whittington, R., & Johnson, G. (2015). Off to Plan or Out to Lunch? Relationships between Design Characteristics and Outcomes of Strategy Workshops. British Journal of Management, 26(3), p. 507-528.

- Hendry, J., & Seidl, D. (2003). The structure and significance of strategic episodes: Social systems theory and the routine practices of strategic change. Journal of Management Studies, 40(1), p. 175-196.

- Heyden, M. L. M., Fourné, S. P. L., Koene, B. A. S., Werkman, R., & Ansari, S. S. (2017). Rethinking ‘Top-Down’ and ‘Bottom-Up’ Roles of Top and Middle Managers in Organizational Change: Implications for Employee Support. Journal of Management Studies, 54(7), p. 961-985.

- Hodgkinson, G. P., & Wright, G. (2002). Confronting strategic inertia in a top management team: Learning from failure. Organization studies, 23(6), p. 949-977.

- Hodgkinson, G. P., Whittington, R., Johnson, G., & Schwarz, M. (2006). The role of strategy workshops in strategy development processes: Formality, communication, co-ordination and inclusion. Long Range Planning, 39(5), p. 479-496.

- Hoon, C. (2007). Committees as strategic practice: The role of strategic conversation in a public administration. Human Relations, 60(6), p. 921-952.

- Jarzabkowski, P. (2008). Shaping strategy as a structuration process. Academy of Management Journal, 51(4), p. 621-650.

- Jarzabkowski, P., Balogun, J., & Seidl, D. (2007). Strategizing: The challenges of a practice perspective. Human Relations, 60(1), p. 5-27.

- Jarzabkowski, P., Burke, G., & Spee, P. (2015). Constructing Spaces for Strategic Work: A Multimodal Perspective. British Journal of Management, 26(S1), p. S26-S47.

- Jarzabkowski, P., Kaplan, S., Seidl, D., & Whittington, R. (2015). On the risk of studying practices in isolation: Linking what, who, and how in strategy research. Strategic Organization, 14(3), p. 248-259.

- Jarzabkowski, P., & Lê, J. K. (2015). We have to do this and that? You must be joking: Constructing and responding to paradox through humour. Organization Studies, 38(3-4), p. 433-462.

- Jarzabkowski, P., & Seidl, D. (2008). The Role of Meetings in the Social Practice of Strategy. Organization Studies, 29(11), p. 1391-1426.

- Johnson, G., Langley, A., Melin, L., & Whittington, R. (2007). Strategy as practice: research directions and resources. Cambridge University Press.

- Johnson, G., Prashantham, S., Floyd, S. W., & Bourque, N. (2010). The Ritualization of Strategy Workshops. Organization Studies, 31(12), p. 1589-1618.

- Kanter, R. M. (1986). The reshaping of middle management. Management Review, January, p. 19-20.

- Kaplan, S. (2011). Strategy and PowerPoint: An inquiry into the epistemic culture and machinery of strategy making. Organization Science, 22(2), p. 320-346.

- Kerseens-van Drongelen, I. K. (2001). The iterative theory-building process: rationale, principles and evaluation. Management Decision, 39(7), p. 503-512.

- Knight, F. H. 1965. Risk, Uncertainty and Profit (Reprint) Harper & Row. New York, NY.

- Knights, D., & Morgan, G. (1991). Corporate Strategy, Organizations, Subjectivity: A Critique. Organisation Studies, 12(2), p. 251-273.

- Kryger, A. (2018). Iterative prototyping of strategy implementation workshop design. Journal of Strategy and Management, 11(2), p. 166-183.

- Laine, P.-M., & Vaara, E. (2015). Participation in strategy work. In D. Golsorkhi, L. Rouleau, D. Seidl, & E. Vaara (Eds.), Cambridge handbook of strategy as practice (2nd ed., p. 616-631). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press

- Langley, A. (1999). Strategies for theorizing from process data. The Academy of Management Review, 24(4), p. 691-710.

- Langley, A. (2007). Process thinking in strategic organization. Strategic Organization, 5(3), p. 271-282.

- Langley, A., & Abdallah, C. (2016). Templates and turns in qualitative studies of strategy and management. In Research methods for strategic management (p. 155-184). Routledge.

- Li, Q., Jarzabkowski, P., & Furnari, S. (2018). Strategy-as-Practice, Identity, and Capability to Perform in a Pluralist Context: A Case Study. In Academy of Management Proceedings (Vol. 2018, No 1, p. 12061).

- MacIntosh, R., & Beech, N. (2011). Strategy, strategists and fantasy: a dialogic constructionist perspective. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 24(1), p. 15-37.

- MacIntosh, R., MacLean, D., & Seidl, D. (2010). Unpacking the effectivity paradox of strategy workshops: do strategy workshops produce strategic change? In: Golsorkhi, D; Rouleau, L; Seidl, D; Vaara, E. Cambridge Handbook of Strategy as Practice. Cambridge, p. 291-307.

- MacKay, R.B., Chia, R., & Nair, A. (2020) Strategy-in-practices: a process philosophical approach to understanding strategy emergence and organizational outcomes. Human Relations.

- Mantere, S. (2005). Strategic practices as enablers and disablers of championing activity. Strategic Organization, 3(2), p. 157-184.

- Mantere, S. (2008). Role expectations and middle manager strategic agency. Journal of Management Studies, 45(2), p. 294-316.

- Mantere, S., & Vaara, E. (2008). On the Problem of Participation in Strategy: A Critical Discursive Perspective. Organization Science, 19(2), p. 341-358.

- Mezias, J., Grinyer, P., & Guth, W. D. (2001). Changing collective cognition: a process model for strategic change. Long Range Planning, 34(1), p. 71-95.

- Mintzberg, H., & Waters, J. A. (1985). Of Strategies, Deliberate and Emergent. Strategic Management Journal, 6(3), p. 257-272.

- Nicolini, D., & Monteiro, P. (2016). The Practice Approach: For a Praxeology of Organisational and Management Studies. In The SAGE Handbook of Process Organization Studies (p. 1-27).

- Oakes, L., Townley, B. and Cooper, D. (1998). Business planning as pedagogy: language and control in a changing institutional field, Administrative Science Quarterly, 43, 2: p. 257-92).

- O’Reilly, K., 2005. Ethnographic Methods. London: Routledge.

- Pitsis, T. S., Kornberger, M., & Clegg, S. (2004). The art of managing relationships in interorganizational collaboration. Management, 7(3), p. 47-67.

- Raes, A. M., Heijltjes, M. G., Glunk, U., & Roe, R. A. (2011). The interface of the top management team and middle managers: A process model. Academy of Management Review, 36(1), p. 102-126.

- Rasche, A., & Chia, R. (2009). Researching strategy practices: A genealogical social theory perspective. Organization Studies, 30(7), p. 713-734.

- Ravasi, D., Tripsas, M., & Langley, A. (2020). Exploring the strategy-identity nexus. Strategic Organization, 18(1), p. 5-19.

- Rouleau, L. (2005). Micro-practices of strategic sensemaking and sensegiving: How middle managers interpret and sell change every day. Journal of Management Studies, 42(7), p. 1413-1441.

- Rouleau, L., & Balogun, J. (2011). Middle managers, strategic sensemaking, and discursive competence. Journal of Management Studies, 48(5), p. 953-983.

Appendices

Notes biographiques

Christine Sund est conseillère principale chez Union Internationale des Télécommunications. Titulaire d’un Doctorat d’Administration des Entreprises (DBA) obtenu à Grenoble École de Management, diplômée de la Thunderbird School of Global Management (MBA) et de l’université d’Aalto, ses recherches portent sur la contribution des cadres intermédiaires à la formation de la stratégie des grands groupes, en fonction de leur identité, mais aussi de leur genre. Elle utilise ses résultats de recherche dans son enseignement, fondé sur le courant de la stratégie en pratique.

Séverine Le Loarne Lemaire est professeur senior à Grenoble École de Management et titulaire de la Chaire « Femmes et Renouveau Economique ». Sa recherche porte sur le rôle du genre, et plus généralement de l’identité de la personne, en tant que vecteur de légitimation des idées que cette personne porte dans les entreprises ou dans les écosytèmes entrepreneuriaux. Elle est autrice de manuels d’innovation, mais aussi de nombreux articles de recherche publiés dans des revues à comité de lecture.

Appendices

Notas biograficas

Christine Sund es asesora principal de la Unión Internacional de Telecomunicaciones. Tiene un Doctorado en Administración de Empresas (DBA) de Grenoble École de Management, es egresada de Thunderbird School of Global Management (MBA) y Aalto University (School of Economics), su investigación se centra en la contribución de los mandos medios a la elaboración de estrategias en las organizaciones, mirando su identidad pero también su género. Ella usa los hallazgos de su investigación en su aenseñanza basada en la corriente de la estrategia como práctica.

Séverine Le Loarne Lemaire es profesora titular en Grenoble Ecole de Management y titular de la cátedra “Mujer y renovación económica”. Su investigación se centra en el papel del género, y más en general de la identidad de la persona, como vehículo para legitimar las ideas que esta persona lleva en las empresas o en los ecosistemas emprendedores. Es autora de manuales de innovación y de numerosos artículos de investigación publicados en revistas revisadas por pares.

List of figures

Figure 1

Strategy actors involved in strategy workshops: their positions, and actions

List of tables

Table 1

Linking the Type of Proposal for an Outcome from a Strategy Workshop to the Middle Manager Strategists’ Identities as Proposal Originators through Generalized Profiles (with detailed descriptions)

Table 2

Generalized Profiles of Strategy Workshop Practitioners

Table 3

Nature of Proposals and their Occurrences in the Strategy Workshop Sessions