Abstracts

Summary

A number of empirical studies from the early 1970s to the mid-1990s indicated that delay in Canadian grievance arbitration was becoming an increasing problem. There have been no further scientific studies on delay since then, despite developments that may exacerbate the issue like increased legalism and expanded arbitral jurisdiction. Academics and practitioners have recently voiced renewed concerns about the threat that delay poses to the viability of the grievance arbitration system.

To address this gap in the scientific literature, the present study examines delay and its determinants in Ontario over the last two decades. Content analysis was conducted on a random sample of almost 400 Ontario grievance arbitrations from three reference years (1994, 2004, and 2012). I then performed event history analysis on the data to determine the various factors that were associated with delay. Consistent with common perception, my empirical results suggest that delay has become worse over the past two decades. I find that certain legalistic factors are indeed associated with delay, including the use of lawyers, the use of preliminary objections, the number of witnesses testifying, and attacks on credibility. In terms of expanded arbitral jurisdiction, I find that while delay has increased for grievances involving alleged Employment Standards Act violations, for all other non-traditional issues (including human rights complaints) there are no significant increases. The results also show that certain dispute resolution procedures, such as expedited arbitration and the use of sole arbitrators are related to shorter grievance durations, and this, combined with the other findings, suggests practical solutions to the issue of delay. However, the findings also suggest that the use of certain procedures involving additional steps, like settlement and mediation-arbitration, can also serve to increase grievance duration when used unsuccessfully.

Keywords:

- grievance duration,

- determinants,

- legalism,

- dispute resolution procedures,

- empirical analysis

Résumé

Du début des années 1970 jusqu’au milieu des années 1990, plusieurs études empiriques ont mis en exergue un problème croissant de délais dans l’arbitrage de griefs au Canada. Pourtant, depuis, peu de nouvelles études scientifiques ont été menées sur cette problématique, malgré certains développements survenus susceptibles d’exacerber le problème, tels que l’élargissement de la compétence arbitrale et une judiciarisation accrue du processus. Chercheurs et praticiens ont récemment réitéré leurs inquiétudes face à la menace posée par de tels délais sur la viabilité du système d’arbitrage des griefs.

Pour combler cette lacune dans le débat scientifique, la présente étude examine les délais et leurs déterminants en Ontario au cours des vingt dernières années. Une analyse de contenu portant sur trois années de référence (1994, 2004 et 2012) a été menée auprès d’un échantillon aléatoire de près de 400 arbitrages des griefs tenus en Ontario en appliquant l’analyse de données événementielles afin de déterminer quels facteurs peuvent être associés à ces délais. En conformité avec l’opinion communément admise, les résultats empiriques suggèrent un net accroissement des délais au fil des vingt dernières années. En effet, nous démontrons que des facteurs de judiciarisation sont associés à la hausse des délais, comme le recours à des avocats, l’utilisation des objections préliminaires, l’augmentation du nombre de témoins assignés, ainsi que la mise en cause fréquente de leur crédibilité. En ce qui concerne l’étendue accrue de la compétence arbitrale, si nous observons bien une hausse des délais pour les arbitrages relatifs aux violations de la Loi sur les normes du travail de l’Ontario, il n’y a cependant pas d’augmentation significative en ce qui concerne les autres matières non traditionnelles (incluant les plaintes relatives aux droits de la personne). Les résultats démontrent aussi que certaines procédures de règlement des différends, comme l’arbitrage accéléré ou le recours à un arbitre unique, sont associées à de plus courts délais, une observation qui, combinée à nos autres résultats, permet d’entrevoir des solutions pratiques au problème des délais trop longs. Toutefois, nos résultats indiquent également que l’ajout d’étapes aux procédures existantes, tels les règlements hors cour et la médiation-arbitrage, peuvent prolonger la durée du traitement des griefs lorsqu’utilisées sans résultat.

Mots-clés:

- grief,

- durée de l’arbitrage,

- déterminants,

- judiciarisation,

- procédure de règlement,

- analyse empirique

Resumen

Desde los años 1970 hasta mediados de los años 1990, numerosos estudios empíricos habían puesto en evidencia el problema creciente de la demora en el arbitraje de reclamos en Canadá. Desde entonces, no ha habido más estudios científicos sobre el sujeto, a pesar que dicha demora puede ser exacerbada por el aumento del legalismo y la ampliación de la jurisdicción arbitral. Recientemente, investigadores y profesionales han expresado sus preocupaciones sobre la amenaza que representa el retraso para la viabilidad del sistema de arbitraje de reclamos.

Para abordar esta laguna en la literatura científica, el presente estudio examina la demora y sus determinantes en Ontario en la últimas dos décadas. El estudio fue realizado con una muestra de aproximativamente 400 reclamaciones en Ontario del total de reclamaciones de tres años de referencia (1994, 2004 y 2012). Dichos datos fueron el objeto de un análisis de supervivencia a fin de determinar los diversos factores asociados con la demora. De acuerdo con la percepción común, los resultados empíricos sugieren que la demora ha empeorado en las últimas dos décadas. Se observó que ciertos factores legalistas son efectivamente asociados con la demora, incluyendo el uso de abogados, el uso de objeciones preliminares, el número de testigos que testifican y los ataques a la credibilidad. Respecto a la ampliación de la jurisdicción arbitral, se observó que la demora aumentaba en los casos de reclamos implicando violaciones a la ley de normas laborales (Employment Standards Act) mientras que por los otros reclamos no tradicionales (incluyendo las quejas por derechos humanos) no se constata aumento de demoras. Los resultados muestran tambien que ciertos procedemientos de resolución de litigio, como el arbitraje acelerado y el uso de árbitros únicos, están relacionados con duraciones mas cortas. Esto, combinado con los otros resultados, sugiere soluciones prácticas al problema de la demora. Sin embargo, los resultados sugieren también que el uso de ciertos procedimientos que implican etapas adicionales, como el acuerdo y la mediación-arbitraje, pueden también conducir al aumento de la duración del trámite del reclamo cuando sus resultados son infructuosos.

Palabras claves:

- reclamo laboral,

- duración del arbitraje de reclamos,

- determinantes,

- legalismo,

- procedimiento de resolución de litigios,

- análisis empíricos

Article body

My thesis is that labour arbitration as we know it, that institution that we are all so dependent on in the field of labour relations, has lost its course, has lost its trajectory, has lost its vision. It is at risk of becoming dysfunctional and irrelevant.

Warren Winkler (2010: para. 2), then Chief Justice of Ontario

Introduction

Grievance arbitration is a cornerstone of the Canadian labour relations system (Winkler, 2011). All collective agreements must have a clause requiring the arbitration of unresolved grievances (Rose, 1986).[1] Grievance arbitration is an important “voice” mechanism for unionized workers, allowing them to challenge management practices they view to be unjust (Freeman and Medoff, 1984; Budd and Colvin, 2008). It is supposed to be a quicker, less expensive, and less legalistic way to provide labour justice than the court system (Thornicroft, 2009). Despite this, there is evidence that delay in Canadian grievance arbitration increased at an alarming rate from the early 1970s to the mid-1990s.

The literature has identified at least six reasons why grievance delay might be a problem. First, delay might actually impact the result of the case. For instance, Adams (1978) found that the likelihood of the grievor being reinstated in dismissal cases decreased with the passage of time. Second, certain remedies may become moot (e.g., reinstatement might be a hollow victory if the grievor has already found another job) (Thornicroft, 1993). Third, delay is potentially harmful to labour relations: unresolved grievances cause uncertainty and tension for management and workers (Lewin, 1999; Ross, 1958) and can lead to festering conflict that is funnelled into other areas of the labour relations system, with harmful consequences such as dysfunctional labour negotiations (Ponak, Zerbe, Rose, and Olson, 1996) and increased strikes (Hebdon and Noh, 2013). Fourth, the liability of the employer increases with time (Sloane and Whitney, 1985). Fifth, the availability of evidence fades (Prasow and Peters, 1983). Sixth, delay is associated with increased costs (Ponak and Olson, 1992; Thornicroft, 2009).

In the first half of the 1990s, two sets of researchers used advanced statistical techniques to examine the causes of delay in Canadian grievance arbitration: Thornicroft; and Ponak and Olson (Thornicroft, 1993, 1994, and 1995; Ponak and Olson, 1992; Ponak et al., 1996). Since these studies, there has been no further attempt to scientifically study the issue of delay and its causes in Canada, despite mounting anecdotal evidence that the problem of delay has continued to become worse since then and despite legal developments that are thought to exacerbate delay.

To address this gap in the scientific literature, the present study examines delay and its determinants in Ontario from 1994 to the present. By reviewing previous research and legal developments, I develop a series of testable hypotheses. These hypotheses are tested by coding approximately 400 Ontario arbitration awards, and then performing event history analysis on the data.

Previous Research, Legal Developments, and Hypotheses

Delay

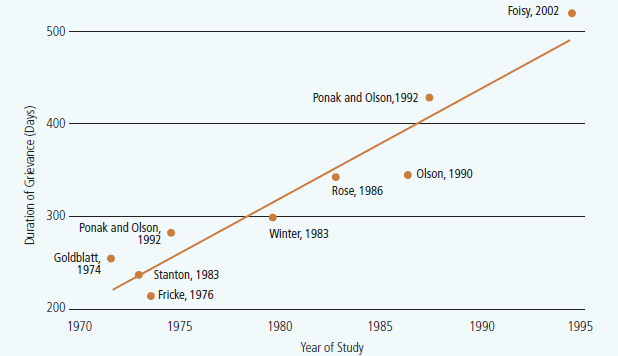

There is abundant evidence from the Canadian literature that delay is becoming a worse problem with time. In previous studies, grievance duration was measured from the filing of the grievance (the grievance date) until the time an arbitration award was released to the parties. The average duration grew from being around 250 days in the early 1970s to being more than 500 days by the mid-1990s. The results of these studies are summarized in Figure 1, which plots the duration by the year, along with the line of best fit. This graph clearly shows the troubling upward trend over time in the duration of grievance arbitration. The slope of the line suggests an annualized increase of 11.89 days in grievance duration, which amounts to an increase of 118.9 days over a decade.

Figure 1

Results of previous studies, average total duration of grievance by year of study

Notes: Studies plotted by year of data, not year of publication. Where a study covered multiple years, the mid-point was taken. Line of best fit also shown. Slope of line is 11.89 days per year.

It is reasonable to expect that this trend has continued. On this basis, the following hypothesis can be advanced for the present study:

Hypothesis 1 (H1): Grievance arbitration disposition times have continued to increase over the last two decades.

Determinants of Delay

The previous studies unambiguously indicate that delay has increased. The question then becomes why delay is going up—what are its determinants? Possible determinants can be categorized under three different constructs: legalism, expanded jurisdiction, and procedure.

Legalism

Over the years, many authors have argued that the positive aspects of the grievance arbitration system are eroding, in large part due to something that has evocatively been described as “creeping legalism” (Rubin and Rubin, 2003; Weiler, 1980). “Legalism” is the emphasis of procedural rules and legal principles over considerations that would foster the parties’ long-term relationship. A number of different indicia of legalism have been put forward by both labour relations researchers and legal scholars, but only some have been scientifically investigated. Where they have been studied, empirical researchers have generally divided the grievance period into pre-hearing and posting-hearing phases, as well as examining total disposition time. These researchers have found different effects for the different phases, thus highlighting the need to study the different phases, in addition to total disposition time (an approach I have adopted for the present study). However, for the sake of simplicity, only previous findings on total disposition time will be summarized here.

Not surprisingly, some researchers have hypothesized that the presence of lawyers is a legalism variable that causes delay in grievance arbitration. Lawyers are trained to make complicated and technical legal arguments with a view to helping their clients win the case. Thornicroft found that legal representation was positively related to total disposition time (1993, 1994, and 1995), while Ponak and colleagues (1996) did not find an association.

Another “legalism” variable that might cause delay is the use of preliminary objections. Preliminary objections are raised by one of the parties at the beginning of the arbitration hearing, and typically relate to the arbitrator’s jurisdiction to hear the case (Winkler, 2010 and 2011; Thornicroft, 2009). Ponak et al. (1996) did not find that they had a significant effect on total duration time.

Length of the arbitration award has also been studied by Ponak et al. (1996) as a “legalistic” determinant of delay. Their rationale was that arbitrators must write longer decisions the more complicated and technical a case is. Curiously, these researchers found that award length had no impact on total duration of the arbitration.

There have been a number of other legalistic factors that have been posited by some legal scholars as being causes of delay in arbitration, but these have not yet been subject to scientific investigation. Justice Winkler (2011) has observed a culture change in grievance arbitration from being industrial relations-based to being litigation-based. According to him, there is now an increased focus on due process and legal rules, rather than on an outcome that makes labour relations sense. Specific indicia cited by Justice Winkler are as follows: evidentiary disputes, estoppel arguments, number of cases cited in an award, the number of witnesses called, the use of expert testimony, the use of legal briefs/written submissions, credibility challenges, and the number of arbitral awards necessary to resolve a given grievance.

Given this evidence and commentary, the following hypothesis is reasonable for the current study:

Hypothesis 2 (H2): Legalism is associated with increased disposition time of grievances.

H2 measures the direct effect of legalism on arbitration delay, without predicting whether the impact is changing with the passage of decades (in other words, it does not postulate whether there is an interaction effect between legalism and decade). According to Justice Winkler (2010; 2011), the delays caused by the culture of legalism appear to be getting worse with time. The present study will therefore also test the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3 (H3): Year is moderating the association of legalism and disposition time, such that a given level of legalism is producing longer disposition times in later decades.

Expanded Jurisdiction

In addition to the issue of creeping legalism, many court cases decided in the past two decades have expanded the jurisdiction of labour arbitrators, and this might also be a cause of delay. Traditionally, the jurisdiction of the arbitrator has been derived from applicable labour legislation and from the collective agreement itself. Historically, legal issues that did not arise out of the collective agreement were often litigated in the courts, or before tribunals. In 1995, the Supreme Court of Canada decided Weber v. Ontario Hydro and rejected the prevailing notion that arbitrators and the Courts had concurrent jurisdiction over certain private law and constitutional matters, in favour of a model of “exclusive jurisdiction” for arbitrators. In 2003, the Supreme Court further held that an alleged violation of the Human Rights Code constitutes an alleged violation of the collective agreement (even in the absence of specific language in the collective agreement referencing the Human Rights Code), and a grievance arbitrator has jurisdiction to enforce rights under the Code (Parry Sound v. OPSEU). As a result of the Parry Sound decision, arbitrators have jurisdiction to enforce not only the Code, but also other important employment-related statutes such as the Employment Standards Act, the Occupational Health and Safety Act, and privacy legislation. Lastly, an Ontario Court of Appeal decision in 2006 emphasized the broad range of remedies that an arbitrator has jurisdiction to award. In OPSEU v. Seneca College (2006), the court ruled that an arbitrator has jurisdiction to determine whether he or she can award aggravated and punitive damages from torts, which go beyond the typical compensatory damages that arbitrators have traditionally ordered.

To summarize, legal commentators have credibly argued that court decisions expanding the jurisdiction of arbitrators will increase the complexity of arbitrations and lead to delay in the system (Nadeau, 2012). On this basis, I expect the following:

Hypothesis 4 (H4): The expanded jurisdiction of arbitrators is associated with increased disposition time of grievances.

Moreover, there may be a lag effect of the expanded jurisdiction, such that it might take some time before the parties feel comfortable arbitrating issues that were formerly litigated in the courts or before tribunals. On this basis, I predict the following interaction effect:

Hypothesis 5 (H5): Year is moderating the association of expanded jurisdiction and disposition time, such that this broader jurisdiction is producing longer disposition times with each passing decade.

Procedure

Although there are factors such as creeping legalism and expanded jurisdiction that appear to be increasing delay in grievance arbitration, procedures the parties can use may be working in the opposite direction. One of these procedures is statutory expedited arbitration, which the parties can access under the Ontario Labour Relations Act. Within 30 days after the grievance has been filed, one of the parties can unilaterally request that the Ministry of Labour appoint a sole arbitrator. This arbitrator must commence the hearing within 21 days. Rose (1986) conducted a study of this procedure in Ontario. In his study, Rose compared the unadjusted means of grievance duration for the approximately 5,500 Ontario grievances between 1979 and 1985. He found a statistically significant difference in the mean duration: 119 days for expedited grievances versus 342 days for non-expedited grievances.

Quite apart from statutory expedited arbitration, the parties can themselves agree to take steps to expedite the arbitration. Such steps might include a relaxing of the legal rules of evidence during a hearing, an elimination of the need for a written award, or an agreement that neither side will be represented by legal counsel (Dassios, 2010; Kauffman, 1992). There have been no scientific studies to date on the impact of such agreed expedited arbitration on grievance duration.

In addition to expedited arbitration, parties can choose whether to have the grievance arbitrated by a sole arbitrator, rather than by the more traditional three-person panel. Grievances decided by a sole arbitrator are expected to be faster, because it is much easier to coordinate schedules with one busy person, rather than three, and because a dissenting opinion from one of the nominees will slow down the release of the award (Ponak et al., 1996). The scientific studies do suggest that grievance durations are faster with sole arbitrators: Ponak et al. (1996) and Thornicroft (1993).

There is also some evidence that the procedure of mediation-arbitration (med-arb) is becoming increasingly popular as a means of combating delay (Picher, 2012; Whitaker, 2009). Med-arb is a procedure whereby the appointed arbitrator tries, with the parties’ agreement, to mediate the dispute (i.e., assist the parties voluntarily reach resolution) before proceeding to the more formal arbitration phase where a resolution will be imposed on the parties. If the parties are able to negotiate a resolution to their dispute with the assistance of the arbitrator, this will obviate the need for an arbitral hearing and a decision with lengthy reasons (Bartel, 1991; Whitaker, 2009). There have been no empirical studies on the efficacy of med-arb in combating the issue of delay.

On the basis of this empirical evidence and academic commentary, the following hypothesis was formulated for this study:

Hypothesis 6 (H6): Certain dispute resolution procedures used by the parties are associated with decreased disposition time of grievances.

It is predicted that these variables will be associated with faster dispute resolution times. However, it is important to be aware that there are counterveiling forces at work with some of these procedures. For example, mediation-arbitration does add the mediation step, which might serve to lengthen disposition times.

A related hypothesis is that there is a learning effect with these dispute resolution procedures, such that the participants in the arbitration system are getting better at utilizing them over time. On this basis, the following result is expected:

Hypothesis 7 (H7): Year is moderating the association of dispute resolution procedures and disposition time, such that a given procedure is producing shorter disposition times with each passing decade.

Research Design

Content Analysis

For this study, a technique called “content analysis” was used to generate data from written arbitration awards. Content analysis is an approach to the analysis of documents and texts that seeks to quantify content in terms of predetermined categories and in a systematic and replicable manner (Bryman, 2008). Content analysis has been used in many different contexts (Krippendorff, 2013), including in the studies of Ponak and Olson (1992), Ponak et al. (1996) and Thornicroft (1993, 1994, and 1995), discussed above.

The arbitration awards in my study were content analyzed by two coders. A number of recommended steps were taken to maximize inter-rater reliability, including the creation of a codebook, training for the coders, and a pilot phase on a sub-sample of 30 cases followed by codebook revisions and more training (Krippendorff, 2013; Neuendorf, 2002). The literature suggests that an inter-rater reliability of at least .85 is desirable (Neuendorf, 2002). For this study, this threshold was met for every variable, on a sample of 100 cases coded by both coders.

Data

To test the hypotheses, the present study was conducted using Ontario arbitration awards from 1994, 2004, and 2012. The year 1994 was chosen because it preceded the Weber (1995) decision, and because it also coincided roughly with when the last statistical studies on arbitral delay were conducted. The year 2004 was selected because it followed the Parry Sound (2003) decision, and because it was a decade after the original reference year. The year 2012 was chosen because it is the most recent one for which data were available. The three years were also chosen because Ontario’s economy was experiencing positive growth in these periods. One might expect different patterns of grievance activity during recessionary times (Bacharach and Bamberger, 2004; Cappelli and Chauvin, 1991).

The unit of analysis was a grievance. A sampling frame was compiled of all relevant grievances in each of the three reference years. In order for a grievance to be included in the study, it had to end in an arbitration award that was released in the reference year. Some grievances have more than one arbitration award, and these grievances were included only if the last arbitration award was released in the reference year. Arbitration awards were obtained from three legal databases: Quicklaw, Labour Spectrum, and CanLII. A sampling frame needed to be compiled from all three databases, because many awards were not common across databases.

There were 1,153 eligible grievances in the year 1994: 803 from 2004, and 753 for 2012. After the sampling frame was compiled, a random sample of 15% of grievances was obtained from each reference year. Nine grievances with total disposition times more than three standard deviations from the mean were dropped, after statistical analysis suggested it was appropriate to do so.[2] This yielded a total of 397 observations: 172 from the year 1994; 120 from 2004; and 105 from 2012.

Time and Explanatory Variables

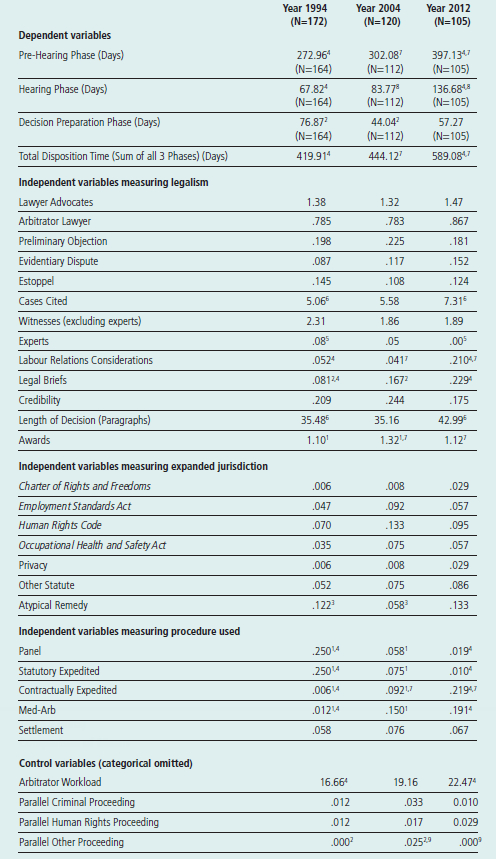

The dependent variable is the hazard rate, based on time. Because previous studies found different effects for different phases, time in this study was measured in three consecutive phases, plus a total of the phases. The phases were pre-hearing, hearing, and decision preparation. The length of these phases, each measured in number of elapsed calendar days, was generated using information from the arbitration award. Summary statistics of the various phases are provided in Table 1, and a comparison of means among each of the reference years is provided in Table 2.

Table 1

Descriptive Statistics

Table 2

Comparison of Means

1 Significant Difference Between Means for 1994 and 2004 (.01 level)

2 Significant Difference Between Means for 1994 and 2004 (.05 level)

3 Significant Difference Between Means for 1994 and 2004 (.10 level)

4 Significant Difference Between Means for 1994 and 2012 (.01 level)

5 Significant Difference Between Means for 1994 and 2012 (.05 level)

6 Significant Difference Between Means for 1994 and 2012 (.10 level)

7 Significant Difference Between Means for 2004 and 2012 (.01 level)

8 Significant Difference Between Means for 2004 and 2012 (.05 level)

9 Significant Difference Between Means for 2004 and 2012 (.10 level)

Means were compared using the Student-Newman-Keuls (SNK) test.

The explanatory variables were measured using three constructs of interest: legalism, expanded jurisdiction, and procedure. The construct of legalism was measured using the following variables: the number of parties represented by lawyers; whether the arbitrator was a lawyer; preliminary objections; evidentiary disputes; estoppel arguments; number of cases cited; number of witnesses; number of experts; labour relations considerations; filing of legal briefs; credibility attacks; total length of awards; and number of awards. It is important to note that the ‘labour relations considerations’ variable is of a different nature than the others. While these variables are generally taken to measure a higher level of legalism, the taking into account of labour relations considerations indicates a lower level of legalism, and is expected to be associated with decreased disposition times. Descriptive statistics and additional detail related to these explanatory variables and the other ones used in this study are presented in Tables 1 and 2.

The construct of expanded jurisdiction of the arbitrator was measured using a series of dichotomous variables. These variables measured whether arbitrators were asked to apply legislation and case law outside of their traditional jurisdiction. The variables included whether the arbitrators considered the following legislation in their awards: Charter of Rights and Freedoms, the Ontario Employment Standards Act, the Ontario Human Rights Act, the Ontario Occupational Health and Safety Act, privacy law, or some other statute. Additionally, one variable measured whether the arbitrator was asked to award a remedy that was not typical in the arbitration context, such as aggravated, punitive, or tort damages.

Various dispute resolution procedures were also measured, to determine their impact on the time function. The following dichotomous variables were measured: arbitration panel (sole arbitrator versus a three-person arbitration board); the use of statutory expedited arbitration; the use of contractually expedited arbitration; the use of mediation-arbitration; and the use of settlement. The reader might find the variable of “settlement” puzzling. Grievances that were completely settled by the parties without the later intervention of an arbitrator were not included in this study. However, a number of cases included in this study either settled some issues, but required an award to resolve the rest, or a settlement was reached by the parties, but they subsequently disagreed about the terms or the implementation of the settlement, and ultimately needed an arbitrator to resolve this disagreement.

In addition to my key explanatory variables, I also included variables to control for other factors that might impact grievance duration: the union involved; the grievance type; the grievance classification by subject matter; the applicable sector, classified using the North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) Canada 2012; related criminal proceeding; related human rights proceeding; some other related legal proceeding; and arbitrator workload (i.e., the number of cases the arbitrator arbitrated that year). Again, descriptive statistics for these control variables are provided in Tables 1 and 2.

Empirical Procedures

As previously indicated, this study examined the duration of four time periods: the pre-hearing phase, the hearing phase, the decision preparation phase, and the total disposition time (a sum of the first three periods). Estimates for each of these four time periods were obtained using a hazard model, a form of event history analysis. A hazard model allows one to see the impact of various explanatory variables on time functions (Ponak et al., 1996). The hazard model assesses the risk—at a particular moment—that a subject who has not yet done so will experience the target event. More specifically, this model is concerned with estimating the conditional probability of an event occurring—for example, the probability that a grievance will have a final arbitration award released in day 365, given that 364 days have passed without a final award. This is a key advantage over regression-based models, because hazard models suggest that the conditional probability of a grievance transitioning to the next phase (or concluding) can vary over time (Ponak et al., 1996; Campolieti, Riddell, and Slinn; 2007).

This study employed the Cox proportional hazard model. This form of the model assumes that the ratio of the hazard rates of any two subjects at any point in time is constant. An analysis of Schoenfeld residuals was conducted, which confirmed that the proportional hazards assumption was satisfied for these data (Singer and Willett, 2003, chapter 15). Since the coefficient estimates from a hazard model are difficult to interpret, I will present hazard rate ratios, which are the exponentiated coefficient estimates. Like odds ratios, hazard rate ratios greater than 1 correspond to positive coefficient estimates and indicate that they are associated with increases in the hazard or, equivalently, shorter duration times. Conversely, hazard rate ratios less than 1 correspond to negative coefficient estimates and are associated with lower hazard rates or longer duration times (Singer and Willett, 2003).

For each of the four time periods, I ran a specification of the main effects (without any interaction terms). Additionally, in order to test my hypotheses involving moderation (H3, H5, and H7), I also ran a specification using interaction terms for the four time periods. Likelihood ratio tests were used to decide which interaction terms to include. Therefore, there were eight sets of hazard ratio estimates produced (a specification with main effects only and a specification including interaction terms for each of the four time periods).

When interpreting the hazard ratios, it is important not to automatically infer causation from the explanatory variables on time. While there is no doubt a heavy causal effect of some explanatory variables on the duration of various grievance stages (e.g., number of witnesses causing delay at the hearing stage), the causal component of other hazard ratios is more tenuous. This is especially so with the variables related to the “procedure” hypothesis (e.g., three-member panel, statutory expedited arbitration, contractually expedited arbitration, med-arb, and settlement). For these variables, there might be issues with simultaneity and self-selection. For example, a party might opt for the statutory expedited arbitration of a simple grievance precisely because they believe the dispute to be straightforward and thus capable of quick resolution. Therefore, particularly for the hazard ratio estimates for these variables, it is best to think of the relationship with the dependent variable based on time as being associational. That said, I did check for endogeneity among the procedure variables and the other explanatory variables, and did not find any.[3]

I conducted a number of robustness checks to assess the results of the proportional hazard model. One of these checks involved an ordinary least squares (OLS) regression model, using natural log values of the time periods as the dependent variable. The results of the OLS regression model were similar to those of the hazard model. Additionally, I compared the results of the proportional hazard model with and without expedited arbitration grievances, to see if expedited grievances were different in some unobservable way. Again, the results were comparable.

Results

Table 3 provides the hazard rate ratios. The hazard rates for each stage (i.e., pre-hearing, hearing, and decision preparation) indicate the impact of a particular explanatory variable on the rate at which the grievance transitions to the subsequent stage (for example, from pre-hearing to hearing), or, in the case of decision preparation, the transition rate between that stage and the release of the final arbitration award. Hazard rates for the total disposition time indicate the impact of a particular variable on the rate at which the grievance transitions from being unresolved to final award. I will discuss each of the grievance time periods in turn.

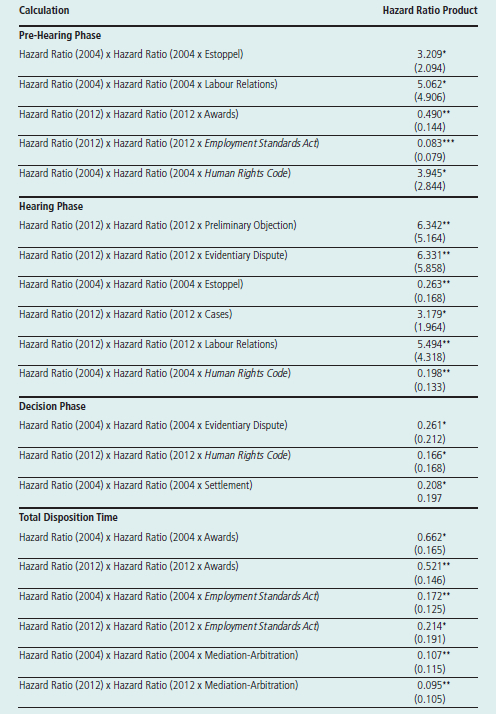

Table 3 shows the hazard rate ratios for the direct effects (in specification one), which allow us to evaluate H1, H2, H4, and H6. Table 3 also displays the interactions terms (in the second specification). In order to assess H3, H5, and H7, the hazard ratio for the relevant interaction term needs to be multiplied by the hazard ratio for the relevant year, and Table 4 provides these products where the results are statistically significant.

Pre-Hearing Phase

I will first analyze the results from the first specification. The hazard ratio for the year 2012 was significant at the .05 level, while the hazard ratio for 2004 was not. The year 2012 hazard ratio of less than 1.0 (0.595) suggests that, controlling for all other variables, the pre-hearing phase in 2012 was longer than in 1994. More technically, the rate of 0.595 indicates that the transition rate from the pre-hearing to the hearing phase for a grievance in 2012 was 40% slower than it was in 1994, all else being equal. This supports H1.

Turning to the legalism variables, only three were significant in the first specification for the pre-hearing phase: lawyer advocates, arbitrator lawyer, and length of decision. Consistent with H2, the presence of lawyers and arbitrators with legal training both tended to lengthen the pre-hearing phase. The hazard ratio of .80 for the lawyer advocates variable suggests that for every additional party represented by a lawyer, the transition rate to the next phase (the hearing) was 20% slower. The arbitrator lawyer variable had a hazard ratio of .709, indicating that for an arbitrator who has been called to the bar, the transition rate to the hearing phase was 29% slower. The hazard ratio of 1.007 for length of decision was contrary to expectations. This estimate suggests that the pre-hearing phase was quicker for those grievances that ultimately had longer written arbitration awards, relative to those cases with shorter arbitration awards.

Two variables measuring expanded jurisdiction were significant in the first specification of the model: the Charter and the Human Rights Code. A hazard ratio of .28 for Charter issues suggests that grievances with such issues transitioned at a rate 72% slower than cases without such issues. This is evidence in support of H4, and speaks to the lengthy amount of time the parties needed to prepare for complicated Charter litigation. The hazard ratio of 1.7 for Human Rights Code issues indicates that grievances involving human rights issues transitioned to the hearing phase at a rate 1.7 times faster than grievances not involving such issues, and this contradicts H4.

Table 3

Hazard Rate Ratios for Cox Proportional Hazard Model Estimates for Duration of Various Stages of Arbitration Process

Table 3 (continuation)

Table 3 (continuation)

Table 3 (continuation)

Table 3 (continuation)

Table 3 (continuation)

Notes: Estimates are reported as hazard ratios. Standard errors are in parentheses. The dependent variables (DVs) are measured in number of days. For Pre-Hearing, the DV is measured from the filing of the grievance to the first day of hearing. For Hearing, the DV is measured from the first day of hearing until the last day of hearing. For Decision Preparation, the DV is measured from the last day of hearing until the final arbitration award was released. For Total Disposition Time, the DV is measured as the total time for all three stages of the arbitration process (e.g., the combined times of the pre-hearing, hearing, and decision preparation stages). In addition to Arbitrator Workload, the control variables are as follows: Union, Sector, Grievance Type, Grievance Classification, Related Criminal Proceedings, Related Human Rights Proceedings, and Related Other Proceedings.

* Statistically significant at 10% level; ** at 5% level; *** at 1% level

Table 4

Significant Interaction Effects for Hypotheses Three, Five, and Seven (H3, H5, and H7)

Notes: Standard errors are in parentheses.

*Statistically significant at 10% level; ** at 5% level; *** at 1% level

Three variables measuring the use of dispute resolution procedures were significant: three-member panel; statutory expedited arbitration; and med-arb. The hazard ratio for three-member panel was 0.37. This indicated that the transition rate to the hearing phase was 63% slower when a three-member panel was used, relative to a sole arbitrator. The ratio of 3.3 for statutory expedited arbitration suggests that grievances that used this procedure transitioned 3.3 times faster than those that did not. These results provide some support for H6. The med-arb estimate of .56 indicated that those grievances using med-arb transitioned to the next phase 44% slower than grievances that did not use med-arb, contradicting H6.

The results of the first (direct effects) specification are useful in assessing hypotheses H1, H2, H4, and H6. In order to assess H3, H5, and H7, the hazard ratio for the relevant interaction term needs to be multiplied by the hazard ratio for the relevant year, and Table 4 provides these products where they are significant (these will sometimes be referred to as the “inter-decade comparison hazard ratios”, the “multiplicative hazard ratios”, and the “hazard ratio products”). H3 postulates that given levels of legalism are leading to longer delays with the passage of decades. For this hypothesis, there were three significant inter-decade comparison hazard ratios: estoppel in 2004, labour relations considerations in 2004, and awards in 2012. For estoppel, the hazard ratio product of 3.2 suggests that grievances with estoppel arguments transitioned to the hearing phase 3.2 times faster in 2004 than in 1994. This suggests that the grievance system was processing estoppel claims more quickly, contrary to the prediction of H3. For labour relations considerations, the hazard ratio product of 5.1 suggests that the presence of such considerations in 2004 made the transition to the next phase 5.1 times faster than it was when compared with the presence of such considerations in 1994. This result is supportive of H3—if legalism is expected to lead to more delay over time, the effect of a variable measuring the opposite of legalism (labour relations considerations) would be expected to be associated with less delay over time. The multiplicative hazard ratio for awards in 2012 also supports H3. It suggests that each additional award required to dispose of the grievance in 2012 slowed down the transition to the hearing phase by 51%, compared with 1994.

The hazard ratio products for the pre-hearing phase provided mixed support for H5, which predicted that expanded jurisdiction produces longer grievance times with each passing decade. With regards to Employment Standards Act (ESA) issues, the hypothesis is strongly supported for 2012. The multiplicative hazard ratio of .083 indicates that the transition rate for a grievance with an ESA issue in 2012 is about 92% slower than the transition rate for such a grievance in 1994. However, with regards to the Human Rights Code, there is evidence to contradict the hypothesis. Grievances with human rights issues in 2004 are likely to transfer to the hearing phase four times faster than 1994 grievances involving similar issues.

With regard to H7, there is insufficient evidence to reject the null hypothesis.

Hearing Phase

Again, we will start with the first specification. The hazard ratio for 2012 indicates that for that year, all else equal, the transition rate between the hearing phase and the decision phase was 30% slower than for 1994, lending support to H1.

With regard to the legalism variables, four were significant and lend support to H2: lawyer advocates, witnesses, experts, and awards. For each additional party at the hearing represented by a lawyer, the transition rate to the next phase was 31% slower. Not surprisingly, witnesses tended to lengthen the hearing phase. Each additional witness decreased the transition rate at the hearing by 13%. The addition of an expert witness decreased the transition rate at the hearing phase by 53%. Each additional award also decreased the transition rate of the hearing phase by 47%.

The results for the expanded jurisdiction and procedure variables were not significant, which means that we fail to accept H4 and H6.

When we examine the inter-decade comparison hazard ratios for the hearing phase (from Table 4), there is mixed support for H3. The 2012 hazard ratio products for preliminary objection and evidentiary dispute were each 6.3, indicating that arbitrations in 2012 with either of these issues transitioned to the decision phase 6.3 times faster than arbitrations with these issues in 1994. Moreover, the multiplicative hazard ratio for case citations in 2012 was 3.2, indicating that the transition rate for an equivalent number of cases cited (all else being equal) was 3.2 times faster in 2012 than in 1994. This suggests that the arbitration system is becoming more efficient, not less efficient, at dealing with legalism at the hearing phase. Nevertheless, two results were consistent with H3. The hazard ratio product for estoppel in 2004 was .26, indicating that arbitrations in 2004 with estoppel issues transitioned to the decision phase 74% slower than arbitrations with these issues in 1994. Additionally, the multiplicative hazard ratio for 2012 labour relations consideration was 5.5, indicating a transition time of 5.5 times faster than in 1994.

For the expanded jurisdiction variables, only one hazard ratio product was significant, and was in the direction predicted by H5. Arbitrations with human rights issues in 2004 transitioned at a rate 80% slower than hearings with such issues in 1994.

With regard to H7 (given procedures are producing shorter disposition times with each passing decade), the absence of significant multiplicative hazard ratios means that there is insufficient evidence to reject the null hypothesis.

Decision Preparation Phase

Again, we will start by focusing on the hazard ratios for the first specification. The direct effects for the years 2004 and 2012 were not significant. There appears to be little change in the speed with which arbitrators rendered decisions over the past two decades, (meaning H1 cannot be accepted).

With regard to the legalism variables, only two were statistically significant: legal briefs and credibility. Where legal briefs were filed, the rate at which the decision phase transitioned to a fully resolved grievance decreased by 58%, providing support for H2. As for credibility challenges, the rate at which the decision phase transitions was 43% slower than in the absence of such challenges. This finding also provides support for H2.

As for the expanded jurisdiction variables, human rights, privacy, and atypical remedy were significant, and these estimates provide mixed results for H4. The hazard ratio for Human Rights Code issues suggests that the presence of such issues, relative to their absence, decreased the transition rate by about 40%. This supports H4, which predicts that expanded jurisdiction will be associated with more delay. However, the hazard ratios for privacy and atypical remedy actually provide evidence towards refuting H4. For privacy issues, the transition rate increased by 2.5 times; and for atypical remedy, the transition rate increased by 1.9 times.

In terms of the results for the procedure variables, only three-member panel was significant, with a hazard ratio of .452. This indicates that the transition rate was approximately 55% slower when such a panel is used, versus a sole arbitrator, supporting H6.

Turning now to the inter-decade comparison hazard ratios, three were significant: evidentiary disputes in 2004, Human Rights Code issues in 2012, and settlement in 2004. The hazard ratio product of .26 for evidentiary disputes indicates that the decision phase transitioned to final award at a rate 74% times slower in 2004, relative to 1994, and this supports H3 (legalism is associated with more delay over time). This suggests that arbitrators are increasingly taking more time to deal with contested evidentiary issues during the decision phase. For human rights issues in 2012, the hazard ratio product of .17 indicates that the decision phase transitioned to final award at a rate 83% slower, relative to 1994, and this supports H5 (expanded jurisdiction is associated with more delay over time).

With regard to H7 (given procedures are producing shorter disposition times with each passing decade), the hazard ratio product for settlement in 2004 impugns it. The estimate of .208 suggests that the transition rate is about 80% slower in 2004 when the parties attempted to settle at least a portion of the grievance, relative to 1994.

Total Disposition Time

Again, we will start by examining the hazard ratios for specification 1. The hazard ratio of .54 for 2012 indicates that the transition rate from unresolved to resolved grievance was 46% slower in 2012, relative to 1994. This provides strong support for H1.

In terms of legalism, the following five variables were significant: lawyer advocates, arbitrator lawyers, preliminary objections, witnesses, experts, and credibility. Each additional side represented by a lawyer decreased the transition rate by about 24%. Arbitrators who were practising lawyers had a transition rate 37% slower, relative to arbitrators who were not practising lawyers. The transition rate for grievances with preliminary objections was 28% slower that those without such objections. Each additional witness decreased the transition rate by about 11%, and each expert decreased the transition rate by about 38%. Furthermore, credibility challenges were associated with an almost 40% decrease in the transition rate. All of this provides strong support for H2.

The expanded jurisdiction variables are a different story. None of them were significant, leading us to fail to reject the null hypothesis for H4.

With regard to the procedure variables, generally the results were consistent with H6. Three member panels were associated with longer disposition times, whereas statutory and contractually expedited arbitration were both related to shorter disposition times. However, both the med-arb and settlement variables were associated with longer disposition times, meaning that the additional steps entailed by these two procedures outweighed their potential expediency benefits where an arbitrated resolution is ultimately required.

With regard to the inter-decade comparisons (Table 4), only one legalism variable was significant—awards, in both 2004 and 2012. For each additional award required to dispose of a grievance, the transition rate was substantially slower than an additional award in 1994: 34% slower in 2004 and 48% slower in 2012. This is consistent with H3: the delays produced by the legalistic mechanism of multiple awards to resolve a single grievance are getting worse with time.

Turning to expanded jurisdiction variables, the multiplicative hazard ratios for ESA issues in both 2004 and 2012 are significant, supporting H5. The value of .172 indicates that arbitrations with ESA issues in 2004 had a transition rate about 83% slower than grievances with the same issues in 1994 (all else equal). Similarly, the inter-decade comparison of .214 for ESA issues in 2012 means a transition rate of 79% slower than for these issues in 1994.

Only the hazard ratio products for one procedural variable was significant: med-arb in 2004 and 2012. The hazard ratio product of approximately .1 for both years (.107 for 2004 and .095 for 2012) indicates that grievances involving mediation-arbitration in these two later years had a transition rate that was about 90% slower than grievances involving mediation-arbitration in 1994. This is contrary to what was predicted by H7.

Discussion

This study has a number of limitations that must be kept in mind. Firstly, as previously noted, it is safer to interpret the relationships between the explanatory variables and disposition times as associational, rather than causal, due to issues of simultaneity and self-selection. Secondly, some parameter estimates likely have a degree of measurement error related to missing information in the award. Arbitrators may have omitted certain details from their written awards, and it was these awards that formed the basis of the coding and statistical analysis. Thirdly, this study only deals with delay in a small subset, albeit a very important one, of grievances processed by the grievance system in Ontario. It only deals with those cases that proceeded all the way to an arbitrated award, which is estimated to be about 2-3% of all grievances filed (Thornicroft, 2009). It does not deal with the vast majority of cases that settle either at the internal stages of the grievance procedure, or after the parties get part way through the arbitration process.

Despite these limitations, the present study helps to provide a picture of arbitration delay since the last studies were conducted about 20 years ago. The results from the model support certain hypotheses but impugn others. The first hypothesis (H1) was, “Grievance arbitration disposition times are increasing with each passing decade.” The hypothesis was supported for the pre-hearing phase, the hearing phase, and for total disposition time. This finding is consistent with a long line of previous studies that have documented the trend towards longer dispositions times as the years go by. On the other hand, the decision preparation phase did not increase over the course of the study. This is remarkable given that arbitrations have become more complex with the passage of decades.

One potential explanation for this observed increase in delay can be ruled out: the increased volume of arbitrations handled by the average arbitrator. Arbitrator workload was not a significant explanatory factor for the duration of any of the four time periods of this study. This is largely consistent with the work of Ponak and colleagues (1996), who found that arbitrators with a high caseload did not generally impact duration times.

There was widespread support for H2, that legalism is associated with increased disposition time of grievances. However, as the findings of other studies suggest, different factors impact different phases. In the pre-hearing and hearing phases, and for total disposition time, the addition of lawyers as advocates increased the durations. Preliminary objections lengthened total disposition time (a finding not replicated in the Ponak et al. (1996) research). The addition of each witness lengthened both the hearing phase and the total disposition time, as did the use of expert evidence. The filing of legal briefs slowed down the decision preparation phase. Credibility attacks caused delay in the decision preparation phase and in total disposition time. Furthermore, interim awards lengthened the hearing phase.

To assess the impact of legalism, this study was the first to use a variable measuring whether the arbitrator was a trained lawyer. As part of H2, the expectation was that those arbitrators trained as lawyers would foster a greater degree of legalism in the arbitration system than those arbitrators without this training. The findings supported this hypothesis, as arbitrators who were called to the bar were associated with delay at the pre-hearing phase and with longer total disposition times. This finding has important policy implications, as Ministries of Labour might want to consider offering programs that emphasize the training of arbitrators who are not lawyers.

Interestingly, there were mixed results for H3, that legalism was associated with more delay with each passing decade. At the pre-hearing and hearing phases, the beneficial effect of labour relations considerations in reducing delay is getting stronger with the passage of recent decades (in other words, consistent with H3, the opposite of legalism is leading to less delay as time goes on). Also supportive of H3 is the effect of estoppel issues at the hearing phase, evidentiary disputes at the decision phase, and additional arbitration awards at the pre-hearing phase and on total disposition time, which are all associated with more delay with the passage of decades. However, the arbitration system actually seems to be getting more efficient at processing certain issues with passing decades, thus contradicting H3: estoppel in the pre-hearing phase; and preliminary objections, evidentiary disputes, and case citations in the hearing phase.

H4 was that the broadened jurisdiction of arbitrators is associated with increased disposition time, and the relevant findings are quite mixed. For total disposition time, none of the expanded issues appear to be leading to longer durations. If one looks at each of the three phases though, some variables are associated with delay. Examples include Charter issues lengthening the pre-hearing phase, and human rights issues lengthening the decision preparation phase. However, other issues outside an arbitrator’s typical jurisdiction are actually associated with shorter duration times, such as atypical remedies speeding up the decision preparation phase, and human rights issues speeding up the pre-hearing phase. On the one hand, a possible explanation for Charter issues leading to delay pre-hearing is that they are add-on issues complicating existing grievances. On the other, the parameters of human rights cases are typically more self-contained and well-defined, which leads to shorter pre-hearing phases when combined with the likely desire of both sides to have human rights issues dealt with quickly, given their often sensitive and emotional nature.

Also on the subject of expanded jurisdiction, H5 posited that the delay caused by this development is getting worse with the passage of decades. For issues involving the Employment Standards Act, this hypothesis is certainly supported, as grievances involving the ESA have significantly longer pre-hearing phases and total disposition time in later decades. One likely explanation for this finding is that many ESA issues require complicated factual and legal determinations, and have high stakes for the parties (examples include overtime and mass terminations). Also, grievances involving human rights issues are becoming significantly longer in subsequent decades at the hearing and decision preparation phases. Overall then, critics of Weber and Parry Sound will find some support for their argument that the arbitration system will become bogged down with matters traditionally litigated in other forums. However, itis important to note that grievances raising human rights issues after Parry Sound, which were likely the most impacted by the case, have not experienced any increase in total disposition times, and in fact were shorter at the pre-hearing phase. Also, the results of this study suggest that any delay caused by expanded jurisdiction needs to be examined on an issue by issue basis, as there are many issues (such as occupational health and safety, privacy, and atypical remedies) that are not causing growing delay in the arbitration system.

H6, that posits that particular dispute resolution procedures are associated with decreased disposition time, is generally supported. Single arbitrators, the statutory expedited procedure, and the expedited procedures that the parties agree to themselves all serve to decrease total disposition time, as well as to contract some of the individual phases. The use of single arbitrators has become near total, but the parties may be able to do more to exploit the promise of expedited procedures.

However, contrary to expectations at the outset of the study, med-arb and previous settlement lengthen, rather than shorten, total disposition time. These results mean that the time associated with the additional, unsuccessful step that is added by these procedures outweighs the potential expediency benefits of narrowing the issues and focusing the hearing. It is important to note that this finding only applies to grievances ultimately requiring an arbitration award, as grievances that are resolved at mediation or permanently settled by the parties themselves were not part of the present study.

The study also hypothesized that specific procedures are producing shorter disposition times with each passing decade (H7). The available evidence does not support this hypothesis. In fact, it appears that the lengthier total disposition times associated with med-arb are getting worse over time.

Conclusion

This research makes a number of substantial contributions to our knowledge of the arbitration system in Ontario. The study both replicates and extends past research, and examines developments that have occurred since the last studies were conducted. It uses a broader range of legalism and dispute resolution variables than previous studies did. Additionally, it is the first attempt to assess expanded jurisdiction. My results suggest that the constructs of legalism, expanded jurisdiction, and dispute resolution procedures are useful in thinking about the determinants of arbitration duration. Another contribution of this work is that it is the first to investigate the hearing phase in depth. This is understandable, given the fact that when previous studies were conducted, a one day hearing was far more common.

A number of recommendations for labour and management flow from the study’s findings. First, they both need to understand that the problem of delay is growing. Second, they need to be motivated to address delay by understanding the negative consequences (outlined in the introduction). Third, they should understand the key determinants of delay, and take steps where possible to eliminate them. While some delay is either inevitable or strategic, the parties need to understand that much of it is avoidable.

Parties who are motivated to reduce arbitration delay in their grievance procedure would do well to focus on the pre-hearing and hearing phases. These phases are much longer than the decision phase, and they are the ones that are growing over time. Also, the parties should consider agreeing to modify their arbitration procedure to better meet their needs and to reduce delay. They should make enhanced use of dispute resolution procedures, such as contractually expedited arbitrations. Additionally, as recommended by Justice Winkler (2011), the parties should strive for proportionality. In other words, the grievance ought to be resolved “in a manner that reflects the complexity, monetary value, and importance of the dispute” (Winkler, 2011; in Conclusion section).

A number of possibilities for future research flow from this work. An ideal future study will follow grievances longitudinally from the filing of the grievance, and will have grievances randomly assigned to various dispute resolution procedures. This design would deal with simultaneity, self-selection, and other endogeneity issues. Also, more research needs to be done on the myriad varieties of contractually expedited arbitration procedures, to determine which are most effective in reducing delay. Lastly, additional research should be conducted on the overall impact of expanded jurisdiction on efficiency. Comparative work should be done to see whether arbitration is resolving these expanded issues more quickly than they would have otherwise been resolved in their “home” forum (like the Ontario Labour Relations Board, in the case of the ESA complaints). If so, dealing with these issues in the arbitration context can still be justified on efficiency grounds even if they increase total duration in the labour arbitration system.

Appendices

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the many colleagues who have provided helpful comments and suggestions, and in particular, Anil Verma, Harry Krashinsky, David Doorey, Alexander Colvin, and the RIIR reviewers of this article.

Notes

-

[1]

See, e.g., Ontario’s Labour Relations Act, s. 48 (1) and (2).

-

[2]

The hazard ratios generated from the dataset with the outliers removed were compared to the hazard ratios generated with the outliers included, and they were very similar.

-

[3]

The estimates for the other explanatory variables were not changed by the presence or absence of the procedural variables in the model.

References

- Adams, George. 1978. “Grievance Arbitration of Discharge Cases.” Research and Current Issues Series, no. 38. Kingston, Ontario: Queen’s University Industrial Relations Centre.

- Bacharach, Samuel and Peter Bamberger. 2004. “The Power of Labor to Grieve: The Impact of the Workplace, Labor Market, and Power-dependence on Employee Grievance Filing.” Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 57 (4), 518-539.

- Bartel, Barry C. 1991. “Med-Arb as a Distinct Method of Dispute Resolution: History, Analysis, and Potential.” Willamette Law Review, 27 (3), 661-692.

- Bryman, Alan. 2008. Social Research Methods. 3rd ed. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Budd, John W. and Alexander J. S. Colvin. 2008. “Improved Metrics for Workplace Dispute Resolution Procedures: Efficiency, Equity, and Voice.” Industrial Relations, 47 (3), 460-479.

- Campolieti, Michele, Chris Riddell, and Sara Slinn. 2007. “Certification Delay under Elections and Card-Check Procedures: Empirical Evidence from Canada.” Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 61 (1), 32-58.

- Cappelli, Peter and Keith Chauvin.1991. “A test of an efficiency model of grievance activity.” Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 45 (1), 3-14.

- Dassios, Christopher M. 2010. “Innovative Approaches to Public Sector Dispute Resolution: Over a Decade of Expedited Arbitration in the Ontario Electricity Industry.” The Proceedings of the National Academy of Arbitrators, 63, 237-260.

- Foisy, Claude. 2002. “Cost and Delay in Arbitration: The Quebec Experience.” Labour Arbitration Yearbook, 2001-2002, 137-158.

- Freeman, Richard B. and James L. Medoff. 1984. What Do Unions Do? New York: Basic Books.

- Fricke, John G. 1976. An Empirical Study of the Grievance Arbitration Process in Alberta. Edmonton: Alberta Labour.

- Goldblatt, Howard. 1974. Justice Delayed… the Arbitration Process. Toronto: Labour Council of Metropolitan Toronto.

- Hebdon, Robert and Sung Chul Noh. 2013. “A Theory of Workplace Conflict Development: From Grievances to Strikes”. New Forms and Expressions of Conflict at Work. G. Gall, ed. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan, 26-47.

- Kauffman, Nancy L. 1992. “Expedited Arbitration and Other Innovations in Alternative Dispute Resolution.” Labor Law Journal, 43 (6), 382-387.

- Krippendorff, Klaus. 2013. Content Analysis: An Introduction to its Methodology. 3rd ed. London: Sage.

- Lewin, David. 1999. “Theoretical and Empirical Research on the Grievance Procedure and Arbitration: A Critical Review.” Employment Dispute Resolution and Worker Rights in the Changing Workplace. A. Eaton and J. Keefe, eds. Champaign, IL: Industrial Relations Research Association, 137-186.

- Nadeau, Denis. 2012. “Supreme Court of Canada and the Evolution of a Pro-Arbitration Judicial Policy.” Labour Arbitration Yearbook, 2012-2013, 325-348.

- Neuendorf, Kimberly A. 2002. The Content Analysis Guidebook. Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Sage Publications.

- Olson, Corliss. 1990. Time Delays in Grievance Arbitration in Alberta. Calgary: University of Calgary.

- Ontario Public Service Employees Union v. Seneca College of Applied Arts and Technology, 2006 CanLII 14236 (ON CA).

- Parry Sound (District) Social Services Administration Board v. O.P.S.E.U., Local 324, [2003] 2 SCR 157.

- Picher, Michel. 2012. “The Arbitrator as Grievance Mediator: A Growing Trend.” Labour Arbitration Yearbook, 2012-2013, 9-16.

- Ponak, Allen and Corliss Olson (1992). “Time Delays in Grievance Arbitration.” Relations industrielles/Industrial Relations, 47 (4), 690-708.

- Ponak, Allen, Wilfred Zerbe, Sarah Rose, and Corliss Olson. 1996. “Using Event History Analysis to Model Delay in Grievance Arbitration.” Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 50 (1), 105-121.

- Prasow, Paul and Edward Peters. 1970. Arbitration and Collective Bargaining: Conflict Resolution in Labor Relations. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Rose, Joseph B. 1986. “Statutory Expedited Grievance Arbitration: The Case of Ontario.” The Arbitration Journal, 41 (4), 30-45.

- Ross, Arthur. M. 1958. “The Well-Aged Arbitration Case.” Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 11 (2), 262-271.

- Rubin, Barry M. and Richard S. Rubin. 2003. “Creeping Legalism in Public Sector Grievance Arbitration: A National Perspective.” Journal of Collective Negotiations in the Public Sector, 30 (1), 3-14.

- Singer, Judith D. and John B. Willett. 2003. Applied Longitudinal Data Analysis: Modeling Change and Event Occurrence. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Sloane, Arthur and Fred Whitney. 1985. Labor Relations. 5th ed. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice Hall.

- Stanton, John. 1983. Labour Arbitrations, Boon or Bane for Unions? Vancouver: Butterworths.

- Thornicroft, Kenneth W. 1993. “Accounting for Delay in Grievance Arbitration.” Labor Law Journal, 44 (9), 543-553.

- Thornicroft, Kenneth W. 1994. “Lawyers and Grievance Arbitration: Delay and Outcome Effects.” Labor Studies Journal, 18 (4), 39-51.

- Thornicroft, Kenneth W. 1995. “Sources of Delay in Grievance Arbitration.” Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal, 8 (1), 57-66.

- Thornicroft, Kenneth W. 2009. “The Grievance Arbitration Process and Workplace Conflict Resolution.” Canadian Labour and Employment Relations. 6th ed. Morley Gunderson and Daphne G. Taras, eds. Toronto: Pearson Addison Wesley, ch. 13.

- Weber v. Ontario Hydro, [1995], 2, Supreme Court Reports, 929.

- Weiler, Paul C. 1980. Reconcilable Differences: New Directions in Canadian Labour Law. Agincourt, Ont: Carswell.

- Whitaker, Kevin. 2009. “The Development and Use of Mediation/Arbitration in Ontario.” The Proceedings of the National Academy of Arbitrators, 62, 209-214.

- Winkler, Warren K. 2010. “Labour Arbitration and Conflict Resolution: Back to our Roots.” Speech presented as the Donald Wood Lecture, Queen’s University, Kingston, ON, Canada. Accessed at http://www.ontariocourts.ca/coa/en/ps/speeches/2010-labour-arbitration-conflict-resolution.htm (March 20, 2016).

- Winkler, Warren K. 2011. “Arbitration as a Cornerstone of Industrial Justice.” Accessed at http://www.ontariocourts.ca/coa/en/ps/speeches/2011-arbitration-cornerstone-industrial-justice.htm (March 20, 2016).

- Winter, Catherine. 1983. Grievance Arbitration Cost and Time. Toronto, Ontario: Research Branch, Ontario Ministry of Labour.

List of figures

Figure 1

Results of previous studies, average total duration of grievance by year of study

List of tables

Table 1

Descriptive Statistics

Table 2

Comparison of Means

1 Significant Difference Between Means for 1994 and 2004 (.01 level)

2 Significant Difference Between Means for 1994 and 2004 (.05 level)

3 Significant Difference Between Means for 1994 and 2004 (.10 level)

4 Significant Difference Between Means for 1994 and 2012 (.01 level)

5 Significant Difference Between Means for 1994 and 2012 (.05 level)

6 Significant Difference Between Means for 1994 and 2012 (.10 level)

7 Significant Difference Between Means for 2004 and 2012 (.01 level)

8 Significant Difference Between Means for 2004 and 2012 (.05 level)

9 Significant Difference Between Means for 2004 and 2012 (.10 level)

Means were compared using the Student-Newman-Keuls (SNK) test.

Table 3

Hazard Rate Ratios for Cox Proportional Hazard Model Estimates for Duration of Various Stages of Arbitration Process

Table 3 (continuation)

Table 3 (continuation)

Table 3 (continuation)

Table 3 (continuation)

Table 3 (continuation)

Notes: Estimates are reported as hazard ratios. Standard errors are in parentheses. The dependent variables (DVs) are measured in number of days. For Pre-Hearing, the DV is measured from the filing of the grievance to the first day of hearing. For Hearing, the DV is measured from the first day of hearing until the last day of hearing. For Decision Preparation, the DV is measured from the last day of hearing until the final arbitration award was released. For Total Disposition Time, the DV is measured as the total time for all three stages of the arbitration process (e.g., the combined times of the pre-hearing, hearing, and decision preparation stages). In addition to Arbitrator Workload, the control variables are as follows: Union, Sector, Grievance Type, Grievance Classification, Related Criminal Proceedings, Related Human Rights Proceedings, and Related Other Proceedings.

* Statistically significant at 10% level; ** at 5% level; *** at 1% level

Table 4

Significant Interaction Effects for Hypotheses Three, Five, and Seven (H3, H5, and H7)

10.7202/050811ar

10.7202/050811ar