Résumés

Abstract

This paper examines the process and outcomes of bail hearings, focusing on cases where defendants’ hearings involved administration of justice and sentencing offences. The data analyzed for this project suggests that despite the presumption of innocence and non-punitive official objectives of judicial release, the practice by law enforcement and courts at this stage of the process tends towards punitiveness. These punitive responses are illustrated by three main findings that relate to the detention of individuals accused of administration of justice or sentencing offences, the number of conditions of release breached per combination of charges, and the breached conditions of release. These processes are understood through a durkheimian lens, using Fauconnet’s work which considers the social function of punitive processes as focused on annihilating the criminal act to establish social order. As will be seen, this function is achieved through the selection of a scapegoat that is rapidly punished, rather than appropriately assigning individual liability.

Résumé

Cet article analyse le fonctionnement et les résultats des audiences de mise en liberté sous caution, en mettant l’accent sur les cas où les audiences des défendeurs concernaient les infractions relatives à l’administration de la justice et à la détermination de la peine. Les données analysées suggèrent que, malgré la présomption d’innocence et les objectifs officiels non punitifs de la mise en liberté sous caution, la pratique des forces de l’ordre et des tribunaux, à ce stade de la procédure, tend à être punitive. Ces réponses punitives sont illustrées par trois éléments principaux, soit la détention de personnes accusées d’infraction à l’administration de la justice, le nombre de conditions de libération violées par combinaison d’accusations et les conditions de libération non respectées. Ces processus sont analysés sous une perspective durkheimienne, en utilisant le travail de Fauconnet qui considère la fonction sociale des processus punitifs comme centrée sur l’annulation de l’acte criminel pour établir un ordre social. Cette fonction est assurée par la sélection d’un bouc émissaire rapidement sanctionné, plutôt que par l’attribution appropriée de la responsabilité individuelle.

Resumen

Este artículo analiza el procedimiento y las decisiones de las audiencias de libertad bajo fianza, haciendo hincapié en los casos de acusados cuyas audiencias conciernen infracciones relacionadas con la administración de justicia y con la determinación de la pena. Los datos analizados proponen, que a pesar de la presunción de inocencia, y de los objetivos oficiales no punitivos de la libertad bajo fianza, la práctica de las fuerzas del orden y de los tribunales en ese estado del procedimiento tiende a ser punitiva. Dichas respuestas punitivas se ilustran con tres elementos principales : la detención de personas que han sido acusadas por la comisión de una infracción en contra de la administración de justicia, el número de condiciones de liberación que han sido violadas por la combinación de cargos, y de las condiciones de libertad que no han sido respetadas. Estos procesos se analizan bajo una perspectiva durkheimiana, empleando el trabajo de Fauconnet, el cual considera la función social de los procesos punitivos basada en la condonación del acto criminal para así establecer un orden social. Esta función se lleva a cabo con la selección de un chivo expiatorio, que se sanciona rápidamente, en lugar de hacerlo con atribución apropiada de la responsabilidad individual.

Corps de l’article

Despite the protection of the presumption of innocence and the official non-punitive objectives behind the bail process, actual bail practices in Canada have increasingly operated otherwise in the name of expediency and at the cost of an increasing remand prison population[1]. This paper contributes to this discussion by presenting the experience of bail hearings in the Montréal seat of the Court of Québec. It focuses on administration of justice offences through data collected from courtroom observations and access to the court files of each accused. Although preliminary, the data collected suggest that these offences are overused and that their management contributes to greater punitiveness in the criminal justice process. This process is contextualised within Fauconnet’s theory regarding punishment’s social function in establishing and maintaining order. The paper begins by contextualizing the bail process in the current law and scholarship and proceeds by analyzing the data collected in three steps. First, by examining the data that relates to the rate of detention of individuals accused of administration of justice or sentencing offences[2] ; second, by exploring the number of conditions breached per charge combination ; and third, by looking at the type and frequency of breached conditions. This analysis illustrates the various ways that actors in this process contribute and enable punitiveness. Throughout this article, punitiveness as a concept is understood by referring to the wider criminological literature. This understanding of punitiveness applied to the bail process is merged with sociological constructivist approaches, and more specifically Fauconnet’s work, which considers the social function of punitive processes as establishing and maintaining social order by annihilating the criminal act. As will be seen, this function is served by the bail process and is achieved through the selection of a scapegoat that is rapidly punished, rather than appropriately assigned individual liability[3].

1 The Law and Literature on Bail

Prior to 1972, bail[4] in Canada was granted at the near-total discretion of the presiding judge, with the central theory of bail relying on sureties to discourage defendants from absconding[5]. In some jurisdictions, this amounted to a cash-for-bail system of questionable legality in which release from pre-trial detention depended on the ability of the accused or a surety to amass and sometimes deposit a sum of money[6]. As a result, the 1969 Ouimet Report recommended broadening the situations constituting bail and adding as a criminal offence the breach of a solemn undertaking[7]. Furthermore, the earlier Archambault Report recommended that prisons be used for protecting society as well as for offender rehabilitation[8]. Inspired by these reports, the 1972 Bail Reform Act[9] laid the groundwork for what has become s. 515 of the Criminal Code, in which a general presumption of release is stated, with the least restrictions possible, subject to some exceptions[10]. Moreover, section 11 e) of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms[11] entrenches the right to reasonable bail. Concurrently, s. 145 of the Criminal Code makes it a criminal offence to breach a condition of release and is one of what are known collectively as “administration of justice offences” : criminal offences that result from breaching judicial orders made prior to a finding of guilt. These offences parallel “sentencing” offences, such as breaching a probation order, or failure to comply with a recognisance entered into under s. 810 of the Criminal Code.

1.1 The Remand Crisis and Bail

The term “remand crisis” describes an alarming trend in Canada’s incarcerated population demographics : nationally, more than half of the people held in provincial detention facilities are being detained before trial and before a finding of guilt — referred to being held on remand[12]. Most explanations given in scholarship regarding the continued increase in the remand population fall into one of two categories : explanations highlighting problems with the law, and explanations focusing on the behaviours of actors within the criminal justice system, including Crown prosecutors, judges, and accused persons and their counsel, with many scholars citing a combination of the two[13]. As will be explored in details below, despite legislative changes, remand populations have increased steadily since the 1970s. Thus, to rely only on the law and legislative drafting would not explain the observed results.

Explanations regarding the law must also account for its implementation, rendering the second set of explanations both more interesting and a more fruitful ground for discovery. Scholars have noted the changes in charge patterns such that administration of justice offences both comprise an increasing number of the overall charges and are charged alongside other criminal offences[14]. Burczycka and Munch note that in 2014, 10 % of police-reported crimes in Canada involved a breach of conditions and 39 % of completed adult cases in 2013-2014 included at least one administration of justice infraction[15]. These charge patterns and the justice system’s response to administration of justice offences, which will be discussed below, consistently show a punitive pattern in the actions of various members of the justice system[16]. Conditions of release restrict several aspects of the accused individual’s liberty, notably their freedom of movement and their freedom to make decisions regarding their mental and physical health (particularly in the context of restrictions on substance consumption or requirements to participate in various therapies), with the threat of a criminal offence if the person fails to comply with their conditions.

The attitudes and thought processes driving these behaviours must also be noted. Some scholars contend that risk-aversion in the criminal justice system is pervasive, particularly amongst judges and prosecutors[17]. Accordingly, these criminal justice actors overemphasise protection of the public and under-recognise the importance of the presumption of innocence as an overarching function of criminal justice, leading these actors to favour the detention of accused persons to await a finding of guilt, rather than “risk” liberating an accused (albeit innocent) person who may accumulated additional criminal charges. Indeed, recent research from Québec seems to suggest that judges, prosecutors, and police officers all place a primal importance on protecting the public, even occasionally at the expense of the rights of the accused[18]. Some scholars, however, have noted both the existence of certain attitudes regarding bail and administration of justice offences which contribute to punitiveness. Notably, in both adult and youth criminal justice, scholars have noted that judges also use the bail system for other, extra-legal agendas, such as imposing conditions to teach the youth a lesson[19] or responding to breaches of conditions with a custodial sentence to enforce respect for orders of the court[20]. Similarly, police officers occasionally make the decision to detain an accused person if their criminal record shows previous breaches of conditions[21]. These patterns should be concerning to scholars of and participants in the criminal justice system because, stated plainly, they suggest that actors within the system are using the options and tools available to them to punish accused persons for reasons unrelated to the purpose of the criminal justice system.

1.2 Bail and Administration of Justice Offences

Scholarship has begun drawing a link between the remand crisis, bail hearings, and the management of administration of justice offences. The latter are, in effect, “judicially-created offences[22]”.

This paper considers administration of justice and sentencing-related offences as being distinct and worthy of being distinguished, for two reasons. First, these offences are found in two distinct parts of the Criminal Code : Part IV governs administration of justice infractions, whereas sentencing infractions such as breach of probation are contained in Part XXIII which governs matters related to sentencing. The infractions arise at different stages of a person’s interaction with the criminal justice system, both per the governing law and from a factual standpoint. Second, although superficially these infractions appear similar, administration of justice offences contained in Part IV arise from court orders imposed on someone who is legally innocent of the original offence with which they were charged. In contrast, infractions under Part XXIII follow either a formal finding of guilt or an acknowledgement of wrongdoing by the accused person, at which point the Canadian criminal justice tradition accepts that punishment may legitimately be imposed. The purpose of distinguishing the two both allows the paper to focus specifically on outcomes and the functioning of bail hearings and judicial release in Montréal, as well as an acknowledgement of the structure of the legislation governing the procedures.

Webster et al. tie the prosecution of more administration of justice offences to increased case complexity, thus contributing to the remand crisis and judicial delay[23]. The complexity arises out of the sheer number of charges that must be resolved, necessitating an increase in court appointments[24]. An examination of the existing data suggests that of all decisions taken in criminal matters in Canada in 2015-2016 (the most recent years for which data is available), 22.8 % were regarding administration of justice offences[25]. During the same period, 40.1 % of the administration of justice offences were single charge cases, forming a total of 24.4 % of all single charge cases[26].

Scholars tend to point to the increase of conditions imposed as the cause for the increase in administration of justice cases. In a recent study by Myers, the average number of conditions on which an adult accused was released on bail was 7.8 (with the median at 7)[27]. In Weinrath’s study of inmate perceptions of the remand crisis, interviewees criticised the strictness with which administration of justice offences were imposed in terms of the conditions imposed and the expectations of inmates, including regarding substance addiction, and suggested reform to the bail system to make the conditions easier to meet[28]. Vacheret and Brassard’s interviews with inmates revealed a similar view from inmates[29]. Similarly, Sylvestre et al. note the impracticality and impossibility of spatial restriction conditions and their impact on marginalised and homeless defendants[30]. Indeed, they highlight that these types of conditions are used by police officers in justifying arrests in a quick and efficient manner without having to demonstrate additional reasons for having arrested the person in the first place[31]. This pattern of police behaviour results in a “wrong place, wrong time” situation for defendants whose arrests are justified by police after the fact. Examining similar phenomena in youth criminal justice processes return the same result : more bail conditions invite more opportunities to breach said conditions, leading to an increase in criminal charges and arrests[32].

The phenomenon is problematic, not simply because they are criminal charges whose existence are contingent on a court order, but because they criminalise otherwise non-criminal behaviours and such criminalisation occurs prior to a finding of guilt on the original charges[33]. In this system, a person could be charged for Offence A, be released with conditions X, Y, and Z, breach condition Y, be charged with Offence B (breaching condition Y), and be found guilty of Offence B, all before a determination of guilt is rendered regarding Offence A. Yet, the only reason that the person is even subject to the court’s authority at all is the charge regarding Offence A. This phenomenon was observed in the data collected for the project.

The above discussion regarding observed attitudes of criminal justice actors regarding bail conditions bears further reflection and nuance. In imposing conditions in part to “teach a lesson” to offenders, or to enforce respect for the court, breaching bail conditions can then be characterised as disrespect of the authority of the court requiring punishment[34]. That inmates perceive stringency regarding administration of justice offences is understandable when research into police justifications for administration of justice offences note the police use of these offences for investigative purposes disconnected from perception of harm to anyone, and without the otherwise required reasonable grounds necessary for arrest[35]. As will be discussed throughout this paper, these trends observed in scholarship may be indicative of a broader theme, namely, that the bail process and the related administration of justice offences are a method of maintaining social order through its punitive aspects, including some of its conditions and the punishment of these breaches.

1.3 Punitiveness and Maintaining Social Order

The relationship between the bail process, punishment, and punitiveness is not officially recognized in the law’s articulation of the objectives of bail. This article refers to a wider notion of punitiveness and punishment found in the criminological literature, which along with Fauconnet’s work on punishment, can enable an understanding of the social function served by the bail process.

The concept of punitiveness is widely used in criminological literature, but remains under-theorized[36]. Stanley Cohen has characterized punitiveness as including coercion, formalism, moralism and the infliction of pain on subjects by a third party[37]. This notion is wide and can include mechanisms of social control that can be subtle, less visible, and discreet[38]. Punishment and sanctions can also be understood as those that involve an increase in pain infliction as well as those that involve “emotive and ostentatious punishments”. The literature has highlighted that these mechanisms involve the creation of a greater plurality of the sites of adjudication, which ultimately serve to expand and enhance crime control[39]. They not only include prison sentences, but also shaming and stigmatizing responses as part of penal controls in which punitiveness and vindictiveness play a leading role as part of an expressive function. More recently, governments have officially used the language and goals of risk management and prevention to officially depart from the aims and language of public and punitive justice[40]. According to the logic of new styles of managerialism, there should be a decrease in retribution, since these tools are officially considered utilitarian. However, it has been argued that these strategies provide the conditions for the survival and expansion of retribution and punishment by contributing to an increasingly diverse range of sanctions[41]. Hudson has also added that this pseudo-scientific enterprise masks a thinly veiled moralism and subjectivism, which indeed seems to include retributive aspects. Indeed, Jonathan Simon has pointed out that a major contributor to the rise in prison populations in recent years has been the spread of managerial practices that include risk-aversion mechanisms, such as parole, that contributed to the imprisonment of a significant number of violators[42]. This analysis can indeed be extended to the bail process and its implementation as will be discussed below. In this respect, even if not formally and officially recognized by the law as a mechanism for punishment, the bail process through its implementation and effects, can be considered as a mechanism that expands social control, net widens sanction and contributes to wider punitiveness.

Legal constructivists have developed analytical conceptions that enable a greater understanding of the role of punitiveness and responsibility in liberal societies. Constructivists see crime as a social construct and a normal and fundamental feature of social life. There will always be individual divergences from the collective and among them, some behaviours will be characterized as criminal to maintain order within social conscience. If social conscience became so strong that some crimes would disappear, it would find other divergent behaviour to sanction more severely even if not previously considered criminal. Consequently, crime that disappears under one form reappears under a different one[43].

Rooted within a constructivist perspective, Fauconnet’s theory is particularly helpful in understanding bail. This theory begins with the premise that the social function of punishment is to restore the social order troubled by the criminal act[44]. He conceives responsibility into two successive phases. The first occurs when the collective conscience develops a form of responsibility in response to an act considered abhorrent which remains for a certain period of time as floating (“flottante[45]”). The second phase occurs when such responsibility is attributed to a specific person[46]. This imputation of individual responsibility is transformed into culpability. It never occurs without the first phase in which liability remains floating — suggesting that such responsibility is not first and foremost attached to an individual, but rather to an act considered a crime[47]. Indeed, Fauconnet posited that the receptacle of the criminal sanction was not the individual but the behaviour itself. Since we cannot sanction the latter, the person serves as its proxy or scapegoat (“bouc émissaire[48]”).

Fauconnet highlights that finding a person to sanction and punish is always more important than actual evidence of this person’s culpability. In this respect, the utility of punishment is not essentially in its action against individuals accused of crimes, but in its action towards society[49]. Through punitiveness, whether symbolic or legal, the crime’s wrong is compensated, the moral order is restored, and society regains confidence in itself and reaffirms the intangibility of the rule that was breached[50].

Essentially, Fauconnet challenges the official purported aim of punishment, and argues that its function is not as much to target the author of the crime, but the criminal behaviour that has troubled the social order[51]. In this sense, what societies want to attack and annihilate is the crime itself, but since the crime belongs in the past and cannot be undone, societies look for an individual that they can substitute to crime and that they can suppress[52]. Hence, this individual, is treated as a sacrificial scapegoat to become a symbolic substitute of the past crime. There are various ways to punish the individual in order to treat the crime and Fauconnet highlights that the person needs to be designated explicitly through a process recognized by society that rapidly reacts to a behaviour that is designated a crime. As will be seen, the bail process can be understood within this logic. Indeed, its implementation, conditions of release and effects are rapid, operate early on in the criminal process and do not require much evidence or any tailoring to the individual. Hence, this punitive process can be understood as targeting the criminal behaviour and serving the establishment of social order within society.

Fauconnet’s work is based on Durkheim’s conception of social facts and morality being a product of society, and thus is open to some of the same criticisms. On one hand, such constructionist conceptions of human existence and society appear to conflate the meaning of an objective fact with the fact itself[53]. Such criticism argues that the intrinsic properties of social actions have no inherent meaning ; their meaning results from other physical events which occur in proximity to the action under study, and in relation to defined meanings[54]. Relatedly, constructivist thought has also been criticized for its under-valuing of the individual within society, particularly when it comes to questions of morality. Notably, Durkheimian conceptions of society assume that society is homogenous ; thus, while differentiation in morality and ethics may occur across societies, within particular societies the understanding of morality and ethics will be consistent[55].

However, in the context of criminal justice, the meaning of certain social actions is explicitly pre-defined, in part because it is an institutional representation of society’s response to a hateable (criminal) act. Thus, acts such as incarcerating an accused person (primarily a punitive act) are, within the system in which responsibility is carried out, imbued with inherent meaning. Moreover, even criticism on the conflation of act and meaning acknowledges that many of the starting assumptions of constructivist theories are correct, notably those which concern the role of society in creating and enforcing morality[56]. Finally, the social construction of morality is compatible with postmodern theory. In particular, these theories tend to reject notions of “universal” or natural laws, relying instead on social production of morality compatible with postmodernism’s rejection of “objective” knowledge production untainted by factors such as social location of the knowledge gatherer or producer[57]. By extension, conceptions of responsibility which situate it within a social context, as does Fauconnet, are actually compatible with postmodernist theory.

1.4 Contribution of this Project

This paper contributes to the existing research on bail by presenting new data from a different jurisdiction, namely Québec, and by analysing the interplay between charges, conditions, and offences to shed light on court processes at the bail stage. Findings of this paper support prior findings regarding the contribution of administration offences to the caseload volume in the criminal justice system. However, to date, most published research on bail practices originates in southern Ontario courtrooms. In order to understand the remand crises and bail practices in Canada, more research should be conducted in a variety of jurisdictions. Additional data collected from various jurisdictions and settings can enable the development of theories, propose explanations, as well as solutions to what is considered a national problem. This paper consists of an important step towards this direction.

In particular, prior research indicating the utility of recognising “work group cultures” within courtrooms supports the development of a deeper understanding of the ways in which individual courtrooms function[58]. It also complements certain characterisations of the work group actors, in particular with regards to their risk aversion. The paper suggests that given the implications and justifications given for behaviour and strategic choices by judges, prosecutors for the Crown, and police, the appropriate characterisation of the bail system at this pre-trial stage of the criminal justice process is that it is punitive, as this term is understood by the criminological literature. This literature is complemented by constructivist sociological theories of crime that enable a greater understanding of the function of punitive processes within society. The merging of these theories provides an original lens with which to understand the bail process, its implementation, and the social function that it serves in society.

2 Research Methodology and Process

This project relied on a two-step research methodology, with the explicit goals of the project to begin to develop a portrait of how bail hearings are dealt with in courtrooms. The first part involved direct observation of 117 bail appearances[59] held in courtrooms dedicated to bail hearings at the Court of Québec in Montréal[60]. The accused persons were all, at the time of their hearing, being detained but had already been before a judge at least once for their first appearance and was not released at that time.

Observations were conducted on eight days in 2016 : three days in June, one day in July, three days in August and one day in November. No attempt was made to observe specific judges, cases, or offences. The observing authors sat in courtrooms dedicated to bail hearings and took notes on a series of elements, including the name of the accused and their number on the docket, whether the person was released and if so under what conditions, the nature of the accusations (if mentioned), and basic biographic data such as age, gender, and occupation, where mentioned. All notes were taken by hand, as the use of electronics is prohibited in the courtrooms, and subsequently transcribed electronically.

The second step of the research process involved accessing the court files for each appearance observed. This second step involved an examination of files in which the accused was charged with administration of justice or sentencing offences[61]. The examination of the files allowed the possibility to take more detailed notes regarding the details of the charges and offences, including all circumstances available, dates, and any information related to sentencing. The file research occurred after the hearings and there were frequently several months between the observed appearance and accessing the files. Although the contents of the files were not identical across cases, generally speaking the files included the procès-verbal of each appearance, warrants of committal signed by presiding judge (or orders to release) for each appearance, a list of conditions of release if the accused person was released, and occasionally the plumitif (summary of the legal trajectory of the accused person) for the accused. This second part of the research process was crucial for information gathering given most appearances were quite short.

As this project focuses on the bail hearing stage, the data collected centred on this step in the criminal justice process. Although information regarding matters such as preventive detention and sentencing were collected, its relevance is considered only in relation to the proceedings and outcomes at the bail appearance as observed in court. In effect, the goal was to create a snapshot of the appearances and the situation of the accused persons at that moment in time, in the context of what had occurred prior to the appearance. The analysis of the data will similarly be restricted to descriptive statistics intending to elucidate the processes and outcomes of the appearances that were the subject of observation under the first step.

3 Analysis : Reviewing the Data[62]

3.1 Characteristics of the Dataset

The original dataset is comprised of data collected from 117 bail appearances and the court files associated with accused persons present at those appearances. Some of these involved the same accused person as their hearing had been rescheduled to the second date. All appearances were conducted in person, meaning the accused persons were transported from detention centres to the Palais de Justice de Montréal for the appearance. At the time, the courtrooms dedicated to bail hearings were not designed to conduct video appearances (where the accused appears from the detention centre at which they are held via video technology)[63].

In 58 of the appearances (slightly less than 50 %), the accused was released subject to conditions. In the remaining 59 appearances the accused was detained, whether because the appearances were rescheduled to a later date (35 appearances), the accused renounced their right to release (5), the accused was undergoing an evaluation for criminal responsibility (2) or capacity (1), the accused pled guilty (15), or because the judge ordered detention following a hearing (2).

Table1

Percentages of types of criminal offence

Table 1 describes the complete dataset, excluding repeat cases, based on the characterisation (“type”) of the criminal offence(s) with which the accused was charged. The category of “other” offences refers to offences which only occurred once or twice of the course of the observations, such as a combination of an offence against the person and a firearms offence, drug offences, or offences against property and a firearms offence. Because they were so few and did not impact the main object of the present study, they were grouped together for the purposes of this preliminary analysis. Otherwise, a notable pattern that emerges from this dataset is that 62 of 112 defendants (48.1 %) were charged with more than one type of offence. Of these 62 defendants, 49 of them were charged with at least one administration of justice or sentencing offence. Of these, the authors were able to access the court files for 45 defendants[64]. The final 45 form the basis of the remainder of this analysis.

Finally, the chi-squared value of the original dataset, comparing rates of detention where an administration of justice or sentencing offence is charged versus when it is not, is 18.4054 with one degree of freedom, indicating a less than one in one thousand chance that the result described above is not random. Thus, although the sample size is relatively small, the results of this study provide a first portrait of administration of justice offences and their management in this jurisdiction. The following discussion lays important groundwork, which highlights the need for further inquiry into the data surrounding administration of justice and sentence offences.

3.2 Charge Combinations

Table 2 demonstrates the main categories of charge combinations, broken down by number and percentage of defendants to whom these charge combinations are attached. For the purposes of clarity, unless otherwise indicated “criminal offence” refers to any criminal offence that is not a sentencing offence or administration of justice offence.

Table 2

Accused Charge Combinations Numbers and Percentages of Detention and Release

At 32 detentions out of 45 cases (71.1 %), the data clearly demonstrates a higher rate of detention for individuals accused of any of the sentencing or administration of justice offences charge combinations, compared to the 50 % general rate of detention of the court observation data. Also captured in this data is that 53.3 % of the accused persons are charged with a criminal offence alongside a sentencing offence or administration of justice offence (or both), comprising 24 out of the 45 accused persons.

Turning to the types of criminal offences individuals were charged with in addition to the sentencing or administration of justice offences, Table 3 presents the main charge combinations. The data comprise 25 cases. These offences will be treated together without distinctions on whether they were charged alongside sentencing or administration of justice offences.

Table 3

Number and Percentages of Criminal Offence Charges

An overwhelming majority of the accused were charged with offences against the person-altogether, about 20 of the 25 individuals were so charged. These offences broadly fall into the categories of harassment, making threats, various levels of assaults, including assaulting a police officer, and a few sexual assaults. Where the obstruction of justice charges occurred alongside an offence against the person, the charges were closely tied : for example, the accused persons in those cases were charged with uttering threats or harassment and attempting to convince a person to rescind a complaint made to police. Charging trends will be further explored in the examination of breaches of conditions leading to administration of justice and sentencing offences.

3.3 Conditions Breached and Administration of Justice and Sentencing Offences

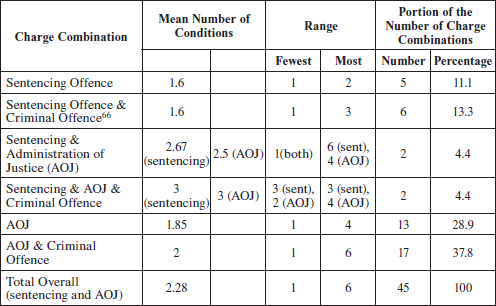

Table 4 demonstrates the mean[65] of charged conditions breached in each category of charge combination as well as the range of the number of conditions breached. These breached conditions are reflected by the charges laid against each defendant at the time of the appearance, irrespective of the outcome of the case. This table demonstrates the main categories of charge combinations, broken down by number and percentage of the accused persons. For the cases in which the individual was charged with both administration and justice and sentencing offences, the mean and ranges of both sets of conditions were recorded.

Table 4

Number of Conditions Breached per Charge Combination[66]

The above table suggests a few notable patterns in the conditions and the breach thereof. First, when defendants breach their conditions of release, they tend to breach more than two conditions at once, which suggests that some conditions placed on accused persons for their release overlap in restricting the behaviour they are intended to curtail and raise the possibility of one act resulting in two distinct breaches. By extension, this may also potentially support the concerns raised above in discussing police charging patterns in the context of spatial restrictions : having only a few conditions breached in isolation and separate from any other criminal offence, could be consistent with the “wrong place, wrong time” explanation given for police charging for breach of conditions described above[67]. Second, a higher number of conditions breached seem to co-occur with the accused having also committed another criminal offence. Charging criminal offences in tandem with breaches of conditions may reflect a commonly assumed police practice of charging a variety of possible offences, leaving it to the prosecutor to determine which ones to pursue[68] ; however, an absence of available official information on police practices in this regard requires that this suggestion be taken with caution. Third, it appears that a person tends to be charged with more administration of justice offences than sentencing offences. This outcome may suggest that more stringent, untailored, and unrealistic conditions are placed on individuals that have been released on bail than those who were on probation. Overall, these explanations recall the concerns articulated by several scholars that more conditions for release sets up an accused for failure, and the constructivist interpretation of administration of justice offences as a rapid response to a perceived criminal act rather than a tailored and individual treatment of responsibility.

A related trend, although not the focus of this paper, should be considered here. Observations noted an increase in guilty pleas at the bail hearing stage following the release of the R. v. Jordan decision[69] in July 2016. Of the 17 appearances observed prior to Jordan, only one resulted in a guilty plea at the bail appearance (5.9 %). In contrast, in the period of observation following the decision, 11 of the 28 appearances resulted in a guilty plea on at least one charge or set of charges at the bail appearance (39.3 %). The impetus to shorten the delays in which cases reach their conclusion may be affecting proceedings even at this early stage in the criminal process and combining with the above-described patterns in a way that further tilts the process towards punitiveness by pushing for early resolutions via guilty pleas. However, to further this hypothesis access to data regarding decisions to charge and not charge individuals arrested by police and whether Jordan has affected this stage of the criminal justice process (i.e. whether there has been a reduction in charging in response to Jordan), is necessary. This question is relevant as, unlike other lawyers, prosecutors have a legal and ethical obligation not to win or seek conviction, but to work in the interest of justice[70]. In jurisdictions like Québec where the decision to charge someone is the prosecutor’s discretion, knowing whether Jordan has affected such a crucial decision or whether its effects seem limited only to more (or earlier) guilty pleas, could be a sign of such a punitive tilt.

Having examined the charge patterns and conducting a preliminary review of the breaches of conditions in quantitative terms, this next chart examines the breaches of types of conditions found in the administration of justice and sentencing offences. For the most part, these will be examined together, as the conditions tend to be quite similar. Recall that in the data, there were four individuals who were charged with both types of offences ; as the focus is on the conditions rather than the cases, the conditions breached on both sets of charges will be counted within this data. However, if multiple versions of the same charge occur in one information or one file (i.e., if the two charges are both for missing a meeting with their probation officer), the condition will only be counted once. The following chart demonstrates the different conditions, breaches for which individuals had been charged and for which the accused was present in court for their bail appearance[71].

The most frequent type of conditions breached were those which restrict the individual’s ability to move and access space. While these types of conditions vary, the most common ones were maintaining a radius of a certain distance between the accused and the domicile, work, and/or place of study of the victim or witness (12 breaches), and a prohibition against being in the physical presence of the victim or witness (11 breaches). All except one of the communications restrictions were prohibitions against communicating with the victim or witness. Most of these were complete prohibitions against communicating or attempting to communicate, but some left the option to communicate if the other person consented, and in two cases, for the purpose of exercising access rights for children which both the accused and the victim or witness are responsible.

A large proportion of the types of conditions breached were restrictions on substance consumption or possession. In most cases, the restriction was against alcohol, although in one case the condition stipulated abstinence from narcotics. In that particular case, the combination of charges was a breach of conditions (possession of a narcotic) and a criminal charge for the possession of cannabis ; both charges were punishable on summary conviction. Effectively, this person was being charged twice for the same behaviour.

The multiple-charges-for-same-behaviour phenomenon is also present in the cases wherein the accused person has been charged for both breach of bail conditions and breach of probation conditions, whether or not a criminal charge was also entered against them. This could also explain the consistency across some of these offences, of the number of commissions of sentencing and administration of justice offences.

3.4 Conditions of Release

As mentioned above, of the 45 cases discussed in this preceding analysis, 32 defendants representing 71.1 % of the population were detained. This section focuses on the 13 cases in which the accused was released and the conditions under which such release occurred.

The most common type of condition was spatial or mobility restrictions, which include limitations on the accused’s access to persons or places. In fact, given that 30 of these conditions placed on the 13 accused persons released, resulting in an average of 2.3 spatial or mobility restrictions on each accused. In almost all cases (11 out of 13), one such condition was to reside at an address and to inform the court in writing of any changes to the address ; this seemed to be a standard condition, like the requirement to keep the peace, be on good behavior, and attend court. In 11 out of 13 cases, at least one other spatial restriction existed, and usually involved maintaining a distance from other persons or places, or total prohibitions on accessing specific places without a tailored inquiry about whether this might be realistic for the individual. For example, one of the accused was prohibited from being on the premises of service stations. The prevalence of these restrictions supports the concerns raised by Sylvestre et al. regarding the impacts of such techniques on defendants, namely, the routinized approach to these conditions without consideration of their practical and individualized implications[72]. The other two most common conditions, aside from the above-described standard conditions, were prohibitions on owning or possessing weapons or imitations thereof which in some instances is a required condition per s. 515 (4.1) of the Criminal Code, or prohibitions on communication with victims/witnesses.

Table 5

Type and frequency of conditions of release per accused released

In relation to the earlier analysis of the conditions breached, a concerning pattern emerges. Of those 13 defendants released, in 11 cases at least one of their charges had been a breach of a condition identical to one to which the person was again subjected to upon release. Nine of these were breaches of spatial restrictions ; the tenth was a prohibition on consuming or possessing alcohol. Of the three cases where this was not the case, one accused breached a prohibition on communication and while he was not subjected to it on release, he still received multiple spatial/mobility restrictions which included maintaining a radius from the victim, and a curfew. In the remaining two cases, the breaches were of possessing a narcotic and of possessing a cellphone, and co-occurred with offences under the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act. In 11 of these cases, the offences were administration of justice offences rather than sentencing offences. Although more research would be useful, this pattern nonetheless suggests that creating criminal offences out of breaches of conditions may not be effective in encouraging compliance.

4 Discussion

Scholars have characterised the judiciary and law enforcement as risk-averse[73] ; this section complements this characterisation by focusing on punitive practices such as charge pile-ups of administration of justice offences and misguided as well as untailored restrictions imposed on individual freedoms in response to a formal accusation of criminal activity. Such restrictions ultimately lead to increased criminal charges for breaches of conditions related to activities otherwise not criminal, thus restricting the liberty of the person subject to conditions prior to a finding of guilt on the originating charge. Furthermore, if the charge results in a conviction, the person will be subjected to criminal punishment and the conviction will create or contribute to the individual’s criminal record.

Contrary to their stated objectives, bail reforms increased the complexity of cases, requiring more time and dates in court to resolve all matters related to the defendant[74]. This also leads to greater punitiveness as individuals are within the system’s control for longer and can be subject to punishment at multiple stages.

4.1 Punitiveness and Charge “Pile-ups” by Law Enforcement

A “piling on” of charges can be observed in cases where more than one set of charges is applied to the same person. Recall that per Table 3, sentencing and administration of justice offences are more frequently charged alongside either each other or alongside another criminal offence, than these offences are charged alone. This pattern is important for a few reasons. First, the actions involved in the charges for breach of conditions are often either similar or intrinsically related to the charges for other types of criminal offences. The starkest example of this outcome is one of the defendants, who was charged under s. 4 (1) (5) of the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act for possession of cannabis, and under s. 145 (3) b) of the Criminal Code for breaching a condition prohibiting him from possessing or using any narcotic (cannabis) without a medical order.

This practice was also repeated in a few cases in which the accused was charged with harassment offences such as s. 372 (3) (4) b) (repeated communication with intent to harassment by means of telecommunications) or s. 264 (1) (3) b) (harassment causing a person to fear for their safety or the safety of anyone around them by engaging in conduct including repeatedly following, communicating, observing their dwelling-house, or threatening) of the Criminal Code alongside s. 145 (3) b) for breaches of communication prohibitions. A notable example occurred at a bail appearance where an individual was charged with indictable offences of harassment by threatening to cause bodily harm or death (s. 264.1 (1) a) (2) a)) and of breach of a probation order to engage in no communication whatsoever with the victim (s. 733 (1) a)). During the hearing regarding his release, it was revealed that his previous conviction had to do with the same victim, who was named in the informations laid for both charges. The condition — no communication — in practical terms is covered by the harassment charge as harassment is an inherently communicative act. To charge the person with both is redundant and leads to a similar situation as charging a person for multiple breaches.

Although within criminal law these offences are separate, in practice, the same activity is criminalised twice. These double charges for the same act suggest that the criminalization of breaches is meant to be a form of retribution by signalling censure for disrespecting the justice system in addition to simply sanctioning the offending behaviour as a breach of, in the above example, the Criminal Code’s harassment provisions. These patterns reflect the punitive and retributive tendencies on the ground, particularly the ways that prosecutors and police officers use their discretionary functions to contribute to the multiplicity of administration of justice offences. The accused person becomes the scapegoat for two parallel breaches of the social order : both because the act was considered a priori criminal, and for disobedience of a court order.

4.2 Administration of Justice Offences, Conditions, and Breaches : Punitiveness by the Courts

The data also reflects the Montréal seat of the Court of Québec’s tendency to adopt supervisory functions in the administering of bail conditions. This characterisation lends support to existing research that suggests that imposing conditions for release binds the individual defendant to the court until the resolution of their process[75]. As seen above in Table 5, the accused is frequently subject to multiple conditions with a variety of effects which allow the court to monitor a broad swath of the lives of the accused and restrict his freedoms despite the presumption of innocence.

Breaches of such conditions return the accused persons to the court despite the inherent difficulties and impracticalities of abiding by these conditions, as discussed by Sylvestre et al. and by Berger regarding spatial restrictions and substance consumption prohibitions, respectively. Conditions aimed at breaking addictions notably through prohibiting substance possession and consumption, although may be well intentioned, are fundamentally misguided, untailored to the individual and unrealistic, since they criminalise addiction, a mental illness, by transforming an effect of that illness — the consumption of the prohibited substance — into a criminal infraction through s. 145 (3)[76]. Of the types of conditions surveyed above, these conditions and their breach should be most concerning because mental illness is not a choice and therefore many of these conditions are often impossible for individuals to respect. Further, no inquiry was made during the process to determine whether the individual had an addiction. While it is certainly possible that in at least some cases the accused does not have a substance misuse or addiction problem, such as where the conditions only extend to a formal abstention of consuming or possessing alcohol without a concurrent treatment-based condition, this cannot account for all instances in which substance restrictions are employed. The criminal sanctioning of these types of condition breaches suggests that substance misuse or addiction are acts that society considers against the social order and thus require a sanction. Individual and tailored assessments are not important. Thus, individuals already caught up in the criminal justice system serve as scapegoats for these acts where they occur in contravention of a judicial order.

In this context, beyond the issues already raised regarding the punitive use of the administration of justice offences, breaches of conditions signal other problems regarding the efficacy of certain types of conditions. In the recent decision of Antic, the Supreme Court of Canada opined that judges should not second-guess lawyers although they retain discretion to reject joint applications brought before them[77]. However, the above-described patterns suggest that exercise of such discretion may be needed in order to confront these types of problems, particularly when no evidence about the necessity of conditions is provided by the prosecution.

A second notable outcome of the data is the overlap of multiple conditions of similar types, such that a single action breaches two or more conditions because two or more of the conditions applied to this person were nearly identical. These situations should be distinguished from the preceding discussion because, unlike situations in which an administration of justice of sentencing offence is charged with another criminal offence, charges relating to multiple breaches of conditions are only criminal acts insofar as they are prohibited in a judicial order. This was evident in the cases included in Table 3 in which both administration of justice and sentencing offences applied, and the offences were mostly breaches of conditions. One person for example, had two spatial restrictions in her conditions for judicial interim release that were nearly identical conditions to those which bound her to a recognisance pursuant to s. 811 of the Criminal Code[78]. She was charged with both offences (s. 145 (3) b) for breaches of her conditions of release and s. 811 b) for breach of a recognisance).

The overlap of conditions often occurs within the same set of conditions. For example, in six cases captured by Table 4, conditions prohibiting a person from being physically present near a victim or witness are included at the same time as maintaining a radius of several hundred meters from the domicile, place or work, and place of study of the same victim or witness, or in one case, a complete prohibition from the Island of Montréal. While on a technical level the two conditions cover two separate spheres of space, from a pragmatic standpoint, should someone breach that condition by presenting themselves immediately in front of the person from whom the condition is designed to grant space, outside or very near their home, is it necessary to charge the person for breaching both conditions ? Charging both lends support to the perception of judges and prosecutors that such breaches are an affront to the court itself and are thus deserving of more vigorous pursuit in the criminal justice system[79]. Moreover, this practice that is rooted in the bail process lends support to a constructivist understanding of these offences, namely that failure to obey a judicial order is itself an act that requires sanctioning to re-establish social order. However, this response contributes to a glut of administration of justice offences in the criminal justice system.

This pattern suggests that this occurs by rote ; a condition was placed on release, it was breached, the person was released again with the same conditions on which an accused would normally be released in a similar situation. Indeed, the fact that these conditions are inefficient does not seem to be accounted for, which should be concerning if the actual goal of criminalising such breaches was to ensure compliance.

Further, this pattern reinforces allegations that defendants are being set up to fail at the bail stage and that administration of justice offences are taking up an inordinate amount of court time. The seriousness and widespread nature of this problem was noted in a recent Senate report on judicial delays, which recommended reducing court time spent on these offences and developing alternative means of dealing with them[80]. As mentioned above, Jordan should be considered here as it impacts bail hearings and administration of justice offences prosecution, given the link between the relatively high prosecution rates of these offences and their role in producing judicial delays. In addition to potentially increasing the number of guilty pleas, these delays also increase the time individuals are caught up within the system with restricted liberties that increase punitiveness.

From a sociological perspective, these patterns are not surprising, Since the function of bail can be understood as a mechanism that serves to establish social order through punishment by annihilating an act in the eyes of society, it is not surprising to see several patterns of punitiveness that relate to the bail process and are not tailored to the individual.

4.3 Understanding the Social Function of Punitiveness : a Constructivist Approach to Bail Practices

Fauconnet’s sociological theory of punishment remains an important lens with which one can understand the social function of the bail process. Indeed, pre-trial release and administration of justice offences restrict freedoms and operate before any formal findings of guilt or innocence are made but after a crime is committed ; the strictness of the conditions giving rise to administration of justice offences lend support to the notion that the maintenance of social order in response to an act rather than an individual. Several elements identified in this research on bail align with Fauconnet’s theory. According to his two-step process, responsibility is attributed during bail right after a crime is committed : a person is forcefully and rapidly subjected to state control and appears in public before a judge to discuss the various degrees of which his liberties will be restricted. This almost immediate punishment can vary in length and degrees as suggested by the ladder approach in Canadian law, ranging from conditions of release up to detention. Upon release, conditions restrict the individual’s freedoms and in some situations are impossible to respect. If breached, they transform into offences, even if normally this behaviour is not an offence, and even before liability for the initial offence is settled. This punitive process highlights the constructivist nature of crime and suggests that it operates on the basis that expedited and immediate sanction for crimes are necessary as it serves as a collective response to address crime rather than advancing actual liability.

Furthermore, as seen throughout this study, the fact that judges impose conditions for release that are not tailored to the individual furthers the claim that this process serves as a response to acts against the social order and that the individual is used as a scapegoat to advance this societal aim. In other words, difficulties or impracticalities of abiding by conditions of release, particularly with regard to spatial restrictions and substance consumption prohibitions, target certain actions rather than individual liability and agency. This enables a better understanding of the bail process’ punitive function in order to achieve social order.

Conclusion

This paper achieves three main goals : first, it contributes to the existing literature and frameworks for studying bail and administration of justice offences by providing data and analysis from an underexplored jurisdiction, namely Québec. Second, it demonstrates that the bail process and its implementation within the criminal justice system contributes to punitiveness through the over-criminalisation of individual offenders, which is by extension contributing to other problems in processing criminal justice, notably the increasing rate of remand. In principle, the Criminal Code and the Charter appear to provide robust guarantees of the right to bail and the presumption of innocence. However, practices on the ground complicate the attainment of pre-trial release, and favour re-entry into the criminal process. The existing literature on bail and remand provides useful frameworks with which to analyse the situation in Québec. Indeed, it suggests that the process can be characterized as risk-averse as an extra-legal justification for conditions and approaches to these types of offences, particularly as actors within the system, especially judges, police, prosecutors and judges, are continuously submitting individuals to multiple conditions that result in more breaches.

Third, the research presented in this paper complements these existing extra-legal justifications for understanding the bail process and the relevant actors’ interactions within it, by arguing that this process can also be characterized as punitive and retributive as a way to quickly guarantee the restoration of social order that was troubled by the act.

The data in this study supports the conclusion that punitiveness is a defining and systemic feature of the bail process. Punitiveness is present throughout ; from the decision to charge an individual with a multiplicity of similar charges for the same events, through the conditions which are ultimately breached, and prospectively in the conditions imposed should an accused person be released again. This includes the exercise of discretion to charge individuals with certain combinations of offences which in practice criminalise mental illness or result in multiple charges being applied to effectively the same actions, and the consequent piling on of charges against a single individual for a single act or status of being are some examples. Not only does this create delays for individuals, it also affects the system as a whole by creating longer periods of state control over individuals as well as state opportunities for similar charge patterns. Effectively, this creates greater spaces for punishment even if the individual is not guilty of the initial offence. There is the option to not charge an individual when the interests of justice would not be served ; yet the continual emphasis on adjudicating increasingly complicated cases and simply processing these cases more swiftly suggests that the process facilitates systemic punitiveness. Although this may seem contrary to the interests of justice and the presumption of innocence, Fauconnet’s theory of punishment sheds light on how this process can serve to target and respond to crime by focusing on the act that has troubled the social order rather than the individual responsible for the crime. In this sense, actual individual liability and guilt is peripheral and the emphasis is placed on a quick social response to the act by selecting a scapegoat who will bear the burden of guaranteed and expedited punishment.

Parties annexes

Notes

-

[1]

Cheryl Marie Webster, Anthony N. Doob and Nicole M. Myers, “The Parable of Ms. Baker : Understanding Pre-trial Detention in Canada”, (2009) 21 Current Issues Crim. Just. 79, 90.

-

[2]

To clarify : administration of justice offences are those which occur at Part IV of the Criminal Code, R.S.C. 1985, c. C-46 (“Offences Against the Administration of Law and Justice”) ; for the purposes of this paper, failure to comply with a condition of an undertaking or recognizance found at s. 145 (3) is the most relevant. Sentencing offences are found in Part XXIII of the Code (“Sentencing”). Chief among the infractions of this section are failure to comply with a probation order (s. 733.1) and breach of a recognizance (s. 811). In all of these cases, the offence may be charged as a summary or indictable offence and can be punished by imprisonment.

-

[3]

Paul Fauconnet, La responsabilité. Étude de sociologie, Paris, Librairie Félix Alcan, 1928.

-

[4]

For clarity, the law terms the bail process as “judicial interim release” with or without conditions. However, as common parlance uses the language of “bail”, that will be used in this paper.

-

[5]

Canadian Committee on Corrections, Toward Unity : Criminal Justice and Corrections, Ottawa, Queen’s Printer, 1969, p. 100 and 103 (hereafter “Toward Unity”).

-

[6]

Martin L. Friedland, Detention before Trial : A Study of Criminal Cases Tried in the Toronto Magistrates’ Courts, Toronto, University of Toronto Press, 1965.

-

[7]

Toward Unity, supra, note 5, p. 112 and 113.

-

[8]

Canada, Report of the Royal Commission to Investigate the Penal System of Canada, Ottawa, Printer to the King’s Most Excellent Majesty, 1938, p. 354 and 361.

-

[9]

Bail Reform Act, S.C. 1970-71-72, c. 37.

-

[10]

Canadian Civil Liberties Association and Education Trust, “Set Up To Fail : Bail and the Revolving Door of Pre-trial Detention”, 2014, p. 15, [Online], [ccla.org/dev/v5/_doc/CCLA_set_up_to_fail.pdf] (February 19th, 2019) (hereafter “CCLA”).

-

[11]

Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, Part I of the Constitution Act, 1982, [Schedule B to the Canada Act 1982, 1982, c. 11 (U.K.)].

-

[12]

CCLA, supra, note 10, p. 5. See also C.M. Webster, A.N. Doob and N.M. Myers, supra, note 1 ; Michael Weinrath, “Inmate Perspectives on the Remand Crisis in Canada”, (2009) 51 Canadian J. Criminology & Crim. Just. 355.

-

[13]

CCLA, supra, note 10, p. 1 ; Lindsay Porter and Donna Calverley, “Trends in the use of remand in Canada”, Juristat, Statistics Canada catalogue no 85-002-X, 2011, p. 6 ; See also C.M. Webster, A.N. Doob and N.M. Myers, supra, note 1, 82.

-

[14]

Jane B. Sprott, “The Persistence of Status Offences in the Youth Justice System”, (2012) 54 Canadian J. Criminology & Crim. Just. 309, 321-324 ; C.M. Webster, A.N. Doob and N.M. Myers, supra, note 1, 91 ; Jane B. Sprott and Jessica Sutherland, “Unintended Consequences of Multiple Bail Conditions for Youth”, (2015) 57 Canadian J. Criminology & Crim. Just. 59, 62 and 63 ; M. Weinrath, supra, note 12, 359.

-

[15]

Marta Burczycka and Christopher Munch, “Trends in Offences Against the Administration of Justice”, Juristat, Statistics Canada catalogue no 85-002-X, 2015, p. 3.

-

[16]

See, for example, M. Weinrath, supra, note 12 ; J.B. Sprott, supra, note 14 ; and Voula Marinos, “The Meaning of ‘Short’ Sentences of Imprisonment and Offences Against the Administration of Justice : A Perspective from the Court”, (2006) 21 Can. J.L. & Soc. 143, 157.

-

[17]

CCLA, supra, note 10, p. 1. See also J.B. Sprott, supra, note 14, 318.

-

[18]

Fernanda Prates and Marion Vacheret, “La décision policière”, in Marion Vacheret and Fernanda Prates (eds.), La détention avant jugement au Canada. Une pratique controversée, Montréal, Les Presses de l’Université de Montréal, 2015, p. 49 ; Vicki Labelle and Françoise Vanhamme, “Les risques du métier de procureur”, in M. Vacheret and F. Prates (eds.), p. 65 ; and Françoise Vanhamme, “Les conditions judiciaires du maintien en liberté”, in M. Vacheret and F. Prates (eds.), p. 83.

-

[19]

Peter Harris and others, “Working ‘In the Trenches’ with the YCJA”, (2004) 46 Canadian J. Criminology & Crim. Just. 367, 374.

-

[20]

See J.B. Sprott and J. Sutherland, supra, note 14, 61 and V. Marinos, supra, note 16, 157.

-

[21]

F. Prates and M. Vacheret, supra, note 18, at page 51.

-

[22]

J.B. Sprott, supra, note 14, 327. A similar effect was observed in youth bail hearings presided over by justices of the peace (not youth court) : Nicole M. Myers and Sunny Dhillon, “The Criminal Offence of Entering Any Shoppers Drug Mart in Ontario : Criminalizing Ordinary Behaviour in Youth Bail Conditions”, (2013) 55 Canadian J. Criminology & Crim. Just. 187.

-

[23]

C.M. Webster, A.N. Doob and N.M. Myers, supra, note 1, 91.

-

[24]

Id., 92, 93 and 95.

-

[25]

Statistics Canada, “Adult criminal courts, number of cases and charges by type of decision”, [Online], [www5.statcan.gc.ca/cansim/a26?lang=eng&id=2520053] (December 27th, 2017) (Authors’ calculations).

-

[26]

Id.

-

[27]

Nicole Marie Myers, “Eroding the Presumption of Innocence : Pre-trial Detention and the Use of Conditional Release on Bail”, (2017) 57 British Journal of Criminology 664, 674.

-

[28]

M. Weinrath, supra, note 12, 367, 370 and 373.

-

[29]

Marion Vacheret and Virginie Brassard, “Le vécu des justiciables”, in M. Vacheret and F. Prates (eds.), supra, note 18, p. 125.

-

[30]

Marie-Eve Sylvestre and others, “Spatial Tactics in Criminal Courts and the Politics of Legal Technicalities”, Antipode, vol. 47, no 5, 2015, p. 1346.

-

[31]

Id., at page 1359.

-

[32]

J.B. Sprott, supra, note 14, 21 and J.B. Sprott and J. Sutherland, supra, note 14.

-

[33]

CCLA, supra, note 10, p. 2 and 4.

-

[34]

M.-E. Sylvestre and others, supra, note 30, at page 1359.

-

[35]

Id.

-

[36]

Roger Matthews, “The Myth of Punitiveness”, Theoretical Criminology, vol. 9, 2005, p. 175, at page 178.

-

[37]

Stanley Cohen, “Social Control and the Politics of Reconstruction”, in David Nelken (ed.), The Futures of Criminology, London, SAGE Publications, 1994, p. 63, at pages 67 and 68.

-

[38]

Stanley Cohen, “Social-Control Talk : Telling Stories about Correctional Change”, in David Galand and Peter Young (eds.), The Power to Punish. Contemporary Penality and Social Analysis, New Jersey, Humanities Press, 1983, p. 101 ; Stanley Cohen, Visions of Social Control. Crime, Punishment and Classification, Cambridge, Polity Press, 1985.

-

[39]

Andrew Ashworth, “Is Restorative Justice the Way Forward for Criminal Justice ?”, in Eugene McLaughlin and others (eds.), Restorative Justice. Critical Issues, London, SAGE Publications, 2003, p. 164.

-

[40]

Malcolm Feeley and Jonathan Simon, “Actuarial Justice : The Emerging New Criminal Law”, in D. Nelken (ed.), supra, note 37, p. 173, at page 185.

-

[41]

Id.

-

[42]

Jonathan Simon, Poor Discipline. Parole and the Social Control of the Underclass, 1890-1990, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1993.

-

[43]

Philippe Combessie’s theoretical syntheses of Durkeim, Fauconnet and Foucault’s theories have been useful. See Philippe Combessie, “Durkheim, Fauconnet et Foucault. Étayer une perspective abolitionniste à l’heure de la mondialisation des échanges”, in Marco Cicchini and Michel Porret (eds.), Les sphères du pénal avec Michel Foucault. Histoire et sociologie du droit de punir, Lausanne, Éditions Antipodes, 2007, p. 57. Philippe Combessie, “Paul Fauconnet et l’imputation pénale de la responsabilité”, in Claude Ravelet (ed.), Trois figures de l’école durkheimienne. Célestin Bouglé, Georges Davy, Paul Fauconnet, Paris, L’Harmattan, 2007, p. 221.

-

[44]

P. Combessie, “Paul Fauconnet et l’imputation pénale de la responsabilité”, supra, note 43, at page 226.

-

[45]

P. Fauconnet, supra, note 3, p. 232.

-

[46]

Id.

-

[47]

Id., p. 40.

-

[48]

Id., p. 280.

-

[49]

Id., p. 219.

-

[50]

P. Combessie, “Paul Fauconnet et l’imputation pénale de la responsabilité”, supra, note 43 ; P. Fauconnet, supra, note 3, p. 223.

-

[51]

Id.

-

[52]

P. Fauconnet, supra, note 3, p. 220.

-

[53]

Patrick Pharo, “How is Sociological Realism Possible ? Sociology after Cognitive Science”, European Journal of Social Theory, vol. 10, no 3, 2007, p. 481, at page 486.

-

[54]

Id.

-

[55]

W. Watts Miller, “Durkheim and Individualism”, The Sociological Review, vol. 36, no 4, 1988, p. 647.

-

[56]

P. Pharo, supra, note 53, at page 482.

-

[57]

Alexander Tristan Riley, “Durkheim contra Bergson ? The Hidden Roots of Postmodern Theory and the Postmodern ‘Return’ of the Sacred”, Sociological Perspectives, vol. 45, no 3, 2002, p. 243.

-

[58]

Nicole Marie Myers, “Who Said Anything about Justice ? Bail Court and the Culture of Adjournment”, (2015) 30 Can. J.L. & Soc. 127.

-

[59]

A hearing here is distinguished from an appearance by the fact that these hearings involved arguments by both defense and the Crown regarding judicial interim release and may include witness testimony as well. Most of the appearances observed lasted only a few minutes with the outcome presented to the judge by either the defense counsel or the Crown, and which the judge invariably accepted.

-

[60]

On direct observation research methods : Lee Ellis, Richard D. Hartley and Anthony Walsh, Research Methods in Criminal Justice and Criminology. An Interdisciplinary Approach, Plymouth, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2010.

-

[61]

In most cases, these offences amount to breaches of either conditions of release or conditions of probation, however this data set also includes one breach of s. 811 a) Criminal Code hence the more general term.

-

[62]

Except otherwise indicated, all calculations in this section were done by the authors.

-

[63]

For more information relating to the use of video in bail hearings, see Cheryl Marie Webster, “Out of Sight, Out of Mind : A Case Study of Bail Efficiency in an Ontario Video Remand Court”, (2009) 21 Current Issues Crim. Just. 103.

-

[64]

Except for one defendant, for whom only one file was accessible. Because of the process through which files were accessed, it is possible that when the files were searched for, they were consistently unavailable. According to the contact person working at the Salle des Dossiers, this may be because the cases are in court, or requested by the judge presiding over the case.

-

[65]

The mean was calculated in reference to the number of individuals with each type of charge combination.

-

[66]

As the information regarding administration of justice offences was unavailable for one individual falling into this category, the mean and range only reflect the five individuals for whom data was available in its entirety. The “Overall” was still calculated was for the full 45 cases.

-

[67]

M.-E. Sylvestre and others, supra, note 30.

-

[68]

This concern was raised in Kienapple v. R., [1975] 1 S.C.R. 729. More recently, broader concerns of abuse of police practices and democratic control of police were reviewed in Kent Roach, “Models of Civilian Police Review : The Objectives and Mechanisms of Legal and Political Regulation of the Police”, (2014) 61 Crim. L.Q. 29.

-

[69]

Briefly, the Jordan decision set strict limits on prosecutorial or institutional delays for cases at the provincial court and superior court levels – 18 months and 30 months, respectively. Any delays in excess are now presumptively unconstitutional justifying stays of proceedings, although prosecutors may rebut the presumption (R. v. Jordan, [2016] 1 S.C.R. 631, 2016 SCC 27).

-

[70]

See, for example, Code of Professional Conduct of Lawyers, CQLR, c. B-1, r. 3.1, s. 112 (for Québec) ; Law Society of Ontario, Rules of Professional Conduct, s. 5.1-3, [Online], [lso.ca/about-lso/legislation-rules/rules-of-professional-conduct] (February 21st, 2019).

-

[71]

Note the one instance of “missing data”. For this case, the only data available was the criminal offences for which he was charged.

-

[72]

See M.-E. Sylvestre and others, supra, note 30, at page 1359.

-

[73]

CCLA, supra, note 10, p. 1. See also J.B. Sprott, supra, note 14, 318.

-

[74]

CCLA, supra, note 10, p. 82.

-

[75]

Kelly Hannah-Moffat and Paula Maurutto, “Shifting and Targeted Forms of Penal Governance : Bail, Punishment and Specialized Courts”, Theoretical Criminology, vol. 16, 2012, p. 201.

-

[76]

Benjamin L. Berger, “Mental Disorder and the Instability of Blame in Criminal Law”, in François Tanguay-Renaud and James Stribopoulos (eds.), Rethinking Criminal Law Theory. New Canadian Perspectives in the Philosophy of Domestic, Transnational, and International Criminal Law, Oxford, Hart Publishing, 2012, p. 117 ; Kent Roach and Andrea Bailey, “The Relevance of Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder in Canadian Criminal Law From Investigation to Sentencing”, (2009) 42 U.B.C. L. Rev. 1. It is also worth noting that for substances which are already controlled or illegal, having a condition to not possess the substance is redundant since the person is already required by law not to do so through the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act, S.C. 1996, c. 19.

-

[77]

R. v. Antic, [2017] 1 S.C.R. 509, 2017 SCC 27, par. 68.

-

[78]

Criminal Code, s. 145 (3) b) offences were for breaching conditions requiring her to maintain a 200 meters distance from the victim’s domicile, place of work, and place of study, a prohibition against being in the victim’s physical presence, a prohibition against any communication whatsoever with the victim whether directly or indirectly, and a prohibition on consuming or possessing alcohol. The s. 811 b) offences were for breaching conditions indicating the same 200 meters distance and communications prohibitions, as well as a condition to maintain a 50-meter radius from the victim’s person.

-

[79]

V. Marinos, supra, note 16, 156 and 157.

-

[80]

Standing Senate Committee on Legal and Constitutional Affairs, “Delaying Justice is Denying Justice. An Urgent Need to Address Lengthy Court Delays in Canada”, Final Report, Ottawa, 2017, p. 141, [Online], [sencanada.ca/content/sen/committee/421/LCJC/reports/Court_Delays_Final_Report_e.pdf] (February 21st, 2019).

Liste des figures

Liste des tableaux

Table1

Percentages of types of criminal offence

Table 2

Accused Charge Combinations Numbers and Percentages of Detention and Release

Table 3

Number and Percentages of Criminal Offence Charges

Table 4

Number of Conditions Breached per Charge Combination[66]

Table 5

Type and frequency of conditions of release per accused released