Abstracts

Abstract

This paper presents an overview of the architectural remains associated with the Palaeoeskimo occupations of the Central Canadian Low Arctic. Palaeoeskimos inhabited this area for approximately 4,000 years which have be divided by archeologists have identified nine chrono-cultural periods: Early Palaeoeskimo (Pre-Dorset, Transitional Pre-Dorset/Dorset, Lagoon, and Groswater) and Late Palaeoeskimo (Early, Middle, Late, and Terminal Dorset, as well as Choris). While the validity of these divisions remains contentious, research throughout the region has documented significant architectural variability within and between these cultural groups. This paper proposes a typological system for the description and organization of the architectural remains currently reported in order to facilitate renewed discussion of the underlying causes of Palaeoeskimo architectural variability.

Résumé

Cet article présente une synthèse des vestiges architecturaux paléoesquimaux du Bas Arctique central canadien. Les Paléoesquimaux habitèrent cette région pendant environ 4 000 ans découpés par les archéologues en neuf périodes chrono-culturelles: le Paléoesquimau ancien (Prédorsétien, Transition prédorsétienne/dorsétienne, Lagoon et Groswatérien) et le Paléoesquimau récent (Dorsétien ancien, moyen, récent et terminal, ainsi que le Choris). Bien que la validité de ces divisions reste contentieuse, les recherches dans cette région ont documenté une importante variabilité architecturale parmis ces groupes culturels. Cet article propose un système typologique décrivant et organisant les vestiges architecturaux signalés jusqu'à ce jour afin de susciter de nouvelles discussions concernant les causes de la variabilité architecturale paléoesquimaude.

Article body

Introduction

It has been almost 80 years since Diamond Jenness (1925) argued for cultural separation of Dorset from Thule and 50 years since Deric O'Bryan (1953) published the first article describing Dorset architecture. Since then, work in Alaska has defined both the Arctic Small Tool tradition (Irving 1957) and the Denbigh Flint Complex (Giddings 1964), confirming Steensby's (1916) suggestion that a population, which he termed "paleo-eskimo," had occupied the Arctic prior to the era of Inuit occupation. Steensby (1916: 200-201) observed that Palaeoeskimo structures included summer tents, snowhouses, and "earth-tents," but not the robust sod and whalebone houses of the Inuit period.

In this paper, I will synthesize the Palaeoeskimo architectural information gathered from the Central Canadian Low Arctic since Steensby's initial observations, so that a comprehensive database of the architectural forms associated with each time period across the region can be created. For the purposes of this paper, the Central Canadian Low Arctic is defined as the area south of Parry Channel, including Banks and Victoria Islands to the west, Baffin Island (excluding the extreme north, considered part of the High Arctic in this volume) and Nunavik to the east, and the Hudson Bay coast to the south (Figure 1). The Palaeoeskimo groups reviewed include Pre-Dorset (4500-2800 B.P.), Transitional Pre-Dorset/Dorset, Lagoon, Groswater (2800-2300 B.P.), and Early, Middle, Late, and Terminal Dorset (2500-500 B.P.)[1]. While the culture-historical relationship of Pre-Dorset and Dorset is questioned (Nagy 1994), as are some aspects of Terminal Dorset (Maxwell 1985: 239-245), the basic cultural framework of human occupation in the region has been established and I make no attempt to refine the chrono-cultural framework in this paper.

It should not be surprising given the lengthy period of Palaeoeskimo occupation of the Central Canadian Low Arctic that a large and diverse database of architectural information has now been gathered. However, it is this very architectural diversity, coupled with the disparate venues in which these remains have been reported, that has discouraged the large-scale comparison of structures within and between geographic areas and cultural periods. For this reason, the primary purpose of this paper is to bring this large body of information together in a comprehensive synthesis that also functions as a useful comparative and classificatory tool for researchers. To this end, a typology of dwellings based on a number of variables and attributes (discussed more fully later in this paper) is proposed to classify the full range of architectural styles thus far reported. This typology follows the advice of Adams and Adams (1991: 76-90), who note that practical typologies should only define types for which actual examples occur, while excluding from consideration types that may potentially exist but for which no examples have been found. This does not mean that future archaeological work will not necessitate the expansion or refinement of the classification proposed, simply that the types outlined herein are designed for existing documented structures.

Figure 1

Map of the Central Canadian Low Arctic

The typological construct

Despite the fact that no standard method has been agreed upon for the development of typologies (Banning 2000: 53), they can be useful tools for the organization and description of diverse material culture remains. Typologies are also advantageous in that they can present large amounts of information in a concise and easily digestible format. As such, typological classification is viewed in this paper as a necessary first step that orders data into mutually exclusive types. Only after the types have been defined can researchers move to address more detailed explanatory questions (contra, Fritz and Plog 1970: 407-408). Therefore, the primary aim of this paper is to produce a typology which will provide a practical and useful descriptive tool for the comparison of architectural forms across the Central Canadian Low Arctic, without seeking to explain this variability in terms of considerations such as mobility, seasonality, or social factors.

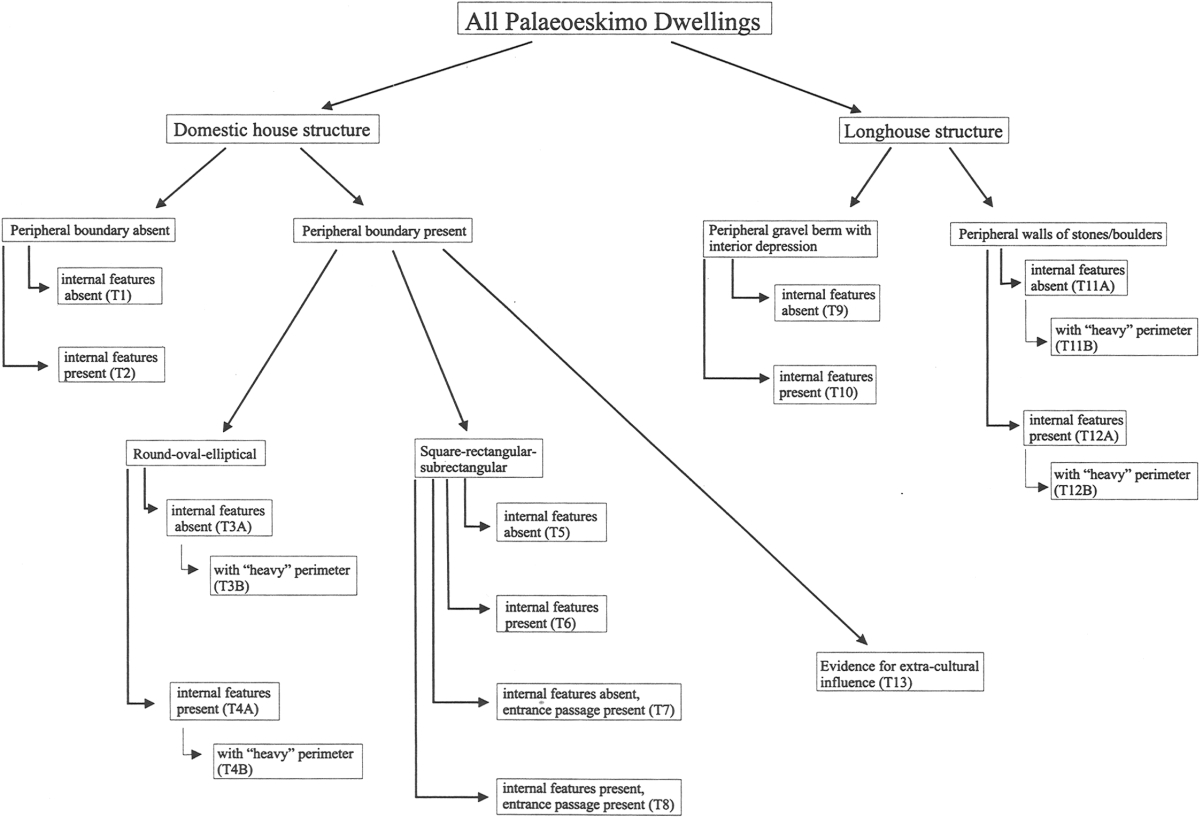

The typological technique used in this paper is referred to as a "tree" method, which is based primarily on the concept of association analysis (Whallon 1972). Association analysis operates via a qualitative presence/absence examination of a variable's attributes, where the attributes of a particular variable determine the order in which the remaining variables are to be examined (Whallon 1972: 15). Adams and Adams (1991: 170) describe variables as "dimensions of variability" that are largely independent of one another and are identifiable in some form in all of the types constituting a typology (variables can be expressed by being absent). In comparison, attributes refer to differences within individually defined variables and are interdependent in that only one attribute of a variable can be present at any time, a concept referred to as "mutual exclusivity" (Adams and Adams 1991: 172-173). Attributes, unlike variables, are further connected in that the identification of one attribute may necessitate the presence of a particular attribute in a separate variable (Adams and Adams 1991: 171-174).

Type divisions are thus made based on the presence or absence of characteristic attributes, resulting in the grouping of artefacts that are more similar to one another than they are to those placed within a separate type. In this way, tree typologies are monothetic in that they consider attributes on an individual basis, requiring that each artefact included in a particular type display all of the attributes used to define that type (Adams and Adams 1991: 226). The following section will outline the variables and attributes used to suggest an architectural typology of Palaeoeskimo structural remains.

Defining Palaeoeskimo structural types

As this typology was developed, a conscious effort was made to select variables whose attributes were easily identifiable and typically highly visible, could generally be assessed both in and out of the field through surface observation, and were clearly distinguishable so that unambiguous boundaries between types were made. This naturally limited the number of useful variables; however, those that remain are sufficient to create a meaningful typology for the description and analysis of Palaeoeskimo structures (Figure 2).

The first step in any typology is the identification of a base or invariant, which in this instance includes all of the reported Palaeoeskimo structures. From this starting point, division into discrete types is possible through the precepts of association analysis. Adhering to the procedural concept of tree typologies, these subsequent divisions are based on a series of sequential questions regarding the chosen variables and their attributes, the answers to which result in the production of types. Considering all Palaeoeskimo structures, the first question (and hence division) examines whether or not the architectural feature being considered is a longhouse or domestic structure. As discussed by Damkjar (2000: 170, 172-173, Figure 109), the two can be visually distinguished fairly easily given the huge dimension of longhouses (average length of 14 m) in comparison to the much smaller and generally more variable domestic structures. Using this distinction, the first typological subdivision of the larger invariant is accomplished and a framework is created within which the definition of types is made possible.

Beginning with the domestic structures, the first variable to be examined pertains to whether or not a peripheral boundary marker can be recognized. While acknowledging that such markers can be differentially expressed when present (forms include gravel or sod berms, groups of hold-down stones, or well-defined depressions), the attributes used for this variable have been simplified to either peripheral boundary marker absent or peripheral boundary marker present. If inspection of this variable results in a negative result (no marker identified) and the localized distribution of vegetation and/or artefacts are the only available indicators for a former structure, analysis must then move to examine the next variable; internal features. As with peripheral boundary markers, the occurrence of specific internal features can be quite mutable and may include traits such as pavements, axial features, hearths, storage features, or a variety of architecturally defined activity areas (which can occur either individually or in combination). However, for organizational purposes, a simplified presence/absence evaluation of internal features is believed sufficient for continued subdivision. Assessing the attributes of these two variables thus leads to the definition of the first two proposed structural types: Type 1, including those structures for which both peripheral boundary markers and internal features are absent; and Type 2 structures, which lack peripheral boundaries but contain some kind of internal feature(s)[2].

Moving next to those domestic structures for which a peripheral boundary marker can be identified, the first question relates to the variable of dwelling shape. Two attributes, round/oval/elliptical and square/rectangular/subrectangular, are recognized as useful characteristics for the continued subdivision of the Palaeoeskimo structures into types (as will be discussed later in this paper, this trait has previously been acknowledged [e.g., Maxwell 1985: 123] as a potentially significant criterion). Once the shape of the structure has been determined, analysis should then proceed to an examination of whether internal features are or are not present. Structures with a round/oval/elliptical shape and no recognized internal features will be identified as Type 3A, with a subtype (Type 3B) for those few previously reported structures described as possessing a so-called "heavy" perimeter[3]. Round/oval/elliptical structures containing some form of internal features are subdivided into Type 4A or Type 4B ("heavy" perimeter).

Figure 2

Proposed typology (tree format) of Palaeoeskimo structural types

Structures with square/rectangular/subrectangular peripheral markers are grouped on a separate typological branch from the round/oval/elliptical-shaped dwellings (Figure 2). Those without internal features are identified as Type 5, while those with internal features are labelled as Type 6. Two final square/rectangular/subrectangular structural types, Type 7 and Type 8, have been defined on the basis of their entrance passages. These entrance passages are distinct from the inferred entryways, typified by a break in the peripheral boundary marker, sometimes recognized with structures placed in other types. Instead, entrance passages, which can vary somewhat in construction details (particularly concerning their lengths and the incorporation of cold-traps), are manifested as architecturally distinct additions that appear to represent a significant architectural development in the Palaeoeskimo structural repertoire. In terms of classification, Type 7 dwellings are characterized as square/rectangular/subrectangular structures that lack internal features but include an entrance passage of some form. Type 8 structures are comparable to Type 7 structures, except they also contain evidence of internal features.

Turning from the domestic structures to the longhouse structures, four architectural types are proposed to cover the known forms in the Central Canadian Low Arctic. Unlike those dwelling structures lacking a definable periphery boundary marker, all reported longhouses have clearly demarcated boundaries, either in the form of low gravel berms with associated internal depressions, or lines of boulders and stones (Damkjar 2000: 173). Given peripheral boundary markers are a universal of these structures, a simple presence/absence criterion (as was used for the domestic structures) is not sufficient. For this reason, the classification of longhouse structures will use as its first variable the kind of peripheral boundary marker present, either peripheral gravel berm with interior depression, or peripheral wall of boulders/stones. Taking first those structures described as having gravel berms and internal depressions, two types can be suggested on the basis of whether or not internal features are identifiable. If internal features are absent, the structure will be designated as Type 9. If internal features are present, the structure will be classified as a Type 10 structure.

Two structural types, each with subtypes for structures designated as having "heavy" peripheral boundary markers, have been defined for those longhouses defined by a peripheral wall of boulders or stones. Those examples lacking internal features are classified as Type 11A, or Type 11B ("heavy" peripheral markers). In cases where internal features are identified (these include the range of features mentioned previously for domestic structures, as well as small compartments built into or against the peripheral walls [see Damkjar 2000: 173]), structures are classified as Type 12A, or Type 12B ("heavy").

The final Palaeoeskimo structural type to be defined, Type 13, represents an amorphous mixture of Late Palaeoeskimo domestic structures for which investigators have, based on architectural and artefactual evidence, suggested extra-cultural influences. Architectural features generally thought to indicate such influences include the incorporation of moderate amounts of bowhead whale skeletal elements in the superstructure, rear raised sleeping platforms, kitchen alcoves, and lintel stones (to be discussed later, but see Plumet 1979; Wenzel 1979). It would seem, based on the excavation reports of Type 13 structures, that assignment to this architectural type is possible only after such remains have been excavated (initial inspection of Type 13 structures has typically resulted in their identification as Thule rather than Palaeoeskimo).

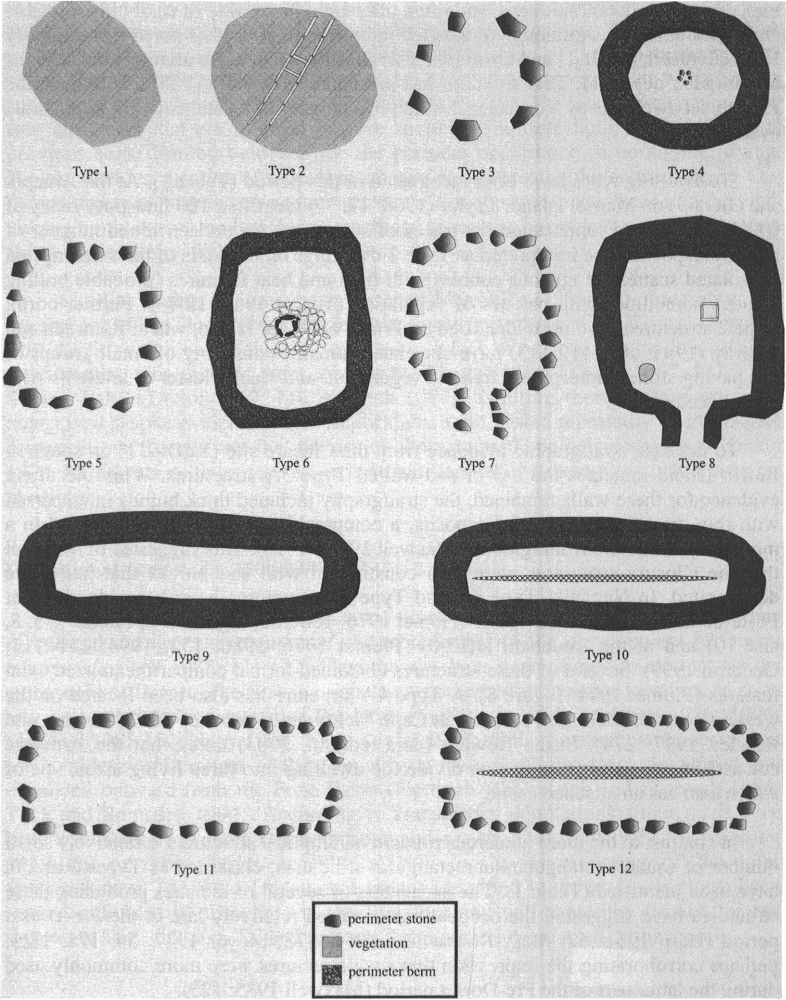

As defined, the 13 proposed types comprising this typology of Palaeoeskimo structures encompass all of the architectural variability thus far reported from the study area. Each type involves a degree of internal variability, although each is composed of examples that all share a combination of attributes making them unique to that type. As Adams and Adams (1991: 195) have noted, "type descriptions necessarily refer to an idealized conception of the type," meaning that in "most archaeological classifications the perfect type specimen is probably more the exception than the rule." Bearing this in mind, Figure 3 illustrates a theoretical example of each of the architectural types, although again it should be stated that each type involves more variability than can be shown in a single figure (particularly concerning the manner in which the peripheral boundary markers and internal features are manifested).

As will become apparent as discussion moves to consider the structural types associated with specific cultural groups, most of the defined types are present in multiple periods. Possible reasons for this will not be explicitly discussed as it is beyond the scope of this paper, although it is probable that the co-occurrence of multiple structural types within single periods, as well as the reoccurrence of types through time, can be explained, at least in part, by factors including the availability of construction materials, social and cultural traditions, and the influence of seasonal and other physical constraints. It is hoped that this typology will provide a descriptive and organizational framework within which renewed discussion of the Palaeoeskimo social space can be situated.

Pre-Dorset (ca. 4500-2800 B.P.)

The Pre-Dorset are the earliest Palaeoeskimo population in the Low Arctic, arriving ca. 4500 B.P. (Savelle and Dyke 2002). By all accounts, this migration occurred rapidly (Bielawski 1982: 41; Maxwell 1984: 359; McGhee 1996: 73; Murray and Ramsden n.d.), indicating a highly mobile population that occupied individual sites for short periods. A frequent result of this strategy is that sites tend to be small, rarely have significant middens, and often offer little in the way of easily interpretable architectural remains (although S. Rowley [pers comm. 2003] has noted that the Parry Hill/Kaleruserk [NiHf-1] and Lyon [NiHf-2] sites have extensive architectural remains and midden deposits). This situation has prompted Maxwell (1985: 96) to describe Pre-Dorset dwellings as "confusing," which in a number of locations is still an accurate evaluation.

Figure 3

Representations of the proposed Palaeoeskimo structural types. Each illustration depicts one of several ways in which a specific type can be manifested, depending upon the form of the peripheral boundary marker and internal features (individual structures are not to scale). Type 13 is not illustrated given its highly variable nature.

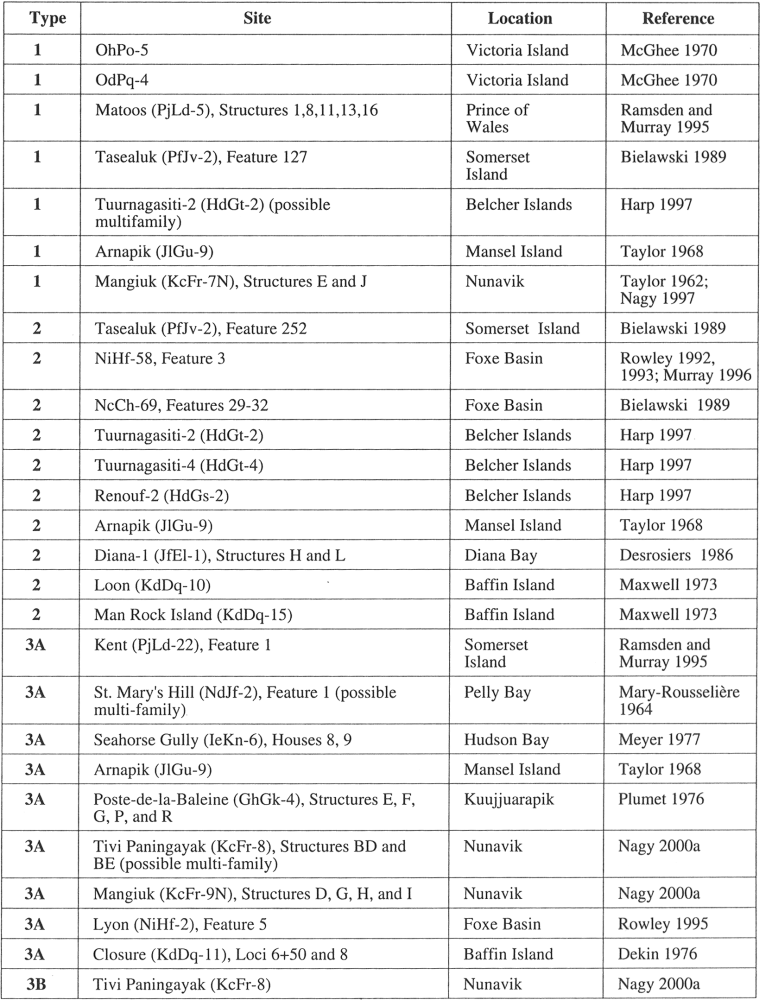

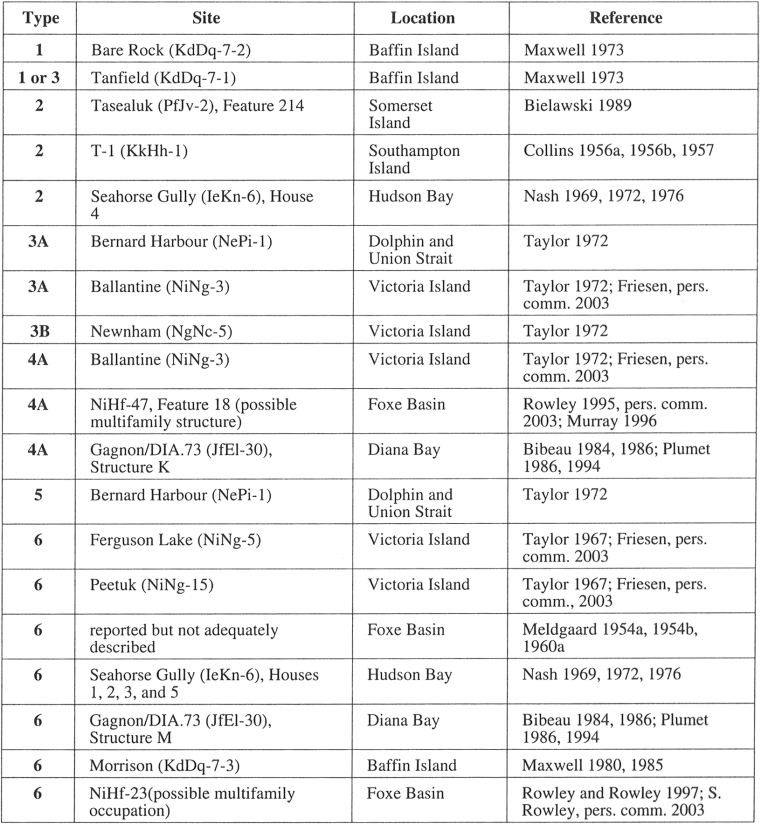

Six dwelling types have been recognized in this period (Table 1). At the Arnapik site (JlGu-9) on Mansel Island, Taylor (1968: 12, 39) identified 120 findspots, many of which he believed represented the traces of structures. An undetermined number of these findspots can be interpreted as Type 1 dwellings on the basis of their description as isolated scatters of igneous cobbles with frost and heat fractures (probable boiling stones), sometimes with patches of vegetation (Taylor 1968: 12-14). Further north, Type 2 structures have been identified on Prince of Wales Island, where Ramsden and Murray (1995: 109, 112-113) have correlated remains consisting of small groups of flat paving stones, amorphous areas of vegetation, and small cluster of artefacts with winter occupations.

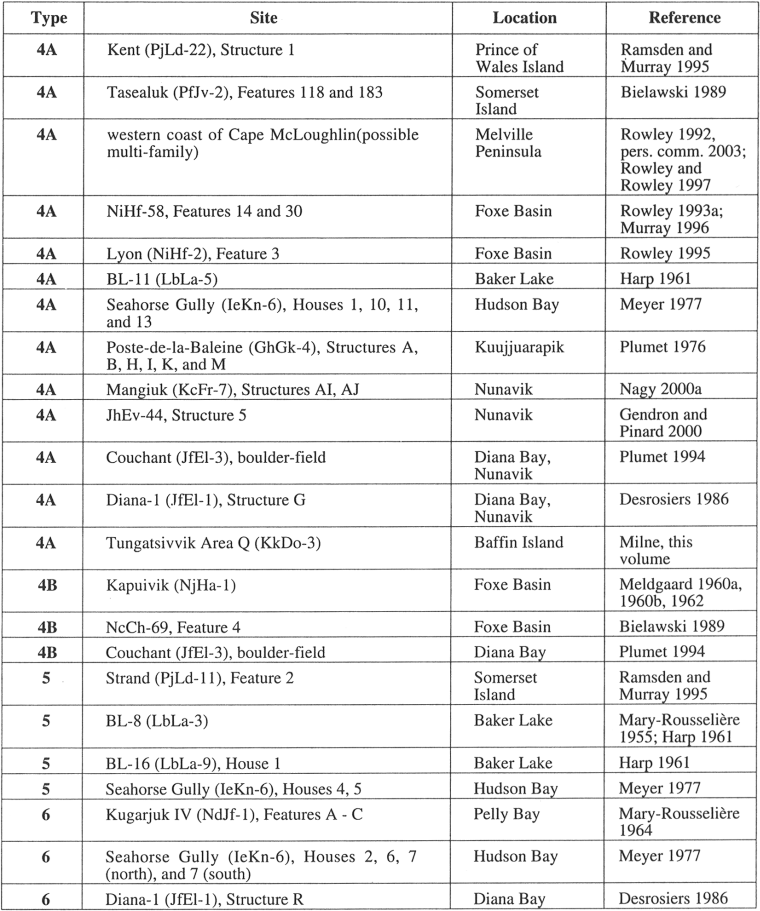

To the east, stratigraphic evidence from the Closure site (KdDq-11) on southern Baffin Island indicates the use of sod-walled Type 3A structures. While no direct evidence for these walls remained, the stratigraphy included thick humus interspersed with thin discontinuous gravel deposits, a comparable pattern to that recorded in a modern sod structure from Igloolik (Maxwell 1976: 75-76). This suggested to Maxwell that the Closure structures were also constructed with sod blocks that had since deteriorated. In Nunavik, Type 4A and Type 4B structures have been identified at Poste-de-la-Baleine (GhGk-4) site (Plumet 1976: 180-183, Figures 5-7, Photos 3, 5, 8, and 10) and at the Couchant (JfEl-3) (Plumet 1976, 1986: 152, 1994: 111–113; Gendron 1999). Several of these structures contained formal compartmentalized axial features (Plumet 1994: Figure 8). A Type 4A structure has also been located on the western coast of Melville Peninsula at Cape McLoughlin (Rowley 1992; Rowley and Rowley 1997: 274). Susan Rowley (pers. comm., 2003) notes that the structure consists of two axial features that divide the dwelling into three living areas, one of which also has an attached cache.

In contrast to the more numerous round/oval/elliptical structures, a relatively small number of square/rectangular/subrectangular structures, classified as Types 5 and 6, have been identified (Table 1). The excavators of several of the sites producing these structures have suggested the occupations occurred relatively late in the Pre-Dorset period (Harp 1961: 52; Mary-Rousselière 1964: 178; Meyer 1977: 54, 178, 186), perhaps corroborating the impression that such structures were more commonly used during the latter part of the Pre-Dorset period (Maxwell 1985: 123).

Pre-Dorset summary

Pre-Dorset in the study area utilized a wide variety of structural types that are undoubtedly related to a number of considerations including season of use and mobility strategies. Ramsden and Murray (1995: 112-115) have previously observed that at least some structures that lack peripheral boundary markers (Types 1 and 2) are probably the remains of winter snowhouses, while some of the structures with so-called "heavy" peripheral boundary markers are thought to represent warm season encampments (Bielawski 1985: 19, 26; Nagy 2000a: 29). The identification of at least four structures that are inferred to have sheltered multiple family units (Table 1) provides some limited evidence for the periodic occurrence of communal living. Finally, the identification of a small number of square/rectangular/subrectangular Pre-Dorset structures may indicate some measure of continuity into the Transitional period, although only one of the Pre-Dorset dwellings appears to have been semi-subterranean (Mary-Rousselière 1964).

As a final point, it is interesting to recall Maxwell's (1985: 80) observation that the absence of Pre-Dorset structural remains across large areas of the Central Canadian Low Arctic cannot be adequately explained as a lack of reconnaissance. It is difficult to understand why in some areas, such as the Ekalluk River (Taylor 1967, 1972) and Shoran Lake (Taylor 1967; Müller-Beck 1977), dwelling remains have not been recognized despite evidence that these locations were visited repeatedly by Pre-Dorset groups. It may be possible that the use of alternate methodological strategies (Dekin 1976; Milne, this volume) may aid in the identification of structures that are otherwise invisible.

Transitional period (ca. 2800-2300 B.P.)

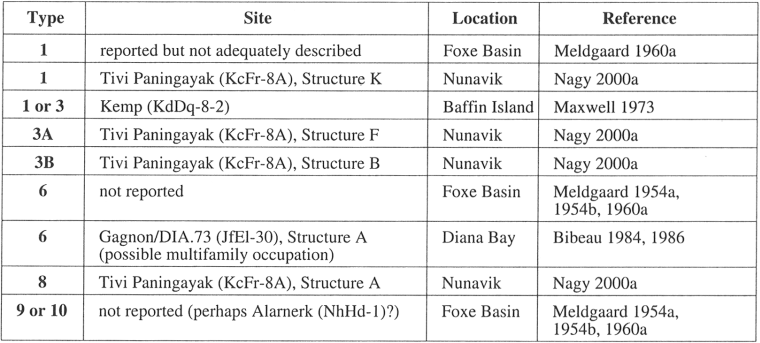

While the Transitional period is not well understood, it is clear that it was a time of cultural change whose outcome undoubtedly led to the development of Dorset culture (Maxwell 1985: 121-122). Two theories have been offered to account for the emergence of Dorset. The first suggests Dorset emerged in multiple locations as an in situ cultural development from Pre-Dorset (Helmer 1994; McGhee 1976, 1996; Maxwell 1985:167; Nagy 1994, 2000; Taylor 1968) while the alternate theory argues for complete replacement of Pre-Dorset by a Dorset culture which developed and expanded outward from the Foxe Basin (Fitzhugh 1997; Tuck and Fitzhugh 1986; Tuck and Ramsden 1990). Accordingly, Transitional populations either made very little contribution to later Dorset groups and are therefore not truly transitioning anything, or they played an integral role in the development of the later Palaeoeskimos. The three Transitional groups identified in the study area have been treated individually elsewhere in the literature and will therefore also be treated separately here, although Table 2 presents the structural data for all of the groups.

Lagoon (ca. 2800-2300 B.P.)

Only two Lagoon Complex sites have been identified, the Lagoon type site (OjRj-3) on southern Banks Island (Arnold 1980, 1981a, 1981b), and the Crane site (ObRv-1) on Cape Bathurst (Le Blanc 1994a, 1994b). Radiocarbon dates indicate this complex is contemporaneous with terminal Barrenground Pre-Dorset (Gordon 1975: Table 12, 1996), easterly Early Dorset (Maxwell 1985: Table 7.1), and Alaskan Choris (Giddings and Anderson 1986) and Norton (Giddings 1964; Dumond 1987). Architectural remains were preserved only at the Lagoon site and are composed of three hearth areas and associated sets of wooden postmoulds (Arnold 1980: 403). The best preserved feature, Area A, has been interpreted as either the hearth and structural supports for a habitation structure, or as a drying or smoking rack (Arnold 1980: 403). The feature is composed of three driftwood posts demarcating a rectangular depression with fire-cracked rocks surrounding a hearth area (Arnold 1980: Figure 4), and can be classified as a Type 6 dwelling.

Table 1

Pre-Dorset structures by type*

Transitional (ca. 2800-2500 B.P.)

Transitional period sites have been identified in the Foxe Basin, Richmond Gulf, and along both coasts of Hudson Strait. Given the culturally intermediate nature of this period and the variety of cultural influences suggested to have been in operation, it is not surprising that the small number of Transitional sites with architectural evidence display a large amount of variation (Table 2). In the Foxe Basin, Meldgaard (1960a: 73,75, 1962: 92-93) suggests a "break" or transition occurred between Pre-Dorset and Dorset at ca. 2800 B.P. based in part on the alteration in house form from round or oval structures with central hearths (Type 4) on the upper Pre-Dorset terraces to larger rectilinear semi-subterranean structures with side-benches at the lower Dorset elevations (Type 6). However, it is unclear based on Meldgaard's descriptions whether the structures located specifically on the Transitional terrace were round, rectangular, or a mixture of the two. What appears certain is that Meldgaard saw a general change in house form when structures associated with a "pure" Pre-Dorset occupation were compared to those linked to "pure" Dorset (although he noted [1954a: 11, 1954b: 6] that there are problems with the identification of the earliest Early Dorset at Igloolik).

Elsewhere, Nagy (2000a: 33) has described rectangular "tent-like structure[s]" from the Pita site (KcFr-5). Structure A is classified as Type 6 because of the large slab anvil stones inside, while Structure B is identified as a Type 5 structure given the lack of recognizable internal features. Both structures are suggested to have been occupied in the cold season (Nagy 2000a: 34).

Groswater (c. 2800-2300 B.P.)

Groswater overlaps with the beginning of the Early Dorset period in Labrador and Nunavik (CARD n.d.). Structural remains have only been reported in the study area from Diana Bay, where site DIA.53 (JgEj-3) contains at least 15 structures, including examples with round/oval/elliptical and square/rectangular/subrectangular peripheral boundaries (Gendron 1999). There was no evidence for clearly recognizable internal features in any of the structures (although D. Gendron [pers comm. 2003] notes they may have been present), implying the seven round/oval/elliptical dwellings are best identified as Type 3A. Eight structures with square/rectangular/subrectangular peripheral boundary markers are identified as Type 5 structures.

Table 2

Transitional period structures by type*

Transitional period summary

Six structural types can be associated with the Transitional period (Table 2). Meldgaard (1960a: 73,75, 1962: 92-93) appears to have viewed this transition in material culture and structural remains as a fairly rapid shift that took place on the 23-22 m asl beach terrace at Igloolik[4]. However, Susan Rowley has more recently commented that oval dwellings with axial features continue into the Early Dorset period at Igloolik (Rowley and Rowley 1997: 274), an occurrence substantiated by work in the Roche Bay area of southern Foxe Basin (Savelle 1983: 76-77; Bielawski 1985: 24-25). This observation strongly implies that the shift from round to rectangular structures may have occurred over a longer period than was originally envisioned. Additionally, it may prove relevant that all of the structural types identified in the Transitional period can also be found in Pre-Dorset and (as will be shown) Early Dorset, suggesting that no new architectural types appear to have been developed, and none abandoned, during the Transitional period.

Early Dorset (ca. 2500-2000 B.P.)

The appropriateness of the designation "Early Dorset" for the cultural remains dating between 2500 B.P. and 2000 B.P. has been questioned by some researchers who argue that this period should be more correctly seen as the final stage of Pre-Dorset, rather than the start of Dorset (see Tuck and Ramsden 1990). While not disregarding the importance of this issue, this paper will follow Helmer (1994: 22), who has pointed out that the "Early" Dorset designation, irregardless of its cultural-historical validity, is internally sound, culturally, and has been used consistently by researchers working throughout the region to identify sites that are at least generally comparable from a material culture standpoint.

Six structural types have been identified in the Early Dorset period (Table 3). At the Tanfield site (KdDq-7-1), Maxwell (1973: 200, 320) reports a 40 cm thick sod deposit which he suggests represents the remains of an intensive occupation, possibly involving as many as 10 or 20 structures that were occupied simultaneously in the fall and/or winter (Maxwell 1973: 208, 318, 320). No structural stones or depressions were identified, indicating to him that the structures were made of snow or sod. If snowhouses were used, a Type 1 affiliation is proposed. However, if sod was used to create the peripheral boundary markers but has become archaeologically invisible (Maxwell [1973: 207, 318] notes there are some indications in the stratigraphic profiles for the use of sod), the structures are best viewed as Type 3A[5].

Elsewhere, a Type 2 structure has been excavated on the 14.5 m asl terrace at the Tasealuk site (PfEv-2). Although not given a cultural designation, the elevation of Feature 214 is consistent with other Early Dorset features at the site (Bielawski 1989: 39-44) and is provisionally designated here as Early Dorset. The structure is described as a "T-shaped" vegetated area enclosing an apparent centrally-located axial feature (represented by a single line of stones) and central hearth. Two potential sleeping places were indicated by areas of levelled gravel to either side of the possible axial feature (Bielawski 1989: 39-42).

A possible multifamily structure at NiHf-23, initially described as a longhouse in Rowley and Rowley (1997: 274), is here identified as a Type 6 structure. My reclassification is based on comments made by Susan Rowley (pers comm., 2003) that the structure is not a longhouse in the sense it is now used (see Damkjar 2000), but more closely follows the term as it was originally employed by Jørgen Meldgaard (1954a: 9, 1960a: 69). Feature 18 from NiHf-47 (Rowley 1995), a Type 4A structure, is notable in that it contains an axial feature (with two hearths), nullifying Maxwell's (1980: 507) earlier observation that such features were absent from the "core area."

Early Dorset summary

Table 3 illustrates the six structural types currently recognized in the Early Dorset period. There is a suggestion that, in at least some areas, dwelling styles reflect increased investment in construction (primarily as this relates to the use of semi-subterranean structures), with at least some of the reported variability tied to seasonal considerations (Maxwell 1985: 197). Whether this was one result of a changing economic system that, as suggested by both Maxwell (1985: 197) and Nagy (2000b), saw some regions used more intensively by larger and increasingly sedentary Early Dorset populations who were adapting a collector-oriented subsistence economy is, for the moment, unclear.

As a relevant digression, the Choris culture, which was initially reported only in Alaska (Dumond 1987), has been identified at the western limit of the study area in the Mackenzie River Delta (Sutherland 1994). Although not part of the same cultural tradition as Dorset, Choris is discussed in this section of the paper given its presence in the study area appears for the moment to be more or less contemporaneous with Early Dorset. The Choris occupation, identified as part of the multi-component Satkualuk site (NiTs-4), has been radiocarbon dated between 2230 B.P. and 1920 B.P. (Sutherland 1994). Although excavation has been limited, Sutherland (1994) has identified a number of features indicative of structural remains. In wind deflated areas of the site are several rock scatters that may represent the remains of tent rings (potential Type 3 or 4 structures), while a number of buried hearths may be in association with possible living floors. However, additional excavation is required to determine the size, shape, and architectural composition of these possible structural remains before they can be further considered.

Middle Dorset (ca. 2000-1500 B.P.)

During the Middle Dorset period, populations underwent marked expansions and retractions in territory. Middle Dorset people appear to have abandoned most of the High Arctic while expanding southward to extensively and (in some areas at least) intensively settle Newfoundland (Maxwell 1985: 198; Renouf 1994, 1999). Whether this can be linked to climatic events is unclear (see Barry et al. 1977), although it does appear that Dorset in more marginal locations may have disappeared as a result of rapid climatic cooling that began near the end of Early Dorset and beginning of Middle Dorset (Fitzhugh 1976; McGhee 1976).

Type 1 structures, which typically leave little trace archaeologically, continued to be employed in this period, although there is some question about the season(s) in which they were used. Meldgaard (1960a: 70) assumes that snowhouses, whose remains are consistent with Type 1 structures, were used by Middle Dorset populations in the Foxe Basin, an inference supported by the identification of snow knives at many sites (Maxwell 1985: 167). However, Structure K at the Tivi Paningayak site (KcFr-8A) in Nunavik, a Type 1 structure that was defined by its artefact scatter, is suggested to have been a warm season occupation (Nagy 2000a: 50-51).

Table 3

Early Dorset structures by type*

In the remainder of the Foxe Basin, it is difficult to discuss Middle Dorset structures given the description of individual sites or structures is insufficient (e.g., it is not specified how many of the 208 Dorset house depressions at Alarnerk [NhHd-1] are Middle Dorset). For this reason, the following is a general overview of the architectural details as currently published. According to Meldgaard (1954a: 9-10; 1960a: 69), Early through Late Dorset houses are rectangular, semi-subterranean (usually excavated about 50 cm below surface), and measure approximately 5 m x 4 m. Open hearths occur in the centre of the structures and sleeping benches are located along the side walls. Entrance passages are absent from all but the latest houses, walls were probably formed of sod on top of low gravel berms, and roof coverings were likely made of skin.

A large 7 m x 4.5 m oblong semi-subterranean feature at the Gagnon site (DIA.73, JfEl-30), initially thought to be a longhouse (Bibeau 1986: 29), can be classified as a Type 6 structure. The structure, defined by a low broad sand and gravel berm, was excavated approximately 10 cm into the ground and had a partially paved interior (Plumet 1976: Figure 26; Bibeau 1984: Plans 2 and 3, 1986: Figures 6-7, 30). Bibeau (1984: 139-140, 1986: 30-31) believes the structure was occupied only once in the late summer and/or early fall by two families who may have been awaiting the formation of stable sea ice.

Further east, near Ivujivik, the first reported example of a Type 8 structure occurs at the site of Tivi Paningayak (KcFr-8A). Structure A, described as a sod-walled semi-subterranean rectangular structure with a possible lamp stand (Nagy 2000a: 50), also had a 1 m long sod entrance passage constructed on the ground surface (Nagy 2000a: Figure 3.36). The other structural type to premiere during the Middle Dorset period is the communal longhouse, identified by Meldgaard (1954a: 9, 1960a: 69) on the Middle Dorset terraces at Igloolik. He reports that the structures are semi-subterranean (presumably with an associated gravel berm) and measure 14 m by 7 m, although it is unclear based on his descriptions whether any contained indications of internal features (Meldgaard 1954a: 9). Based on current information, the structures can only be generally identified as either Type 9 or Type 10.

Table 4

Middle Dorset structures by type*

Middle Dorset summary

Five structural types have been identified in the Middle Dorset period, ranging from ephemeral Type 1 structures to the more substantial architectural remains associated with multiple families and perhaps communal gatherings (Table 4). It is also during this period that above ground entrance passages are first identified. It may be significant that all of the Middle Dorset dwellings thus far reported occur in the Foxe Basin Hudson Strait "core area," considering the major demographic retractions and expansions that occurred at the start of the Middle Dorset period (Fitzhugh 1997: 404, 406-409).

Late Dorset (ca. 1500-1000 B.P.)

The Late Dorset period appears to coincide with a warming episode in most regions (Barry et al. 1977; McGhee 1996: 200) and is marked by large-scale demographic changes including the return of Dorset people to the High Arctic (Helmer 1996: 305; Schledermann 1996: 101-103) and their abandonment of Newfoundland (Renouf 1999; Tuck and Pastore 1985). Late Dorset populations appears to have become more sedentary than earlier ones, as well as intensive resource extractors in some regions (Murray 1999). Large sea mammals, particularly walrus, but perhaps also large and small whales, were regularly exploited (Mary-Rousselière 1976; Mathiassen 1958; McGhee 1981; Murray 1999; Whitridge 1999), and Late Dorset groups appear to have used the sea ice much more extensively (Cox and Spiess 1980; Maxwell 1985: 223, 235; Spiess 1978). Twelve structural types are suggested to have been constructed and used by the Late Dorset (Table 5).

Graham Rowley was the first to excavate a recognized Late Dorset house in Foxe Basin when he visited the Abverdjar site (NiHg-1). He reported "three or four scarcely visible hollows," that when excavated yielded probable paving stones (Rowley 1940: 491; Maxwell 1985: 221). The structures were interpreted as the remains of circular sod dwellings (Rowley 1940: 491) and are thus classified here as Type 4A structures. At the Tikilik site (NiHf-2), a Type 6 Late Dorset structure (partially overlain by a Thule sod house) has been identified on the basis of its rectilinear outline and large slab-lined axial feature with pot stand and blubber-encrusted pit. To one side of the axial feature was a sleeping area with preserved moss bedding (Murray 1996: Figure 4.11; Rowley 1997; Rowley and Rowley 1997: Figure 4).

Further east, Structure B from the Cordeau/DIA.1 site (JfEl-1) is described as a semi-subterranean rectangular structure (Plumet 1976: 197, Figure 24). An axial feature with a centrally positioned hearth was located in the middle of the structure, and paving stones were placed immediately outside the upright slabs of the axial feature. It is therefore also a Type 6 structure.

A large Thule component has been identified at the Talagwak site (KeDq-2) on southern Baffin Island; however, Late Dorset may also be represented by a shallow rectangular semi-subterranean structure with a 1.5 m cold-trap entrance passage (Maxwell 1973: 253, Figure 61, 1985: 235). The peripheral boundary walls were defined by a combination of naturally outcropping bedrock and a small earthen berm, and unlike the nearby Thule structures, did not incorporate whalebone and sod as building materials. Diagnostic artefacts were only recovered from outside the dwelling and suggest a Late Dorset occupation that was late in the period (Maxwell 1973: 253-254). This feature is identified as a Type 7 structure.

Although first reported during Middle Dorset (Meldgaard 1954a: 9, 1960b: 589), the sudden and geographically widespread construction of longhouses in the Late Dorset period represents an unprecedented development in the Palaeoeskimo architectural tradition. Now known from virtually all regions of the study area (except the Foxe Basin, see Damkjar 2000), there appears to be a geographic relationship between specific types and geographic location. As shown in Table 5 (see also Damkjar 2000), semi-subterranean longhouses defined by low gravel berms (Types 9 and 10) are only found in the Nunavik portion of the Central Canadian Low Arctic, while surface structures defined by stone walls of varying sizes (Types 11 and 12) have been reported almost everywhere else. There is little understanding of how and why longhouses were first conceived and built (although Lee [1974] and McGhee [1996: 210] have both entertained the idea of external influences), nor is it understood why Late Dorset longhouses were not constructed in the Foxe Basin. In terms of the distribution of longhouse structures, it should be pointed out that the longhouse reported by Maxwell (1985: 157, Figure 7.29) on Juet Island could not be relocated despite repeated helicopter surveys of Juet and nearby islands, although two undisturbed longhouses have been located elsewhere in the North Bay area (Sutherland pers comm., 2003).

Late Dorset summary

Twelve structural types have been associated with Late Dorset (Table 5), demonstrating it was the most architecturally variable of all the Palaeoeskimo periods represented in the study region. Other than this obvious versatility, the most visible architectural development is the increased construction and use of large communal longhouse structures. Although multifamily structures had been used at least intermittently since Pre-Dorset times, the huge longhouses of this period indicate that a new emphasis may have been placed on communal aggregations. Finally, the construction of entrance passages, a characteristic attribute of structural Types 7 and 8, appears to have become slightly more common during Late Dorset times.

Table 5

Late Dorset structures by type*

Table 6

Terminal Dorset structures by type*

Terminal Dorset (ca. 1000-500 B.P.)

Although Late Dorset appears to mark the end of the Palaeoeskimo occupation of the Central Canadian Low Arctic in most areas, a small number of sites in the Foxe Basin — Hudson Strait — Hudson Bay area appear to have been occupied until at least 500 B.P. and may overlap temporally and geographically with Thule Inuit populations[6]. The existence and nature of this contact has been highly debated by those who discount the idea that the two groups could have ever met (e.g., Park 1993, 2000) and those who believe contact was possible but was avoided or limited (e.g., Bielawski 1979; Fitzhugh 1994; Friesen 2000; Gulløv 1996; McGhee 1984, 1997; Plumet 1979, 1994). Acknowledging that debate exists concerning this time, the Terminal Dorset period is included in this paper for the chief reason that much of the evidence for Terminal Dorset relates to architectural remains. As such, neglecting sites that have not conclusively been shown to be anything other than Dorset would be a serious omission. Three dwelling types are represented in the Terminal Dorset period.

As shown in Table 6, two Type 4 structures were excavated in the Richmond Gulf area by Elmer Harp, Jr. (1976). House 1 at the Gulf Hazard-1 site (HaGd-4) dates to 800 B.P. and is interpreted as a summer dwelling that prior to excavation appeared as a vague circle of lichen-covered rocks (Harp 1976: 130, 132-134, Figure 2c, Figures 6-7). Upon excavation, the interior proved to be slightly depressed and paved on one half with flagstones, with a storage pit and possible informal hearth area located amidst the pavement, while the other half of the dwelling was probably the sleeping area. Intriguing indications of external contacts are suggested by the recovery of a copper amulet of European origin in the structure (Harp 1974), as well as close architectural similarities between House 1 and a nearby Thule structure (although Harp [1976: 130] does not detail this similarity).

Two Type 6 structures have been located in Frobisher Bay (Odess 1996, 1998). House 1 from Newell Sound-4 (KgDl-4) was a semi-oval depression, one side of which had squared corners, and closely resembles a structure reported by Cox (1978: 111) from northern Labrador (Odess 1996: 174). The floor was excavated between 15-40 cm below ground surface, the interior walls were created with fill from the floor excavation, and the inner wall boundary was reinforced. A portion of the floor was paved, and in the middle of this pavement was an axial feature composed of upright slabs. Two hearths with notched pot supports were located at either end of the axial feature and a sand covered feature to the side of the flagstones may have been a sleeping area. A late fall to early winter occupation is inferred (Odess 1996: 175).

A Type 13 structure has been reported from the Tuvaaluk site (JfEl-4) in Nunavik (Plumet 1976, 1994). Identified as Structure A and dating after 500 B.P., the structure is contemporaneous with Harp's (1976) Richmond Gulf sites and at least one nearby Thule site (Plumet 1974: 53, 1994: 135-136). Surface examination of architectural elements including walls constructed of bowhead whale bones and large boulders, as well as a cold-trap entrance tunnel blocked with a whale skull, resulted in the identification of Structure A as Thule (Plumet 1974: Photos 17-18, 1979: 113, Figure 4). However, this affiliation was later questioned when erosion along the house's western wall exposed a soapstone vessel painted with red ochre, as well as a number of Dorset lithic artefacts.

Excavation confirmed the use of typical Thule construction methods including cantilevered whale rib and large stone walls, a kitchen alcove, and a paved area surrounding an opening to the sunken entrance passage, but also revealed several Dorset traits (Plumet 1976: 199, 1979: 113). These included a paved axial feature with notched pot supports, laterally positioned sleeping areas, and internal storage pits (Plumet 1976: Photo 18). Although the 3 m long entrance tunnel appears to have been repositioned at some point during the occupation of the structure, the dwelling itself was created in one episode and was not remodelled. Plumet (1979: 114) believes the architectural hybridization seen in this Dorset structure was the result of Thule influence.

Terminal Dorset summary

Three dwelling types have been identified in the Terminal Dorset period (Table 6). The continued use of Type 4 and Type 6 structures appears unremarkable in that it represents the continuation of building traditions in use since the Pre-Dorset period. This may be taken to indicate that, although aware of and perhaps even in contact with their Thule neighbours, some Terminal Dorset groups preferred, in Odess's (1996: 201) words, to associate "with their own kind." However, the identification of Type 13 Terminal Dorset structures in Hudson Bay and Hudson Strait suggests that at some point these influences were sufficiently strong for the Dorset to fundamentally alter their building traditions.

Discussion

In terms of the architectural remains thus far located, a relatively high degree of structural variability appears to be a common theme throughout the 4,000-year Palaeoeskimo occupation of the Central Canadian Low Arctic. This analysis indicates that some structural types are (at least for the moment) chronologically restricted while other types appear to have been used virtually continuously, although the reasons for this are not well understood. Certainly the Pre-Dorset, Transitional Period, and Early Dorset all share the use of Type 1-6 structures, which may arguably be taken to indicate a degree of cultural continuity. Unlike their predecessors, Middle Dorset seem to have abandoned Type 4 and 5 structures while developing Types 8 and 9 (or 10), although it is unclear whether this situation reflects actual events or is an artefact of limited research into Middle Dorset in the region. The Late Dorset period may represent a fluorescence in terms of the number of different types of structures used (12 types are currently represented), while the architectural remains of the Terminal Dorset may substantiate claims for cultural contact between Dorset and Thule

To reiterate the primary aim of this paper, the dwelling types proposed are meant to function as an objective method by which to order the large amount of Palaeoeskimo architectural data and are used in this paper as a descriptive tool rather than as part of an interpretative analysis. The reconciliation of different dwelling remains with issues of mobility, seasonality, and intra-cultural temporal change have not been addressed, although it is suggested that the structural divisions presented here may assist that process. Certainly, a better understanding of these issues in tandem with a greater recognition of the need to treat dwelling remains as an informative data set in their own right, will increase our appreciation of the Palaeoeskimo period as a whole.

Appendices

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my gratitude to all of those who generously gave of their opinions and data during the various developmental stages of this paper: Eric Damkjar, Max Friesen, Daniel Gendron, Brooke Milne, Peter Ramsden, Susan Rowley, and Patricia Sutherland. This paper was greatly improved by the insightful comments and suggestions of Susan Rowley, Pat Sutherland, Matthew Betts, and one anonymous reviewer. My gratitude goes out to Sylvie LeBlanc and Murielle Nagy, who organized the excellent and enjoyable Palaeoeskimo Architecture: State of Knowledge Symposium in September 2002, which more than anything, crystallized for me just how diverse and variable Palaeoeskimo architecture truly is. Thank you both for trusting me to write this overview.

Notes

-

[1]

A single Choris site is discussed briefly in this paper in the Early Dorset summary.

-

[2]

Very shallow hollows, often only recognized after excavation and with the assistance of stratigraphic profiles, are not considered to represent true peripheral boundary markers. For this reason, minimally depressed structures that lack more substantial boundary indicators (e.g., hold-down stones or a berm) are classified as Type 1 or 2 structures.

-

[3]

This is a problematic term in that it has rarely been explicitly defined by those who use it to differentiate (presumably) more robust architectural remains from those that are less heavily built. It is used in this paper as an attribute denoting a subtype and with the knowledge that further research may suggest this subtype be expanded to become a separate type, or simply abandoned altogether.

-

[4]

Meldgaard (1960a, 1962) consistently reports the Pre-Dorset/Dorset transition took place along the 23 m asl and 22 m asl terraces while Maxwell (1985: 110) identifies the transition between 24 m asl and 20 m asl and also between 24-22 m asl (Maxwell 1985: 184).

-

[5]

This is also a relevant point when considering the structural remains from the Kemp site (KdDq-8-2), a Middle Dorset locality interpreted to have supported either snow or sod houses (Maxwell 1973: 124-125).

-

[6]

Meldgaard (1954b: 7, 1960a: 69) suggested that the latest Dorset in Foxe Basin adopted the use of semi-subterranean cold-trap entrance passages from immigrating Thule groups, although Rowley and Rowley (1997: 275) note that entrance passages associated with Dorset occupations have not yet been identified in the region.

References

- ADAMS, William Y. and Ernest W. ADAMS, 1991 Archaeological Typology and Practical Reality: A Dialectical Approach to Artifact Classification and Sorting, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

- ARNOLD, Charles D., 1980 A Paleoeskimo occupation on southern Banks Island, N.W.T. Arctic, 33(3): 400-426.

- ARNOLD, Charles D., 1981a The Lagoon Site (ObRl-3): Implications for Paleoeskimo Interactions, Ottawa, National Museum of Man, Archaeological Survey of Canada, Mercury Series, 107.

- ARNOLD, Charles D., 1981b Demographic process and culture change: an example from the western Canadian Arctic, in P.D. Francis, F.J. Kense, and P.G. Duke (eds), Networks of the Past: Regional Interaction in Archaeology, Calgary, The Archaeological Association of the University of Calgary: 311-326.

- BADGLEY, Ian, 1980 Stratigraphy and habitation features at DIA.4 (JfEl-4), a Dorset site in Arctic Quebec, Arctic, 33(3): 569-584.

- BANNING, Edward B., 2000 The Archaeologist's Laboratory: The Analysis of Archaeological Data, New-York, Kluwer Academic Press.

- BARRY, Roger G., Wendy H. ARUNDALE, John T. ANDREWS, Raymond S. BRADLEY and Harvey NICHOLS, 1977 Environmental change and cultural change in the eastern Canadian Arctic during the last 5000 years, Arctic and Alpine Research, 9(2): 193-210.

- BIBEAU, Pierre, 1984 Établissements paléoesquimaux du site Diana 73, Ungava, Montréal, Laboratoire d'archéologie de l'Université du Québec à Montréal, Paléo-Québec, 16.

- BIBEAU, Pierre, 1986 Présences paléoesquimaudes au site Gagnon, Palaeo-Eskimo Cultures in Newfoundland, Labrador and Ungava, St. John's, Memorial University of Newfoundland, Reports in Archaeology, 1: 27-38.

- BIELAWSKI, Ellen, 1979 Contactual transformation: the Dorset-Thule succession, in A.P. McCartney (ed.), Thule Eskimo Culture: An Anthropological Retrospective, Ottawa, National Museum of Man, Archaeological Survey of Canada, Mercury Series, 88: 100-109.

- BIELAWSKI, Ellen, 1982 Spatial behaviour of prehistoric Arctic hunters: analysis of the site distribution on Aston Bay, Somerset Island, N.W.T., Canadian Journal of Archaeology, 6: 33-45.

- BIELAWSKI, Ellen, 1985 Paleoeskimo archaeology at Roche Bay, N.W.T.: 1984 field work and preliminary analysis, unpublished report on file, Yellowknife, Prince of Wales Northern Heritage Centre.

- BIELAWSKI, Ellen, 1989 Tasealuk: Corridor Through Time. Final report of the Northern Cultural Heritage Project, Stanwell-Fletcher Lake, Somerset Island, Northwest Territories, Canada, 1979-1983, unpublished report on file, Yellowknife, Prince of Wales Northern Heritage Centre.

- CARD (Canadian Archaeological Radiocarbon Database), n.d. www.canadianarchaeology.com/radiocarbon/card/card.htm Compiled by R. Morlan.

- COLLINS, Henry B., 1956a Archaeological investigations on Southampton and Coats Islands, N.W.T. Annual Report of the National Museum of Canada for 1954-55, National Museum of Canada Bulletin, 142: 82-113.

- COLLINS, Henry B., 1956b The T-1 site at Native Point, Southampton Island, N.W.T., Anthropological Papers of the University of Alaska, 4: 63-89.

- COLLINS, Henry B., 1957 Archaeological investigations on Southampton and Walrus Islands, N.W.T. Annual Report of the National Museum of Canada for 1956, National Museum of Canada Bulletin, 147: 22-61.

- COX, Steven L., 1978 Paleo-Eskimo occupation of the Labrador coast, Arctic Anthropology, 15(2): 96-118.

- COX, Steven L. and Arthur SPIESS, 1978 Dorset settlement and subsistence in northern Labrador, Arctic, 33: 659-669.

- DAMKJAR, Eric, 2000 A survey of Late Dorset longhouses, in M. Appelt, J. Berglund and H.C. Gulløv (eds), Identities and Cultural Contacts in the Arctic, Copenhagen, National Museum of Denmark and Danish Polar Center, Danish Polar Center Publication, 8: 170-180.

- DEKIN, Albert A., Jr., 1976 Elliptical analysis: an heuristic technique for the analysis of artifact clusters, in M.S. Maxwell (ed.), Eastern Arctic Prehistory: Palaeoeskimo Problems, Washington, Memoirs of the Society for American Archaeology, 31: 79-88.

- DESROSIERS, Pierre, 1986 Pre-Dorset surface structures from Diana-1, Ungava Bay (Nouveau Québec), in Palaeo-Eskimo Cultures in Newfoundland, Labrador and Ungava, St. John's, Memorial University of Newfoundland, Reports in Archaeology, 1: 3-25.

- DUMOND, Don E., 1987 The Eskimos and Aleuts, London, Thames and Hudson.

- FITZHUGH, William W., 1976 Environmental factors in the evolution of Dorset culture: a marginal approach for Hudson Bay, in M.S. Maxwell (ed.), Eastern Arctic Prehistory: Palaeoeskimo Problems, Washington, Memoirs of the Society for American Archaeology, 31: 139-149.

- FITZHUGH, William W., 1994 Staffe Island and the Northern Labrador Dorset-Thule succession, Threads of Arctic Prehistory: Papers in Honour of William E. Taylor, Jr., in D. Morrison and J.-L. Pilon (eds), Ottawa, Canadian Museum of Civilization, Archaeological Survey of Canada, Mercury Series, 149: 239-268.

- FITZHUGH, William W., 1997 Biogeographical archaeology in the Eastern North American Arctic, Human Ecology, 25(3): 385-418.

- FRIESEN, T. Max, 2000 The role of social factors in Dorset-Thule interaction, in M. Appelt, J. Berglund and H.C. Gulløv (eds), Identities and Cultural Contacts in the Arctic, Copenhagen, National Museum of Denmark and Danish Polar Center, Danish Polar Center Publication, 8: 192-205.

- FRITZ, John M. and Fred T. PLOG, 1970 The nature of archaeological explanation, American Antiquity, 33(2): 149-155.

- GAUVIN, H., 1990 Analyses Spatiales d'un site Dorsétien: le sous-espace D de DIA.4, Mémoire de maîtrise, Montréal, Université de Montréal, Département d'anthropologie.

- GENDRON, Daniel, 1999 The Early Palaeo-Eskimo Boulder Field Sites: Methodological and Interpretative Issues, Paper presented at the 32nd Annual Meeting of the Canadian Archaeological Association, Whitehorse.

- GENDRON, Daniel and Claude PINARD, 2000 Early Palaeo-Eskimo occupations in Nunavik: A re-appraisal, in M. Appelt, J. Berglund and H.C. Gulløv (eds), Identities and Cultural Contacts in the Arctic, Copenhagen, National Museum of Denmark and Danish Polar Center, Danish Polar Center Publicaion, 8: 129-142.

- GIDDINGS, J. Louis, 1964 The Archaeology of Cape Denbigh, Providence, Brown University Press.

- GIDDINGS, J. Louis and Douglas D. ANDERSON, 1986 Beach Ridge Archeology of Cape Krusenstern: Eskimo and Pre-Eskimo Settlements Around Kotzebue Sound, Alaska, Washington, U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Publications in Archeology, 20.

- GORDON, Bryan C., 1975 Of Men and Herds in Barrenground Prehistory, Ottawa, National Museum of Man, Archaeological Survey of Canada, Mercury Series, 28.

- GOSSELIN, André and Jean-Paul SALAÜN, 1974 Description des sites et des structures, in A. Gosselin, P. Plumet, P. Richard and J.-P. Salaün (eds), Recherches archéologiques et paléoécologiques au Nouveau-Québec, Montréal, Laboratoire d'archéologie de l'Université du Québec à Montréal, Paléo-Québec, 1: 11-32.

- GULLØV, Hans Christian, 1996 In search of the Dorset culture in the Thule culture, in B. Gronnøw (ed.), The Paleo-Eskimo Cultures of Greenland. New Perspectives in Greenlandic Archaeology, Copenhagen, Danish Polar Center, Danish Polar Centre Publication, 1: 201-214.

- HARP, Elmer, Jr., 1961 The Archaeology of the Lower and Middle Thelon, Northwest Territories, Montréal, Arctic Institute of North America, Technical Paper, 8.

- HARP, Elmer, Jr., 1974 A Late Dorset copper amulet from southeastern Hudson Bay, Folk, 16-17: 33-44.

- HARP, Elmer, Jr., 1976 Dorset settlement patterns in Newfoundland and southeastern Hudson Bay, in M.S. Maxwell (ed.), Eastern Arctic Prehistory: Palaeoeskimo Problems, Salt Lake City, Memoirs of the Society for American Archaeology, 31: 119-138.

- HARP, Elmer, Jr., 1997 Pioneer Settlements of the Belcher Islands, N.W.T., in R. Gilberg and H. C. Gulløv (eds), Fifty Years of Arctic Research: Anthropological Studies from Greenland to Siberia, Copenhagen, National Museum of Denmark, Ethnographical Series, 18: 157-168.

- HELMER, James W., n.d. http://www.arky.ucalgary.ca/arky1/helmer/EKKALUK.html

- HELMER, James W., 1994 Resurrecting the spirit(s) of Taylor's "Carlsberg Culture": cultural traditions and cultural horizons in Eastern Arctic prehistory, in D. Morrison and J.-L. Pilon (eds), Threads of Arctic Prehistory: Papers in Honour of William E. Taylor, Jr., Ottawa, Canadian Museum of Civilization, Archaeological Survey of Canada, Mercury Series Paper, 149: 15-34.

- HELMER, James W., 1996 A tale of three villages: assessing the archaeological potential of three Late Dorset settlements on Little Cornwallis Island, N.W.T., in B. Gronnøw and John Pind (eds), The Paleo-Eskimo Cultures of Greenland. New Perspectives in Greenlandic Archaeology, Copenhagen, Danish Polar Center, Danish Polar Centre Publication, 1: 295-308.

- IRVING, William N., 1957 An archaeological survey of the Susitna Valley, Anthropological Papers of the University of Alaska, 6(1): 37-52.

- JENNESS, Diamond, 1925 A new Eskimo culture in Hudson Bay, The Geographical Review, 15(3): 428-437.

- LAUGHLIN, William S. and William E. TAYLOR, Jr., 1960 A Cape Dorset culture site on the west coast of Ungava Bay, National Museum of Canada Bulletin, 167: 1-28.

- Le BLANC, Raymond J., 1994a The Crane Site and the Palaeoeskimo Period in the Western Canadian Arctic, Ottawa, Canadian Museum of Civilization, Archaeological Survey of Canada, Mercury Series, 148.

- Le BLANC, Raymond J., 1994b The Crane site and the Lagoon complex in the Western Canadian Arctic, in D. Morrison and J.L-. Pilon (eds), Threads of Arctic Prehistory: Papers in Honour of William E. Taylor, Jr., Ottawa, Canadian Museum of Civilization, Archaeological Survey of Canada, Mercury Series, 149: 87-102.

- LEE, Thomas E., 1968 Archaeological Discoveries, Payne Bay Region, Ungava, 1966, Québec, Université Laval, Centre d'études nordiques, Travaux divers, 17.

- LEE, Thomas E., 1971 Archaeological Investigation of a Longhouse, Pamiok Island, Ungava, 1970, Québec, Université Laval, Centre d'études nordiques, Nordicana, 33.

- LEE, Thomas E., 1974 Archaeological Investigations of a Longhouse Ruin, Pamiok Island, Ungava Bay, 1972, Québec, Université Laval, Centre d'études nordiques, Paléo-Québec, 2.

- LEECHMAN, Douglas, 1943 Two new Cape Dorset sites, American Antiquity, 8(4): 363-375.

- McGHEE, Robert, 1970 An archaeological survey of western Victoria Island, N.W.T., Canada, National Museum of Man Bulletin, 232: 157-191.

- McGHEE, Robert, 1976 Paleoeskimo occupations of Central and High Arctic Canada, in M.S. Maxwell (ed.), Eastern Arctic Prehistory: Paleoeskimo Problems, Washington, Memoirs of the Society for American Archaeology, 31: 15-39.

- McGHEE, Robert, 1981 The Dorset Occupations in the Vicinity of Port Refuge, High Arctic Canada, Ottawa, National Museum of Man Archaeological Survey of Canada, Mercury Series, 105.

- McGHEE, Robert, 1984 Contact between Native North Americans and the Mediaeval Norse: A review of the evidence, American Antiquity, 49(1): 4-26.

- McGHEE, Robert, 1996 Ancient People of the Arctic, Vancouver, UBC Press.

- McGHEE, Robert, 1997 Meetings between Dorset culture Palaeo-Eskimos and Thule culture Inuit: evidence from Brooman Point, in R. Gilberg and H.C. Gulløv (eds), Fifty Years of Arctic Research: Anthropological Studies from Greenland to Siberia, Copenhagen, National Museum of Denmark, Ethnographical Series, 18: 209-213.

- MARY–ROUSSELIÈRE, Guy, 1955 Report on Archaeological Excavations at Baker Lake and Chesterfield Inlet, Summer 1955, unpublished report on file, Gatineau, Canadian Museum of Civilization.

- MARY–ROUSSELIÈRE, Guy, 1964 Palaeo-Eskimo remains in the Pelly Bay region, N.W.T., Ottawa, National Museum of Canada Bulletin, 193 (1): 162-183.

- MARY–ROUSSELIÈRE, Guy, 1976 The Paleoeskimo in northern Baffinland, in M.S. Maxwell (ed.), Eastern Arctic Prehistory: Palaeoeskimo Problems, Washington, Memoirs of the Society for American Archaeology, 31: 40-57.

- MATHIASSEN, Therkel, 1958 The Sermermiut Excavations, 1955, Meddelelser om Grønland, 161(3).

- MAXWELL, Moreau S., 1973 Archaeology of the Lake Harbour District, Baffin Island, Ottawa, National Museum of Man, Archaeological Survey of Canada, Mercury Series, 6.

- MAXWELL, Moreau S., 1976 Pre-Dorset and Dorset artefacts: The view from Lake Harbour, in M.S. Maxwell (ed.), Eastern Arctic Prehistory: Palaeoeskimo Problems, Washington, Memoirs of the Society for American Archaeology, 31: 58-78.

- MAXWELL, Moreau S., 1980 Dorset site variation on the southeastern coast of Baffin Island, Arctic, 33(3): 505-516.

- MAXWELL, Moreau S., 1984 Pre-Dorset and Dorset prehistory of Canada, in D. Damas (ed.), Handbook of North American Indians, Vol. 5, Arctic, Washington, Smithsonian Institute Press: 359-368.

- MAXWELL, Moreau S., 1985 Prehistory of the Eastern Arctic, New York, Academic Press.

- MELDGAARD, Jørgen, 1954a Report on the Archaeological Work Preformed in the Igloolik Area, N.W.T. May 19-Sept. 21 1954, Vol. 1, unpublished report on file, Gatineau, Canadian Museum of Civilization.

- MELDGAARD, Jørgen, 1954b Summary: The Dorset Culture – The Danish-American Expedition to Arctic Canada 1954, Vol. 2, unpublished report on file, Gatineau, Canadian Museum of Civilization.

- MELDGAARD, Jørgen, 1960a Origin and evolution of Eskimo cultures in the Eastern Arctic, Canadian Geographical Journal, 60(2): 64-75.

- MELDGAARD, Jørgen, 1960b Prehistoric culture sequences in the Eastern Arctic as elucidated by stratified sites at Igloolik, in A.F.C. Wallace (ed.), Men and Cultures: Selected Papers of the Fifth International Congress of Anthropological and Ethnological Sciences, Philadelphia, University of Philadelphia Press: 588-595.

- MELDGAARD, Jørgen, 1962 On the formative period of the Dorset culture, in J.M. Campbell (ed.), Prehistoric Cultural Relations Between the Arctic and Temperate Zones of North America, Montréal, Arctic Institute of North America, Technical Paper 11: 92-95.

- MEYER, David A., 1977 Pre-Dorset Settlements at the Seahorse Gully Site, Ottawa, National Museums of Canada, Archaeological Survey of Canada, Mercury Series, 57.

- MÜLLER-BECK, Hans J. (editor), 1977 Excavations on Banks Island, N.W.T., 1970 and 1973 Preliminary Report, Tübingen, Urgeschichtliche Materialhefte, 1.

- MURRAY, Maribeth S., 1996 Economic Change in the Palaeoeskimo prehistory of the Foxe Basin, N.W.T., Ph.D. dissertation, Hamilton, McMaster University, Department of Anthropology.

- MURRAY, Maribeth S., 1999 Local Heroes. The long-term effects of short-term prosperity – an example from the Canadian Arctic, World Archaeology, 30(3): 466-483.

- MURRAY, Maribeth S. and Peter RAMSDEN, n.d. Short-term sedentism as a pioneering exploratory strategy in Arctic Canada, in Ancient Travellers – Proceedings of the 27th Annual Chacmool Conference, Calgary, University of Calgary.

- NAGY, Murielle I., 1994 A critical review of the Pre-Dorset/Dorset transition, in D. Morrison and J.-L. Pilon (eds), Threads of Arctic Prehistory: Papers in Honour of William E. Taylor, Jr., Ottawa, Canadian Museum of Civilization, Archaeological Survey of Canada, Mercury Series, 149: 1-14.

- NAGY, Murielle I., 2000a Palaeoeskimo cultural transition: A case study from Ivujivik, Eastern Arctic, Montréal, Avataq Cultural Institute, Nunavik Archaeology Monograph Series, 1.

- NAGY, Murielle I., 2000b From Pre-Dorset foragers to Dorset collectors: Palaeo-Eskimo cultural change in Ivujivik, Eastern Canadian Arctic, in M. Appelt, J. Berglund and H.C. Gulløv (eds), Identities and Cultural Contacts in the Arctic, Copenhagen, National Museum of Denmark and Danish Polar Center, Danish Polar Center Publication, 8: 143-148.

- NASH, Ronald J., 1969 The Arctic Small Tool Tradition in Manitoba, Winnipeg, University of Manitoba, Department of Anthropology, Occasional Paper, 2.

- NASH, Ronald J., 1972 Dorset culture in northeastern Manitoba, Canada, Arctic Anthropology, 9(1): 10-16.

- NASH, Ronald J., 1976 Cultural systems and culture change in the Central Arctic, in M.S. Maxwell (ed.), Eastern Arctic Prehistory: Palaeoeskimo Problems, Washington, Memoirs of the Society for American Archaeology, 31: 150-155.

- O'BRYAN, Deric, 1953 Excavation of a Cape Dorset house site, Mill Island, West Hudson Strait, Ottawa, Annual Report of the National Museum of Canada for 1951-52, Bulletin 128: 40-57.

- ODESS, Daniel, 1996 Interaction, Adaptation, and Culture Change: Lithic Exchange in Frobisher Bay Dorset Society, Baffin Island, Arctic Canada, Ph.D. dissertation, Providence, Brown University.

- ODESS, Daniel, 1998 The archaeology of interaction: Views from artifact style and material exchange in Dorset society, American Antiquity, 63(3): 417-435.

- PARK, Robert W., 1993 The Dorset-Thule succession in Arctic North America: Assessing claims for cultural contact, American Antiquity, 58(2): 203-234.

- PARK, Robert W., 2000 The Dorset-Thule succession revisited, in M. Appelt, J. Berglund and H.C. Gulløv (eds), Identities and Cultural Contacts in the Arctic, Copenhagen, National Museum of Denmark and Danish Polar Center, Danish Polar Center Publication, 8: 192-205.

- PLUMET, Patrick, 1969 Archéologie de l'Ungava: le probléme des maisons longues à deux hémicycles et séparations intérieures, Paris, École Pratique des Hautes Études, Centre d'études arctiques et finno-scandinaves, 7.

- PLUMET, Patrick, 1974 Présentation de la mission archéologique Ungava 73, in A. Gosselin, P. Plumet, P. Richard and J.-P. Salaün (eds), Recherches archéologiques et paléoécologiques au Nouveau-Québec, Montréal, Laboratoire d'archéologie de l'Université du Québec à Montréal, Paléo-Québec, 1: 51-58.

- PLUMET, Patrick, 1976 Archéologie du Noveau-Québec: habitats paléo-esquimaux à Poste-de-la-Baleine, Québec, Université Laval, Centre d'études nordiques, Paléo-Québec, 7.

- PLUMET, Patrick, 1979 Thuléens et Dorsétiens dans l'Ungava (Nouveau-Québec), in A.P. McCartney (ed.), Thule Eskimo Culture: An Anthropological Retrospective, Ottawa, National Museums of Canada, Archaeological Survey of Canada, Mercury Series Paper, 88: 110-121.

- PLUMET, Patrick, 1985 Archéologie de l'Ungava: le site de la Pointe aux Bélougas (Qilalugarsiuvik et les maisons longues dorsétiennes), Montréal, Laboratoire d'archéologie de l'Université du Québec à Montréal, Paléo-Québec, 18.

- PLUMET, Patrick, 1986 Questions et réflexions concernant la préhistoire de l'Ungava, in Palaeo-Eskimo Cultures in Newfoundland, Labrador, and Ungava, St.John's, Memorial University of Newfoundland, Reports in Archaeology 1:151-160.

- PLUMET, Patrick, 1994 Le Paléoesquimau de la baie Diana (Arctique québécois), in D. Morrison and J.-L. Pilon (eds), Threads of Arctic Prehistory: Papers in Honour of William E. Taylor, Jr., Hull, Canadian Museum of Civilization, Archaeological Survey of Canada, Mercury Series 149: 103-144.

- PLUMET, Patrick and Ian BADGLEY, 1980 Implications méthodologiques des fouilles de Tuvaaluk sur l'étude des établissements dorsétiens, Arctic, 33(3): 542-552.

- RAMSDEN, Peter and Maribeth S. MURRAY, 1995 Identifying seasonality in Pre-Dorset structures at Back Bay, Prince of Wales Island, NWT, Arctic Anthropology, 32(2): 106-117.

- RENOUF, M.A. Priscilla, 1994 Two transitional sites at Port au Choix, northwestern Newfoundland, in D. Morrison and J.L-. Pilon (eds), Threads of Arctic Prehistory: Papers in Honour of William E. Taylor, Jr., Hull, Canadian Museum of Civilization, Archaeological Survey of Canada, Mercury Series, 149: 165-196.

- RENOUF, M.A. Priscilla, 1999 Prehistory of Newfoundland hunter-gatherers: extinctions or adaptations? World Archaeology, 30(3): 403-420.

- ROWLEY, Graham, 1940 The Dorset culture in the Eastern Arctic, American Anthropologist, 42(3): 490-499.

- ROWLEY, Susan, 1991 Igloolik Archaeology Field School: Report for 1991, unpublished report on file, Yellowknife, Prince of Wales Northern Heritage Centre.

- ROWLEY, Susan, 1992 1991 Igloolik Field Survey, unpublished report on file, Yellowknife, Prince of Wales Northern Heritage Centre.

- ROWLEY, Susan, 1993a Report of the 1992 Field Season, unpublished report on file, Yellowknife, Prince of Wales Northern Heritage Centre.

- ROWLEY, Susan, 1993b Archaeological Work on Igloolik Island – 1993, unpublished report on file, Yellowknife, Prince of Wales Northern Heritage Centre.

- ROWLEY, Susan, 1995 Report on the Impacts of Proposed Developments in the Vicinity of the Igloolik Airport on the Cultural Heritage of Igloolik, unpublished report on file, Gatineau, Canadian Museum of Civilization.

- ROWLEY, Susan, 1997 Igloolik Archaeology Project – Excavations at NiHf-4 in 1996, unpublished report on file, Gatineau, Canadian Museum of Civilization.

- ROWLEY, Graham and Susan ROWLEY, 1997 Igloolik Island before and after Jørgen Meldgaard, in R. Gilberg and H. C. Gulløv (eds), Fifty Years of Arctic Research: Anthropological Studies from Greenland to Siberia, Copenhagen, National Museum of Denmark, Ethnographical Series, 18: 269-276.

- SAVELLE, James M., 1983 Archaeological Investigations at Roche Bay, Northwest Territories, July, 1983, unpublished report on file, Yellowknife, Prince of Wales Northern Heritage Centre.

- SAVELLE, James M. and Arthur S. DYKE, 2002 Variability in Palaeoeskimo occupation on south-western Victoria Island, Arctic Canada: causes and consequences, World Archaeology, 33(3): 508–522.

- SCHLEDERMANN, Peter, 1996 Voices in Stone: A Personal Journey into the Arctic Past, Calgary, Arctic Institute of North America, Komatik Series, 5.

- SPIESS, Arthur, 1978 Zooarchaeological evidence bearing on the Nain area Middle Dorset subsistence-settlement cycle, Arctic Anthropology, 15(2): 48-60.

- STEENSBY, Hans P., 1916 An anthrogeographical study of the origin of the Eskimo culture, Meddelelser om Grønland, 53(2): 37–228.

- SUTHERLAND, Patricia D., 1994 New Evidence for Links Between Alaska and Arctic Canada: the Satkualuk Site in the Mackenzie Delta, Paper presented at the 27th Annual Meeting of the Canadian Archaeological Association, Edmonton.

- TAYLOR, William E., 1962 Pre-Dorset occupations at Ivugivik in northwestern Ungava, in J.M. Campbell (ed), Prehistoric Cultural Relations Between the Arctic and Temperate Zones of North America, Montréal, Arctic Institute of North America, Technical Paper, 11: 80–91.

- TAYLOR, William E., 1967 Summary of archaeological field work on Banks and Victoria Islands, Arctic Canada, 1965, Arctic Anthropology, 4(1): 221-243.

- TAYLOR, William E., 1968 Arnapik and Tyara: An Archaeological Study of Dorset Culture Origins, Salt Lake City, Memoirs of the Society for American Archaeology, 22.

- TAYLOR, William E., 1972 An Archaeological Survey Between Cape Parry and Cambridge Bay, N.W.T., Canada in 1963, Ottawa, National Museum of Man, Archaeological Survey of Canada, Mercury Series.

- TAYLOR, William E., 1988 Untitled Fieldnotes, 1988, unpublished report on file, Gatineau, Canadian Museum of Civilization, Contributions include those of J. Brink and J.W. Helmer.

- TUCK, James A. and William W. FITZHUGH, 1986 Palaeo-Eskimo traditions of Newfoundland and Labrador: A re-appraisal, in Palaeo-Eskimo Cultures in Newfoundland, Labrador and Ungava, St.John's, Memorial University of Newfoundland, Reports in Archaeology, 1: 161-167.

- TUCK, James A. and Ralph T. PASTORE, 1985 A nice place to visit, but… Prehistoric extinctions on the Island of Newfoundland, Canadian Journal of Archaeology, 9(1): 69-80.

- TUCK, James A. and Peter RAMSDEN, 1990 A Comment on the Pre-Dorset/Dorset Transition in the Eastern Arctic, Paper presented at the 23rd Annual Meeting of the Canadian Archaeological Association, Whitehorse.

- WENZEL, George, 1979 Analysis of a Dorset-Thule structure from northwestern Hudson Bay, in A.P. McCartney (ed.), Thule Eskimo Culture: An Anthropological Retrospective, Ottawa, National Museums of Canada, Archaeological Survey of Canada, Mercury Series, 88: 122-133.

- WHALLON, Robert, 1972 A new approach to pottery typology, American Antiquity, 37(1): 13-33.

- WHITRIDGE, Peter, 1999 The prehistory of Inuit and Yupik whale use, Revista de Arqueologia Americana, 16: 99-154.

List of figures

Figure 1

Map of the Central Canadian Low Arctic

Figure 2

Proposed typology (tree format) of Palaeoeskimo structural types

Figure 3

Representations of the proposed Palaeoeskimo structural types. Each illustration depicts one of several ways in which a specific type can be manifested, depending upon the form of the peripheral boundary marker and internal features (individual structures are not to scale). Type 13 is not illustrated given its highly variable nature.

List of tables

Table 1

Pre-Dorset structures by type*

Table 2

Transitional period structures by type*

Table 3

Early Dorset structures by type*

Table 4

Middle Dorset structures by type*

Table 5

Late Dorset structures by type*

Table 6

Terminal Dorset structures by type*