Abstracts

Abstract

The present study focused on examining different ways in which various coping strategies helped university students manage different types of stressful events and promote positive coping outcomes (e.g., coping effectiveness, emotions, health, and well-being) in their daily lives. The study adopted and tested an optimal matching model of stress and coping and used a repeated-assessment field approach. According to the participants’ descriptions and appraisals of events, daily hassles were classified into several groups: (a) academic stressors, (b) interpersonal stressors, (c) uncontrollable or less controllable stressful events, (d) controllable stressful events, and (e) stressful events damaging one’s self-esteem.Overall, the findings support the optimal matching model. A match or fit between the demand of a stressor and the function of a coping strategy tended to result in positive outcomes.A wider range of leisure coping strategies provided more positive outcomes for dealing with various types of daily hassles than general coping strategies (not directly associated with leisure) did. Some types of coping strategies (e.g., positive reinterpretation, leisure empowerment, and leisure mood enhancement) had a positive impact on managing all or many of the different types of stressful events experienced.

Résumé

Cette étude s’est penchée sur la façon dont diverses stratégies d’adaptation aident les étudiants à faire face au stress et sur les répercussions positives de ces stratégies (efficacité de la stratégie, émotions, santé et bien-être) dans leur vie quotidienne. Pour ce faire, les responsables de l’étude ont utilisé et mis à l’essai un modèle optimal d’appariement des sources de stress et des différentes stratégies d’adaptation au moyen d’une approche pratique à évaluations répétées. Les facteurs quotidiens de stress ont été regroupés en fonction des descriptions et de l’évaluation qu’en ont fait les participants : (a) facteurs académiques, (b) facteurs interpersonnels, (c) événements stressants imprévisibles ou peu prévisibles, (d) événements stressants prévisibles et (e) événements stressants qui affectent l’estime de soi. De façon générale, les résultats appuient le modèle optimal d’appariement. En effet, la correspondance entre les sources de stress et les fonctions des différentes stratégies a tendance à entraîner des répercussions positives. Aussi, un grand nombre de stratégies d’adaptation par le loisir se sont avérées plus efficaces pour gérer divers facteurs quotidiens de stress que les stratégies d’adaptation générales (non liées directement au loisir). Certaines stratégies d’adaptation (la réinterprétation positive, le renforcement de l’importance du loisir et l’amélioration de l’humeur au moyen du loisir, par exemple) ont eu des effets positifs sur la façon dont les participants ont pu gérer tous ou la majorité des événements stressants vécus.

Resumen

Este estudio se enfoca sobre la manera en que diversas estrategias de adaptación ayudan a los estudiantes a hacer frente al estrés así como sobre las repercusiones positivas de estas estrategias (eficacia de la estrategia, emociones, salud y bienestar) en su vida cotidiana. Para llevar a cabo esto, los responsables del estudio utilizaron y pusieron a prueba un modelo óptimo de apareamiento de las fuentes del estrés y de las diferentes estrategias de adaptación por medio de un enfoque práctico de evaluaciones repetidas. Los factores cotidianos del estrés se reagruparon en función de las descripciones y de la evaluación que hicieron los participantes : (a) factores académicos, (b) factores interpersonales, (c) sucesos creadores de estrés imprevisibles o poco previsibles, (d) sucesos creadores de estrés previsibles y (e) sucesos creadores de estrés que afectan la autoestima. De manera general, los resultados apoyan el modelo óptimo de apareamiento. De hecho, la correspondencia entre las fuentes de estrés y las funciones de las diferentes estrategias con tendencia a ocasionar repercusiones positivas. También, un gran número de estrategias de adaptación por el ocio se han revelado más eficaces para administrar diversos factores cotidianos de estrés que las estrategias de adaptación general (no ligadas directamente al ocio). Algunas estrategias de adaptación (la reinterpretación positiva, el fortalecimiento de la importancia del ocio y el mejoramiento del humor por medio del ocio, por ejemplo) han tenido efectos positivos sobre la manera de como los participantes han podido administrar todos o la mayoría de los sucesos creadores de estrés que han vivido.

Article body

Introduction

Increasingly, many people in contemporary society experience higher levels of stress (Robinson and Godbey, 1997; Zuzanek and Smale, 1997). For example, the Conference Board of Canada has recently reported that the number of Canadians experiencing a moderate to high level of stress has increased from only 27 percent in 1988 to almost half of the respondents in 1999 (McBride-King and Bachmann, 1999). Increasing demands and pressure and even minor stressors in people’s daily lives have been shown to be a major source of stress (e.g., Pillow, Zautra, and Sandler, 1996; van Eck, Nicolson, and Berkhof, 1998). To effectively deal with the experience of stress, the use of coping strategies appears to be an essential life-survival technique for people in contemporary society.

The purpose of the present study was to examine how individuals cope with different types of stress to maintain good health and well-being. Specifically, this study focused on examining different ways in which coping strategies helped university students manage stressful events in their daily lives. Broadly speaking, coping strategies can be categorized into general coping strategies and leisure coping strategies. From perspectives of leisure research and services, this distinction is important for determining the extent to which, and how, leisure coping strategies (e.g., leisure-generated social support) help people cope with stress, in comparison to coping strategies not directly associated with leisure (e.g., planning and active coping).

In order to examine the impact of various coping strategies on dealing with different types of stressful encounters in university students’ daily lives, this study adopted and tested an optimal matching model of stress and coping. According to the optimal matching model, a match or fit between the demand of a stressor and the function of a coping strategy results in positive outcomes (e.g., stress reduction and good health; Cohen and McKay, 1984; Cutrona, 1990; Cutrona and Russell, 1990; Hobfoll and Vaux, 1993; Kohn, 1996; Thoits, 1986; Vaux, 1988). For example, to deal with a stressful event which damages one’s self-esteem, a coping strategy which provides esteem support is assumed to be effective for maintaining good health because damaged self-esteem matches with or requires the use of esteem support.

Another unique aspect of this study was the use of an innovative research method, namely, a repeated-assessment field approach. This approach provided an opportunity for more comprehensively measuring the types of stressful events participants had experienced, and coping strategies they had used to manage the experience of stress in their everyday lives.

First, this paper begins with reviewing theoretical bases of the present study: (a) general coping strategies, (b) leisure coping strategies, (c) coping with daily hassles, (d) outcomes of stress-coping, and (e) optimal matching model.

General Coping Strategies

Stress and coping researchers generally agree that there are two major functions of coping: problem-focused and emotion-focused (cf., Lazarus and Folkman, 1984; Parker and Endler, 1996). Problem-focused coping functions to change a troubled person-environment relationship by directly acting on the environment or oneself. In contrast, emotion-focused coping operates to change either commitment patterns (e.g., one avoids thinking about a threat), or the meaning or interpretation of what is happening, which may mitigate the stress, although the actual reality of the relationship is not changed. The latter involves a less threatening or more benign reappraisal, such as positive reinterpretation, denial, and distancing. Western values tend to favor taking a direct action against a problem rather than re-appraising the meaning of a problem (Lazarus, 1993a). However, there has been ample evidence that emotion-focused coping can be more effective than problem-focused coping under certain conditions, for example, when a stressful encounter is less changeable and/or uncontrollable (e.g., Bolger, 1990; Folkman and Lazarus, 1988a; Mattlin, Wethington, and Kessler, 1990).

Of various coping instruments developed (e.g., Amirkhan, 1990; Endler and Parker, 1990; Folkman and Lazarus, 1988b; McCrae, 1984), the Coping Orientation for Problem Experiences (COPE) Inventory (Carver, Scheier, and Weintraub, 1989) is a theoretically based multidimensional coping instrument. In the COPE inventory, five scales measure “conceptually distinct aspects of problem-focused coping (active coping, planning, suppression of competing activities, restraint coping, seeking of instrumental social support); five scales measure aspects of what might be viewed as emotion-focused coping (seeking of emotional social support, positive reinterpretation, acceptance, denial, turning to religion); and three scales measure coping responses that arguably are less useful (focus on and venting of emotions, behavioral disengagement, mental disengagement)” (Carver et al., 1989, p. 267). Carver et al. (1989) have suggested that these thirteen scales should be used separately to measure distinct coping activities rather than combining them into broader categories (i.e., problem-focused and emotion-focused) so that researchers can “study the diversity of potential coping responses separately” (p. 268). This inventory has been shown to have good psychometric properties (Carver and Scheier, 1993; Carver, Scheier, and Pozo, 1992).

Leisure Coping Strategies

In addition to general coping strategies, leisure appears to provide opportunities for effectively coping with stress. Iwasaki and Mannell (2000) have proposed that these “ways” in which leisure potentially helps people cope with stress may be classified into various categories or dimensions.

Self-determination disposition. Coleman and Iso-Ahola (1993) have suggested that a leisure-generated self-determination disposition (i.e., people’s belief or orientation that their leisure pursuits are mainly self-determined or autonomous) is one of the two important factors of leisure that help people cope with stress. The self-determination disposition is closely linked to freedom of choice, a sense of control, and intrinsic motivation which have been shown to be major properties of leisure (e.g., Freysinger and Flannery, 1992; Iso-Ahola, 1980; Weissinger and Bandalos, 1995). Coleman (1993) found that the leisure-generated self-determination disposition helped people maintain good health under stressful circumstances.

Social support. In Coleman and Iso-Ahola’s (1993) model of leisure and health, leisure-generated social support is another stress-coping factor. More recently, Iso-Ahola and Park (1996) have distinguished between leisure friendship (people’s belief that their friendships developed through leisure provide them with social support) and leisure companionship (discretionary and enjoyable shared leisure experiences as a form of social support). The former represents a relatively stable personality disposition or coping resource developed through one’s socialization process, whereas the latter represents a situation-specific coping strategy at the time of dealing with a stressful encounter. Leisure companionship was found to moderate the effect of stress on physical health in Iso-Ahola and Park’s (1996) study.

Also, there appears to be another important dimension of leisure-generated social support; that is, social support network developed through leisure. Social support literature suggests that social support is a multidimensional concept (e.g., Caplan, 1974; Cohen and McKay, 1984; Pierce, Sarason, and Sarason, 1996; Thoits, 1982; Veiel and Baumann, 1992; Weiss, 1974). At the macro or larger social level, it is important to consider supportive network resources or social embeddedness (i.e., social networks that individuals have with their significant others). At the micro or dyadic relationship level, however, supportive relationships (e.g., wife-husband, partners, child-mother, child-father, friends) must be considered. In addition, it is important to distinguish between the actual reception of supportive actions (enacted support or received support) and individuals’ perceptions of available social support (perceived support). It has been shown that those different types of social support influence the nature and process of stress-health relationships differently (e.g., Bolger and Eckenrode, 1991; Smith, Fernengel, Holcroft, Gerald, and Marien, 1994; Wethington and Kessler, 1986). Within the framework of leisure, leisure friendship, leisure companionship, and leisure-generated support network represent each of perceived support, enacted support, and supportive network, respectively.

Empowerment. From a feminist perspective, Henderson and Bialeschki (1991) have argued that “women may gain empowerment through a sense of entitlement to leisure within their lives” (p. 51) and, in turn, “opportunities for empowerment through the leisure aspects of women’s lives may have a relationship to other areas of women’s lives” (p. 62). Similarly, Freysinger and Flannery (1992) found that leisure can help women develop personal agency which empowers them to challenge or resist a falsified sense of self and the demands of their lives, as well as to regain or create a valued sense of self. Also, they have suggested that the empowerment and resistance through leisure can help women maintain their mental health. The distinction between resistance to imposed constraints and resistance through leisure (Shaw, 1994), leisure as a means of self-expression (Samdahl, 1988), and personal leisure spaces (Wearing, 1998) are relevant to the conceptualization of empowerment as a coping resource, as well.

Also, coping resources discussed in stress and coping literature support the idea that empowerment is an important element of coping styles. For example, empowerment seems to be implied in the challenge component of hardiness (people’s view that demands and changes in life are seen as challenges and opportunities for growth; Ouellette-Kobasa, 1993); and the meaningfulness component of sense of coherence (people’s willingness to face demands as challenges, and to invest their energy to overcome these demands; Antonovsky, 1990).

Palliative coping. Another dimension of leisure stress-coping seems to be palliative coping (Mannell and Kleiber, 1997). Leisure palliative coping is assumed to operate in the following ways: (a) having occupied leisure time is more constructive than participation in destructive activities (e.g., juvenile delinquency and criminal activities) or than a state of boredom as a result of having unoccupied time (Caldwell and Smith, 1995; Iso-Ahola and Crowley, 1991; Weissinger, 1995); (b) leisure is seen as a means of temporarily allowing people to escape from stressful events or painful experiences, such as loss of a job or the death of a loved one (Driver, Tinsley, and Manfredo, 1991; Sharp and Mannell, 1996); and (c) this temporal break may allow people to regroup and better handle their life problems (Endler and Parker, 1990; Folkman and Lazarus, 1980). Leisure palliative coping is assumed to help people restore their energy and perspectives to better deal with challenges in life.

Mood enhancement. The enhancement of positive mood and the reduction of negative mood through leisure pursuits appear to be another leisure stress-coping dimension. Hull and his associates (e.g., Hull, 1990; Hull and Michael, 1995) have suggested that certain types of leisure (e.g., nature-based recreation) may have a stress-reducing potential, as well as enhance positive mood and reduce negative mood. The important links between stress-coping and mood have been demonstrated in coping research, although coping researchers have paid little attention to the role of leisure (e.g., Lazarus, 1991; Stone, Kennedy-Moore, and Neale, 1995).

Coping with Daily Hassles

Historically, Holmes and Rahe’s (1967) Schedule of Recent Experiences opened up life-event approaches to stress measurement that have dominated research on stress and health for many years (Lazarus, 1990). The construction of life-event instruments is based on two general premises: (a) life changes require adjustment and (b) degree of stress quantifies the impact of life events (Vossel, 1987). Despite the enormous popularity of the life-event instruments in stress research, the life-event approaches have been widely criticized. A number of researchers have identified both conceptual and methodological pitfalls of these approaches such as paying little attention to chronic stress and everyday hassles and to individuals’ perceptions of events (e.g., Brown and Harris, 1989; Lazarus and Folkman, 1984; Monroe and McQuaid, 1994; McLean and Link, 1994; Wheaton, 1994). It became recognized that ordinary or everyday life conditions, as opposed to major life events, could produce stress which can be a cause of distress and dysfunction (Lazarus, 1993a). Consequently, stress should be conceptualized in different ways such as life event stress, chronic stress, and daily hassles (i.e., the multidimensionality of stress).

The multidimensionality of stress is elaborated in Wheaton’s (1994) discussion of “stress universe.” Wheaton has suggested that the context of stressors can beclassified into: (a) chronic stress, (b) daily hassles, (c) macrostressors, (d) nonevents, (e) traumas, and (f) stage of life issues. Chronic stress is derived from role strains (e.g., role demands and conflict in family and work; Pearlin, 1983) and ongoing life difficulties (e.g., a partner’s chronic health problem; Brown and Harris, 1978). Daily hassles refer to “irritating, frustrating, distressing demands that ... characterize everyday transactions with the environment” (Kanner, Coyne, Schaefer, and Lazarus, 1981, p. 3). Examples of daily hassles include arguments with family members, rushing to follow an established time schedule, and sleep disturbance. Macrostressors represent system stressors that occur at the macro level (e.g., recessions, structural constraints associated with gender). Nonevents are seen as something desirable or anticipated that do not occur when its occurrence is normative for individuals in a particular group (e.g., finding an intimate partner; Gersten, Langner, Eisenberg, and Orzeck, 1974). Traumas are overwhelming stressors whose impacts are extremely serious such as death of a loved one, severe illnesses or injuries, and natural disasters (see Mikulincer and Florian, 1996). Finally, there are stressors uniquely associated with stages of life issues (e.g., employment, marriage, retirement).

Of the various classifications of stress, the present study focused on examining the impact of daily hassles on health and well-being, and the ways in which different types of coping strategies help people manage the daily hassles.

Outcomes of Stress-Coping

The selection of appropriate outcomes of stress-coping is an important criterion for stress and coping research (Meneghan, 1982; Zeidner and Saklofske, 1996). According to Folkman, Lazarus, Dunkel-Schetter, DeLongis, and Gruen (1986) and Zautra and Wrabetz (1991), immediate consequences of coping actions (e.g., coping effectiveness) must be considered in coping research. Also, emotions are considered to be short-term outcomes of stress-coping (Lazarus, 1990, 1991). Folkman and Lazarus (1985) have suggested that it is useful to distinguish among threat emotions (being worried, fearful, and anxious), challenge emotions (being confident, hopeful, and eager), harm emotions (being angry, sad, disappointed, guilty, and disgusted), and benefit emotions (being exhilarated, pleased, happy, and relieved) for examining the impact of stress-coping on emotions. They have shown that differences in one’s stress-coping processes uniquely influence these four groups of emotions. Also, their factor analysis of the 15 emotions has suggested the existence of the above four factors of emotions.

Distinctions among various health and well-being measures have been discussed extensively (Lazarus, 1991; Lepore and Evans, 1996; Zeidner and Saklofske, 1996). The traditional medical model and life event approach rely on a pathological orientation which focuses on explaining why and how people suffer from illnesses (i.e., an examination of the effects of negative life events on pathological outcomes such as illness symptoms). In contrast, researchers such as Antonovsky (1987) and Barrera (1988) have argued that it is important to focus more on explaining why and how individuals move toward the positive end of health-illness continuum, and on examining the effects of stress on positive human functioning and well-being. That is, health should be conceptualized as more than just the absence of illness. In consistent with this view, recent stress and coping research has evolved to increasingly emphasize individuals’ resilience, adaptive capacity, resistance resources, constructive actions, and personal growth in the face of stressful encounters, in contrast to the early emphasis on pathological factors such as people’s vulnerabilities to stressful life events (Aldwin, 1994; Holahan and Moos, 1994; Lazarus, 1993b; Parker and Endler, 1996). Thus, the present study included psychological well-being and physical and mental ill-health as other outcomes of stress-coping.

Optimal Matching Model

Of various perspectives of stress-coping, a number of researchers have suggested the importance of an optimal matching model of stress and coping (e.g., Cohen and McKay, 1984; Cutrona, 1990; Hobfoll and Vaux, 1993; Kohn, 1996; Thoits, 1986; Vaux, 1988). The basic tenet of this model is that coping strategies are effective in managing stressors only when the demands of stressors match with the specific functions of coping strategies. Cutrona and Russell’s (1990) review of over 40 studies, which examined the associations between the specific components of social support and different aspects of stress, is particularly note-worthy. They found that about two-thirds of the studies reviewed supported the optimal matching model. For instance, for uncontrollable events, emotional support plus the support function that matched with the specific domain (e.g., financial assistance for financial strain) predicted positive outcomes. For controllable events, however, they reported that instrumental support and esteem support were associated with positive outcomes.

In the optimal matching model, a match or fit between the demands of stressors and the functions of coping (either leisure coping or general coping) was hypothesized to result in positive outcomes (e.g., positive emotions, good health, and/or well-being). A test of this model requires distinctions among different types of events, appraisals of events, types of coping strategies, and types of coping outcomes. Then, analysis is to be performed to determine which types of coping strategies are effective in coping with specific types of events and promoting positive coping outcomes.

Hypotheses

Based on the optimal matching model of stress and coping, the main hypothesis of the present study tested was that: the use of coping strategies whose functions match with the demands of stressors would predict positive coping outcomes. When the participants dealt with academic stressors and/or controllable stressful events, it was hypothesized that the use of direct or problem-focused strategies would predict positive coping outcomes. When they coped with interpersonal stressors, however, strategies to provide social support were hypothesized to predict positive coping outcomes. When they encountered uncontrollable or less controllable stressful events, emotion-oriented strategies would be associated with positive outcomes. Finally, esteem support was hypothesized to predict positive outcomes when the participants coped with stressful events damaging their self-esteem.

Methods

Volunteer undergraduate students (women = 63, men = 22) at a Canadian University participated in this study. The study consisted of three stages: initial assessment, periodic observation, and post-study assessment. First, the participants were administered scales that measured their belief about how they use leisure to cope with stress. Health and well-being measures were also collected. Then, during the periodic observation phase, they monitored the most stressful events that they had experienced in the preceding weeks, and described how they coped with each event. They indicated types of general coping and leisure coping strategies used in dealing with each event. They also reported immediate outcomes of coping (coping effectiveness, coping satisfaction, and stress reduction) and emotions, following the completion of coping with each stressful event. Weekday events were recorded on Thursdays, and weekend events on Sundays for two weeks (four events in total for each participant). The total number of events reported was 340 (85 participants X 4 events). The purpose of using this repeated-assessment field approach was to comprehensively capture participants’ stress-coping strategies in their everyday lives. During the post-assessment stage, the participants responded to the health and well-being measures again. Below, Cronbach alpha reliability coefficients reported were calculated using the data from the present study unless otherwise stated.

Measures

Daily hassles. During the periodic observation phase, the participants were asked to identify and describe the most stressful event that they had experienced in the past weekday or weekend in an open-ended format, and to rate the stress level of the event using a 10-point Likert-like scale (1 = “very minor” to 10 = “extremely stressful” where 10 is equivalent to the death of a loved one).

Event appraisal. The Event Appraisal Scale (EAS) was used to measure the extent to which a stressful event was controllable, and the extent to which a stressful event damaged one’s self-esteem. There has been evidence that these two factors are important for examining stress-health relationships (e.g., Bolger, 1990; Folkman and Lazarus, 1988a; Mattlin et al., 1990). For example, in Cutrona and Russell’s (1990) study of an optimal matching model, they found that the effectiveness of particular coping strategies differed according to whether a stressful event was controllable and whether an event damaged one’s self-esteem. The controllability of an event (alpha coefficient = 0.79) was measured by three items: (a) “I had control over whether or not this event happened;” (b) “I had no control over the occurrence of this event (reverse item);” and (c) “I was not able to control the occurrence of this event” (reverse item). Self-esteem (alpha coefficient = 0.90) was assessed by two items: (a) “This event made me feel good about myself;” and (b) “This event made me proud of myself.” The participants responded to the EAS with respect to the most stressful event that they had experienced in the past weekday or weekend during the periodic observation phase, using a 7-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (“very strongly disagree”) to 7 (“very strongly agree”).

Leisure coping. The Leisure Coping Scales (LCS; Iwasaki and Mannell, 2000) were used for measuring various ways in which leisure helps people cope with stress (i.e., the dimensions of leisure stress-coping): (a) a leisure-generated self-determination disposition (seven items), (b) leisure empowerment (seven items), (c) leisure friendship (four items for each of emotional support, esteem support, tangible aid, and informational support), (d) leisure palliative coping (six items), (e) leisure companionship (six items), and (f) leisure mood enhancement (six items; see Table 1 for sample items and Cronbach alpha coefficients of the dimensions). The first three dimensions (a) to (c) were included in the Leisure Coping Belief Scale (LCBS), and the last three dimensions (d) to (f) in the Leisure Coping Strategy Scale (LCSS). The LCBS measures individuals’ dispositional and relatively stable belief about gaining stress-coping benefits through leisure involvements, whereas the LCSS measures the extent to which leisure involvements help people cope with stress at the time of facing a stressful event in a specific situation. This distinction is consistent with the accumulated evidence in stress and coping literature that personality dispositions and the actual use of coping strategies in specific situations are two distinguishable major factors for explaining the stress-health relationship (e.g., Carver et al., 1989; Endler and Parker, 1994; Lazarus, 1993a). The participants completed the LCBS during the initial assessment stage, and the LCSS with respect to the most stressful event of the weekday or weekend they identified during the periodic observation phase, using a 7-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (“very strongly disagree”) to 7 (“very strongly agree”).

Social support networks developed through leisurewere measured using the Leisure Support Network Assessment Scale (LSNAS), which is a modified format of Vaux and Harrison’s (1985) Social Support Resources Scale. The LSNAS is designed to assess (a) size of support network; (b) frequency, closeness, balance, complexity, and the nature of relationship such as husband-wife and close friend; and (c) levels of satisfaction with different aspects of social support (i.e., emotional support, socializing, practical assistance, financial assistance, and advice/guide). The size of support network was measured by asking participants to list initials of up to 10 significant others who provide them with each of emotional support, socializing, practical assistance, financial assistance, and advice/guide. Frequency, closeness, balance, and complexity of relationship were measured by a 5-point Likert-like scale for each of the significant others (e.g., 1 = “about once a month or less” to 5 = “about everyday” for frequency; 1 = “not close at all” to 5 = “extremely close” for closeness). One-item Likert-like scales (1 = “not at all satisfied” to 5 = “extremely satisfied”) were used to measure levels of satisfaction with the different aspects of social support (i.e., emotional support, socializing, practical assistance, financial assistance, and advice/guide).

Table 1

Sample items and Cronbach alpha reliability coefficients for the dimensions of the Leisure Coping Scales (LCS)

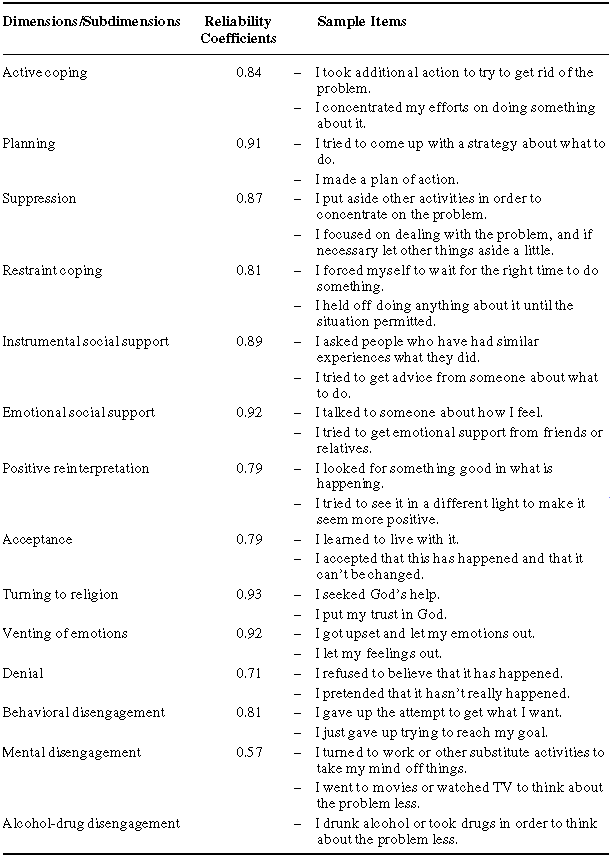

General coping. The Coping Orientation for Problem Experiences (COPE; Carver et al., 1989) was used for assessing general coping strategies that are not directly associated with leisure (see Table 2 for sample items and alpha coefficients of the dimensions). The COPE Inventory consists of various types of general coping strategies: (a) active coping, (b) planning, (c) suppression of competing activities, (d) restraint coping, (e) seeking social support for instrumental reasons, (f) seeking social support for emotional reasons, (g) positive reinterpretation and growth, (h) acceptance, (i) turning to religion, (j) focus on and venting of emotions, (k) denial, (l) behavioral disengagement, (m) mental disengagement, and (n) alcohol-drug disengagement. There are four items for each type except for alcohol-drug disengagement which has only one item. The participants responded to the COPE during the periodic observation phase, using a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = “I did not do this at all” to 5 = “I did this a great deal”).

Coping outcomes. Immediate outcomes of stress-coping were measured by the Coping Outcome Assessment Scale (COAS). The studies by Folkman et al. (1986) and Zautra and Wrabetz (1991) guided the development of the COAS which consists of three dimensions: (a) coping effectiveness (the extent to which people’s coping strategies are effective); (b) coping satisfaction (the extent to which they are satisfied with coping outcomes); and (c) stress reduction (the extent to which their stress levels are reduced). Each dimension has three items. Sample items for each dimension are: “My coping response was ineffective” (coping effectiveness, reverse item, alpha coefficient = 0.76); “I am satisfied with my response to this event” (coping satisfaction, alpha coefficient = 0.75); and “My feelings of stress were reduced” (stress reduction, alpha coefficient = 0.84). The participants responded to the COAS following the completion of coping with the most stressful event that they had experienced in the past weekdays or weekends during the periodic observation phase, using a 7-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (“very strongly disagree”) to 7 (“very strongly agree”).

Emotions. The participants’ emotions were measured by the Emotion Assessment Scale (EAS) which consists of a series of adjectives representing 15 emotions. Folkman and Lazarus’ (1985) framework of stress-coping and emotions guided the selection of emotions. The participants responded to the EAS following the completion of coping with the most stressful event that they had experienced in the past weekday or weekend during the periodic observation phase, using a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (“not at all”) to 5 (“a great deal”). Alpha coefficients of 0.81, 0.77, 0.77, 0.87 were reported for threat emotions (being worried, fearful, and anxious), challenge emotions (being confident, hopeful, and eager), harm emotions (being angry, sad, disappointed, guilty, and disgusted), and benefit emotions (being exhilarated, pleased, happy, and relieved), respectively.

Physical health. Physical health was measured by the Pennebaker Inventory of Limbic Languidness (PILL: Pennebaker, 1982). The PILL is a 54-item self-report checklist designed to measure the frequency of experiencing a variety of common physical symptoms and diseases. The participants reported whether or not and how often they had experienced physical health problems along a 5-point Likert-like scale ranging from 0 (“have never or almost never experienced the symptom”) to 4 (“more than once every week”) for each of the 54 symptoms. As recommended by Pennebaker (1982), an overall index of physical health problems for each participant was calculated by adding weighted scores ranging from 0 to 4 (see the above rating schemes) for all symptoms reported. The participants responded to the PILL in the initial assessment stage (alpha coefficient = 0.93) and in the post-study assessment stage (alpha coefficient = 0.95).

Table 2

Sample items and Cronbach alpha reliability coefficients for the dimensions of the Coping Orientation for Problem Experiences (COPE)

Mental health. Mental health was measured by the Mental Health Inventory (MHI; Veit and Ware, 1983). The MHI is a 38-item measure of mental health developed for the use in general populations. Of five correlated factors, namely, (a) anxiety (10 items), (b) depression (5 items), (c) loss of behavioral or emotional control (9 items), (d) general positive affect (11 items), and (e) emotional ties (3 items), only the first three factors were used as indicators of mental ill-health in this study. This decision was based on the approach taken in this study to distinguish between mental ill-health and psychological well-being, as suggested by Lazarus (1991), Lepore and Evans (1996), and Zeidner and Saklofske (1996). The last two factors of the MHI represent psychological well-being which was operationalized in this study by the Scales of Psychological Well-being (SPWB; Ryff, 1989) to be described below. The participants went through a list of statements and indicated how often they had felt or behaved in a particular way during the past week, ranging from 0 (“rarely or none of the time: less than 1 day”) to 4 (“almost all of the time: everyday”). The participants responded to the MHI in the initial assessment stage (alpha coefficient = 0.92) and in the post-study assessment stage (alpha coefficient = 0.86).

Psychological well-being. The Scales of Psychological Well-being (SPWB; Ryff, 1989) were used to measure psychological well-being. The SPWB consists of six scales:

self-acceptance (possesses a positive attitude toward the self; acknowledges and accepts multiple aspects of self including both good and bad qualities);

positive relations with others (has warm, satisfying, and trusting relationships with others; capable of strong empathy, affection, and intimacy);

autonomy (is self-determining and independent; able to resist social pressures to think and act in certain ways; regulates behaviors from within);

environmental mastery (has a sense of mastery and competence in managing the environment; makes effective use of surrounding opportunities);

purpose in life (has goals in life and a sense of directedness; has aims and objectives for living);

personal growth (sees self as growing and expanding; is open to new experiences; has sense of realizing her/his potential).

Of three versions of the scales, this study used the 3-item scales. The participants went through a list of statements and indicated how often they had felt in a particular way during the past week using a Likert-like scale, ranging from 1 (“rarely or none of the time: less than 1 day”) to 5 (“almost all of the time: everyday”). They responded to the SPWB in the initial assessment stage (alpha coefficient = 0.76) and in the post-study assessment stage (alpha coefficient = 0.77).

Results

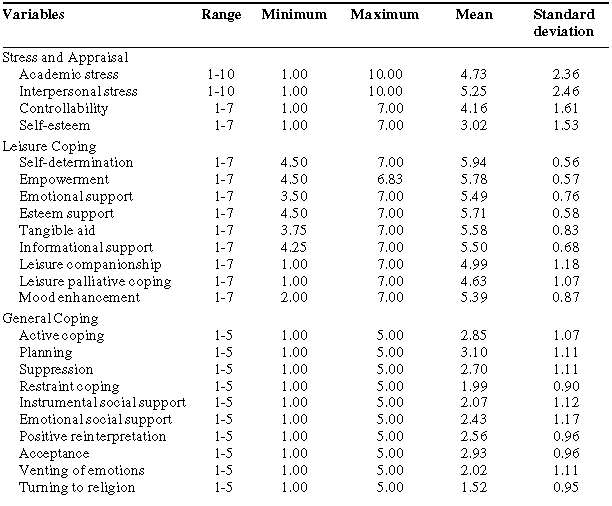

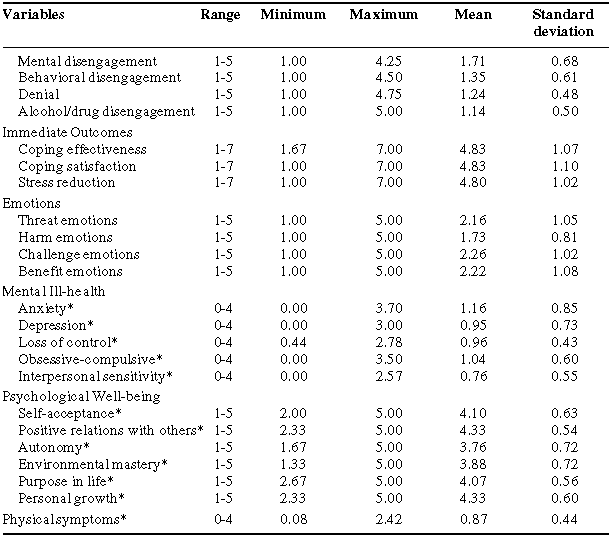

In order to examine the impact of various coping strategies (general and leisure coping) on dealing with different types of stressful events in university students’ daily lives, an optimal matching model was adopted and tested. The test of an optimal matching model requires the classification of stressful events and coping strategies into various types or groups, and the prediction of outcome indicators (e.g., coping effectiveness, health) by specific coping strategies for different event types (cf., Cutrona and Russell, 1990). Descriptive statistics of the variables examined are reported in Table 3.[1]

Table 3

Summary of descriptive statistics for the variables examined

First, stressful events reported during the periodic observation phase were classified into various types including: academic stressors (n = 120), interpersonal stressors (n = 61), competence stressors other than academic (n = 24), cognitive stressors (n = 18), environmental annoyances (n = 27), financial problems (n = 4), illnesses/injuries (n = 6), and illnesses of a loved one (n = 4), according to the participants’ descriptions of the most stressful events that they had experienced during the past weekdays or weekends. Because academic stressors and interpersonal stressors were the two most frequently reported events, the following analyses focused on these two types of stressful events only. That is, the rest of event groups did not have sufficient cases to proceed analysis with statistical confidence.

Other event classifications represented the different appraisals of events based on the levels of controllability and self-esteem, which have been suggested to be important concepts for examining an optimal matching model (e.g., Bolger, 1990; Cutrona, 1990; Cutrona and Russell, 1990; Folkman and Lazarus, 1988a; Mattlin et al., 1990). In comparison to the objective classification of events based on the participants’ descriptions of events encountered (academic and interpersonal stressors), the classification based on event appraisals represented a subjective assessment of events experienced.

Below or above mean scores (means = 4.16 and 3.02 for controllability and self-esteem, respectively, on a seven-point scale) were used to distinguish between controllable events (n = 155; mean = 5.36) and uncontrollable or less controllable events (n = 129; mean = 2.72), and to identify events which damaged one’s self-esteem (n = 164; mean = 1.95). It must be cautioned that due to the over-representation of women (n = 63) in comparison to men (n = 22) in the sample, most of the stressful events that were classified into the above groups were reported by women: (a) 110 events by females and 10 by males for academic stressors, (b) 54 events by females and 7 by males for interpersonal stressors, (c) 116 events by females and 13 by males for less controllable events, (d) 141 events by females and 14 by males for controllable events, and (e) 153 events by females and 11 by males for events damaging one’s self-esteem.

A series of regression analysis were performed to examine the effects of coping strategies and resources (leisure and general coping strategies and leisure-generated social support resources) on various coping outcome measures (coping effectiveness, coping satisfaction, stress reduction, mental ill-health, psychological well-being, and physical ill-health), when the participants dealt with: (a) academic stressors (Table 4), (b) interpersonal stressors (Table 5), (c) uncontrollable or less controllable stressful events (Table 6), (d) controllable stressful events (Table 7), and (e) stressful events damaging self-esteem (Table 8).

First, stressful events that were classified into each of the five groups (a) to (e) above were selected and, then, hierarchical regression analysis was performed independently for each of the five event groups. In the prediction of coping effectiveness, coping satisfaction, stress reduction, and emotions; stress levels of the events reported were entered at the first step into a regression model to take into account stress levels of the events. Then, at the next step, the leisure and general coping strategies were entered into the model to examine a unique contribution of each coping strategy to the prediction of the coping outcomes over and above the stress levels of the events reported.

In the prediction of mental ill-health, psychological well-being, and physical symptoms at Time 2 (in the post-study assessment stage), the corresponding ill-health and well-being measures at Time 1 (in the initial assessment stage) were entered into a regression model at the first step to control individual differences in health and well-being levels prior to the periodic observation phase. Then, at the second step, stress levels of the events reported were entered to the model in order to take into account stress levels of the events reported. Finally, at the third step, each of the leisure and general coping strategies was entered to the model. In this way, it was possible to examine a unique contribution of each coping strategy to the prediction of the health and well-being indicators at Time 2, above and beyond the same health and well-being indicators at Time1 and the stress levels of the events reported. Below, all beta coefficients reported are statistically significant at the 0.05 level.

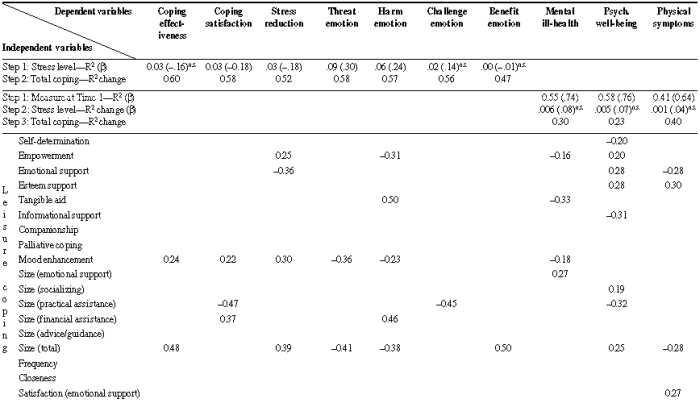

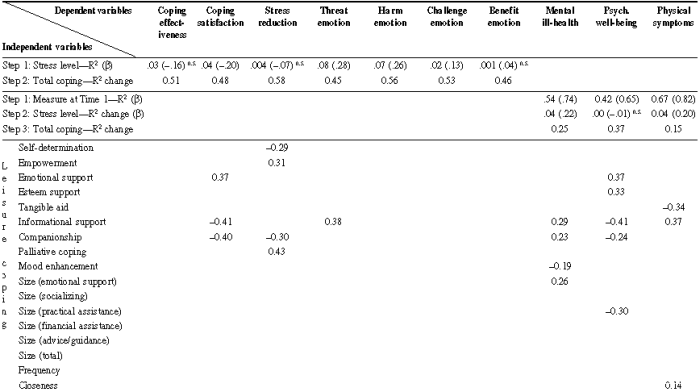

Table 4 represents the contribution of coping strategies to dealing with academic stressors. Planning predicted greater coping effectiveness (ß = 0.42) and lower threat emotions (being worried, fearful, and anxious; ßs = – 0. 44). Positive reinterpretation also appeared to promote coping effectiveness (ß = 0.27) and challenge emotion (being confident, hopeful, and eager; ß = 0.31). “Planning involves coming up with action strategies, thinking about what steps to take and how best to handle the problem” (Carver et al., 1989, p. 268), whereas positive reinterpretation aims not only at managing distress emotions, but also at construing a stressful encounter in positive ways which “lead the person to continue (or to resume) active, problem-focused coping actions” (Carver et al., 1989, p. 270). It appears that managing academic stressors requires the use of problem-focused coping strategies.

At the same time, some leisure-related coping strategies were found to provide positive outcomes in dealing with academic stressors. Leisure empowerment seemed to assist the participants in reducing stress levels (ß = 0.25), harm emotion (being angry, sad, disappointed, guilty, and disgusted; ßs = – 0.31), and mental ill-health (ßs = – 0.16), as well as in enhancing psychological well-being (ß = 0.20). Leisure empowerment appears to be an important and useful resource for overcoming life stressors including academic stressors. Also, leisure mood enhancement facilitated coping effectiveness (ß = 0.24), coping satisfaction (ß = 0.22), and stress reduction (ß = 0.30); and reduced threat emotion (ßs = – 0.36), harm emotion (ßs = – 0.23), and mental ill-health (ßs = – 0.18). The use of leisure for enhancing positive mood and/or reducing negative mood seems to be a good choice in managing academic stress.

In addition, social support network generated by leisure pursuits was found to produce positive outcomes in coping with academic stress. Specifically, the larger the size of global social network generated through leisure, the more positive coping outcomes were [i.e., the promotion of coping effectiveness, ß = 0.48; stress reduction, ß = 0.39; and benefit emotion (being exhilarated, pleased, happy, and relieved; ß = 0.50); and the suppression of threat emotion, ßs = – 0.41; harm emotion, ßs = – 0.38; and physical symptoms, ßs = – 0.28]. Also, the higher the level of satisfaction with advice or guidance provided by leisure friends, the more favorable coping outcomes were (i.e., the enhancement of stress reduction, ß = 0.27; and the reduction of threat emotion, ßs = – 0.29; mental ill-health, ß = 0.35; and physical symptoms ßs = – 0.32). On the other hand, some coping strategies were found to provide negative outcomes in dealing with academic stress. For example, venting of emotion (“the tendency to focus on whatever distress or upset one is experiencing and to ventilate those feelings;” Carver et al., 1989, p. 269) and alcohol consumption led to mental ill-health (ßs = 0.18 and 0.31, respectively).

Table 4

Hierarchical regression: Effects of coping strategies on dealing with academic stressors (n = 120)

Note: Values represent beta coefficients unless otherwise stated. All values are statistically significant at the 0.05 level unless noted with n.s. (not statistically significant).

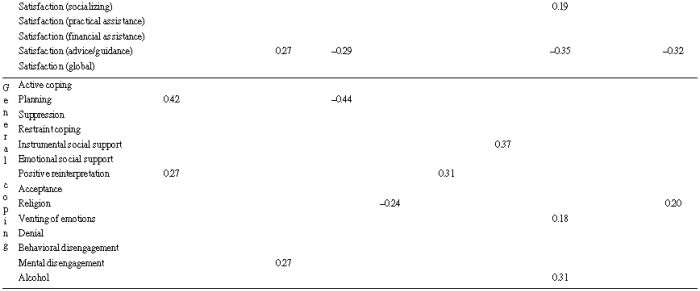

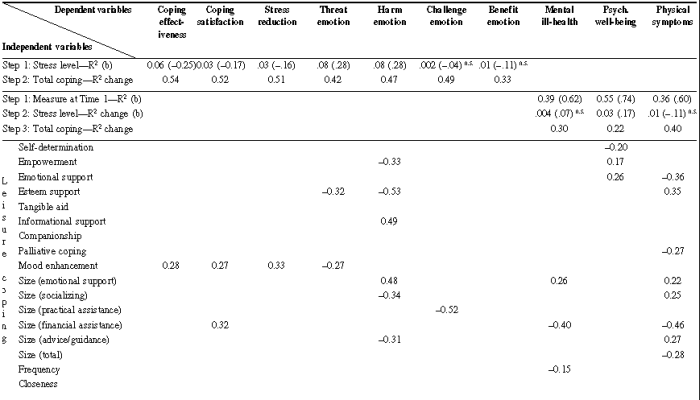

The effects of coping strategies on dealing with interpersonal stressors are presented in Table 5. It was found that leisure-related social support was useful in coping with interpersonal stressors. Emotional support (care or love by individuals’ leisure-related friends, or a strong bond or closeness with them) facilitated coping effectiveness (ß = 0.52) and reduced mental ill-health (ßs = – 0.69). Esteem support (the bolstering of people’s self-esteem or respect by their leisure-related friends) was associated with lower mental ill-health and greater psychological well-being (ßs = – 0.57 and 0.53, respectively). Tangible aid (instrumental support provided by leisure-related friends) enhanced coping effectiveness and coping satisfaction (ßs = 0.59 and 0.66, respectively). It seems that managing interpersonal stressors requires the use of leisure coping strategies useful for facilitating social support. In contrast, instrumental social support, as a form of general coping strategies, was found to be ineffective and promoted mental ill-health (ßs = – 0.43 and 0.41, respectively). Leisure-related friends (leisure companions) seem to provide more effective and useful support in dealing with interpersonal stressors than general social support to be received from non-leisure companions (i.e., one’s companions in her/his obligated activities such as co-workers). A bond, closeness, care, love, and/or understanding may be stronger among leisure-related friends than among non-leisure companions.

Another leisure coping strategy, namely, leisure mood enhancement, was also found to enhance coping effectiveness and coping satisfaction (ßs = 0.63 and 0.51, respectively) when the participants dealt with interpersonal stressors. In addition, the larger the size of social network related to practical assistance, the higher coping effectiveness and coping satisfaction were (ßs = 0.78 and 0.77, respectively). Satisfaction with advice or guidance was also associated with higher coping satisfaction, lower harm emotion, higher benefit emotion, and lower mental ill-health (ßs = 0.42, – 0.32, 0.45, and – 0.33, respectively). Restraint coping (“waiting until an appropriate opportunity to act presents itself, holding oneself back, and not acting prematurely;” Carver et al., 1989, p. 269) predicted lower threat emotion and harm emotion (ßs = – 0.41 and – 0.35, respectively), whereas those who used positive reinterpretation tended to report higher challenge emotion and benefit emotion (ßs = 0.67 and 0.53, respectively). However, some coping strategies failed to provide positive outcomes. For example, behavioral disengagement (“reducing one’s effort to deal with the stressor, even giving up the attempt to attain goals with which the stressor is interfering;” Carver et al., 1989, p. 269) was associated with higher threat emotion and harm emotion (ßs = 0.55 and 0.52, respectively). In addition, venting of emotions promoted coping ineffectiveness and coping dissatisfaction (ßs = – 0.67 and – 0.61, respectively), and denial (“denying the reality of the event;” Carver et al., 1989, p. 270) enhanced harm emotion (ß = 0.40).

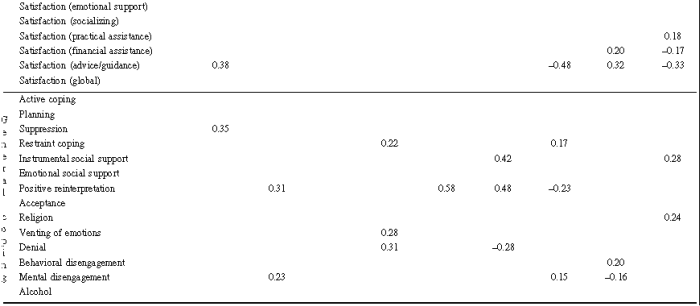

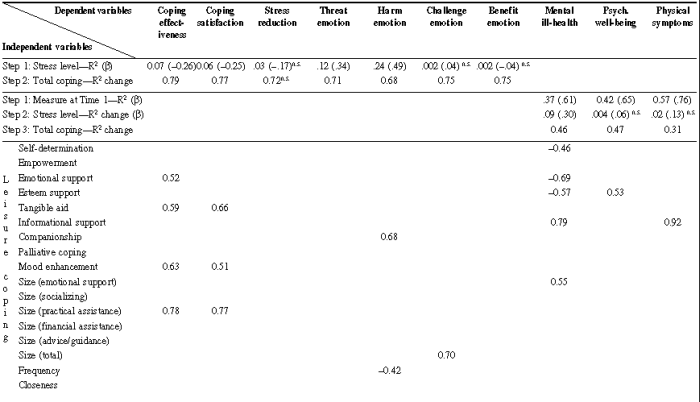

Table 6 represents the contribution of coping strategies to managing uncontrollable or less controllable stressful events in which individuals had no or little control over the occurrence of events. Positive reinterpretation was found to be one of the best strategies in coping with uncontrollable or less controllable events. It enhanced stress reduction, challenge emotion, and benefit emotion (ßs = 0.31, 0.58, and 0.48, respectively), as well as reduced mental ill-health (ßs = – 0.23). Similarly, satisfaction with advice or guidance facilitated coping satisfaction and psychological well-being (ßs = 0.38 and 0.32, respectively), and suppressed mental ill-health and physical symptoms (ßs = – 0.48 and – 0.33, respectively). Also, emotional support gained from leisure-related friends led to coping satisfaction and psychological well-being (ßs = 0.37 and 0.33, respectively), whereas the use of leisure empowerment and leisure palliative coping resulted in stress reduction (ßs = 0.31 and 0.43, respectively).

However, some coping strategies were not found to be a good choice in dealing with uncontrollable or less controllable stressful events. For example, informational support (the provision of practical advice or information) from leisure-related friends was associated with coping dissatisfaction, higher harm emotion, higher mental ill-health and physical symptoms, and lower psychological well-being (ßs = – 0.41, 0.38, 0.29, 0.37, and – 0.41, respectively). Likewise, leisure companionship (discretional, intrinsic, and/or enjoyable shared leisure) had a negative impact on coping satisfaction, stress reduction, mental health, and psychological well-being (ßs = – 0.40, – 0.30, 0.23, and – 0.24, respectively). Also, restraint coping seemed to increase harm emotion and mental ill-health (ßs = 0.22 and 0.17, respectively), and denial appeared to promote harm emotion and reduce benefit emotion (ßs = 0.31 and – 0.28, respectively). Although mental disengagement (“distracting the person from thinking about … goal with which the stressor is interfering;” Carver et al., 1989, p. 269) contributed to stress reduction (ß = 0.23), it was associated with higher mental ill-health and lower psychological well-being (ßs = 0.15 and – 0.16, respectively).

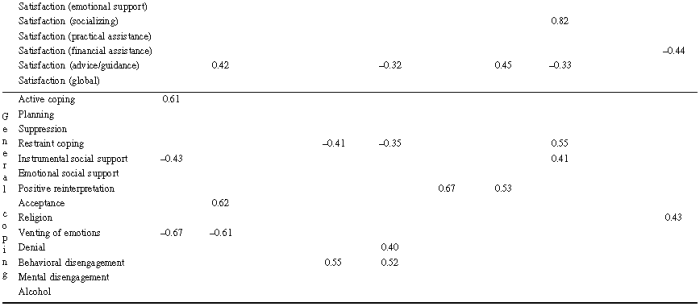

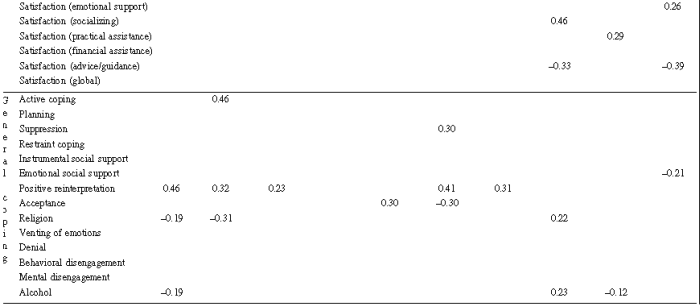

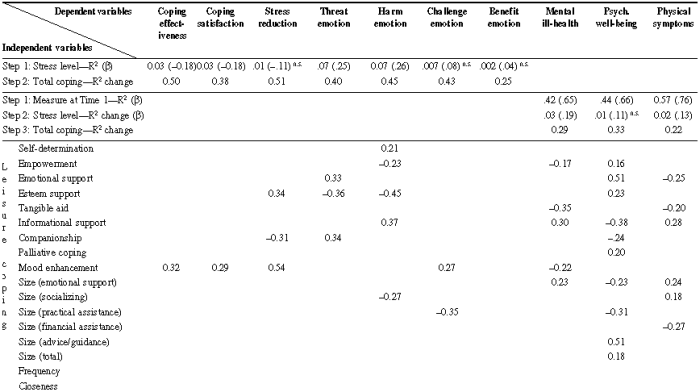

Table 7 represents the effects of coping strategies on managing controllable stressful events in which individuals had total or high control over the occurrence of events. Similar to the results reported on Table 6 (the contribution of coping strategies to managing uncontrollable or less controllable stressful events), positive reinterpretation was found to provide positive outcomes when coping with controllable stressful events. It facilitated coping effectiveness, coping satisfaction, stress reduction, challenge emotion, and benefit emotion (ßs = 0.46, 0.32, 0.23, 0.41, and 0.31, respectively). The results suggest that positive reinterpretation is effective and useful in coping with stress regardless of the extent to which people have control over the occurrence of events. Expectedly, active coping (“initiating direct action, increasing one’s efforts, and trying to execute a coping attempt in stepwise fashion;” Carver et al., 1989, p. 268) contributed to coping satisfaction (ß = 0.46) when managing controllable stressful events.

Table 5

Hierarchical regression: Effects of coping strategies on dealing with interpersonal stressors (n = 61)

Note: Values represent beta coefficients unless otherwise stated. All values are statistically significant at the 0.05 level unless noted with n.s. (not statistically significant).

Table 6

Hierarchical regression: Effects of coping strategies on dealing with uncontrollable or less controllable stressful events (n = 129)

Note: Values represent beta coefficients unless otherwise stated. All values are statistically significant at the 0.05 level unless noted with n.s. (not statistically significant).

Table 7

Hierarchical regression: Effects of coping strategies on dealing with controllable stressful events (n = 155)

Note: Values represent beta coefficients unless otherwise stated. All values are statistically significant at the 0.05 level unless noted with n.s. (not statistically significant).

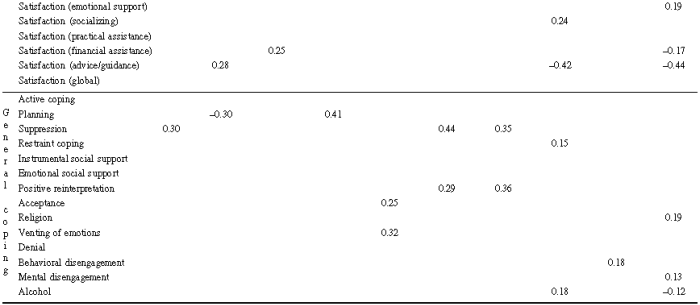

Table 8

Hierarchical regression: Effects of coping strategies on dealing with stressful events damaging one’s self-esteem (n = 164)

Note: Values represent beta coefficients unless otherwise stated. All values are statistically significant at the 0.05 level unless noted with n.s. (not statistically significant).

Some leisure-related coping strategies had a positive impact on dealing with controllable stressful events. For example, leisure mood enhancement provided positive effects on coping effectiveness, coping satisfaction, and stress reduction, and appeared to reduce threat emotion (ßs = 0.28, 0.27, 0.33, and – 0.27, respectively). Also, leisure empowerment predicted lower harm emotion and greater psychological well-being (ßs = – 0.33 and 0.17, respectively), and leisure-generated emotional support was associated with psychological well-being and physical health (ßs = 0.26 and – 0.36, respectively). Similarly, emotional social support (a form of general coping) seemed to help reduce physical symptoms (ßs = – 0.21). However, the larger network size with respect to emotional support, tended to result in increased harm emotion, mental ill-health, and physical symptoms (ßs = 0.48, 0.26, and 0.22, respectively). These findings appear to suggest that a perception or actual gain of emotional support is more important than simply the size of emotional support network to be qualified as an effective coping strategy. In other words, the quality of emotional support seems to be more important than the quantity of emotional support available.

Similar to the previous cases, some coping strategies had a negative impact on managing controllable stressful events. For example, turning to religion enhanced coping ineffectiveness, coping dissatisfaction, and mental ill-health (ßs = – 0.19, – 0.31, and 0.22, respectively). Likewise, alcohol consumption led to coping ineffectiveness, mental ill-health, and decreased psychological well-being (ßs = – 0.19, .23, and – 0.12, respectively).

Finally, Table 8 represents the contribution of coping strategies to dealing with stressful events damaging one’s self-esteem. In consistent with the idea of an optimal matching model, esteem support provided by leisure-related friends predicted stress reduction, greater psychological well-being, and lower threat emotion and harm emotion (ßs = 0.34, 0.23, – 0.36, and – 0.45, respectively). Similarly, leisure mood enhancement was associated with greater coping effectiveness, coping satisfaction, stress reduction, and challenge emotion, and lower mental ill-health (ßs = 0.32, 0.29, 0.54, 0.27, and – 0.22, respectively). Emotional support gained from leisure-related friends seemed to contribute to greater psychological well-being and lower physical ill-health (ßs = 0.51 and – 0.25, respectively), although it was associated with higher threat emotion (ß = 0.33). A damage on individuals’ self-esteem appeared to require the use of coping strategies which helped them regain their self-esteem such as esteem support, mood enhancement, and emotional support. Also, leisure empowerment was found to predict lower harm emotion and mental ill-health and greater psychological well-being (ßs = – 0.23, – 0.17, and 0.16, respectively). Furthermore, satisfaction with advice or guidance had a positive impact on coping satisfaction, and mental and physical health (ßs = 0.28, – 0.42, and – 0.44, respectively). Suppression (“putting other projects aside, trying to avoid becoming distracted by other events … in order to deal with the stressor;” Carver et al., 1989, p. 269) predicted higher coping effectiveness, challenge emotion, and benefit emotion (ßs = 0.30, 0.44, and 0.35, respectively), and positive reinterpretation had a positive association with challenge emotion and benefit emotion (ßs = 0.29 and 0.36, respectively).

On the other hand, informational support provided by leisure-related friends was associated with higher harm emotion, mental ill-health, and physical symptoms, and lower psychological well-being (ßs = 0.37, 0.30, 0.28, and – 0.38, respectively), whereas leisure companionship seemed to have negative effects on stress reduction and psychological well-being, and was associated with higher threat emotion (ßs = – 0.31, 0.34, and – 0.24, respectively). Even planning, as a problem-focused coping strategy, predicted coping dissatisfaction and higher threat emotion (ßs = – 0.30 and 0.41, respectively). It appeared that coping strategies which were not intended to regain or increase self-esteem, did not provide positive effects on dealing with stressful events damaging self-esteem. Instead, some of these strategies had a negative impact on coping with these events.

Discussion

The purpose of the present study was to examine what types of coping strategies had a positive impact on various coping outcomes for dealing with daily hassles in university students’ lives. The study focused on two major groups of coping strategies: leisure coping and general coping. Within each group, different ways in which coping strategies may help the participants manage daily hassles (dimensions of stress-coping) were identified, and the contribution of each of these dimensions examined.

The experience of daily hassles was classified into several groups according to the participants’ descriptions of the most stressful events that they had experienced during the past weekdays or weekends, and to their appraisals of these events. Five groups were identified and examined: (a) academic stressors, (b) interpersonal stressors, (c) uncontrollable or less controllable stressful events, (d) controllable stressful events, and (e) stressful events damaging self-esteem.

The outcomes of stress-coping examined consisted of: (a) coping effectiveness, (b) coping satisfaction, (c) stress reduction, (d) emotions (harm emotion, threat emotion, challenge emotion, and benefit emotion), (e) mental ill-health, (f) psychological well-being, and (g) physical symptoms. A series of hierarchical regression analysis were performed to examine the effects of each coping strategy on these outcomes of stress-coping in dealing with different types of daily hassles. This analysis procedure allowed a test of an optimal matching model of stress and coping. An optimal matching model assumes that a match or fit between the demands of stressors and the functions of coping strategies results in better coping outcomes (e.g., coping effectiveness, positive emotions, and better health/well-being) than a mismatch or misfit between the two (Cohen and McKay, 1984; Cutrona, 1990; Cutrona and Russell, 1990; Hobfoll and Vaux, 1993; Thoits, 1986; Vaux, 1988).

Overall, the findings provide evidence to mostly support the optimalmatching model of stress and coping. For example, when participants dealt with academic stressors, direct or problem-focused coping strategies such as planning and positive reinterpretation provided positive coping outcomes. Similarly, when they managed controllable stressful events, the use of active coping and positive reinterpretation significantly predicted positive coping outcomes. Dealing with academic stressors and/or controllable stressful events appears to require the use of direct or problem-focused strategies. In contrast, venting of emotions and alcohol consumption predicted negative outcomes in coping with academic stressors, and turning to religion and alcohol consumption were found to be “bad” choices in managing controllable stressful events. When the participants encountered uncontrollable or less controllable stressful events, however, the use of positive reinterpretation, satisfaction with advice or guidance, and emotional support gained from leisure-related friends were found to significantly predict positive outcomes. Also, as hypothesized, when the participants dealt with interpersonal stressors, social support (in particular, leisure-generated social support) was found to be useful. Emotional support, esteem support, and tangible aid from leisure-related friends, as well as satisfaction with advice from leisure-related friends and a larger size of support network associated with practical assistance received from leisure-related friends, all contributed to positive coping outcomes. Likewise, leisure-generated social support (in particular, esteem support from leisure-related friends) had a positive impact on helping the participants cope with stressful events in which their self-esteem was threatened.

From perspectives of leisure research and services, it is interesting and important to examine the extent to which, and how, leisure coping strategies (e.g., leisure-generated social support) help people cope with stress, in comparison to coping strategies not directly associated with leisure (e.g., problem-focused coping). The present study provided evidence that both had the positive impact on coping outcomes depending on the types of stressful events experienced. However, with regard to the relative contribution of each coping group to positive coping outcomes, the results appear to suggest that leisure coping strategies provided more positive effects on the outcome indicators in dealing with a variety of stressful events than general coping strategies (not directly related to leisure pursuits) did. For example, when the participants coped with interpersonal stressors, leisure-related social support was much more effective and useful than general social support. Leisure settings tend to be freer, more flexible, and less structured than non-leisure settings such as work environments; thus, people likely feel more comfortable with being and expressing themselves in leisure settings than in non-leisure settings (Mannell and Kleiber, 1997; Shaw, 1999). Therefore, leisure tends to provide a context or opportunity for developing strong interpersonal relationships (e.g., friendships, intimate relationships); and facilitating a closeness, love, and understanding between/among friends, family members, and/or partners. These strong relationships developed through leisure may be more effective and useful for coping with interpersonal stressors than relationships developed in non-leisure settings. This finding is consistent with results from past studies on social support. For example, Bolger and Eckenrode (1991), Rohde, Lewinsohn, Tilson, and Seeley (1990), and Rook (1987) found that discretionary activities or contacts were more effective coping strategies than less discretionary activities or contacts.

Furthermore, when the participants encountered other types of stressful events, a wider range of leisure coping strategies had a more positive impact on the outcome indicators than general coping strategies did. For example, in coping with stressful events damaging one’s self-esteem, five types of leisure coping (i.e., empowerment, emotional support, esteem support, mood enhancement, and satisfaction with advice) provided positive outcomes, whereas only two types of general coping (i.e., suppression and positive reinterpretation) did the same. Similarly, when dealing with uncontrollable or less controllable stressful events, four types of leisure coping (i.e., empowerment, emotional support, palliative coping, and satisfaction with advice) significantly predicted positive outcomes, whereas only one type of general coping (i.e., positive reinterpretation) did the same. Even when being faced with academic stressors or controllable stressful events which seem to mostly require the use of direct or problem-focused coping strategies, some types of leisure coping strategies (e.g., empowerment and mood enhancement) were found to be significantly associated with positive outcomes. These findings suggest that leisure in fact plays an important role in coping with various types of stressful events in people’s everyday lives. Clearly, future research is needed to more extensively examine the degree to which, and how, leisure coping strategies help people cope with stress, in comparison to general coping strategies.

Another interesting finding was that some types of coping strategies significantly predicted positive outcomes in dealing with all or many of the different types of stressful events experienced. Particularly, positive reinterpretation was found to be consistently associated with positive outcomes in coping with all of the five types of stressful events. Carver et al. (1989) explains that positive reinterpretation is seen as both problem-focused and emotion-focused coping strategies because it allows people to interpret a stressful event in positive ways (e.g., seeing a problem as challenge or opportunity for growth), as well as to effectively regulate negative emotions. This characteristic likely leads to positive outcomes in coping with a variety of stressful events regardless of the types of events.

Likewise, leisure empowerment facilitated positive outcomes in dealing with four types of stressful events except for interpersonal stressors, whereas leisure mood enhancement did the same except for uncontrollable or less controllable events. Having resources and energies for empowering oneself to overcome stressful events appears to be a useful and effective stress-coping technique. These valuable resources and energies can be gained through meaningful leisure involvement. Also, the enhancement of positive mood and the reduction of negative mood through leisure likely contribute to effective stress-coping. Leisure may provide an opportunity for effectively regulating one’s emotion in coping with different types of stressful events. As well, emotional support from leisure-related friends predicted positive outcomes in coping with four types of stressful events except for academic stressors. This finding demonstrates the importance of leisure-generated emotional support in managing various types of stressful encounters.

From a research design perspective, this study used an innovative approach, namely, a repeated-assessment field design. The participants monitored their stressful events experienced and coping strategies used in their everyday lives twice a week for two weeks (four events in total for each participant). This procedure (i.e., frequent assessments during the short period of time) was employed to comprehensively capture a wide range of stressful events experienced and coping strategies used in the respondents’ lives.

Another strength of this research was the grouping of stressful events experienced and coping strategies used into different types, and the classification of coping outcomes into various groups. This approach allowed to identify different types of stressful events, coping strategies, and coping outcomes, and to examine the relationships between these variables. Consequently, this approach facilitated an understanding of more detailed relationships between stress, coping, and outcome measures than an approach which focuses on an aggregated analysis of these relationships. The aggregation of stressful events experienced and/or coping strategies used may result in a loss of insight into detailed relationships between specific types of stress and coping. For example, if researchers focus only on stress levels, ignoring differences in event types, they may not be able to identify how coping strategies help individuals deal with different types of stressors. The present study showed the usefulness and importance of classifying stressors, coping strategies, and coping outcomes into different types.

The readers must recognize the limitations of this study. Because the participants consisted of a student population, the generalizability of the findings should be examined in future research using different population groups. Although the richness of the data obtained (i.e., the periodic collection of detailed information about stressors, coping, and health/well-being) was strength of the study, statistical power could have been improved by a larger sample size. The small and non-proportionate sample size did not allow the performance of separate analyses for women and men with statistical confidence. Nevertheless, this study has demonstrated that a better understanding of the relationships between stress, coping, and health/well-being appears to be facilitated by paying attention to: (a) what types of stressful events people experience, (b) what kinds of coping strategies they use, and (c) how specific types of coping strategies influence various outcomes of coping in dealing with different typesof stressful events.

Appendices

Notes

-

[1]

The inspection of correlation coefficients between independent variables suggests the possibility of multicollinearity between a few variables that belong to theoretically same broad groups of coping (i.e., problem-focused coping and support network). However, lumping several variables into broad groups of coping prevents the specification of different coping dimensions, and consequently, it prevents the testing of an optimal matching hypothesis. Thus, the original specification of variables was kept.

References

- Aldwin, C. M. (1994). Stress, coping, and development: An integrative perspective. New York: The Guilford Press.

- Amirkhan, J. H. (1990). A factor analytically derived measure of coping: The coping strategy indicator. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59, 1066-1074.

- Antonovsky, A. (1987). Unraveling the mystery of health: How people manage stress and stay well. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Antonovsky, A. (1990). Pathways leading to successful coping and health. In M. Rosenbaum (Ed.), Learned resourcefulness: On coping skills, self-control, and adaptive behavior (p. 31-63). New York: Springer-Verlag.

- Barrera, M. Jr. (1988). Models of social support and life stress: Beyond the buffering hypothesis. In L. H. Cohen (Ed.), Life events and psychological functioning (p. 211-236). Newsbury Park, CA: Sage.

- Bolger, N. (1990). Coping as a personality process: A prospective study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59, 525-537.

- Bolger, N. and Eckenrode, J. (1991). Social relationships, personality, and anxiety during a major stressful event. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61(3), 440-449.

- Brown, G. W. and Harris, T. (1978). The social origins of depression: A study of psychiatric disorders in women. New York: The Free Press.

- Brown, G. W., and Harris, T. (1989). Life events and illness. New York: Guilford.

- Caldwell, L. L., and Smith, E. A. (1995). Health behaviors of leisure alienated youth. Society and Leisure, 18, 143-156.

- Caplan, G. (1974). Support systems and community mental health: Lectures on concept development. New York: Behavioral Publications.

- Carver, C. S. and Scheier, M. F. (1993). Vigilant and avoidant coping in two patient samples. In H. W. Krohne (Ed.), Attention and avoidance: Strategies in coping with aversiveness (p. 295-320). Seattle, WA: Hogrefe and Huber.

- Carver, C. S., Scheier, M. F. and Pozo, C. (1992). Conceptualizing the process of coping with health problems. In H. S. Friedman (Ed.), Hostility, coping, and health (p. 167-187). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Carver, C. S., Scheier, M. F. and Weintraub, J. K. (1989). Assessing coping strategies: A theoretically based approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56, 267-283.

- Cohen, S. and McKay, G. (1984). Social support, stress and the buffering hypothesis: A theoretical analysis. In A. Baum, J. E. Singer, and S. E. Taylor (Eds.), Handbook of psychology and health (Vol. 4). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Coleman, D. (1993). Leisure based social support, leisure dispositions and health. Journal of Leisure Research, 25, 350-361.

- Coleman, D. and Iso-Ahola, S. E. (1993). Leisure and health: The role of social support and self-determination. Journal of Leisure Research, 25, 111-128.

- Cutrona, C. E. (1990). Stress and social support: In search of optimal matching. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 9, 3-14.

- Cutrona, C. E. and Russell, D. W. (1990). Type of social support and specific stress: Toward a theory of optimal matching. In B. R. Sarason, I. G. Sarason, and G. R. Pierce (Eds.), Social support: An interactional view (pp. 319-366). New York: John Wiley and Sons.

- Derogatis, L. R., Lipman, R. S., Rickels, K., Uhlenhuth, E. H., and Covi, L. (1974). The Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL): A measure of primary symptom dimensions. In T. Ban, F. A. Freyhan, P. Pichot, and W. Poldinger (Eds.), Modern problems of pharmacopsychiatry (vol. 7): Psychological measurements in psychopharmacology. Basel, Switzerland: S. Karger.

- Driver, B. L., Tinsley, H. E. A., and Manfredo, M. J. (1991). The paragraphs about leisure and recreation experience preference scales: Results from two inventories designed to assess the breadth of the perceived psychological benefits of leisure. In B. L. Driver, P. J. Brown, and G. L. Peterson (Eds.), Benefits of leisure . State College, PA: Venture Publishing, Inc.

- Endler, N. S., and Parker, J. D. A. (1990). Coping inventory for stressful situations: Manual. Toronto: Multi-Health Systems.

- Endler, N. S., and Parker, J. D. A. (1994). Assessment of multidimensional coping: Task, emotion, and avoidance strategies. Psychological Assessment, 6, 50-60.

- Folkman, S., and Lazarus, R. S. (1980). An analysis of coping in a middle-aged community sample. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 21, 219-239.

- Folkman, S., and Lazarus, R. S. (1985). If it changes it must be a process: Study of emotion and coping during three stages of a college examination. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 48, 150-170.

- Folkman, S., and Lazarus, R. S. (1988a). Coping as a mediator of emotion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 466-475.

- Folkman, S., and Lazarus, R. S. (1988b). Manual for the Ways of Coping Questionnaire. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

- Folkman, S., Lazarus, R. S., Dunkel-Schetter, C., DeLongis, A. and Gruen, R. J. (1986). Dynamics of a stressful encounter: Cognitive appraisal, coping, and encounter outcomes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 50, 992-1003.

- Freysinger, V. Jand Flannery, D. (1992). Women’s leisure: Affiliation, self-determination, empowerment and resistance? Society and Leisure, 15, 303-322.

- Gersten, J. C., Langner, T. S., Eisenberg, J. G., and Orzeck, L. (1974). Child behavior and life events: Undesirable change or change per se? In B. S. Dohrenwend, and B. P. Dohrenwend (Eds.), Stressful life events: Their nature and effects (p. 159-170). New York: Wiley.

- Henderson, K. A. and Bialeschki, M. D. (1991). A sense of entitlement to leisure as constraint and empowerment for women. Leisure Sciences, 12, 51-65.

- Hobfoll, S. E. and Vaux, A. (1993). Social support: Resources and context. In L. Goldberger, and S. Breznitz (Eds.), Handbook of stress: Theoretical and clinical aspects (pp. 685-705). New York: The Free Press.

- Holahan, C. J., and Moos, R. H. (1994). Life stressors and mental health: Advances in conceptualizing stress resistance. In W. R. Avison, and I. H. Gotlib (Eds.), Stress and mental health: Contemporary issues and prospects for the future (pp. 213-238). New York: Plenum Press.

- Holmes, T. H., and Rahe, R. H. (1967). The social readjustment rating scale. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 11, 213-218.

- Hull IV, R. B. (1990). Mood as a product of leisure. Journal of Leisure Research, 22, 99-111.

- Hull IV, R. B., and Michael, S. E. (1995). Nature-based recreation, mood change, and stress restoration. Leisure Sciences, 17, 1-14.

- Iso-Ahola, S. E. (1980). The social psychology of leisure and recreation. Dubuque, IA: Wm C. Brown.

- Iso-Ahola, S. E., and Crowley, E. D. (1991). Adolescent substance abuse and leisure boredom. Journal of Leisure Research, 23, 260-271.

- Iso-Ahola, S. E., and Park, C. J. (1996). Leisure-related social support and self-determination as buffers of stress-illness relationship. Journal of Leisure Research, 28, 169-187.

- Iwasaki, Y., and Mannell, R. C. (2000). Hierarchical dimensions of leisure stress coping. Leisure Sciences, 22, 163-181.

- Kanner, A. D., Coyne, J. C., Schaefer, C., and Lazarus, R. S. (1981). Comparison of two modes of stress measurement: Daily hassles and uplifts versus major life events. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 4, 1-39.

- Kohn, P. M. (1996). On coping adaptively with daily hassles. In In M. Zeidner, and N. S. Endler (Eds.), Handbook of coping: Theory, research, applications (pp. 181-201). New York: Wiley.

- Lazarus, R. S. (1990). Theory-based stress management. Psychological Inquiry, 1, 3-13.

- Lazarus, R. S. (1991). Emotion and adaptation. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Lazarus, R. S. (1993a). Coping theory and research: Past, present, and future. Psychosomatic Medicine, 55, 234-247.