Abstracts

Abstract

Pierre-Jean de Béranger (1780–1857) was revered during his lifetime as the national poet of France. His championing of the Revolution and the people earned him significant impact in the United States; an antebellum American reviewer touted Béranger’s patriotism and his struggle for liberty as a model for an American national poetry. Translations of his songs were published in various formats at various prices by major publishers who also imported French-language editions. Translators struggled to bring his politically radical and sexually scandalous texts across linguistic and cultural borders to construct a Béranger who could be understood in the United States. Yet by refusing to translate Béranger, direct-language pioneer Lambert Sauveur subversively exposed his students to the Christian roots of socialism and a defense of the Paris Commune. By century’s end, Béranger’s influence had faded to mere inclusion in delicately suggestive anthologies, but his voice lived on to inspire leftists of the next century.

Keywords:

- Translation,

- national poetry,

- song,

- politics and literature,

- Pierre-Jean de Béranger

Résumé

Pierre-Jean de Béranger (1780-1857) était considéré par ses contemporains comme le poète national de la France; aux États-Unis on apprécia tout particulièrement sa défense de la Révolution et du peuple. Déjà en 1831 un critique américain voyait dans le patriotisme de Béranger et sa lutte pour la liberté la source d’une poétique nationale américaine. Des éditeurs importèrent ses oeuvres en langue française et en publièrent des traductions en langue anglaise, sous différents formats et à différents prix, bien que la barrière linguistique et culturelle fasse parfois obstacle à l’intelligibilité de ses textes subversifs et scandaleux. En refusant de traduire Béranger, Lambert Sauveur, pionnier de la méthode directe de l’enseignement de langues, plongea ses élèves dans un discours sur les origines chrétiennes du socialisme et une défense de la Commune de Paris. Que Béranger figure dans certains recueils érotiques de la fin du siècle n’empêcha pas sa voix de résonner après 1900 et d’inspirer les radicaux du xxe siècle.

Mots-clés :

- Traduction,

- poésie nationale,

- chanson,

- politique et littérature,

- Pierre-Jean de Béranger

Article body

Pierre-Jean de Béranger (1780–1857) was revered during his lifetime as the poète national of France.[1] Celebrated originally for his lightheartedly erotic drinking songs and gentle political satires, which circulated orally, in manuscript, and in print, during the Restoration of the Bourbon monarchy he turned to more dangerous themes: heartfelt longing for lost Napoleonic greatness, mournful regret for a once-promised Republican future, and pointed attacks against Church and Crown. His published collections were twice prosecuted and twice he was imprisoned, which earned him international celebrity. During the 1820s he was a central figure in oppositional politics in France, where he was associated with liberal politicians such as Lafayette and Manuel. Later, as his reputation waned, he published new works in sympathy with mid-century Romantic socialism. Given a state funeral by the government of Napoléon III during the Second Empire, he was reviled by some as an apologist for that repressive regime, but he was nonetheless fondly remembered by others as a central figure in the Republican tradition. His songs were enlisted in political struggles elsewhere, reproduced in the original French or offered in translation. His combination of sentiment and wit, precise language and veiled allusions, classical diction and popular form afforded diverse readings of individual songs as well as diverse constructions of his oeuvre, even in France, where various versions of the chansons circulated orally and in manuscript, in expurgated and unexpurgated editions, in clandestine or spurious supplements containing explicitly erotic works as well as the censored lyrics of forbidden political songs.[2] Translators and reviewers outside France carefully selected songs, stanzas, or individual lines to which they gave new meaning by placing them in new political and bibliographic contexts.

Béranger’s praise of the Revolution and the people earned him significant impact in the United States. “Of all the French poets mentioned in American magazines during the period 1800–1848… Béranger’s name appeared most often. … [T]he praise he received is duplicated in the case of no other French literary figure.”[3] His works in French were distributed by G. P. Putnam[4] and textbook publisher Roe Lockwood;[5] a collection in French appeared in San Francisco in 1858.[6] Edgar Allan Poe used two lines from Béranger as an epigraph for “The Fall of the House of Usher.”[7] Walt Whitman praised him in an article that appeared in the Brooklyn Daily Times, calling him “the French poet of Freedom [sic]” and quoting “that great lyric of his, calling on the nations to ‘join hands’ in amity”[8] from “La Sainte Alliance des peuples.”An oft-repeated but now unverifiable tale holds that Mark Twain’s first piece as a journalist in Nevada included a reference to Béranger. Filler inserted in various newspapers in 1907 claimed that

Henry H. Ashton, a Virginia City capitalist, has in his library, richly bound in crushed Levant, those early volumes of the Virginia City Enterprise to which Mark Twain contributed. … Mr. Ashton often points out the first paragraph that Mark Twain wrote on his arrival in Virginia City. The paragraph runs: “A thunderstorm made Beranger a poet, a mother’s kiss made Benjamin West a painter and a salary of $15 a week makes us a journalist.”[9]

No copy of the Enterprise article now survives, so the story cannot be confirmed, but one might be surprised that the tale of Béranger being struck by lightning when he was a child[10] would be familiar to readers in both Washington, D.C., and Denver in 1907, and if the story is correct, to readers in Nevada in 1862.

This paper will focus on translations of Béranger’s songs published in the United States in the nineteenth century, while placing them within the broader framework of the reception of Béranger in the English-speaking world, and within the history of American literary and political culture. Many translations of Béranger published in the United States reproduced material originally published in Great Britain or were translated by British or Canadian translators; they circulated within the trans-Atlantic culture of reprinting enabled by the lack of effective copyright for works published in periodicals, or for anything first published abroad.[11] Publication in the United States offered scope for Béranger’s politically radical songs, if not always for his sexually suggestive lyrics, although translations commonly escaped in their details the strictures their translators announced. Given the number of songs offered in translation and the number of variations among different versions, only a representative sample will be treated here; the focus will be on processes of selection, exclusion, and rewriting which constructed a Béranger who would be politically and culturally comprehensible in the United States. Considering the destiny of the poète national on this side of the Atlantic will help us understand the national and international impulses at play within his work and within the field of translation.

It will be a basic assumption of this paper that every translation is an act of interpretation which adds resonance to the translated text not present in its original context while occluding some of its original significance. As Lawrence Venuti has observed: “[T]ranslation is … an act of interpretation in its own right”[12] which “changes the form, meaning, and effect of the source text”;[13] this investment of new meaning “begins with the very choice of a text for translation.”[14] By scrutinizing the choice and arrangement of texts as well as the alteration of meaning effected during border crossings between languages and cultures, this paper will attempt to tease out an understanding of Béranger’s impact in the Anglophone world.

Béranger’s songs and their translations addressed multiple publics. In France this was in part an effect of their transmission in a variety of media—orally, in manuscript, and in print. As Sophie-Anne Leterrier has noted, “[s]es texts sont … lus comme des poèmes à part entière par les bourgeois, et chantés par le peuple.”[15] In English translation, the songs were presented primarily in print, to a literate public. Nonetheless, although typically no tune was specified and little effort was made to reproduce the original meter,[16] they are nearly uniformly called songs, rarely poems, thus maintaining some simulacrum of their popular appeal. Indeed, the distinction between poetry and song was also fluid in the nineteenth-century United States, where a single poem might be declaimed, recited, or sung, distributed orally and in manuscript as well as in print, in newspapers, literary reviews, anthologies, and single-author collections, as broadside, pamphlet, or sheet music, thus fostering an appreciation of lyric as a site for public performance and a vehicle for political commitment.[17] As will be seen, the broad appeal of lyric for popular audiences would prompt consideration of Béranger as a possible model for an American national poetry, although the address to an elite public was sometimes preserved by refusing to translate his songs in reviews or in school textbooks. Translations issued in multiple physical versions, in utilitarian and more sumptuous bindings, for instance, appealed to purchasers of various means, although sometimes a cheaply produced book simulated elite artistic forms, which gave it greater prestige.

The process of translation itself helped select a public, as literary style was employed to insert Béranger within one or more anglophone poetic conventions. Thackeray foregrounded the choices facing Béranger’s translators in his Paris Sketch Book of 1840. In his double translation of “Le roi d’Yvetot,” a playful satire admired across the political spectrum in France about a king who prefers wine and women to warfare, Thackeray provides the French original and two alternative translations: a high poetic version faithful to Béranger’s versification and a rougher, blunter version he calls “The King of Brentford.” His translation of a particularly problematic passage mutes its content in the higher-toned version by veiling one scandalous phrase in Latin but renders its meaning more directly in the undraped version printed below.

Aux filles de bonnes maisons

Comme il avait su plaire,

Ses sujets avaient cent raisons

De le nommer leur père:To all the ladies of the land,

A courteous king, and kind, was he;

The reason why you’ll understand,

They named him Pater Patriae.

He pleased the ladies round him,—with manners soft and bland;

With reason good, they named him,—the father of his land.[18]

That Thackeray named these “imitations”[19] indicates his awareness of translations as transformations, not transparent reproductions.

Béranger’s delight in pleasure and his deeply felt identification with the underclass moved translators and reviewers in the English-speaking world to excise, veil, or disavow the most disturbing aspects of his alien world, without always preventing their own discourse from being contaminated. In Great Britain, the earliest reviewers, “unite[d] … [in] a professed distaste for Béranger’s licentiousness,”[20] took pains to distinguish between French corruption and British purity and offered Béranger’s songs in the original, as if shielding them from the eyes of the vulgar. For instance, an anonymous reviewer in The Edinburgh Review in 1822 alleges a deep national difference between France and Great Britain visible in everything from landscape design to dress, as well as poetry: “The grand difference is the deeper sympathy we have with Nature—and the greater veneration they pay to Art… Accordingly, their love is not love, but gallantry… These considerations go far to explain why French poetry should be different from ours—and, we must add, inferior to it.”[21] Further, French culture is, unfortunately, suffused with politics: “The pervading spirit of all is party spirit; and the common object, political purpose.”[22] Nonetheless the reviewer notes a few “brilliant exceptions to a general sentence of condemnation,”[23] including Béranger’s “light and graceful movements of gaiety and wit.”[24] He then reproduces three of Béranger’s songs, untranslated: “Les Révérends Pères,” a satire on the Jesuits, “qui fess[ent] / Et … refess[ent] / Les jolis petits, les jolis garçons”;[25] “Requête présentée par les chiens de qualité,”[26] in which the aristocrats returning from exile during the Bourbon Restoration are compared to dogs who want to run free in the Tuileries Garden; and two stanzas from “Le Dieu des bonnes gens,” in which the poet abjures the glories of the Court for the pleasures of comfortable retreat from the tyranny of kings: “Moi, pour braver des maîtres exigeans / Le verre en main, gaîment je me confie / Au Dieu des bonnes gens.”[27] Anti-clericalism, defiance of worldly power, ridicule of the aristocracy, sexual scandal—all might be savored, by the cognoscenti, in the original.

In the United States, on the other hand, Béranger was sometimes taken as a model, if with reservations. In 1831, an anonymous reviewer in the Southern Review explored notions of the national and the popular, la nation and le peuple, while reading Béranger’s verse in the context of the glaring lack of an American national poetry,[28] thus paradoxically seeking on the Continent a means of disentangling American literature from its British inheritance, all the while echoing British values. “[F]or the sake of decency,” he notes, “it is to be regretted that many [of Béranger’s songs] were not consigned to an early grave”;[29] but the best among them are “are almost invariably national.”[30] National poetry, the reviewer assures us, is easily distinguished from popular poetry due to the “etymological distinction”: “[Popular poetry] forms a constituent of the literature of almost every people,”[31] while national poetry is exemplified by “those ballads or odes which … come under the class of popular poetry, from their general diffusion among all classes, … but embody in themselves brilliant incidents of history, which confer dignity and importance upon whatever instrument may be used to communicate them.”[32] A national song is great not because of “the difficulty of its structure, nor the adornment of its style” but rather because of its ability to “call … forth … some new emotion from the fullest fountains of the heart”; “thus the unpolished song may far exceed in circulation and in influence the lofty and elaborate epic.”[33] “It blends … the admiration of the lofty with that of the lowly, and while the poet reposes in gilt binding upon the table of the boudoir, … he is echoing from the bare wall and the low roof, and calling forth from the rude and unlettered breast … fierce and uncontrollable energies.”[34] Yet as if to protect the American underclass from the corrosive influence of Béranger’s songs, and despite his call for dual address in national poetry, the reviewer does not translate the songs he offers in French. Indeed, as the reviewer warns, the national poet can undermine the nation: Béranger’s anti-clerical satires “overthrow the whole structure of the national religion” by “address[ing] themselves to … the lower class,” thus perfecting the destructive work of the philosophes and the Revolution by taking “the axe … [to] the root of the tree” and “sap[ping] the foundations” with “their operations … below the surface.”[35] Thus although he includes two of the 18 political songs indicted by Béranger’s French prosecutors, “La Cocarde blanche” and “Le Vieux Drapeau,”[36] he omits all of the songs indicted for outrage against religion or morals. The blending of high and low which the text describes is mimicked by its own slippage between the popular as wide acceptance and the popular as unlettered, the people as the whole population and as the underclass, the nation as the confluence of all classes and as a violent process of purification, so that national poetry is seen at once as the expression of the population as a whole, as something higher, and as something uncontrollable and low.

This confusion of meanings already existed within and between French and American political vocabularies; it is a confusion that persisted throughout the nineteenth century, and, it can be argued, into our own. Although dictionaries, I would maintain, typically offer definitions of political terms that betray their compilers’ affiliations even when they claim to be reflecting common usage or defending linguistic purity, examining them critically can help ground our understanding of politically fraught terms. Consider, for instance, the principal definition of “nation” in Webster’s 1828 dictionary:

NATION. 1. A body of people inhabiting the same country, or united under the same sovereign or government.[37]

Here, the emphasis is on unity within a national territory, a political position soon to be contested by South Carolina’s assertion of state sovereignty during the Nullification Crisis of 1828–33.[38] As Webster notes, the focus on territory cannot be justified by etymology. He postulates the American mixing of immigrant ethnicities as the foundation for a semantic shift from common birth to territorial and political identity, thus both evoking and eliding the explosive issues of race and national unity soon to engulf the United States:

Nation, as its etymology imports, originally denoted a family or race of men descended from a common progenitor, like tribe, but by emigration, conquest and intermixture of men of different families, this distinction is in most countries lost.[39]

French dictionaries from the same decade place markedly different emphases on territory or ethnicity as they define nation. According Boiste’s 1829 Dictionnaire universel, which had first appeared in 1800 during the Consulate,[40]nation is territorial:

NATION. [T]ous les habitants d’un même pays, d’un même état, qui vivent sous les mêmes lois, parlent la même langue.[41]

In Laveaux’s Nouveau dictionnaire de la langue française, published in 1820 during the Restoration of the Bourbon monarchy, nation is primarily ethnic:

NATION. [C]ollectif dont on fait usage pour exprimer une quantité considérable de peuple qui a une origine et une naissance commune, qui parlent le même langage, et qui ordinairement obéit au même gouvernement.[42]

The 1874–75 Littré, published somewhat later during the Third Republic, would emphasize race, which it however considered as historically constructed:

NATION. 1. Réunion d’hommes habitant un même territoire, soumis ou non à un même gouvernement, ayant depuis longtemps des intérêts assez communs pour qu’on les regarde comme appartenant à la même race.[43]

If the hesitation in French between natural and historical notions of the origins of nations present complexities dimly felt in American English, French secondary meanings of nation as “la France républicaine” given in Littré,[44] or as a body existing in opposition to the monarch,[45] have little resonance, although Béranger’s reputation as the poète national certainly depends in part on both of these meanings. Likewise, the American sense of the popular as “pleasing to people in general” from the 1828 Webster[46] is simply absent in Boiste’s, Laveaux’s, and Littré’s entries for populaire. In nineteenth-century usage, “people” and peuple mean both the population as an organic whole and the lower class, the unlettered, the vulgar. Consider this in Webster:

PEOPLE. 1. The body of persons who compose a community, town, city, or nation. …. 2. The vulgar; the mass of illiterate persons.[47]

The slippage between these meanings is echoed in French dictionaries, although they disagree on the significance of the people’s debasement. For Boiste, the subordination of the people is an injustice; his examples promote republican virtues, possibly within a constitutional monarchy:

PEUPLE. … [M]ultitude d’hommes d’un même pays, sous une même loi …; classe inférieure, peu fortunée; ouvriers, journaliers, etc. …; masse de sujets, d’hommes asservis … la partie la moins notable, la plus laborieuse, la plus vertueuse et la moins riche; (ironiq.) la plus ignorante, la plus grossière …. Un peuple vertueux n’a pas besoin de rois. L’état d’un roi constitutionnel gouvernant un peuple libre est le plus majestueux de tous les états.[48]

Laveaux, whose entry fills nearly two long columns of a large three-column page, gestures toward Republican equality but betrays fears of popular passions; in his explanations and examples he attempts to encompass all the political connotations of this contested term; his entry can only briefly be summarized here:

PEUPLE. … Multitude de familles réunies sur quelque lieu commun, et considérées sans distinction de rang ni de naissance. … PEUPLE, dans un sens politique, se dit de tout le peuple ou d’une partie du peuple relativement à l’autorité souveraine. Dans les démocraties le peuple est souverain. … Tous les pouvoirs émanent du peuple. … Dans les monarchies le peuple est composé de toutes les familles qui vivent sous l’autorité du monarque. … PEUPLE, se disait autrefois en France de l’état général de la nation, simplement opposé à celui des grands, des nobles et du clergé. … Aujourd’hui on entend par peuple la partie de la population qui … vit péniblement du travail de ses mains …. PEUPLE, se dit aussi des gens sans esprit, sans instruction, sans lumières … qui s’attachent … à celles qui flattent leurs passions.[49]

Littré would later cover some of this same territory, but with less hesitancy and equivocation, clearly allying himself with equality under the law, and seemingly without irony linking poverty, ignorance, and vulgarity:

PEUPLE. … 1. Multitude d’hommes d’un même pays et vivant sous les mêmes lois. … 9. La partie de la nation, considérée par opposition aux classes où il y a soit plus d’aisance, soit plus d’instruction. … Air peuple, air commun, vulgaire.[50]

For all these lexicographers, distinguishing nation from peuple presents difficulties. For Boiste: “Dans le sens littéral, nation remarque un rapport d’origine; peuple, un rapport d’ensemble. Dans une autre acceptation, nation comprend tous les naturels du pays; peuple, tous les habitants.”[51] Laveaux repeats nearly the same words, but with this addition: “Divers peuples rassemblés, naturalisés, unis par divers rapports communs dans le même pays, forment une nation.”[52] Nations may be based not on birth, but on naturalization; this emphasis on unity within a common history and geography echoes Webster. Yet semantic ambiguity cannot be resolved through etymology or usage, as Littré notes after making careful distinctions. Indeed, a political constitution itself cannot stabilize foundational meanings:

NATION, PEUPLE. Dans le sens étymologique, nation marque un rapport commun de naissance, d’origine, et peuple un rapport de nombre et d’ensemble. De là résulte que l’usage considère surtout nation comme représentant le corps des habitants d’un même pays, et peuple comme représentant ce même corps dans ses rapports politiques. Mais l’usage confond souvent ces deux mots; et, sous la Constitution de 1791, on avait adopté la formule : la nation, la loi, le roi.[53]

Despite its attempt to reveal clear boundaries between the national and the popular, the text published in the Southern Review manifests the confusion of these terms already present in English and even more so the French, as it exposes both its American readers and its own language to the corrosive influence of Béranger’s foreign notions.

The Southern Review, published from 1828–32 in Charleston, South Carolina, during the Nullification Crisis, represented the culture of the Southern planter elite, “the culture and learning of the South”;[54] its “general political theory” was “that of the South, State Rights [sic] and anti-consolidation.”[55] Both of its principal literary reviewers, Hugh Swinton Legaré and Robert Henry, either of whom may have written this piece,[56] were scions of the South Carolina Huguenot elite; both travelled widely in Europe; both spoke French and read a variety of modern and ancient languages. Legaré was a politician who favoured free trade and states’ rights, but opposed nullification. Henry was a pastor in a Huguenot Church who gave sermons in French and German, as well as a professor of Greek and philosophy at South Carolina College, where he lectured on free trade and constitutional rights. Both balanced elite privilege with liberal advocacy; either could plausibly have extolled Béranger as a “martyr in the cause of freedom”[57] while ignoring the unfreedom that grounded their society and shielding the more radical of his messages from the vulgar by refusing to translate them.[58] Notions of freedom, as well as notions of national belonging, differed between sections as the United States already drifted toward Civil War; soon there would arise a quest in Southern literature and politics for a “national differentiation … not from Mother England but from the North.”[59] Contemplating Béranger as a model of national unity exposes the dangerous fractures within “nation” and nation, “people” and peuple, as well as within the Union itself.

An anonymous review in New York’s Knickerbocker Magazine in 1833 discusses Béranger in the context not of national poetry but of national song, extolling the latter’s “strong and continual action on the most potent sympathies of human nature.”[60] Béranger “speaks to the people … as a common nation,” thus potentially offering a model for overcoming sectional and political conflict;[61] he has influenced the “mass of the people, in exciting the late revolutions of [France]. Yet we would not speak of his influence as confined to any party, or indebted to any sect for its consequence—its power is the force of genius.”[62] Indeed: “There is much, very much, in the character of Béranger to admire.”[63] Evoking the power of Béranger’s songs to excite the masses to violent conflict, and paradoxically praising this power as a force for national unity, the reviewer offers a number of translations of his works—but taken, he says, “at random.”[64] They do not include any songs that were condemned in France. “War Song of the Cossack” has the memorable refrain: “Let the neigh of thy pride, my faithful steed, ring; / And under thy hoof trample people and king!”—though as both people and king are trampled, the revolutionary message here is far from clear.[65] “Le Champ d’asile” is a song about a short-lived settlement in Texas of Bonapartist refugees from Restoration France,[66] and so, like the letter by Béranger to Lafayette also included, it has a North American connection, but its mournful strains would be unlikely to lead to revolt. The reviewer also includes a number of translations reprinted from English magazines:[67] “La Bonne Vieille”[68] (the title is not given here), enjoining Béranger’s aged mistress to keep up his memory after his death; “Louis the Eleventh,” which contrasts a “pale and spectral”[69] king to the songs and dances of youth; “Ma Guérison,” in which after several glasses of wine, “The tyrant’s hand I see no more— / The press is free as light of day”;[70] “My Jours Gras of 1829,” with its refrain of “You’ll pay the piper, good my king.”[71] Revolutionary impulses surface here and there as a leitmotif, but the most powerful revolutionary songs are not translated.

The first book-length collection of Béranger’s songs in English was published in London in 1837.[72] The translator was John Gervas Hutchinson Bourne, a British lawyer with a reputation for radicalism who married a Catholic, then moved to Nova Scotia where as Chief Justice his decisions warmed the hearts of conservatives.[73] He was already known as the author of The Exile of Idria,[74] a narrative poem exposing the plight of mercury miners; its plot hinges on the spectacle of an aristocrat condemned to forced labour in the mine who is ultimately freed and restored to his proper station. Bourne’s politics, in short, were mixed, and his translation of Béranger selective. As he explains in his preface, he has omitted songs “whose warmth and freedom would not suit the greater strictness of our taste … and, indeed, many … that are retained are … a good deal chastened.”[75] He thus includes only two of the indicted songs (“The White Cockade” [“La Cocarde blanche”] and “The Infinitely Little” [“Les Infiniment Petits”]), none of the virulently anti-clerical songs, and few political ones, although he occasionally exaggerates Béranger’s political and religious audacity. For instance, he transforms “J’ai pris goût à la république / Depuis que j’ai vu tant de rois” from “Ma république” into “I am quite a republican grown, / Since I’ve seen that our kings are such fools.”[76] He alters two lines in “The Infinitely Little”: “De petits jésuites bilieux! / De milliers d’autres petits prêtres / Qui portent de petits bons dieux,”[77] scandalous enough with its image of thousands of little priests carrying little consecrated hosts, becomes in his rewriting a rollicking couplet about illicit sex in the convent: “There were little bilious Jesuits, / And little monks, and little nuns, / With their little daughters and little sons.”[78] He also translates a few songs of less than British strictness, while muting their impact by eliminating their playful double entendres, as in “La Mère aveugle,” about a young girl who pretends to her blind mother that she is spinning while in fact preparing to go to bed with her lover. Her mother warns: “So, spin away; and Lizzy, hist, / Get not your thread or fame a-twist! / You’d better mind your wheel.”[79] The translation thus avoids the original’s mention of tangled linen and the command not to spin with another spindle: “Filez, filez, filez, Lise, … / En vain votre lin s’embrouille; / Avec une autre quenouille, / Non, vous ne filerez pas.”[80]

The first book-length collection of translations from Béranger to appear in the United States was published by Carey and Hart in 1844. The prefatory “Life of Béranger” is signed R.W.G., that is, Rufus Wilmot Griswold, best known, perhaps, as an associate of Edgar Allan Poe, but also “an editor and compiler of books”;[81] his collection The Poetry and Poets of America was famously savaged along with the poetic abilities of the compiler in a review attributed to Poe.[82] According to Griswold: “The larger number [of these translations] have appeared in various British periodicals, a few are from American magazines, and the remainder are original.”[83] Of the 55 songs included, 20 list their translators in the table of contents, but that does not mean that the rest were translated by Griswold. At least some of the unattributed translations were in fact reprinted from periodicals. For instance, “Le roi d’Yvetot” had appeared in the British Metropolitan Magazine in 1835, signed J. Waring.[84] “The Secret Courtship” (“La Mère aveugle”) had appeared anonymously in the New York Morning Herald of July 26, 1837,[85] which may be where Griswold saw it; it was included later in the collected poetry of Thomas Smibert, an Edinburgh journalist, where it is called “The Blind Mother.”[86] Some of the songs were borrowed from Bourne: “Adieu to the Country,” “No More Politics,” “Romance,” “Remembrances of Infancy.” Since translations of Béranger’s songs were freely reprinted, often without crediting the translator, Griswold might have been unaware of their original source.[87]

By far the most frequently cited contributor to the volume is William Maginn, with eleven attributed translations. Six of these appeared in a series of articles in Fraser’s entitled: “The Songs of France: On Wine, War, Woemen, Wooden Shoes, Filosophy, Frogs, and Free Trade, from the Prout Papers [sic].”[88] Maginn might have had something to do with them: Latané mentions an unpublished letter by Maginn exploring the possibility of publishing a volume of translations from Béranger.[89] However, since “[m]uch of Maginn’s work lies deeply buried in the folds of collaborative authorship, and his portions cannot be positively identified,”[90] any attribution remains tentative: “Father Prout” was in fact a pseudonym for Francis Mahony.[91] “The Songs of France” is lighthearted and flippant, associating Béranger with free trade, which is disparaged, but praising his cleverness and wit. The songs are printed in French with English translation, and the translation is loose, often altering or disguising the political meaning. For instance “The Song of the Cossack,” which in French reads: “Hennis d’orgueil, ô mon coursier fidèle, / Et foule aux pieds les peuples et les rois,” bleakly presenting the subjugation of the governments and populations of many kingdoms, is rendered in English as: “Then fiercely neigh, my charger grey—O! thy chest is proud and ample; / And thy hoofs shall prance o’er the fields of France, and the pride of her heroes trample!”[92] The translation of these lines in the Knickerbocker quoted above changes the plural peuples et rois to the singular “people and king,” thus subtly altering their meaning, either limiting the destruction to one kingdom or raising it to the universal; the translation in Fraser’s takes this even further, in its prancing rhythm presenting a celebrating of the destruction of France. One of the remaining songs attributed to Maginn appeared originally in The Athenaeum,[93] where it was signed W.D. The remaining four are from Tait’s; they betray a liberalism unlikely to have been espoused by the avowed Tory Maginn. Three of these had already been reprinted in the Knickerbocker article,[94] where Griswold may have seen them. The remaining song, which Griswold entitles “The Holy Alliance,” was originally printed in Tait’s in 1839 as “La Sainte Alliance du Peuple,”[95] then reprinted in the New Yorker later that year under the same title.[96] The original title, however, was “La Sainte Alliance des peuples,”[97] a play on the Holy Alliance, the coalition of kingdoms formed on the defeat of Napoleonic France to ensure the final suppression of any revolutionary impulse.[98] The song calls on the peoples of the world to join hands against “rois ingrats … vastes conquérants.”[99] By changing “des peuples” to “du peuple,”[100]Tait’s alters the alliance of whole populations to the alliance of a particular class, certainly obliquely present in Béranger’s text but not its overall thrust; by truncating the title, Griswold ambiguously identifies the peoples’ (or people’s) alliance with their (its) opponent.

Of the remaining songs, three are attributed to W. Falconer, three to J. Lawrence Jr., two to J. Price, and one to Bowring. The attribution of “My Jours Gras of 1829” to Bowring repeats that of the Knickerbocker article. John Bowring was a liberal advocate of free trade caught up in anti-monarchist conspiracies of the 1820s and a prolific poet and translator,[101] so the attribution may be correct, but I have found no other publication of the piece.

Two of the three translations by Falconer had appeared in the New Yorker. Falconer had been recommended by New Yorker editor Horace Greeley to Griswold: “My friend W. Falconer is coming out from Paris. … If he can produce a real good translation of the decent songs of Beranger, don’t you think one of the Philadelphia Houses [sic] could be induced to publish them on fair terms?”[102] One of these translations was “The Suicide,” retitled by Griswold “The Suicides,” about Victor Escousse and Auguste Lebras, two young poets who committed suicide together: “And like two friends they parted, hand in hand, / To force a passage to the Spirit-Land.”[103] The New Yorker gives a translation of the long note appended to the original by Béranger but omitted by Griswold, which extols the heroic patriotism of Escousse.[104] “The Grave of Manuel” is Béranger’s lament for his “most intimate friend,” as the introduction to the song in the New Yorker puts it, whose political career was ruined “on account of a speech which contained an allusion very nearly resembling the famous apostrophe of Patrick Henry.”[105] Manuel was expelled from the Chamber for a speech alleged to condone regicide;[106] the apostrophe by Patrick Henry was first recounted by his early biographer William Wirt: “Caesar had his Brutus—Charles the first, his Cromwell—and George the third… If this be treason, make the most of it.”[107] The third translation—which may be original, as I can find no earlier publication—is “The Old Banner,” one of Béranger’s indicted songs, in which a Napoleonic veteran pulls out the forbidden tricolour flag he has hidden under his bed and wonders, “Quand secoûrai-je la poussière / Qui ternit ses nobles couleurs?;[108] Falconer renders this: “Ah! When from its colors of pride shall I shake / The tarnishing dust, and bid heroes awake!”[109] Falconer’s version of Béranger seems to be constructing a national poetry based on male-male friendship, ardent republicanism, reverence for the dead, and heroic defiance of authority, of which only fragments are preserved here.

The two translations by Joseph Price also originally appeared in the New Yorker.[110] “My Coat” was printed immediately following Falconer’s “The Grave of Manuel”; it had been “executed at short notice” because Falconer’s translation of the song had been lost.[111] Falconer’s “spirited translation”[112] was published in the New Yorker a few years later; the version by Price “had been a fair one,” but inferior.[113] Greeley had praised “My Old Coat” when he recommended Falconer to Griswold;[114] he later complained that Griswold had used Price’s version: “‘My Old Coat’ … by Falconer is better than that you give”[115] and bemoans the loss of Falconer’s “My Vocation” and “The Cossack.” “Your choice of translations is often dreadful,” writes Greeley: “‘The Garret’ kills me. Jo Price’s version— ‘espying the world with its sages and asses, / In a Garret at twenty how cheerly time passes!’ is worth a million that you have given”[116]—thus better than Maginn’s.

The songs translated by Jonathan Lawrence, Jr., all appeared in a slim volume of poetry published after Lawrence’s early death.[117] The first, “Old Age,” is indeed by Béranger.[118] The other two, “The Cry of France” and “The Veterans,” most likely are not. Both appear in a number of clandestine supplements to Béranger’s works, often in a section entitled “Chansons attribués à P.-J. de Béranger,”[119] but they are not in the semi-official supplement to the 1834 edition of the Oeuvres complètes.[120] The first translation had appeared in Niles’ Weekly Register in 1830 (and possibly elsewhere) under the title “Away with the Bourbons,” the second in The Knickerbocker in 1833.[121] Stirring as these translations and their originals are, they do not belong here.

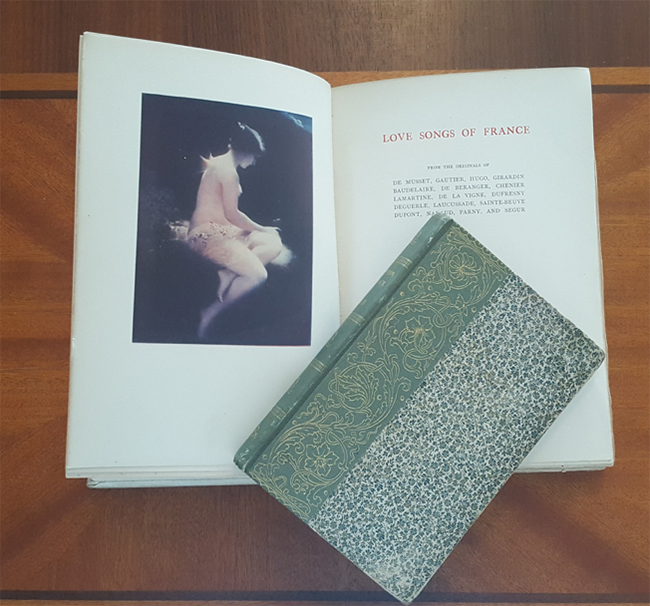

The rest of the songs in the anthology are indeed based on songs in standard collections of the works of Béranger, but they often bear little resemblance to the original. As Park Benjamin noted in the Columbian Lady’s and Gentleman’s Magazine: “There has been a collection of translations, so-called, published recently in Philadelphia. … But the pieces in the pretty, parchment-covered Philadelphia volume (Fig. 1) should, for the most part, be entitled ‘Lines suggested by such and such a song of de Béranger.’”[122]

Figure 1

From left to right: Griswold’s “pretty parchment-covered Philadelphia volume” (1844), Young’s un-illustrated cloth and large-paper morocco issues (1850), and Sauveur’s textbook (1889) and its limited-edition translation (1894).

Benjamin notes a misleading cultural transformation in Maginn’s “The Garret,” which has “The Jew can tell / How oft I pawned my watch to serve a friend”[123] for the original’s “Vingt fois pour vous j’ai mis ma montre en gage.”[124] As he points out: “There are no Jews in France who are pawnbrokers. Everybody knows that this business … is monopolized by the government.”[125] Nonetheless, anti-Semitism is inserted into Béranger’s verse in Benjamin’s text. According to the translation of “Ainsi soit-il” offered as superior to those in Griswold’s anthology, in Béranger’s ideal world, “[n]o Jews or gamblers will we brook”[126]; the original merely has: “Plus d’usuriers, plus de jouers.”[127] Usurers, for the translator, are Jews: the anti-Semitism is his.

In 1847, there appeared in London a little volume entitled One Hundred Songs of Pierre-Jean de Béranger, with Translations by William Young,[128] its somber green cloth enlivened by an ornate gilt stamp and an accent aigu that promised a delightful foreign experience—at least, according to the dedication page, for those able to overcome national prejudice: “To Englishmen, who note the characteristics of other countries, moral, social, and political, but do not judge them by the standard of their own, is dedicated this attempt to make better known amongst us the greatest lyric poet of the age.”[129] Young presents Béranger in French for initiates, and translated into carefully worded English for the less well educated. He includes a fair selection of political works, but only two of the indicted songs (“The White Cockade” and “The Old Flag”). He shies away from many of Béranger’s most scurrilous satires, nearly the entire range of his sexually celebratory lyrics, and the most radical of his political and religious songs.

Young moved to New York and in 1848 bought the Albion, a newspaper aimed at English expatriates,[130] where he published a number of new Béranger translations.[131] In 1850 he brought out an expanded version of his collection, now called not songs but lyrical poems.[132] Putnam advertised three bindings for Young’s Two Hundred of Béranger’s Lyrics: antique morocco, $7, gilt cloth, $5, and cloth, $4.50 (Fig. 1);[133] an advertisement in the Albion published earlier that year also lists a smaller edition without engravings for $1.50.[134] The larger volumes have steel engravings identical to those in the Paris edition of 1847,[135] perhaps purchased from Perrotin, Béranger’s French publisher, or printed from the same plates. This expanded edition is enhanced by a letter to Young from Béranger in French,[136] the only French in the volume, since only translated versions of Béranger’s songs are included. In a new preface, Young “disavows … any sympathy whatever with [Béranger’s] political doctrines” since he is “strongly and steadily attached to the monarchical institutions of his native land.” Such a “declaration,” unnecessary in England, is required “when aspiring to lay before the Citizens of a Republic a work that breathes the very essence of Republicanism.”[137] Young includes many more songs attacking the monarchy, the nobility, and the clergy, and four more of Béranger’s indicted songs (“Le Bon Dieu,”[138] retitled “Jupiter,” “The Prince of Navarre,” “The Infinitely Little,” “The Coronation of Charles the Simple”). He also includes songs like “Anglomania, or the Boxers,” a spirited mockery of British brutality, and he more than doubles the number of sexually suggestive songs, including “La Vertu de Lisette,”[139] slightly disguised by rendering the title as “Lisette’s Good Fame,” and “Les Révérends Pères,” the satirical attack mentioned above on the Jesuits’ alleged delight in flogging “your sweet little boys.”[140] Neither of these songs appears in any other English-language edition.

Young also includes a song that appears in no other collection of Béranger’s works, in either French or English, which he entitles “Ode on the Revolution of 1848.” The song is addressed to Béranger’s intimate friend, the liberal politician Manuel, who had died in 1827, and in whose grave Béranger would eventually be buried. In the song, the poet wishes he could have shared with Manuel the spectacle of the people’s uprising. The song had appeared in several working-class and revolutionary newspapers and as a pamphlet in 1848, although it was not called an ode. Its wooden versification and its odd refrain (“Ah, my poor friend, for thy embrace I sigh”)[141] do not seem typical of Béranger, who in fact denied having written it.[142] Nonetheless, Young observes that “Manuel … appears to have been his beau ideal of a politician and a man.”[143] It is not clear where Young obtained the song, or why he included it.[144]

Young’s politics are also not clear, despite his preface. His collection’s broad-minded inclusiveness may have been facilitated by his move to the United States, but his disavowal of “Republicanism” may have been intended to placate the British readers of the Albion or those of the London edition he self-published the same year.[145] Young’s politics seem decidedly more radical than he admits, despite the sometimes muted vocabulary of his translations. He includes in the expanded edition “La Sainte Alliance des peuples,” but he retitles it “The Holy Alliance of Nations.” By translating “peuples” as “nations,” Young transforms Béranger’s call for international popular solidarity against the warmongering political elites into a call for institutionalized cooperation among clearly defined nation-states. Béranger’s “Près de la borne où chaque état commence, / Aucun épi n’est pur de sang humain,”[146] which resonates with the origins of States, becomes Young’s “Along the boundary line of States, be sure, / No blade of corn from human blood is pure,”[147] which alludes instead to the objective separations among them, thus altering Béranger’s emphasis on the historical contingency of division. Where Béranger has, “Pour l’étranger coulez, bons vins de France: / De sa frontière il reprend le chemin,”[148] Young omits “pour” and translates “étranger” not just “stranger” or “foreigner,” but the more absolute “Alien”: “Good wines of France, flow, freely flow to-day— / Back to his land the Alien takes his way.”[149] In Young’s translation, it is as if the wines of France were not flowing for the stranger as he prepares to return, but rather flowing because the alien is departing, thus excluding him from the very bonds the song is meant to invoke.

Young had originally published the song in the Albion on June 17, 1848, just before the Second Republic’s promise of workers’ solidarity collapsed in the reaction that eventually led to the Second Empire.[150] His introduction to the song, both in its original newspaper appearance and in the printed volume, notes its “spirit of fraternity,” but he claims such fraternal sentiments are “much at variance, probably, with the real feelings of the French” because of their “amour propre and national vanity”; “[t]he union of Nations in one bond of brotherhood,” he concludes, is a “chimerical … project” despite the song’s “noble and generous sentiments.”[151] Suspicion and reinforced borders between classes and nations work together to undermine the subversive thrust of Béranger’s visionary appeal.

Young’s translation was much applauded when it appeared. “The only volume to give an adequate specimen of [Béranger’s] works in English,” said Littell’s Living Age.[152] “Mr. Young has studied these immortal chansons with a genial love and diligence; … to the most delicate appreciation of the niceties of the French language … he has added an unusual mastery of forcible and poetical English rhetoric,” said the International Miscellany.[153] He is better than “the author of The Exile of Idria [Bourne]” and of “the Philadelphia translator [Griswold],” as he catches the “true spirit” of Béranger’s “simple ode[s],” according to Sharpe’s London Journal.[154] The International Weekly Miscellany considered him even better than Maginn:[155] “The learned and brilliant ‘Father Prout’ has been … the most successful [of Béranger’s translators]; but his versions are not to be compared with Mr. Young’s for adherence either to the bard’s own meaning or music.”[156] Young’s translation of Béranger became standard: it went through six editions through 1878,[157] and was the source for several songs in a recent anthology.[158]

A new translation rivaled Young’s as the century drew to a close, that of Craven Langstroth Betts,[159] a poet from New Brunswick who spent most of his life in the United States. His translation of Béranger was his first book. His greatest success came with The Perfume-Holder, published in 1891, but he was nearly forgotten by his death in 1941: “He had rejected the age, retreating from modernism into the ancient East and the past masters … and the age, not surprisingly, rejected him.”[160] He selected for translation primarily Béranger’s political songs, which might account for his volume’s obscurity, as the Béranger that still survived, if fitfully, was the erotic Béranger who had been mostly banned from previous English-language editions. Betts’s book appeared in a dainty aesthetic binding, gold-blocked floral green cloth spine, cream cloth sides printed with tiny leaves and flowers, in frank disharmony with the more manly content within (Fig. 2).

Figure 2

From left to right: Harry Curwen’s anonymous anthology (1896) and Craven Langstrom Betts’s fin-de-siècle translation (1888).

Indeed, as Béranger’s impact slowly faded, his hard edge was blunted to soft-core appeal. His songs increasingly appeared in delicately suggestive anthologies, such the 1871 New York reprint of Curwen’s Echoes from the French Poets,[161] originally published in London in 1870, retitled for its North American public French Love Songs and other Poems and presented with lavender endpapers, uniform with an edition of Swinburne, then retitled Love Songs of France and reprinted anonymously in 1896 with an erotic chromolithograph (Fig. 2).[162] The collection included, along with a selection of Béranger’s more anodyne love lyrics, the patriotic “Old Flag,” rather out of place in this company.[163]

Perhaps the most politically significant treatment of Béranger’s songs published in the United States appeared in 1889 in a textbook by the French expatriate Lambert Sauveur,[164] a pioneer of the direct method of language instruction in which students acquire foreign language competency through conversation without translating.[165] His textbook reproduces some 50 of Béranger’s songs with introduction and notes exclusively in French to be used as a foundation for unstructured conversation between student and teacher. In these provocative texts, Sauveur immerses the anglophone reader in French cultural sensibility. A large portion of the book is devoted to Béranger’s political songs, with notes written from an unabashedly French perspective. Lambert invites his American students to let France enlighten them and guide them to a better future: “Ô France! éclaire le monde et ouvre-lui le chemin d’un meilleur avenir. Cette dernière pensée est-elle d’un sentiment trop français? Les autres nations le trouveront peut-être.”[166] He immerses them in French history from a decidedly French Republican point of view, promoting the Revolutionary principles of equality and fraternity. Explaining an allusion to the Bourbon restoration in “Les Esclaves gaulois,” he informs them: “C’est quand les Bourbons revinrent, après l’abdication de Napoléon. Ce jour-là moururent les lois d’égalité et de fraternité, établies par la Révolution.”[167] Indeed, his students’ exposure to French political vocabulary threatens to shift their understanding of the cognate American terms, as in Sauveur’s introduction to “La Sainte Alliance des peuples”: “[La chanson] était fort hardie en effet et tout à fait révolutionnaire: elle appelle les nations à former entre elles la Sainte Alliance des peuples contre la Sainte Alliance des rois.”[168] Here, nation is vaguely contaminated by the nearby peuple, thus causing it perhaps to drift toward the French sense of the nation in opposition to the State. And révolutionnaire might lead toward the particularly French idea, later taken up by Marxists, of the revolution not as an event in the past but as a process that could retreat or recur but is yet to be accomplished, an idea Lambert takes up again in his discussion of Napoleon: “[Napoléon] était la révolution, chose qui ne peut faire naufrage ni périr.”[169] Perhaps more radically, Lambert associates the revolution with Christ’s fraternal vision: “Sa révolution [du Christ] … est cet idéal chrétien … d’une vie fraternelle et heureuse.”[170] Christ, revolution, and France are explicitly associated with socialism in Sauveur’s introduction to “Les Quatre Âges historiques”:

Cette science nouvelle … faite d’amour et de générosité … est appelée à réformer la société, à établir sur la terre l’égalité entre tous les hommes, à leur donner à tous une bonne part dans les bienfaits de la vie … à mettre un terme aux guerres qui divisent les nations …. C’est afin de nous conduire dans ce monde idéal que le Christ est venu parmi nous il y a près de dix-neuf siècles.[171]

Enfin voici notre âge … celui de l’humanité, celui de la Révolution française, qui a proclamé les droits de l’homme …. Ce ne sont plus les rois qui régnent, ce n’est plus le pape qui gouverne le monde, le peuple est souverain.[172]

Sauveur presents an even more radical defense of social revolution in a remark he attributes to “un pasteur américain,” who calls the Communards sublime: “Ce sont des hommes sublimes, qui vont mourir pour une idée, qui ne songent pas un instant à eux-mêmes, qui sont tout entiers à la cause de leur drapeau.”[173] Perhaps Sauveur is only attempting to provoke his students by exposing them to the extreme left of French political opinion, but one wonders to what extent they could remain uncorrupted by their immersion in his alien text.

In 1894, a translation of Sauveur’s work was published in a limited edition with a cheaply produced but sumptuous binding, royal blue with delicate pink and gold floral endpapers, quite unlike the utilitarian dark blue book cloth of the original textbook (Fig. 1).[174] The cover mentions neither Sauveur nor Béranger: its ornate gilt lettering reads only Songs of France, and on the spine, Translated, thus promising the reader exotic contact with the foreign, but domesticated. Experiencing Sauveur’s text in translation dulls its effect. A number of the translations are “taken … from an old book … published by Carey & Hart, of Philadelphia, in 1844,”[175] with all of the imprecisions, confused politics, and incorrect attributions of that motley compilation. “La Sainte Alliance des peuples” is here called “The Holy Alliance of Nations,” following William Young, but with the text attributed to Maginn and taken from Griswold’s collection, where, as we have seen, it had merely been called “The Holy Alliance.” The translation is garbled, even incomprehensible. The lines about the bloody wheat at the frontier are translated here, as in Griswold following Tait’s via the New Yorker: “Near the bourne whence all states have gone forward, we find / No corn-blade sustained by the blood of mankind.”[176] One wonders why the editor included this evidently inadequate rendering. In the newly translated commentary, a few of Sauveur’s more extreme pronouncements are excised, such as the reference to Christ’s revolution, which is replaced by something entirely less remarkable: “Sa révolution [du Christ] … est cet idéal chrétien … d’une vie fraternelle et heureuse”[177] becomes, “[T]he new dispensation … is this ideal religion … of a fraternal and happy life.”[178] The sometimes rather tenuous connection between Béranger’s text and Sauveur’s commentary becomes more evident as the editor struggles to place Sauveur’s notes in a text reordered by translation. Sauveur’s “Voilà le Christ: rendre le bien pour le mal, ne pas se souvenir des injures et fêter même ceux qui nous ont fait pleurer”[179] is rather literally rendered as, “Behold the Christ: to return good for evil, to forget injuries, and to be kind even to those who have made us weep”;[180] however, the editor has placed this a few lines down from Sauveur’s description of hospitality toward one’s enemies, after: “Grant him here some festive moments, / Love and Friendship more than all.”[181] This is well enough, except that “Love and Friendship” translates Béranger’s “des amours,”[182] perhaps better rendered as “love affairs,” which might seem inappropriate for the glossing of Christ’s love for one’s enemies. Denied direct exposure to French, and misled by a thicket of insufficiencies, the reader fails to experience the full corrosive impact of Sauveur’s book. Perhaps Sauveur was right: without full immersion, the foreign cannot be assimilated.

Béranger’s texts continued to appear in the United States into the twentieth century, if only occasionally: two stanzas of “La Sainte Alliance” appeared in the November 2, 1918, issue of the long-running weekly The Nation in the midst of its shift to the left.[183] World War I was not yet over; the Russian Revolution was raging. For The Nation, “The Russian Revolution [was] the most inspiring event since the French Revolution”;[184] the revolution was an ongoing historic process, which could be betrayed: “[E]very one of [the Bolsheviks’] outrages injures the revolution and the whole cause of liberty.”[185] A new international organization was needed: “[T]he time is … ripe for a league of nations to enforce peace.”[186] Swayed perhaps by the tenor of the times, the editor chose to entitle the fragment “The Holy Alliance of the Nations,” but the translator, in a measured and dignified cadence, in plain and simple language, follows Béranger in calling for a holy alliance of peoples, against war, against power, against fear: “Divide more justly this too narrow ball, / And each shall have his own place in the sun. / …Holy alliance form, and unafraid, / Ye peoples, now clasp hands!”[187]

Béranger’s songs of France may not in the end have provided a model for an American national poetry. As the United States retrenched behind a national poetic tradition of nostalgia, sentiment, and moral uplift, recited at official occasions and memorized in the public schools,[188] Béranger’s “light and graceful movements of gaiety and wit”[189] washed up on the shores of erotic titillation, and the banner of unfinished revolution passed on, to a new poetry of “modern speech, simplicity of form, and authentic vitality of theme”[190] often steeped in social opposition,[191] and to the Soviet Union, where Béranger’s translated songs remained in print well into the twentieth century.[192] Yet we would do well to remember how for a time his “noble and generous sentiments”[193] spoke across national and linguistic boundaries, “living on”[194] in these translated and untranslated voices, surreptitiously crossing borders and scrambling hierarchies, forging new alliances as they threatened to undermine domestic certainty and incite alternative meanings.

Appendices

Biographical note

Robert O. Steele is a cataloguing librarian at Jacob Burns Law Library at George Washington University. His research interests include nationalism in France and Quebec, queer studies, law and literature, and book history.

Notes

-

[1]

The fullest treatment of the life and works of Béranger remains Jean Touchard, La Gloire de Béranger, 2 vols. (Paris: Librairie Armand Colin, 1968), which has recently been supplemented by Sophie-Anne Leterrier, Béranger: des chansons pour un peuple citoyen (Rennes: Presses universitaires de Rennes, 2013).

-

[2]

The most complete bibliography of Béranger’s works in French is Jules Brivois, Bibliographie de l’oeuvre de P.-J. de Béranger (Paris: L. Conquet, 1876), although it does not include all clandestine publications and is obviously limited by its date of publication.

-

[3]

Georges J. Joyaux, “The Reception of Pierre-Jean de Béranger in America: 1818–1848,” French Review 26, no. 4 (February 1953): 269, https://www.jstor.org/stable/382547.

-

[4]

Advertisement for George P. Putnam, Norton’s Literary Gazette and Publishers’ Circular 2, no. 6 (June 15, 1852): 124.

-

[5]

Advertisement for Roe Lockwood & Son, Norton’s Literary Gazette and Publishers’ Circular 2, no. 1 (January 15, 1852): 17. The copy of the 1850 French edition of Béranger’s works held by the University of Virginia is stamped on each title page, under the French imprint: New-York, Roe Lockwood & Son, American and Foreign Books, 411 Broadway. This edition is Pierre-Jean de Béranger, Oeuvres complètes de P.J. de Béranger, contenant les dix chansons nouvelles, 2 vols. (Paris: Perrotin, 1850).

-

[6]

Pierre-Jean de Béranger, Dernières chansons de P.J. de Béranger de 1834 à 1851, avec une lettre et une préface de l’auteur (San Francisco: Henry Payot, 1858).

-

[7]

At least by the 1845 Tales: “Son coeur est un luth suspendu; / Sitôt qu’on le touche il rèsonne [sic]” (“His heart is a suspended lute; / As soon as it is touched, it sounds.”). See Edgar Allan Poe, Tales (New York: Wiley and Putnam, 1845), 64. The quotation is from “Le Refus,” which, however, has “mon” rather than “son.” See Pierre-Jean de Béranger, Oeuvres complètes de P.J. de Béranger, 4 vols. (Paris: Perrotin, 1834), 4:17. Future references to this edition will be in the form Béranger, Oeuvres complètes (1834). Unless otherwise specified, all translations in the notes are mine, but see note 18 below.

-

[8]

Walt Whitman, “The Moral Effect of the Atlantic Cable,” Brooklyn Daily Times, August 20, 1858, in Walt Whitman’s Selected Journalism, ed. Douglas A. Noverr and Jason Stacy (Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2015), 105, https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt20p585k.45.

-

[9]

“Anecdotes Concerning Well-Known People: The Making of a Journalist,” Sunday Star (Washington, D.C.), November 17, 1907, 4:2, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov. The same filler appeared on the same date in the Dallas Morning News. See Barbara Schmidt, “Virginia City Territorial Enterprise, 1862–1868,” Mark Twain Quotations, Newspaper Collections, & Related Resources, http://www.twainquotes.com/teindex.html. The story was more recently repeated in John M. Glionna, “Nevada Newspaper where Mark Twain Made His Name is Back in Business,” Los Angeles Times, April 5, 2015, https://www.latimes.com/nation/la-na-mark-twain-newspaper-20150405-story.html.

-

[10]

See Pierre-Jean de Béranger, Ma biographie (Paris: Perrotin, 1860), 20.

-

[11]

See Meredith L. McGill, American Literature and the Culture of Reprinting, 1834–1853 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2003), especially pp. 45–108.

-

[12]

Lawrence Venuti, Translation Changes Everything: Theory and Practice (London and New York: Routledge, 2013), 77.

-

[13]

Ibid., 10.

-

[14]

Ibid., 11.

-

[15]

“His texts are … read as full-fledged poems by the bourgeois, and sung by the people.” Sophie-Anne Leterrier, “Béranger, poète ou chansonnier? Les Jugements de l’histoire littéraire,” Revue d’histoire littéraire de la France, 114, no. 1 (2014): 114, https://www.jstor.org/stable/42796852.

-

[16]

An exception is Pierre-Jean de Béranger, Songs from Béranger, trans. in the original metres by Craven Langstroth Betts (New York: Frederick A. Stokes & Brother, 1888). Although he does not follow the original metres, Bourne gives English airs for nearly a third of his volume of translations; the practice is atypical. See Pierre-Jean de Béranger, Songs of Béranger, translated by the author of the “Exile of Idria” etc., with a sketch of the life of Béranger up to the present time, [trans. John Gervas Hutchinson Bourne] (London: William Pickering, 1837).

-

[17]

See Michael C. Cohen, The Social Lives of Poems in Nineteenth-Century America (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015), which centres its discussion on New England poets, and, for another perspective on the circulation of poetry and songs through versions and media, Coleman Hutchison, Apples and Ashes: Literature, Nationalism, and the Confederate States of America (Athens, GA and London: University of Georgia Press, 2012) chapters 3 and 4 (pp. 99–172).

-

[18]

A more literal translation of the French might be: “As he had managed to be pleasing to the daughters of good families, his subjects had a hundred reasons to call him their father,” with the caveat that even this version, since it inverts phrases and makes choices among possible renderings, is itself yet another interpretation; indeed, the first line might also be rendered: “Skillful at pleasing loose women at high-class establishments.” Thoroughly unpacking Béranger’s scandalous nuances is outside the scope of this paper. William Makepeace Thackeray, The Paris Sketch Book, by Mr. M. A. Titmarsh, 2 vols. (London: John Macrone, 1840), 2:210, 213, 216.

-

[19]

Thackeray, Sketch Book, 2:209.

-

[20]

Joseph Phelan, “The British Reception of Pierre-Jean de Béranger,” Revue de littérature comparée, no. 313 (2005): 8, https://www.cairn.info/revue-de-litterature-comparee-2005-1-page-5.htm.

-

[21]

Unsigned review of Méditations poétiques, by Alphonse de la Martine [sic], Trois Messeniennes, by Casimir de la Vigne [sic], and Chansons &c., by J. B. [sic] de Béranger, Edinburgh Review 37, no. 74 (November 1822): 408, 410. Phelan’s reading of this article as contrasting “an enduring strain of libertinism, skepticism and volatility in the French … with the British inclination toward morality, piety and social order” might be nuanced by the article’s slippage from Nature to Gothic excess in British character: “[W]e deal fearlessly with the primitive and universal passions of our kind, and they almost exclusively with the pretensions and prejudices of persons of rank and condition” (408). See Phelan, “British Reception,” 7.

-

[22]

Unsigned review, Edinburgh Review, 420, emphasis in original.

-

[23]

Ibid., 432.

-

[24]

Ibid., 429.

-

[25]

“The Reverend Fathers,” “who spank, and spank again, the pretty little, the pretty boys.” Ibid., 430.

-

[26]

“Request presented by the dogs of quality.” Ibid., 430–31.

-

[27]

“The God of Good People.” “Me, to defy exigent masters with glass in hand, gaily I entrust myself to the God of good people.” Ibid., 431.

-

[28]

The classic account of the triumphal progress toward an American national literature is Benjamin T. Spencer, The Quest for Nationality: An American Literary Campaign (Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 1957), but compare McGill’s account of an antebellum economic nationalism based on free trade which eschewed a distinct national literature in the name of a vigorous publishing industry, “regional in articulation and transnational in scope.” McGill, American Literature and the Culture of Reprinting, 1.

-

[29]

Unsigned review of Chansons de P.J. de Béranger and Chansons inédites de P.J.de Béranger, Southern Review, no. 13 (May 1831): 47.

-

[30]

Ibid., 49.

-

[31]

Ibid., 42.

-

[32]

Ibid., 43.

-

[33]

Ibid.

-

[34]

Ibid., 51.

-

[35]

Ibid., 53–4.

-

[36]

“The White Cockade,” “The Old Flag.” I take my list of the indicted songs from the charge to the jury in the first trial, and verdict in the second, printed in Béranger, Oeuvres complètes (1834) 4:257–59, 391–92: “La Bacchante,” “Ma Grand’mère,” “Margot,” “Deo gratias d’un épicurien,” “Le Descente aux enfers,” “Mon curé,” “Les Capucins,” “Les Chantres de paroisse,” “Les Missionnaires,” “Le Bon Dieu,” “La Mort du roi Christophe,” “Le prince de Navarre,” “L’Enrhumé,” “La Cocarde blanche,” “Le Vieux drapeau,” “L’Ange gardien,” “Les Infiniment Petits,” and “Le Sacre de Charles le Simple.”

-

[37]

Noah Webster, An American Dictionary of the English Language, 2 vols. (New York: S. Converse, 1828), 2:[167].

-

[38]

See: Freehling, William W., Prelude to Civil War: The Nullification Controversy in South Carolina, 1816–1836 (New York and London: Harper & Row, 1966).

-

[39]

Webster, American Dictionary, 2:[161], emphasis in original.

-

[40]

Stéphanie Petzold, “Pierre-Claude-Victoire Boiste.” Musée virtuel des dictionnaires. https://dictionnaires.u-cergy.fr/auteurs/boiste.html.

-

[41]

“NATION. All the inhabitants of the same country, of the same state, who live under the same laws, speak the same language.” Pierre-Claude-Victoire Boiste, Dictionnaire universel de la langue française, 7th ed. (Paris: Verdière, 1829), 462.

-

[42]

“NATION. Collective noun used to express a considerable quantity of people who have a common origin and birth, who speak the same language, and who ordinarily obey the same government.” J[ean]-Ch[arles] Laveaux, Nouveau dictionnaire de la langue française, 2 vols. (Paris: Deterville, Lefèvre, 1820), 2:212.

-

[43]

“Gathering of men [sic] living in the same territory, under the same government or not, having had for a long time sufficiently common interests that they are considered the same race.” Émile Littré, Dictionnaire de la langue française, 4 vols. (Paris: Librairie Hachette & cie, 1873–74), 3:691.

-

[44]

“La grande nation, nom donné d’abord à la France républicaine” (“The great nation, name first given to republican France”). Littré, Dictionnaire, 3:692.

-

[45]

See, for instance, David A. Bell, The Cult of the Nation in France: Inventing Nationalism, 1680-1800 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001), 57–60.

-

[46]

Webster, American Dictionary, 2:[305].

-

[47]

Webster, American Dictionary, 2:[257]. But note under “popular”: “Popular, at least in the United States, is not synonymous with vulgar; the latter being applied to the lower classes of people, the illiterate and low bred; the former is applied to all classes, or to the body of the people, including a great portion at least of well educated citizens.” Webster, American Dictionary, 2:[305], emphasis in original.

-

[48]

“PEOPLE. Multitude of men [sic] of the same country, under the same law. Inferior, less fortunate class; mass of subjects, of subjugated men [sic]; the least notable, the most laborious, the most virtuous, and the least rich part; (ironic) the most ignorant, the most coarse. A virtuous people does not need kings. The estate of a constitutional king governing a free people is the most majestic of all estates.” Boiste, Dictionnaire, 515, emphasis in original.

-

[49]

“PEOPLE. Multitude of families gathered together in one common place, and considered without distinction of rank or birth. PEOPLE, in a political sense, is said of the whole people or a part of the people relative to the sovereign authority. In democracies the people is sovereign. All powers emanate from the people. In monarchies the people is composed of all families who live under the authority of the monarch. PEOPLE, formerly in France referred to the general estate of the nation, simply opposed to that of the great, the nobles and the clergy. Today one means by people the part of the population who live with difficulty by the work of their hands. PEOPLE is also said of individuals without intelligence, without instruction, without enlightenment who attach themselves to those who flatter their passions.” Laveaux, Dictionnaire, 2:386, emphasis in original.

-

[50]

“1. Multitude of men [sic] from the same country living under the same laws. 9. The part of the nation considered in opposition to the classes where there is more ease, more education. [Used as an adjective with ‘appearance’], a common, vulgar appearance.” Littré, Dictionnaire, 3:1091.

-

[51]

“In the literal sense, nation notes a relationship of origin; people, a relationship of the whole. In another acceptation, nation includes all the natives of the country; people, all the inhabitants.” Boiste, Dictionnaire, 16, emphasis in original.

-

[52]

“Diverse peoples, brought together, naturalized, united by common relationships in the same country, form a nation.” Laveaux, Dictionnaire, 2:213, emphasis in original.

-

[53]

“In the etymological sense, ‘nation’ denotes a relationship of common birth or origin, ‘people’ a relationship of number and of the whole. Thus, usage especially considers ‘nation’ as representing the whole of the inhabitants of a given country, and ‘people’ as representing this same whole in its political relations. But usage often confuses these two words; and under the Constitution of 1791, the formula was adopted: the nation, the law, the king.” Littré, Dictionnaire, 3:692. Littré’s attempt to stabilize the meaning of nation and peuple through reference to the Constitution of 1791, which instituted a short-lived constitutional monarchy, may not be fortuitous: despite his republicanism, Littré betrays a lack of sympathy with the claims to popular sovereignty of both the Revolution of 1848 and the 1870 Paris Commune. See Émile Littré, Comment j’ai fait mon Dictionnaire de la langue française, nouv. éd. (Paris: Librairie Ch. Delgrave, 1897), 7–8, 35–36; and Jean Hamburger, Monsieur Littré ([Paris]: Flammarion, 1988), 101–2, 201.

-

[54]

Frank Luther Mott, A History of American Magazines (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1957–68), 1:573.

-

[55]

[Mary Swinton Legaré Bullen], “Biographical Notice,” in Hugh Swinton Legaré, Writings of Hugh Swinton Legaré, ed. by his sister [Mary Swinton Legaré Bullen], 2 vols. (Charleston, SC: Burges & James, 1845–46), lvii.

-

[56]

Mott, A History of American Magazines, 1:573–75.

-

[57]

Unsigned review, Southern Review, 60.

-

[58]

For Legaré, see [Bullen], “Biographical Notice,” 1:v–lxxii. For Henry, see National Cyclopaedia of American Biography, 63 vols. (New York: James T. White & Company, 1898–1984), 11:32-33, and John R. Shook, ed., The Dictionary of Early American Philosophers, 2 vols. (New York: Continuum, 2012), 1:510–11.

-

[59]

Hutchison, Apples and Ashes, 24. Hutchison is discussing the first issue of the Southern Literary Messenger published in August 1834 in Richmond, Virginia.

-

[60]

“Béranger, his genius and influence,” Knickerbocker Magazine 2, no. 3 (September 1833): 172.

-

[61]

Ibid.

-

[62]

Ibid., 173.

-

[63]

Ibid., 175.

-

[64]

Ibid., 177.

-

[65]

Ibid., 177. The original, from the Oeuvres complètes of 1834, is: “Hennis d’orgueil, ô mon coursier fidèle! / Et foule aux pieds les peuples et les rois” (“Neigh with pride, my faithful steed, and trample peoples and kings”), Béranger, Oeuvres complètes (1834), 3:35.

-

[66]

“Béranger,” Knickerbocker, 178-80. “The field of Asylum.” See Hartmann and Millard, Le Texas, ou, Notice historique sur le Champ d’Asile (Paris: Béguin, Béchet, Delaunay; Gand: Houdin, 1819).

-

[67]

The first three are from “Songs of Pierre Jean de Béranger,” signed V., Tait’s Edinburgh Magazine, no. 14 (May 1833): 159–62; for the last, attributed to Dr. Bowring, I have not been able to locate an earlier publication.

-

[68]

“The Good Old Woman.” “Béranger,” Knickerbocker, 180-182.

-

[69]

Ibid., 183.

-

[70]

Ibid., 185. The original is: “Je n’aperçois plus d’oppresseurs. / La presse n’est plus enchaînée” (“I see no more oppressors. The press is no longer in chains”). See Béranger, Oeuvres complètes (1834), 2:356.

-

[71]

Ibid., 187. The original is: “Mon bon Roi, vous me le paierez” (“My good king, you will pay me for it”). 1829 was the year of Béranger’s second imprisonment. See Béranger, Oeuvres complètes (1834), 3:256.

-

[72]

Pierre-Jean de Béranger, Songs of Béranger, translated by the author of the “Exile of Idria” etc., with a sketch of the life of Béranger up to the present time, [trans. John Gervas Hutchinson Bourne] (London: William Pickering, 1837).

-

[73]

Phillip Buckner, “Bourne, John Gervas Hutchinson,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 7 (University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–), http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/bourne_john_gervas_hutchinson_7E.html.

-

[74]

[John Gervas Hutchinson Bourne], The Exile of Idria: A German Tale, in Three Cantos (London: Cochrane and M’Crone, 1833). The attribution for this work is given in Buckner, “Bourne.”

-

[75]

Béranger, Songs (1837), x.

-

[76]

Ibid., 72, emphasis mine. “I have acquired a taste for the Republic / Since I have seen so many kings.” The lines are given in French under the title.

-

[77]

Emphasis mine. “Little bilious Jesuits! Thousands of other little priests carrying little communion wafers!” I am quoting from the edition Bourne says he used (see ibid., xv and 1): Pierre-Jean de Béranger, Chansons de Béranger, éd. complète, entièrement conforme à la nouvelle édition que l’auteur vient de publier à Paris (Bruxelles: Louis Hauman et compe, 1836), 480.

-

[78]

Ibid., 139. Emphasis mine.

-

[79]

Ibid., 16.

-

[80]

Béranger, Chansons (1836), 62. “Spin, spin, Lise. In vain your linen is getting tangled; with another spindle, no, you will not spin.” Which linen is in disarray, and which spindle is desired, should be evident.

-

[81]

Joy Bayless, Rufus Wilmot Griswold: Poe’s Literary Executor (Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press, 1943), v.

-

[82]

Ibid., 72. The review is reproduced in William F. Gill, The Life of Edgar Allan Poe, 3rd ed. (London: Chatto and Windus, 1878), 327–46; no copies of the original survive.

-

[83]

Pierre-Jean de Béranger, The Songs of Béranger in English, with a Sketch of the Author’s Life, [ed.. Rufus Wilmot Griswold] (Philadelphia: Carey and Hart, 1844), iii.

-

[84]

Pierre-Jean de Béranger. “Le roi d’Yvetot, from De Beranger,” trans. J. Waring, Metropolitan Magazine 13, no. 52 (Aug. 1835): 369.

-

[85]

Pierre-Jean de Béranger, “Secret Courtship, from the French of Béranger,” New York Morning Herald 3, no. 26 (July 26, 1837): 4, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov.

-

[86]

Thomas Smibert, Io Anche! Poems, Chiefly Lyrical (Edinburgh: James Hogg; London: R. Groombridge & Sons, 1851), 214–16.

-

[87]

Béranger, Songs, trans. Bourne, 100–102, 51–52, 44–45, 157–59; Béranger, Songs, ed. Griswold, 121–23, 119–20, 113–14, 126–28.

-

[88]