Abstracts

Abstract

The present paper discusses issues related to the translation of the English personal pronoun you in the French translations of Virginia Woolf’s The Waves (1931). There are two published French translations of The Waves. The first one, Les Vagues, was translated by Marguerite Yourcenar and published in 1937. Around fifty years later, another version was published, under the same title but this time translated by Cécile Wajsbrot (1993). The two versions differ significantly when the use of tu and vous is concerned. This paper is concerned specifically with the original’s mind-style (Fowler 1977) in other words, the way the characters’ perceptions and thoughts, as well as their speech, are presented through language and how this is rendered in the translations. The quantitative analysis was realised using corpus-based studies tools which proved to be an asset in helping to identify the novels’ mind-style.

Keywords/Mots-clés:

- Virginia Woolf’s The Waves,

- French translation of you,

- corpus-based translation studies,

- mind-style

Résumé

Dans cet article, l’auteur examine la traduction du pronom personnel anglais « you » dans les deux traductions françaises de The Waves de Virginia Woolf (1931) : Les Vagues traduit par Marguerite Yourcenar (1937) et la traduction de Cécile Wajsbrot (1993) du même titre. Ces deux versions présentent des différences significatives quant aux choix des traductrices entre « tu » et « vous ». L’auteur étudie le « mind-style » (Fowler 1977) de l’original, c’est-à-dire la façon dont la perception, les pensées ainsi que le discours des personnages sont présentés par le biais du langage et la façon dont ce « mind-style » est rendu dans les traductions. L’analyse quantitative a été réalisée en utilisant les outils des études de corpus qui ont énormément facilité l’identification du « mind-style » des trois romans.

Article body

Introduction

When reading Woolf’s The Waves, one gets the feeling of being immersed into a world in which individuals keep merging and separating. The novel is constructed around the rhythm of waves breaking on a shore: the characters talk to themselves or to one another the one after the other in interior monologues, they grow up together, they grow apart, they reunite and separate again. There is a subsequent ambiguity to this continuous movement as it can be hard to understand where one character’s self starts and the others end. This ambiguity is ultimately reflected in the novel’s language. Indeed, it is sometimes not clear whom the characters are addressing: are they talking to one individual or to the whole group? And this is mainly due to the inherent ambivalence of the English pronoun you, which can serve to address one person in a polite manner or two or more people. This ambiguity is hard to convey in French because the translator has to choose between vous or tu depending on the situation which inevitably ends up disambiguating the situation.

In this paper, I discuss issues related to the translation of the English personal pronoun you in the two published French translations of Virginia Woolf’s The Waves (1931): Les Vagues, translated by Marguerite Yourcenar (1937) and Cécile Wajsbrot (1993). It will be shown that the two versions differ significantly when the use of tu and vous is concerned. I am concerned specifically with the way the characters’ perceptions and thoughts, as well as their speech, are presented through language, which is known as the novel’s mind-style (Fowler 1977), and how this is rendered in the translations. I am using corpus-based studies tools for the quantitative analysis, which proved to be an asset in helping to identify the novels’ mind-style.

Mind-style

In a work of fiction, a novelist creates a fictional world which is presented from a particular angle, and is refracted through the values and views of a character or narrator. Consequently, as readers we are given access to the world of the fiction through a person’s view of the fictionally created world.[1] Point of view can be divided into two categories: focalisation,[2] which relates to the question of whose eyes and mind witness and report the world of the fiction, and mind-style, which concerns the individuality of the mind that does the focalising. Mind-style is a product of the way the characters’ perceptions and thoughts, as well as their speech, are presented through language. Mind-style will thus be used to talk about the characters’ language and how their use of language, more specifically their use of you, reflects their perception of reality and defines their relationships.[3]

The translation of you

One cannot talk about the use of you without referring to notions of politeness. Politeness is a sociocultural phenomenon at the heart of basic social guidelines for human interaction. It reflects certain social and behavioural norms and rules which must be applied or observed in a given society in order to be “polite”, i.e. showing consideration to others and displaying good manners. Hence, politeness has a social function, which is reflected in the whole society and links it to speech styles and formality. The linguistic expressions of politeness vary between cultures and communities and most of all between English on the one hand and languages like French, Spanish or Italian on the other hand, because these languages are built upon a “tu/vous subsystem” which is no longer used in English.Tu and vous are surface linguistics forms used as indices of politeness norms and as such, they are examples of how language systems impose certain politeness norms. They reflect the participants’ relative position in the social hierarchy, i.e. “social distance”, but their use is also dependent on other factors including gender or age. Brown and Gilman (1960) discuss the notion of “power semantic” and explain that the use of tu and vous is “nonreciprocal; the superior says T[u] and receives V[ous]” (1960: 255). Their study follows the evolution of power semantic in history and they explain that the use of pronouns has evolved with vous in the singular now connoting high status and elegance:

for many centuries French […] pronoun usage followed the rule of non-reciprocal T-V between persons of unequal power and the rule of mutual V or T (according to social-class membership) between persons of roughly equivalent power.

1960: 257

Brown and Gilman also discuss the use of these pronouns in terms of intimacy (tu) and formality (vous). On the whole, the use of vous in the singular is a form of address to a person of superior power[4]. In other words, according to the strength, age, sex, profession of a person, a relation of respect requires the use of vous. This relation is most of the time asymmetrical or non-reciprocal which means that someone using tu can receive a vous and vice versa. They also refer to the notion of solidarity to explain reciprocal or symmetrical norms of address. This concept requires the use of tu where this tu is the mark of a very close relationship or intimacy as well as feelings of belonging to the same social rank, for instance, or a mark of having the same political convictions, religion or profession. Hence, most of the time children address their parents and brothers and sisters with tu as well as lovers and close friends. Interestingly, it is always the person having the highest social status who has the responsibility to initiate the tu. However, tu can be used in a completely different manner to express condescension since the use of tu or vous depends on the level of formality or politeness involved between the interactants.

Baker (1992) illustrates the difficulty of translating you in one of the French translations of Agatha Christie’s Crooked House (1949). The characters are a young man, Charles, and a young lady, Sophia, who have worked together and have been friends for some time. Charles has just asked Sophia to marry him:

‘Darling- don’t you understand? I’ve tried not to say I love you-’

She stopped me.

‘I do understand Charles. And I like your funny way of doing things.’

1992: 97

In French, the nature of the relation between the two characters has to be reflected in the choice of pronouns, i.e. using vous or tu:

– Mais vous ne comprenez donc pas? Vous ne voyez donc pas que je fais tout ce que je peux pour ne pas vous dire que je vous aime et…

Elle m’interrompit.

– J’ai parfaitement compris, Charles, et votre façon comique de présenter les choses m’est très sympathique.

ibid

The use of vous conveys a level of formality and politeness to the French text that is not overtly present in the original. The translator had to make a conscious choice between vous and tu according to the characters’ relationship or his or her interpretation of the characters’ relationships. For instance, he or she might have considered the period and concluded that the use of tu would have been a violation of a communicative norm and more precisely of politeness and social norms which stipulate that two persons of opposite sex and in a certain rank of society (high classes) are required to address each other with vous. Tu would have conveyed a relationship of familiarity that the translator thought did not exist between the two characters.

This brief example shows that translating from English into French requires the translator to make conscious choices about the nature of the relationships among participants and their social standings or gender to render formality or deference. The shift from vous to tu is a “familiar problem for screen translators as well as translators of novels” (Hatim and Mason 1990: 82) and in the rest of this paper, I will analyse and comment on Marguerite Yourcenar and Cécile Wajsbrot’s choices. However, before investigating the use of you in Woolf’s The Waves, I would like to introduce briefly the research paradigm in which this study is situated: corpus-based translation studies.

Corpus-based translation studies

Since 1993, researchers have started to use corpora in translation studies and develop corpora specifically for this use. The term corpus refers to a collection of texts that is held in machine-readable form and can consequently be analysed both automatically and/or semi-automatically in a variety of ways. Corpus-based studies have developed rapidly[5] and focused on recurrent features of translated language known as “normalisation” and “simplification” (see, for example, Baker 1993, Kenny 2001; Laviosa 1997; Olohan and Baker 2000). Moreover, recent studies investigate certain relationships between originals and their translations (see Munday 1998 and 2003; and Bosseaux 2001, 2004, 2004a), and corpus techniques and tools are being employed to identify the translators’ “style” in their translations (Baker 2000).

Studies in corpus-based projects can be hypothesis-driven and aim at finding textual evidence for abstract notions like “normalisation” or “simplification” or data-driven, and in this case, they set out to describe low-level linguistic features of texts which will or will not be explained in terms of these abstract notions. Whatever the type of project, most corpus-based translation studies are designed to show what electronic corpora can do when compared to manual studies. This is the view adopted in the present study, which sets out to demonstrate that corpus-based translation studies and its tools can greatly facilitate and sharpen the process of comparison.

This short study uses a parallel corpus composed of one English novel and its two published French translations: Virginia Woolf’s The Waves (1931), and its two translations (Les Vagues, 1937, translated by Marguerite Yourcenar and Les Vagues, 1993, translated by Cécile Wajsbrot). The relevant texts have been scanned and put in machine-readable form and I study them using corpus-analysis software tools and techniques (WordSmith Tools and Multiconcord).

You in The Waves

The Waves is composed of interludes in which a narrator speaks and series of soliloquies where six characters speak in the first person and address each other using the personal pronoun you. Deixis is the system of internal references of which I is the key (Benveniste (1966, 1972) and I is a function that presupposes other roles, most particularly you, as the other of the discourse. Hence, the personal pronoun you in the soliloquies or interior monologues of The Waves is used to identify the six participant(s).

I would like to emphasise again that it is hard to evaluate The Waves in terms of formality and distance because there is always distance between the characters even when they are together as they are always trying to decide where one of them leaves off and another one begins. This difficult process demands perspective and protection from merging or enmeshment and Woolf seems clear that these characters are hopelessly enmeshed even as they are totally isolated and alone. As mentioned previously, in English you allows conveying this ambiguous state whereas French pronouns vous and tu disambiguate the situation. Reflecting on this issue, Toni McNaron, a professor in English at the University of Minnesota, told me: “I wish there were a way to combine the meanings of vous and tu into a new pronoun, in any language we could find or conceive” (private email conversation 2000). However, without the existence of such a pronoun, vous could be argued to convey the ambiguity of the original, to a certain extent, as will be argued later on.

Using a piece of software called WordSmith Tools, I obtained the number of times you and its derivatives[6] appear in The Waves:

Table (a)

You and derivatives in The Waves

The percentage indicates the ratio of the word under analysis to the overall number of words. Hence, there are 312 instances of the word “you” in The Waves and it accounts for 0.40% of all the words in the text. There are also 109 instances of your, 6 of yours, 6 of thou, 1 of yourself, and 1 of yourselves. In French, the translation of these words is multiple with tu, and vous for you as personal pronoun subject, e.g. “tu marches” and “vous marchez” (you walk) and “tu marches” (you walk). Te/t’, toi and vous are the translations of the personal pronoun object, e.g. “je te/vous pardonne” (I forgive you), “je t’aide” (I help you), “c’est toi/vous que j’aide” (It’s you I help/I help you). Ton, ta, tes, votre, vos, are the translations of the possessive adjective your, e.g. “ton/tes choix”, “votre/vos choix”, “ta/tes voiture (s)” (your choice(s), you car(s)). Le(s) tien(s), la/les tienne(s), le(s) vôtre(s), la vôtre are the translations of the possessive pronoun yours; toi-même is the translation of yourself and vous-même(s) of yourselves.

Vous, tu and derivatives in Les Vagues (Yourcenar, 1937)

Since the French versions are longer than the English text[7]; the percentages are in fact more pertinent than the absolute figures. The figures for vous and its derivatives are as follows:

Table (b)

Vous and derivatives in Yourcenar’s Vagues

Using the “joining” facility of WordSmith Tools, the entries (377, 48, 63, 5 and 3) can be manually joined in order to have a total for vous and its derivatives. The program then put the joint frequencies of all the marked words with the frequency of the one that was marked first:

Table (c)

Wordlist’s “Joining” facility

There are 496 instances of vous and its derivatives, i.e. they represent 0.53% of the text.

The figures for tu and derivatives are as follows:

Table (d)

Tu and derivatives in Yourcenar’s Vagues

When retrieving the data with Wordlist, one has to be aware of homonyms. For instance, in French ton can mean your but it can also mean tone or pitch. There were initially 7 instances of ton but only one was referring to your. There was also a possible misunderstanding of the occurrence of t in reflexives as the software was computing all instances of the single letter and was counting t in expressions like “semble-t-il” or “murmura-t-elle”. There were initially 24 instances of t and I used another piece of software called Multiconcord[8] to select those which corresponded to te/t’ and found only two.

Table (e)

Progress report window indicating the number of items found in the ST (hits)

Table (f)

Results window allowing selecting and viewing the hits

Hence, in Yourcenar’s translation, there are 28 words which correspond to the second person singular pronoun tu, which means that tu and its derivatives make 0.03% of the text. The total was reached by using the same “joining” procedure described previously. Of these 28 instances, there were 5 that actually corresponded to the English “thou”, which appears in a poem recited by one of the characters. Yourcenar thus uses tu and its derivatives 23 times to translate you and its derivatives when they are used to identify the other participants in the discourse.

Vous, Tu and derivatives in Les Vagues (Wajsbrot 1993)

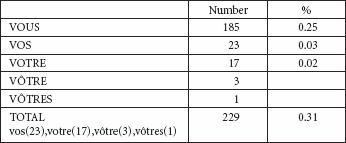

The figures for vous and derivatives are as follows:

Table (g)

Vous and derivatives in Wajsbrot’s Vagues

There are 229 instances of vous and its derivatives, i.e. they represent 0.31% of the text. Let’s now consider the figures for tu and its derivatives:

Table (h)

Tu and derivatives in Wajsbrot’s Vagues

There were initially 42 instances of t’ but only 18 stood for te/t’. There were 30 instances for ton and 25 of these were possessives. In Wajsbrot’s translation, there are 233 cases which correspond to the use of the second person pronoun of the singular, i.e. it represents 0.31% of the text.

Summary

Table (i)

Summary

The statistics show that Wajsbrot used an almost identical number for tu and vous as there is the same ratio of tu and vous and their derivatives (0.31%). Yourcenar’s use of vous and derivatives is much higher: 0.53% against 0.03% for tu and derivatives. I believe that these figures point to microtextual shifts that will impact on macrotextual aspects of the text related to the novel’s mind-style, as the increased use of tu will affect the distance and register of the translations. Corpus-based studies tools allowed me to gain a rapid access to the three novels’ structural make up, i.e. their linguistic composition. The quantitative analysis done, I could concentrate on the qualitative analysis. Let’s now look at specific passages, first with Yourcenar’s use of tu, ton and tes.

Tu/ton/tes in Yourcenar

In order to assess these macrotextual shifts related to the narrative structure, microtextual shifts are considered using Multiconcord. The examples have been located using the French text as “source” text to be able to look for instances of tu:

Table (j)

Multiconcord’s search instructions window

Table (k)

Result window allowing seeing the source text along with the target text

Yourcenar uses tu 14 times, five of which are in a poem told by one of the characters, Louis[9]. Hence, there are 9 instances of tu that correspond to the English you when it is used in the characters’ discourse. There were also two examples of tes. After investigating all these passages, I came to the conclusion that tu and its derivatives in Yourcenar’s translation are used when characters speak to themselves and when they address Percival, the seventh character in The Waves who never speaks. It is also used when the characters address entities like friendship, death or the “western wind”, i.e. as a lyrical tu. For instance in the following extract, Rhoda speaks to herself:

Rhona is one of the three female characters, which all have very different personalities. She is a passive character and most of the actions she is involved in are done to her. In this example, she expresses the end of a process without involving herself saying “this is the end”. Yourcenar translates this process with “tu as atteint le but” [you reached the goal] whereas the original conveyed the idea that something had reached its course. Hence, the mind-style of the original and that of the translation varies since Rhona’s participation in the action is expressed differently.

In the following extract, Yourcenar also uses tu when Bernard addresses “the western wind”:

I thus discovered that when the characters talk to one another, Yourcenar privileges vous. Reasons behind her choices could be explained in terms of the period in which she was translating the book (1937), as the usage of tu seemed to be not as widespread as when the second translation was written (1993). However, since the children have been raised together, tu could have been used for one to one conversation when the characters are children and later on when they are adults. Having considered Yourcenar’s use of vous and tu, I am turning now to Wajsbrot’s choices.

Tu in Wajsbrot’s translation, vous in Yourcenar’s

At the beginning of the novel, the children talk and define themselves by saying what they see and what they think of each other. In the following passage, Susan talks to Bernard and Wajsbrot’s use of tu displays more intimacy or closeness between the two children than Yourcenar’s vous, which creates distance as can be seen in the following extracts from a dialogue between Bernard and Susan:

In this passage, it is clear that Susan is talking to Bernard because she uses twice the expression “making phrases” which is linked to this character. Indeed, Woolf uses specific expressions and motifs throughout the novel which are significant to understand the characters’ personalities and development. For instance, Rhoda is associated with the basin in which she rocks petals; Jinny is linked to the dancing leaf that echoes her fluidity and Louis to the beast that enforces him in solitude. Hence, this is a one-to-one conversation and both translations convey a different relationship between the two children.

This passage is again more formal in Yourcenar’s translation with the use of vous and imperatives in the plural second person (e.g. courbez-vous). The translations also convey two different perspectives as Bernard, in Yourcenar’s translation, is more involved in the action with the use of “fuyons” [let’s run away], i.e. they are running away together, whereas in Wajsbrot’s translation, Bernard gives orders or advice to Susan only; using “cours” [run]. In other words, Bernard takes on different roles in the translations, which has consequences on the texts’ mind-styles.

As I studied all the examples taking place during the characters’ childhood phase, it became apparent that for one to one conversations Wajsbrot privileges tu over vous and that this choice brings about differences in terms of mind-style, distance and register when compared with Yourcenar’s translation of the same passages. The children’s conversations are more formal or ceremonious in Yourcenar’s translation than in Wajsbrot’s which displays a greater level of intimacy and familiarity. Moreover, because The Waves follows the lives of its six characters, they also interact when they are adults and the translators’ choices are also very telling at this later stage. I have selected two examples from the character’s adulthood which exemplify and confirm the translators’ strategies:

This passage shows the ambiguity of the English pronoun you. The characters are gathered for dinner and speak the one after the other. Yourcenar chooses to translate this you with vous throughout the passage. She might have thought that Jinny was addressing the group but most of the times, it can also be interpreted as a formal vous used to address one character. However, since the passage starts with “but” it is reasonable to think that Jinny actually replies to the character that was speaking before her, Louis, and in that case Yourcenar’s use of vous conveys distance and formality between the characters. Wajsbrot chooses tu, which is not ambiguous and forecloses the possible ambiguity of the original by conveying more intimacy and closeness during the discussion. Nevertheless, on one occasion, the context makes it clear that Jinny is talking to the whole group when she says: “your hands to your ties” because of the plural form. Yourcenar translates “vos noeuds de cravates” [your knots of ties] which also addresses the whole group, whereas Wajsbrot translates “la main à ta cravate” [the hand to your tie] which addresses only one character. Hence, the context can help to disambiguate the use of “you” and we end up with different addressees, which have consequences on the way we interpret the way the characters interact in this passage and by extension, in the novel.

In the following passage, Louis speaks to Rhoda. At this stage in the novel, they are lovers:

As mentioned previously, Louis and Rhoda have known each other since childhood and are lovers. Yourcenar’s vous creates an unnecessary distance between the two characters whereas Wajsbrot’s use of tu conveys a legitimate intimacy to the passage.

In the second passage, the characters are gathered after having been separated for a long time and Neville comments on their emotions:

WOOLF P417 S1 <p><s>’Now sitting side by side,’ said Neville, `at this narrow table, now before the first emotion is worn smooth, what do we feel? <s>Honestly now, openly and directly as befits old friends meeting with difficulty, what do we feel on meeting? <s>Sorrow. <s>The door will not open; he will not come. <s>And we are laden. <s>Being now all of us middle-aged, loads are on us. <s>Let us put down our loads. <s>What have you made of life, we ask, and I? <s>You, Bernard; you, Susan; you, Jinny; and Rhoda and Louis? <s>The lists have been posted on the doors.

This passage clearly shows that when Yourcenar translates an individual you, she uses a formal vous.

Conclusion

As discussed previously, the original English text is difficult to comprehend because there is always a mixture between distance and intimacy when the characters address one another. I emphasised that answers can be found in the context (e.g. “ties”) or by referring back to the previous paragraph but what stands out is that in many cases, ambiguity prevails. As a matter of fact, the characters often mention that they do not know when their own selves start and when their friends’ selves end. As Bernard says, they are:

A single flower as we sat here waiting, but now a seven-sided flower, many-petalled, red, puce, purple-shaded, stiff with silver-tinted leaves - a whole flower to which every eye brings its own contribution!

Woolf 1931: 151

However, when translating into French, the translators have to make a conscious choice as to whom they address and how.

Table (l)

Summary

Figures have shown that the first translator, Yourcenar, opted for vous more often than for tu and that the second translator, Wajsbrot, used a more even distribution of vous and tu. The software could not tell me what this “you” what referring to but when I went through the examples, I found that for one to one conversation, Wajsbrot opted for an intimate tu whereas Yourcenar used a more formal vous. As discussed earlier on, it is sometimes not clear whether the English you serves to address someone formally (vouvoiement) or the whole group. It might be that Yourcenar privileged vous not only to address someone as vous but to address the group because she thought of the characters as a group and that Wajsbrot considered these characters as individuals and favoured an intimate tu. I would like to claim that regardless of the reasons behind the translators’ choice, the choice between tu/vous has consequences on the register and mind-style of the novel. In other words, the microtextual shifts have consequences on the macrostructure and point of view of the novel since Yourcenar’s choice of vous over tu renders the text more formal and distant than Wajsbrot’s translation, which is more intimate and conveys more familiarity between the characters. However, if we compare the translations with their original, one can argue that Yourcenar’s choice of vous as the more inclusive pronoun (both singular and plural) reflects more adequately the original’s fluidity and undecidability as regards who exactly is being addressed at any one moment. Whatever explanations we choose, it is indisputable that the worlds depicted in the translations present different relationships between the characters and corpus-based translation studies tools helped me to gain an insight of the texts, which a manual analysis would not have allowed. This is not to say that a manual analysis would not have allowed insight to be gained into the texts but the difference is the extent to which this would have been possible. The tools allow breadth and depth of coverage but a manual analysis would only allow depth of coverage in selected passages not on the whole text as it would be impossible to maintain the level of concentration required to find all the instances of “you” in The Waves and its translations. In other words, I have used corpus processing software as tools to facilitate the quantitative analysis. The tools have provided figures that I exploited in my qualitative analysis and as such they greatly facilitated the analytical process. Finally, I would like to add that corpus processing tools give access to a larger amount of data, when compared to manual analyses, which makes it feasible to pursue macroanalyses by going from the microstylistic analysis of individual passages to the macrostylistic interpretation of the whole text. However, as Opas and Rommel point out, even though the computer can make “life easier for the literary critic”, it cannot “generate meaning and it will always remain a tool” (1995: 262), which needs to be emphasised as this is the view adopted in my work.

Appendices

Notes

-

[1]

The narrator is not necessarily a person and could be an animal, an inanimate object or an anonymous/faceless narrator. Person is used here as a convenient notation for a faceless narrator.

-

[2]

A term created by Genette (1980).

-

[3]

In modern stylistics, one of the most influential studies is Halliday’s (1971), a study of William Golding’s The Inheritors, which illustrates how the analysis of transitivity can contribute to an understanding of the particular mind-style projected in a text, i.e. the world-view of a narrator or a character, constituted by the ideational structure of the text.

-

[4]

It must be noted that these are general conclusions concerning the use of tu and vous and that usage also differs from one individual to another.

-

[5]

See Laviosa (2002) and Olohan (2004) for comprehensive accounts of the theories and concepts used in corpus-based translation studies.

-

[6]

The possessive adjective your, possessive pronoun yours, and personal pronouns yourself and yourselves. The old English second person pronoun of address thou is also used in the original.

-

[7]

Woolf’s The Waves is composed of 78,104 words, Yourcenar’s translation of 91,623 words and Wajsbrot’s text of 74,406 words.

-

[8]

Multiconcord is a multilingual concordancer developed by David Woolls and a consortium of European Universities as part of the Lingua program (Woolls 1997). It allows the user to select a pair of languages, i.e. a source and a target language, and to enter a search pattern of words or phrases in a selected language, which may or may not be the source language. Multiconcord then gives a list of all the source items it has found, the hits, and allows seeing the full sentence or sentences in the source language along with the sentences which the aligning engine considers to be equivalent in the target language. The aligner works within the parallel paragraphs and attempts to match up all sentences until it reaches the sentence for which the search routine has recorded a hit. Then, it records the matching location in the target language paragraph.

-

[9]

Interestingly, Wajsbrot keeps the poem in English in her translation.

References

- Baker, M. (1992): In Other Words. A Coursebook on Translation, London, Routledge.

- Baker, M. (1996): “Corpus-based Translation Studies. The Challenges that Lie Ahead”, in H. Somers (ed.) Terminology, LSP and Translation, Amsterdam, John Benjamins.

- Baker, M. (2000): “Towards a Methodology for Investigating the Style of a Literary Translator”, Target 12-2, p. 241-266.

- Benveniste, E. (1966): Problèmes de linguistique générale 1, Paris, Gallimard.

- Benveniste, E. (1972): Problems in General Linguistics, translated by Mary Elizabeth Meek, Miami Linguistics Series, Coral Gables, Florida, University of Miami Press.

- Bosseaux, C. (2001): “A Study of the Translator’s Voice and Style in the French Translations of Virginia Woolf’s The Waves”, in M. Olohan (ed.) CTIS Occasional Papers 1, Manchester, Centre for Translation and Intercultural Studies, UMIST, p. 55-75.

- Bosseaux, C. (2004): “Point of view in translation: a corpus-based study of French translations of Virginia Woolf’s To The Lighthouse”, Across Languages and Cultures 5-1, p. 107-122.

- Bosseaux, C. (2004a): “Translating point of view: a corpus-based study”, Language Matters 35-1, p. 259-274.

- Brown, R. and A. Gilman (1960): “The Pronouns of Power and Solidarity”, in T. Sebeok (ed.) Style in Language, Cambridge, MIT Press.

- Fowler, R. (1977): Linguistics and the Novel, Methuen.

- Genette, G. (1980): Narrative Discourse. An Essay in Method, Ithaca, New York, Cornell University Press.

- Halliday, M.A. K. (1971): “Linguistic function and literary style: an inquiry into the language of William Golding’s The Inheritors”, in S. Chatman (ed.), Literary Style: a Symposium, London, Oxford University Press.

- Hatim, B. and I. Mason (1990): Discourse and the Translator, London, Longman.

- Kenny, D. (2001): Lexis and Creativity in Translation: A Corpus-based Study, Manchester, St Jerome.

- Laviosa, S. (1998): “The English Comparable Corpus: A Resource and Methodology” in L. Bowker, Michael Cronin, Dorothy Kenny and Jennifer Pearson (eds.), Unity in Diversity: Current Trends in Translation Studies, Manchester, St. Jerome.

- Laviosa, S. (2002): Corpus-Based Translation Studies: Theories, Findings, Applications, Amsterdam, Rodopi.

- Olohan, M. and M. Baker (2000): “Reporting that in Translated English: Evidence for Subconscious Processes of Explicitation?”, Across Languages and Cultures 1-2, p. 141-158.

- Olohan, M. (2004): Introducing Corpora in Translation Studies, London, Routledge.

- Opas, L. L. and T. Rommel (1995): Introduction to “New Approaches to Computer Applications in Literary Studies”, Special Section, Literary and Linguistic Computing 10-4, p. 261-262.

- Wajsbrot, C. (1993): Les Vagues, Paris, Calmann-Lévy.

- Woolf, V. (1931) (1992): The Waves, Oxford, Oxford University Press.

- Yourcenar, M. (1937) ( 1974): Les Vagues, Paris, Editions Stock.

List of tables

Table (a)

You and derivatives in The Waves

Table (b)

Vous and derivatives in Yourcenar’s Vagues

Table (c)

Wordlist’s “Joining” facility

Table (d)

Tu and derivatives in Yourcenar’s Vagues

Table (e)

Progress report window indicating the number of items found in the ST (hits)

Table (f)

Results window allowing selecting and viewing the hits

Table (g)

Vous and derivatives in Wajsbrot’s Vagues

Table (h)

Tu and derivatives in Wajsbrot’s Vagues

Table (i)

Summary

Table (j)

Multiconcord’s search instructions window

Table (k)

Result window allowing seeing the source text along with the target text

Table (l)

Summary