Abstracts

Abstract

The COVID-19 global pandemic forced most nightlife venues to shut their doors in March 2020, leading to a loss of employment for nighttime employees and freelancers as well as a loss of revenue for the city. As night clubs shut down, the social dancers who fuel this part of the nightlife economy lost access to the spaces where they dance with others who share their musical tastes. Yet seedlings can spring up even in burned over territory. In the face of these pandemic challenges, the dance music scene reinvented itself, shifting from existing in-person to entirely virtual performance. This reimagination of nightlife points to a key element in the resilience of night-time social dancing: community. These virtual dance parties stemmed from, and perpetuated dance communities that replaced, and in some cases redefined, the experiences that dance communities formerly enjoyed in in-person venues. This paper explores this world of virtual dancing. Through conversations with venue owners, performers, and social dancers, as well as through a digital ethnography of virtual dance parties and their corresponding social media pages, this study asks whether and how virtual dance parties replicate the sense of community experienced in in-person dance parties and interrogates what the advent of virtual dance parties means for the future of urban nightlife. Building on the idea that social dancing is a right to the city (Krisel 2020; see also Harvey 2008; Lefebvre 1996), this study also explores how social dancing may also be a right to the internet and explores the parallel between the urban and internet environments as venues where subcultures can form communities and co-create both physical and virtual spaces.

Résumé

La pandémie mondiale de COVID-19 a forcé la plupart des lieux de vie nocturne à fermer leurs portes en mars 2020, entraînant une perte d’emploi pour les employés de nuit et les pigistes ainsi qu’une perte de revenus pour la ville. Avec la fermeture des boîtes de nuit, les danseurs sociaux qui alimentent cette partie de l’économie nocturne ont perdu l’accès aux espaces où ils dansent avec d’autres qui partagent leurs goûts musicaux. Pourtant, les semis peuvent pousser même sur un territoire brûlé. Face à ces défis pandémiques, la scène de la musique dance s’est réinventée, passant d’une performance en personne existante à une performance entièrement virtuelle. Cette réimagination de la vie nocturne renvoie à un élément clé de la résilience de la danse sociale nocturne : la communauté. Ces soirées de danse virtuelles sont nées et ont perpétué des communautés de danse qui ont remplacé, et dans certains cas redéfini, les expériences que les communautés de danse appréciaient auparavant dans des lieux en personne. Cet article explore ce monde de la danse virtuelle. Grâce à des conversations avec des propriétaires de salles, des interprètes et des danseurs sociaux, ainsi qu’à travers une ethnographie numérique des soirées de danse virtuelles et de leurs pages de médias sociaux correspondantes, cette étude questionne si et comment les soirées de danse virtuelles reproduisent le sens de la communauté vécu dans la danse en personne, et interroge ce que signifie l’avènement des soirées dansantes virtuelles pour l’avenir de la vie nocturne urbaine. S’appuyant sur l’idée que la danse sociale est un droit à la ville (Krisel 2020; voir aussi Harvey 2008; Lefebvre 1996), cette étude explore également comment la danse sociale peut aussi être un droit à Internet et explore le parallèle entre l’urbain et Internet. environnements comme lieux où les sous-cultures peuvent former des communautés et co-créer des espaces physiques et virtuels.

Article body

Introduction

The COVID-19 global pandemic hit the nightlife industry like a torpedo. For most cities across the Western world, March 13, 2020, marks the day when the music died: from New York to Berlin, widespread lockdown measures were adopted to prevent the spread of the virus. Given the nature of the nightlife industry, in which people interact in close physical contact, oftentimes inebriated, shutting down these venues was common sense from a public health standpoint. However, they also imposed serious costs on the entire economic ecosystem of the nightlife industry, including loss of revenues to venue owners, loss of employment to nighttime employees and freelancers, and loss of revenue for cities.

Nightlife economies are essential parts of city economies. In Berlin, pre-pandemic nighttime economic activity generated $1.83bn per year in revenue and employed approximately 9,000 workers at 280 legal establishments (The Berlin Club Commission 2018). In New York, pre-pandemic nighttime economic activity generated $35.1bn in revenues per year and $698m in local tax revenues. It also employed 299,000 workers at 25,000 legal establishments (The Mayor’s Office of Media and Entertainment 2019). Survey data collected from the New York City Mayor’s Office of Nightlife and Culture between March 16 and April 3, 2020, found that COVID-19-related restrictions on businesses, workers, and freelancers cost all of the 12,000 survey respondents nearly all their income in the first weeks of the crisis. In particular, venues reported losing 95.0% of $19,000 median weekly income, vendors reported losing 93.4% of $4,000 median weekly income, employees reported losing 95.3% of $830 median weekly income and 93% of their weekly shift hours, and freelancers reported losing 86% of their jobs, averaging 4 per lost gigs per week. Two out of three freelancers reported losing 100% of their weekly jobs (The Mayor’s Office of Media and Entertainment 2021). This was devastating to this culturally and economically important segment of city life.

While venue owners, nighttime workers, entertainers, and cities felt the sharply negative economic impact of the pandemic, the social dancers who fuel part of the nightlife economy as patrons experienced a loss as well. Social dancing is a non-professional form of dance in a social context, which traditionally included partnered dancing like swing and salsa and evolved into individualized forms of dancing in the disco era of the late 60s and early 70s as a way to reject the perceived patriarchal and heteronormative constraints of the dance hall spaces that were popular at the time (Lawrence 2011). Today, most social dancing in nightclubs is defined by bodies moving rhythmically together, yet individually.

Social dancing is more than just going out to clubs. As Emily Witt describes, for many social dancers in the New York dance music scene, “clubbing is a lifeline” where parties are “more than drinking environments: they [are] therapy sessions, fitness routines, community centers, fashion magazines, dating apps, and foster families” (2021: 8). This community is not just individuals sharing experiences, it is an active constituency. From campaigning for the repeal of the Cabaret Law in 2017, which brought dance culture out of hazardous underground spaces into safer regulated ones (Correal 2017), to promoting anti-harassment safer-space programs in venues across New York City, a key program of the newly established Office of Nightlife (Krisel 2020; Lyons 2018; The Mayor’s Office of Media and Entertainment 2021), social dancers in New York have been a cohesive movement advocating for safer spaces to dance. Through these actions, they claimed social dancing as a right to the city (Krisel 2020) by asserting “use value over exchange value, encounter over consumption, interaction over segregation, free activity and play over work” and “developed the ability to manage the city for themselves, [while] giv[ing] shape to the urban” (Purcell 2014: 151).

In the face of these pandemic challenges, the dance music scene reinvented itself from being primarily in-person to becoming entirely virtual. The rest of 2020 after March witnessed a proliferation of virtual dance events borne from existing in-person venues such as New York’s Nowadays and House of Yes to Internet-native venues like Club Quarantine and “United We Stream,” a free clubbing service launched by the Berlin Club Commission trade group, which raised nearly half a million dollars’ worth of donations within two weeks of opening their virtual doors (Schmitz 2020). This reimagining of nightlife stemmed from the core dynamic of nighttime social dancing: participating in a community. These virtual dance parties created communities that attempted to replace, and in some cases redefine, the in-person version of social dancing. It is precisely this sense of community that links social dancing to virtual dancing. As House of Yes’s Cultural and Marketing Director Jacqui Rabkin notes: “We knew our audience would be hungry to connect digitally and dance together in whatever way possible,” highlighting the shared desire to continue dancing by connecting virtually and, in fact, actually growing networks and experiences, since “now, people all over the world can tune in to [its] parties” (Wheeler 2020).

This article explores this new world of virtual dancing. Through conversations with venue owners, performers, and social dancers, augmented by a digital ethnography of virtual dance parties and their corresponding social media pages, this study asks whether and how virtual dance parties replicate the sense of community found in in-person dance parties and questions the meaning of virtual dance parties for the future of urban nightlife. Building on the idea of social dancing as a right to the city (Krisel 2020; see also Harvey 2008; Lefebvre 1996), this study reconsiders social dancing as a right to the Internet and establishes the parallel between the urban and the Internet as environments where subcultures form communities and co-create both physical and virtual spaces.

To gather primary qualitative data on both in-person and virtual social dancing, this study relies on a survey and interviews. The anonymous survey, which was shared on Facebook and by email, received 30 responses. The two dozen structured 30-minute interviews with virtual event organizers and social dancers were conducted over Zoom. The respondents were either self-selected as an option after completing the survey, referred by event organizers, or referred by other social dancers. While the survey questions focused mostly on gathering demographic data on in-person and virtual dancing in addition to types of virtual events respondents attended, the interviews sought to uncover the personal experience of each respondent at in-person and virtual events.

Starting with an exploration of the digital platforms used to support virtual parties, this study investigates the sense of community formed within virtual dance events and compares it with the sense of community formed at in-person dance events. It then develops the concept of the right to the Internet and concludes with some thoughts on the future of virtual dancing within the broader landscape of nightlife.

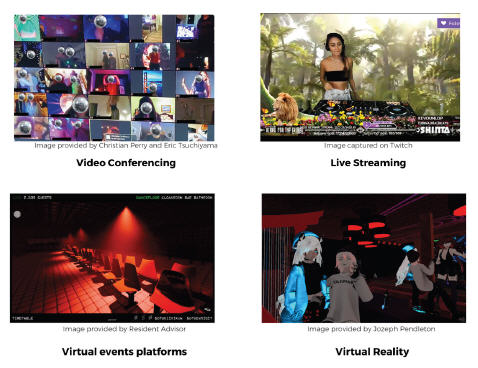

What is virtual dancing? Where does it take place? What are its benefits?

Virtual dancing allows people to engage in social dancing with others on a digital platform. In other words, like social dancing in nightclubs, virtual dancing involves bodies moving individually yet rhythmically together. However, instead of dancing in the same room, dancers congregate in digital spaces. Four main types of digital platforms support virtual dancing: video conferencing (e.g., Zoom), live streaming (e.g., Twitch), virtual event platforms (e.g., High Fidelity), and virtual reality (VR) programs (e.g., VR Chat). While each of these platforms provides a specific way to participate in virtual dancing, they all enable participants to use electronic devices connected to the Internet to tune in within the confines of their private spaces, including using a VR headset to attend VR parties or just using headphones or speakers to listen to the music.

Video conferencing

While video conferencing platforms like Zoom initially sought to facilitate face-to-face virtual meetings, typically within a business setting, the dance music scene quickly appropriated the technology to organize dance parties. From a technological point of view, Zoom has the lowest barrier to entry for a virtual dance event. Since most people use Zoom daily to attend meetings, school courses, and even yoga classes, making the technology almost synonymous with living through the COVID-19 pandemic, it was easy for event organizers and party participants to use it for their own ends. Since Zoom does not require users to create an account to join a meeting, social dancers could attend a dance party just by clicking on a link. Finally, while party organizers typically paid up to $160 a month for an enterprise Zoom account allowing up to 1,000 attendees, participants had no entry cost. Most party organizers suggest that attendees donate to the performers and DJs via a Venmo or Paypal account, though it is unclear how many do so.

A variety of dance party organizers use Zoom for their events, including established dance venues like Brooklyn’s House of Yes, Zoom-native viral parties like Club Quarantine, and smaller, homegrown Zoom-native parties like COVID Disco. While event organizers from House of Yes and COVID Disco agreed to be interviewed for this project, organizers from Club Quarantine did not. However, given that their party became a viral sensation in the first few months of the pandemic, their story was well documented in the press from The New York Times and Bloomberg News to Vice News, and they have a rich social media presence on Instagram.

House of Yes describes itself as a “temple of expression” and hosts a range of events including sober and erotic dance parties with mandatory costumes. During pre-pandemic times, their business model focused on building a community of regulars called “House of Yes BFFs,” recognized as an insider group who embody their mission of self-expression by showing up often and in creative costumes. When House of Yes hosted their first virtual event on March 19, 2020, the organizers called on the “House of Yes BFFs” members to set the tone by bringing a creative energy to the party. The virtual events had a similar set of rules and instructions to in-person events, including encouraging costumes and props, forbidding any forms of harassment, and leading with the motto that attendees are coming to the event as “participants, not consumers.”

Four artists in their early twenties based in Toronto created Club Quarantine (Club Q), a Zoom-native queer dance club. As the story goes, one night the four were video chatting on Instagram when they decided on a whim to snag the @ClubQuarantine Instagram account handle and invited some friends to join them for a party on Zoom. Overnight, the Instagram account attracted over a thousand followers (it had 71K followers in August 2021) (Colyar 2020b; Steinberg 2020). The organizers hosted events every night for the first three months of the lockdown, booking underground queer artists and posting the Zoom link in their Instagram bio when each event started at 9pm ET. As noted in the comments on their Instagram posts, their Zoom parties would max out at the 1,000 limit of participants within seconds of sharing the link by the end of their first week, causing the party’s followers to beg the hosts to let them in. As one social dancer who tuned in to the Club Q parties every night in March said: “It felt like a party that will always be there. It was comforting to be able to join other young queer kids every night at the start of the pandemic.” Club Q is recognized as a pandemic viral sensation, becoming so popular that the Grammy award winning superstar Lady Gaga collaborated with them on a fundraiser for The Marsha P. Johnson Foundation, in support of Black Trans people (Steinberg 2020). Club Q continues to host virtual parties, though with less frequency, and planned its first in-person event in September 2021. Watch Angie Bird’s “Club Quarantine” documentary on Vimeo.[1]

Two New York based performance artists created COVID Disco, a Zoom-native party, as a fun way to connect with friends and family. They hosted weekly parties that expanded in scope through friends of friends. “It was the sweetest part of my week,” said one regular attendee of the COVID Disco parties. “This party was a lifeline,” said another participant, who was living alone during the lockdown. Because the COVID Disco community grew directly out of a group of friends, participants shared a sense of trust and intimacy. The weekly events had specific themes, including 80s or 90s nights, with attendance typically reaching a maximum of 80 guests. The organizers hosted these weekly events from March 2020 through October 2020, at which point a general Zoom fatigue settled in for the COVID Disco regulars.

Almost every Zoom party organizer expressed amazement at how creative the social dancers were with their “box” on Zoom. Organizers and attendees alike describe people decorating their spaces with props such as inflatable palm trees and colorful strobe lights. “People really needed a creative outlet,” said one member of the management team at House of Yes. “These Zoom parties made space for that.” The organizers of COVID Disco shared a similar sentiment: “It far exceeded a traditional dance party. It became this performance art, this experimental theater. We were blown away.”

Among the two dozen social dancers interviewed for this project, many said they enjoyed the opportunity to express their creativity. “I was able to change outfits many times across the span of a party just because the mood struck me,” said one regular COVID Disco attendee. Another social dancer who attended virtual events with House of Yes and Club Quarantine shared that he kept his screen off during his first experience at a virtual dance party. During the second one he turned his screen on but did not dance or wear a costume. However, in preparation for the third event, he decorated his room with colorful string lights and purchased three wigs that he changed throughout the party. “I had never felt so liberated,” he explained. “I felt as though it was safe for me to explore a side of my self-expression that I wouldn’t necessarily have done at an in-person event.”

This social dancer’s experience suggests that these Zoom parties became inclusive and supportive, a view shared by most interviewed participants. They created a virtual stage for extroverts, allowing social dancers to show off their outfits and dance moves in front of an audience. The “spotlight” function on Zoom enabled event organizers to mimic the effect of a dance circle by enlarging a Zoom box so all participants would notice that particular dancer. “For those wanting to show off their moves, Zoom provided more of a platform than a regular dance floor would have. And seeing a dance circle pop off on New York City dance floors is so rare, so this felt kind of special,” said one participant who regularly attended in-person dance parties prior to the pandemic. While some dancers were spotlighted, other attendees would send them encouraging messages in the Zoom chat, such as “Nice moves,” “Yaas! Keep going sister!” and “Love your outfit!”

The Zoom parties were equally inclusive for introverts as well as for people with mental and/or physical disabilities, who cannot usually attend a dance party since these typically occur in spaces designed with an ableist blind spot. “People would message us and be like, ‘Oh my God, thank you so much! As a queer disabled person, this is my first queer club and I’m living my best f**king life. I would have never thought about that because it just wasn’t on my radar,” shared Club Q co-creator Ceréna (Steinberg 2020). “It felt so empowering to have full control over being seen by turning my camera on or off, and to also have the option to leave the party and be on my own in an instant,” explained one attendee who described herself as an introvert. “This definitely helped me with my social anxiety.”

The Zoom parties also enabled more widespread access to dance parties. While most attendees at the House of Yes virtual parties had previously attended their in-person events, the organizers received messages from dancers from as far away as London and Turkey, who were thrilled to finally be able to participate in one of their events. “Thanks to these virtual events, we went global!” said one member of the management team at House of Yes. The organizers at Club Q reported having attendees joining from Poland and Saudi Arabia: “People [are] tuning in from all over the world: places where it’s illegal to be queer, people who are living in homophobic households” are finding safe ways to connect from their bedrooms or even closets (Bird 2020; Steinberg 2020). COVID Disco attendees expressed how important it was for them to be able to connect and dance with their friends and family who lived far away.

Live Streams

While Zoom dance parties are defined by seeing other participants and dancing alone together, the live streams are all about the performers and DJs. Typically hosted on Twitch, a live streaming video subsidiary of Amazon, live streams provide DJs and musicians an opportunity to play for an audience in real time in front of a camera. Audience members can interact with the DJ/musician and each other through a chat, but they cannot see each other. Live streams prioritize the craft of the performer. “In a virtual set, DJs tend to plan their set list in advance as opposed to improvising based on the energy in the room. They treat it as a presentation of their work,” explained a New York-based DJ.

While the audience is invisible to itself, the use of the chat function can still form a sense of community. “I was able to engage in meaningful interactions with people on the chat, which was totally mind blowing for me, because I was literally able to sit in my house and still feel that aspect of community,” one social dancer who attended weekly live streams on Twitch mentioned. “Once I started attending regular live streams by particular artists, people in the chat would start greeting me as I arrived. We kind of expected to find each other there,” explained another participant. Oftentimes, people would also drop Zoom links in the chat for those who did want to dance in community and see each other while listening to the live music.

Others, however, saw these live streams as opportunities to listen to their favorite artists or discover new ones without engaging with other participants or having to be visible to them. “For me, it’s a background setting, not participatory. I want to kick back and listen to some good music without staring at a screen,” a regular in-person social dancer shared.

Virtual-event platforms

Virtual-event platforms operate like video games. Users select an avatar to represent themselves as they dance and explore virtual nightlife spaces, many of which have multiple rooms. Virtual-event platforms typically include spatial audio, which enables full developer control over user positioning, loudness, room attenuation, and other aspects of the audio environment. This means that party organizers have control over the look of the dance space and can set it up so that the music sounds louder as the users move closer to the speakers and quieter as they move away. Attendees wearing headsets with microphones can even speak with fellow attendees using their own voices.

One virtual dance club utilizing a virtual-event platform is the Berlin-based Club Quarantäne (Club Qu)—not to be confused with the Toronto-based Club Quarantine—hosted by Resident Advisor, the largest electronic music digital magazine, events listing, and artist directory. Club Qu is set up to mimic the experience of going to a nightclub. The organizers established a few steps before getting into the club, like waiting in line, facing a cynical virtual bouncer called Geezer, and passing a quiz to test your knowledge of underground house and techno music. These obstacles are supposed to create a sense of exclusivity (Alexander 2020). In practice, social dancers interviewed for this project who attended Club Qu did not find these steps as forbidding as they were meant to be, but that did not take away from the experience.

Once inside Club Qu, attendees can wander virtually through a digital interior, including a coat check where Club Qu merchandise is sold, a bar where attendees can donate to COVID-19 causes, and a bathroom where attendees can interact in a multi-cubicle chat room. “It was so interesting to be able to move through the space and see it crowded with all these avatars. It reminded me of being at an in-person dance party,” explained one attendee. “I also thought it was fun that the only place you could chat with others was in the bathroom and catch random conversations, which also kind of mimicked the experience of being at a nightclub.”

Another social dancer who is a regular attendee at the Burning Man festival said he used High Fidelity, a virtual-event platform, to connect with his fellow Burning Man community in August 2020 after the in-person festival was cancelled. He had initially invited ten people, but over a hundred “Burners” showed up. Since High Fidelity only uses avatars, they ended up running a Zoom meeting on the side so that people could see each other. “That was the first time I thought: Wow! This feels like a real event but just in a virtual space,” he explained.

Virtual Reality

Virtual reality dance parties are similar to the virtual-event platforms, except that participants must use VR headsets to experience the party in 3D. The most popular VR platform used for social dancing is VRChat, a free-to-play multiplayer online virtual reality social platform where players interact with others as 3D character models, or avatars. The VR dance clubs that operate on VRChat, such as DDVR and GrooVR, host regular parties that are promoted on the encrypted chat platform, Discord. The event spaces are created by 3D designers and can take any shape from looking like an abandoned alley, a winter wonderland, or the planet Mars. It is free for anyone to upload a 3D world into VRChat. 3D designers also create and sell avatars, which can take the form of anything from Kermit the Frog to a cat. It is a completely imaginary world where users are free to be whoever or whatever they like. “If you’d like to know what it feels like to go through life being as small as a mouse, you can do that!” explained one VR aficionado.

The experience of participating in a VR dance party can feel almost like attending an event in person. You can walk through the space, feel the sound change depending on where you are, bump into other avatars, and talk to them. “The VR sensory experience is the closest to being in person,” explained one VR dancer. Each VR space can host about 80 attendees, and users can bounce from party to party if they are not interested in the music being played or if they want a different atmosphere. “At the start of the pandemic when I had more time on my hands, I spent a whole day attending VR parties across the world. I went from San Francisco to New York, Berlin, all the way to Japan,” said one participant. “And it’s cool because you meet and chat with so many people along the way!”

The VR dance world has its own economy. 3D designers who create worlds and avatars can sell their designs to party promoters and social dancers, creating a marketplace for digital artists. Though most VR dance parties are free to attend, being able to connect to a VR space does require a certain amount of equipment including a desktop computer with enough RAM space to run the VR Chat program, and a VR headset and motion controllers to see and interact in the virtual world. “You can easily spend upwards of $2,000 to get yourself set up for VR dancing,” stated one social dancer.

Community Through Dancing

Although individuals engage in social dancing for many reasons, they like to meet and dance with others who share their interest in a particular style of music. These communities formed on dance floors resonate with Melvin Webber’s idea of “community without propinquity” in which advancing communications technologies shift the focus of place-based urban communities to other forms of connectivity; leading urban realms to become manifestations of “interest communities” without distinct boundaries (Webber 1964). Dance clubs create community without propinquity, where social dancers come together based on a shared love for dance music and club dancing. When asked to respond to the question “What does community through dancing evoke for you?” social dancers interviewed for this project in addition to the 30 anonymous survey respondents, answered in the following way:

Showing up and seeing people that are familiar. It’s a sense of familiarity but also of commitment, a shared understanding of how you party, how you listen to music. There’s a sense of ethics and etiquette. A sense of freedom.

It’s the holy grail. The thing we are all after. Your chosen family. Finding your people.

It’s primal and tribal. It’s something we’ve always done as humans and it finds a way to manifest itself in different ways throughout the course of human history.

Community through dancing evokes radical self-expression with a communal identity. So, it’s individualism within a collective identity.

Moving simultaneously through dance while also witnessing each person moving in their own way.

A way to connect without speaking—just movement! Sometimes it’s nice to feel that sense of unity without talking.

Allowing your true self to be present, free, and witnessed in a group of people who have come together to share an experience with you.

Freedom.

Coming together in a common love of music.

A sense of physical freedom through shared connection.

Connection, community through the shared language of dance, self-expression, acceptance.

What these responses point to is a sense of connection, liberation, freedom, commonality, familiarity, and communication through movement, which define social dancing communities, both in person and virtually.

In-person dance communities

Given the vast variety of dance music genres from house music to techno, drum-and-bass to dub-step, and beyond, dance music communities are highly diverse. Some operate within the mainstream, listening and dancing to “Top 40” pop music in high-end, expensive nightclubs, while others emerge as underground subcultures, listening exclusively to non-mainstream dance music in warehouse spaces. In her study of British club cultures in the nineties, as Sarah Thornton described, “club cultures are taste cultures” that form temporary or long-lasting “ad hoc communities with fluid boundaries” (1996: 3). Building on Pierre Bourdieu’s concept of cultural capital (1986)—knowledge and social assets that communicate social status—Thornton develops the concept of subcultural capital to describe the kind of cultural capital that comes from hipness, operating within subcultures where a particular kind of niche language and knowledge base is necessary in order to be accepted within the scene. Subcultural capital can be embodied and objectified (Thornton 1996).

In the context of the New York underground dance-club scene, which in terms of genre favors deep house and techno, subcultural capital is communicated through wearing mostly black or dark clothes, edgy and colorful haircuts, and combat-style boots. “It’s a techno goth look. Dark and industrial, yet playful and futuristic,” as one New York-based DJ described. While this subcultural capital defines the scene, it can also make it seem very exclusive. “The New York dance music scene can be very cliquey. There’s definitely a group of insiders, but it’s hard to understand how one becomes part of the inside group,” explained one social dancer. The subcultural capital of the scene is also achieved by demonstrating a knowledge of the history of house and techno and by modeling of politics of care: “The young people who participate[] [are] earnest about learning the history of house and techno music in the way that their generation [is] earnest about everything: in online forums and social media, they post[] reading lists, circulate[] essays such as “A Music-Lover’s Guide to Tinnitus,” and debate[] the sexism and racism of the dance-club industry” (Witt 2021: 8).

As the meeting point where the dance music scene creates subcultural capital, dance music venues, including legal nightclubs and illegal warehouse spaces, act as third places that “exist outside the home and beyond the ‘works lots’ of modern economic production. They are places where people gather primarily to enjoy each other’s company” (Oldenburg and Brissett 1982: 269). Dance music venues are places where social dancers gather to “shake off the week,” as one participant said. Two other social dancers described the experience of going out dancing as:

Going to a club is not just to drink and do drugs as most people tend to assume. A community develops around some of these venues and scenes by people drawn to the energy, music, style, sense of escape, and fellow humans who also attend. It’s only natural that by going out often that you’ll see the same people and develop a sense of community with them. For people who have just moved to a new city, this may be the only friends they have.

Going to a dance club is about finding like-minded people and sharing common interests above music but while on the dance floor. You can create connections that help support each other in both your private and professional lives.

These experiences highlight the essence of the third place, where in our increasingly individualized and atomized social world (Putnam 2000) dance clubs help individuals find communities beyond their home and workplaces with the expressed goal of social enjoyment.

Virtual Dance Communities

Given the centrality of dance music venues to the social lives and well-being of dedicated social dancers, it is no wonder that virtual dance communities emerged after the pandemic shut down in-person nightlife. Though it is important to acknowledge that illegal underground raves in New York and other cities including Berlin continued to take place throughout the pandemic and attracted a niche community of young, late teens and early twenties risk takers (Colyar 2020a), the dance community by and large carried a responsible message of “safety first” throughout the pandemic. “I was pleasantly surprised to see my community of dancers, who regularly treat their bodies poorly through the use of drugs and alcohol, put their health and the health of their community first during the pandemic,” stated one New York-based social dancer.

While virtual communities are just as real as traditional or other types of communities, “their distinctive nature consists in their ability to make communication the essential feature of belonging” (Delanty 2009: 168). As Bryan Turner argues, virtual communities can be considered ‘thin’ communities marked by a sense of community based on ephemeral realities with weak ties between strangers (2001). On the other hand, though Howard Rheingold, whose book The Virtual Community: Homesteading on the Electronic Frontier (Rheingold 1993) was the first major study of virtual community, saw a distinction between virtuality and reality, Manuel Castells in The Information Age (1999) avoids this dualism and instead understands virtual communities as being part of a real virtuality (Delanty 2009: 175). Given the ever increasing blending of our in-person and virtual lives, the distinction between our online and offline lives today is thin at best.

If dance communities embody Webber’s conception of “community without propinquity,” they are built, as Craig Calhoun notes, on a relational structure, but the Internet enables indirect relationships to proliferate. Calhoun argues that the Internet fosters “categorical” communities where internauts connect with others with similar identities (e.g., identifying as a social dancer) (Calhoun 1998). Within the web of virtual dance communities, we actually find examples of “interest” communities built on relational structures, “categorial” communities based on indirect relationships, and cross-sections of both interest and categorical communities. For example, while COVID Disco is an example of an interest community based on a relational structure of an extended network of friends and family, Club Q is an example of a categorical community that grew virally online. House of Yes stands out as an example of a virtual dance community initially formed around an existing community with a relational structure—based on its network of “House of Yes BFFs”—which grew into a hybrid community of both interest and categorical communities once their guest list went global.

Given that many people work from home, the pandemic has caused a blurring of the lines between what Ray Oldenburg distinguishes as the three places where people spend their lives: first (the home), second (the workplace), and third (the place of enjoyment) (1999). As noted above, nightclubs act as third places that are essential to the well-being of social dancers. However, during the pandemic, social dancers engaged in their third-place socialization within the confines of their first places. This might explain why, by immersing the user in another world, VR dance parties also create an experience for the social dancer that most closely mimics the feeling of being at an actual dance event. In essence, users virtually travel to a third place to engage in social dancing.

Comparing the sense of community on in-person versus virtual dancefloors

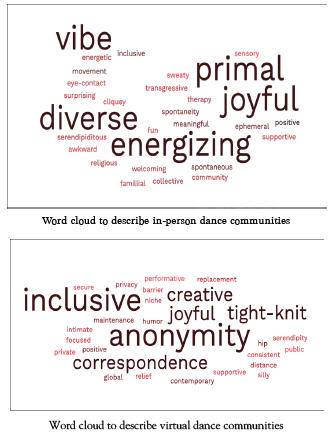

Conversations with two dozen social dancers and 30 anonymous survey respondents make one point clear: though social dancers did feel a sense of community with others at virtual dance parties, this sense of community differed fundamentally from that formed in-person. Both the conversations and the survey asked participants two questions: “If you could describe the sense of community formed on in-person dance floors in three words, what would they be?” and “If you could describe the sense of community formed at virtual dance parties in three words, what would they be?” The two sets of word clouds below, created using FreeWordCloudGenerator.com, provide a visualization of the responses, highlighting the words that were mentioned most:

These word clouds clearly demonstrate that in-person dance communities are characterized as being primal and joyful, energizing and diverse, and have a certain vibe. Conversely, virtual dance communities are defined by their anonymity, inclusiveness, creativity, written communication (correspondence), and tight-knit, joyful feeling. Through my conversations I learned that exchanging energy and communicating through body language was a defining feature of in-person dance communities. Conversely, virtual dance communities were recognized as being accepting of all, supportive, and centered around written communication.

Social dancing as a right to the Internet

In his seminal essay “The Right to the City,” Henri Lefebvre (1996) argues that the rights of city residents should be favored over those of property owners and that the use value of space should trump its exchange value, leading to autogestion (self-management) of the city. Lefebvre did not think of rights as a legal end to political struggle; instead, he understood them as a “cry that initiate[s] a radical struggle to move beyond both the state and capitalism” (Purcell 2014: 142). Thus, in proposing the right to the city, Lefebvre’s goal is to initiate a political struggle to reclaim power from the state over the governance of the city. He conceives of the urban as a rejection of and a resistance against the city life that bureaucrats, planners, and capitalists design, develop, and provide for citizens. Instead, the right to the city consists of creativity, play, and use value that is enabled by citizens’ appropriation of, and participation in, the city’s space and time (Lefebvre 1996).

Though Lefebvre’s conception of the right to the city entails moving beyond capitalism, as David Harvey (1973; 2008) and Manuel Castells (1979) point out in their critique of Lefebvre, urban space is mostly the result of capitalist production. As Harvey states: “We live, after all, in a world in which the rights of private property and the profit rate trump all other notions of rights” (2008: 23). Instead, Harvey understands the right to the city as a communal right “to change ourselves by changing the city,” which relies on the use of collective power to transform the “processes of urbanization” (2008: 23). In other words, the right to the city entails democratic control over land use as opposed to maintaining it in the hands of private or quasi-private interests.

Through the repeal of the Cabaret Law in 2017 and their support for anti-harassment safer-space policies in dance venues, the current community of social dancers in New York City were claiming social dancing as a right to the city and made their voices heard about how to use, manage, and zone urban space for social dancing (Krisel 2020). Since the right to the city entails the ability to co‑create urban space (Harvey 2008), these policy changes not only enable all social dancers to change themselves and the city by creating an environment that is safe for self-expression, but also protect the ability for all social dancers to engage in this co‑creation equally (Krisel 2020).

Could a similar idea be conceived as a right to the Internet? Parallel to Lefebvre and Harvey’s definitions of the right to the city, the right to the Internet can be formulated as: the right to realize ourselves by changing the Internet in ways that emphasize use value over exchange value of virtual space and co-create and self-manage virtual space equally. While the right to the city pertains to urban space under the jurisdiction of a state, the right to the Internet pertains to immaterial, virtual spaces that supersede traditional national borders. However, people access virtual space through digital platforms created by large technology corporations that can dictate how users engage products, subject to some degree of national regulation (e.g., Zoom does not allow nudity on their platform). Still, as demonstrated through the example of virtual dancing, subcultural Internet communities can participate in the self-management and co-creation of virtual spaces. The cases of Club Q’s “queering of Zoom” and the dance music scene within VRChat represent examples of social dancing as a right to the Internet.

Queering Zoom

Queer culture is at the root of the dance music scene. Since the arrival of disco as a musical genre in the late 60s, queer culture was a key element of the dance floor (Lawrence 2011). Nightclubs are spaces where non-straight, non-cisgendered people can express themselves freely without (or with less) fear of social or penal retribution. As Tim Lawrence argues, the New York dance music scene in the early 70s attempted to “create a democratic, cross-cultural community that was open-ended in its formation,” (2011: 233) where gathering in a nightclub was a form of resistance to homophobia, transphobia, and misogyny. In short, “queer gatherings are a rejection of queer isolation” and become an antidote to the historical societal rejection of these marginalized communities (Kornhaber 2020). By centering pleasure over productivity and mounting a resistance to discrimination, social dancing has been an essential right to the city for the queer community. However, when the pandemic shut down nightlife, it also cut off physical spaces where queer communities form, build, and grow.

Club Q has been chronicled as the largest and most popular virtual queer club (Brachman 2020; Goldfine 2020). The organizers of Club Q, who like to say “they put Zoom in drag” (Bird 2020), knew that it was important to create a replacement for in-person queer spaces. “The club tends to be one of the only safe spaces for queer people, and it was natural to adapt this world of isolation to maintain that safe space,” explained Club Q co-creator, Andrés Sierra (Goldfine 2020). Club Q co-creator Brad Allen also stated:

A lot of queer people may not have the support others do during quarantine. They may not have access to their chosen family or the spaces that make them feel at home, so this may fill that void just a bit. Clubs have always been our churches, almost spiritual in a wild effed up way, so this is just us praying at home.

Goldfine 2020

In reimagining Zoom as a queer nightlife space, the Club Q organizers used social dancing as their right to the Internet to foster encounter over isolation, favor use value over exchange, and shape virtual space in ways that reflected their inclusive values or diverse forms of expression. Though it cost money for organizers to create them (Colyar 2020b), participants were free to attend Club Q events, creating a self-managed virtual space where queers of all ages and backgrounds can congregate.

VR social dancing

Virtual reality dance spaces created on the VRChat platform allow party organizers to have full control over the look, feel, and sounds of their space. Given that VRChat is a free-to-play platform where designers can freely upload their 3D worlds and avatars, and users can engage in virtual dance without charge, it also stands as an example where users can prioritize use value over the exchange value of virtual space. In some sense, the ability to create virtual worlds within VRChat most closely mirrors Lefebvre’s utopian ideal for an urban beyond state and capitalist control of land. In VRChat, new social dancing spaces can be erected without the need for zoning approval, or transfer of property rights. The hours of operation of venues do not have to be state-approved. There are no state laws dictating a minimum age to enter the virtual dance club. These parameters can be set by the party organizers, allowing them to express their right to the Internet in self-managing and co-creating virtual space.

Conclusion: Will the future of nightlife be virtual?

Though virtual dancing existed prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the shutdown of in-person nightlife propelled its popularity as an alternative for social dancers seeking to continue dancing. This study provides a bird’s-eye view on the virtual social dancing landscape and explores the sense of community formed on virtual dance floors while comparing it to in-person dance floors. It explores the potential for, and limits to, social dancing as a right to the Internet, defined as the ability to self-manage and co-create virtual space with the goal of favoring the use value over the exchange value of virtual space while also making room to change ourselves by changing the Internet.

Is virtual dancing here to stay? Though virtual dance parties gained popularity during the pandemic and expanded in terms of scope and capabilities, the majority of social dancers who informed this study said they would not attend a virtual dance event in a post-pandemic world if they had a choice to attend one in person. Instead, virtual dancing will remain a potentially significant niche market for the following social dancers: those with physical and mental disabilities, those who may not live near urban centers with booming dance music scenes, those who live in places where the expression of their gender or sexual orientation is considered taboo and/or illegal, those who may not be able to afford in-person events, those interested in interacting with distant cultures, and/or those like caretakers who may not have the time or opportunity to go out as often. “Because of work and family circumstances, I had to move away from New York and the dance music scene. It’s really incredible that I can continue to attend live virtual dance events with DJs from all over the world, from the comfort of my basement music studio,” explained one participant.

For the social dancers tapped into the VR dance music scene, the benefits of dancing virtually from the comfort of their homes can sometimes outweigh the interest in engaging in in-person dancing. “With VR, I still scratch my dance itch without needing to plan around how I’m going to get to and from the event, the risk of paying for a party that I may not even enjoy, and the cost of paying for drinks at a party can really add up,” one VR dancer explained. In addition, the investment in VR equipment is another incentive to continue attending VR parties.

Many in-person nightclubs have caught on to the trend of virtual events and intend to provide patrons the opportunity to purchase a virtual ticket to their parties, which would grant access to a live stream of the DJ. “We are thinking about how we can bridge in-person and virtual dance parties,” said one member of the House of Yes management team. “It may just be a live stream of our DJ, but we’d like to be more creative and make those joining virtually feel like they are at the party.” The option to tune in to live streams at far-away nightclubs is attractive to many social dancers, including those who have access to local dance scenes. “Some DJs I follow never travel to the US. So I’m looking forward to being able to stream their sets live from a venue in Amsterdam or Berlin,” said one Los Angeles-based participant. Another interviewee who also moved away from a city center during the pandemic said: “Since I no longer live near my favorite venues, I’m excited to be able to host dance parties at my house while playing a live stream through my projector. Basically, I’ll bring the party to my place.”

As one social dancer stated: “The pandemic really showed us that the dance floor is wherever you create it.”

Appendices

Note

Appendices

References

- Alexander, Jade. 2020. “Club Quarantäne, The First Virtual Club to Exist.” Trendland. Retrieved August 18, 2021. On line: https://trendland.com/club-quarantane-the-first-virtual-club-to-exist/.

- Bird, Angie. 2020. Club Quarantine. Vimeo.

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1986. Distinction. London: Routledge.

- Brachman, Aurora. 2020. “Opinion : Every Night in Quarantine, I Danced With Hundreds of Strangers.” The New York Times, September 22.

- Calhoun, Craig. 1998. “Community without Propinquity Revisited: Communications Technology and the Transformation of the Urban Public Sphere.” Sociological Inquiry 68(3): 373–397.

- Castells, Manuel. 1979. The Urban Question: A Marxist Approach. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

- Castells, Manuel. 1999. The Information Age, Volumes 1-3: Economy, Society and Culture. Malden: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Colyar, Brock. 2020a. “New York Nightlife Never Stopped. It Just Moved Underground.” The Cut. Retrieved February 17, 2021. On line: https://www.thecut.com/2020/11/nyc-underground-nightlife-covid-19.html.

- Colyar, Brock. 2020b. “One Night at Zoom’s Hottest Club.” The Cut. Retrieved August 18, 2021. On line: https://www.thecut.com/2020/03/club-quarantine-is-zooms-hottest-new-queer-club.html.

- Correal, Annie. 2017. “After 91 Years, New York Will Let Its People Boogie.” The New York Times, November 6.

- Delanty, Gerard. 2009. Community: 2nd Edition. London and New York: Routledge.

- Goldfine, Jael. 2020. “How to Throw a Rave at the End of the World.” PAPER. Retrieved August 22, 2021. On line: https://www.papermag.com/club-quarantine-zoom-parties-2645599288.html?rebelltitem=24#rebelltitem24?rebelltitem=24.

- Harvey, David. 1973. Social Justice and the City. Revised edition. Athens: University of Georgia Press.

- Harvey, David. 2008. “The Right to the City.” New Left Review 53.

- Kornhaber, Spencer. 2020. “The Coronavirus Is Testing Queer Culture.” The Atlantic. Retrieved February 17, 2021. On line: https://www.theatlantic.com/culture/archive/2020/06/how-quarantine-reshaping-queer-nightlife/612865/.

- Krisel, Rebecca. 2020. “Consent-Based Social Dancing Spaces and the Right to the City.” Metropolitics, June 30, on line: https://metropolitics.org/Consent-Based-Social-Dancing-Spaces-and-the-Right-to-the-City.html

- Lawrence, Tim. 2011. “Disco and the Queering of the Dance Floor.” Cultural Studies 25(2): 230–243.

- Lefebvre, Henri. 1996. Writings on Cities. Cambridge: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Lyons, Jarret. 2018. “Council Member Rafael Espinal And Bushwick’s House Of Yes Team Up To Combat Sexual Harassment.” Bushwick Daily. Retrieved May 28, 2019. On line: https://bushwickdaily.com/bushwick/categories/music/5693-bushwick-council-member-rafael-espinal-and-bushwick-s-house-of-yes-team-up-to-combat-sexual-harassment.

- Oldenburg, Ray. 1999. The Great Good Place: Cafes, Coffee Shops, Bookstores, Bars, Hair Salons, and Other Hangouts at the Heart of a Community. 3rd edition. New York and Berkeley: Marlowe & Company.

- Oldenburg, Ray and Dennis Brissett. 1982. “The Third Place.” Qualitative Sociology 5(4): 265–284.

- Purcell, Mark. 2014. “Possible Worlds: Henri Lefebvre and the Right to the City.” Journal of Urban Affairs 36(1):141–154.

- Putnam, Robert. 2000. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- Rheingold, Howard. 1993. The Virtual Community: Homesteading on the Electronic Frontier. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

- Schmitz, Rob. 2020. “Clubbing In The Time Of COVID-19: Berlin Clubs Are Closed, So DJs Are Livestreaming.” NPR, September 18.

- Steinberg, Sophie. 2020. “Club Quarantine: A Queer Safe Haven in the Form of a Virtual Dance Party.” The Occidental. Retrieved August 18, 2021. On line: https://www.theoccidentalnews.com/culture/2020/10/13/club-quarantine-a-queer-safe-haven-in-the-form-of-a-virtual-dance-party/2901674.

- The Berlin Club Commission. 2018. Club Culture Study. Berlin: Clubcomission.

- The Mayor’s Office of Media and Entertainment. 2019. NYC’s Nightlife Economy: Impact, Assets, and Opportunities. New York: NYC Media and Entertainment.

- The Mayor’s Office of Media and Entertainment. 2021. Office of Nightlife Report: 2018-2021. New York : NYC Media and Entertainment.

- Thornton, Sarah. 1996. Club Cultures: Music, Media, and Subcultural Capital. Hanover: Wesleyan University Press.

- Turner, Bryan. 2001. “Outline of a General Theory of Cultural Citizenship.” In Nicholas Stevenson (ed.), Culture and Citizenship: 11–32. London and Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Webber, Melvin M. 1964. “The Urban Place and the Nonplace Urban Realm.” In Melvin M. Webber(ed.), Explorations into Urban Structure: 79–153. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Wheeler, Seb. 2020. “‘Coronavirus Will Never Stop the Rave’: How People Are Finding New Ways to Party Online.” Mixmag, April 9.

- Witt, Emily. 2021. “Clubbing Is a Lifeline—and It’s Back.” The New Yorker, June 24: 1–28.