Abstracts

Abstract

This paper is about the introduction and use of Multimodal Pragmatic Analysis (MPA) as a research methodology in audiovisual translation (AVT). Its aim is to show the contribution of the MPA to the analysis of film discourse in AVT with a focus on interlingual subtitling. For this purpose, the paper is divided into five sections which elaborate on the theoretical and practical aspects of the MPA methodology. Following the introduction, the second section defines the context of MPA as a new research methodology in AVT at the level of approach, design and procedure. The third section describes the theoretical base of this methodology, and the fourth examines its basic components and levels of analysis. The fifth section provides two practical examples to show how the MPA methodology operates in the analysis of speech acts appearing in the source text and the target text. Finally, the last section first discusses the advantages and disadvantages of the methodology and then concludes the paper with some suggestions for further research.

Keywords:

- multimodal pragmatic analysis,

- audiovisual translation,

- interlingual subtitling,

- film discourse,

- speech act

Résumé

L’article présente l’analyse pragmatique plurimodale (APP) comme méthode de recherche en traduction audiovisuelle (TAV). L’objectif est de montrer l’apport de l’APP à l’analyse du discours cinématographique dans le cadre de la TAV, une attention particulière étant portée au sous-titrage interlinguistique. L’article se divise en cinq sections dans lesquelles sont développés les aspects théoriques et pratiques de l’APP. Dans la deuxième section, qui suit l’introduction, l’APP est située en tant que nouvelle méthodologie de recherche en TAV. La troisième section se penche plus en détail sur ses fondements théoriques, tandis que la quatrième en décrit les composantes de base et les niveaux d’analyse. La cinquième section présente deux exemples pratiques qui montrent comment l’APP s’applique à l’analyse des actes de parole présents dans le texte de départ et dans le texte d’arrivée. Enfin, la dernière section présente les avantages et les désavantages de la méthode et se conclut par quelques suggestions pour des recherches ultérieures.

Mots-clés:

- analyse pragmatique plurimodale,

- traduction audiovisuelle,

- sous-titrage interlinguistique,

- discours cinématographique,

- acte de parole

Article body

1. Introduction

In recent years, the analysis of film discourse or film text (Baldry and Thibault 2006; Bordwell 1985; Cook 1992; Fuery 2000) has been much discussed in the area of Audiovisual Translation (AVT) with a particular focus on subtitling (Neves 2004; Pettit 2004; Remael 2004). The present paper is a step forward in that direction. It is an interim report of the key ideas developed in the original Ph.D. thesis (Mubenga 2008). Its main aim is to introduce a new research methodology known as Multimodal Pragmatic Analysis (henceforth MPA) and to show its contribution to the analysis of film discourse in AVT, focusing on interlingual subtitling. Thus, the paper is divided into five sections which elaborate on the theoretical and practical aspects of the MPA methodology.

Following this introduction, the second section sets up the context of MPA as a new research methodology in AVT. The third section describes the theoretical base of this methodology. The fourth section examines its basic components and levels of analysis. The fifth section provides two practical examples to show how the MPA methodology operates in interlingual subtitling. The sixth and last section is the conclusion. It discusses the advantages and disadvantages of this methodology for the analysis of film discourse in AVT.

2. The context of multimodal pragmatic analysis in audiovisual translation

MPA is developed in the context of Descriptive Translation Studies (DTS) as proposed by Toury (1995). It is the confluence of pragmatics (Levinson 1983) and multimodality (Kress and Van Leeuwen 2001; 2006) in doing discourse analysis (DA) in subtitling. Its innovative feature is that it retains “the text-focussed flavour of linguistic DA” (Connolly and Phillips 2005) while applying the linguistic concepts into the domain of semiotics. This means that it blends both linguistic and non-linguistic signs in the analysis of film discourse. In doing so, it adopts “a semiological focus which allows us to consider the message to be composed not only of the linguistic system, but also of other non-linguistic systems” (Mayoral, Kelly et al. 1988: 358). This has been demonstrated recently by, for instance, Chuang (2006: 375), by taking into account “all the semiotic modes represented in the film text” in subtitle translation. However, our approach is different from hers in the way in which it is conceptualised and organised internally as we shall see shortly.

As a research methodology, MPA is essentially a descriptive model that is appropriate for systematic, comparable and replicable studies as Toury (1995) has recommended. In this respect, it is characterised by its approach, design and procedure (Richards and Rodgers 1985), that facilitate not only the description and comparison of the source text (ST) and the target text (TT) but also the location of these two texts in their respective context of culture. The description, comparison and location of both the ST and the TT in their sociocultural environment produce profiles of linguistic features which in turn contribute to identifying translation shifts and to deducing the translator’s decisions made during the process of film translation.

At the level of approach, the model is pragmatic in so far as it focuses mainly on speech acts (Searle 1969) or speech functions (Halliday 2004) in film discourse. It thus considers the speech act as the semantic unit of communication and the clause, in Halliday’s (2004) sense, as the corresponding grammatical unit of analysis in film subtitling. Although speech acts are universal but realised differently across languages, it is assumed that there is always functional equivalence (De Waard and Nida 1986) between the speech acts which are translated from the source language (SL) to the target language (TL) or from the ST to the TT. Functional equivalence is thus one basic condition for the pragmatic approach to be operational in film translation. Further details on the pragmatic approach adopted in this paper can be found in Emery (2004).

At the level of design, the model is multimodal since it takes into account a wide variety of semiotic codes that appear in the acoustic and visual channels of a film. These semiotic codes have the potential to make meaning in film. They greatly contribute to the syntax of film language and the process of film translation (Chaume 2004). However, it is agreed with Chuang (2006: 375-376) that “while translating the meaning potentials of the [semiotic] modes from the source text into the target text, certain meanings may lose or gain in different aspects,” thereby resulting in linguistic differences between the ST and the TT. Different taxonomies of these semiotic codes have been elaborated by, for example, Chaume (2004), Delabatista (1989) and Monaco (1981). They can thus be used profitably as checklists for a systematic analysis of the verbal, the acoustic and the visual elements in the film.

Finally, at the level of procedure, the model is multi-procedural as it includes a set of seven methodological procedures developed for conducting research in AVT. These methodological procedures are primarily developed for film subtitling but should not be limited to it. They can be extended to other AVT modes such as print advertising, TV commercials, cartoons and soap operas. They are based on the propositions made by Toury (1995) and Labrador de la Cruz (2004), and are formalised as follows:

collecting and selecting the basic data (speech acts) from the films;

delimiting the working corpus to make a representative sample of the data;

observing the collected data to check the level of correspondence between the ST and the TT data as well as to identify their types and frequencies;

juxtaposing the ST – TT data to categorise them in form-function relationships;

analysing the ST – TT data systematically to discover the similarities/differences as well as the factors/strategies used in subtitling;

locating the ST – TT data in their context of culture and evaluating the research findings;

drawing implications and/or generalisations for theory building in AVT.

In order to analyse the ST – TT data systematically, MPA uses Halliday’s (2004) Systemic Functional Grammar (henceforth SFG) as a tool that is appropriate and necessary for (contrastive) discourse analysis in AVT. This tool makes the difference between MPA and both Chuang’s (2006) model and other theories developed or suggested in AVT research (Chaume 2002; Díaz Cintas 2004). It has a solid theoretical base that is also adopted for the MPA methodology.

3. The theoretical base of the MPA methodology

Since film is a semiotic construct, the MPA methodology adopts Halliday’s (1978; 1994) systemic grammatics and its metafunctional semiotic theory. Our preference for Halliday’s systemic functional theory rather than polysystem theory is that the latter is, according to Díaz Cintas (2004: 25), “too limited to films and neglects other products of the audiovisual world that are also translated such as TV series, documentaries, cartoons, soap operas, commercials or corporate videos” while the former is applicable without any distinction to any text in any AVT mode and in any context of culture. The hypothesis underlying this systemic functional theory is that there are three metafunctions (Halliday 1978; 1994) or strands of meaning which are both interconnected and operate simultaneously in the semantic system or “discourse-semantics” (Eggins 1994: 81-82) of any language. These three metafunctions are: (1) the ideational, (2) the interpersonal, and (3) the textual.

The ideational metafunction relates to the clause when it assumes its meaning as “representation” (Halliday 2004: 168). It is the content function of language through which the world is conceptualised or brought into being linguistically. This function is sometimes divided into two metafunctions: (1) the experiential that construes human experience and (2) the logical that provides the resources of (commonsense) logic. It is associated with the field of discourse in the register or context of situation and with the transitivity structure in the lexicogrammar.

The interpersonal metafunction refers to the clause when it assumes its meaning as “exchange” (Halliday 2004: 106). It is the participatory function of language through which both speaker and hearer bring themselves into being linguistically by using speech acts. This function is connected with the tenor of discourse in the register and with the mood and/or modality structure in the lexicogrammar.

The textual metafunction concerns the clause when it has its meaning as “message” (Halliday 2004: 64). It is the enabling and relevance function of language that brings texts or communicative events into being linguistically and through which what is said or written is seen as relevant. This function is linked to the mode of discourse in the register and to both the thematic structure and patterns of cohesion in the lexicogrammar. In spoken language, the thematic structure is supplemented by the information structure which is realised through intonation.

From the translational point of view, the metafunctional semiotic theory is advantageous in that it shows us the connection between the metafunctional configurations, the register variables and the lexicogrammatical patterns (including the patterns of cohesion). The latter may serve as the basic linguistic resources for the analysis of translation shifts in film subtitling. The researcher can analyse systematically and contrastively the patterns of transitivity, mood, theme/rheme and cohesion as they are used in both the ST and the TT. This systematic and contrastive analysis will enable him or her not only to find out the differences and similarities between the ST and the TT but also to discover what factors and strategies are used by the translator. Such a kind of analysis can be replicable for the pairs of ST-TT segments which are under investigation.

Another advantage is that, by using a bottom-up approach in Halliday’s (2004) systemic functional model of discourse analysis, the lexicogrammatical patterns may be related to the register variables of field, tenor and mode through the ideational, interpersonal and textual metafunctions. From the register, which is the context of situation, they may be ultimately connected with the generic structure or genre which is the context of culture (Eggins 1994; Munday 2001). This bottom-up approach facilitates the location of the research findings to their respective context of culture.

The last advantage of the metafunctional semiotic theory is that it can be extended to other semiotic modes (Kress and Van Leeuwen 2006; Van Leeuwen 1999) of communication which are used in subtitling, namely, image, music and other sounds. The complementary role of these semiotic modes in the decoding of messages in constrained translation is discussed by Mayoral et al. (1988; see also Pottier 1987 for the combination of semiotic modes in decoding advertising messages).

In this respect, the semiotics of visual imagery by Kress and Van Leeuwen (2006) and that of sound design by Van Leeuwen (1999) are useful tools for the description of image and sound not only in film subtitling but also in other AVT modes. They provide the semiotic resources that can be used in the pragmatic analysis of any multimodal discourse to see how the verbal, the visual and the acoustic elements are integrated. This requires the MPA methodology to have a set of appropriate components and levels of analysis in its base.

4. Components and levels of analysis in the MPA methodology

The MPA methodology consists of three basic components and three levels of analysis in each component. As far as the components are concerned, we have (1) the functional, (2) the semiotic, and (3) the cognitive. The functional component is derived from Halliday’s (2004) Functional Grammar. It is mainly concerned with the analysis of the verbal element in the film. The semiotic component is taken from Kress and Van Leeuwen’s (2006) Grammar of Visual Design. It deals with the analysis of the visual element in the film frame. Finally, the cognitive component is based on Cognitive Linguistics (Fawcett 1980), Cognitive Psychology (De Vega 1984) and Frame Semantics (Fillmore 1982; Rojo López 2002). It involves the activation of the knowledge structures in the long-term memory (LTM), the making of inferences at the clause level in the exchange structure, the integration of the verbal, visual and acoustic elements, and the connection of this integrated information with the world knowledge in the context of culture.

As for the levels of analysis, we have (1) the ideational, (2) the interpersonal, and (3) the textual. These levels correspond to Halliday’s (1978; 2004) three metafunctions (Section 2). In the functional component, the ideational level is concerned with the patterns of transitivity, the interpersonal level with the patterns of mood, and the textual level with the thematic structure and cohesion. In the semiotic component, the ideational level focuses on the patterns of representation, the interpersonal level on the patterns of interaction, and the textual level on the patterns of composition. Finally, in the cognitive component, the ideational level deals with the visual, the situational and the institutional frames, the interpersonal level with the social and generic frames, and the textual level with the text-type frames.

The semiotic resources of sound that include perspective, time and rhythm, interacting sounds, melody, voice quality and timbre, and modality can be handled in the functional and cognitive components. They are not structured along the metafunctional lines as the semiotic resources of language and visual imagery because of the nature of their semiotic mode (Van Leeuwen 1999). Thus, they can be analysed at any level especially at the interpersonal and textual levels. In our analysis, emphasis is placed on intonation which has a pragmatic function in discourse and on music and sound effects which accompany the film dialogue.

It remains to say that the aforementioned components and levels of analysis constitute the different phases that are necessary for the application of the MPA methodology to the analysis of film discourse in subtitling. Although the functional and semiotic components are separated theoretically, in practice they work simultaneously. This interaction is realised in the cognitive component which acts as the black box or mind of the methodology. An attempt to illustrate how the MPA methodology works is made in the next section to which we now turn.

5. Applications of the MPA methodology to film discourse in subtitling

The two examples that serve as models are taken from the French feature film Pierrot le Fou by Jean-Luc Godard (1965).[1] They represent two different speech acts. The first example is a request and the second one an apology. They appear in their context of use in (1) and (2) below. The subtitles are in italics and the examples are underlined for consideration in the three phases of the MPA methodology which are the functional grammatical analysis, the visual semiotic analysis, and the cognitive frame analysis. Since film is a visual medium, priority is given to the visual semiotic analysis followed by the functional grammatical analysis and the cognitive frame analysis. In systemic work, descriptive terms such as Subject, Predicator, Actor, Reacter, Theme, Rheme, Given and New are in capital (Halliday 2004; Kress and Van Leeuwen 2006). This practice is also maintained here.

Although there are different narrative techniques in the analysis and appreciation of films (Bone and Johnson 1991; Bordwell 1985; Smith 2003), use is made of Kress and Van Leeuwen’s (2006) framework which is developed in the context of metafunctional semiotic theory and is close to Halliday’s (2004) approach adopted here. A great deal of emphasis is laid on colour which is a semiotic mode communicating feelings of emotion (Bone and Johnson 1991) to the viewer and helping not only to make inferences but also to define the characters in the film. Further details on colour can be found in, for example, Kalmus (2006), Koller (2008) and Kress and Van Leeuwen (2002; 2006).

5.1. The visual semiotic analysis of the request and the apology

5.1.1. The ideational level

The moving image of example (1) shows us Marianne and Ferdinand seated beside the petrol pump of a TOTAL garage, which is a French gasoline business. Marianne is looking around with an air of expectancy. She is wearing an orange T-shirt, a pair of black and red check trousers, a grey jacket, and a camouflage baseball cap. Ferdinand is smoking a cigarette and reading a comic book entitled L’ÉPATANT, La bande des Pieds nickelés. “L’Épatant” may be translated into English as “The Wonderful” or “The Stunning Chap” and in fact is the name of the journal in which les Pieds nickelés, a famous comic strip from the beginning of the 20th century, was first published in 1908 (literally, “the nickeled feet,” a metaphor for very lazy people). Ferdinand is wearing a grey stetson, a blue shirt, a black tie and a black suit. When Marianne takes the lit cigarette from Ferdinand’s lips, a car horn blares at the garage. Marianne looks at the car. Very excited, she requests Pierrot to have a look at it, which he does after one minute or so and then he continues reading his comic book. In all this, Marianne is the Actor, Ferdinand, the Reacter, and the car, the Goal.

In example (2), the moving image shows us first the patio of a cottage near the sea where we can see Marianne lying on a sort of deck chair (she has been brought there by Ferdinand – he just killed her in the shoot-out). She is wearing an orange skirt and a blouse that seems grey but that will appear to be white striped with black or dark blue one minute later. Then, Ferdinand is taking her in his arms to bring her on a small bed in the bedroom. After laying Marianne on the bed, he sits beside her. He is wearing a pair of black trousers, an orange pullover and a grey jacket. In the room, there is a bedside lamp on a small table. On top of the bed, there is a picture of a woman in a frame hung on the wall. The bed is covered with blue sheets and the walls are painted in pale yellow. Marianne tosses restlessly on the bed and is at the point of death when she apologises to Ferdinand (she keeps calling him “Pierrot”). She is bleeding from the nose and on the face, turns her head to the left and to the right, and then dies with her eyes wide open. Here, Marianne is the Actor and Ferdinand/Pierrot, the Reacter.

5.1.2. The interpersonal level

In the moving image of example (1), Marianne and Ferdinand are shown in a medium shot (MS) which changes into a medium long shot (MLS) as the camera is moving away from the viewer. They are in focus and sitting at a close social distance. This creates an intimate relationship between them. Since they do not look directly at the viewer, they are on the offer. However, the shot seems to be taken at eye level and at a frontal angle, thereby suggesting some kind of involvement between the viewer, Marianne and Ferdinand with no power difference between the three of them. There is also some kind of relationship between the way Ferdinand is dressed and the title of the comic book he is reading as the camera focuses on it.

Furthermore, the way Marianne is dressed, her hand gestures, her gaze at the car and her smile create an exciting mood in the film frame, the mood of someone who has a spirit of adventure while Ferdinand remains calm and serene. The orange colour of her T-shirt suggests that she is vibrant and full of vigour but may turn angry easily. On the contrary, the grey colour of Ferdinand’s stetson implies that he is indifferent and that something is worrying him or hanging over his head like a dark cloud. The scene is shot during the day as we see sunlight, and the image is well exposed.

In the moving image of example (2) (underlined part of the dialogue), Marianne appears in a medium long shot (MLS) as she is lying on the bed while Pierrot is shown in a medium shot (MS), seated on the bed with his back to the camera. Both of them are on the offer since they do not look directly at the viewer. The latter is offered the possibility of looking at all the details in the bedroom and outside through the open door. Marianne and Pierrot are in the foreground while the garden and the landscape are in the background. We are given a panoramic view of what is going on in a sequence of related film frames. Pierrot is in a dominant position as he is looking down at Marianne who is in bed tossing restlessly, crossing her arms and breathing her last. Finally, we see Pierrot going to make a phone call, painting his face in blue, taking dynamite, and ultimately killing himself.

Colour plays an important role in this moving image. For example, the orange colour on Pierrot’s pullover and Marianne’s skirt implies that they complement each other. They share the same feelings. They are vibrant, creative and emotionally stable. Nonetheless, they can become extremely angry. Marianne’s white blouse striped with black suggests that she wants peace and forgiveness from Ferdinand for having cheated on him. Pierrot’s black trousers suggest that he has been in the dark and unemotional while shooting at Marianne. His grey jacket also signals that he has been worried, lost and depressed. This depression leads him to commit suicide. Finally, the yellow walls and the blue sheets on the bed imply that the country cottage is an inspirational, peaceful place that can soothe the agitated conditions of the mind, body and soul such as those of Marianne who is on the verge of dying.

5.1.3. The textual level

The moving image of example (1) shows us Marianne and Ferdinand foregrounded in the centre of the film frame with the petrol pump station in the background. Marianne is on the left and Ferdinand on the right. She may be associated with Given information that the viewer already knows about the car from having heard the horn and the sound of the car engine. Ferdinand may be associated with New information that the viewer does not know and that brings some kind of suspense. The viewer’s reading paths are guided by their gaze, Marianne’s gaze at Pierrot and at the car, Pierrot’s gaze at the car and at the comic book. All these camera movements from Marianne to Pierrot and from them to the car serve as vectors which create visual coherence in the film frame. It is as if both of them were requesting the viewer to look at the car, and this is what the viewer does when the camera shows the car entering the petrol pump station.

The moving image of example (2) shows us in a medium long shot and then in a medium shot Pierrot on the left and Marianne on the right. Pierrot can be associated with Given information since he is the one who shot Marianne. Marianne can be associated with New information as she is struggling with death and asking for forgiveness. The camera has remained focused on both of them until Marianne dies. Then, there is a close-up (CU) showing us Marianne’s face with the eyes wide open and the nose bleeding. The film frame is composed mainly of Marianne’s agitated movements before she dies. Her death may be considered as the new information that is presented to the viewer. It justifies the reason for her apologising to Ferdinand. Visual coherence is thus created by the camera movements which guide the viewer’s eye from the medium long shot through the medium shot to the close-up.

5.2. The functional grammatical analysis of the request and the apology

5.2.1. The ideational level

The transitivity analysis of the request in example (1) shows that the spoken utterance in French and the subtitled sentence in English are similar syntactically and semantically. Syntactically, the two clauses are in the active voice and in the imperative form. They have the same participants and the same order of elements in that the main verb is followed by the vocative and the complement. Semantically, both clauses have the same meaning as they encode the same main Event which is to direct the eyes to the relevant object. Since the lexical verb requires some kind of physiological behaviour from the addressee in the two clauses, the latter are referred to as behavioural clauses. They encode the same effective behavioural Process whose transitivity structure can be represented as in Table 1 and Table 2 for French and English respectively.

Table 1

The transitivity structure of the French imperative request

Table 2

The transitivity structure of the English imperative request

Table 1 and Table 2 show that the Behaver is not stated explicitly in both clauses which are in the imperative. However, it is understood in the context that it is Toi in French and You in English. This explains why it is written in parentheses. The angled brackets indicate that the Vocative is enclosed between the Process and the Phenomenon. The Process is a lexical verb that requires a sensory input from the addressee in both clauses while the Phenomenon/Range specifies the domain of this Process. Thus, it is clear from the above analysis that there is no translation shift in the transitivity structure since the latter is similar in both the ST and the TT.

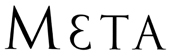

The transitivity analysis of the apology in example (2) reveals that the French clause consists of the verbal Process with the Addressee and Verbiage (Caffarel 2006: 77) whereas its English translation is composed of the emotive mental Process with the Attribute. This suggests that the two clauses have encoded different domains of experience. However, despite this structural difference, the meaning is almost the same in both cases since the French expression demander pardon à quelqu’un is an equivalent of the English verb to forgive. This transitivity structure of the two clauses can be represented as in Table 3 and Table 4 below.

Table 3

The transitivity structure of the French declarative apology

Table 4

The transitivity structure of the English imperative Apology

Although both clauses are in the active voice in the above tables, they are grammatically different in the sense that the French clause is a declarative and the English clause an imperative. Thus, the Sayer is mentioned in French and the Senser not mentioned in English but understood in the context that it is You. This contextual Senser and the Addressee refer to the Vocative which is not handled in the transitivity analysis. Besides, in Table 4, there is an addition of the Clause Adjunct. The latter is used to soften the imperative clause (Huddleston and Pullum 2002). Grammatically, this Clause Adjunct stands for the personal use of the conditional clause if you please. Semantically, it is similar to the adverb kindly. In this respect, it may be regarded as a special category of the Comment Adjuncts elaborated by Halliday (2004). In sum, the transitivity analysis reveals that there are some shifts in the translation of the ST into the TT. The Sayer in French becomes the Attribute in English. The Addressee changes into the Senser which is omitted in the bare imperative. The verbal Process and its Verbiage change into the emotive mental Process.

5.2.2. The interpersonal level

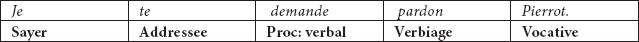

The analysis of the interpersonal structure of example (1) reveals some noticeable differences in the Negotiatory structure (Caffarel 2006) in French and the Mood structure in English. This is shown in Table 5 and Table 6 below for French and English respectively.

Table 5

The interpersonal structure of the French imperative request

Table 6

The interpersonal structure of the English imperative request

In Table 5, the Negotiatory structure consists of the Negotiator and the Remainder. While the Negotiator is made up of the Predicator (P) and the Vocative (V), the Remainder contains the Complement (C) only. In contrast, in Table 6, the Mood structure is composed only of the Residue. The latter includes the Predicator and the Complement whereas the Vocative, which assumes the function of Negotiator, falls outside the scope of the Residue.

Despite the above differences, the most important similarity is that in both clauses the Vocative establishes the interpersonal relationship between the speaker and the hearer. The use of the nickname “Pierrot” by Marianne consolidates this relationship of closeness and intimacy between her and Ferdinand. In addition to this, the imperative in the second person singular in French is a marker of informality which is lost in English.

The analysis of the interpersonal structure of example (2) shows that there are some major changes in the Negotiatory structure in French and the Mood structure in English. This is illustrated below in Table 7 and Table 8, respectively for French and English.

Table 7

The interpersonal structure of the French imperative apology

Table 8

The interpersonal structure of the English imperative apology

In the above tables, the abbreviations S-clitic stands for Subject clitic, C-clitic for Complement clitic (Caffarel 2006: 131), F for Finite, P for Predicator, Cdo for Direct Object Complement, C-Adjunct for Clause Adjunct, and C for Complement. It is clear that the constituency of the Negotiator is different from that of the Mood. Likewise, the constituency of the Remainder is different from that of the Residue. While the Negotiator consists of the Subject clitic, the Complement clitic and the Finite/Predicator, the Mood is composed of the Clause Adjunct only. On the contrary, the Remainder comprises the Direct Object Complement only whereas the Residue includes the Predicator and the Complement.

The above changes are due to the syntax of the two clauses. They suggest that the same apology is expressed in different ways in the ST and the TT. While French uses the C-clitic in the second person singular to indicate familiarity between speaker and hearer, this marker is lost but replaced by the softener to indicate politeness in English. The linguistic choices are different in both languages but the speech act of apology is maintained. Finally, the Vocative as part of the Negotiatory and Mood structures falls outside the scope of both the Negotiator and the Mood in these clauses. However, this same Vocative is used to catch the addressee’s attention and thus establish the relationship of intimacy between the speaker (Marianne) and the hearer (Ferdinand).

5.2.3. The textual level

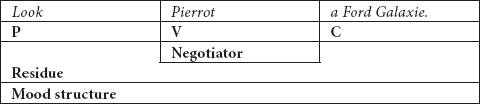

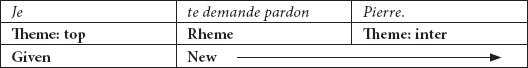

The analysis of both the thematic structure and the information structure of example (1) indicates that the French clause and its English translation are similar. These clauses are represented below in Table 9 and Table 10 for French and English respectively.

Table 9

The thematic and information structures of the French imperative request

Table 10

The thematic and information structures of the French imperative request

In Table 9 and Table 10, the Theme includes the topical Theme and the interpersonal Theme. The Rheme involves only the remainder of the clause. However, the information structure consists of only new information since the two clauses are in the imperative and the opening of the exchange of information between the speaker and the hearer. In this case, the speaker is bringing news that the hearer does not know. She wants him to direct his eyes to the car. The use of the bare imperative verb as the topical or experiential Theme in the initial position emphasizes the urgency of the message.

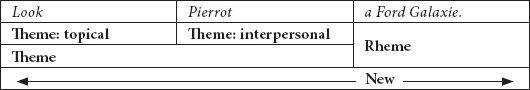

The analysis of both the thematic structure and the information structure of example (2) shows that there are some differences in the Theme-Rheme arrangement in French and in English. Table 11 and Table 12 below capture these differences.

Table 11

The thematic and information structures of the French imperative apology

Table 12

The thematic and information structures of the English imperative apology

It appears in the above figures that the constituency of the Theme and the Rheme is different in the ST and the TT. Concerning the Theme, the French clause consists of two Themes. On the one hand, we have the Subject-clitic which is the topical Theme in the initial position of the clause (Caffarel 2006). On the other hand, we have the Vocative which by itself assumes the function of interpersonal Theme in the end position of the clause. By contrast, the English clause is characterised by three Themes, the C-Adjunct and the Vocative are two interpersonal Themes, one in the initial position and the other in the final position of the clause. The Predicator/Process assumes by itself the function of topical or experiential Theme. Finally, the addition of the C-Adjunct as interpersonal Theme in English is another difference that characterises the thematic structure of this clause.

Regarding the Rheme, the French clause and the English translation consist of one Rheme. However, the difference lies in the constituency of this Rheme. While in French the Rheme consists of a Complement clitic, the Finite/Predicator and the Direct Object Complement, in English it is an object personal pronoun referring to the speaker. These differences in the Theme and the Rheme are related to the linguistic choices made by the speaker and the translator in the lexicogrammar of the SL and the TL. These linguistic choices are syntactic and lexical. They depend on the nature of the verb used in the ST and the TT. In French, demander pardon à quelqu’un includes two complements, one direct and another indirect. In English, to forgive someone requires only direct object complement.

At this stage, it should be argued that there are not specific changes or shifts that may jeopardise the meaning of the request in example (1) when it is translated from French into English. Apart from the minor structural changes attested at the interpersonal level of analysis, the behavioural Process is the same in the ST and the TT at the ideational level. Likewise, the thematic and information structures are similar in French and English at the textual level. In contrast, in example (2), there are more differences than similarities between the ST and the TT at the ideational, interpersonal and textual levels. Despite these lexicogrammatical differences, the meaning is still the same since the same speech act of apology is maintained in both the ST and the TT. This leads to the next and last phase.

5.3. The cognitive frame analysis of the request and the apology

5.3.1. The ideational level

The analysis of example (1) reveals that there are two lexical items which can be considered from the sociocultural point of view. These lexical items are Pierrot and Ford Galaxie. Pierrot is a diminutive of the French first name Pierre. It recalls the term pierre, whose meaning is ‘stone.’ Since names are often related to one’s personality and destiny and have social functions (Anderson 2007: 99-106), this suggests with reference to the meaning of his name that Pierrot is a strong man but hard to understand because of his changing temperament. He is also patient, intelligent, elegant, reliable, romantic, open but sometimes timid. These attributes are this researcher’s psychological reaction to what Pierrot is doing in the film. They are based on each letter composing the name Pierrot. The use of this name as a cultural borrowing in English reveals to us the influence of the SL on the TL.

By contrast, the proper name Ford Galaxie shows us the influence of the TL, and particularly American English, on the SL. It also tells us that the product and the name are fully integrated in the SL-TL society and that both languages use the same means of transport as one of the basic human needs in an industrialised world. By saying the utterance, the speaker believes that the hearer knows that a Ford Galaxie is a model of American luxury cars and that he will have a look at the car which they need to continue their journey across the country. The verbs regarde and look are appropriate to the SL and TL culture.

The analysis of example (2) focuses on the clause Je te demande pardon and its translation equivalent forgive me on the one hand and on the cultural borrowing of Pierrot on the other. The clause Je te demande pardon is common to French native speakers and the clause Please forgive me is common to English native speakers as well. It is likely that the shortness of the English clause results from the constraints imposed upon the translator by the subtitling process, although “I beg your pardon” is formal and express polite apology (which is not the case of “Je te demande pardon”).

5.3.2. The interpersonal level

The analysis of example (1) shows that the French utterance and its English translation have the illocutionary force of direct requests. They are informal because of the presence of the nickname Pierrot which implies a certain familiarity, intimacy and solidarity between the speaker and the hearer. In French, the imperative in second person singular is another feature of informal language which is not represented in English. However, despite the imperative request, the speaker has no power over the hearer. They are both of equal social status since they are lovers. This means that the scale of power dynamics and social distance is small between speaker and addressee. As participants in the dialogue, Marianne is the speaker and Pierrot the addressee. They are French citizens, speak French and understand each other quite well.

The analysis of example (2) reveals that the French utterance and its English translation have the illocutionary force of direct apologies. The use of the Complement clitic te and the nickname Pierrot in French make the apology informal. Likewise, the use of the same French nickname Pierrot in English renders the apology informal. This again suggests that the scale of power dynamics and social distance between speaker and hearer is small. The addition of please in English reinforces the explicit illocutionary force indicating device (IFID) in Levinson’s own terminology (1983: 238). Although the speaker requests forgiveness directly from the hearer, this forgiveness is not granted since it is too late for the hearer to do so. At last, the participants in the dialogue are Marianne, the speaker, and Ferdinand, the hearer.

5.3.3. The textual level

It should be noted here that there are different types of multimodal transcription in the literature (Baldry and Thibault 2006; Besacier 2006; Taylor 2003; Thibault 2000; Van Leeuwen 2005). Table 13 as well as Table 14 are adapted from Van Leeuwen’s (2005) model of transcription and were modified to suit our purposes. In the two tables, the first column describes the moving image. The second column includes the French dialogue and the back-translation, the third column the English subtitle, and the fourth column the sound and sound effects. The row at the bottom summarises the relation between speech, text and image. The abbreviations MS, MLS, CU and SFX stand for medium shot, medium long shot, close-up and sound effects respectively. The arrow in Table 13 indicates that there is a shift from the medium shot to the medium long shot.

In example (1), the French utterance and its English translation are the opening of the dialogue between Marianne and Pierrot. They are the first turn of speaking for Marianne and the first part requesting an action from Pierrot. The second part to this request is the action of looking at the car. This action is “dispreferred” (Levinson 1983: 307) since there has been a delay of one minute or so before looking at the car. That is to say, Pierrot first rejected Marianne’s request by rectifying his name as Ferdinand. Then, he had a quick look at the car before accepting and giving his comment on it. Thus, coherence in the dialogue is achieved by the conventional sequence of request – rejection + acceptance + comment or explanation. The integration of all the information in example (1) at the ideational, interpersonal and textual levels is shown in Table 13.

Table 13

The cognitive frame analysis of the request in example (1)

In example (2), the French utterance and its English translation are also the opening of the dialogue between Marianne and Ferdinand in the bedroom. They are the first part of an adjacency pair in the second exchange in which Marianne apologises to Ferdinand for having run away with another man. The second part of this adjacency pair is a rejection of the apology by Ferdinand. This rejection is both expected and “preferred” (Levinson 1983: 307) in the present context. It is expected in the sense that Ferdinand is angry with Marianne for having cheated on him. It is preferred since it is said bluntly and spontaneously without any delay. Thus, coherence in this dialogue is achieved through the conventional sequence of apology – (rejection + account) that characterises the discourse structure. The integration of all the information in example (2) at the ideational, interpersonal and textual levels is shown in Table 14.

Table 14

The cognitive frame analysis of the apology in example (2)

6. Advantages and disadvantages of the MPA methodology

At this stage, it may be argued that the analysis of the request in example (1) and the apology in example (2) has provided us with the visual, functional and cognitive information which we need to understand the two speech acts and locate them in their context of culture. Visually, the moving image has revealed to us the nonverbal aspects which clarify the meaning of the request and the apology in context. Functionally, the request is realised in the same way in the ST and the TT while the apology is realised differently with an addition of a softener. Cognitively, the integration of the linguistic and non-linguistic information has allowed us to contextualise both the spoken utterance and the subtitled sentence of the two speech acts in their respective sociocultural environment. Particular emphasis has been put on the lexical verb, cultural borrowing, personal names, and the scale of power dynamics and social distance.

On the basis of our analysis, it may be argued that the Multimodal Pragmatic Analysis of film discourse in AVT is advantageous for various reasons. First, it allows us to carry out successively the visual, functional and cognitive analysis of film discourse both at the ideational, interpersonal and textual levels and at the clause level. Second, this analysis can be carried out before or after the translation has taken place. In the present case, the analysis has been done after the translation in order to discover the translation shifts and the impact of the image on film subtitling. In this respect, it should be argued that the image has an impact on film translation since it complements and/or clarifies the meaning of the speech act in the frame. Finally, it shows us that the translator relies on the speech act and its nucleus which is the verb to keep the meaning in the ST and the TT. The verb may be realised in the same way as in the case of the speech act of request or in different ways as in the case of the speech act of apology. In the latter case, the translator also adds a softener as a strategy for strengthening the meaning of the verb.

However, it should be mentioned that the application of the MPA methodology to the analysis of film discourse is long, tedious and time consuming since it has to be carried out systematically at three levels for the different components. The two examples that have been used seem to be simple since there is a match between the ST and the TT to show how the methodology works. More examples raising a wide range of linguistic problems in subtitle translation can be found in Mubenga (2008). One way out of these problems is to be familiar with SFG for the SL and the TL. Another way that is worth trying in the future is to incorporate the techniques of corpus linguistics into the MPA methodology (Baker 1993; Laviosa 1998). Thus, instead of analysing the data manually as is the case now, this can be done electronically using Computer-Assisted Translation (CAT) techniques for a large sample of data from the films.

Finally, we do not claim that we are the first to have introduced the multimodal approach in interlingual subtitling (Remael 2001) but we have shown clearly how MPA should be carried out. Further research must seek to apply the methodology and the procedures outlined in this paper to other modes of audiovisual translation.

Appendices

Note

-

[1]

Pierrot le Fou (1965): Directed by Jean-Luc Godard. The Criterion Collection. Janus Film, 2007.

References

- Anderson, John M. (2007): The Grammar of Names. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Baker, Mona (1993): Corpus Linguistics and Translation Studies: Implications and Applications. In: Mona Baker, Francis Gill and Elena Tognini-Bonelli, eds. Text and Technology: In Honour of John Sinclair. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 233-250.

- Baldry, Anthony and Thibault, Paul J. (2006): Multimodal Transcription and Text Analysis: A multimedia toolkit and coursebook. London: Equinox.

- Besacier, Laurent (2006): Transcription enrichie de documents dans un monde multilingue et multimodal, Visited on March 4th, 2008,<http://www.afcp-parole.org/doc/theses/theseLB07.pdf>.

- Bone, Jan and Johnson, Ron (1991): Understanding the Film: An Introduction to Film Appreciation. Lincolnwood: National Textbook Company.

- Bordwell, David (1985): Narration in the Fiction Film. London: Routledge.

- Caffarel, Alice (2006): A Systemic Functional Grammar of French: From Grammar to Discourse. London: Continuum.

- Chaume Varela, Frederic (2002): Models of Research in Audiovisual Translation. Babel. 43(1):1-13.

- Chaume, Frederic (2004): Film Studies and Translation Studies: Two Disciplines at Stake in Audiovisual Translation. Meta. 49(1):12-24.

- Chuang, Ying-Ting (2006): Studying subtitle translation from a multi-modal approach. Babel. 52(4):372-383.

- Connolly, John H. and Phillips, Iain W. (2005): On the Analysis of Multimodal Documents at the Level of Pragmatics. Visited on August 18th, 2005,<http://www.orgsem.org/papers/01.pdf>.

- Cook, Guy (1992): The Discourse of Advertising. London: Routledge.

- Delabatista, Dirk (1989): Translation and Mass-Communication: Film and TV Translation as Evidence of Cultural Dynamics. Babel. 35(4):193-218.

- De Vega, Manuel (1984): Introducción a la Psicologia Cognitiva. Madrid: Alianza.

- de Waard, Jan and Nida, Eugene A. (1986): From One Language to Another: Functional Equivalence in Bible Translating. Nashville: T. Nelson.

- Díaz Cintas, Jorge (2004): In search of a theoretical framework for the study of audiovisual translation. In: Pilar Orero, ed. Topics in Audiovisual Translation. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 21-34.

- Eggins, Suzanne (1994): An Introduction to Systemic Functional Linguistics. London: Pinter.

- Emery, Peter G. (2004): Translation, Equivalence and Fidelity: A Pragmatic Approach. Babel. 50(2):143-167.

- Fawcett, Robin P. (1980): Cognitive Linguistics and Social Interaction: Towards an integrated model of a systemic functional grammar and the other components of a communicating mind. Heidelberg: Groos.

- Fillmore, Charles J. (1982): Frame Semantics. In: Ik-Hwan Lee, ed. Linguistics in the Morning Calm. Seoul: Hanshin, 111-138.

- Fuery, Patrick (2000): New Developments in Film Theory. New York: St Martin’s Press.

- Halliday, M.A.K. (1978): Language as Social Semiotic: The Social Interpretation of Language and Meaning. London: Edward Arnold.

- Halliday, M.A.K. (1994): Systemic Theory. In: R.E. Asher and J.M.Y. Simpson, eds. The Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics. Vol. 8. Oxford: Pergamon Press, 4505-4508.

- Halliday, M.A.K. (2004): An Introduction to Functional Grammar. London: Arnold.

- Huddleston, Rodney and Pullum, Geoffrey K. (2002): The Cambridge Grammar of the English Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kalmus, Nathalie M. (2006): Color Consciousness. In: A. Dalle Valle and B. Price, eds. Color, The Film Reader. New York: Routledge, 24-29.

- Koller, Veronika (2008): ‘Not just a colour’: Pink as a Gender and Sexuality Marker in Visual Communication. Visual Communication. 7(4): 395-423.

- Kress, Gunther and van Leeuwen, Theo (2001): Multimodal Discourse: The Modes and Media of Contemporary Communication. London: Arnold.

- Kress, Gunther and van Leeuwen, Theo (2002): Colour as a Semiotic Mode: Notes for a Grammar of Colour. Visual Communication. 1(3): 343-368.

- Kress, Gunther and van Leeuwen, Theo (2006): Reading Images: The Grammar of Visual Design. London: Routledge.

- Labrador de la cruz, Belén (2004): A Methodological Proposal for the Study of Semantic Functions across Languages. Meta. 49(2):360-380.

- Laviosa, Sara (1998): The Corpus-Based Approach: A New Paradigm in Translation Studies. Meta. 43(4):474-479.

- Levinson, Stephen C. (1983): Pragmatics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Mayoral, Roberto, Kelly, Dorothy and Gallardo, Natividad (1988): Concept of Constrained Translation: Non-Linguistic Perspectives of Translation. Meta. 33(3):356-367.

- Monaco, James (1981): How to Read a Film: The Art Technology, Language, History and Theory of Film and Media. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Mubenga, Kajingulu S. (2008): Film Discourse and Pragmatics in Screen Translation: A Contrastive Analysis of Speech Acts in French and English. Ph.D. Thesis, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg.

- Munday, Jeremy (2001): Introducing Translation Studies: Theories and Applications. London: Routledge.

- Neves, Josélia (2004): Language awareness through training in subtitling. In: Pilar Orero, ed. Topics in Audiovisual Translation. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 127-140.

- Pettit, Zoë (2004): The Audio-Visual Text: Subtitling and Dubbing Different Genres. Meta. 49(1):25-38.

- Pottier, Bernard (1987): Le graphémique et l’iconique dans le message. In: Ross Steele and Terry Threadgold, eds. Language Topics in Honour of Michael Halliday. Vol. 1. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 305-313.

- Remael, Aline (2001): Some Thoughts on the Study of Multimodal and Multimedia Translation. In: Yves Gambier and Henrik Gottlieb, eds. (Multi) Media Translation: Concepts, Practices and Research. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 13-22.

- Remael, Aline (2004): A place for film dialogue analysis in subtitling courses. In: Pilar Orero, ed. Topics in Audiovisual Translation. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 103-126.

- Richards, Jack C. and Rodgers, Ted (1985): Method: approach, design, and procedure. In: Jack C. Richards, ed. The Context of Language Teaching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 16-31.

- Rojo López, Ana Maria (2002): Applying Frame Semantics to Translation: A Practical Example. Babel. 47(3):311-350.

- Searle, John R. (1969): Speech Acts: An Essay in the Philosophy of Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Smith, Greg M. (2003): Film Structure and the Emotion System. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Taylor, Christopher J. (2003): Multimodal Transcription in the Analysis, Translation and Subtitling of Italian Films. The Translator. 9(2):191-205.

- Thibault, Paul J. (2000): Multimodal Textual Transcription of a Television Advertisement: Theory and Practice, Visual Collocation. Visited on June 25th, 2008,<http://www-personal.umich.edu/~jaylemke/courses/DA_MxM/Readings/Thibault_texttra22.htm>.

- Toury, Gideon (1995): Descriptive Translation Studies And Beyond. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- van Leeuwen, Theo (1999): Speech, Music, Sound. Houndmills: Macmillan.

- van Leeuwen, Theo (2005): Introducing Social Semiotics. London: Routledge.

List of tables

Table 1

The transitivity structure of the French imperative request

Table 2

The transitivity structure of the English imperative request

Table 3

The transitivity structure of the French declarative apology

Table 4

The transitivity structure of the English imperative Apology

Table 5

The interpersonal structure of the French imperative request

Table 6

The interpersonal structure of the English imperative request

Table 7

The interpersonal structure of the French imperative apology

Table 8

The interpersonal structure of the English imperative apology

Table 9

The thematic and information structures of the French imperative request

Table 10

The thematic and information structures of the French imperative request

Table 11

The thematic and information structures of the French imperative apology

Table 12

The thematic and information structures of the English imperative apology

Table 13

The cognitive frame analysis of the request in example (1)

Table 14

The cognitive frame analysis of the apology in example (2)

10.7202/009016ar

10.7202/009016ar