Résumés

Summary

Trade unions in nearly all developed countries are facing major difficulties in maintaining membership levels and political influence. The U.S. labour movement has been increasingly attracted to an organizing model of trade unionism and, in turn, this response has caught the imagination of some sections of other Anglo-Saxon movements, most notably in Australia, New Zealand and Britain. Despite similarities in the problems that national union movements face, however, the histories and current experiences of trade unions in the various countries show marked differences. This article, based on extensive fieldwork in Britain and Australia, examines attempts to assess the importance of national contexts in the adoption of the organizing model through a comparative study of an Australian and a British union.

Résumé

Les centrales syndicales dans presque tous les pays développés éprouvent des difficultés sérieuses à conserver leur niveau d’adhésion et leur influence politique. Le mouvement ouvrier américain a subit de façon croissante l’attrait d’un modèle d’organisation syndicale qui en retour a retenu l’imagination de quelques sections d’autres mouvements anglo-saxons, notamment et surtout en Australie, en Nouvelle-Zélande et en Angleterre. En dépit des similitudes au plan des problèmes auxquels font face les mouvements ouvriers nationaux, le passé et les expériences actuelles des syndicats ouvriers dans les différents pays présentent cependant des différences importantes aussi bien que des similitudes. Cet essai, basé sur un travail important sur le terrain en Angleterre et en Australie, cherche à cerner l’importance des contextes nationaux au moment de l’adoption d’un modèle d’organisation syndicale en faisant appel à une étude comparative de deux syndicats qu’on identifie à ce modèle dans leur propre pays : le Manufacturing, Science and Finance (MSF) en Angleterre et le Community and Public Sector Union (CPSU) en Australie.

Cet article démontre que les contextes nationaux au sein desquels oeuvrent ces syndicats exercent une influence critique sur leurs stratégies. Les syndicats en Angleterre ont fonctionné, au cours d’une bonne partie de la période d’après-guerre, à l’intérieur de la tradition qui a connu l’incorporation nationale et l’organisation sur les lieux de travail marquée par l’autonomie locale. Pendant les années 1980, on a observé un affaiblissement des syndicats et le contrôle au sein du mouvement ouvrier s’est déplacé vers le sommet. Le déclin du nombre de membres, connu au cours des dix-huit années de la période conservatrice, qui a vu des gouvernements successifs s’engager dans un assaut légal et systématique visant à marginaliser les syndicats, a maintenu l’illusion qu’un gouvernement travailliste renverserait la tendance. Rien de tel ne s’est produit en Australie, où les traditions sur les lieux de travail sont plus faibles et où la plus grande partie du déclin du membership au cours des décennies 1980 et 1990 survint sous des gouvernements travaillistes. Dans l’indifférence, l’élection d’un gouvernement conservateur et anti-syndical en Australie sonnait le glas d’une relation étroite entre les centrales et le gouvernement travailliste au cours des treize années de l’Accord.

Cet article soutient que les efforts au sommet pour adopter le modèle d’organisation syndicale étaient moins prononcés en Angleterre qu’en Australie. De fait, en Angleterre, avec l’élection du Nouveau Parti travailliste en 1997, une stratégie de remplacement, celle d’un « partenariat », a été mise en oeuvre de façon plus rigoureuse par le TUC. Par contre, un syndicat de pointe, le ACTU, a repris le travail d’organisation avec un enthousiasme plus grand et avant l’an 2000 approuva une réforme de l’organisation syndicale comme y détenant la clef de la survie du syndicalisme.

Les deux syndicats retenus pour cette étude, le MSF et le CPSU, reflètent à leur façon les problèmes plus vastes et les expériences du travail d’organisation dans des contextes nationaux. Les deux syndicats ont tenté de radicaliser le fonctionnement de leurs organisations. Le MSF a fait face à la crise en adoptant le modèle d’organisation, mais il a agit ainsi sans chercher à modifier tous les niveaux de sa structure. Ceci s’est traduit par un manque d’engagement précis à l’endroit d’une stratégie d’organisation et par l’introduction de façon autoritaire de nouvelles priorités pour les officiers syndicaux, à l’encontre sensément de l’esprit du modèle. Parallèlement aux priorités du TUC, l’idée de partenariat fit son chemin de façon évidente. Par conséquent, la stratégie d’organisation a échoué, le besoin d’une autre fusion à venir étant reconnu de manière tacite, cette fois avec un partenaire junior. Devant l’absence croissante de l’approbation du travail d’organisation par le TUC, on ne sentait pas une volonté de développement d’une approche mieux intégrée au travail d’organisation et on observait que peu de ressources à la disposition d’un modèle alternatif de pratique syndicale.

L’expérience australienne fut quelque peu différente. Le CPSU démarra avec des problèmes semblables de perte de membership et de culture de service. Il dut envisager les mêmes craintes et la même résistance au changement de la part des permanents et des membres. Cependant, nonobstant l’absence d’engagement soutenu du membership à l’endroit de la nature et de l’envergure du changement, un leadership plus déterminé et cohérent aux niveaux local et national laissait croire que ce syndicat poursuivait de façon fructueuse les réformes au plan de l’organisation syndicale. L’approbation de l’ACTU d’un agenda d’organisation vint apporter un support aux changements amorcés au sein du CPSU.

L’avenir de ces syndicats, et également de bien d’autres, est loin d’être assuré. L’étude comparative démontre que ces syndicats sont obligés de faire face à des circonstances adverses. Cependant, l’étude montre aussi de façon précise que les réactions des syndicats ne sont pas définies à l’avance, mais sont influencées par leur passé particulier, leur dynamique interne et le contexte national plus large au sein duquel ils élaborent leurs stratégies. Dans cette optique, les bureaucraties syndicales ne sont pas nécessairement conservatrices ; elles ne sont pas non plus les victimes passives de leur environnement. Quand ils sont menacés par des crises institutionnelles, les syndicats sont capables de réagir énergiquement aux menaces et aux contraintes. Cet essai soutient que des actions ciblées d’agents de changement au sein des syndicats exercent une influence décisive sur la tournure particulière des stratégies et des performances de l’organisation. Cependant, l’engagement réel du membership annoncé par le modèle d’organisation, nécessaire à une transformation effective des syndicats, n’apparaissait pas évident au travers des changements apportés aux stratégies d’organisation de ces syndicats.

Resúmen

Los sindicatos de casi todos los paises desarrollados estan confrontando grandes dificultades para mantener los niveles de afiliación y de influencia politica. El movimiento laboral de EE.UU. ha estado cada vez mas atraído por un modelo de organización sindical, y a su turno, esta respuesta ha ganado adeptos en algunas secciones de otros movimientos anglo-saxones, en especial en Autralia, Nueva Zelandia y Brasil. A pesar de la similitudes de los problemas enfrentados por los movimientos sindicales nacionales, la historia y experiencia recientes de los sindicatos en varios países muestran diferencias marcantes. Este artículo, basado en un vasto estudio de terreno en Gran Bretaña y Australia, examina los intentos de valorizar la importancia de los contextos nacionales en la adopción del modelo de organización por medio de un estudio comparativo de los sindicatos en Australia y Gran-Bretaña.

Corps de l’article

Western (1997), in an assessment of unions’ performance in eighteen capitalist democracies, maintains that unions have been most successful where there have been three crucial and common institutional factors: (1) working-class parties enlisted the power of the state to promote union organizing; (2) centralized industrial relations reduced employer resistance to unions and enabled a coordinated approach to unionization; and (3) unions that managed unemployment insurance successfully recruited workers at the margins of the labour market (1997: 3). Those unions that benefited most from the above combination during the post-war boom were also cushioned when international competition increased and national settlements began to erode. If Western’s perspectives are accepted, the prospects for the British and Australian trade union movement are bleak. The social democratic parties in both countries are increasingly impervious to the influence of trade unions (Hay 1999; Frankel 1997); collective bargaining continues to be decentralized (Western 1997) and there is no immediate, if any, likelihood of gaining the administration of unemployment insurance.

There are grounds, however, for rejecting Western’s conclusions. The excessively deterministic tone of his argument robs unions and their members of a capacity to respond to and to shape the circumstances in which they find themselves. Facing a declining membership base and an increasingly hostile environment, unions in Australian and the United Kingdom have indeed attempted to change their strategies in order to ensure a future for themselves As a part of this process, unions in both countries have been increasingly attracted to a particular, and largely Anglo-Saxon, response to their problems, namely the “organizing model,” developed by unions in the United States (Aronowitz 1998; Bronfenbrenner et al. 1988; Mort 1999). The organizing model contrasts to the traditional “servicing model,” based upon a transactional relationship where union officials deliver services and, in exchange, union members pay dues (Banks and Metzgar 1989). The servicing approach endows unions’ officials with the guardianship of union resources, strategies and interests and constructs union tactics which are legalistic and remote from members’ workplaces (Crosby 2002). These features make servicing unionism, according to its critics, disempowering for union members, an ineffective use of union resources and a poor model for future union behaviour (Labor Research Review 1991). There is no single definitive account of what constitutes the organizing model but its advocates envisage the transformation of unions into dynamic organizations, where members would become active participants rather than passive consumers (Conrow 1991). The role of union officers in organizing unions would no longer be to solve member problems but instead the officers would take on the role of educators and facilitators of localized activism (Oxenbridge 1997). This would allow unions to stretch their limited resources further, make them more democratic and more resilient to attack from employers (Bronfenbrenner 1997; Bronfenbrenner et al. 1998). Some critics have suggested that the organizing model has its limitations: for instance it has been suggested that the model’s focus upon mobilization makes it insufficient for building a wider working class movement (Fletcher and Hurd 2000), and others have argued that, in practice, organizing unionism has fallen short of its democratic promises (Moody 1997).

Union movements across the world have been increasingly attracted to the organizing model of unionism (Oxenbridge 2002; Heery et al. 2000; Carter 2000; Cooper 2000). British and Australian, national peak councils and individual unions have visited the U.S. and been impressed by the enthusiasm for and the results of the turn towards organizing. These organizations have viewed organizing as an alternative to the almost inevitable decline of Western’s model. This article aims to illustrate the complex processes involved in the adoption and implementation of the organizing model within different trade union settings. The two unions concerned, Manufacturing, Science and Finance (MSF) in the U.K. (which merged with the Amalgamated Engineering and Electrical Union (AEEU) in 2002 to form Amicus) and the Community and Public Sector Union (CPSU) in Australia, organize different employees located in different political economies. The justification for comparing the two lies not in their positional symmetry, but rather in the fact that, despite noted differences, they became leading examples of attempts in self-transformation. The extent of, and limits to, their success in this regard allows wider questions to be raised about the nature of leaderships, the involvement of members and the extent to which the unions reflected national characteristics of industrial relations.

The case study evidence was gathered through extensive interviews with full-time officers and representatives in the case study unions during the period 1997–2002. Individuals interviewed in MSF in the period 1997–2001 included the Assistant General Secretary responsible for the organizing strategy, the National Officer for the Health Service, the Research Director, and Regional Officers in the Midlands and in Scotland. Some of these were interviewed on several separate occasions over this time period. The research conclusions were tested by giving seminars to two national meetings of full-time officials and by means of a report produced for the union. In addition, sixteen lay representatives in Scotland and the Midlands were also interviewed. All interviews (with the exception of the Assistant General Secretary) were taped and transcribed. The CPSU case study draws upon twenty-five interviews with national and state elected officials and the organizing staff of the New South Wales Branch conducted between 1999 and 2001. Interviews ranged from twenty minutes to two hours in length and the majority were taped and transcribed. The research presented here draws upon a broader study of the changing organizing strategies of white-collar Australian unions and includes an analysis of the organizing initiatives of the Australian peak council, the ACTU, during the 1990s. The ACTU study draws upon interviews with the current office bearers of the ACTU including the Secretary and President, as well as with the immediate past Secretary and President. Interviews were also conducted with fifteen non-elected employees of the ACTU, including several interviews with those individuals who were responsible for overseeing ACTU initiatives, such as Organizing Works. All of these interviews, conducted between 1996 and 2001 were taped and transcribed.

Union Decline in Britain

Trade unions in Britain emerged from the Second World War stronger than in the 1930s and were operating in a new, far from hostile, political and legal framework (Taylor 1993). The long post-war economic boom saw the state attempt to depress aspirations and control economic demands through consultative mechanisms. Tripartism had a good deal of success in incorporating unions at the national level (Jessop 1980), but at the local level, high employment levels bred confidence that enabled groups of workers, led by shop stewards, to defy not only employers but frequently their own union. The typical strike involved few people, was unofficial and short-lived (Hyman 1972). Labour was elected in 1964 as the post-war boom faltered but, for the most part, attempted to counter the worsening conditions for capital within the same corporatist framework, through the close links they had with the trade union movement (Coates 1975).

As economic conditions worsened, the form of trade unionism based largely on local organization and “factory consciousness” (Beynon 1973) proved inadequate to sustain activity and gains. Policies adopted by the 1974–1979 Labour Governments, following the Donovan Commission Report (1968) began to regularize and bureaucratize industrial relations at a more local level. Under the guise of the Social Contract, Labour offered improved legal rights to trade unions and employees in return for cooperation in reducing inflation. The Employment Protection Act 1975 had the effect of encouraging legal and individual action against employers rather than strikes and solidarity, with the consequence that workplace organization began to atrophy. The days lost through strikes continued at a historically high level, but reflected a shift towards longer, nationally and officially-led disputes (Edwards 1995: 439–440). The latter initially enhanced the authority of national trade union leaders over their members, but eventually incomes policies caused a round of disenchantment with Labour, especially in the public sector where the brunt of wage controls were felt, allowing Conservative appeals to be attractive, especially amongst skilled workers. The result was the election of the first of a series of Conservative governments in 1979.

Confronted with government hostility, reflected in economic policies and legislative restrictions designed to curtail its power, the trade union movement failed to generate effective opposition. Militancy existed in isolated pockets and a series of key defeats, culminating with the miners’ strike (1984/5), encouraged the belief that union victory was impossible against employers backed by a determined and well-organized state. Trade union membership declined rapidly from 1979 due to a combination of job losses in industries where there was a high union density and a failure to organize new workplaces, industries and services (TUC 1996a; Machin 2000) (table 1). The Trades Union Congress (TUC) moved from rhetorical opposition to the new right agenda to the adoption of “new realism,” a de facto recognition of the agenda of employers and government (McIlroy 1995). Legislative changes making unions responsible for the action of their members undermined union support for industrial action and turned left-wing leaders into at best, spectators and at worst, opponents of industrial action. The only solution offered appeared to be the expansion of membership services and the accommodation to the idea that individualism had supplanted collectivism (Bassett 1987; Bacon and Storey 1996).

Table 1

Aggregate Trade Union Membership in Britain 1979–2000

New Unionism

Neither “new realism” nor the development of services offered any respite to decline, as membership figures and research demonstrated (Waddington and Whitston 1997). The Labour Party’s own accommodation to the Conservative agenda, and its distancing from the unions, combined at this point with the unions’ realization that salvation through the election of a Labour government had been too often frustrated. This realization prompted the TUC to contemplate the development of a more independent agenda. The result was the launch of “New Unionism” in 1996, a project much influenced by developments in the U.S. trade union movement, particularly the emphasis on organizing, as evidenced by “Organizers with Attitude: The USA Experience” (TUC 1996b) (for more extensive and objective accounts of the developments in the U.S., see Aronowitz 1998; Buhle 1999). As part of this perspective, the TUC, mirroring initiatives in the U.S. and Australia, established the Organizing Academy in 1998 to train new organizers to revitalize the British trade union movement.

Arguably, the impact of these initiatives has been limited. Some major unions, including unions with representatives on the steering committee of the Academy, have not sponsored trainees (Heery et al. 2000). This abstention reflects the fact that the TUC commands no authority over affiliates other than to encourage them to adopt the organizing perspective. The TUC’s ability to promote organizing is also undermined by the inherent tensions in the New Unionism project, which from the beginning had a strong orientation towards accommodation to employers’ agendas via partnership agreements (Heery 1997). Moreover, the more conservative elements within the New Unionism project have gained strength over time to give rise to the TUC’s Partnership Institute. According to the TUC’s General Secretary: “Partnership makes managers take their workforce with them. This is no burden on business but the secret to success” (TUC 2000). Press releases from the TUC and debates at the annual conference suggest that the drive for partnership now overshadows the organizing element. It may not be possible for the TUC to regain its national role within state and employer deliberations, but it seems set on attempting to construct micro-corporatist arrangements at company level. In the absence of vigorous campaigns for union recognition and mobilization, evidence is mounting that employers are using the rhetoric of partnership to recruit unions as junior partners in securing workplace change (McIlroy 2000; Oxenbridge et al. 2002).

The movement in TUC policies over time reflects developments in individual unions. There is, in other words, a resonance or correspondence with changes within affiliates. There are tensions between affiliates and the TUC, but TUC policy has largely been mirrored by MSF and has reinforced policies rather than disrupted them. Any MSF member looking towards TUC policy for an alternative around which to mobilize against MSF perspectives would be sorely disappointed.

Manufacturing, Science and Finance

MSF was formed in 1988 by the merger of two unions with very different structures and traditions and claimed a membership of over 600,000 (Carter 1991). The larger of the two, the Association of Scientific, Technical, Managerial and Supervisory Staffs (ASTMS), had its origins in engineering foremen, but had expanded through a combination of recruiting amongst growing sections of white-collar workers and merging with other smaller unions and staff associations to widen its base to include the insurance industry, the National Health Service, the voluntary sector and the North Sea oil industry. The Technical and Supervisory Staffs (TASS), by contrast, had traditionally been based on the drawing offices of large engineering firms but had widened its scope after a failed merger with the manually-based Amalgamated Union of Engineering Workers (AUEW) to include a number of small craft unions and the Tobacco Workers Union. Compounding any difficulties that might arise from the different traditions of the respective memberships were the contrasting internal cultures of the two organizations. Although not without a left-leaning leadership, ASTMS had a much looser form of organization and branches and workplace-groups enjoyed much autonomy. TASS, on the other hand, had a leadership more closely associated with the Communist Party, and a much more centralized and arguably undemocratic internal life (Smith 1987).

From the new union’s inception, promises concerning increased strength and improved services foundered on membership decline (table 2) and a worsening financial base. Having gained ascendancy, the former ASTMS leadership’s initial response was to revert to policies that had proved successful for ASTMS in the past. Central to these policies was the promotion of a servicing relationship with the membership (Carter 1997). Despite the fact that the union had contained well-organized groups prepared to use industrial action, ASTMS had a long tradition of attempting to attract and retain members through the provision of consumer benefits and by portraying its full-time officers as a group of dedicated professionals who could be called upon in the event of employment difficulties. In the new context of the 1990s, this emphasis fit well with the widespread attempts to convert unions to regarding their membership as customers, individuals to whom the unions provided services (Bacon and Story 1996), and paralleled developments within the TUC.

Table 2

MSF Membership and Finances (£000s) 1988-2000

Membership continued to decline and the financial base of the union worsened to the point of crisis. By 1996, with membership almost certainly below the 425,000 claimed, an internal report estimated that, based on past performance, numbers would continue to decline by as much as 7.5% per annum. At this juncture the union’s leadership chose to depart radically from previous practice by adopting Organizing Works, a policy based on the organizing model of trade unionism and borrowed initially from Australian developments because of personal links in this instance. The Assistant General Secretary contrasted the new policy with current practice:

... we can learn much from the techniques of selling and marketing and from recognizing the need to give good service to our members. However for some officers the debate has moved on to another plain. They see the union as a “servicing” organization, the members as clients and the “product” as industrial relations services.

(MSF 1995)

The change would include an increased emphasis on the organization of shop stewards, full-time officers’ priorities turning from individual casework to strengthening workplace organization, and the reorganization of Regional Offices so that administrative and clerical staff took over routine contact with representatives and members.

In practice, the introduction was flawed in several respects. Firstly, the adoption of the policy coincided with staff redundancies, the basis of which caused some anxiety because of their perceived bias against former TASS officials, and this perception did little to calm the acute factionalism that characterized internal relations (Carter 1991). Secondly, even those full-time officers who did not feel threatened by the selection method were nonetheless concerned about the new policy. For a policy predicated on enthusiasm and involvement, its adoption without education and discussion threatened to undermine its effectiveness. Nowhere was there a considered policy document arguing for the change and elaborating the basis of the new direction. The result was that full-time officers felt that their previous work, performed during a very difficult period, was being belittled, and their skills discarded, which added to their unease. Certainly some officers saw it only as a way of cutting costs and intensifying their work. These feelings have ensured that, at times, aspects of the policy have been regarded as an industrial relations issue within the union with official grievances being registered by full-time officers (Carter 2000).

Despite reservations, there was some positive identification with the change. Some former TASS officials saw in the turn a validation of what they viewed as the core role of trade unions, for which their union stood in contradistinction to ASTMS. Similarly, other officials recognized that they could not continue to chase an increasing number of local issues which members themselves were capable of dealing with, at least potentially. Unfortunately for the union, the potential goodwill was never built upon and this allowed the negative evaluations to dominate. Critics of Organizing Works seized upon a number of issues. Firstly, full-time officers were unhappy and unconvinced about the dichotomizing of servicing and organizing, and the characterization of the former as bad and the latter as good. They clearly had a vested interest in regarding the bulk of their previous work as something more than misguided and valueless, but beyond that they were critical of the way in which key national officials exhibited a belief that it was possible to change practice overnight: representatives were being expected to pick up roles and responsibilities without debate and training:

Organizing Works is seen as a great vision from America, Australia and New Zealand, and because it works wonderfully there it must work here. It has to work here. And you have to make it work, there’s no argument about it. You have to drop everything else and adopt this approach. Well life isn’t like that. You know. If a member rings in and says I’ve been sacked, been victimized, can I put the phone down and say I’m sorry I’ve got some organizing to do, you bugger off because you’re not important any more?

(Regional Officer A, Midlands, Interview 1998)

The second major issue that soured relations between the centre and the officials was the blurring of the distinction between organizing and recruitment. Central to the organizing model is the contention that recruitment will follow organizing (Bronfenbrenner 1997), rather than an attempt to recruit first and discover that membership is ineffectual. Although not consciously adopted from the organizing model, exactly this strategy had been slowly developed in the NHS Trusts in the West of Scotland with promising results (Carter 2000). This experience was not, however, utilized and the Scottish architect of the policy being openly hostile to Organizing Works (Lead NHS Official, Scotland, Interview). It quickly became apparent that whatever the formal policy of the union on organizing, there was great pressure on officials to show immediate results in terms of extra numbers:

We’ve been exhausted as full-time officers: recruit, recruit, recruit. That’s your priority. You have to do that. Forget about negotiations. That will always follow by magic. Recruit, then organize some sort of structure and then, you know, forget it. Go on and recruit somebody else. Well we just don’t have the time or the resources.

(Regional Officer A, Midlands, Interview 1998)

This requirement to recruit was given graphic emphasis by the imposition of individual recruitment targets for full-time officers, an imposition that also sat badly with the encouragement of team working. There is no evidence that the imposition of targets had a positive effect on recruitment. Certainly the fact that individuals who were not achieving targets were labeled as the B team carried with it the clear implication that, in the words of one official, “if you were in it you were fucking useless,” and did little to enhance enthusiasm (Regional Officer B, Midlands, Interview 2000).

At the same time as the pressure to change was exerted on union officers, the union structures remained largely unchanged and the organization and culture for implementing the turn to organizing, as in other examples, remained undeveloped (Grabelsky and Hurd 1994). There were attempts to relieve some of the burden of servicing from full-time officers. Clerical and administrative staff in regional offices, for instance, were reorganized under the direction of a manager with the aim of answering routine enquiries that would normally be dealt with by officers. Inadequate staff training meant that this initiative failed to satisfy members and the demands placed upon officers continued unabated. To make matters worse, to compensate for the new work that clerical workers were now supposed to do, officers were required to do much of their own filing and clerical work, and they were too busy or ill-suited for this type of work. Some dedicated organizers were also recruited, but these individuals were poorly integrated into the union structure, and in some respects reinforced the servicing role of full-time officers.

The overwhelming conclusion of officers was that “organizing” was simply an addition to existing practice, rather than an attempt to transform it. No additional resources were devoted in a systematic manner to organizing, education, research or communication, and there was no attempt to develop campaigns and alliances, nor to use members to support external organizing. Examples of practices that correspond to elements of the organizing model did exist, especially in the Health Sector, but these had to be defended against attempts to cut back resources, despite the fact that membership expansion was here at its greatest (Carter 2000). While the union held itself to be an organizing one, this identity was never really embedded in leadership practice or membership consciousness. When opportunities for mergers occurred, for instance with the Institute of Professionals Managers and Specialists (IPMS), the fact that MSF was now claiming to be defined by its stance towards organizing appeared never to figure in the discussion about the policies and nature of the proposed organization. The uneven attitude to organizing is also graphically illustrated in its journals’ representations of the role of the General Secretary. Rather than using the communications to highlight the role of members and representatives, it was much more common to continue to present the General Secretary opening buildings and greeting dignitaries. Similarly, interspersed with calls for organizing and recruitment, advertising and publicity continued to convey a message that joining the union would make members secure and that membership activity was not a requirement. Close relations between senior officials of the union and New Labour have also buttressed membership passivity by reflecting New Labour’s emphasis on the merits of partnerships with employers, over-shadowing the need to organize, a direction reinforced by developments in the TUC.

A rapid transformation of the union into a participative, member-led union was never a possibility. What hindered the prospects of achieving this in the longer term, however, were the methods adopted to foster change. The tone of directives from the national office added to the concerns of officers in the field. There was a belief amongst officers that the complexities and difficulties they faced were ignored. Anyone who spoke against the initiatives was quickly made conscious of the fact that people in positions of power were aware of their views and that their prospects in the organization could be blighted. Rather than the leadership encouraging the involvement and accountability of all, the distinct impression was given that there was one best way that must be followed. There was a need for those in leadership positions to gauge the effectiveness of the union and of the decisions made about resource allocation. However, moves in this direction were uneven. Contrasting to the targets for full-time officers, for instance, was the laxness with which the General Secretary’s expenses were scrutinized. The latter issue became a major concern following public disclosures of allegations of unjustifiable expense claims (Hogan and Greene 2002). These resulted in departures and the dismissal of those making the allegations, but with large settlements and successful compensation claims. It is inconceivable that a leadership committed to organizing, with the attendant dangers to, and sacrifices required of, members and activists, could countenance the sort of expense accounts lifestyle indicated by the revelations, whether or not technically illegal.

Given the failure to manage a transformation of the culture and practice of the union, MSF faced continued decline in membership numbers. Many of the reasons for membership loss were beyond the control of the union as manufacturing and insurance industries continued to rationalize, with attendant redundancies and closures (Delbridge and Lowe 1998). In more stable areas of employment, however, the opportunities for increased membership remained largely unrealized. NHS membership increases were the exception (Carter 2000) but even here officials were hard pressed for resources and did not consider it possible to invest the necessary time with many membership groups in order to achieve the transition to more effective workplace organization and autonomy. The lack of resources was moreover integrally connected to membership loss in the rest of the organization. A consequence of worsening membership and financial figures was that the leadership of the union successfully sought a solution through a further merger. The choice of partner, the AEEU, a union with a right-wing leadership, having little sympathy for membership self-organization and independence (see, for instance, the experiences of a Graphical, Media and Paper Union (GMPU) member 2001), signifies again how little the organizing perspective had influenced the outlook of the leadership of the union.

Union Decline in Australia

Even more steeply than in Britain, Australian union membership density has been on a downward slide for over two decades. While in 1979 just over half (51%) of Australian wage and salary earners were union members, in 2000 under a quarter (24.7%) of workers were unionized (see table 3 below). Membership fell strongly in the 1980s, but the decline accelerated at an alarming rate in the 1990s and, in 1991, absolute numbers began to fall. In the three years from 1996, total membership fell from 2,194,300 to 1,878,200. The only year in which union membership numbers grew was 2000: however, even in this year, density continued to fall. As with the trend internationally, traditional areas of union strength in Australia have contracted and union penetration remains low in the growth areas of the economy (10% in hospitality, 19.6% in the private sector more broadly), among younger workers (12.5 % for workers between 15 and 24 years) and part-time and casual workers (17.5% and 10.7% respectively) (ABS and Ellem 2001).

Table 3

Change in Australian Union Membership and Density 1976–2000

As well as structural changes in the labour market, legislative and regulatory changes also took their toll. The conservative governments that dominated state politics in the early 1990s introduced a raft of anti-union legislation that variously removed payroll deduction, banned the closed shop and wound back the powers of (or abolished) the state Industrial Relations Commissions. These changes shifted the balance of power and affected union organizing and industrial strategies. Upon taking office in 1996, the conservative Coalition federal government, pursued a similar agenda, embarking on extensive privatizations of the public service, introducing legislation that restricted union access to workplaces and most significantly, for the first time in Australian history, enabling individual contracts, known as Australian Workplace Agreements (AWAs) to be introduced in the federal jurisdiction. The new, pro-active anti-union approach taken by the federal government has encouraged employers to take a more aggressive approach to union influence in their workplaces. These approaches combined in the wharfies (dockers) dispute of 1998, when Patrick Stevedores, aided by the government, attempted to replace its 100% union workforce with non-union employees (Trinca and Davies 2000). Patrick was not alone in its aggressive anti-unionism and many other companies used the legislative provisions, particularly AWAs, to aid attempts to de-unionize their workplaces (Peetz 2002).

Whilst in many international settings, the membership decline of the past two decades occurred within the context of hostile, conservative governments, in Australia the majority of that time (1983–1996) comprised years of relative shelter under a federal Australian Labor Party (ALP) government. During this period, the relationship between the national peak council, the Australian Council of Trade Unions (ACTU), and the ALP government was formalized through a prices and incomes Accord. While this agreement was in some ways beneficial to union members, leading to increased employment and improvements in the “social wage,” a number of critics have argued that the reforms to the industrial relations system it ushered in had downsides for unions (see Peetz 1998: 145–173, for a review). Critics of the Accord, including senior union leaders, have suggested that the decline in real wages and bargaining away of employment conditions during the thirteen years of Labor administration were detrimental both to the jobs of union members and to union organization (Bell 1997; Bell and Gahan 1998; Ewer et al. 1991; Cameron 1998).

The relationship between the ALP and the ACTU led to an increasingly centralized union decision making structure, a process which was aided by the amalgamation project of the late 1980s and early 1990s. Here the ACTU pushed for, and the federal government supported, the restructuring of the labour movement into twenty industry based “super unions” (Dabscheck 1995; Costa 1997). While this project successfully reduced the number of unions,[1] it failed to stop the massive leakage in membership. Alongside, and perhaps as a consequence of this centralization, workplace activity, even in those areas where shop floor organization had once been strong, withered. The critical weakness of workplace organization was exposed when enterprise bargaining was introduced in the early 1990s. There were no improvements in workplace activity or organization as the decade progressed. According to the Australian Workplace Industrial Relations Survey (AWIRS), workplaces with an “active” union presence fell from 26% in 1992 to 19% in 1995 (Morehead et al. 1997: 327).

If the Accord years bought the unions some time to formulate strategies to respond to the membership decline that was already underway (Peetz 1998: 164), then clearly this opportunity was squandered. The victory of the conservative Liberal National Coalition government in the federal elections of 1996 saw an abrupt end to the Accord and the relegation of the ACTU to the position of political lobby group, attempting to fight off increasingly deregulationist and anti-union reforms.

Organizing in Australia

By the late 1980s, the ACTU was displaying anxiety over union decline; however it would not be until 1993 that concern turned to organizing. In this year, the peak council arranged a study mission to observe the membership building strategies of unions in North America. Its report contended that the environment faced by the union movements in both countries was similar and that in Australia, as in North America, membership decline was in part attributable to the lack of an organizing culture in unions (ACTU 1993: 35). Acceptance of the report led to the establishment in 1994 of Organizing Works, a training program for young organizers modeled on the AFL-CIO’s Organizing Institute. Organizing Works was conceived as a means to build the organizing capability of affiliates by building their organizing and campaigning skills and by spreading the “message” of organizing unionism. During the period 1993–2000, Organizing Works could claim some considerable successes including the significant number of new members its trainees and graduates brought into host unions and the prosecution of a number of successful, high profile organizing campaigns in a range of industries including hospitality and retail. By the end of 2000, over three hundred Organizing Works trainees had infiltrated every union in the country and the program had become the key entry point for new starters in the union movement. Many graduates of the program moved into senior labour movement positions including, in a few cases, the position of Branch Secretary, but, more commonly, of lead organizer within branches, national unions and labour councils.[2]

Despite the influence of Organizing Works, as in Britain, there is evidence of “institutional sclerosis” (Pocock 1998: 17), but arguably there is a greater and clearer commitment to change in Australia than in Britain. The 1999 accession of Greg Combet to the position of ACTU Secretary marked a significant shift in policy as indicated by the launch of unions@work (ACTU 1999). The document reignited the debate about organizing that had begun earlier in the decade, emphasizing the building of workplace activism, organizing non-union workers, making better and more efficient use of technology and management techniques, and broadening the union agenda beyond the workplace. The publication of the document signalled a deeper practical and political commitment to organizing unionism on the part of the leadership of the union movement, a stance further reinforced at the ACTU’ s policy-making Congress 2000 (Cooper 2000; Crosby 2002). However, unlike the earlier initiatives, such as in relation to amalgamations project, the ACTU leadership was not in a position in this case to direct union behaviour. As the peak body’s power and influence with government and employers was eroded, so too was its authority over affiliates. Additionally, because organizing reform goes to the heart of union character and has significant implications for democracy and activism, it is commitment to change at the level of individual unions, rather than the peak council, which is of critical importance.

The growing interest in organizing among Australian unionists was demonstrated in 2001, when the ACTU sponsored the inaugural “Union Organizing” conference, which was attended by seven hundred union leaders, organizers and activists. However, to date there has been very little research conducted into the nature and extent of organizing focused change within Australian unions. The following section briefly details this under-explored issue, examining organizing reforms put in place by a Branch of one Australian union during the 1990s.

CPSU New South Wales Branch: Adopting a New Way of Organizing

The membership of the Community and Public Sector Union (CPSU) is largely white-collar and is derived from the employees of federal government departments, sections of the broadcasting industry, and the clerical employees of one of Australia’s largest telecommunications carriers. The CPSU is a distinctly federalist union, partly because of the national bargaining structures, and its National Management Committee retains significant power over state-based branches. The union is an important player within the left of the national union movement, but remains, except for a few small sections of the union, unaffiliated to the Australian Labor Party.

The New South Wales Branch of CPSU is the largest in the national union and constitutes approximately a quarter of the national membership. Women make up 54% of the Branch’s total membership. While the majority of the union’s membership in New South Wales is employed in metropolitan areas, there is a significant base of rural and regional membership, with non-metropolitan members making up 22% of the membership in New South Wales. The workplaces the union organizes range from large metropolitan call-centres through to smaller customer service and processing areas across the state.

Membership Crisis

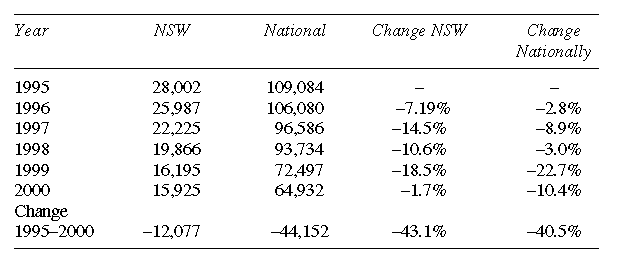

As shown in table 4, both the national organization and this Branch hemorrhaged members during the period from 1995 to 2000. During this time, the union lost 40.3% of its membership nationally, with the New South Wales Branch faring marginally worse than the national average, losing 43%. The primary cause for falling membership was the significant restructuring of the CPSU’s main areas of coverage. After the election of the conservative Coalition government, there was a rash of job cuts in the core areas of the union’s area of coverage. The union suffered the closure of one particularly large government agency and the contracting-out of many functions previously performed by the members of the union. Furthermore, after 1996, the union lost many members who remained in the industry but resigned their membership. Many union staff attributed this latter movement to poor morale in workplaces rife with “redundancy culture” where members lost faith in the union’s ability to protect them.

Coupled with the massive restructuring in the sector, the period also saw a significant change in management orientations towards the union. During the Accord years, many employers had encouraged union membership, and the CPSU was seen as a legitimate stakeholder in the workplace. However, in the post-1996 environment, even basic union rights were contested. Employers attempted to marginalize the union by initiating non-union agreements and introducing AWAs in areas that were traditionally covered by union bargained collective agreements. Contesting AWAs further limited union resources for organizing, a task made more difficult by employers circumscribing organizers’ access to workplaces. In some areas, particularly in telecommunications, this anti-collectivist managerial strategy was pursued to the point where union members were discouraged from talking to each other during working hours.

Table 4

CPSU Membership 1995-2000

Large membership loss and the very different industrial environment had a major impact upon the union’s finances, upon morale in the union office and upon the ability of the union to invent strategies to grow membership:

From 1996 there was a generalized sense of panic. Every week you’d go into [organizers meetings] where you were told about membership losses and for a while there they didn’t show us the figures because they thought we’d be depressed about it!

(Organizer A, Interview 1999)

Stress levels were high among union employees, and beginning in 1996 this began to manifest itself in staff turnover. Many were unable to cope with the pressure of the work, reflected in one instance by “the constant feeling of not being up to the task in front of me;” others found they were no longer suited to organizing an environment, where “you could no longer ring up the boss to get things sorted out” (Organizer T, Interview 1999). Those organizers who remained with the union dealt not only with increased pressure from the changed nature of work but also with an enormous increase in workload.

The Branch’s leadership began almost immediately to push organizers and industrial officers out onto the road and into workplaces in an attempt to stem the decline. The pressure was on to “just get out there and get the membership forms in” (Organizer D, Interview 1998). However, in the context of increasing crises, many organizers felt powerless to keep up with their previous “servicing” workload, let alone to expand their role into one focused on organizing new members. Historical cultures within the Branch valued “servicing”, in particular, performance in the industrial commission and in technical disputes against management, rather than building membership and activism in members’ workplaces. According to one staff member, the role of recruiting new members was viewed as a “definitely unsexy” part of the work of organizers (Organizer A, Interview 1999). These roles for organizers were mutually exclusive. As in MSF, resentment grew among organizers who suggested that unrealistic work pressures and workload were being placed upon them in order to save the union.

In the context of spiralling workloads, continued membership loss, and growing organizer stress and unrest, the management of the Branch began tentative steps toward splitting the servicing and organizing functions of staff. A specialized servicing unit, the Information Unit, was created in 1998, designed to quarantine the servicing functions of organizers from other roles. Inbound calls relating to individual grievances and employment condition inquiries were henceforth dealt with directly by the three staff of this Unit.

The measure met with some resistance from officials, particularly the long-standing ones. These staff saw the Information Unit as an attempt by the unions’ “management” to take power and control over their work away (New South Wales Secretary, Interview 2000). Other organizers expressed frustration that even where phone calls were being filtered through this new unit, pressures for servicing members did not abate. The demands continued because the massive workload generated from ongoing cuts to the public sector created a greater demand for servicing, previous practices of the union created member expectations of a certain type and level of service and finally many organizers were unable to move away from the role which initially attracted them to their posts, in the words of one: to “help people” (Organizer D, Interview 1998).

Despite these challenges to change, the Branch committed ongoing resources to the Information Centre, and three years later, organizers spoke positively about its impact on easing their servicing workload. This initiative by the Branch is seen as “best practice” within the national CPSU, and in 2000 the national union began a program of establishing a call centre to deal with member inquiries and individual grievances in order to provide some respite from servicing and to allow officials to get out and organize. Within the Branch, the leadership emphasized in later interviews that greater organizational value was attributed to the organizing components of industrial staff’s work. This change in priority was reflected in the active monitoring of the performance of organizers to ensure that the balance of their workload was tipped in favour of organizing and in the criteria for the recruitment and selection of new staff.

Throughout the period of organizational crisis from 1996, the Branch’s leadership grappled with ways to set objectives for membership growth and to monitor both individuals’ and Branch performance. Significant resistance greeted the Branch’s first attempts to introduce membership recruitment targets for organizers in 1997. Many organizers expressed displeasure in the Branch, and in their own “industrial association,” at the surveillance of their work by the “managers.” Opposition to performance monitoring was only overcome after a small group of the organizers volunteered to participate in a pilot scheme setting targets at four new members per organizer per week.

In retrospect, and in contrast to the MSF leadership, both the organizers and the Branch leadership argued that the early focus on new member targets for individual organizers was an ineffective way to build commitment to organizing. Subsequently, organizing performance was measured against objectives set by teams of organizers in the context of a broader national strategic planning process. This focused less upon individual accountability and more upon the strategic allocation of stretched union resources. Team members self-monitored their performance in organizing, against quarterly and six-monthly plans. Team workloads and staffing levels were allocated to projects according to their potential for membership growth and their strategic importance to the broader industrial effectiveness of the union. This more “strategic” approach to monitoring organizing performance had implications for work organization of union staff. Whereas organizers’ portfolios were once based upon geographical or employer defined groups of members, workload was later allocated according to priorities set by strategic planning.

The reforms in organizing practice within the CPSU extended to encouraging organizers to use different tactics in their work. Many organizers reported using mobilizing tactics, which placed greater emphasis upon workplace organizing committees, upon allocating resources for activist development and using “smart” demonstrations. Organizing outside of the workplace became commonplace. In one campaign to organize a large regional workplace, for instance, the organizers initiated weekly study groups in the regional workers’ club, in an attempt to build the skills and cohesiveness of local activists. In a group of metropolitan workplaces, weekly discussions were arranged to debrief on the week’s organizing and to plan the following week’s activity. In other instances, organizers concentrated on building the union’s capacity to undertake one-to-one recruitment by identifying and developing new workplace activists.[3] Echoing the approach of U.S. organizing unions, many union campaigns emphasized emphasised issues of justice and dignity in the workplace. In the campaigns, from which these examples are drawn, membership grew in every case.

While CPSU organizers embraced the language and many of the tactics of the organizing model, one crucial element of the strategies associated with the model was not as readily adopted. Member involvement in the process of change at CPSU was minimal. Indeed whilst there was some attempt to “take the debate to the members” (New South Wales Secretary, Interview 1998), this had not (by 2000) been done in a particular systematic fashion. The emphasis upon building workplace activism was driven not by the membership but from the union office, albeit with a rationale of empowering members and workplace representatives. There are obvious limits to a strategy which fails to moves beyond the rhetoric of empowerment. The devolution of tasks to members without the power to determine policy could be dangerous for the union because, according to one organizer:

Members can smell the implications of this [devolution of responsibility], because management does it to them all the time. We say OK so were giving you all this work to do and it really rings hollow unless they have more power to make decisions about things.

(Organizer R, Interview 1999)

Discussion

As both the above account and the TUC (1996c) recognized, the structural causes of trade union membership decline in the U.K. and Australia were very similar, encompassing structural change in the labour market and anti-union employer tactics and legislation. What differed was the political context in which the declines took place, the industrial relations framework in which the unions acted and the influence of the central federation over constituents. These differences ensured that each movement faced relative advantages and disadvantages when it came to attempting to shift the culture of unions away from servicing and towards organizing. The fact that decline in Britain occurred during hostile Conservative governments encouraged unions to believe that they would be back to “business as usual” with the election of a Labour government. This belief served to discourage, for much of the period, recognition of the need to change practice and to act independently. When that realization finally came in the mid 1990s, there was insufficient time for it to take root before the election of New Labour. The independence of constituents made it difficult to ensure the adoption of the organizing model of unionism even if TUC had a clear and committed approach to it. After the election of the new government, however, the TUC placed less emphasis upon organising and an increasing prominence has been given to partnership approaches, ensuring that, if organizing is to be rooted in the life and culture of unions, the necessary leadership would not come from the TUC.

The Australian federation has, in contrast, moved in the other direction. It witnessed a significant decline in membership over thirteen years of Labor administrations. The election of the conservative Coalition government, and their virulent anti-union activities, made a partnership strategy for union recovery impossible in the Australian context. The ACTU had, throughout much of the Accord period, exhibited significant authority over its affiliates and arguably was in a stronger position to direct its constituent members down the organizing route. The unravelling of external sources of ACTU power saw the internal authority of the peak union weakened, and in this context no attempt was made to coerce affiliates to adopt new organizing strategies. The more recent reinvigoration of debate about the need for organizational change has coincided with the election of a new ACTU leadership. This new leadership has dedicated significant effort and resources toward mainstreaming organizing. However, the task is far from easy. Much of the literature on the implementation of organizing reform indicates the significance of leadership commitment for success (Oxenbridge 2002). However, even where this leadership commitment is secured, as has been seen at the ACTU, the objective reality of the Australian workplace—such as poor levels of workplace organization (Howard 1977; Moorehead et al. 1997)—may mean unions have a harder task than their British counterparts to foster the levels of organization at the workplace level required of an organizing model approach. These different national circumstances provide the context in which the unions studied adopted the organizing model. The case studies of MSF and CPSU show both remarkable similarities as well as some instructive differences.

Both the CPSU and MSF faced organizational crisis as a result of membership loss. In both unions, there was recognition that traditional ways of working were no longer tenable in such an environment. Both unions tried to radicalize the practice of their organizations. The initial responses of the leadership of both unions were similar. Staff cuts were implemented in an attempt to ease the pressure of membership loss on the unions’ budgets. The urgent need to increase union membership saw union leaderships enact policies aimed at building the recruitment effort of individual officers through the introduction of individual targets. The experience of both unions suggests that changing the work roles of union officials and altering established methods of performance management is problematic. The ongoing pressures of the changing industrial environment heightened the tensions resulting from the implementation of changes to organizers’ work. In both unions, many officials interpreted these changes as an unrealistic attempt to increase workload without making the broader organizational changes to support such a move. Most were uncertain and fearful of the implications of these directions for control over their work and maintenance of their job security. At MSF, confidence in the strategy was further undermined by lack of tangible success of Organizing Works and their ongoing inability to openly make criticisms of the leadership’s agenda.

At CPSU better progress was made. When change was focused upon individual recruitment targets, officials were understandably sceptical of the motives of the union leadership. Organizers faced the ongoing and competing pressures of servicing and “recruiting” workloads leading to high work stress and low levels of commitment to building the union’s membership. More recently union leaders had greater success in building broad-based commitment to implementing the organizing model. A number of factors allowed the CPSU to implement more change and to garner wider commitment to it than has MSF. The leadership of the CPSU exhibited a greater commitment and consistency towards the organizing model and there were identifiable local leaderships prepared to implement it.

Perhaps because of this, or because of political differences between the leaderships of the two unions, there was a more obvious leadership commitment to the principles of the organizing model and to steering the organization to adopting changes aimed at implementing it at the CPSU. At MSF, officials who were supportive of the move to organizing, reported that prominent leaders of the union, including the General Secretary, were not sufficiently committed to the philosophy that underpinned the organizing model. In contrast, most organizers employed by CPSU recognized that leaders and other key officials in the New South Wales Branch were instrumental in pushing the recent changes within the CPSU nationally. During the later stages of the CPSU study the adoption of organizing reform moved from being a concern primarily of the New South Wales branch to being adopted by the unions powerful National Management Committee. This led to a number of initiatives nationally such as the national Membership Service Centre (MSC), as well as a restructuring of the national union into teams to organize in selected employment areas. Present indications are that these two initiatives, the MSC aimed at relieving some of the servicing pressures on the union’s organizing staff, and the restructuring aimed at building a collective approach to building membership through organizing, are themselves adding to the organizing culture of the union. These changes have had a reinforcing impact on organizing reform. By comparison, MSF has both failed to make significant advances at the local level and the leadership has been unprepared to generalize those there have been through concerted organizational change.

While there are clearly areas of difference in the ways that the CPSU and MSF sought to implement approaches to organizing styled approaches, there remains a significant area of similarity: members were little involved in shaping change in their organizations. In neither union was there a comprehensive process of drawing members into a debate about the best ways to increase membership, activism and organizational effectiveness. While the leadership of both unions sought to introduce changes predicated upon increasing member activism and control over union directions, the change process was the exclusive domain of union officials and indeed of particular officials. While in more recent times there has been an attempt to inform members of the changes under way at the CPSU, this does not equal member control over the union agenda. The top-down formulation and implementation of the change strategy in the two unions contrasts with central tenants of the organizing model. If trade union leaderships are serious about transforming their organizations and the key to renewal is membership activity to build the unions from the base up, it is imperative that members be also involved in determining the solutions to the problems they face.

Conclusion

These two cases suggest that in the face of threats to their long-term existence, bureaucracies are not necessarily conservative. Both unions tried to radicalize the practice of their organizations, but practice remains delimited by the way changes were introduced. MSF responded to the crisis it faced by adopting the organizing model but without also attempting to transform all levels of its organization. The result was lack of clear leadership and commitment to Organizing Works and an authoritarian imposition of new priorities on officers against the spirit of the organizing model. The result has been that the organizing strategy has failed, acknowledged tacitly by the need for yet another merger, this time as a junior partner. With the election of New Labour, the emphasis within the union changed in favour of partnership agreements, a movement reflected in TUC policies. This latter movement ensured that there was no exogenous spur to a more developed approach to organizing.

The experience in Australia was somewhat different. The CPSU started with similar problems of a servicing culture and membership loss. It encountered the same fears and resistance to change from officers and members. However, notwithstanding the absence of consistent membership involvement in the nature and scale of change, more determined and consistent leadership at local and national level has indicated commitment to organizing, and developments within the ACTU have reinforced the union’s strategic direction. The option of a partnership approach is less credible in Australia as employers and the conservative Coalition government have shown an increasing hostility to unions. Hopes that a Labor administration would solve the union movement’s problems are undermined by memories that membership declined and workplace organization atrophied throughout the thirteen years of the Accord.

The future of these unions, as that of many others, is far from certain. If Western’s (1997) prognosis is accepted, then their further demise is to be expected. Certainly, states are increasingly reluctant to support union organization, decentralization and fragmentation of bargaining looks set to continue and the granting of the administration of unemployment insurance seems very unlikely. What the comparative study demonstrates, however, is that without denying the influence of these factors, Western’s structural determinism is overplayed. The policies that unions adopt in response to these circumstances are in a double sense not predetermined. Not only are unions capable of acting in response to these external constraints, but the nature of their response to secure their long-term future is an outcome of internal relations between officials, activists and members.

Parties annexes

Notes

-

[1]

The number of Federally registered unions dropped from 134 to 46 from 1990 to 1996 (ABS).

-

[2]

During the 1990s, the ACTU put in place a number of other organizing initiatives. These initiatives including the Organizing Unit, which “contracted out” lead organizers to individual unions to work on strategic organizing campaigns, all aimed to enhance the organizing capacity of affiliates.

-

[3]

In some cases this has meant encouraging people who have previously not been activists to take over from current delegates, in many cases this has meant women have begun to take over delegate positions from men with the organizers support (Organizer C, Interview 1999).

References

- ACTU. 1993. United States Mission Report: Priority One, the Organising Trail. ACTU: Melbourne.

- ACTU. 1999. Unions@work: The Challenge for Unions in Creating a Just and Fair Society. ACTU: Melbourne.

- Aronowitz, S. 1998. From the Ashes of the Old: American Labor and Americas Future. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics(ABS). 1990–2000. Trade Union Members. Catalogue 6325.0

- Australian Bureau of Statistics(ABS). 1990–2000. Employee Earnings, Benefits and Trade Union Membership. Catalogue 6310.0

- Bacon, N. and J. Storey. 1996. “Individualism and Collectivism and the Changing Role of Unions.” The New Workplace and Trade Unionism. P. Ackers, C. Smith and P. Smith, eds. London: Routledge.

- Banks, A. and J. Metzgar. 1989. “Participating in Management: Union Organising in a New Terrain.” Labor Research Review, Vol. 18, Fall/Winter, 61–71.

- Bassett, P. 1987. Strike Free: New Industrial Relations in Britain. London: Papermac.

- Bell, S. 1997. Ungoverning the Economy: The Political Economy of Australian Economic Policy. OUP: Melbourne.

- Bell, S. and P. Gahan. 1998. Union Strategy, Membership Orientation and Union Effectiveness: An exploratory Analysis. School of Industrial Relations and Organisational Behaviour, Working Paper Series, University of New South Wales, Working paper 123.

- Beynon, H. 1973. Working for Ford. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

- Briggs, C. 1999. “The Rise and Fall of the ACTU: Maturation, Hegemony and Decline.” Unpublished PhD thesis, Department of Industrial Relations, University of Sydney.

- Bronfenbrenner, K. 1997. “The Role of Union Strategies in NLRB Certification Elections.” Industrial and Labor Relations Review, Vol. 50, 195–212.

- Bronfenbrenner, K., S. Friedman, R. Hurd, R. Oswald and R. Seeber, eds. 1998. Organizing to Win: New Research on Union Strategies. Ithaca: ILR Press.

- Buhle, P. 1999. Taking Care of Business: Samuel Gompers, George Meany, Lane Kirkland and the Tragedy of American Labor. New York: Monthly Review Press.

- Cameron, D. 1998. “AMWU National Secretary, Speech to Australian Industry Group.” 31 August, Melbourne.

- Carter, B. 1991. “Politics and Process in the Making of MSF.” Capital and Class, No. 45, 35–71.

- Carter, B. 1997. “Adversity and Opportunity: Towards Union Renewal in MSF?” Capital and Class, No. 61, 8–18.

- Carter, B. 2000. “Adoption of the Organising Model in British Trade Unions: Some Evidence from MSF.” Work, Employment and Society, Vol. 14, No. 1, 117–136.

- Coates, D. 1975. The Labour Party and the Struggle for Socialism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Combet, G. 2000. “Secretary’s Address.” Unions Work: ACTU Congress 2000, Wollongong, July.

- Conrow, T. 1991. “Contract Servicing from an Organizing Model.” Labor Research Review, Vol. 17, 45–59.

- Cooper, R. 2000. “Organise, Organise, Organise! ACTU Congress 2000.” Journal of Industrial Relations, Vol. 42, No. 4, 582–594.

- Costa, M. 1997. “Union Reform; Union Strategy and the Third Way.” Reforming Australia’s Unions. M. Costa and M. Hearn, eds. Sydney: Federation Press.

- Crosby, M. 2000. “Union Renewal in Australia: The View from the Inside.” Trade Unions 2000: Retrospect and Prospect. G. Griffin, ed. Melbourne: NKCIR, 127–153.

- Crosby, M. 2002. “Down with the Dictator: The Role of Unions in the Future.” Working Futures: The Changing Nature of Work and Employment in Australia. R. Callus and R. Lansbury, eds. Sydney: The Federation Press, 115–131.

- Dabscheck, B. 1995. The Struggle for Australian Industrial Relations. Melbourne: Oxford University Press.

- Delbridge, R. and J. Lowe, eds. 1998. Manufacturing in Transition. London: Routledge.

- Edwards, P. 1995. “Strikes and Industrial Conflict.” Industrial Relations. P. Edwards, ed. Oxford: Blackwell, 434–460.

- Ellem, B. 1998. “Trade Unionism in 1998.” Journal of Industrial Relations, Vol. 41, No. 1, 127–151.

- Ellem, B. 2001. “Trade Unionism in 2000.” Journal of Industrial Relations, Vol. 43, No. 1, 196–218.

- Ewer, P., I. Hampson, C. Lloyd, J. Rainford, S. Rix, and M. Smith. 1991. Politics and the Accord. Sydney: Pluto.

- Fletcher, B. and R. Hurd. 1998. “Beyond the Organizing Model: The Transformation Process in Local Unions.” Organizing to Win: New Research on Union Strategies. K. Bronfenbrenner et al., eds. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Fletcher, B. and R. Hurd. 2000. “Is Organizing Enough?” www.qc.edu/newlaborforum/html/6_article2.html

- Frankel, B. 1997. “Beyond Labourism and Socialism: How the Australian Labor Party Developed the Model of New Labour.” New Left Review, No. 221, 3–33.

- Grabelsky, P. and R. Hurd. 1994. “Reinventing and Organizing Union: Strategies for Change.” Proceedings of the 46th Annual Meeting of the Industrial Relations Research Association. Boston: IRRA.

- Griffin, G. 1991. “The Authority of the ACTU.” Economic and Labour Relations Review, Vol. 5, No. 1, 81–103.

- GMPU Member. 2001. www.actionforsolidarity.org.uk/unions/090900/wellshinton.html, accessed 26–02–2002.

- Hay, C. 1999. The Political Economy of New Labour. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Heery, E. 1997. “The Re-launch of the Trades Union Congress.” British Journal of Industrial Relations, Vol. 36, No. 3, 339–360.

- Heery, E., M. Simms, R. Delbridge, J. Salmon and D. Simpson. 2000. “The TUC’s Organising Academy: An Assessment.” Industrial Relations Journal, Vol. 31, No. 5, 400–415.

- Hogan, J. and A. Greene. 2002. “E-Collectivism: On-Line Action and On-Line Mobilisation.” www.msfweb.org.uk, accessed 26–02–02.

- Howard, W. 1977. “Australian Trade Unions in the Context of Union Theory.” Journal of Industrial Relations, Vol. 19, No. 3.

- Hyman, R. 1972. Strikes. London: Fontana.

- Jessop, B. 1980. “The Transformation of the State in Post-war Britain.” The State in Western Europe. R. Scase, ed. London: Croom Helm.

- Long, S. 2000. “Employers Set Up New Barriers for Unions.” Australian Financial Review, 19–05.

- Labor Research Review. 1991. “An Organizing Model of Unionism.” Vol. 17.

- Machin, S. 2000. “Union Decline in Britain.” British Journal of Industrial Relations, Vol. 38, No. 4, 631–645.

- McIlroy, J. 1995. Trade Unions in Britain Today. Manchester: MUP.

- McIlroy, J. 2000. “New Labour, New Unions, New Left.” Capital and Class, No. 71, 11–45.

- Moody, K. 1997. Workers in a Lean World. London: Verso.

- Moorehead, A., M. Steele, M. Alexander, K. Stephen and L. Duffin. 1997. Changes at Work: The 1995 Australian Workplace Industrial Relations Survey. Melbourne: Longman.

- Mort, J., ed. 1999. Not Your Father’s Movement: Inside the AFL-CIO. London: Verso.

- MSF. 1995. Circular. London: MSF.

- Oxenbridge, S. 1997. “Organizing Strategies and Organizing Reform in New Zealand Service Sector Unions.” Labor Studies Journal, Vol. 22, No. 3, 3–27.

- Oxenbridge, S. 2002. “The Service and Food Workers Union of Aotearoa: A Story of Crisis and Change.” Trade Union Renewal and Organising: A Comparative Study of Trade Union Movements in Five Countries. P. Fairbrother and C. Yates, eds. London: Continuum.

- Oxenbridge, S., W. A. Brown, S. Deakin, C. Pratten and P. Ryan. 2002. “Collective Representation and the Impact of Law: Initial Responses to the 1999 Employment Relations Act.” British Journal of Industrial Relations, Vol. 40.

- Peetz, D. 1988. Unions in a Contrary World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Peetz, D. 2002. “Individual Contracts, Bargaining and Union Membership.” Proceedings of the 16th Annual AIRAANZ Conference. Queenstown, New Zealand, 6–8 February, 374–383.

- Pocock, B. 1998. “Institutional Sclerosis: Prospects for Trade Union Transformation.” Labour and Industry, Vol. 9, No. 1.

- Smith, C. 1987. Technical Workers: Class, Labour and Trade Unionism. Basingstoke: Macmillan.

- Taylor, R. 1993. The Trade Union Question in British Politics: Government and Unions Since 1945. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Trinca, H. and A. Davies. 2000. Waterfront: The Battle that Changed Australia. Sydney: Doubleday.

- TUC. 1996a. New Unionism: A Message from John Monks. London: TUC.

- TUC. 1996b. Organisers with Attitude: The USA Experience. London: TUC.

- TUC. 1996c. The Wisdom of Oz: The Australian Experience. London: TUC.

- TUC. 2000. TUC to Set Up Partnership Institute as New Research Shows Unions Can be Boost to Business. Press Office, TUC, London, April 18.

- Waddington, J. and C. Whitston. 1997. “Why Do People Join Unions in a Period of Membership Decline?” British Journal of Industrial Relations, Vol. 35, No. 4, 515–546.

- Western, B. 1997. Between Class and Market: Postwar Unionization in the Capitalist Democracies. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Liste des tableaux

Table 1

Aggregate Trade Union Membership in Britain 1979–2000

Table 2

MSF Membership and Finances (£000s) 1988-2000

Table 3

Change in Australian Union Membership and Density 1976–2000

Table 4

CPSU Membership 1995-2000